Abstract

Background

Hip fracture results in severe and often permanent reductions in overall health and quality of life for many older adults. As the U.S. population grows older and more diverse, there is an increasing need to assess and improve outcomes across racial/ethnic cohorts of older hip fracture patients.

Methods

We examined data from 42,479 patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation for hip fracture who were discharged in 2003 from 825 facilities across the U.S. Outcomes of interest included length of stay, discharge setting, and functional status at discharge and 3-to-6-month follow-up.

Results

Mean age was 80.2 (sd = 8.0) years. A majority of the sample was non-Hispanic white (91%), followed by non-Hispanic black (4%), Hispanic (4%), and Asian (1%). After controlling for sociodemographic factors and case severity, significant (p < .05) differences between the non-Hispanic white and minority groups were observed for predicted lengths of stay in days [95%CI] (Asian: 1.1 [0.5–1.7], non-Hispanic black: 0.8 [0.6–1.1]), odds of home discharge (Asian: 2.1 [1.6–2.8], non-Hispanic black: 2.0 [1.8–2.3], Hispanic: 1.9 [1.6–2.2]), lower discharge FIM ratings (non-Hispanic black: 3.6 [3.0–4.2], Hispanic: 1.6 [0.9–2.2] points lower), and lower follow-up FIM ratings (Hispanic: 4.4 [2.8–5.9]).

Conclusions

Race/ethnicity differences in outcomes were present in a national sample of hip fracture patients following inpatient rehabilitation. Recognizing these differences is the first step towards identifying and understanding potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between race/ethnicity and outcomes. These mechanisms may then be addressed to improve hip fracture care for all patients.

INTRODUCTION

Hip fracture is the most common fall-related reason for hospitalization in older persons and the most costly fracture to treat (1). From 1984–1994, Medicare payments for hip fracture doubled (2). It is anticipated that hip fractures that occurred ten years ago (1997) will ultimately cost the U.S. healthcare system $25 billion; this value is projected to climb to $47 billion by 2040 (3). More importantly, hip fracture dramatically and permanently affects the overall health and quality of life of many older adults (4, 5). While the age-adjusted incidence rate of hip fracture decreased 14% from 1993–2003, the total number of hip fractures increased 19% over that time (6). As the population continues to age at an unprecedented rate, the number of older persons experiencing a hip fracture is projected to rise substantially in the coming decades (7–9). Based on these population estimates and the dire consequences of this injury, emphasis needs to be placed on assessing and improving outcomes in hip fracture care (10, 11).

Within this framework of improving hip fracture outcomes it is important to consider the potential for differences based on race/ethnicity. The increase in the U.S. minority population will continue to affect the number of minorities experiencing hip fracture. For example, the proportion of total hip fractures in Hispanics and Asians living in California doubled from 1983 to 2000 (12). However, hip fracture research has primarily focused on the experiences of non-Hispanic whites as this injury is most prevalent in whites (13) and the enormous costs associated with hip fracture (1) may preclude disadvantaged individuals from getting appropriate care.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate inpatient rehabilitation outcomes following hip fracture among racial/ethnic groups. Outcomes included rehabilitation length of stay and discharge setting, which convey the relative efficiency and overall success, respectively, in establishing functional independence following hip fracture. In addition, we were interested in recorded functional status at discharge and 3–6 months post-discharge from inpatient rehabilitation.

METHODS

Data Source and Description

Data were obtained from the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation (UDSmr). The UDSmr is the largest non-governmental registry of comprehensive medical rehabilitation records in the U.S. (14, 15). Follow-up information was collected by MedTel Outcomes over the phone 80 to 180 days post-discharge and then integrated with the UDSmr inpatient records. Essential data for the current study included patient demographic information, marital status, pre-and post-hospitalization living situation, payment source, time to admission, length of stay, medical diagnosis and comorbidities, case severity, and functional status.

We limited our analysis to patients aged 60 years and older receiving inpatient rehabilitation for hip or femur fracture who were discharged in 2003. Inpatient rehabilitation refers to the intensive rehabilitation services provided to inpatients in rehabilitation hospital units or free-standing rehabilitation facilities. Qualifying etiology included hip and femur (shaft) fractures relating to UDSmr Impairment Group Codes 08.11, 08.12, and 08.2. There were 47,324 patients with the specified Impairment Group Codes with admission, discharge, and follow-up data. The final sample, after removal for missing key data (n = 894) and age restrictions (n = 3,951), contained 42,479 patient records from 825 inpatient rehabilitation facilities across the U.S.

Follow-up information is not required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) so not all facilities contributing data to the UDSmr collect it. Approximately 16% (n = 6,970) of the hip fracture cases in 2003 contained follow-up information. The mean ± sd duration from discharge to follow-up was 104.4 ± 29.6 days. Baseline demographic and health characteristics of patients with follow-up data versus those without follow-up data were similar – no significant differences were noted.

Variables

Demographic Information

Patient age in years was used as a continuous variable. Gender was coded dichotomously. Self-reported race/ethnicity was limited to Asian, Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic white categories. Other self-reported race/ethnic groups were too small to be included in the analyses. The race/ethnic groups were dummy-coded (0,1: reference = non-Hispanic white) for entry in the regression models.

Living Situation

Self-reported living arrangement (alone vs. not alone) and living setting (home vs. not home) were coded dichotomously and recorded for pre- and post-hospitalization as well as 3-to-6-month follow-up.

Payment Source

Primary payer information was coded dichotomously: Medicare vs. non-Medicare. Under the prospective payment system for inpatient rehabilitation facilities, which was implemented in 2002, facilities receive predetermined reimbursements from Medicare based on algorithms using a patient’s status (age, functioning, medical condition, and comorbidities) at admission to rehab, rather than the actual resources utilized or length of stay (i.e. fee-for services system). By aligning payment with predicted healthcare needs, this system was designed to provide equality in access to and the care provided in inpatient rehabilitation facilities for patients regardless of their health and/or functional status and projected costs to treat (16).

Duration and Length of Stay

Duration, from fracture date to admission to rehabilitation, and length of stay (LOS), from rehabilitation admission to discharge, were determined in days.

Comorbidities

A summary score was calculated for the total number of additional health conditions (range: 0–10) beyond the primary diagnosis. Specifically, this variable included any and all ICD-9 codes (maximum of 10) recorded in each patient’s medical record.

Case Severity

Case mix group (CMG) and tier level were used to determine estimated resource utilization. CMGs group patients according to expected rehabilitation needs and are the basis for the reimbursement inpatient rehabilitation facilities will receive from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for a particular patient. Tier levels represent certain comorbidities that the CMS recognize as confounding patient care within particular impairment categories. Thus, expected costs of care and corresponding reimbursements are adjusted according to the tier level (17). CMGs relevant to hip fracture were originally recorded on a 5-level scale (0701, 0702, 0703, 0704, 0705: least to most severe) and tier levels were recorded on a 4-level scale (none, tier 3, tier 2, tier 1: least to most costly). Both variables were coded dichotomously as most severe/costly vs. other: CMG 0705 vs. other and Tier 1 vs. other.

Functional Status

Functional status data were obtained using the Functional Independence Measure (FIM™ instrument) at admission, discharge, and 3 to 6 months post-discharge. The FIM instrument is a standardized measure of disability severity within the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) (17). The FIM contains 18 items covering 6 domains of functioning: self-care (activities of daily living), sphincter control, transfers, locomotion, communication, and social cognition. Each item is scored on a on a scale from 1 (complete dependence) to 7 (complete independence); i.e. higher scores represent better functioning / greater independence. The total FIM score, which is used in the current study, represents the sum total of the 18 items: range = 18 – 126. The reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the FIM are well documented (14, 18). Nurses trained in the administration and interpretation of the FIM conducted the follow-up interviews; agreement between FIM ratings obtained in person and over the phone is high (ICC = .97) (19).

Data Analysis

Demographic information, functional status, and other characteristics were stratified by race/ethnicity category in order to evaluate unadjusted differences between groups. Univariate statistics (ANOVA) were used for continuous variables and contingency tables (chi-square) were used for categorical data. A series of multiple regression models were performed to assess potential differences among the race/ethnicity groups in LOS, discharge FIM, and follow-up FIM. Logistic regression models were performed to examine differences among the race/ethnic groups in discharge setting (home vs. not home). Subsequent models controlled for sociodemographic information (gender, age, marital status, and Medicare coverage), case severity (sum of comorbidites, CMG tier level, FIM, and LOS), and pre-hospitalization living setting, respectively. Alpha was set to 0.05 with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons. SPSS v.14 software was used for all statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics (Covariates)

Patient characteristics by race/ethnicity are presented in Table 1. The total sample with inpatient data (n = 42,479) consisted of 91% non-Hispanic white, 4% non-Hispanic black, 4% Hispanic, and 1% Asian individuals. Overall, the non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Asian groups were younger and exhibited less comorbidities than the non-Hispanic white cohort.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by race/ethnicity.

| Total | Non-Hispanic white | Non-Hispanic black | Hispanic | Asian | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient Sample | N | 42,479 | 38,635 | 1,801 | 1,608 | 435 |

| FU Sample | N | 6,970 | 6,406 | 242 | 167 | 155 |

| Age (yrs)123 | Mean (sd) | 80.2 (8.0) | 80.3 (7.9) | 78.3 (9.1) | 79.0 (8.3) | 78.9 (8.0) |

| Gender (women)1 | Count (%) | 31424 (74.0) | 28662 (74.2) | 1271 (70.7) | 1163 (72.3) | 328 (75.4) |

| Married (yes)123 | Count (%) | 16202 (38.3) | 1493 (38.8) | 477 (26.8) | 577 (36.3) | 205 (47.2) |

| Pre Live Alone123 | Count (%) | 16124 (40.5) | 15043 (41.6) | 623 (36.2) | 379 (24.7) | 79 (18.9) |

| Post Live Alone123 | Count (%) | 5382 (18.6) | 5048 (19.3) | 201 (15.6) | 104 (9.2) | 29 (8.4) |

| FU Live Alone23 | Count (%) | 2100 (32.9) | 19.79 (33.7) | 72 (31.3) | 24 (16.0) | 25 (17.2) |

| Admit from Home1 | Count (%) | 300 (0.7) | 261 (0.7) | 23 (1.3) | 14 (0.9) | 2 (0.5) |

| Medicare (yes)123 | Count (%) | 39606 (93.2) | 36228 (93.8) | 1658 (92.1) | 1405 (87.4) | 315 (72.4) |

| Duration to Admit (days) | Mean (sd) | 8.5 (42.5) | 8.4 (43.9) | 9.8 (31.8) | 8.4 (12.4) | 9.0 (20.6) |

| Comorbidities (#)123 | Mean (sd) | 7.1 (2.7) | 7.1 (2.7) | 6.7 (2.8) | 6.7 (2.7) | 6.6 (2.7) |

| CMG 070512 | Count (%) | 22010 (50.8) | 19682 (50.9) | 1068 (59.3) | 1044 (64.9) | 216 (49.7) |

| CMG Tier 13 | Count (%) | 1027 (2.4) | 954 (2.5) | 37 (2.1) | 32 (2.0) | 4 (0.9) |

| LOS (days)123 | Mean (sd) | 13.5 (6.4) | 13.5 (6.4) | 14.6 (6.8) | 14.1 (5.9) | 14.3 (7.7) |

| FIM Change1 | Mean (sd) | 23.2 (13.5) | 23.3 (13.5) | 21.0 (13.1) | 22.6 (13.8) | 23.5 (11.9) |

Significance (p < .05) based on chi-square tests and ANOVAs with Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons, reference group = Non-Hispanic white:

Non-Hispanic black

Hispanic

Asian.

Relative to the non-Hispanic white group, non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics were more likely to be classified in the most severe CMG category. Conversely, they were less likely to be married, live alone before and after rehabilitation, and have Medicare coverage. Non-hispanic blacks were also less likely to be women. Individuals in the Asian group were more likely to be married and less likely to live alone before and after rehabilitation, receive the costliest tier rating, and have Medicare coverage compared to the non-Hispanic white group.

Inpatient Rehabilitation Outcomes

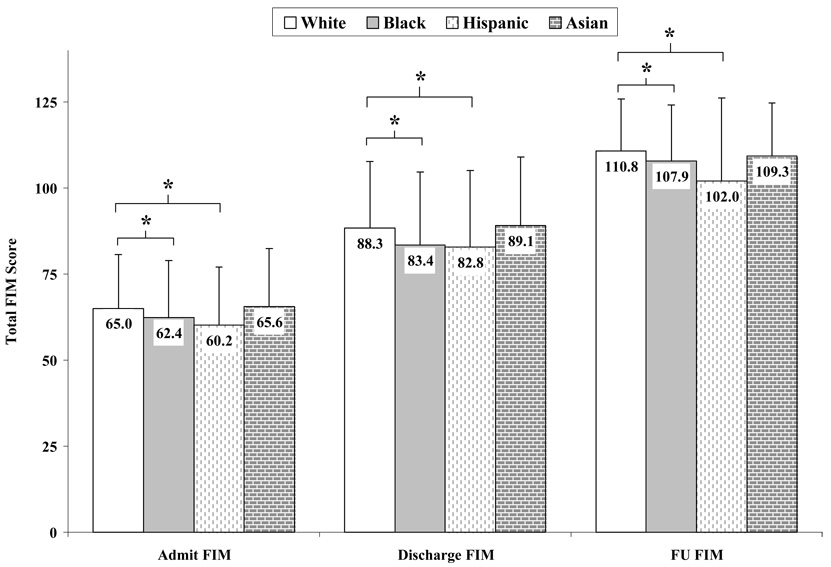

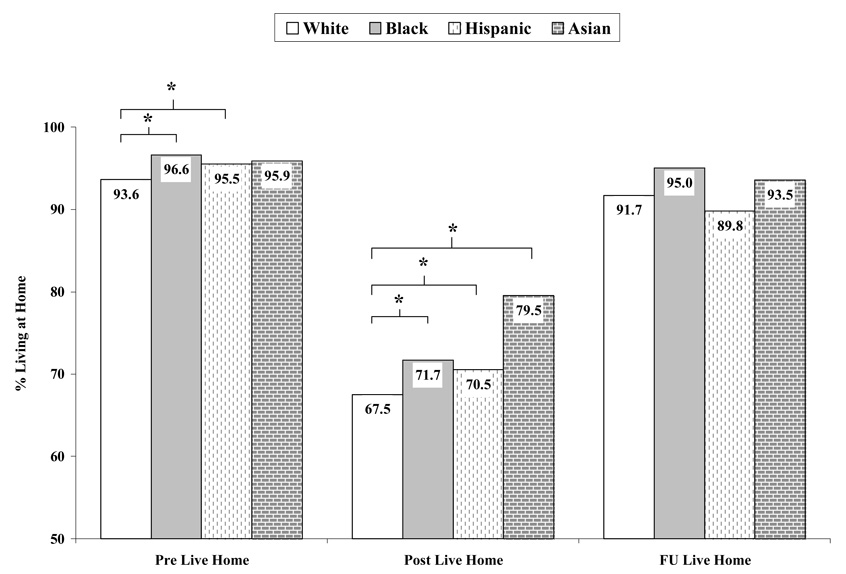

LOS by race/ethnicity is shown in Table 1. FIM ratings at admission, discharge, and 3 to 6 months following inpatient rehabilitation are presented in Figure 1. Figure 2 displays the percentage of patients living at home before, after, and 3 to 6 months following inpatient rehabilitation.

Figure 1. FIM rating by race/ethnicity.

* p < .05. Reference group = non-Hispanic white.

Figure 2. Percentage of individuals living at home by race/ethnicity.

* p < .05. Reference group = non-Hispanic white.

Table 2 shows the association between race/ethnicity and expected LOS as well as discharge and follow-up FIM. After adjusting for sociodemographic factors and case severity, non-Hispanic black and Asian race/ethnicity were associated with longer LOS relative to the non-Hispanic white cohort. Non-Hispanic black and Hispanic race/ethnicity were associated with lower discharge FIM ratings relative to the non-Hispanic white group after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, case severity, and LOS. The Hispanic group maintained an association with lower total FIM rating at follow-up compared to the non-Hispanic white group.

Table 2.

Regression coefficients for race/ethnicity on hip fracture outcomes.

| B [95% CI] | B [95% CI] | B [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of Stay | Model 1* | Model 2* | Model 3* |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.13 [0.83,1.43] | 1.21 [0.91,1.51] | 0.84 [0.56,1.12] |

| Hispanic | 0.67 [0.35,0.99] | 0.77 [0.45,1.08] | 0.12 [−0.17,0.42] |

| Asian | 0.82 [0.22,1.43] | 1.08 [0.48,1.68] | 1.09 [0.53,1.65] |

| R squared | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Discharge FIM | Model 1* | Model 2* | Model 3* |

| Non-Hispanic black | −4.91 [−5.84, −3.98] | −5.85 [−6.75, −4.96] | −3.59 [−4.19, −2.99] |

| Hispanic | −5.49 [−6.48, −4.51] | −6.04 [−6.99, −5.09] | −1.58 [−2.21, −0.94] |

| Asian | 0.81 [−1.05,2.67] | −0.21 [−2.00,1.59] | −0.82 [−2.02,0.38] |

| R squared | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.59 |

| Follow-up FIM | Model 1* | Model 2* | Model 3* |

| Non-Hispanic black | −2.76 [−4.55, −0.97] | −3.32 [−5.08, −1.55] | −0.22 [−1.66,1.21] |

| Hispanic | −7.07 [−8.96, −5.18] | −7.37 [−9.23, −5.50] | −4.35 [−5.87, −2.84] |

| Asian | −2.12 [−5.71,1.46] | −2.55 [−6.08,0.97] | −2.04 [−4.90,0.83] |

| R squared | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.37 |

F change p < .001. Reference group: non-Hispanic white.

Model 1: race/ethnicity only. Model 2: adjusted for sociodemographic factors (gender, age, married, Medicare coverage). Model 3: adjusted for sociodemographic factors and case severity (sum of comorbidites, CMG tier, admission or discharge FIM, and LOS [except for model with LOS as dependent variable]).

The odds of being discharged home versus not home relative to race/ethnicity are displayed in Table 3. All three non-reference groups demonstrated higher odds of home discharge compared with the non-Hispanic white group after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, case severity, LOS, and pre admission living setting.

Table 3.

Odds ratios for home discharge based on race/ethnicity.

| OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home Discharge | Model 1* | Model 2* | Model 3* | Model 4* |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.22 [1.10,1.36] | 1.22 [1.09,1.36] | 2.16 [1.89,2.46] | 2.02 [1.77,2.32] |

| Hispanic | 1.16 [1.04,1.30] | 1.13 [1.00,1.26] | 2.00 [1.74,2.32] | 1.90 [1.64,2.19] |

| Asian | 1.86 [1.47,2.35] | 1.64 [1.29,2.09] | 2.06 [1.55,2.73] | 2.07 [1.55,2.78] |

| R squared | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.44 |

p < .001 for block addition to model. Reference group: non-Hispanic white.

Model 1: race/ethnicity only. Model 2: adjusted for sociodemographic factors (gender, age, married, Medicare). Model 3: adjusted for sociodemographic factors and case severity (sum of comorbidites, CMG tier, discharge FIM, and LOS). Model 4: adjusted for sociodemographic factors, case severity, and pre-hospitalization living setting (home vs. not home).

DISCUSSION

There is a compelling body of literature regarding race/ethnicity-based differences in risk-factors for and prevalence of various health conditions as well as healthcare services utilization in the U.S. (20–22). Similarly, numerous works address health- and medical-related factors affecting hip fracture outcomes (7, 10, 23, 24). Relatively little information is available concerning health outcomes differences among race/ethnic groups within specific diagnostic categories, e.g. hip fracture (25, 26). We found differences for non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Asian hip fracture patients compared to non-Hispanic white patients in outcomes including LOS, functional status, and discharge setting following inpatient rehabilitation.

Longer stays in inpatient rehabilitation were observed for all three racial/ethnic groups relative to the non-Hispanic white group (Table 1). The non-Hispanic white group, on average, was older, had more comorbidities, and was more likely to have Medicare coverage than the other three groups (Table 1). These observations may help to explain why this group experienced shorter LOS; once the decision has been made to continue care in an alternative setting, it is practical to shorten the duration of high-cost inpatient rehabilitative care. Table 2, however, shows that after adjusting for sociodemographic factors and case severity expected LOS were still greater than ¾ of a day and a full day for the non-Hispanic black and Asian cohorts, respectively.

Mean discharge FIM ratings were lower in the non-Hispanic black and Hispanic groups compared with the non-Hispanic white group (Figure 1). Expected values, after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, case severity, and LOS, were 3.6 and 1.6 points lower for the non-Hispanic black and Hispanic groups, respectively (Table 2). The non-Hispanic black group experienced less improvement in FIM ratings during inpatient rehabilitation relative to the non-Hispanic white group (Table 1). Certain pre-existing medical conditions such as diabetes can reduce the functional improvements of hip fracture rehabilitation (27). Comorbidities were entered as a single summed variable in the predictive models of the current study so it cannot be determined if differences in specific disease prevalence among race/ethnic groups influenced the outcomes.

A higher proportion of patients from the non-Hispanic black group were admitted to inpatient rehabilitation from home compared to the non-Hispanic white group (Table 1). This suggests that non-Hispanic blacks were less likely to receive uninterrupted acute care prior to admission, which could partly explain the smaller improvements observed during rehabilitation. We could not assess the quality of acute care from the current database. Mean duration from time of fracture to admission was approximately 1.5 days longer in the non-Hispanic black group compared to the non-Hispanic white group; this difference was not statistically significant (Table 1). We could not determine if this trend in delayed rehabilitation admission in the non-Hispanic black cohort was primarily pre- or post-surgical. The literature is mixed regarding a relationship between surgical delay and poor outcomes (24, 28, 29), whereas no reports were found concerning the impact of duration from surgery to rehabilitation admission on long-term outcomes.

Differences between race/ethnicity groups in understanding of and trust in medical procedures may need to be considered when interpreting the current results. The demographic profile of orthopedic providers is not representative of the healthcare-seeking public in the U.S. While the proportion of combined minorities is approaching 40% of the total population, as of 1999 only 7% of orthopedic surgeons were of African-American, Latino, or Native American heritage (30). Non-Hispanic black (20, 31) and Hispanic (20) patients are more apprehensive about and less likely to undergo joint replacement surgery compared to non-Hispanic white patients with similar clinical conditions. Thus, cultural and/or personal concerns regarding medical intervention may not only reduce pre-fracture care, but also confound the complex post-fracture repair and rehabilitation processes. Additional studies are needed to determine how patient-provider interactions (32) and differences in pre-rehabilitative care influence hip fracture rehabilitation outcomes.

Regarding FIM ratings at follow-up, the non-Hispanic black and Hispanic groups were still lower, whereas the Asian cohort demonstrated comparable scores at all three assessments relative to the non-Hispanic white group (see Figure 1). Longer-term ethnicity-based outcomes differences are not unique to orthopedic patients. Hispanic patients with traumatic brain injury, for example, experience worse long-term (1 year follow-up) functional outcomes compared to non-Hispanic whites after controlling for age, LOS, injury severity, admission functional scores, and education (33).

Compared to the non-Hispanic white group, all three non-reference groups were more likely to be discharged home (see Figure 2). Although the non-Hispanic white group had shorter LOS and higher FIM ratings at discharge compared to the other groups, this group was also older, had more comorbidities, and more likely to have Medicare coverage. This could explain why the non-Hispanic white group was less likely to be discharged home; i.e. they demonstrated greater need and coverage for additional (transitional) care. Table 3, however, shows that after controlling for these factors and prior living setting all three non-reference groups were still twice as likely to be discharged home compared with those in the non-Hispanic white group.

Home discharge is generally considered a positive outcome and often used as an indicator for quality of care. The finding of relative advantage for the minority groups compared to non-Hispanic whites was unique among the rehabilitation outcomes in the current study. Previous studies assessing discharge status from inpatient rehabilitation by race/ethnicity have yielded mixed results. Ottenbacher et al. (26) reported equivalent home discharge rates among race/ethnic patient groups following hospitalization for hip fracture and lower extremity joint replacement. In separate single-facility outcomes studies in patients with stroke Chiou-Tan et al. (34) found no differences among non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic patients, whereas Bhandari and colleagues (35) reported 70% greater likelihood of home discharge for non-Hispanic black patients and no significant difference for Hispanic patients compared to non-Hispanic whites. It is clear that decisions underlying discharge destination are complex. The reasons for differences in health outcomes extend beyond objective clinical measures (36). Personal, family, and cultural values and/or preferences affect health status and care choices. It is possible that family and social support networks available to older adults are better established in certain minority groups compared to non-Hispanic whites (37, 38) and therefore increase the likelihood for home discharge. Ottenbacher et al. (26) showed that among patients discharged home from inpatient rehabilitation, non-Hispanic whites are most likely to be living alone and responsible for providing their own care. Conversely, Hispanics are most likely to have care provided by family members or other unpaid persons. Additional research is needed to elucidate these factors and to ascertain if this information could be used to expedite return home and decrease post-rehabilitation costs for non-minority patients.

Nearly 25% of independent adults require nursing home care for at least one year following hip fracture (39). At follow-up, in the current study, the percentages of individuals living at home within the non-Hispanic black (95%), Asian (94%), non-Hispanic white (92%), and Hispanic (90%) groups were not significantly different.

The reasons for health differences are multifaceted and often difficult to identify (40). The lack of acute-care information is a limitation in this study. While we accounted for functional status and number of comorbidities at admission to inpatient rehabilitation, it was not possible to adjust for differences in pre-rehabilitative care. Another potential limitation involves the use of self-report data, including race/ethnicity. It has been suggested that race in health research is limited to skin color and more of a social construct than a biologic, cultural, or behavioral one (41). Race/ethnicity based on self-reported inclusion in social categories, however, is relevant to the objectives of the current study. We also did not control for types of comorbidity that may have been disproportionately prevalent across the race/ethnic categories. Rather, we used a single value depicting the number of comorbidities each patient had as a covariate. In addition, we did not ascertain qualitative information regarding familial or cultural attitudes towards caring for ailing older adults, which may affect likelihood of home discharge and possibly, rehabilitation LOS. Lastly, with less than 20% of facilities collecting follow-up data, care must be taken when generalizing our follow-up findings to the larger population. It is important to note, however, that the follow-up sample of nearly 7,000 is of considerable size and there were no statistical differences in baseline variables between those patients contributing follow-up information and those not.

In summary, this study provides evidence of race/ethnicity-based differences within all four outcomes of interest (LOS, functional status at discharge and follow-up, and discharge setting) across a large national sample of hip fracture patients. Compared to the non-Hispanic white group, the other three groups generally experienced longer stays in inpatient rehabilitation, achieved lower functional status, and were more likely to be discharged home. These differences persisted after controlling for certain known and possible confounding variables. Thus, it is apparent that there are additional factors related to race/ethnicity, which resulted in consistent differences in rehabilitation outcomes in the current study. Further study is needed to explore potential mechanisms underlying the association between race/ethnicity and rehabilitation outcomes. Recognition and understanding of these mechanisms can then lead to improved quality of rehabilitative care for all patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (K02-AG019736 for K. Ottenbacher). J.E. Graham was supported by a fellowship from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (H133P040003) from the U.S. Department of Education. The funding source had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, or in the decision to prepare and submit the manuscript for publication. The FIM™ instrument and UDSmr are trademarks of Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation, a division of UB Foundation Activities, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roudsari BS, Ebel BE, Corso PS, et al. The acute medical care costs of fall-related injuries among the U.S. older adults. Injury. 2005;36:1316–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sloan FA, Taylor DH, Jr, Picone G. Costs and outcomes of hip fracture and stroke, 1984 to 1994. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:935–937. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.6.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braithwaite RS, Col NF, Wong JB. Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:364–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosell PA, Parker MJ. Functional outcome after hip fracture. A 1-year prospective outcome study of 275 patients. Injury. 2003;34:529–532. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00414-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolinsky FD, Fitzgerald JF, Stump TE. The effect of hip fracture on mortality, hospitalization, and functional status: a prospective study. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:398–403. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.3.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; CDC. 2006 http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/factsheets/adulthipfx.htm.

- 7.Kaehrle P, Maljanian R, Bohannon RW, et al. Factors predicting 12-month outcome of elderly patients admitted with hip fracture to an acute care hospital. Outcomes Manag Nurs Pract. 2001;5:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorngren KG, Hommel A, Norrman PO, et al. Epidemiology of femoral neck fractures. Injury. 2002;33 Suppl-7 doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orwig DL, Chan J, Magaziner J. Hip fracture and its consequences: differences between men and women. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37:611–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieberman D, Friger M, Lieberman D. Inpatient rehabilitation outcome after hip fracture surgery in elderly patients: a prospective cohort study of 946 patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melton LJ, III, Therneau TM, Larson DR. Long-term trends in hip fracture prevalence: the influence of hip fracture incidence and survival. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:68–74. doi: 10.1007/s001980050050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zingmond DS, Melton LJ., III Increasing hip fracture incidence in California Hispanics, 1983 to 2000. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:603–610. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverman SL, Madison RE. Decreased incidence of hip fracture in Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: California Hospital Discharge Data. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1482–1483. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.11.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granger CV, Kelley-Hayes M, Johnston M, Deutsch A, Braun S, Fiedler RC. Quality and Outcome Measures for Medical Rehabilitation. In: Braddom RL, editor. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1996. pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- 15.UDSMR. Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. 2007 http://udsmr.org.

- 16.Paddock SM, Escarce JJ, Hayden O, et al. Did the Medicare Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System Result in Changes in Relative Patient Severity and Relative Resource Use? Med Care. 2007;45:123–130. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250863.65686.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UB Foundation Activities. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; The Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility - Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) Training Manual. 2004 http://www.cms.hhs.gov/InpatientRehabFacPPS/downloads/irfpaimanual040104.pdf.

- 18.Ottenbacher KJ, Hsu Y, Granger CV, et al. The reliability of the functional independence measure: a quantitative review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:1226–1232. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith PM, Illig SB, Fiedler RC, et al. Intermodal agreement of follow-up telephone functional assessment using the Functional Independence Measure in patients with stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:431–435. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunlop DD, Song J, Manheim LM, et al. Racial disparities in joint replacement use among older adults. Med Care. 2003;41:288–298. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044908.25275.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoenig H, Rubenstein L, Kahn K. Rehabilitation after hip fracture--equal opportunity for all? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan JM, Lawrence R, Kington R, et al. Ethnic health disparities in arthritis and musculoskeletal diseases: report of a scientific conference. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2280–2286. doi: 10.1002/art.10480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clague JE, Craddock E, Andrew G, et al. Predictors of outcome following hip fracture. Admission time predicts length of stay and in-hospital mortality. Injury. 2002;33:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(01)00142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergeron E, Lavoie A, Moore L, et al. Is the delay to surgery for isolated hip fracture predictive of outcome in efficient systems? J Trauma Inj Inf Critical Care. 2006;60:753–757. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000214649.53190.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ottenbacher KJ, Smith PM, Illig SB, et al. Hospital readmission of persons with hip fracture following medical rehabilitation. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;36:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(02)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ottenbacher KJ, Smith PM, Illig SB, et al. Disparity in health services and outcomes for persons with hip fracture and lower extremity joint replacement. Med Care. 2003;41:232–241. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044902.01597.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieberman D, Friger M, Lieberman D. Rehabilitation outcome following hip fracture surgery in elderly diabetics: a prospective cohort study of 224 patients. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2007;29:339–345. doi: 10.1080/09638280600834542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gdalevich M, Cohen D, Yosef D, et al. Morbidity and mortality after hip fracture: the impact of operative delay. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:334–340. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0662-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grimes JP, Gregory PM, Noveck H, et al. The effects of time-to-surgery on mortality and morbidity in patients following hip fracture. Am J Med. 2002;112:702–709. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jimenez RL. Barriers to minorities in the orthopaedic profession. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 1999:44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, et al. Understanding ethnic differences in the utilization of joint replacement for osteoarthritis: the role of patient-level factors. Med Care. 2002;40:I44–I51. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Med Care. 2002;40:I140–I151. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arango-Lasprilla JC, Rosenthal M, DeLuca J, et al. Functional Outcomes From Inpatient Rehabilitation After Traumatic Brain Injury: How Do Hispanics Fare? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiou-Tan FY, Keng MJJ, Graves DE, et al. Racial/Ethnic differences in FIM[TM] scores and length of stay for underinsured patients undergoing stroke inpatient rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:415–423. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000214320.99729.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhandari VK, Kushel M, Price L, et al. Racial disparities in outcomes of inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:2081–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, et al. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113–2121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lum TY. Understanding the racial and ethnic differences in caregiving arrangements. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2005;45:3–21. doi: 10.1300/J083v45n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scharlach AE, Kellam R, Ong N, et al. Cultural attitudes and caregiver service use: lessons from focus groups with racially and ethnically diverse family caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2006;47:133–156. doi: 10.1300/J083v47n01_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magaziner J, Hawkes W, Hebel JR, et al. Recovery from hip fracture in eight areas of function. J Gerontol A -Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M498–M507. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.9.m498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarto G. Of disparities and diversity: where are we? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1188–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LaVeist TA. Beyond dummy variables and sample selection: what health services researchers ought to know about race as a variable. Health Serv Res. 1994;29:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]