Abstract

We compared the ultrastructure and synaptic targets of terminals of cortical or retinal origin in the stratum griseum superficiale and stratum opticum of the rat superior colliculus. Following injections of biotinylated dextran amine into cortical area 17, corticotectal axons were labeled by anterograde transport. Corticotectal axons were of relatively small caliber with infrequent small varicosities. At the ultrastructural level, corticotectal terminals were observed to be small profiles (0.44 ± 0.27 μm2) that contained densely packed round vesicles. In tissue stained for gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) using postembedding immunocytochemical techniques, corticotectal terminals were found to contact small (0.51 ± 0.69 μm2) non-GABAergic dendrites and spines (93%) and a few small GABAergic dendrites (7%). In the same tissue, retinotectal terminals, identified by their distinctive pale mitochondria, were observed to be larger than corticotectal terminals (3.34 ± 1.79 μm2). In comparison to corticotectal terminals, retinotectal terminals contacted larger (1.59 ± 1.70 μm2) non-GABAergic dendrites and spines (73%) and a larger proportion of GABAergic profiles (27%) of relatively large size (2.17 ± 1.49 μm2), most of which were vesicle-filled (71%). Our results suggest that cortical and retinal terminals target different dendritic compartments within the neuropil of the superficial layers of the superior colliculus.

Keywords: retinoectal, corticotectal, GABA, electron microscopy synapse

The stratum griseum superficiale (SGS) and stratum opticum (SO) of the superior colliculus (SC) receive dense inputs from the retina and the visual cortex (for reviews, see Huerta and Harting, 1984; May, 2006) and these inputs interact with the SC circuitry to produce unique response characteristics. A particularly prominent feature of SGS/SO neurons is their sensitivity to stimulus movement. In addition, for many neurons, the responses elicited by a moving stimulus are dependent on the direction of motion (for review, see Waleszcyk et al., 2004). In the lower half of the SGS and in the SO, neurons have also been shown to be particularly sensitive to the movement of a visual stimulus relative to the background (Davidson and Bender, 1991). Following lesions of the visual cortex, there is a loss of direction selectivity (Rosenquist and Palmer, 1971; Berman and Cynader, 1975; Ogasawara et al., 1984) and the sensitivity to motion relative to background (Davidson et al., 1992).

The SGS and SO contain a dense distribution of neurons and terminals that contain gamma amino butyric acid (GABA), which contribute to the SC receptive field properties (Mize, 1992, 1996). To begin to understand how motion sensitivity is generated in the SC, it is therefore important to establish how corticotectal and retinotectal inputs interact with the GABAergic circuitry. As a first step toward this goal, we labeled cortical terminals via anterograde transport and examined their synaptic targets in tissue stained for GABA via postembedding immunocytochemical techniques. Retinotectal terminals in the same tissue samples were identified by their characteristic ultrastructure. The results provide further insight into the organization and function of the SC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

A total of five Harlan-Sprague-Dawley rats (235–320 g) were used for the experiments. All procedures conformed to National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the University of Louisville Animal Care and Use Committee. Thalamic tissue from these rats was used for a previously published study (Li et al., 2003).

Tracer Injections

The rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of sodium pentobarbital (initially 50 mg/kg, with supplements injected as needed to maintain anesthesia). They were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus and prepared for surgery. Biotinylated dextran amine (BDA; 5% in deionized water) was injected into cortical area 17 with a Hamilton syringe. Two injections (0.1 μl each) were placed at depths of 1.0 and 1.5 mm ventral to the cortical surface. After a survival time of 1 week, the rats were perfused transcardially with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (in mM: 125 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 D-glucose), followed by a fixative solution of 2.5% paraformaldehyde and 1.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB).

Histology

The fixed brains were cut into 50 μm thick sections with a vibratome (Leica VT1000E) and collected in a solution of 0.1 M PB. After preincubation in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.01 M PB with 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4) for 30 min, sections that contained BDA were incubated overnight at room temperature in a 1:50 dilution of avidin and biotinylated horseradish peroxidase (Vector, Burlingame, CA) in PBS, with 1% NGS (0.5% triton added to sections used for light level analysis). After three washes (10 min each) in 0.1 M PB, sections were reacted with nickel-intensified diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 5–10 min. After PB washes, sections were either mounted on slides for light level examination or prepared for electron microscopy as described below.

Electron Microscopy

Selected sections were postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in an ethyl alcohol series, and embedded in Durcupan resin (Ted Pella, Redding, CA). Ultrathin sections (80 nm; silver-gray interference color) were cut from the block using a diamond knife (Diatome, Fort Washington, PA). To avoid sampling the same terminals in multiple sections, only every 10th section was collected on Formvar-coated nickel slot grids. Every third section in this series was stained for the presence of GABA using previously reported postembedding immunocytochemical techniques (Patel and Bickford, 1997; Li et al., 2003). We used a rabbit polyclonal antibody against GABA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a dilution of 1:500 –1:2,000 and a goat-antirabbit IgG conjugated to 15 nm gold particles (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) to reveal the distribution of GABA. The GABA-stained sections were air-dried and stained with a 10% solution of uranyl acetate in methanol for 30 min before examination with an electron microscope.

Data Analysis

Ultrathin sections of the SC from cases 2003-104 and 2003-115 were scanned using a transmission electron microscope. Within each section examined, all labeled corticotectal terminals involved in synaptic contacts were photographed at a magnification of 9,800×. In the first case, 49 synaptic contacts were photographed; in the second case, 92 synaptic contacts were photographed. In the same sections, retinal terminals were identified by their characteristic ultrastructure. Both retinotectal terminals (Behan, 1981; Mize, 1983a) and retinogeniculate terminals (Robson and Mason, 1979; Hamos et al., 1987) labeled by anterograde transport have been observed to contain mitochondria with distinctive dilated cristae and light matrix, which gives them a pale appearance when compared to surrounding mitochondria that contain more typical condensed cristae. While it is impossible to determine whether all terminals that contain pale mitochondria are of retinal origin, this morphology has never been observed in terminals other than those originating from the retina. Therefore, the presence of pale mitochondria is a good predictor of retinal origin. In each case, we photographed (at a magnification of 9,800×) 66 synaptic contacts made by terminals that contained pale mitochondria.

The profiles postsynaptic to corticotectal or retinotectal terminals were characterized based on the presence or absence of vesicles, area, and overlying gold particle density. For area measurements, a digitizing tablet and SigmaScan Pro (Aspire Software International, Leesburg, VA) were used to determine the pre- and postsynaptic profile area. The number of gold particles overlying each postsynaptic profile was counted using a Scienceware Colony Counter pen (Bel-Art Products, Pequannock, NJ), and the gold particle density was determined by dividing the number of gold particles by the area of the postsynaptic profile. Since retinotectal and corticotectal terminals are known to be glutamatergic (Mize and Butler, 1996), a postsynaptic profile was considered to be GABA-positive if the gold particle density was higher than that found in 95% of either the retinotectal terminals or corticotectal terminals photographed within the same section.

RESULTS

Morphology and Distribution of Corticotectal Terminals

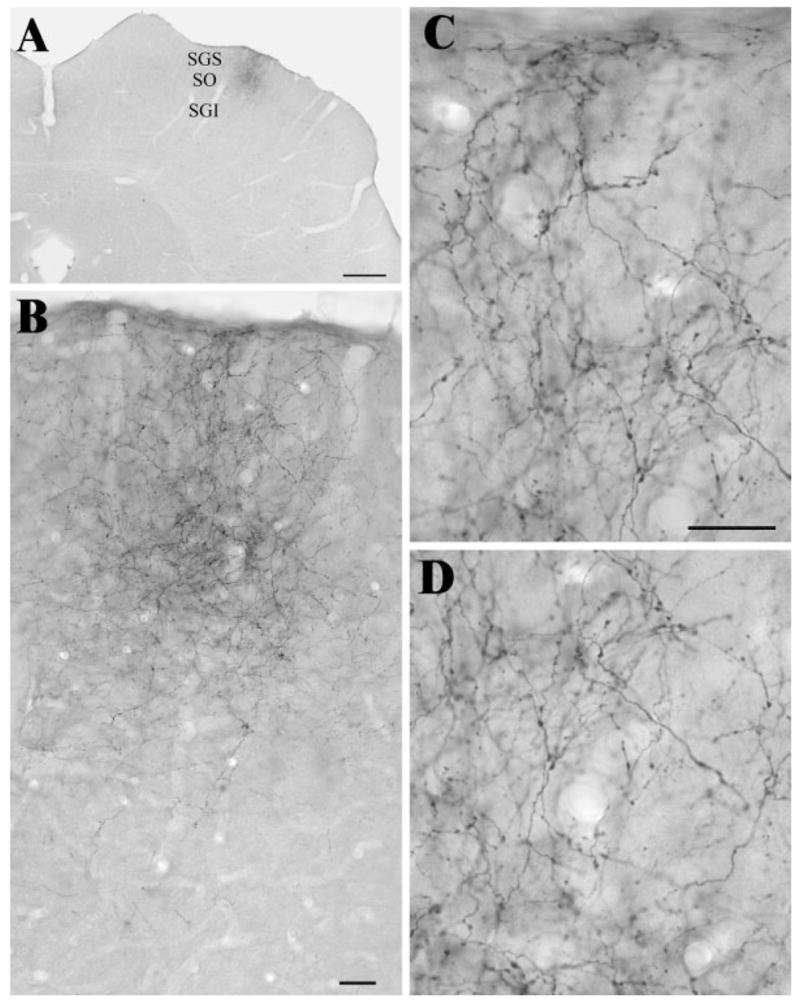

The cortical injections used for this study were described and illustrated in our previous study of corticothalamic projections (Li et al., 2003). The injections covered all layers of area 17 and in some cases also included small portions of area 18b. The labeled corticotectal terminals were distributed within a limited region within the SGS and SO (Fig. 1A and B). Corticotectal terminals were of relatively small size and displayed a varicose or beaded morphology (Fig. 1C and D). This morphology was noticeably distinct from that of corticothalamic terminals that we analyzed in tissue from the same animals (Li et al., 2003).

Fig. 1.

A: The photomicrograph illustrates the distribution of labeled terminals in a coronal section through the SC following an injection of biotinylated dextran amine in the visual cortex. The laminae of the SC are indicated. SGS, stratum griseum superficiale; SO, stratum opticum; SGI, stratum griseum intermediale. Scale bar = 1 mm. B–D: The photomicrographs illustrate the labeled terminals of A at higher magnification. Scale bars = 30 μm (B); = 20 μm (C, which also applies to D).

Ultrastructure and Synaptic Targets of Corticotectal Terminals

We examined 141 synaptic contacts made by 132 labeled cortical terminals in the middle of the SGS. The locations of the blocks of tissue examined are illustrated in Figure 2. As illustrated in Figure 3, at the ultrastructural level, labeled corticotectal terminals were observed to be small profiles (average area, 0.44 ± 0.27 μm2). Although the ultrastructure was somewhat obscured by the DAB reaction product, vesicles contained within the corticotectal terminals appeared to be mostly round in shape and relatively densely packed. Most labeled terminals also contained one or more profiles of mitochondria. Contacts made by corticotectal terminals displayed prominent postsynaptic densities, and in some cases these contact could be classified as en passant.

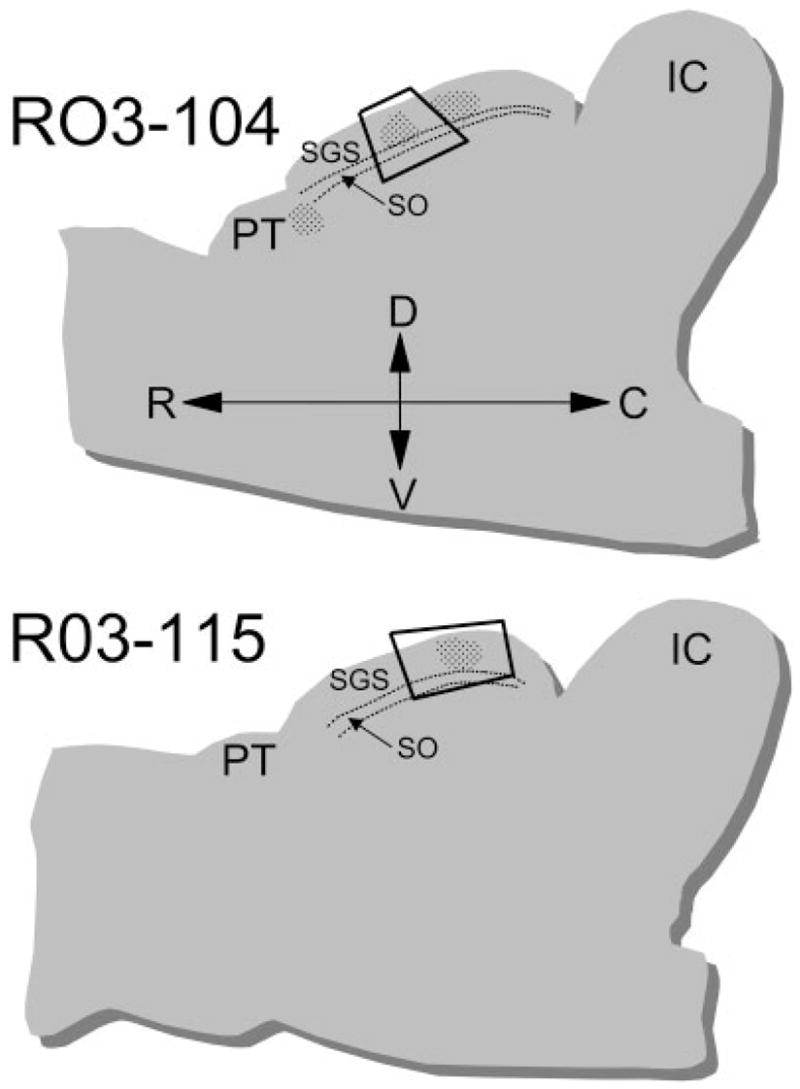

Fig. 2.

The drawings illustrate the locations within parasagittal sections of the superior colliculus, where blocks of tissue were sampled for analysis at the ultrastructural level. Two cases were analyzed: R03-14 and R03-115. The laminae of the SC are indicated. C, caudal; D, dorsal; IC, inferior colliculus; PT, pretectum; R, rostral; V, ventral.

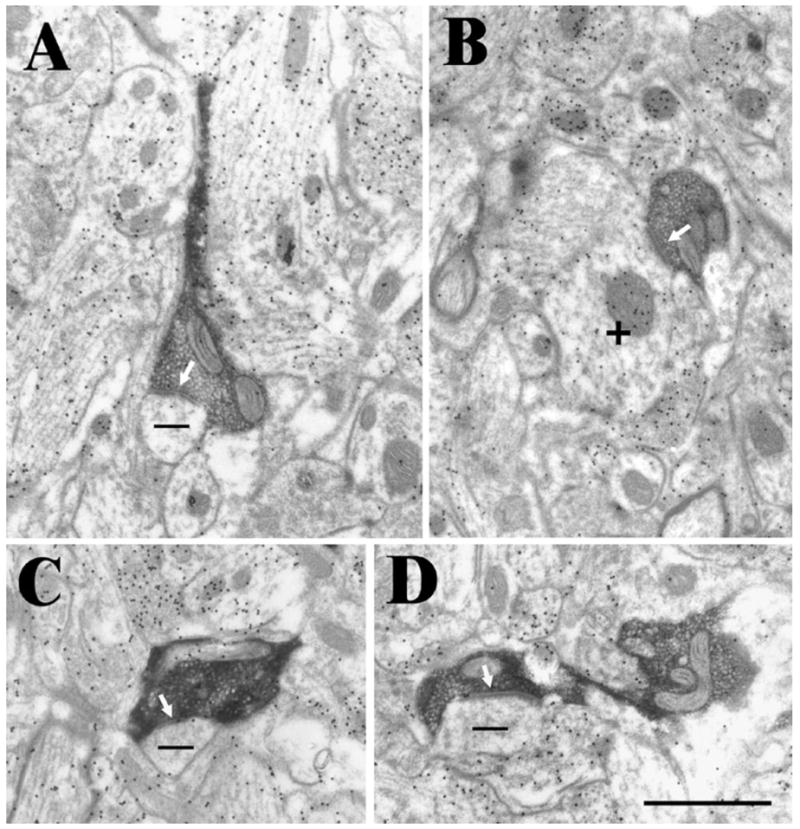

Fig. 3.

Examples of corticotectal terminals labeled by the anterograde transport of biotinylated dextran amine. These terminals primarily contact (white arrows) small non-GABAergic (−, low density of gold particles) dendrites (A, C, and D). Occasional contacts were made onto GABAergic (+, high density of gold particles) dendrites (B). Scale bar = 1 μm and applies to all panels.

Corticotectal terminals were found to contact small non-GABAergic dendrites and spines (93%; average area 0.51 ± 0.69 μm2). Many of these small dendritic profiles contained a fine flocular material consistent with their identification as spines. A small number of GABAergic dendrites were also contacted by corticotectal terminals (7%); these dendrites were also of small caliber (average area, 0.34 ± 0.32 μm2). Only 1 of the 10 postsynaptic GABAergic dendrites (10%) contained vesicles (putative presynaptic dendrite or PSD) (Mize et al., 1994).

Ultrastructure and Synaptic Targets of Retinotectal Terminals

Using the same tissue in which we examined corticotectal terminals, we identified retinal terminals by their characteristic ultrastructure, i.e., by the presence of mitochondria with distinctive dilated cristae and light matrix, which gives them a pale appearance when compared to surrounding mitochondria that contain more typical condensed cristae (Behan, 1981; Mize, 1983a). Examples of retinotectal terminals are illustrated in Figure 4.

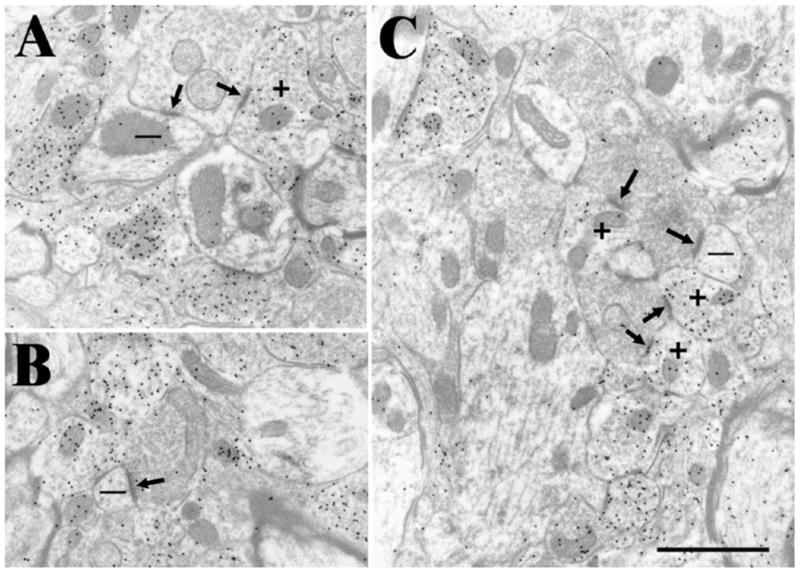

Fig. 4.

Examples of retinotectal terminals identified by their pale mitochondria. These terminals primarily contact (arrows) both non-GABAergic (−, low density of gold particles) dendrites and GABAergic (+, high density of gold particles) dendrites that contain vesicles. Scale bar =1 μm and applies to all panels. A: A retinotectal terminal contacts a GABAergic dendrite that contains vesicles and a nonGABAergic dendrite. B: A retinotectal contacts a small nonGABAergic dendrite. C: A retinotectal terminal contacts a small nonGABAergic dendrite and 3 GABAergic dendrites that contain vesicles.

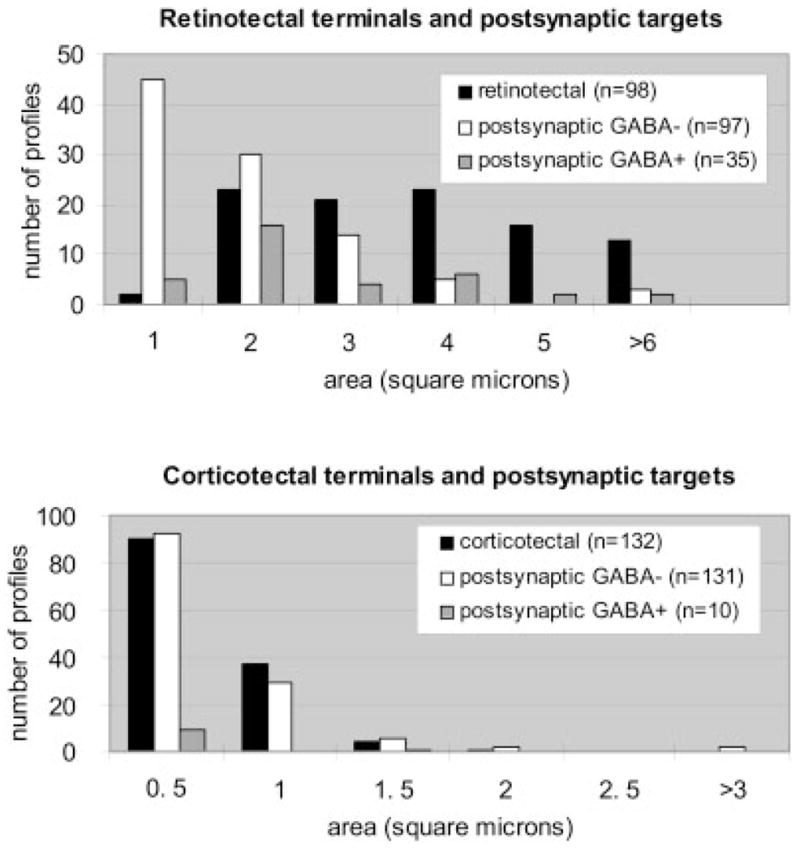

We examined 132 synaptic contacts made by 98 retinotectal terminals. In contrast to the corticotectal terminals, which primarily contacted a single profile in our single section analysis, retinotectal terminals were often observed to make multiple synaptic contacts. On average, retinotectal terminals were also larger than corticotectal terminals (3.34 ± 1.79 μm2; Fig. 5). Qualitative observations indicated that smaller retinotectal terminals were located closer to the dorsal surface of the SC, as previously reported (Behan, 1981; Mize, 1983a), but the dorsoventral position of retinotectal terminals was not measured in our sample.

Fig. 5.

The histograms compare the sizes of retinotectal and corticotectal terminals and their GABAergic and non-GABAergic postsynaptic targets. Data from both cases are combined.

Like corticotectal terminals, retinotectal terminals primarily contacted non-GABAergic profiles (73%). Many of these dendrites displayed morphologies consistent with their identification as spines. However, on average, the dendrites postsynaptic to retinotectal terminals were larger than those contacted by corticotectal terminals (average area, 1.59 ± 1.70 μm2; Fig. 5). In comparison to corticotectal terminals, retinotectal terminals also contacted a larger proportion of GABAergic profiles (27%). GABAergic dendrites postsynaptic to retinotectal terminals were also larger than those postsynaptic to corticotectal terminals (average area, 2.17 ± 1.49 μm2), and most of them were filled with vesicles (71%).

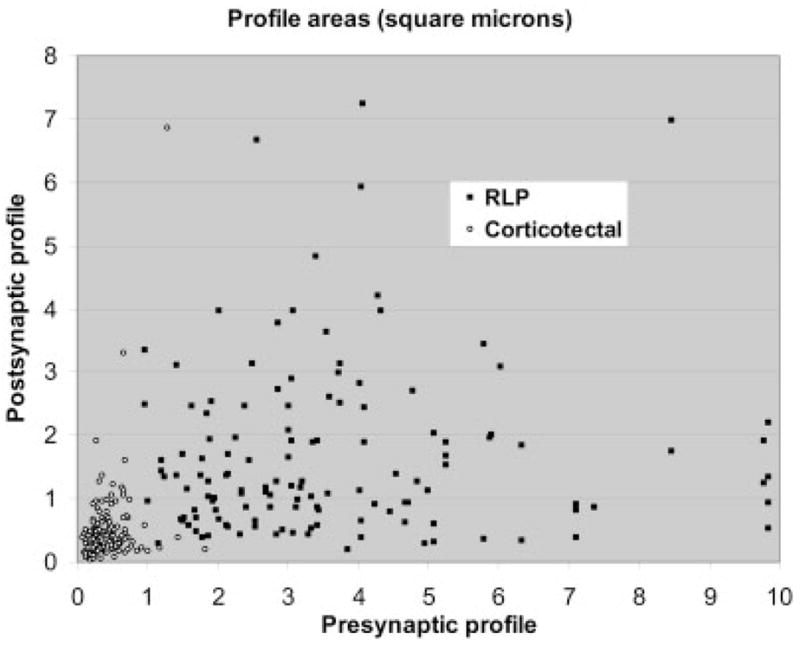

Figure 6 is a plot of the areas of profiles postsynaptic to retinal and cortical terminals as a function of the area of their presynaptic partners. The small corticotectal terminals contact smaller profiles than the larger retinotectal terminals, although there is considerable overlap in the size of profiles postsynaptic to each type of terminal. Considering the cortical and retinal terminal populations separately, there appears to be no correlation between presynaptic terminal size and postsynaptic target size.

Fig. 6.

The scatter plot compares the areas of presynaptic corticotectal and retinotectal terminals and their postsynaptic targets.

DISCUSSION

We found that area 17 corticotectal terminals are distributed throughout the SGS and parts of the SO. At the ultrastructural level, corticotectal terminals were small profiles with round vesicles that primarily contacted small-caliber GABA-negative dendrites. In the same sections, retinotectal terminals, identified by their distinctive pale mitochondria, were found to contact somewhat larger dendrites, and more contacts were made with GABAergic profiles.

Comparison to Previous Studies of Corticotectal Terminals

A number of previous studies have examined the ultra-structure and synaptic connections of corticotectal terminals in the rat (Lund, 1969), rabbit (Mathers, 1977; Holländer and Schönitzer, 1983), cat (Mize, 1983b; Behan, 1984; Mize and Butler, 1996), tree shrew (Graham and Casagrande, 1980), and Galago (Feig et al., 1992). Degeneration studies have described the majority of corticotectal terminals as relatively small profiles that undergo a dense degeneration reaction (Lund, 1969; Mathers, 1977; Graham and Casagrande, 1980; Mize, 1983b; Mize and Butler, 1996). These profiles rarely contacted more than one postsynaptic profile. Corticotectal terminals labeled by the anterograde transport of horseradish peroxidase (Holländer and Schönitzer, 1983) were also found to be small terminals that contained round, densely packed synaptic vesicles. These terminals contacted dendrites or spines and only occasional contacts were found on dendrites that contained vesicles. All of these features are similar to those of area 17 corticotectal terminals observed in the present study.

However, a number of studies have described a second, larger type of corticotectal terminal. Following lesions of areas 17 and 18 in the cat, most corticotectal terminals were small and underwent a dark degeneration reaction, but some terminals were larger and displayed a filamentous hypertrophy with degeneration (Mize and Butler, 1996). Furthermore, area 17 corticotectal terminals labeled by autoradiography in the cat were described as relatively large terminals (1.25–1.31 μm in diameter) that make multiple contacts, including dendrites with vesicles (27%) (Behan, 1984). In the Galago, two types of area 17 corticotectal terminals were labeled by autoradiography; most were small terminals that contained densely packed vesicles and primarily targeted dendritic spines, but a second population of terminals was larger and contained more loosely distributed vesicles (Feig et al., 1992). Finally, in the rat and tree shrew, most degenerating terminals observed were small and underwent an electron-dense reaction, but rare terminals displayed a large number of neuro-filaments and swollen vesicles and/or mitochondria (Lund, 1969; Graham and Casagrande, 1980).

The tracer-labeled corticotectal terminals we observed in the rat appear to form one group of small terminals. It is possible that more than one type of corticotectal cell exists, but that our dextran amine tracers were taken up by a single subset. Alternatively, corticotectal terminal morphology might vary with location. As illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, our tracer injections labeled terminals in approximately the middle of the SC; therefore, our analysis was limited to this region. We might have observed different ultrastructural features if we examined labeled terminals in other regions of the SC. For example, the rostral and caudal SC may serve distinct functions in the generation of eye movements (Munoz and Wurtz, 1992; Sugiuchi et al., 2005) and could conceivably receive distinct cortical inputs.

Corticotectal terminals in the deeper layers of the cat SC, labeled by tritiated amino acid injections in the dorsal bank of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus, were observed to be relatively large terminals (diameter, 2.16 ± 0.30) (Harting et al., 1997). Therefore, corticotectal terminal morphology may also vary with cortical area of origin. Species differences in corticotectal terminal morphology may also account for the observed morphological variations.

Is Terminal Morphology Determined by Target Structure?

Previous studies have demonstrated that cortical projections to the rodent SC originate from layer V cells (Klein et al., 1986; Schofield et al., 1987; Hallman et al., 1988; Hubener and Bolz, 1988; Kasper et al., 1994). Investigation of the axon targets of single cortical neurons suggests that the majority of corticotectal axons arise as collateral branches of corticothalamic axons (Bourassa and Deschênes, 1995). In this study, three types of cortical projections were identified: projections from upper layer VI to the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN), projections from lower layer VI to the lateral posterior nucleus (LPN) and dLGN, and projections from layer V to the LPN, laterodorsal nucleus, ventral lateral geniculate nucleus, pretectum, and SC. The morphologies of the corticothalamic axons and terminals originating from layers V and VI were found to differ. Layer VI corticothalamic axons were thin and gave rise to small terminals at the end of short side branches (type I terminals). In contrast, layer V corticothalamic axons were thick and gave rise to clusters of larger terminals in the LPN and LD (type II terminals).

We previously examined the ultrastructure of type I and type II terminals in the rat LPN (Li et al., 2003), and tissue from the same experimental animals was used for the present study. We found that type I corticothalamic terminals in the dLGN and LPN are small profiles (dLGN, 0.28 ± 0.13 μm2; LPN, 0.34 ± 0.11 μm2) and type II corticothalamic terminals in the LPN are much larger (2.27 ± 1.27 μm2). In the present study, we found that corticotectal terminals (0.44 ± 0.27 μm2) are much closer in size to type I corticothalamic terminals than type II corticothalamic terminals. This indicates that single-layer V axons give rise to large terminals in the thalamus and smaller terminals in the SC.

Single axons that give rise to terminals with distinct morphologies have been described in other systems. For example, the axons of dentate granule cells have been shown to innervate distinct postsynaptic targets via three different terminal types: large mossy terminals, filopodial extensions of the mossy terminals, and smaller en passant synaptic varicosities (Acsady et al., 1998). In addition, single axons originating from cortical layer V cells innervate the posterior thalamic nucleus with large terminals, and the pretectum, zona incerta, and deep layers of the superior colliculus with smaller terminals (Martin Deschênes, personal communication).

Comparison to Previous Studies of Retinotectal Terminals

Retinotectal terminals identified by anterograde transport have been shown to be characterized by the presence of pale mitochondria (Behan, 1981; Mize, 1983a). These studies also identified the postsynaptic targets of retinotectal terminals as conventional dendrites and presynaptic dendrites (PSD profiles). Subsequent studies in a number of species have confirmed that PSDs postsynaptic to retinal terminals are GABAergic (for reviews, see Mize, 1992, 1996). Our results are in agreement with these studies as well as a previous study of degenerating retinal terminals in the rat, which found that the primary target of retinotectal terminals was non-GABAergic dendrites, but that a substantial fraction of contacts were made with GABAergic profiles, most of which contained vesicles (Pinard et al., 1991).

Mize (1983b) also compared the distribution of retinal and cortical terminals in the cat SC and found that most retinal terminals are located superficial to cortical terminals that underwent degeneration following lesions of area 17. While we did not plot the location of each terminal photographed, we attempted to sample retinal terminals throughout the depth of the SGS. Therefore, our sample may have included terminals that originate from different types of retinal ganglion cells. In the cat, W retinotectal terminals are located in the more superficial regions of the SGS, while Y retinotectal terminals are located in the deeper regions of the SGS (McIlwain and Lufkin, 1976; McIlwain, 1978; Itoh et al., 1981).

Postsynaptic Targets of Cortical Terminals

The main finding of the present study is that area 17 corticotectal terminals primarily contact small-caliber non-GABAergic dendrites. This information is a first step toward identifying the postsynaptic targets of these tectal inputs. However, the superficial layers of the SC contain a wide variety of cell types, including interneurons and cells that project to the parabigeminal nucleus, contralateral SC, pretectum, ventral and dorsal lateral geniculate nuclei, and lateral posterior nucleus (for reviews, see Huerta and Harting, 1984; May, 2006).

SC interneurons, tectopretectal, and tectotectal neurons have been found to be GABAergic (Appell and Behan, 1990; Mize, 1992; Schmidt et al., 2001, Baldauf et al., 2003). Thus, these cell types may be ruled out as the primary targets of area 17 terminals. Although our results cannot identify which of the non-GABAergic cell types in the superficial layers of the SC are targeted by area 17 terminals, they do reveal that the postsynaptic targets are fairly small-caliber dendrites and spines. Since both retinal and cortical terminals targeted relatively small dendrites, we were unable to determine whether these two terminal types converge on single dendrites. In a double-labeling study, Hofbauer and Holländer (1986) observed convergence of retinal and cortical terminals on common postsynaptic dendrites, but these dual contacts were rare. Serial section reconstructions would be necessary to examine this issue in more detail. Nonetheless, physiological studies in the cat suggest that there is widespread convergence of cortical and retinal inputs onto individual SC neurons (McIwain and Fields, 1971; Berson, 1988), and our results are consistent with an integration of retinal and cortical inputs by individual cells. In this case, our results indicate that cortical and retinal inputs target somewhat different dendritic compartments of projection neurons, although future studies are needed to establish this relationship, as well as the identity of the specific type(s) of projection cells targeted by cortical and retinal terminals in the SC.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Eisenback and Cathie Caple for their expert electron microscopy assistance, and Martin Boyce for his helpful histology support.

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Grant number: NS35377.

LITERATURE CITED

- Acsady L, Kamondi A, Sik A, Freund T, Buzsaki G. GABAergic cells are the major postsynaptic targets of mossy fibers in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3386–3403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03386.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appell PP, Behan M. Sources of subcortical GABAergic projections to the superior colliculus in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:143–158. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf ZB, Wang XP, Wang S, Bickford ME. Pretectotectal pathway: an ultrastructural quantitative analysis in cats. J Comp Neurol. 2003;464:141–158. doi: 10.1002/cne.10792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behan M. Identification and distribution of retinocolliculuar terminals in the cat: an electron microscopic autoradiographic analysis. J Comp Neurol. 1981;199:1–15. doi: 10.1002/cne.901990102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behan M. An EM-autoradiographic analysis of the projection from cortical areas 17, 18, and 19 to the superior colliculus in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1984;225:591–604. doi: 10.1002/cne.902250409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman N, Cynader M. Receptive fields in cat superior colliculus after visual cortex lesions. J Physiol (Lond) 1975;245:61–270. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson DM. Convergence of retinal W-cell and corticotectal input to cells of the cat superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1988;60:1861–1873. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.6.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa J, Deschênes M. Corticothalamic projections from the primary visual cortex in rats: a single fiber study using biocytin as an anterograde tracer. Neuroscience. 1995;66:253–263. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RM, Bender DB. Selctivity for relative motion in the monkey superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65:1115–1133. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.5.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RM, Joly TJ, Bender DB. Effect of corticotectal tract lesions on relative motion selectivity in the monkey superior colliculus. Exp Brain Res. 1992;92:246–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00227968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig S, Van Lieshout DP, Harting JK. Ultrastructural studies of retinal, visual cortical (area 17), and parabigeminal terminals within the superior colliculus of Galago crassicaudatus. J Comp Neurol. 1992;319:85–99. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Casagrande VA. A light and electron microscopic study of the superficial layers of the superior colliculus in the tree shrew (Tupaia glis) J Comp Neurol. 1980;191:133–151. doi: 10.1002/cne.901910108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallman LE, Schofield BR, Lin CS. Dendritic morphology and axon collaterals of corticotectal, corticopontine, and callosal neurons in layer V of primary visual cortex of the hooded rat. J Comp Neurol. 1988;272:149–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.902720111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamos JE, Van Horn SC, Raczkowski D, Sherman SM. Synaptic circuits involving an individual retinogeniculate axons in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1987;259:165–192. doi: 10.1002/cne.902590202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting JK, Feig S, Van Lieshout DP. Cortical somatosensory and trigeminal inputs to the cat superior colliculus: light and electron microscopic analyses. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:313–326. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971117)388:2<313::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer A, Holländer H. Synaptic connections of cortical and retinal terminals in the superior colliculus of the rabbit: an electron microscopic double-labeling study. Exp Brain Res. 1986;65:145–155. doi: 10.1007/BF00243837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holländer H, SchÖnitzer K. Corticotectal terminals in the superior colliculus of the rabbit: a light- and electron microscopic analysis using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)—tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) J Comp Neurol. 1983;219:81–87. doi: 10.1002/cne.902190108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubener M, Bolz J. Morphology of identified projection neurons in layer 5 of rat visual cortex. Neurosci Lett. 1988;94:76–81. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta MF, Harting JK. The mammalian superior colliculus: Studies of its morphology and connections. In: Vanegas H, editor. Comparative neurology of the optic tectum. New York: Plenum; 1984. pp. 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Itoh I, Conley M, Diamond IT. Different distributions of large and small retinal ganglion cells in the cat after HRP injections of single layers of the lateral geniculate body and superior colliculus. Brain Res. 1981;207:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90684-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper EM, Larkman AU, Lubke J, Blakemore C. Pyramidal neurons in layer 5 of the rat visual cortex: I, correlation among cell morphology, intrinsic electrophysiological properties, and axon targets. J Comp Neurol. 1994;339:459–474. doi: 10.1002/cne.903390402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BG, Mooney RD, Fish SE, Rhoades RW. The structural and functional characteristics of striate cortical neurons that innervate the superior colliculus and lateral posterior nucleus in hamster. Neuroscience. 1986;17:57–78. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wang S, Bickford ME. Comparison of the ultrastructure of cortical and retinal terminals in the rat dorsal lateral geniculate and lateral posterior nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:394–409. doi: 10.1002/cne.10646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund RD. Synaptic patterns of the superficial layers of the superior colliculus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1969;135:179–208. doi: 10.1002/cne.901350205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers LH., Jr Retinal and visual cortical projection to the superior colliculus of the rabbit. Exp Neurol. 1977;57:698–712. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(77)90103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PJ. The mammalian superior colliculus: laminar structure and connections. Prog Brain Res. 2006;151:321–378. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)51011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlwain JT, Fields HL. Interactions of cortical and retinal projections on single neurons of the cat’s superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1971;34:763–772. doi: 10.1152/jn.1971.34.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlwain JT, Lufkin RB. Distribution of direct Y-cell inputs to the cat’s superior colliculus: are there spatial gradients? Brain Res. 1976;103:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90693-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlwain JT. Cat superior colliculus: extracellular potentials related to W-cell synaptic actions. J Neurophysiol. 1978;41:1343–1358. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.5.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize RR. Variations in the retinal synapses of the cat superior colliculus revealed using quantitative electron microscope autoradiography. Brain Res. 1983a;269:211–221. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize RR. Patterns of convergence and divergence of retinal and cortical synaptic terminals in the cat superior colliculus. Exp Brain Res. 1983b;51:88–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00236806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize RR. The organization of GABAergic neurons in the mammalian superior colliculus. Prog Brain Res. 1992;90:219–248. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63616-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize RR, Whitworth RH, Cardozo BN, Van der Want J. Ultra-structural organization of GABA in the rabbit superior colliculus revealed by quantitative postembedding immunocytochemistry. J Comp Neurol. 1994;341:273–287. doi: 10.1002/cne.903410211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize RR. Neurochemical microcircuitry underlying visual and oculomotor function in the cat superior colliculus. Prog Brain Res. 1996;112:35–55. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize RR, Butler GD. Postembedding immunocytochemistry demonstrates directly that both retinal and cortical terminals in the cat superior colliculus are glutamate immunoreactive. J Comp Neurol. 1996;371:633–648. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960805)371:4<633::AID-CNE11>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz DP, Wurtz RH. Role of the rostral superior colliculus in active visual fixation and executuion of express saccades. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:1000–1002. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.4.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara K, McHaffie JG, Stein BE. Two visual corticotectal systems in cat. J Neurophysiol. 1984;52:1226–1245. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.52.6.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NC, Bickford ME. Synaptic targets of cholinergic terminals in the pulvinar nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;387:266–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinard R, Benfares J, Lanoir J. Electron microscopic study of GABA-immunoreactive neuronal processes in the superficial gray layer of the rat superior colliculus: their relationships with degenerating retinal nerve endings. J Neurocytol. 1991;20:262–276. doi: 10.1007/BF01235544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson JA, Mason CA. The synaptic organization of terminals traced from individual labeled retiongeniculate axons in the cat. Neuroscience. 1979;4:99–111. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(79)90220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist AC, Palmer LA. Visual receptive field properties of cells of the superior colliculus after cortical lesions in the cat. Exp Neurol. 1971;33:629–652. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(71)90133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Boller M, Özen G, Hall WC. Disinhibition in rat superior colliculus mediated by GABAc receptors. J Neurosci. 2001;21:691–699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00691.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR, Hallman LE, Lin CS. Morphology of corticotectal cells in the primary visual cortex of hooded rats. J Comp Neurol. 1987;261:85–97. doi: 10.1002/cne.902610107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiuchi Y, Izawa Y, Takahashi M, Na J, Shinoda Y. Physiological characterization of synaptic inputs to inhibitory burst neurons from the rostral and caudal superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:697–712. doi: 10.1152/jn.00502.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waleszcyk WJ, Wang C, Benedek G, Burke W, Dreher B. Motion sensitivity in cat’s superior colliculus: contribution of different visual processing channels to response properties of collicular neurons. Aca Neurobiol Exp. 2004;64:209–228. doi: 10.55782/ane-2004-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]