Abstract

Infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) causes a dysregulation of the immune system. This is caused by HIV-specific as well as non-specific mechanisms and has not been explained fully. In particular, knowledge is lacking about the potential role of host-mediated immunosuppressive mechanisms. During recent years it has become evident that a subpopulation of T cells [T regulatory (Tregs)] play a major role in sustaining tolerance to self-antigens. To investigate the influence of initiation of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) on the Treg level in HIV-infected patients we have conducted a prospective study enrolling treatment-naive HIV-infected patients just prior to starting treatment with HAART, measuring levels of Tregs by flow cytometry and mRNA expression of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) at weeks 0, 4, 12 and 24 of treatment. In this prospective study neither the percentage of CD4+CD25high+ nor the expression of FoxP3 changed significantly during 24 weeks of HAART. Furthermore, HIV patients have higher Tregs measured as percentages of CD4+CD25high+ cells paralleled by higher levels of FoxP3 compared with healthy controls. The elevated level of Tregs was found to be independent of both immunological and virological status, indicating that initiation of HAART has minor effects on the Treg level in HIV-infected patients.

Keywords: flow cytometry/FACS, highly active anti-retroviral therapy, HIV, immune regulation, Tregs

Introduction

Infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is characterized by progressive immunodeficiency [1], immune activation and depletion of CD4+ cells [2]. Chronic immune activation in HIV infection is a strong prognostic marker for the decline in CD4+ cells and disease progression [1]. Disease progression in HIV-infected patients can be delayed by treatment with highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART). HAART results in diminished viral replication and increased number of CD4+ cells [3].

The dysregulation of the immune system in HIV infection has not been explained fully. Knowledge is lacking about the potential role of host-mediated immunosuppressive mechanisms. During recent years it has become evident that a subpopulation of T cells called regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a crucial role in sustaining tolerance to self-antigens [4,5]. Tregs suppress T cell activation resulting in down-regulation of immune activation, including reduction in anti-tumour immunity, graft rejection and graft-versus-host disease [6]. Finally, Tregs are believed to play a role in the regulation of chronic viral infections, including HIV. Thus Tregs are believed to be able to down-regulate the chronic immune activation seen in HIV infection, making Tregs a key element in the understanding of the interaction between the host immune system and HIV [7,8]. However, Tregs might be beneficial as down-regulators of the unbeneficial immune activation or, in contrast, they might have a harmful effect if they down-regulate HIV-specific responses [9]. So far, no studies have been able to conclude whether Tregs hasten or delay HIV infection. Tregs express CD4 and CD25 and can be identified by flow cytometry. Furthermore, the expression of the gene forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) is proposed as an accurate measurement for Tregs[10].

The present study was designed to examine associations between immunodeficiency, immune activation and levels of Tregs in HIV-infected patients. A prospective study enrolling treatment-naive HIV-infected patients just prior to starting treatment with HAART was conducted. Tregs levels were measured by flow cytometry and mRNA expression of FoxP3 at weeks 0, 4, 12 and 24 of treatment. Comparisons between HIV-infected patients with CD4 counts above and below 200 cells/µl and comparisons of HIV-infected patients to healthy controls were conducted.

Patients and methods

Twenty-six HIV-infected patients and 11 healthy controls were included from the Departments of Infectious Diseases, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hvidovre or Rigshospitalet from January 2006 to August 2006. Patients were enrolled just before starting HAART and were all naive to any anti-retroviral treatment. They were followed for 24 weeks with blood samples at weeks 0, 4, 12 and 24. Stratification of patients into two groups with CD4 counts </≥ 200 cells/µl was performed to investigate the relation between Tregs and status of the immune system. One patient was excluded from the study due to treatment interruption. HIV-negative controls were recruited from hospital personnel and were age- and sex-matched. The clinical characteristics of HIV-infected patients and controls are presented in Table 1. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid blood was used to obtain a full blood count and for flow cytometry. Viral load was determined using COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan with a threshold of 40 copies/ml. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from heparin blood by means of density gradient centrifugation (Histopaque, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 518 g for 25 min, were washed twice in RMPI-1640 (Gibco, Carlsbat, CA, USA) and used for enrichment of CD4+ cells. RNA was extracted from the CD4+ cells, and the expression of mRNA FoxP3 was determined by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the 26 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients and the 11 controls.

| Sex | Age (years) | CD4 count (cells/µl) week 0 | CD4 count (cells/µl) week 24 | HIV-RNA (copies/ml) week 0 | HIV-RNA (copies/ml) week 24 | HIV-related illness | HAART | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | ||||||||

| 1 | m | 44 | 44 | 246 | 221 000 | 40 | PCP, Karposi's sarcoma | TDF, FTC, LPV, RTV |

| 2 | m | 44 | 270 | 360 | 472 | 40 | ABV, 3TC, AZV, RTV | |

| 3 | m | 52 | 74 | 345 | 1 000 000 | 40 | ABV, 3TC, AZV, RTV | |

| 4 | f | 26 | 32 | ND | 106 000 | ND | PCP, TB | TDF, FTC, LPV, RTV |

| 5 | m | 45 | 51 | 191 | 40 900 | 40 | 3TC, AZT, D4T | |

| 6 | m | 47 | 217 | 325 | 433 000 | 40 | ABV, 3TC, AZV, RTV | |

| 7 | m | 43 | 368 | 280 | 999 000 | 51 | ABV, 3TC, D4T | |

| 8 | m | 43 | 220 | 455 | 269 000 | 40 | TDF, FTC, LPV, RTV | |

| 9 | f | 31 | 263 | 655 | 74 500 | 40 | 3TC, AZT, LPV, RTV | |

| 10 | m | 35 | 253 | 429 | 46 300 | 40 | ABV, 3TC, D4T | |

| 11 | m | 34 | 261 | 602 | 323 000 | 67 | Karposi's sarcoma | ABV, 3TC, D4T |

| 12 | f | 38 | 23 | 218 | 84 100 | 40 | 3TC, DDI, LPV, RTV | |

| 13 | m | 25 | 210 | 430 | 40 568 | 39 | TDF, FTC, D4T | |

| 14 | m | 69 | 194 | 329 | 262 000 | 40 | ABV, 3TC, D4T | |

| 15 | m | 40 | 55 | 275 | 747 000 | 40 | PCP | ABV, 3TC, D4T |

| 16 | m | 47 | 190 | 630 | 484 795 | 83 | 3TC, AZT, LPV, RTV | |

| 17 | m | 37 | 224 | 321 | 214 000 | 40 | TDF, FTC, D4T | |

| 18 | m | 31 | 271 | 486 | 45 700 | 40 | ABV, 3TC, D4T | |

| 19 | m | 27 | 204 | 321 | 97 600 | 40 | ABV, 3TC, D4T | |

| 20 | m | 27 | 220 | 530 | 118 670 | 40 | TDF, FTC, D4T | |

| 21 | m | 61 | 280 | 330 | 8 637 | 39 | ABV, 3TC D4T | |

| 22 | f | 25 | 180 | 295 | 30 700 | 40 | 3TC, AZT, LPV, RTV | |

| 23 | m | 48 | 206 | 422 | 65 800 | 40 | TDF, FTC, LPV, RTV | |

| 24 | m | 31 | 231 | 308 | 14 700 | 44 | ABV, 3TC, AZV, RTV | |

| 25 | m | 50 | 143 | 201 | 1 000 000 | 40 | ABV, 3TC, AZV, RTV | |

| 26 | m | 39 | 160 | 241 | 44 300 | 40 | TDF, FTC, LPV, RTV | |

| Median | 40 | 208 | 329 | 101 800 | 40 | |||

| Control no. | ||||||||

| 1 | m | 47 | 731 | |||||

| 2 | m | 36 | ND | |||||

| 3 | f | 39 | 698 | |||||

| 4 | m | 47 | 1088 | |||||

| 5 | m | 27 | 721 | |||||

| 6 | m | 34 | 781 | |||||

| 7 | m | 68 | 910 | |||||

| 8 | m | 25 | 529 | |||||

| 9 | m | 33 | 509 | |||||

| 10 | m | 52 | 691 | |||||

| 11 | m | 41 | 703 | |||||

| Median | 38 | 712 | ||||||

m, male; f, female; n.d., not determined; TDF, Tenofovir; FTC, emtricitabin; LPV, lopinavir; RTV, ritonavir; ABV, abacavir; 3TC, lamivudin; AZV, atazanavir; AZT, zidovudin; D4T, efavirenz; DDI, didanosin; PCP, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia; TB, tuberculosis; HAART, highly active anti-retroviral therapy.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

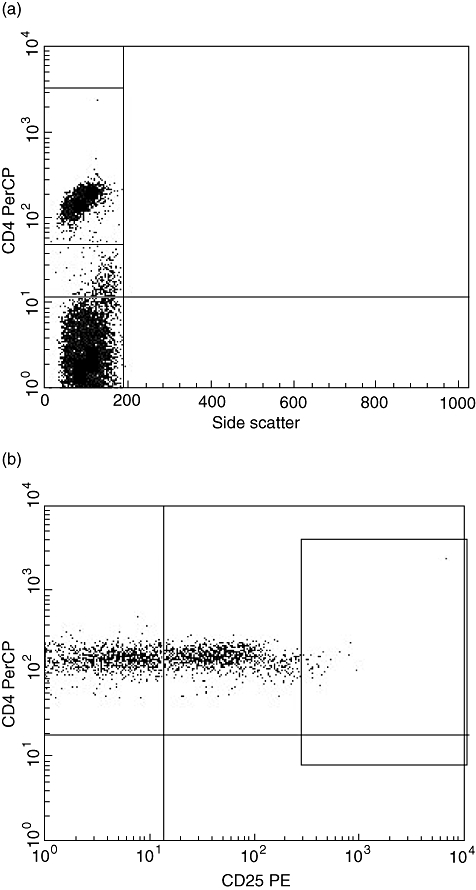

Determination of lymphocyte subsets and preparation of cells for flow cytometry were performed as described [11]. CD4+ cells with Treg phenotype were determined as CD4+ CD25high+ cells. The gate on CD4+CD25high+ was set on the very brightest cells in the same way every time by the same observer (Fig. 1). CD4+CD25high+cells were analysed in three different samples and the mean value was calculated. The number of CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25high+ cells positive for CD45RO, CD62L, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen (CTLA)-4, glucocorticoid-induced tumour necrosis factor receptor family-related gene (GITR), human leucocyte antigen D-related (HLA-DR) and CD38 was determined. The number of activated CD4+ cells was determined as CD4+CD38+HLA-DR+ cells. The following monoclonal antibodies used were isotype control γ1-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/γ1-phycoerythrin (PE)/γ1-peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP)/γ1-allophycocyanin (APC), CD4-PerCP (clone SK3), CD4-APC (clone SK3), CD25-PE (clone M-A251), CD25-FITC (clone M-A251), HLA-DR-PE (clone TU36), CD38-APC (clone HIT2), CD45RO-FITC (clone UCHL1), CD62L-APC (clone Dreg 56), CTLA-4-PE (clone BNI3) and GITR-PerCP (clone DTA-1), all purchased from Becton Dickinson (Erembodegem, Belgium). All samples were analysed by four-colour flow cytometry using a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS)Calibur (Becton Dickinson) equipped with a 488 nm argon-ion laser and a 635 nm red diode laser. Data were processed using CellQuest Pro software (Becton Dickinson). The fluorescence of 50 000 cells was measured. To obtain the absolute number of a lymphocyte population, the percentage of cells in a lymphocyte gate expressing lymphocyte markers was multiplied by the lymphocyte count. Lymphocyte counts were performed at the Department of Clinical Biochemistry at Copenhagen University Hospital, Hvidovre.

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometric panels showing the gating strategy. (a) Side scatter and CD4. The gate is set around the population of CD4+ cells used for further gating of CD4+CD25high+ cells shown in Fig. 1b. PerCP: peridinin chlorophyll. (b) CD4 and CD25. The gate is set around the population of CD4+CD25high+ cells. PE, phycoerythrin.

Enrichment of CD4+ cells

CD4+ cells were enriched from freshly collected PBMC using a magnetic activated cell separator (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), as described previously [11]. The purity of sorted populations was determined by flow cytometry and was always > 90%. Enriched CD4+ cells were used for reverse transcribed (RT)–PCR.

The FoxP3 by RT–PCR

Measurement of Foxp3 mRNA, CD4 mRNA, CD8 mRNA and CD14 mRNA in separated CD4+ cells was performed by RT–PCR (Taqman) assay. Preparation of mRNA was performed using an automated procedure (KingFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) based on magnetic beads coated with oligo-dT. The eluted mRNA was reverse transcribed using random hexamer priming and the Taqman assay was performed using intron-spanning primer probe sets. The FoxP3 signal was then expressed relative to the CD4 signal by the delta Ct method; that is, the CD4 was used as an internal reference instead of a household gene; the CD8 and CD14 were included for contamination control. All measurements were double-determined. FoxP3 mRNA was expressed as FoxP3/CD4 delta Ct values. These were converted into relative units (RU).

Statistical analysis

Data are given as medians (minimum, maximum). Descriptive analysis was performed for all efficacy measures overall and stratified by time of measurement (weeks 0, 4, 12, 24) and patient (yes, no). Correlations between efficacy measures were calculated using Spearman's correlation coefficient for patients and controls, separately. Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated using the original observations. The test (H0: no association) was performed using a t-distribution. Spearman's correlation coefficient was calculated using the rank transformation of the original observations [12]. Differences in development of the efficacy measures (percentages and absolute counts variable) for the patients across time were evaluated using a repeated-measurements analysis of variance. The correlation between measurements for the same individual was taken into account by including a correlation structure in the analysis. Due to a non-normal distribution of the efficacy measures, a rank-transformation of the efficacy measures was used. The assumptions for using an analysis of variance were evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilks test for normality and visual inspection of residual plots for evaluating equal variances. Comparison between patients and controls were made using Wilcoxon's two-sample test.

Results

CD4 counts and viral loads before and after initiation of HAART

To examine immune recovery upon starting treatment with HAART CD4 counts and HIV-RNA viral load were measured in all 26 HIV-infected patients at weeks 0, 4, 12 and 24. For comparison, measurements of CD4 counts were performed in controls. In patients CD4 counts increased upon initiation of HAART (median 208 cells/µl (23–368 cells/µl) at week 0, median 329 cells/µl (191–655 cells/µl) at week 24; P < 0·0001. Similarly, viral loads decreased (median 101 800 HIV-RNA copies/ml (472–> 1 000 000 copies/ml) at week 0, to median < 40 HIV-RNA copies/ml (< 40–87 copies/ml) at week 24; P < 0·0001. In controls median CD4 counts were significantly higher than in patients [712 cells/µl (509–1088 cells/µl)] both compared with week 0 (P < 0·0001) and week 24 (P < 0·0001) values.

The Treg determination by flow cytometry and FOXP3 mRNA levels

To determine Treg levels in HIV-infected patients upon initiation of HAART CD4+CD25high+ cells as percentages of CD4+ cells and absolute counts were measured at weeks 0, 4, 12 and 24 and in all 11 controls.

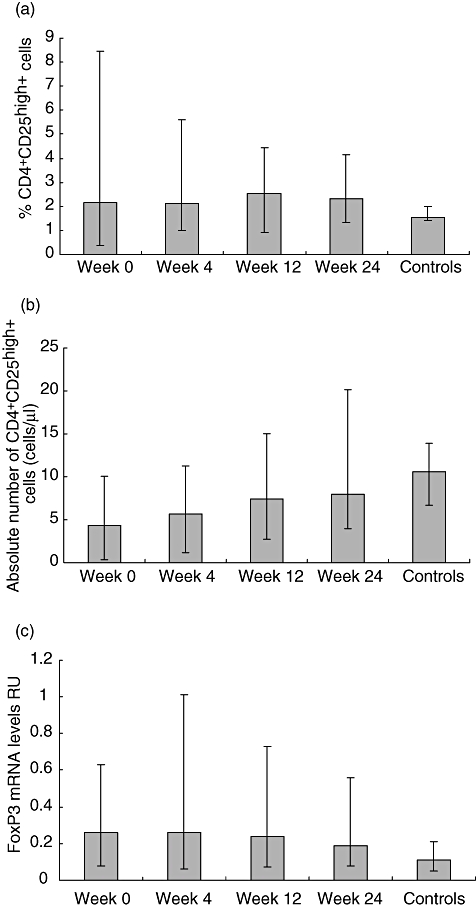

At baseline, median percentage of Tregs in HIV-infected patients was 2·2% of CD4+ cells (0·4–8·5%) and remained unchanged upon initiation of HAART [2·1% (1·0–5·6%), 2·5% (0·9–4·4%) and 2·3% (1·3–4·1%) at weeks 4, 12 and 24 respectively; P = 0·524]. In controls median Treg percentages were significantly lower than in patients [1·55% (1·4–2·0%)] compared with week 0 (P = 0·034) and week 24 (P < 0·05) values (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

All data are given as medians (range). (a) Percentages of T regulatory cells (Tregs) measured by flow cytometry as CD4+CD25high+ cells were significantly higher in the 26 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients compared with controls both when comparing week 0 (P = 0·034) and week 24 (P < 0·05) values. Percentages of CD4+CD25high+ percentages did not change during treatment with highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) (P = 0·524). (b) Absolute numbers of CD4+CD25high+ cells in the 26 HIV-infected patients increased significantly during HAART (P < 0·0001). In controls median absolute counts of CD4+CD25high+ cells were significantly higher than in patients both when comparing control values to week 0 (P < 0·05) and 24 (P < 0·05) values. (c) Levels of Tregs measured as forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) mRNA expression and expressed as relative units (RU) did not change significantly during HAART in the 26 HIV-infected patients (P = 0·2859). In controls FoxP3 mRNA levels were significantly lower than in HIV-infected patients both when comparing control values to week 0 (P < 0·0001) and week 24 (P = 0·0013) values.

Absolute counts of CD4+CD25high+ cells increased significantly during HAART [4·4 cells/µl (0·4–10·1 cells/µl), 5·7 cells/µl (1·2–11·3 cells/µl), 7·4 cells/µl (2·7–13·3 cells/µl) and 8·0 cells/µl (4·0–20·2 cells/µl) at weeks 0, 4, 12, 24 respectively; P < 0·0001]. In controls median Treg absolute counts were significantly higher than in patients [10·6 cells/µl (6·7–13·9 cells/µl)] compared with week 0 (P < 0·001) and 24 (P < 0·02) values (Fig. 2b).

The FoxP3 mRNA levels were measured in all 26 HIV-infected patients at weeks 0, 4, 12 and 24 and in 11 controls. Median FoxP3 mRNA RU did not change significantly during HAART. [At weeks 0, 4, 12 and 24 median RU values in HIV-infected patients were 0·26 (0·08–0·63), 0·26 (0·06–1·01), 0·24 (0·07–0·73) and 0·19 (0·08–0·56) respectively; P = 0·2859]. In controls median mRNA level RU was 0·11 (0·05–0·21), which was significantly lower than patients compared with week 0 (P < 0·0001) and week 24 (P = 0·0013) values (Fig. 2c).

There was no significant correlation between time of seroconversion and levels of Tregs.

Association between Treg levels and immune status

To investigate whether levels of Tregs are influenced by immunological status in HIV-infected patients, the association between Tregs and CD4 counts or viral loads was analysed. Significant correlations were not found between FoxP3 and viral loads at any time of follow-up. Furthermore, we investigated the relation between CD4 counts and Tregs by separating patients into two groups (CD4 counts </≥ 200 cells/µl at the time of initiation of HAART).

No correlation was found during follow-up between CD4 counts and percentages of CD4+CD25high+ or FoxP3 levels. No significant changes over time were found between the two groups with CD4 counts of </≥ 200 cells/µl.

Immune activation upon initiation of HAART

To determine immune activation, CD4+ cells co-expressing CD38 and HLA-DR were measured in patients at weeks 0, 4, 12, 24 and in controls. In patients, median percentages of CD4+CD38+HLA-DR+ decreased after initiation of HAART. [Week 0 median 8·4% (3·3–53·3%), week 4 9·4% (2·2–39·5%), week 12 6·3% (1·6–29·2%), week 24 4·9% (1·3–13·8%); P = 0·0003]. In controls, immune activation was lower [median 1·4% of CD4+ cells (0·8–3·8%) compared with both weeks 0 and 24 (P < 0·0001). Significant correlation between percentages of CD4+CD38+HLA-DR+ and FoxP3 levels was not found.

Surface markers of Tregs

To determine the distribution of the surface markers CD45RO, CD62L, CTLA-4, GITR, HLA-DR and CD38 as Treg markers, these markers were measured in the CD4+CD25+ and in the CD4+CD25high+ cell populations (Table 2). None of the examined surface markers showed stronger correlations to FoxP3 than CD25 alone.

Table 2.

Percentages (%) of CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25high+ cell subpopulations in patients at weeks 0 and 24 and controls.

| Surface markers | Week 0 (%) | Week 24 (%) | Controls (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+CD25+ | 26·9† | 34·2† | 42·3 |

| CD4+CD25+CD45RO+ | 31·7 | 32·7 | 35·6 |

| CD4+CD25+62L+ | 27·8 | 31·6 | 28·6 |

| CD4+CD25+CTLA-4+ | 13·2 | 17·8 | 19·5 |

| CD4+CD25+GITR+ | 5·9 | 10·8‡ | 9·6 |

| CD4+CD25CD38+ | 18·9 | 16·8‡ | 15·4 |

| CD4+CD25+HLA-DR+ | 4·6† | 2·8† | 1·2 |

| CD4+CD25high+ | 2·2† | 2·3† | 1·6 |

| CD4+CD25high+CD45RO+ | 2·2† | 2·5† | 1·5 |

| CD4+CD25high+62L+ | 2·1† | 2·1† | 1·5 |

| CD4+CD25high+CTLA-4+ | 0·7 | 1·1 | 0·5 |

| CD4+CD25high+GITR+ | 0·3 | 0·4† | 0·2 |

| CD4+CD25high+CD38+ | 1·9† | 1·2†,‡ | 0·7 |

| CD4+CD25high+HLA-DR+ | 0·9† | 0·9†,‡ | 0·3 |

All values are given as median values in percentages of CD4+ cells.

Indicates a significant difference from controls.

Indicates a significant change from week 0 to week 24. CTLA: cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen;GITR: glucocorticoid-induced tumour necrosis factor receptor family-related gene; HLA-DR: human leucocyte antigen D-related.

Discussion

The present study was designed to examine associations between immunodeficiency, immune activation and levels of Tregs in HIV-infected patient by quantifying levels of Tregs in treatment-naive HIV-infected patients prior to and during the first 24 weeks of HAART. The study showed higher percentages of CD4+CD25high+ cells paralleled by higher levels of FoxP3 in HIV-infected patients compared with healthy controls. In patients neither the percentage of CD4+CD25high+ nor the expression of FoxP3 changed significantly during 24 weeks of HAART. In contrast, CD4 counts increased and viral loads decreased. Thus, the elevated level of Tregs was found to be independent of both immunological and virological status in HIV-infected patients.

Determination of Tregs is possible both on surface marker and gene levels. Tregs identified via surface markers, primarily CD25, using flow cytometry has been used for years [4,13]. Tregs express CD25 in a higher manner (CD25high+) than activated cells [10]. Identifying CD25high+, however, is difficult and subjective. Also, it has been debated if the population of CD4+CD25high+ cells is really covering the whole population of Tregs[14]. Other surface markers such as CD45RO, CD62L, CTLA-4, GITR, HLA-DR and CD38 have been suggested as markers of Tregs. However, they all have in common that they do not represent the whole Treg population [14]. Also, the gene FoxP3 was believed previously to be expressed only by Tregs[10]. However, FoxP3 mRNA levels by RT–PCR is considered the gold standard for identification of Tregs[10,15]. In order to comply with the different methods of identifying Tregs, we chose to determine Tregs both by measuring FoxP3 levels and determining CD4+CD25high+ cells. Also, the study intended to clarify the proportion of Tregs expressing the surface markers CD45RO, CD62L, CTLA-4, GITR, HLA-DR and CD38. The presence of these surface markers on Tregs is well established [2,4,16,17], while the proportion of Tregs positive for these surface markers is controversial [4,14]. We found elevated levels of CD4+CD25high+ cells co-expressing these markers in patients compared with controls both before and after HAART. A better correlation to FoxP3 was not found by adding any of these surface markers. These findings indicate that replacing CD25 with any of these other Treg markers are likely to underestimate the level of Tregs.

The relation between Tregs and HIV is controversial. Persistent antigen exposure is believed to induce normal CD4+ cells to obtain Treg phenotype and function [18]. However, Tregs are CD4 and CCR5 positive and thereby susceptible to HIV [9]. Therefore, the absolute number of CD4+CD25high+ cells is expected to decline with HIV progression. Thus, lower absolute numbers of CD4+CD25high+ cells in HIV-infected patients compared with controls are reported in other studies [2,8], which our results support. We demonstrate significantly lower absolute numbers of CD4+CD25high+ cells before initiation of HAART as well as after 24 weeks of treatment. Absolute numbers of CD4+CD25high+ cells, however, might be less interesting than percentages of CD4+CD25high+ cells; these percentages tell us if Tregs expand during HIV-infection or have a slower decline with different kinetics than CD4+ cells in general. Our data show that Tregs measured as percentages of CD4+CD25high+ cells in treatment-naive patients are significantly higher than those in healthy controls. This suggests an expansion of Tregs as disease progresses. Higher percentages of CD4+CD25high+ cells compared with controls are also consistent with the findings of other studies [2,6–8,19,20], including a large cross-sectional study of 81 patients [2]. Our data show elevated levels of FoxP3 as well as higher percentages of CD4+CD25high+ cells in untreated patients compared with controls, which is in full agreement with a recently published study [20], thus supporting the hypothesis concerning expansion of Tregs in disease progression. Lower levels of FoxP3 mRNA have been reported only once [15].

Immune activation is meant to eliminate pathogens from the body. However, sometimes activation becomes unspecific, switching something supposedly useful into damage. This double-edged sword seems especially important concerning HIV, as immune activation has been proved to be associated with disease progression [1,21] and might be part of the causal and not well-understood relationship between CD4+ cell loss, HIV viraemia and immune activation. In this regard, Tregs are believed to play an important role; the immune activation might, as part of advanced disease, in turn cause the Treg population to expand as an attempt to slow down disease progression. Alternatively, high frequencies of Tregs are down-regulating beneficial HIV-specific responses, thereby causing progression of the infection. We found no association between immune activation and Tregs. Interestingly, our data show clearly that Tregs did not change after initiation of HAART despite a highly significant decrease in immune activation, indicating that immune activation itself may not drive the expansion of Tregs. Alternatively, we are measuring levels of Tregs too soon after initiation of HAART as CD4 counts and immune activation are only near-normalized. However, in a study of 15 patients treated with HAART for more than 5 years full normalization of immune activation and CD4 counts was found, and even in that setting Treg levels in HIV-infected patients were elevated (L. Kolte et al., submitted).

Few studies have examined the impact of HAART on the Treg population. Our study of a prospective cohort provides unique knowledge and shows clearly that HAART has no influence on the Treg level as percentages of CD4+CD25high+ cells as well as FoxP3 mRNA levels remain significantly higher in HIV-infected patients than in controls. This is in excellent agreement with a recent prospective study [20], and is questioned only by one study that reports decreased FoxP3 expression in untreated HIV-patients, with normalization after treatment with HAART [15]. A relation between the virus itself and Tregs has been suggested as one of the contributors to possible changes in Treg levels during HIV infection. However, we found no association between Tregs and HIV-RNA, which is supported by earlier findings [6,9], and questioned by only one study [20]. These findings support the lack of effect of HAART on Tregs.

In conclusion, HAART have minor effects on the Treg level measured as CD4+CD25high+ cells and FoxP3 mRNA levels. However, it brings us only slightly closer to answering the overall question as to whether or not Tregs are beneficial in HIV infection. Indeed, it highlights the need for knowledge about Treg levels in large well-defined patient populations as well as in fast and slow/non-progressors.

The present study examined associations between immunodeficiency, immune activation and levels of Tregs inHIV-infected patients by investigating the influence of HAART on Tregs in a prospective study. We found elevated Treg levels in HIV-infected patients, and initiation of HAART did not normalize or even lower the percentages of CD4+CD25high+cells or FoxP3 mRNA levels after 24 weeks of treatment, despite patients at this point having fully suppressed viral loads, increasing CD4 counts and reduced immune activation, indicating that the presence of HIV is not the only factor influencing the Treg level. Thus, treatment with HAART might not be sufficient to limit or repair the harmfull effects of HIV on the immune system.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the patients who made this study possible. We thank the University of Copenhagen for financial support. We also thank Anna-Louise Sørensen for excellent technical assistance.

References

- 1.Hazenberg MD, Otto SA, van Benthem BH, et al. Persistent immune activation in HIV-1 infection is associated with progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2003;17:1881–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggena MP, Barugahare B, Jones N, et al. Depletion of regulatory T cells in HIV infection is associated with immune activation. J Immunol. 2005;174:4407–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundgren JD, Mocroft A. The impact of antiretroviral therapy on AIDS and survival. J HIV Ther. 2006;11:36–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baecher-Allan C, Brown JA, Freeman GJ, Hafler DA. CD4+CD25high regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J Immunol. 2001;167:1245–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Read S, Mauze S, Asseman C, Bean A, Coffman R, Powrie F. CD38+ CD45RB(low) CD4+ T cells: a population of T cells with immune regulatory activities in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3435–47. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3435::AID-IMMU3435>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsunemi S, Iwasaki T, Imado T, et al. Relationship of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells to immune status in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2005;19:879–86. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000171401.23243.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epple HJ, Loddenkemper C, Kunkel D, et al. Mucosal but not peripheral FOXP3+ regulatory T cells are highly increased in untreated HIV infection and normalize after suppressive HAART. Blood. 2006;108:3072–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinter AL, Hennessey M, Bell A, et al. CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells from the peripheral blood of asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals regulate CD4(+) and CD8(+) HIV-specific T cell immune responses in vitro and are associated with favorable clinical markers of disease status. J Exp Med. 2004;200:331–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oswald-Richter K, Grill SM, Shariat N, et al. HIV infection of naturally occurring and genetically reprogrammed human regulatory T-cells. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolte L, Dreves AM, Ersboll AK, et al. Association between larger thymic size and higher thymic output in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1578–85. doi: 10.1086/340418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nolte-'t Hoen EN, Wagenaar-Hilbers JP, Boot EP, et al. Identification of a CD4+CD25+ T cell subset committed in vivo to suppress antigen-specific T cell responses without additional stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3016–27. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim AY, Price P, Beilharz MW, French MA. Cell surface markers of regulatory T cells are not associated with increased forkhead box p3 expression in blood CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected patients responding to antiretroviral therapy. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84:530–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2006.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersson J, Boasso A, Nilsson J, et al. The prevalence of regulatory T cells in lymphoid tissue is correlated with viral load in HIV-infected patients. J Immunol. 2005;174:3143–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maggi E, Cosmi L, Liotta F, Romagnani P, Romagnani S, Annunziato F. Thymic regulatory T cells. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:579–86. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baecher-Allan C, Viglietta V, Hafler DA. Human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aandahl EM, Michaelsson J, Moretto WJ, Hecht FM, Nixon DF. Human CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells control T-cell responses to human immunodeficiency virus and cytomegalovirus antigens. J Virol. 2004;78:2454–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2454-2459.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss L, Donkova-Petrini V, Caccavelli L, Balbo M, Carbonneil C, Levy Y. Human immunodeficiency virus-driven expansion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells, which suppress HIV-specific CD4 T-cell responses in HIV-infected patients. Blood. 2004;104:3249–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim A, Tan D, Price P, et al. Proportions of circulating T cells with a regulatory cell phenotype increase with HIV-associated immune activation and remain high on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007;21:1525–34. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32825eab8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sousa AE, Carneiro J, Meier-Schellersheim M, Grossman Z, Victorino RM. CD4 T cell depletion is linked directly to immune activation in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 and HIV-2 but only indirectly to the viral load. J Immunol. 2002;169:3400–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]