Abstract

Fluorochemicals have widespread applications and are released into municipal wastewater treatment plants via domestic wastewater. A field study was conducted at a full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plant to determine the mass flows of selected fluorochemicals. Flow-proportional, 24-h samples of raw influent, primary effluent, trickling filter effluent, secondary effluent, and final effluent and grab samples of primary, thickened, activated, and anaerobically-digested sludge were collected over ten days and analyzed by liquid chromatography electrospray-ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Significant decreases in the mass flows of perfluorohexane sulfonate and perfluorodecanoate occurred during trickling filtration and primary clarification, while activated sludge treatment decreased the mass flow of perfluorohexanoate. Mass flows of the 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonate and perfluorooctanoate were unchanged as a result of wastewater treatment, which indicates that conventional wastewater treatment is not effective for removal of these compounds. A net increase in the mass flows for perfluorooctane and perfluorodecane sulfonates occurred from trickling filtration and activated sludge treatment. Mass flows for perfluoroalkylsulfonamides and perfluorononanoate also increased during activated sludge treatment and are attributed to degradation of precursor molecules.

Introduction

Fluorochemicals have ignited widespread interest due to their ubiquitous presence in the environment, including environmental compartments such as air (1–3), surface waters (4–12), groundwater (13–15), biota (16–20), sediment (21), and nonoccupationally-exposed humans (22–26). The fluorination of organic compounds imparts unique physical and chemical properties, including exceptional thermal and chemical stability, suited to applications where conventional hydrocarbon substances decompose (27). The fluoroalkyl tails are both hydrophobic and oleophobic (i.e. oil-repelling). The distinct physical and chemical properties of fluorochemicals make them valuable constituents in a wide range of industrial and commercial applications, including adhesives, cleaners, coatings, shampoos, electroplating, fire-fighting foams, herbicides, insecticides, polishes, wetting agents, stain repellants for furniture, carpets, and clothing (27).

Fluorochemicals are used in consumer products (27) and, as a result, are found in municipal wastewater (28–32) and sludge (21). Untreated fluorochemicals may thus enter the environment via wastewater effluent, septic discharge or application of sludge to agricultural lands. Occurrence of fluorochemicals was reported in the effluents of six U.S. cities (28), in two European urban effluents (29), and in the influent and effluent of one Iowa City wastewater treatment plant (30). Fluorochemicals were also observed in ten wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) influents and final effluents and, despite similar treatment processes, there were no systematic decreases or increases for the compounds studied in the ten WWTPs (31). Sinclair et al. observed that secondary treatment increased the (dissolved phase only) mass flows of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), perfluorooctanoate (PFOA), perfluorononanoate (PFNA), perfluorodecanoate (PFDA) and perfluoroundecanoate (PFUnDA) in a plant with an industrial influence, while only the mass flow of PFOA increased in a plant with no industrial influence (32). Despite the reported occurrence of fluorochemicals in wastewater and sludge, the distribution and fate of fluorochemicals during each wastewater treatment process, specifically for both the dissolved and sorbed phases, is not well known.

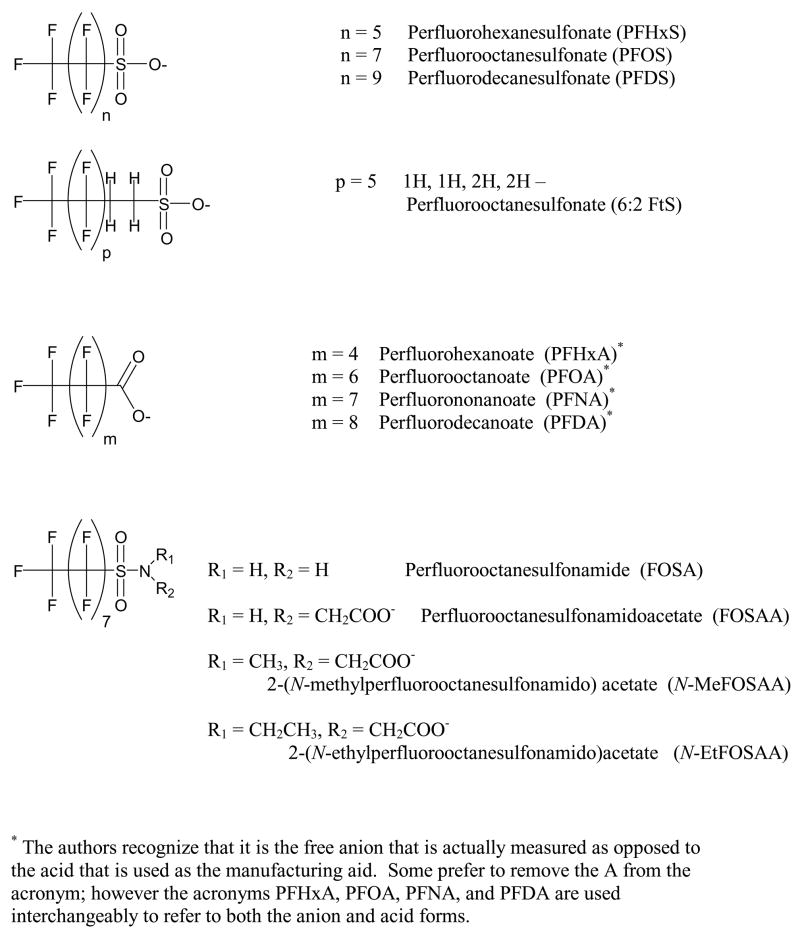

The objective of this study was to determine comprehensive mass flows of the most abundant perfluoroalkyl sulfonates, perfluoroalkyl carboxylates, fluorotelomer sulfonates, and fluoroalkyl sulfonamides (Figure 1) in a municipal WWTP using previously reported analytical methods for fluorochemicals in wastewater (31) and sludge (21). This is the first study that provides an overview of the fate of fluorochemicals in both the dissolved and sorbed phases of wastewater treatment by quantitatively evaluating the behavior of 15 individual fluorochemicals during each step of municipal wastewater treatment. The discharge of fluorochemicals in the form of wastewater and sludge was determined to better understand the role wastewater treatment plays in the release of fluorochemicals to the aqueous and terrestrial environments.

Figure 1.

Fluorochemicals detected in wastewater and sludge.

Experimental Section

Chemicals

The 15 chemicals included in this study include the perfluoroalkyl sulfonates, perfluoroalkyl carboxylates, sulfonamides, and a single fluorotelomer sulfonate. The chemical source and purity are given in Schultz et al. (31) and Higgins et al. (21); the structures and acronyms are given in Figure 1.

Study site

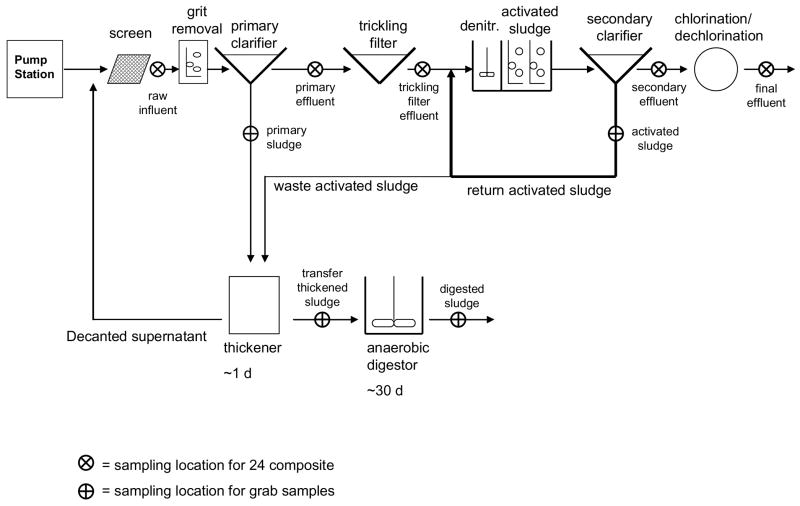

The municipal WWTP selected for this mass flow study is located in the Pacific Northwest, United States, and serves a population of approximately 50,000 people. Raw sewage entering the WWTP is first passed through a screen to remove larger solids (Figure 2). Wastewater then flows to the primary clarifier where solids are removed as primary sludge. Primary effluent enters the trickling filters that are followed by activated-sludge aeration basins. Approximately 99% of the activated sludge that leaves the secondary clarifier is recycled activated sludge (RAS), which has a 6–7 d residence time in this system (Figure 2), while the remaining 1% of activated sludge is sent to the thickener as waste activated sludge (WAS). After activated sludge treatment, the wastewater passes to the secondary clarifier after which it is chlorinated and dechlorinated before being discharging into a river. The overall residence time for the aqueous stream through the WWTP is approximately 8 – 10 h (Figure 2). The primary sludge and the WAS are mixed in a 3:1 (v/v) ratio (primary sludge:WAS) and thickened for one day before the supernatant is decanted and fed back into the raw influent stream. The thickened sludge is passed to the anaerobic digester where it is incubated for 30 days.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the wastewater treatment plant.

Sample collection and preparation

Flow-dependent (e.g. a fixed volume of sample taken every 4 × 105 L of wastewater), 24 h samples of raw influent, primary effluent, trickling filter effluent, secondary effluent, and final effluent were collected over a ten day period in July 2004. During the ten day sampling period, the outside temperature ranged from 12 °C (night) to 41°C (day); no precipitation fell during the sampling period. During the sampling period, grab samples of primary, activated, thickened, and anaerobically-digested sludge were collected four times a day for two of the study days and once on three additional days.

All wastewater and sludge samples were collected and stored in high density polyethylene bottles. Wastewater samples that were analyzed within 48 h upon arrival to the laboratory were kept refrigerated at 4 °C until analysis. Wastewater samples not analyzed within 48 h were stored at −20 °C and thawed to room temperature prior to analysis. Sludge samples were frozen within hours of collection (−15 °C) and were air dried immediately prior to extraction. Particulate matter (suspended solids present in the wastewater samples) was separated from the raw influent and primary effluent by centrifugation and then air dried.

Analytical methods

Direct, large-volume injection was combined with liquid chromatography and electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) to analyze the wastewater samples (31). Each aqueous sample was analyzed in duplicate for this study. Briefly, the precision of the wastewater method, defined by the relative standard deviation (RSD), ranged from 2 to 22% for raw influent and final effluent. The accuracy of the method ranged from 82 to 100% with a standard error of ± 2% for raw influent and final effluent as determined from field-matrix spikes. The limit of quantitation (LOQ) for the fluorochemicals ranged from 0.50 to 0.80 ng/L.

Sludge and particulate-matter samples were extracted using liquid solvent extraction followed by a solid-phase extraction clean-up step and analyzed by LC/MS/MS as described by Higgins et al.(21); solids method precision, as indicated by the RSD, was reported in this study to be <20% for 81% of quantifiable sludge samples. Recoveries of the fluorochemicals from digested and primary sludge was >70% for most analytes. The method detection limits ranged from 0.7 to 2.2 ng/g (dry wt.). During the study, 20% of the sludge samples were analyzed in duplicate. The analytical method for the determination of fluorochemicals in sludge was not validated for perfluorooctanesulfonamide (FOSA), 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H–perfluorooctane sulfonate (6:2 FtS), and perfluorohexanoate (PFHxA), and therefore, sludge concentrations for these fluorochemicals were not determined.

Calculation of Mass Flow

The average mass flow of each fluorochemical was determined by multiplying the average sum of aqueous and particulate-phase concentrations (Table 1) by the average total flow of each treatment unit (Figure 2). The mass of each fluorochemical associated with the RAS was determined by multiplying the average measured activated sludge concentration by the total volume, on a per day basis, in the activated and secondary clarifier units (~2,800,000 L). The RAS mass flows were calculated separately since it is internally recycled between the secondary clarifier and the activated sludge units. Combined standard errors were computed to indicate the uncertainty associated with the calculated mass flow of each fluorochemical. The standard errors accounted for both the error associated with analytical measurements as well as the standard error of the total plant flow, which contributed only 1% to the overall error. Confidence intervals (95%) were subsequently calculated from the combined standard error and the Student’s t value for a two-tailed test with the appropriate degrees of freedom (e.g., number of analytical observations and the ten days of flow data).

Table 1.

Measured concentrations of fluorochemicals in wastewater (dissolved phase) and sludge (sorbed phase).

| Analyte | Raw Influent 26,700 m^3/day | Primary Effluent 26,700 m^3/day | Trickling Filter Effluent 26,700 m^3/day | Secondary Effluent 26,700 m^3/day | Final Effluent 26,700 m^3/day | Primary Sludge 605 m^3/day | Thickened Sludge 113 m ^3/day | Activated Sludge 185 m^3/day | Digested Sludge 113 m^3/day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous concentrations (ng/L) | |||||||||

| PFHxSd | 7.7 (3.8–15) | 5.3 (2.8–8.3) | 1.7 (<0.5–3.8) | 1.6 (nd-3.2) | 1.2 (nd-3.2) | ||||

| PFOSd | 15 (6.9–33) | 18 (8.7–6.1) | 27.0 (22–31) | 21 (12–27) | 24 (15–34) | ||||

| PFDSd | 4.0 (nd-7.5) | 5.1 (1.5–8.2) | 17 (9.7–2.9) | 3.7 (<0.5–10.1) | 8.2 (2.2–15) | ||||

| FOSAAd | NA* | NA* | NA* | NA* | NA* | ||||

| N-MeFOSAAd | NA* | NA* | NA* | NA* | NA* | ||||

| N-EtFOSAAd | NA* | NA* | NA* | NA* | NA* | ||||

| FOSA d | nd | Nd | Nd | 8.1 (nd-24) | 4.6 (nd-17) | ||||

| 6:2FtSd | 8.0 (4.9–13) | 5.4 (nd-9.8) | 5.3 (1.2–2.1) | 4.1 (1.5–5.5) | 9.8 (6.0–20) | ||||

| PFHxA d | 19 (12–29) | 11.9 (7.5–20) | 9.9 (6.2–4.9) | 5.0 (3.3–6.4) | 6.4 (4.6–8.3) | ||||

| PFOAd | 15.0 (9–24) | 11 (4.8–4.4) | 8.7 (4.1–8.8) | 11 (6.5–16) | 11 (8.2–15) | ||||

| PFNAd | Nd | Nd | nd | 6.6 (2.8–13) | 3.4 (1.5–5.9) | ||||

| PFDAd | 5.6 (2.7–10) | 6.2 (1.1–17) | 3.3 (1.4–5.4) | 2.7 (0.8–7.5) | 2.3 (0.6–5.1) | ||||

| PFUnAd | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| PFDoAd | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| PFTAd | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Particulate concentrations (ng/g) | |||||||||

| PFHxSp | <3 | <3 | NS | NS | NS | 3.4 (nd-12) | nd | nd | |

| PFOSp | 5.3 (2.5–8.7) | 8.0 (2.7–13) | NS | NS | NS | 53 (18–3.8) | 42 (20–18) | 43 (31–55) | |

| PFDSp | 14 (8.5–19) | 49 (19–88) | NS | NS | NS | 19.4 (14–2.9) | 62 (57–71) | 130 (94–140) | |

| FOSAAp | 3.4 (<3–3.7) | 6.2 (1.9–14) | NS | NS | NS | <3 (<3–3.4) | 6.9 (6.2–7.6) | 19 (14–23) | |

| N-MeFOSAAp | <5 | 11 (4.6–20) | NS | NS | NS | 6.3 (5.2–8.9) | 41 (35–52) | 140 (99–61) | |

| N-EtFOSAAp | 7.9 (6.5–10) | 33 (12–53) | NS | NS | NS | 20 (15–5.8) | 48 (43–52) | 120 (90–140) | |

| PFOAp | <5 | <5 | NS | NS | NS | 7.1 (<6–12) | <6 | 6.7 (<6–8.2) | |

| PFNA p | 5.3 (<2.6–5.3) | <3 | NS | NS | NS | 4.2 (nd-10) | Nd | 3.8 (3.1–4.9) | |

| PFDAp | <1 | 2.7 (<1–4.5) | NS | NS | NS | 2.8 (1.6–3.9) | 3.9 (3.4–5.3) | 9.1 (7.2–0.8) | |

| PFUnAp | nd | nd | NS | NS | NS | 2.6 (2.0–4.2) | 4.4 (3.9–5.0) | 9.2 (7.7–0.5) | |

| PFDoAp | nd | Nd | NS | NS | NS | 1.5 (1.3–1.6) | 4.3 (4.1–5.1) | 7.1 (6.1–7.8) | |

| PFTAp | nd | Nd | NS | NS | NS | nd | 1.2 (0.9–1.3) | <3 | |

dissolved phase

particulate phase

NA = not analyzed

NA* = not analyzed (effective detection limit > 25ng/L)

nd = not detected

NS = no (particulate phase) sample obtained

single sample analyzed

one of five samples collected was at a detectable level

Results and Discussion

Mass flows of Perfluoroalkyl Sulfonates

Perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), PFOS, perfluorodecane sulfonate (PFDS) were detected in both wastewater and sludge (Table 1). Perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS) was not detected during this study; however, this compound was previously measured in this and other WWTPs (31).

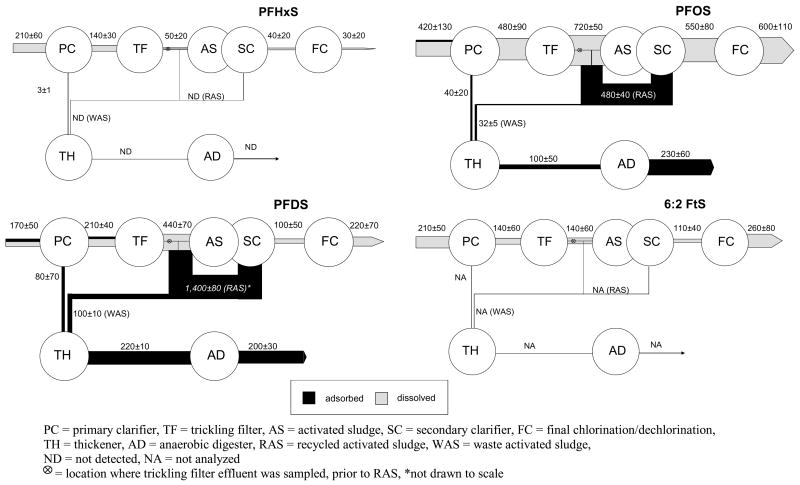

PFHxS entering the WWTP is entirely in the aqueous phase and no significant removal occurs during primary clarification, which is consistent with the small mass flow (3 mg/d) of PFHxS associated with primary sludge (Figure 3). The 65% nominal reduction in PFHxS mass flow during trickling filtration cannot be attributed to volatilization or biodegradation since perfluoroalkyl sulfonates are sparingly volatile (33) and not susceptible to biodegradation (34). While it might be argued that there could be removal by sorption onto the biofilm of the trickling filter, the higher molecular weight sulfonates, including PFOS and PFDS, do not show the same behavior (Figure 3). No further reduction in mass flow occurs during activated sludge or any subsequent treatment stage before discharge (Figure 3). No PFHxS was detected in the recycled- or waste-activated sludge, thickened sludge, or anaerobically-digested sludge (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Average mass flows ± 95% CI (mg/day) for perfluoroalkylsulfonates and the 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonate.

Of the PFOS entering as raw influent, approximately 10% is transferred to primary sludge, which is then subjected to anaerobic sludge digestion (Figure 3). Within the error of the measurements, the mass flows associated with the sum of the primary sludge and primary effluent are in good agreement with that of the raw influent (Figure 3). Moreover, the sum of the primary sludge and waste-activated sludge (WAS) mass flows for PFOS (and PFDS) are in good agreement with that associated with the thickened sludge, which indicates that there is no net formation or decrease of PFOS during the one day residence time in the thickener (Figure 3). The apparent increase in mass flow associated with the anaerobically-digested sludge when compared to the thickened sludge may be due to differences in residence time of the thickened sludge (1 day) compared to the 30 day residence time of sludge in the anaerobic-sludge digester and, as such, cannot be compared directly. Alternatively, it is possible that the mass flow of PFOS varies significantly over a 30 day period or that anaerobic degradation of precursors results in the formation of PFOS during the 30 day residence time of the sludge digester.

The average mass flow of PFOS increases significantly across the trickling filter (Figure 3). The cause for this increase is not known but was consistently observed on each of the ten days of the study; it may possibly be due to biodegradation of precursors. The sorption of PFOS onto the activated sludge accounts, in part, for the apparent decrease of PFOS in the dissolved phase mass flow during activated sludge treatment, thus resulting in the transfer of ~30 mg/d PFOS to the sludge thickener (Figure 3). The mass of PFOS associated with WAS represents the net production of PFOS in this WWTP. The transfer of PFOS to RAS offsets the apparent increase in PFOS mass flow resulting from trickling filtration and it allows the mass flow of PFOS in wastewater to appear unchanged from the primary clarifier to final clarifier. Overall, of the PFOS exiting the plant, 2.5 times more mass per day exits the plant in the final effluent and than in the anaerobically-digested sludge.

When compared to PFOS, the greater affinity of PFDS for suspended solids is evident from the fact that 35–38% of the PFDS mass flow associated with raw influent and primary effluent is associated with particulate matter (Table 1). Approximately 50% of the average influent mass flow of PFDS is transferred to primary sludge (Figure 3). The average mass flow of PFDS increased 2 fold across the trickling filter, which is similar to the behavior of PFOS, and also like PFOS, the cause for the increases is not known (Figure 3). The RAS acts as a sink for PFDS (1,400±80 mg/d) and is likely responsible for the apparent decrease in PFDS mass flow across the activated sludge aeration basins. Therefore, even though mass flow of PFDS associated with the final effluent and primary clarifier effluent is not statistically different at the 95% CI, there is a net production of PFDS that is transferred via WAS (~100 mg/d) to the sludge digesters. Virtually nothing is known about potential precursors of PFDS to explain the production of PFDS and little is also known about its use and occurrence (21,31).

The combined mass flows for primary sludge and WAS is equal to that of the thickened sludge as well as the anaerobically-digested sludge mass flows, which indicates that there is no net increase or decrease in PFDS resulting from anaerobic sludge treatment. This finding is consistent with reports that PFOS, and likely PFDS, are not transformed under anaerobic conditions (35). Of the mass flow of PFDS exiting the plant, 50% exits as final effluent and 50% exists as anaerobically-digested sludge.

Among the perfluoroalkylsulfonate class of fluorochemicals, the effect of the perfluoroalkyl group is evident with the increasing percent of PFHxS, PFOS, and PFDS associated with the particulate phase entering the WWTP and exiting the WWTP as anerobically-digested sludge. Transfer to sludge increases with increasing chain length, and this behavior is consistent with the increased sediment-water partition coefficients observed with increasing perfluoroalkyl chain length (36). Although this conventional WWTP did reduce the mass flow of PFHxS, the mass flows of PFOS and PFDS were increased during activated sludge treatment. Despite the fact that production of PFOS and other related perfluorooctane sulfonylfluoride-based chemicals ceased in 2002 (37); the results of this study and others (21, 30–32) indicate that the chemicals still exist in the marketplace and are actively being used.

6:2 Telomer Sulfonate

Only one fluorotelomer sulfonate, 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H–perfluorooctane sulfonate (6:2 FtS), was quantified in wastewater (Figure 1). The mass flow of the 6:2 FtS that entered the plant in the aqueous phase was not affected significantly during any treatment stage (Figure 3). No measurements of particulate or sludge concentrations of 6:2 FtS were made due to analytical limitations. However, because the raw influent and primary effluent are the same at the 95% CI, it is likely that only a small fraction, if any, is transferred to sludge. Given this observation, conventional wastewater treatment appears to be ineffective in removing the 6:2 FtS from municipal wastewater.

Perfluoroalkylsulfonamido-based fluorochemicals

Three members of the sulfonamide-based class of fluorochemicals (Figure 1) were quantified in sludge including 2-(N-ethylperfluorooctanesulfonamido) acetic acid (N-EtFOSAA), 2-(N-methylperfluorooctanesulfonamido) acetic acid (N-MeFOSAA), and perfluorooctanesulfonamidoacetate (FOSAA). A fourth sulfonamide precursor, FOSA, was determined only in aqueous samples (Table 1). The solids analytical method was not validated for FOSA (21). Analytical limitations prohibited measurements of N-EtFOSAA, N-MeFOSAA, and FOSAA in wastewater with signal-to-noise ratios (used to estimate limits of detection and quantitation) of more than one to five when these analytes were spiked into wastewater at 25 ng/L, which is at the upper end for the range of concentrations observed for all fluorochemical analytes measured in this study. As a result, the concentrations of these analytes were not determined for wastewater. Recent data indicate, however, that N-EtFOSAA and N-MeFOSAA are significantly more sorptive than PFOS (ΔlogKoc > 0.54) (36), suggesting that if these chemicals are present in wastewater, they are likely sorbed to suspended particles. Thus, any contributions of the dissolved phase to the mass flows of these chemicals are likely minimal.

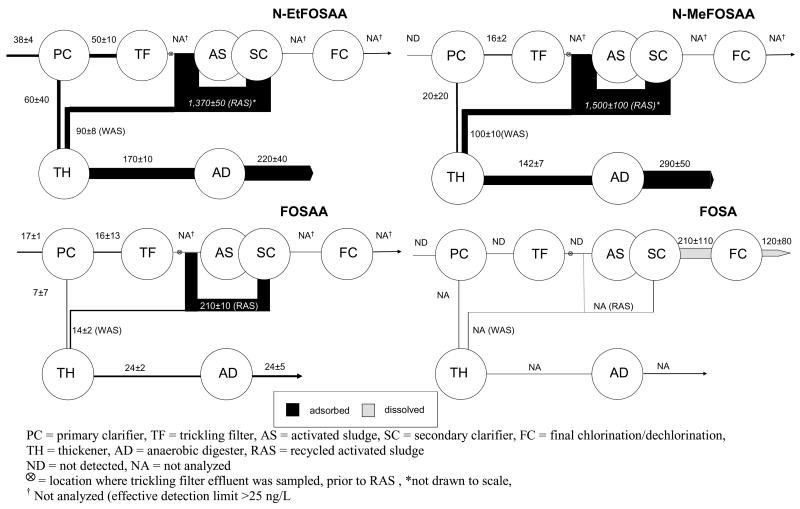

N-EtFOSAA was observed on the suspended solids of the raw influent, primary effluent and during all stages of sludge treatment (Table 1 and Figure 4). N-EtFOSAA is derived either from the use of commercial products (e.g., 3M Company’s FC-129, which was included in the voluntary cessation of production) or as a transformation product of N-ethyl perfluorooctanesulfonamido ethanol (N-EtFOSE) (34). If the N-EtFOSAA observed in the influent results from the transformation of N-EtFOSE, then biodegradation must be occurring during the transit of wastewater from the site of origin to the WWTP. The mass flow associated with primary sludge (60±40 mg/d) and WAS (90±8 mg/d) is not significantly different from that associated with the thickened sludge (170±10 mg/d) (Figure 4). Likewise, the mass flow associated with anaerobically-digested sludge is in good agreement with the mass flow associated with thickened sludge (Figure 3), which indicates that there is no net increase or decrease during anaerobic sludge treatment. However, there is an overall increase in the N-EtFOSAA mass flow exiting the plant as sludge (220±40 mg/d) relative to that entering as either raw influent (38±4 mg/d) or primary effluent (50±10 mg/d). The apparent production occurs during activated sludge treatment, where precursors may be transformed under aerobic conditions and N-EtFOSAA is formed and transferred via RAS and WAS to the sludge digester.

Figure 4.

Average mass flows ± 95% CI (mg/day) for perfluoroalkylsulfonamides.

N-MeFOSAA, which is thought to occur exclusively as a transformation product of N-methyl perfluorooctanesulfonamido ethanol (N-MeFOSE), similar to the degradation pathway of N-EtFOSE to N-EtFOSAA (34), was not detected in the particulate phase of the raw influent (Table 1). Although not detected in the raw influent, N-MeFOSAA was detected in primary sludge and in the suspended solids of primary effluent, which suggests that its precursors are present in the WWTP influent (Figure 4) and are biodegrading to form N-MeFOSAA. In a manner analogous to that of N-EtFOSAA, there was a significant increase in the mass flow associated with the RAS (1500±100 mg/d), which indicates that N-MeFOSAA is also formed during activated sludge treatment. The combined mass flow of N-MeFOSAA associated with WAS and that of primary sludge is in good agreement with that associated with the thickened sludge (Figure 4). However unlike N-EtFOSAA, there was a statistical difference at the 95% CI between the mass flow of N-MeFOSAA through the thickener (142±7 mg/d) as compared to the mass flow through the anaerobic digester (290±50 mg/d), which indicates the possible presence and degradation of N-MeFOSAA precursors under anaerobic conditions.

FOSAA, which is known only to occur as a transformation product of either N-EtFOSE or N-MeFOSE or their subsequent transformation products (i.e., N-EtFOSAA, and N-MeFOSAA) (34), was detected on the suspended solids of the raw influent and primary effluent and in all primary, activated, and anaerobically-digested sludge (Table 1). Net production of FOSAA appears to occur during activated sludge treatment where the mass associated with RAS was 210±10 mg/d and 14±2 mg/d is transferred as WAS to the sludge digester.

FOSA was quantified only in aqueous samples, and it was detected only in secondary and final effluents (Table 1 and Figure 4). The production of FOSA after the activated sludge aeration basins is consistent with the observed formation of N-EtFOSAA, N-MeFOSAA, and FOSAA during activated sludge treatment and clearly indicates the presence of biodegradable precursors in the wastewater of this WWTP. Further research is needed to identify the precursor compounds in wastewater and sludge to verify their degradation to explain the apparent increases in the mass flow of N-EtFOSAA, N-MeFOSAA, FOSAA, and FOSA during activated sludge treatment.

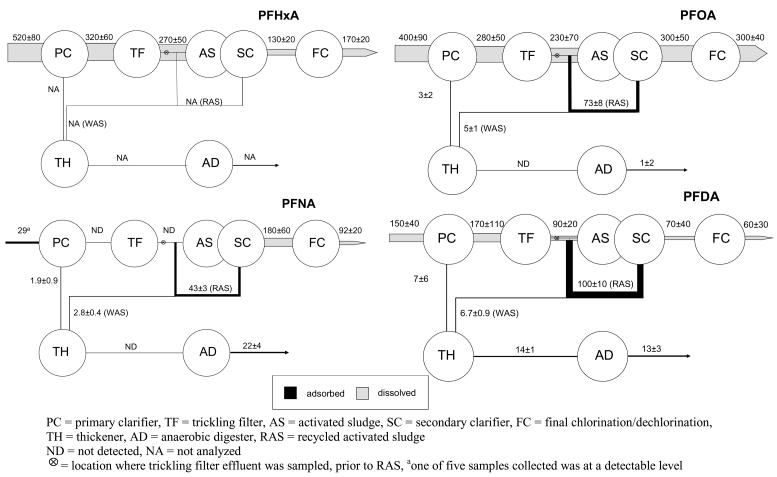

Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylates

PFHxA, PFOA, PFNA, and PFDA were quantified in wastewater while PFUnA, perfluorododecanoate (PFDoA), and perfluorotetradecanoate (PFTA) were detected only in sludge (Table 1). Perfluoroheptanoate (PFHpA) was analyzed for, but not detected, during this study; however, this compound was previously measured in this and other WWTPs (31).

PFHxA was determined only for the dissolved phases in this study as the analytical method for sludge was not valid for PFHxA (21). The mass flow of PFHxA decreased significantly during primary clarification and again during activated sludge treatment. This apparent decrease may be due to partitioning onto primary sludge and RAS because volatilization and biodegradation are not likely with perfluoroalkyl carboxylates (38) (Figure 5). However, as will be discussed, losses of a longer chain analog, PFOA, were not observed for these treatment steps, as would be expected given the greater sorptive potential of PFOA. Overall there is a 3-fold reduction in the PFHxA mass flow during treatment.

Figure 5.

Average mass flows ± 95% CI (mg/day) for perfluoroalkylcarboxylates.

The mass flow of PFOA in the raw influent (400±80 mg/d) and the final effluent (300±40 mg/d) are equivalent at the 95% CI with less than 0.1 % (3±2 mg/d) removed onto primary sludge (Figure 5). PFOA is present on RAS (73±8 mg/d) and WAS (5±1 mg/d). Although PFOA is detected on primary sludge and WAS, it was below detection in the thickened sludge and only one eighth of the combined mass flow in WAS and primary sludge was accounted for in the anaerobically-digested sludge. Overall, there was no significant increase or decrease in mass flow of PFOA during wastewater treatment. Previous work found that in 8 out of 10 WWTPs sampled, perfluoroalkyl carboxylate effluent concentrations, including PFOA, were significantly higher than the influent levels (31). The WWTP in which the current study was conducted was one of the two WWTPs that did not show an increase in perfluoroalkylcarboxylates (31). Sinclair et al. (32) found that the mass flow of PFOA increased significantly and attributed this increase to the presence and biodegradation of fluorotelomer alcohols. It is possible that fluorotelomer alcohols or other precursor compounds that form PFOA are not present at the WWTP sampled for the current study.

PFNA was detected only in the particulate phase in only one of the five grab samples of raw influent and only for three out of five grab samples of primary sludge. Although intermittent, the mass flow of PFNA that enters the WWTP on the particulate phase appears to be routed entirely to the sludge digesters because PFNA was not detected in either primary effluent or trickling filter effluents (Table 1; Figure 5). However, there is measurable mass flow of PFNA associated with both the secondary and final clarifier effluent, which indicates that PFNA is being formed under the aerobic conditions in the activated sludge aeration basins. This finding is consistent with that of the Sinclair et al. study in which they found a statistically-significant increase in the PFNA mass flows for two WWTPs (32). Formation of PFNA during activated sludge treatment is supported by the measurable mass flow of PFNA associated with RAS (and WAS) and may result from the aerobic degradation of precursors; however, specific precursors of PFNA have yet to be reported. Likewise, there appears to be significant formation of PFNA in the anaerobic digester (Figure 5). Ultimately, there is a 4-fold increase in the mass flow of PFNA exiting this plant as final effluent and anaerobically-digested sludge over what is entering in the raw influent. These results indicate that formation of PFNA from precursors is a significant process in this WWTP and that WWTPs can act as point sources of PFNA.

There was a nominal 60% decrease in PFDA mass flow between the raw influent (150±40 mg/d) and the final effluent (60±30 mg/d) (Figure 5). The largest reduction in mass flow occurred during the trickling filter stage and may be attributed to sorption onto the biofilm of the trickling filter; however, PFHxA and PFOA do not exhibit the same behavior. No significant reduction in PFDA mass flow between raw influent and primary effluent resulted from primary settling with only 7±6 mg/d (~5%) transferred onto primary sludge. The net removal of PFDA via WAS does not reduce the mass flow during activated sludge treatment. The combined primary sludge and WAS is equivalent to the thickened and anaerobically-digested sludge, which indicates there are no processes that affect PFDA during anaerobic sludge digestion.

Longer chained perfluoroalkylcarboxylates including PFUnA, PFDoA, and PFTA were also quantified in this WWTP but only on primary sludge, WAS/RAS, thickened sludge, and digested sludge (Table 1); however, a previous study has reported the presence of PFUnA in the dissolved phase of a WWTP that has significant input from industry (32). Only PFDoA was detected on the suspended solids of the primary effluent (data not shown). The mass flows through the sludge thickener and anaerobic-sludge digester were less than 2 mg/d, which is low in comparison to the other fluorochemicals studied (data not shown). The lower concentrations (and mass flows) of these higher homolog perfluoroalkyl carboxylates is consistent with lower and more variable concentrations observed for other digested sewage sludges and sediments (21).

There were no discernable trends observed for the perfluoroalkylcarboxylate class of fluorochemicals at this WWTP. A decrease in the net mass flows of PFHxA and PFDA was observed; however PFHxA was significantly reduced during primary clarification and activated sludge treatments, whereas the decrease in mass flow of PFDA occurred during trickling filtration. The mass flow of PFOA remained unchanged during wastewater treatment, which indicates that the conventional treatment stages of this WWTP are ineffective for removing PFOA from wastewater. The mass flow of PFNA was found to significantly increase during both aerobic and anaerobic treatment stages, suggesting degradation of precursor compounds.

Overall Observations

Of the perfluoroalkylsulfonates studied, PFOS and PFDS showed an overall increase in their mass flows throughout the plant, with both exhibiting increased mass flows during trickling filtration. All four perfluoroalkylsulfonamides demonstrated increased mass flows, most likely resulting from degradation of precursors during the activated sludge process. There were no recognizable trends in mass flows for the perfluoroalkylcarboxylate family. The most notable observations for this class were the apparent ineffectiveness of conventional treatment in regards to PFOA, and the increases in mass flows of PFNA resulting from both aerobic and anaerobic treatments. Further research is needed to verify that precursors, such as N-EtFOSE, N-MeFOSE, or fluorotelomer olefins, are present in wastewater and sludge and that the kinetics of degradation are sufficiently fast to account for the observed increases in fluorochemical mass flows.

Acknowledgments

The authors thankfully recognize financial support in part by a grant (R-82902501-0) from the National Center for Environmental Research (NCER) STAR Program, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grants 0201955 and 0216458, and in part by a grant (P30 ES00210) from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and the UPS Visiting Scholar program through Stanford University. The authors are also indebted to the 3M Company for authentic standards.

Footnotes

Mass flows of selected fluorochemicals are determined during each stage of wastewater and sludge treatment in a field study conducted at a municipal plant.

Literature Cited

- 1.Martin JW, Muir DCG, Moddy CA, Ellis DA, Kwan WC, Solomon KR, Mabury SA. Collection of airborne fluorinated organics and analysis by gas chromatography/chemical ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2002;74:584–590. doi: 10.1021/ac015630d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stock NL, Lau FK, Ellis DA, Martin JW, Muir DCG, Mabury SA. Polyfluorinated telomer alcohols and sulfonamides in the worth American troposphere. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:991–996. doi: 10.1021/es034644t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoeib M, Harner T, Ikonomou M, Kannan K. Indoor and outdoor air concentrations and phase partitioning of perfluoroalkyl sulfonamides and polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:1313–1320. doi: 10.1021/es0305555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moody CA, Kwan WC, Martin JW, Muir DCG, Mabury SA. Determination of perfluorinated surfactants in surface water samples by two independent analytical techniques: liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry and 19F NMR. Anal Chem. 2001;73:2200–2206. doi: 10.1021/ac0100648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moody CA, Martin JW, Kwan WC, Muir DCG, Mabury SA. Monitoring perfluorinated surfactants in biota and surface waters following an accidental release of fire-fighting foam into Etobicoke creek. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36:545–551. doi: 10.1021/es011001+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen KJ, Johnson H, Eldridge J, Butenhoff J, Dick L. Quantitative characterization of trace levels of PFOS and PFOA in the Tennessee River. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36:1681–1685. doi: 10.1021/es010780r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takino M, Daishima S, Nakahara T. Determination of perfluorooctane sulfonate in river water by liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure photoionization mass spectrometry by automated on-line extraction using turbulent flow chromatography. Rapid Com Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:383–390. doi: 10.1002/rcm.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taniyasu S, Kannan K, Horii Y, Hanari N, Yamashita N. A survey of perfluorooctane sulfonate and related perfluorinated organic compounds in water, fish, birds, and humans from Japan. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37:2634–2639. doi: 10.1021/es0303440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito N, Harada K, Inoue K, Sasaki K, Yoshinaga T, Koizumi A. Perfluorooctanoate and perfluorooctane sulfonate concentrations in surface water in Japan. J Occup Health. 2004;46:49–59. doi: 10.1539/joh.46.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.So MK, Taniyasu S, Yamashita N, Giesy JP, Zheng J, Fang Z, Im SH, Lam PKS. Perfluorinated compounds in coastal waters of Hong Kong, South China, and Korea. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:4056–4063. doi: 10.1021/es049441z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boulanger B, Vargo J, Schnoor J, Hornbuckle K. Detection of perfluorooctane surfactants in Great Lakes water. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:4064–4070. doi: 10.1021/es0496975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamashita N, Kannan K, Taniyasu S, Horii Y, Okazawa T, Petrick G, Gamo T. Analysis of perfluorinated acids at parts-per-quadrillion levels in seawater using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:5522–5528. doi: 10.1021/es0492541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moody CA, Field JA. Determination of perfluorocarboxylates in groundwater impacted by fire-fighting activity. Environ Sci Technol. 1999;33:2800–2806. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moody CA, Hebert GN, Strauss SH, Field JA. Occurrence of perfluorooctanesulfonate and other perfluorinated surfactants in groundwater at a fire-training area at Wurtsmith Air Force Base. J Environ Monitor. 2003;5:341–345. doi: 10.1039/b212497a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz MM, Barofsky D, Field JA. Quantitative determination of fluorotelomer sulfonates in groundwater by LC MS/MS. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:1828–1835. doi: 10.1021/es035031j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kannan K, Newsted J, Halbrook RS, Giesy J. Perfluoroctanesulfonate and related fluorinated hydrocarbons in mink and river otters from the United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36:2566–2571. doi: 10.1021/es0205028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kannan K, Koistinen J, Beckman K, Evans T, Gorzelany JF, Hansen KJ, Jones PD, Helle E, Nyman M, Giesy JP. Accumulation of perfluorooctane sulfonate in marine mammals. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:1593–1598. doi: 10.1021/es001873w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kannan K, Hansen KJ, Wade TL, Giesy JP. Perfluorooctane sulfonate in oysters, Crassostrea virginica, from the Gulf of Mexico and the Chesapeake Bay, USA. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2002;42:313–318. doi: 10.1007/s00244-001-0003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannan K, Franson JC, Bowerman WW, Hansen KJ, Jones PD, Giesy JP. Perfluorooctane sulfonate in fish-eating water birds including bald eagles and albatrosses. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:3065–3070. doi: 10.1021/es001935i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van De Vijver KI, Hoff P, Das K, Brasseur S, Van Dongen W, Esmans E, Reijnders P, Blust R, De Coen W. Tissure distribution of perfluorinated chemicals in harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) from the Dutch Wadden Sea. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:6978–6984. doi: 10.1021/es050942+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins C, Field J, Criddle C, Luthy R. Quantitative determination of perfluorochemicals in sediments and domestic sludge. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:3946–3956. doi: 10.1021/es048245p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansen KJ, Clemen LA, Ellefson ME, Johnson HO. Compound-specific, quantitative characterization of organic fluorochemicals in biological matrices. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:766–770. doi: 10.1021/es001489z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen GW, Church TR, Miller JP, Burris JM, Hansen KJ, Lundberg JK, Armitage JB, Herron RM, Medhdizadehkashi Z, Nobiletti JB, O’Neill EM, Mandel JH, Zobel LR. Perfluorooctanesulfonate and other fluorochemicals in the serum of American red cross adult blood donors. Environ Health Perspec. 2003;111:1892–1901. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olsen GW, Church TR, Larson EB, van Belle G, Lundberg JK, Hansen KJ, Burris JM, Mandel JH, Zobel LR. Serum concentrations of perfluorooctanesulfonate and other fluorochemicals in an elderly population from Seattle, Washington. Chemosphere. 2004;54:1599–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuklenyik Z, Reich JA, Tully JS, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Automated solid-phase-extraction and measurement of perfluorinated organic acids and amides in human serum and milk. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38 doi: 10.1021/es040332u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kubwabo C, Vais N, Benoit FM. A pilot study on the determination of perfluorooctanesulfonate and other perfluorinated compounds in blood of Canadians. J Environ Monit. 2004;6:540–545. doi: 10.1039/b314085g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kissa E. Fluorinated Surfactants and Repellants. 2. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.3M Company. Executive Summary: Environmental Monitoring-Multi-City, Sludge, Sediment, POTW Effluentand Landfill Leachate Samples. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Docket AR226-1030a; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alzaga R, Bayona JM. Determination of perfluorocarboxylic acids in aqueous matrices by ion-pair solid-phase microextraction-in-port derivitization-gas chromatography-negative ion chemical ionization mass spectrometry. J Chrom A. 2004;1042:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boulanger B, Vargo JD, Schnoor JL, Hornbuckle KC. Evaluation of perfluorooctane surfactants in a wastewater treatment system and in a commercial surface protection product. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:5524–5530. doi: 10.1021/es050213u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schultz MM, Barofsky D, Field J. Quantitative determination of fluorinated alkyl substances in municipal wastewater by large-volume-injection LC/MS/MS. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:289–295. doi: 10.1021/es051381p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinclair E, Kannan K. Mass loading and fate of perfluoroalkyl surfactants in wastewater treatment plants. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:1408–1414. doi: 10.1021/es051798v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Determination of the vapor pressure of PFOS using the spinning rotor gauge method. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Docket AR 226-0048; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lange CC. The aerobic biodegradation of N-EtFOSE alcohol by the microbial activity present in municipal wastewater treatment sludge. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Docket AR 226-1030a078; 2000. 3M Environmental Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics Risk Assessment Division. Sulfonated perfluorochemicals in the environment: sources, dispersion, fate, and effects. U.S. Environmental Agency Docket AR226-0550; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins CP, Luthy RG. Sorption of perfluorinated surfactants on sediments. doi: 10.1021/es061000n. Submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weppner WA. Phase-out plan for POSF-based products. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Docket AR226-0600; 2000. 3M Company. [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics Risk Assessment Division. Revised draft hazard assessment of perfluorooctanoic acid and its salts. U.S. Environmental Agency Docket AR226-1136; 2002. [Google Scholar]