Abstract

Hydra, as an early diploblastic metazoan, has a well defined extracellular matrix (ECM) called-mesoglea. It is organized in a tri-laminar pattern with one centrally located interstitial matrix that contains type I collagen and two sub-epithelial zones that resemble a basal lamina containing laminin and possibly type IV collagen. This study used monoclonal antibodies to the three hydra mesoglea components (type I, type IV collagens and laminin) and immunofluorescent staining to visualize hydra mesoglea structure and the relationship between these mesoglea components. In addition, hydra mesoglea was isolated free of cells and studied with immunofluorescence and SEM. Our results show that type IV collagen co-localizes with laminin in the basal lamina whereas type I collagen forms a grid pattern of fibers in the interstitial matrix. The isolated-mesoglea can maintain its structural stability without epithelial cell attachment. Hydra mesogleais porous with multiple trans-mesoglea pores ranging from 0.5 to 1 µm in diameter and about 6 pores per 100 µm2 in density. We think these trans-mesoglea pores provide a structural base for epithelial cells on both sides to form multiple trans-mesoglea cell-cell contacts. Based on these findings, we propose a new model of hydra mesoglea structure.

Keywords: Hydra, Extracellular matrix, Mesoglea, Basement membrane, Cell-ECM interaction

Introduction

The appearance of extracellular matrix (ECM) is associated with multicellular organisms (Har-el and Tanzer, 1993). Through evolution, the ECM changes from simple to complex in structure and molecular composition along with its function (Har-el and Tanzer, 1993). The ECM in cnidarian hydra represents one of the early forms. Studies on hydra ECM have provided insights into the overall understanding about the evolution of extracellular matrix in the animal kingdom (Sarras and Deutzmann, 2001).

Hydra has a body wall of two epithelial cell layers named ectoderm and endoderm and an ECM layer termed mesoglea sandwiched in between. Thy hydra mesoglea structure has been studied by cross section examinations using light microscopy or transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Hausman and Burnett, 1969; Wood, 1961, 1983; Haynes et al., 1968; West, 1978; Sarras et al., 1991), by tissue layer dissections using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (West, 1978; Epp et al., 1986), or by immunocytochemical staining using mesoglea-specific antibodies (Sarras et al., 1991, 1993; Zhang and Sarras, 1994; Shimizu et al., 2002). Studies on isolated mesoglea were carried out by a number of researchers and the isolated mesoglea was examined under light microscope or TEM (Shostak et al., 1965; Hausman and Burnett, 1969, 1970; Day and Lenhoff, 1981, 1983). The molecular composition of hydra mesoglea was studied through cloning of genes for hydra ECM proteins such as collagens (Deutzmann et al., 2000; Fowler et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2007) and laminin (Sarras et al., 1994; Zhang et al., 2002). Combining all the experimental data, the current understanding about hydra mesoglea is that it is a trilaminar structure with one central interstitial matrix that contains type I collagen, and two sub-epithelial basal laminae that contain laminin and possibly type IV collagen (reviewed by Sarras and Deutzmann, 2001; Sarras, 2005).

This study was designed toward three goals: 1) to confirm the localization of type IV collagen in the basal laminae; 2) to investigate the relationship between the molecular components of hydra mesoglea; and 3) to further investigate the structural details of isolated mesoglea and its relationship with epithelial cells. Our results did confirm that type IV collagen co-localizes with laminin in hydra basal laminae. In addition, we found that type I collagen in the interstitial matrix has multiple trans-mesoglea pores that are lined by laminin and type IV collagen. Our SEM study on isolated mesoglea reveals that hydra mesoglea is a unique porous structure. These trans-mesoglea pores can allow numerous trans-mesoglea cell-cell contacts to form. We also found that hydra mesoglea structure is stable even without epithelial cell attachment indicating that as early as in hydra, a well-defined stable ECM has already formed during evolution. It represents one of the early forms of metazoan ECM which has unique structural features and yet many structural similarities to the ECM that emerged later in evolution.

Materials and methods

Animal maintenance

Hydra vulgaris, L2 strain, and Hydra magnipapillada (105) were used for experiments. Animals were cultured in hydra medium (HM) made according to the M solution standard (Lenhoff, 1983) and fed with freshly hatched Artemia nauplii four times a week. All experiments were carried out 24 hours after feeding.

Mesoglea isolation

The method is adopted from Day and Lenhoff (1981, 1983). Briefly, hydra polyps were collected into an Eppendorf tube and culture medium was removed as much as possible. Two volumes of 0.1 % Nonidet P-40 prepared with H2O were added to the tube and then the tube was quickly dipped in an acetone/dry ice bath for 1 min. The tube was then taken out of freezing and the content was let thaw at room temperature. When completely thawed, the content was put in a Petri dish with dH2O and pipetted up and down with a small bore plastic pipette to remove cells. Cells are removed during repetitive pipetting and the mesoglea becomes transparent but intact. Isolated mesoglea is fixed with either 4 % paraformaldehyde for immunofluorescent staining or 2 % gluteraldehyde for SEM.

Hydra ECM extraction and Western blot

Human and bovine NC1 domains were solubilized from kidney cortex by collagenase digestion and purified as NC1 hexamers by ion-exchange on DE-52 and gel-filtration on S-300 columns (Borza et al., 2005). Hydra ECM was purified as described (Sarras et al., 1991) by repeated washes of thawed hydra stock with 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, containing 1 M sodium chloride, 1 % Triton X-100, and 10 µg/ml PMSF to remove cellular proteins. A portion of hydra ECM pellet was extracted with 10 mM EDTA in wash buffer for Western blot analysis. Another portion of the hydra ECM pellet was digested with bacterial collagenase to solubilize the noncollagenous (NC1) domain of hydra collagen IV. Hydra NC1 domains were partially purified by passage through a DE-52 ion-exchange column equilibrated with 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4. Both the EDTA-extracted and the collagenase-digested hydra ECM preparations were analyzed by SDS-PAGE in 8–20 % gradient gels under non-reducing conditions, followed by Western blotting with a rat monoclonal antibody (mAb), JK2.

Immunofluorescence staining

Hydra polyps were allowed to relax and elongate in 2 % urethane (prepared with culture medium) for 2–3 minutes. Specimens were then fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde at 4 °C overnight. Samples for JK2 staining were fixed with Lavdowsky fixative (3.7 % formaldehyde, 4 % glacial acidic acid, and 50 % ethanol) at 4 °C overnight. Then samples were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), treated with Triton X100 two times 15 minutes each. Samples for JK2 staining were pre-treated with 6 M urea in 0.1 M glycine, pH 3.5, for 15 minutes for epitope opening. After blocking with 10 % goat serum, samples were incubated with either mAb52 (mouse monoclonal antibody against hydra laminin b1 chain, HLM-b1, 1:100 dilution), mAb39 (mouse monoclonal antibody against hydra fibrillar collagen, Hcol-I, 1:500 dilution), or JK2 (rat monoclonal antibody against NC1 domain of type IV collagen, 1:500 dilution) for 60 minutes, washed and then incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody for 30 minutes, washed again before being mounted on glass slides with anti-fade reagent vectashield (Vector laboratory). For double staining with primary antibodies from different host species (mAb39+JK2 or mAb52+JK2) animals or isolated mesoglea were fixed with Lavdowsky fixative overnight at 4 °C or 60 minutes at room temperature, washed with PBS and blocked with 10 % goat serum in PBS. Primary antibodies (mAb39+JK2 or mAb52+JK2) were applied simultaneously, washed and then incubated with both fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies simultaneously for 1 hour in 1 % BSA in PBS. For double staining with primary antibodies from the same host species (mAb39+mAb52), polyps were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 60 minutes at room temperature, washed with PBS, membranes were permeabilized with PBS-T two times 15 minutes each and blocked with 10 % goat serum in PBS-T. Specimens were incubated in the primary antibody mAb52 (1:100) overnight at 4 °C, washed in PBS, and incubated with the first fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse, Zymed) for 1 hour in 1 % BSA in PBS-T. After washing, specimens were blocked in 10 % mouse serum for 1 hour, washed and incubated with a soluble immunocomplex prepared as following: a reaction tube was preabsorbed with 1 % nonfat dry milk for 1 h. Then the second primary antibody (mAb39, 1:200) was incubated in this tube with 5 µg/ml second secondary antibody (rhodamine-tagged goat anti-rabbit Fab-fragments, Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 2 h in PBS-T with 3 % BSA and 15 mM sodium azide to allow the formation of a soluble immunocomplex. To bind excess secondary antibody, the solution was blocked with 5 % normal mouse serum for an additional 2 hours (modified after Kroeber et al., 1998).

Fluorescent, confocal and electron microscopy

Samples labeled with fluorophores were examined with either epifluorescent or confocal microscopy on a Nikon 80i microscope. The SEM samples were fixed with 2 % glutaraldehyde buffered in cacodylate buffer for 1 hour at room temperature, post-fixed with 1 % osmium tetroxide for 30 minutes, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, dried in a critical point dryer with CO2, sputter coated with gold, and viewed with a Hitachi S-2700 electron microscope at 25 kV.

Results

A monoclonal antibody against the NC1 domain of type IV collagen is characterized to cross react with hydra

Although type IV collagen cDNA has been cloned from hydra (Fowler et al., 2000), its localization in hydra mesoglea was only speculated (Sarras, 2005). Through screening tests, we found that one rat mAb, JK2, reacted with hydra. This mAb was raised to the NC1 domain of α3(IV) collagen, but exhibited broad reactivity toward mammalian NC1 domains from different collagen IV networks (e.g. α1α2, α3α4α5) and species (human, bovine, rat, and mouse). For example, mAb JK2 stained several NC1 monomer (~20 kDa) and dimer (~40 kDa) subunits of purified human and bovine NC1 hexamers (Fig. 1, lanes 1–2), which were solubilized from kidney basement membranes by collagenase digestion. In the EDTA-salt extract of undigested hydra ECM, mAb JK2 stained one major band of ~180 kDa (Fig. 1, lane 3), which is the predicted size of a full-length hydra collagen IV chain. The collagenous nature of this hydra ECM antigen was demonstrated by the disappearance of the 180 kD band after digestion with collagenase (lane 4), and the appearance of new bands of ~20 kD and 40 kD, representing collagenase-resistant NC1 domains, of similar size to mammalian collagen IV NC1 monomers and dimers, respectively. After passing the crude collagenase digest of hydra ECM through a DE-52 ion-exchange column, the unbound fraction contained purified hydra NC1 domains (Fig. 1, lane 5).

Fig. 1.

Western blot analysis of rat monoclonal antibody JK2. This antibody reacts with the NC1 domains of type IV collagen from different sources including hydra.

Hydra mesoglea structure is visualized with mesoglea-specific mAbs

Using the characterized mAb JK2 in immunofluorescence staining, we found type IV collagen signal localized in hydra mesoglea as dots on parallel lines along the oral-aboral axis (Fig. 2A). When observed with higher magnification, most dots appear as rings (Fig. 2B) indicating possible existing structures surrounded by type IV collagen. We counted the number of dots or rings per ECM area in 4 individual polyps. There are averagely 6 dots or rings (5.98±1.7) per 100 (10 × 10) µm2. Laminin shows similar but more obvious dots on the lines (Fig. 2C) as seen with type IV collagen. There are also some intersecting perpendicular lines visible (Fig. 2C, arrowheads) suggesting laminin organizes as a network. At higher magnification, laminin appears as a homogeneous distribution with pores (Fig. 2D). Type I collagen organization in the mesoglea resembles a grid of fibers perpendicularly organized with regularly distributed intervals in between fibers (Fig. 2E). The intervals measure 2–3 µm. Fibers running along the oral-aboral axis of the animal are more prominent than fibers intersecting perpendicularly (Fig. 2F, arrowheads).

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescent labeling of different hydra mesoglea components. Mid-body region mesoglea is viewed through the ectoderm. The oral-aboral body axis runs vertically in all panels as indicated by the double headed arrow in panel A. (A) Type IV collagen labeling. (B) Type IV collagen signal viewed at a higher magnification. (C) Laminin labeling. Arrowheads indicate perpendicular lines (see Results). (D) Laminin distribution at a higher magnification. (E) Type I collagen shows grid-like arrangement. (F) Type I collagen at a higher magnification. Arrowheads indicate perpendicular fibers (see Results). Bar in A = 20 µm for A, C, E; bar in B = 10 µm for B and D; bar in F = 10 µm.

Isolated mesoglea maintains its structure integrity

When successfully isolated and viewed under the light microscope, mesoglea appears as a transparent thin sheet with some cells or debris left on it (data not shown). Its shape is similar to an intact polyp but contracted significantly. Isolated mesoglea is free of epithelial cell attachment and stays intact and elastic (Shostak et al., 1965; Hausman and Burnett, 1969, 1970; Day and Lenhoff, 1981, 1983). We stained isolated mesoglea with mesoglea-specific mAbs reactive to laminin and type I collagen and found the immunoreactivity was maintained the same as on the intact polyps (Fig. 3A). When isolated mesoglea was observed with higher magnifications, the immunofluorescent signals presented the same structural features as observed on intact polyps (Fig. 3B, other data not shown because they are the same as figure 2). We left isolated mesoglea in water for 20 hours before processing it for immunofluorescent staining and found no differences in staining patterns compared with those of intact polyps and those processed for immunofluorescence immediately after isolation (data not shown). This result indicates that the mesoglea structure is stable even without epithelial cell attachment.

Fig. 3.

Isolated mesoglea stained with monoclonal antibodies to hydra laminin (A) and type I collagen (B). (A) Isolated mesoglea retains the shape of a polyp with tentacles and body column. (B) An optical cross-section through isolated mesoglea reveals different surface properties on ectodermal (ect) and endodermal (end) side. Bar in A = 200 µm; bar in B = 20 µm.

The localizations of mesoglea components are visualized by double immunofluorescent staining and optical cross sections

When two mesoglea-specific antibodies for two different molecules were applied to the same sample, the molecular localizations and their spatial relationship within the mesoglea were visualized in vivo. In a collagen I + laminin double stained sample (Fig. 4A–F), type I collagen is seen as a fibrous network (Fig. 4A), the same as observed in samples stained by anti-collagen I antibody alone (Fig. 2E). The gaps (or grid holes) in between type I collagen fibers seen in figure 4A are filled by laminin signals (Fig. 4B), particularly when the two signals are visualized together (Fig. 4C). An optical cross section of type I collagen alone (Fig. 4D) reveals that there are trans-mesoglea “channels” that do not show signals (Fig. 4D, arrowheads). These “channels” are occupied by laminin signals (Fig. 4E, arrowheads and Fig. 4F). Also on optical cross sections, laminin is seen located on the two basal lamina layers whereas type I collagen is located in the central interstitial matrix (Fig. 4F). Combining images of figure 4C through 4F, one can see that there are multiple trans-mesoglea pores formed between type I collagen fibers and these pores are filled or lined by laminin. In a sample that was double stained for? type I collagen and type IV collagen (Fig. 4G–L), the fibrous structure of type I collagen was not maintained as well as in other samples (Fig. 4G and J). We think this may be due to the weaker fixative Lavdowsky compared with 4 % paraformaldehyde. However, the spatial relationship between type I and type IV collagens is still clearly visible. Type IV collagen is localized as dots and rings (Fig. 4H and I) in the basal lamina (Fig. 4K and L) and extends across the mesoglea among type I collagen fibers (Fig. 4K, arrowheads and 4L). When laminin and type IV collagen are visualized on a double stained sample (Fig. 4M–R), the co-localization of the two molecules in the basal lamina is demonstrated specifically in figure 4O and 4R.

Fig. 4.

Immunofluorescent double labeling of different mesoglea components. (A–F) Double labeling of type I collagen and laminin. (G–L) Double labeling of type I collagen and type IV collagen. (M–R) Double labeling of laminin and type IV collagen. Mesoglea is viewed either through the ectoderm (A–C, G–I, M–O) or by optical cross sections (D–F, J–L, P–R). The oral-aboral axis runs vertically in all panels as indicated by the double-headed arrow in panel A. Arrowheads in D, E, and K indicate trans-mesoglea pores (see Results). Bar in A = 10 µm for A–C, G–I, M–O; bar in D = 5 µm for D–F; bar in J = 5 µm for J–L; bar in P = 5 µm for P–R.

SEM reveals surface details of isolated mesoglea

The ectodermal surface (Fig. 5A–C) and endodermal surface (Fig. 5D–E) of isolated mesoglea were observed under SEM. On the ectodermal side, the wrinkles and furrows on the mesoglea reflect the impressions made by ectodermal epithelial cell muscle processes which are oriented along the oral-aboral axis (indicated by the double-headed arrow in Fig. 5A) of the animal (Mueller, 1950; Otto, 1977). Some thin and fibrous materials can be seen on the surface of the ectodermal side (Fig. 5A, arrowheads) that may represent the basal lamina. The investigated specimen shows prominent 0.25–0.35 µm thick fiber bundles oriented perpendicular to the body axis (Fig. 5B and C). Pore openings ranging from 0.5 to 1 (average 0.78±0.02) µm in diameter are clearly visible (Fig. 5B, arrowheads and 5C). On the endodermal side, mesoglea wrinkles and furrows appear perpendicular to the oral-aboral axis of the animal (indicated by the double arrow in Fig. 5D). The endodermal surface appears smoother than that of the ectoderm. These findings are consistent with data published by other researchers which showed the endodermal epithelial cell muscle processes run circumferentially around the body column of hydra and are thinner in size (Mueller, 1950; Otto, 1977). Multiple pore openings of 0.5–1 µm in diameter are also observed on the endodermal side (Fig. 5E). The density and the size of the pore openings observed with SEM match the result obtained from immunocytochemical labeling (Fig. 2 and Fig 4).

Fig. 5.

Scanning electron micrographs of isolated hydra mesoglea; (A–C) ectodermal side, (D–E) endodermal side. The double-headed arrows in (A) and (D) indicate the oral-aboral axis. The arrowheads in (A) point to the thin and fibrous materials that may represent basal lamina. The arrowheads in (B) indicate trans-mesoglea pore openings. (C) is the higher magnification of an area in (B). Bar in D = 10 µm for A, B, and D. Bar in E = 2 µm for C and E.

Discussion

Although type IV collagen has been cloned from hydra cDNA library (Fowler et al., 2000) and its localization has been predicted in the basal lamina (Sarras and Deutzmann, 2001; Sarras, 2005), a direct evidence showing its basal lamina localization in mesoglea is provided for the first time in this paper. We found type IV collagen co-localizes with laminin in hydra basal lamina. Both molecules are distributed as a homogeneous thin layer in the basal lamina and continue into the trans-mesoglea pores (Fig. 2 and Fig. 4). The fibrous type I collagen in the interstitial matrix permits the trans-mesoglea pores to form in between its fiber bundles. The antibody that identified type IV collagen in basal lamina was developed against the NC1 domain of type IV collagen alpha 1 chain of mammals. The cross reaction of this antibody with hydra suggests that the NC1 domain structure of type IV collagen is probably well conserved throughout evolution.

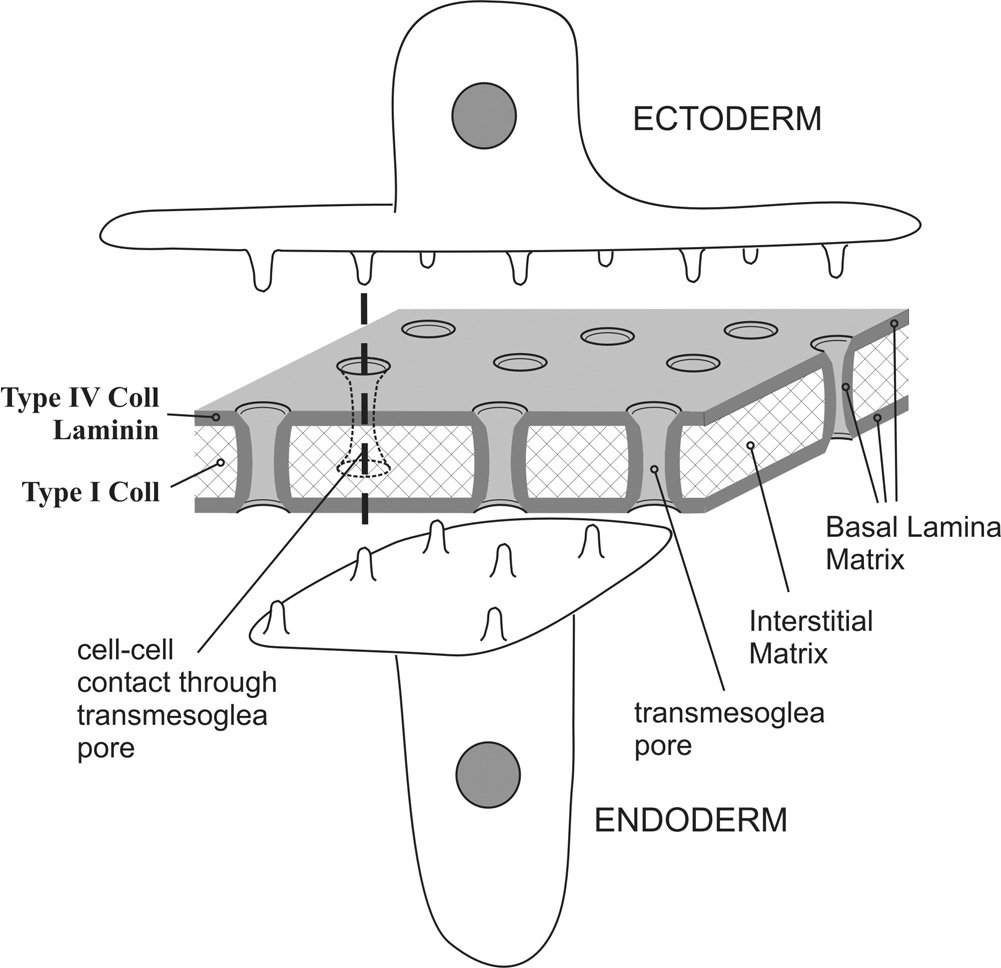

Another interesting finding of this paper is the density and size of the multiple trans-mesoglea pores revealed by immunofluorescent staining and SEM. Previously, TEM studies have provided evidence that epithelial cells on both sides send cell processes measuring 0.3–1 µm in diameter into the mesoglea and form gap junctions between them (Wood, 1961; Wood and Kuda, 1980; Wood, 1983; Haynes et al., 1968; West, 1978; Epp et al., 1986). Numerous pores on isolated mesoglea were observed on the ectoderm surface by West (1978). After removing one tissue layer and digesting away the mesoglea, Takahashi-Iwanaga et al. (1994) examined the basal sides of epithelial cells, either ectodermal or endodermal, with SEM. They found numerous cellular projections on the basal side of epithelial cells. Combining these previous data with our results, we now provide a new three-dimensional view of hydra mesoglea structure (Fig. 6): a porous trilaminar ECM with pores ranging from 0.5 to 1 µm in diameter and about six pores per 100 µm2. These trans-mesoglea pores accommodate cell processes from both epithelia. The trans-mesoglea cell processes are in contact with the basal lamina when going through the pores. The density of the trans-mesoglea pores indicates the extensive cell-cell contacts between the two epithelia.

Fig. 6.

A schematic model drawing of hydra mesoglea structure and its relationship with epithelial cells. Mesoglea is a porous structure with multiple trans-mesoglea pores that allow cell processes to protrude through and contact each other. Mesoglea is composed of two sub-epithelial basal lamina zones that contain laminin and type IV collagen. These basal lamina layers extend into the trans-mesoglea pores along with cell processes. The interstitial matrix is located in the center and contains type I collagen.

As a fresh water coelenterate, hydra polyps normally extend and retract their body columns frequently. Based on the structural features of epithelial cell muscle processes, with the ectodermal layer arranged in oral-aboral direction and the endodermal layer arranged in circumferential direction as indicated by Mueller (1950) and Otto (1977), the extension of the body column requires relaxation of the ectodermal muscle processes and contraction of the endodermal muscle processes at the same time, whereas the contraction of the body column needs the reverse actions of the muscles processes. The extensive cell-cell contacts between the two epithelia across the mesoglea may function to coordinate the coupling of these actions.

The discovery of the porous nature of hydra mesoglea raises several questions. How are these pores formed and maintained? Are they static structures that once formed stay continuously or are they dynamic structures that form only when trans-mesoglea cell processes penetrate the mesoglea? How do epithelial cells migrate with so many trans-mesoglea processes deeply rooted in the mesoglea? Our data can only provide limited answers to these questions. The TEM studies on cross sections of intact hydra polyps have always shown epithelial cell processes protruding into the mesoglea (Hausman and Burnett, 1969; Wood, 1961, 1983; Haynes et al., 1968; West, 1978; Sarras et al., 1991). No TEM photographs have shown trans-mesoglea passages or channels that are the same scale but without cell processes in them. Our immunofluorescent study has shown that every trans-mesoglea pore runs completely through the entire width of mesoglea. Combining the TEM data and our data, it is reasonable to assume that under in vivo conditions every trans-mesoglea pore is associated with a trans-mesoglea cell process: no cell process, no trans-mesoglea pore. To extend this assumption, we reason that the trans-mesoglea pores are created and maintained by the trans-mesoglea cell processes. The isolated mesoglea is free of epithelial cells and yet the trans-mesoglea pores are still visible (Fig. 5). This could be due to the mesoglea isolation process which freezes the polyps very quickly and then removes the epithelial cells in thawing. By this procedure, the mesoglea is “frozen” at a specific state which allows visualization of its “live” structure. This data also indicates that the pores are relatively stable structures that once formed do not collapse immediately when the trans-mesoglea cell processes are pulled out. Based on all of the available data, we think the formation of the pores is a dynamic process in vivo along with cell process formation and matrix remodeling.

The isolated hydra mesoglea maintains its structural features both immunocytochemically and ultrastructurally even 20 hours after isolation. Besides the advantages of the isolation procedure which “freezes” the mesoglea structure at a “live” stage, this data also indicates that mesoglea has a stabilized and well defined structure that, once formed, can stay independent of epithelial cell attachment. Considering the position of hydra on the evolutionary tree, our data places a structurally well defined and stabilized ECM at an early stage in evolution.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ms. Barbara Fegley for her help in the SEM sample processing. This work was supported by a fellowship to XZ from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and by an NIH program project grant (P01-DK065123, program leader Dale Abrahamson) to MPS and XZ.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Borza DB, Bondar O, Colon S, Todd P, Sado Y, Neilson EG, Hudson BG. Goodpasture autoantibodies unmask cryptic epitopes by selectively dissociating autoantigen complexes lacking structural reinforcement. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27147–27154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RM, Lenhoff HM. Hydra mesoglea: a model for investigating epithelial cell-basement membrane interactions. Science. 1981;211:291–294. doi: 10.1126/science.7444468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RM, Lenhoff HM. Isolating mesolamellae. In: Lenhoff HM, editor. Hydra: Research Methods. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 327–329. [Google Scholar]

- Deutzmann R, Fowler S, Zhang X, Boone K, Dexter S, Boot-Handford RP, Rachel R, Sarras MP. Molecular, biochemical and functional analysis of a novel and developmentally important fibrillar collagen (Hcol-I) in hydra. Development. 2000;127:4669–4680. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.21.4669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp L, Smid I, Tardent P. Synthesis of the mesoglea by ectoderm and endoderm in reassembled hydra. J. Morphol. 1986;189:271–279. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051890306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler SJ, Jose S, Zhang X, Deutzmann R, Sarras MP, Boot-Handford RP. Characterization of hydra type IV collagen. Type IV collagen is essential for head regeneration and its expression is up-regulated upon exposure to glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:39589–39599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Har-el R, Tanzer ML. Extracellular matrix 3: evolution of the extracellular matrix in invertebrates. FASEB J. 1993;7:1115–1123. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.12.8375610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman RE, Burnett AL. The mesoglea of Hydra. I. Physical and histochemical properties. J. Exp. Zool. 1969;171:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman RE, Burnett AL. The mesoglea of Hydra. III. Fiber system changes in morphogenesis. J. Exp. Zool. 1970;173:175–186. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401730206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes JF, Burnett AL, Davis LE. Histological and ultrastructural study of the muscular and nervous system in Hydra. I. The muscular system and the mesoglea. J. Exp. Zool. 1968;167:283–293. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401670304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber S, Schomerus C, Korf H-W. A specific and sensitive double-immunofluorescence method for the demonstration of S-antigen and serotonin in trout and rat pinealocytes by means of primary antibodies from the same donor species. Histochem. Cell Biol. 1998;109:309–317. doi: 10.1007/s004180050231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhoff HM. Water, culture solutions, and buffers. In: Lenhoff HM, editor. Hydra: Research Methods. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller JF. Some observations on the structure of hydra, with particular reference to the muscular system. Trans. Amer. Microsc. Soc. 1950;69:133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Otto JJ. Orientation and behavior of epithelial cell muscle processes during Hydra budding. J. Exp. Zool. 1977;202:307–322. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402020303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarras MP. Epithelial-extracellular matrix (cell-ECM) interactions in hydra. In: Savagner P, editor. Rise and Fall of Epithelial Phenotypes: Concepts of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. New York: Landes Bioscience Press/Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2005. pp. 56–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sarras MP, Jr, Deutzmann R. Hydra and Niccolo Paganini (1782–1840) – two peas in a pod? The molecular basis of extracellular matrix structure in the invertebrate, Hydra. BioEssays. 2001;23:716–724. doi: 10.1002/bies.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarras MP, Jr, Madden ME, Zhang X, Gunwar S, Huff JK, Hudson BG. Extracellular matrix (mesoglea) of Hydra vulgaris. I. Isolation and characterization. Dev. Biol. 1991;148:481–494. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarras MP, Jr, Zhang X, Huff JK, St. John PL, Abrahamson DR. Extracellular matrix (mesoglea) of Hydra vulgaris. III. Formation and function during morphogenesis of Hydra cell aggregates. Dev. Biol. 1993;157:383–398. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarras MP, Jr, Yan L, Grens A, Zhang X, Agbas A, Huff JK, St. John PL, Abrahamson DR. Cloning and biological function of laminin in Hydra vulgaris. Dev. Biol. 1994;164:312–324. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu H, Zhang X, Zhang J, Leontovich A, Fei K, Yan L, Sarras MP., Jr Epithelial morphogenesis in hydra requires de novo expression of extracellular matrix components and matrix metalloproteinases. Development. 2002;129:1521–1532. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shostak S, Patel NG, Burnett AL. The role of mesoglea in mass cell movement in Hydra. Dev. Biol. 1965;12:434–450. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(65)90008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi-Iwanaga H, Koizumi O, Fujita T. Scanning electron microscopy of the muscle system of Hydra magnipapillata. Cell Tissue Res. 1994;277:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- West DL. The epitheliomuscular cell of hydra: its fine structure, three-dimensional architecture and relation to morphogenesis. Tissue Cell. 1978;10:629–649. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(78)90051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RL. The fine structure of intercellular and mesogleal attachments of epithelial cells in hydra. In: Lenhoff HM, Loomis WF, editors. The Biology of Hydra and Some Other Coelenterates. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press; 1961. pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wood RL. Preparing hydra for transmission electron microscopy. In: Lenhoff HM, editor. Hydra: Research Methods. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wood RL, Kuda AM. Formation of junctions in regenerating hydra: gap junctions. J. Ultrastructure Res. 1980;73:350–360. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(80)90094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Sarras MP., Jr Cell-extracellular matrix interactions under in vivo conditions during interstitial cell migration in Hydra vulgaris. Development. 1994;120:425–432. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Fei K, Agbas A, Yan L, Zhang J, O’Reilly B, Deutzmann R, Sarras MP., Jr Structure and function of an early divergent form of laminin in hydra: a structurally conserved ECM component that is essential for epithelial morphogenesis. Dev. Genes Evol. 2002;212:159–172. doi: 10.1007/s00427-002-0225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Boot-Handford RP, Huxley-Jones J, Forse LN, Mould AP, Robertson DL, Li L, Athiyal M, Sarras MP., Jr The collagens of hydra provide insight into the evolution of metazoan extracellular matrices. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:6792–6802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]