Abstract

Objective

To characterize the conjoined effects of low birth weight (LBW) and childhood abuse on impaired adaptation and illness in adolescence and adulthood.

Design

Longitudinal study of a birth cohort.

Setting

Baltimore, Md.

Participants

Children (N=1748) were followed from birth to adulthood (mean age, 26 years) as part of the Johns Hopkins Collaborative Perinatal Study.

Main Exposures

Childhood abuse and LBW.

Main Outcome Measures

Indicators of adaptation were delinquency, school suspension, repeating grades, academic honors, quality of life, and socioeconomic status. Indicators of psychiatric and medical problems were depression, social dysfunction, somatization, asthma, and hypertension.

Results

Participants with both LBW and subsequent childhood abuse, relative to those with neither risk, were at a substantially elevated risk for psychological problems: 10-fold for depression; nearly 9-fold for social dysfunction, and more than 4-fold for somatization. However, they were not at an elevated risk for medical problems in adulthood. Those exposed to childhood abuse were more likely to report delinquency, school suspension, repeating grades during adolescence, and impaired well-being in adulthood, regardless of LBW status. For those with LBW alone, the prevalence of those problems was comparable with that of individuals without either risk factor.

Conclusions

Children with LBW and childhood abuse are at much greater risk for poor adaptation and psychiatric problems than those with LBW alone and those with neither risk. Preventive interventions should target families with LBW children who are at greater risk for childhood abuse.

Low Birth Weight (LBW) IS associated with increased risk of depression, suicidal ideation, and poor well-being among young adults.1–6 Similarly, childhood abuse is associated with increased risk of adult psychopathologic conditions, such as depression,7–11 substance use,8,12,13 posttraumatic stress disorder,14–18 and suicidal ideation.7,8,19–24 In both cases, researchers24–27 hypothesized that dysregulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning may serve as an underlying biological mechanism that explains the pathway between these very different risk factors. However, to date, the possible interaction between LBW and later adversity has not been examined, to our knowledge. This may be partly due to the lack of long-term information about eventual outcomes and partly because examination of such interactions requires a large sample. It is important to determine the extent to which subsequent adversity increases the likelihood of poor outcomes in children with perinatal problems because this may be a mechanism through which perinatal problems lead to poor outcomes.

To examine the possible conjoined effects of LBW and childhood abuse on adaptation and on the development of psychiatric and medical problems, we used data from the Johns Hopkins Collaborative Perinatal Study,28 a well-designed epidemiologic study that followed children from birth for more than 25 years. We compared outcomes in the transition to adulthood among 4 groups of children: (1) those with LBW and childhood abuse, (2) those with LBW alone, (3) those with childhood abuse alone, and (4) those with neither. We hypothesized that (1) the 4 groups would differ significantly regarding delinquency, school-related problems in childhood/adolescence, quality of life, well-being, and socioeconomic status in adulthood, with the group with LBW and exposed to childhood abuse exhibiting the worst outcome, and (2) there would be a synergistically increased risk of selected psychiatric and medical problems, possibly mediated by hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functionality, in children with the 2 adversities.

METHODS

The Johns Hopkins Collaborative Perinatal Study consists of data collected from pregnant women who received prenatal care and delivered their babies at Johns Hopkins Hospital between January 1, 1960, and December 31, 1964. Infants were continuously followed until 8 years of age and then were contacted again between January 1, 1992, and December 31, 1994 (mean age, 26 years), in the Pathways to Adulthood Study. The Pathways to Adulthood Study collected data from members of inner-city families for 34 years (January 1, 1960, to December 31, 1994). Of the 2694 second-generation children (G2) eligible for the Pathways to Adulthood Study,29 1756 participated in a complete interview. The study design and methods are described in details elsewhere.30

Eight G2 did not provide information on childhood abuse, leaving 1748 individuals for the present study. The 1748 respondent G2 did not differ on race, age, LBW status, or any other controlling variables from nonrespondent G2 (n=946). However, female offspring were more likely to be represented among respondents than nonrespondents (54% vs 41%; P=.001). This study was ruled exempt by the institutional review board at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in 2006 because it involved secondary data analysis of deidentified data.

ASSESSMENTS

Low Birth Weight

Birth weight was recorded by a nurse observer in the delivery room. Birth weight less than 2500 g was considered to be LBW. Gestational age was adjusted for in multivariate analyses.

Childhood Abuse

Childhood abuse history was obtained through face-to-face interviews by trained researchers masked to LBW status using the Conflict Tactics Scale,31 a 19-item (rated on a 5-point Likert scale) measure32–37 that assesses intrafamilial violence, including physical and verbal violence. The Conflict Tactics Scale has good reliability (range, 0.78–0.96, in this study Cronbach α=.82),33,34,38–40 and validity (concurrent and construct) to detect intrafamilial violence has been previously reported.32,33,38,39 The mean (SD) total score was 19.073 (12.884). Mean score plus 1 SD (31.96) was the cutoff value used to create a dichotomous abuse variable, with 1 representing high-level exposure to childhood abuse (henceforth referred to as abuse): 15.5% of participants were in this category.

Childhood/Adolescence Delinquency, School Problems, and School Excellence

Lifetime history of running away from home, dropping out of high school, and trading sex for money, drugs, or food were treated as indicators of delinquency. School suspension (lifetime, in primary education, in junior high, and in high school) and repeating grades were evaluated as indicators of school problems. Finally, lifetime history of honor rolls, scholarships, and honor society memberships were indicators of school excellence. Delinquency, school problems, and excellence data were collected retrospectively during face-to-face interviews by trained researchers masked to LBW status. Information about repeating a grade at ages 5 to 8 years and lifetime history were obtained by child psychologist interviews with mothers when children were 8 years old and via self-report in adulthood, respectively. All the questions were answered yes or no, except for number of repeated grades.

Adult Physical and Psychological Well-being and Quality of Life

The G2 were asked about their health in general, physical health, and emotional well-being via a face-to-face interview. Rating options were 1 (terrible), 2 (unhappy), 3 (mostly dissatisfied), 4 (mixed), 5 (mostly satisfied), 6 (pleased), and 7 (delighted). The G2 rated their quality of life by answering, “How is your life now?” with 10 rating options ranging from 1 (worst possible) to 10 (best possible). Sense of success was assessed using the following question: “To what degree would you say you have been successful in life?” Four rating options were given: 1 (very successful), 2 (fairly successful), 3 (slightly successful), and 4 (not successful at all).

Adult Medical Illness and Psychopathologic Features

Given the underlying assumption that LBW would be associated with biophysiologic changes associated with psychopathologic conditions (related to emotion) and medical illness (related to physiologic reactivity), we focused primarily on depression, social dysfunction, and somatization as psychiatric outcomes and on asthma and hypertension as medical outcomes. Lifetime history of medical illness was collected using the RAND Health Status Inventory,41–43 which has established good reliability44–47 and validity.47,48 Adult psychiatric status was measured using the General Health Questionnaire-28.49 Depression, social dysfunction, and somatization were each assessed by means of 7 questions, with response options ranging from 1 (better than usual) to 4 (much worse). Using the scoring method in the manual, a choice of 1 or 2 was recoded as “0” and 3 or 4 as “1.” Based on the sum of the responses, dichotomous indices for each variable were created, with a score of 4 or more indicating the presence of each variable. Internal consistency of the General Health Questionnaire, evaluated by testing split-half reliability, was 0.95.50 The General Health Questionnaire has compared favorably, with higher sensitivity (92%) and specificity (90%), with the 3 most commonly used instruments for identifying psychiatric illness (the Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) in terms of identifying psychiatric illness.51,52

Potential Confounders and Missing Values

Sociodemographic and obstetric confounders include mother’s income at the birth of the child; poverty level of the family at 7 years of age; mother’s education, marital status, age, and parity; and children’s age, sex, and race. Poverty level represents the ratio of the mother’s annualized income to the poverty level based on the Social Security Bulletin Annual Statistical Supplement53 and was calculated by the Johns Hopkins Collaborative Perinatal Study researchers.30 All the confounders, except the child’s age, were based on the mother’s self-report. Child age was calculated from birth dates.

The frequency of missing data was negligible for most confounder variables except for maternal income and education at the time of the child’s birth (2.2%). Missing data on LBW (0.4%), adult illness (all <0.2%), and functioning and attainment (all <0.1%) are negligible, except for individual and adult household income. Five percent of the children refused to provide individual income data, and 9.3% answered “I do not know,” leading to 14.3% missing data. However, missing income was not significantly associated with group membership.

DATA ANALYSIS

Logistic regression with potential confounders was used to study the association between LBW and abuse and dichotomous outcome measures such as adolescent delinquency, academic problems, and excellence. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) followed by multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used for the differences in continuous outcomes, that is, adult functioning, well-being, quality of life, and socioeconomic status among the 4 groups. After an overall test of group differences, pairwise comparisons were conducted. To avoid type I errors due to multiple testing, the level of significance was adjusted using the Holm correction.54

We also evaluated the amount of excess risk resulting from the synergy of having both LBW and abuse. Using a logistic regression model, we tested the risk of psychiatric and medical problems among the 4 groups using the group with neither form of adversity as the reference group. Potential confounders were statistically controlled for in all analyses. First, the increased risk and evidence of synergy by the 2 adversities (LBW and abuse) were examined.

Additive interaction, based on the Rothman “index of synergism,” was evaluated55–59 because it is more appropriate not to consider the effects of the 2 early adversities completely independently.55,56,60 Additive interaction exists when the risk of having 2 adversities exceeds the sum of the risk of LBW and abuse. The presence/absence of an additive interaction can be examined using an index: attributable proportion due to interaction (AP). The 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated based on the Hosmer-Lemeshow CI estimation of interaction.61 An AP exceeding 0 indicates that the increased risk is due to the joint exposure to the 2 risk factors. Thus, the 95% CI for an AP that does not include a value of 0 indicates statistical significance.

RESULTS

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

There were no significant differences among the 4 groups on demographic variables. Mean(SD) agewas 34(1.5) years, and 54% were female. Of all the participants, 81.5% were African American, 18.3% were white, and the remaining were Asian. We grouped offspring by LBW and abuse status. Approximately 70% of G2 had neither LBW nor abuse, 14% had only LBW, 13% had only abuse, and 3% had both.

CHILDHOOD/ADOLESCENCE DELINQUENCY AND ACADEMIC PROBLEMS

Table 1 provides the rates of childhood/adolescent delinquent behaviors, academic problems and excellence, overall difference, and pairwise comparisons among the 4 groups. With a few exceptions, children with both LBW and abuse exhibit the highest rates of problems, such as suspension in junior high school (63.6%), and the lowest rates of academic excellence, such as being on the honor roll (27.3%). The G2 with abuse alone (group 3) also had higher rates of problems than those with LBW alone (group 2) and those with neither (group 1). More specifically, relative to groups 1 and 2, groups 3 and 4 had higher rates for ran away from home; high school dropout; trading sex for money, food, and drugs; lifetime history of school suspension and more repeated grades; and lower rates of honor society memberships. Taken together, groups 3 and 4 generally reported many more difficulties during childhood and adolescence compared with groups 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Rates of Problems and Success in Childhood/Adolescence Among the 4 Groups of Children by LBW and Childhood Abuse Status*

| Group

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Neither (n = 1232) | 2 Only LBW (n = 246) | 3 Only Abuse (n = 226) | 4 Both LBW and Abuse (n = 44) | Unadjusted Statistics | Adjusted Statistics | Significant Pairwise Comparison† | |||

| Delinquency, No. (%) | |||||||||

| Run away from home | 153 (12.4) | 34 (13.8) | 94 (41.6) | 13 (29.5) |

|

|

1, 2 < 3, 4 | ||

| High school dropout | 220 (17.9) | 53 (21.5) | 73 (32.3) | 18 (40.9) |

|

|

1 < 3, 4 | ||

| Traded sex for money/drugs/food | 26 (2.1) | 1 (0.4) | 25 (11.1) | 3 (6.8) |

|

|

1, 2 < 3, 4 | ||

| School suspension, No. (%) | |||||||||

| Lifetime history | 610 (49.5) | 123 (50.0) | 150 (66.4) | 34 (77.3) |

|

|

1, 2 < 3, 4 | ||

| In primary education | 138 (11.2) | 31 (12.6) | 46 (20.4) | 13 (29.5) |

|

|

1, 2 < 3, 4 | ||

| In junior high school | 403 (32.7) | 82 (33.3) | 104 (46.0) | 28 (63.6) |

|

|

1, 2 <3 < 4 | ||

| In high school | 255 (20.7) | 48 (19.5) | 78 (34.5) | 13 (29.5) |

|

|

1, 2 < 4 | ||

| Repeating grades | |||||||||

| Repeated grades—lifetime, No. (%)|| | 370 (30.0) | 77 (31.3) | 99 (43.8) | 20 (45.5) |

|

¶ | 1 < 3 | ||

| Repeated grades at ages 5–8 y, No. (%)# | 79 (6.4) | 27 (11.3) | 15 (6.7) | 4 (9.3) |

|

¶ | 1 < 2 | ||

| No. of repeated grades, mean (SD) | 0.36 (0.57) | 0.41 (0.64) | 0.54 (0.68) | 0.57 (0.63) | F3,1744 = 7.3‡ | F3,1616 = 3.8§ | 1, 2 < 3, 4 | ||

| Honor and success in growing up, No. (%) | |||||||||

| Honor roll | 641 (52.0) | 118 (48.0) | 98 (43.4) | 12 (27.3) |

|

¶ | 1 > 4 | ||

| Scholarship | 196 (15.9) | 36 (14.6) | 24 (10.6) | 3 (6.8) |

|

|

|||

| Honor society | 151 (12.3) | 37 (15.0) | 11 (4.9) | 2 (4.5) |

|

¶ | 1, 2 > 3, 4 | ||

Abbreviation: LBW, low birth weight.

Unadjusted analysis was based on χ2 analysis for dichotomous outcomes and analysis of variance for continuous outcomes. Adjusted analysis was based on logistic regression for dichotomous outcomes and analysis of covariance for continuous outcomes.

Numbers denote group numbers.

P<.001.

P<.01.

Based on self-report in adulthood.

P<.05.

Collected at age 8 years from mothers by child psychologists.

P<.10.

ADULT FUNCTIONING, WELL-BEING, AND GENERAL HEALTH STATUS

Table 2 provides rates of adult functioning, well-being, and perceived health status. There were significant differences among the 4 groups in sense of success in life; quality of life; general, physical, and mental health; and emotional well-being after controlling for confounders (P<.001 for all). As in childhood and adolescence, pairwise comparisons confirmed that groups 3 and 4 had poorer adult functioning, well-being, and health in general than groups 1 and 2. Children in groups 1 and 2 did not differ in sense of success in life, quality of life, satisfaction with life, and general, physical, and mental health. The last column of the Table 2 displays the results from the MANCOVA wherein the correlations between the predictors were taken into account. Results were unchanged (P<.001 for all).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Functioning, Well-being, and General Health in Adulthood Among the 4 Groups of Children by LBW and Childhood Abuse Status*

| Group

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Adjusted F Statistic

|

|||

| Either (n = 1232) | Only LBW (n = 246) | Only Abuse (n = 226) | Both LBW and Abuse (n = 44) | ANCOVA | MANCOVA | Significant Pairwise Comparisons† | |

| Sense of success in life‡ | 2.22 (0.85) | 2.28 (0.95) | 2.56 (0.89) | 2.69 (0.98) | 11.6§ | 11.4§ | 1, 2 < 3, 4 |

| Quality of life|| | 5.43 (1.3) | 5.44 (1.2) | 4.77 (1.5) | 4.60 (1.8) | 19.0§ | 18.7§ | 1, 2 > 3, 4 |

| Emotional well-being¶ | 5.95 (1.1) | 5.88 (1.1) | 5.21 (1.5) | 5.12 (1.4) | 27.1§ | 28.6§ | 1, 2 > 3, 4 |

| General health condition¶ | 5.76 (1.1) | 5.73 (1.1) | 5.42 (1.3) | 5.10 (1.5) | 8.9§ | 9.2§ | 1, 2 > 3, 4 |

| Physical health condition¶ | 5.72 (1.2) | 5.72 (1.1) | 5.35 (1.4) | 4.97 (1.7) | 9.4§ | 10.3§ | 1, 2 < 3, 4 |

| Mental health condition# | 2.01 (1.0) | 2.00 (1.0) | 2.51 (1.1) | 2.60 (1.1) | 16.9§ | 18.1§ | 1, 2 > 3, 4 |

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; LBW, low birth weight; MANCOVA, multivariate ANCOVA.

Data are given as mean (SD) scores.

Numbers denote group numbers.

Lower scores denote higher success, ranging from very successful to not successful at all (4-point Likert scale).

P<.001.

Higher scores denote better quality of life, ranging from worst to best (10-point Likert scale).

Higher scores denote more satisfaction, ranging from terrible to delighted (7-point Likert scale)

Lower scores denote better health, ranging from excellent to poor (5-point Likert scale).

ADULT SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS

Table 3 provides significant differences in adult family incomes, individual incomes, and education in the 4 groups based on ANCOVA and multivariate ANCOVA. Offspring with neither adversity reported the highest household ($33 126) and individual ($17 119) incomes. Offspring with LBW alone and abuse alone had the next highest household and individual incomes. The pairwise comparisons confirmed that offspring with both adversities showed substantially lower family ($19 114) and individual ($9596) incomes than the other groups. Groups 3 and 4 reported significantly fewer years of education than groups 1 and 2.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Socioeconomic Status in Young Adulthood Among the 4 Groups of Children by LBW and Childhood Abuse Status*

| Group

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Adjusted F Statistic

|

|||

| Neither (n = 1232) | Only LBW (n = 246) | Only Abuse (n = 226) | Both LBW and Abuse (n = 44) | ANCOVA | MANCOVA | Significant Pairwise Comparisons† | |

| Household income, $ | 33 126 (22 173) | 29 321 (19 115) | 29 770 (27 845) | 19 114 (17 623) | 5.5‡ | 5.0§ | 1, 2, 3 > 4 |

| Individual income, $ | 17 119 (13 017) | 15 010 (12 268) | 15 993 (22 060) | 9596 (9897) | 3.3§ | 3.7§ | 1, 2, 3 > 4 |

| Education, y | 12.3 (2.1) | 12.2 (2.2) | 11.4 (2.3) | 11.2 (2.3) | 6.3‡ | 8.2‡ | 1, 2 > 3, 4 |

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; LBW, low birth weight; MANCOVA, multivariate ANCOVA.

Data are given as mean (SD).

Numbers denote group numbers.

P<.001.

P<.01.

ADULT PSYCHIATRIC AND MEDICAL ILLNESS

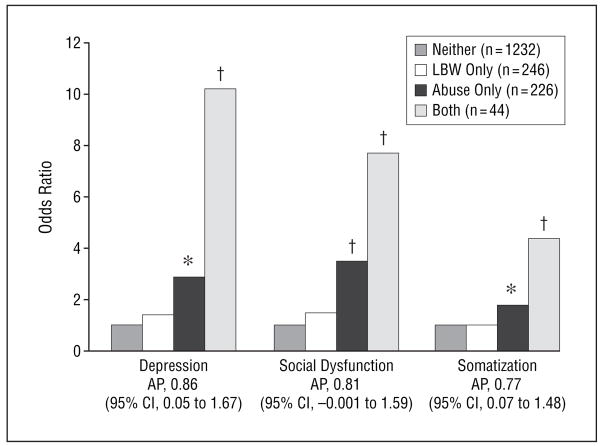

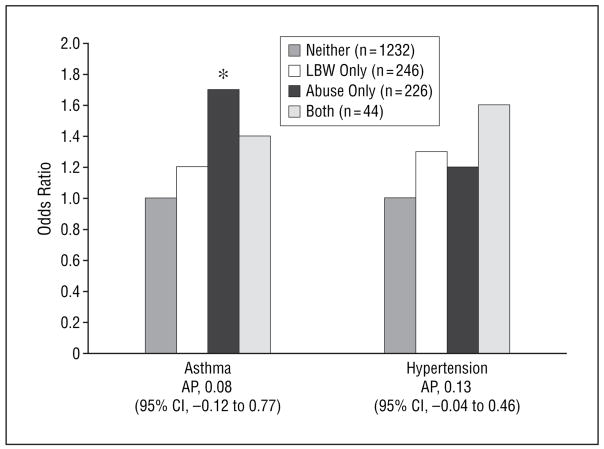

We examined the risk of depression, social dysfunction, somatization, hypertension, and asthma in adulthood among the 3 risk groups relative to the reference group, controlling for the effects of potential confounders. Figure 1 shows that relative to group 1, group 4 had nearly a 10-fold increased risk of depression (P<.001) and group 3 had an approximately 3-fold increased risk (P<.007), but group 2 was not at increased risk for depression. Similarly, relative to group 1, group 4 had a more than 7-fold increased risk of social dysfunction and a 4-fold increased risk of somatization (P<.001 for both). There was no difference in illness rates between groups 2 and 1. Group 3, relative to group 1, also showed a significant 2- to 3-fold increased risk of psychiatric problems and an almost 2-fold increased risk of asthma (P=.008).

Figure 1.

Risk of various psychiatric problems in offspring by low birth weight (LBW [defined as <2500 g]) and childhood abuse status. Analysis was based on logistic regression with adjustment for sociodemographic confounders. AP indicates attributable proportion due to additive interaction (an AP of 0 indicates no evidence of synergy); CI, confidence interval. *P<.01. †P<.001.

We formally evaluated whether there was a synergistic increased risk of adult illness associated with the 2 adversities. Clear evidence of synergy was found for psychiatric (Figure 1) but not medical (Figure 2) problems. The 95% CI for AP confirmed a significant synergistic increase in risk of depression and somatization among offspring with both adversities. The AP for social dysfunction was 0.81, suggestive evidence for synergy that did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Risk of asthma and hypertension in offspring by low birth weight (LBW [defined as <2500 g]) and childhood abuse. Analysis was based on logistic regression with adjustment for sociodemographic confounders. AP indicates attributable proportion due to additive interaction (an AP of 0 indicates no evidence of synergy); CI, confidence interval. *P=.008.

COMMENT

There are 3 main findings. First, the conjoined effects of LBW and abuse significantly increased the risk of poorer adjustment as documented in higher rates of delinquency, problems with school functioning, poorer physical health, lower quality of life, and lower socioeconomic status in adulthood. Second, offspring who experienced abuse alone also demonstrated poorer adaptation and quality of life. In contrast, offspring with LBW alone demonstrated comparable outcomes as the reference group. Third, there was a synergistically increased risk of psychiatric problems for offspring with both LBW and abuse, but there was no synergy for medical illness.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the conjoined effects of LBW and child abuse on problems during adolescence and adulthood. The community-based sample comprised a full range of birth weights, in contrast to previous studies that examined clinical samples of very LBW (<1500 g) or extremely LBW (<1000 g). This study is also the first to document a synergistic increase in the risk of psychiatric problems among adults with both LBW and abuse.

The 1970s was a period of much improved neonatal intensive care, and survivors from that time are now reaching adulthood. Research has begun to elucidate what the long-term adverse effects of LBW are on social, educational, psychiatric, and medical problems. Although such studies have great public health significance, their findings are still inconclusive. For example, although Hack et al62 and Ericson and Kallen63 found that compared with normal-birth-weight children, fewer very LBW children graduated from high school and were in postgraduate degree programs, a recent study by Saigal et al64 found no differences in educational attainment between the extremely LBW and control subjects. Hack and Klein65 suggested that differences in “contextual factors” might explain the discrepancy between their findings and those of Saigal et al, arguing that the respective cohorts may have differed in the amount of subsequent adversity experienced. The cohort of Hack et al62 consisted largely of poor urban African American individuals, with 41% of their mothers being unmarried. In contrast, the cohort of Saigal et al was predominantly white, with approximately 80% middle class and with 80% living in 2-parent households.

The present data suggest that children born with LBW did as well as their counterparts as long as they did not face serious adversity, such as child abuse. However, when faced with both adversities, these children had substantially poorer outcomes than children facing either adversity alone. Although these results focused on child abuse, further research should examine the conjoined effects of other environmental adversities.

These findings also need to be considered in the context of the severity of perinatal problems. The sample was drawn from a general community where the prevalence of very (1.5%) and extremely (1.2%) LBW was low. Compared with the cohorts of Hack et al62 and Saigal et al,64 the present LBW children may have milder forms of biological vulnerability. For example, only 1.3% of the sample had neurologic abnormality reported by pediatric neurologists at age 1 year. We reanalyzed all of the models to assess the possible impact of such abnormalities on the findings. Results were unchanged by adding this variable. However, the use of a community sample is advantageous. First, we demonstrated that LBW children, if exposed to child abuse, would experience psychiatric problems beyond what one single risk would do in adulthood. Second, it affords greater generalizability of the results.

It is of potentially great public health importance to find significant synergy on all psychiatric problems in adults with LBW and abuse. For example, relative to children with neither adversity, those with both had a more than 10-fold increased risk of depression, whereas those with LBW had no significant increased risk. Those with abuse alone had a 2-fold increased risk compared with the reference group.

This pattern of synergy was not found with asthma or hypertension. Thus, the results suggest that the synergistic increased risk of LBW and abuse among adult offspring may be relatively specific to psychiatric problems. The reason for this possible specificity is not known. Elucidation of possible pathways needs to be informed by future studies.

The present findings have potential policy implications. They suggest that LBW infants should receive continued public health surveillance and that their caretakers should receive targeted support to mitigate the effects of subsequent environmental adversities on child adaptation and productivity. For example, it may be possible to develop and implement selective prevention interventions aimed at ameliorating stress in the families of children with LBW and encouraging effective parenting as a means of preventing childhood abuse by providing services to their caregiving parents. Extreme adversity, such as abuse, does not occur in isolation from a parent’s own psychopathologic features, the rearing disciplines the parent received,35 current hardship with their spouse, or financial difficulties.21 Weissman and her group66 elegantly demonstrated that mental health services to mothers not only improved mothers’ depression status but also drastically improved their offspring’s externalizing and internalizing problems. Perhaps monitoring mothers’ well-being, offering preventive mental health services to mothers with LBW children, and monitoring LBW children to provide early intervention together could protect such children from subsequent child abuse. This study provides hope and a warning to all those working to create a better future for children with LBW.

Acknowledgments

We thank Janet Hardy and Sam Shapiro, principal investigators of the original study, Pathway to Adulthood: A Three-Generation Urban Study, 1960-1994, for allowing us to use their data; the mothers and their children who participated in the study; the helpful comments of Charles Davey, BA, Avi Reichenberg, PhD, Jacob Ham, PhD, Carl Hochhauser, PhD, and Jeffrey H. Newcorn, MD, on an earlier version of the manuscript; and Scott Miller, PhD, and Karen Feit, BA, for their assistance with statistical analysis.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants R03 MH067761 (Dr Nomura) and 5R24MH063910 (Dr Chemtob) from the National Institute of Mental Health; a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (Dr Nomura); and the Erna Reich Fund of the UJA Federation of New York.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Author Contributions: Dr Nomura has full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Nomura and Chemtob. Analysis and interpretation of data: Nomura. Drafting of the manuscript: Nomura and Chemtob. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Nomura and Chemtob. Statistical analysis: Nomura. Obtained funding: Nomura and Chemtob. Administrative, technical, and material support: Chemtob. Study supervision: Nomura and Chemtob.

References

- 1.Gray RF, Indurkhya A, McCormick MC. Prevalence, stability, and predictors of clinically significant behavior problems in low birth weight children at 3, 5, and 8 years of age. Pediatrics. 2004;114:736–743. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1150-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung YB, Ma S, Machin D, Karlberg J. Birthweight and psychological distress in adult twins: a longitudinal study. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:965–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb02697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Indredavik MS, Vik T, Heyerdahl S, Kulseng S, Fayers P, Brubakk AM. Psychiatric symptoms and disorders in adolescents with low birth weight. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F445–F450. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.038943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gale CR, Martyn CN. Birth weight and later risk of depression in a national birth cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:28–33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiles NJ, Peters TJ, Leon DA, Lewis G. Birth weight and psychological distress at age 45–51 years. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:21–28. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson C, Syddall H, Rodin I, Osmond C, Barker DJ. Birth weight and the risk of depressive disorder in later life. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:450–455. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oquendo M, Brent DA, Birmaher B, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder comorbid with major depression: factors mediating the association with suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:560–566. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, et al. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1878–1883. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vythilingam M, Heim C, Newport J, et al. Childhood trauma associated with smaller hippocampal volume in women with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:2072–2080. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodsky BS, Oquendo M, Ellis SP, Haas GL, Malone KM, Mann JJ. The relationship of childhood abuse to impulsivity and suicidal behavior in adults with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1871–1877. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gladstone GL, Parker GB, Mitchell PB, Malhi GS, Wilhelm K, Austin MP. Implications of childhood trauma for depressed women: an analysis of pathways from childhood sexual abuse to deliberate self-harm and revictimization. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1417–1425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osler M, Nordentoft M, Andersen AM. Childhood social environment and risk of drug and alcohol abuse in a cohort of Danish man born in 1953. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:654–661. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the Adverse Childhood Experience Study. Pediatrics. 2003;11:564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harkness KL, Monroe SM. Childhood adversity and the endogenous versus non-endogenous distinction in women with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:387–393. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford JD, Kidd P. Early childhood trauma and disorders of extreme stress as predictors of treatment outcome with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1998;11:743–761. doi: 10.1023/A:1024497400891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woods SJ, Wineman NM, Page GG, Hall RJ, Alexander TS, Campbell JC. Predicting immune status in women from PTSD and childhood and adult violence. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2005;28:306–319. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200510000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hetzel MD, McCanne TR. The roles of peritraumatic dissociation, child physical abuse, and child sexual abuse in the development of posttraumatic stress disorder and adult victimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:915–930. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sim L, Friedrich WN, Davies WH, Trentham B, Lengua L, Pithers W. The Child Behavior Checklist as an indicator of posttraumatic stress disorder and dissociation in normative, psychiatric, and sexually abused children. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:697–705. doi: 10.1002/jts.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penza KM, Heim C, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiological effects of childhood abuse: implications for the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s00737-002-0159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grilo CM, Sanislow C, Fehon DC, Martino S, McGlashan TH. Psychological and behavioral functioning in adolescent psychiatric inpatients who report histories of childhood abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:538–543. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman D, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forman EM, Berk MS, Henriques GR, Brown GK, Beck AT. History of multiple suicide attempts as a behavioral marker of severe psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:437–443. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McHolm AE, MacMillan HL, Jamieson E. The relationship between childhood physical abuse and suicidality among depressed women: results from a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:933–938. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, et al. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA. 2000;284:592–597. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: a convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newport DJ, Heim C, Bonsall R, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. Pituitary-adrenal responses to standard and low-dose examethasone suppression tests in adult survivors of child abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:10–20. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00692-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hardy JB. The Collaborative Perinatal Project: lessons and legacy. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00479-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardy JB, Astone NM, Brooks-Gunn J, Shapiro S. Like mother, like child: inter-generational patterns of age at first birth and associations with childhood and adolescent characteristics and adult outcomes in the second generation. Dev Psychol. 1998;34:1220–1232. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardy JB, Shapiro S, Mellits D, et al. Self-sufficiency at age 27 to 33 years: factors present between birth and 18 years that predict educational attainment among children born to inner-city families. Pediatrics. 1997;99:80–87. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. J Marriage Fam. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child conflict tactics scales: development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straus MA. The Conflict Tactics Scales and its critics: an evaluation and new data on validity and reliability. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical Violence in American Families: Risk Factors and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 Families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1990. pp. 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schumm WR, Martin MJ, Bollman SR, Jurich AP. Adolescent perspectives on family violence. J Soc Psychol. 1982;117:153–154. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1982.9713421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwong MJ, Bartholomew K, Henderson AJZ, Trinke SJ. The intergenerational transmission of relationship violence. J Fam Psychol. 2003;17:288–301. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Marchbank PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women: a retrospective study. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E11. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmes WC, Sammel MD. Brief communication:physical abuse of boys and possible associations with poor adult outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:581–586. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-8-200510180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yodanis CL, Hill K, Straus MA. Tabular Summary of the Methodological Characteristics of the Conflict Tactics Scales. Durham, NH: Family Research Laboratory, University of New Hampshire; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amato PR. Psychological distress and the recall of childhood family characteristics. J Marriage Fam. 1991;53:1011–1019. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cervantes RC, Duenas N, Valdez A, Kaplan C. Measuring violence risk and outcomes among Mexican American adolescent females. J Interpers Violence. 2006;21:24–41. doi: 10.1177/0886260505281602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams PF, Benson V. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 1990. Vital Health Stat 10. 1991;181:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hays RD. Rand HSI Health Status Inventory. Orlando, Fla: Psychological Corp/Harcourt Brace & Co; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hays RD. RAND-36 Health Status Inventory. San Antonio, Tex: Psychological Corp; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyle MH, Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G, Hatcher J. Reliability of the Health Utilities Index–Mark III used in the 1991 cycle 6 General Social Survey Health Questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:249–257. doi: 10.1007/BF02260864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones CA, Feeny D, Eng K. Test-retest reliability of Health Utilities Index scores: evidence from hip fracture. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:393–398. doi: 10.1017/s0266462305050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feeny D, Furlong WJ, Torrance GW, et al. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 system. Med Care. 2002;40:113–128. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thoma A, Sprague S, Veltri K, Duku E, Furlong W. Methodology and measurement properties of health-related quality of life instruments: a prospective study of patients undergoing breast reduction surgery. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;22:44–54. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feeny D. Commentary on Jack Dowie, Decision validity should determine whether a generic or condition-specific HRQOL measure is used in health care decisions. Health Econ. 2002;11:13–16. doi: 10.1002/hec.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldberg D. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, England: NFER; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldberg DP. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire: A Technique for the Identification and Assessment of Non-psychotic Psychiatric Illness. London, England: Oxford University Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clarke DM, Smith GC, Herrman H. A comparative study of screening instruments for mental disorders in general hospital patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1993;23:323–337. doi: 10.2190/J5HD-QPTQ-E47G-VJ0X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katz R, Stephen J, Shaw BF, Matthew A, Newman F, Rosenbluth M. The East York Health Needs study: prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorder in a sample of Canadian women. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:100–106. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Social Security Bulletin. Annual Statistical Supplement. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Resources; 1993. pp. 346–348. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: An Introduction. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Walker AM. Concepts of interaction. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112:467–470. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saracci R. Interaction and synergism. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112:465–466. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Darroch J. Biologic synergism and parallelism. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:661–668. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Greenland S, Rothman KJ. Modern Epidemiology. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Finney DJ. Probit Analysis. 3. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Confidence interval estimation of interaction. Epidemiology. 1992;3:452–456. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hack M, Flannery DJ, Schluchter M, Cartar L, Borawski E, Klein N. Outcomes in young adulthood for very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:149–157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ericson A, Kallen B. Very low birthweight boys at the age of 19. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;78:F171–F174. doi: 10.1136/fn.78.3.f171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saigal S, Stoskopf B, Steiner D, et al. Transition of extremely low-birth-weight infants from adolescence to young adulthood. JAMA. 2006;295:667–675. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hack M, Klein N. Young adult attainments of preterm infants. JAMA. 2006;295:695–696. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, et al. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology. JAMA. 2006;295:1389–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]