Abstract

Bone marrow (BM)-derived stem cells have shown plasticity with a capacity to differentiate into a variety of specialized cells. To test the hypothesis that some cells in the inner ear are derived from BM, we transplanted either isolated whole BM cells or clonally expanded hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) prepared from transgenic mice expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) into irradiated adult mice. Isolated GFP+ BM cells also were transplanted into conditioned newborn mice derived from pregnant mice injected with busulfan (which ablates HSCs in the newborns). Quantification of GFP+ cells was performed 3-20 months after transplant. GFP+ cells were found in the inner ear with all transplant conditions. They were most abundant within the spiral ligament but were also found in other locations normally occupied by fibrocytes and mesenchymal cells. No GFP+ neurons or hair cells were observed in inner ears of transplanted mice. Dual immunofluorescence assays demonstrated that most of the GFP+ cells were negative for CD45, a macrophage and hematopoietic cell marker. A portion of the GFP+ cells in the spiral ligament expressed immunoreactive Na, K-ATPase or the Na-K-Cl transporter (NKCC), proteins used as markers for specialized ion transport fibrocytes. Phenotypic studies indicated that the GFP+ cells did not arise from fusion of donor cells with endogenous cells. This study provides the first evidence for the origin of inner ear cells from BM and more specifically from HSCs. The results suggest that mesenchymal cells, including fibrocytes in the adult inner ear, may be derived continuously from HSCs.

Keywords: Cochlea, Spiral ligament, Hearing, Mice

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian inner ear is a highly complex organ consisting of the cochlea and vestibular system which are responsible for the senses of hearing and balance, respectively. Hearing and balance disorders resulting from noise exposure, ototoxicity, aging and genetic mutations are associated with the injury or loss of various cell types in the inner ear. Common cell types lost include sensory hair cells, auditory and vestibular neurons, cells in the stria vascularis and fibrocytes in the spiral ligament (Farkashidy et al., 1963; Lim 1976; Liberman and Kiang 1978; Steel and Bock 1980; Schuknecht 1964; Schuknecht and Gacek 1993; Spicer and Schulte 2002; Kusunoki et al., 2004; Ohlemiller 2004). In the mammalian inner ear, losses of sensory hair cells and neurons are permanent with very limited if any replacement from endogenous progenitor cells (Roberson and Rubel 1994; Warchol et al., 1993; Ogata et al., 1999). In contrast, nonsensory cells like fibrocytes in the spiral ligament are able to repopulate themselves after noise or drug exposure (Roberson and Rubel 1994; Hirose and Liberman 2003; Lang et al., 2003). Evidence generated over the past several years has called attention to the critical role played by specialized fibrocytes in regulating inner ear ion and fluid homeostasis (Spicer and Schulte 1991; Minowa et al., 1999; Delprat et al., 2005). However, the mechanism whereby damaged inner ear fibrocytes are able to repair or replace themselves remains unknown.

Bone marrow (BM) stem cells have shown surprising plasticity with a capacity to differentiate into a variety of cell types. Several recent reports have demonstrated that hematopoietic or mesenchymal stem cells in BM can differentiate into specialized cells found in the eye, brain, skeletal muscle, lung, liver, stomach, kidney and skin (Corbel et al., 2003; Camargo et al., 2003; Jiang et al., 2002; Kabos et al., 2002; Krause 2002). Engraftment of BM stem cells into non-hematopoietic tissue is enhanced in injured tissues or organs (Hess et al., 2002; Krause et al., 2001). Since connective tissues including the stromal elements of the inner ear are derived from mesoderm, it seemed reasonable to speculate that BM stem cells may be involved in inner ear repair processes. In our laboratory we have devised a method to study tissue-engrafting potentials of single hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and documented that glomerular mesangial cells, brain microglial cells and pericyte-like perivascular cells are derived from HSCs (Masuya et al., 2003; Hess et al., 2004). Since both glomerular mesangial cells and pericytes are considered myofibroblasts, an activated form of fibroblasts, it is possible HSCs are a source of the fibrocytes and other mesenchymal cells in the inner ear. To test this hypothesis, we first transplanted un-manipulated GFP+ BM cells into lethally irradiated adult and busulfan conditioned newborn C57BL/6-Ly5.1 mice. We next transplanted clones of cells derived from single HSCs into irradiated adult recipients. Various types of mesenchymal cells, including fibrocytes, expressing GFP were detected in the inner ear. These observations provide the first evidence for the derivation of inner ear cells from BM and more specifically from HSCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse strains and animal care

Transgenic mice (C57BL/6-Ly5.2) with enhanced GFP were kindly provided by Dr. M. Okabe of Osaka University, Osaka, Japan (Okabe et al., 1997). C57BL/6-Ly5.1 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Both strains of mice were maintained and bred at the Animal Research Facility of the Veterans Affairs Medical Center. All aspects of the animal research were conducted in accordance with the guidelines by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Cell preparation

Ten- to 12-week-old enhanced GFP transgenic mice were used as BM donors. The mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and BM cells were flushed from tibiae and femurs, pooled and washed with Ca2+ and Mg2+ free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). GFP+ mononuclear cells (MNCs) cells with a density of 1.0875±0.0019 g/ml were collected by gradient separation using Lympholyte M (Ontario, Canada).

Lineage-negative (Lin−) BM cells were prepared by incubating BM MNCs with biotinylated anti-CD4, anti-CD8a, anti-TER-119, anti-Gr-1 and anti-B220 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Positive cells were removed with anti-biotin microbeads using a MACS separating system (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). The remaining Lin− cells were stained with allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated 2B8 (anti-c-kit), phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated D7 (anti-Sca-1) and biotinylated anti-CD34 (Becton Dickenson, San Jose, CA), followed by streptavidin-conjugated PharRed (Pharmingen). The stained cells were washed twice after the addition of propidium iodide at a concentration of 1 μg/ml, resuspended in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% BSA, and kept on ice until cell sorting. Lin−, c-kit+, Sca-1+, CD34− cells were enriched by flurorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with a FACSVantage sorter (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Single HSC culture

To achieve a high efficiency of clonal hematopoietic engraftment, we combined single cell deposition with short-term cell culture. Single Lin−, c-kit+, Sca-1+, CD34− cells were deposited into individual wells of a 96-well plate using the CloneCyt system (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry System). The culture consisted of α-modification of Eagle's medium (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA), 1% deionized fraction V BSA, 1 × 10−4 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF) and 10ng/mL granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). The 96-well plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 7 days.

To study the full differentiation potentials of HSCs, it is important to generate mice exhibiting high-level, multilineage engraftment from single HSCs. Earlier, we discovered that single cell deposition and transplantation based on Lin−, Sca-1+, c-kit+, CD34− phenotype (Osawa et al., 1996) alone was an inefficient method for producing mice with high-level engraftment. In order to raise the efficiency, we devised a method combining single cell deposition with short-term cell culture. Lin−, Sca-1+, c-kit+, CD34− cells were individually cultured for one week in the presence of SCF and G-CSF. We had shown earlier that this combination of cytokines stimulates proliferation of primitive hematopoietic progenitors (Ikebuchi et al., 1988). Because the majority of HSCs are dormant in cell cycle and begin cell divisions a few days after initiation of cell culture, selection of clones consisting of 20 or fewer cells after one-week incubation significantly enhanced the efficiency of generating mice with high level multilineage engraftment (Masuya et al., 2003; Hess et al., 2004).

Transplantation

Ten to 12 week-old and newborn C57BL/6-Ly5.1 mice were used as recipients. Adult recipient mice were prepared with a single 950-cGy dose of total body irradiation using a 4 × 106 V linear accelerator. For BM cell transplantation, 1×106 un-manipulated BM cells obtained from EGFP mice were injected into the tail veins of adult irradiated Ly5.1 mice. For clonal HSCs transplantation, the contents of a single well containing 20 or fewer cells derived from a single HSC were injected into adult irradiated Ly5.1 mice together with 500 Lin−, Sca-1+, c-kit+, CD34+ BM cells from Ly5.1 mice. The latter cell population contains only short-term repopulating cells and serves as radioprotective cells during the post-radiation pancytopenia period (Osawa et al., 1996). For the newborn transplantation studies, pregnant Ly5.1 mice were injected subcutaneously with busulfan (22.5 mg/kg) at days 17 and 18 of gestation, a procedure which ablates HSCs in the newborns. The conditioned newborn Ly5.1 mice were injected intra-peritoneally with 1× 106 un-manipulated BM cells obtained from GFP mice within 24 hours of birth. A total of 10 mice were transplanted with the three procedures and allowed to survive for 3-20 months after transplantation as listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Information on Mice Used in the Study

| Transplant method | Recipient ID | Sex of tansplant pair (donor→recipient) |

Age when transplanted |

Survival time after transplantation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult mouse with whole BM |

AB1 | F→M | 3 months | 6 months |

| AB2 | M→M | 2.5 months | 20 months | |

| AB3 | M→M | 2.5 months | 20 months | |

| Newborn mouse with whole BM |

NB1 | F→M | 0 month* | 6 months |

| NB2 | F→M | 0 month* | 6 months | |

| NB3 | M→M | 0 month* | 8 months | |

| Adult mouse with clonal HSC |

AC1 | F→M | 3 months | 3 months |

| AC2 | F→M | 3 months | 3 months | |

| AC3 | M→M | 2.5 months | 6 months | |

| AC4 | M→M | 3 months | 6 months |

The conditioned newborn mice were injected with whole BM cells within 24 hours of birth.

Flow cytometric analysis of hematopoietic engraftment

Flow cytometric analyses of hematopoietic engraftment were performed before mice were sacrificed. Peripheral blood was obtained from the retro-orbital plexus of the recipient mice using heparin-coated micropipettes (Drummond Scientific Co., Broomall, PA). Red blood cells were lysed with 0.15 M NH4Cl and the cells were stained with PE-conjugated anti-Ly5.1. The percentage of chimerism was calculated as (% GFP+ cells) × 100/ (% GFP+ cells + Ly5.1+ cells). Donor-derived cells of T-cell, B-cell, and granulocyte/monocyte/macrophage lineages were analyzed by staining with PE-conjugated anti-Thy-1.2, anti-CD45R/B220, or a combination of anti-Gr-1 and anti-Mac-1, respectively, using a FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Tissue preparation and immunocytochemistry

The inner ears were fixed for one hour with 2 % paraformaldehyde and then decalcified with EDTA. Tissues were embedded in PARAPLAST@ for paraffin sectioning. Some fixed cochleas were processed as surface preparations to directly view GFP+ cells under the basilar membrane. Deparaffinized and rehydrated sections were immersed in blocking solution for 20 minutes and then incubated overnight with a primary antibody diluted in PBS (pH 7.4) at 4 °C. The primary antibodies used in this study were: anti-mouse GFP (1:100, A11120) or anti-rabbit GFP (1:200, A11120) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), anti- rabbit Na, K-ATPase (1:2000) (Dr. George Siegel, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI), anti-mouse Na-K-Cl transporter (NKCC) (1:60 000) (Dr. Christian Lytle, Division of Biomedical Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA), anti-mouse CD45R (1:200, sc19597) (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-mouse F4/80 (1:20, MCA497) (Serotec, Kidlington, Oxford) and neurofilament 200 (1:200, N0142) (Sigma, Atlanta, GA).

Anti-GFP rabbit polyclonal and mouse monoclonal antibodies were raised against GFP isolated directly from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria and have been used for detection of native GFP, GFP variants and most GFP fusion proteins (Chalfie et al., 1994; Senut et al., 2004; Webber et al., 2004). No staining was seen when rabbit polyclonal or mouse monoclonal anti-GFP antibodies were applied to tissues from C57BL/6-Ly5.1 control mice that had not received GFP+ BM cells. The rabbit polyclonal antiserum to Na, K-ATPase (31 b) was raised against bovine brain cortex Na, K-ATPase. This antiserum recognizes most known isoforms of Na, K-ATPase and reacts with types II, IV and V fibrocytes of the spiral ligament, marginal cells in the stria vascularis and neurons in the inner ear as previously documented (Schulte and Adams 1989; Spicer and Schulte 1991; McGuirt and Schulte 1994; Spicer et al., 1997). Anti-NKCC monoclonal antibody (T4) was generated against a fusion protein encompassing the caboxy-terminal 310 amino acids of the human colonic NKCC. The T4 antibody mutually recognizes protein bands on Western blots identified as Na-K-Cl co-transporters by loop diuretic photoaffinity labeling assays and specifically localizes both the apical NKCC2 and basolateral NKCC1 isoforms of the Na-K-Cl co-transporter (Lytle et al., 1995). Immunoreactive NKCC is present in types II, IV and V fibrocytes of the spiral ligament and marginal cells in the stria vascularis (Crouch et al., 1997; Sakaguchi et al., 1998). CD45R (RA3-6B2) is a rat monoclonal IgG2a antibody raised against an extracelluar domain of the transmembrane glycoprotein CD45 and is expressed broadly among hematopoietic cells including macrophages and microglia (Bhave et al., 1998; Hirose et al., 2005). This antibody stains a single band around 232 kD on Western blots (manufacturer's technical information). Anti-F4/80 recognizes a 160 kD glycoprotein expressed by most murine macrophages and binds to macrophages and microglia in various tissues (Zhao and Lurie 2004). No immunoreactivity was seen when anti-F4/80 was used to stain liver and spleen from F4/80 deficient mice (Schaller et al., 2002). Monoclonal anti-neurofilament 200 reacted with a single 200 kDa band in both alkaline phosphatase dephosphorylated and untreated preparations of rat spinal cord (manufacturer's technical information) and specifically stains nerve fibers in the inner ear (Wise et al., 2005). Control staining for all primary antibodies including omission or substitution with similar dilution of non-immune serum of the appropriate species. No specific staining was detected in any of these control experiments.

Secondary antibodies were biotinylated and binding was detected with fluorescent (FITC)-conjugated avidin D (1:100) (Vector, Burlingame, CA). The procedure for detection of the secondary antigen with double labeling was the same as for the first antigen substituting Texas-red conjugated avidin D (1:100) (Vector, Burlingame, CA) for visualization. Nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodide or bis-benzimide.

The sections were examined with either a Zeiss LSM5 Pascal confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Jena, Germany) or a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with a 100 W mercury light source. The captured images were processed using Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, MD), Zeiss LSM Image Browser Version 3,2,0,70 (Carl Zeiss Inc., Jena, Germany) and Adobe Photoshop CS.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of Y-chromosome

In order to exclude the possibility of cell fusion causing the apparent plasticity of BM stem cells, Y-chromosome-specific FISH analysis was performed on cochlear sections from female-to-male transplant recipients as previously described (Masuya et al., 2003). Briefly, sections were deparaffinized, serially dehydrated and reacted with FITC-labeled Y-chromosome paint probe (Star-FISH; Cambio Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom). GFP+ cells were identified using rabbit anti-GFP (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) followed by CY3-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). Nuclei were counterstained with bisbenzimide. Four midmodiolar sections from each of three mice were examined. The three mice included one irradiated adult mouse that received whole BM cells (AB1) and two irradiated adult mice that received clonal HSC cells (AC1, AC2).

RESULTS

Engraftment of GFP+ cells in inner ear after whole BM transplantation into lethally irradiated adult mice

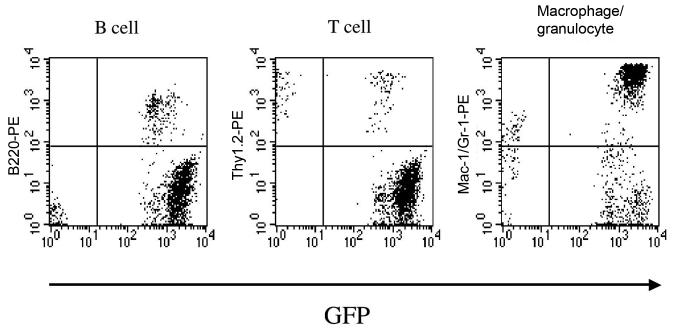

Three transplantation methods were used in this study (Tables 1 and 2). First, we transplanted unmanipulated BM cells into 10- to 12-week-old mice pretreated with a single lethal dose of total body irradiation to create BM stem cell homing space in the marrow (Collis et al., 2004). This procedure resulted in long-term reconstitution of hematopoiesis with GFP+ peripheral blood cell progeny (Table 2). Flow cytometric analysis of nucleated blood cells from a recipient mouse revealed a high level (about 95%) of multilineage engraftment 20 months after transplantation (Fig. 1). The percentages of the GFP+ cells in the B-cell, T-cell and granulocyte/macrophage lineages in this mouse were 100%, 58.7% and 95.9%, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Engraftment of GFP + Cells in the Inner Ear

| Transplant method |

Months after transplant |

% GFP cells in blood |

# of GFP + cells per section |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL | SG | VG | AN | |||

| Adult mouse with whole BM |

||||||

| AB1 | 6 | 90.0 | 18 ± 4.3 | 3.8 ±1.2 | 6±5 | 21±6 |

| AB2 | 20 | 94.9 | 18.3±4.9 | 3.3±1.2 | 9.3±2.2 | 10±3 |

| Newborn mouse with whole BM |

||||||

| NB1 | 6 | 99.3 | 4±1.7 | 3±0.8 | 4±1.8 | 6.2±2.2 |

| NB2 | 6 | 90.8 | 3±1.2 | 4.8±1.5 | 4.4±1.8 | 6.8±1.8 |

| NB3 | 8 | 97.5 | 2±0.7 | 3.2±1.2 | 3.5±1.2 | 4.2±1.1 |

| Adult mouse with clonal HSCs |

||||||

| AC1 | 3 | 77.3 | 2.7±0.5 | 0±0 | 3.7±0.6 | 4±1 |

| AC2 | 3 | 76.0 | 4±1 | 2.7±0.6 | 1.7±0.6 | 4±1 |

| AC3 | 6 | 84.4 | 7.3±0.6 | 2.5±0.3 | 5.7±3 | 2±0.3 |

| AC4 | 6 | 94.1 | 8.3±3.2 | 2±1 | 8±2.6 | 5±1 |

GFP+ cell counts in four locations were made on five midmodiolar sections taken at 25 μm intervals. SL, spiral ligament; SG, spiral ganglia; VG, vestibular ganglia; AN, auditory nerve. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D.

Fig. 1.

Multilineage hematopoietic reconstitution by cells derived from whole BM cells. Flow cytometric analysis on nucleated peripheral blood cells from lethally irradiated mice 20 months after transplantation. Reconstitution by B220+, Thy-1.2+, and Gr-1+ and/or Mac-1+ cells that are GFP+ is shown. The percentages of the engrafting cells in the B-cell, T-cell and granulocyte/macrophage lineages were 100%, 58.7%, and 95.9%, respectively.

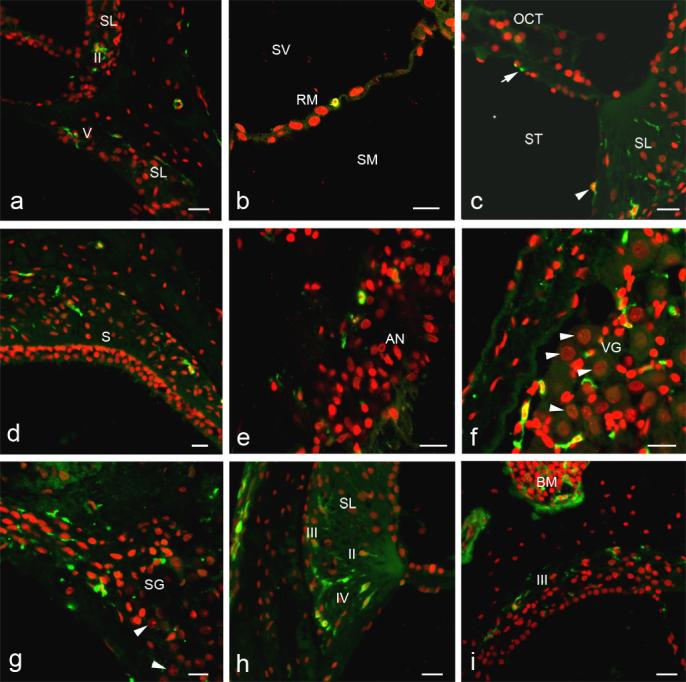

Three mice exhibiting high levels of mutilineage engraftment (90%-95%) were sacrificed at either 6 or 20 months post-transplantation. Immunostaining for GFP in paraffin sections and direct observation of basilar membrane surface preparations from these mice revealed numerous GFP+ cells in several regions of the inner ear (Figs. 2, 3, Table 2). GFP+ cells were present in the spiral ligament, limbus, Rosenthal's canal, spiral ganglia, vestibular ganglia, auditory nerve, stroma underlying the sensory epithelium of the saccule, utricle and ampullae, along Reissner's and the round window membranes, and among mesenchymal or tympanic covering cells underlying the basilar membrane and lining the bony surface of scala vestibuli and scala tympani.

Fig. 3.

Enlarged images of corresponding boxed areas in Fig. 2. a: GFP+ cells are present in the type II fibrocyte region of SL in the apical turn above and the type V fibrocyte region in the basal turn below. b: A GFP+ cell is present along RM. c: One or two processes of a GFP+ cell are present under the basilar membrane (arrow). A presumed mesenchymal cell lining the scala tympani also is GFP+ (arrowhead). d. GFP+ cells are present in connective tissue under the saccular macula (S), but hair cells and supporting cells do not express GFP. e: A few GFP+ cells are present in the auditory nerve. f: Many GFP+ cells are seen in the vestibular ganglion. Neurons are easily identified by their large spherical nuclei (arrowheads), but no neurons were GFP+. g: GFP+ cells also are present in the spiral ganglion, but again no neurons were GFP+ (arrowheads). h: GFP+ cells are present in the type II, III and IV fibrocyte regions of the SL. i: GFP+ cells are abundant in bone morrow (BM). Some GFP+ cells are present in the type III fibrocyte region. Scale bars = 40 μm.

Five types of fibrocytes reside in the spiral ligament of the mammalian inner ear as classified by their location, morphology and histochemical staining properties (Spicer et al., 1991; 1996). GFP+ cells were present in regions normally occupied by all five types of fibrocytes, although they predominated in the type II and IV fibrocyte regions (Figs. 2, 3). A few GFP+ cells were present in regions of the limbus normally occupied by fibrocytes (data not shown).

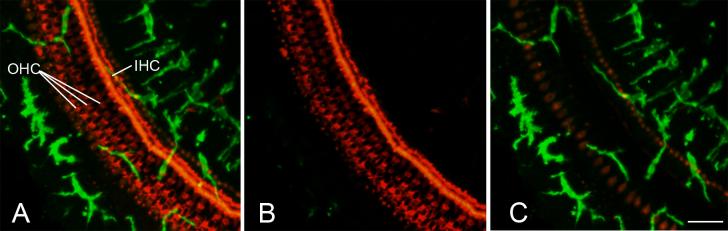

Observations of surface preparations with confocal microscopy revealed an abundant population of GFP+ cells underlying the basilar membrane (Figs. 2, 3c, 4), a site normally occupied by mesenchymal or tympanic covering cells (Kimura, 1984). No GFP+ cells were observed in the sensory epithelial compartment of the vestibular system, although some GFP+ cells were present in underlying stroma (Figs. 2, 3d). The nuclei of GFP+ cells present in the auditory and vestibular ganglia displayed small and irregular shapes most consistent with a fibrocyte or glial lineage (Figs. 3f and 3g). Auditory and vestibular ganglion neurons were readily identified by their large spherical nuclei stained with PI (Figs. 3f, 3g). High magnification evaluation of over 2000 auditory and vestibular neurons in randomly selected sections from two recipient mice revealed no GFP+ neurons. We also performed duallabeling for neurofilament 200 and GFP on six sections taken from two different mice transplanted with whole BM. None of neurofilament 200 stained cells in auditory and vestibular ganglia were positive for GFP in the examined sections. Although GFP+ cells were occasionally seen within the stria vascularis, these cells were invariably identified as blood cells by double labeling with CD45R, a hematopoietic cell marker (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Numerous GFP+ cells under the basilar membrane. Surface preparation was obtained from the other cochlea of the mouse shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Actin in hair cells and supporting cells was stained with TRITC labeled phalloidin (red). A: Image was reconstructed from all z-scan sections through and underneath the basilar membrane. B: Image was reconstructed from the z-scan sections taken from the superior-half of the basilar membrane. C: Image was reconstructed with the z-scan sections taken from the inferior-half and region underneath the basilar membrane. Scale bar = 25 μm. Abbreviations: IHC, inner hair cell; OHC, outer hair cell.

Engraftment of GFP+ cells in inner ear after whole BM transplantation into conditioned newborn mice

Whole BM cells were transplanted within 24 hours of birth into newborn mice conditioned by injecting busulfan (22.5 mg/kg) into pregnant B6-Ly5.1 mice on days 17 and 18 of gestation. Busulfan can ablate HSCs and is widely used in preparative regimens for BM transplantation (Parkman et al., 1984). All recipient mice exhibited high levels of hematopoietic reconstitution at 6-8 months after transplant (Table 2). The percentage range of GFP+ cells in B-cell, T-cell and granulocyte/macrophage lineages was 96.2%-99.6%, 75.5%-85.4% and 82.7%-95.3%, respectively.

Although GFP+ cells showed a distribution similar to that in adult mice transplanted with whole BM, there were fewer GFP+ cells particularly in the spiral ligament (Table 2). Semiquantitative analysis of GFP+ cells in the spiral ligament revealed about a 6-fold difference in the frequency of GFP+ cells in the adult mice compared to the newborn conditioned mice (Table 3). As for the whole BM transplants in adult irradiated mice, no GFP+ cells were observed in epithelial regions of the cochlea or vestibular system.

TABLE 3.

Semiquantitative Analysis of GFP+ Cells in the Spiral Ligament Six Months after Transplantation

| Transplant method | # of ears | Total cells counted | GFP + cells | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult mouse with whole BM | 2 | 2199 | 120 | 5.46% |

| Newborn mouse with whole BM | 4 | 4362 | 43 | 0.98% |

| Adult mouse with clonal HSCs | 4 | 4412 | 63 | 1.43% |

Cell counts were made on 3 to 5 midmodiolar sections at least 25 μm apart for each cochlea.

Total cells in the spiral ligament were based on nuclear counts.

Engraftment of GFP+ cells in the inner ear after clonal HSC transplantation into lethally irradiated adult mice

HSCs are defined by their ability to regenerate and repopulate all hematopoietic lineages in vivo. Transplantation studies with injection of HSCs into myeloablated recipients such as lethally irradiated mice can be used for analysis of the presence of donor cells and their ability to repopulate, thereby indicating HSC activity. In order to generate high levels of hematopoietic reconstitution from a single GFP+ stem cell, we combined FACS sorting and cell culture to generate a population of cells derived from a single HSC. Transplantation of clonal Lin−, c-kit+, Sca-1+, CD34− cells resulted in a high-level mutilineage engraftment of peripheral blood in host mice from our previous studies (Masuya et al., 2003; Hess et al., 2004).

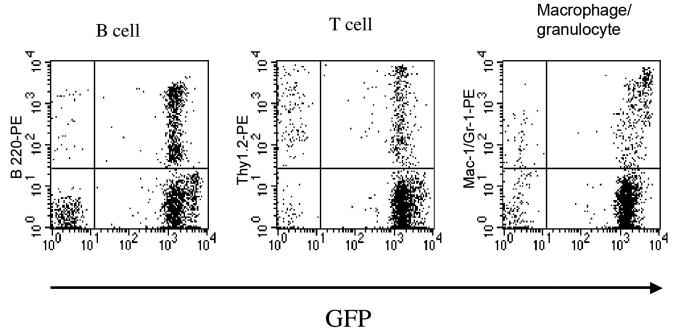

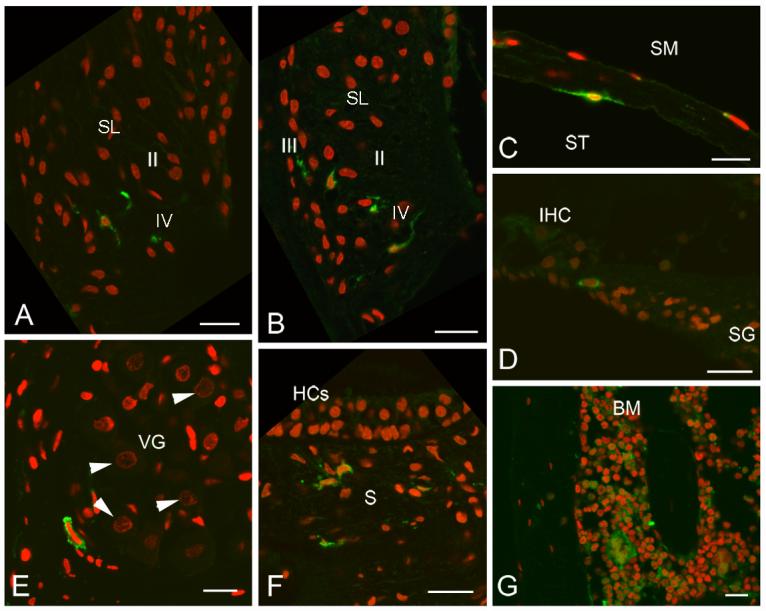

Transplantation of a clonal population of cells derived from a single Lin−, c-kit+, Sca-1+, CD34− cell into lethally irradiated mice also allowed us to fully explore the engraftment potential of HSCs in the inner ear. Clonal populations of Lin−, c-kit+, Sca-1+, CD34− cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated 10 to 12 week-old mice. From 76.0%- 94.1% of nucleated peripheral blood cells expressed GFP 3 to 6 months after transplantation (Fig. 5, Table 2). GFP+ cells were detected in all eight cochleas from these mice (Fig. 6) and had a distribution similar to that found in the whole BM transplants described above. The frequency of GFP+ cells in the spiral ligament 6 months after transplantation was 1.43%, about one-fourth of that found in irradiated adult mice transplanted with whole BM (Table 3). As with whole BM transplants, no cells were observed in epithelial regions of the inner ear.

Fig. 5.

Multilineage hematopoietic reconstitution by cells derived from a single HSC. Flow cytometric analysis of nucleated peripheral blood cells from lethally irradiated mice 6 months after transplantation. Reconstitutions by B220+, Thy-1.2+ and Gr-1+ and/or Mac-1+ cells that are GFP+ are shown. The percentages of the engrafting cells in the B-cell, T-cell and granulocyte/macrophage lineages were 95.7%, 74.0% and 87.2%, respectively.

Fig. 6.

GFP+ cells in mouse cochleas six months after clonal HSC transplantation. GFP+ cells (green) are present in several locations. Nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodide (red). A: GFP+ cells also are present in the type II and IV fibrocyte regions of the SL of the basal turn. B: GFP+ cells are present in the type II and IV fibrocyte regions of the SL of the basal turn from another cochlea. C: A bone-associated fibrocyte-like cell lining the scala tympani is GFP+. D: A GFP+ cell is present within the osseous spiral lamina. E: A GFP+ cell is present in the vestibular ganglion, but neurons identified by their large spherical nuclei (arrowheads) do not stain for GFP. F: GFP+ cells are present in the stroma under the saccular macula (S). Hair cells (HCs) and supporting cells are not GFP+. G: GFP+ cells are present in temporal bone BM. Scale bars = 40 μm.

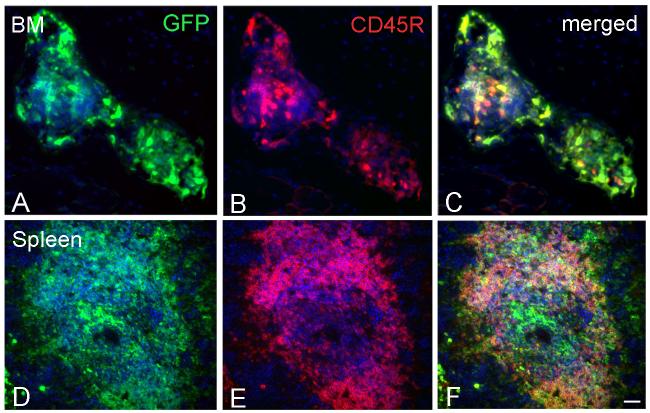

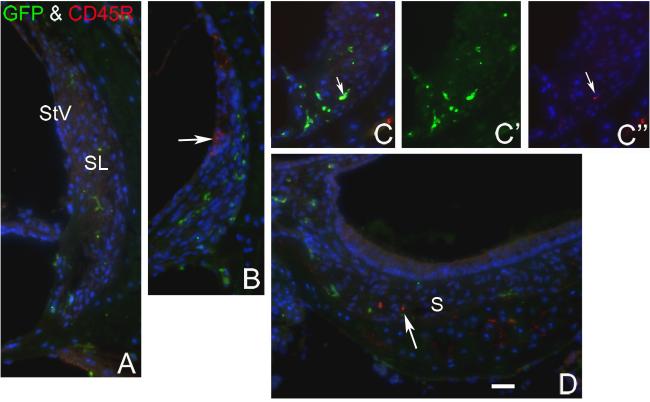

Only an occasional GFP+ cell in the spiral ligament of transplanted mice stained positively for CD45R

To investigate whether GFP+ cells in the spiral ligament were macrophages or other hematopoietic cells, we performed double labeling for GFP and CD45R (RA3-6B2) on sections from two mice transplanted with crude BM and three mice transplanted with clonal HSCs. CD45R is a monoclonal antibody that recognizes the extracellular domain of CD45, a transmembrane glycoprotein broadly expressed on hematopoietic cells (Donovan and Koretsky, 1993) in BM and elsewhere (Fig. 7). Only around 5% of GFP+ cells in the spiral ligament of the forty sections examined were also positive for CD45R (Fig. 8). Dual immunostaining with anti-F4/80 and GFP provided results similar to those seen with the CD45R antibody (data not shown). These data indicate that the majority of GFP+ cells in the spiral ligament are not macrophages or hematopoietic cells.

Fig. 7.

Dual labeling of GFP and CD45R in BM and spleen. Anti-CD45R (red) was used to investigate if any GFP+ cells (green) were differentiating towards a macrophage or other blood cell lineage. All sections were obtained 6 months after clonal HSC cell transplantation. Nuclei were counterstained with bis-benzimide (blue). C: Merged image of A and B shows many BM cells immunopositive for both GFP and CD45R. F: Merged image of D and E shows numerous cells in a germinal center of the spleen co-expressing CD45R and GFP. Scale bars = 40 μm.

Fig. 8.

Dual labeling for GFP and CD45R in the inner ear from a clonal HSC transplanted mouse. All sections were obtained from a mouse six months after clonal HSC transplant. Nuclei were counterstained with bis-benzimide (blue). A: No GFP+ cells were labeled for CD45R in a section through the apical turn. B: A few CD45R+ cells in the stria vascularis (StV) of the basal turn were GFP− (arrow). These cells were possibly blood cells in strial capillaries. C: One GFP+ cell also is immunoreactive for CD45R in a section through the basal turn (arrow). D: A few CD45R+ cells underlying the saccular macula failed to express GFP. Scale bar = 40 μm.

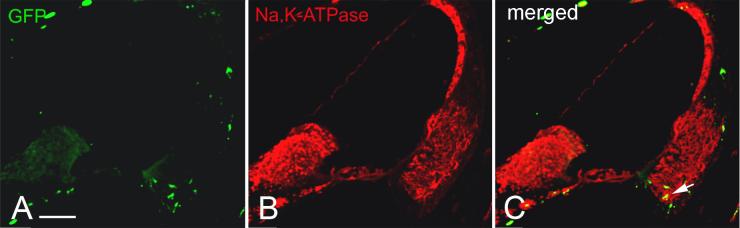

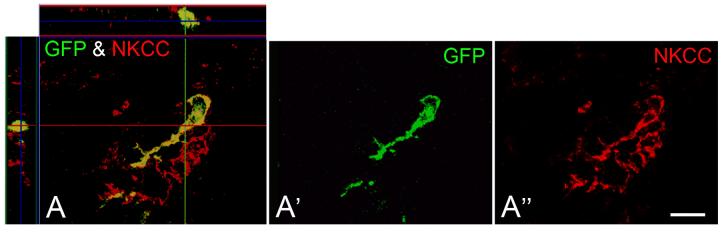

A portion of the GFP+ cells in the spiral ligament expressed Na, K-ATPase or NKCC

Immunohistochemical studies have shown high levels of Na, K-ATPase and NKCC in type II, IV and V spiral ligament fibrocytes (Schulte and Adams, 1989; Crouch et al., 1997). To further phenotype the GFP+ cells in the spiral ligament, we performed double-labeling studies with antibodies to either Na, K-ATPase or NKCC in sections from one mouse transplanted with crude BM and two mice transplanted with clonal HSCs. Subpopulations of the GFP+ cells in the type II and IV fibrocyte region were found to express Na, K-ATPase or NKCC with both transplant conditions (Figs. 9, 10).

Fig. 9.

Some engrafted GFP+ cells co-label for Na,K-ATPase. A,B,C: Dual immunolabeling for GFP (green) and Na,K-ATPase (red) in a midmodiolar section obtained from a mouse six months after clonal HSC transplantation. Staining for Na,K-ATPase is present in the stria vascularis and type II, IV and V fibrocytes in the SL. Some of the Na,K-ATPase positive cells in the type IV fibrocyte region coexpress GFP (arrow). Scale bar = 100 μm.

Fig. 10.

A GFP+ cell in a clonal HSC transplant mouse co-labels for NKCC. A, A′, A″: Three-dimensional reconstructed confocal image shows high power view of a cell in the type IV region of the SL labeled for NKCC (red) and GFP (green). The section through cochlear lateral wall was obtained from a mouse 6 months after clonal HSC transpantation. Scale bar = 15 μm.

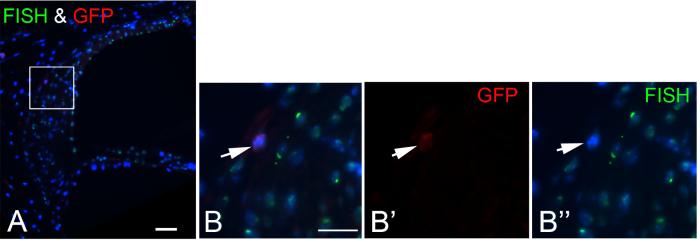

Engraftment of BM-derived cells in the cochlea is not due to cell fusion

To exclude the possibility that fusion of BM-derived cells with inner ear cells might be responsible for the above observations, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis for the Y chromosome on the inner ears of lethally irradiated males receiving female whole BM cells or clonal HSCs. The majority of endogenous cells in male recipients were labeled for the Y-chromosome signal whereas signal for the Y chromosome was not detected in any GFP+ female cell engrafted in the inner ears (Fig. 11). A total of 2810 GFP− cells were counted on twelve midmodiolar sections examined, and 87% of these cells were labeled for the Y-chromosome signal. In contrast, none of 88 GFP+ cells counted was labeled for the Y-chromosome.

Fig. 11.

GFP+ BM-derived cells in the inner ear do not result from spontaneous cell fusion. A: Section through cochlear lateral wall from a male recipient mouse that was transplanted with clonal HSCs from a female donor. The image shows that most male mouse cells are contain a Y-chromosome (green, FISH) in the nucleus (blue, bis-benzimide). B, B′, B″: Enlarged image of boxed area in Fig. A shows that a GFP+ cell (red) is negative for Y-chromosome staining. Scale bar = 40 μm.

DISCUSSION

BM and HSCs contribute to the mesenchyme and fibrocytes of the adult inner ear

Cells of mesenchymal origin are the precursors of connective tissue, which includes blood, cartilage, bone and the stromal components of organs. Mesenchymal cells typically have an irregular shape and delicate, branching cytoplasmic extensions that form an interlacing network throughout the tissue. Both sensory and nonsensory regions of the mammalian inner ear contain fibrocytes thought to be derived from mesenchymal cells. In the spiral ligament, these fibrocytes are classified into five types based on their location, morphology and histochemical properties. Type II, IV and V fibrocytes express high levels of Na, K-ATPase and NKCC (Schulte and Adams, 1989; Crouch et al., 1997), whereas type I and III fibrocytes contain high levels of creatine kinase isozyme BB and carbonic anhydrase (Spicer et al., 1997). The expression patterns of ion transport mediators along with their extensive coupling by gap junctions supports the hypothesis that strategically located fibrocytes actively take up perilymphatic K+ as part of the recycling pathway for its return to endolymph (Spicer and Schulte 1996; Forge et al., 1999; Kikuchi et al., 2000).

Using the crude BM transplantation mouse model, we found large numbers of GFP+ cells in several regions of the inner ear normally occupied by mesenchymal cells and fibrocytes. A portion of the GFP+ cells in the spiral ligament also stained positively for Na, K-ATPase or NKCC, both of which are highly expressed in type II, IV and V fibrocytes. Only a few GFP+ cells in the spiral ligament, suspected to be blood cells, were positive for CD45, suggesting that the majority of engrafted cells were not differentiating toward a macrophage or other hematopoietic cell lineage. These data suggest that mesenchymal cells of the adult inner ear, including fibrocytes, may be continuously derived from BM cells.

Our study provides the first evidence that cells derived from a single HSC can home, engraft and differentiate towards mesenchymal and fibrocyte phenotypes in the adult inner ear. Recent studies using this model of single HSC transplantation have documented the derivation of glomerular mesangial cells in kidney, and pericyte-like perivascular cells and microglial cells in the brain from HSCs (Masuya et al., 2003; Hess et al., 2004). Glomerular mesangial cells and pericytes are classified as myofibroblasts, since they exhibit features of both fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. The origin of myofibroblasts in the kidney and brain from engrafted HSCs strengthens the contention that inner ear fibrocytes and their precursors may derive from HSCs. This hypothesis also is supported by recent results showing that cultured peripheral blood cells taken from mice engrafted with clonally expanded HSCs were CD45− and expressed discoidin domain receptor 2 and collagen-I, both of which are specific markers for fibroblasts (Ebihara et al., 2004).

Bone marrow is thought to contain HSCs, stromal/mesenchymal stem cells (SSC/MSCs) and perhaps other progenitor cells. HSCs have been defined by their ability to repopulate the bone marrow and blood lineages in in vivo models such as lethally irradiated mice. SSC/MSCs are a population of BM cells that are defined by their adherent properties in vitro and also by their ability to give rise to a variety of fibroblastoid cells including adipocytes, chondrocytes, osteoblasts/osteocytes and fibroblasts (Friedenstein et al., 1970; Pittenger et al., 2001). However, cultures of plastic adherent cells elaborated from BM have been found to contain both fibroblastoid and hematopoietic cell types (Kerk et al., 1985). Although it is possible that SSC/MSCs may also have the ability to produce inner ear mesenchymal cells or fibrocytes, it is also possible that HSCs can give rise to SSC/MSCs which may then differentiate into fibrocytes. Further studies are needed to address these issues.

The spontaneous fusion of marrow-derived cells with existing tissue cells could lend the appearance of stem/progenitor cell differentiation or transdifferentiation when it does not actually occur. As an example, cells derived from purified mouse HSCs have been shown to fuse with endogenous hepatocytes, rather than to differentiate into liver hepatocytes (Wang et al., 2003; Alvarez-Dolado et al., 2003; Lagasse et al., 2000). Similarly, cells derived from transplanted BM cells were shown to fuse with Purkinje cells in the brain, rather then to transdifferentiate into neurons (Brazelton et al., 2000; Alvarez-Dolado et al., 2003). The possibility that the inner ear cells with a fibrocyte phenotype originated from fusion was excluded by FISH analyses of Y-chromosome signal in female donor-male recipient transplant experiments.

Although all three transplant protocols resulted in high levels of BM reconstitution in recipient mice, marked differences in the levels of GFP+ cell engraftment were observed in the inner ear (Tables 2 and 3). Adult mice receiving un-manipulated BM cells showed inner ear engraftment levels about four times higher than those receiving clonal HSCs. This discrepancy may reflect the presence of an additional population of stem/progenitor cells in the whole BM preparation or, alternatively, may simply reflect the much large number of cells transplanted in the whole BM procedure. Also of interest is the finding that the number of engrafted cells from whole BM transplants was about 6-fold lower in the inner ears of conditioned newborn mice versus those of irradiated adult mice. Although several factors may account for this difference, a likely possibility is that the homing and engrafting of BM-derived stem cells could be enhanced by injuries to the inner ear induced by radiation treatment (Jereczek-Fossa et al., 2003). A second possibility is that the newborn inner ear provides a less receptive environment than the adult inner ear for stem/progenitor cell engraftment and differentiation.

Possible contribution of BM-derived cells to fibrocyte homeostasis in the normal and injured inner ear

The involvement of spiral ligament pathology in hearing loss has received increased attention recently with several studies supporting the hypothesis that the highly specialized fibrocytes play an important role in cochlear physiology. Targeted deletion of the Otos gene which encodes otospiralin, a small protein produced by fibrocytes, or the POU-domain Brn4 (brain 4) gene in mice leads to selective degeneration of spiral ligament fibrocytes while hair cells, the stria vascularis and spiral ganglion neurons develop normally (Minowa et al., 1999; Phippard et al., 1999; Delprat et al., 2005). These mutations result in a reduced endocochlear potential and elevated compound action potential thresholds. Spiral ligament fibrocytes also can be injured by noise exposure, aging and ototoxic drugs (Spicer et al., 1997; Ichimiya et al., 2000; Hequembourg and Liberman 2001; Spicer and Schulte 2002; Wang et al., 2002; Hirose and Liberman 2003; Ohlemiller 2004; Hoya et al., 2004). However, unlike cochlear neurons and sensory cells which do not regenerate, fibrocytes can be replaced after noise or drug-induced injury and show a limited ability to proliferate in adults although this proliferation capacity is reduced with age (Roberson and Rubel 1994; Hirose and Liberman 2003; Lang et al., 2003).

BM-derived cells are the source of mesenchymal cells which differentiate into fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in many organs including skin, stomach, esophagus, adrenal capsule, lung and kidney. It is well established that this replacement phenomenon is exacerbated by injury (Direkze et al., 2003; Fathke et al., 2004; Quan et al., 2004; Mori et al., 2005). The findings here did not allow us to determine if BM serves as a continuing source of precursor cells for mesenchymal cells and fibrocytes in the normal inner ear because of the possibility that radiation treatment, and to a lesser extent exposure to busulfan, may cause injury and deletion of resident adult stem cells in the inner ear (Jereczek-Fossa et al., 2003). Should this prove to be the case, the data suggest that BM-derived cells may have the capacity to respond to injury by replacing or regenerating mesenchymal cells and fibrocytes in the inner ear. Alternately, radiation and busulfan treatment may exacerbate a continuous low level seeding of stem/progenitor cells to the inner ear that occurs under normal physiological conditions.

GFP+ BM-derived cells did not differentiate towards neuronal and sensory hair cell lineages

Several in vivo studies have suggested that the BM-derived cells can provide a source of neurons in the CNS (Brazelton et al., 2000; Mezey et al., 2000; Priller et al., 2001; Weimann, 2003; Mezey et al., 2003). However, the results here provide no evidence that BM-derived cells can transdifferentiate into or fuse with cochlear neurons or neurosensory hair cells in the inner ear. GFP+ cells were not detected in the sensory epithelium of the vestibular system or the organ of Corti. Although some GFP+ cells were present within the auditory and vestibular ganglia, none of these cells exhibited a neuronal morphology or was positively stained for neurofilament 200. A recent study using a similar clonal HSC transplantation procedure concluded that rare cells were dual-labeled with GFP and NeuN in infarcted areas of the brain induced by stroke (Hess et al., 2004). Another study showed that only 2-10 of over 13,000 neurons with a Purkinje cell phenotype were GFP+ in mouse brains at 10-12 months post-BM transplantation (Priller et al., 2001). These results along with our failure to detect any GFP+ neurons or hair cells suggest that genesis of neuronal or epithelial cells from BM derived cells, if it occurs at all, is a very infrequent event. However, it is possible that injury or specific microenvironmental cues may be necessary to promote the differentiation or transdifferentiation of BM derived-cells into neuronal and sensory cells in the inner ear. For example, a recent in vitro study demonstrated that a combination of sonic hedgehog and retinoic acid, signaling molecules secreted from the microenvironment surrounding sensory ganglia during embryogenesis, promotes expression of glutamatergic sensory neuronal markers in BM-derived pluripotent stem cells (Kondo et al., 2005). Further work is needed to address this important question.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides the first evidence that cells originating in BM, and in particular cells-derived from HSCs, have the capacity to engraft into the inner ear. The results suggest that mesenchymal cells, including fibrocytes in the adult inner ear, may be derived continuously from HSCs. We also hypothesize that BM-derived cells may have the capacity to attenuate cochlear injury by replacing or regenerating mesenchymal cells and fibrocytes in the inner ear. Enhancing the differentiation potential of BM progenitor cells could provide a promising therapeutic strategy for treatment of some forms of hearing loss.

Fig. 2.

GFP+ cells engrafted in a mouse cochlea six months after whole BM transplantation. Low power view of a midmodiolar section illustrates GFP+ cells (green) in many locations of the inner ear. Nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodide (red). Scale bar = 0.5 mm. Abbreviations: AN, auditory nerve; OCT, organ of Corti; PA, posterior ampulla; RM, Reissner's membrane; S, saccular macula; SG, spiral ganglion; SL, spiral ligament; SM, scala media; ST, scala tympani; SV, scala vestibuli; VG, vestibular ganglion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Haiqun Zeng and Mr. James Nicholson for their technical assistance, Mrs. Martha Harvey for her editorial assistance and the staff of the Radiation Oncology Department at the Medical University of South Carolina for the irradiation of mice.

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant number: AG14748 (R.A.S.); Grant number: DC00713 (B.A.S.); Grant number: HL69123 (M.O.); Grant number: CA102558 (D. Z.); Grant number: C06 RR014516 from the Extramural Research Facilities Program of the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Name of Associate Editor: Leslie P. Tolbert, Sensory Systems, Development, Invertebrate Neurobiology

LITERATURE CITED

- Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Fike JR, Lee HO, Pfeffer K, Lois C, Morrison SJ, Alvarez-Buylla A. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425(6961):968–73. doi: 10.1038/nature02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave SA, Oesterle EC, Coltrera MD. Macrophage and microglia-like cells in the avian inner ear. J Comp Neurol. 1998;398(2):241–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980824)398:2<241::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazelton TR, Rossi FM, Keshet GI, Blau HM. From marrow to brain: expression of neuronal phenotypes in adult mice. Science. 2000;290(5497):1775–9. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo FD, Green R, Capetanaki Y, Jackson KA, Goodell MA. Single hematopoietic stem cells generate skeletal muscle through myeloid intermediates. Nat. Med. 2003;9(12):1520–7. doi: 10.1038/nm963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263(5148):802–5. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collis Spencer J., Neutzel Sara, Thompson Travis L., Swartz Michael J., Dillehay Larry E., Collector Michael I., Sharkis Saul J., DeWeese Theodore L. Hematopoietic Progenitor Stem Cell Homing in Mice Lethally Irradiated with Ionizing Radiation at Differing Dose Rates. Radiat Res. 2004;162:48–55. doi: 10.1667/rr3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbel SY, Lee A, Yi L, Duenas J, Brazelton TR, Blau HM, Rossi FM. Contribution of hematopoietic stem cells to skeletal muscle. Nat Med. 2003;9(12):1528–32. doi: 10.1038/nm959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch JJ, Sakaguchi N, Lytle C, Schulte BA. Immunohistochemical localization of the Na-K-Cl co-transporter (NKCC1) in the gerbil inner ear. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45(6):773–8. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delprat B, Ruel J, Guitton MJ, Hamard G, Lenoir M, Pujol R, Puel JL, Brabet P, Hamel CP. Deafness and cochlear fibrocyte alterations in mice deficient for the inner ear protein otospiralin. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(2):847–53. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.847-853.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Direkze NC, Forbes SJ, Brittan M, Hunt T, Jeffery R, Preston SL, Poulsom R, Hodivala-Dilke K, Alison MR, Wright NA. Multiple organ engraftment by bone-marrow-derived myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in bone-marrow-transplanted mice. Stem Cells. 2003;21(5):514–20. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-5-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JA, Koretzky GA. CD45 and the immune response. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;4(4):976–85. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V44976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyonnas R, LaBarge MA, Sacco A, Charlton C, Blau HM. Hematopoietic contribution to skeletal muscle regeneration by myelomonocytic precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(37):13507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405361101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara Y, Masuya M, LaRue AC, Fleming PA, Visconti RP, Minamiguchi H, Drake CJ, Ogawa M. Fibroblasts, CFU-F and fibrocytes are derived from bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2004;104:193a. [Google Scholar]

- Farkashidy J, Black RG, Briant TDR. Effect of kanamycin on the internal ear: An electrophysiological and electron microscopic study. Laryngoscope. 1963;73:713–727. doi: 10.1288/00005537-196306000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathke C, Wilson L, Hutter J, Kapoor V, Smith A, Hocking A, Isik F. Contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to skin: collagen deposition and wound repair. Stem Cells. 2004;22(5):812–22. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-5-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Becker D, Casalotti S, Edwards J, Evans WH, Lench N, Souter M. Gap junctions and connexin expression in the inner ear. Novartis Found Symp. 1999;219:134–50. doi: 10.1002/9780470515587.ch9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhjan RK, Lalykina KS. The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow and spleen cells. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1970;3(4):393–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1970.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell MA, Rosenzweig M, Kim H, Marks DF, DeMaria M, Paradis G, Grupp SA, Sieff CA, Mulligan RC, Johnson RP. Dye efflux studies suggest that hematopoietic stem cells expressing low or undetectable levels of CD34 antigen exist in multiple species. Nat Med. 1997;3(12):1337–45. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DE, Stone M, Astle CM. Effects of transplantation on the primitive immunohematopoietic stem cell. J Exp Med. 1990;172(2):431–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess DC, Hill WD, Martin-Studdard A, Carroll J, Brailer J, Carothers J. Bone marrow as a source of endothelial cells and NeuN-expressing cells after stroke. Stroke. 2002;33(5):1362–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000014925.09415.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess DC, Abe T, Hill WD, Studdard AM, Carothers J, Masuya M, Fleming PA, Drake CJ, Ogawa M. Hematopoietic origin of microglial and perivascular cells in brain. Exp Neurol. 2004;186(2):134–44. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg S, Liberman MC. Spiral ligament pathology: a major aspect of age-related cochlear degeneration in C57BL/6 mice. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2001;2(2):118–29. doi: 10.1007/s101620010075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Liberman MC. Lateral wall histopathology and endocochlear potential in the noise-damaged mouse cochlea. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2003;4(3):339–52. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3036-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Discolo CM, Keasler JR, Ransohoff R. Mononuclear phagocytes migrate into the murine cochlea after acoustic trauma. J Comp Neurol. 2005;489(2):180–94. doi: 10.1002/cne.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner KC, Lenoir M, Bock GR. Distortion product otoacoustic emissions in hearing-impaired mutant mice. J Acoust Soc Am. 1985;78(5):1603–11. doi: 10.1121/1.392798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoya N, Okamoto Y, Kamiya K, Fujii M, Matsunaga T. A novel animal model of acute cochlear mitochondrial dysfunction. Neuroreport. 2004;15(10):1597–600. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000133226.94662.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimiya I, Suzuki M, Mogi G. Age-related changes in the murine cochlear lateral wall. Hear Res. 2000;39(1-2):116–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikebuchi K, Clark SC, Ihle JN, Souza LM, Ogawa M. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor enhances interleukin 3-dependent proliferation of multipotential hemopoietic progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(10):3445–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jereczek-Fossa BA, Zarowski A, Milani F, Orecchia R. Radiotherapy-induced ear toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev. 2003;29(5):417–30. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(03)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, Schwartz RE, Keene CD, Ortiz-Gonzalez XR, Reyes M, Lenvik T, Lund T, Blackstad M, Du J, Aldrich S, Lisberg A, Low WC, Largaespada DA, Verfaillie CM. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418(6893):41–9. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabos P, Ehtesham M, Kabosova A, Black KL, Yu JS. Generation of neural progenitor cells from whole adult bone marrow. Exp Neurol. 2002;178(2):288–93. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerk DK, Henry EA, Eaves AC, Eaves CJ. Two classes of primitive pluripotent hemopoietic progenitor cells: separation by adherence. J Cell Physiol. 1985;125(1):127–34. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041250117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kicic A, Shen WY, Wilson AS, Constable IJ, Robertson T, Rakoczy PE. Differentiation of marrow stromal cells into photoreceptors in the rat eye. J Neurosci. 2003;23(21):7742–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07742.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Kimura RS, Paul DL, Takasaka T, Adams JC. Gap junction systems in the mammalian cochlea. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;32(1):163–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura R. Sensory and accessory epithelia of the cochlea. In: Friedmann I, Ballantyne J, editors. Ultrastructural atlas of the inner ear. Butterworths-Heinemann Press; Londo: 1984. pp. 99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Johnson SA, Yoder MC, Romand R, Hashino E. From The Cover: Sonic hedgehog and retinoic acid synergistically promote sensory fate specification from bone marrow-derived pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(13):4789–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408239102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, Neutzel S, Sharkis SJ. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105(3):369–77. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DS. Plasticity of marrow-derived stem cells. Gene Therapy. 2002;9:754–758. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusunoki T, Cureoglu S, Schachern PA, Baba K, Kariya S, Paparella MM. Age-related histopathologic changes in the human cochlea: a temporal bone study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131(6):897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagasse E, Connors H, Al-Dhalimy M, Reitsma M, Dohse M, Osborne L, Wang X, Finegold M, Weissman IL, Grompe M. Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6(11):1229–34. doi: 10.1038/81326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang H, Schulte BA, Schmiedt RA. Effects of chronic furosemide treatment and age on cell division in the adult gerbil inner ear. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2003;4(2):164–75. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-2056-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC, Kiang NY. Acoustic trauma in cats. Cochlear pathology and auditory-nerve activity. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1978;358:1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim DJ. Ultrastructural cochlear changes following acoustic hyperstimulation and ototoxicity. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1976;85:740–751. doi: 10.1177/000348947608500604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle C, Xu JC, Biemesderfer D, Forbush B., 3rd Distribution and diversity of Na-K-Cl cotransport proteins: a study with monoclonal antibodies. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:C1496–1505. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.6.C1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuya M, Drake CJ, Fleming PA, Reilly CM, Zeng H, Hill WD, Martin-Studdard A, Hess DC, Ogawa M. Hematopoietic origin of glomerular mesangial cells. Blood. 2003;101(6):2215–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y, Kinjo K, Mulligan RC, Okano H. Unexpectedly efficient homing capacity of purified murine hematopoietic stem cells. Immunity. 2004;20(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuirt JP, Schulte BA. Distribution of immunoreactive alpha- and beta-subunit isoforms of Na,K-ATPase in the gerbil inner ear. J Histochem Cytochem. 1994;42(7):843–53. doi: 10.1177/42.7.8014467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey E, Chandross KJ, Harta G, Maki RA, McKercher SR. Turning blood into brain: cells bearing neuronal antigens generated in vivo from bone marrow. Science. 2000;290(5497):1779–82. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey E, Key S, Vogelsang G, Szalayova I, Lange GD, Crain B. Transplanted bone marrow generates new neurons in human brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(3):1364–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minowa O, Ikeda K, Sugitani Y, Oshima T, Nakai S, Katori Y, Suzuki M, Furukawa M, Kawase T, Zheng Y, Ogura M, Asada Y, Watanabe K, Yamanaka H, Gotoh S, Nishi-Takeshima M, Sugimoto T, Kikuchi T, Takasaka T, Noda T. Altered cochlear fibrocytes in a mouse model of DFN3 nonsyndromic deafness. Science. 1999;285(5432):1408–11. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5432.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori L, Bellini A, Stacey MA, Schmidt M, Mattoli S. Fibrocytes contribute to the myofibroblast population in wounded skin and originate from the bone marrow. Exp Cell Res. 2005;304(1):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata Y, Slepecky NB, Takahashi M. Study of the gerbil utricular macula following treatment with gentamicin, by use of bromodeoxyuridine and calmodulin immunohistochemical labelling. Hear Res. 1999;133(1-2):53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlemiller KK. Age-related hearing loss: the status of Schuknecht's typology. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12(5):439–43. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000134450.99615.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishimune Y. ’Green mice’ as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407(3):313–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y, Hoya N, Kamiya K, Fujii M, Ogawa K, Matsunaga T. Permanent threshold shift caused by acute cochlear mitochondrial dysfunction is primarily mediated by degeneration of the lateral wall of the cochlea. Audiol Neurootol. 2005;10(4):220–233. doi: 10.1159/000084843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa M, Hanada K, Hamada H, Nakauchi H. Long-term lymphohematopoietic reconstitution by a single CD34-low/negative hematopoietic stem cell. Science. 1996;273(5272):242–5. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkman R, Rappeport JM, Hellman S, Lipton J, Smith B, Geha R, Nathan DG. Busulfan and total body irradiation as antihematopoietic stem cell agents in the preparation of patients with congenital bone marrow disorders for allogenic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1984;64(4):852–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phippard D, Lu L, Lee D, Saunders JC, Crenshaw EB., 3rd Targeted mutagenesis of the POU-domain gene Brn4/Pou3f4 causes developmental defects in the inner ear. J Neurosci. 1999;19(14):5980–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05980.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger MF, Mbalaviele G, Black M, Mosca JD, Marshak DR. Mesenchymal stem cells. In: Koller MR, Palsson BO, Master JRW, editors. Human cell culture. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Great Britain: 2001. pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Priller J, Persons DA, Klett FF, Kempermann G, Kreutzberg GW, Dirnagl U. Neogenesis of cerebellar Purkinje neurons from gene-marked bone marrow cells in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2001;155(5):733–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan TE, Cowper S, Wu SP, Bockenstedt LK, Bucala R. Circulating fibrocytes: collagen-secreting cells of the peripheral blood. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(4):598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson DW, Rubel EW. Cell division in the gerbil cochlea after acoustic trauma. Am J Otol. 1994;15(1):28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi N, Crouch JJ, Lytle C, Schulte BA. Na-K-Cl cotransporter expression in the developing and senescent gerbil cochlea. Hear Res. 1998;118(1-2):114–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller E, Macfarlane AJ, Rupec RA, Gordon S, McKnight AJ, Pfeffer K. Inactivation of the F4/80 glycoprotein in the mouse germ line. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(22):8035–43. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.8035-8043.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF. Further observation on the pathology of presbyacusis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1964;80:369–382. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1964.00750040381003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF, Gacek MR. Cochlear pathology in presbycusis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102:1–16. doi: 10.1177/00034894931020S101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte BA, Adams JC. Distribution of immunoreactive Na+,K+-ATPase in gerbil cochlea. J Histochem Cytochem. 1989;37(2):127–34. doi: 10.1177/37.2.2536055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senut MC, Gulati-Leekha A, Goldman D. An element in the alpha1-tubulin promoter is necessary for retinal expression during optic nerve regeneration but not after eye injury in the adult zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2004;24(35):7663–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2281-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer SS, Schulte BA. Differentiation of inner ear fibrocytes according to their ion transport related activity. Hear Res. 1991;56(1-2):53–64. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90153-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer SS, Schulte BA. The fine structure of spiral ligament cells relates to ion return to the stria and varies with place-frequency. Hear Res. 1996;100(1-2):80–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer SS, Gratton MA, Schulte BA. Expression patterns of ion transport enzymes in spiral ligament fibrocytes change in relation to strial atrophy in the aged gerbil cochlea. Hear Res. 1997;111(1-2):93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer SS, Schulte BA. Spiral ligament pathology in quiet-aged gerbils. Hear Res. 2002;172(1-2):172–85. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00581-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel KP, Bock GR. The nature of inherited deafness in deafness mice. Nature. 1980;288(5787):159–61. doi: 10.1038/288159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Willenbring H, Akkari Y, Torimaru Y, Foster M, Al-Dhalimy M, Lagasse E, Finegold M, Olson S, Grompe M. Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;422(6934):897–901. doi: 10.1038/nature01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Hirose K, Liberman MC. Dynamics of noise-induced cellular injury and repair in the mouse cochlea. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2002;3(3):248–68. doi: 10.1007/s101620020028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME, Lambert PR, Goldstein BJ, Forge A, Corwin JT. Regenerative proliferation in inner ear sensory epithelia from adult guinea pigs and humans. Science. 1993;259(5101):1619–22. doi: 10.1126/science.8456285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber HA, Howard L, Bickel SE. The cohesion protein ORD is required for homologue bias during meiotic recombination. J Cell Biol. 2004;164(6):819–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimann JM, Charlton CA, Brazelton TR, Hackman RC, Blau HM. Contribution of transplanted bone marrow cells to Purkinje neurons in human adult brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(4):2088–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337659100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise AK, Richardson R, Hardman J, Clark G, O'leary S. Resprouting and survival of guinea pig cochlear neurons in response to the administration of the neurotrophins brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3. J Comp Neurol. 2005;487(2):147–65. doi: 10.1002/cne.20563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager AM, Shinn C, Shinohara M, Pardoll DM. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in the twitcher mouse. The effects of pretransplant conditioning with graded doses of busulfan. Transplantation. 1993;56(1):185–90. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199307000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Lurie DI. Cochlear ablation in mice lacking SHP-1 results in an extended period of cell death of anteroventral cochlear nucleus neurons. Hear Res. 2004;189(1-2):63–75. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]