Abstract

The GABAB receptor is well recognized as being composed of two subunits, GABAB1 and GABAB2. Both subunits share structural homology with other class-III G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). They are composed of two main domains, a heptahelical domain (HD) typical of all GPCRs and a large extracellular domain (ECD). Although GABAB1 binds GABA, GABAB2 is required for GABAB1 to reach the cell surface. However, it is still not demonstrated whether the association of these two subunits is always required for function in the brain. Indeed, GABAB2 plays a major role in the coupling of the heteromer to G proteins, such that it is possible that GABAB2 can transmit a signal in the absence of GABAB1. Today only ligands interacting with GABAB1 ECD have been identified. Thus compounds acting exclusively on the GABAB2 subunit will be helpful in analyzing the specific role of this subunit in the brain. Here, we explored the mechanism of action of CGP7930, a compound described as a positive allosteric regulator of the GABAB receptor. We showed that it activates the wild type GABAB receptor, though with a low efficacy, the GABAB2 HD being necessary for this effect, although one can not exclude that CGP7930 could also bind to GABAB1. Of interest, CGP7930 could activate GABAB2 expressed alone, and is the first described agonist of GABAB2. Finally, we show that CGP7930 retains its agonist activity on a GABAB2 subunit deleted of its ECD. This demonstrates the HD of GABAB2 behaves like a rhodopsin-like receptor, as it can reach the cell surface alone, can couple to G-protein and be activated by agonists. These data open new strategies for studying the mechanism of activation of GABAB receptor and examine any possible role of homomeric GABAB2 receptors.

Keywords: Allosteric Regulation; Animals; Cell Line; Dimerization; Dose-Response Relationship, Drug; GTP-Binding Proteins; metabolism; Humans; Inositol Phosphates; metabolism; Ligands; Mutagenesis, Site-Directed; Phenols; metabolism; Protein Structure, Tertiary; Protein Subunits; agonists; chemistry; genetics; metabolism; Receptors, GABA-B; agonists; chemistry; genetics; metabolism; gamma-Aminobutyric Acid; metabolism

The GABAB receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) activated by the most abundant inhibitory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system, γ-amino butyric acid (GABA). This receptor is involved in numerous physiological processes via the regulation of both GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses at either the pre- or post-synaptic level (1). Accordingly, GABAB receptors are involved in various types of epilepsy, in nociception and drug addiction, and in spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis (2). Although it has been pharmacologically described for twenty years, only in 1998 was the first GABAB receptor (GABAB1) cloned (3). It belonged to the class-III of the GPCR super family, together with the metabotropic glutamate (mGlu), the calcium sensing (CaS), and some pheromone and taste receptors (4). In addition to the typical GPCR heptahelical domain (HD), GABAB1 possesses a large extracellular domain (ECD), like most other class-III GPCRs (4). In contrast to the rhodopsin-like receptors (class-I GPCRs), the ligand binding site of class-III GPCRs is located within their large ECD, in the so-called Venus Fly-Trap Module (VFTM). Indeed, agonists bind within a cleft that separates the two lobes of the VFTM and stabilize a closed active conformation. This has been recently illustrated by the crystal structures of the mGlu1 ECD that have been solved both in the absence and presence of agonist (5), and confirmed in the case of GABAB1 by multiple mutagenesis studies (6–8).

However, to form a receptor able to efficiently activate G-proteins, GABAB1 need to be associated with a homologous protein called GABAB2 (9–13). GABAB receptor was then the first described obligatory heterodimeric receptor. Several studies unraveled some specific roles dedicated to each subunit. First, GABAB2 takes GABAB1 to the cell surface probably by masking a retention signal located in GABAB1 C-terminal tail (14–16). Secondly, GABAB1 VFTM, but not that of GABAB2, binds all known GABAB agonists and antagonists, whereas GABAB2 HD is critical for G protein activation (17–20). Third, there are complex allosteric interactions between the ECD and the HD of both subunits (20–22) leading to optimal agonist affinity and coupling efficacy.

Although the co-expression of both GABAB1 and GABAB2 appears to be required for an efficient activation of G-proteins, some studies report a possible functioning of one GABAB subunit independently of the other (9). (23). In support of a functional role of GABAB2 in the absence of GABAB1, homodimeric GABAB2 receptors have been observed at the surface of heterologous cells (24), and homodimeric GABAB2 HDs are capable of activating G-proteins (20, 21). Moreover, localization studies revealed that some neurons in the brain express much more mRNA of one subunit than of the other consistent with a possible role of homomeric GABAB receptors (25). Finally, GABAB1 may be able to activate intracellular pathways independently of G-proteins (23, 26–28). The identification of selective compounds acting on GABAB2 will probably help unravel this issue.

Within the last few years, allosteric modulators of class-III GPCRs have been identified for CaS and mGlu receptors (29–31). Such compounds act either as non-competitive antagonists (32–34), or as positive allosteric modulators (35–40). In each case, these compounds have been shown to bind within the HD of their targeted receptor (34, 41–43). They are also highly selective for one receptor subtype, in contrast to most of the ligand acting at the orthosteric site. Urwyler and coll. recently described the first GABAB specific positive allosteric modulators, CGP7930 and CGP13501 and more recently the compound GS39783 (44, 45). Their site of action was not identified, but according to what was known for the mGlu specific positive allosteric modulators and to the fact that GABAB2 coupled to G protein, we hypothesized that these compounds act in the GABAB2 HD (46).

In the present work, we not only demonstrate that CGP7930 indeed modulates the GABAB receptor by directly acting in the GABAB2 HD, but also that it activates the homomeric GABAB2 receptor, indicating that GABAB2 could be functional by itself. Moreover, CGP7930 also activates a truncated version of GABAB2 deleted of the ECD, demonstrating that this HD can behave like a rhodopsin-like receptor. These data bring much information on the mechanism of action of this GABAB positive modulator and reveal that GABAB2 selective drugs can be identified. Such drugs will be useful to better dissect the specific role of GABAB1 and GABAB2 in the brain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Aldehyde CGP13501 was synthetized according to FR2237870 patent and was subsequently reduced with sodium borohydride to afford CGP7930 (mp. 82–84°C, US4333868 patent 86°C).

CGP54626 was purchased from Tocris (Fisher-Bioblock, Illkrich, France). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), culture media and other solutions used for cell culture were from GIBCO-BRL-Life Technologies, Inc. (Cergy Pontoise, France). [3H]-myo-inositol (23.4 Ci/mol) was purchased from Perkin–Elmer Life Science (NEN) (Paris, France). All other reagents used were of molecular or analytical grade where appropriate.

Plasmids and site-directed mutagenesis

The plasmids encoding the wild-type and chimeric GABAB1a and GABAB2 subunits epitope tagged at their N-terminal ends (pRK-GABAB1a-HA, pRK-GABAB1a/2-HA, pRK-GABAB2/1-HA and pRK-GABAB2-HA or -cMyc), under the control of a CMV promoter, were previously described (16, 20). PRK-HD2 was generated by deletion of the sequence coding for the ECD in the pRK-GABAB2-HA plasmid, with the use of the MluI restriction site located just after the sequence coding for the HA tag and a MluI site created just after the proline residues at position 463 in GABAB2.

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% FCS and transfected by electroporation as described elsewhere (47, 48). Unless stated otherwise, 10.106 cells were transfected with plasmid DNA containing the coding sequence of the receptor subunits, and completed to total amount of 10 μg plasmid DNA with pRK6. For determination of inositol phosphate accumulation, the cells were also tranfected with the chimeric Gαqi9 G-protein which allows the coupling of the recombinant heteromeric GABAB receptor to PLC (47).

Measurement of inositol phosphate production

Determination of inositol phosphate (IP) accumulation in transfected cells was performed in 96-wells plates (0.2.106 cells/well) after over-night labeling with 3H-myo-inositols (0.5μCi/well) as already described (49). The stimulation was conducted for 30 minutes in a medium containing 10mM LiCl and the indicated concentration of agonist or antagonist. The reaction was stopped with a 0.1M formic acid solution. Supernatants were recovered and IP were purified by ion exchange chromatography using DOWEX AG1-X8 resin (Biorad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) in 96 well filter plates (ref: MAHVN4550 Millipore, Bedford, MA). Total radioactivity remaining in the membrane fractions was counted after treatment of cells with a solution containing 10% triton X-100 and 0.1N NaOH. Radioactivity was quantified using Wallac 1450 MicroBeta liquid scintillation counter. Data were expressed as IP/Membrane, meaning the amount of total IPs produced over the amount of radioactivity remaining in the membranes, multiplied by 100. Unless stated otherwise, all data are means ± sem of at least 3 independent experiments. The dose-response curves were fitted using the Kaleidagraph program and the following equation where the EC50 is the concentration of the compound necessary to obtain 50% of the maximal effect and nH is the Hill coefficient.

Anti-HA ELISA for quantification of cell surface expression

Twenty-four hours after transfection (10.106 cells, HA-tagged GABAB1 (2μg) and cMyc-tagged GABAB2 (2μg) subunits), cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then blocked with PBS + 5% FBS. After 30 minutes reaction with primary antibody (monoclonal anti-HA clone 3F10 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) at 0.5μg/mL) in the same buffer, the goat Anti-Rat antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) was applied for 30 minutes at 1μg/mL. After intense washes with PBS, secondary antibody was detected and quantified instantaneously by chemiluminescence using Supersignal® ELISA femto maximum sensitivity substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and a Wallac Victor2 luminescence counter.

GTP-γ-[35S] binding measurements

Cells were transfected using PolyFect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) under optimized conditions. Complex were formed using total amount of 8μg plasmid DNA with 60 μL of polyfect in 300 μL of serum free antibiotic free DMEM for 10 minutes and then added to cells at 40–60% confluence. According expression results, the amount of DNA is GABAB1 2μg, GABAB2 1μg, Gαo1c 2μg and pRK6 3μg for wild-type receptor. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were scraped in lysis buffer (15mM Tris, 2mM MgCl2, 0.3mM EDTA pH 7.4) and centrifuged twice. The pellet was solubilised in Tris (50mM) MgCl2 (3mM) buffer pH 7.4 using a potter. The GTP-γ-[35S] binding was performed in 96-wells filtration plates (ref: MAFCN0B50, Millipore, Bedford, MA) equilibrated with Tris (50mM) MgCl2 (5mM) pH7.4. 5μg of membrane preparation per wells were pre-incubated in 20μL with antagonist (15 minutes) and after with agonist (15 minutes). 60 μL of incubation buffer (50mM Tris, 1mM EDTA, 10μM GDP, 5mM MgCl2, 0.01mg/mL leupeptine, 100mM NaCl), and 20μL of H2O per well were added, and then, the plate was incubated one hour at 30°C. After vacuum filtration and plate filter drying, the radioactivity was measured using a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta liquid scintillation counter. The dose-response curves were fitted using the Kaleidagraph program and the following equation where the EC50 is the concentration of the compound necessary to obtain 50% of the maximal effect and nH is the Hill coefficient.

RESULTS

CGP7930 is a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAB receptor

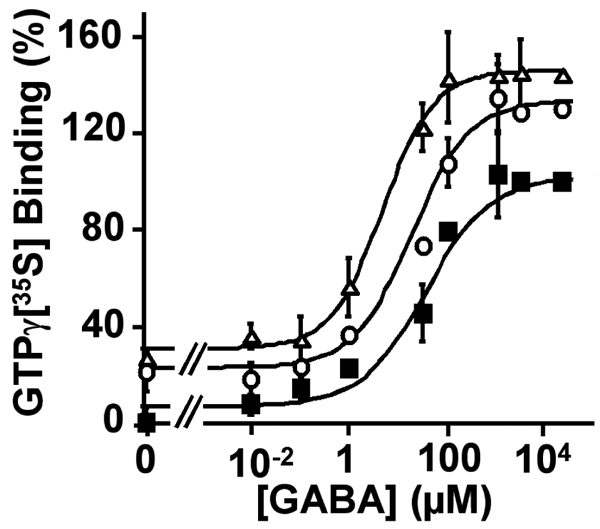

As previously described by Urwyler et al., CGP7930 increased both the affinity and the maximal effect (about 40%) of GABA in stimulating GTP-γ[35S] binding on Gαo-proteins (Fig. 1) (44). Dose-response curves indicate the EC50 for GABA was increased 3- and 10-fold in the presence of 0.1 and 1mM CGP7930, respectively (42.0 ± 11.0; 30.0 ± 7.5 and 4.7 ± 1.04 μM, in the absence or in the presence of 0.1mM and 1mM CGP7930, respectively). A small increase in the binding of GTP-γ[35S] binding was also observed in the absence of GABA, suggesting that CGP7930 may also be able to slightly activate the receptor. However, such an effect of CGP7930 could not be studied in details using this assay according to the high basal GTP-γ[35S] binding, and to the low signal to noise ratio of this assay (2 to 3 fold increase observed with a saturating GABA concentration).

Figure 1.

Concentration-response curves for GAB A on wild type GABAB receptor in the absence (■), or in the presence of 100 μM (○) or 1 mM (△) of CGP7930, generated from a GTP-γ[35S] binding assay. The GABA EC50 values determined in the absence, and in the presence of 100 μM or 1 mM CGP7930, were 42 μM, 30 μM and 4.7 μM, respectively. The data were expressed as the % of increase of GTP-γ[35S] binding above basal. The presented data are from one representative experiment among three experiments performed in triplicate.

Therefore, the effect of CGP7930 was further analyzed using an IP production assay which is supposed to give a higher signal to noise ratio. Indeed the GABAB receptor can efficiently activate PLC when co-expressed with the chimeric G-protein Gqi9 (47). As previously noticed, the IP assay is much more sensitive than the GTP-γ[35S] assay as indicated by the 100 fold lower EC50 value measured for GABA compare to the GTP-γ[35S] assay. This likely results from the large amplification of the signaling cascade between G-protein activation and IP formation.

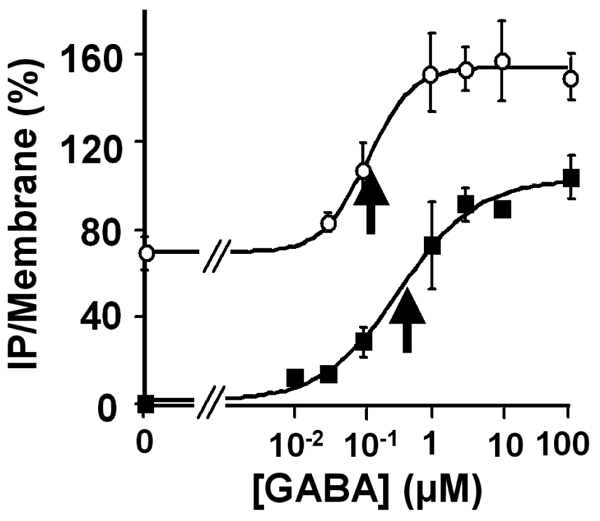

As observed with the GTP-γ[35S] assay, 100 μM CGP7930 increased GABA potency in stimulating IP formation 3 fold (EC50: 0.32 ± 0.10 μM and 0.11 ± 0.02 μM, in the absence and presence of 100 μM CGP7930, respectively), as well as the maximal effect (Fig. 2 and 3 A). The EC50 for this effect of CGP7930, as determined by increasing concentrations of this compound in the presence of a fixed concentration of GABA was similar to that determined by Urwyler et al. when using a IP-induced Calcium signal assay (18,9 ± 7,7 and 10 ± 0.1 μM respectively) (44).

Figure 2.

Concentration-response curves for GABA on wild type GABAB receptor, generated from a IP formation assay, in the absence (■), and in the presence of 100 μM of CGP7930 (○). The GABA EC50 values determined in the absence or in the presence of 100 μM CGP7930 were 0.32 μM and 0.11 μM, respectively. The arrows indicate the EC50 determined by the curve fits for the conditions without and with CGP7930 respectively. The results are % of the GABA-induced maximal effect on wild type receptor in the absence of CGP7930. The presented data are means of five experiments performed in triplicate.

Figure 3.

Effect of the CGP7930 (100 μM) and potentiation of the GABA (1 μM) induced-stimulation of IP formation in absence (A) and in presence (B) of 1 μM of the GABB as receptor specific competitive antagonist CGP54626. (C) Maximal effects on IP formation obtained with 1 mM of GABA or 1 mM of CGP7930. The presented data are from one representative experiment among three experiments performed in triplicate.

However, in this assay, CGP7930 also clearly stimulated IP production even in the absence of added GABA, further suggesting that the CGP7930 could be a GABAB partial agonist (Fig. 2 and 3).

CGP7930 is a partial agonist of the GABAB receptor

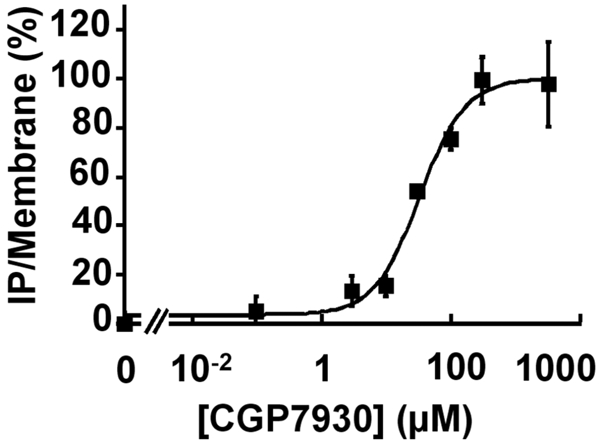

Additional experiments were performed in order to demonstrate that CGP7930 directly activates the GABAB receptor. First, CGP7930 alone did not induce IP formation in pRK6 and Gqi9 transfected control cells, nor in cells co-expressing mGlu5, demonstrating that IP production did not result from a direct action on either the transfected G-protein or PLC (data not shown). Second, the observed stimulation of IP production by CGP7930 (Fig. 3A), is dose-dependent with an EC50 similar to that observed for the potentiating effect (32.5 ± 7.2 μM; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Concentration-response curves for CGP7930 generated from the IP formation assay on wild type GABAB receptor. The EC50 value determined for GABA effect was 32.55 ± 7.23 μM. Results are expressed as the % of the CGP7930-induced maximal effect The presented data are from one representative experiment among eight experiments performed in triplicate.

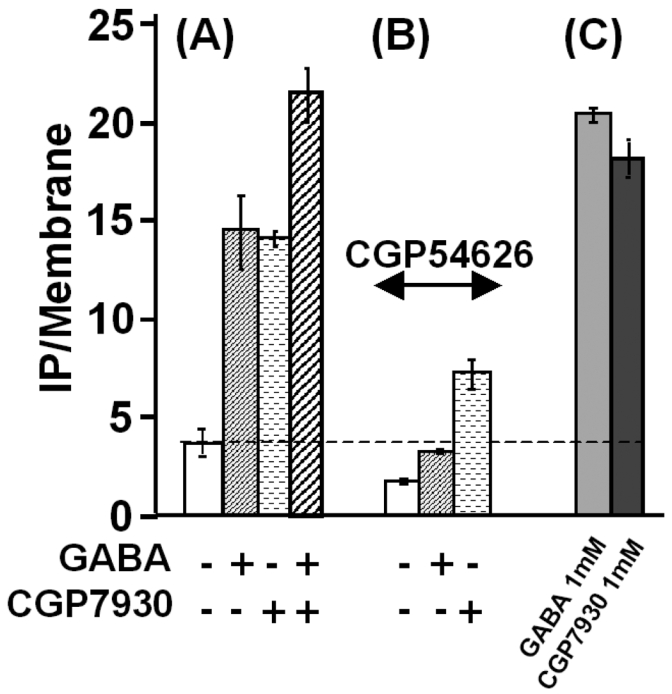

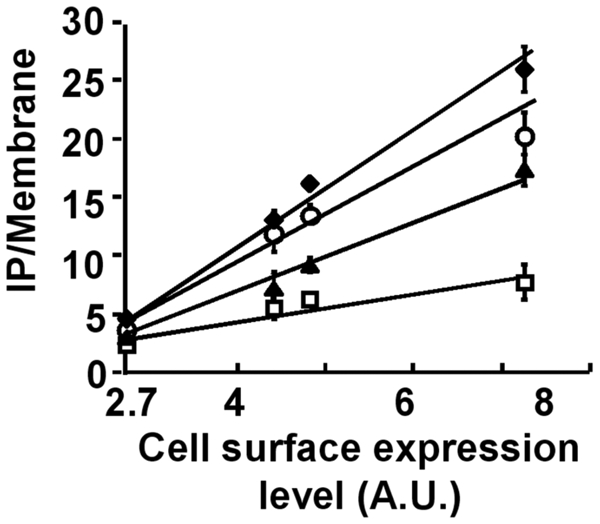

As we could not exclude that the observed effect of CGP7930 was du to over-expression of the receptors, we decided to examine the effect of CGP7930 at different receptor expression levels. To that aim the effect of saturating concentrations of GABA or CGP7930 (1mM) were measured in cells transfected with increasing amount of GABAB1- and GABAB2-expressing plasmids (Fig. 5). The expression levels of heteromeric GABAB receptor were determined using ELISA performed on intact cells with an anti-HA antibody labeling the N-terminal HA-tagged GABAB1 subunit. As shown in Fig. 5, the maximal agonist activity of CGP7930 was always lower than the maximal GABA activity, and of course than the maximal activity induced by CGP7930 together with GABA, indicating that CGP7930 was only a partial agonist.

Figure 5.

Maximal IP formation response depending of the cell surface receptor expression. IP formation was measured in cells expressing various amounts of the GABAB heterodimer without drug (□), or in presence of 1 mM of CGP7930 (▲), or of 1 mM of GABA (○), or with both drugs (◆). The receptor expression levels are below the level inducing a saturation of the transduction machinery, allowing the observation of the increased maximal response induced by incubation with both compounds, GABA and CGP7930. A.U. stands for Arbitrary Units. The presented data are from one representative experiment among four experiments performed in triplicate.

The heptahelical domain of GB2 is required for the action of CGP7930

In order to identify the site of action of CGP7930, we first examined whether the stimulatory effect was inhibited by the competitive antagonist CGP54626. As shown in Fig. 3B, high concentration of (1 μM, about 250 fold its affinity) totally antagonized the effect of GABA, both compounds binding in the same site in the ECD of GABAB1. However, CGP54626 did not completely inhibited (57.5 ± 0.5 % of inhibition) the effect of CGP7930. This suggested that CGP7930 did not bind in the orthosteric site where GABA and competitive antagonists bind within the GABAB1 ECD, but in another domain, in an allosteric site. Thus, CGP54626 probably allosterically inhibited the CGP7930 effect.

GABAB heterodimers can be considered as the association of 4 distinct domains (ECD1, ECD2, HD1 and HD2) that correspond to the ECD and HD of GABAB1 and GABAB2 subunits, respectively. To identify which of these domains is required for the effect of CGP7930 its action on various combinations of chimeric and mutated subunits was examined. The chimeric subunits used were GABAB1/2 and GABAB2/1, in which the entire ECD have been swapped between GABAB1 and GABAB2 (20).

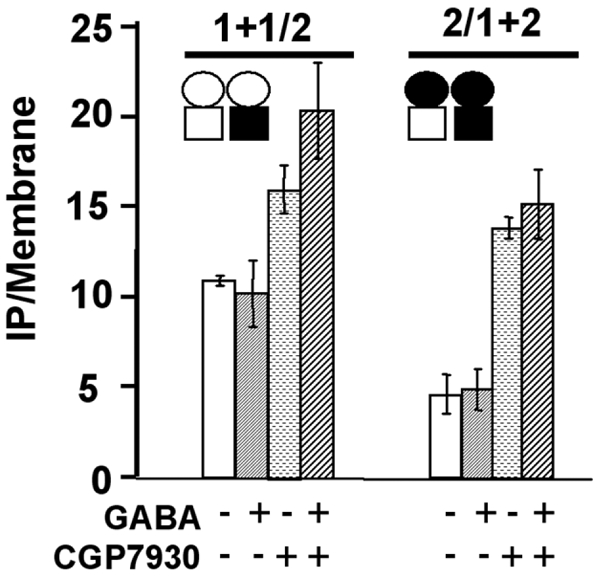

The GABAB1/2 was expressed with GABAB1 to form a receptor that does not contain the ECD2, and vice-versa, GABAB2/1 was expressed with GABAB2 to form a receptor devoid of ECD1. Both combinations have already been shown to be expressed at the cell surface and to form heteromeric complexes (20). Although they are not sensitive to GABA, both activate Gqi9, as illustrated by the high constitutive IP formation measured in cells expressing these subunit combinations (20). As shown in Fig. 6, CGP7930 stimulated IP production in cells expressing either combination (Fig. 6, compare lanes 3 and 6). Accordingly, none of the ECD was required for the effect of CGP7930. Then, although we could not rule out that CGP7930 could act similarly on both ECD1 and ECD2 and that only one ECD would be enough for the effect of CGP7930, the more likely possibility was that CGP7930 acts in the HD of either GABAB1 or GABAB2.

Figure 6.

The ECD of GABAB1 or GABAB2 are not required for the effect of CGP7930. Effect of the CGP7930 (100 μM) in presence or no of GABA (1 mM) on chimeric receptor formed by the subunit combination GABAB1 + GABAB1/2 and GABAB2 + GABAB2/1, in which the ECD of GABAB2 and that of GABAB1 is missing respectively. 1 + 1/2 stands for the subunit combinations GABAB1 + GABAB1/2, and 1/2+2 stands for the subunit combination GABAB2/1 + GABAB2. CGP7930 was still able to stimulate the IP formation in cells expressing either combination, indicating that the ECD of GABAB1 or GABAB2 subunits are not necessary for the effect of CGP7930. The empty circle represents the ECD of GABAB1 and the black circle the ECD of GABAB2, and the empty square represents the HD of GABAB1 and the black square the HD of GABAB2. The presented data are means of three experiments performed in triplicate.

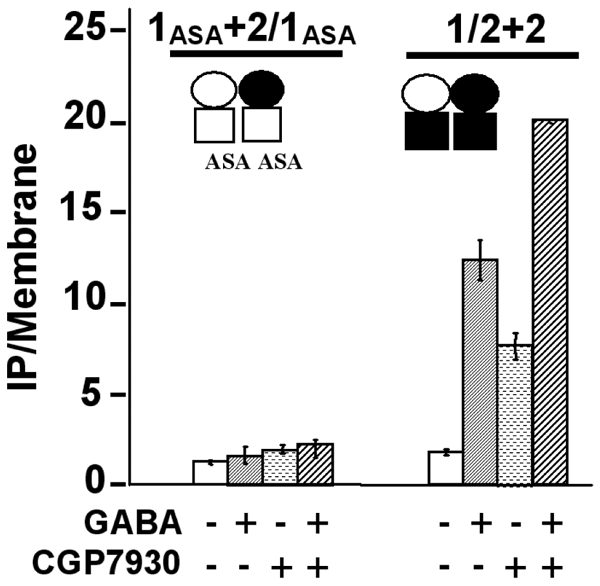

In order to determine which HD could be the site of action of CGP7930, the effect of CGP7930 was analyzed on the combinations GABAB1 + GABAB2/1 and GABAB2 + GABAB1/2. The first combination possessed only HD1 and not HD2, whereas the second possessed HD2 only and not HD1 (Fig. 7). In order to allow the correct expression of both GABAB1 and GABAB2/1 at the cell surface, the ER retention signal RSR located in the C-terminal tail of these subunits was mutated into ASA (20). Although the combination GABAB1 + GABAB2/1 was not activated by GABA, whereas the combination GABAB2 + GABAB1/2 was, both combinations were similarly expressed at the cell surface ((20) and data not shown). As shown in Fig. 7, CGP7930 stimulated the combination containing only HD2 (4 fold increase of the IP production, from 4.7 to 13.8 normalized cpm in the absence and presence of 100μM CGP7930, respectively), but was devoid of activity on that possessing HD1 only. Taken together, these data illustrated the requirement of HD2 for the partial agonist activity of CGP7930 in the GABAB heteromer. However, because GABAB1 cannot activate the G protein by itself, one can not exclude that CGP7930 bound to GABAB1 but failed at allowing it to stimulate G proteins.

Figure 7.

The HD of GABAB2 is required for the effect of CGP7930. The effect of the CGP7930 (100 μM) was examined, in presence or not of GABA (1 mM), on chimeric receptors formed by the subunit combination GABAB1ASA + GABAB2/1ASA and GABAB2 + GABAB1/2, in which the HD of GABAB2 and that of GABAB1 is missing respectively. In these combinations, the heterodimeric association of the ECD is conserved, but in contrast, the HD are identical in each combination, displaying then a homomeric HD association. 1ASA+2/1ASA stands for the subunit combinations GABABASA + GABAB2/1ASA, and 1/2+2 stands for the subunit combination GABAB1/2 + GABAB2. The empty circle represents the ECD of GABAB1 and the black circle the ECD of GABAB2, and the empty square represents the HD of GABAB1 and the black square the HD of GABAB2. The CGP7930 stimulated only the combination of subunits possessing the HD of GABAB2, indicating that the HD of GABAB1 was not necessary, in contrast to the HD of GABAB2. The presented data are means of three experiments performed in triplicate.

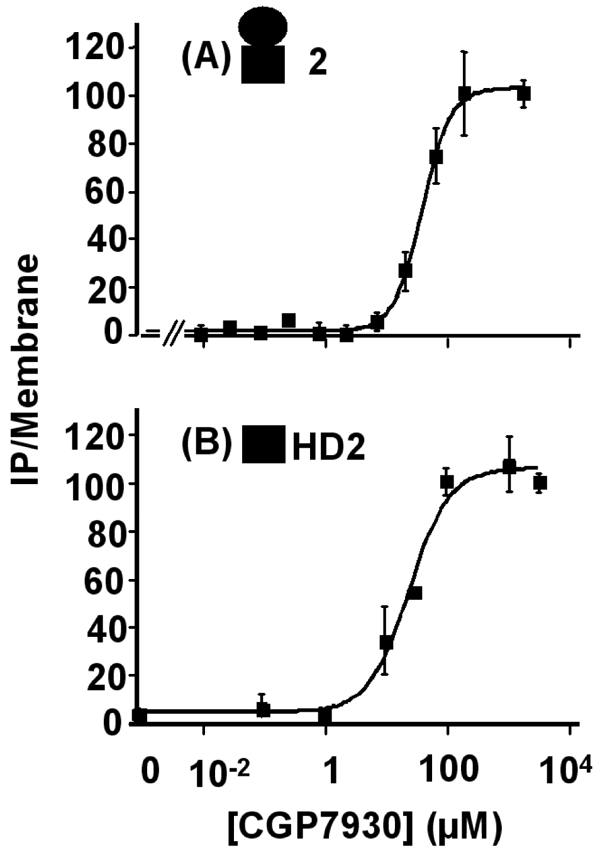

CGP7930 activated GABAB2 in the absence of GABAB1

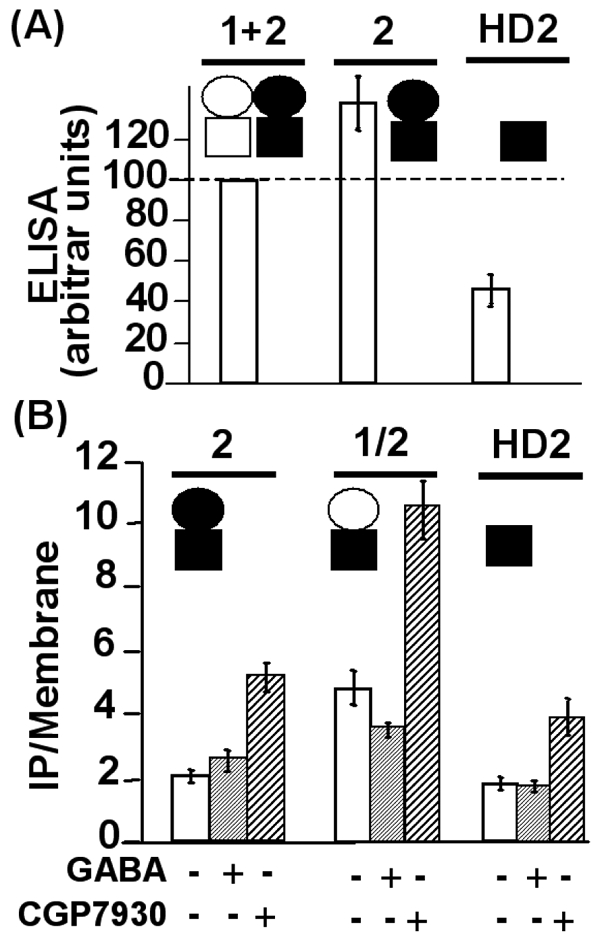

As mentioned above, GABAB2 possesses sufficient molecular determinants for G-protein activation (17–20). Even when transfected alone, GABAB2 was highly expressed at the HEK293 cell surface (Fig. 8A), allowing us to examine whether CGP7930 could activate this subunit expressed alone. Indeed, whereas GABA is devoid of activity on GABAB2, CGP7930 increased IP production 3 fold (Fig. 8B) with an EC50 of 57.1 ± 3.8 μM (Fig. 9). A similar effect of CGP7930 was observed with the chimeric subunit GABAB1/2, even though GABA was inactive (Fig. 8A and B). This confirms that the HD of GABAB2 is crucial for the CGP7930 effect. However, it is still possible that CGP7930 requires the presence of an ECD, either that of GABAB1 or GABAB2, to turn on the GABAB2 HD.

Figure 8.

A. Cell surface expression of the wild type GABAB receptor, the GABAB2 subunit alone and the HD2 construct. Using the ELISA procedure, the expression of the different proteins was determined for each condition and normalized as a percentage of the wild type GABAB receptor cell surface expression. B. CGP7930 (100 μM) increased the IP production in cells expressing only the HD of GABAB2. 2, 1/2, and HD2 stand for GABAB2, GABAB1/2 and the HD of GABAB2 respectively. The empty circle represents the ECD of GABAB1 and the black circle the ECD of GABAB2, and the black square the HD of GABAB2. CGP7930 increased IP formation in cells expressing either the GABAB2 subunit alone or the chimeric subunit GABAB1/2. Moreover, the HD of GABAB2 expressed alone was stimulated by CGP7930, confirming that it is enough for the effect of CGP7930. The presented data are means of four to seven experiments performed in triplicate.

Figure 9.

Concentration-response curves for CGP7930 generated from the IP formation assay on GABAB2 subunit alone. (A), and on the HD of GABAB2 alone (B). The results are % of the CGP7930-induced maximal effect on each construct. The EC50 were 57.1 ± 3.8 and 64.7 ± 38.4 μM in cells expressing GABAB2 or the HD of GABAB2, respectively. The black circle represents the ECD of GABAB2, and the black square the HD of GABAB2. The presented data are from representative experiments among four experiments performed in triplicate.

CGP7930 activated GABAB2 HD (HD2) expressed alone

According to the data described above, it appeared that CGP7930 could activate GABAB2 by a direct action in its HD. Thus, we looked for the action of CGP7930 on the HD of GABAB2 alone. Indeed, we have recently shown that the HD of mGlu5 receptor could be expressed alone and could be directly activated by a positive allosteric modulator of this receptor (49). We therefore generated a truncated version of GABAB2 lacking the large ECD (Fig. 8). Thanks to the presence of a signal peptide and of a HA tag inserted at the N-terminus, HD2 was found at the cell surface, although at a lower level than the wild-type subunit (30% of the wild type Fig. 8A)). On cells expressing HD2, CGP7930 increased IP production more than two folds, with an EC50 of 64.8 ± 38.7 μM (Fig. 9). These data showed that CGP7930 directly stabilizes an active conformation of the GABAB2 HD, and can be considered as a first GABAB2 ligand.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we explored the mechanism of action of CGP7930, one of the first described positive allosteric modulators of the GABAB receptor (44). Using both GTP-γ[35S] binding and IP production assays, that reflect the activation of Gαo and Gαqi9 respectively, we confirmed the positive allosteric action of CGP7930. However, using the more sensitive IP assay - i.e. activation of PLC via Gαqi9 - CGP7930 was also found to directly activate the GABAB receptor though with a low efficacy. The action of CGP7930 on various combinations of wild type and chimeric subunits, led us to propose that CGP7930 activated HD2 within the heteromer. This proposal was then directly demonstrated, as we showed that CGP7930 acted as an agonist of HD2 expressed alone, demonstrating this domain of the GABAB receptor behaved like a rhodopsin-like receptor. It is noteworthy that even if CGP7930 could bind to the HD of GABAB1, it would not induced G protein activation, as we never observed any activation of the recombinant G-proteins by GABAB receptors lacking HD2 (17,19,20).

CGP7930, a partial agonist of the GABAB receptor

Not only could CGP7930 potentiate the effect of GABA, as previously reported by others (44), but it could also directly activate the wild-type receptor. This effect occured in a similar range of concentration as those observed for the potentiating effect, and various arguments excluded the possibility of a potentiation of the effect of a possible endogenous agonist present in the assay medium. Indeed, the effect of CGP7930 was not fully inhibited by a competitive antagonist. Moreover, the effect of CGP7930 could still be observed on various mutated GABAB receptors not sensitive to GABA.

Since CGP7930 activated GABAB2 in the absence of GABAB1, then the agonist effect observed could well be the consequence of some GABAB2 subunits not associated with GABAB1. Although this possibility can not be firmly excluded, we think it is unlikely since we and others observed that in heterologous systems GABAB2 was less expressed than GABAB1 (8,50). Accordingly, it is very unlikely that there was enough isolated GABAB2 subunits (either in a monomeric or homodimeric form) in cells transfected with both GABAB1 and GABAB2 to generate a CGP7930-induced response higher than that observed in cells expressing GABAB2 only.

Of interest, CGP7930 activated not only the heteromeric GABAB receptor and the GABAB2 subunit expressed alone, but also a GABAB2 subunit deleted of its ECD. Moreover, all these effects were observed in the same range of concentration of CGP7930 (with very similar EC50 values). This observation clearly indicates that neither GABAB2 ECD nor the GABAB1 are required for the agonist activity of CGP7930. Also, this further demonstrates that agonist binding is not required for CGP7930 interaction with HD2.

On a possible allosteric control of CGP7930 effect

The affinity of GABA on the ECD of GABAB1 ass allosterically regulated by the other domains of the heteromeric GABAB receptor, like the ECD of GABAB2. We recently hypothesized that this effect was probably due to the relief by the GABAB2 ECD of an inhibitory action of the GABAB1 HD on the GABAB1 ECD (22). Accordingly, one would expect that the affinity of CGP7930 in the HD of GABAB2 would also be under the allosteric control of the other domains of the heteromeric complex. The EC50 of CGP7930 on the wild type receptor, on GABAB2 or on HD2 were quite similar, whether the agonist effect or the potentiating effect of CGP7930 was measured. This suggests that CGP7930 affinity was not as dependent as GABA affinity on the specific state of the other domains. Alternatively, within this range of concentration tested, CGP7930 may only bind and exert its effect on receptors in a specific state. The identification of radioactive compounds interacting at the same site than CGP7930 would be required to further study this point.

However, the antagonist CGP54626 that likely stabilizes the inactive open state of GABAB1 ECD, partly inhibited the agonist effect of CGP7930 on the wild-type receptor. Such an effect was not observed on the GABAB2 subunit expressed alone or on HD2. Then this demonstrated that the action of CGP7930 was dependent of the specific state of the GABAB1 ECD. To our actual knowledge on the mechanism of activation of the GABAB receptor, GABA binding in the VFT of GABAB1 leads to the closure of the VFT, and to a possible re-orientation of the dimer of VFTs. As a consequence, this stabilizes the active conformation of the dimer of HDs. The competitive antagonist like CGP54626 is expected to prevent the closure of the GABAB1 VFT, and thus to prevent the stabilization of the active state of the HD dimer by agonists. According to this model, any drug directly stabilizing the dimer of HDs will also stabilize the active conformation of the dimer of VFTs. In agreement with this proposal, CGP7930 increased agonist affinity. Due to allosteric coupling between the dimer of VFTs and the dimer of HD, locking the dimer of VFTs in the inactive state by a competitive antagonist, are expected to make more difficult the change in conformation of the dimer of HDs required for its activation. This is expected to decrease the effect of CGP7930, as observed here.

CGP7930 as an activator of the GABAB2 HD

As recently reported for mGlu5 (49), the HD of GABAB2 could be expressed as a membrane protein at the cell surface in HEK293 cells. Although the mGlu5 truncated receptor displayed constitutive activity, no such activity could be detected with GABAB2. This was in agreement with the higher constitutive activity measured with mGlu5 compared to GABAB receptor (51,52). However, in both cases, these HDs were activated by positive allosteric regulators, CGP7930 and DFB for GABAB2 and mGlu5 HDs, respectively. This shows that, even though class-III and class-I rhodopsin-like GPCRs diverged early during evolution, their HDs still possess common structural properties and likely share similar activation mechanism.

Whether GPCRs function as monomer or dimers is a matter of intense debate in the field (53–55). However, in the case of class-III GPCRs it is well accepted that the dimeric nature of these receptors is crucial for the intra-molecular transduction -i.e. transfer of information from the agonist binding domain to the heptahelical G-protein activating domain (4). However, whether a dimeric nature of the HD of these receptors is necessary for the agonist effect of positive allosteric modulators is not known. Obviously, the demonstration that HDs of class-III GPCRs can function like class-I GPCRs will help unravel this important issue.

A model for the action of CGP7930 on the GABAB receptor

We recently proposed a model for the functioning of class-III GPCRs (56). This model integrated our common view of the functioning of Venus Fly-Trap modules, meaning the binding of the ligand in the cleft between the two lobes of the ECD, and the stabilization of a closed state by agonists, or prevention of the closure of such a domain upon antagonist binding. Moreover, our model takes into account the putative mechanism of activation of the HD, with the existence of at least two states, active and inactive, the equilibrium between these two states being under the control of the specific conformation of the ECD. As discussed in this paper, this model fits very nicely with a series of specific properties of class-III GPCRs. For example, this model provides a reasonable explanation for the lack of inverse agonist activity of competitive antagonists of mGluRs, whereas non-competitive antagonists interacting in the HD were found to be inverse agonists (56).

In this model, we proposed two options to explain the effect of positive allosteric modulators acting in the HD of class-III GPCRs. A first possibility is that such compounds act by stabilizing the active state of the HD, and as a consequence stabilize the active state of the binding domain therefore increasing agonist affinity. According to this proposal, such positive allosteric modulators were expected to also activate with a low efficacy the full-length receptor. This nicely fits with our observation that CGP7930 acted both as an activator and as a positive allosteric modulator of the full-length GABAB receptor. The second possibility was that the positive modulators acted by increasing the allosteric coupling between the active ECD and the HD, rather than by directly activating the HD. According to the second possibility, the positive modulator directly activated neither the full-length receptor, nor the HD. Our recent observation that the mGlu5 positive modulator, DFB (3,3′-Difluorobenzaldazine), did not activate the full-length receptor, but acted as a full agonist on the receptor deleted of its ECD, did not fit with any of these two possibilities. Accordingly, a more complex model involving 3 states of the mGlu5 HD was proposed (49). This was based on the recognized three states of rhodopsin (57,58) Such an observation provides evidence for a different activation mechanism of GABAB receptors and the other Class-III GPCRs, such as mGluRs. Indeed, although these two types of receptors share sequence similarities, the GABAB receptor subunits lack the cystein-rich domain that interconnects the ECD to the HD in the mGlu-like receptors. Further studies will be necessary to better clarify the specific properties of both types of class-III GPCRs.

Conclusion

The main observation of this study is that it is possible to identify compounds acting on the GABAB2 subunit. As discussed above, such compounds will be useful to elucidate the activation mechanism of such a complex GABAB heteromeric receptor. In addition, as pointed out in our introduction, it is well recognized that the vast majority of GABAB1 and GABAB2 subunits associate with each other to form a functional GABAB receptor in the brain. However, some observations suggest that either GABAB1 or GABAB2 could be active on their own, or in association with another type of subunit. Our data show that it should be possible to identify compounds acting on GABAB2 specifically. Such compounds will help unravel the possible function of this subunit in the brain.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs. Julie Kniazeff, Cyril Goudet, Philippe Rondard, and Thierry Durroux for constructive discussions and critical reading of manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the CNRS, the Action Incitative “Molécules et Cibles Thérapeutiques” from INSERM, CNRS and the French government (J.P.P.), and by Addex Pharmaceuticals (Geneva, Switzerland).

References

- 1.Billinton A, Ige AO, Bolam JP, White JH, Marshall FH, Emson PC. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:277–282. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01815-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couve A, Moss SJ, Pangalos MN. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:296–312. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaupmann K, Huggel K, Heid J, Flor PJ, Bischoff S, Mickel SJ, McMaster G, Angst C, Bittiger H, Froestl W, Bettler B. Nature. 1997;386:239–246. doi: 10.1038/386239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pin JP, Galvez T, Prezeau L. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98:325–354. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunishima N, Shimada Y, Tsuji Y, Sato T, Yamamoto M, Kumasaka T, Nakanishi S, Jingami H, Morikawa K. Nature. 2000;407:971–977. doi: 10.1038/35039564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galvez T, Urwyler S, Prezeau L, Mosbacher J, Joly C, Malitschek B, Heid J, Brabet I, Froestl W, Bettler B, Kaupmann K, Pin JP. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:419–426. doi: 10.1124/mol.57.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kniazeff J, Galvez T, Labesse G, Pin JP. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7352–7361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07352.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kniazeff J, Saintot PP, Goudet C, Liu J, Charnet A, Guillon G, Pin JP. J Neuroscience. 2004;24:370–377. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3141-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaupmann K, Malitschek B, Schuler V, Heid J, Froestl W, Beck P, Mosbacher J, Bishoff S, Kulik A, Shigemoto R, Karschin A, Bettler B. Nature. 1998;396:683–687. doi: 10.1038/25360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuner R, Köhr G, Grünewald S, Eisenhardt G, Bach A, Kornau HC. Science. 1999;283:74–77. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng GY, Clark J, Coulombe N, Ethier N, Hebert TE, Sullivan R, Kargman S, Chateauneuf A, Tsukamoto N, McDonald T, Whiting P, Mezey E, Johnson MP, Liu Q, Kolakowski LF, Jr, Evans JF, Bonner TI, O’Neill GP. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7607–7610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White JH, Alan W, Main MJ, Green A, Fraser NJ, Disney GH, Barnes AA, Emson P, Foord SM, Marshall FH. Nature. 1998;396:679–682. doi: 10.1038/25354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones KA, Borowsky B, Tamm JA, Craig DA, Durkin MM, Dai M, Yao WJ, Johnson M, Gunwaldsen C, Huang LY, Tang C, Shen Q, Salon JA, Morse K, Laz T, Smith KE, Nagarathnam D, Noble SA, Branchek TA, Gerald C. Nature. 1998;396:674–679. doi: 10.1038/25348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calver AR, Robbins MJ, Cosio C, Rice SQ, Babbs AJ, Hirst WD, Boyfield I, Wood MD, Russell RB, Price GW, Couve A, Moss SJ, Pangalos MN. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1203–1210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01203.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Margeta-Mitrovic M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Neuron. 2000;27:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pagano A, Rovelli G, Mosbacher J, Lohmann T, Duthey B, Stauffer D, Ristig D, Schuler V, Heid J, Meigel I, Lampert C, Stein T, Prézeau L, Pin JP, Froestl W, Kuhn R, Kaupmann K, Bettler B. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1189–1202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01189.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Margeta-Mitrovic M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14649–14654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251554498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duthey B, Caudron S, Perroy J, Bettler B, Fagni L, Pin JP, Prezeau L. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3236–3241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108900200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robbins MJ, Calver AR, Filippov AK, Hirst WD, Russell RB, Wood MD, Nasir S, Couve A, Brown DA, Moss SJ, Pangalos MN. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8043–8052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08043.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galvez T, Duthey B, Kniazeff J, Blahos J, Rovelli G, Bettler B, Prezeau L, Pin JP. Embo J. 2001;20:2152–2159. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Havlickova M, Prezeau L, Duthey B, Bettler B, Pin JP, Blahos J. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:343–350. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J, Maurel D, Etzol S, Brabet I, Pin J-P, Rondard P. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313639200. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin SC, Russek SJ, Farb DH. Molecular cellular Neurosci. 1999;13:180–191. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurel D, Kniazeff J, Mathis G, Trinquet E, Pin J-P, Ansanay H. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.02.013. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calver AR, Medhurst AD, Robbins MJ, Charles KJ, Evans ML, Harrison DC, Stammers M, Hughes SA, Hervieu G, Couve A, Moss SJ, Middlemiss DN, Pangalos MN. Neuroscience. 2000;100:155–170. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vernon E, Meyer G, Pickard L, Dev K, Molnar E, Collingridge GL, Henley JM. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;17:637–645. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White JH, McIllhinney RA, Wise A, Ciruela F, Chan WY, Emson PC, Billinton A, Marshall FH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13967–13972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240452197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nehring RB, Horikawa HP, El Far O, Kneussel M, Brandstatter JH, Stamm S, Wischmeyer E, Betz H, Karschin A. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35185–35191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pin JP, Acher F. Cur Drug Targets. 2002;1:297–317. doi: 10.2174/1568007023339328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gasparini F, Kuhn R, Pin JP. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(01)00119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu J, Spiegel AM. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:282–288. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carroll FY, Stolle A, Beart PM, Voerste A, Brabet I, Mauler F, Joly C, Antonicek H, Bockaert J, Müller T, Pin JP, Prézeau L. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:965–973. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Litschig S, Gasparini F, Rueegg D, Stoehr N, Flor PJ, Vranesic I, Prezeau L, Pin JP, Thomsen C, Kuhn R. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:453–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagano A, Ruegg D, Litschig S, Stoehr N, Stierlin C, Heinrich M, Floersheim P, Prezeau L, Carroll F, Pin JP, Cambria A, Vranesic I, Flor PJ, Gasparini F, Kuhn R. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33750–33758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaffhauser H, Rowe BA, Morales S, Chavez-Noriega LE, Yin R, Jachec C, Rao SP, Bain G, Pinkerton AB, Vernier JM, Bristow LJ, Varney MA, Daggett LP. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:798–810. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.4.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson MP, Baez M, Jagdmann GE, Jr, Britton TC, Large TH, Callagaro DO, Tizzano JP, Monn JA, Schoepp DD. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3189–3192. doi: 10.1021/jm034015u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knoflach F, Mutel V, Jolidon S, Kew JN, Malherbe P, Vieira E, Wichmann J, Kemp JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13402–13407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231358298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marino MJ, Williams DL, Jr, O’Brien JA, Valenti O, McDonald TP, Clements MK, Wang R, DiLella AG, Hess JF, Kinney GG, Conn PJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13668–13673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835724100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathiesen JM, Svendsen N, Brauner-Osborne H, Thomsen C, Ramirez MT. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:1026–1030. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Brien JA, Lemaire W, Chen TB, Chang RS, Jacobson MA, Ha SN, Lindsley CW, Schaffhauser HJ, Sur C, Pettibone DJ, Conn PJ, Williams DL., Jr Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:731–740. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malherbe P, Kratochwil N, Knoflach F, Zenner MT, Kew JN, Kratzeisen C, Maerki HP, Adam G, Mutel V. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8340–8347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malherbe P, Kratochwil N, Zenner MT, Piussi J, Diener C, Kratzeisen C, Fischer C, Porter RH. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:823–832. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.4.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lavreysen H, Janssen C, Bischoff F, Langlois X, Leysen JE, Lesage AS. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1082–1093. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urwyler S, Mosbacher j, Lingenhoehl K, Heid J, Hofstetter K, Froestl W, Bettler B, Kaupmann K. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:963–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Urwyler S, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Mosbacher J, Lampert C, Froestl W, Koller M, Kaupmann K. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:322–330. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pin JP, Parmentier ML, Prezeau L. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:881–884. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.5.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franek M, Pagano A, Kaupmann K, Bettler B, Pin JP, Blahos J. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1657–1666. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brabet I, Parmentier ML, Bockaert J, Acher F, Pin JP. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goudet C, Gaven F, Kniazeff J, Vol C, Liu J, Cohen-Gonsaud M, Acher F, Prezeau L, Pin JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:378–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304699101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Couve A, Filippov AK, Connolly CN, Bettler B, Brown DA, Moss SJ. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26361–26367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joly C, Gomeza J, Brabet I, Curry K, Bockaert J, Pin JP. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3970–3981. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03970.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grunewald S, Schupp BJ, Ikeda SR, Kuner R, Steigerwald F, Kornau HC, Kohr G. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:1070–1080. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.5.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, Le Trong I, Teller DC, Okada T, Stenkamp RE, Yamamoto M, Miyano M. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bouvier M. Nature Rev. 2001;2:274–286. doi: 10.1038/35067575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chabre M, Cone R, Saibil H. Nature. 2003;426:30–31. 31. doi: 10.1038/426030b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parmentier ML, Prezeau L, Bockaert J, Pin JP. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:268–274. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joubert L, Claeysen S, Sebben M, Bessis AS, Clark RD, Martin RS, Bockaert J, Dumuis A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25502–25511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Okada T, Enrnst O, Palczewski K, Hofmann KP. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:318–324. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]