Abstract

This study focused on the understudied group of smokers who commit to a smoking research study and then subsequently drop out before completing even one session of treatment (pre-inclusion attrition). This is an important group typically not examined in their own right, leaving little knowledge about the characteristics that differentiate them from those who complete treatment. As an initial investigation, the current study examined affective risk factors for attrition in a sample of 53 adults (79% African American; median income = $30,000–$39,999) enrolled in a smoking cessation study. Twenty-one (40%) participants never attended a session of treatment. Results indicated lower psychological distress tolerance was related to pre-inclusion attrition, but only among women. Additionally, lower physical distress tolerance corresponded to pre-inclusion attrition, but only among men. These effects remained after including other important affective factors such as anxiety sensitivity and current depressive symptoms. No other predictors examined corresponded with pre-inclusion attrition in the present sample. Results indicate need for more research attention to this at risk group of smokers who do not continue on to cessation intervention.

1. Introduction

Ample research has focused on identifying factors (e.g., depressive symptoms, withdrawal dynamics) related to relapse for those who receive smoking cessation treatment (e.g., Berlin & Covey, 2006; Piasecki, Jorenby, Smith, Fiore, & Baker, 2003). However, studies typically pay less attention to individuals who engage in “pre-inclusion attrition” defined as completing an initial screening or intake assessment but then failing to participate in any aspect of the intervention (Howard et al., 1990; Namenek, Brouwer, & Pomerleau, 2000). Of the limited research conducted on pre-inclusion attrition in smoking cessation, a handful of studies have considered individual difference factors that may limit initial treatment engagement.

Factors that may be associated with pre-inclusion attrition include self-reported cessation motivation and quit intentions (Ahluwalia et al. 2002; Schnoll et al. 2004), younger age and lower education (Ahluwalia et al. 2002; Woods et al. 2002), weight concerns (Copeland 2006), and history of psychotropic medication use (Curtin et al. 2000). Moving beyond these variables, affective vulnerabilities (e.g., depressive symptoms) have been shown to relate to poorer treatment outcome in smokers (e.g., Kassel & Hankin, 2006), and may also be useful for consideration specific to pre-inclusion attrition. Despite the extensive body of literature linking depression status or symptoms to poor cessation outcomes, these affective vulnerabilities have been unrelated to pre-inclusion attrition (El-Khorazaty et al. 2007), as well as indices of readiness to change smoking behavior and smoking treatment acceptance (Haug et al., 2005; Prochaska et al., 2004). Some evidence suggests anxiety sensitivity (AS), a dispositional trait-like characteristic reflecting the fear of anxiety-related experiences, is related to factors associated with pre-treatment attrition including motivation to quit smoking (Zvolensky et al., 2004; 2007), barriers to quitting smoking (Zvolensky et al., 2006) and early smoking lapse (e.g., Brown et al., 2001). However, a direct link from anxiety sensitivity to pre-treatment attrition has yet to be established.

There may also be other relevant vulnerabilities that have yet to be examined in relation to pre-inclusion attrition including distress tolerance which is defined as an individual’s behavioral persistence towards a goal in the presence of affective and/or physical distress (Daughters et al., 2005a; Brown et al., 2005). Low distress tolerance has been associated with greater substance use (Quinn et al., 1996), shorter length of smoking cessation and drug use abstinence (Brandon et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2002; Daughters et al., 2005a), and early substance use treatment drop out (Daughters et al., 2005b). A limitation of this literature is that studies were retrospective (Daughters et al. 2005a; Brown et al., 2002) or limited to participants who completed treatment or engaged in some treatment but failed to achieve abstinence (Brandon et al., 2003; Daughters et al., 2005b). Thus, the current literature does not highlight the potential role of distress tolerance in relation to pre-inclusion attrition in a smoking intervention.

In considering the link between distress tolerance and pre-inclusion attrition, it may be useful to conceptualize distress tolerance within the framework of negative reinforcement (Brown et al. 2005; Daughters in preparation), in which distress tolerance is considered an assessment of behavioral avoidance of or escape from affective or physical distress. This framework draws upon Baker and colleagues’ (2004) negative reinforcement model of addiction in which initially escape and ultimately avoidance of affective distress are considered the prepotent motive of addictive behavior maintenance, and is consistent with other negative reinforcement conceptualizations of smoking motivation (Eissenberg, 2004). Additionally, avoidance behavior is commonly implicated in both a lack of treatment-seeking for health problems (e.g., Moore et al., 2004) and treatment non-adherence (e.g., Waldroup, Gifford, & Kalra, 2006). Thus it is likely that those individuals who have the lowest levels of distress tolerance will also be most likely to exhibit pre-inclusion attrition from a smoking cessation intervention. Specifically, distress tolerance tasks provide an analog assessment of avoidance/escape behavior that is relevant to the behavior exhibited in not following through with treatment after an initial effort is made to attend a baseline session.

1.1 Current Study

The aim of the current study was to examine the role of psychological and physical distress tolerance as predictors of pre-inclusion attrition among a sample of adults who met entry criteria and completed a baseline assessment for a randomized control trial of a piloted behavioral activation cessation intervention for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. Given poor cessation outcomes associated with depression-related vulnerabilities (e.g., Berlin & Covey, 2006), but also the lack of findings connecting depressive symptoms to pre-inclusion attrition (El-Khorazaty et al. 2007), it is important to investigate other possible mechanisms contributing to pre-inclusion attrition in this at-risk group. We also examined the role of gender as a moderator of the relationship between distress tolerance and pre-inclusion attrition given women’s smoking behavior may be more directly driven by motivation to cope with negative affect and stress (e.g., al’Absi, 2006; Colamussi et al., 2007) while men’s smoking may be more driven by physiological or pharmacological effects of nicotine (Perkins, 2001; Perkins et al., 2006). Thus, it was expected that physical distress tolerance would have a stronger relationship with pre-inclusion attrition for men while psychological distress tolerance would have a stronger relationship with this outcome for women.

2. Methods

2.1 Procedure

The study employed screening and baseline data from a sample of 53 adult smokers participating in a randomized trial of a novel behavioral activation treatment for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. Subjects were recruited through media advertisements, as well as the use of community connections across a period of approximately 12 months. 476 potential participants were initially screened by phone for eligibility. To be deemed eligible, participants were 1) 18 to 65 years of age, 2) a regular smoker for at least one year, 3) currently smoking ≥10 cigarettes per day, 4) reporting motivation to quit smoking in the next month, and 5) scored 14 or greater on the BDI-II on a phone screen (participants with lower BDI-II scores at baseline were retained in the study). At a baseline session, all potential participants were also screened using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Individuals were excluded from the study for being outside the age range (n = 6), scoring too low on the BDI-II at phone screen (n = 213), having low motivation for quitting (n = 2), meeting criteria for a current DSM-IV disorder (n = 119), meeting criteria for any psychoactive substance use or dependence (excluding nicotine) in the last six months (n = 9), current use of psychotropic medication or participation in psychotherapy (n = 15), physical concerns contraindicating use of the nicotine patch (n = 1), current use of pharmacotherapy to aid in smoking cessation not provided by research staff (n = 3), smoking too few cigarettes or for too short a period of time (n = 50), and current use of tobacco products other than cigarettes (n = 5). Participants were assigned by cohort to one of two treatment conditions. Data were collected through a combination of structured interviews, laboratory tasks, and self-report questionnaires at baseline prior to the intervention. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland, College Park provided approval for this study.

Included in the present sample were 53 individuals who met eligibility criteria, for whom baseline data were available and who had participated in the laboratory tasks described below. Participants were on average 45.1 years of age (SD = 12.1), 41.5% were female (n = 22), 79.2% where African-American and 20.8% were non-Hispanic White.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Smoking Characteristics

Smoking history was assessed at baseline using the smoking history and current status indices agreed upon by a National Cancer Institute consensus panel (Proceedings of the National Working Conference on Smoking Relapse, 1986). This includes information such smoking rate, history and duration of previous quit attempts, number of household smokers, and age of onset of regular smoking behavior.

2.2.2 Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence

Level of nicotine dependence was assessed with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991). The FTND has shown moderate internal consistency, a single factor structure, and positive relationships with degree of nicotine intake as assessed by saliva cotinine (Heatherton et al., 1991). Internal consistency in the present sample was modest (α = .47).

2.2.3 Anxiety Sensitivity Inventory

Anxiety sensitivity was measured via self-report using the Revised Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI-R; Taylor & Cox, 2001). The ASI-R is a 36-item self-report scale that uses a 5-point likert scale (0 = very little to 4 = very much) to assess fear of anxiety related symptoms. The ASI-R has been used extensively and has sound psychometric properties. In the current sample, internal consistency was excellent (α = .96).

2.2.4 Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)

At intake, all participants were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-non-patient version (SCID-NP; Spitzer, 1983) to assess for current DSM-IV Axis I disorders present during the past year.

2.2.5 Laboratory Tasks

2.2.5.1 Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT)

Participants completed a modified computerized version of the paced auditory serial attention task (PASAT; Diehr, Heaton, Miller & Grant, 1998; Lejuez, Kahler, & Brown, 2001), an addition task that has been shown to increase subject stress levels (e.g., Brown et al., 2002). During the task, numbers are flashed sequentially across a computer screen and participants are instructed to add the current number to the previously presented number. They are then told to click on the correct sum using a keyboard provided on the computer screen. The participant receives one point for each correct answer with the total number of points earned displayed in a box on the right-hand side of the screen. The task consists of three levels which progress in difficulty. The first level of the PASAT lasts one minute and provides a three-second latency between number presentations (i.e. low difficulty) while the second level lasts for two minutes and provides a two-second latency (i.e. medium difficulty). During the third and final level, the latency between number presentations is one-second (i.e. high difficulty). The third level can last for up to seven minutes with the participant having the option to terminate the level at any time by clicking a quit button provided on the computer screen. Distress tolerance is measured as the latency in seconds to task termination. In addition, the number of points that the participant accrues over the course of the task will be recorded to control for proficiency/skill on task persistence. Finally, administration of a six item dysphoria scale occurs before the task starts and at the end of the final level of the PASAT to determine if the task increases psychological stress. This scale consists of six single-item ratings that are designed to assess moment-to-moment levels of anxiety, irritability, discomfort, and frustration (Brown et al., 2002).

2.2.5.2 Computerized Mirror-Tracing Persistence Task (MTPT-C)

The Computerized Mirror-Tracing Persistence Task (MTPT-C; Strong et al., 2003) is a computerized version of the Mirror Tracing Persistence Task (MTPT; Quinn et al., 1996). For the MTPT-C, participants are instructed to trace a dot along lines of various shapes using the computer mouse. However, to make the task similar to the original, the mouse is programmed to move the dot in the opposite direction than that showed on the screen (i.e. like a mirror). Thus, if the participant moves the mouse down, the dot would move up, and so forth. In order to increase the degree of difficulty and frustration, each time the participant moves the mouse out of the lines or stops moving the mouse for more than two seconds, a loud buzzer sounds and the dot moves back to the beginning of the shape. Similar to the PASAT, there are three rounds of the MTPT-C with each shape presented progressing in difficulty. The first two rounds last one minute each while the third round of the MTPT-C can last up to seven minutes. Participants are instructed that they have the option to terminate the task at any point during the third round by pressing on the space bar. As with the PASAT, distress tolerance is measured by the latency in seconds to task termination. Additionally, the number of errors per second (i.e., number of times the participant has to return to the starting position during the task divided by the task time) is recorded to control for effects of skill on persistence. The participant completes the dysphoria scale at both the beginning and end of the MTPT-C to determine if the task caused an elevation in psychological distress. The original version of the MTPT has been shown to increase distress and has demonstrated good reliability (alpha = .92; Brandon et al., 2003).

2.2.5.3 Physical Challenge: Breath Holding Task

Breath holding is a common task used to assess for physical distress tolerance and has been found to be predictive of length of time to smoking relapse (Brown et al., 2002; Hajek, Belcher, & Stapleton, 1987). During this task participants are instructed to take a deep breath and hold it for as long as they can. They are asked to notify the experimenter when they begin to feel uncomfortable by holding up a sign that signifies that they are feeling discomfort. However, the participants are instructed to continue holding their breath beyond that point of initial discomfort for as long as possible. Distress tolerance is measured as the latency in seconds between when the participant begins to feel uncomfortable and when they finally let out their breath. The procedure is safe and has been used in a previous study looking at distress tolerance in smokers (Brown et al., 2002).

2.5.2.4 Pain Challenge: Cold Pressor Task (CPT)

The cold pressor task is a commonly used measure of pain that involves having the participant submerge their hand in a bucket of freezing cold water (0–2 degree Celsius) a stimulus which produces a gradual escalation of pain (Willoughby, Hailey, Mulkana, & Rowe, 2002). Similar to the breath holding task, the participant is instructed to notify the experimenter when they begin to feel uncomfortable by holding up a sign that indicates so. However, they are told to continue to keep their hand immersed in the cold water for as long as possible. Distress tolerance is measured as the latency in seconds between when the participant begins to feel uncomfortable and when they finally terminate the task by taking their hand out of the water.

2.2.6 Smoking Cessation Self-efficacy

Smoking cessation self-efficacy was measured at baseline using a nine-item self-report scale that has been used in previous smoking research to assess a participant’s perception of how tempted they would be to smoke across nine situations (Velicer Diclemente, Rossi, & Prochaska, 1990). Internal consistency for the measure in the present sample was adequate α = .82.

2.2.7 Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI)

The Beck Depression Inventory-II was used to assess for current elevations in depressed mood. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 21 item self report measure that assesses depressive symptoms over the past week. Questions are rated on a 4-point likert scale where a value of 0 means that the statement does not describe the individual at all and a value of 3 means that it describe them very well. According to the BDI-II, a score of 0–13 indicates minimal depression, 14–19 is mild depression, 20–28 is considered moderate depression, and 29–63 indicates severe depression. Internal consistency for the measure in the current sample was good (α = .87).

3. Data Analyses

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square analyses were employed for preliminary group comparisons. The distributional properties of all non-categorical variables were assessed to determine they met statistical assumptions for the analyses. Distributional properties of time persisted on the breath holding, cold pressor, and mirror tracing tasks did not meet statistical assumptions for general linear model analyses, each being significantly skewed (s = 1.66, z = 5.17; s = 2.68, z = 8.38; s = −.590, z = −2.68; SE = .32). Applying a log transformation corrected skewness for the breath holding and cold pressor tasks respectively (s = −.04, z = −.12; s = −.07, z = −.21; s = .12), and applying a reflection and log transformation corrected skewness for the mirror tracing task (s = .12, z = .37). Transformed variables were used in subsequent analyses.

In order to examine the relationship between psychological and physical distress tolerance and pre-inclusion attrition, participants were divided into those who completed the baseline assessment and who attended at least one session of treatment to which they had been randomized (n = 32), and those who completed the baseline assessment and never attended a session of treatment (n = 21). Multivariate generalized linear model (GLM) analyses were then used to test the differences across pre-inclusion attrition status on persistence on the four distress tolerance tasks, as well as to examine the potential moderating role of gender in these relationships. For the analyses, the four psychological and physical distress tolerance measures were the dependent variables and gender and pre-inclusion attrition status, as well as the interaction of these variables, were entered as fixed factors. When the multivariate F test was significant, subsequent univariate analyses were conducted to evaluate the significance of pre-inclusion attrition status and gender for specific dependent variables, protecting against multiple comparisons (Tabachnik & Fidell, 2001).

4. Results

4.1. Distress Tolerance Descriptives for full sample

4.1.1 Psychological Distress Tolerance

Participants persisted on the PASAT for an average of 273.4 seconds (SD = 162.3) and 55.8% quit the task before it was finished. Paired t-tests indicated a significant increase in self-reported negative affect during the PASAT (p < .001), suggesting the task was psychologically stressful. Repeated measures analysis indicated no relationship between skill during the second level or increases in negative affect and quitting on the PASAT (ps >.3). Time until quitting the task was used as an indicator of psychological distress tolerance as the distribution was not significantly skewed (s = −.59, z = 1.84; SE = .32).

For the Mirror Tracing Persistence task, participants persisted for an average of 301.0 seconds (SD = 144.6) and 50.9% quit the task. Similar to the PASAT, paired t-tests indicated a significant increase in self-reported negative affect during the MTPT (p<.001), indicating the task was sufficiently stressful. In order to control for skill on the MTPT-C, the number of errors per second (EPS) was calculated by dividing the MTPT-C time by the number of errors. EPS was unrelated to MTPT-C duration [r(53)= .24, p=.08]. Correlation in persistence across the transformed MTPT-C variable and the PASAT was significant (r(53)=.42, p<.001).

4.1.2 Physical Distress Tolerance

Overall, participants persisted with the Breath Holding task (BH) for an average of 37.2 seconds (SD=14.0). The difference score was calculated by subtracting the time at which the participant first began to feel discomfort from their overall breath holding duration. The mean difference score for BH was 12.4 seconds (SD=7.9). With respect to the Cold Pressor task (CP), the average amount of time they persisted on the task was 56.2 seconds (SD= 50.1), and the difference score was 26.5 seconds (SD=33.0). As expected the transformed difference scores on the two tasks were significantly correlated, r(53)=.65, p<.001.

4.2 Primary comparisons across pre-inclusion attrition status

First, pre-inclusion attrition status differences were examined for demographics, smoking history, current depressive symptoms, anxiety sensitivity, quit motivation, and physical and psychological distress tolerance. Results are reported in Table 1. Individuals characterized by pre-inclusion attrition did not differ significantly on age, gender, ethnicity, education level, or employment status nor did they differ substantively on any smoking history characteristics or quit motivation. However, level of anxiety sensitivity was marginally higher in the pre-inclusion attrition group (p = .07), thus this variable was included in the multivariate model. We also covaried for level of depressive symptoms at baseline given the purpose of the larger study.

Table 1.

Comparisons on demographic, smoking history, and affective variables across preinclusion attrition status.

| Characteristics | Pre-Inclusion Attrition Group(n=21) | Treatment Attenders(n=32) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Variables

| ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 46.9 (11.5) | 44.0 (12.5) |

| Gender, % female | 47.6 | 37.5 |

| Ethnicity, % African-American | 81.0 | 78.1 |

| Employment Status, (% unemployed) | 35.0 | 28.1 |

| Education (%) | ||

| HS Graduate/GED or lower | 38.1 | 31.3 |

| Some College/Tech School/College Graduate | 61.9 | 68.8 |

| Household Income (%) | ||

| $0−$39,9999 | 76.2 | 56.7 |

| $40,000−$79,999 | 14.3 | 30.0 |

| $80,000+ | 9.5 | 13.3 |

|

| ||

| Smoking History Variables, (Mean (SD))

| ||

| Length of smoking history in years | 26.5 (11.6) | 23.3 (11.5) |

| Level of nicotine dependence | 5.9 (2.0) | 5.2 (2.0) |

| Average Cigarettes Per Day | 18.0 (10.6) | 16.6 (7.2) |

| Number of prior quit attempts | 4.8 (4.4) | 3.5 (3.1) |

| Current self-reported motivation to quit | 8.5 (1.8) | 9.0 (1.2) |

|

| ||

| Affective Variables

| ||

| Anxiety Sensitivity (ASI) Total Score, mean (SD) (p=.07) | 25.0 (9.2) | 18.7 (13.0) |

| BDI score, mean (SD) | 12.1 (8.2) | 8.6 (7.1) |

|

| ||

| Distress Tolerance Variables

| ||

| PASAT (M(SD)) | 217.68 (176.71) | 343.33 (116.8) |

| MTPT (M(SD))* | .94 (1.18) | 1.10 (1.17) |

| CPT (M(SD))* | 1.05 (.51) | 1.32 (.39) |

| BH (M(SD))* | .96 (.29) | 1.07 (.24) |

Note: Denotes variables that have been transformed;

No significant group differences were identified across demographic, smoking history, affective, or distress tolerance variables.

4.3 Multivariate Generalized Linear Models

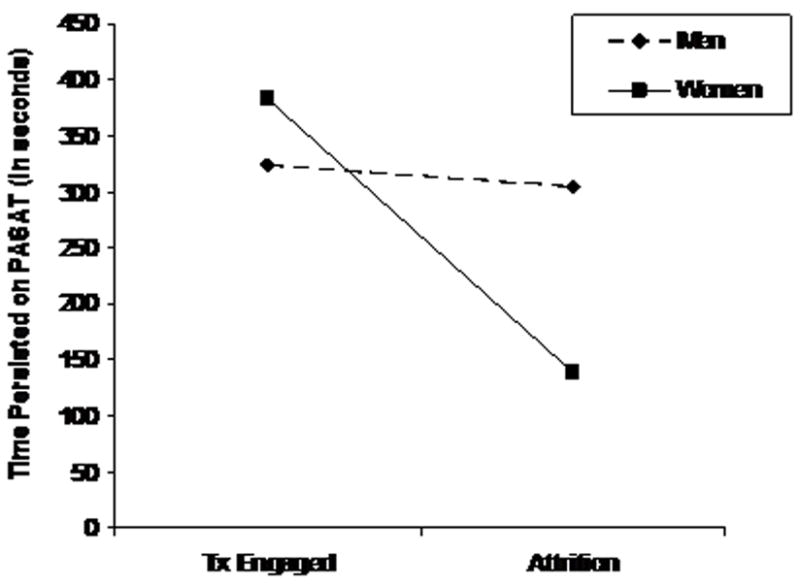

The general multivariate model assessing differences in psychological and physical distress tolerance variables across pre-inclusion attrition status was significant (F6,40 = 3.60, p = .006) as was the overall model for the gender by pre-inclusion attrition status interaction (F6,40 = 3.00, p = .02), although the general model for gender was not significant. Tests of between subject effects indicated participants in the pre-inclusion attrition group persisted on the PASAT for a shorter period of time (F1,49 = 10.66, p = .002), although this must be interpreted in the presence of a significant gender by pre-inclusion attrition status interaction for persistence on the PASAT (F1,49 = 7.84, p = .007). Analysis of marginal means with Bonferroni correction for post hoc comparisons indicated that women in the pre-inclusion attrition group persisted for a significantly shorter time on the PASAT (M = 139.1 (SD = 162.7)) than both men (M = 323.7 (SD = 130.0)) and women (M = 382.7 (SD = 75.7) in the treatment engagement group. See Figure 1. There were no group differences or group by gender interaction on the MTPT-C.

Figure 1.

The interaction between psychological distress tolerance (PASAT) and gender in predicting preinclusion attrition status.

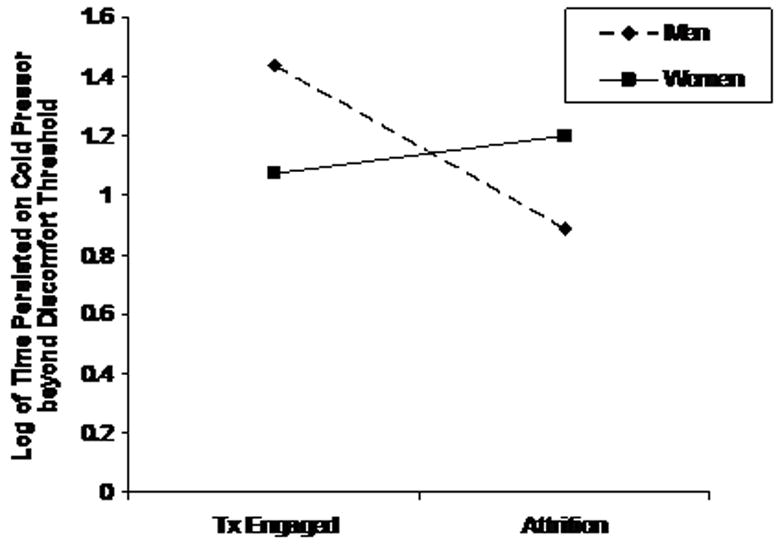

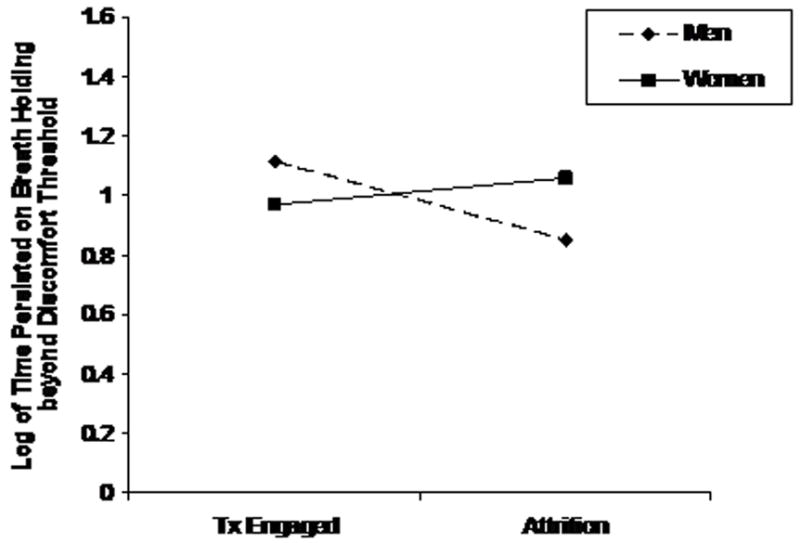

Additionally, there was a significant gender by pre-inclusion attrition status interaction for persistence on both the cold pressor task (F1,49 = 7.32, p = .01) and the breath holding task (F1,49 = 5.40, p = .03). See Figures 2 and 3. In both cases, analysis of marginal means with Bonferroni correction indicated that men who were in the treatment engagement group persisted significantly longer on the cold pressor and breath holding tasks, respectively (M = 1.4, (SD = .36); M = 1.1 (SD = .26)) than those men who were in the pre-inclusion attrition group (M = .92, (SD = .51); M = .86 (SD = .27)). However, pre-inclusion attrition status was not associated with physical distress tolerance among women.

Figure 2.

The interaction between physical distress tolerance (Cold Pressor) and gender in predicting preinclusion attrition status.

Figure 3.

The interaction between physical distress tolerance (Breath Holding) and gender in predicting preinclusion attrition status.

5. Discussion

The current study was a preliminary examination of the relationship between psychological and physical distress tolerance with pre-inclusion attrition from a behavioral activation cessation intervention for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. Consistent with expectations, lower psychological distress tolerance was related to pre-inclusion attrition, but only among women. Additionally, lower physical distress tolerance also corresponded to pre-inclusion attrition but only among men. Across analyses, these effects remained after including other important affective factors such as anxiety sensitivity and current depressive symptoms. Interestingly, no other predictors examined corresponded with pre-inclusion attrition in the present sample. Findings have implications for the role of distress tolerance as a putative risk factor for pre-inclusion attrition in the continuum of poor smoking cessation outcomes.

In the current study, women who dropped out after the initial baseline persisted approximately half as long on average on the psychological distress tolerance task as men regardless of attrition status, as well as women who continued on to treatment. As expected, physical distress tolerance predicted pre-inclusion attrition status but only among men, with those who persisted for a shorter period of time more likely to drop out prior to entering treatment. Thus, women and men who were particularly prone to engage in avoidance or escape behavior in the presence of affective (women) or physical (men) distress may have difficulty persisting through even the initial steps of their effort to quit smoking; a finding that is especially interesting given that motivation to quit was not related to pre-inclusion attrition. A substantial literature indicates that among smokers, women may more frequently regulate negative affect through smoking (c.f., Reynoso, Susabda, & Cepeda-Benito, 2005; al’Absi, 2006) and have their ability to quit smoking more greatly impacted by stressful life events (e.g., McKee, Maciejewski, Falba, & Mazure, 2003). Our findings build upon and extend this literature by suggesting a woman’s behavioral response (e.g., avoidance) to such forms of affective distress that occur even prior to quitting may be especially deleterious to her ability to commit to cessation treatment.

Similar to our findings with women and affective distress, the current results suggest that among men, a tendency to engage in avoidance or escape behavior in response to physical distress may be a considerable barrier to effective smoking treatment engagement. It has been argued that men are more inclined to smoke cigarettes primarily for the direct reinforcement of nicotine as opposed to non-pharmacological factors (Perkins, 2001; Perkins et al., 2006), and they may benefit more from nicotine replacement therapies which target directly these pharmacological mechanisms (Cepeda-Benito, Reynoso, & Erath, 2004). Gender differences may also exist in sensitivity to the rewarding effects of nicotine, such as its analgesic effects (Jamner, Girdler, Shapiro, & Jarvik, 1998). Nicotine administration has been found to increase pain threshold and tolerance in men, but not in women (Jamner et al., 1998), although findings are not consistent across all studies. Although speculative, it may be that ability to persist through the interoceptive symptoms motivating smoking behavior may be particularly relevant to men’s willingness to pursue smoking treatment.

5.1. Conclusion

Despite limitations including a small sample characterized by elevated depressive symptoms and a limited number of covariates, this is the first study to examine the relationship between psychological and physical distress tolerance and pre-inclusion attrition from a smoking cessation intervention. Thus a challenge is developing effective strategies for targeting and recruiting both men and women who may be particularly likely to engage in treatment avoidance behavior and subsequently unlikely to continue with a cessation program. It would also be useful to further explore the gender differences here both as they relate to pre-inclusion attrition but also to the extent that they shed light on cessation outcomes, with somewhat different targets possibly emerging across gender (i.e., psychological distress tolerance for women, physical distress tolerance for men). Combined with the uniqueness of our sample in the high representation of low income minority smokers who are typically underrepresented in smoking cessation research (El-Khorazatay et al., 2007) and at risk for poor cessation outcomes (Moolchan et al., 2007), the current study suggests how the construct of distress tolerance may be helpful to marshal support needed to help individuals commit to treatment while noting the importance of considering the role of demographic variables in this relationship.

Table 2.

Spearman Rank Correlations among Physical and Psychological Distress tolerance tasks

p<.05;

p<.01

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants R01 DA15375 and R01 DA18730 (PI: Lejuez), and K23 DA023143 (PI: MacPherson).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahluwalia JS, Richter K, Mayo MS, Ahluwalia HK, Choie WS, Schmelzle KH, Resnicow K. African American smokers interested and eligible for a smoking cessation clinical trial. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12:206–212. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical responses to psychological stress and risk for smoking relapse. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2006;59:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory II manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin I, Covey LS. Pre-cessation depressive mood predicts failure to quit smoking: the role of coping and personality traits. Addiction. 2006;101:1814–1821. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Herzog TA, Juliano LM, Irvin JE, Lazev AB, Simmons NV. Pretreatment task persistence predicts smoking cessation outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:448–456. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Ramsey SE. Anxiety sensitivity: Relationship to negative affect smoking and smoking cessation in smokers with past major depressive disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:887–899. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;112:448–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:713–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda-Benito A, Reynoso JT, Erath S. Metaanalysis of the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation: differences between men and women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:712–722. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colamussi L, Bovbjerg DH, Erblich J. Stress- and cue-induced cigarette craving: effects of a family history of smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland AL, Marin PD, Geiselman PJ, Rash CJ, Kendzor DE. Predictors of pretreatment attrition form smoking cessation among pre- and postmenopausal, weight-concerned women. Eating Behaviors. 2006;7:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin L, Brown RA, Sales SD. Determinants of attrition from cessation treatment in smokers with a history of major depressive disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:134–142. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Psychological distress tolerance and duration of most recent abstinence attempt among residential treatment-seeking substance abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005a;19:208–211. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Distress tolerance as a predictor of early treatment dropout in a residential substance abuse treatment facility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005b;114:729–734. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters S, Reynolds E, MacPherson L, Kahler CW, Danielson CK, Zvolensky M, Lejuez CW. Negative reinforcement and early adolescent externalizing and internalizing symptoms: The moderating role of gender and ethnicity. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.001. in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehr MC, Heaton RK, Miller W, Grant I. The paced auditory serial addition task (PASAT): Norms for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment. 1998;5:375–387. doi: 10.1177/107319119800500407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khorazaty MN, Johnson AA, Kiely M, El-Mohandes AAE, Subramanian S, Laryea HA, Murray KB, Thornberry JS, Joseph JG. Recruitment and retention of low-income minority women in a behavioral intervention to reduce smoking, depression, and intimate partner violence during pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:233–250. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T. Measuring the emergence of tobacco dependence: the contribution of negative reinforcement models. Addiction. 2004;99(S1):5–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, Belcher M, Stapleton J. Breath-holding endurance as a predictor of success in smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 1987;12:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug NA, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ, Rosen AB, Tsoh JY, Humfleet G, Delucchi K, Rossi JS, Redding CA, Eisendrath S. Acceptance of nicotine dependence treatment among currently depressed smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2005;7:217–24. doi: 10.1080/14622200500055368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard KI, Cox WM, Saunders SM. Attrition in substance abuse comparative treatment research: The illusion of randomization. National Institute on Drug Abuse Monograph Series. 1990;140:66–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamner LD, Girdler SS, Shapiro D, Jarvik ME. Pain inhibition, nicotine, and gender. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;6:96–106. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Hankin BL. Smoking and depression. In: Steptoe A, editor. Depression and physical illness. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 321–347. [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Brown RA. A modified computer version of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT) as a laboratory-based stressor. The Behavior Therapist. 2001 Summer;(1):290–293. [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Maciejewski PK, Falba T, Mazure CM. Sex differences in the effects of stressful life events on changes in smoking status. Addiction. 2003;98:847–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolchan ET, Fagan P, Fernander AF, Velicer WF, Hayward MD, King G, Clayton RR. Addressing tobacco-related health disparities. Addiction. 2007;102(S2):30–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PJ, Sickel AE, Malat J, Williams D, Jackson J, Adler N. Psychosocial factors in medical and psychological treatment avoidance: The role of the doctor-patient relationship. Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9:421–433. doi: 10.1177/1359105304042351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namenek Brouwer RJ, Pomerleau CS. “Prequit attrition” among weight-concerned women smokers. Eating Behaviors. 2000;2:145–151. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(00)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. Smoking cessation in women: Special considerations. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:391–411. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Doyle T, Ciccocioppo M, Conklin C, Sayette M, Caggiula A. Sex differences in the influence of nicotine dose instructions on the reinforcing and self-reported rewarding effects of smoking. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:600–607. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: I. Abstinence distress in laspers and maintainers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;112:3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proceedings of the National Working Conference on Smoking Relapse, 1986

- Reynoso J, Susabda A, Cepeda-Benito A. Gender differences in smoking cessation. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2005;27:227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ, Rossi JS, Redding CA, Rosen AB, Tsoh JY, Humfleet GL, Eisendrath SJ, Meisner MR, Hall SM. Depressed smokers and stage of change: Implications for treatment interventions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn EP, Brandon TH, Copeland AL. Is task persistence related to smoking and substance abuse? The application of learned industriousness theory to addictive behaviors. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;4:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Schnoll RA, Rothman RL, Lerman C, Miller SM, Newman H, Movsas B, Sherman E, Ridge JA, Unger M, Langer C, Goldberg M, Scott W, Cheng J. Comparing cancer patients who enroll in a smoking cessation program at a comprehensive cancer center with those who decline enrollment. Head & Neck. 2004;26:278–286. doi: 10.1002/hed.10368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL. Psychiatric diagnosis: Are clinicians still necessary? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1983;24:399–411. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(83)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Daughters SB, Marinello M, Kahler CW, Brown RA. Computerized mirror tracing task version. 2003:1. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4. Allyn and Bacon; Boston, Massachusetts: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Cox BJ. An expanded Anxiety Sensitivity Index: Evidence for a hierarchical structure in a clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1998;12:463–483. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(98)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Diclemente CC, Rossi JS, Prochaska JO. Relapse situations and self-efficacy: An integrative model. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:271–283. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90070-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldroup WM, Gifford EV, Kalra P. Adherence to smoking cessation treatments. In: O’Donohue WT, Levensky ER, editors. Promoting treatment adherence: A practical guidebook for healthcare providers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2006. pp. 235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby SG, Hailey BJ, Mulkana S, Rowe J. The effect of laboratory-induced depressed mood state on responses to pain. Behavioral Medicine. 2002;28(1):23–31. doi: 10.1080/08964280209596395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods MN, Harris KJ, Mayo MS, Catley D, Scheibmeir M, Ahluwalia JS. Participation of African Americans in a smoking cessation trial: a quantitative and qualitative study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2002;94:609–618. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Baker KM, Leen-Feldner EW, Bonn-Miller MO, Feldner MT, Brown RA. Anxiety sensitivity: Association with intensity of smoking-related withdrawal symptoms and motivation to quit. Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2004;33:114–125. doi: 10.1080/16506070310016969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bonn-Miller MO, Feldner MT, Leen-Feldner E, McLeish AC, Gregor K. Anxiety sensitivity: Concurrent association with negative affect smoking motives and abstinence self-confidence among young adult smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Bonn Miller MO, Bernstein A, Yartz AR, Gregor KL, et al. Incremental validity of anxiety sensitivity in terms of motivation to quit, reasons for quitting, and barriers to quitting among community-recruited daily smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2007;9:965–975. doi: 10.1080/14622200701540812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]