Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To provide updated, evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and assessment of adults with high blood pressure.

OPTIONS AND OUTCOMES

For persons in whom a high blood pressure value is recorded, a diagnosis of hypertension is dependent on the appropriate measurement of blood pressure, the level of the blood pressure elevation, the approach used to monitor blood pressure (office, ambulatory or home/self), and the duration of follow-up. In addition, the presence of cardiovascular risk factors and target organ damage should be assessed to determine the urgency, intensity and type of treatment. For persons diagnosed as having hypertension, estimating the overall risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes requires an assessment for other vascular risk factors and hypertensive target organ damage.

EVIDENCE

MEDLINE searches were conducted from November 2004 to October 2005 to update the 2005 recommendations. Reference lists were scanned, experts were polled, and the personal files of the authors and subgroup members were used to identify other studies. Identified articles were reviewed and appraised using pre-specified levels of evidence by content and methodological experts. As per previous years, the authors only included studies that had been published in the peer-reviewed literature and did not include evidence from abstracts, conference presentations or unpublished personal communications.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The present document contains recommendations for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis of hypertension, and assessment of cardiovascular risk for adults with high blood pressure. These include the accurate measurement of blood pressure, criteria for the diagnosis of hypertension and recommendations for follow-up, assessment of overall cardiovascular risk, routine and optional laboratory testing, assessment for renovascular and endocrine causes, home and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, and the role of echocardiography for those with hypertension. Key features of the 2006 recommendations include continued emphasis on an expedited diagnosis of hypertension, an in-depth review of the role of global risk assessment in hypertension therapy, and the use of home/self blood pressure monitoring for patients with masked hypertension (subjects with hypertension who have a blood pressure that is normal in clinic but elevated on home/self measurement).

VALIDATION

All recommendations were graded according to the strength of the evidence and were voted on by the 45 members of the Canadian Hypertension Education Program Evidence-Based Recommendations Task Force. All recommendations reported herein received at least 95% consensus. These guidelines will continue to be updated annually.

Keywords: Blood pressure, Diagnosis, Guidelines, High blood pressure, Hypertension, Risk factors

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Fournir des recommandations probantes et à jour pour le diagnostic et l’évaluation des adultes atteints d’hypertension.

POSSIBILITÉS ET ISSUES

Chez les personnes dont la valeur de tension artérielle consignée est élevée, le diagnostic d’hypertension dépend d’une mesure pertinente de la tension artérielle (TA), du taux d’élévation de la TA, de la méthode utilisée pour surveiller la TA (en cabinet, en contexte ambulatoire, à domicile ou de manière autonome) et de la durée du suivi. De plus, il faut évaluer la présence de facteurs de risque cardiovasculaires et l’atteinte des organes cibles afin de déterminer l’urgence, l’intensité et le type de traitement. Chez les personnes atteintes d’hypertension diagnostiquée, pour estimer le risque global d’issues cardiovasculaires indésirables, il faut évaluer d’autres facteurs de risque vasculaires et l’atteinte des organes hypertensifs cibles.

DONNÉES PROBANTES

Des recherches dans MEDLINE ont été exécutées entre novembre 2004 et octobre 2005 afin de mettre les recommandations de 2005 à jour. Les listes de référence ont été dépouillées, on a communiqué avec des spécialistes, et les dossiers personnels des auteurs et des membres du sous-groupe ont été utilisés pour repérer d’autres études publiées. Les articles repérés ont été analysés et évalués en mettant la qualité des preuves en perspective. Comme par les années passées, seules les études parues dans des publications révisées par des pairs ont été retenues. Les données probantes tirées de résumés, de présentations à des conférences ou de communications personnelles non publiées étaient exclues.

RECOMMANDATIONS

Le présent document contient des recommandations pour mesurer la TA, diagnostiquer l’hypertension et évaluer le risque cardiovasculaire des adultes dont la TA est élevée. Ces recommandations incluent la mesure précise de la TA, les critères diagnostiques de l’hypertension et les recommandations de suivi, l’évaluation du risque cardiovasculaire global, les explorations de laboratoire systématiques et facultatives, l’évaluation des causes rénovasculaires et endocriniennes, la surveillance ambulatoire et à domicile de la TA et le rôle de l’échocardiographie chez les hypertendus. Les principales caractéristiques des recommandations de 2006 maintiennent l’importance de poser un diagnostic rapide de l’hypertension et de procéder à une analyse approfondie du rôle de l’évaluation du risque cardiovasculaire global dans le traitement de l’hypertension et de recourir à la surveillance autonome et à domicile de la TA pour les patients atteints d’hypertension masquée (les sujets hypertendus dont la TA est normale en clinique, mais élevée à domicile ou lors d’une autoévaluation).

VALIDATION

Toutes les recommandations ont été classées selon la solidité des données probantes, et les 45 membres du groupe de travail des recommandations du Programme d’éducation canadien sur l’hypertension ont exercé leur vote à cet égard. Toutes les recommandations publiées ont obtenu un consensus d’au moins 95 %. Ces lignes directrices continueront d’être mises à jour chaque année.

Hypertension affects 27% of the Canadian adult population (1) and remains the most important modifiable risk factor for vascular morbidity and mortality, not only in Canada, but worldwide (2,3). In the present document, we highlight evidence that was considered and debated by the Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) Recommendations Task Force in revising our recommendations for 2006. We have chosen to expand on new or changed recommendations in this document. For a more detailed discussion of recommendations that did not change this year, readers are referred to our previous publications (4–11). Summary documents of these recommendations, along with a downloadable slide kit, are available free of charge on the Canadian Hypertension Society’s Web site <www.hypertension.ca>.

METHODS

Our previously published methodology remains unchanged (12) and is provided in detail in the preamble to these recommendations ( pages 559 to 564). In brief, Grade A recommendations are based on studies with high levels of internal validity and statistical precision, and for which the study results are felt to be directly applicable to patients because of the similarity between study patients and clinical populations and the clinical relevance of the study outcomes. Grade B and C recommendations are derived from studies with lesser degrees of internal validity or precision, or are extrapolated from studies with high internal validity and precision but to different populations or from intermediate/surrogate outcomes rather than clinically relevant outcomes. Grade D recommendations are based on expert opinion and lower levels of internal validity or precision than Grade C recommendations.

THE 2006 CHEP RECOMMENDATIONS

I. Accurate measurement of blood pressure

Recommendations

The blood pressure (BP) of all adult patients should be assessed at all appropriate visits for the determination of cardiovascular risk and monitoring of antihypertensive treatment by health care professionals who have been specifically trained to measure BP accurately (Grade D).

The use of standardized measurement techniques (Table 1) is recommended when assessing BP for the determination of cardiovascular risk and monitoring of antihypertensive treatment (Grade D).

TABLE 1.

Recommended technique for measuring blood pressure*

|

These are instructions for blood pressure measurement when using a sphygmomanometer and stethoscope; many steps may not apply when using automated devices. Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

Background

There have been no changes to these recommendations for 2006. The CHEP Recommendations Task Force felt it important to emphasize the need to follow a standardized technique for BP measurement, particularly given reports of physician lack of awareness regarding specifics of this technique (13). It was also emphasized that changes to hypertension therapy should not be made based on a single clinic visit when other factors that may transiently influence BP are present at that visit (14).

II. Criteria for the diagnosis of hypertension and recommendations for follow-up

Recommendations

At visit 1, patients demonstrating features of a hypertensive urgency or emergency (Table 2) should be diagnosed as hypertensive and require immediate management (Grade D).

When BP is found to be elevated, a specific visit should be scheduled for the assessment of hypertension (Grade D).

At the initial visit for the assessment of hypertension, if systolic BP (SBP) is 140 mmHg or greater and/or diastolic BP (DBP) is 90 mmHg or greater, at least two more readings should be taken during the same visit according to the recommended procedure for accurate BP determination (Table 1). The first reading should be discarded and the latter two averaged using validated devices. A history and physical examination should be performed and, if clinically indicated, diagnostic tests to search for target organ damage (Table 3) and associated cardiovascular risk factors (Table 4) should be arranged within two visits. Exogenous factors that can induce or aggravate hypertension should be assessed and removed if possible (Table 5). Schedule visit 2 within one month (Grade D).

At visit 2 for the assessment of hypertension, patients with macrovascular target organ damage, diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease can be diagnosed as hypertensive if the SBP is 140 mmHg or greater and/or the DBP is 90 mmHg or greater (Grade D).

- At visit 2 for the assessment of hypertension, patients without macrovascular target organ damage, diabetes mellitus and/or chronic kidney disease can be diagnosed as hypertensive if the SBP is 180 mmHg or greater and/or the DBP is 110 mmHg or greater (Grade D). Patients without macrovascular target organ damage, diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease, but with lower BP levels, should undergo further evaluation using any of the three approaches outlined below:

- Office BPs: If using only office BPs, patients can be diagnosed as hypertensive if the SBP is 160 mmHg or greater or the DBP is 100 mmHg or greater (averaged across the first three visits), or if the SBP averages 140 mmHg or greater or the DBP averages 90 mmHg or greater after five visits (Grade D).

- Ambulatory BP monitoring: If using ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), patients can be diagnosed as hypertensive if the mean awake SBP is 135 mmHg or greater or the DBP is 85 mmHg or greater, OR if the mean 24 h SBP is 130 mmHg or greater or the DBP is 80 mmHg or greater (Grade C).

- Home/self BP measurement: If home/self BP measurement is used, patients can be diagnosed as hypertensive if the average SBP is 135 mmHg or greater or the DBP is 85 mmHg or greater (Grade C). If home/self BP measurement is less than 135/85 mmHg, it is advisable to perform 24 h ABPM to confirm that the mean 24 h ABPM is less than 130/80 mmHg and the mean awake ABPM is less than 135/85 mmHg before diagnosing white coat hypertension (Grade D).

Investigations for secondary causes of hypertension (see recommendation VI) should be initiated in patients with suggestive clinical and/or laboratory features (Grade D).

If, at the last diagnostic visit, the patient is not diagnosed as hypertensive and has no evidence of macrovascular target organ damage, the patient’s BP should be assessed at yearly intervals (Grade D).

Patients receiving lifestyle modification advice (nonpharmacological treatment) should be followed up at three- to six-month intervals. Shorter intervals (one or two monthly) are needed for patients with higher BPs (Grade D).

Patients on antihypertensive drug treatment should be seen monthly or every two months, depending on the level of BP, until readings on two consecutive visits are below their targets (Grade D). Shorter intervals between visits will be needed for symptomatic patients and those with severe hypertension, intolerance to antihypertensive drugs or target organ damage (Grade D). Once the target BP has been reached, patients should be seen at three- to six-month intervals (Grade D).

TABLE 2.

Examples of hypertensive urgencies and emergencies

| Asymptomatic diastolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg |

| Hypertensive encephalopathy |

| Acute aortic dissection |

| Acute left ventricular failure |

| Acute myocardial ischemia |

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

TABLE 3.

Examples of target organ damage

| Cerebrovascular disease |

| Transient ischemic attacks |

| Ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke |

| Vascular dementia |

| Hypertensive retinopathy |

| Left ventricular dysfunction |

| Coronary artery disease |

| Myocardial infarction |

| Angina pectoris |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Chronic kidney disease |

| Hypertensive nephropathy (glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) |

| Albuminuria |

| Peripheral artery disease |

| Intermittent claudication |

| Stroke (including transient ischemic attacks and/or vascular dementia) |

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

TABLE 4.

Examples of key cardiovascular risk factors for atherosclerosis*

| Nonmodifiable |

| Age ≥55 years |

| Male sex |

| Family history of premature cardiovascular disease (age <55 years in men and <65 years in women) |

| Modifiable |

| Sedentary lifestyle |

| Poor dietary habits |

| Abdominal obesity |

| Impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes mellitus |

| Smoking |

| Dyslipidemia |

| Stress |

| Target organ damage |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Microalbuminuria or proteinuria |

| Chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) |

Prior history of clinically overt atherosclerotic disease indicates a very high risk for a recurrent atherosclerotic event (eg, peripheral arterial disease, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack). Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

TABLE 5.

Examples of exogenous factors that can induce or aggravate hypertension

| Prescription drugs |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including coxibs |

| Corticosteroids and anabolic steroids |

| Oral contraceptive and sex hormones |

| Vasoconstricting or sympathomimetic decongestants |

| Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporin, tacrolimus) |

| Erythropoietin and analogues |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

| Midodrine |

| Other substances and conditions |

| Licorice root |

| Stimulants, including cocaine |

| Salt |

| Excessive alcohol use |

| Sleep apnea |

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

Background

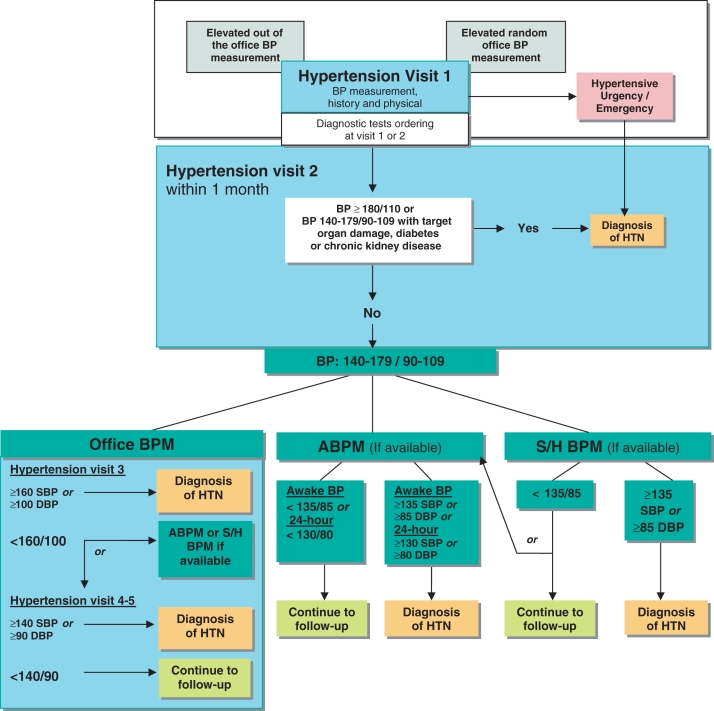

The criteria for the diagnosis of hypertension underwent significant changes in the 2005 recommendations (the rationale behind the recommendations was discussed fully in last year’s document), and there have been no changes to these recommendations for 2006 (Figure 1) (10).

Figure 1.

The expedited assessment and diagnosis of patients with hypertension (HTN): Focus on validated technologies for blood pressure (BP) assessment. All BP measurements are expressed in mmHg. ABPM Ambulatory BP monitoring; DBP Diastolic BP; S/H Self/home; SBP Systolic BP. Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

III. Assessment of overall cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients

Recommendations

Global cardiovascular risk should be assessed. Multifactorial risk assessment models can be used to predict more accurately an individual’s global cardiovascular risk (Grade A) and to use antihypertensive therapy more efficiently (Grade D). In the absence of Canadian data to determine the accuracy of risk calculations, avoid using absolute levels of risk to support treatment decisions at specific risk thresholds (Grade C).

Consider informing patients of their global risk to improve the effectiveness of risk factor modification (Grade C).

Background

Recognizing the importance of global risk assessment as a component of hypertension therapy (15,16), the 2006 recommendations include a detailed review of risk assessment tools. Risk assessment models identified in the literature were assessed across six major criteria, including features of validity, accuracy, relevance and generalizability to the Canadian population. Four models were considered in the final evaluation, including the Framingham Heart Study model (<www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/framingham/riskabs.htm>) (17–20), the Cardiovascular Life Expectancy Model (<www.chiprehab.com>) (21), the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) model (<www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/index>) (22,23) and the Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) model <www.escardio.org/knowledge/decision_tools/heartscore> (24). Risk factors common to all models included age, sex, smoking habits, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and SBP, DBP or mean BP. The presence of diabetes mellitus is a common risk factor in all models except for SCORE, where either a diabetes multiplier is available or the model can be restricted to subjects without diabetes mellitus. The outcomes predicted by each model also vary and range from fatal cardiovascular events (coronary events and stroke) in SCORE and the Cardiovascular Life Expectancy Model, to coronary artery disease, stroke or heart failure in the Framingham model and stroke, fatal coronary events or nonfatal myocardial infarction in the UKPDS model.

Given the lack of published studies examining the validity of these models in the Canadian population, the CHEP Recommendations Task Force felt that detailed guidelines for hypertension treatment based on absolute risk thresholds were not advisable at this time. However, global risk assessment in general, and the use of these models specifically, can be used as tools to assist physicians in identifying subjects with hypertension who are most likely to benefit from therapy.

IV. Routine and optional laboratory tests for the investigation of patients with hypertension

Recommendations

- Routine laboratory tests should be performed for the investigation of all patients with hypertension (all Grade D), including:

- urinalysis;

- complete blood cell count;

- blood chemistry (potassium, sodium and creatinine);

- fasting glucose;

- fasting total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides; and

- standard 12-lead electrocardiography.

For those with diabetes, assess urinary albumin excretion because BP treatment varies if albuminuria is present (Grade D).

During the maintenance phase of hypertension management, tests (including those for electrolytes, creatinine, glucose and fasting lipids) should be repeated with a frequency reflecting the clinical situation (Grade D).

Background

These recommendations have undergone minor changes for 2006. Assessment of urinary albumin excretion is no longer used as a basis for targeting lower BP, but is used to guide treatment of hypertension in association with diabetes mellitus (see Part II of these recommendations ( pages 583 to 593) for a discussion).

The CHEP Recommendations Task Force acknowledged the limited evidence to guide the choice of routine laboratory tests, and in particular, the complete blood count and standard 12-lead electrocardiography. More detailed guidelines regarding specific tests will be included in future iterations as evidence about the utility of these tests accumulates.

V. Assessment for renovascular hypertension

Recommendations

- Patients presenting with two or more of the following clinical clues, which suggest renovascular hypertension, should be investigated (Grade D):

- sudden onset or worsening of hypertension and age older than 55 years or younger than 30 years;

- the presence of an abdominal bruit;

- hypertension resistant to three or more drugs;

- a rise in creatinine associated with the use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist;

- other atherosclerotic vascular disease, particularly in patients who smoke or have dyslipidemia; and

- recurrent pulmonary edema associated with hypertensive surges.

The following tests are recommended when available to aid in the usual screening for renal vascular disease: captopril-enhanced radioisotope renal scan, Doppler sonography, magnetic resonance angiography and computed tomography angiography (Grade B).

Background

These recommendations have not changed from the 2005 recommendations (10).

VI. Endocrine hypertension

Recommendations

- Hyperaldosteronism – Screening and diagnosis:

- Screening for hyperaldosteronism should be considered for at least the following patients (Grade D):

- hypertensive patients with spontaneous hypokalemia (potassium level less than 3.5 mmol/L);

- hypertensive patients with marked diuretic-induced hypokalemia (potassium level less than 3.0 mmol/L);

- patients with hypertension refractory to treatment with three or more drugs; and

- hypertensive patients found to have an incidental adrenal adenoma.

- Screening for hyperaldosteronism should include assessment of plasma aldosterone and plasma renin activity (Table 6).

- For patients with suspected hyperaldosteronism (on the basis of the screening test, Table 6 [section iii]), a diagnosis of primary aldosteronism should be established by demonstrating inappropriate autonomous hypersecretion of aldosterone using at least one of the manoeuvres listed in Table 6 (section iv). When the diagnosis is established, the abnormality should be localized using any of the tests described in Table 6 (section v).

- Pheochromocytoma – Screening and diagnosis:

- If pheochromocytoma is strongly suspected, the patient should be referred to a specialized hypertension centre, particularly if biochemical screening tests (Table 7) have already been found to be positive (Grade D).

- The following patients should be considered for screening for pheochromocytoma (Grade D):

- patients with paroxysmal and/or severe sustained hypertension refractory to usual antihypertensive therapy;

- patients with hypertension and multiple symptoms suggestive of catecholamine excess (eg, headaches, palpitations, sweating, panic attacks and pallor);

- patients with hypertension triggered by beta-blockers, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, micturition or changes in abdominal pressure; and

- patients with incidentally discovered adrenal mass, hypertension and multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A or 2B, von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis or von Hippel-Lindau disease.

- For patients with positive biochemical screening tests, localization of pheochromocytomas should employ magnetic resonance imaging (preferable), computed tomography (if magnetic resonance imaging is unavailable), and/or iodine I-131 meta-iodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy (Grade C for each modality).

TABLE 6.

Hyperaldosteronism: Screening and diagnosis

| i. Plasma aldosterone and plasma renin activity (see [ii] for conversion factors) should be measured under standardized conditions, including the collection of morning samples taken from patients in a sitting position after resting for at least 15 min. Antihypertensive drugs may be continued, with the exception of aldosterone antagonists, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-adrenergic antagonists and clonidine. | ||

| ii. Renin, aldosterone and ratio conversion factors: | ||

| A. To estimate: | B. From: | Multiply (B) by: |

| Renin concentration (ng/mL) | Plasma renin activity (ng/mL/h) | 0.206 |

| Plasma renin activity (g/L/s) | Plasma renin activity (ng/mL/h) | 0.278 |

| Aldosterone concentration (pmol/L) | Aldosterone concentration(ng/dL) | 28 |

| iii. Definition of a positive screening test: plasma aldosterone/renin activity ratio greater than 550 pmol/L/ng/mL/h (or 140 pmol/L/ng/L when renin is measured as renin mass or concentration). | ||

| iv. Manoeuvres to demonstrate autonomous hypersecretion of aldosterone: | ||

| ||

| v. Differentiating potential causes of primary aldosteronism: | ||

| ||

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

TABLE 7.

Pheochromocytoma: Screening and diagnosis

Biochemical screening tests for pheochromocytomas:

|

Reproduced with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

Background

While most of these recommendations remain unchanged, new evidence indicates that a negative plasma fractionated metanephrine measurement can be used in a low-risk setting to rule out pheochromocytoma. This is based on a systematic review (25) that demonstrated a pooled negative likelihood ratio of 0.02 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.07) for a negative plasma fractionated metanephrine measurement in predicting pheochromocytoma in patients with sporadic pheochromo-cytoma (low-risk group). Given the low specificity, a negative result in a high-risk setting (such as a genetically predisposed patient) or a positive result in a low-risk setting (refractory hypertension) should be interpreted with caution. As documented in previous recommendations (10), for patients with known or suspected malignant pheochromocytoma, metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy may be used to assess for metastatic disease, while for patients with familial pheochromocytoma (associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease or multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A or 2B), long-term follow-up studies measuring urinary or, where available, plasma metanephrines should be performed because recurrence after laparoscopic partial or unilateral adrenalectomy is frequent.

VII. Home/self measurement of BP

Recommendations

Home/self BP readings can be used in the diagnosis of hypertension (Grade C).

- The use of home/self BP monitoring on a regular basis should be considered for patients with hypertension (Grade D), particularly those with:

- diabetes mellitus;

- chronic kidney disease;

- suspected nonadherence;

- demonstrated white coat effect; and

- BP controlled in the office but not at home (masked hypertension).

When white coat hypertension is suggested by home/self monitoring, its presence should be confirmed with ABPM before making treatment decisions (Grade D).

Patients should be advised to purchase and use only home/self BP monitoring devices that are appropriate for the individual and have met the current standards of the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, the British Hypertension Society protocol or the International Protocol for validation of automated BP measuring devices. Patients should be encouraged to use devices with data recording capabilities or automatic data transmission to increase the reliability of reported home/self BP values (Grade D).

Health care professionals should ensure that patients who measure their BP at home have adequate training, and if necessary, repeat training in measuring their BP. Patients should be observed to ensure that they measure BP correctly and should be given adequate information about interpreting these readings (Grade D).

The accuracy of all individual patients’ validated devices (including electronic devices) must be regularly checked against a device of known calibration (Grade D).

Home/self BP values for assessing white coat hypertension or sustained hypertension should be based on duplicate measures, morning and evening, for an initial seven-day period. First-day home/self BP values should not be considered (Grade D).

Background

The use of home/self BP monitoring was first expanded in the 2005 recommendations (10,26). The addition of BP assessment outside the office setting has resulted in the recognition of the phenomenon of ‘masked hypertension’, in which subjects with hypertension have normal BP with office measurements but elevated BP in the home setting (27,28). The Self measurement of blood pressure at Home in the Elderly: Assessment and Follow-up (SHEAF) study has provided evidence as to the clinical significance of masked hypertension (29). In this prospective study of 4939 treated elderly hypertensive subjects, followed for a mean of 3.2 years, the incidence of cardiovascular events in subjects with masked hypertension was similar to that of subjects with uncontrolled hypertension (ie, BP elevated both in the office and at home) at 30.6 cases (95% CI 21.2 to 39.9) and 25.6 cases (95% CI 22.4 to 28.9) per 1000 patient-years, respectively. Although the CHEP Recommendations Task Force recognized that additional evidence is required before recommendations regarding diagnosis and management of masked hypertension can be developed, the compelling evidence from the SHEAF study regarding the clinical implications of masked hypertension resulted in the new recommendation for 2006 that continued home/self BP monitoring be considered for treated hypertensive patients with BP controlled in the office but not at home (masked hypertension). The use of ABPM has also been used in the assessment of masked hypertension (30), and will be discussed in upcoming iterations of the CHEP guidelines as evidence from ongoing studies becomes available. The CHEP Recommendations Task Force felt it important to emphasize that adequate patient training is required to ensure accurate BP results from home/self BP monitoring.

VIII. Ambulatory BP measurement

Recommendations

Ambulatory BP readings can be used in the diagnosis of hypertension (Grade C).

- ABPM should be considered when an office-induced increase in BP is suspected in treated patients with:

- BP that is not below target despite receiving appropriate chronic antihypertensive therapy (Grade C);

- symptoms suggestive of hypotension (Grade C); or

- fluctuating office BP readings (Grade D).

Physicians should use only ABPM devices that have been validated independently using established protocols (Grade D).

Therapy adjustment should be considered in patients with a 24 h ambulatory SBP of 130 mmHg or greater and/or a DBP of 80 mmHg or greater and/or an awake SBP of 135 mmHg or greater and/or a DBP of 85 mmHg or greater (Grade D).

The magnitude of changes in nocturnal BP should be taken into account in any decision to prescribe or withhold drug therapy based on ambulatory BP (Grade C) because a decrease in nocturnal BP of less than 10% is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.

Background

As detailed in the 2005 recommendations, ABPM has now been included in the diagnostic algorithm for hypertension, and there are no new recommendations in 2006 (10).

IX. Role of echocardiography

Recommendations

Routine echocardiographic evaluation of all hypertensive patients is not recommended (Grade D).

An echocardiogram for the assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy is useful in selected cases to help to define the future risk of cardiovascular events (Grade C).

Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular mass as well as of systolic and diastolic left ventricular function is recommended for hypertensive patients suspected to have left ventricular dysfunction or coronary artery disease (Grade D).

Background

New evidence considered in this year’s iteration of the guidelines was the result of a Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension (LIFE) substudy (31). This substudy, which included 941 of the initial 9193 LIFE participants, included an annual assessment of left ventricular mass index at baseline for a mean of 4.8 years, and assessed the prognostic significance of left ventricular mass change and the composite end point of cardiovascular death, fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, and fatal or nonfatal stroke. In a multivariable Cox regression model, lower in-treatment left ventricular mass index was associated with a reduced rate of the composite cardiovascular end point (hazard ratio 0.78 [95% CI 0.65 to 0.94] per one standard deviation decrease in left ventricular mass index). Because this was a subgroup analysis and not a trial of therapy for left ventricular hypertrophy based on echocardiography versus usual care, the CHEP Recommendations Task Force felt that any recommendation for the use of echocardiography to track therapeutic regression of left ventricular hypertrophy was not substantiated. However, there was general consensus that echocardiography may have some potential role to track regression of left ventricular hypertrophy in selected patients; therefore, the 2005 recommendation stating that echocardiography should not be used to track therapeutic regression of left ventricular hypertrophy was deleted.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Although the present paper represents the seventh iteration of the annually updated recommendations for the management of hypertension, there are still a number of changes to be anticipated in forthcoming iterations, including a review of the recommended routine laboratory tests for the initial investigation and subsequent monitoring of patients with hypertension; assessment and monitoring for masked hypertension and white-coat hypertension; and the creation of an algorithm for the follow-up of patients with hypertension based on the use of ABPM and home/self BP monitoring.

Footnotes

Reprints: <www.hypertension.ca>

REFERENCES

- 1.Joffres MR, Hamet P, MacLean DR, L’italien GJ, Fodor G. Distribution of blood pressure and hypertension in Canada and the United States. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:1099–105. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannel WB. Blood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor: Prevention and treatment. JAMA. 1996;275:1571–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAlister FA, Levine M, Zarnke KB, et al. Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. The 2000 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part one –therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2001;17:543–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zarnke KB, Levine M, McAlister FA, et al. Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. The 2000 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part two –diagnosis and assessment of people with high blood pressure. Can J Cardiol. 2001;17:1249–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarnke KB, McAlister FA, Campbell NR, et al. Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. The 2001 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part one – Assessment for diagnosis, cardiovascular risk, causes and lifestyle modification. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:604–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAlister FA, Zarnke KB, Campbell NR, et al. Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. The 2001 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part two – Therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:625–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemmelgarn BR, Zarnke KB, Campbell NR, et al. Canadian Hypertension Education Program, Evidence-Based Recommendations Task Force. The 2004 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part I – Blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk. Can J Cardiol. 2004;20:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan NA, McAlister FA, Campbell NR, et al. Canadian Hypertension Education Program. The 2004 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part II –Therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2004;20:41–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemmelgarn BR, McAllister FA, Myers MG, et al. Canadian Hypertension Education Program. The 2005 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk. Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:645–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan NA, McAlister FA, Lewanczuk RZ, et al. Canadian Hypertension Education Program. The 2005 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part II – Therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:657–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zarnke KB, Campbell NR, McAlister FA, Levine M Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. A novel process for updating recommendations for managing hypertension: Rationale and methods. Can J Cardiol. 2000;16:1094–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mourad A, Carney S. Arm position and blood pressure: An audit. Intern Med J. 2004;34:290–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0903.2004.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthys J, De Meyere M, Mervielde I, et al. Influence of the presence of doctors-in-training on the blood pressure of patients: A randomised controlled trial in 22 teaching practices. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:769–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padwal R, Straus SE, McAlister FA. Evidence based management of hypertension. Cardiovascular risk factors and their effects on the decision to treat hypertension: Evidence based review. BMJ. 2001;322:977–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7292.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Topol EJ, Lauer MS. The rudimentary phase of personalised medicine: Coronary risk scores. Lancet. 2003;362:1776–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson KM, Wilson PW, Odell PM, Kannel WB. An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation. 1991;83:356–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J. What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1414–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Agostino RB, Sr, Grundy S, Sullivan LM, Wilson P. Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores: Results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001;286:180–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.180. CHD Risk Prediction Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Agostino RB, Russell MW, Huse DM, et al. Primary and subsequent coronary risk appraisal: New results from the Framingham study. Am Heart J. 2000;139:272–81. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.96469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grover SA, Paquet S, Levinton C, Coupal L, Zowall H. Estimating the benefits of modifying risk factors of cardiovascular disease: A comparison of primary vs secondary prevention. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:655–62. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kothari V, Stevens RJ, Adler AI, et al. UKPDS 60: Risk of stroke in type 2 diabetes estimated by the UK Prospective Diabetes Study risk engine. Stroke. 2002;33:1776–81. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020091.07144.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens RJ, Kothari V, Adler AI, Stratton IM United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. The UKPDS risk engine: A model for the risk of coronary heart disease in Type II diabetes (UKPDS 56) Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;101:671–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. SCORE project group. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: The SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawka AM, Prebtani AP, Thabane L, Gafni A, Levine M, Young WF., Jr A systematic review of the literature examining the diagnostic efficacy of measurement of fractionated plasma free metanephrines in the biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. BMC Endocr Disord. 2004;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolli P, Myers M, McKay D Canadian Hypertension Education Program. Applying the 2005 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations: 1. Diagnosis of hypertension. CMAJ. 2005;173:480–3. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickering TG, Gerin W, Schwartz AR. What is the white-coat effect and how should it be measured? Blood Press Monit. 2002;7:293–300. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mancia G. Reversed white-coat hypertension: Definition, mechanisms and prognostic implications. J Hypertens. 2002;20:579–81. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200204000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bobrie G, Chatellier G, Genes N, et al. Cardiovascular prognosis of “masked hypertension” detected by blood pressure self-measurement in elderly treated hypertensive patients. JAMA. 2004;291:1342–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.11.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stergiou GS, Salgami EV, Tzamouranis DG, Roussias LG. Masked hypertension assessed by ambulatory blood pressure versus home blood pressure monitoring: is it the same phenomenon? Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:772–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Devereux RB, Wachtell K, Gerdts E, et al. Prognostic significance of left ventricular mass change during treatment of hypertension. JAMA. 2004;292:2350–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]