Abstract

Human soluble calcium-activated nucleotidase (human SCAN) is a homologue of the salivary anti-coagulant apyrases injected by insects into their hosts to allow blood feeding. However, the human enzyme, unlike its insect counterparts, does not efficiently hydrolyze the platelet agonist, ADP. By site-directed mutagenesis, two mutant human SCANs were constructed and expressed in bacteria. Following refolding from inclusion bodies and purification, these enzymes were assessed for anti-coagulant and anti-thrombotic efficacy. These engineered proteins include both active site mutations and a dimer interface mutation to increase the stability and ADPase activity of the modified human nucleotidase. The ADPase activity of these mutants increased more than ten fold. The E130Y/K201M/E216M SCAN mutant efficiently inhibited platelet aggregation in vitro. In addition, the E130Y/K201M/T206K/T207E/E216M mutant inhibited jugular vein thrombosis in the murine ferric chloride-induced model of thrombosis, as assessed by laser Doppler blood flow measurements. The bed bug insect homologue of human SCAN was also expressed and purified, and used in these in vivo experiments as a benchmark to assess the therapeutic potential of the engineered human enzymes. The most active modified human enzyme was able to completely inhibit the thrombosis induced by ferric chloride at roughly double the protein dose used for the bed bug enzyme. Thus, for the first time, we show that an engineered form of this human protein is efficacious in an in vivo model of thrombosis, demonstrating that suitably modified human SCAN enzymes have therapeutic potential as anti-coagulant and anti-thrombotic therapeutic agents. This suggests their utility in future treatment strategies for thrombotic cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarctions and ischemic strokes.

Keywords: calcium-activated nucleotidase, ferric chloride-induced thrombosis, aggregometry, platelets, anti-coagulant proteins, laser Doppler blood flow

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases continue to be the leading causes of death in the developed world, with more than 450,000 patients in the United States afflicted by stroke annually [1]. The platelet is a major contributor to occlusive thrombus formation in acute coronary syndromes and stroke in humans. Since platelet activation and aggregation occurs early in the process of the thrombosis, inhibition of platelet function has become a cornerstone of therapy to prevent thrombus formation [2]. ADP has long been recognized as a potent platelet agonist and component of platelet dense granules, which not only triggers aggregation but also augments the action of other platelet agonists [3 , 4].

Mammals express a protein homologous to the nucleotidases found in the saliva of blood-sucking insects. In insects, these soluble proteins hydrolyze ADP at the site of host skin puncture, inhibiting the host's blood from clotting and allowing the insect to feed for extended times [5-7]. The homologous mammalian enzymes are termed calcium-activated nucleotidases (CANs, sometimes abbreviated as CANTs), and they exist as both intracellular membrane-bound forms in the ER and pre-Golgi membranes [8], as well as secreted, soluble forms (SCAN, [9]). Unlike the insect members of this nucleotidase family, the mammalian enzymes do not hydrolyze ADP effectively [8-10]. However, Dai et al were able to engineer the soluble human enzyme to hydrolyze ADP efficiently, by combining 5 point mutations in the active site [11], thus making the human enzyme functionally similar to the insect homologues regarding the ability to inhibit platelet aggregation. Our laboratory subsequently found that the activity of the wild-type soluble human enzyme is increased by dimerization, and that this dimerization requires calcium. Furthermore, we identified a residue in the dimerization interface, E130, which when mutated to tyrosine (i.e., E130Y mutant SCAN), results in a more stable and more active dimeric form of SCAN [12]. We have now designed and constructed a human SCAN mutant protein that combines this dimer interface mutation with 2 active site mutations (a triple mutant SCAN - E130Y/K201M/E216M, SCAN mutant A). The active site mutations (K201M and E216M) were suggested by the work of Dai et al and by analysis of the SCAN crystal structure [11, 12]. As expected, this mutant is more stable and more active than wild-type human SCAN. Also, unlike wild-type human SCAN, this E130Y/K201M/E216M mutant inhibited human platelet aggregation in a similar manner to that of the mutant SCAN reported by Dai et al [11]. We also constructed another mutant human scan that incorporated 2 additional mutations, which were suggested by multiple sequence alignment analyses of mammalian versus insect enzymes, as well as by analysis of the crystal structure near the active site (T206K and T207K mutations). The ADPase activity of the resultant mutant (E130Y/K201M/T206K/T207E/E216M, SCAN mutant B) was further augmented, as was anticipated. In addition, we expressed cDNA encoding the Cimex lectularius (bed bug) insect homologue of human SCAN, in order to compare our engineered human proteins to a natural protein that is known to function effectively as an anti-coagulant in vivo. The enzymatic activities of the two human SCAN mutants were measured and compared to the bed bug apyrase, as well as to wild-type human SCAN protein. Importantly, we also assessed the utility of these proteins in an in vivo animal model of thrombosis, in order to evaluate these enzymes as possible therapeutic agents for prevention and treatment of thrombosis. Here we report results using an engineered human nucleotidase protein in a murine model of thrombosis caused by ferric chloride, as monitored by laser Doppler measurements of jugular vein blood flow.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Balb/c mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley and housed and maintained by laboratory animal medicine services. Animals were humanely handled and experimentally manipulated according to animal protocols approved by the Institute of Laboratory Animal of Health and the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. These policies and procedures conform to the National Institutes of Health guidelines as stated in The Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Aseptic surgery proceeded under general anesthesia induced by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital.

Materials

The platelet aggregometer used to measure platelet aggregation is model 480VS from Chrono-Log corporation. This instrument is housed in the laboratory of Dr. Ralph Gruppo at the University of Cincinnati Children's Hospital. Fresh heparinized or sodium citrate treated human blood for aggregometry assays were obtained from two individual donors via the Hoxworth Blood Center associated with the University of Cincinnati. The laser Doppler instrument used to measure blood flow following ferric chloride induced thrombosis was a Laser FLO BM2 blood perfusion monitor from Vasamedics. The DNA construct encoding the Cimex lectularius (bed bug) apyrase was a kind gift from Dr. Jesus Valenzuela at the NIH. The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit used to introduce mutations in the human SCAN enzyme and the Escherichia coli competent bacteria were purchased from Stratagene. The DNA Core Facility at the University of Cincinnati produced the synthetic oligonucleotides needed for mutagenesis and sequenced all of the cDNA constructs. Plasmid purification kits and Ni-NTA agarose used to purify hexa-his tagged proteins were purchased from Qiagen Inc. NheI, NotI and EcoRI restriction endonucleases were obtained from New England Biolabs. The bacterial expression vector pET28a and the bacterial expression BL21(DE3) E. coli cells were purchased from Novagen. Glycerol and dialysis tubing were from Fisher Scientific. Pre-cast SDS-PAGE 4-15% gradient minigels were obtained from Bio-Rad laboratories. ADP, kanamycin, nucleotides, isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), glucose and DTT were from Sigma. Collagen was obtained from the Chronolog Corporation. This native collagen fibril preparation (type I) was prepared from equine tendons. Ferric chloride was purchased from ACROS.

Site-directed mutagenesis and protein purification of human SCAN

The mutants were made with the Stratagene QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit. The sense primers used to introduce the mutations were:

K201M: 5′-GGGCGGCCTGGGCATGGAGTGGACGACC-3′

E130Y: 5′-GTCCCACCTGGCGTATAAGGGGAGAGGCATG-3′

E216M: 5′-GTGAACGAGAACCCCATGTGGGTGAAGGTGGTG-3′

T206K/T207E: 5′-GAGTGGACGACCAAAGAGGGTGATGTGGTG-3′

The bases encoding the mutated amino acids are underlined. The antisense primers also required for the mutagenesis are not shown. The presence of the correct mutation and lack of unwanted mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The wild-type and mutant SCAN cDNA constructs were used to transform bacterial expression host BL21(DE3) cells, and after induction of expression with IPTG, bacterial inclusion bodies containing the SCAN proteins were prepared [10]. The inclusion body proteins were denatured and refolded, purified via their N-terminal hexa-histidine tags, thrombin-cleaved to remove the N-terminal tag, and further purified by anion exchange chromatography to yield purified proteins, as previously described [10]. The purified proteins were quantified by their absorbance at 280 nm and assayed for purity by SDS-PAGE. The expression, refolding, and protein purification of Cimex lectularius (bed bug) apyrase was performed using the same methodology described above for human SCAN protein [10], except that the N-terminal hexa-his tag was not excised from bed bug protein. This is because we were unable to efficiently remove the tag via the enterokinase cleavage site located near the N-terminus of the expressed protein. Removal of the purification tag was found to be unnecessary for the experiments performed.

Nucleotidase assays

Human SCAN and bed bug apyrase proteins were diluted in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8 containing 0.1% Tween 20 detergent prior to assays, in order to prevent adsorption to sample tubes at low protein concentrations. Nucleotidase activity was determined by measuring the amount of inorganic phosphate released from nucleotide substrates at 37°C using a modification of the technique of Fiske and Subbarow [13] as previously described [14]. Nucleotide hydrolyzing units are expressed in micromoles of Pi liberated per milligram of protein per hour. Generally, assays were conducted in 20 mM MOPS, pH 7.4, containing 5 mM CaCl2 and 2.5 mM nucleotide substrate.

Platelet aggregation assay

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared from citrated or heparinized blood by centrifugation at 1000xg for 10 min. Platelet-poor plasma (PPP) was obtained from blood by centrifugation of blood at 2000xg for 20 minutes. PRP was adjusted to a platelet concentration of 3 × 105 platelets/μL with PPP. Platelet aggregation was monitored using a 480VS Chrono-log aggregometer. Typically, PRP was pre-incubated at 37°C with stirring for 3 minutes with various concentrations of mutant SCAN or saline (controls). Platelet aggregation was initiated by the addition of a final concentration of 5 or 10 μM ADP. Aggregation of platelets was continuously monitored for 10 minutes after addition of ADP. In some experiments, PRP was pre-incubated at 37°C for 3 minutes, 5 μM ADP added to initiate aggregation, aggregation allowed to proceed for 1 minute, and then engineered SCAN enzyme added, and platelet aggregation monitored continuously for an additional 9 minutes.

Induction of jugular vein thrombosis by ferric chloride

The basic method used was previously described by Kurz et al [15] and modified by Wang et al [16-18]. Mice, 6-8 weeks old, were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (70 mg/kg body weight). Approximately 100 μL of engineered human SCAN nucleotidase, bed bug apyrase, or saline (control) was injected into the tail vein (the concentrations of the different proteins injected are given in the legend of Figure 4). A skin incision was made on the neck and the jugular vein was gently isolated from the surrounding tissue with forceps. 5-10 minutes after tail vein injection, the Doppler blood flow probe was placed almost touching the surface of the exposed jugular vein, and a baseline blood flow measurement was obtained. A small piece of filter paper (1.6 mm wide) pre-saturated with a FeCl3 solution (5-10% in water) was placed on the exposed vein for 3 minutes, after which time the filter paper was removed. Blood flow measurements were made 2-3 mm upstream of the ferric chloride treated vessel area and were continued for an additional 27 minutes. Blood flow readings were taken at 0, 3, 13, 23 and 30 min from start of the ferric chloride treatment. During this procedure, the animals were continuously monitored for any signs of distress, and saline was applied topically to prevent drying of the tissue surrounding the incision area. Data from each animal analyzed was expressed as a percentage of the baseline (no thrombosis) blood flow reading for that animal obtained before the ferric chloride treatment was started.

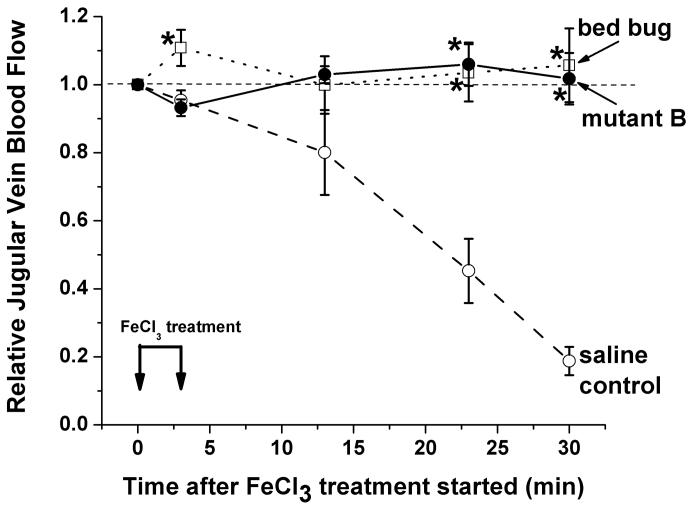

Figure 4. Engineered human SCAN and bed bug apyrase show efficacy in the ferric chloride-induced in vivo model of thrombosis.

Baseline Doppler blood flow measurements were taken for each mouse prior to starting the treatments. Then, 1.6mm wide strips of paper saturated with 10% FeCl3 were applied to the jugular veins of the mice for 3 minutes to start the experiment. Doppler blood flows (relative to each mouse's baseline blood flow = 1.0) were recorded at the indicated times and plotted (control group – 8 mice, SCAN mutant B treated group - 6 mice, bed bug treated group – 4 mice). The control animals were injected with saline while the other groups of animals were treated with either purified bed bug apyrase (6 μg/g body weight), or engineered human SCAN mutant B (13.4 μg/g body weight). The different treatments are indicated in the figure: saline controls (open circles), bed bug apyrase treated (open squares), and human SCAN mutant B (filled circles). Note the virtually identical and statistically significant protection from decreased blood flow (which is seen in the saline control animals due to thrombosis) in the bed bug and engineered human SCAN treated animals at 23 and 30 minutes.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented (Figures 1 and 2) as means ± standard deviations (SD) or means ± standard errors (Figure 4). The pairwise statistical comparisons of the data were made using a two-sided, unpaired student T-test. Results were considered statistically different if the calculated p-value was less than 0.05. Data which are statistically different from the wild-type SCAN (Figure 1) or from the saline control animals (Figure 4) are indicated by asterisks in the Figures.

Figure 1. Nucleotidase activities of the nucleotidase enzymes used in this study.

Panel A – ADPase activity of wild-type and mutant human SCAN enzymes compared to the bed bug apyrase. Wild-type SCAN (“wt”), E130Y/K201M/E216M SCAN (“mutant A”), and E130Y/K201M/T206K/T207E/E216M SCAN (“mutant B”) are compared to the bed bug insect apyrase that belongs to the same enzyme family for ADPase activity. Since ADP is the nucleotide that activates platelet, this activity is the most important for anti-coagulant and anti-thrombotic effects. Three independent assays were performed in duplicate for each measurement. Means ± standard deviations of the data are shown in the Figure. A single asterisk indicates statistically significant difference in ADPase activity between wild-type and mutant A, while a double asterisk indicates statistically significant differences between mutant B and both wild-type and mutant A SCAN activities.

Panel B – GDPase and ATPase activities of the human SCAN and bed bug enzymes. Wild-type SCAN (“wt”), E130Y/K201M/E216M SCAN (“A”), and E130Y/K201M/T206K/T207E/E216M SCAN (“B”) are shown, along with the pure bed bug apyrase activities. Three independent assays were performed in duplicate for each measurement. Means ± standard deviations of the data are shown in the Figure. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between the wild-type and mutant human SCAN activities.

Figure 2. Relative nucleotidase profile of bacterially expressed, refolded and purified bed bug apyrase.

Assays were performed at 37°C in 20 mM MOPS, 5 mM CaCl2 pH 7.4 buffer, and were initiated by addition of nucleotide to a final concentration of 2.5 mM. Three independent assays were performed in duplicate for each measurement. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations expressed as the % of the maximal bed bug apyrase nucleotidase activity measured (GDPase activity).

RESULTS

The hydrolysis rate for ADP of the E130Y/K201M/E216M (mutant A) and E130Y/K201M/T206K/T207E/E216M (mutant B) engineered SCAN enzymes increased significantly compared to wild type human SCAN (Figure 1A). The ADP hydrolysis rates for these mutants were also compared with the bed bug insect apyrase. The modified human apyrases had ADPase activities 27% and 35% of that measured for the bed bug enzyme under the same conditions, respectively (Figure 1A). Changes in other nucleotide substrates were also evident in the mutant SCAN proteins, including dramatic decreases in GDPase activity (GDP is the preferred substrate for wild-type human SCAN [10]) and substantial increases in ATPase activity of the mutated human SCANs (Figure 1B).

The bed bug apyrase was utilized in this study to allow comparison of the engineered human SCAN enzymes to a natural anti-coagulant protein in the same protein family. The ADPase activity (and therefore ability to inhibit platelet aggregation) and in vivo efficacy and potency in the murine thrombosis model of the bed bug apyrase and engineered human SCAN enzymes were compared. The bed bug apyrase enzyme was previously cloned, sequenced and expressed by Valenzuela et al [19]. This insect enzyme was shown to be dependent on Ca2+ for activity, and to hydrolyze ATP and ADP, but not AMP. However, in that study, the bed bug enzyme was expressed in mammalian COS cells, unlike the present study where it was expressed in bacteria and refolded from inclusion bodies prior to purification to homogeneity. Therefore, we report here the nucleotidase profile of the bacterially expressed, pure bed bug protein in Figure 2. As is evident from the Figure, this enzyme does not hydrolyze nucleotide monophosphates (no measurable hydrolysis of AMP and GMP), and hydrolyzes nucleoside triphosphates at roughly one-half the rate of most of the nucleoside diphosphates. This profile differs substantially from wild-type human SCAN, since although human SCAN also prefers nucleoside diphosphates in general, its relative hydrolysis of both ADP and nucleoside triphosphates is much lower [10] than that observed for the bed bug enzyme (Figure 2).

The effect of a modified human SCAN on human platelet aggregation was evaluated by aggregometry. A dose-dependent inhibition was observed using the E130Y/K201M/E216M SCAN mutant protein (mutant A), with platelet aggregation induced in citrated platelet rich plasma (PRP) by the addition of 5 μM ADP (Figure 3A). In contrast, when PRP was treated with wild-type human SCAN protein (13 μM), no inhibition of platelet aggregation was observed (data not shown). Inhibition of aggregation by E130Y/K201M/E216M human SCAN initiated by either 10μM ADP or collagen was also observed (data not shown).

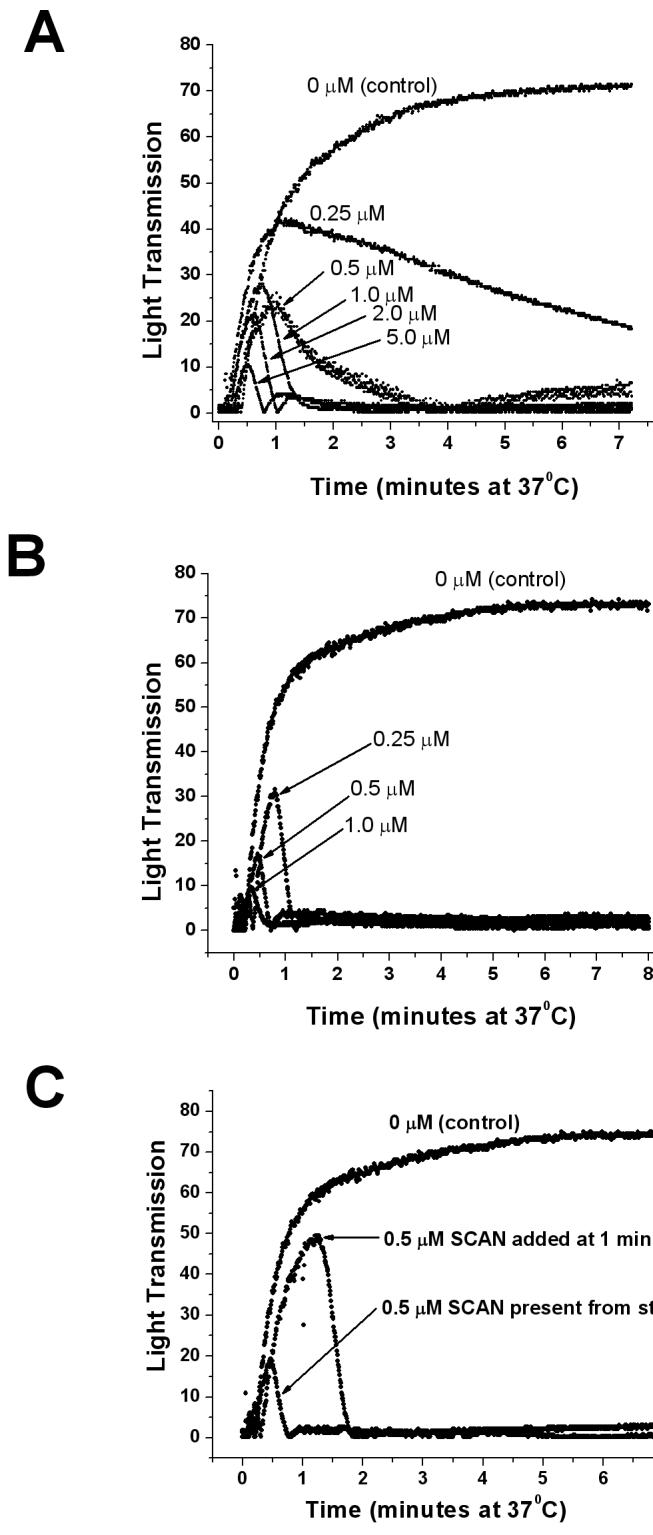

Figure 3. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by a modified SCAN.

Panel A - Aggregation of human platelets in platelet rich plasma (PRP) (300,000 platelets/μL) from citrated blood was initiated by addition of 5 μM ADP to samples containing various concentrations of E130Y/K201M/E216M SCAN (mutant A). SCAN mutant enzyme was present from the start in all traces. As platelets aggregate, more light passes through the stirred sample, increasing the light transmission.

Panel B - Aggregation of human platelets in platelet rich plasma (PRP) (300,000 platelets/μL) from heparinized blood was initiated by addition of 5 μM ADP to samples containing various concentrations of E130Y/K201M/E216M SCAN (mutant A). Note that the apparent potency of SCAN in heparinized plasma is increased relative to that seen in citrated plasma (Panel A), presumably due to a lower free concentration of Ca2+ in citrated plasma, leading to the greatly attenuated formation of the more enzymatically active dimeric form of the SCAN enzyme. Approximate IC50 values for mutant A are 0.7 μM and 0.16 μM for citrated and heparinized platelet rich plasmas, respectively.

Panel C - SCAN mutant A was added to heparinized PRP to a final concentration of 0.5 μM either from the start, or after 1 minute of platelet aggregation induced by 5 μM ADP, as indicated in the figure. Note both the inhibition of aggregation and the dis-aggregation of the initial aggregation of platelets caused by the SCAN enzyme.

Regarding the apparent potency of the mutant human SCAN enzymes in platelet aggregometry, it should be noted that the platelet rich plasma used for the experiments shown in Figure 3A was citrated, in order to chelate excess calcium and inhibit spontaneous platelet aggregation (without ADP addition). It has been estimated in the literature that the mean ionized calcium ion concentration in citrated plasma is reduced to 40-50 μM [20, 21]. In contrast, the calcium ion concentration in blood is approximately 1 mM (and is unchanged in heparinized plasma). This is relevant for these experiments, since we have previously shown that the nucleotidase activity of SCAN is absolutely dependent upon calcium, and that for maximum activity wild-type SCAN requires about 0.2 – 1.0 mM free calcium, depending upon the presence of other ions [10]. In addition, SCAN dimerization, which increases ADPase activity, requires in the range of about 100 μM calcium [12]. Thus, one would predict that in vivo the SCAN concentration needed for anti-coagulant effects might be substantially less than what is needed in these platelet aggregation assays in the presence of citrate. In fact, using mutant soluble CD39/NTPDase1 apyrase protein, Drosopoulos noted that the ability of this nucleotidase protein to inhibit platelet aggregation in citrated platelet rich plasma was attenuated relative to that seen in heparinized platelet rich plasma, and that this effect was due to limiting amounts of free calcium ion [22]. This is also true in our experiments, where the apparent potency of this SCAN mutant is decreased approximately 4-5 fold in citrated PRP relative to heparinized PRP (compare the 0.25 μM dose in Figure 3, Panel B (heparinized) with the 1.0 μM dose in Figure 3, Panel A (citrated) PRP). In addition, this human SCAN mutant was also able to dis-aggregate initial aggregation of platelets induced by 5 μM ADP in heparin treated PRP (Figure 3C).

The ferric chloride method for inducing thrombosis was utilized in this study. In preliminary experiments, we optimized several parameters, including the concentration of ferric chloride used to saturate the filter paper and the size of the ferric-chloride impregnated filter paper placed on the jugular vein to induce thrombosis. Base on these preliminary experiments, we used a 1.6 mm wide piece of filter paper saturated with 10% FeCl3 for the experiments reported in this study, as well as a laser Doppler method to measure relative blood flow in real time in the intact jugular vein.

Using a laser Doppler flow monitor probe mounted very near to, but not touching, the jugular vein, downstream from the area treated with ferric chloride, we are able to measure a reproducible and statistically significant difference in blood flow through the jugular vein in control mice versus mice pre-treated with engineered SCANs (both for SCAN mutant A and mutant B). The data for SCAN mutant A is not shown in Figure 4, since a slightly different experimental protocol was used to generate mutant A data than was used for all the rest of the in vivo data shown in Figure 4 (the size of the FeCl3 treated paper applied to the jugular vein to induce thrombosis was slightly smaller for mutant A experiments). Importantly, for mutant B (filled circles and solid line in Figure 4) the protection from reduced blood flow caused by ferric chloride-induced thrombosis is complete with this dose of engineered human SCAN enzyme. In addition, the protection from thrombosis with mutant B engineered human SCAN enzyme is indistinguishable from the protection seen with an approximately equivalent dose of bed bug apyrase nucleotidase (6 μg/g mouse body weight, calculated to give an approximately equal amount of ADPase activity injected as was used for the engineered human SCAN protein). It should be noted that no internal bleeding was noted in any of the human SCAN treated mice. This is relevant since many anti-coagulant and anti-thrombotic therapies can result in unwanted bleeding complications. Thus, the results obtained confirm that this ferric chloride-induced thrombosis model is appropriate for the evaluation of engineered human SCAN proteins, and that this particular modified human SCAN was efficacious for preventing thrombosis in vivo. In addition, it demonstrates the utility of the bed bug enzyme as a benchmark for comparison of engineered human SCAN proteins and as a positive control for evaluating the suitability of in vivo models for testing the engineered human SCAN enzymes.

DISCUSSION

Dai et al [11] and our laboratory (this work) were both able to engineer the soluble human enzyme to hydrolyze ADP efficiently by introducing multiple mutations in human SCAN. The engineered SCAN enzymes in this study differed from those published previously since they utilized a different set of active site mutations (in mutant B, only 3 of the 5 active site mutations (K201M, E216M, and T206K) were also used by Dai et al (K163M, E178M, and T168K, the residue numbers differ by 38 due to the different starting points used for the numbering schemes). We employed one active site mutation that they did not (T207E), and more importantly, also utilized a mutation in the dimerization interface that increased ADPase activity and protein stability by increasing the ability of the enzyme to dimerize (the E130Y mutation [12, 23]). In addition, no in vivo applications for the previously reported human SCAN mutants were reported by Dai et al [11], and none have been published elsewhere for any engineered mammalian SCAN enzyme. Thus, this is the first study to demonstrate that an engineered mammalian SCAN enzyme is useful as an anti-thrombotic agent in vivo.

The nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (NTPDases) constitute another family of ecto-nucleotidases that are structurally unrelated to the CAN enzymes used in the present study [24]. One of these enzymes, NTPDase1 (also known as CD39 [25-27]) is present in vascular endothelial cells and functions in maintaining hemostasis. The therapeutic utility of a soluble form of CD39/NTPDase1 apyrase has been demonstrated in a variety of cardio- and cerebrovascular disorders, including middle cerebral artery occlusion [1, 28], intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury [29], and arterial balloon injury [30, 31]. The NTPDase1 enzyme acts via the same mechanism as the SCAN enzymes used in the present study – inhibition of platelet aggregation and clotting by hydrolysis of the platelet aggregation agonist, ADP, thereby preventing activation of the platelet purinergic receptors, which normally lead to platelet activation, shape change, aggregation, and clotting. Our laboratory has experience with the bacterial expression, refolding, purification and characterization of the two naturally occurring soluble NTPDases – NTPDase5 [32] and NTPDase6 [33]. In comparison to SCAN, both of these enzymes are less efficiently refolded after bacterial expression, as well as less stable proteins that are more prone to aggregation. NTPDase5 is especially unstable and prone to aggregation [32], making it particularly unsuitable as a potential therapeutic protein. Thus, the modified human SCAN enzymes are preferable to the naturally soluble human NTPDases for development as potential injectable anti-coagulant and anti-thrombotic therapeutic agents.

The human SCAN mutants used in this study are capable of not only inhibiting platelet aggregation but are also capable of dis-aggregating the initial aggregation of platelets (see Figure 3C). Belayev et al [28] also reported that a soluble form of CD39/NTPDase1 nucleotidase utilized in a rat model of middle cerebral artery occlusion was capable of significantly reducing total infarct areas at various coronal levels when administered, both before ischemia and after 3 hours of recirculation. Thus, soluble nucleotidase enzymes appear to be very attractive candidates for therapeutic use in thrombotic pathologies.

A variety of methods have been used to evaluate anti-thrombotic treatments in animal models, including the ferric chloride induced thrombosis used in this work (murine thrombosis models are reviewed by Day et al [34]). Using ferric chloride to induce thrombosis within mesenteric blood vessels, Denis et al monitored thrombi formation by removing platelets from a donor mouse, labeling them fluorescently ex vivo, and injecting them into a recipient mouse. The animal was immobilized on the platform of a fluorescence microscope and the formation of thrombi monitored in vivo [35]. In addition, several variations of intravital microscopic methods have been applied [34], including the method of Falati et al [36], who infused coagulation-specific fluorescently labeled antibodies into mice and used confocal and widefield microscopy to study thrombosis in the cremaster muscle microcirculation. While these and other elegant and powerful systems for detecting thrombi in vivo reviewed by Day et al [34] are very useful, they require more expensive and complicated equipment, as well as more technical expertise, than the ferric chloride/Doppler blood flow system used in this work.

In summary, The ADPase activity and stability of engineered human SCAN enzyme was significantly increased by a combination of active site and dimer interface mutations. The resultant enzymes were made capable of inhibiting platelet aggregation in vitro. They are also capable of preventing thrombosis in the ferric chloride-induced model of thrombosis in mice, as assessed in vivo by laser Doppler blood flow measurements. The engineered human SCAN protein is as capable as a natural insect (bed bug) nucleotidase at preventing thrombosis, albeit slightly less potently, but presumably with less likelihood of eliciting an adverse immunogenic response in a mammal. Further optimization of the ADPase activity, dimer formation, and protein stability of the modified human SCAN enzyme should result in an even better anticoagulant and anti-thrombotic protein, which has very good potential as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of thrombotic pathologies, including myocardial infarctions and ischemic strokes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Ralph Gruppo and Dr. Davis Stroop at the University of Cincinnati Children's Hospital for use of the aggregometer and instruction on platelet aggregation assays, and the Hoxworth blood center for collection of fresh human blood. We also thank Dr. Robert Rapoport in the Department of Pharmacology and Cell Biophysics at the University of Cincinnati for use of the Vasamedics Laser Doppler apparatus used to measure blood flow. This work was supported by NIH grant HL72882 to T.L.K.

Abbreviations

- CAN

calcium-activated nucleotidase

- SCAN

soluble calcium-activated nucleotidase

- PRP

platelet rich plasma

- PPP

platelet poor plasma

- NTPDase

nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase

- MOPS

3-[N-morpholino]propanesulfonic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

There are no conflicts of interest to declare. The sole funding for this study was obtained via NIH grant HL72882 to T.L.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pinsky DJ, Broekman MJ, Peschon JJ, Stocking KL, Fujita T, Ramasamy R, Connolly ES, Jr., Huang J, Kiss S, Zhang Y, et al. Elucidation of the thromboregulatory role of CD39/ectoapyrase in the ischemic brain. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1031–1040. doi: 10.1172/JCI10649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packham MA. Role of platelets in thrombosis and hemostasis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1994;72:278–284. doi: 10.1139/y94-043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choudhri TF, Hoh BL, Zerwes HG, Prestigiacomo CJ, Kim SC, Connolly ES, Jr., Kottirsch G, Pinsky DJ. Reduced microvascular thrombosis and improved outcome in acute murine stroke by inhibiting GP IIb/IIIa receptor-mediated platelet aggregation. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1301–1310. doi: 10.1172/JCI3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang J, Kim LJ, Mealey R, Marsh HC, Jr., Zhang Y, Tenner AJ, Connolly ES, Jr., Pinsky DJ. Neuronal protection in stroke by an sLex-glycosylated complement inhibitory protein. Science. 1999;285:595–599. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5427.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valenzuela JG, Belkaid Y, Rowton E, Ribeiro JM. The salivary apyrase of the blood-sucking sand fly Phlebotomus papatasi belongs to the novel Cimex family of apyrases. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:229–237. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheeseman MT. Characterization of apyrase activity from the salivary glands of the cat flea Ctenocephalides felis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;28:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(98)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charlab R, Valenzuela JG, Rowton ED, Ribeiro JM. Toward an understanding of the biochemical and pharmacological complexity of the saliva of a hematophagous sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15155–15160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Failer BU, Braun N, Zimmermann H. Cloning, expression, and functional characterization of a Ca(2+)-dependent endoplasmic reticulum nucleoside diphosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36978–36986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith TM, Hicks-Berger CA, Kim S, Kirley TL. Cloning, Expression, and Characterization of a Soluble Calcium-Activated Nucleotidase, a Human Enzyme Belonging to a New Family of Extracellular Nucleotidases. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2002;406:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy DM, Ivanenkov VV, Kirley TL. Bacterial Expression and Characterization of a Novel, Soluble, Calcium Binding and Calcium Activated Human Nucleotidase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2412–2421. doi: 10.1021/bi026763b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai J, Liu J, Deng Y, Smith TM, Lu M. Structure and protein design of a human platelet function inhibitor. Cell. 2004;116:649–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang M, Horii K, Herr AB, Kirley TL. Calcium-dependent dimerization of human soluble calcium activated nucleotidase: Characterization of the dimer interface. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28307–28317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiske CH, Subbarow Y. The colorometric determination of phosphorous. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1925;66:375–400. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith TM, Kirley TL. Site-Directed Mutagenesis of a Human Brain Ecto-Apyrase: Evidence that the E-type ATPases are related to the Actin/ Heat Shock 70/ Sugar Kinase Superfamily. Biochemistry. 1999;38:321–328. doi: 10.1021/bi9820457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurz KD, Main BW, Sandusky GE. Rat model of arterial thrombosis induced by ferric chloride. Thromb Res. 1990;60:269–280. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90106-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Smith PL, Hsu MY, Gailani D, Schumacher WA, Ogletree ML, Seiffert DA. Effects of factor XI deficiency on ferric chloride-induced vena cava thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1982–1988. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Smith PL, Hsu MY, Ogletree ML, Schumacher WA. Murine model of ferric chloride-induced vena cava thrombosis: evidence for effect of potato carboxypeptidase inhibitor. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Smith PL, Hsu MY, Tamasi JA, Bird E, Schumacher WA. Deficiency in thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) protected mice from ferric chloride-induced vena cava thrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2007;23:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s11239-006-9009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valenzuela JG, Charlab R, Galperin MY, Ribeiro JM. Purification, cloning, and expression of an apyrase from the bed bug Cimex lectularius. A new type of nucleotide-binding enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30583–30590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips DR, Teng W, Arfsten A, Nannizzi-Alaimo L, White MM, Longhurst C, Shattil SJ, Randolph A, Jakubowski JA, Jennings LK, Scarborough RM. Effect of Ca2+ on GP IIb-IIIa interactions with integrilin: enhanced GP IIb-IIIa binding and inhibition of platelet aggregation by reductions in the concentration of ionized calcium in plasma anticoagulated with citrate. Circulation. 1997;96:1488–1494. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horisawa S, Kaneko M, Ikeda Y, Ueki Y, Sakurama T. Antithrombotic effect of SM-20302, a nonpeptide GPIIb/IIIa antagonist, in a photochemically induced thrombosis model in guinea pigs. Thromb Res. 1999;94:227–234. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(98)00215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drosopoulos J. Roles of Asp54 and Asp213 in Ca(2+) utilization by soluble human CD39/ecto-nucleotidase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;406:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00414-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang M, Kirley TL. Site-directed mutagenesis of human soluble calcium-activated nucleotidase 1 (hSCAN-1): identification of residues essential for enzyme activity and the Ca(2+)-induced conformational change. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9185–9194. doi: 10.1021/bi049565o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmermann H. Two novel families of ectonucleotidases: molecular structures, catalytic properties and a search for function. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1999;20:231–236. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang TF, Guidotti G. CD39 is an ecto-(Ca2+, Mg2+)-apyrase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9898–9901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maliszewski CR, Delespesse GJ, Schoenborn MA, Armitage RJ, Fanslow WC, Nakajima T, Baker E, Sutherland GR, Poindexter K, Birks C, et al. The CD39 lymphoid cell activation antigen. Molecular cloning and structural characterization. Journal of Immunology. 1994;153:3574–3583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kansas GS, Wood GS, Tedder TF. Expression, distribution, and biochemistry of human CD39: role in activation-associated homotypic adhesion of lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1991;146:2235–2244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belayev L, Khoutorova L, Deisher TA, Belayev A, Busto R, Zhang Y, Zhao W, Ginsberg MD. Neuroprotective effect of SolCD39, a novel platelet aggregation inhibitor, on transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Stroke. 2003;34:758–763. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000056169.45365.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guckelberger O, Sun XF, Sevigny J, Imai M, Kaczmarek E, Enjyoji K, Kruskal JB, Robson SC. Beneficial effects of CD39/ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 in murine intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:576–586. doi: 10.1160/TH03-06-0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gangadharan SP, Imai M, Rhynhart KK, Sevigny J, Robson SC, Conte MS. Targeting platelet aggregation: CD39 gene transfer augments nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase activity in injured rabbit arteries. Surgery. 2001;130:296–303. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imai M, Takigami K, Guckelberger O, Kaczmarek E, Csizmadia E, Bach FH, Robson SC. Recombinant adenoviral mediated CD39 gene transfer prolongs cardiac xenograft survival. Transplantation. 2000;70:864–870. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200009270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy-Piedmonte DM, Crawford PA, Kirley TL. Bacterial Expression, Folding, Purification and Characterization of Soluble NTPDase5 (CD39L4) Ecto-nucleotidase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2005;1747:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivanenkov VV, Murphy-Piedmonte DM, Kirley TL. Bacterial Expression, Characterization, and Disulfide Bond Determination of Soluble Human NTPDase6 (CD39L2) Nucleotidase: Implications for Structure and Function. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11726–11735. doi: 10.1021/bi035137r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Day SM, Reeve JL, Myers DD, Fay WP. Murine thrombosis models. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:486–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denis C, Methia N, Frenette PS, Rayburn H, Ullman-Cullere M, Hynes RO, Wagner DD. A mouse model of severe von Willebrand disease: defects in hemostasis and thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9524–9529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falati S, Gross P, Merrill-Skoloff G, Furie BC, Furie B. Real-time in vivo imaging of platelets, tissue factor and fibrin during arterial thrombus formation in the mouse. Nat Med. 2002;8:1175–1181. doi: 10.1038/nm782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]