Abstract

Angiogenesis is a complex process, requiring a finely tuned balance between numerous stimulatory and inhibitory signals. ALK1 is an endothelial-specific type 1 receptor of the TGFβ receptor family. Heterozygotes with mutations in the ALK1 gene suffer from Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia type 2 (HHT2). Recently, we reported that BMP9 and BMP10 are specific ligands for ALK1 that potently inhibit microvascular endothelial cell migration and growth. These data lead us to suggest that these factors might play a role in the control of vascular quiescence. To test this hypothesis, we checked their presence in human serum. We found that human serum induced Smad1/5 phosphorylation. In order to identify the active factor, we tested neutralizing antibodies against BMP members and found that only the anti-BMP9 inhibited serum-induced Smad1/5 phosphorylation. The concentration of circulating BMP9 was found to vary between 2 and 12 ng/ml in sera and plasma from healthy humans, a value well above its EC50 (50 pg/ml). These data indicated that BMP9 is circulating at a biologically active concentration. We then tested the effects of BMP9 in two in vivo angiogenic assays. We found that BMP9 strongly inhibited sprouting angiogenesis in the mouse sponge angiogenesis assays and that BMP9 could inhibit blood circulation in the chicken chorioallantoic membrane assay. Taken together, our results demonstrate that BMP9, circulating under a biologically active form, is a potent anti-angiogenic factor that is likely to play a physiological role in the control of adult blood vessel quiescence.

Keywords: 3T3 Cells; Activin Receptors, Type II; genetics; physiology; Adult; Angiogenic Proteins; Animals; Bone Morphogenetic Proteins; blood; physiology; Case-Control Studies; Chick Embryo; Female; Humans; Male; Mice; Middle Aged; Neovascularization, Physiologic; Smad Proteins; metabolism; Telangiectasia, Hereditary Hemorrhagic; blood; genetics; Transfection

Keywords: BMP9, ALK1, HHT, angiogenesis

Introduction

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), which belong to the TGFβ superfamily, were originally identified as inducers of ectopic bone growth and cartilage formation. Since then, there has been substantial progress in our knowledge of the multiple functions of these growth factors1. BMPs regulate cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis of various cell types, and they are critically important in the morphogenesis and differentiation of tissues and organs. BMP9, also known as GDF2, is expressed in the adult liver by non-parenchymal cells (i.e. endothelial, stellate, and Kupffer cells)2 and in the septum and spinal cord of mouse embryos3. BMP9 has been described as a hematopoietic, hepatogenic, osteogenic and chondrogenic factor. It has also been identified as a regulator of glucose metabolism, capable of reducing glycaemia in diabetic mice and as a differentiation factor for cholinergic neurons in the central nervous system3. More recently, it was shown to induce the expression of hepcidin, an hormone that plays a key role in iron homeostasis4.

ALK1 (activin receptor like-kinase 1) is an endothelial-specific type I receptor of the TGFβ receptor family that is implicated in the pathogenesis of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia type 2 (HHT2) also known as the Rendu-Osler disease type 2 (RO2)5. The disease is an autosomal dominant vascular disorder characterized by recurrent nosebleeds, cutaneous telangiectases, and arteriovenous malformations in the lungs, brain, liver and gastrointestinal tract6. The majority of cases are caused by mutations in either endoglin (ENG) or ALK1 (ACVRL1) genes, thus defining HHT1 and HHT2, respectively. Mutations in SMAD4 are seen in patients with the combined syndrome of Juvenile Polyposis (JP) and HHT (JP-HHT)7. Despite the identification of these mutations as the causative factor in HHT, the mechanism by which these mutations cause the HHT phenotype remain unclear.

ALK1 is one of seven known type I receptors for TGF-β family members8. Signaling through the TGFβ receptor family occurs via ligand binding to heteromeric complexes of type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors9. The type I receptor determines signal specificity in the receptor complexes. Activation of ALK1 induces phosphorylation of receptor-regulated Smad1, 5 and 810, which assemble into heteromeric complexes with the common partner Smad4. These heteromeric complexes translocate to the nucleus, where they regulate the transcription of target genes.

ALK1 has long been known as an orphan type I receptor of the TGFβ family predominantly present on endothelial cells. Subsequently, TGFβ1 and 3, primarily known as ligands for ALK5, were also shown to bind ALK1, albeit only in the presence of ALK511. In 2005, a publication describing the crystal structure of BMP9 reported that BMP9 specifically binds biosensor-immobilized recombinant ALK1 and BMPRII extracellular domains12. More recently, we demonstrated that BMP9 and BMP10 are potent ligands for ALK1 on human dermal microvascular endothelial cells13 and this was since confirmed by another group14. BMP9 is very potent (EC50 = 2 pM) and, in contrast to TGFβ1 or 311, induces a very stable Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation over time.13 Interestingly, another ALK1 ligand, distinct from TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 and that could signal in the absence of ALK5 or TGFβRII, had been previously described in human serum, but not identified15. The aim of the present work was to identify this circulating ALK1 ligand. Here we demonstrate that BMP9 is indeed the ALK1 ligand present in human serum. BMP9 circulates in a biologically active form at a concentration of 2–12 ng/ml. Furthermore, we report that BMP9 is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis and a regulator of vascular tone.

Materials and Methods

An expanded materials and methods is available in the online data supplement at http://www.circresaha.org.

DNA transfection and dual luciferase activity assay

NIH-3T3 cells were transfected as previously described13. Firefly and renilla luciferase activities were measured sequentially with the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay (Promega).Results are expressed as ratios of firefly luciferase activity over renilla luciferase activity.(See the online data supplement).

Purification of the ALK1 ligand from human serum

250 ml of human serum (pool of human sera from about 250 different individuals, Cambrex) were diluted with 250 ml PBS (Phosphate Buffer Saline 0.15 M, pH 7.4) and purified through five different steps as detailed in the online data supplement.

Western blot analysis

Western blots were performed as previously described13. (See the online data supplement).

Blood donors

Between December 2006 and July 2007, blood samples (7 ml) were taken from 20 patients (8 women, 12 men, mean age of 44 ± 12 years) with clinical features of HHT (13 with ACVRL1 mutations, 2 with ENG mutations and 5 with unidentified mutations) and 20 healthy volunteers (8 women, 12 men, mean age of 44 ± 10 years) from which serum or plasma (K3E tubes, Becton Dickinson, Pont de Claix, France) were obtained. Serum and plasma aliquots were frozen at −20°C. Informed consent was obtained from all blood donors. The investigation conformed to the principles outlined in the Helsinki declaration. The donors were randomly assigned a number. Patients were considered to be affected by HHT if they had at least three out of the four Curaçao consensus criteria16: epistaxis, telangiectases,visceral lesions and family history of HHT disease.

Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Assay

The effect of BMP9 on vascularization in the chick chorionallantoic membrane was studied as described in the online data supplement.

Mouse subcutaneous sponge angiogenesis assay

The effect of BMP9 on neovascularization in the mouse sponge assay in response to FGF-2 was studied as described in the online data supplement.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using a Mann Whitney test (**: p < 0.01; *: p < 0.05).

Results

Presence of an ALK1 ligand in human serum that differs from TGFβ

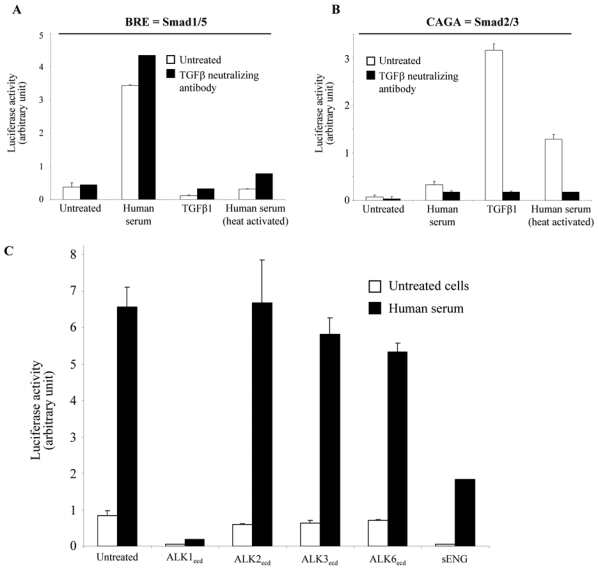

The luciferase reporter construct (BRE, BMP Responsive Element) which contains repeated sequences from the Id1 promoter has been developed to specifically measure activation of the Smad1/5/8 pathway17. This plasmid, together with an ALK1-expression plasmid, were transfected in NIH-3T3 cells in order to check for the presence of an ALK1 ligand in human serum. Treatment of these cells with 2% human serum strongly stimulated luciferase activity (9 fold, Fig. 1 A). In order to determine whether this activity was due to TGFβ, a pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody was added to serum. As shown in Figure 1A, addition of the neutralizing antibody did not affect serum activity. Furthermore, the addition of recombinant TGFβ 1 (0.5 ng/ml) did not activate this reporter gene and actually decreased basal luciferase expression (Fig. 1A). Heat-treatment, in order to activate the latent TGFβ present in serum, did not result in BRE activation (Fig. 1A). We next examined whether human serum could activate the CAGA promoter, which is known to be specifically activated by the Smad2/3 pathway in response to TGFβ. We found that human serum caused a small induction of the CAGA promoter (4 fold), while heat-treated serum and recombinant TGFβ1 strongly activated it (17 and 42 fold, respectively, Fig. IB). These activations were inhibited by the addition of the pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody (Fig. 1B). The BRE promoter is specific for the Smad1/5/8 pathway and therefore can be activated by all the type I receptors known to phosphorylate these Smads, namely ALK1, ALK2, ALK3 and ALK6. Therefore, in order to confirm that the activation of BRE by human serum was actually due to ALK1 activation, we tested the ability of the recombinant extracellular domains of these receptors to interfere with the human serum response. As shown in Fig. 1C, addition of ALK1ecd very strongly inhibited the human serum response. ALK3ecd and ALK6ecd only slightly inhibited this response while ALK2ecd had no effect. Interestingly, we could also demonstrate that soluble endoglin inhibited this biological response (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that an ALK1-stimulating ligand, distinct from TGFβ1, 2 or 3 is present in human serum.

Figure 1. Presence of an ALK1 ligand in human serum that differs from TGFβ.

NIH-3T3 cells were transiently transfected with pALK1 and pRL-TK-luc and either pGL3(BRE)-luc (A) or pGL3(CAGA)12-luc (B). Transfected cells were then treated either with human serum (2%), TGFβ1 (0.5 ng/ml) or heat-activated human serum (2%) with or without pan-specific neutralizing TGFβ antibody (1 μg/ml). C: NIH-3T3 cells were transiently transfected with pGL3(BRE)-luc, pALK1 and pRL-TK-luc. Transfected cells were then treated with human serum (2%) in presence or absence of either ALK1ecd, ALK2ecd, ALK3ecd, ALK6ecd or soluble endoglin (200 ng/ml). The luciferase activities were then measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown in A, B and C are expressed as mean values ± SD from a representative experiment out of three.

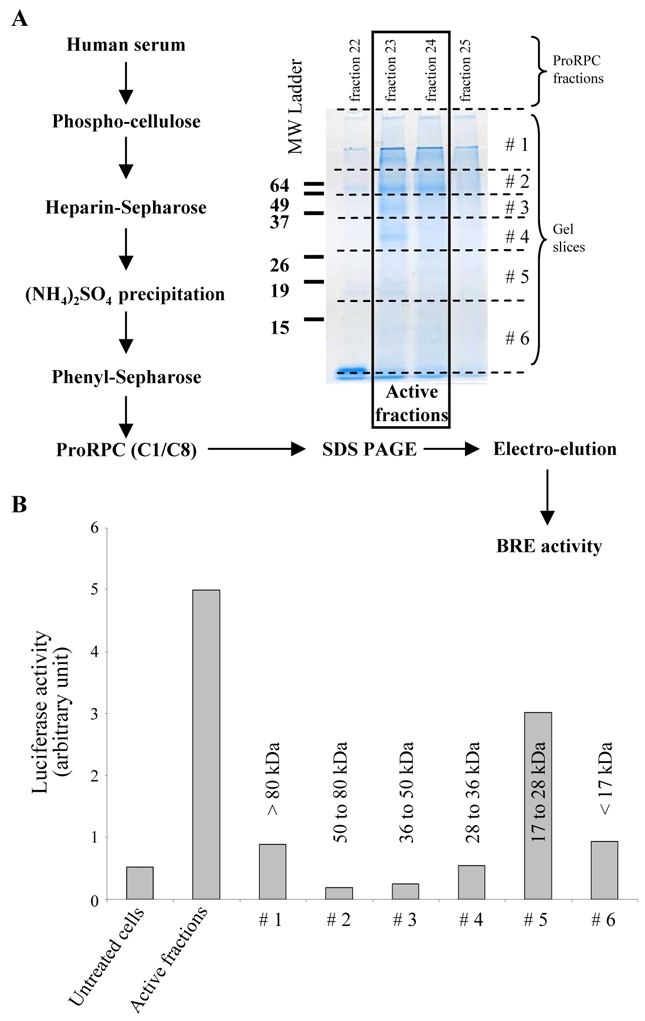

Purification and molecular weight estimation of the ALK1 ligand from human serum

We next attempted to purify the activating factor from human serum. The factor was purified approximately 100 fold from 250 ml of human serum, following the purification scheme shown in Fig. 2A. After five purification steps, the fractions eluting from the Pro-RPC column were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions. The gel lanes containing the active fractions (23 and 24) were then cut into 6 bands and the proteins in each band were electroeluted, renatured and tested for ALK1-stimulating activity. The activity was detected in band 5 which corresponded to an apparent molecular weight comprised between 17 and 28 kDa (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Purification and estimation of the molecular weight of the ALK1 ligand from the human serum.

A: Scheme of purification of ALK1 ligand from 250 ml of a pool of human sera. The proteins present in the active fractions (23 and 24) of the Pro-RPC column and the two surrounding fractions (22 and 25), as determined with the BRE reporter gene assay (see Material and Methods), were then separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. After the migration, the gel (fractions 23 and 24) was sliced into 6 parts as indicated by the dotted lines and the proteins were electro-eluted. B: NIH-3T3 cells were transiently transfected with pGL3(BRE)-luc, pALK1 and pRL-TK-luc. Transfected cells were then treated with 100 μl of either the active fractions (fraction 23 and 24) or 100 μl of the proteins eluted from each gel slice. The luciferase activities were then measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD from a representative experiment out of three.

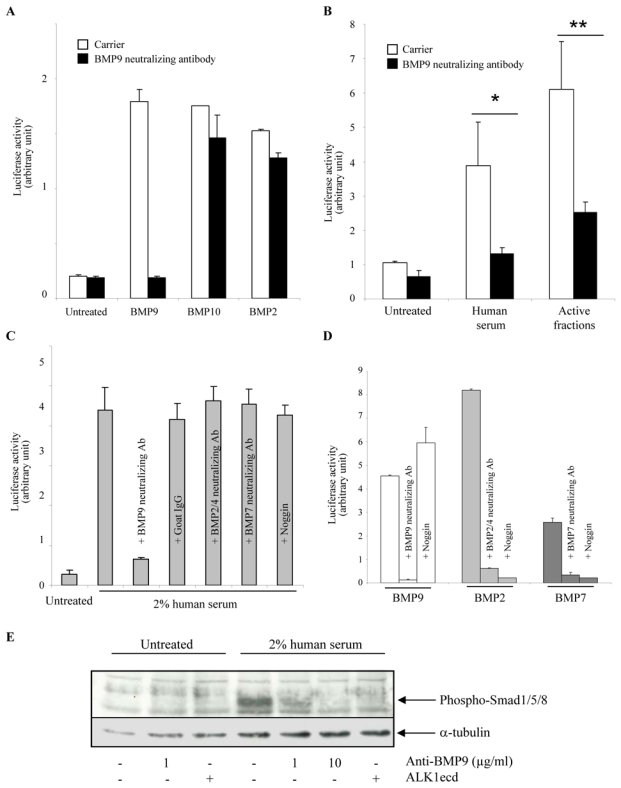

The ALK1 activity of the human serum is due to BMP9

In a recent work, we have demonstrated that BMP9 is an activating ligand for ALK113 and this was since confirmed by another group14. As the apparent molecular weight of the ALK1-stimulating activity present in human serum appears to lie between 17 and 28 kDa, we hypothesized that this activity could be due to circulating BMP9 (MW 22 kDa). To test this hypothesis, we utilized a BMP9 neutralizing antibody. This antibody was highly specific as it completely abolished the BRE-luciferase response to BMP9 while it had no effect on the BMP10-induced response (BMP 10 has the highest sequence homology with BMP9), or on the BMP2-induced response (Fig. 3A). We then tested this antibody on the ALK1-stimulating activity in serum and observed nearly complete inhibition of BRE-stimulating activity (Fig. 3B). This was also the case for the purified active fractions (fractions 23 and 24 from Fig. 2A) from human serum (Fig. 3B). To further confirm that BMP9 is the only active circulating member of the TGFβ family present in serum capable of activating the BRE promoter in ALK1-expressing NIH-3T3 cells, we tested neutralizing antibodies for other BMPs. Neutralizing BMP2/4 and BMP7 antibodies had no effect on human serum activity (Fig. 3C) while both inhibited the BRE response to either recombinant BMP2 or BMP7 (Fig. 3D). We also evaluated whether the circulating BMP antagonist noggin inhibits human serum ALK1-stimulating activity. We observed that the addition of noggin did not inhibit the ALK1-stimulating activity from human serum (Fig. 3C) while it inhibited BMP2 or BMP7 activity (Fig. 3D). We could also demonstrate for the first time that noggin did not inhibit the induction of BRE activity by recombinant BMP9 (Fig. 3D). Finally, we tested the effects of the neutralizing BMP9 antibody on serum activation of Smad1/5 phosphorylation in human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC-d). As shown in Figure 3E, human serum induced rapid and strong Smad1/5 phosphorylation, that could be inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by the addition of neutralizing anti-BMP9 antibody or by the addition of ALK1ecd. Taken together these data lead to the conclusion that the ALK1-stimulating activity of human serum is due to BMP9.

Figure 3. The ALK1 activity of the human serum is due to BMP9.

A, B, C and D: NIH-3T3 cells were transiently transfected with pGL3(BRE)-luc, pRL-TK-luc and pALK1. A: Transfected cells were then treated with BMP9 (0.1 ng/ml), or BMP10 (20 ng/ml), or BMP2 (100 ng/ml) in the presence or the absence of a neutralizing BMP9 antibody (1 μg/ml) or an isotype-matched control antibody (1μg/ml). B: Transfected cells were then treated with human serum (1%) or 100 μl of active fraction (fractions 23 and 24 of Fig. 2A). C: Transfected cells were treated with 2% human serum in the presence or the absence of neutralizing antibodies (anti-BMP9 (2 μg/ml), anti-BMP2/4 (10 μg/ml), or anti-BMP7 (10 μg/ml)) or with recombinant noggin (1 μg/ml). D: Transfected cells were treated with either BMP9 (0.05 ng/ml), BMP2 (50 ng/ml) or BMP7 (100 ng/ml) in the presence or the absence of neutralizing antibodies (anti-BMP9 (2 μg/ml), anti-BMP2/4 (10 μg/ml), or anti-BMP7 (10 μg/ml)) or with recombinant noggin (1 μg/ml). The luciferase activities were then measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown in A, B, C and D are expressed as mean values ± SD from a representative experiment out of three. E: HMVEC-d were serum-starved for 1 h and were then treated with 2% human serum for 1 h in the presence or absence of neutralizing BMP9 antibody (1 or 10 μg/ml) or ALK1ecd (100 ng/ml). Cell lysates (20 μg proteins) were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with antibodies against phosphoSmad1/5/8 or against α-tubulin.

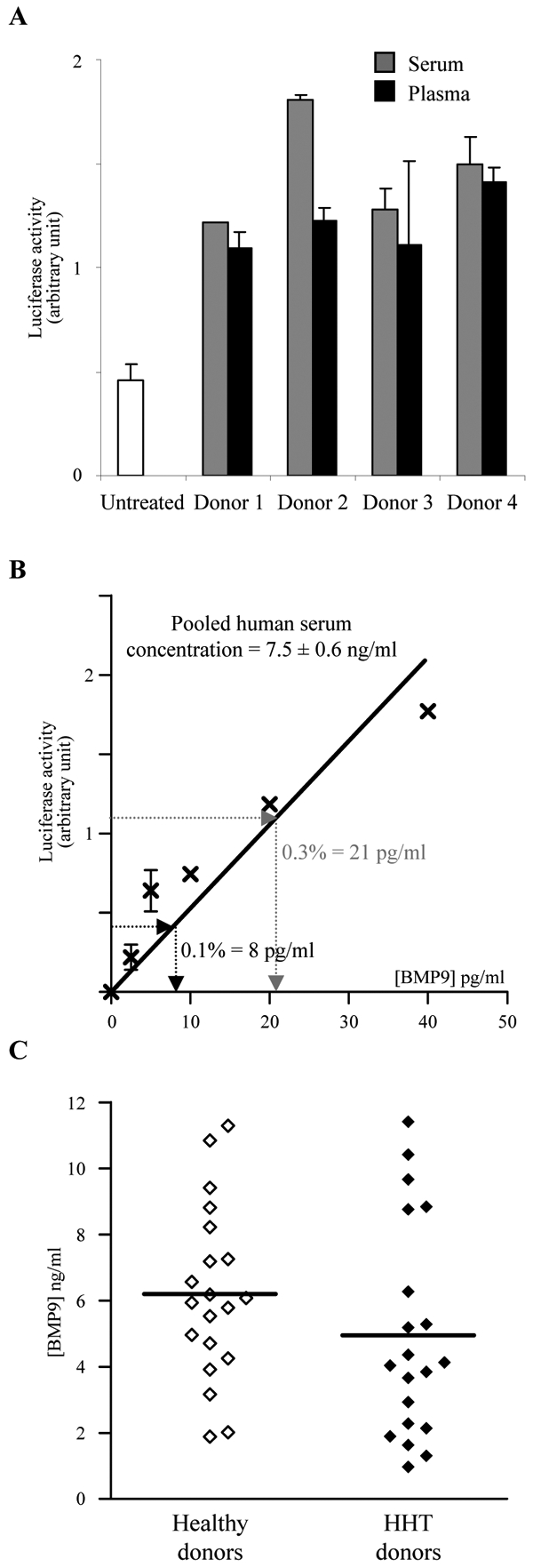

Determination of BMP9 concentration in human serum

Having demonstrated that BMP9 is present in human serum, we also evaluated its presence in human plasma. We measured BMP9 levels in the sera and the plasma of four healthy individuals and found similar levels of BRE activity in both biological fluids (Fig. 4A). Using the BRE luciferase reporter assay and recombinant mature BMP9 (R&D Systems) as a standard for calibration, we determined that the BMP9 concentration in a pool of human sera was 7.5 ± 0.6 ng/ml (Fig. 4B). BMP9 binds ALK1 and endoglin13, two receptors whose genes are mutated in HHT. This prompted us to evaluate the serum levels of BMP9 in HHT patients versus a normal population. Twenty patients with clinical features of HHT were enrolled in this study. The two populations were matched for gender ratio (8 were female and 12 were male) and age (mean = 44 years). The study of BMP9 levels in the healthy population demonstrated a mean level of circulating BMP9 very close to the one found in the pooled human sera (6.2 ± 0.6 ng/ml) with a range of variation between 2 and 12 ng/ml (Fig. 4C). As shown in Fig. 4C, no statistically significant difference in the serum level of BMP9 could be detected between healthy humans and HHT patients (6.2 ± 0.6 ng/ml versus 5.0 ± 0.7 ng/ml, respectively, n = 20). Similar data were obtained using plasma (data not shown). Sera that had high levels of BMP9 (above 8 ng/ml) were tested again in the presence of the neutralizing anti-BMP9 antibody in order to confirm that all this activity was due to BMP9. The antibody totally neutralized the activity in all samples (data not shown).

Figure 4. Determination of BMP9 concentration in human serum.

A: NIH-3T3 cells were transiently transfected with pGL3(BRE)-luc, pRL-TK-luc, pALK1. Transfected cells were treated with 0.5% of human serum or plasma of 4 different healthy donors. B: linear regression for the determination of BMP9 serum concentration. NIH-3T3 cells were transiently transfected with pGL3(BRE)-luc, pRL-TK-luc, pALK1. Transfected cells were then treated with 0.1 or 0.3% of a pool of human sera. The luciferase activities were then measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown in A and B are expressed as mean values ± SD from a representative experiment out of three. C: BMP9 serum levels measured in 20 patients with HHT and 20 healthy donors. The line indicates the mean value. The difference was not statistically significant.

BMP9 is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis in vivo

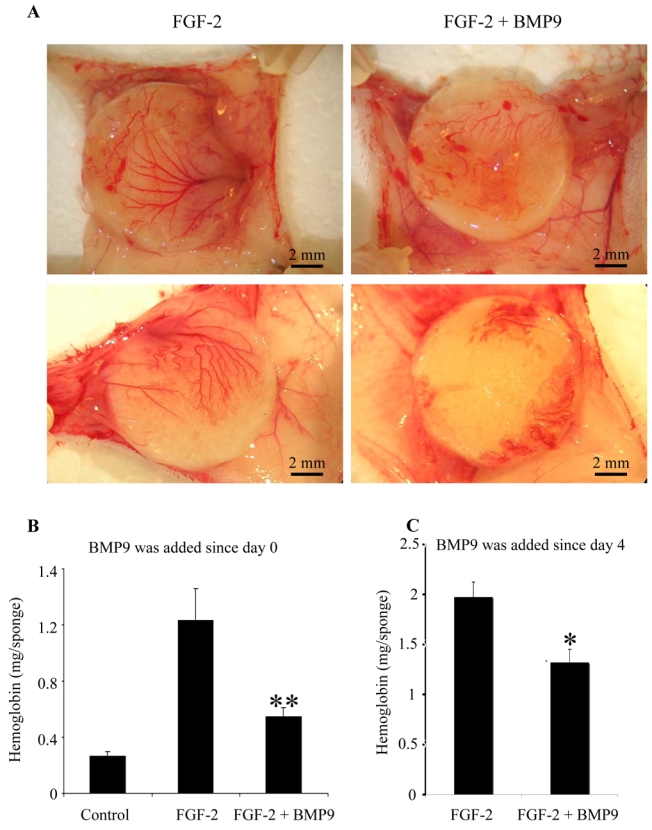

We and others have previously demonstrated that BMP9 inhibits endothelial cell migration and proliferation13,14. In addition, it was further demonstrated that BMP9 inhibited ex vivo endothelial cell sprouting from metatarsals14. Similarly, we were able to show that BMP9 inhibited endothelial sprouting from embryoid bodies derived of embryonic stem cells committed to endothelial differentiation (supl. Fig. 1). Taken together these data, suggest that BMP9 might act as an inhibitor of angiogenesis. To further characterize the anti-angiogenic activity of BMP9, we tested its effect in two in vivo angiogenic assays. First, we assessed the effect of BMP9 in the mouse subcutaneous sponge assay. In this study, Balb-C mice received under the dorsal skin a cellulose sponge hydrated with FGF-2 or FGF-2 and BMP9. Factors were re-injected into the sponge on day 1, 2 and 4 as described in Materials and Methods. The angiogenic response was then assessed on day 7. As shown in Figure 5, BMP9 treatment clearly inhibited the angiogenic response. This inhibitory effect could be quantitated by measuring the hemoglobin content of the sponges (Fig. 5B, 1.23 ± 0.22 mg with FGF-2 versus 0.54 ± 0.06 mg with FGF-2 and BMP9, p<0.05). We then looked whether BMP9 addition would also lead to destabilization of already formed vessels. To do this, Balb-C mice received a cellulose sponge hydrated with FGF-2, which was re-injected into the sponge on days 1 and 2. Angiogenesis, as measured by hemoglobin levels, was already strong by day 4 (data not shown). BMP9 was then added on day 4, 5 and 6 and the angiogenic response was assessed on day 7. Interestingly, we found that BMP9 added after the initiation of angiogenesis by FGF-2 still significantly inhibited this process (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Effect of BMP9 on angiogenesis in the mice sponge assay.

A and B: Bal-C mice received a subcutaneous cellulose sponge treated with FGF-2 (200 ng) and/or BMP9 (20 ng) under the dorsal skin. Injections in the sponge of FGF-2 and/or BMP9 diluted in PBS were performed on day 1 and day 2 and a last injection was performed on day 4 with BMP9 alone. C: Bal-C mice received a subcutaneous cellulose sponge treated with FGF-2 (200 ng) diluted in PBS under the dorsal skin. Injections of FGF-2 were performed on day 1 and day 2. BMP9 (20 ng) or PBS were injected on day 4, 5 and 6. Animals were sacrificed on day 7 and the sponges were photographed (A). Hemoglobin content was measured in 1 ml of RIP A buffer extract of the sponge and adjacent vascular network (B and C). B: Data are expressed as mean values ± SEM from a representative experiment (five mice in each groups) out of three. C: Data are expressed as mean values ± SEM of two experiments (nine mice in each groups). (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01).

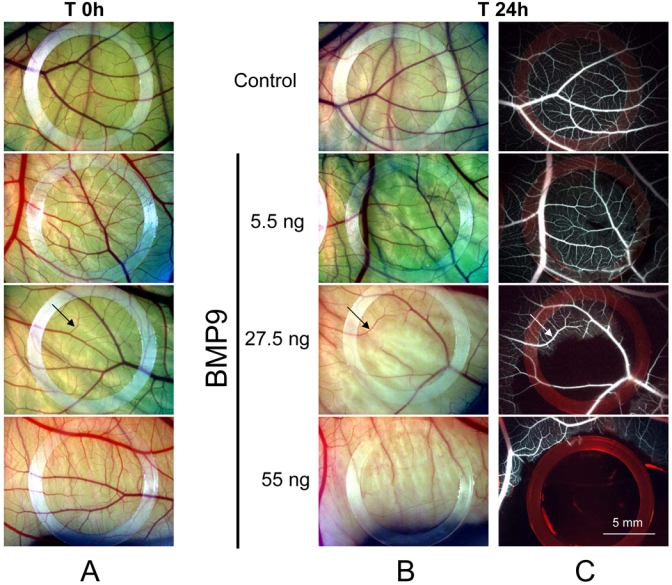

We also tested the effect of BMP9 in the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay that allows to study fetal neoangiogenesis. BMP9 or the vehicle (PBS, BSA 0.1%) was applied for 24h side by side onto the same CAM on day 9 of embryo development (Fig. 6). Four doses of BMP9 were tested (5.5, 27.5, 55 and 550 ng). BMP9 treatment impaired in a dose-dependent manner CAM angiogenesis as seen on photographs (Fig. 6B); this effect was further confirmed by FITC-Dextan injection (fig. 6C): at low dose (5.5 ng) BMP9 had minimal effect on the vasculature, at 27.5 ng only the small vessels were affected, and at 55 ng a complete disappearance of all the vessels is induced. A higher dose of BMP9 (550 ng) produced chick embryo death 4 to 6 h following its addition (data not shown). Serial cross sections of the CAM, stained either with hematoxylin/eosin, isolectin (endothelial cells) or anti-α smooth muscle actin (pericytes), show that this effect of BMP9 was not due to vascular pruning as the number of vessels was not modified (supl Fig. 2A). These results suggested that vessels were still present but not functional. Indeed, when we follow the effect of BMP9 (550 ng) at earlier time-points, we could observe constrictions and/or thrombosis of some vessels suggesting that BMP9 might regulate vascular tone (supl Fig. 2B). These irregularities in vessel diameter are also observed on CAM cross section after a 24h treatment with BMP9 (55 ng) visualized after hematoxylin/eosin labeling (supl Fig. 2C).

Figure 6. Effect of BMP9 on vessel formation in the chick chorioallantoic membrane assay.

On day 9, the CAM received either 25 μl of BMP9 (5.5 ng, 27.5 ng, 55 ng or 550 ng) or vehicle (Control). The photographs shown were taken before (T 0h) and after treatment (T 24h) and are representative of the results obtained in an additional five eggs per group. Low magnification pictures of CAMs at T 0h(A) and T 24h (B); C: 24 h after treatment, FITC dextran was injected in the CAM vessels, fluorescent images. Arrow indicates a vessel that is not affected by BMP9 treatment; arrowhead indicates a vessel that cannot be seen after BMP9 treatment.

Discussion

Angiogenesis is a complex process, requiring a finely tuned balance between numerous stimulatory and inhibitory signals. In adulthood most blood vessels remain quiescent and angiogenesis occurs only in the cycling ovary, in the endometrium and in the placenta during pregnancy, and during wound healing18. This implicates that circulating quiescence factors must exist in blood. It was previously published that human serum is able to specifically activate the Smad1/5 pathway, suggesting the presence of active BMPs in blood15. We here report that the Smad1/5-stimulating activity present in human serum is due to biologically active BMP9. Furthermore, we demonstrate using two in vivo angiogenic assays that BMP9 is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. These data lead us to propose that the circulating anti-angiogenic BMP9 could play a role as a regulator of endothelial quiescence.

We found that BMP9 was present at similar levels in both human serum and plasma, suggesting that circulating BMP9 is derived from plasma rather than from platelets. The circulating concentration of BMP9 is between 2 and 12 ng/ml, as determined with the BRE reporter gene assay using recombinant mature BMP9 as a standard, is between 2 and 12 ng/ml. This concentration is well above its EC50 (50 pg/ml, 2 pM), previously determined in microvascular endothelial cells13. In the present work, we showed that human serum activity could be inhibited by neutralizing BMP9 antibodies and by ALK1 extracellular domain,confirming that this activity is due to a factor that can bind ALK1. We have previously shown that both BMP9 and BMP10 bind to ALK113. However, we here demonstrate that the biological ALK1-stimulating activity in human serum is exclusively due to BMP9 and not to BMP10. The absence of BMP10 in blood is likely due to the pattern of BMP10 expression that appears to be restricted to the developing and postnatal heart19. In contrast, BMP9 expression is high in both embryonic and adult liver2, suggesting that this is the likely source of circulating protein. Other TGFβ family members known to activate the Smad1/5 pathway have been previously described in serum or plasma, specifically BMP7 and BMP420, 21. However, their concentrations are lower (100–400 pg/ml) and their receptor affinities are also much lower (in the nM range) than the affinity of BMP9 for ALK1 (in the pM range), suggesting that they are not circulating at biologically active levels. Furthermore, these factors appear to circulate as inactive complexes associated with antagonists such as noggin22. In contrast, we found that noggin does not inhibit BMP9- or human serum-induced BRE activity (Fig. 3C and D). This might be another reason why BMP9 is the only active circulating BMP in healthy human serum under our biological conditions.

HHT is a dominantly inherited genetic disorder (mutations of ACVRL1 or ENG), and haploinsufficiency (reduced amount of functional protein) is likely to be the cause of associated vessel malformations. One could imagine that the organism could compensate this haploinsufficiency by increasing the synthesis of the receptor ligand. However, we observed no significant difference between the serum BMP9 levels of healthy humans and HHT patients, suggesting that there is no compensation by increased BMP9 in this disease.

BMP9 has been previously shown to be a potent regulator of osteogenesis, chondrogenesis, glucose metabolism, iron homeostasis4 and a differentiation factor for cholinergic neurons3. In a recent study, we demonstrated that BMP9 is also a potent inhibitor of endothelial cell proliferation and migration13. This was since confirmed by another group who further demonstrated that BMP9 inhibited ex vivo endothelial cell sprouting from metatarsals14. In the present work, we confirmed this data in another ex vivo endothelial cell sprouting assay and further demonstrated that BMP9 is an important in vivo regulator of angiogenesis. Using the mouse sponge assay, we could show that BMP9 inhibited neoangiogenesis in response to FGF-2 but also induced destabilization of already formed vessels (Fig. 5B and C). This latter point suggests that BMP9 could be a useful tool to target tumor angiogenesis. Using the CAM assay, we found that BMP9 treatment inhibited blood circulation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6). This was not due to a decrease in vessel number but rather to vasoconstrictions and/or thrombosis. This point is interesting as BMP9 signals through BMPRII and that mutations in BMPR2 have been found responsible for familial pulmonary hypertension23. These data represent the first demonstration of in vivo effects of BMP9 on angiogenesis. As BMP9 is circulating under a biologically active form in adults, our data prompt us to suggest that BMP9 may be a systemic inhibitor of angiogenesis and a regulator of vascular tone. These data are supported by previous work demonstrating that phosphorylated Smad1, Smad5 and/or Smad8 are detectable in mouse aorta cryosections24 indicating that, in vivo, these cells constantly receive stimulation by BMPs. The role of BMP family members on vascular development has not been extensively studied. Data are not clear and often show paradoxical effects between in vitro and in vivo assays. GDF5/BMP14 was one of the first BMPs described for its pro-angiogenic activity in vivo25. BMP2 was shown to increase angiogenesis in the sponge assay and to induce neovascularization of developing tumors26 while it had no effect in the CAM assay25. Overall, in vivo data seem to indicate that BMPs acting through ALK3/ALK6 receptors are pro-angiogenic. Our data demonstrate that, in contrast to these BMPs, BMP9 inhibits angiogenesis via ALK1. This clearly separates BMPs into two categories: the pro-angiogenic BMPs that transduce via ALK3/6 and the anti-angiogenic BMPs (BMP9) that transduce via ALK1. Since all of these BMPs activate the Smad1/5 pathway, it is unlikely that this pathway represents the only signaling pathway implicated in these mechanisms. This is highly consistent with our previous work demonstrating that ALK1-mediated inhibition of endothelial proliferation and migration is Smad-independent27. In accordance with these data, it has recently been described that ALK1 directly phosphorylates endoglin, resulting in inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation28. BMP9 was also recently reported to inhibit Akt phosphorylation, which is clearly implicated in the migration of endothelial cells29. The presence of both positive and negative BMP-mediated signaling responses in endothelial cells may provide a useful paradigm for the further dissection of the mechanisms by which BMPs participate in the control of angiogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the student Solène di Prima for her helpful participation in this work. We also thank Dr J. LaMarre (University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada) for his review of the manuscript and his constant enthusiastic support. We thank Drs F. Bono and P. Schaeffer (Sanofi-Aventis,Toulouse, France) for their advice about the angiogenesis sponge assay.

Source of funding: Laurent David was supported by a CFR grant from the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique and by ARC (Association de la Recherche contre le Cancer). This research was supported by INSERM, CEA, GEFLUC (Groupement des Entreprises Françaises pour la Lutte contre leCancer, Grenoble-Dauphiné-Savoie), PHRC (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique, Hospices Civils de Lyon, grant n°27) and AMRO (Association des Malades de Rendu-Osler).

Footnotes

Disclosure: None.

References

- 1.Xiao YT, Xiang LX, Shao JZ. Bone morphogenetic protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:550–553. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller AF, Harvey SA, Thies RS, Olson MS. Bone morphogenetic protein-9. An autocrine/paracrine cytokine in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17937–17945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.24.17937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez-Coviella I, Berse B, Thies RS, Blusztajn JK. Upregulation of acetylcholine synthesis by bone morphogenetic protein 9 in a murine septal cell line. J Physiol Paris. 2002;96:53–59. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(01)00080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truksa J, Peng H, Lee P, Beutler E. Bone morphogenetic proteins 2, 4, and 9 stimulate murine hepcidin 1 expression independently of Hfe, transferrin receptor 2 (Tfr2), and IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10289–10293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603124103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson DW, Berg JN, Baldwin MA, Gallione CJ, Marondel I, Yoon SJ, Stenzel TT, Speer M, Pericak-Vance MA, Diamond A, Guttmacher AE, Jackson CE, Attisano L, Kucherlapati R, Porteous ME, Marchuk DA. Mutations in the activin receptor-like kinase 1 gene in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2. Nat Genet. 1996;13:189–195. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchuk DA, Srinivasan S, Squire TL, Zawistowski JS. Vascular morphogenesis: tales of two syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:R97–R112. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallione CJ, Richards JA, Letteboer TG, Rushlow D, Prigoda NL, Leedom TP, Ganguly A, Castells A, Ploos van Amstel JK, Westermann CJ, Pyeritz RE, Marchuk DA. SMAD4 Mutations found in unselected HHT patients. J Med Genet. 2006 doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.041517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attisano L, Carcamo J, Ventura F, Weis FM, Massague J, Wrana JL. Identification of human activin and TGF beta type I receptors that form heteromeric kinase complexes with type II receptors. Cell. 1993;75:671–680. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90488-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YG, Massague J. Smad1 recognition and activation by the ALK1 group of transforming growth factor-beta family receptors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3672–3677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goumans MJ, Valdimarsdottir G, Itoh S, Rosendahl A, Sideras P, ten Dijke P. Balancing the activation state of the endothelium via two distinct TGF- beta type I receptors. Embo J. 2002;21:1743–1753. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown MA, Zhao Q, Baker KA, Naik C, Chen C, Pukac L, Singh M, Tsareva T, Parice Y, Mahoney A, Roschke V, Sanyal I, Choe S. Crystal structure of BMP-9 and functional interactions with pro-region and receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25111–25118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.David L, Mallet C, Mazerbourg S, Feige JJ, Bailly S. Identification of BMP9 and BMP10 as functional activators of the orphan activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1) in endothelial cells. Blood. 2007;109:1953–1961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-034124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scharpfenecker M, van Dinther M, Liu Z, van Bezooijen RL, Zhao Q, Pukac L, Lowik CW, ten Dijke P. BMP-9 signals via ALK1 and inhibits bFGF-induced endothelial cell proliferation and VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:964–972. doi: 10.1242/jcs.002949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lux A, Attisano L, Marchuk DA. Assignment of transforming growth factor beta1 and beta3 and a third new ligand to the type I receptor ALK-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9984–9992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shovlin CL, Guttmacher AE, Buscarini E, Faughnan ME, Hyland RH, Westermann CJ, Kjeldsen AD, Plauchu H. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu- Osler-Weber syndrome) Am J Med Genet. 2000;91:66–67. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000306)91:1<66::aid-ajmg12>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korchynskyi O, ten Dijke P. Identification and functional characterization of distinct critically important bone morphogenetic protein-specific response elements in the Id1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4883–4891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005;438:932–936. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neuhaus H, Rosen V, Thies RS. Heart specific expression of mouse BMP-10 a novel member of the TGF-beta superfamily. Mech Dev. 1999;80:181–184. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kodaira K, Imada M, Goto M, Tomoyasu A, Fukuda T, Kamijo R, Suda T, Higashio K, Katagiri T. Purification and identification of a BMP-like factor from bovine serum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:1224–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugimoto H, Yang C, LeBleu VS, Soubasakos MA, Giraldo M, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. BMP-7 functions as a novel hormone to facilitate liver regeneration. Faseb J. 2007;21:256–264. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6837com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gazzerro E, Canalis E. Bone morphogenetic proteins and their antagonists. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006;7:51–65. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trembath RC, Thomson JR, Machado RD, Morgan NV, Atkinson C, Winship I, Simonneau G, Galie N, Loyd JE, Humbert M, Nichols WC, Morrell NW, Berg J, Manes A, McGaughran J, Pauciulo M, Wheeler L. Clinical and molecular genetic features of pulmonary hypertension in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:325–334. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valdimarsdottir G, Goumans MJ, Rosendahl A, Brugman M, Itoh S, Lebrin F, Sideras P, ten Dijke P. Stimulation of Id1 expression by bone morphogenetic protein is sufficient and necessary for bone morphogenetic protein-induced activation of endothelial cells. Circulation. 2002;106:2263–2270. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000033830.36431.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamashita H, Shimizu A, Kato M, Nishitoh H, Ichijo H, Hanyu A, Morita I, Kimura M, Makishima F, Miyazono K. Growth/differentiation factor-5 induces angiogenesis in vivo. Exp Cell Res. 1997;235:218–226. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raida M, Clement JH, Leek RD, Ameri K, Bicknell R, Niederwieser D, Harris AL. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) and induction of tumor angiogenesis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:741–750. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.David L, Mallet C, Vailhe B, Lamouille S, Feige JJ, Bailly S. Activin receptor-like kinase 1 inhibits human microvascular endothelial cell migration: Potential roles for JNK and ERK. J Cell Physiol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/jcp.21126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koleva RI, Conley BA, Romero D, Riley KS, Marto JA, Lux A, Vary CP. Endoglin structure and function: Determinants of endoglin phosphorylation by TGFbeta receptors. J Biol Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu D, Wang J, Kinzel B, Mueller M, Mao X, Valdez R, Liu Y, Li E. Dosage-dependent requirement of BMP type II receptor for maintenance of vascular integrity. Blood. 2007;110:1502–1510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-058594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.