Abstract

We describe three theoretical accounts of age-related increases in falsely remembering that imagined actions were performed (Thomas & Bulevich, 2006). To investigate these accounts and further explore age-related changes in reality monitoring of action memories, we used a new paradigm in which actions were (a) imagined-only (b) actually performed, or (c) both imagined and performed. Older adults were more likely than younger adults to misremember the source of imagined-only actions, with older adults’ more often specifying that the action was imagined and also that it was performed. For both age groups, as repetitions of the imagined-only events increased, illusions that the actions were only performed decreased. These patterns suggest that both older and younger adults utilize qualitative characteristics when making reality-monitoring judgments and that repeated imagination produces richer records of both sensory details and cognitive operations. However, sensory information derived from imagination appears to be more similar to that derived from performance for older than younger adults.

Keywords: aging, imagination inflation, memory, reality monitoring

Everyday life is a jumble of imagined and performed actions. There are actions we imagine doing but never get around to performing, like sending an overdue email; actions we actually do perform without necessarily imagining, like locking our office door when we step out; and still other actions we both imagine and perform, as when we imagine taking a daily medication while standing in the shower and then take it when we get out. Contributing to the jumble is the fact that actions may be imagined and/or performed only once or multiple times. The ability to correctly identify the origin of action memories is of obvious importance. To avoid believing we did things we did not do, imagined-only actions must not be identified as performed, and to avoid repeating ourselves, performed actions must be remembered as actually done, and not merely imagined. For older adults especially, meeting these memory challenges may be critically important. For instance, older adults frequently take multiple medications (e.g., Morell, Park, Kidder, & Martin, 1997), therefore correctly identifying the origin of memories concerning one's medication schedule is crucial for avoiding self-medication errors.

Attributing action memories to imagination or performance is a type of reality monitoring (Johnson & Raye, 1981). Though reality monitoring of action memories has been the subject of numerous past investigations (e.g., Anderson, 1984; Foley & Johnson, 1985; Goff & Roediger, 1998; Thomas, Bulevich, & Loftus, 2003), little is known about how and why reality monitoring for memories of discrete actions (as opposed to more complex events; see Hashtroudi, Johnson, & Chrosniak, 1990) might differ in older versus younger adults. Here we are interested specifically in people's ability to distinguish between one's own prior acts of imagination versus performance (see Cohen & Faulkner, 1989, Experiment 1, and Kausler, Lichty, & Freund, 1985, for younger versus older adult source memory for self- versus other-performed actions). Foley and Johnson (1985) examined this ability in children versus adults, but there has been only one published investigation of age-related differences in adulthood.

In that study, Thomas and Bulevich (2006) compared younger and older adults in a procedure in which participants engaged in three separate experimental sessions (following Goff & Roediger, 1998). In Session 1, participants imagined some actions and performed others one time each. In Session 2, conducted 24 hours after Session 1, participants imagined each of the actions from Session 1 zero, one, or five times. Also in Session 2, additional actions that were not presented in Session 1 were imagined zero, one, or five times. Finally, in Session 3, participants viewed a list of all the actions presented in the first two sessions plus new actions. Participants judged whether each action was presented in Session 1 specifically and, if so, whether it was imagined or performed in that session. Participants were instructed to ignore how the action was presented in Session 2, if applicable.

Replicating past research employing similar methods (e.g., Goff & Roediger, 1998; Thomas et al., 2003), Thomas and Bulevich (2006) found that the more times actions were imagined in Session 2, the more likely they were to be attributed to performance in Session 1 (the imagination inflation effect). This held regardless of age and whether the action actually had been imagined, performed, or not presented in Session 1. The key novel age difference was that older participants were more likely than younger to misremember imagined-only actions from either of the first two sessions as performed in Session 1 (at least when older and younger participants were tested at the same retention interval). In other words, older participants exhibited a reality-monitoring deficit for imagined actions.

Why are older adults more likely than younger to misremember imagined actions as performed? In this article we couch several possible theoretical explanations for the age-related reality-monitoring deficit. Following presentation of the theoretical explanations, we describe a new experimental paradigm that builds on the Thomas and Bulevich (2006) work and provides leverage on adjudicating among these possibilities.

Theoretical Explanations

One interpretation of Thomas and Bulevich's (2006) finding that reality-monitoring errors increased with number of imaginings, and were especially prevalent for older adults, is that participants—especially older ones—sometimes based their judgments on general trace information, such as overall strength or familiarity. This idea is in line with a popular account of imagination inflation effects (Garry, Manning, Loftus, & Sherman, 1996; Goff & Roediger, 1998; Thomas, Bulevich, & Loftus, 2003; Thomas & Loftus, 2002): “Imagining the action statements five times may greatly increase participants’ familiarity with the statement and its action, leading them to make a did response because they misinterpreted the strong familiarity of the statement as indicating that they had actually performed the action” (Goff & Roediger, p. 28). Expanding on this idea, participants—especially older ones—would in general be expected to attribute more familiar statements to the source that they experience as producing the greatest familiarity (or strength).

In Thomas and Bulevich (2006), performance produced stronger, or more familiar, item memory than did imagination as evidenced by better old/new recognition for performed than imagined actions (the enactment effect; see Engelkamp, 1998). Hence, participants and especially the older adults may have attributed generally stronger, more familiar memories to performance and weaker memories to imagination1. As just noted (Goff & Roediger, 1998), it follows that attributions to performance would thus increase with repeated imagining (for purposes of exposition we label this possibility the general strength heuristic).

Two alternative accounts can be derived from the source-monitoring framework (Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993), which assumes that memories are attributed to sources (e.g., imagination, performance) based largely on the degree of match between the quantity and quality of information retrieved and the expected informational characteristics of memories from different sources. The prominent qualitative characteristics of interest here are sensory detail (visual, auditory, tactile) and information about cognitive operations involved in generating mental images (e.g., retrieving information, judging the quality of an image). Because memories of imagined and performed events generally do differ in terms of sensory detail and cognitive operations (e.g., Brewer, 1988; Hashtroudi et al., 1990; McGinnis & Roberts, 1996; Suengas & Johnson, 1988), attributions based on these qualitative characteristics can be relatively accurate. However, as outlined below, misattributions can occur for various reasons.

One idea is that older adults more often misattribute imagined actions to performance because they more often base their judgments specifically on sensory details, and underutilize cognitive operations (see Thomas et al., 2003, for evidence that younger adults’ reality-monitoring judgments are sensitive to amount of sensory detail). Both imagination and performance produce a memorial record of sensory details (Johnson et al., 1993), but one way to distinguish between the two is that memories of imagination typically include a richer record of cognitive operations related to the generation of those details. It may be that older adults are less likely to evaluate cognitive operations when making reality-monitoring judgments than are younger adults (see Thomas & Bulevich, 2006, Experiment 2, for supporting evidence) and therefore more often misattribute imagined actions to performance on the basis of recollecting sensory details.

To the extent that even younger adults sometimes fail to evaluate cognitive operations, this hypothesis (which we term underutilization of cognitive operations) can also explain why Thomas and Bulevich (2006) found that five imaginings versus one led to more false “performed” responses for both age groups. The idea is that repeated imagination increases the amount of sensory detail in memories and greater amounts are more indicative of performance than imagination (e.g., Brewer, 1988; Hashtroudi et al., 1990; McGinnis & Roberts, 1996; Suengas & Johnson, 1988). Repeated imagination also enriches the record of cognitive operations, but again that matters only if participants utilize those operations.

A final hypothesis is based on the possibility that Thomas and Bulevich's (2006) paradigm may have overestimated the extent of any underutilization of cognitive operations. That is, source responses in this paradigm may not reveal all the source information participants actually evaluate. Consider that participants are required to report only how actions occurred in Session 1. Participants do not report whether they remember imagining actions in Session 2. Hence, it is possible that with more numerous imaginings, participants are simultaneously more likely to believe that they performed the actions in Session 1 and that they also imagined the actions in Session 2. To elaborate, memories of imagined actions may have qualitative characteristics indicative of both imagination and performance, and participants may take this to mean that actions were performed in Session 1 and imagined in Session 2 (as some actions in this paradigm actually were). By this account, participants fully utilize qualitative characteristics when making reality-monitoring judgments, but false “performed” responses nevertheless occur and increase with repeated imagination because performance is indicated by elements of those characteristics. In actuality, the participants may believe the actions were both imagined at one point and performed at another (we label this account dual attributions).

This dual-attributions account raises the possibility that age-related reality-monitoring deficits may be explained, at least in part, by age differences in the tendency to make dual attributions on the basis of a complete evaluation of qualitative characteristics. Specifically, one could hypothesize that, in late versus young adulthood, memories of imagined actions are qualitatively more confusable with memories arising from both imagination and performance. This could be the case if, with age, the sensory detail derived from performance becomes more similar to that derived from imagination. The idea here is that in young adulthood, sensory information derived from actual interaction with the rich, multisensory world tends to be more vivid than self-generated sensory information. However in late adulthood, there are declines in the operation of sensory-perceptual systems (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997; Verillo, 1993) and the process by which multiple features of events are bound together in memory (Chalfonte & Johnson, 1996; Naveh-Benjamin, 2000). These declines presumably reduce the amount of sensory detail in memories of performed actions. If older adults consequently come to expect less sensory detail in their memories of performed actions, then when they evaluate the qualitative characteristics of memories of imagined actions, they may be more likely to accept the limited sensory information they generated as evidence of performance (while simultaneously accepting cognitive operations as evidence of imagination).

In sum, at least three theoretical accounts of an age-related reality-monitoring deficit for imagined actions seem possible. These accounts explain the age difference in the incidence of false “performed” responses observed in Thomas and Bulevich (2006). However, previous studies examining reality-monitoring failures that have considered accounts based on familiarity/strength versus qualitative characteristics have been unable to empirically distinguish them (Goff & Roediger, 1998; Thomas & Loftus, 2002).

The Present Study

To help distinguish among the above accounts and to further investigate age-related changes in reality monitoring, we used a novel paradigm in this study. In our procedure, participants imagined performing some actions, performed others, and both imagined and performed still others in a single initial session. Some actions were imagined and/or performed once and some multiple times. In a second session conducted two weeks later, participants indicated, on separate numeric scales, how often they had imagined and how often they had performed actions in the first session. By assessing independently whether participants remember imagining actions and whether they remember performing them, this procedure allows for a more complete investigation of the bases for younger and older adults’ reality-monitoring attributions.

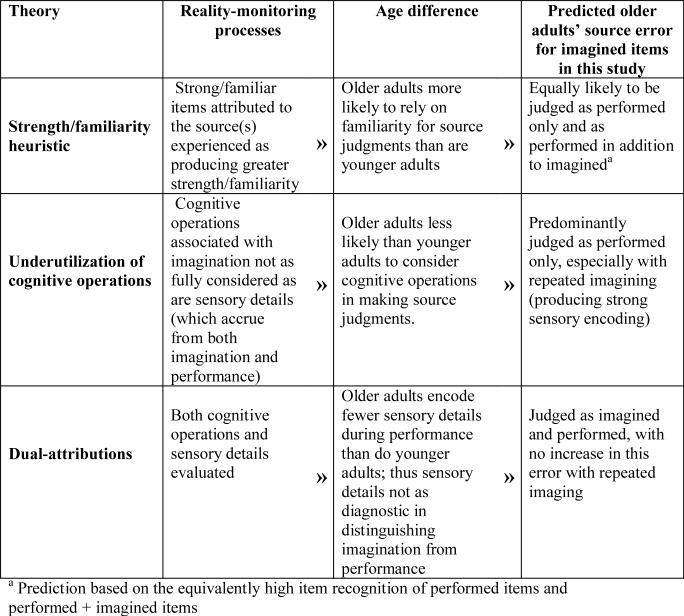

A key feature of the present procedure is that it reveals whether actions that were only imagined are misremembered as performed only or are as both imagined and performed. The three above accounts of the age-related reality-monitoring deficit make different predictions about the patterns of age-related differences in reality-monitoring and how repetition of imagination should affect the age-related differences. Figure 1 presents a summary of the accounts and their predictions for source errors for imagined items in the present experiment; following we briefly highlight the critical theoretical underpinnings of these predictions.

Figure 1.

Summary of the theoretical viewpoints, their assumptions regarding the locus of age-related differences in reality monitoring and associated predictions of expected age-related patterns in source errors for imagined items.

The general strength heuristic account predicts that repetition of imagination should increase misattributions of imagined-only actions to the source that produces the strongest item memory (as inferred from old/new recognition rates), and older adults should make more of these misattributions than younger adults (because older adults rely more on trace strength for source attributions). In the present experiment, both items that were only performed and items that were imagined and performed produced robust item memory. Consequently in the present context a strength/familiarity heuristic predicts that older adults should show approximately equivalent distribution of misattributions to both sources, and these misattributions should increase with repeated imagination.

The underutilization of cognitive operations account predicts that older adults should be more likely than younger adults to misattribute imagined-only actions as having only been performed, but no more likely (or even less likely) to misattribute them to having been performed in addition to having been imagined, because older adults will not realize that the actions were in fact imagined. Further, if underutilization of cognitive operations persists regardless of how often actions are imagined, then these performed-only errors should increase with repeated imagination (because repeated imagination will enrich the sensory detail in memories and make them more “performance-like”). Most important for current purposes, older adults especially should show this increase in performed-only errors with repetition of imagination (a pattern that would parallel Thomas & Bulevich, 2006). Note also that for actions that actually are both imagined and performed, older adults should more often fail to remember that they were imagined and therefore mistakenly believe these actions were only performed.

By contrast, the dual attributions account predicts that older adults should more often attribute imagined-only actions to having been performed in addition to imagined compared to younger adults, but older adults should be fairly comparable to younger adults in attributing these items to only having been performed. The proportion of imagined items attributed to imagination that are also attributed to performance may be greater for older than younger adults but importantly from this perspective the pattern may be static across repetitions of imagination. The idea here is that repeated imagination may simultaneously increase the number of actions that are correctly remembered as imagined (because the record of cognitive operations is presumably being augmented) and the number that are falsely remembered as also performed (because sensory detail is accruing as well).

A final aspect of this experiment warrants mention. Past studies have shown that increasing the number of times actions are imagined increases the likelihood they will be falsely remembered as performed (Goff & Roediger, 1998; Thomas & Bulevich, 2006; Thomas et al., 2003), but these studies have not addressed the question of how many times participants remember performing the actions, when they did not perform them even once. Indeed, to our knowledge, all past studies of false memory and aging have focused exclusively on false memories for single instances of events (see Roediger & McDaniel, 2007, for a review). Johnson and colleagues (Johnson, Raye, Wang, & Taylor, 1979; Johnson, Taylor, & Raye, 1977; Raye, Johnson, & Taylor, 1980) conducted a series of studies investigating the influence of imagination on the perceived frequency of real external events but they were not concerned with false memories of events that did not happen at all or with age-related differences. In the present experiment, participants indicated the number of times they remembered imagining and/or performing actions, allowing us to examine whether frequency estimates of illusory performance increase with the number of times actions are imagined.

Method

Participants

Participants were 17 younger adults (15 females) between 18 and 31 years of age (M = 19.0 years) and 34 older adults (23 females) between 65 and 87 years of age (M = 76.3 years). Younger adults had fewer years of education (M = 13.7 years) and lower scores on the Shipley Vocabulary Test (M = 26.5; Shipley, 1940) than older adults (M = 16.7 years of education, t (49) = −4.80, p < .001, and M = 36.3 on Shipley, t (47) = −7.20, p < .001). Participants in this study were the same as those in Butler, McDaniel, Dornburg, Price, and Roediger (2004). One younger and one older adult were not included in these analyses because of false alarms to new items greater than 50% and one older adult was excluded for complete failure to discriminate whether actions were performed or imagined.

Materials

A set of 72 action statements was created for which most of the actions involved a single object, the action was typical for that object, and the objects were small and familiar (e.g., “roll the car across the table”). The actions and objects were chosen to be dissimilar from one another (see Appendix). This set was divided into four subsets three were presented at study and one was used as new statements in the test phase. The study subsets were assigned to three different conditions: performed-only, imagined-only, and imagined+performed. Within each condition, action statements furthermore were equally divided among different levels of frequency. Performed-only and imagined-only actions were performed or imagined one, two, or four times. Imagined+performed actions were either imagined once and performed once or imagined twice and performed twice. Across participants the particular subsets were counterbalanced across the study and frequency conditions.

Action statements were presented in a random order during study. When an action was presented more than once, the presentations were randomly distributed throughout the sequence, rather than following one after the other. For imagined+performed actions, the order of imagination and performance trials was randomly determined.

Participants were tested with all 72 action statements read aloud by the experimenter. The test statements were presented in alphabetical order for younger adults and a random order for older adults due to an experimenter error. Examination of both orders, however, indicated that neither contained systematic groupings of actions from a particular encoding condition. The test form provided two scales for each statement, one labeled “Did” and the other labeled “Imagined”. Both scales ranged from 0 to 8.

Procedure

The experiment was divided into two sessions. In the first session, participants were told that the experimenter would be reading a list of action statements and that their memory for the statements would be tested during the second session. They were not told what type of test would be given. Participants were shown the objects referenced in the statements and instructed to do or imagine the specified action (e.g., “Do. Break the toothpick,” or “Imagine. Break the toothpick.”). When given the “do” instruction, participants were told to perform the stated action to the best of their ability. When given the “imagine” instruction, they were told to imagine performing the action in as much detail as possible. Specifically, participants were told to imagine the feel of the object in their hands, the movements they would make, the type and volume of sound the object might produce, and the visual details of the object they would see when performing the action. Trials lasted 15 seconds and participants were instructed to continue performing or imagining the action for the entire 15 seconds. Objects remained in view until the end of the trial. At the end of each imagination trial, participants rated the clarity of the image they created on a scale from 0 (completely unclear) to 7 (completely clear).

Following the study procedure participants were given a break. Then they completed a 5-min vocabulary test followed by an unrelated memory task in which participants studied associated word lists and were tested on them. Results from the unrelated memory task are reported in Butler et al. (2004).Two weeks later, participants returned for a memory test on the action statements. The entire set of statements (old and new) was presented one-at-a-time and participants indicated how many times (from 0 to 8) they performed and imagined each action on separate scales labeled “Did” and “Imagined”. Participants were told that some of the actions would be new, some had been performed only, some had been imagined only and some had been both performed and imagined.

Results

The alpha level for significance was .05 for all analyses.

Item Memory

We first analyzed old/new recognition. An action was judged old if participants gave any non-zero response on at least one of the scales (for this analysis, we ignored whether the correct scale or scales were endorsed). Table 1 shows the mean proportion of actions correctly judged old (i.e., hits). To compare recognition of imagined-only and performed-only items to imagined+performed items, it was necessary to ignore items imagined or performed only once. We analyzed hits with a 2 (age: younger or older) X 2 (frequency: 2x or 4x) X 3 (source: imagined-only, performed-only, or imagined+performed) mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA), in which age was between-participants and frequency and source were within-participant variables. There were main effects of all three factors. Item memory was greater for younger (M = .96) than older (M = .85) participants, F(1, 49) = 15.66, MSe = .05, p < .001, and recognition increased with frequency of presentation (M's for 2x and 4x = .86 and .95, respectively), F(1, 49) = 22.12, MSe = .02, p < .001. Note that the effect of frequency was mediated by age, F(1, 49) = 4.89, MSe = .12, p = .03, in that the increase in hits was larger for older (M = .13) than younger (M = .05) participants, but this is likely due to the fact that younger participants were already near ceiling for actions presented twice (M = .93), while older participants were not (M = .79).

Table 1.

Mean hit rates (with standard errors) as a function of source, frequency, and age.

| Frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Age | 1x | 2x | 4x |

| Imagined-Only | ||||

| Younger | .56 (.06) | .91 (.03) | .99 (.01) | |

| Older | .46 (.05) | .73 (.04) | .87 (.03) | |

| Performed-Only | ||||

| Younger | .75 (.06) | .95 (.02) | .99 (.01) | |

| Older | .60 (.04) | .82 (.03) | .96 (.01) | |

| Imagined+Performed | ||||

| Younger | — | .94 (.02) | .96 (.02) | |

| Older | — | .82 (.03) | .93 (.02) | |

Finally, and most important, item memory varied by source, F(2, 98) = 6.87, MSe = .01, p = .002, but the main effect was qualified by an interaction with age, F(2, 98) = 3.97, MSe = .01, p = .02. As seen in Table 1, for younger participants item memory was about the same and near ceiling regardless of source. However, for older participants hits for imagined-only items (M = .80) were significantly lower than for performed-only items (M = .89), t(33) = 4.55, p < .001, and imagined+performed items (M = .87), t(33) = 3.65, p = .001. Hits for performed-only and imagined+performed items did not differ, t(33) = 1.01, p = .32.

In sum, memory strength increased with frequency of presentation and, at least for older adults, actions that were performed-only or imagined+performed were more likely to be recognized than those that were imagined-only. Further evidence for these effects came from an analysis of hits for actions imagined-only or performed-only once versus twice. A 2 (age) X 2 (frequency: 1x or 2x) X 2 (source: imagined-only or performed-only) ANOVA revealed main effects of frequency, F(1, 49) = 69.80, MSe = .04, p < .001, and source, F(1, 49) = 18.69, MSe = .03, p < .001. Hits were greater for actions imagined-only or performed-only twice (M = .85) versus once (M = .59) and were greater for performed-only actions (M = .78) than imagined-only ones (M = .67). Although the memory advantage for performed-only actions held regardless of frequency, it was substantially smaller when actions were presented twice (M = .06) versus once (M = .17) and this resulted in a significant interaction of frequency and source, F(1, 49) = 5.62, MSe = .02, p = .02.

We also tested whether younger and older participants differed in the proportion of new actions erroneously identified as old (i.e., false alarms). An independent-samples t-test indicated no significant difference (M = .07 for younger participants and .11 for older participants; t(49) = 1.12, p = .27).

Recognition and Reality Monitoring

Compared to younger participants, older participants had significantly fewer hits but not significantly more false alarms. This suggests that, although older participants remembered fewer of the actions, they did not simply guess that actions were old in an attempt to compensate for their lack of memory; if they had, their false alarm rate would have been higher than that of younger participants. Thus, we can assume that reality-monitoring judgments for old actions were based on genuine item memory for those actions to the same extent for younger and older participants. However, because older participants had fewer hits than younger participants, we analyzed reality-monitoring judgments conditional on recognition2.

Reality Monitoring of Imagined-Only Actions

We first calculated for each participant the proportion of imagined-only actions given any non-zero response on the imagined scale. These responses constitute source identifications that are at least partially correct because they indicate that participants thought they had imagined the actions at least once. The proportions were entered into a 2 (age) X 3 (frequency) ANOVA. There was no main effect of age, F(1, 45) = 1.37, MSe = .13, p = .25, and no interaction between age and frequency, F < 1. The mean proportion of imagined source identifications was comparable for younger (M = .83) and older adults (M = .76). However, imagined source identifications did vary as a function of frequency, F(2, 90) = 10.52, MSe = .04, p < .001. Actions that were imagined more often were more likely to be judged imagined (M's for 1x, 2x, and 4x = .68, .83, and .87, respectively). The complement of this analysis is that of imagined-only actions given a zero response on the imagined scale (and a non-zero response on the did scale). Participants failed to remember imagining these actions at all and instead thought they had only performed them. Of theoretical importance is that such performed-only errors were not significantly more common for older (M = .24) than younger adults (M = .17) and they decreased with repeated imagining (M's for 1x, 2x, and 4x = .32, .17, and .13, respectively).

Older adults were not significantly less likely than younger adults to remember that imagined-only actions had, in fact, been imagined, but it is possible they were less able to keep track of the exact number of times the actions had been imagined. To test for age-related differences in imagination-frequency judgments, we calculated for each participant the mean non-zero imagined response given to imagined-only actions at each level of frequency (only participants who gave at least one non-zero imagined response at all levels of frequency were included in this analysis). The means were submitted to a 2 (age) X 3 (frequency) ANOVA. There was a main effect of frequency, F(2, 80) = 4.54, MSe = .36, p < .001, such that estimates increased with number of imaginings (see the top half of Table 2). More important for present purposes, there was no main effect of age, F(1, 40) = .005, MSe = 1.13, p = .95. There was, however, a significant interaction between age and frequency, F(2, 80) = 4.54, MSe = .36, p = .014. As seen in the top half of Table 2, the increase in estimates between actions imagined two times versus four times was larger for younger adults (Mdifference = 1.2) than older adults (Mdifference = .50). To confirm that this difference drove the age X frequency interaction, we submitted estimates from the 2x and 4x conditions to a 2 (age) X 2 (frequency) ANOVA. The interaction remained significant, F(1, 40) = 9.75, MSe = .29, p = .003. Despite this interaction, mean frequency estimates did not differ significantly as a function of age at any level of frequency (smallest p = .14) and, overall, older and younger adults were generally similar in tracking the number of prior acts of imagination.

Table 2.

Mean non-zero imagination-frequency and performance-frequency responses (with standard errors) for imagined-only actions as a function of age and frequency of imagination.

| Frequency of Imagination | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Age | n | 1x | 2x | 4x |

| Imagination-Frequency | Younger | 16 | 1.4 (.10) | 1.7 (.14) | 2.9 (.29) |

| Older | 26 | 1.6 (.11) | 2.0 (.13) | 2.5 (.21) | |

| Performance-Frequency | Younger | 11 | 1.3 (.12) | 1.6 (.22) | 2.0 (.23) |

| Older | 20 | 1.7 (.18) | 2.0 (.18) | 2.4 (.22) | |

Having established that younger and older adults were about equally likely to remember prior acts of imagination as having been imagined, we next calculated the proportion of those imagined actions correctly identified as imagined that were also identified as performed (i.e., that received a non-zero response on the did scale). Participants who did not identify at least one imagined-only action as imagined at all levels of the frequency variable were excluded from this analysis (n = 1 younger and 8 older adults). Note that a performed response to these actions constitutes a memory illusion because the actions had in fact only been imagined. The proportions of judged-imagined items that were also judged performed were entered into a 2 (age) X 3 (frequency) ANOVA. There was a main effect of age, F(1, 40) = 8.95, MSe = .29, p = .005. As seen in Table 3, of the actions correctly identified as imagined, a greater proportion were also falsely remembered as performed by older adults (M = .49) than by younger adults (M = .19). There was no main effect of repetition and no interaction between age and frequency, F's < 1.

Table 3.

Mean proportion of judged-imagined items that were also judged performed as a function of frequency and age (standard errors in parentheses)

| Frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1x | 2x | 4x |

| Younger | .16 (.09) | .20 (.09) | .21 (.09) |

| Older | .47 (.07) | .51 (.07) | .48 (.07) |

We also recalculated the above proportions relative to all imagined items that were recognized as old, and obtained similar results. The proportion of recognized items given non-zero frequency estimates on both the imagined and did scales was greater for older adults (M = .35) than younger adults (M = .18), F(1, 45) = 5.05, MSe = .18, p = .03. In this analysis, there was also a marginally significant main effect of frequency, F(2, 90) = 2.65, MSe =.04, p = .08, such that responses of both imagined and performed increased somewhat with frequency (M's = .20, .28, .30). The age X frequency interaction was not significant, F < 1.

Thus, although older and younger adults were about equally likely to remember imagining actions that they had in fact imagined, older adults were more likely to falsely remember having also performed those actions at least once. We also tested for age differences in estimates of the number of times the actions had been performed. We calculated for each participant the mean non-zero performed response given to imagined-only actions at each level of frequency (only participants who gave at least one non-zero performed response at all levels of frequency were included in this analysis). Means were submitted to a 2 (age) X 3 (frequency) ANOVA. As seen in the bottom half of Table 2, for both younger and older participants, mean performance-frequency estimates increased with repeated imagination, F(2, 58) = 11.74, MSe = .34, p < .001. Older participants gave marginally higher mean performance-frequency estimates than did younger participants at all frequencies of imagination, F(1,29) = 2.94, MSe = 1.25, p < .10. There was no interaction between age and frequency, F < 1.

Reality-Monitoring of Performed-Only Actions

Reality monitoring of performed-only actions was analyzed in the same manner as that of imagined-only actions. Analysis of correct performed responses to performed-only actions yielded a significant effect only of frequency, F(2, 98) = 11.94., MSe = .03, p < .001. Actions that were performed more times were more likely to be judged performed (M's for 1x, 2x, and 4x = .84, .97, and .997, respectively). Neither the main effect of age nor the interaction between age and frequency were significant, F's < 1. The proportion of correct performed responses was near ceiling for both younger (M = .95) and older adults (M = .93).

Not only were younger and older adults equally likely to remember the performed source of performed-only actions, but they gave similar performance-frequency estimates to these items (see the top half of Table 4). Analysis of these estimates yielded a significant effect of frequency, F(2, 92) = 145.42, MSe = .24, p < .001, such that estimates increased with number of performances (M's for 1x, 2x, and 4x = 1.5, 2.3, and 3.3, respectively). There was no main effect of age and no interaction, F's < 1.

Table 4.

Mean non-zero performance-frequency and imagination-frequency responses (with standard errors) for performed-only actions as a function of age and frequency of performance.

| Frequency of Performance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Age | n | 1x | 2x | 4x |

| Performance-Frequency | Younger | 16 | 1.4 (.14) | 2.2 (.18) | 3.3 (.23) |

| Older | 32 | 1.6 (.10) | 2.4 (.13) | 3.3 (.16) | |

| Imagination-Frequency | Younger | 8 | 1.4 (.19) | 1.2 (.16) | 1.4 (.17) |

| Older | 20 | 1.5 (.12) | 1.6 (.10) | 1.5 (.11) | |

Next we analyzed the proportion of judged-performed items that were also judged imagined (one younger and 2 older adults were excluded from this analysis because they did not identify at least one performed-only action as performed at all levels of the frequency variable). The only significant effect was of frequency, F(2, 92) = 7.09, MSe = .03, p = .001. Actions that were correctly remembered as performed were more likely to also be falsely remembered as imagined the more times they were performed (M's for 1x, 2x, and 4x = .30, .42, and .43, respectively). Older adults were somewhat more likely to give false imagined responses (M = .46) than were younger adults (M = .31) but the main effect of age was not significant, F(1, 46) = 2.16, MSe = .31, p = .15, and neither was the interaction of age and frequency, F(2, 92) = 2.25, MSe = .02, p = .11.

Statistical analysis of mean imagination-frequency estimates given to performed-only actions (see the bottom half of Table 4) yielded no significant effects (smallest p = .14).

Reality Monitoring of Imagined+Performed Actions

To analyze reality monitoring of imagined+performed actions, we first calculated the proportion of these actions that were given non-zero responses on both the imagined and the did scales. This response profile constitutes a completely correct source identification for these items. The proportions were entered into a 2 (age) X 2 (frequency) ANOVA. There was a main effect of frequency, F(1, 49) = 5.94, MSe = .03, p = .02, such that correct source identifications were more common for actions imagined and performed twice (M = .76) versus once (M = .67). More important, there was a marginally significant main effect of age, F(1, 49) = 3.90, MSe = .17, p = .054 , such that source memory was poorer for older (M = .63) than younger adults (M = .80). There was no interaction, F < 1.

Were older adults marginally less likely than younger adults to remember both sources of imagined+performed actions because they were more likely to remember that the actions had been only imagined, only performed, or both? To answer this question, we calculated for each participant the proportion of imagined+performed actions given an imagined-only response (i.e., a non-zero response on the imagined scale and a zero response on the did scale) and the proportion given a performed-only response (i.e. a nonzero response on the did scale and a zero response on the imagined scale). These proportions were submitted to separate 2 (age) X 2 (frequency) ANOVAs. Imagined-only responses were rare and were significantly less common for actions imagined and performed twice (M = .03) versus once (M = .07), F(1, 49) = 6.85, MSe = .01, p = .01. The mean proportion of imagined-only responses was identical for older and younger adults (M = .05). The interaction of age and frequency was not significant, F(1, 49) = 1.13, MSe = .01, p = .29. In sum, both younger and older adults rarely misattributed the source of imagined+performed actions to imagination alone.

In contrast, older adults were significantly more likely to give performed-only responses (M = .33) than were younger adults (M = .15), F(1, 49) = 5.04, MSe = .03, p = .03. The incidence of performed-only responses did not depend on frequency, F(1, 49) = 1.28, MSe = .03, p = .26, and the interaction of age and frequency was not significant, F < 1. Thus, older adults’ source memory deficit for imagined+performed actions was clearly driven by their being less likely to remember imagining the actions.

Finally, to test for age differences in ability to remember exactly how often actions had been both imagined and performed, we calculated each participant's mean non-zero imagined response and mean non-zero performed response to imagined+performed actions. Imagination-frequency and performance-frequency estimates were analyzed in separate 2 (age) X 2 (frequency) ANOVAs. Overall, the mean imagination-frequency estimate was 1.5 and this was not affected by age, frequency, or their interaction, all F's < 1. Performance-frequency estimates showed a markedly different pattern. Participants gave significantly higher mean estimates to actions imagined and performed twice (M = 2.3) versus once (M = 1.7), F(1, 49) = 56.35, MSe = .18, p < .001, and, of greater interest here, older adults gave marginally higher estimates (M = 2.2) than did younger adults (M = 1.8), F(1, 49) = 3.78, MSe = .76, p = .058.

Discussion

We investigated differences between younger and older adults in reality monitoring of action memories using a novel experimental paradigm. Like Thomas and Bulevich (2006), we found that older adults were more likely than younger to misremember imagined-only actions as performed—an error with potentially serious consequences in real-world settings (see Hashtroudi et al., 1990, for a parallel age difference in reality monitoring of memories for more complex actions, such as packing a picnic basket). This finding converges with other literature showing reduced source memory in late adulthood (e.g., Cohen & Faulkner, 1989; Hashtroudi et al., 1990; Henkel, Johnson, & De Leonardis, 1998; Lyle, Bloise, & Johnson, 2006; Glisky, Rubin, & Davidson, 2001; McCabe, Smith, & Parks, 2007; McIntyre & Craik, 1987; Rabinowitz, 1989). Importantly, our procedure allowed us to investigate the fruitfulness of three potential accounts of this age-related reality-monitoring deficit.

In the present experiment, there were three sources of action memories: imagination-only, performance-only, and both imagination and performance. As inferred from old/new recognition rates for action statements, the latter two sources produced memories that were equally stronger than memories arising from imagination-only (for older adults at least). Also memories became stronger with repeated presentations (as indicated by increased hits). Therefore, if older adults were over relying on a general strength or familiarity heuristic (see Figure 1), then the age-related reality-monitoring deficit should have manifested as a greater tendency for older participants to misattribute imagined-only actions to both having only been performed and to having been performed in addition to imagined in an approximately evenly distributed fashion. Yet, for both older and younger participants, imagining actions multiple times versus once decreased misattributions to performance-only. In contrast, attributions that imagined items were imagined and also were performed were proportionally stable across repetitions. Thus, the patterns of these two types of misattributions did not parallel one another. Further, according to the strength heuristic account older adults’ reality-monitoring errors should have exaggerated with repeated presentations (as should have younger adults), because the stronger traces resulting from repetition would increasingly lead to errors. This pattern did not emerge for either type of error just discussed. For instance, regardless of the number of repetitions of imagined actions, older adults judged that about half of the items they remembered imagining were also performed.

These patterns are most consonant with the idea that individuals based their source attributions on qualitative characteristics of their memories for the imagined-only actions (see also Thomas et al., 2003). Imagining an action produces a memorial record of both sensory details and cognitive operations involved in the act of generation (Johnson & Raye, 1981). That is, cognitive operations, which are strongly associated with imagination, will increase belief that actions were imagined at least once. At the same time, the record of sensory details, which is associated with performance more than imagination, will support belief that the actions were performed at least once. The key assumption from the dual-attributions account developed in the introduction is that the sensory information older adults derive from imagination is more similar to that which they derive from performance, perhaps because age-related declines in the sensory-perceptual systems (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997; Verillo, 1993) and/or the process of binding together features in memory (Chalfonte & Johnson, 1996; Naveh-Benjamin, 2000) reduce the amount of sensory information encoded and retained from performance (for a similar idea see Mitchell, Johnson, & Mather, 2003). Thus, older adults would be expected to appropriately attribute imagined-only actions to imagination, but would concomitantly show exaggerated erroneous attributions also to performance relative to younger adults. As noted above, the pattern of reality-monitoring judgments for imagined-only events dovetailed with this expectation.

Another possibility outlined in the introduction is that cognitive operations are underutilized when making reality-monitoring judgments, and especially so for older adults. Several observed patterns disfavor this account. First, one expectation from this account is that repeated imagination should increase the misattribution that actions were only performed (because according to this account, sensory detail becomes enriched through repeated imagination and this type of detail is the primary basis for source attributions, thereby presumably leading to the imagination inflation effect ; see e.g., Thomas et al., 2003). The opposite pattern was actually obtained: With increased imaginations, misattributions of performance-only decreased. Second, older adults should have erroneously attributed imagined-only actions as only performed more so than younger adults. Though the means tended in this direction, the age difference was not statistically reliable. Third, underutilization of cognitive operations might suggest that older adults would be less likely than younger adults to attribute performed-only actions as having been performed and having been imagined (because older adults would be less sensitive to any cognitive operation information that would lead to an imagination misattribution). But older adults were nominally (but not statistically) more likely than younger adults to judge that performed-only actions were performed and were imagined.

Returning to the dual attributions account, two issues bear closer inspection. First, the age-related increase in attributing imagined-only actions as having been imagined and having been performed could simply reflect a general default response strategy for older adults. When uncertain about the source of remembered actions, older adults might have “covered their bases” by providing non-zero responses to both the imagined and the performed judgments, perhaps because there were somewhat more imagined+performed items (54) than imagined or performed only items (42 each) in the study list. The non-significant age increase in such responses to performed-only actions lends some weight to this possibility. However, such a strategy (a bias toward judging an item as performed and also as imagined) would produce accurate source judgments for actions that were actually imagined and performed. Yet, older adults showed marginally significant declines relative to younger adults in (accurately) judging imagined and performed actions as having been both imagined and performed. For these actions, older adults more so than younger adults indicated that the action was performed but not imagined. This pattern is inconsistent with the interpretation that older adults’ tendency was to guess that actions were both performed and imagined.

Second, a central assumption of the dual-attributions account is that older adults’ encoding of sensory characteristics of performed events is somewhat impoverished relative to that of younger adults, and therefore sensory detail does not as well distinguish performed events from imagined events (which also yield some encoding of sensory information) for older as for younger adults (Mitchell et al., 2003, suggest a similar interpretation for age-related increases in source errors in a misinformation paradigm; Raye, Johnson, & Taylor, 1980, more generally propose that in some cases sensory information may not be a very good discriminator between externally and internally generated representations). As far as we are aware, there are no studies that have examined this assumption for enacted actions. However, experiments have shown that voice-specific details of verbal events are not preserved in memory as well for older adults as for younger adults (Pilotti & Beyer, 2002; Pilotti, Meade, & Gallo, 2003). It is plausible that there may also be age-related deficits in encoding other fine-grained perceptual dimensions of events, with the consequence that older adults are less able to differentiate sensory information remembered from actual events from that derived from imagined events.

One testable implication is that older adults may be more likely than younger adults to make reality-monitoring errors even if they are as likely as younger adults to utilize the full range of qualitative characteristics available in their memories of imagined-only actions. Consistent with this suggestion, Thomas and Bulevich (2006, Experiment 2) reported that detailed instructions to consider perceptual and contextual information when making reality-monitoring judgments reduced but did not eliminate the age-related increase in false “performed” responses. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that finding reductions in older adults’ reality-monitoring errors for imagined events (when these adults are encouraged to carefully consider perceptual and contextual information; Thomas & Bulevich, 2006, Experiment 2) is also consistent with the idea that older adults typically underutilize cognitive operations in reality monitoring. Further, the underutilization of cognitive operations idea can account straightforwardly for the present age-related increase in remembering imagined and performed events as only performed. Thus, age differences in reality monitoring may be characterized by both the underutilization and the dual-attributions ideas developed in this article (see Mitchell, Johnson, Raye, Mather, & D'Esposito, 2000, for a similar general idea that age-related deficits in reality monitoring have multiple causes). The present paradigm may have reduced older adults’ tendency to underutilize cognitive operations by requiring participants to separately consider the evidence for imagination and performance for each test item, whereas in contexts in which source judgments are less systematic and more heuristic (see Johnson et al., 1993), older adults may be more prone to underutilize cognitive operations.

Our experiment also addressed the question of whether frequency estimates of illusory performance increase with the number of times actions are imagined. Interestingly, both younger and older participants reported that the frequency of a falsely-remembered performed action increased with repeated imagination of that action. As far as we know, this is the first report that an illusory recollection “imports” details of the frequency of occurrence from the actual event. Note that this finding differs from and extends the seminal work by Johnson and colleagues (Johnson et al., 1977, 1979) showing that repeated imagination (or generation; Raye et al., 1980) increased frequency judgments of actually presented words or pictures and repeated presentation of items increased frequency judgments of imagination. In Johnson and colleagues’ paradigm, frequencies of imagined events were confused with frequencies of presented events. In contrast, in the current experiment frequencies of imagined actions influenced frequency judgments of having performed actions that were never in fact performed, but the frequency of a falsely-remembered imagined action did not increase with repeated performance of that action. Theoretical interpretation of this new effect is uncertain, but one idea is that frequency counts of falsely-remembered performance are estimated based on the amount of sensory information recalled about a particular action, with higher estimates given for actions for which more sensory information is remembered.

Older adults gave numerically higher performance-frequency estimates for imagined-only actions than did younger adults. Although this difference only approached conventional significance levels, it bears noting because it raises the possibility that older adults may not only be more likely to falsely remember performing imagined actions, but they also may remember performing them more often. Additional evidence that imagination more strongly influences the sense of how often actions have been performed in late versus early adulthood comes from the finding that, although older and younger adults gave comparable performance-frequency estimates for actions that were only performed, older adults gave marginally higher performance-frequency estimates than did younger adults for actions that were both performed and imagined.

Finally on a more general note, the idea that imagination can cause memories to have qualitative characteristics that are consistent with sources other than imagination (namely, perception or performance) is widely accepted in the domain of reality-monitoring research (e.g., Henkel & Franklin, 1998; Lane & Zaragoza, 1995; Johnson & Raye, 1981; Kensinger & Schacter, 2006) and, more specifically, in the tradition of the source-monitoring framework (Johnson et al., 1993). The important theoretical point suggested by the present results is that it may be more precise in some cases to say that imagination produces memories with qualitative characteristics that are consistent with sources in addition to imagination, rather than to assume that imagination produces memories that are thought to emanate solely from performance (cf. Goff & Roediger, 1998; Thomas & Bulevich, 2006; Thomas et al., 2003). Note also that the findings represent an instance of a phenomenon pointed out by Lyle and Johnson (2007), which is that the same factor (e.g., repetition of imagination) that improves one type of source memory (e.g., memory for imagination) can simultaneously harm another type of source memory (e.g., memory for performance).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Amanda Price for assistance with participant testing. This work was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant AG17481 to Mark A. McDaniel. Portions of the data presented herein were partially analyzed and reported in McDaniel, Butler, and Dornburg (2006).

Appendix

Blow some bubbles Push the toy car

Bounce the ball Put on the glove

Break the toothpick Put on the hat

Chain the paper clips Put on the ring

Close the bag Put on the sunglasses

Color the star Put on the thimble

Crumple the plastic Put on the watch

Cut the cards Put the cap on the marker

Cut the cloth with the scissors Put the card in the envelope

Draw a circle with the compass Put the glasses in the case

Examine the flower Put the marble in the cup

Fasten the collar Put the match in the box

Fasten the safety pin Put the top on the jar

File your nails Put your hand in the bag

Flatten the clay Remove a tissue

Flip the coin Ring the bell

Flip through the magazine Roll the dice

Fold out the corkscrew Roll the pen on the table

Fold the paper towel Shake the bottle

Lift the stamp with the tweezers Sharpen the pencil

Lift the stapler Shine the flashlight

Light the lighter Slap the jack

Look in the magnifying glass Smell the candle

Look in the mirror Stack the checkers

Make the twist tie into a “V” Stick the pins in the cushion

Measure the can Stir the water in the cup

Open the book Stretch the bungee cord

Open the purse Stretch the rubber band

Pat the toy dog Take the lid off the box

Pick up the chalk Take the pen out of the box

Pick up the nail with the magnet Tear the paper

Play the game Tie a knot in the string

Polish the spoon Tie the shoe

Press the button on the speaker Unfasten the Velcro

Pull off a sticky note Unlock the padlock

Push the napkin through the ring Unzip the zipper

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/pag/

Note that this formulation is consistent with Hoffman's (1997) findings that entirely new items, which presumably have not been strongly encoded and are of low familiarity, tend to be attributed to the source that produces weaker memories.

Analyses of reality-monitoring judgments included only those participants who had at least one hit at all levels of the frequency variable. This excluded 4 older participants in the analyses of imagined-only actions and one younger participant and 2 older participants in the analyses of performed-only actions. No participants were excluded from the analyses of imagined+performed actions. Degrees of freedom differ accordingly between analyses.

Contributor Information

Mark A. McDaniel, Washington University in Saint Louis

Keith B. Lyle, University of Louisville

References

- Anderson RE. Did I do it or did I only imagine doing it? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1984;113:594–613. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Lindenberger U. Emergence of a powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: A new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology and Aging. 1997;12:12–21. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer WF. Qualitative analysis of the recalls of randomly sampled autobiographical events. In: Gruneberg MM, Morris PE, Sykes RN, editors. Practical aspects of memory: Current research and issues, Vo1ume 1: Memory in everyday life. John Wiley; New York: 1988. pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Butler KM, McDaniel MA, Dornburg CC, Price AL, Roediger HL., III Age differences in veridical and false recall are not inevitable: The role of frontal lobe function. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2004;11:921–925. doi: 10.3758/bf03196722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfonte BL, Johnson MK. Feature memory and binding in young and older adults. Memory & Cognition. 1996;24:403–416. doi: 10.3758/bf03200930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G, Faulkner D. Age differences in source forgetting: Effects on reality monitoring and on eyewitness testimony. Psychology and Aging. 1989;4:10–17. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durso FT, Johnson MK. The effects of orienting task on recognition, recall, and modality confusion of pictures and words. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1980;19:416–429. [Google Scholar]

- Engelkamp J. Memory for actions. Psychology Press; Hove, East Sussex: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Finke RA, Johnson MK, Shyi GCW. Memory confusions for real and imagined completions of symmetrical visual patterns. Memory & Cognition. 1988;16:133–137. doi: 10.3758/bf03213481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley MA, Johnson MK. Confusions between memories for performed and imagined actions: A developmental comparison. Child Development. 1985;56:1145–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1985.tb00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry M, Manning CG, Loftus EF, Sherman SJ. Imagination inflation: Imagining a childhood event inflates confidence that it occurred. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1996;3:208–214. doi: 10.3758/BF03212420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisky EL, Rubin SR, Davidson PSR. Source memory in older adults: An encoding or retrieval problem? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2001;27:1131–1146. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.27.5.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff LM, Roediger HL., III Imagination inflation for action events: Repeated imaginings lead to illusory recollections. Memory & Cognition. 1998;26:20–33. doi: 10.3758/bf03211367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashtroudi S, Johnson MK, Chrosniak LD. Aging and qualitative characteristics of memories for perceived and imagined complex events. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:119–126. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel LA, Franklin N. Reality monitoring of physically similar and conceptually related objects. Memory & Cognition. 1998;26:659–673. doi: 10.3758/bf03211386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel LA, Johnson MK, De Leonardis DM. Aging and source monitoring: Cognitive processes and neuropsychological correlates. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1998;127:251–268. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.127.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HG. Role of memory strength in reality monitoring decisions: Evidence from source attribution biases. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1997;23:371–383. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.23.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Hashtroudi S, Lindsay DS. Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:3–28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Raye CL. Reality monitoring. Psychological Review. 1981;88:67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Raye CL, Wang AY, Taylor TH. Fact and fantasy: The roles of accuracy and variability in confusing imaginations with perceptual experiences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. 1979;5:229–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Taylor TH, Raye CL. Fact and fantasy: The effects of internally generated events on the apparent frequency of externally generated events. Memory & Cognition. 1977;5:116–122. doi: 10.3758/BF03209202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kausler DH, Lichty W, Freund JS. Adult age differences in recognition memory and frequency judgments for planned versus performed activities. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:647–654. [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Schacter DL. Neural processes underlying memory attribution on a reality-monitoring task. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16:1126–1133. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane SM, Zaragoza MS. The recollective experience of cross-modality confusion errors. Memory & Cognition. 1995;23:607–610. doi: 10.3758/bf03197262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyle KB, Bloise SM, Johnson MK. Age-related binding deficits and the content of false memories. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:86–95. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyle KB, Johnson MK. Source misattributions may increase the accuracy of source judgments. Memory & Cognition. 2007;35:1024–1033. doi: 10.3758/bf03193475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe DP, Smith AD, Parks CP. Inadvertent plagiarism in younger and older adults: The role of working memory capacity in reducing memory errors. Memory & Cognition. 2007;35:231–241. doi: 10.3758/bf03193444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Butler KM, Dornburg C. Binding of source and content: New directions revealed by neuropsychological and age-related effects. In: Zimmer HD, Mecklinger A, Lindenberger U, editors. Handbook of binding and memory: Perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. pp. 657–675. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis D, Roberts P. Qualitative characteristics of vivid memories attributed to real and imagined experiences. American Journal of Psychology. 1996;109:59–77. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre JS, Craik FI. Age differences in memory for item and source information. Canadian Journal of Psychology. 1987;41:175–192. doi: 10.1037/h0084154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Johnson MK, Mather M. Source monitoring and suggestibility to misinformation: Adult age-related differences. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2003;17:107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Johnson MK, Raye CL, Mather M, D'Esposito M. Aging and reflective processes of working memory: Binding and test load deficits. Psychology and Aging. 2000;15:527–541. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morell RW, Park DC, Kidder DP, Martin M. Adherence to antihypertensive medications across the life span. Gerontologist. 1997;37:609–619. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveh-Benjamin M. Adult age differences in memory performance: Tests of an associative deficit hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2000;26:1170–1187. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.26.5.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilotti M, Beyer T. Perceptual and lexical components of auditory repetition priming in young and older adults. Memory & Cognition. 2002;30:226–236. doi: 10.3758/bf03195283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilotti M, Meade ML, Gallo DA. Implicit and explicit measures of memory for perceptual information in young adults, healthy older adults, and patients with Alzheimer's disease. Experimental Aging Research. 2003;29:15–32. doi: 10.1080/03610730303708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raye CL, Johnson MK, Taylor TH. Is there something special about memory for internally generated information? Memory & Cognition. 1980;8:141–148. doi: 10.3758/bf03213417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz JC. Judgments of origin and generation effects: Comparisons between young and elderly adults. Psychology and Aging. 1989;4:259–268. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger HL, III, McDaniel MA. Illusory recollection in older adults: Testing Mark Twain's conjecture. In: Garry M, Hayne H, editors. Do justice and let the sky fall: Elizabeth F. Loftus and her contributions to science, law, and academic freedom. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley WC. A self-administered scale for measuring intellectual impairment and deterioration. Journal of Psychology. 1940;9:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Suengas AG, Johnson MK. Qualitative effects of rehearsal on memories for perceived and imagined complex events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1988;117:377–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AK, Bulevich JB. Effective cue utilization reduces memory errors in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:379–389. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AK, Bulevich JB, Loftus EF. Exploring the role of repetition and elaboration in the imagination inflation effect. Memory & Cognition. 2003;31:630–640. doi: 10.3758/bf03196103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AK, Loftus EF. Creating bizarre false memories through imagination. Memory & Cognition. 2002;30:423–431. doi: 10.3758/bf03194942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verillo RT. The effects of aging on the sense of touch. In: Verillo RT, editor. Sensory research: Multimodal Perspectives. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1993. pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]