Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are approximately 21-nucleotide-long RNAs processed from nuclear-encoded transcripts, which include a characteristic hairpin-like structure. MiRNAs control the expression of target transcripts by binding to reverse complementary sequences directing cleavage or translational inhibition of the target RNA. Artificial miRNAs (amiRNAs) can be generated by exchanging the miRNA/miRNA* sequence within miRNA precursor genes, while maintaining the pattern of matches and mismatches in the foldback. Thus, for functional gene analysis, amiRNAs can be designed to target any gene of interest. The moss Physcomitrella patens exhibits the unique feature of a highly efficient homologous recombination mechanism, which allows for the generation of targeted gene knockout lines. However, the completion of the Physcomitrella genome necessitates the development of alternative techniques to speed up reverse genetics analyses and to allow for more flexible inactivation of genes. To prove the adaptability of amiRNA expression in Physcomitrella, we designed two amiRNAs, targeting the gene PpFtsZ2-1, which is indispensable for chloroplast division, and the gene PpGNT1 encoding an N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. Both amiRNAs were expressed from the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) miR319a precursor fused to a constitutive promoter. Transgenic Physcomitrella lines harboring the overexpression constructs showed precise processing of the amiRNAs and an efficient knock down of the cognate target mRNAs. Furthermore, chloroplast division was impeded in PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA lines that phenocopied PpFtsZ2-1 knockout mutants. We also provide evidence for the amplification of the initial amiRNA signal by secondary transitive small interfering RNAs, although these small interfering RNAs do not seem to have a major effect on sequence-related mRNAs, confirming specificity of the amiRNA approach.

During the last decade, small nonprotein-coding RNAs (20–24 nucleotides [nt] in size) have been demonstrated to be involved in RNA-mediated phenomena such as RNA interference (RNAi), cosuppression, gene silencing, and quelling (Matzke et al., 1989; Napoli et al., 1990; de Carvalho et al., 1992; Romano and Macino, 1992; Lee et al., 1993; Hamilton and Baulcombe, 1999). Major classes of small RNAs include microRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which differ with respect to their biogenesis (Bartel, 2004; Chapman and Carrington, 2007). MiRNAs are approximately 21-nt RNAs that are encoded by endogenous MIR genes. Their primary transcripts form precursor RNAs exhibiting a partially double-stranded stem-loop structure that is processed by DICER-LIKE proteins to release mature miRNAs (Bartel, 2004). MiRNAs are recruited to the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), where they become activated by unwinding of the double strand and subsequently bind to complementary mRNA sequences resulting in either direct cleavage of the mRNA or repression of their translation by RISC (Bartel, 2004; Kurihara and Watanabe, 2004; Brodersen et al., 2008). Recently, miRNAs have been identified as important regulators of gene expression in both plants and animals (Jones-Rhoades et al., 2006), and particular miRNA families were shown to be highly conserved in evolution (Jones-Rhoades et al., 2006; Axtell et al., 2007; Fahlgren et al., 2007; Fattash et al., 2007; Axtell and Bowman, 2008). In contrast, precursors of siRNAs form perfectly complementary double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) molecules (Myers et al., 2003). They originate from transgenes, viruses, and transposons and may require RNA-dependent RNA polymerases for dsRNA formation (Waterhouse et al., 2001; Aravin et al., 2003). Unlike miRNAs, the diced siRNA products derived from the long complementary precursors are not uniform in sequence, but correspond to different regions of their precursor. Whereas miRNAs mainly mediate posttranscriptional control of endogenous transcripts, siRNAs have been implicated in transcriptional silencing of transposable elements as well as posttranscriptional control of endogenous and exogenous RNAs, for example, viral transcripts (Waterhouse et al., 2001; Aravin et al., 2003; Myers et al., 2003; Ossowski et al., 2008).

Previous reports demonstrated that the alteration of several nucleotides within the miRNA sequence does not affect its biogenesis as long as the positions of matches and mismatches within the precursor stem loop remain unaffected (Vaucheret et al., 2004). This raises the possibility of modifying miRNA sequences and creating artificial miRNAs (amiRNA) directed against any gene of interest resulting in posttranscriptional silencing of the corresponding transcript (Zeng et al., 2002; Parizotto et al., 2004; Alvarez et al., 2006; Niu et al., 2006; Schwab et al., 2006; Warthmann et al., 2008). In addition, genome-wide expression analyses in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) have shown that plant amiRNAs exhibit high specificity similar to natural miRNAs (Schwab et al., 2005, 2006), such that their sequences can easily be optimized to knock down the expression of a single gene or several highly conserved genes without affecting the expression of other genes.

The moss Physcomitrella patens has become a recognized model system to study diverse processes in plant biology, which was mainly based on the unique ability to efficiently integrate DNA into its nuclear genome by means of homologous recombination enabling the generation of targeted gene knockout lines (Schaefer, 2002). Furthermore, based on the predominant haploid phase of Physcomitrella's life cycle, the frequency of phenotypic deviations caused by the disruption of a single gene is higher compared to seed plants (Egener et al., 2002). Nevertheless, the generation of targeted knockout mutants in Physcomitrella has limitations. For example, despite the haploid genome, homologs might still compensate for each other and one cannot recover knockouts of genes with essential functions. Furthermore, the targeted knockout of a single gene requires several cloning steps, repetitive selection of transgenic lines, and detailed molecular analysis of putative knockout candidates. The recently published Physcomitrella genome (Rensing et al., 2008) now opens the way for medium- to large-scale analysis of gene functions in a postgenomic era (Quatrano et al., 2007) requiring the development of new techniques. The posttranscriptional silencing of genes by amiRNAs may serve as an appropriate tool to speed up such analyses because they can be designed to target several genes (as long they contain at least one conserved sequence stretch), amiRNAs can be expressed from inducible promoters, and amiRNA constructs can easily be generated using a standardized cloning procedure (Schwab et al., 2006).

Alternative approaches to analyze gene functions in Physcomitrella were recently reported, which were based on the expression of classical inverted repeat sequences resulting in the formation of dsRNA molecules, which give rise to siRNAs and consequently silence the target transcript (Bezanilla et al., 2003, 2005; Vidali et al., 2007). One drawback to applying classical RNAi constructs is the production of a diverse set of siRNAs from the complete dsRNA, which may affect off-target transcripts. Furthermore, in some cases, gene silencing triggered by the expression of inverted repeat sequences was found to be unstable in Physcomitrella (Bezanilla et al., 2005). Additional differences in the action of siRNAs and amiRNAs may result from their varying mobility within the plant. Recent studies have shown that transgene-derived or viral-induced siRNAs are able to move from cell to cell, whereas miRNAs are not mobile and act cell autonomously (Tretter et al., 2008).

Independent studies on small RNAs in Physcomitrella revealed the existence of a diverse miRNA repertoire, including highly conserved miRNA families (Arazi et al., 2005; Axtell et al., 2006, 2007; Talmor-Neiman et al., 2006; Fattash et al., 2007). Furthermore, their corresponding precursor transcripts share the characteristic hairpin-like structure known from seed plants. Thus, the design and expression of amiRNAs for the specific knock down of genes in Physcomitrella should be feasible. To test amiRNA function in Physcomitrella, we targeted the gene PpFtsZ2-1, which is required for chloroplast division (Strepp et al., 1998), and the PpGNT1 gene encoding an N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (Koprivova et al., 2003). PpFtsZ2-1 null mutants form macrochloroplasts, presenting an obvious phenotype, which enables direct evaluation of the efficiency of the intended amiRNA approach.

RESULTS

Expression and Detection of PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA in Physcomitrella

The use of amiRNAs for efficient gene silencing has been reported in various seed plants (Alvarez et al., 2006; Niu et al., 2006; Schwab et al., 2006; Warthmann et al., 2008), but it has not been tested in nonseed plants such as the bryophyte P. patens. This is an issue because functional studies of essential members of the RNAi machinery in Physcomitrella, such as Dicer and Argonaute proteins, are still missing (Axtell et al., 2007). Furthermore, the complement of essential RNAi-related proteins in Physcomitrella differs from that in seed plants (Axtell et al., 2007; Rensing et al., 2008).

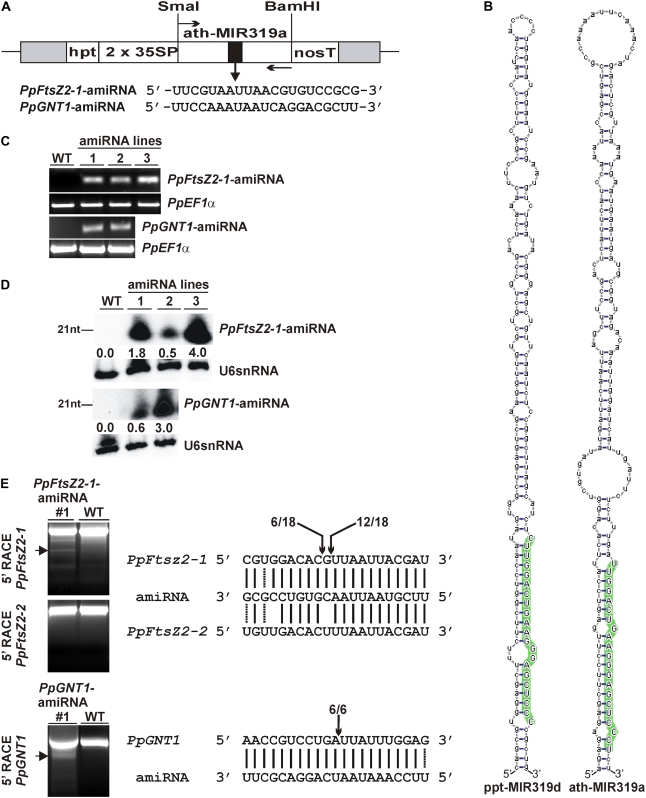

We designed two amiRNAs that were predicted to target the genes PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1, respectively, using the amiRNA designer interface WMD (Schwab et al., 2006; Ossowski et al., 2008). The designed amiRNAs contain a uridine residue at position 1 and an adenine residue at position 10, both of which are overrepresented among natural plant miRNAs and increase the efficiency of miRNA-mediated target cleavage (Schwab et al., 2005). Furthermore, we also preferred that the amiRNAs exhibit 5′ instability relative to the miRNA*, which positively affects separation of both strands during RISC loading (Fig. 1A; Mallory et al., 2004; Schwab et al., 2005). In previous studies, the Arabidopsis miR319a precursor was used to introduce specific nucleotide changes within the miRNA/miRNA* stem-loop region. Based on the conservation of the miR319 family among land plants (Jones-Rhoades et al., 2006; Fattash et al., 2007; Axtell and Bowman, 2008; Warthmann et al., 2008) and similar secondary structures of miR319 precursor transcripts from Arabidopsis and Physcomitrella (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S1), we hypothesized that the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA will be correctly processed from the Arabidopsis miR319a precursor. The PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA and the corresponding miRNA* sequences were introduced into the miR319a precursor by overlapping PCR using primers harboring the respective amiRNA and miRNA* sequences, cloned into the plant expression vector pPCV downstream of a double cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (Fig. 1A) and used for transfection of Physcomitrella protoplasts. After selection of regenerating plants, genomic DNA of individual lines was analyzed by PCR with primers flanking the amiRNA sequence present in the expression constructs to identify transgenic lines that had integrated the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA constructs, respectively. Eight of 12 regenerated lines derived from the transformation with the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA construct and seven of 12 regenerated lines derived from the transformation with the PpGNT1-amiRNA construct produced the expected PCR amplicon. Thus, we cannot exclude that some lines survived the antibiotic selection without the integration of the DNA constructs. From the lines harboring an overexpression construct, three PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA lines and two PpGNT1-amiRNA lines were selected for further analysis (Fig. 1C). As the generated amiRNA overexpression constructs do not contain homologous sequences of the Physcomitrella genome, the constructs are expected to integrate into the Physcomitrella genome by an illegitimate recombination event. To prove the correct maturation of the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA from the Arabidopsis miR319a precursor and its accumulation in the transgenic lines, we performed small RNA gel-blot analyses with antisense probes for both amiRNAs. Accumulation of the mature PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA was detected in all lines analyzed, demonstrating that the amiRNAs are efficiently processed from the Arabidopsis miR319a precursor in Physcomitrella (Fig. 1D). However, normalization of the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA hybridization signals to the U6snRNA controls revealed amiRNA expression levels that differed up to 8-fold for the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and up to 5-fold for the PpGNT1-amiRNA between the individual lines (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Analysis of Physcomitrella lines expressing PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA. A, Scheme illustrating the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA overexpression constructs. The modified ath-miRNA319a precursor DNA fragments were cloned into the SmaI and BamHI sites of the pPCV plant expression vector containing a double 35S promoter, nos terminator, and hpt selection marker cassette. Primers that were used for molecular analyses of the transgenic lines are indicated by arrows. B, Secondary structures of foldbacks of the P. patens miR319d precursor (ppt-MIR319d) and Arabidopsis miR319a precursor (ath-MIR319a). The mature miRNA is highlighted in green with uppercase letters. C, PCR screen to identify transgenic lines harboring the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA expression constructs. WT, Wild type; amiRNA lines, 1, 2, and 3 for PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA; 1 and 2 for PpGNT1-amiRNA; PpEF1α, control PCRs. D, Expression analysis of PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA in Physcomitrella wild type (WT), and lines harboring the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA or PpGNT1-amiRNA expression constructs. Fifty micrograms of each RNA was blotted and hybridized with a PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA antisense probe, respectively. Hybridization with an antisense probe for U6snRNA served as control. PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA expression levels were normalized to the U6snRNA control hybridization. Numbers indicate the relative PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA expression levels. E, Top, 5′ RACE-PCRs for the genes PpFtsZ2-1 and PpFtsZ2-2 from wild type (WT) and line 1 expressing the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA; bottom, 5′ RACE-PCR for the gene PpGNT from wild type (WT) and line 1 expressing the PpGNT1-amiRNA. The arrows mark PCR fragments corresponding to the expected size of the cleavage products that were isolated, cloned, and sequenced. The right images show the sequence complementarity of PpFtsZ2-1, PpFtsZ2-2, and PpGNT1 to the amiRNA sequences. The determined cleavage sites within the PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 mRNAs are marked by vertical arrows and numbers above indicate the number of sequenced products cleaved at this site. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

AmiRNA-Directed Cleavage of PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 mRNAs

The expression of the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA should cause cleavage of the cognate mRNAs within the region complementary to the amiRNA sequences. To prove this, we performed 5′ RACE-PCRs to detect specific PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 mRNA cleavage products. Using 5′ RACE-ready cDNA prepared from one PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA, one PpGNT1-amiRNA overexpression line, and wild type, cleavage products of the expected size were only amplified from the amiRNA lines. Conversely, in wild type, the 5′ RACE-PCRs yielded exclusively fragments derived from the full-length transcripts (Fig. 1E). The PCR products corresponding to the expected size of the PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 mRNA cleavage products in the amiRNA lines were cloned and sequenced to determine the precise mRNA cleavage sites. In 12 of 18 clones analyzed, PpFtsZ2-1 mRNA cleavage occurred between nucleotide positions 11 and 12 with respect to the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA sequence, whereas the remaining six clones resulted from cleavage of the PpFtsZ2-1 mRNA between nucleotides 12 and 13 (Fig. 1E). Normally, in plants, cleavage within a target transcript that is mediated by a 21-nt miRNA occurs between positions 10 and 11 with respect to the miRNA sequence (Llave et al., 2002), suggesting that the actual amiRNAs produced from the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA construct were shifted by 1 or 2 nt. However, the sequencing of six independent clones of PpGNT1 mRNA cleavage products revealed that cleavage occurred between positions 10 and 11 with respect to the PpGNT1-amiRNA sequence (Fig. 1E), indicating precise processing of the PpGNT1-amiRNA from the precursor construct.

Target sites in plant mRNAs normally share high sequence complementarity to the respective miRNA (Schwab et al., 2005). To prove the specificity of the expressed PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA, we analyzed whether the mRNA of PpFtsZ2-2, the closest homolog of PpFtsZ2-1, is targeted by the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA. Compared to the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA recognition site in PpFtsZ2-1, the corresponding region within the PpFtsZ2-2 sequence contains two mismatches at positions 12 and 16. 5′ RACE-PCRs were performed using a PpFtsZ2-2 gene-specific primer. PCR products indicating amiRNA-guided cleavage products were not obtained. Instead, the 5′ RACE-PCR yielded exclusively fragments corresponding to the PpFtsZ2-2 full-length transcript (Fig. 1E). Thus, the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA exhibits high specificity, comparable to natural miRNAs.

AmiRNAs Efficiently Down-Regulate PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 mRNA Levels

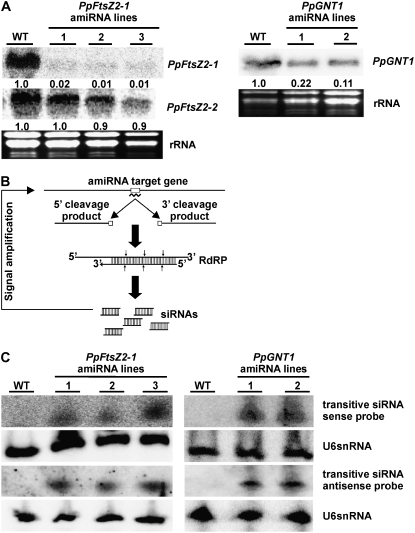

As we detected amiRNA-directed cleavage of the PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 target mRNAs, we next analyzed the target transcript levels by RNA gel blots. Compared to wild type, we detected strongly reduced steady-state levels of PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 mRNAs in the respective amiRNA overexpression lines (Fig. 2A). However, PpFtsZ2-1 transcript levels were reduced to 1% to 2% in PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA lines, whereas PpGNT1 mRNA levels dropped to 10% to 20% in PpGNT1-amiRNA lines when compared to wild-type plants. Furthermore, the efficiency of posttranscriptional silencing of PpFtsZ2-1 was similar in all three amiRNA overexpression lines, even though they differed with respect to the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA accumulation (Fig. 1D), whereas the reduction of PpGNT1 transcript levels correlated with the PpGNT1-amiRNA expression levels. From these results, we conclude that amiRNAs confer efficient down-regulation of their target mRNAs in Physcomitrella. As a control, we also analyzed the steady-state levels of the sequence-related PpFtsZ2-2 mRNA in PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA overexpression lines. In agreement with the absence of amiRNA-induced mRNA cleavage products, PpFtsZ2-2 transcript levels were similar in wild-type and the three PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA lines (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Expression analysis of PpFtsZ2-1, PpFtsZ2-2, and PpGNT1, and detection of transitive siRNAs. A, Left, RNA gel blots (20 μg each) from wild type (WT) and PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA overexpression lines (1–3) hybridized with PpFtsZ2-1 and PpFtsZ2-2 probes; right, RNA gel blots (20 μg each) from wild type (WT) and PpGNT1-amiRNA overexpression lines (1 and 2) hybridized with a PpGNT1 probe. The ethidium bromide-stained gels below indicate equal loading. The hybridization signals were normalized to the rRNA bands, and the PpFtsZ2-1, PpFtsZ2-2, and PpGNT1 expression levels in wild type were set to 1. Numbers indicate the relative PpFtsZ2-1, PpFtsZ2-2, and PpGNT1 mRNA levels. B, Scheme illustrating the generation of transitive siRNAs from amiRNA target cleavage products requiring an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) to generate dsRNA, which is subsequently processed into siRNAs. Black line, mRNA; gray box, amiRNA binding site; curved line, amiRNA. C, Detection of sense and antisense transitive siRNAs produced from PpFtsZ2-1 (left) and PpGNT1 (right) mRNA cleavage products by RNA gel blots hybridized with oligonucleotides derived from regions downstream of the amiRNA binding sites. Hybridization with an antisense probe for U6snRNA served as control.

The 5′ RACE-PCR experiments performed with one of the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA lines yielded additional fragments that differed substantially in size from the expected cleavage products (Fig. 1E). After amiRNA-mediated cleavage of the mRNA, the cleavage products may serve as templates for synthesizing cRNA by RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Vaistij et al., 2002) leading to the formation of dsRNA. Subsequently, the dsRNA may be processed into secondary siRNAs, resulting in spreading of the initial amiRNA signal (Fig. 2B). This mechanism, known as transitivity, usually is initiated by dsRNA triggers. In plants, the transitivity occurs in both directions of the initial dsRNA trigger (Moissiard et al., 2007), whereas in animals, spreading of the initial signal occurs only upstream of the trigger (Pak and Fire, 2007). However, the onset of transitivity is a rare event after miRNA-mediated target cleavage (Howell et al., 2007; Moissiard et al., 2007) and is normally not observed after amiRNA-mediated target cleavage (Schwab et al., 2006). To investigate the possibility of transitivity, we used sense and antisense oligonucleotides derived from PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 mRNA regions downstream of the amiRNA recognition site for RNA gel-blot analysis. Sense and antisense siRNAs were only detected in PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA lines, respectively, but not in wild type (Fig. 2C). We conclude that amiRNAs allow for efficient down-regulation of mRNAs in Physcomitrella and the generation of transitive siRNAs from mRNA cleavage products may amplify the initial amiRNA trigger. However, the transitive effects are apparently not sufficient to have a major impact on sequence-related genes, as the PpFtsZ2-2 steady-state RNA levels were unaffected in PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA overexpression lines (Fig. 2A).

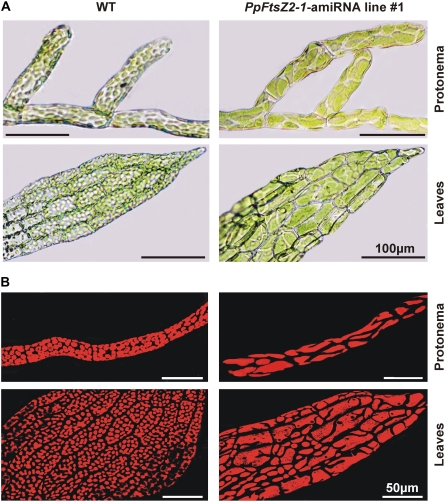

PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA Overexpressors Phenocopy PpFtsZ2-1 Null Mutants

In this study, we have chosen two genes to evaluate the use of an amiRNA expression system in Physcomitrella. The targeted deletion of PpGNT1 that is involved in the N-glycosylation of proteins did not cause any phenotypic deviations (Koprivova et al., 2003). In agreement with this previous study, the two characterized PpGNT1-amiRNA lines were indistinguishable from Physcomitrella wild-type plants. In contrast, PpFtsZ2-1 null mutants, which were generated by targeted gene disruption and lack expression of PpFtsZ2-1 mRNA, are impeded in chloroplast division leading to the formation of macrochloroplasts (Strepp et al., 1998). In our study, the expression of PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA led to strongly reduced PpFtsZ2-1 mRNA levels. To compare knockout and amiRNA lines, we investigated the phenotypes of the three PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA lines. In all lines, the accumulation of the amiRNA targeting PpFtsZ2-1 resulted in impaired chloroplast division and the formation of macrochloroplasts that phenocopied the PpFtsZ2-1 null mutants (Fig. 3; Supplemental Fig. S2). The formation of macrochloroplasts in the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA lines was observed in all tissues and cells analyzed indicating an efficient production of mature amiRNAs from constitutively expressed precursor transcripts. Furthermore, we did not observe any particular phenotypic differences among the transgenic lines expressing the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA, which is consistent with the similar degree of PpFtsZ2-1 mRNA reduction. Our results demonstrate that the expression of amiRNAs in Physcomitrella leads to efficient silencing of their target mRNAs comparable to the effects of targeted gene knockouts.

Figure 3.

Impeded plastid division and formation of macrochloroplasts in PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA overexpressors. A, Light microscopy from protonema and leaves of wild type (WT) and one PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA overexpression line (size bars, 100 μm). B, Confocal laser-scanning microscopy from protonema and leaves of wild type (WT) and one PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA overexpression line (size bars, 50 μm). Red, Chlorophyll autofluorescence in plastids. See Supplemental Figure S2 for phenotypes of the other two PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA lines.

DISCUSSION

The successful use of amiRNAs for the specific down-regulation of genes was shown for the dicotyledonous plants Arabidopsis, tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), and for the monocot rice (Oryza sativa; Parizotto et al., 2004; Alvarez et al., 2006; Niu et al., 2006; Schwab et al., 2006; Qu et al., 2007; Ossowski et al., 2008; Warthmann et al., 2008). In most cases, the amiRNA was expressed from endogenous miRNA precursors. However, high expression rates of amiRNAs were achieved in tobacco and tomato using the Arabidopsis miR164b precursor sequence indicating correct processing of conserved pre-miRNAs within seed plants (Alvarez et al., 2006). In our study, we tested the application of amiRNAs for the specific silencing of genes in the bryophyte Physcomitrella making use of an amiRNA expression system, where the Arabidopsis miR319a precursor serves as the backbone for amiRNA expression and subsequent maturation and was developed to control gene expression in Arabidopsis (Schwab et al., 2006). The miR319 family belongs to the highly conserved amiRNA families, even over large evolutionary distances, and was also found in Physcomitrella (Arazi et al., 2005; Jones-Rhoades et al., 2006; Fattash et al., 2007). Notably, miR319 stands out in that there is also considerable sequence conservation in the foldback, not only in the miRNA itself. Our comparison of the Arabidopsis miR319a precursor and the Physcomitrella miR319 precursor sequences confirmed nucleotide sequence conservation outside the miRNA/miRNA* region, implying similar foldback structures of the Arabidopsis and Physcomitrella miR319 pre-miRNAs. Indeed, we detected the correct processing of a mature 21-nt PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA, respectively, from the Arabidopsis miR319a precursor in transgenic Physcomitrella lines, indicating that the reconstructed miR319a pre-miRNA contains the essential recognition and processing information to enter the Physcomitrella miRNA biogenesis pathway. The PpFtsZ2-1 mRNA cleavage products were, however, offset by 1 and 2 nt relative to the expected products (Llave et al., 2002), suggesting that the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA was shifted by 1 or 2 nt, respectively, relative to the intended amiRNA. A similar effect has been observed for some Arabidopsis amiRNAs (Schwab et al., 2006). Because the originally designed amiRNAs were perfectly complementary, the shifted amiRNAs should still adhere to the targeting rules for miRNAs. The observation of shifted cleavage products suggested that release of the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA/miRNA* duplex from the precursor was not always precise, consistent with observations on endogenous miRNAs (Rajagopalan et al., 2006). Nevertheless, the Arabidopsis miR319a precursor can be used routinely for the expression of amiRNAs in Physcomitrella as the apparent shift by 1 nt during the maturation of the amiRNA may result in a mismatch at the 3′ end of the miRNA, which is not affecting target mRNA cleavage (Schwab et al., 2005). Furthermore, cleavage of the PpFtsZ2-1 mRNA within the amiRNA recognition site indicates correct amiRNA/amiRNA* duplex recognition and amiRNA loading into the RISC complex.

Previous studies have shown that the transcript levels of amiRNA targets are in most cases anticorrelated with corresponding amiRNA levels (Schwab et al., 2006). Among PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA lines analyzed, the amiRNA expression levels varied 8-fold and 5-fold, respectively. Nevertheless, the amiRNA expression caused a similar reduction of PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 mRNA levels to 1% to 2% and 10% to 20%, respectively, compared to transcript levels in wild type. This suggests that the amount of amiRNAs is not limiting in any of the lines. Instead, it is likely that the competition of natural miRNAs and amiRNAs in RISC loading determines the efficiency of posttranscriptional silencing of the PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 transcripts.

The formation of macrochloroplasts in the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA lines indicated impeded plastid division and resembled the phenotype of PpFtsZ2-1 knockout lines, which completely lack a functional transcript (Strepp et al., 1998). We therefore conclude that the remaining PpFtsZ2-1 transcripts in the amiRNA lines are not able to generate sufficient PpFtsZ2-1 protein to support proper plastid division. In addition, amiRNA expression in the transgenic lines seems to be stable over long time periods as we did not observe any phenotypic reversion to wild-type plastids in the PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA overexpression lines after 1 year of subculture. We anticipate that the described amiRNA expression system will result in similar silencing efficiencies of any target gene and thus can be routinely used as an alternative to the generation of knockout mutants in Physcomitrella.

The efficient silencing of PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 by amiRNAs might be enhanced by the generation of transitive siRNAs, as we detected such siRNAs from the 3′ cleavage products of the PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1 mRNAs. Usually, transitive siRNAs are produced from exogenous RNA sequences such as viruses or sense transgene transcripts (Baulcombe, 2004), but the formation of transitive siRNAs from miRNA-guided cleavage products appears to be the exception (Howell et al., 2007; Moissiard et al., 2007). Furthermore, transitivity was suggested not to be a major factor contributing to amiRNA efficacy in previous studies, although this was inferred only indirectly from the lack of effects on sequence-related transcripts (Schwab et al., 2006; Warthmann et al., 2008). Although we cannot exclude that siRNAs, which are produced from amiRNA-mediated mRNA cleavage products, can affect other genes not targeted by the original amiRNA, the PpFtsZ2-1 homolog PpFtsZ2-2, which shares high identity in sequence stretches of the coding region (Supplemental Fig. S3), seemed unaffected in PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA lines. We detected neither cleavage products by 5′ RACE-PCR, indicating siRNA-mediated cleavage of PpFtsZ2-2 transcripts, nor reduced PpFtsZ2-2 steady-state mRNA levels, pointing to a posttranscriptional silencing of this gene. Thus, even though transitivity might be more common in Physcomitrella, the specificity of posttranscriptional silencing is apparently sufficient to silence single members of highly conserved gene families. Moreover, it might be preferable to design amiRNAs lacking perfect sequence complementarity at the 3′ end, as this reduces transitivity (Moissiard et al., 2007).

CONCLUSION

Compared to the conventional targeted gene knockout approach in Physcomitrella, the expression of amiRNA provides several advantages. (1) The generation and molecular analysis of amiRNA overexpression lines is sped up as each regenerated transgenic line harboring an amiRNA expression construct and should produce the desired mature amiRNA. (2) Instead of the generation of multigene knockout lines, which is experimentally difficult, but feasible (Hohe et al., 2004), amiRNAs are likely to be particularly useful for targeting groups of closely related genes (Alvarez et al., 2006; Schwab et al., 2006). (3) AmiRNAs can be expressed from inducible or tissue-specific promoters (Schwab et al., 2006) enabling the analysis of genes with essential functions that cannot be analyzed by targeted gene disruption. Provided that other amiRNAs have a similar effect on the knock down of their cognate target genes in Physcomitrella as observed in this study, they can be considered as an efficient alternative tool to the targeted gene knockout approach for reverse genetics studies in Physcomitrella.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Physcomitrella patens plants were cultured in modified liquid Knop medium containing 250 mg L−1 KH2PO4, 250 mg L−1 KCl, 250 mg L−1 MgSO4·7H2O, 1,000 mg L−1 Ca(NO3)2, and 12.5 mg L−1 FeSO4·7H2O (pH 5.8) or on solid Knop plates. Erlenmeyer flasks containing 400 mL of suspension culture were agitated on a rotary shaker at 120 rpm at 25°C under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark regime (Philips TLD 25; 50 μm m−2 s−1). Liquid cultures were mechanically disrupted every week to maintain the plants in the protonema stage. Gametophore development was induced by transferring protonema tissue to solidified Knop medium.

Transformation of Physcomitrella Protoplasts

Polyethylene glycol-mediated transformation of Physcomitrella protoplasts was performed according to standard procedures (Frank et al., 2005). Briefly, transformation was carried out using 25 μg of linearized plasmid DNA. Transformed protoplasts were cultivated for 24 h under standard conditions in the dark and were then transferred to light. After 10 d, the protoplasts were transferred to solid Knop medium. Three days later, regenerating plants were transferred to Knop medium supplemented with hygromycin (Promega). The selection lasted 2 weeks and was followed by a 2-week release period on Knop medium without antibiotic followed by another round of selection and release. Plants surviving the second round of selection were screened by PCR to confirm integration of the DNA construct.

Generation of Physcomitrella Lines Expressing AmiRNAs Targeting PpFtsZ2-1 and PpGNT1

AmiRNAs targeting PpFtsZ2-1 (accession no. AJ001586; amiRNA, 5′-TTCGTAATTAACGTGTCCGCG-3′) and PpGNT1 (accession no. AJ429143; amiRNA, 5′-TTCCAAATAATCAGGACGCTT-3′) were designed using the amiRNA designer interface WMD (Schwab et al., 2006; Ossowski et al., 2008). The PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA and PpGNT1-amiRNA sequences were introduced into the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) miR319a precursor by overlapping PCR using the following primers. PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA, miRNA-sense, 5′-GATTCGTAATTAACGTGTCCGCGTCTCTCTTTTGTATTCC-3′; miRNA-antisense, 5′-GACGCGGACACGTTAATTACGAATCAAAGAGAATCAATGA-3′; miRNA*-sense, 5′-GACGAGGACACGTTATTTACGATTCACAGGTCGTGATATG-3′; miRNA*-antisense, 5′-GAATCGTAAATAACGTGTCCTCGTCTACATATATAT-TCCT-3′; primer A, 5′-CCCGGGTGCAGCCCCAAACACACGCTC-3′; primer B, 5′-GGATCCCCCCATGGCGATGCCTTAAAT-3′. PpGNT1-amiRNA, miRNA-sense, 5′-GATTCCAAATAATCAGGACGCTTTCTCTCTTTTGTATTCC-3′; miRNA-antisense, 5′-GAAAGCGTCCTGATTATTTGGAATCAAAGAGAATCAATGA-3′; miRNA*-sense, 5′-GAAAACGTCCTGATTTTTTGGATTCACAGGTCGTGATATG-3′; miRNA*-antisense, 5′-GAATCCAAAAAATCAGGACGTTTTCTACATATATATTCCT-3′; same primers A and B as described above. The plasmid pRS300 harboring the Arabidopsis miR319a precursor was used as PCR template (Schwab et al., 2006). The resulting precursor fragments were cloned into the pJET1.2 cloning vector (Fermentas) and sequenced. The modified ath-miRNA319a precursor DNA fragments were cloned into SmaI and BamHI sites of the plant expression vector pPCV (Koncz et al., 1989) containing the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, nos terminator, and hpt selection marker cassette. Transgenic lines were analyzed by PCR to identify lines that had integrated the amiRNA overexpression constructs using the primers 5′-TGATATCTCCACTGACGAAAGGG-3′ and 5′-GGATCCCCCCATGGCGATGCCTTAAAT-3′. PCR primers for the amplification of the Physcomitrella control gene EF1α were 5′-AGCGTGGTATCACAATTGAC-3′ and 5′-GATCGCTCGATCATGTTATC-3′. The one-step isolation of genomic DNA was performed according to the method of Schween et al. (2002).

Small RNA Blots

Total RNA was isolated from protonema using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and separated in a 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gel containing 8.3 m urea in Tris-borate/EDTA buffer. The RNA was electroblotted onto nylon membranes for 1 h at 400 mA. Radiolabeled probes were generated by end labeling of DNA oligonucleotides with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The following probes were used. Antisense probe for PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA, 5′-CGCGGACACGTTAATTACGAA-3′; antisense probe for PpGNT1-amiRNA, 5′-AAGCGTCCTGATTATTTGGAA-3′; detection of sense transitive PpFtsZ2-1 siRNAs, 5′-CCCCAGTGACGGAAGCGTTCAATCTTGCAGACGACATCCTTCGGC-3′; detection of antisense transitive PpFtsZ2-1 siRNAs, 5′-GCCGAAGGATGTCGTCTGCAAGATTGAACGCTTCCGTCACTGGGG-3′; detection of sense transitive PpGNT1 siRNAs, 5′-GTGAATTTCCTGCAGCATTTAGATGAAAATCCTCCCAAGACAAGG-3′; detection of antisense transitive PpGNT1 siRNAs, 5′-CCTTGTCTTGGGAGGATTTTCATCTAAATGCTGCAGGAAATTCAC-3′; detection of the U6snRNA control, 5′-GGGGCCATGCTAATCTTCTCTG-3′. Blot hybridization was carried out in 0.05 m sodium phosphate (pH 7.2), 1 mm EDTA, 6× SSC, 1× Denhardt's, 5% SDS. Blots were washed three times with 2× SSC, 0.2% SDS, and one time with 1× SSC, 0.1% SDS. Blots were hybridized and washed at temperatures 5°C below the melting temperature of the oligonucleotide.

Detection of mRNA Cleavage Products

Synthesis of 5′ RACE-ready cDNAs was carried out according to Zhu et al. (2001) using the BD Smart RACE cDNA amplification kit (CLONTECH). Subsequent PCR reactions were performed using the UPM Primer-Mix supplied with the kit in combination with gene-specific primers derived from the target gene PpFtsZ2-1 (5′-GACTATCCCTGTGGCTCGCTCAATACCC-3′), a PpFtsZ2-1 nested primer (5′-CCAATAGAGGAGATTGGATTGCGCTCA-3′), a gene-specific primer derived from the gene PpFtsZ2-2 (5′-CCAATACGCGACTTGCATACTGCATAC-3′), and a gene-specific primer derived from the gene PpGNT1 (5′-ACTTTGGAGCAAGTTCTTCCCAGGTGGA-3′). Amplification products corresponding to the size of the expected cleavage products were excised from the gel, cloned and sequenced.

Total RNA Gel Blots

Twenty micrograms of total RNA were mixed with an equal volume of RNA denaturing buffer and incubated for 10 min at 65°C. The RNA gel was blotted to a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (GE Healthcare) using a Turbo blotter (Schleicher & Schuell) with 20× SSC. RNA was fixed by UV cross-linking. Hybridization was carried out with an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled DNA probe derived from PpFtsZ2-1 amplified with primers 5′-AGACACGTCATTAAAGGT-3′ and 5′-TAAGTGTGCAAGAAGATA-3′, a probe derived from PpFtsZ2-2 amplified with primers 5′-AAGGTAGTACAAATGGGATGGC-3′ and 5′-TCATTAAGTCTGCCACTCCAC-3′, and a probe derived from PpGNT1 amplified with primers 5′-GCACTCTCGATCGGATTCTC-3′ and 5′-TCGGGAGAGATTTCCATGTC-3′. DNA labeling was carried out with the Rediprime II random prime labeling kit (GE Healthcare). Prehybridization was carried out at 67°C for 4 h, subsequent hybridization at 67°C overnight. Blots were washed three times with 0.5× SSC, 0.1% SDS, and one time with 1× SSC, 0.1% SDS at 67°C. Signals were detected using the Molecular Imager FX (Bio-Rad).

Microscopy

For microscopic analyses, we used the Axioplan 2 epifluorescence microscope equipped with an AttoArc HBO 100-W bulb and the stereomicroscope Stemi 2000-C (Carl Zeiss). Image acquisition was achieved using the Canon digital camera EOS D300 (Canon), and confocal laser-scanning microscopy (TCS 4D; Leica).

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers AJ001586 (PpFtsZ2-1), XM_001766723 (PpFtsZ2-2), and AJ429143 (PpGNT1).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Analysis of Physcomitrella and Arabidopsis miR319 precursors.

Supplemental Figure S2. Impeded plastid division and formation of macrochloroplasts in PpFtsZ2-1-amiRNA overexpressors.

Supplemental Figure S3. Nucleotide sequence alignment of PpFtsZ2-1 and PpFtsZ2-2 coding regions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Andras Viczian for providing the pPCV expression vector, Enas Qudeimat for assisting with confocal laser-scanning microscopy, and Björn Voß and Isam Fattash for advice on miR319 precursor sequence analysis.

This work was supported by the Landesstiftung Baden-Württemberg (grant no. P–LS–RNS/40 to W.F., R.R., and D.W.), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Freiburg Initiative for Systems Biology grant no. 0313921 to R.R. and W.F.), the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal State Governments (Biological Signaling Studies grant no. EXC294 to R.R.), and European Community FP6 IP SIROCCO (contract no. LSHG–CT–2006–037900 to D.W.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Wolfgang Frank (wolfgang.frank@biologie.uni-freiburg.de).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Alvarez JP, Pekker I, Goldshmidt A, Blum E, Amsellem Z, Eshed Y (2006) Endogenous and synthetic microRNAs stimulate simultaneous, efficient, and localized regulation of multiple targets in diverse species. Plant Cell 18 1134–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin AA, Lagos-Quintana M, Yalcin A, Zavolan M, Marks D, Snyder B, Gaasterland T, Meyer J, Tuschl T (2003) The small RNA profile during Drosophila melanogaster development. Dev Cell 5 337–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arazi T, Talmor-Neiman M, Stav R, Riese M, Huijser P, Baulcombe DC (2005) Cloning and characterization of micro-RNAs from moss. Plant J 43 837–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell MJ, Bowman JL (2008) Evolution of plant microRNAs and their targets. Trends Plant Sci 13 343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell MJ, Jan C, Rajagopalan R, Bartel DP (2006) A two-hit trigger for siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell 127 565–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell MJ, Snyder JA, Bartel DP (2007) Common functions for diverse small RNAs of land plants. Plant Cell 19 1750–1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulcombe D (2004) RNA silencing in plants. Nature 431 356–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla M, Pan A, Quatrano RS (2003) RNA interference in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Physiol 133 470–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla M, Perroud PF, Pan A, Klueh P, Quatrano RS (2005) An RNAi system in Physcomitrella patens with an internal marker for silencing allows for rapid identification of loss of function phenotypes. Plant Biol 7 251–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen P, Sakvarelidze-Achard L, Bruun-Rasmussen M, Dunoyer P, Yamamoto YY, Sieburth L, Voinnet O (2008) Widespread translational inhibition by plant miRNAs and siRNAs. Science 320 1185–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman EJ, Carrington JC (2007) Specialization and evolution of endogenous small RNA pathways. Nat Rev Genet 8 884–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho F, Gheysen G, Kushnir S, Van Montagu M, Inze D, Castresana C (1992) Suppression of beta-1,3-glucanase transgene expression in homozygous plants. EMBO J 11 2595–2602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egener T, Granado J, Guitton MC, Hohe A, Holtorf H, Lucht JM, Rensing SA, Schlink K, Schulte J, Schween G, et al (2002) High frequency of phenotypic deviations in Physcomitrella patens plants transformed with a gene-disruption library. BMC Plant Biol 2 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlgren N, Howell MD, Kasschau KD, Chapman EJ, Sullivan CM, Cumbie JS, Givan SA, Law TF, Grant SR, Dangl JL, et al (2007) High-throughput sequencing of Arabidopsis microRNAs: evidence for frequent birth and death of MIRNA genes. PLoS ONE 2 e219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattash I, Voss B, Reski R, Hess WR, Frank W (2007) Evidence for the rapid expansion of microRNA-mediated regulation in early land plant evolution. BMC Plant Biol 7 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank W, Decker EL, Reski R (2005) Molecular tools to study Physcomitrella patens. Plant Biol 7 220–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AJ, Baulcombe DC (1999) A species of small antisense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science 286 950–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohe A, Egener T, Lucht JM, Holtorf H, Reinhard C, Schween G, Reski R (2004) An improved and highly standardised transformation procedure allows efficient production of single and multiple targeted gene-knockouts in a moss, Physcomitrella patens. Curr Genet 44 339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell MD, Fahlgren N, Chapman EJ, Cumbie JS, Sullivan CM, Givan SA, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC (2007) Genome-wide analysis of the RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE6/DICER-LIKE4 pathway in Arabidopsis reveals dependency on miRNA- and tasiRNA-directed targeting. Plant Cell 19 926–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Bartel B (2006) MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57 19–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koncz C, Martini N, Mayerhofer R, Koncz-Kalman Z, Korber H, Redei GP, Schell J (1989) High-frequency T-DNA-mediated gene tagging in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86 8467–8471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koprivova A, Altmann F, Gorr G, Kopriva S, Reski R, Decker EL (2003) N-glycosylation in the moss Physcomitrella patens is organized similarly to that in higher plants. Plant Biol 5 582–591 [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara Y, Watanabe Y (2004) Arabidopsis micro-RNA biogenesis through Dicer-like 1 protein functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 12753–12758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V (1993) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75 843–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llave C, Xie Z, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC (2002) Cleavage of Scarecrow-like mRNA targets directed by a class of Arabidopsis miRNA. Science 297 2053–2056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory AC, Reinhart BJ, Jones-Rhoades MW, Tang G, Zamore PD, Barton MK, Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNA control of PHABULOSA in leaf development: importance of pairing to the microRNA 5′ region. EMBO J 23 3356–3364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke MA, Primig M, Trnovsky J, Matzke AJ (1989) Reversible methylation and inactivation of marker genes in sequentially transformed tobacco plants. EMBO J 8 643–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moissiard G, Parizotto EA, Himber C, Voinnet O (2007) Transitivity in Arabidopsis can be primed, requires the redundant action of the antiviral Dicer-like 4 and Dicer-like 2, and is compromised by viral-encoded suppressor proteins. RNA 13 1268–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JW, Jones JT, Meyer T, Ferrell JE Jr (2003) Recombinant Dicer efficiently converts large dsRNAs into siRNAs suitable for gene silencing. Nat Biotechnol 21 324–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli C, Lemieux C, Jorgensen R (1990) Introduction of a chimeric chalcone synthase gene into petunia results in reversible co-suppression of homologous genes in trans. Plant Cell 2 279–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu QW, Lin SS, Reyes JL, Chen KC, Wu HW, Yeh SD, Chua NH (2006) Expression of artificial microRNAs in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana confers virus resistance. Nat Biotechnol 24 1420–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossowski S, Schwab R, Weigel D (2008) Gene silencing in plants using artificial microRNAs and other small RNAs. Plant J 53 674–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak J, Fire A (2007) Distinct populations of primary and secondary effectors during RNAi in C. elegans. Science 315 241–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parizotto EA, Dunoyer P, Rahm N, Himber C, Voinnet O (2004) In vivo investigation of the transcription, processing, endonucleolytic activity, and functional relevance of the spatial distribution of a plant miRNA. Genes Dev 18 2237–2242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu J, Ye J, Fang R (2007) Artificial microRNA-mediated virus resistance in plants. J Virol 81 6690–6699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quatrano RS, McDaniel SF, Khandelwal A, Perroud PF, Cove DJ (2007) Physcomitrella patens: mosses enter the genomic age. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10 182–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan R, Vaucheret H, Trejo J, Bartel DP (2006) A diverse and evolutionarily fluid set of microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev 20 3407–3425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensing SA, Lang D, Zimmer AD, Terry A, Salamov A, Shapiro H, Nishiyama T, Perroud PF, Lindquist EA, Kamisugi Y, et al (2008) The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants. Science 319 64–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano N, Macino G (1992) Quelling: transient inactivation of gene expression in Neurospora crassa by transformation with homologous sequences. Mol Microbiol 6 3343–3353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer DG (2002) A new moss genetics: targeted mutagenesis in Physcomitrella patens. Annu Rev Plant Biol 53 477–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab R, Ossowski S, Riester M, Warthmann N, Weigel D (2006) Highly specific gene silencing by artificial microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18 1121–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab R, Palatnik JF, Riester M, Schommer C, Schmid M, Weigel D (2005) Specific effects of microRNAs on the plant transcriptome. Dev Cell 8 517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schween G, Fleig S, Reski R (2002) High-throughput-PCR screen of 15,000 transgenic Physcomitrella plants. Plant Mol Biol Rep 20 43–47 [Google Scholar]

- Strepp R, Scholz S, Kruse S, Speth V, Reski R (1998) Plant nuclear gene knockout reveals a role in plastid division for the homolog of the bacterial cell division protein FtsZ, an ancestral tubulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95 4368–4373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmor-Neiman M, Stav R, Klipcan L, Buxdorf K, Baulcombe DC, Arazi T (2006) Identification of trans-acting siRNAs in moss and an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase required for their biogenesis. Plant J 48 511–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretter EM, Alvarez JP, Eshed Y, Bowman JL (2008) Activity range of Arabidopsis small RNAs derived from different biogenesis pathways. Plant Physiol 147 58–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaistij FE, Jones L, Baulcombe DC (2002) Spreading of RNA targeting and DNA methylation in RNA silencing requires transcription of the target gene and a putative RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Plant Cell 14 857–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaucheret H, Vazquez F, Crete P, Bartel DP (2004) The action of ARGONAUTE1 in the miRNA pathway and its regulation by the miRNA pathway are crucial for plant development. Genes Dev 18 1187–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidali L, Augustine RC, Kleinman KP, Bezanilla M (2007) Profilin is essential for tip growth in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 19 3705–3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warthmann N, Chen H, Ossowski S, Weigel D, Herve P (2008) Highly specific gene silencing by artificial miRNAs in rice. PLoS ONE 3 e1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse PM, Wang MB, Lough T (2001) Gene silencing as an adaptive defence against viruses. Nature 411 834–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Wagner EJ, Cullen BR (2002) Both natural and designed micro RNAs can inhibit the expression of cognate mRNAs when expressed in human cells. Mol Cell 9 1327–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YY, Machleder EM, Chenchik A, Li R, Siebert PD (2001) Reverse transcriptase template switching: a SMART approach for full-length cDNA library construction. Biotechniques 30 892–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.