Abstract

Background and Purpose: Physical therapists have an important role in the management of clinical knee osteoarthritis (OA) through designing and supervising exercise programs. This study explored whether their current use of therapeutic exercise for patients with this condition is in line with recent recommendations.

Subjects and Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted with a random sample of chartered (licensed) physical therapists (N=2,000) practicing in the United Kingdom. This survey included a vignette describing a patient with clinical knee OA as well as clinical management questions relating to the respondents’ use of therapeutic exercise.

Results: The questionnaire response rate was 58% (n=1,152), with 538 respondents stating they had treated a patient with clinical knee OA in the preceding 6 months. In line with recent recommendations, 99% of the physical therapists stated they would use therapeutic exercise for this patient population, although strengthening exercises were favored over aerobic exercises. Although nearly all physical therapists would monitor exercise adherence, only 12% would use an exercise diary. Seventy-six percent of physical therapists would provide up to 5 treatment sessions, and only 34% would offer physical therapy follow-up after discharge.

Discussion and Conclusions: The measure of physical therapists’ current clinical practice was self-reported clinical behavior on the basis of a vignette. Although this is a valid measure of clinical behavior, in practice, physical therapists may use therapeutic exercise differently. There are disparities between physical therapists’ current use of therapeutic exercise for clinical knee OA and recent recommendations. Identifying potential ways to overcome these disparities is an important step toward optimizing the outcome from therapeutic exercise for patients with clinical knee OA.

Knee pain attributable to osteoarthritis (OA) is a common disabling problem in older adults1 and will increase in prevalence as the population ages2 and as obesity levels, a risk factor, continue to rise.3 The clinical problem of knee OA embraces a spectrum of knee pain and includes a subgroup of patients who show radiographic changes in the medial and lateral tibiofemoral joints and patellofemoral joint.4,5 People with clinical knee OA frequently experience persistent, chronic pain as well as reduced movement, strength (force-generating capacity), and balance and limitations in daily activities.6

Clinical knee OA usually is managed in primary care7 with analgesics and nonpharmacological options, such as exercise.8 Exercise has been shown to improve function, strength, walking speed, and self-efficacy and to reduce pain and the risk of other chronic conditions.9,10 It also shifts consultation behavior away from the traditional general practitioner-led model of care and reduces the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.11 Disappointingly, however, effect sizes from exercise interventions for clinical knee OA in randomized controlled trials are small and often decline over time.11–13 There could be several explanations for these findings, including inadequate exercise dose or progression, insufficient tailoring of the exercise program for people, or poor exercise adherence.

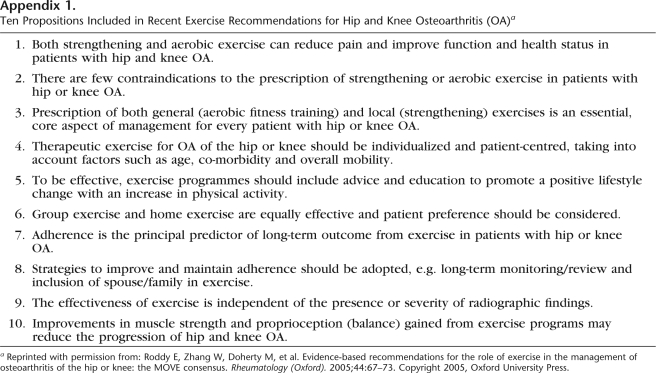

Clinical guidelines and systematic reviews recommend exercise for clinical knee OA,14–21 although they do not provide clear guidance on how to optimize the outcome from exercise, gain greater improvements in function and pain reduction, or maintain improvements over time. Recently, a multidisciplinary group developed recommendations that address specific questions about the role of exercise in lower-limb OA.22 These recommendations incorporate research-based evidence and expert opinion and include 10 propositions about the role of exercise, such as the benefit of specific types of exercises (local strengthening and aerobic exercises), the effectiveness of exercise completed in different settings (group exercise versus home exercise), and the importance of exercise adherence. They advocate regular participation in exercise that should be sustained over time. The recommendations are presented in Appendix 1.

Physical therapists have an important role in the primary care management of clinical knee OA through designing and supervising exercise programs. Physical therapy is recommended as an early management option for patients with knee OA,14,16,23 and it is estimated that between 10% and 31.5% of older adults are referred to or consult a physical therapist about their knee problems.24–26 At present, little is known about physical therapists’ use of exercise in the management of clinical knee OA and whether exercise is being used in ways that may optimize outcomes.

We aimed to describe chartered (licensed) physical therapists’ current use of therapeutic exercise for patients with clinical knee OA in the United Kingdom and to explore whether it is in line with recent exercise recommendations.22 We also investigated whether the therapeutic exercise prescribed for clinical knee OA differed across groups of physical therapists, including those working in different practice settings and those with different backgrounds in training and experience.

Method

Design

A descriptive, cross-sectional survey of physical therapists who were currently practicing in the United Kingdom and who were members of The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) (a professional body) was completed between January and May 2006.

Sample

To access physical therapists currently practicing in the United Kingdom, a simple random sample of chartered physical therapists was identified from the CSP membership list. The physical therapists received a questionnaire package, which included a cover letter from the CSP, an invitation letter from the study team to take part, an information leaflet, a questionnaire, and a prepaid envelope for returning responses. To preserve physical therapists’ anonymity, CSP membership details were not released to the study team; the CSP administered the survey on our behalf. Because the information on CSP members did not include clinical specialties, a filter question at the beginning of the questionnaire screened for physical therapists who had treated at least one patient with clinical knee OA in the preceding 6 months. A reminder questionnaire was sent from the CSP to all nonresponders 4 weeks after the initial mailing. Four weeks after the second mailing, to allow an estimate of potential nonresponse bias, a brief questionnaire was sent to 30% of the nonresponders.

A pilot study (n=200) provided a 60% response rate after the follow-up reminder, similar to the response rates in other UK-based surveys of physical therapists,27 and established that approximately 4 of 10 physical therapists reported they had seen a patient with knee pain in the preceding 6 months. On the basis of this estimate, 1,800 questionnaires were posted for the main study to achieve approximately 400 applicable responses for analysis. This value was sufficient to allow survey estimates (proportions) to be calculated with a margin of error of less than 5% and with 95% confidence.28

Survey Instrument

Measure of clinical practice.

A vignette representing a typical primary care patient receiving physical therapy treatment for clinical knee OA was included in the survey questionnaire, along with a series of closed-format questions asking physical therapists to report how they would manage the patient's condition. The details of the patient vignette are presented in Appendix 2, and the questions included in the survey are presented in Appendix 3. The questions sought information on likely treatment approach, number of treatment sessions, and whether respondents would offer any physical therapy follow-up after discharge. Specific questions on their use of therapeutic exercise also were included; these questions sought details regarding the types of exercises that they would prescribe, how the exercises would be delivered, and whether they would monitor exercise adherence.

Clinical vignettes are a valid measure of the clinical behavior of health care professionals, including physical therapists.29,30 They are easy to administer at low cost, and variables within them can be easily manipulated.29 In line with current literature,31–33 the vignette was based on the research records of an anonymous patient who had clinical knee OA and who had received physical therapist-led exercises as part of a previous clinical trial.10 The vignette included the information that a physical therapist would seek to obtain during an initial patient assessment, including a history of the present complaint, current symptoms, and examination findings. The vignette was tested with 12 expert physical therapists in the field of knee pain research, musculoskeletal pain research, or both to determine whether sufficient information was included for clinical decision making. As a result, some minor modifications were made to the vignette; details on the patient's mobility status and analgesic use were added. The vignette and associated questions were tested in a prepilot study (n=12) and in the pilot study before being included in the final cross-sectional survey.

Other survey measures.

Demographic questions captured data on physical therapists’ clinical experience; the frequency with which they treated patients with clinical knee OA; their work setting; their postgraduate education in therapeutic exercise, clinical knee OA, or both; their personal experience with knee pain; and current physical activity levels, as measured with a short telephone activity recall questionnaire adapted for use with a postal survey.34 This information permitted full description of the sample and comparison of practice behaviors across different groups of physical therapists.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 14)* after checking for and correcting any data entry anomalies. Descriptive statistics were used to explore physical therapists’ use of therapeutic exercise for clinical knee OA. The Pearson chi-square test (continuity corrected if necessary) and the Fisher exact test were used to investigate whether differences in exercise delivery between groups of physical therapists were statistically significant. Only results with a P value of less than .01 are discussed; a conservative threshold was chosen to reduce the chance of reporting statistically significant findings arising solely from the number of statistical tests completed.

Results

Response Rate

Given that only very minor changes were made following the pilot study, data from the pilot study were combined with data from the main study (n=1,800) for analysis. For the 2,000 questionnaires sent, there were 8 exclusions (because of incorrect addresses) and 1,152 responses (adjusted response rate, 58%). Of the 1,152 responding physical therapists, 538 (47%) reported that they had treated at least one patient with clinical knee OA in the preceding 6 months. The applicable responses are summarized below.

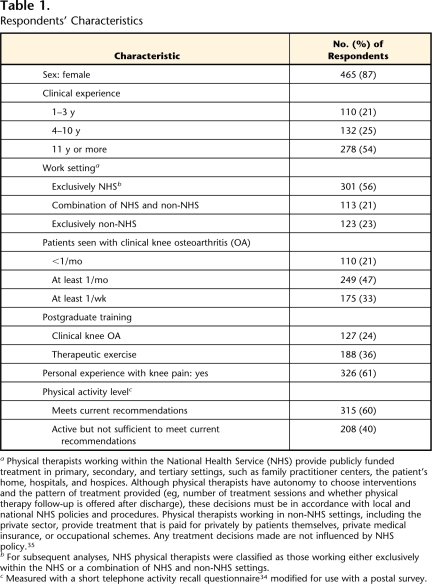

Characteristics of Physical Therapists

The characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1.35 The majority of the physical therapists were women (87%), worked in the National Health Service (NHS) (77%), and had 4 or more years of clinical experience (79%). The mean number of years of clinical experience was 15 (SD=11). In total, 24% and 36% of the physical therapists reported having completed postgraduate training in the field of clinical knee OA and in therapeutic exercise, respectively. The training varied and included in-house training (eg, “a seminar on current knee OA research”), specific short courses (eg, “Pilates instruction”), and formal training as part of a degree (eg, a physical therapy master's degree or bachelor's degree in exercise physiology). In total, 61% of the respondents had personal experience with knee pain, and 60% were sufficiently active to meet current physical activity guidelines.36

Table 1.

Respondents’ Characteristics

aPhysical therapists working within the National Health Service (NHS) provide publicly funded treatment in primary, secondary, and tertiary settings, such as family practitioner centers, the patient's home, hospitals, and hospices. Although physical therapists have autonomy to choose interventions and the pattern of treatment provided (eg, number of treatment sessions and whether physical therapy follow-up is offered after discharge), these decisions must be in accordance with local and national NHS policies and procedures. Physical therapists working in non-NHS settings, including the private sector, provide treatment that is paid for privately by patients themselves, private medical insurance, or occupational schemes. Any treatment decisions made are not influenced by NHS policy.35

bFor subsequent analyses, NHS physical therapists were classified as those working either exclusively within the NHS or a combination of NHS and non-NHS settings.

cMeasured with a short telephone activity recall questionnaire34 modified for use with a postal survey.

Nonresponders

Of the 250 nonresponders who were sent a brief questionnaire, 8 were excluded because they subsequently returned the full questionnaire. The adjusted response rate was 12% (29/242); 11 physical therapists (38%) reported having treated at least one patient with clinical knee OA in the preceding 6 months. On average, physical therapists returning the brief questionnaire were less likely to report treating patients with clinical knee OA in the preceding 6 months, to be female (54%), and to work in an NHS setting (54%) than physical therapists returning the full questionnaire.

Treatment Approaches

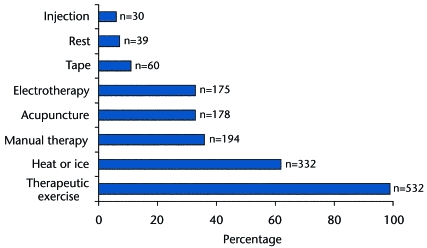

The treatment approaches used for clinical knee OA by the respondents are summarized in Figure 1.37 Therapeutic exercise was the most common approach, with 99% of physical therapists reporting using it. It was mostly used in conjunction with other treatment approaches, including heat or ice (62%), manual therapy (36%), acupuncture (33%), and electrotherapy (33%); only 9% of physical therapists reported they would use therapeutic exercise alone. All physical therapists reported including advice as part of their treatment. This advice commonly focused on pacing of activities (balancing activity with rest), weight loss, and use of heat or ice at home. In total, 29% of the respondents advised patients to increase their general activity levels; 3% encouraged a reduction in activity levels. Fewer than 20% advised patients to rest more and avoid painful activities.

Figure 1.

Treatment approaches used by physical therapists for clinical knee osteoarthritis. In the United Kingdom, injection therapy can be used by physical therapists who have received appropriate training. Injections may be administered to peripheral intra-articular or periarticular lesions of the upper and lower extremities, without a prescription from a physician. Electrotherapy is the use of electrical, electromagnetic, and acoustic energy for therapeutic purposes. Modalities include ultrasound, pulsed shortwave diathermy, interferential current, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.37 Manual therapy is the use of hands-on interventions, typically including joint mobilization, manipulation, and massage.

Use of Therapeutic Exercise

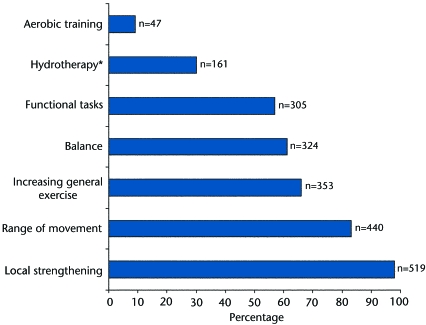

As summarized in Figure 2,38 the most common types of exercises prescribed were local strengthening (98%) and range-of-movement exercises (83%). In total, 66% of physical therapists would aim to increase a patient's general exercise levels, for example, through advising the patient to undertake more walking or swimming; however, only 9% would prescribe a formal aerobic training program.

Figure 2.

Types of exercises prescribed by physical therapists for clinical knee osteoarthritis. Functional tasks include the replication of a functional activity (eg, rising from a sitting position) in the exercise program. Range of movement includes specific exercises to improve the functional range of movement of a joint. These exercises are usually performed throughout the whole joint range and can be completed actively, passively, or with active assistance.38 Data for hydrotherapy were from the main study only because of changes in questions between the pilot study and the main study.

The majority of physical therapists reported that, during the initial treatment session, they would deliver written (90%) or verbal (82%) advice on home exercises. Only 56% of the respondents reported that they would supervise (oversee) the exercises in the clinic or the patient's home, 10% reported that they would refer the patient to an exercise class, and 4% reported that they would refer the patient to a physical therapist student, physical therapist assistant, or technical instructor† to continue treatment while still maintaining overall responsibility for treatment of the patient. Approximately half of the respondents indicated that, during follow-up visits (where applicable), they would provide verbal (51%) or written (50%) advice about home exercises, 62% would supervise the exercises, and 52% would refer the patient to an exercise class. One third of the respondents reported that they would refer the patient to a physical therapist student, physical therapist assistant, or technical instructor at this time. Nearly all physical therapists (97%) reported that they would check on whether the patient was completing the exercise program, mainly through observing the patient's exercise technique (92%), verbally questioning the patient (76%), and monitoring changes in physical examination findings (69%) and self-report measures (eg, pain and function levels) (57%). Only 12% of physical therapists reported that they would instruct the patient in the use of an exercise diary.

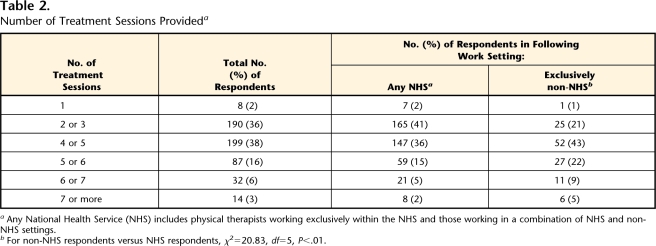

As shown in Table 2, most physical therapists reported that they would choose to treat a patient with up to 5 treatment sessions; 36% would see a patient 2 or 3 times, and 38% would see a patient 4 or 5 times. Only 34% of the respondents would choose to offer the patient any physical therapy follow-up after discharge, through an open appointment (allowing the patient to request further assessment and treatment within a set time period) (60%), a telephone review (17%), or a “one-off” (a single additional) follow-up session (17%). The most common reasons for not providing follow-up were as follows: the patient was expected to self-manage (78%) and the patient would have been referred to another health care professional (44%), most commonly an orthopedic surgeon or a rheumatologist. In total, 29% of the respondents reported that within their physical therapy service, there was no facility to provide follow-up after discharge for the current episode of care.

Table 2.

Number of Treatment Sessions Provideda

Any National Health Service (NHS) includes physical therapists working exclusively within the NHS and those working in a combination of NHS and non-NHS settings.

bFor non-NHS respondents versus NHS respondents, χ2=20.83, df=5, P<.01.

Comparison of Groups of Physical Therapists

During follow-up treatment sessions, NHS physical therapists (including those working exclusively in the NHS and those working in a combination of NHS and non-NHS settings) were more likely than therapists working exclusively in non-NHS settings to refer patients to an exercise group (58% versus 30%, difference=28%, 99% confidence interval [CI]=16–40) or to a physical therapist student or physical therapy assistant (33% versus 11%, difference=22%, CI=11–30). In contrast, non-NHS physical therapists were more likely to provide verbal and written advice on home exercises at follow-up (for verbal advice: 62% versus 48%, difference=14%, CI=0–23; for written advice: 64% versus 46%, difference=18%, CI=5–30). They also were more likely to provide more treatment sessions (Tab. 2; χ2=20.83, df=5, P<.01) and physical therapy follow-up after discharge (71% versus 23%, difference=48%, CI=36–59) than therapists working in the NHS.

Compared with their more experienced colleagues, physical therapists with up to 3 years of clinical experience were less likely to prescribe balance exercises (49% versus 64%, difference=15%, CI=2–28), more likely to refer patients to an exercise class during follow-up treatment sessions (72% versus 46%, difference=26%, CI=12–37), and less likely to provide physical therapy follow-up after discharge (19% versus 38%, difference=19%, CI=6–29).

Physical therapists with postgraduate training in clinical knee OA were more likely to provide balance exercises (71% versus 57%, difference=13%, CI=1–25) and to offer physical therapy follow-up after discharge (48% versus 30%, difference=18%, CI=5–31) than those without postgraduate training in clinical knee OA.

There were no statistically significant differences (defined as a P value of <.01) in the exercise behaviors of physical therapists with and those without personal experience with knee pain, in those who were sufficiently active to meet current exercise recommendations versus those who were not, in the treatment of fewer than or more than one patient with clinical knee OA per month, or in postgraduate training in therapeutic exercise.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first national survey within the United Kingdom to explore physical therapists’ use of therapeutic exercise for clinical knee OA. The responses provide insight into whether current clinical practice is in line with recent exercise recommendations.22 In line with those recommendations, nearly all physical therapists reported using therapeutic exercise, monitoring exercise adherence in some way, and providing advice as part of their treatment of patients with clinical knee OA. However, there were some disparities between recent exercise recommendations and current clinical practice in terms of the types of exercises prescribed, the delivery of the exercises, and issues related to adherence.

Types of Exercises Prescribed

The majority of physical therapists favored local exercises, including muscle strengthening and range-of-movement exercises, over more general exercises, including increasing general activity, completing functional tasks (which may include elements of both local and general exercises), and aerobic training programs. Both local and general (aerobic) exercises reduce pain and improve function and health status in patients with clinical knee OA39 and are an essential, core aspect of management for every patient with knee OA, according to recent exercise recommendations22 and current clinical guidelines.17,19 Although local exercises have been shown to be effective in reducing pain and disability in people with knee OA and there is no advantage of one form of exercise over the other,39 including both local and general exercises may provide even greater improvements with regard to pain and function than strengthening exercises alone. A recent best-evidence summary of systematic reviews concluded that therapeutic exercise (in comparison with a no-treatment control) consisting of strengthening, stretching, and functional exercises is effective for patients with knee OA.18 It has been recommended that rehabilitation of patients with knee OA include a variety of exercises to address sensory and motor deficits and to practice skills required to meet the challenges of daily life.40

In this study, 40% of physical therapists did not prescribe balance exercises, which have been shown to improve muscle function and reduce disability41 and which recent exercise recommendations22 have suggested may reduce the progression of knee OA. Not including balance exercises in an exercise program, therefore, may limit the potential benefits to patients from the exercise program.

Delivery of Exercises

In line with recent exercise recommendations,22 during the initial treatment session, the majority of physical therapists reinforced the verbal advice provided on home exercises with written advice. This reinforcement can act as a prompt for patients to complete the exercise program at home, thus improving exercise adherence.42 However, 56% of the therapists did not supervise the exercises during the initial treatment session, and 62% did not supervise the exercises during follow-up treatment sessions. The recommendations do not provide advice on whether exercises should be supervised; however, recent French guidelines for lower-limb OA promote supervised physical therapy-led exercises (at least 8 sessions, or more than 4 hours) followed by a patient-administered home program.43 There is evidence that, for other musculoskeletal conditions, supervised exercises are more effective in improving pain and function scores than unsupervised home exercises.44 Supervision of exercises has a number of potential benefits: it may improve patient safety; it allows instruction and correction on proper exercise technique and advice on what to do in the presence of pain; it facilitates the provision of appropriate dose, progression, and individual tailoring of the exercise program36; and it may enhance exercise adherence.45 Lack of supervision of an exercise program, therefore, may reduce its overall effectiveness.

Our survey showed that physical therapy for clinical knee OA in the United Kingdom is delivered over relatively few treatment sessions. The majority of physical therapists provided up to 5 treatment sessions, although most NHS physical therapists provided only 2 or 3 sessions. Although recent exercise recommendations22 do not provide guidance on an optimal number of exercise sessions, randomized trials that support exercise for knee OA have included 6,10 12,46 or even more47 exercise sessions. Delivering more exercise sessions may facilitate adequate progression of the exercise program in terms of intensity and difficulty and thereby potentially optimize its benefits.48

Exercise Adherence

Recent exercise recommendations22 highlight the importance of adherence in determining long-term outcome from exercise in patients with knee OA. The physical therapists in our survey commonly reported monitoring exercise adherence through verbal questioning, observing the patient's exercise technique, and monitoring changes in self-reported symptoms and clinical examination findings. Although all of these methods are simple and inexpensive, each has disadvantages. Self-reported exercise levels may be overestimated by the patient in an attempt to be viewed positively by the health care professional,42 and exercises performed under direct observation and in an unfamiliar health care environment may not represent how the exercises are performed at home.49 The use of clinical outcomes such as pain, range of movement, and muscle strength as proxy measures of exercise adherence assumes a direct relationship between exercise adherence and outcome. However, the latter could be influenced by other factors, such as the natural history of the condition or the use of cointerventions, such as analgesics. In such cases, clinical outcome may improve even in the presence of poor exercise adherence.49

Recent exercise recommendations22 state that strategies to improve and maintain adherence should be adopted. The use of an exercise diary was the least popular method of monitoring exercise adherence in our sample of physical therapists. Although an exercise diary may be prone to the biases of self-report, this method of assessing exercise adherence has the advantage of allowing the patient to self-monitor exercise and activity habits and to become more aware of health-related behavior and its link to symptoms; such awareness can improve adherence to therapeutic exercise.49 In addition, the recommendations suggest long-term review as a strategy to improve exercise adherence. Only approximately one third of the physical therapists in our sample provided any physical therapy follow-up after patient discharge. As a result, opportunities for patients to return to ask questions, seek reassurance when they found the exercises painful or difficult, ensure progress in the intensity of the exercise program over time, and maintain motivation for exercise were limited.

Differences Between Groups of Physical Therapists

There were differences in the delivery of exercises across different health care settings, with physical therapists in the NHS providing fewer treatment sessions and referring more patients to exercise groups or classes or other staff, including physical therapist students, physical therapist assistants, or technical instructors. Although recent exercise recommendations22 state that individual home exercise and group exercise are equally effective for clinical knee OA, they also indicate that patient choice should be considered in the determination of exercise setting. Service issues, such as waiting list pressures in the UK NHS, may have been the predominant factor influencing the results of our survey. Physical therapists with up to 3 years of clinical experience were less likely to include balance exercise as part of their treatment or to offer physical therapy follow-up after discharge than their more experienced colleagues. Given that these trends were reversed in physical therapists with postgraduate training in the field of clinical knee OA, the provision of education and training, starting at the entry undergraduate level, in areas of disparities between current clinical practice and recent exercise recommendations may help to optimize the outcome from exercise for patients with clinical knee OA.

Clinical and Research Implications

Recent exercise recommendations22 are based on available evidence from randomized controlled trials showing that exercise is beneficial for clinical knee OA.15 Our survey showed that exercise delivered by physical therapists in current clinical practice is rather different from that seen in the randomized controlled trials on which the recent recommendations were based: it is prescribed differently across different health care settings, it is delivered over fewer treatment sessions, and patients are generally not supervised as much while completing the exercise program or monitored after discharge from physical therapy services. This potential gap between the recent recommendations and clinical reality may mean that exercise for clinical knee OA in practice in the United Kingdom may be less effective than that seen in recent randomized controlled trials, although this study did not quantify this parameter. Further research should address how to optimize the delivery of exercise for clinical knee OA in practical ways that are feasible in the current health care system.

Limitations of This Study

This study has a number of limitations. Although the questionnaire response rate was in keeping with response rates in other, similar surveys of physical therapists in the United Kingdom27 and a comparison of responders and nonresponders was made, nonresponder bias may have been present, reducing the generalizability of the findings to all physical therapists in the United Kingdom. The measure of physical therapists’ current clinical practice was self-reported clinical behavior, on the basis of a vignette. Although vignettes have been shown to reliably assess clinical behavior, it is possible that, in clinical practice, physical therapists may use therapeutic exercise differently. Additionally, as with all written vignettes, limited information about the patient was included, and some physical therapists may have wanted more information on which to base their clinical decisions. Therefore, patterns of treatment in practice may be different. Although the use of a postal survey allowed data to be gathered from a large sample at one point in time, to avoid overburdening respondents, only a limited number of questions were included. Despite the fact that the survey captured data describing physical therapists’ broad use of therapeutic exercise, many questions still remain unanswered, such as the specific dose of exercise prescribed, whether exercise was individually tailored, and whether (and how) progression of exercise programs was used. This detailed information would be of benefit for further identifying how best to optimize the outcome from exercise for patients with clinical knee OA.

Conclusion

This study has indicated that chartered physical therapists in the United Kingdom consistently use therapeutic exercise to treat clinical knee OA, incorporate advice about positive lifestyle changes as part of their treatment, and monitor exercise adherence in some way. However, in contrast to recent exercise recommendations,22 local exercise is favored over aerobic or general exercise, strategies to improve adherence are underused, and exercise is delivered over relatively few treatment sessions. The differences in clinical behaviors of physical therapists working in different health care settings highlight the role that service restrictions play in the prescription and supervision of exercise programs, and the findings also suggest that further education and training for physical therapists about exercise for clinical knee OA could be of benefit. Overall, the results show that there are some disparities between current clinical practice and recent exercise recommendations and identify potential ways to overcome these disparities. Further research is needed to improve the outcome from exercise for patients with clinical knee OA.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1.

Appendix 1.

Ten Propositions Included in Recent Exercise Recommendations for Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis (OA)a

a eprinted with permission from: Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the role of exercise in the management of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: the MOVE consensus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44:67–73. Copyright 2005, Oxford University Press.

Appendix 2.

Appendix 2.

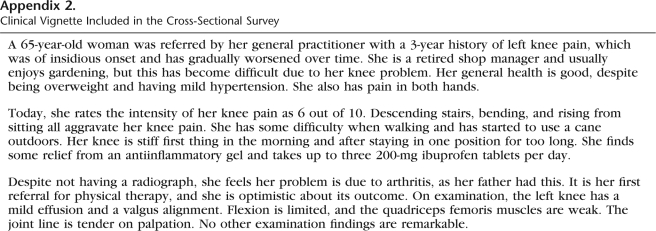

Clinical Vignette Included in the Cross-Sectional Survey

Appendix 3.

Appendix 3.

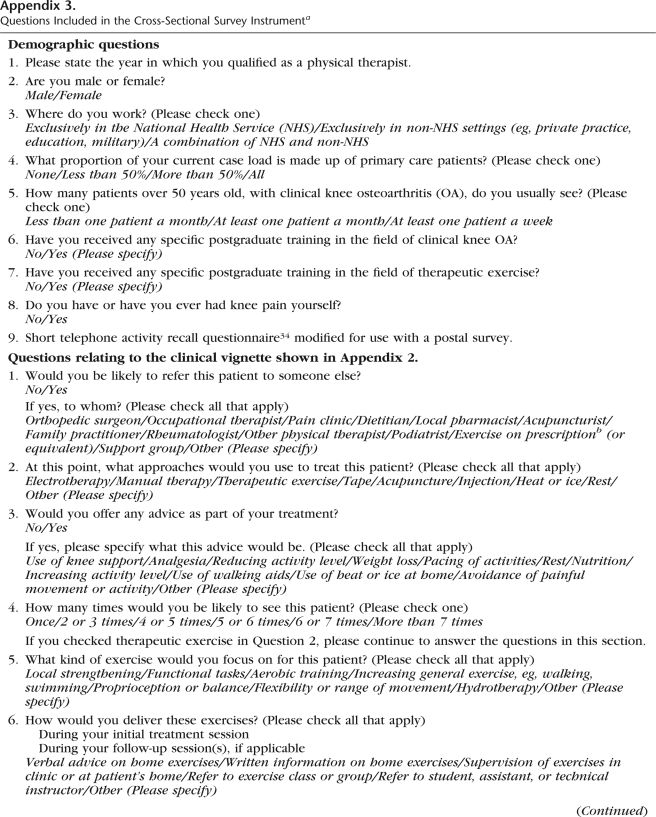

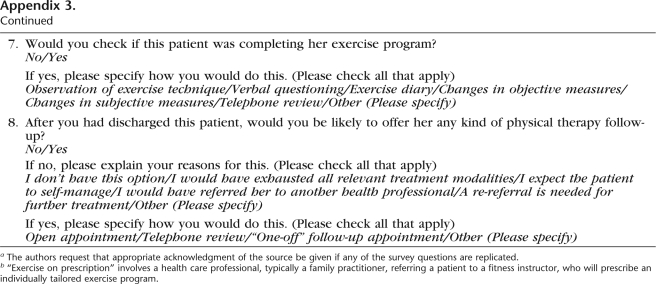

Questions Included in the Cross-Sectional Survey Instrumenta

a The authors request that appropriate acknowledgment of the source be given if any of the survey questions are replicated.

b “Exercise on prescription” involves a health care professional, typically a family practitioner, referring a patient to a fitness instructor, who will prescribe an individually tailored exercise program.

Dr Foster provided concept/idea/research design and fund procurement. Ms Holden provided writing, data collection and analysis, and project management. Ms Nicholls and Dr Hay provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission).

For assistance with generating the sample and administering the survey, the authors thank The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. For ongoing support throughout the study, they thank Julie Young, Dr Elaine Thomas, Professor Mike Doherty, and Dr Edward Roddy. They also thank all of the physical therapists who participated in the study.

Approval to complete this study was granted by the North Staffordshire Research Ethics Committee.

An abstract of this study was presented orally at the Physiotherapy Research Society Conference; March 28, 2007; Cardiff, United Kingdom.

This study was funded by the Physiotherapy Research Foundation, The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy Charitable Trust, and the NHS North Staffordshire Primary Care Research Consortium. Dr Foster is funded by a Primary Care Career Scientist Award from the Department of Health and NHS R&D. Ms Holden is funded by an Allied Health Professional Training Fellowship from the Arthritis Research Campaign (grant reference 18004).

SPSS Inc, 233 S Wacker Dr, Chicago, IL 60606.

Both physical therapist assistants and technical instructors offer a supportive role to physical therapists, for example, through continuing to supervise a patient completing an exercise program prescribed by a physical therapist.

References

- 1.Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilmoth JR. Demography of longevity: past, present and future trends. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:1111–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James WP. The epidemiology of obesity: the size of the problem. J Intern Med. 2008;263:336–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peat G, Thomas E, Croft P. Staging joint pain and disability: a brief method using persistence and global severity. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan R, Peat G, Thomas E, et al. Symptoms and radiographic osteoarthritis: not as discordant as they are made out to be? Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:86–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creamer P, Hochberg MC. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 1997;350:503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott DL, Shipley M, Dawson A, et al. The clinical management of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: strategies for improving clinical effectiveness. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lane NE, Thompson JM. Management of osteoarthritis in the primary-care setting: an evidence-based approach to treatment. Am J Med. 1997;103:25S–30S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Baar ME, Assendelft WJJ, Dekker J, et al. Effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1361–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster NE, Thomas E, Barlas P, et al. Acupuncture as an adjunct to exercise based physiotherapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hay EM, Foster NE, Thomas E, et al. Effectiveness of community physiotherapy and enhanced pharmacy review for knee pain in people aged over 55 presenting to primary care: pragmatic randomised trial. BMJ. 2006;333:995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas KS, Muir KR, Doherty M, et al. Home based exercise programme for knee pain and knee osteoarthritis: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325:752–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pisters MF, Veenhof C, van Meeteren, et al. Long-term effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1245–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Radiology. Guidelines for the medical management of osteoarthritis, part 2: osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1541–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fransen M, McConnell S, Bell M. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD004286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis—report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis.2003;62:1145–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:981–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smidt N, de Vet HC, Bouter LM, et al. Effectiveness of exercise therapy: a best-evidence summary of systematic reviews. Aust J Physiother. 2005;51:71–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Osteoarthritis: National Clinical Guidance for Care and Management in Adults. London, United Kingdom: Royal College of Physicians; 2008.

- 20.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:137–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamtvedt G, Dahm KT, Christie A, et al. Physical therapy interventions for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: an overview of systematic reviews. Phys Ther. 2008;88:123–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the role of exercise in the management of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: the MOVE consensus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porcheret M, Jordan K, Jinks C, et al. Primary care treatment of knee pain: a survey in older adults. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1694–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jinks C, Jordan KM, Ong BN, Croft P. A brief screening tool for knee pain in primary care (KNEST): results from a survey in the general population aged 50 and over. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jordan KM, Sawyer S, Coakley P, et al. The use of conventional and complementary treatments for knee osteoarthritis in the community. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:381–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell HL, Carr AJ, Scott DL. The management of knee pain in primary care: factors associated with consulting the GP and referrals to secondary care. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:771–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bishop A, Foster NE. Do physical therapists in the United Kingdom recognise psychosocial factors in patients with acute low back pain? Spine. 2005;30:1316–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordan K, Ong BN, Croft P. 1998. Mastering Statistics: A Guide for Health Service Professionals and Researchers. Cornwall, United Kingdom: Stanley Thornes Ltd; 1998.

- 29.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, et al. Comparison of vignettes, standardised patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283:1715–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutten GM, Harting J, Rutten ST, et al. Measuring physiotherapists’ guideline adherence by means of clinical vignettes: a validation study. J Eval Clin Pract.2006;12:491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flaskerud JH. Use of vignettes to elicit responses toward broad concepts. Nurs Res.1979;28:210–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanza M. A methodological approach to enhance external validity in simulation based research. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1990;11:407–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanza M, Carifio J. Use of a panel of experts to establish validity for patient assault vignettes. Eval Rev. 1992;17:82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthews CE, Ainsworth BE, Hanby C, et al. Development and testing of a short physical activity recall questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:986–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Home page. Available at: www.csp.org.uk. Accessed June 27, 2008.

- 36.American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- 37.Belanger AY. Evidence-Based Guide to Therapeutic Physical Agents. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002.

- 38.Hall CM, Brody LT. Therapeutic Exercise: Moving Toward Function. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- 39.Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M. Aerobic walking or strengthening exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee? A systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:544–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurley MV. Muscle dysfunction and effective rehabilitation of knee osteoarthritis: what we know and what we need to find out. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hurley MV, Scott DL. Improvement in quadriceps sensorimotor function and disability of patients with knee osteoarthritis following a clinically practicable exercise regime. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:1181–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marks R, Allegrante JP. Chronic osteoarthritis and adherence to exercise: a review of the literature. J Aging Phys Act. 2005;13:434–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delarue Y, de Branche B, Anract P, et al. Supervised or unsupervised exercise for the treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis: clinical practice recommendations. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2007;50:759–768, 747–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G. Systematic review: strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med.2005;142:776–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friedrich M, Cermak T, Maderbacher P. The effect of brochure use versus therapist teaching on patients performing therapeutic exercise and on changes in impairment status. Phys Ther. 1996;76:1082–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hurley MV, Walsh NE, Mitchell HL, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a rehabilitation program integrating exercises, self-management and active coping strategies for chronic knee pain: a cluster randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1211–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ettinger WH Jr, Burns R, Messier SP, et al. A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST). JAMA. 1997;277:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petrella RJ, Bartha C. Home based exercise therapy for older patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2215–2221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meichenbaum D, Turk D. Facilitating Treatment Adherence. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1987.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.