Summary

The core planar polarity proteins play important rôles in coordinating cell polarity, in part by adopting asymmetric subcellular localisations that are likely to serve as cues for cell polarisation by as yet uncharacterised pathways. Here we describe the rôle of Multiple Wing Hairs (Mwh), a novel Formin Homology 3 domain protein, which acts downstream of the core polarity proteins to restrict the production of actin-rich prehairs to distal cell edges in the Drosophila pupal wing. Mwh appears to function as a repressor of actin filament formation, and in its absence ectopic actin bundles are seen across the entire apical surface of cells. We show that the proximally localised core polarity protein Strabismus acts via the downstream effector proteins Inturned, Fuzzy and Fritz to stabilise Mwh in apico-proximal cellular regions. In addition the distally localised core polarity protein Frizzled positively promotes prehair initiation, suggesting that both proximal and distal cellular cues act together to ensure accurate prehair placement.

Keywords: Planar polarity, Multiple Wing Hairs, Drosophila, cell polarity, Frizzled, actin

Introduction

The development of multicellular organisms requires the coordinated specification of both cell fates and cell polarities. One example of coordinated cell polarisation is “planar polarity” whereby cells within epithelial sheets adopt uniform polarities relative to the plane of the tissue. Although widespread in nature, the mechanisms underlying the establishment of planar polarity have been most studied in insect cuticles, nevertheless essential rôles in vertebrate development are now recognised (reviewed in Strutt, 2003; Klein and Mlodzik, 2005; Wang and Nathans, 2007).

In many contexts, a key event in the coordinated planar polarisation of epithelia is the asymmetric subcellular localisation of a group of “core” planar polarity proteins to opposite cell edges. This process is best studied in the Drosophila pupal wing, in which the sevenpass transmembrane protein Frizzled (Fz) and the cytoplasmic proteins Dishevelled (Dsh) and Diego (Dgo) localise to distal apicolateral junctional regions, the fourpass transmembrane protein Strabismus (Stbm, also known as Van Gogh) and the cytoplasmic protein Prickle (Pk) localise proximally, and the sevenpass transmembrane cadherin Flamingo (Fmi, also known as Starry Night) localises both distally and proximally (reviewed in Klein and Mlodzik, 2005). The localisations of the core proteins define distinct distal and proximal apicolateral membrane domains, which are thought to act as cues for subsequent cell polarisation events mediated by downstream “effector” genes.

The best characterised morphogenetic event regulated by the asymmetric localisation of the core polarity proteins is the production of a single distally pointing trichome from each cell of the wing blade (Gubb and García-Bellido, 1982; Wong and Adler, 1993). Trichome formation begins with increased actin bundling close to the distal cell vertex at about 32 hours of pupal life, leading to formation of a “prehair” that contains both F-actin and microtubules (Mitchell et al., 1983; Wong and Adler, 1993; Eaton et al., 1996; Turner and Adler, 1998). Electron microscopy has revealed that shortly prior to prehair formation, the apical cell surface is covered in electron dense “pimples” (Guild et al., 2005) which are believed to be precursors for microvillus formation. Prehair initiation is manifested by actin bundles sprouting from a region covering several pimples close to the distal vertex. This suggests that it is the local activation of pimples to polymerise actin, which specifies the site of prehair formation.

Four genes have been identified which act downstream of the core polarity proteins to specify the site of prehair initiation, namely inturned (in), fuzzy (fy), fritz (frtz) and multiple wing hairs (mwh) (Gubb and García-Bellido, 1982; Wong and Adler, 1993; Lee and Adler, 2002; Collier et al., 2005). Interestingly, whereas loss of core polarity protein function (and thus of asymmetric localisation) causes formation of a single prehair in the cell centre, loss of function of these downstream effectors leads to formation of multiple prehairs at cell edges. This led to the suggestion that the downstream effectors repress prehair formation throughout the cell periphery, whereas the core planar polarity proteins promote prehair formation at the distal cell edge by locally counteracting the effectors (Wong and Adler, 1993).

The best studied effectors are in, fy and frtz, which all act cell-autonomously upstream of mwh (Gubb and García-Bellido, 1982; Wong and Adler, 1993; Park et al., 1996; Collier and Gubb, 1997; Collier et al., 2005) and encode respectively a putative two-pass transmembrane protein, a putative four-pass transmembrane protein and a WD40-repeat cytoplasmic protein. Interestingly, the ectopic trichome phenotype of null alleles of all three loci is enhanced at lower temperatures, leading to the suggestion that these proteins act in a microtubule-dependent process (Adler et al., 1994).

An important recent observation is that the In protein localises at the proximal apicolateral edges of wing cells under control of the core polarity proteins, shortly prior to prehair formation (Adler et al., 2004). This localisation also requires the activity of fy and frtz, but not mwh. Two alternative models have been put forward to explain the requirement of proximally localised In for distal prehair initiation: either In might promote local formation of a repressor of prehair initiation, thus restricting initiation to distal regions; alternatively, In could act positively to promote polarised transport of a factor required for prehair initiation to the distal cell edge (Adler et al., 2004). Both models challenged the existing assumption that distally localised Fz/Dsh act as the primary determinants for prehair initiation, and instead suggest that proximally localised Stbm/Pk may be the critical cue.

The phenotype of mwh is stronger than that of in, fy or frtz, displaying more inappropriate prehair initiations per cell (Wong and Adler, 1993), and as it acts, by genetic criteria, downstream of the other effectors, it is the factor most likely to interact directly with the actin cytoskeleton, perhaps by acting as a repressor of pimple activation. However, thus far the molecular identity of the gene product of mwh is unknown.

The widespread requirements of core planar polarity protein activity in invertebrate and vertebrate morphogenesis, and the associated observation of asymmetric core protein subcellular localisation, suggests that it will be important to understand how the “distal” Fz/Dsh cue and/or the “proximal” Stbm/Pk cue control cell shape and behaviour by modulating the cytoskeleton. Significantly, homologues of the effectors In and Fy have already been found to play critical rôles in vertebrate embryogenesis (Park et al., 2006). In this study, we seek to understand the mechanisms by which the core planar polarity proteins and their effectors restrict prehair initiation to the distal cell vertex during Drosophila wing development.

Materials and Methods

Alleles and transgenes are described in FlyBase, except for P{w+, ActP-FRT-PolyA-FRT-EGFP-Fy} and P{w+, ActP-FRT-PolyA-FRT-EGFP-CG13913} (this study). Mitotic clones were generated using the FLP/FRT system (Xu and Rubin, 1993) and Ubx-FLP (Emery et al., 2005), twinclones were generated as previously described (Strutt and Strutt, 2007). Overexpression was using GAL4/UAS (Brand and Perrimon, 1993).

Pupae were aged at 25°C unless indicated and wings and cells were processed for immunofluorescence as previously (Strutt, 2001) except in some cases to improve labelling of actin structures the fixative was supplemented with 1% Triton-X100 and 1:200 Phalloidin-Alexa-568. Primary antibodies were 1:400 mouse monoclonal anti-ßgal (Promega), 1:4000 rabbit anti-ßgal (Cappel), 1:4000 rabbit anti-GFP (Abcam), 1:10 mouse monoclonal anti-Fmi#74 (DSHB, Usui et al., 1999), 1:200 mouse monoclonal anti-Arm (DSHB), 1:1000 rat anti-Dsh (Strutt et al., 2006), 1:1000 rat or 1:100 rabbit anti-Mwh, 1:1000 rat or 1:100 rabbit anti-Frtz, 1:200 mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin DM1A (Sigma). Actin was visualised using 1:200 Texas-Red or Alexa-568-phalloidin (Molecular Probes). Confocal Z-stacks were captured on a Leica SP confocal, and average projections of several Z-planes made to provide a final image depth of ∼1μm. Fluorescent intensities were quantitated using ImageJ.

ESTs containing the coding sequences of fy (AT05453), frtz (RH72421) and CG13913 (RE53394) were obtained from DGRC. EGFP-Fy and EGFP-CG13913 expressing flies were generated by fusing EGFP to the N-terminus of the coding sequence and cloning into the transformation vector pP{w+, ActP-FRT-PolyA-FRT-PolyA} (Strutt, 2001). Germline transformations were performed by BestGene. EGFP-CG13913 was expressed in cultured Drosophila S2 cells using pP{w+, ActP-FRT-PolyA-FRT-EGFP-CG13913} transfected using Effectene (Qiagen), with cotransfection of pActP-FLP to excise the FRT-PolyA-FRT cassette.

Frtz and Mwh antibodies were generated in rats and rabbits against His-tagged fusion proteins corresponding to amino acids 670-951 and 440-836 respectively, with rabbit sera being affinity purified against the same fusion protein.

The breakpoint in mwh1 was isolated by inverse PCR, identifying an inversion following amino acid 367, which breaks within the conserved FH3 domain, leading us to believe that this may result in a null allele. In support of this, we scored mwh1 as amorphic in the wing, with the adult trichome phenotype of mwh1 homozygotes being indistinguishable from that of hemizygotes (D.S. unpublished).

Protein extracts for immunoblotting were prepared by dissecting pupal wings directly into sample buffer and running the equivalent of one wing per lane. For phosphatase experiments, wings were dissected into lysis buffer on ice (50mM Tris-HCl ph7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, protease inhibitors (Roche)) supplemented with 1μM phosphatase inhibitor microcystin for control samples. Experimental samples were treated with 400 U lambda phosphatase (NEB) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Proteins were detected using 1:500 affinity purified rabbit anti-Mwh, 1:5000 anti-Actin AC40 (Sigma) or 1:10000 anti-α-tubulin DM1A (Sigma).

Results

Rôles of the “proximal” and “distal” cues in specifying the site of prehair initiation

To assess the requirements for potential prehair initiation cues provided by localisation of the core polarity proteins Fz/Dsh/Dgo distally or Stbm/Pk proximally, we generated cells that contained only one of these cues at a known cell edge. In cells lacking fz, Dsh/Dgo are no longer recruited to the junctions (Axelrod, 2001; Shimada et al., 2001; Das et al., 2004), but at cell edges touching non-mutant cells, Stbm/Pk are strongly recruited (Tree et al., 2002; Bastock et al., 2003), giving rise to a localised “proximal” cue in a cell lacking a “distal” cue. Strikingly, in such cells containing just a “proximal” cue, prehair initiation is still seen to occur at the opposite cell edge (Fig.1B).

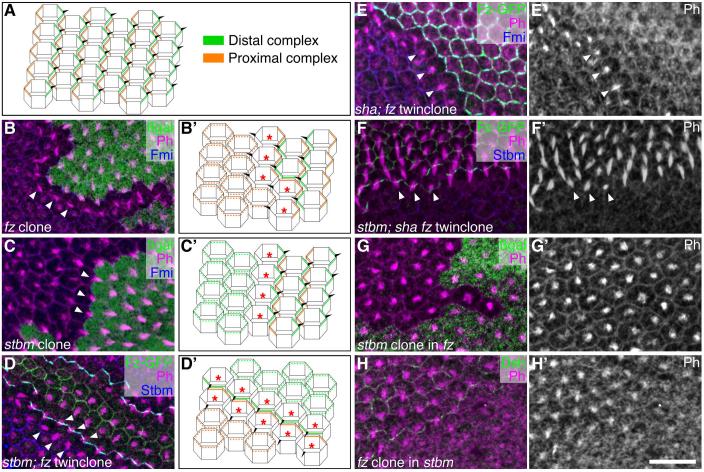

Figure 1. Core polarity gene function and the site of prehair initiation.

32 hour pupal wings immunolabelled for actin (magenta or white), clonal marker (lacZ, fz-EGFP or dsh expression, green) and Fmi or Stbm (blue). Arrowheads indicate prehairs initiating at edges of mutant cells touching a mitotic clone boundary. Distal is to the right in this and subsequent figures. Scale bar in panel H’ represents 10μm. Diagrams (A, B’-D’) illustrate sites of core polarity protein localisation (Fz/Dsh distal complex in green, Stbm/Pk proximal complex in orange) in wildtype or on edges of clones, and observed sites of prehair initiation, first row of mutant cells in each clone marked with asterisks. Sites of prehair initiation in mutant cells away from clone edges are not illustrated but are at the cell centre, except as noted in the text for the first rows of cells within stbm tissue.

(A) Diagram of normal localisation of distal and proximal core polarity proteins and site of prehair initiation in wildtype wings.

(B) fz21 clone. Note prehair initiation is delayed in mutant cells away from clone edge. Normal polarity is reversed in non-mutant cells due to the influence of the clone (Vinson and Adler, 1987).

(C) stbm6 clone. Note prehair initiation is less delayed than in fz clones, and more likely to be towards a cell edge.

(D) stbm6/fz21 twinclone.

(E) sha1/fz21 twinclone.

(F) stbm6/sha fz21 twinclone.

(G) stbm6 clone in a fz21 background.

(H) fz21 clone in a stbm6 background. Note that fz mutant cells are marked by loss of Dsh junctional recruitment (Shimada et al., 2001).

However, in fz cells away from the clone edge, prehair initiation occurs in the cell centre as previously reported (Wong and Adler, 1993), but is noticeably delayed.

Patches of cells lacking stbm activity, present the opposite situation, in which no “proximal” cue is present, but in cells touching non-mutant cells, a “distal” cue containing Fz/Dsh assembles (Strutt, 2001; Bastock et al., 2003). Cells containing only a localised “distal” cue also initiate a prehair at the site of this cue, despite the lack of a “proximal” cue at the opposite cell edge (Fig.1C). Notably, stbm mutant cells within the clone show a smaller delay in prehair initiation compared to fz tissue. In addition, prehair initiation is only consistently seen in the cell centre in the fourth row of cells away from the clone edge. In the third row of cells, about half produce a prehair that is positioned towards the cell edge nearest to the clone boundary, whereas in the second row of mutant cells almost all prehairs initiate closer to the cell edge nearest the clone boundary.

To compare further the effects on prehair initiation of cells only having a “distal” or “proximal” cue, we generated wings containing clones of fz mutant cells abutting clones of stbm mutant cells (fz; stbm twinclones) (Strutt and Strutt, 2007). At the boundary between the fz and stbm clones, the core polarity proteins show normal asymmetric localisation, but the neighbouring cells are all mutant and fail to asymmetrically localise core polarity proteins. Hence, we can rule out any potential influence of asymmetric core protein localisation in neighbouring cells on the site of prehair initiation, and focus on the effects of the asymmetric localisation straddling a single cell-cell boundary. Consistent with the results around isolated fz and stbm clones, cells containing a “distal” cue initiate a prehair at this cell edge, whereas the neighbours containing a “proximal” cue assemble a prehair towards the opposite cell edge (Fig.1D). We again see a greater delay in prehair initiation in fz mutant cells not on the clone edge, versus stbm mutant cells, and also that the second row of stbm mutant cells have a site of prehair initiation that is influenced by their polarised neighbours on the clone edge.

Taken together, these results suggest that asymmetric localisation of the core polarity proteins across cell junctions, provides both a “distal” cue for prehair initiation, which promotes initiation at the same cell edge, and a “proximal” cue that promotes initiation towards the opposite cell edge. It should be noted, that a “distal” cue is always associated with a “proximal” cue in the next cell, and vice versa, by virtue of the mutually dependent localisations of the core polarity proteins. Thus it is formally possible that only one of these cues has a direct effect on the site of prehair initiation, and that the apparent effect of the other cue is due to a signal from the adjacent cell.

One way in which an adjacent cell might influence prehair formation in a neighbour, would be if assembly of a prehair produced a physical cue that influences the cytoskeleton of the neighbouring cell and induces prehair formation at the opposite edge. To test this hypothesis, we generated mutant cells containing only a “proximal” or “distal” polarity cue, juxtaposed to cells that are unable to form a prehair, by virtue of being mutant for shavenoid (sha) (Ren et al., 2006). Interestingly, cells on the edges of a fz clone, adjacent to sha cells, form prehairs at the expected cell edge, despite the lack of prehairs in neighbouring cells (Fig.1E). Similarly, cells containing only a “distal” cue also form prehairs close to the cell edge (Fig.1F). Hence, prehair formation in neighbouring cells is not necessary for cells with just a “proximal” or “distal” cue to position prehairs correctly, although cell-cell communication of another form is not excluded.

Additionally, we investigated the increased delay in prehair initiation in fz mutant cells versus stbm mutant cells. In theory, Fz and Stbm could be required simply to localise a prehair promoting cue and repressing cue respectively, or could also be required for the activity of the cue. Hence, cells mutant for both fz and stbm might contain neither cue, or could contain one or both cues uniformly distributed.

Interestingly, stbm clones in a uniformly fz mutant background, show no difference in the time of prehair initiation between single and double mutant tissue (Fig.1G). This is consistent with Stbm acting to modulate the distribution of a cue but not altering its overall activity, such that the cue is equally active in cells with and without Stbm. Conversely, fz clones in a stbm mutant background show prehairs initiating sooner in stbm mutant tissue than in stbm; fz double mutant tissue (Fig.1H). This suggests that Fz is able to promote prehair initiation positively, and that in the absence of Fz, this promoting activity is lost.

In sum, our results suggest prehair initiation is controlled by an inhibitory cue that is normally localised proximally in a Stbm-dependent manner, but is not strictly dependent upon Stbm for its activity, and a Fz-dependent cue which positively promotes prehair formation.

In, Fy and Frtz are putative effectors of the proximal prehair initiation cue

Loss of activity of in, fy or frtz results in more than one prehair initiating in ectopic positions in the cell, consistent with inappropriate activation of a prehair promoting cue or loss of a prehair repressing cue (Gubb and García-Bellido, 1982; Wong and Adler, 1993; Collier et al., 2005). Notably, In localises proximally with Stbm, in a Stbm-dependent manner (Adler et al., 2004), suggesting that In mediates the “proximal” cue. Proximal localisation of In also depends upon fy and frtz activity (Adler et al., 2004), consistent with these three gene products acting together to regulate prehair initiation.

We raised an antibody against Frtz, and find that Frtz also localises to proximal junctions (Fig.2A), and that this localisation depends upon in and fy activity (Fig.2B,C), but not the downstream acting gene mwh (Fig.2D). Frtz junctional localisation also requires stbm activity (Fig.2E), but is only reduced in pk mutants (Fig.2F), consistent with the effects of loss of pk on the distribution of Stbm (Bastock et al., 2003). Similarly, in fz mutant cells away from clone borders, significant junctional localisation is retained (Fig.2G). Fluorescent intensities of Frtz immunolabelling in the junctional regions of mutant tissue was quantitated. Interestingly, within in and fy tissue, levels were the same as within frtz tissue, indicating that junctional Frtz protein is undetectable. However, in fz tissue, fluorescent intensities were about 50% of wildtype levels, and in stbm tissue fluorescent intensities still showed 25% of wildtype levels. This suggests that whilst Frtz is not noticeably localised to junctions in stbm tissue, protein is nevertheless still present within the cell, supporting the contention that Stbm acts to localise Frtz activity but not necessarily to control its levels. (As our Frtz antibodies did not work for immunoblotting, we were unable to more directly assess protein levels.)

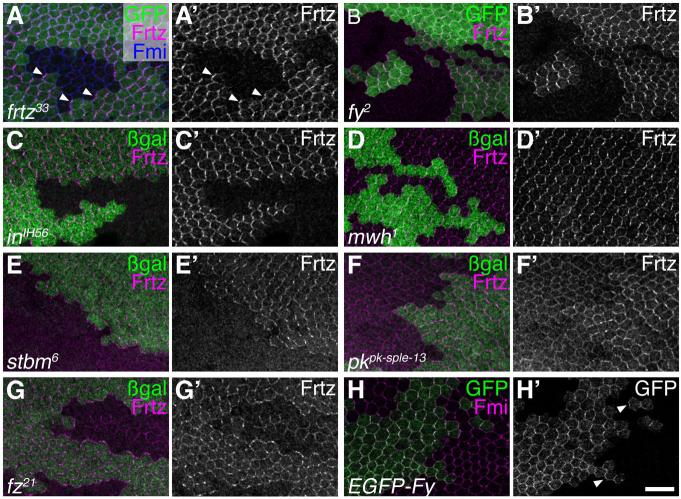

Figure 2. Frtz is proximally localised under control of polarity gene activity.

28 hour pupal wings immunolabelled for Frtz (A-G, magenta or white) and/or Fmi (A, blue; H, magenta), and clonal marker (lacZ or GFP, green) or EGFP-Fy (H, green or white). Arrowheads indicate proximally enriched localisation of protein. Scale bar in H’ represents 10μm.

(A) frtz33 clone.

(B) fy2 clone.

(C) inIH56 clone.

(D) mwh1 clone.

(E) stbm6 clone.

(F) pkpk-sple-13 clone.

(G) fz21 clone.

(H) Mosaic expression of EGFP-Fy induced from a P{w+, ActP-FRT-PolyA-FRT-EGFP-Fy} transgene using hsFLP expression.

These results indicate that Frtz, like In, localises proximally in a Stbm-dependent manner. We also attempted to determine the localisation of Fy, using an EGFP tagged form. We again saw preferential localisation to the apicolateral junctions, with enrichment at proximal cell edges (Fig.2H). These results are consistent with In, Fy and Frtz all colocalising proximally, and (at least in the case of In and Frtz) requiring the activity of the other two to become localised.

mwh encodes a novel FH3 domain protein which is more strongly localised proximally in cells

The mwh locus has been mapped genetically to the cytological position 61E-F. As the most downstream known effector of core polarity gene function, we hypothesised that mwh might encode a protein that interacts directly with the cytoskeleton. Searching by gene ontology in FlyBase for “cytoskeletal protein binding” revealed a single uncharacterised candidate gene CG13913 in this region. A strain carrying a transgene able to inducibly express an RNAi hairpin against the CG13913 transcript (Dietzl et al., 2007), closely phenocopied the mwh phenotype (Fig.3B). Importantly, transgenic flies expressing the CG13913 gene product fused to EGFP also show complete rescue of the mwh phenotype (Fig.3C). In addition, we isolated the predicted coding region of CG13913 from mwh1 flies by PCR, and determined that the locus has been subject to a rearrangement in which an inversion breaks the coding sequence after amino acid 367 (Fig.3D). Taken together, this is good evidence that mwh corresponds to CG13913, and also suggests that the mwh1 allele is likely to correspond to a null allele (see also Materials and Methods).

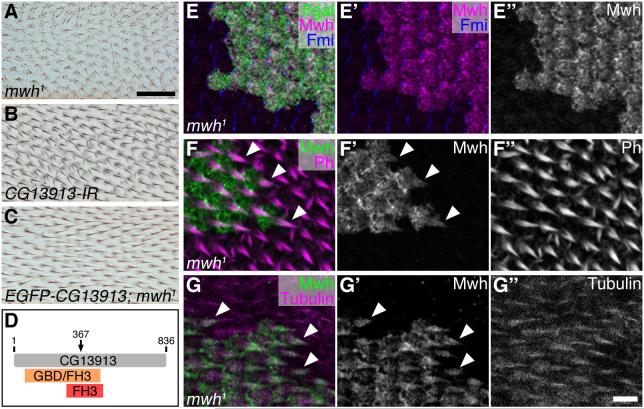

Figure 3. Mwh is an FH3 domain protein which localises proximally in cells.

Adult (A-C) or pupal wings (E-G). Scale bar in A represents 50μm, in G“ 10μm.

(A) mwh1 adult wing between veins 3 and 4, showing trichomes with characteristic multiple wing hair phenotype.

(B) Wing expressing CG13913-IR under control of ptc-GAL4 between veins 3 and 4 shows a multiple wing hair phenotype.

(C) mwh1 wing expressing EGFP-CG13913 from a P{w+, ActP-EGFP-CG13913} transgene shows rescue of the multiple wing hair phenotype.

(D) Diagram of the CG13913 coding sequence, showing the extent of the Interpro GBD/FH3 domain (IPR014768) and FH3 domain (IPR010472), and the point at which the inversion in mwh1 breaks the coding sequence (arrow).

(E) mwh1 clone in 32 hr wing, labelled for Mwh (magenta), clonal marker (lacZ, green) and Fmi (blue).

(F) mwh1 clone in 32.5 hr wing, labelled for Mwh (green) and actin (Ph, magenta), arrowheads indicate trichomes, in which Mwh does not colocalise strongly with actin bundles.

(G) mwh1 clone in 32.5 hr wing, labelled for Mwh (green) and α-tubulin (magenta), arrowheads indicate trichomes in which Mwh does not colocalise with tubulin.

Analysis of the CG13913 coding sequence for known protein domains (Labarga et al., 2007) revealed the presence of Interpro domains Diaphanous Formin Homology 3 (FH3) and GTPase-Binding/Formin Homology 3 (GBD/FH3) (Fig.3D). Formins are a class of proteins involved in actin nucleation, and generally consist of three conserved domains known as the FH1, FH2 and GTPase Binding Domain (GDB) (Wallar and Alberts, 2003). In addition, some formins also contain a further conserved domain known as the FH3 domain which partly overlaps the GTPase binding domain, and is thought to be involved in subcellular localisation of the protein (Petersen et al., 1998; Kato et al., 2001). Homology searches identify homologues of Mwh only in insects, with the closest mammalian matches to the GBD/FH3 domain being found in conventional Formins also containing an FH2 domain. However a GBD/FH3 domain is found in the absence of FH2 domains in some Dictyostelium RasGEFs (Rivero et al., 2005). Thus Mwh is a novel protein implicated in actin cytoskeleton regulation, but which lacks the functional domains normally found in Formins that mediate actin nucleation.

We raised an antibody against Mwh, and used it to determine the subcellular distribution of the protein. At around the time of prehair initiation, Mwh exhibits a punctate distribution in apical regions of the cell, which is stronger proximally and weaker distally (Fig.3E; S1A,B). Interestingly, unlike In, Fy and Frtz, Mwh shows no direct colocalisation with core polarity proteins in the junctional region, although it is present in a similar apical plane. Mwh is also seen at low uniform levels within growing prehairs, but does not strongly colocalise with either actin filaments or microtubules (Fig.3F,G).

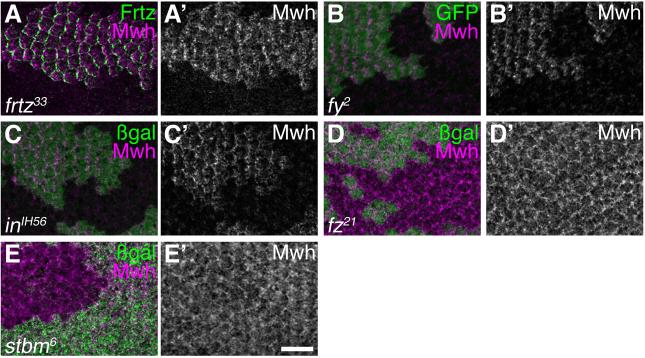

Mwh localisation and phosphorylation are regulated by frtz

Next we asked whether Mwh levels or distribution were regulated by in, fy and frtz. Interestingly, in all three genotypes, the apical punctate labelling of Mwh is dramatically reduced (Fig.4A-C). By contrast, in fz and stbm clones, the proximal enrichment of Mwh is lost (consistent with loss of proximal Frtz localisation), but the levels of apical punctate labelling are not greatly altered (Fig.4D,E; S1C-F).

Figure 4. Mwh localisation is regulated by in, fy and frtz.

32 hour pupal wings immunolabelled for Mwh (magenta or white), and clonal marker (frtz expression, GFP or lacZ, green). Scale bar in E’ represents 10μm.

(A) frtz33 clone.

(B) fy2 clone.

(C) inIH56 clone.

(D) fz21 clone.

(E) stbm6 clone.

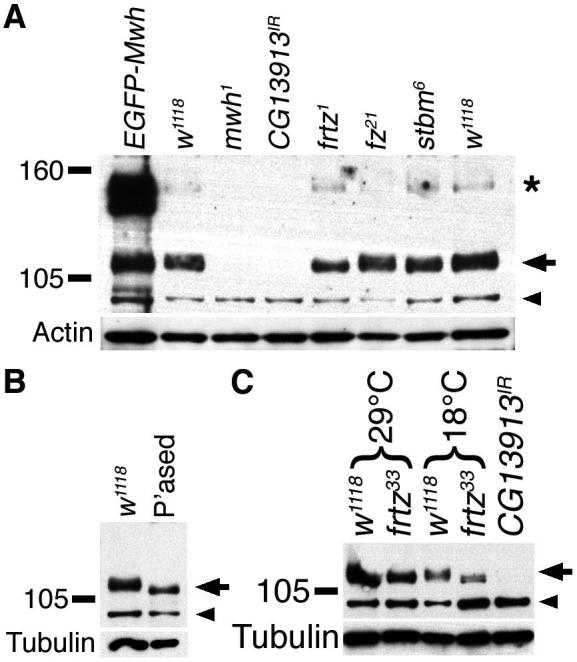

To investigate the effects of frtz on Mwh further, we used our antibody for immunoblotting. In extracts from wildtype flies, the antibody detects a number of bands in the molecular weight range expected for Mwh (∼91 kDa), however only a broad band migrating at about ∼110 kDa is lost in mwh or CG13913-RNAi extracts, consistent with this representing the Mwh protein (Fig.5A). Expression of EGFP-Mwh gives rise to bands ∼20-30 kDa larger, reflecting the expected shift in molecular weight after addition of the tag. Extracts from fz and stbm flies showed negligible change in Mwh levels, consistent with the immunolabelling results (Fig.5A). However, loss of frtz activity resulted in a slight increase in Mwh mobility with a loss of a higher molecular weight population (Fig.5A,C). We surmise that the higher molecular weight form constitutes the apical and proximally enriched punctate population of Mwh seen by immunolabelling, as both are reduced in frtz cells.

Figure 5. Mwh is mobility is modified by frtz activity and phosphorylation.

Immunoblots using anti-Mwh on extracts from pupal wings of the indicated genotypes, with w1118 as wildtype control. Positions of molecular weight markers shown on left, arrow on right indicates Mwh signal, arrowhead points to non-specific band that is not altered in mutant extracts. Some extracts also show a weak higher molecular weight band which appears to be specific (asterisk), but varies in intensity. Blots reprobed for actin or tubulin as loading controls.

(A) Extracts from 32 hour pupal wings at 25°C.

(B) Extracts from 32 hour pupal wings at 25°C, either treated with the phosphatase inhibitor microcystin (control, w1118) or with lambda phosphatase (“P’ased”).

(C) Extracts from 28 hour pupal wings raised at 29°C or 64 hour pupal wings raised at 18°C (both equivalent to 32 hours at 25°C).

A plausible explanation for the presence of the higher molecular weight form of Mwh, is that Frtz promotes post-translational modification of Mwh. When wildtype protein extracts were treated with phosphatase (Fig.5B), the slower migrating form of Mwh was lost and an increase in mobility similar to that seen upon loss of frtz was observed, consistent with Frtz promoting Mwh phosphorylation.

Interestingly, the frtz, in and fy null phenotypes increase in strength at lower temperatures (Adler et al., 1994; Collier et al., 2005). This could be explained if Mwh stability was temperature dependent. On immunoblots, we find a dramatic reduction in Mwh levels in wings from animals raised at 18°C, as compared to 29°C (Fig.5C). This was additive to the effects of frtz on Mwh mobility, consistent with the cold-sensitivity exhibited by in, fy and frtz being a result of reduced stability of Mwh.

mwh mutant cells shows ectopic actin bundles across their apical surface

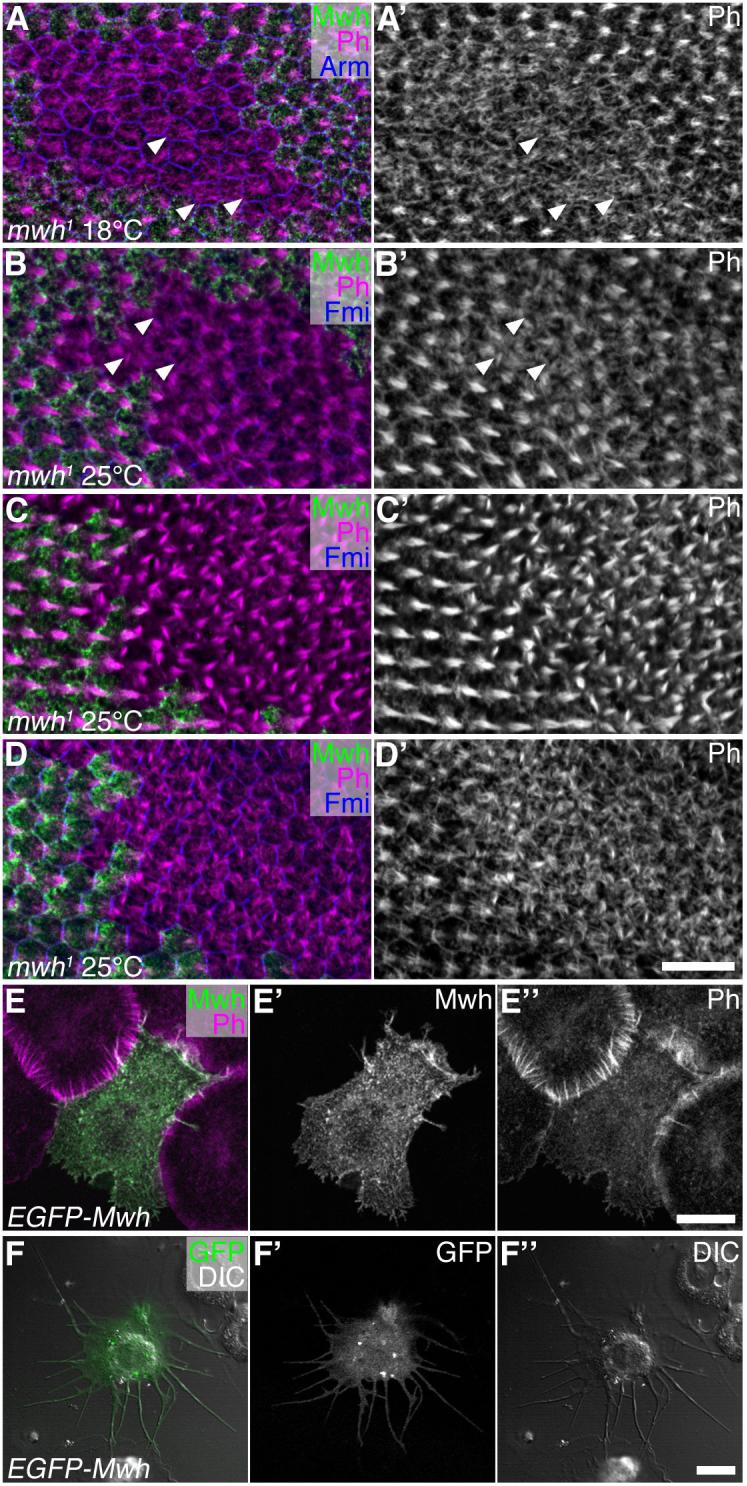

The earliest reported manifestation of the mwh phenotype is ectopic prehair initiation at the cell edge (Wong and Adler, 1993). Using fixation conditions optimised for preservation of F-actin structures, we re-examined the earliest stages of the mwh phenotype, looking in wings from animals raised at 18°C, 25°C and 29°C. A similar phenotype was seen at each temperature (Fig.6A-D, and not shown). We observed that prior to and during the appearance of prehair structures at the cell periphery, cells showed excess actin bundling across the apical surface of the cells, sometimes in a “starburst” pattern, with actin bundles radiating from the cell centre (Fig.6A,B). Subsequently, prehair structures are seen at cell edges as previously reported. Interesting, the excess actin bundles often extend at least 1 μm basally into the cytoplasm from the apical surface, particularly once prehair initiation is progressing (Fig.6C,D). These results suggest that excess actin polymerisation across the apical surface of the cell is the primary defect in mwh, and that ectopic prehairs forming at cell edges may be a secondary consequence.

Figure 6. Loss of mwh activity results in excess apical actin.

Pupal wings (A-D) immunolabelled for Mwh (green), actin (Ph, magenta or white) and Arm or Fmi (blue), or S2 cells transfected with EGFP-Mwh (E,F). Scale bars in D’, E” and F” represent 10μm.

(A) mwh1 clone in wing aged 65 hour at 18°C. Arrowheads indicate examples of cells with actin bundles radiating across entire apical surface, prior to formation of clear prehair structures.

(B) mwh1 clone in wing aged 32.25 hour at 25°C. Prehair formation more advanced than in wing shown in (A), but some cells still show actin bundles radiating across entire apical surface (arrowheads).

(C) mwh1 clone in wing aged 32.5 hour at 25°C. All mutant cells now showing multiple prehairs forming at cell periphery.

(D) Same clone as in (C), but sectioned ∼1 μm deeper, showing excess actin bundles below apical surface.

(E) S2 cell transfected with EGFP-Mwh (green), labelled for actin (Ph, magenta), and plated on Concanavalin-A for 1 hour, shows altered morphology with projections extending from cell edges and a loss of actin bundles at cell periphery.

(F) DIC image of an S2 cell transfected with EGFP-Mwh (green), and plated on Concanavalin-A for 24 hours, showing more extreme phenotype with long filopodia-like extensions around the cell periphery.

Mwh can affect actin structures in cultured cells

The molecular homology of Mwh suggests that it could directly interact with the cytoskeleton or cytoskeletal modulators via its GBD/FH3 domain. However the lack of other functional domains seen in formins might indicate that Mwh negatively influences actin filament formation, which would explain the unrestricted actin bundling seen across the apical surface of cells in its absence. To gather more evidence for Mwh repressing actin filament formation, we transfected Mwh into cultured Drosophila S2 cells and assayed the effect on their actin cytoskeleton and behaviour. Intriguingly, cells expressing high levels of EGFP-Mwh show an altered morphology relative to their contacting neighbours, characterised by a less rounded shape, the appearance of slender projections at the cell periphery and a reduction in F-actin bundles visible at the cell periphery (Fig.6E). When we quantitated the reduction in fluorescent-labelling intensity at the edges of transfected cells, we found on average a 63% reduction. Furthermore, we observed that isolated transfected cells progressively developed a more dramatically altered morphology with radially projecting slender extensions (Fig.6F, present in 84% of transfected cells, relative to only 6% of control cells). This phenotype is reminiscent of the effects of reducing the activity of a number of proteins involved in actin dynamics, including the Arp2/3 complex, which is required for nucleation of actin filaments (Kiger et al., 2003; Kunda et al., 2003). Together these results suggest that EGFP-Mwh overexpression can inhibit actin filament formation.

Discussion

The site of prehair initiation is influenced by both proximal and distal cellular cues

Activity of the core planar polarity proteins is required in cells of the Drosophila pupal wing to specify prehair initiation at the distal vertex (Wong and Adler, 1993). Here we present evidence that core polarity protein localisation at both proximal and distal cell edges provides redundant cues for specifying distal prehair initiation.

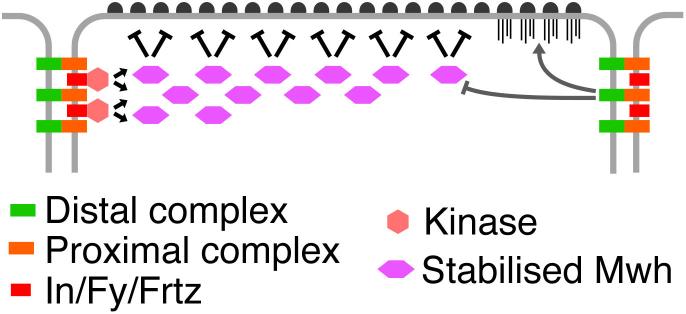

Regarding the mechanistic basis of the proximal cue, this and previous work provide evidence for a plausible model (Fig.7). The downstream effectors In, Fy and Frtz all colocalise at the proximal cell edge with Stbm and in a Stbm-dependent manner. Activity of In, Fy and Frtz is required for Mwh phosphorylation and its subapical subcellular localisation, which is thus concentrated towards the proximal side of the cell. Genetic studies have shown that loss of fy, in, frtz or mwh activity leads to excess prehair initiation (Wong and Adler, 1993; Collier et al., 2005), and we find that the initial defect in mwh is excess actin bundling across the entire apical face of cells. Thus, proximal restriction of Mwh activity in the cell results in actin bundling and prehair initiation specifically in distal regions.

Figure 7. Model for placement of prehair initiation.

Diagram represents a Z-section of apical regions of a cell, showing distal complexes (green) and proximal complexes (orange). Proximal complex recruits In, Fy and Frtz (red), which in turn recruit or activate an unknown kinase (pink) which modifies Mwh (magenta), which consequently is stabilised in apical/proximal regions. Mwh acts as an inhibitor of actin filament formation in electron dense pimples on surface of cells (dark grey), possibly by interfering with the activity of conventional formins. Distally in the cell, pimples become activated as a consequence of lack of Mwh activity. Distal complex promotes pimple activation, either via repression of Mwh activity or via an independent mechanism.

Additional evidence for the sufficiency of a Stbm-dependent cue for prehair initiation at opposite cell edges comes from experiments in the abdomen (Lawrence et al., 2004). Here it was reported that cells lacking fz activity, but juxtaposed to cells with fz activity, could produce polarised trichomes, as we also observe in the first row of cells within a fz clone in the wing.

We have less information regarding the distal cue. Its existence is based upon two pieces of evidence. First, if prehair initiation were entirely dependent on Stbm-mediated localisation of Mwh activity, then prehairs should show no bias in their site of initiation in cells lacking stbm activity. In fact, stbm mutant cells with Fz localised at one cell edge show a strong bias towards initiating prehairs at this edge. Second, if prehair initiation were controlled only by a Stbm-dependent repressive cue, then in the absence of stbm activity, Fz would have no influence over prehair initiation. Instead, in a stbm background, fz activity still weakly promotes prehair formation. Taken together these data support the view that distally localised Fz acts as a prehair promoting cue.

A possible mechanism of action of the distal cue would be if localised Fz was able to repress Mwh activity in distal cell regions, possibly via its known effectors RhoA and Drok (Strutt et al., 1997; Winter et al., 2001). Alternatively Fz could promote prehair initiation in a Mwh-independent fashion, either via RhoA/Drok or other effectors.

It is notable that absence of fz activity results in a delay in prehair formation, and a greater tendency for prehairs to form in the cell centre rather than towards a cell edge, than loss of stbm. We surmise that in fz mutant cells, there is no Fz-dependent prehair promoting cue, and the Stbm-dependent repressive cue is evenly distributed around the cell edge, resulting in delayed prehair initiation in the cell centre. Conversely, in stbm mutant cells, there is no change in the activity of the repressive cue, but the Fz-dependent prehair promoting cue is localised to cell edges, albeit more thinly spread than in the wildtype situation. This results in approximately normally timed prehair initiation near cell edges.

An unexplained observation is that within stbm mutant tissue, the site of prehair initiation appears to be biased towards that seen in neighbouring cells. Thus in the first rows of cells within a clone, prehairs tend to point towards the adjacent wildtype tissue. This phenomenon is presumably independent of core protein asymmetric localisation, and may depend upon some mechanical linkage between cells. In this context, there is already evidence that the microtubule cytoskeletons of adjacent cells may be linked and that this could coordinate cell polarity (Turner and Adler, 1998). An alternative core protein-independent mechanism to align wing hairs, relying on the activities of Gliotactin and Coracle has also been reported (Venema et al., 2004).

How is Mwh activity regulated?

Loss of in, fy, and frtz results in a similar phenotype to loss of mwh with multiple ectopic prehairs at the cell edge preceded by excess apical actin bundling (D.S. unpublished and Wong and Adler, 1993). As In, Fy and Frtz are all required for the apical punctate distribution of Mwh within cells, and also appear to stabilise each other (this work and Adler et al., 2004), this suggests that In, Fy and Frtz act together to activate Mwh and promote apical localisation. Conversely, while Stbm plays a rôle in localising Mwh within the cell, it is not required for its activity, as loss of stbm does not phenocopy mwh mutants in which increased apical actin bundling is observed. This rôle of Stbm in localising but not regulating Mwh activity is most simply explained by Stbm acting to localise, but not regulate In, Fy and Frtz activities. This is supported by the observation that whereas loss of fz or stbm has a strong effect on the distribution of Frtz to the apicolateral junctions, it has a negligible effect on the apparent phosphorylation state of Mwh.

The regulation of Mwh activity appears to be largely post-translational, as although the subcellular distribution of Mwh changes dramatically in frtz mutant cells, total levels of Mwh are not similarly altered. Further evidence that In, Fy and Frtz regulate Mwh activity by a mechanism largely independent of Mwh protein levels comes from the observation that Mwh overexpression in the wing produces no effect on trichome formation (D.S. unpublished), rather than repressing trichome formation as might be predicted if protein levels were the main determinant of activity.

Our data are strongly suggestive that Mwh activity may be regulated by phosphorylation. Treatment of cell extracts with phosphatase results in increased mobility of Mwh. A similar increase in mobility is observed when frtz activity is removed, but not when stbm or fz activities are removed. Thus, at the least, Mwh phosphorylation correlates with Mwh activity and apical punctate localisation. Hence we propose that the rôles of In, Fy and Frtz may be to activate, or bring into proximity with Mwh, a kinase or kinases responsible for activating Mwh. Similarly, Fz could locally promote the dephosphorylation of Mwh to induce prehair initiation, although any such effect would have to be small, as Mwh phosphorylation is not obviously altered in the absence of Fz.

Definitive proof that phosphorylation of Mwh is important for its activity would require the identification of particular phosphorylation sites which were required for specific molecular functions and/or identification of a kinase critically required for Mwh activity.

An alternative regulatory mechanism for Mwh, via analogy to Diaphanous family formins, would be via RhoA GTPase activity (Wallar and Alberts, 2003). The FH2 domain of such formins promotes actin nucleation, an activity which is autoinhibited by interaction with the GTPase binding domain (GBD). Upon interaction of the GBD with GTPase-bound Rho GTPases, this autoinhibition is released. Notably, genetic interaction data suggest that Fz/Dsh can activate RhoA activity (Strutt et al., 1997; Winter et al., 2001). This is consistent with a model whereby in the proximal cell Rho GTPase activity is low and Mwh inhibits prehair initiation, and in the distal cell activated RhoA alleviates the inhibitory activity of Mwh.

Notwithstanding our evidence for post-translational regulation of Mwh activity in the normal context of the pupal wing, in cultured cells we do see an effect of Mwh overexpression on the actin cytoskeleton. This seems likely to be due to the much higher levels of expression that can be achieved in transfected cells as opposed to cells in the living organism, and hence the result should be treated with caution, but may suggest that S2 cells express a factor able to constitutively activate Mwh.

Our results also indicate that Mwh levels are influenced by temperature, which provides a plausible explanation for why in, fy and frtz phenotypes are stronger at 18°C (Adler et al., 1994; Collier and Gubb, 1997; Collier et al., 2005). We suggest that loss of in, fy and frtz reduces Mwh activity, and lower temperatures additively reduce Mwh levels, resulting in lower overall Mwh activity.

What is the molecular function of Mwh?

As already noted, the FH3 domain of conventional formins is thought to be involved in targeting the protein to particular cellular sites, whereas the GBD domain is involved in inhibition of the actin nucleating function of the FH2 domain (Wallar and Alberts, 2003). A plausible model is that Mwh acts as a dominant negative by binding via its GBD domain to other FH2 domain containing formins that are involved in the nucleation of actin filaments and inhibiting their activity. Notably, this dominant negative activity of Mwh could then be inhibited distally in the cell by Fz-mediated activation of RhoA GTPase activity.

Electron microscopy studies suggest that prior to prehair initiation the apical cell surface is covered in electron-dense “pimples” that are normally only activated at the distal cell edge and serve as foci for actin filament formation (Guild et al., 2005). We propose that at around 32 hours of pupal development, cells receive a general signal for pimple activation which results in actin nucleation, and that Mwh activity is required to inhibit this activation away from the distal cell edge.

The lack of direct vertebrate homologues of Mwh may indicate that in insects the GBD/FH3 domain of a conventional formin has become separated from the rest of the molecule but retained its function in inhibiting formin-mediated actin nucleation. Nevertheless, it is plausible that the core polarity proteins would use similar regulatory mechanisms to promote local changes in cytoskeletal structure in vertebrate cells as seen in the Drosophila wing. Importantly, vertebrate homologues of both Fuzzy and Inturned have been shown to be involved in regulating apical actin assembly and thus specifying the orientation of cilia (Park et al., 2006). By analogy to our findings, we suggest that core polarity proteins in vertebrates are likely to localise Fuzzy/Inturned activity within cells, and regulate formin activity via phosphorylation and/or Rho GTPase activation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank Paul Adler, Simon Collier, David Gubb, Tanya Wolff, the Bloomington Stock Centre, the Drosophila Genomics Resource Centre, the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Centre and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for providing reagents, and the University of Sheffield Antibody Resource Centre for assistance with antibody preparation. The project was initiated by Rebecca Bastock and helpful comments on the manuscript were provided by Phil Ingham, Helen Strutt, Steve Winder and Martin Zeidler.

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship to D.S. and the MRC. Confocal facilities were provided by the Wellcome Trust, MRC and Yorkshire Cancer Research.

References

- Adler PN, Charlton J, Park WJ. The Drosophila tissue polarity gene inturned functions prior to wing hair morphogenesis in the regulation of hair polarity and number. Genetics. 1994;137:829–836. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.3.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler PN, Zhu C, Stone D. Inturned localizes to the proximal side of wing cells under the instruction of upstream planar polarity proteins. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:2046–2051. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod JD. Unipolar membrane association of Dishevelled mediates Frizzled planar cell polarity signalling. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1182–1187. doi: 10.1101/gad.890501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastock R, Strutt H, Strutt D. Strabismus is asymmetrically localised and binds to Prickle and Dishevelled during Drosophila planar polarity patterning. Development. 2003;130:3007–3014. doi: 10.1242/dev.00526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier S, Gubb D. Drosophila tissue polarity requires the cell-autonomous activity of the fuzzy gene, which encodes a novel transmembrane protein. Development. 1997;124:4029–4037. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.4029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier S, Lee H, Burgess R, Adler P. The WD40 repeat protein fritz links cytoskeletal planar polarity to frizzled subcellular localization in the Drosophila epidermis. Genetics. 2005;169:2035–2045. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das G, Jenny A, Klein TJ, Eaton S, Mlodzik M. Diego interacts with Prickle and Strabismus/Van Gogh to localize planar cell polarity complexes. Development. 2004;131:4467–4476. doi: 10.1242/dev.01317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su KC, Barinova Y, Fellner M, Gasser B, Kinsey K, Oppel S, Scheiblauer S, et al. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;448:151–156. doi: 10.1038/nature05954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton S, Wepf R, Simons K. Roles for Rac1 and Cdc42 in planar polarisation and hair outgrowths in the wing of Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:1277–1289. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery G, Hutterer A, Berdnik D, Mayer B, Wirtz-Peitz F, Gaitan MG, Knoblich JA. Asymmetric Rab 11 endosomes regulate delta recycling and specify cell fate in the Drosophila nervous system. Cell. 2005;122:763–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubb D, García-Bellido A. A genetic analysis of the determination of cuticular polarity during development in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1982;68:37–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guild GM, Connelly PS, Ruggiero L, Vranich KA, Tilney LG. Actin filament bundles in Drosophila wing hairs: hairs and bristles use different strategies for assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:3620–3631. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Watanabe N, Morishima Y, Fujita A, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S. Localization of a mammalian homolog of diaphanous, mDia1, to the mitotic spindle in HeLa cells. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:775–784. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger AA, Baum B, Jones S, Jones MR, Coulson A, Echeverri C, Perrimon N. A functional genomic analysis of cell morphology using RNA interference. J. Biol. 2003;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein TJ, Mlodzik M. PLANAR CELL POLARIZATION: An Emerging Model Points in the Right Direction. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005;21:155–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.132806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunda P, Craig G, Dominguez V, Baum B. Abi, Sra1, and Kette control the stability and localization of SCAR/WAVE to regulate the formation of actin-based protrusions. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1867–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarga A, Valentin F, Anderson M, Lopez R. Web services at the European bioinformatics institute. Nucl. Acids Res. 2007;35:W6–W11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA, Casal J, Struhl G. Cell interactions and planar polarity in the abdominal epidermis of Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:4651–4664. doi: 10.1242/dev.01351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Adler PN. The function of the frizzled pathway in the Drosophila wing is dependent on inturned and fuzzy. Genetics. 2002;160:1535–1547. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.4.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell HK, Roach J, Petersen NS. The morphogenesis of cell hairs on Drosophila wings. Dev. Biol. 1983;95:387–398. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park TJ, Haigo SL, Wallingford JB. Ciliogenesis defects in embryos lacking inturned or fuzzy function are associated with failure of planar cell polarity and Hedgehog signaling. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:303–311. doi: 10.1038/ng1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park WJ, Liu J, Sharp EJ, Adler PN. The Drosophila tissue polarity gene inturned acts cell autonomously and encodes a novel protein. Development. 1996;122:961–969. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen J, Nielsen O, Egel R, Hagan IM. FH3, a domain found in formins, targets the fission yeast formin Fus1 to the projection tip during conjugation. J. Cell Biol. 1998;141:1217–1228. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren N, He B, Stone D, Kirakodu S, Adler PN. The shavenoid gene of Drosophila encodes a novel actin cytoskeleton interacting protein that promotes wing hair morphogenesis. Genetics. 2006;172:1643–1653. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.051433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivero F, Muramoto T, Meyer AK, Urushihara H, Uyeda TQ, Kitayama C. A comparative sequence analysis reveals a common GBD/FH3-FH1-FH2-DAD architecture in formins from Dictyostelium, fungi and metazoa. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada Y, Usui T, Yanagawa S, Takeichi M, Uemura T. Asymmetric colocalisation of Flamingo, a seven-pass transmembrane cadherin, and Dishevelled in planar cell polarisation. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:859–863. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt D. Frizzled signalling and cell polarisation in Drosophila and vertebrates. Development. 2003;130:4501–4513. doi: 10.1242/dev.00695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt D, Strutt H. Differential activities of the core planar polarity proteins during Drosophila wing patterning. Dev. Biol. 2007;302:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt DI. Asymmetric localisation of Frizzled and the establishment of cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:367–375. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt DI, Weber U, Mlodzik M. The rôle of RhoA in tissue polarity and Frizzled signalling. Nature. 1997;387:292–295. doi: 10.1038/387292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt H, Price MA, Strutt D. Planar polarity is positively regulated by casein kinase Iε in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1329–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tree DRP, Shulman JM, Rousset R, Scott MP, Gubb D, Axelrod JD. Prickle mediates feedback amplification to generate asymmetric planar cell polarity signalling. Cell. 2002;109:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CM, Adler PN. Distinct roles for the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons in the morphogenesis of epidermal hairs during wing development in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 1998;70:181–192. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T, Shima Y, Shimada Y, Hirano S, Burgess RW, Schwarz TL, Takeichi M, Uemura T. Flamingo, a seven-pass transmembrane cadherin, regulates planar cell polarity under the control of Frizzled. Cell. 1999;98:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venema DR, Zeev-Ben-Mordehai T, Auld VJ. Transient apical polarization of Gliotactin and Coracle is required for parallel alignment of wing hairs in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2004;275:301–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson CR, Adler PN. Directional non-cell autonomy and the transmission of polarity information by the frizzled gene of Drosophila. Nature. 1987;329:549–551. doi: 10.1038/329549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallar BJ, Alberts AS. The formins: active scaffolds that remodel the cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:435–446. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Nathans J. Tissue/planar cell polarity in vertebrates: new insights and new questions. Development. 2007;134:647–658. doi: 10.1242/dev.02772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter CG, Wang B, Ballew A, Royou A, Karess R, Axelrod JD, Luo L. Drosophila Rho-associated kinase (Drok) links Frizzled-mediated planar polarity signalling to the actin cytoskeleton. Cell. 2001;105:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong LL, Adler PN. Tissue polarity genes of Drosophila regulate the subcellular location for prehair initiation in pupal wing cells. J. Cell Biol. 1993;123:209–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Rubin GM. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–1237. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.