Abstract

Anion-transport proteins are central to all of physiology, for processes ranging from regulating bone-density, muscle excitability, and blood pressure, to facilitating extreme-acid survival of pathogenic bacteria. 4,4-Diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS) has been used as an anion-transport inhibitor for decades. In this study, we demonstrate that polythiourea products derived from DIDS hydrolysis inhibit three different CLC chloride-transport proteins, ClC-ec1, ClC-0, and ClC-Ka, more effectively than DIDS itself. The structures of the five major products were determined by NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and chemical synthesis. These compounds bind directly to the CLC proteins, as evidenced by the fact that inhibition of ClC-0 occurs only from the intracellular side and inhibition of ClC-Ka is prevented by the point mutation N68D. These polythioureas are the highest affinity inhibitors known for the CLCs and provide a new class of chemical probes for dissecting the molecular mechanisms of chloride transport.

Chloride transport across cellular membranes is crucial for a striking array of physiological processes, including transepithelial transport, membrane excitability, volume regulation, and organelle acidification (1-4). Human diseases associated with defects in chloride transport affect muscle, brain, kidneys, bones, lungs, pancreas, eyes, and ears. The CLC “chloride channel” family is expressed broadly in nearly all organisms, with nine members found in mammals. Specific and high affinity inhibitors could serve as potential therapeutics for treatment of certain homologue-specific disorders including osteoporosis, high blood pressure, and food poisoning (5-7) and as probes for understanding the similarities and differences between CLC ion channels and chloride-proton antiporters (8-10). Indeed, the structure and mechanisms of cation-selective channels have been illuminated through the use of small molecule inhibitors (11-16). Although there has been recent progress in identifying inhibitors of the ClC-K homologues (17), the CLCs in general lack the extensive array of small-molecule modulators available for other membrane proteins.

Despite the dearth of high-affinity and specific inhibitors of CLC chloride-transport proteins, a handful of low-affinity and nonspecific inhibitors are known. One such inhibitor, 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS), affects several chloride-transport proteins (18-22). Our interest in this particular chloride-transport inhibitor stems from its ability to inhibit ion flux in the Escherichia coli CLC protein ClC-ec1 (21), the only chloride-transport protein of known structure (23, 24). Our initial goal was to determine the structure of ClC-ec1 with DIDS bound, since this information would be in-valuable for understanding the mechanism of inhibition and could also facilitate the design of more effective inhibitors. The pursuit of this goal led us to the serendipitous discovery that DIDS hydrolysis products are the most potent CLC inhibitors known.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Inhibition of a Prokaryotic CLC by DIDS Hydrolysis Products

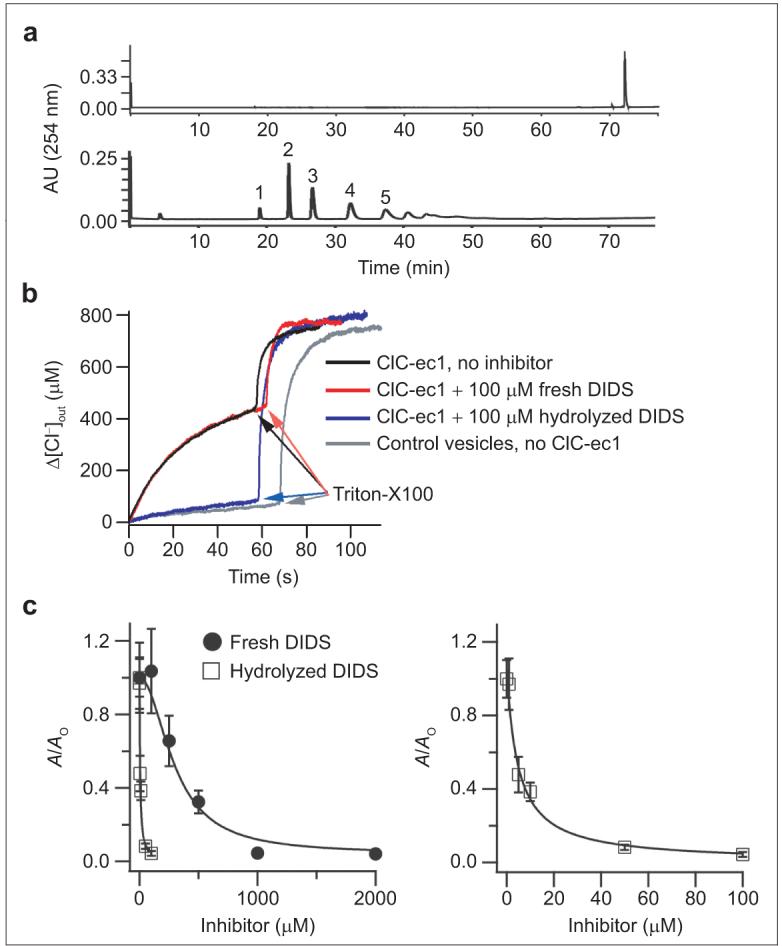

DIDS is known to be unstable in aqueous solution (25). In efforts to determine the structure of ClC-ec1 with DIDS bound, it was necessary to examine the stability of DIDS in greater detail. Chromatographic analysis of a freshly prepared solution of DIDS showed a single peak on reversed-phase HPLC (Figure 1, panel a, top); however, within 24 h in solution, DIDS was partially decomposed (data not shown), and after 48 h, no DIDS was apparent in the HPLC trace (Figure 1, panel a, bottom).

Figure 1.

Hydrolyzed DIDS mixture inhibits ClC-ec1 better than freshly prepared DIDS. a) Reversed-phase HPLC chromatogram of a freshly prepared solution of DIDS (top) or hydrolyzed DIDS (bottom). The numbers above each peak represent the fraction numbers referred to throughout the paper. b) Chloride flux assays, measuring the change in extravesicular chloride concentration as a function of time. Triton X-100 was added to determine the total intravesicular chloride concentration. c) Chloride flux through ClC-ec1 was measured at several concentrations of freshly prepared DIDS (closed circles) or hydrolyzed DIDS mix (open squares). The activity (A, defined as the initial rate of chloride efflux through ClC-ec1-containing vesicles minus the initial rate of chloride efflux through control vesicles) is normalized to the activity observed in the absence of inhibitor (Ao). In the right panel, the effects of the hydrolyzed DIDS mix are shown on an expanded scale. Symbols represent the mean activity from four to five assays, and error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Solid lines are fits to the Hill equation: A/Ao = (A/Ao)max/[1 + (K1/2/[Inhibitor])-n] where K1/2 is the apparent affinity and n is the Hill coefficient. For the hydrolyzed DIDS mixture, (A/Ao)max = 1.06, K1/2 = 4.8 μM, and n = 1. For freshly prepared DIDS, (A/Ao)max = 1.08, K1/2 = 300 μM, and n = 2.

To test whether any of the DIDS hydrolysis products were modulators of ClC-ec1, we used chloride flux assays to measure the activity of ClC-ec1 in the absence and presence of the hydrolyzed DIDS mixture (Figure 1, panels b and c). To our surprise, the hydrolyzed DIDS mixture inhibits ClC-ec1 substantially better than the DIDS itself. While DIDS inhibits ClC-ec1 with an apparent affinity of ∼300 μM, the hydrolyzed DIDS mixture inhibits ClC-ec1 with an apparent affinity of ∼5 μM (Figure 1, panel c). This result requires that at least one of the DIDS hydrolysis products is a more potent inhibitor than DIDS itself.

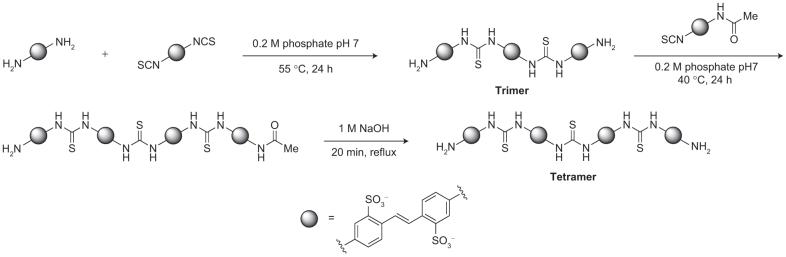

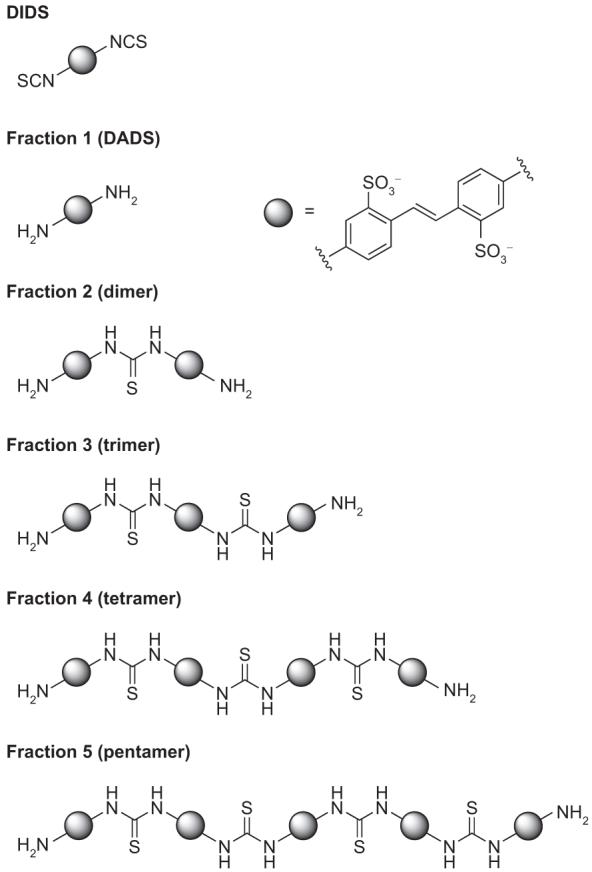

To identify which DIDS hydrolysis product(s) inhibit ClC-ec1, we isolated each of the five major compounds observed in the HPLC chromatogram of the decomposed mixture (Figure 1, panel a, bottom). Mass spectrometry and 1H NMR were used to characterize each of these compounds. Fraction 1 corresponds to 4,4′-diaminostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DADS), a compound in which both isothiocyanate groups in DIDS had been hydrolyzed to the corresponding primary amines (Figure 2). Subsequent reaction of an amino group with an isothiocyanate moiety on DIDS forms a thiourea-linked dimer (Supplementary Figure 1). The multimerization of DIDS and DADS units leads to the formation of polythioureas of distinct molecular weights. The size and molecular weight of these multimeric species corresponds to their elution time on reversed-phase HPLC such that the second fraction collected represents the dimer, the third fraction the trimer, the fourth fraction the tetramer, and the fifth fraction the pentamer (Figure 2). Mass spectrometry and 1H NMR spectroscopy established the structures as these unique thiourea adducts. In addition, the structural assignment was corroborated through independent chemical synthesis of the trimer and tetramer species (Scheme 1). The synthesized compounds had identical 1H NMR spectra to the isolated fractions 3 and 4, respectively.

Figure 2.

Identity of DIDS hydrolysis products

Scheme 1.

Independent synthesis of tetramer.

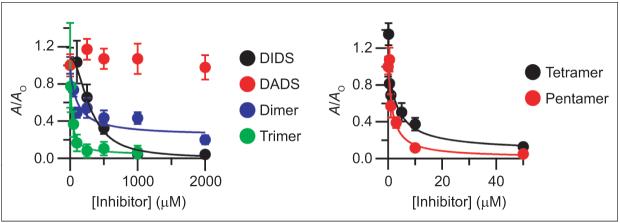

The efficacy of each fraction as a ClC-ec1 inhibitor was assessed using Cl- flux assays. Although DADS does not affect ClC-ec1 activity at concentrations as high as 2 mM, the dimer, trimer, tetramer, and pentamer all inhibit ClC-ec1 (Figure 3). While DIDS has an apparent affinity of only 300 μM, the dimer, trimer, tetramer, and pentamer inhibit with apparent affinities of 110, 20, 3.4, and 1.5 μM, respectively. Hence, the higher molecular weight thioureas inhibit ClC-ec1 with the greatest potency.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of ClC-ec1 by DIDS hydrolysis products. Activity is reported as in Figure 1, panel c. DIDS (black), DADS (red), dimer (blue), and trimer (green) are shown in the left panel. Tetramer (black) and pentamer (red) are shown in the right panel (note the different x-axis scales on the two graphs). The markers represent the mean activity from three to five experiments, and error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Fits are to the Hill equation: (A/Ao) = (A/Ao)min + [(A/Ao)max - (A/Ao)min]/ [1 + (K1/2/[Inhibitor])-n]. The fit with freshly prepared DIDS solution is the same as shown in Figure 1. For all purified fractions, the Hill coefficient (n) was held at 1. For the dimer, trimer, tetramer, and pentamer, K1/2 values were 110, 20, 3.4, and 1.5 μM, respectively.

Inhibition of Eukaryotic CLCs by DIDS Polythioureas

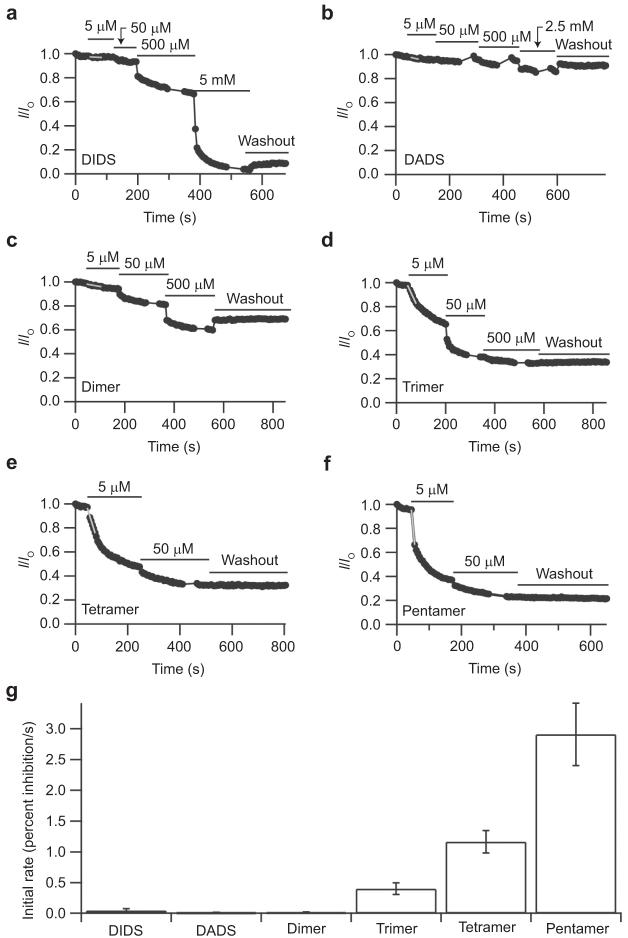

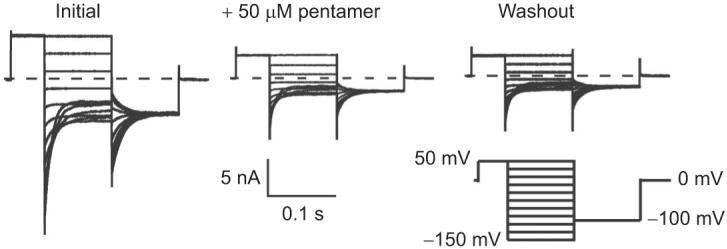

Since the eukaryotic CLC ion channels ClC-0 and ClC-Ka are known to be inhibited by DIDS (19, 20, 26), we assessed the effects of the DIDS hydrolysis products on these proteins. Figure 4 shows representative ClC-0 currents recorded from inside-out patches. Initial currents are shown on the left. Addition of 50 μM pentamer to the intracellular side inhibits ClC-0 significantly (center). Inhibition by the pentamer is irreversible, at least within 5 min of washing (right), as was observed with inhibition of ClC-0 by DIDS itself (19).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of ClC-0 by intracellular application of pentamer. Representative current families are shown from inside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes expressing ClC-0. Currents were measured initially (left), after steady-state inhibition in 50 μM pentamer (center), and after washing out unbound pentamer for 5 min (right). Currents were elicited by the voltage protocol shown below the trace on the right.

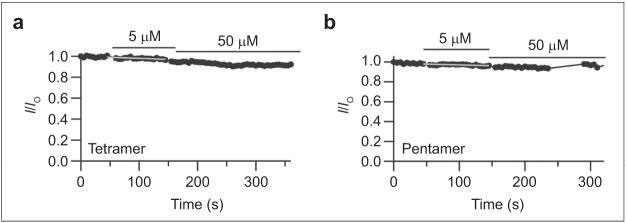

We additionally tested the other DIDS hydrolysis products on ClC-0 to determine whether the size of each compound correlated with inhibitor potency, as noted with ClC-ec1. We found that DADS has no effect, but the dimer, trimer, tetramer, and pentamer all inhibit ClC-0 with successively increasing effectiveness (Figure 5, panels b-f). In all cases, inhibition of ClC-0 was irreversible, at least within 5-10 min of washing. To compare the efficacy of each compound, rates of inhibition were measured. Inhibition by the dimer and trimer could be fit by a single exponential, but inhibition by the tetramer, pentamer, and DIDS required a double exponential to fit. Due to the difficulties in interpreting these multiple exponentials, we measured the initial rate of inhibition in the presence of 5 μM solutions of each fraction. As shown in Figure 5, panel g, the initial rate of inhibition increases with the molecular weight of each oligomer. Thus, inhibition of ClC-0 follows the same pattern of inhibition as observed with ClC-ec1. Since the rate of inhibition by the pentamer was very fast compared to our sampling time, it was only possible to fit the first two to three points to determine the instantaneous rate (Figure 5f). Hence, the measured rate might be an underestimate, but this does not change the conclusion that the pentamer is the fastest inhibitor. As was observed with DIDS (19), the tetramer and pentamer did not significantly inhibit ClC-0 from the extracellular side of the channel (Figure 6). This result suggests that the larger polythioureas bind to specific regions on the ClC-0 channel and are not simply aggregating to the protein or membrane in a nonspecific fashion.

Figure 5.

Effects of intracellular application of DIDS and DIDS hydrolysis products on ClC-0. Time courses of inhibition were measured from inside-out patches for various concentrations of DIDS, DADS, the dimer, trimer, tetramer, and pentamer (panels a-f, respectively). The instantaneous open-channel current at -100 mV (from a prepulse to +50 mV) was determined as a function of time, and current at each time point is normalized to the initial current. The bars above the currents represent the time during which the indicated concentration of inhibitor was applied. Fits of the initial rate of inhibition are shown in gray. g) Initial rate of inhibition (mean ± standard error of mean) by 5 μM of each compound, as determined from three to five experiments from separate oocytes.

Figure 6.

Effects of extracellular application of the tetramer and pentamer on ClC-0. Time courses were measured from outside-out patches where various concentrations of a) tetramer and b) pentamer were applied during the times indicated by the bars above the currents. Measurements were made as described for Figure 5, and each experiment was repeated on three to four separate oocytes.

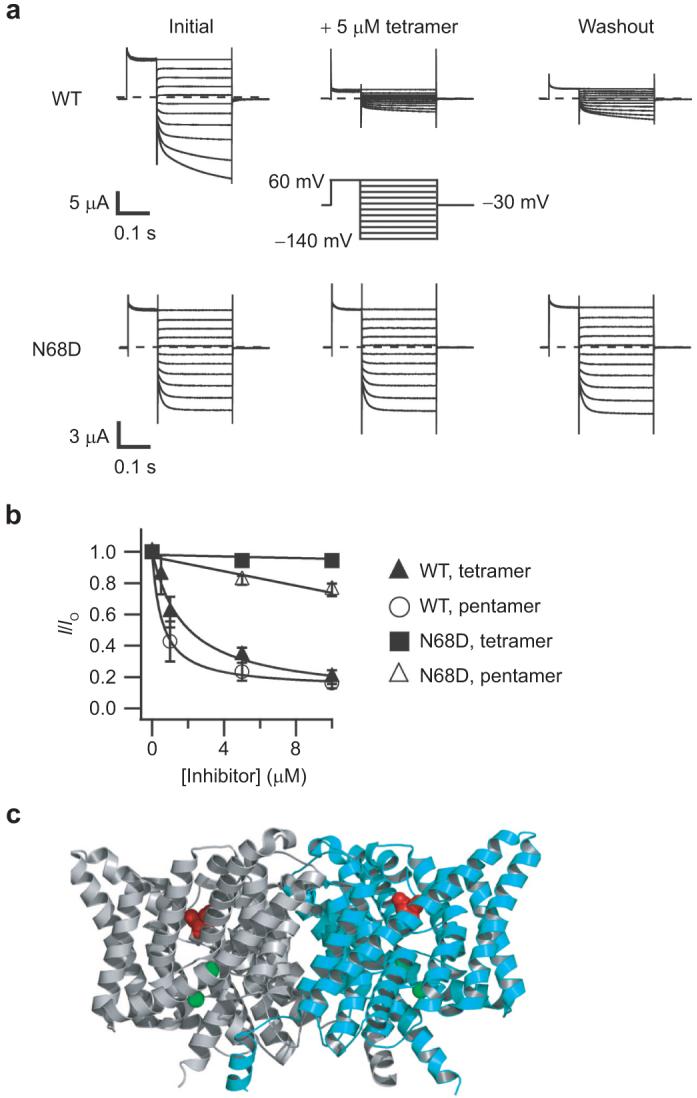

In contrast to ClC-0, ClC-Ka is inhibited by DIDS from the extracellular side, and this inhibition is slowly reversible (20). Hence, we tested whether ClC-Ka is also inhibited from the extracellular side by the tetramer and pentamer. The top portion of Figure 7, panel a, shows representative wild-type ClC-Ka currents. On the left, currents before the addition of inhibitor are shown. The tetramer significantly inhibits wild-type ClC-Ka currents (center). Inhibition is at least partially reversible (right), but due to the slow off rate, we were unable to determine whether complete reversibility is possible. The fraction of current remaining after treatment with different concentrations of the tetramer and pentamer is shown in Figure 7, panel b. In each case, the inhibition had reached a steady-state level, and longer incubations did not change the amount of inhibition. The tetramer inhibits ClC-Ka with an apparent affinity of ∼2 μM, and the pentamer inhibits with an apparent affinity of ∼0.5 μM (50-200 times more potent than DIDS itself (20)).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of ClC-Ka and the N68D mutant by extracellular application of the tetramer and pentamer. a) Representative current families are shown from two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings of Xenopus oocytes expressing wild-type ClC-Ka (top) or ClC-Ka containing the point mutant N68D (bottom). Currents were measured initially (left), after steady-state inhibition in 5 μM tetramer (center), and after washing out unbound tetramer for several minutes (right). The voltage protocol is shown in the center. b) The fraction of current remaining after steady-state application of inhibitor is plotted as a function of inhibitor concentration. These currents were measured at the end of the 250 ms test pulse. Solid symbols represent mean inhibition of wild-type (triangles) or the N68D mutant (squares) by the tetramer. Open symbols represent mean inhibition of wild-type (circles) or the N68D mutant (triangles) by the pentamer. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Experiments were repeated on three to six oocytes. Fits of the wild-type data were to a Hill equation, (I/Io) = (I/Io)min + [1 - (I/Io)min]/[1 + (K>1/2/[Inhibitor])-n], with n held at 1. For the tetramer, (I/Io)min = 0.07, and K1/2 = 1.8 μM. For the pentamer, (I/Io)min = 0.13, and K1/2 = 0.5 μM. N68D data were fit to a line for easy visualization. c) Structure of ClC-ec1 showing the location of the N68 equivalent residue (D54) spacefilled in red (24). The two subunits are colored gray and cyan, and the two bromide ions bound in the presumed anion permeation pathway are spacefilled in green.

In ClC-Ka, the N68D point mutation has previously been shown to decrease the apparent affinity for DIDS 10-fold without otherwise changing the function of ClC-Ka (20). We hypothesized that if the tetramer and pentamer bind to the same site as DIDS, this point mutation should decrease the affinity of the polythioureas. Indeed, we found that the point mutation N68D nearly completely eliminates inhibition by both the tetramer and pentamer, at least at concentrations up to 10 μM (Figure 7, panels a, bottom, and b). The structure of ClC-ec1 can be used to map the position of this point mutation. The region surrounding this residue is well conserved, and the corresponding residue, D54 in ClC-ec1, lies in a cavity located externally to the chloride-binding sites (Figure 7, panel c, spacefilled in red). Since ClC-0 contains an aspartic acid at this position and the N68D mutation in ClC-Ka prevents inhibition by DIDS and the polythioureas, it is not surprising that ClC-0 is not inhibited by these compounds from the extracellular side. Four other ClCs are also not inhibited by DIDS from the extracellular side—ClC-ec1, ClC-2, ClC-3, and ClC-5 (21, 27-29); these CLCs all contain negatively charged amino acids at this position and, hence, are also unlikely to be inhibited from the extracellular side by these polythioureas.

Inhibition of Membrane Proteins by DIDS

DIDS has been used as an inhibitor of many anion-transport proteins for nearly four decades (18-22, 30-33). Its efficacy is thought to be due at least in part to the negatively charged sulfonates, which can be energetically stabilized in or near anion-permeation pathways. In addition, DIDS also acts on a number of proteins that are not involved in anion transport. For example, DIDS inhibits ATP-sensitive K+ channels (34) and some P-type ATPases (35), activates the Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release mechanism in muscle cells (36, 37), the phosphatase activity of the erythrocyte membrane Ca2+-ATPase (38), and an endogenous cation conductance in X. laevis oocytes (39), and modifies the channel properties of the cardiac ryanodine receptor (40). This lack of specificity by DIDS presumably stems from its isothiocyanate groups, which can covalently react with accessible nucleophiles on proteins.

The mechanism of action by DIDS has best been characterized in the AE1 protein from erythrocytes, originally known as Band 3, where DIDS and related stilbene derivatives have helped to elicit the mechanism of transport in great detail (18). Although with AE1 it is clear that DIDS itself is the inhibitor, this is not the case for most of the other myriad proteins studied. In fact, DIDS was originally thought to activate an unknown cation conductance in both Xenopus oocytes and human erythrocytes, and it was recently found that these effects could be replicated only by hydrolyzed DIDS, not DIDS itself (41). Our quest to determine the structure of ClC-ec1 in complex with DIDS led us to the discovery that DIDS hydrolyzes to form DIDS thiourea oligomers, which inhibit three different CLC proteins more potently than DIDS itself.

Dependency of Inhibition on Size of Polythioureas

In both ClC-ec1 and ClC-0, the efficacy of the inhibitor is directly related to the size of the oligomer, with the tetramer and pentamer being the most potent. This result raises the question of whether the shape or charge (or a combination of these factors) is responsible for these changes in potency. It is titillating to note that the length of the fully extended tetramer is approximately 47 Å (42). CLCs are dimeric proteins where each subunit has an independent chloride permeation pathway, and in the structure of ClC-ec1, the distance between the chloride permeation pathways in both subunits is almost exactly the same (46 Å). This suggests that perhaps one reason for the added potency of the tetramer and the pentamer is that one end can bind to and inhibit one monomer’s chloride pathway, and then the other end is in close proximity to block the other subunit’s pathway. In other words, perhaps the tetramers and pentamers are long enough to act as tethered blockers (43, 44). Due to the difficulty in purifying sufficient quantities of the larger oligomers, we were unable to test whether a hexamer would have been even more potent. Further studies will be necessary to test this hypothesis.

One might speculate that these larger oligomers could act nonspecifically to compromise the protein or the membrane. Our experiments with the two eukaryotic CLCs, however, counter this argument. With ClC-0, the polythioureas inhibit only from the intracellular side of the membrane. Moreover, the N68D mutation in ClC-Ka abolishes extracellular inhibition. The fact that we observe the side-specificity of inhibition on ClC-0 and that a single point mutation can prevent inhibition of ClC-Ka strongly suggests that the inhibitors are acting directly by binding to the CLC proteins.

Implications Regarding Inhibition by DIDS Itself

Since the isothiocyanate groups make DIDS unstable in aqueous solution, a concerted effort was made to minimize the time between preparing the DIDS solution and performing the biological assays. Despite such efforts, DIDS hydrolysis cannot be prevented completely. Since the inhibition of the CLCs by ≤0.5% contamination of the pentamer would be indistinguishable from the inhibition that is observed with a freshly prepared solution of DIDS, we cannot rule out the possibility that previously reported inhibition of CLC proteins by DIDS is solely due to small amounts of hydrolysis products. The fact that the polythioureas derived from DIDS hydrolysis inhibit three different CLC chloride transport proteins better than DIDS itself suggests that these hydrolysis products may be responsible for at least some of the previously reported effects of DIDS on CLCs and other proteins. If this is the case, small differences in the amount of hydrolysis that occurs during the synthesis and purification of DIDS could result in significant disparity in the potency of different batches of DIDS, consistent with variability reported in the literature (25, 41).

Future Directions

The discovery of these novel inhibitors—which have the highest affinity yet reported for a CLC—has provided a new class of small molecules to probe the structure and function of these chloride-transport proteins. Since these polythioureas are more stable and have a higher affinity than DIDS, they should be amenable to cocrystallization with ClC-ec1, and our efforts in this direction are ongoing. The ability to directly determine where these inhibitors bind will provide valuable insight into the mechanisms of inhibition and ion transport in the CLC proteins. Additionally, CLC inhibitors could have clinical relevance for treating diseases (5, 6); thus, further work to assess the pharmacology and cellular toxicity of these compounds is warranted.

METHODS

Hydrolysis of DIDS and Identification of DIDS Hydrolysis Products

DIDS disodium salt (100 mg, 0.2 mmol, Invitrogen, Catalog D337, Lot 23382W) was dissolved in 10 mL of 0.2 M pH 7 aqueous NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 buffer. The solution was allowed to stand at 50 °C for 48 h in the absence of light. The reaction mixture was then filtered in portions through 0.2 μm PTFE syringe filters, and the products were purified using reversed-phase HPLC (10 × 1 mL injections) on a C18 semipreparative column (Alltech, 10 μm, 10 mm × 250 mm, 254 nm detection). A multistep, linear MeCN gradient in pH 7 aqueous 50 mM ammonium acetate was used with a flow rate of 2 mL/min (Supplementary Figure 2). The first five products were collected (Figure 1 panel a, bottom, and Supplementary Figure 2), and the solutions were lyophilized to yield yellow solids. Each product was dissolved in D2O, and solution concentrations for all samples were determined using 1H NMR against a tert-butanol standard of known concentration. Samples were subsequently lyophilized and stored in the solid form until the day of use in CLC inhibition experiments.

Fraction 1 (DADS, 2.2 mg, 3%): 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz) δ 7.66 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.64 (s, 2H), 7.30 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4, 0.8 Hz), 6.97 (dd, 2H, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz) ppm.

Fraction 2 (dimer, 10.9 mg, 15%): 1H NMR (D2O, 500 MHz) δ 7.91-7.86 (m, 6H), 7.77-7.73 (m, 4H), 7.54 (dd, 2H, J = 8.5, 2.0 Hz), 7.31 (dd, 2H, J = 2.5, 1.0 Hz), 6.98 (dd, 2H, J = 8.5, 2.5 Hz) ppm; HRMS (ES-) calcd for C29H26N4O12S5 782.0151 found 781.0117 [M - H]-.

Fraction 3 (trimer, 8.6 mg, 10%): 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz) δ 7.94-7.87 (m, 12H), 7.80-7.76 (m, 4H), 7.57 (dt, 4H, J = 2.0, 0.8 Hz), 7.37 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4, 0.8 Hz), 7.03 (dd, 2H, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz) ppm; HRMS (ES-) calcd for C44H38N6O18S8 1194.0008, found 595.9915 [M - 2H]2-.

Fraction 4 (tetramer, 5.3 mg, 6.6%): 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz) δ 7.97-7.88 (m, 18H), 7.80-7.76 (m, 4H), 7.62-7.57 (m, 6H), 7.30 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 6.95 (dd, 2H, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz) ppm; MS (see below for discussion).

Fraction 5 (pentamer, 3.3 mg, 4.0%) 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz) δ 7.97-7.90 (m, 24H) 7.82-7.78 (m, 4H), 7.62-7.58 (m, 8H), 7.38 (d, 2H, J = 2.8 Hz), 7.04 (dd, 2H, J = 8.4, 2.8 Hz) ppm; MS (see below for discussion).

Purified, desalted HPLC fractions were analyzed by electro-spray ionization ion trap mass spectrometry. The full scan spectra of fractions 4 and 5 were contaminated with source fragmentation; however, ions corresponding to the tetramer [M - 2H]2- at m/z 802 and pentamer [M - 4H]4- at m/z 504 were observed for fractions 4 and 5, respectively. To further characterize these ions, we used collision induced dissociation (CID). Collision of the [M - 2H]2- ion resulted in the appearance of singly and doubly charged product ions indicative of a trimer capped with an amino group and an isothiocyanate at m/z 1235 and 617. Singly charged product ions for the diamino trimer, diamino dimer, the dimer and monoamino isothiocyanate monomer, and DADS were also observed in the CID spectrum (Supplementary Table 1), consistent with the fragmentation of a tetramer to smaller oligomers. Isolation of the [M - 4H]4- ion at m/z 504 from fraction 5 and subsequent collision with helium gas resulted in a large number of product ions. Fragment ions corresponding to the diamino tetramers, trimers, dimers, and DADS were readily identifiable in the CID spectrum (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, product ions for the monoamino isothiocyanates of the tetramer, trimer, and dimer were also detectable (Supplementary Table 1). This series of product ions from the CID indicated that fraction 5 contained the pentamer. Moreover, the product ions in the MS2 spectra corresponding to both the diamino and monoamino isothiocyanate in these fractions are consistent with the cleavage of a thiourea bond. To confirm the mass spectrometry results, the trimer and tetramer products were independently synthesized.

Trimer Preparation

DIDS disodium salt (50 mg, 0.10 mmol) and DADS (168 mg, 0.30 mmol, 3 equiv) were suspended in 10 mL of 0.2 M pH 7 aqueous NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 buffer. The mixture was stirred at 50 °C for 48 h in the absence of light. The opaque suspension was then filtered in portions through 0.2 μM PTFE syringe filters, and the product was purified using reversed-phase HPLC. The HPLC fractions were combined and lyophilized to give a yellow powder. This material was redissolved in D2O, and the solution concentration was determined using 1H NMR against a tert-butanol standard of known concentration. The sample was subsequently lyophilized and stored in the solid form (24 mg, 15%). 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz) δ 7.94-7.87 (m, 12H), 7.80-7.76 (m, 4H), 7.57 (dt, 4H, J = 2.0, 0.8 Hz), 7.37 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4, 0.8 Hz), 7.03 (dd, 2H, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz) ppm.

Tetramer Preparation

4-Acetamido-4′-isothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate (SITS, Fluka) disodium salt (3 mg, 6 μmol) was added to a solution of trimer (12 mg, 10 μmol, 1.7 equiv) in 2 mL of 0.2 M pH 7 aqueous NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 buffer. The solution was allowed to stand at 40 °C for 24 h. The reaction mixture was then filtered through a 0.2 μM PTFE syringe filter, and the product was purified using reversed-phase HPLC. The HPLC fractions were combined and lyophilized to give a yellow powder. This material was redissolved in D2O, and the solution concentration was determined using 1H NMR against a tert-butanol standard of known concentration. The sample was subsequently lyophilized and stored in the solid form (3 mg, 32%). 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz) δ 7.96-7.85 (m, 21H), 7.81-7.70 (m, 4H), 7.63 (dd, 1H, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz), 7.59-7.58 (m, 4H), 7.43 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.10 (dd, 1H, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz), 2.18 (s, 3H) ppm.

The monoacetylated tetramer (3 mg, 2 μmol) was dissolved in NaOH (3.0 mL, 1.0 M) and stirred at reflux for 25 min. The solution was cooled, and the pH was adjusted to 7 using 1.0 M aqueous HCl (∼2 mL). The sample was then filtered in portions through 0.2 μM PTFE syringe filters, and the product was purified using reversed-phase HPLC. The HPLC fractions were combined and lyophilized to give a yellow powder. This material was redissolved in D2O, and the solution concentration was determined using 1H NMR against a tert-butanol standard of known concentration. The sample was subsequently lyophilized and stored in the solid form (1 mg, 28%). The 1H NMR spectrum of this product matched that obtained for fraction 4 of the DIDS hydrolysis; in addition, the two compounds coeluted when run on reversed-phase HPLC. 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz) δ 7.97-7.88 (m, 18H), 7.80-7.76 (m, 4H), 7.62-7.57 (m, 6H), 7.30 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 6.95 (dd, 2H, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz) ppm.

Expression, Purification, and Reconstitution of ClC-ec1

ClC-ec1 containing a C-terminal polyhistidine (His) tag was overexpressed in E. coli and purified as described (45). ClC-ec1 was reconstituted into E. coli polar lipids (Avanti Polar Lipids) at 0.4 mg of protein per milligram of lipid as described (46).

Flux Assays

Chloride flux assays were performed similarly to those previously described (46). DIDS was dissolved at 10 mM in DMSO. DADS (Avocado Research Chemicals) and purified fractions 2, 3, 4, and 5 were dissolved in the vesicle buffer (300 mM KCl, 25 mM Na-citrate, pH 4.5) to make 0.1-20 mM stock solutions; fractions were added to the ClC-ec1-containing vesicles (at various final concentrations, as indicated in the figures). An equal volume of vesicle buffer alone was added to vesicles containing no inhibitor. Intra- and extravesicular solutions were equalized by freezing and thawing the samples four times prior to extrusion through a 400 nm filter. Extravesicular solution was exchanged for low-chloride flux buffer (300 mM K-isethionate, 0.5 mM KCl, 25 mM Na-citrate, pH 4.5) immediately prior to the assay. Flux assays were initiated by the addition of the ionophores valinomycin and FCCP (time 0 in Figure 1, panel b), which allows bulk release of chloride through ClC-ec1. The initial rate of chloride movement was determined by measuring the chloride flux immediately following this addition. The activity (A) is defined as this initial flux minus the initial flux through control vesicles containing no ClC-ec1. Triton X-100 (0.1%) was added at the end of each assay to reveal the total intravesicular chloride concentrations.

For experiments with DIDS, all assays were completed within 2 h (DIDS runs as a single peak on reversed-phase HPLC after 3 h in aqueous solution). For experiments with the hydrolyzed fractions, the vesicles were exposed to each fraction for 1-6 h. Since no significant differences in flux were observed throughout the day, we conclude that the inhibition had reached steady state by the shortest time of coincubation (consistent with inhibition being reversible, such as the case for DIDS (21)).

ClC-0 and ClC-Ka Expression in Xenopus Oocytes

We used a ClC-0 construct in a plasmid derived from the pBluescript vector (47, 48). The plasmid was linearized with FspI and transcribed in vitro using the mMessage mMachine T3 RNA-polymerase transcription kit (Ambion).

The ClC-Ka and Barttin constructs from Dr. T. J. Jentsch’s laboratory were subcloned into psGEM and transcribed using the mMessage mMachine T7 RNA polymerase transcription kit (Ambion). The Y98A mutation was introduced into the Barttin construct because this mutation had previously been shown to increase surface expression on ClC-Ka (49). Site-directed mutagenesis to introduce the N68D mutation into the ClC-Ka gene was done using a PCR based strategy. The entire gene was sequenced to confirm the absence of additional mutations.

Electrophysiology

For patch-clamp recordings, defolliculated Xenopus oocytes were injected with 27.5 nL of ClC-0 RNA at ∼500 ng/μL. Oocytes were incubated at 16 °C for 2-7 days before recordings were obtained. Data were collected from either excised inside-out patches (Figures 4 and 5) or outside-out patches (Figure 6) using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pClamp software. Currents were sampled at 5 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. Recording electrodes were pulled from 100 μL calibrated pipets (VWR) and polished to 300-800 kΩ. Internal and external solutions contained 110 mM NMDG-Cl, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5. Solution switching was accomplished using a 16-channel microfluidic chip (Dynaflow; Cellectricon). This system allowed for the use of small volumes of inhibitors (100 μL). Time courses were measured by holding the current at the resting potential (0 mV) and stepping the voltage every5 s to +50 mV for 50 ms and then to -100 mV for 50 ms. Instantaneous currents after stepping to -100 mV were measured as a function of time, and I/Io was calculated as the current at each time point divided by the initial current.

For two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings, defolliculated Xenopus oocytes were injected with 27.5 nL of a 2:1 mixture of ClC-Ka:Bartin-Y98A RNA at 5-550 ng/μL. Oocytes were incubated at 16 °C for 1-7 days before recordings. Electrodes were pulled to 0.4-1.6 MΩ and filled with 3 M KCl, 1.6 mM EGTA, 5 mM HEPES, pH 6.5. The bath solution contained 90 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES at pH 7.3. Solution changes were done by perfusing the chamber with 4-5 mL of each solution (∼15 times the size of the chamber).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Dr. T. J. Jentsch for providing the clones for the ClC-0, ClC-Ka, and Barttin cDNA. We thank G. Martinez for making the Y98A mutation in Barttin and for subcloning the ClC-Ka and Barttin cDNA into the psGEM vector and M. Gadzinski for technical support in the early stages of this project. We also appreciate the use of Dr. P. B. Harbury’s HPLC. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM070773) and the Lazard Foundation. K.M. was funded by postdoctoral fellowships from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association. A.H. is grateful to Roche, Inc., for a graduate student fellowship award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F, Zdebik AA. Molecular structure and physiological function of chloride channels. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:503–568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartzell C, Qu Z, Putzier I, Artinian L, Chien LT, Cui Y. Looking chloride channels straight in the eye: bestrophins, lipofuscinosis, and retinal degeneration. Physiology (Bethesda) 2005;20:292–302. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00021.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puljak L, Kilic G. Emerging roles of chloride channels in human diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1762:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki M, Morita T, Iwamoto T. Diversity of Cl(-) channels. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:12–24. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5336-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kornak U, Kasper D, Bosl MR, Kaiser E, Schweizer M, Schulz A, Friedrich W, Delling G, Jentsch TJ. Loss of the ClC-7 chloride channel leads to osteopetrosis in mice and man. Cell. 2001;104:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fong P. CLC-K channels: if the drug fits, use it. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:565–566. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iyer R, Iverson TM, Accardi A, Miller C. A biological role for prokaryotic ClC chloride channels. Nature. 2002;419:715–718. doi: 10.1038/nature01000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Accardi A, Miller C. Secondary active transport mediated by a prokaryotic homologue of ClC Cl- channels. Nature. 2004;427:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature02314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheel O, Zdebik AA, Lourdel S, Jentsch TJ. Voltage-dependent electrogenic chloride/proton exchange by endosomal CLC proteins. Nature. 2005;436:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature03860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Picollo A, Pusch M. Chloride/proton antiporter activity of mammalian CLC proteins ClC-4 and ClC-5. Nature. 2005;436:420–423. doi: 10.1038/nature03720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong CM. Interaction of tetraethylammonium ion derivatives with the potassium channels of giant axons. J. Gen. Physiol. 1971;58:413–437. doi: 10.1085/jgp.58.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yellen G, Jurman ME, Abramson T, MacKinnon R. Mutations affecting internal TEA blockade identify the probable pore-forming region of a K+ channel. Science. 1991;251:939–942. doi: 10.1126/science.2000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmgren M, Smith PL, Yellen G. Trapping of organic blockers by closing of voltage-dependent K+ channels: evidence for a trap door mechanism of activation gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 1997;109:527–535. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.5.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fodor AA, Black KD, Zagotta WN. Tetracaine reports a conformational change in the pore of cyclic nucleotidegated channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 1997;110:591–600. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.5.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaoka K, Vogel SM, Seyama I. Na+ channel pharmacology and molecular mechanisms of gating. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006;12:429–442. doi: 10.2174/138161206775474468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hucho F. Toxins as tools in neurochemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liantonio A, Picollo A, Carbonara G, Fracchiolla G, Tortorella P, Loiodice F, Laghezza A, Babini E, Zifarelli G, Pusch M, Camerino DC. Molecular switch for CLC-K Cl- channel block/activation: optimal pharmacophoric requirements towards high-affinity ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:1369–1373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708977105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cabantchik ZI, Greger R. Chemical probes for anion transporters of mammalian cell membranes. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;262:C803–C827. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.4.C803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller C, White MM. A voltage-dependent chloride conductance channel from Torpedo electroplax membrane. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1980;341:534–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb47197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picollo A, Liantonio A, Didonna MP, Elia L, Camerino DC, Pusch M. Molecular determinants of differential pore blocking of kidney CLC-K chloride channels. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:584–589. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matulef K, Maduke M. Side-dependent inhibition of a prokaryotic ClC by DIDS. Biophys. J. 2005;89:1721–1730. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.066522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker I, Sumikawa K, Miledi R. Responses to GABA, glycine and beta-alanine induced in Xenopus oocytes by messenger RNA from chick and rat brain. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B. 1988;233:201–216. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1988.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dutzler R, Campbell EB, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a ClC chloride channel at 3.0 A reveals the molecular basis of anion selectivity. Nature. 2002;415:287–294. doi: 10.1038/415287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dutzler R, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Gating the selectivity filter in ClC chloride channels. Science. 2003;300:108–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1082708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jakobsen P, Horobin RW. Preparation and characterization of 4-acetamido-4′-isothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (SITS) and related stilbene disulfonates. Stain Technol. 1989;64:301–313. doi: 10.3109/10520298909107022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller C, White MM. Dimeric structure of single chloride channels from Torpedo electroplax. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1984;81:2772–2775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.9.2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiemann A, Grunder S, Pusch M, Jentsch TJ. A chloride channel widely expressed in epithelial and non-epithelial cells. Nature. 1992;356:57–60. doi: 10.1038/356057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X, Shimada K, Showalter LA, Weinman SA. Biophysical properties of ClC-3 differentiate it from swelling-activated chloride channels in Chinese hamster ovary-K1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35994–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002712200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mo L, Hellmich HL, Fong P, Wood T, Embesi J, Wills NK. Comparison of amphibian and human ClC-5: similarity of functional properties and inhibition by external pH. J. Membr. Biol. 1999;168:253–264. doi: 10.1007/s002329900514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabantchik ZI, Rothstein A. The nature of the membrane sites controlling anion permeability of human red blood cells as determined by studies with disulfonic stilbene derivatives. J. Membr. Biol. 1972;10:311–330. doi: 10.1007/BF01867863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SC, Price M, Prystowsky MB, Deutsch C. Volume response of quiescent and interleukin 2-stimulated T-lymphocytes to hypotonicity. Am. J. Physiol. 1988;254:C286–C296. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.2.C286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koszela-Piotrowska I, Choma K, Bednarczyk P, Dolowy K, Szewczyk A, Kunz WS, Malekova L, Kominkova V, Ondrias K. Stilbene derivatives inhibit the activity of the inner mitochondrial membrane chloride channels. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2007;12:493–508. doi: 10.2478/s11658-007-0019-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doroshenko P, Neher E. Volume-sensitive chloride conductance in bovine chromaffin cell membrane. J. Physiol. 1992;449:197–218. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furukawa T, Virag L, Sawanobori T, Hiraoka M. Stilbene disulfonates block ATP-sensitive K+ channels in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J. Membr. Biol. 1993;136:289–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00233668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Awqati Q. Proton-translocating ATPases. Annu. Rev. Cell. Biol. 1986;2:179–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.02.110186.001143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nadif Kasri N, Bultynck G, Parys JB, Callewaert G, Missiaen L, De Smedt H. Suramin and disulfonated stilbene derivatives stimulate the Ca2+-induced Ca2+ -release mechanism in A7r5 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;68:241–250. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.013045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Neill ER, Sakowska MM, Laver DR. Regulation of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle by suramin and the disulfonated stilbene derivatives DIDS, DBDS, and DNDS. Biophys. J. 2003;84:1674–1689. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74976-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santos FT, Scofano HM, Barrabin H, Meyer-Fernandes JR, Mignaco JA. A novel role of 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid as an activator of the phosphatase activity catalyzed by plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10552–10558. doi: 10.1021/bi990300x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diakov A, Koch JP, Ducoudret O, Muller-Berger S, Fromter E. The disulfonic stilbene DIDS and the marine poison maitotoxin activate the same two types of endogenous cation conductance in the cell membrane of Xenopus laevis oocytes. Pfluegers Arch. 2001;442:700–708. doi: 10.1007/s004240100593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill AP, Sitsapesan R. DIDS modifies the conductance, gating, and inactivation mechanisms of the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3037–3047. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75644-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stumpf A, Almaca J, Kunzelmann K, Wenners-Epping K, Huber SM, Haberle J, Falk S, Duebbers A, Walte M, Oberleithner H, Schillers H. IADS, a decomposition product of DIDS activates a cation conductance in Xenopus oocytes and human erythrocytes: new compound for the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2006;18:243–252. doi: 10.1159/000097671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuttelkopf AW, van Aalten DM. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:1355–1363. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blaustein RO, Cole PA, Williams C, Miller C. Tethered blockers as molecular “tape measures” for a voltage-gated K+ channel. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:309–311. doi: 10.1038/74076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morin TJ, Kobertz WR. Counting membrane-embedded KCNE beta-subunits in functioning K+ channel complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:1478–1482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710366105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Accardi A, Kolmakova-Partensky L, Williams C, Miller C. Ionic currents mediated by a prokaryotic homologue of CLC Cl- channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2004;123:109–119. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walden M, Accardi A, Wu F, Xu C, Williams C, Miller C. Uncoupling and turnover in a Cl-/H+ exchange transporter. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;129:317–329. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jentsch TJ, Steinmeyer K, Schwarz G. Primary structure of Torpedo marmorata chloride channel isolated by expression cloning in Xenopus oocytes. Nature. 1990;348:510–514. doi: 10.1038/348510a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maduke M, Williams C, Miller C. Formation of CLC-0 chloride channels from separated transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1315–1321. doi: 10.1021/bi972418o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Estevez R, Boettger T, Stein V, Birkenhager R, Otto E, Hildebrandt F, Jentsch TJ. Barttin is a Cl- channel beta-subunit crucial for renal Cl- reabsorption and inner ear K+ secretion. Nature. 2001;414:558–561. doi: 10.1038/35107099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.