Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are ∼22-nucleotide RNAs that can pair to sites within messenger RNAs to specify posttranscriptional repression of these messages. Aberrant miRNA expression can contribute to tumorigenesis, but which of the many miRNA-target relationships are relevant to this process has been unclear. Here, we report that chromosomal translocations previously associated with human tumors disrupt repression of High Mobility Group A2 (Hmga2) by let-7 miRNA. This disrupted repression promotes anchorage-independent growth, a characteristic of oncogenic transformation. Thus, losing miRNA-directed repression of an oncogene provides a mechanism for tumorigenesis, and disrupting a single miRNA-target interaction can produce an observable phenotype in mammalian cells.

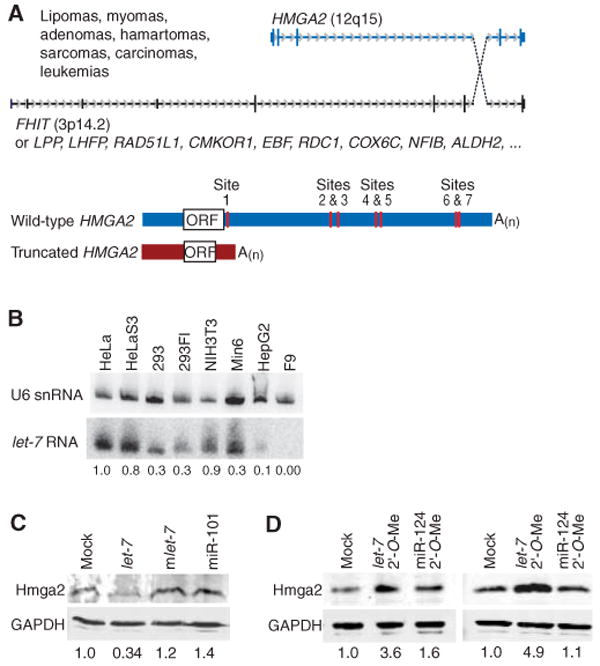

Hmga2 codes for a small, nonhistone, chromatin-associated protein that has no intrinsic transcriptional activity but can modulate transcription by altering the chromatin architecture (1, 2). Hmga2 is primarily expressed in undifferentiated proliferating cells during embryogenesis and in a wide variety of benign and malignant tumors (3–6). In many of these tumors, a chromosomal translocation at 12q15 truncates the human HMGA2 open reading frame (ORF), typically retaining the three DNA-binding domains of HMGA2 while replacing the spacer and the acidic domain at the C terminus by any of a wide variety of ectopic sequences (3–5, 7–10) (SOM text) (Fig. 1A). The loss of the C-terminal region is nearly always presumed to be the cause of oncogenic transformation. However, the translocations also replace the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR), and large fragments of the Hmga2 3′ UTR confer repression to luciferase reporters, which has led to the idea that transformation might be caused by the loss of repressive elements in the UTRs (11). Indeed, chromosomal rearrangements in some tumors leave the ORF intact but disrupt the 3′ UTR, and this is associated with over-expression of the wild-type Hmga2 protein (3,4, 10). Moreover, transgenic mice overexpressing wild-type Hmga2 have similar phenotypes to those expressing the truncated protein; both develop abdominal lipomatosis, then lymphomas, pituitary adenomas, and lung adenomas (2, 12, 13).

Fig. 1.

Chromosomal translocations involving HMGA2, and the influence of let-7 on protein expression. (A) Translocations involving HMGA2 and numerous translocation partners (3–10) (SOM text). These translocations generate a truncated HMGA2 mRNA lacking the let-7 complementary sites of the wild-type mRNA and are associated with the indicated tumors. In its 3′ UTR, human HMGA2 has seven let-7 complementary sites, all of which are conserved in the mouse, rat, dog, and chicken (14). A(n), polyadenylate tail. (B) RNA blot detecting let-7 RNA in different cell lines. The blot was reprobed for U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA), and let-7 signal normalized to that of U6 is indicated. (C) Western blot monitoring endogenous Hmga2 48 hours after transfection of F9 cells with the indicated miRNA duplex. The blot was also probed for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and the normalized Hmga2 signal is indicated. (D) Western blot monitoring endogenous Hmga2 at 24 (left) and 48 (right) hours after transfection of NIH3T3 cells with the indicated 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotide (2′-O-Me). The blot was probed also for GAPDH, and the normalized Hmga2 signal is indicated.

The Hmga2 3′ UTR has seven conserved sites complementary to the let-7 RNA (14), a miRNA expressed in later stages of animal development (15), leading us to suspect that disrupting let-7 regulation of Hmga2 might lead to oncogenic transformation. Consistent with this idea, introducing let-7 RNA repressed Hmga2 in F9 cells (Fig. 1C), an undifferentiated embryonic carcinoma cell line that does not express detectable let-7 RNA (Fig. 1B). Moreover, introducing a 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotide (16, 17) complementary to let-7 RNA enhanced Hmga2 in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 1D), a cell line that naturally expresses let-7 (Fig. 1B). These effects were specific in that they did not occur with non-cognate miRNAs (mlet-7 and miR-101, Fig. 1C) or a noncognate inhibitor (miR-124 2′-O-Me, Fig. 1D).

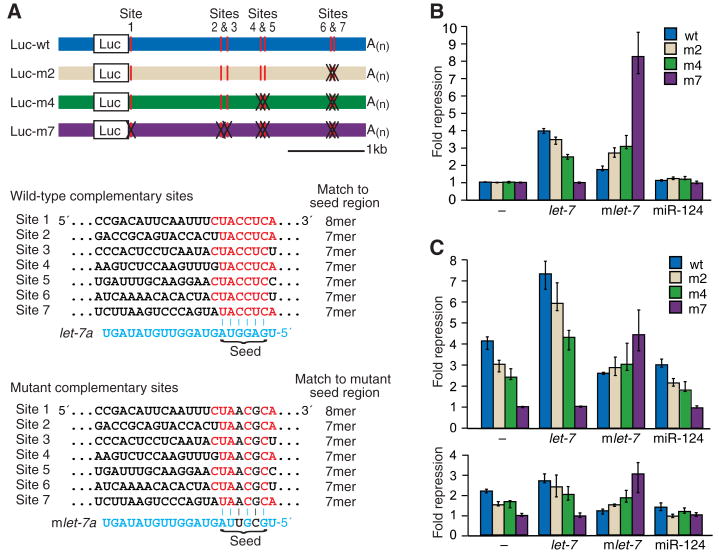

To test whether let-7 directly targets the Hmga2 3′ UTR, we constructed reporters with the wild-type 3′ UTR (Luc-wt) and the UTR with point mutations disrupting all seven sites (Luc-m7), the four distal sites (Luc-m4), or the two most distal sites (Luc-m2) (Fig. 2A). In F9 cells, the degree of repression corresponded to the number of intact sites and depended on cotransfection of the let-7 miRNA, whereas cotransfection of an unrelated miRNA had little effect (miR-124, Fig. 2B). The repression profile inverted when the let-7 miRNA was replaced with a mutant miRNA, mlet-7 (Fig. 2B), which was designed to recognize the mutant sites instead of the wild-type sites (Fig. 2A). This rescue of repression with compensatory changes in the miRNA confirmed targeting specificity and the importance of direct pairing between the sites and the miRNA.

Fig. 2.

Luciferase reporter assays showing the influence of miRNA-target pairing. (A) Design of Luciferase constructs. The 3′ UTR of murine Hmga2 was appended to the Luciferase ORF (Luc). let-7 complementary sites are indicated (vertical red lines), as are mutant sites (black Xs). The Luc-m7, Luc-m4, and Luc-m2 were identical to Luc-wt, except they had seven, four, and two mutant sites, respectively. Each mutant site had two point substitutions that disrupted pairing to let-7 but created pairing to mutant let-7 (mlet-7, bottom, in blue). The seven sites were identified in a search for conserved 7- and 8-nucleotide motifs (7mer and 8mer) matching the seed region of let-7 (15). (B) Reporter repression in F9 cells supplemented with the indicated miRNA. Bars are colored to indicate the number of sites mutated in the reporter. Shown are median repression values, with error bars indicating 25th and 75th percentiles; n = 12, except experiments with no added miRNA (–), in which n = 36. Within each quartet, activity was normalized to that of the Luc-m7 reporter, except for the mlet-7 quartet, for which activity was normalized to that of the Luc-m7 reporter with noncognate miRNA (miR-124). (C) Reporter repression in NIH3T3 cells (top) or HeLa cells (bottom) supplemented with the indicated miRNA, performed and displayed as in (B). We also noticed two additional let-7 complementary sites in the murine Hmga2 mRNA, but located in the 5′ UTR. When tested in luciferase reporter assays, these sites mediated little or no repression in the different cell lines, and the mutant sites did not respond to mlet-7, indicating that any effects observed with the 5′ UTR sites were not miRNA specific.

To examine repression directed by endogenous let-7, we repeated the reporter assays using NIH3T3 cells and HeLa cells, which naturally express let-7 (Fig. 1B). In both cell types, reporter repression depended on the wild-type sites, as would be expected if the endogenous let-7 miRNA directed repression (Fig. 2C). Adding exogenous let-7 RNA enhanced repression, suggesting that let-7 RNA was subsaturating in these cells. Adding mutant let-7 also caused reporters with mutant sites to be repressed. Adding mlet-7 or miR-124 decreased repression of the reporter with wild-type sites (particularly in HeLa cells), as if the transfected miRNA was competing with endogenous let-7 RNA for a limiting factor.

Having established that the sites within the Hmga2 3′ UTR could mediate let-7–directed repression, we tested whether disrupting this repression could promote oncogenic transformation. Assays for anchorage-independent growth were performed with NIH3T3 cells, which form colonies in soft agar when stably transfected with a potent oncogene. Stably transfecting a vector expressing wild-type Hmga2 did not significantly increase the number of colonies compared with transfecting an empty vector, whereas transfecting a vector expressing a truncated Hmga2 (Hmga2-tr) (Fig. 3A), shown previously to promote anchorage-independent growth (18), produced significantly more colonies (Fig. 3B). As in human tumors, Hmga2-tr lacked the spacer, the acidic domain, and the entire 3′ UTR with its miRNA complementary sites (Fig. 3A). The increase in colonies was attributed to the loss of let-7 repression rather than the truncation of the protein because stably expressing Hmga2-m7, which had the full ORF but disrupted let-7 complementary sites (Fig. 3A), produced at least as many colonies as Hmga2-tr, whereas stably expressing Hmga2-ORFtr, which had the truncated ORF but intact miRNA complementary sites (Fig. 3A), produced a number comparable to that of Hmga2-wt (Fig. 3B). Stably expressing Hmga2-m4, which retained the first three let-7 sites, led to an intermediate number of colonies.

Fig. 3.

Soft-agar assay for anchorage-independent growth. (A) Hmga2 constructs used for stable transfection, depicted as in Fig. 2A. (B) Colony formation. For cells stably transfected with the indicated vector, the percentage that yielded colonies after 28 days is plotted (horizontal line, median; box, 25th through 75th percentile; error bars, range; n = 12 from four independent experiments, each in triplicate). All but Hmga2-wt yielded a significantly higher number of colonies than did the empty vector (Mann-Whitney test for each, P < 0.05). When compared with Hmga2-wt, a significantly higher number of colonies was observed for Hmga2-tr (P = 0.003). Hmga2-m7 showed significantly more colonies than any of the other constructs tested (P < 0.05 for each; *, P = 0.041; **, P = 0.002; ***, P = 10−6). No significant difference was observed between Hmga2-wt and the construct with the truncated ORF (P = 0.61).

We next tested whether the stably transfected cells used to assay anchorage-dependent growth were also able to form subcutaneous tumors in nude mice. Consistent with our soft-agar results, tumors were observed when injecting cells expressing constructs with mutated let-7 sites: After 5 weeks, three of four mice injected with Hmga2-m7 cells and two of four mice injected with Hmga2-m4 cells had tumors at the sites of injection. One of four injected with Hmga2-tr cells and one of four injected with Hmga2-ORFtr also had tumors, whereas no tumors were observed 5 weeks after injecting cells stably transfected with either wild-type Hmga2 or empty vector.

Taken together, our results support the proposal that the let-7 miRNA acts as a tumor-suppressor gene (19, 20) and indicate that a major mechanism of oncogenic Hmga2 translocations associated with various human tumors is the loss of let-7 repression. Thus, loss of miRNA-directed repression of an oncogene is another type of oncogene-activating event that should be considered when investigating the effects of mutations associated with cancer. Likewise, mutations that create miRNA-directed repression of tumor-suppressor genes might also impart a selective advantage to the tumor cells. In this regard, we note that Hmga2 translocations frequently append the Hmga2 3′ UTR to the 3′ end of known tumor-suppressor genes, including FHIT, RAD51L1, and HEI10 (5, 8, 9), suggesting that let-7–directed repression of these translocation partners might cooperate with disrupting Hmga2 repression to promote tumorigenesis.

Vertebrate miRNAs can each have hundreds of conserved targets and many additional nonconserved targets (15, 21–25), all of which have confounded exploration of the biological impact of particular miRNA-target relationships. In worms, flies, and plants, repression of particular targets is known to be relevant because genetic studies have investigated what happens when that target alone is not repressed by the miRNA (26–28). Because of the possibility that multiple interactions might need to be perturbed to observe a phenotypic consequence in mammals, it has been unclear whether the importance of a particular mammalian miRNA-target interaction can be demonstrated experimentally. Our results, combined with previous cytogenetic studies that speak to the effect of misregulating the endogenous human HMGA2 gene, show that disrupting miRNA regulation of Hmga2 enhances oncogenic transformation, thereby demonstrating that disrupting miRNA regulation of a single mammalian gene can have a cellular phenotype in vitro and a clinical phenotype in vivo.

Supplementary Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1137999/DC1

Materials and Methods

SOM Text

Figs. S1 and S2

References

References and Notes

- 1.Sgarra R, et al. FEBS Lett. 2004;574:1. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fedele M, et al. Oncogene. 2002;21:3190. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoenmakers EF, et al. Nat Genet. 1995;10:436. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geurts JM, Schoenmakers EF, Van de Ven WJ. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1997;95:198. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(96)00411-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mine N, et al. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:135. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb01075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedele M, et al. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1583. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.10.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petit MM, Mols R, Schoenmakers EF, Mandahl N, Van de Ven WJ. Genomics. 1996;36:118. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoenmakers EF, Huysmans C, Van de Ven WJ. Cancer Res. 1999;59:19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geurts JM, Schoenmakers EF, Roijer E, Stenman G, Van de Ven WJ. Cancer Res. 1997;57:13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue N, et al. Blood. 2006;108:4232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borrmann L, Wilkening S, Bullerdiek J. Oncogene. 2001;20:4537. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battista S, et al. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldassarre G, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141224998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Cell. 2005;120:15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasquinelli AE, et al. Nature. 2000;408:86. doi: 10.1038/35040556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutvagner G, Simard MJ, Mello CC, Zamore PD. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E98. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 18.Fedele M, et al. Oncogene. 1998;17:413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson SM, et al. Cell. 2005;120:635. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takamizawa J, et al. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3753. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krek A, et al. Nat Genet. 2005;37:495. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim LP, et al. Nature. 2005;433:769. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farh KK, et al. Science. 2005;310:1817. doi: 10.1126/science.1121158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krutzfeldt J, et al. Nature. 2005;438:685. doi: 10.1038/nature04303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giraldez AJ, et al. Science. 2006;312:75. doi: 10.1126/science.1122689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Cell. 1993;75:855. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai EC, Tam B, Rubin GM. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1067. doi: 10.1101/gad.1291905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Bartel B. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:19. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.We thank M. Narita and S. Lowe for providing the Hmga2 antibody, and C. Jan, A. Grimson, and M. Narita for helpful discussions and advice. Supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (C.M.) and the NIH (D.B.). D.B. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1137999/DC1

Materials and Methods

SOM Text

Figs. S1 and S2

References