Abstract

Hemodynamics, specifically, fluid shear stress, modulates the focal nature of atherogenesis. Superoxide anion (O2−.) reacts with nitric oxide (.NO) at a rapid diffusion-limited rate to form peroxynitrite (O2−. +.NO → ONOO−). Immunohistostaining of human coronary arterial bifurcations or curvatures, where oscillatory shear stress (OSS) develops, revealed presence of nitrotyrosine staining, a fingerprint of peroxynitrite; whereas in straight segments, where pulsatile shear stress (PSS) occurs, nitrotyrosine was absent. We examined vascular nitrative stress in models of OSS and PSS. Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) were exposed to fluid shear stress that simulates arterial blood flow: (1) PSS at a mean shear stress (τave) of 23 dyn·cm−2 and a temporal gradient (∂τ/∂t) at 71 dyn·cm−2sec−1, and (2) OSS at τave= 0.02 dyn·cm−2 and ∂τ/∂t = ± 3.0 dyn·cm−2·s−1 at a frequency of 1 Hz. OSS significantly up-regulated NADPH oxidase (Nox4) expression accompanied with an increase in O2−. production. In contrast, PSS up-regulated eNOS expression accompanied with.NO production (total NO2− and NO3−). To demonstrate that O2−. and.NO implicate in ONOO− formation, we added low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) to the medium in which BAEC were exposed to the above flow conditions. The medium was analyzed for LDL apo B-100 nitrotyrosine by liquid chromatography, electro ionization spray, and tandem mass spectrometry (LC/ESI/MS/MS). OSS induced higher levels of 3-nitrotyrosine, di-tyrosine, and o-hydroxy-phenylalanine compared with PSS. In the presence of ONOO−, specific apo B-100 tyrosine residues underwent nitration in the α and β helices: α-1 (Tyr144), α-2 (Tyr2524), β-2 (Tyr3295), α-3 (Tyr4116), and β-2 (Tyr4211). Hence, the characteristics of shear stress in the arterial bifurcations influenced the relative production of O2−. and.NO with an implication for ONOO− formation as evidenced by LDL protein nitration.

Keywords: shear stress, superoxide anion, nitric oxide, nitrotyrosine, LDL

Introduction

The characteristics of shear stress, namely, spatial and temporal variations, influence the focal character of atherosclerosis1–3. Shear stress acting on endothelial cells at arterial bifurcations or branching points regulates both NADPH oxidase4,5 and nitric oxide synthase activities6,7. The former is considered a major source of oxygen-centered radicals (i.e., superoxide anion [O2−.]) (oxidative stress), whereas the latter is a source of nitrogen-centered radicals (i.e., nitric oxide [.NO]) (nitrative/nitrosative stress). Oxidative and nitrative stress are involved in the modification of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), which occurs at high levels in the athero-prone regions8.

At the lateral wall of arterial bifurcations, flow separation and migrating stagnation points create a distinct characteristics of oscillating shear stress (OSS: bidirectional net zero forward flow)9. In these OSS-exposed regions, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are reported to be upregulated,1,2,10 and OSS may account for production of O2−. via the membranous NADPH oxidase5,11. Furthermore, an increase in O2−. production has been implicated in the oxidative modifications of LDL that plays an important role in up-regulation of adhesion molecules and cytokines12. In contrast, pulsatile shear stress (PSS: unidirectional and positive net forward flow) preferentially develops in the medial wall of arterial bifurcations or the straight regions13. PSS down-regulates NADPH oxidase activities and expression of adhesion molecules and cytokines14, providing an athero-protective mechanism to endothelial cells2,11.

Nitrotyrosine is considered to be an emergent inflammatory marker for atherosclerosis15. Superoxide anion (O2−.) reacts with.NO at a rapid diffusion-limited rate to form a strong oxidant peroxynitrite (O2−. +.NO → ONOO−)16–18. In the presence of ONOO−, the tyrosine residue of proteins undergoes nitration, giving rise to nitrotyrosine, a fingerprint for peroxynitrite15. In the present study, we hypothesized that the specific characteristics of shear stress influence the formation of peroxynitrite due to the imbalance between O2−· and.NO production in the OSS-exposed regions of vasculatures, and that the presence of ONOO− induces LDL apo B-100 protein nitration. By immunohistostaining of the explants of human coronary arteries, we demonstrated that OSS-exposed arterial bifurcations were prevalent for nitrotyrosine formation. By a combination of dynamic flow system11,19 and liquid chromatography, electro spray ionization and tandem mass spectrometry (LC/ESI/MS/MS)20,21, we showed that OSS influenced the formation of ONOO− as represented by LDL protein nitration at the tyrosine residues in the α- and β-helices.

Methods

Endothelial Cell Culture

Confluent bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) between passages 4 and 7 were seeded on Cell-Tak cell adhesive (Becton Dickson Labware, Bedford, MA) and Vitrogen (Cohesion, Palo Alto, RC 0701) coated glass slides (5 cm2) at 3 × 106 cells per slide. BAEC were grown to confluent monolayers in high glucose (4.5 g/L) DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium) supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Irvine Scientific), and 0.05% amphotericin B (Gibco) for 48 h in 5% CO2 at 37°C[k1].

Immunohistochemistry Analyses of Human Coronary Arteries

Human coronary arteries were obtained from the explanted hearts of cardiac transplant patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy in compliance with the Institutional Review Board. Specific cross-sections of the left and right coronary arteries were analyzed: the lateral wall of arterial bifurcations where oscillatory shear stress develops and the straight segments where pulsatile shear stress occurs1,22. Monoclonal antibodies were used for NOS isoforms (Transduction Labs) and nitrotyrosine (Upstate). Immunostaining was performed with standard techniques in frozen vascular tissue using biotinylated secondary antibodies and peroxidase staining. Nitrotyrosine residues were assessed on paraffin sections after quenching of K treatment for 15 min at room temperature endogenous peroxidase with 3% H2O2, proteinase (Dakocytomation), and non-specific adsorption with 3% BSA in PBS for 15 min using a monoclonal anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (1:50 in PBS/1% BSA, overnight incubation at 4°C; Zymed, Clinisciences). Sections were then incubated with a biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:200 in PBS/1% BSA; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (1 h incubation at room temperature with both agents; Zymed, Clinisciences). DAB were used as a chromogen and the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for visualization of intima, media, smooth muscle cells, and adventia. Furthermore, endothelial and smooth muscle cells were stained with monoclonal antibodies specific for von Willebrand Factor (1:25 dilution) and β-actin (1:4000 dilution) (Darkocytomation, Carpintreria, CA). Negative controls were performed by omitting the primary antibody. Positive controls included brain and kidney tissues. Immunoreactivity to nitrotyrosine and endothelial NOS (eNOS) were compared between the left main bifurcation and right coronary arteries. A semi-quantitative analysis was performed to determine the percentage of vascular cells staining positive for eNOS and nitrotyrosine.

Flow Experiments to Analyze LDL Protein Nitration

Venous blood was obtained from fasting adult human volunteers under institutional review board approval from the Atherosclerosis Research Unit at the University of Southern California. Plasma was pooled and immediately separated by centrifugation at 1500g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The technique used for separating LDL (δ=1.019 to 1.063 g/mL) was similar to that described previously23,24.

A dynamic flow system was used to deliver temporal variations in shear stress (∂τ/∂t); namely, pulsatile (PSS) and oscillatory (OSS) shear stress25,26,27. Confluent BAEC were subjected to the flow conditions in the absence and presence of LDL at 50 μg/mL: (1) Control, using cells grown under static conditions (τave= 0 dyn·cm−2 at ∂τ/∂t = 0), (2) PSS at a mean shear stress (τave) of 23 dyn·cm−2 with a temporal variation (∂τ/∂t) at 71 dyn·cm· −2·s−1, and (3) OSS at τave= 0.02 with ∂τ/∂t at ± 3 dyn·cm−2·s−1. After 4 hours, BAEC were collected for quantitative RT-PCR and Western blots. In the absence of LDL, the culture medium was collected to identify the differential production of O2−. and NO2−/NO3− in response to PSS and OSS, respectively. In the presence of LDL, the culture medium was used to determine apo-B 100 post-translational modifications.

Measurement of Extracellular Superoxide Anion (O2−·) Formation

The production of O2−· from BAEC monolayers exposed to the flow conditions as described above was measured as the superoxide dismutase (SOD)-sensitive reduction of cytochrome c18,20. In each case, the medium contained 100 μM acetylated-ferricytochrome c (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo)28. Control samples were maintained in a cell culture dish with media containing cytochrome c (100 μM) and incubated at 37°C. Aliquots of culture medium (300 μL) were collected at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h, and ferrocytochrome c absorbance was measured at 550 nm (ε550=2.1 × 104 M−1cm−1)29. For the OSS and PSS conditions, aliquots of medium bathing the BAEC in the flow apparatus were aspirated into a media solution containing acetylated-ferricytochrome c (1mM) and absorbance measured at 550 nm at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h,. The specificity of reduction by O2−· was established by comparing reduction rates in the presence and absence of SOD at 60 μg/ml30. The corrected rates for SOD-inhibited cytochrome c reduction were plotted after computing O2−· formation.

Analysis of Nitrite (NO2−) and Nitrate (NO3−)

Quantitative measurements of NO2− and NO3− were performed as an index of global nitric oxide (.NO) production following methods described previously 31,32. .NO is metabolized or decomposed via various reactions to the metabolites as NO2− and NO3−, which serve as useful measures of overall.NO production and metabolism33. Briefly, the analytical procedure was based on acidic reduction of NO2− and NO3− to.NO by vanadium (III) and purging of.NO with helium into a stream of ozone and detected by an Antek 7020 chemiluminescence.NO detector (Antek Instruments, Houston, TX). At room temperature, vanadium (III) only reduced NO2−, whereas NO3− and other redox forms of.NO (such as S-nitrosothiols) were reduced only if the solution was heated to 90–100°C, so that both NO2− and total.NO could be measured. This allowed for determination of the relative levels of NO2− and NO3−, which might be indicative of differential oxidative metabolic routes of.NO. Quantification was performed by comparing with standard solutions of NO2− and NO3−.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to study whether one of the NADPH oxidase homologues, Nox4, and eNOS were implicated in the relative production of O2−. and.NO, respectively. After BAEC were exposed to the flow conditions, total RNA was isolated using RNeasy kit (Qiagen). qRT-PCR was performed according to the recommendations of PE Biosystems TaqMan PCR Core Reagent Kit 34. Equal amounts of RNA at 0.5 μg/μL were reverse-transcribed with rTth DNA Polymerase to bring the mixed solution to a final concentration of 1X TaqMan buffer, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dATP/dCTP/dGTP, 0.4 mM dUTP, 0.1 mM probe, 0.4 μM primers, 0.01 U/μL AmpErase, and 0.025 U/μL rTth DNA polymerase. Total cDNA at 0.4 ng/μl in 5 μl was then transferred to the 96-well plate, followed by RT, beginning with manual ramp rate at 50°C for 2 min, 60°C for 30 min, and then 95°C for 5 min. Next, PCR was performed for 50 cycles at 94°C for 20 s and annealing from 58 to 65°C for 1 min (MJ Research Opticon® System). CT is the threshold cycle number at which the initial amplification becomes detectable by fluorescence. ΔRn normalizes fluorescence. TaqMan probes were used for added specificity and sensitivity35. Each sample was tested in duplicate. Each experiment was performed 5 times. The difference in CT values for various flow conditions vs. control were used to mathematically determine the relative difference in the level of NADPH oxides homologue, Nox4, and eNOS mRNA expression 35. For quantification of relative gene expression, the target sequence was normalized to the expressed housekeeping gene GAPDH or β-actin.

Western Blotting Analyses

Western blots were performed to determine if one of the NADPH oxidase homologues, Nox4, was implicated in O2−. and NO production, respectively. BAEC lysate was size-separated in 10% SDS BioRad polyacrylamide electrophoresis gel (BioRad) and electro-transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in TBS-T and probed with mouse Nox4 antibody (generously provided by Dr. J. David Lambeth Emory University School of Medicine, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C and then probed with secondary antibody, goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP conjugated (BioRad). Chemiluminescence detection was used to visualize bands of interest (SuperSignal™, Pierce) followed by exposure to autoradiography film (Hyperfilm™ MP, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Loading and transfer of equal amounts of protein in each lane were verified by reprobing the membrane with a monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody from mouse ascites fluid (1:3000 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich). Photographic films were scanned by an imaging densitometer and quantified using the NIH Image software program.

Analyses of LDL Protein Nitration by LC/ESI/MS/MS

After shear stress exposure, LDL suspended in medium was collected for LDL analysis of protein nitration. The extent of total protein-bound nitrotyrosine, o-hydroxy-phynelalanine, and di-tyrosine formation in the recovered media was determined by stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry36 on a triple quadruple mass spectrometer (API 4000, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) interfaced with a Cohesive Technologies Aria LX Series HPLC multiplexing system (Franklin, MA). Synthetic [13C6]-labeled nitrotyrosine and [13C12]-labeled di-tyrosine internal standard were added to samples for quantification of natural abundance analytes. Simultaneously, a universal labeled precursor amino acid, [13C9,15N1]tyrosine (for nitrotyrosine and di-tyrosine) or [13C9,15N1]phenylalanine (o-Phe), was added to both quantify the precursors and assess potential intra-preparative artifactual oxidation during sample handling and analysis. Proteins were hydrolyzed under argon atmosphere in methane sulfonic acid, and then samples passed over mini solid-phase C18 extraction columns (Supelclean LC-C18-SPE minicolumn; Supelco, Inc., Bellefone, PA) prior to mass spectrometry analysis. Results were normalized to the content of the appropriate precursor amino acid, which was monitored within the same injection. Intra-preparative formation of [13C9,15N]-labeled nitrotyrosine, o-hydroxy-phenylalanine, and di-tyrosine were routinely monitored and were negligible under the conditions employed (i.e. < 5% of the level of the natural abundance product observed).

Analyses of LDL apo B 100 Nitration

Samples of LDL (0.2mg/ml) treated with ONOO− (100uM) were processed for measurements of tyrosine nitration by LC/MS/MS. The tertiary structure of LDL was suspended in 10 μl 60% formic acid. Chromatographic separation was achieved using a ThermoFinnigan Surveyor MS-Pump with a BioBasic-18 100 mm C 0.18mm reverse phase capillary column. Mass analysis was performed with a ThermoFinnigan LQ Deca XP Plus ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with a nanospray ion source employing a 4.5 cm long metal needle, in the data-dependent acquisition mode. Electrical contact and voltage application to the probe tip took place via the nanoprobe assembly. Spray voltage was set to 2.9 kV and heated capillary temperature at 190°C. The column was equilibrated for 5 min with 95% solution A, 5% solution B (A, 0.1% formic acid in H2O; B, 0.1 % formic acid in acetonitrile) prior to sample injection. A linear gradient was initiated 5 min after sample injection ramping to 35% A, 65% B after 50 min and 20% A, 80% B after 60 min. Mass spectra were acquired in the m/z 400–800 range.

Protein identification was carried out with the MS/MS search software Mascot 1.9 (Matrix Science) with confirmatory or complementary analyses with TurboSequest as implemented in the Bioworks Browsers 3.2, build 41 (ThermoFinnigan). NCBI Sus scrofa protein sequences were used as the primary search database; searches were complemented with the NCBI non-redundant protein database.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD and compared among separate experiments. For comparisons between two groups, statistical analysis was performed using the two-sample independent-groups t-test. Comparisons of multiple mean values were made by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and statistical significance among multiple groups determined using the Tukey procedure (for pairwise comparisons of means between static-like and pulsatile flow conditions). P-values of < 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Result

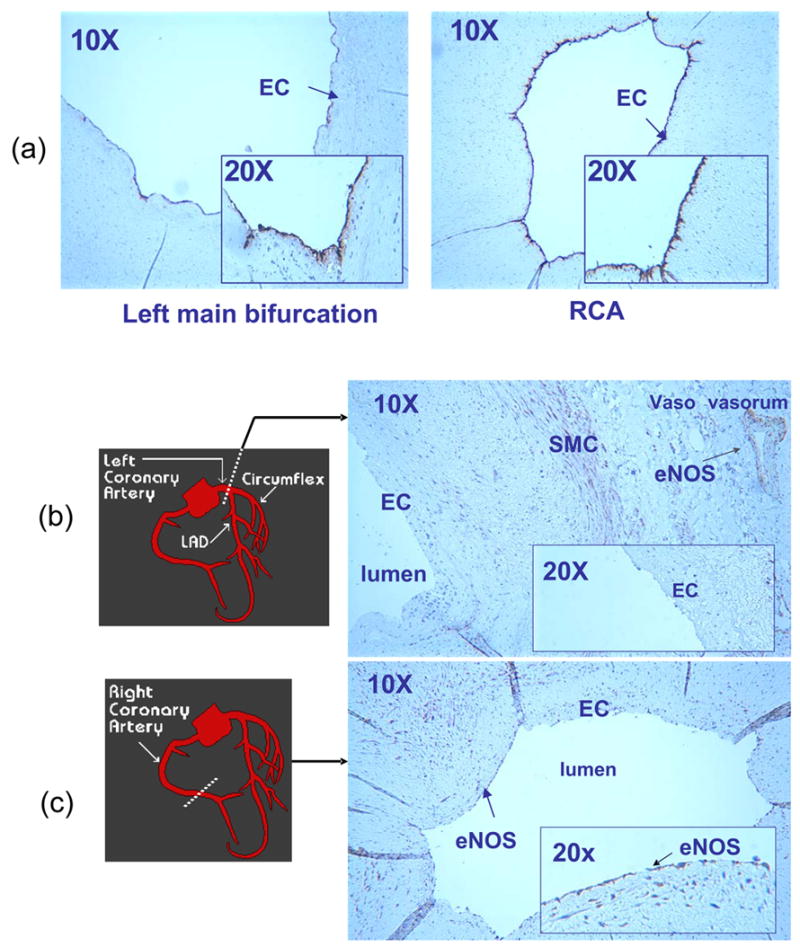

eNOS and Nitrotyrosine Immunostaining in OSS- versus PSS-Exposed Regions

Explants of human left (LCA) and right (RCA) coronary arteries were compared for eNOS and nitrotyrosine immunostaining. In the OSS-exposed regions (lateral wall of arterial bifurcations or curvatures), eNOS staining was absent in EC, whereas in the PSS-exposed regions, eNOS staining was prevalent throughout the entire EC lining the lumen (n=3) (Fig. 1a–c). Despite the absence of eNOS staining in the OSS-exposed regions, eNOS staining was present in the endothelial lining of vasa vasorum, which may be a potential source of.NO needed for ONOO− formation. In contrast, nitrotyrosine staining was present in the smooth muscle cells (SMC) in the OSS-exposed regions, including the medial wall of arterial bifurcations and curvatures, but absent in the PSS-exposed regions (n=3) (Fig. 1d–f). Counterstaining with Hemotoxylin, von Willebrand factor, and β-actin distinguished EC and SMC, respectively, in the lumen, media, and/or intima.

Fig. 1.

Immunostaining of representative sections of coronary arteries (n=3). (a) Endothelial cells (EC) were stained with von Willebrand factor in both the lateral wall of left main bifurcation (OSS-exposed region) and straight regions (PSS-exposed regions) of right coronary artery (RCA). The inserts (20X) detailed EC lining the inner lumens. En face staining of the human left main bifurcation was beyond the field of view at the lower magnification (10X). (b) A section of left main bifurcation revealed that eNOS staining was absent in the luminal EC, but was presence in both smooth muscle cells and the vasa vasorum. (c) A representative PSS-exposed section of RCA revealed that eNOS staining was prevalent throughout the entire luminal EC. (d) Smooth muscle cells (SMC) in the media of left main bifurcation was countered stained with β-actin. βactin was observed in the intima and media of the OSS-exposed section, suggesting SMC migration (data not shown). (e) OSS-exposed section of the left main bifurcation revealed nitrotyrosine staining in the media. The insert (20X) further showed nitrotyrosine staining in the SMC. (f) A representative PSS-exposed section in RCA revealed a lack of nitrotyrosine staining.

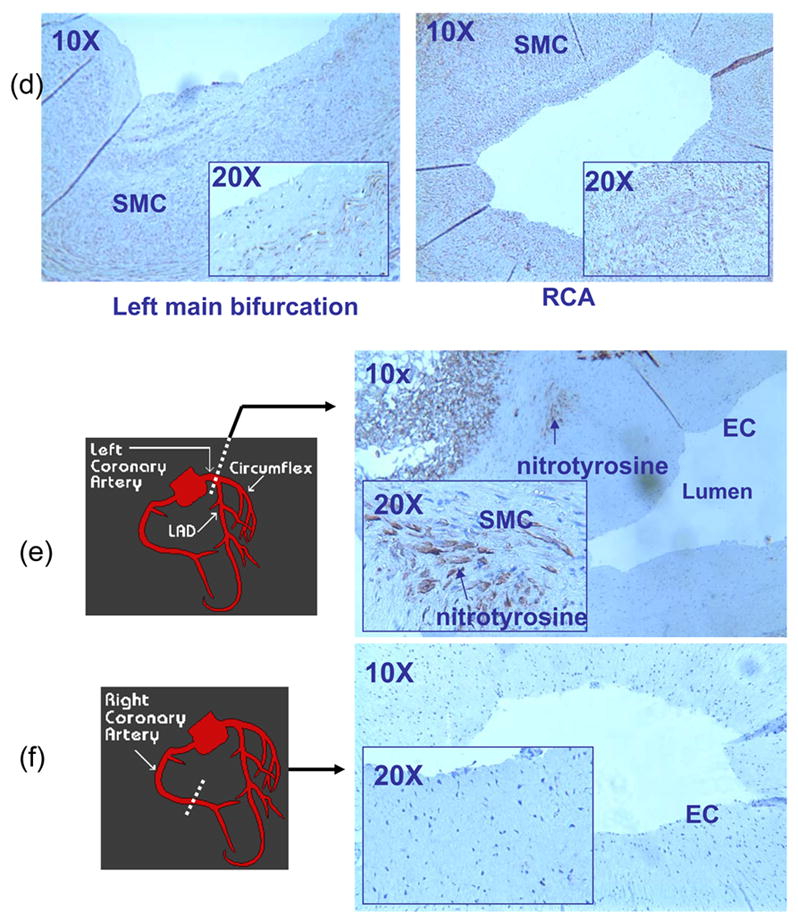

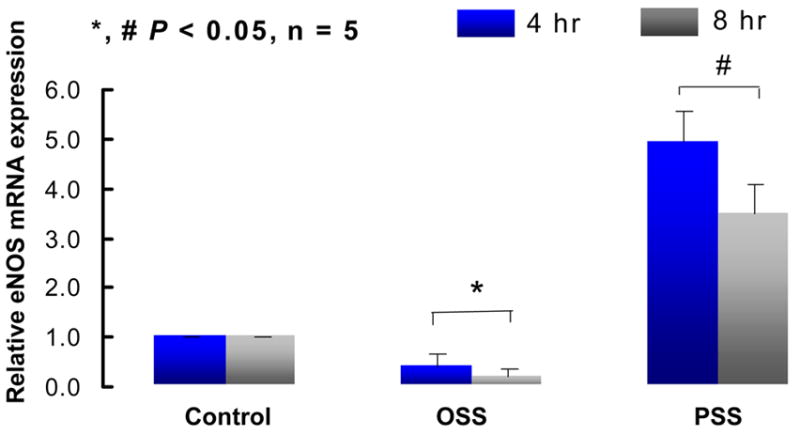

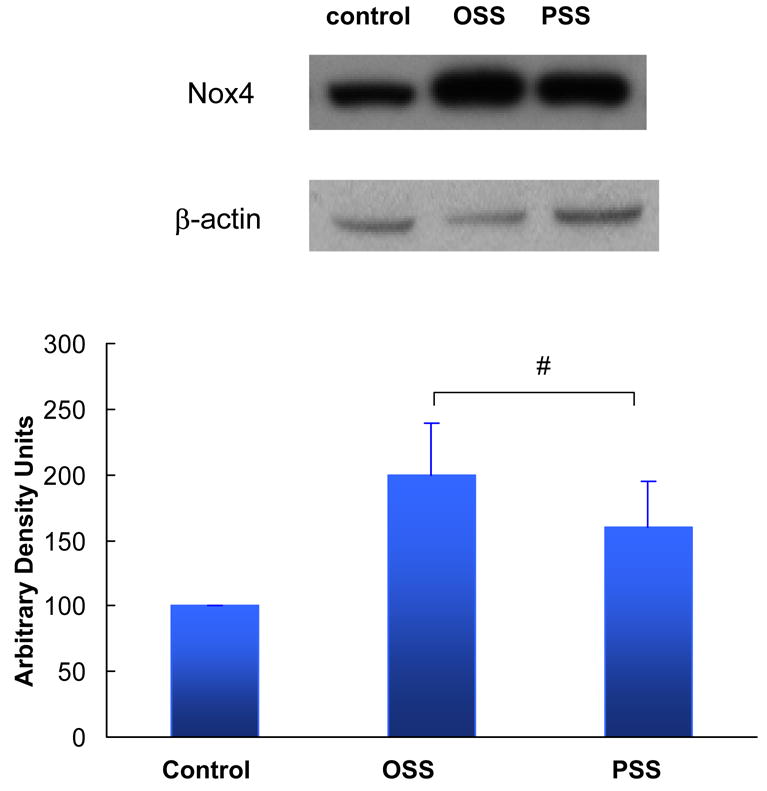

PSS and OSS Regulated the Relative Production of O2−. and.NO (NO2− and NO3−)

To demonstrate that PSS and OSS induced the relative production of O2−.and.NO, we used our dynamic flow system37. We observed that OSS was a stronger inducer than PSS in up-regulating Nox4 expression (Fig. 2a). However, PSS was a stronger inducer than OSS in up-regulating eNOS mRNA at 4 h and 8 h (Fig. 2b). Consequently, OSS induced a higher rate of O2−. production than did PSS (Table 1). OSS also induced a higher rate of.NO formation accompanied with a significantly higher ratio of O2−./.NO than did PSS (Table 1), suggesting that the imbalance in O2−. and .NO production was likely to contribute the presence of nitrotyrosine in the arterial bifurcations as demonstrated by the Immunostaining of peroxynitrite (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the elevated level of total.NO formation (NO2− and NO3−)31,32 was likely due to the presence of peroxynitrite (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2a eNOS mRNA expression in response to shear stress at 4 and 8 hours. Pulsatile shear stress (OSS) induced a sustained increase in eNOS expression by 5±0.85-fold and 4.48±0.47-fold at 4 and 8 hours, respectively, whereas oscillatory shear stress (OSS) down-regulated eNOS expression by 2.5±0.7-fold (n=5, P<0.05).

Fig. 2b Nox4 protein expression in response to shear stress. OSS up-regulated Nox4 protein by 2±0.8-fold, whereas PSS up-regulated Nox4 protein by 1.60±0.7-fold at 4 hours (n=4, P<0.05). Nox4 protein was normalized to β-actin. Controls were performed under static conditions.

Table 1.

Relative rates of O2−. and.NO production in response to PSS and OSS. The rates of O2−. and.NO production remained steady under the static state. OSS induced a higher rate of O2−. production while PSS promoted a higher rate of.NO (total NO2− and NO3−) formation. OSS also induced a higher level of.NO formation and a higher ratio of O2 −. to.NO production than did PSS.

| control | OSS | PSS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| dO2−·/dt [nmoles/min/106 cells] | 1.2±0.8* | 25.7±5.1* | 5.4 ±4.2* |

| d·NO/dt [nmoles/min/106 cells] | 1.9±0.3# | 37.5±4.1# | 48.6±5.1# |

| (dO2−·/dt)/(d·NO/dt) | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.11 |

P < 0.05, n=4)

PSS and OSS Differentially Influenced the Formation of Peroxynitrite

ONOO− reacted rather specifically with tyrosine residues in proteins to yield 3-nitrotyrosine. To measure the production of ONOO− as protein-bound nitrotyrosine, confluent BAEC were exposed to PSS and OSS in the presence of LDL at 50 μg/mL. After shear stress exposure, LDL particles suspended in medium was collected for apoB-100 protein modifications. The levels of nitration in nitrotyrosine residues of apoB-100 were higher in response to OSS than to PSS (Table 2). LC/ESI/MS/MS analyses demonstrated differential levels of protein modifications in response to PSS versus OSS: [3-nitrotyrosine] ≪ [di-tyrosine] < [o-Phe]. Together with the Immunohistochemistry analyses (Fig. 1) and the imbalanced production of O2−· and.NO (Table 1), the higher levels of apoB-100 protein nitration in response to OSS suggest that vascular nitrative stress is likely to develop within the lateral walls of arterial bifurcations and curvatures. The pathophysiologic implication of d-tyrosine and o-hydroxy-phenylalanine remains to be determined.

Table 2.

PSS and OSS influenced LDL protein nitration. Liquid chromatography/electron spray ionization/mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC/ESI/MS/MS) analyses of LDL apoB-100 revealed that OSS induced higher levels of LDL nitrotyrosine, di-tyrosine, and o-hydroxy-phenylalanie (o-Phe) than did PSS. di-tyrosine and o-Phe appeared to be the predominant forms of protein nitration. The differences between control and PSS were statistically insignificant.

| Control | OSS | PSS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-nitrotyrosine [mmol/mol] | 0.15±0.08 | 0.17±0.09* | 0.09±0.04* |

| di-tyrosinez [mmol/mol] | 16.0±4.4 | 21.1±3.4# | 13.0±2.7# |

| o-hydroxy-phenylalanine [mmol/mol] | 54.5±4.1 | 82.0±4.4+ | 52.0±3.1+ |

P < 0.05, n=3)

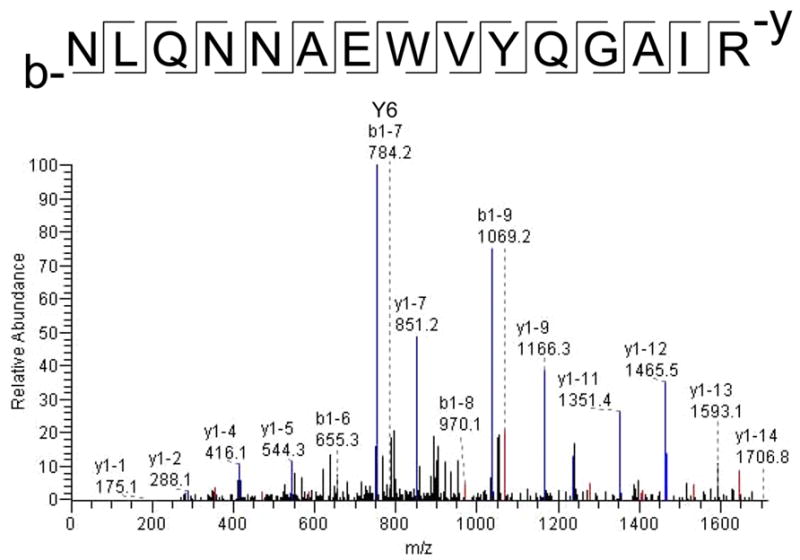

Peroxynitrite Modified Specific Protein Nitration

To further investigate the molecular mechanisms by which protein underwent nitration in the presence of ONOO−, we performed LC/MS/MS analyses of LDL (0.2mg/ml) in the presence of 100μM of ONOO− (Table 3). The tyrosine residues of LDL apoB-100 were susceptible to nitration in the α-1, α-2, α-3, and β-2 helices; specifically, α-1 (Tyr144), α-2 (Tyr2524), α-3 (Tyr4116), β-2 (Tyr3295), and β-2 (Tyr4211). Relative Mascot and Sequest scores were obtained by software that demonstrated LDL modifications. Mascot is the score obtained using matrix science software to analyze the actual observed masses, followed by searching the data base of proteins to determine the sequence of the digested protein, whereas Sequest scores are obtained using Thermo Finnigan (Excaliber) software to determine the most likely peptide from actual observed peptide masses by searching a protein database38. The representative MS/MS spectrum illustrates a tryptic peptide, NLQNNAEWVYQGAIR, which was modified with tyrosine residues 14 (Fig. 3). The Y and B ion series reflected the direction in which the mass of the ion was observed. The Y6 ion in the MS/MS spectrum showed the presence of tyrosine nitration as evidenced by an additional mass of 45 Daltons (NO2 = 46 daltons; but the replacement a hydrogen atom resulted in a mass of 45 daltons). Further evidence for an additional 45 Daltons was identified in ions Y7, Y9, Y10, Y11, Y13, B13 and B14. The mass of the modified and non-modified peptides bear a mass of one half of the theoretical for doubly charged ions and one third of the theoretical for triply charged ions. A mass difference of 22.5 daltons was observed for the nitrotyrosine containing peptide as compared to the unmodified peptide. Ion mass to charge ratio (m/z) of entire peptide demonstrated that the observed mass of the modified peptide NLQNNAEWVYQGAIR for the doubly charged ion was 911.23 Daltons, whereas the unmodified peptide mass was 888.57 Daltons, consistent with the presence of nitrotyrosine.

Table 3.

Tyrosine nitration of LDL apo B-100. Six tryptic peptides were identified to have undergone tyrosine nitration. The nitrotyrosines are denoted by asterisks. “AA” represents modified tyrosine residue, “Peptide” the numerical sequence of amino acid in the tryptic fragment, “Charge” the ion precursor charge of the tryptic fragment, “Sequence” the amino acid sequences of the tryptic fragment, “M” the Mascot score, Xcor the Sequest score, and “Δcn” the difference between two closely matched peptides.

| AA | Peptide | Charge | Sequence | M | Xcor | Δcn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y144 | 140 – 157 | 3 | QVFLY*PEKDEPTYILNIK | 42 | 3.2 | .328 |

| Y2524 | 2523 – 2534 | 2 | M*Y*QM*DIQQELQR | 71 | 4.4 | .264 |

| Y2524 | 2523 – 2534 | 2 | M*Y*QM*DIQQELQR | 79 | 4.5 | .286 |

| Y3295 | 3292 – 3311 | 3 | VPSY*TLILPSLELPVLHVPR | 78 | 5.9 | .558 |

| Y4116 | 4107 – 4121 | 2 | NLQNNAEWVY*QGAIR | 97 | 4.7 | .478 |

| Y4211 | 4202 – 4213 | 3 | FQFPGKPGIY*TR | 34 | 2.5 | .271 |

Fig. 3.

A representative MS/MS spectrum of nitro-modified peptide. The tryptic peptide, NLQNNAEWVYQGAIR, revealed that Y6 ion is the largest blue peak. The molecular weight of Y6 is greater in the modified peptide (752.4 Daltons) than the non-modified (707.3 Daltons) by 45 Daltons. Only representative peaks were labeled in the spectrum.

Discussion

This study examined whether or not spatial specific characteristics of shear stress in the arterial bifurcations or straight segments influenced vascular ONOO− formation with an implication for protein nitration at the tyrosine residues. Immunostaining of the human coronary arteries from ischemic cardiomyopathy patients revealed nitrotyrosine staining present in the OSS-exposed arterial regions (bifurcations or curvatures), but absent in the PSS-exposed regions (straight segments). In contrast, eNOS staining was absent in the OSS-exposed regions, but prevalent in the PSS-exposed regions. Next, we showed that OSS promoted an imbalance between O2−. and.NO formation that influenced formation of ONOO− as measured by the presence of 3-nitrotyrosine, d-tyrosine, and o-hydroxy-phenylalanine in the LDL apoB-100 protein. Finally, our LC/ESI/MS/MS analyses revealed specific tyrosine residue nitration in the α- and β-helices of the apoB-100 protein at α-1 (Tyr144), α-2 (Tyr2524), β-2 (Tyr3295), α-3 (Tyr4116), and β-2 (Tyr4211).

Within the lateral walls of arterial bifurcations or curvatures, disturbed flow (including OSS) is considered to be an inducer of oxidative stress that favors the production of ROS through the endothelial NADPH oxidase system5,39,40. In contrast, in the medial wall of bifurcations or straight regions where pulsatile flow develops, vascular endothelial cells are protected from atherosclerosis.14 Temporal variations in shear stress (OSS and PSS) in these regions are likely to account for the relative expression of NADPH oxidase homologues, Nox4, and eNOS. The increased vascular activities of NAD(P)H oxidases enhance the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including O2−· and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). O2−. can inactivate.NO, leading to the formation of OONO−, thereby lowering.NO bioavailability41,42. While others have shown the presence of eNOS staining in the mouse vasculatures43,44, we revealed that eNOS staining was absent in the OSS-exposed regions of coronary arteries in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy.

While eNOS expression is absent in the luminal endothelial cells of athero-prone regions of coronary arteries, eNOS expression is present in the luminal endothelial cells lining the vasa vasorum (Fig. 1b). Our observation is consistent with the previous report that reduced NO release in atherosclerotic segments was accompanied by marked reduction of immunoreactive eNOS in luminal endothelial cells. However, endothelial cells of vasa vasorum and the endothelium of normal arteries remained positive for eNOS45. In the absence of disease, the vasa vasorum nurture the outer component of the vessel wall, and the intima is fed by oxygen diffusion from the lumen. As disease progresses, the intima thickens, and oxygen diffusion is impaired. As a result, vasa become the major source for nutrients to the vessel wall46,47. Furthermore, apolipoprotein E (apoE)( −/−)/low-density lipoprotein (LDL)( −/−) double knockout mice developed vasa vasorum in association with advanced lesion formation 48. Vasa vasorum plays a significant role in maintaining vessel integrity and the vasa vasorum may contribute to the initiation and progression of different types of vascular disease in the systemic circulation. In this context, NO production form vasa vasorum likely attributes to the formation of peroxynitrite despite the absence of eNOS expression in the luminal endothelium of the coronary arteries.

Smooth muscle cells (SMC) were stained with β-actin in the left main bifurcation and right coronary artery (RCA) (Fig. 1d). We observed that nitrotyrosine staining is prevalent in the oscillatory shear stress-exposed regions, but it was relatively sparse or absent in figure 1f. This observation is likely due to the relative straight segments of RCA from which immunostaining for nitrotyrosine was performed. The luminal endothelial cells in the straight segment were known to be exposed to pulsatile flow49, which down-regulated NADPH oxidase (NOX4) expression, but up-regulated eNOS expression (Fig. 2). Despite the presence of eNOS staining in SMC, the relative rate of superoxide anion and NO production is small in response to pulsatile shear stress (Table 1). In this context, pulsatile shear stress-exposed regions seemed to be protected from oxidative stress, whereas oscillatory shear stress-exposed regions (the bifurcations or curvatures) seemed to be prone to oxidative stress as shown by the peroxynitrite formation (Fig. 1e).

Less eNOS is present in oscillatory shear stress (OSS) (Fig. 2a), but.NO production is comparable to pulsatile shear stress (PSS) in table 1. The Griess reaction is the most frequently used analytical approach to quantify the major metabolites of NO., i.e. nitrite (NO2− decay product) and nitrate (.NO3− decay product). NO2− is the measurement of total usable nitric oxide: NO + HO. → HONO → NO2− + H+, whereas total NO3− is the degradation product of peroxynitrite (ONOOH → NO3−) or the degradation product of nitrating intermediates: ONOOH → NO2. + HO. → HONO2 → NO3−.

However, the Griess reaction is specific for nitrite. Analysis of nitrate by this reaction requires chemical or enzymatic reduction of nitrate to nitrite prior to the diazotization reaction. Because there are numerous interferences in the analysis of nitrite and nitrate in biological fluids and because there is a desire to analyze these anions simultaneously, the Griess reaction has been repeatedly modified and automated. In recent years, the Griess reaction has been coupled to HPLC for post-column derivatization of chromatographically separated nitrite and nitrate. However, there are particular analytical and pre-analytical factors and problems that may affect the quantitative analysis of nitrite and nitrate in these matrices by assays.

We performed the analytical procedure based on acidic reduction of NO2− and NO3− to.NO by vanadium (III) and purging of.NO with helium into a stream of ozone and detected by an Antek 7020 chemiluminescence.NO detector. At room temperature, vanadium (III) only reduced NO2−, whereas NO3− and other redox forms of.NO (such as S-nitrosothiols) were reduced only if the solution was heated to 90–100°C, so that both NO2− and total NOx could be measured. Peroxynitrite has a half-life of about 7 day50, and it will decay to nitrite. However, our experimental samples were frozen, and then processed for NO2− and heating to 90–100 °C for NO3−. Thus, the presence of peroxynitrite might partly contribute to the elevated total NO production in response to OSS.

Previously, our lab and others have reported that the production of O2−. influences the capacity of endothelial monolayers to modulate oxidative modification of LDL apo B-10011,51, and a significant correlation may be observed between generation of O2−. and the expression of NADPH oxidase subunit, p22phox, or oxidized LDL from directional coronary atherectomy specimens52. In this study, we revealed that peroxynitrite reacted specifically with tyrosine residues in proteins leading to the formation of nitrotyrosine. Peroxynitrite is a potent oxidant, exerting it toxic effects by undergoing redox cycling, by interfering with signal transduction, or by becoming incorporated into the microtubules to distort the cytoskeleton53. Emerging evidence has shown that the exposure of LDL to ONOO− resulted in the (a) nitration of apoB-100 tyrosine residues 54, (b) peroxidation of lipid55,56, (c) depletion of lipid-soluble antioxidants57,58, and (d) conversion of the lipoprotein into a high uptake form for macrophages5,59. Thus, nitrotyrosine is considered an emerging inflammatory marker15.

The pathways leading to the nitration of tyrosine residues in proteins have been extensively studied in vitro and in vivo36,60–71. Tyrosine nitration, a post-translational modification of proteins meta position of tyrosine residues60, has been through the addition of a nitro (NO2) group in the detected under physiological settings and in a number of pathological states including inflammatory and septic conditions64,68–72. At the protein levels, these modifications implicate a number of potential consequences such as alterations in secondary structure, function, and susceptibility to proteolysis64,68–72 as well as the behavior of LDL particles73. At the physiologic level, C57 mice undergoing exercise protocol, that was associated with an augmentation in shear stress, decreased the level of protein nitration (3-nitrotyrosine level)74. In this context, protein-bound nitrotyrosine is considered to be an emergent predictor for cardiovascular disease risk assessments15,59,75–78.

The α-2 and α-3 helices of apoB-100 have the highest content of tyrosine residues (4.8% and 6.8% tyrosine, respectively). An aromatic amino acid tyrosine assumes a flat and stackable structure to intercalate into the hydrophobic space between adjacent negatively charged phospholipids of the α helices that are stabilized by lysine and arginine positive charges79. The most observed nitration of apoB-100 occurs in the α helical domains which likely account for the unfolding of LDL. This LDL unfolding has been demonstrated in various LDL modifications, including PLA2 treated LDL80 (LDL- subfraction) and in vivo LDL- 81. ApoB-100 was also sensitive to nitration/oxidation in the β-2 domain which is upstream from the LDL-Receptor site (3359–3369)79. Furthermore, nitration of tyrosine residues is likely to change the hydrophilic properties of the apoB-100 particle; rendering hydrophilic and likely disrupting hydrophobic interactions with the outer hydrophobic lipid core. Further investigation of posttranslational protein modification by nitration, including signaling molecules, enzymes, and receptors would provide insights into the biologic effects of nitrative stress in the initiation of atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for Jason P. Eiserich of the University of California at Davis for performing the analysis of nitrite (NO2−) and nitrate (NO3−). The authors appreciate the bovine Nox4 antibody generously provided by J. David Lambeth of Emory University School of Medicine, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. These studies were supported by AHA GIA 0655051Y (TKH.), NIH HL068689 (TKH), NIH HL50350 (TKH), NIH HL083015 (TKH), American Health Assistance Foundation H2003-028 (TKH), NIH HL076491 (SLH), HL70621 (SLH), and HL077692 (SLH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Ku DN. Blood Flow in Arteries. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 1997;29:399–434. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passerini AG, Polacek DC, Shi C, Francesco NM, Manduchi E, Grant GR, Pritchard WF, Powell S, Chang GY, Stoeckert CJPFD., Jr Coexisting proinflammatory and antioxidative endothelial transcription profiles in a disturbed flow region of the adult porcine aorta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2482–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305938101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai G, Kaazempur-Mofrad MR, Natarajan S, Zhang Y, Vaughn S, Blackman BR, Kamm RD, Garcia-Cardena GGM., Jr Distinct endothelial phenotypes evoked by arterial waveforms derived from atherosclerosis-susceptible and -resistant regions of human vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14871–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406073101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziegler T, Bouzourene K, Harrison VJ, Brunner HR, Hayoz D. Influence of oscillatory and unidirectional flow environments on the expression of endothelin and nitric oxide synthase in cultured endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:686–92. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.5.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Keulenaer GW, Chappell DC, Ishizaka N, Nerem RM, Alexander RW, Griendling KK. Oscillatory and steady laminar shear stress differentially affect human endothelial redox state: role of a superoxide-producing NADH oxidase. Circ Res. 1998;82:1094–101. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.10.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topper JN, Cai J, Falb DGM., Jr Identification of vascular endothelial genes differentially responsive to fluid mechanical stimuli: cyclooxygenase-2, manganese superoxide dismutase, and endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase are selectively up-regulated by steady laminar shear stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10417–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frangos JA, Huang TY, Clark CB. Steady shear and step changes in shear stimulate endothelium via independent mechanisms-superposition of transient and sustained nitric oxide production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:660–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berliner JA, Territo MC, Sevanian A, Ramin S, Kim JA, Bamshad B, Esterson M, Fogelman AM. Minimally modified low density lipoprotein stimulates monocyte endothelial interactions. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1260–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI114562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fung YC. Biomechanics:Circulation. 2. Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zarins CK, Giddens DP, Bharadvaj BK, Sottiurai VS, Mabon RF. Carotid bifurcation of plaque localization with flow velocity profiles and wall shear stress. Circulaton Research. 1983;53:502–514. doi: 10.1161/01.res.53.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang J, M I, A S, Lassegue B, Griendling KK, M N, A S, Hsiai TK. Pulsatile vs. Oscillatory Shear Stress Regulates NADPH Oxidase System: Implication for Native LDL Oxidation. Circ Res. 2003;93:1225–1232. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000104087.29395.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang J, Saha A, Boo YCPG, Sorescu J, McNally S, Holland SM, Dikalov S, Giddens DP, Griendling KK, Harrison DG, Jo H. Oscillatory Shear Stress Stimulates Endothelial Production of from p47phox-dependent NAD(P)H Oxidases, Leading to Monocyte Adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47291–47298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fung YC, Liu SQ. Elementary mechanics of the endothelium of blood vessels. J Biomech Eng. 1993;115:1–12. doi: 10.1115/1.2895465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malek AM, Alper SL, Izumo S. Hemodynamic Shear Stress and Its Role in Atherosclerosis. Journal of American Medical Association. 1999;282:2035–2042. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shishehbor MH, Aviles RJ, Brennan ML, Fu X, Goormastic M, Pearce GL, Gokce N, Keaney JF, Jr, Penn MS, Sprecher DL, Vita JA, SL H. Association of nitrotyrosine levels with cardiovascular disease and modulation by statin therapy. JAMA. 2003;289:1675–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein S, Squadrito GL, Pryor WAGC. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;21:965–74. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huie RESP. The reaction of no with superoxide. Free Radic Res Commun. 1993;18:195–9. doi: 10.3109/10715769309145868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Handy DEJL. Nitric oxide and posttranslational modification of the vascular proteome: S-nitrosation of reactive thiols. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1207–14. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000217632.98717.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsiai TK, Cho SK, Wang PK, Ing MH, Salazar A, Hama S, Navab M, Demer LL, Ho CH. Micro Sensors: Linking Vascular Inflammatory Responses with Real-Time Oscillatory Shear Stress. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:189–201. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000012739.88554.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hazen SL, Zhang R, Shen Z, Wu W, Podrez EA, MacPherson JC, Schmitt D, Mitra SN, Mukhopadhyay C, Chen Y, Cohen PA, Hoff HF, HM A-S. Formation of nitric oxide-derived oxidants by myeloperoxidase in monocytes: pathways for monocyte-mediated protein nitration and lipid peroxidation In vivo. Circ Res. 1999;85:950–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.10.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shishehbor MH, Aviles RJ, Brennan ML, Fu X, Goormastic M, Pearce GL, Gokce N, Keaney JF, Jr, Penn MS, Sprecher DL, Vita JA, Hazen SL. Association of nitrotyrosine levels with cardiovascular disease and modulation by statin therapy. Jama. 2003;289:1675–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karino T. Microscopic structure of disturbed flows in the arterial and venous systems, and its implication in the localization of vascular diseases. Int Angiol. 1986;5:297–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang J, Ing M, Salazar A, Lassegue B, Griendling K, Navab M, Sevanian A, Hsiai TK. Pulsatile versus oscillatory shear stress regulates NADPH oxidase subunit expression: implication for native LDL oxidation. Circ Res. 2003;93:1225–32. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000104087.29395.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodis HN, Kramsch DM, Avogaro P, Bittolo-Bon G, Cazzolato G, Hwang J, Peterson H, Sevanian A. Biochemical and cytotoxic characteristics of an in vivo circulating oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL-) J Lipid Res. 1994;35:669–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsiai T, Cho SKSH, Navab M, Demer LL, Ho CM. Endothelial Cell Dynamics under Pulsating Flow: Significance of High- vs. Low Shear Stress Slew Rates. Annals of Biomedical Engineeing. 2002;30:646–656. doi: 10.1114/1.1484222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nerem RM, Alexander RW, Chappell DC, Medford RM, Varner SE, Taylor WR. The study of the influence of flow on vascular endothelial biology. Am J Med Sci. 1998;316:169–75. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199809000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papadaki M, McItire LV. Methods in Molecular Medicine: Tissue Engineering Methods and Protocols. In: Yarmush ML, editor. Quantitative Measurement of Shear-Stress Effects on Endothelial Cells. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 1998. pp. 577–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang JRM, Hamilton RT, Lin TC, Eiserich JP, Hodis HN, Hsiai TK. 17beta-Estradiol reverses shear-stress-mediated low density lipoprotein modifications. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:568–78. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang J, Jian Wang J, Paolo Morazzoni P, Howard N, Hodis HN, Alex Sevanian A. The Phytoestrogen Equol Increases Nitric Oxide Availability by Inhibiting Superoxide Production: An Antioxidant Mechanism for Cell-Mediated LDL Modification. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2003;34:1271–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rouhanizadeh M, Hwang J, Clempus RE, Marcu L, Lassegue B, Sevanian ATKH. Oxidized-1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine induces vascular endothelial superoxide production: Implication of NADPH oxidase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:1512–22. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braman RS, Hendrix SA. Nanogram nitrite and nitrate determination in environmental and biological materials by vanadium (III) reduction with chemiluminescence detection. Anal Biochem. 1989;61:2715–2718. doi: 10.1021/ac00199a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Der Vliet A, Nguyen MN, Shigenaga MK, Eiserich JP, Marelich GPCEC. Myeloperoxidase and protein oxidation in cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:L537–L546. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.3.L537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pietraforte D, Salzano AM, Scorza GMM. Scavenging of reactive nitrogen species by oxygenated hemoglobin: globin radicals and nitrotyrosines distinguish nitrite from nitric oxide reaction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1244–55. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu Y, Heistad DD, Knudtson KL, Lamping KG, Faraci FM. Quantification of mRNA for endothelial NO synthase in mouse blood vessels by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:611–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000012663.85364.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.walker NJ. A technique whose time has come. Science. 2002;296:557–559. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5567.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brennan ML, Wu W, Fu X, Shen Z, Song W, Frost H, Vadseth C, Narine L, Lenkiewicz E, Borchers MT, Lusis AJ, Lee JJ, Lee NA, Abu-Soud HM, Ischiropoulos HSLH. A tale of two controversies: defining both the role of peroxidases in nitrotyrosine formation in vivo using eosinophil peroxidase and myeloperoxidase-deficient mice, and the nature of peroxidase-generated reactive nitrogen species. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17415–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112400200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsiai TK, Cho SK, Wong PK, Ing M, Salazar A, Sevanian A, Navab M, Demer LL, Ho CM. Monocyte recruitment to endothelial cells in response to oscillatory shear stress. Faseb J. 2003;17:1648–57. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1064com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DMJSC. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Keulenaer GW, Chappell DC, Ishizaka N, Nerem RM, Alexander RW, Griendling KK. Oscillatory and steady laminar shear stress differentially affect human endothelial redox state: role of a superoxide-producing NADH oxidase. Circ Res. 1998;82:1094–101. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.10.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chappell DC, Varner SE, Nerem RM, Medford RM, Alexander RW. Oscillatory shear stress stimulates adhesion molecule expression in cultured human endothelium. Circ Res. 1998;82:532–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNally JSDM, Giddens DP, Saha A, Hwang J, Dikalov S, Jo H, Harrison DG. Role of xanthine oxidoreductase and NAD(P)H oxidase in endothelial superoxide production in response to oscillatory shear stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2290–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00515.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sowers JR, Epstein M, Frohlich ED. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: an update. Hypertension. 2001;37:1053–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.4.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Irani K. Oxidant signaling in vascular cell growth, death, and survival: a review of the roles of reactive oxygen species in smooth muscle and endothelial cell mitogenic and apoptotic signaling. Circ Res. 2000;87(3) doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poppa V, Miyashiro JK, Corson MABCB. Endothelial NO synthase is increased in regenerating endothelium after denuding injury of the rat aorta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1312–21. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.8.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mueller CF, Laude K, McNally JS, DG H. ATVB in focus: redox mechanisms in blood vessels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:274–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000149143.04821.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oemar BS, Tschudi MR, Godoy N, Brovkovich V, Malinski TTFL. Reduced endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and production in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1998;97:2494–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.25.2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams JKDDH. Structure and function of vasa vasorum. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1996;9:53–57. doi: 10.1016/1050-1738(96)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moreno PR, Purushothaman KR, Sirol M, Levy AP, V F. Neovascularization in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2006;113:2245–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.578955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langheinrich AC, Michniewicz A, Sedding DG, Walker G, Beighley PE, Rau WS, Bohle RMELR. Correlation of vasa vasorum neovascularization and plaque progression in aortas of apolipoprotein E(−/−)/low-density lipoprotein(−/−) double knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:347–52. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000196565.38679.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ku DN, Giddens DP, Zarins CK, Glagov S. Pulsatile flow and atherosclerosis in the human carotid bifurcation. Positive correlation between plaque location and low oscillating shear stress. Arteriosclerosis. 1985;5:293–302. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.5.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uppu RM, Pryor WA. Synthesis of Peroxynitrite in a Two-Phase System Using Isoamyl Nitrite and Hydrogen Peroxide. Analytical Biochemistry. 1996;326:242–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hwang J, Saha A, Boo YC, Sorescu GP, McNally JS, Holland SM, Dikalov S, Giddens DP, Griendling KK, Harrison DG, Jo H. Oscillatory shear stress stimulates endothelial production of O2- from p47phox-dependent NAD(P)H oxidases, leading to monocyte adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47291–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azumi H, Inoue N, Ohashi Y, Terashima M, Mori T, Fujita H, Awano K, Kobayashi K, Maeda K, Hata K, Shinke T, Kobayashi S, Hirata K, Kawashima S, Itabe H, Hayashi Y, Imajoh-Ohmi S, Itoh H, M Y. Superoxide generation in directional coronary atherectomy specimens of patients with angina pectoris: important role of NAD(P)H oxidase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1838–44. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000037101.40667.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang YJ, Xu YF, Chen XQ, Wang XCJZW. Nitration and oligomerization of tau induced by peroxynitrite inhibit its microtubule-binding activity. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2421–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leeuwenburgh C, Hardy MM, Hazen SL, Wagner P, Ohishi S, Steinbrecher UPJWH. Reactive nitrogen intermediates promote low density lipoprotein oxidation in human atherosclerotic intima. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1433–1436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Radi R, Beckman JS, Bush KMBAF. Peroxynitrite-induced membrane lipid peroxidation: the cytotoxic potential of superoxide and nitric oxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;288:481–487. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shishehbor MH, Aviles RJ, Brennan ML, Fu X, Goormastic M, Pearce GL, Gokce N, Keaney JF, Jr, Penn MSS, precher DL, Vita JA, SL H. Association of nitrotyrosine levels with cardiovascular disease and modulation by statin therapy. JAMA. 2003;289:1675–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hogg N, Darley-Usmar VM, Wilson MTSM. The oxidation of -tocopherol in human low-density lipoprotein by the simultaneous generation of superoxide and nitric oxide. FEBS Lett. 1993:326. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81790-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goss SP, Hogg NBK. The effect of -tocopherol on the nitration of -tocopherol by peroxynitrite. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;363:333–340. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Podrez EA, Schmitt D, Hoff HFSLH. Myeloperoxidase-generated reactive nitrogen species convert LDL into an atherogenic form in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1547–1563. doi: 10.1172/JCI5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, Chen J, Tsai J-HM, Martin JC, Smith CD, Beckman JS. Peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration catalyzed by superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:431–437. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90431-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eiserich JP, Hristova M, Cross CE, Jones DA, Freeman BA, Halliwell B, Van der Vliet AN. Formation of nitric oxide-derived inflammatory oxidants by myeloperoxidase in neutrophils. Nature. 1997;391:393–397. doi: 10.1038/34923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goodwin DC, Gunther MR, Hsi LC, Crews BC, Eling TE, Mason RP, Marnett LJ. Nitric oxide trapping of tyrosyl radicals generated during prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase turnover. Detection of the radical derivative of tyrosine 385. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8903–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu W, Chen W, Hazen S. Eosinophil peroxidase nitrates protein tyrosyl residues: Implication for oxidative damage by nitrating intermedies in eosinophilic inflammatory disorders. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25933–25944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sampson JB, Ye Y, Rosen HJSB. Myeloperoxidase and horseradish peroxidase catalyze tyrosine nitration in proteins from nitrite and hydrogen peroxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;356:207–13. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.MacPherson J, Comhair S, Erzurum S, Klein D, Lipscomb M, Kavuru M, Samoszuk M, Hazen S. Eosinophils Are a Major Source of Nitric Oxide-Derived Oxidants in Severe Asthma: Characterization of Pathways Available to Eosinophils for Generating Reactive Nitrogen Species. The Journal of Immunology. 2001;166:5763–5772. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Dalen C, Winterbourn C, Senthilmohan R, Kettle A. Nitrite as a Substrate and Inhibitor of Myeloperoxidase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11638–11644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pfeiffer S, Schmidt K, Mayer B. Dityrosine Formation Outcompetes Tyrosine Nitration at Low Steady-state Concentrations of Peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6346–6352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goldstein S, Czapski G, Johan Lind J, Merényi G. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3031–3036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reiter CD, Tang RJ, Beckman JS. Superoxide Reacts with Nitric Oxide to Nitrate Tyrosine at Physiological pH via Peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32460–32466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910433199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sawa T, Akaike T, Maeda H. Tyrosine Nitration by Peroxynitrite Formed from Nitric Oxide and Superoxide Generated by Xanthine Oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32467–32474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910169199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas DF, Espey MG, Vitek MP, Miranda KM, Wink DA. Protein nitration is mediated by heme and free metals through Fenton-type chemistry: An alternative to the NO/O reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12691–12696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202312699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Greenacre SAHI. Tyrosine nitration: localisation, quantification, consequences for protein function and signal transduction. Free Radic Res. 2001;34:541–81. doi: 10.1080/10715760100300471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ischiropoulos H. Biological tyrosine nitration: a pathophysiological function of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;356:1–11. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Young CG, Knight CA, Vickers KC, Westbrook D, Madamanchi NR, Runge MS, Ischiropoulos HSWB. Differential effects of exercise on aortic mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1683–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00136.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zheng L, Nukuna B, Brennan ML, Sun M, Goormastic M, Settle M, Schmitt D, Fu X, Thomson L, Fox PL, Ischiropoulos H, Smith JD, Kinter MSLH. Apolipoprotein A-I is a selective target for myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation and functional impairment in subjects with cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:529–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI21109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Berliner JA, Heinecke JW. The role of oxidized lipoproteins in atherogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:707–27. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Paoletti R, Gotto AMDPH., Jr Inflammation in atherosclerosis and implications for therapy. Circulation. 2004;109:III20–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131514.71167.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shimada K, Mokuno H, Matsunaga E, Miyazaki T, Sumiyoshi K, Miyauchi K, H D. Circulating oxidized low-density lipoprotein is an independent predictor for cardiac event in patients with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2004;174:343–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hevonoja T, Pentikainen MO, Hyvonen MT, Kovanen PT, M A-K. Structure of low density lipoprotein (LDL) particles: basis for understanding molecular changes in modified LDL. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:189–210. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Asatryan L, Hamilton R, Mario Isas J, Hwang J, Kayed R, Sevanian A. LDL phospholipid hydrolysis produces modified electronegative particles with an unfolded apoB-100 protein. Journal of Lipid Research. 2005;46:115–122. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400306-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parasassi T, Bittolo-Bon G, Brunelli R, Cazzolato G, Krasnowska EK, Mei G, Sevanian A, F U. Loss of apoB-100 secondary structure and conformation in hydroperoxide rich, electronegative LDL(-) Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:82–9. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]