Abstract

Cyclin D1 expression is jointly regulated by growth factors and cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix in many cell types. Growth factors are thought to regulate cyclin D1 expression because they stimulate sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activity. However, we show here that growth factors induce transient ERK activity when added to suspended fibroblasts and sustained ERK activity only when added to adherent fibroblasts. Cell attachment to fibronectin or anti-α5β1 integrin is sufficient to sustain the ERK signal and to induce cyclin D1 in growth factor-treated cells. Moreover, when we force the sustained activation of ERK, by conditional expression of a constitutively active MAP kinase/ERK kinase, we overcome the adhesion requirement for expression of cyclin D1. Thus, at least in part, fibroblasts are mitogen and anchorage dependent, because integrin action allows for a sustained ERK signal and the expression of cyclin D1 in growth factor-treated cells.

INTRODUCTION

As cells progress through G1 phase, they undergo a proscribed series of molecular events involving cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks), and cdk inhibitors (Hunter and Pines, 1994; Sherr, 1994; Sherr and Roberts, 1995). Two cyclin-cdk activities, cyclin D-cdk4/6 and cyclin E-cdk2, are required for progression through G1 phase. Cyclin D1-cdk4/6 controls cell cycle progression by phosphorylating the retinoblastoma protein (pRb); this event allows for the release of E2F and the induction of E2F-regulated genes such as cyclin A (Weinberg, 1995). Cyclin D1-cdk4/6 complexes also sequester cdk inhibitors in the cip/kip family (p27kip1 in particular), and this effect contributes to the activation of cyclin E-cdk2.

Induction of cyclin D1 is the rate-limiting step in formation of active cyclin D-cdk4/6 complexes for many cell types. There is a close correlation between activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) subfamily of MAP kinases and induction of the cyclin D1 promoter (Albanese et al., 1995, Lavoie et al. 1996). A sustained activation of ERKs is required for cell cycle progression through G1 phase (Meloche et al., 1992), consistent with a recent study linking sustained ERK activity to the induction of cyclin D1 (Weber et al., 1997). These reports indicate that growth factors stimulate sustained ERK activity when added to quiescent adherent cells, and this is thought to account for their ability to induce the expression of cyclin D1. However, we and others have shown that growth factors do not induce cyclin D1 if cells are stimulated in the absence of an extracellular matrix (ECM) (Böhmer et al., 1996; Zhu et al., 1996; Day et al., 1997; Radeva et al., 1997; Resnitzky, 1997; Brugarolas et al., 1998).

Cell adhesion to the ECM is largely mediated by the integrin family of transmembrane receptors. Although integrins do not possess intrinsic enzymatic activity, they do associate with or activate a number of cytosolic kinases, and it is thought that these kinases initiate many of the downstream integrin signaling events. One integrin-mediated signaling event that has attracted much attention recently is the activation of ERKs. The ERKs can be activated independently by integrins and by growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). Several studies have identified signal transduction pathways that mediate the activation of ERKs by integrins; the present models place different degrees of importance on focal adhesion kinase, p130cas, shc, ras, rho-family GTPases, and PKC, as well as on the specific α subunit in the integrin heterodimer (Schwartz et al., 1995; Giancotti, 1997; Howe et al., 1998; Schlaepfer and Hunter, 1998). Other studies have reported that integrin and RTK signals synergize to determine the percent of ERK that is activated (Miyamoto et al., 1996; Lin et al., 1997; Renshaw et al., 1997; Moro et al., 1998; Short et al., 1998; Aplin and Juliano, 1999). Some of these studies indicate that the synergism results from integrin-dependent changes in phosphorylation of growth factor RTKs (Miyamoto et al., 1996; Moro et al., 1998), whereas others fail to detect this and map the effect within the downstream signaling cascade (Lin et al., 1997; Short et al., 1998). Still others emphasize the importance of a partial integrin-dependent organization of the cytoskeleton (Aplin and Juliano, 1999). However, all of these studies, including our own (Zhu and Assoian, 1995), have focused on relatively short-term (5 min to 3 h) ERK activation. It has recently become clear that short-term ERK effects are not directly relevant to the expression of cyclin D1, because cyclin D1 induction requires that the ERK signal persist for several hours (Weber et al., 1997).

We previously reported (Zhu and Assoian, 1995) that integrin activation by cell adhesion to ECM results in a persistent ERK activity (lasting 3 h), but we now find that this effect is not sufficiently sustained to induce cyclin D1. Similarly, we find that activation of RTKs by growth factors alone results in a transient ERK signal that is insufficient to induce cyclin D1. However, we show here that simultaneous activation of both RTKs and α5β1 results in strong ERK activity for several hours and the induction of cyclin D1. Thus, integrin activation allows for a sustained ERK signal in growth factor-treated cells, and this effect can explain the combined growth factor–anchorage requirement for the expression of cyclin D1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transfectants

NIH-3T3 cells were cotransfected with pSV2neo and pECE (a human α5 integrin expression vector). G418-resistant colonies were pooled, and stable transfectants expressing α5humanβ1mouse chimeric integrin (called hα5-3T3 cells) on the cell surface were isolated by flow cytometry after incubation with the α5β1 monoclonal antibody, P1D6 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). Surface radioiodination followed by immunoprecipitation of the cell lysates with an α5 cytoplasmic domain antibody (recognizing both the murine and human α5 subunits) showed that the transfected cells expressed approximately fourfold more α5β1 than parental 3T3 cells (our unpublished results). In serum-free medium, hα5-3T3 cells fail to attach to dishes coated with BSA, and they neither spread nor form stress fibers on dishes coated with poly-l-lysine (PLL; which promotes a non–integrin-mediated adhesion). hα5-3T3 cells poorly attach to dishes coated with the P1D6 (presumably because of the low probability of maintaining an accessible and correctly configured active site when the antibody is directly attached to plastic), but they efficiently attach and spread on P1D6 when the antibody is added to dishes precoated with secondary (anti-mouse immunoglobulin G [IgG]) antibody. hα5-3T3 cells do not attach to dishes coated with secondary antibody alone. Final conditions for use of P1D6 are outlined below.

NIH-3T3 cells were also transfected with a constitutively active MAP kinase/ERK kinase 1 (MEK-1; S218D/S222D) using the tetracycline-repressible expression system. The transfected cells were cultured in the presence of tetracycline (2 μg/ml, added daily), and stable transfectants were isolated by selection in G418 (0.5 mg/ml; Life Technologies) and hygromycin (0.4 mg/ml). Immunoblotting identified several clones in which the expression of active MEK (MEK*) was strongly regulated by tetracycline. One of those clones (tetMEK*-3T3, clone 7) is shown here, but the general results are reproducible in different clones. tetMEK*-3T3 cells were maintained at <50% confluence in DMEM and 10% calf serum with 2 μg/ml tetracycline.

Cells and Methods of Culture

To stimulate entry into the cell cycle, confluent cultures were serum starved for 1 d (NIH-3T3 cells and derivative transfectants), 2 d (mouse embryo fibroblasts [MEFs]) or 5-7 d (human skin fibroblasts) as described (Zhu et al., 1999). In some experiments, cells were trypsinized and reseeded (2 × 106 cells per 100-mm dish) in monolayer (tissue culture dishes) or suspension (agarose-coated tissue culture dishes) in DMEM with 5% FCS, 2 nM EGF (3T3 cells), or 10% FCS (MEFs and human fibroblasts) as described by Böhmer et al. (1996) and Zhu et al. (1996). For studies in defined medium, 35-mm dishes were precoated (16 h at 4°C) with fibronectin, P1D6, or PLL. Coating with fibronectin or PLL was performed as described (Zhu et al., 1999) using 15 μg fibronectin and 50 μg PLL. For studies with P1D6, 35-mm dishes were coated (16 h at 4°C) with 40 μg anti-mouse IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 1 ml PBS, followed by 120 μg P1D6 in 1 ml PBS containing 2 mg/ml heat-inactivated, fatty acid-free BSA. Quiescent cells (2 × 105 per 35-mm dish) were added in 2 ml defined medium (1:1 DMEM:Ham’s F-12, 15 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 3 mM histidine, 4 mM glutamine, 8 mM sodium bicarbonate, 10 μM ethanolamine, 10 μg/ml transferrin, 0.1 μM sodium selenite, 0.1 μM MgCl2, 2 mg/ml BSA) with or without purified growth factors (10 ng/ml PDGF, 1 μM insulin, 2 nM EGF). In some experiments, quiescent cells were preincubated with cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) for 2 h and then trypsinized and reseeded in the continued presence of cycloheximide.

Extractions and Blotting

Collected cells were lysed in TNE (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mM PMSF, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate) and analyzed by immunoblotting using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Protein concentrations were determined by Coomassie blue binding (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, protein assay). Equal amounts of protein from each cell lysate (20 μg for MEK*, ERK, and cdk4 or 100 μg for cyclin D1 and cdk4) were analyzed by immunoblotting after electrophoresis on reducing SDS gels containing 7.5% acrylamide (Zhu et al., 1999).

In Vitro ERK2 Kinase Assay

Cell lysates (50 μg) were incubated (2 h at 4°C with rocking) in 80 μl (total vol) TNE with 3 μg anti-ERK2 (SC-154; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Immune complexes were collected (1 h at 4°C with rocking) with protein A-agarose (50 μl). Collected immunoprecipitates were washed twice with cold TNE and then twice with cold kinase reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mM PMSF, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate). The washed pellet was suspended in 50 μl kinase buffer containing 5 μg myelin basic protein (Sigma), 20 μM ATP, and 10 μCi [δ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol). The kinase reaction was incubated at 30°C for 30 min with occasional mixing and stopped by addition of 2× SDS sample buffer (50 μl). After centrifugation, the supernatant was fractionated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel. Phosphorylation of myelin basic protein was detected by autoradiography of stained gels.

Immunostaining

Cells were seeded in 35-mm dishes with coverslips that had been coated with fibronectin, P1D6, or PLL (see above). Cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, incubated with 50 mM ammonium chloride, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 as described (Zhu et al., 1999). After washing with PBS, the coverslips were incubated sequentially with 100-μl droplets of rabbit anti-cyclin D1, biotin-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (300-fold dilution; PharMingen, San Diego, CA), and Texas Red-labeled streptavidin (600-fold dilution; Life Technologies) in PBS and 2% BSA. Actin was stained (30 min at room temperature) with 100-μl droplets of fluorescein-phalloidin (1–1.5 U/ml PBS; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and cell nuclei were stained (10 min at 4°C in the dark) with 100-μl droplets of DAPI (2 μg/ml PBS; Sigma). Stained coverslips were rinsed in water and mounted with Slow-Fade in glycerol-PBS (Molecular Probes). Immunofluorescent images from 1-μm sections were obtained by confocal fluorescent microscopy at 40× magnification.

RESULTS

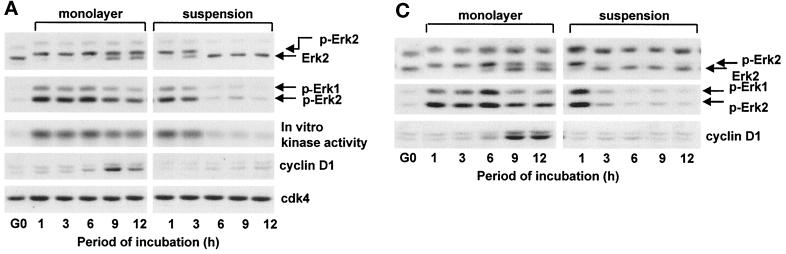

Previous studies have indicated that the induction of cyclin D1 results from the sustained activation of ERKs and that sustained ERK activity is a consequence of mitogen action (Meloche et al., 1992; Weber et al., 1997). We examined the role of mitogens and cell anchorage on the kinetics of G1 phase ERK activation by gel shift, immunoblotting with anti-phospho-ERK, and in vitro kinase assays. Each of these analyses showed that mitogens induce a transient activation of ERKs (lasting ∼1–3 h) in suspended 3T3 cells but a sustained activation (>50–75% activation up to 12 h) in adherent 3T3 cells (Figure 1A). Similar results were obtained with mouse embryo fibroblasts and early passage cultures of normal human fibroblasts (Figure 1, B and C). Cyclin D1 was detected in the adherent cells when ERK activity was maintained for several hours and not detected in suspended cells even when ERK activity was maintained for 3 h (e.g., Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Duration of the ERK signal is mediated by cell adhesion in mitogen-treated cells and correlates with cyclin D1 expression. G0-synchronzed NIH-3T3 fibroblasts (A), MEFs (B), and human fibroblasts (C) were seeded in monolayer and suspension for the indicated times. Shown are results from immunoblot analyses using antibodies specific for ERK (top panels), dually phosphorylated ERK (second panels), cyclin D1, and cdk4 (loading control). In A, lysates were also incubated with anti-ERK2, and the collected immunoprecipitate was used to assess ERK kinase activity by phosphorylation of myelin basic protein in vitro. Nonspecific kinase activity, determined using an irrelevant antibody, was comparable with that of the G0 cells, and controls demonstrated that the kinase assay was linear with regard to substrate concentration.

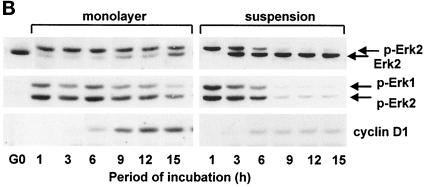

To study the cooperative regulation of ERK activation by growth factors and ECM, NIH-3T3 cells were stably transfected with a human α5 integrin cDNA (hα5-3T3 cells), which allows for recognition of the α5humanβ1mouse chimera by the α5β1 integrin monoclonal antibody P1D6. As expected, P1D6 (hereafter called anti-α5β1) detected the α5humanβ1mouse chimera in the transfectant but not the endogenous murine α5β1 integrin in parental NIH-3T3 cells (our unpublished results). hα5-3T3 and control 3T3 cells proliferated (Figure 2A) and progressed through G1 phase (assessed by expression of cyclin D1, phosphorylation of pRb, and expression of cyclin A; Figure 2B) at similar rates. The transfectants also showed a normal adhesion requirement for expression of cyclin D1 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Characterization of NIH-3T3 cells transfected with a human α5 integrin subunit. G0-synchronized hα5-3T3 and parental NIH-3T3 cells were seeded in monolayer and suspension with 5% FCS-DMEM for the times shown. In A, cell proliferation of adherent cells was assessed by staining with 0.5% crystal violet. In B, lysates from adherent cells in the first G1 phase were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific to cyclin D1, pRb (upper and lower arrows show the hyper- and hypophosphorylated forms of the protein, respectively) and cyclin A. In C, lysates from both adherent and nonadherent cells in the first G1 phase were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific to cyclin D and cdk4 (loading control).

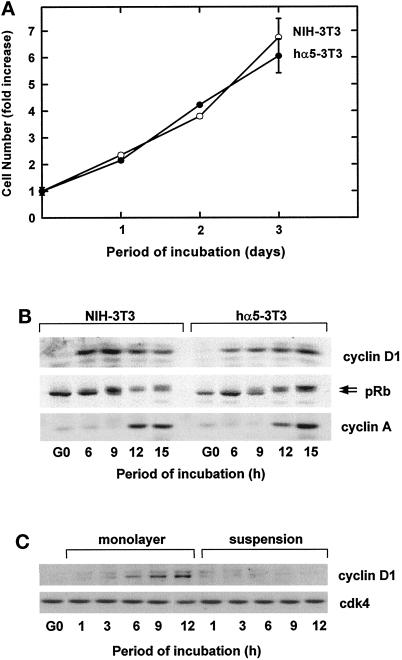

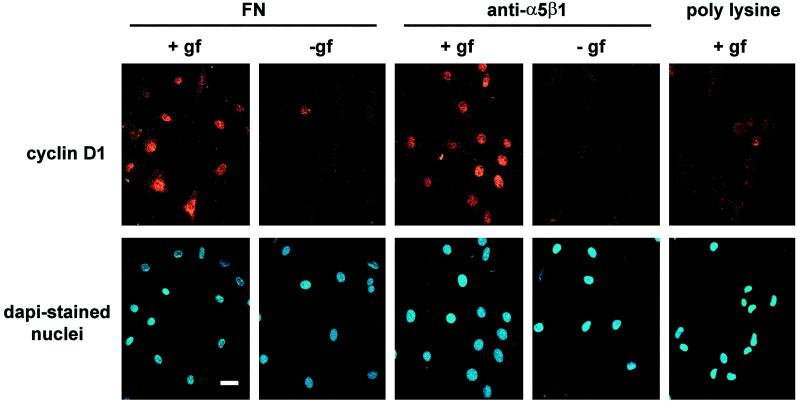

Quiescent hα5-3T3 cells attached to fibronectin, anti-α5β1, or PLL in serum-free medium were used to examine the extent and duration of ERK activation. We found that ERK activity was transient when cells were attached to fibronectin or anti-α5β1 in the absence of growth factors (Figure 3). Transient ERK activation was also observed when growth factor-treated hα5-3T3 cells were plated on PLL (Figure 3) or cultured in suspension on BSA-coated dishes (our unpublished results). In contrast, ERK activation was sustained when the cells were costimulated with growth factors and fibronectin or anti-α5β1 (Figure 3). Immunostaining (Figure 4) showed that cyclin D1 expression was barely detected when hα5-3T3 cells were plated on fibronectin or anti-α5β1 in the absence of growth factors or on PLL in the presence of growth factors. In contrast, growth factor-treated hα5-3T3 cells plated on fibronectin or anti-α5β1 uniformly expressed cyclin D1 in the nucleus. Thus, ERK activation by fibronectin alone, anti-α5β1 alone, or growth factors alone is not functionally significant for the induction of cyclin D1. Rather, the sustained ERK activity that results from the synergistic interaction of RTKs and integrins (e.g., α5β1) supports the induction of cyclin D1.

Figure 3.

Fibronectin and α5β1 integrin allow for sustained ERK activity in growth factor-treated cells. G0-synchronized hα5-3T3 cells were suspended in defined medium with (+) or without (−) purified growth factors (gf) and seeded in 35-mm dishes coated with fibronectin (FN), anti-α5β1, or PLL. At the indicated times, cells were collected, lyzed, and analyzed for ERK activation by gel shift (top panels for each substratum) and direct analysis of dually phosphorylated ERK (bottom panels for each substratum) using anti-ERK and anti-phospho-ERK, respectively.

Figure 4.

Fibronectin and α5β1 integrin allow for cyclin D1 expression in growth factor-treated cells. Cultures of hα5-3T3 cells prepared as described in the legend to Figure 3 were seeded on coverslips coated with fibronectin, anti-α5β1, and PLL. Cells were fixed at 9 h and stained for cyclin D1 and nuclei. Bar, 10 μm.

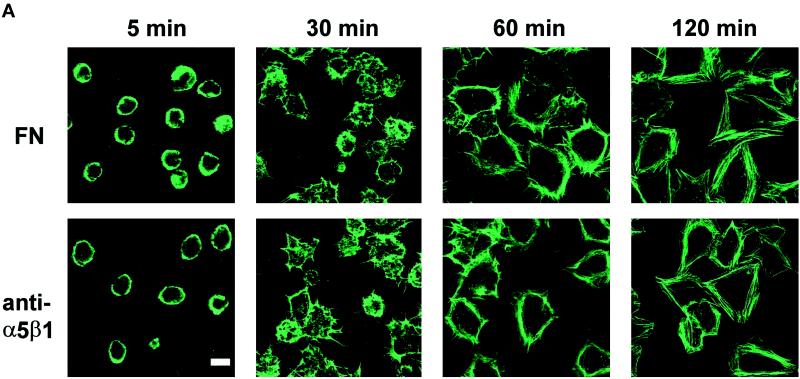

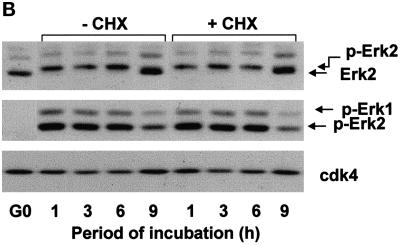

To ensure that the ERK activation seen in response to anti-α5β1 was a bona fide consequence of the antibody–integrin interaction, we treated hα5-3T3 cells with cycloheximide to block production and secretion of endogenous fibronectin and other matrix proteins. We found that the rates of attachment and spreading of cycloheximide-treated hα5-3T3 cells were indistinguishable from those seen on fibronectin (Figure 5A). Moreover, cycloheximide did not affect sustained ERK activation when growth factor-treated hα5-3T3 cells were attached to anti-α5β1-coated dishes (Figure 5B). These results strongly argue that attachment, spreading, and sustained ERK activation on anti-α5β1 does not reflect activation of other integrins by endogenous fibronectin or other secreted matrix proteins.

Figure 5.

hα5-3T3 cells attach, spread, and develop stress fibers when spread on either fibronectin or anti-α5β1. In A, G0-synchronized hα5-3T3 cells treated with cycloheximide were suspended in defined medium and seeded on coverslips coated with fibronectin or anti-α5β1. At the indicated times, cells were fixed and stained with fluorescein-phalloidin. Bar, 5 μm. In B, hα5-3T3 cells and cycloheximide (CHX)-treated hα5-3T3 cells were treated with growth factors, added to dishes coated with anti-α5β1, and collected at the indicated times. Cell lysates were fractionated on SDS gels and immunoblotted to analyze the activation of ERK by gel shift (top panel) and direct assessment of ERK phosphorylation status (bottom panel) using anti-ERK and anti-phospho-ERK, respectively. Cdk4 was used as a loading control.

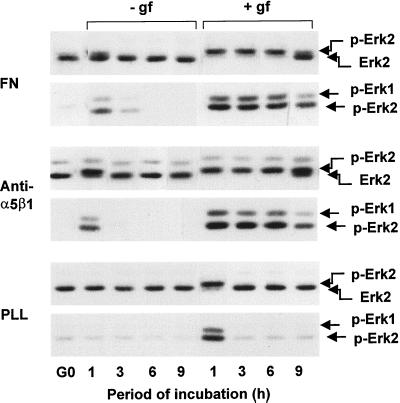

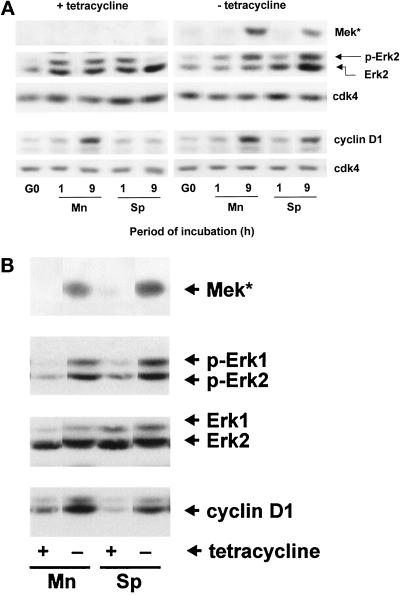

NIH-3T3 cells expressing a constitutively active MEK under control of a tetracycline-regulated promoter (tetMEK*-3T3 cells) were then prepared and used to determine whether a sustained ERK signal was sufficient to override the adhesion requirement for expression of cyclin D1 (Figure 6). In the presence of tetracycline, the suspended cells showed the expected transient activation of ERK (compare 1 and 9 h) and failed to induce cyclin D1 protein (Figure 6A). The adherent cells showed the expected sustained ERK signal (compare 1 and 9 h), and cyclin D1 protein was induced. Removal of tetracycline from suspended cells allowed for the sustained activation of ERKs despite the absence of substratum, and the degree of activation was similar to that seen in the adherent cells. Cyclin D1 protein was induced in suspended tetMEK*-3T3 cells lacking tetracycline. Thus, if ERK activation is forced to persist in the absence of substratum, cyclin D1 is induced in the absence of substratum. Forced expression of MEK* and sustained phosphorylation of ERK (for 9 h) also stimulated cyclin D1 expression when adherent cells were cultured in the absence of a mitogenic stimulus (Figure 6B, Mn) and in the absence of both a mitogenic stimulus and a substratum (Figure 6B, Sp).

Figure 6.

Sustained ERK activity underlies anchorage-dependent expression of cyclin D1. In A, tetMEK*-3T3 cells were serum starved in the presence and absence of tetracycline, trypsinized, resuspended in 5% FCS-DMEM with or without tetracycline, and reseeded in monolayer (Mn) and suspension (Sp). Cells were collected, lyzed, and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for MEK, ERK, cyclin D1, and cdk4 (loading control). ERK activation was assessed by gel shift. In B, tetMEK*-3T3 cells were plated in 0.5% FCS-DMEM for 9 h in monolayer and suspension with and without tetracycline. Cells were collected, extracted, and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for MEK, ERK (loading control), phospho-ERK, and cyclin D1.

DISCUSSION

Normal cells are both mitogen and anchorage dependent, indicating that growth factors and the ECM have distinct roles in controlling cell cycle progression. Nevertheless, there seems to be extensive overlap in the signal transduction cascades that are stimulated by growth factors and the ECM. Activation of the ERKs is a good example of this paradox, because both RTKs and integrins can individually activate the ERK pathway (Schwartz et al., 1995; Giancotti, 1997; Howe et al., 1998; Schlaepfer and Hunter, 1998). Our present data show that neither of these effects results in the sustained ERK signal required to induce cyclin D1. Rather, we show that 1) a cooperative interaction between activated RTKs and integrins results in a sustained ERK signal for several hours in G1 phase; and 2) this effect can explain the growth factor and ECM requirement for induction of cyclin D1. Others have also documented cooperative effects between growth factor receptors and integrins (Miyamoto et al., 1996; Lin et al., 1997; Renshaw et al., 1997; Moro et al., 1998; Short et al., 1998; Aplin and Juliano, 1999), but those studies used short-term incubations (5 min to 3 h) and were not directed toward the analysis of G1 phase cyclin-cdks. We show here that much longer cooperative effects on ERK activity are necessary to support the induction of cyclin D1.

We have previously reported that growth factor-dependent activation of ERKs was rapid and transient, whereas it was gradual and persistent in response to cell adhesion (Zhu and Assoian, 1995). At that time, we speculated that the rapid and sustained activation of ERK characteristic of cycling adherent cells might reflect the sequential activation of ERKs by growth factors and the ECM, respectively. However, this report shows that the sustained ERK signal necessary for induction of cyclin D1 cannot be explained merely by summing the individual effects of RTKs and α5β1 integrin (refer to Figure 3).

Although fibronectin can bind to several integrins (e.g., α3β1, α5β1, and αvβ3), the equivalent results we obtained with the antibody-coated dishes indicate that α5β1, the classical fibronectin receptor, is sufficient to sustain ERK activation in growth factor-treated cells. Because sustained ERK activity in response to anti-α5β1 is maintained in cyclocheximide-treated cells, it seems highly unlikely that the effect we observe results from surreptitious activation of other integrins, e.g., by production and secretion of endogenous collagen or vitronectin. Nevertheless, our results do not imply that α5β1 is the only integrin capable of supporting sustained ERK activity in growth factor-treated cells. In fact, Eliceiri et al. (1998) have reported that αvβ3 integrin can sustain ERK activity for 20 h in chick chorioallontoic membranes treated with basic fibroblast growth factor. Those experiments, which focused on angiogenesis and cell migration, did not address the functional significance of this effect for cell cycle progression. They also indicated that, in endothelial cells, β1 integrins would not substitute for αvβ3. Nevertheless, when viewed together, our results and those of Eliceiri et al. (1998) indicate that multiple integrins can sustain the ERK signal in growth factor-treated cells and that different integrins may mediate this effect in different cell types.

Cell adhesion leads to both integrin clustering and adhesion-dependent organization of the cytoskeleton. Several laboratories have reported that cytochalasin D (which prevents cytoskeletal organization) blocks integrin-dependent ERK activation in fibroblasts (Schwartz et al., 1995; Giancotti, 1997; Howe et al., 1998; Schlaepfer and Hunter, 1998). In fact, we find that cytochalasin D will block sustained ERK activation and cyclin D1 expression in growth factor-treated 3T3 cells (our unpublished results). Cytochalasin D also blocks cyclin D1 expression in human fibroblasts (Böhmer et al., 1996). Thus, cell spreading may be required for the cooperative effect of RTKs and integrins on sustained ERK activation in fibroblasts. Although adhesion is also important for ERK activation in endothelial cells (Short et al., 1998), cell spreading appears to play no additional role (Huang et al., 1998). Thus, the relative contributions of integrin-mediated adhesion and cytoskeletal organization to sustained ERK activation may be different in different cell types.

Several studies using activated raf (Kerkhoff and Rapp, 1997; Sewing et al., 1997; Woods et al., 1997) have indicated that sustained ERK activation allows for the induction of cyclin D1. In agreement with these results, we find that sustained ERK activity (in response to expression of constitutively active MEK) overrides both the mitogen and adhesion requirements for expression of cyclin D1. In contrast, Le Gall et al. (1998) have reported that expression of an activated raf resulted in sustained ERK activity without induction of cyclin D1 in suspended CCL39 fibroblasts. The basis for this different result remains to be determined but may be related to the different cells used. It should also be noted that the expression of cyclin D1 is not sufficient for cell cycle progression through G1 phase and entry into S phase (Ohtsubo et al., 1995).

In summary, we find that the sustained activation of ERK and expression of cyclin D1 that has typically been attributed to growth factors actually reflects concerted signaling by RTKs and integrins. This result can explain why cyclin D1 expression is jointly dependent on mitogens and cell anchorage and, at least in part, why nontransformed cells are typically both mitogen- and anchorage-dependent for growth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Erkki Ruoslahti and Michael Weber for plasmids and Jim Roberts for wild-type MEFs. This research was supported by grant CA72639 from the National Cancer Institute. K.R. is supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association. M.E.B. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Department of the Army.

REFERENCES

- Albanese C, Johnson J, Watanabe G, Eklund N, Vu D, Arnold A, Pestell RG. Transforming p21ras mutants and c-Ets-2 activate the cyclin D1 promoter through distinguishable regions. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23589–23597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplin EA, Juliano RL. Integrin and cytoskeletal regulation of growth factor signaling to the MAP kinase pathway. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:695–706. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhmer RM, Scharf E, Assoian RK. Cytoskeletal integrity is required throughout the mitogen stimulation phase of the cell cycle and mediates the anchorage-dependent expression of cyclin D1. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:101–111. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas J, Bronson RT, Jacks T. p21 is a critical CDK2 regulator essential for proliferation control in Rb-deficient cells. J Cell Sci. 1998;141:503–514. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.2.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day ML, Foster RG, Day KC, Zhao X, Humphrey P, Swanson P, Postigo AA, Zhang SH, Dean DC. Cell anchorage regulates apoptosis through the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor/E2F pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8125–8128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliceiri BP, Klemke R, Stromblad S, Cheresh DA. Integrin αvβ3 requirement for sustained mitogen-activated protein kinase activity during angiogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1255–1263. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti FG. Integrin signaling: specificity and control of cell survival and cell cycle progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:691–700. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe A, Aplin AE, Alahari SK, Juliano RL. Integrin signaling and cell growth control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:220–231. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Chen CS, Ingber DE. Control of cyclin D1, p27Kip1, and cell cycle progression in human capillary endothelial cells by cell shape and cytoskeletal tension. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3179–3193. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T, Pines J. Cyclins and cancer II: cyclin D and CDK inhibitors come of age. Cell. 1994;79:573–582. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhoff E, Rapp UR. Induction of cell proliferation in quiescent NIH-3T3 cells by oncogenic c-Raf-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2576–2586. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie JN, L’Allemain GL, Brunet A, Müller R, Pouysségur J. Cyclin D1 expression is regulated positively by the p42/p44MAPK and negatively by the p38/HOGMAPK pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20608–20616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gall M, Grall D, Chambard J-C, Pouysségur J, Van Obberghen-Schilling E. An anchorage-dependent signal distinct from P42/44 MAP kinase activation is required for cell cycle progression. Oncogene. 1998;17:1271–1277. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TH, Chen Q, Howe A, Juliano RL. Cell anchorage permits efficient signal transduction between Ras and its downstream kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8849–8852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsubo M, Theodoras AM, Schumacher J, Roberts JM, Pagano M. Human cyclin E, a nuclear protein essential for G1-to-S phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2612–2624. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloche S, Seuwen K, Pagès G, Pouysségur J. Biphasic and synergistic activation of p44mapk (ERK1) by growth factors: correlation between late phase activation and mitogenicity. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:845–854. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.5.1603090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Teramoto H, Gutkind JS, Yamada KM. Integrins can collaborate with growth factors for phosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases and MAP kinase activation: roles of integrin aggregation and occupancy of receptors. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1633–1642. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro L, Venturino M, Bozzo C, Silengo L, Altruda F, Beguinot L, Tarone G, Defilippi P. Integrins induce activation of EGF receptor: role in MAP kinase induction and adhesion-dependent cell survival. EMBO J. 1998;17:6622–6632. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radeva G, Petrocelli T, Behrend E, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Filmus J, Slingerland J, Dedhar S. Overexpression of the integrin-linked kinase promotes anchorage-independent cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13937–13944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw MW, Ren X-D, Schwartz MA. Growth factor activation of MAP kinase requires cell adhesion. EMBO J. 1997;16:5592–5599. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnitzky D. Ectopic expression of cyclin D1 but not cyclin E induces anchorage-independent cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5640–5647. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer DD, Hunter T. Integrin signaling and tyrosine phosphorylation: just the FAKs? Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(97)01172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MA, Schaller MD, Ginsberg MH. Integrins: emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:549–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewing A, Wiseman B, Lloyd AC, Land H. High-intensity Raf signal causes cell cycle arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5588–5597. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell. 1994;79:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, Roberts JR. Inhibitors of mammalian cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1149–1163. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short SM, Talbott GA, Juliano RL. Integrin-mediated signaling events in human endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1969–1980. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber JD, Raben DM, Phillips PJ, Baldassare JJ. Sustained activation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) is required for the continued expression of cyclin D1 in G1 phase. Biochem J. 1997;326:61–68. doi: 10.1042/bj3260061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg R. The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell. 1995;81:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods D, Parry D, Cherwinski H, Bosch E, Lees E, McMahon M. Raf-induced proliferation or cell cycle arrest is determined by the level of Raf activity with arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5598–5611. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Assoian RK. Integrin-dependent activation of MAP kinase: a link to shape-dependent cell proliferation. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:273–282. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.3.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Ohtsubo M, Böhmer RM, Roberts JM, Assoian RK. Adhesion-dependent cell cycle progression linked to the expression of cyclin D1, activation of cyclin E-cdk2, and phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:391–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Roovers K, Davey G, Assoian RK. Methods for analysis of adhesion-dependent cell cycle progression. In: Guan J-L, editor. Signaling through Cell Adhesion Molecules. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1999. pp. 129–140. [Google Scholar]