Abstract

Data suggest that modulation of synaptic strength by incorportion of GluR4-containing AMPARs occurs during conditioned response (CR) acquisition in an in vitro model of classical conditioning. Here we extend these findings by showing that synaptically localized GluR4 subunits parallels the expression of CRs during conditioning training in which there is differential expression of CRs, such as during acquisition, extinction, and reacquisition. Moreover, colocalization and coimmunoprecipitation data suggest that Arc associates with GluR4-containing AMPARs during these different training procedures. Once induced, Arc remains present in synapses during these phases of conditioning. The results are consistent with the interpretation that synaptic incorporation of GluR4-containing AMPARs supports the expression of CRs in this preparation, and that Arc may be involved in trafficking of GluR4 subunits during conditioning. Moreover, the maintained presence of synaptically localized Arc during all phases of conditioning examined indicates that synapses do not return to their naïve state after extinction and that, given the potential trafficking function of Arc, may facilitate relearning after extinction.

Keywords: classical conditioning, in vitro, Arc, GluR4 subunits, turtles, extinction

1. Introduction

Recent interest in examining the extinction phenomenon during learning has grown because of its potential impact on clinical treatments for anxiety disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Maren & Chang, 2006). A gradual decline in learned responses, or extinction, occurs when the response is no longer paired with a reinforcing unconditioned stimulus (US). Studies suggest that extinction does not erase the original learning and is a result of new learning (Mauk & Ohyama, 2004; Myers & Davis, 2007). That is, a new association is made between the conditioned stimulus (CS) and absence of reinforcement that may be an inhibitory process suppressing the original learning. This interpretation is commonly supported by the observation of “savings” in which relearning is faster than the original learning. Despite the recent focus on extinction, it remains controversial as to whether it engages the same or different mechanisms used in the original acquisition of learned responses. Studies indicate that acquisition and extinction share some common mechanisms. For fear learning, the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) mediate both conditioning and extinction (Lin, Yeh, Lu, & Gean, 2003). Activation of NMDARs and calcium entry is also required for both (Lin et al., 2003; Suzuki, Josselyn, Frankland, Masushige, Silva, & Kida, 2004). On the other hand, there are a number of differences that distinguish mechanisms of acquisition from extinction such as the role of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels and the activation pattern of the transcription factor CREB (Lin et al., 2003; Suzuki et al., 2004). An important mechanistic difference is that acquisition of fear conditioning has been shown to drive synaptic insertion of AMPARs in the amygdala (Rumpel, LeDoux, Zador, & Malinow, 2005) while extinction training reduces surface expression of AMPARs as a result of NMDA-induced endocytosis (Mao, Hsiao & Gean, 2006).

Recent evidence is advancing the notion that the immediate-early genes (IEGs) such as activity-regulated cytoskeleton associated protein (Arc or Arg 3.1) and neuronal activity regulated pentraxin (Narp) function in the modulation of synaptic strength by regulation of AMPAR trafficking (O'Brien, Xu, Mi, Tang, Hopf, & Worley, 2002; Mokin, Lindahl, & Keifer, 2006; Rial Verde, Lee-Osbourne, Worley, Malinow, & Cline, 2006; Shepherd, Rumbaugh, Wu, Chowdhury, Plath, Kuhl, Huganir, & Worley, 2006). Induction of Arc expression is strongly linked with acquisition and consolidation of synaptic plasticity in a variety of behavioral learning tasks (Guzowski, 2002). Locally synthesized Arc mRNA is transported and accumulates selectively in activated dendritic segments of hippocampal neurons (Steward, Wallace, Lyford, & Worley, 1998; Steward & Worley, 2001). Since Arc protein interacts with cytoskeletal proteins as well as the endophilin-dynamin endocytic pathway within the postsynaptic density (PSD; Lyford, Yamagata, Kaufmann, Barnes, Sanders, Copeland, Gilbert, Jenkins, Lanahan, & Worley, 1995; Chowdhury, Shepherd, Okuno, Lyford, Petralia, Plath, Kuhl, Huganir, & Worley, 2006) it is not surprising that recent studies have revealed a neurotransmitter receptor trafficking function for Arc which is likely to underlie the behavioral changes associated with Arc expression.

In an in vitro model of eyeblink classical conditioning, evidence suggests that synaptic delivery of GluR4-containing AMPARs supports conditioning through NMDAR-mediated mechanisms and MAPK signal transduction (Keifer, 2001; Keifer & Clark, 2003; Mokin & Keifer, 2004; Keifer, Zheng, & Zhu, 2007). In this system, in place of using tone and airpuff stimuli as in behaving animals, weak electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve (the “tone” CS) is paired with strong stimulation of the trigeminal nerve (the ”airpuff” US) and results in a neural correlate of conditioned eyeblink responses recorded from the abducens nerve which controls eyeblinks in this species (Keifer, 2003, for a review). The IEG-induced protein Arc is expressed during early stages of in vitro conditioning and is transiently associated with the actin cytoskeleton and GluR4-containing AMPARs during acquisition of CRs (Mokin et al., 2006). From these data, we hypothesized that Arc may function in AMPAR trafficking during acquisition of in vitro classical conditioning. The present study was undertaken to determine the synaptic localization of GluR4 subunits during conditioning training in which there is differential expression of CRs, such as during extinction and reacquisition. A second question addressed by this study is whether Arc protein is associated with GluR4 during these processes. Here, we show by using immunocytochemistry and image analysis that synaptically localized GluR4 AMPAR subunits parallel the expression of CRs during the acquisition, extinction, and reacquisition phases of conditioning. Studies further suggest that Arc protein colocalizes and coimmunoprecipitates with GluR4 subunits during these different training procedures. These findings are consistent with the idea that Arc may be involved in GluR4 trafficking during conditioning, likely through interactions with other scaffolding and signal transduction proteins in the PSD. Moreover, Arc remains at synaptic sites throughout the extinction process. This finding suggests that synapses do not return to their naïve state during extinction and that Arc may facilitate relearning after extinction.

2. Methods

2.1 Conditioning procedures

Freshwater pond turtles Pseudemys scripta elegans obtained from commercial suppliers were anesthetized by hypothermia and decapitated. Protocols involving the use of animals complied with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The brain stem was transected at the levels of the trochlear and glossopharyngeal nerves and the cerebellum was removed as described previously (Anderson & Keifer, 1999). Therefore, this preparation consisted only of the pons with the cerebellar circuitry and the red nucleus removed. The brain stem was bathed in physiological saline (2-4 ml/min) containing (in mM): 100 NaCl, 6 KCl, 40 NaHCO3, 2.6 CaCl2, 1.6 MgCl2 and 20 glucose, which was oxygenated with 95% O2 / 5% CO2 and maintained at room temperature (22-24° C; Anderson & Keifer, 1999). Suction electrodes were used for stimulation and recording of cranial nerves. The US was an approximately two-times threshold single shock stimulus applied to the trigeminal nerve while the CS was a 100 Hz, 1 s train stimulus applied to the ipsilateral posterior root of the eighth nerve that was below the threshold amplitude required to produce activity in the abducens nerve (Keifer, Armstrong, & Houk, 1995; Anderson & Keifer, 1999; Keifer, 2001). The latter nerve will be referred to as the auditory nerve as it carries predominantly auditory fibers. Neural activity was recorded from the ipsilateral abducens nerve which projects to the extraocular muscles controlling movements of the eye, nictitating membrane, and eyelid. The CS-US interval used for conditioning procedures was 20 ms which is defined as the time between the offset of the CS and the onset of the US. This brief trace delay interval was found to be optimal for conditioning, however, it is not supported using longer trace intervals (Keifer, 2001). Intertrial interval between the paired stimuli was 30 sec. A pairing session consisted of 50 CS-US presentations followed by a 30 min rest period in which there was no stimulation. A single pairing session and a rest period has a duration of about 1 hr (55 min). Conditioned responses were defined as abducens nerve activity that occurred during the CS and exceeded the amplitude of double the baseline recording level. Explicitly unpaired stimuli using an interval randomly selected between 100 ms and 25 sec and consisting of the same number of CS and US exposures as during conditioning was used for extinction and pseudoconditioning sessions.

2.2 Protein localization, confocal imaging and data analysis

Five experimental groups were examined using immunocytochemistry: pseudoconditioned for six sessions (n = 3), conditioned for two sessions (n = 3; data from Mokin et al., 2006), early extinction, extinction, and reacquisition. The early extinction group (n = 3) consisted of preparations that were conditioned for two pairing sessions followed by two sessions of extinction trials. These experiments were terminated before the CRs were completely extinguished to a mean of 34% CRs. The extinction group (n = 3) consisted of preparations in which conditioning was followed by three sessions of extinction trials which completely abolished expression of CRs to a mean of 4%. The reacquisition group (n = 3) consisted of preparations that were conditioned, underwent complete extinction, followed by robust CR reacquisition to a mean of 98%. Immediately after the physiological experiments, brain stems were immersion fixed in cold 0.5% paraformaldehyde for immunocytochemical processing (Mokin & Keifer, 2004). Tissue sections were cut at 30 μm and preincubated in 10% normal goat serum for 1 h followed by incubation in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. The primary antibodies used were a polyclonal antibody raised in goat that recognizes the GluR4 subunit of AMPA receptors (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA,, 7614), a monoclonal antibody raised in mouse that recognizes synaptophysin (1:1000; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, 5768), and a polyclonal antibody raised in rabbit that recognizes Arc (1:1000; Santa Cruz, 15325). After incubation in the primaries, sections were rinsed and incubated with the appropriate Cy2-, Cy3- or Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h using a concentration of 1:100 for GluR4 and Arc, or 1:200 for synaptophysin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Sections were rinsed, mounted on slides and coverslipped. Images of labeled neurons in the principal or accessory abducens motor nuclei were obtained using an Olympus Fluoview 500 laser scanning confocal microscope. Tissue samples were scanned using a 60× 1.4 NA oil immersion objective with triple excitation using a 488 nm argon laser, a 543 nm HeNe laser, and a 633 nm HeNe laser. Quantification of punctate staining of at least twofold greater intensity above background was performed using stereological procedures with MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging Corp., Downingtown, PA), which was described in detail elsewhere (Mokin & Keifer, 2006). Images of two consecutive optical sections were taken using confocal microscopy. Protein puncta were counted in one optical section (sample section) if they were not present in the optical section immediately below the sample section (look-up section) and if they were within the inclusion boundaries of the unbiased counting frame. Colocalized staining was determined when puncta were immediately adjacent to one another or if they were overlapping. All data were analyzed using StatView software (SAS, Cary, NC) by ANOVA.

2.3 Western blot analysis

Brain stem preparations underwent pseudoconditioning for six sessions (n = 3), complete extinction (n = 3), or reacquisition (n = 3), and were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was homogenized and centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min at 4° C and supernatants recentrifuged at 20,000 g for 20 min. Pellets were resuspended in ice-cold high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade water and clarified by centrifugation at 48,000 g for 20 min at 4° C. Final pellets were resuspended in 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), aliquotted and stored at −70° C. Protein sample concentrates were solubilized in 2× SDS/β-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 3 min prior to separation by 8% SDS-PAGE. Following electrophoresis, membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS/0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h at 4°C. The membranes were incubated with the same primary antibodies used for immunocytochemistry (1:500) overnight in PBS/0.1% Tween-20/0.1%BSA at 4° C, washed, and incubated in HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:100,000) for 2 hr at room temperature. Loading controls were performed using primary antibodies to actin (1:500; Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Proteins were detected using the ECL-Plus chemiluminescence system (Amerisham Pharamcia, Piscataway, NJ). Immunoreactive signals were captured on Kodak X-omatic AR film and quantified by computer assisted densitometry.

2.4 Coimmunoprecipitation

Coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed on brain stem preparations that underwent pseudoconditioning for two sessions (n = 3; to an average of 0% CRs), conditioning for two sessions (n = 3; 92% CRs), early extinction (n = 3; 49% CRs), complete extinction (n = 3; 16% CRs), or reacquisition (n = 3; 100% CRs). Brain stems were homogenized in lysis buffer with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Protein A-Agarose beads slurry (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was added to cell lysates and incubated on ice for 2 hr. Samples were spun at 6,000 × g for 5 min at 4° C, the supernatant retained, and incubated with primary antibodies (same antibodies as used for western blotting) or nonspecific rabbit IgGs (Santa Cruz) at 4° C for 4 h. Agarose beads slurry was then added to the protein samples and incubated at 4° C overnight. After incubation, beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, solubilized in 2× SDS-β-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 5 min to elute the proteins. Eluates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk, incubated with primary antibodies overnight, washed and incubated in HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunoreactivity was visualized by chemiluminescence. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments were repeated at least twice on the three different preparations per group.

2.5 Subcellular fractionation

Crude PSD fractions were obtained by subcellular fractionation according to previously published procedures (Dunkley et al., 1988). All procedures were performed at 4° C in the presence of protease inhibitors (complete Mini/EDTA-free; Roche). Brain stems that underwent pseudoconditioning or extinction for a total of six sessions (n = 3 similarly responding preparations per group were combined to obtain an adequate amount of tissue samples) were homogenized in HEPES buffer (4 mM HEPES/NaOH, 0.32M sucrose, pH 7.4). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min and the supernatant extracted. The supernatant was centrifuged in discontinuous Percoll gradient (3%-10%-23%) at 33,000 g for 8 min and the interface between 10% and 23% Percoll was collected to yield the crude synaptosomal fraction. This fraction was mixed with PSD buffer (PSDB; 40 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 8.1) and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 20 min. The pellet was resuspended in PSDB to obtain the final synaptosomal fraction. This was mixed with PSDB diluted 1:1 with 1% Triton X-100 and centrifuged at 40,000 g for 1 hr to yield the PSD fraction. Protein sample concentrations were determined using Bradford Reagent assay and the fractionation confirmed by Western blotting using antibodies against the presynaptic marker synaptophysin and the postsynaptic protein PSD-95 (Santa Cruz).

3. Results

3.1 CR acquisition, extinction and reacquisition

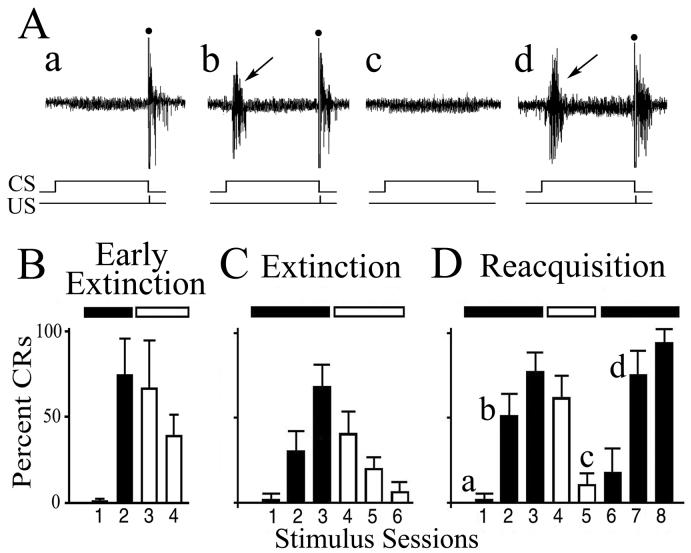

Acquisition curves of abducens CRs obtained in the present study from the different experimental groups and representative recordings from the abducens nerve are shown in Fig. 1. Examples of abducens nerve recordings taken from an experiment in which CR acquisition was followed by extinction and reacquisition is shown (Fig. 1A). A record taken at the beginning of the conditioning procedure shows the UR alone (Fig. 1Aa) while later in conditioning a burst discharge characteristic of abducens CRs in response to the CS is recorded (Fig. 1Ab, arrow) followed by the UR. The CRs gradually decline when the CS and US are explicitly unpaired during extinction trials (Fig. 1Ac) and are once again recorded when the stimuli are paired during reacquisition training (Fig. 1Ad, arrow). The acquisition curves show that abducens CRs were acquired after two or three stimulus sessions in which the CS and US were paired (Fig. 1B-D, black bars). Paired stimuli were followed with unpaired extinction trials during which the CRs declined within two or three stimulus sessions (Fig. 1B-D, white bars). In the present study, there were two groups of extinction cases: early extinction (Fig. 1B) in which experiments were terminated prior to complete reduction of CRs, and extinction (Fig. 1C) in which CRs were nearly completely abolished. For reacquisition experiments, presentation of paired stimuli was resumed following extinction trials which produced a faster rate of CR acquisition compared to the initial rate of conditioning (Fig. 1D). Similar findings for reacquisition were also observed in earlier studies using this preparation (Anderson & Keifer, 1997).

Fig. 1.

Acquisition curves for preparations that underwent extinction or reacquisition conditioning procedures and processed for immunocytochemistry. (A) Physiological recordings taken from one experiment in which the preparation demonstrated CR acquisition (b; CR indicated by the arrow) followed by extinction (c) and reacquisition (d). The occurrence of the CS and US are indicated below the recordings. (B) Acquisition curve from the early extinction group (n = 3) in which the extinction process was terminated before conditioning was completely abolished. (C) Acquisition curve from the extinction group (n = 3) shows that conditioning was completely extinguished by the end of the third extinction session. (D) In the reacquisition group (n = 3), expression of CRs was extinguished and then reinstated demonstrating a faster rate of reacquisition compared to the initial levels of conditioning. Black bars indicate paired CS-US trials, white bars indicate unpaired stimulus trials.

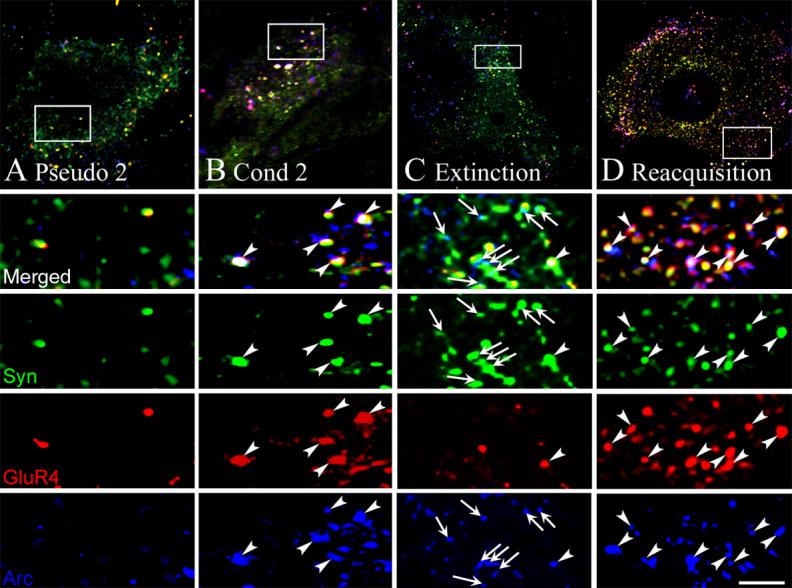

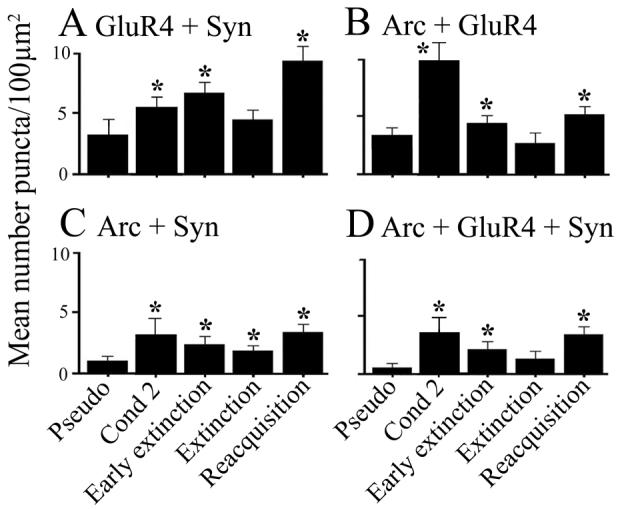

3.2 Synaptic localization of GluR4-containing AMPARs and Arc after CR acquisition, extinction and reacquisition

Previously (Mokin et al., 2006), we showed by colocalization and coimmunoprecipitation studies that Arc protein was associated with GluR4-containing AMPARs during CR acquisition after two pairing sessions but not during CR expression later in conditioning after GluR4 subunits had been delivered to synapses. In this preparation, CRs are generated by abducens motor neurons that control eyeblinks in this species (Keifer, 1993) and these neurons were examined for colocalization of punctate staining for Arc protein, GluR4 glutamate receptor subunits, and synaptophysin which was used as a marker of synaptic sites. Representative confocal images of abducens motor neurons from the different experimental groups are shown in Fig. 2. In addition to the experimental groups reported here, previous data obtained after conditioning for two sessions are reproduced for comparison (Figs. 2-3; data from Mokin et al., 2006). Following pseudoconditioning for two pairing sessions there is relatively little colocalization of GluR4 or Arc with synaptophysin (Fig. 2A). Two sessions of conditioning in which there was CR acquisition resulted in greatly increased triple colocalization of Arc-GluR4-Syn as was reported previously (Fig. 2B, arrowheads, white pixels; Mokin et al., 2006). After CR extinction in which CRs were nearly completely abolished, there is relatively little triple label colocalization (Fig. 2C, arrowheads, white pixels). Interestingly, however, there are high levels of colocalized Arc and synaptophysin after extinction (Fig. 2C, arrows, turquoise pixels). Following reacquisition, as during the initial stages of conditioning, there is again considerable triple label colocalization of Arc-GluR4-Syn (Fig. 2D, arrowheads). Punctate staining was quantified using stereological procedures (Mokin & Keifer, 2006) and these data are summarized in Fig. 3. Typically after two sessions of conditioning, there is significantly greater colocalization of GluR4-containing AMPARs with synaptophysin, or GluR4 with Arc, compared to pseudoconditioned cases (Fig. 3A-B, GluR4+Syn; F(1,49) = 35.4, p < 0.0001; Arc+GluR4, F(1,49) = 27.9, p < 0.0001) resulting in enhanced triple-label colocalization of Arc-GluR4-Syn (Fig. 3D, Arc+GluR4+Syn; F(1,49) = 63.6, p < 0.0001). Analysis of staining after complete CR extinction shows there are no significant differences in GluR4 subunit colocalization with synaptophysin compared to pseudoconditioned cases (Fig. 3A, Extinction; F(1,52) = 1.1, p = 0.46), or GluR4 with Arc (Fig. 3B; F(1,52) = 0.8, p = 0.38), suggesting that GluR4 subunits were no longer localized to synapses or associated with Arc protein. However, significantly enhanced levels of Arc with synaptophysin is observed after extinction suggesting that Arc protein remained at synaptic sites (Fig. 3C; F(1,91) = 7.9, p = 0.006). In contrast to these findings on CR extinction, after reacquisition when high levels of CRs were expressed, colocalization of GluR4 with synaptophysin (Fig. 3A; F(1,52) = 57.4; p < 0.0001), and GluR4 with Arc (Fig. 3B; F(1,52) = 41.0, p < 0.0001), is significantly increased above pseudoconditioned levels. Therefore, during reacquisition of abducens CRs, GluR4 subunits were once again localized to synaptic sites and associated with Arc protein (Fig. 3D; F(1,52) = 64.4, p < 0.0001) as was the case during acquisition.

Fig. 2.

Confocal images of GluR4 (red), synaptophysin (green) and Arc (blue) punctate staining after pseudoconditioning, conditioning, extinction, and reacquisition. (A) An abducens motor neuron from a preparation that was pseudoconditioned for two pairing sessions (Pseudo 2) showed minimal colocalization of Arc and GluR4 at synaptic sites. The squares in the upper panels indicate the location of the higher magnification images. (B) After conditioning for two sessions (Cond 2), there was significantly increased colocalization of Arc and GluR4 with synaptophysin as is indicated by the white pixels (arrowheads). (C) Following extinction, increased synaptic localization of Arc was observed (arrows indicate colocalized Arc and synaptophysin puncta). However, there was little colocalization of GluR4 and Arc with synaptophysin. (D) Reacquisition was again characterized by high levels of colocalized of Arc and GluR4 at synaptic sites (arrowheads). Scale bar for lower panels = 2 μm.

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analysis of GluR4, synaptophysin and Arc punctate staining from the different treatment groups. (A) GluR4 colocalization with synaptophysin, indicating its presence at synaptic sites, is significantly increased above pseudoconditioned levels after conditioning, early extinction and reacqusition stages of conditioning, but is similar to pseudoconditioned levels after extinction. (B) Colocalization of Arc with GluR4 is increased after conditioning, early extinction and reacquisition, but is low after extinction. (C) Synaptic localization of Arc remains significantly elevated throughout the conditioning and extinction stages examined. (D) Colocalization of Arc and GluR4 subunits at synaptic sites was significantly elevated after all experimental procedures except after extinction. P values are given in the text.

Given the finding that Arc was not colocalized with GluR4 subunits after extinction had been completed, question remained concerning the interaction of Arc and GluR4 during the early phase of extinction. That is, is Arc associated with GluR4 subunits during synaptic withdrawal of AMPARs while the extinction process was underway? Since the extinction phase of conditioning was studied after it was essentially completed in the experiments described above, the early stage of extinction was examined when CRs were declining but before they were completely abolished (Fig. 1B). Consistent with the high level of CR expression in early extinction cases, significant colocalization of GluR4-containing AMPARs with synaptophysin is observed compared to pseudoconditioned cases (Fig. 3A, Early Extinction; F(1,48) = 36.6, p < 0.0001). Significantly, increased colocalization of Arc-GluR4 (Fig. 3B; F(1,54) = 11.9, p = 0.001), and Arc-GluR4-Syn (Fig. 3D; F(1,54) = 6.6, p = 0.01) is observed after early extinction compared to complete extinction. In summary, the immunocytochemical data show that GluR4-containing AMPARs are present in synapses when CRs are expressed during acquisition, early extinction and reacquisition, and that Arc is colocalized with GluR4 subunits during these phases of conditioning when receptor trafficking is high.

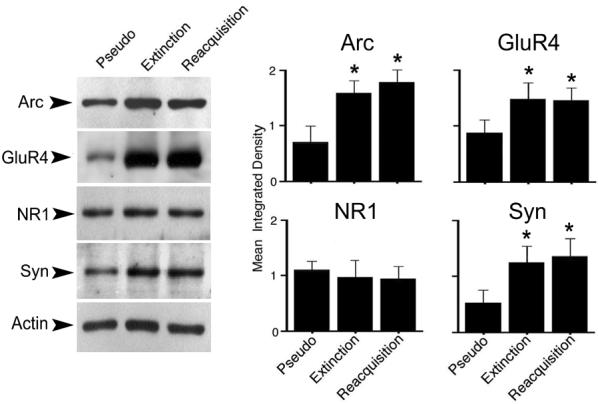

3.3 Protein expression during extinction and reacquisition

Following extinction or reacquisition experiments, brain stems were processed for protein analysis. Similar to preparations conditioned for two sessions (Mokin et al., 2006), the level of Arc protein was significantly enhanced compared to pseudoconditioned levels after both extinction and reacquisition phases of conditioning (Fig. 4, Arc; F(2,6) = 6.1, p = 0.03 and p = 0.01, respectively). A similar pattern of elevated expression after extinction and reacquisition was also observed for GluR4 AMPAR subunits (Fig. 4, GluR4; F(2,6) = 4.7, p = 0.03 and p = 0.03, respectively). However, no significant changes were observed in NR1 subunits whose levels remained stable throughout the conditioning procedures (Fig. 4, NR1; F(2,6) = 0.1, p = 0.72 and p = 0.62, respectively). Previously, we observed significantly increased levels of the presynaptic protein synaptophysin after early stages of conditioning that is blocked by the NMDAR antagonist AP-5 (Mokin & Keifer, 2004; Mokin et al., 2006). Here, the levels of synaptophysin remained significantly increased after both extinction and reacquisition (Fig. 4, Syn; F(2,6) = 9.8, p = 0.01 and p = 0.006, respectively). Therefore, once induced by conditioning, protein levels for Arc, GluR4 and synaptophysin remained elevated during extinction and reacquisition of abducens CRs.

Fig. 4.

Expression of Arc, GluR4 and synaptophysin protein is significantly enhanced after extinction and reacquisition compared to pseudoconditioned controls, whereas NR1 expression remains unchanged. Exemplar blots are shown at left while averaged data (n = 3/group) are shown at right. Loading controls for actin are also shown. P values are given in the text.

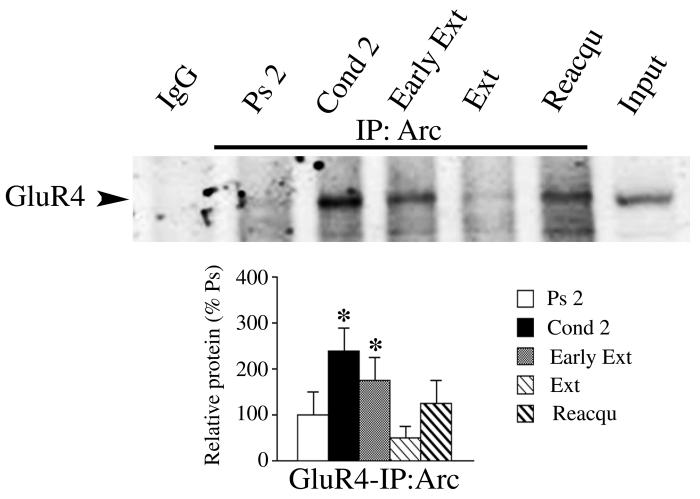

3.4 Conditioning-related association of GluR4 and Arc as shown by coimmunoprecipitation

The immunocytochemical data revealed colocalization of GluR4 and Arc paralleling the expression of CRs. An association of GluR4 subunits and Arc during these stages of conditioning was further supported by coimmunoprecipitation experiments shown by a representative immunoblot and quantitative data in Fig. 5. Following acquisition of CRs after two pairing sessions, a strong interaction between Arc and GluR4 was observed compared to pseudoconditioned levels (Fig. 5, Cond 2 lane; F(1,8) = 11.5, p = 0.0006) as was reported previously (Mokin et al., 2006). After extinction of conditioning had been completed, when low levels of CRs were expressed, minimal interaction among Arc and GluR4 was observed (Fig. 5, Ext lane; F(1,8) = 2.6, p = 0.18). However, following reacquisition of CRs association of Arc and GluR4 was again detected by coimmunoprecipitation, although the quantitative results were not significant (Fig. 5, Reacqu lane; F(1,8) = 0.4, p = 0.47). Unlike the extinction group, coimmunoprecipitation of Arc with GluR4 after early extinction was significantly elevated above pseudoconditioned levels (Fig. 5, Early Ext lane; F(1,7) = 3.8, p = 0.05). In sum, the coimmunoprecipitation data for GluR4 and Arc confirmed the colocalization findings for these proteins shown in Fig. 3B. Together, these data suggest an enhanced interaction of GluR4 subunits with Arc during the acquisition, early extinction, and reacquisition phases of conditioning.

Fig. 5.

Coimmunoprecipitation of GluR4 subunits with Arc for the different stages of conditioning examined. Representative coimmunoprecipitation (n = 3/group) shows an increased interaction of the two proteins after two sessions of conditioning (Cond 2) compared to pseudoconditioned controls (Ps 2). Association of Arc with GluR4 was also high after early extinction (Early Ext) trials, but was dramatically reduced after extinction (Ext). Interaction of Arc with GluR4 was again detected after reacquisition of CRs (Reacqu). Quantitative data show coimmunoprecipitation of Arc and GluR4 is increased after conditioning, early extinction and reacquisition experiments compared to pseudoconditioning. Control lanes show immunoprecipitation with nonspecific IgG or normal immunoblotting signal for GluR4.

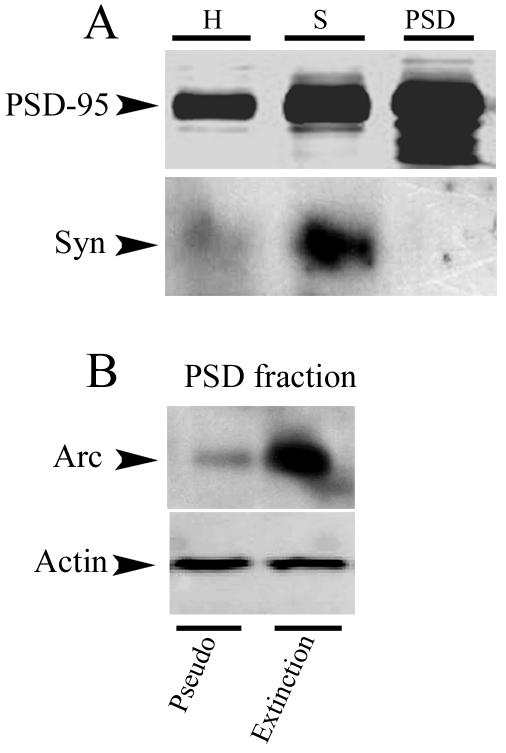

3.5 Detection of Arc in the PSD fraction after extinction

Subcellular fractionation of turtle brain stems that were pseudoconditioned or underwent complete extinction was performed to confirm the synaptic presence of Arc after extinction of conditioning that was indicated by the immunocytochemical data. Crude PSD fractions were isolated as demonstrated in Fig. 6A. These showed increasingly higher amounts of PSD-95 during the purification procedure with minimal contamination from presynaptic components as shown using synaptophysin as a marker. Immunoblotting showed a high concentration of Arc in the PSD fraction in preparations that underwent extinction compared to preparations that were pseudoconditioned for the same number of training sessions (Fig. 6B). Therefore, these findings support our immunocytochemical observations that Arc remains present in synapses after CR extinction.

Fig. 6.

Subcellular fractionation of brain stems demonstrates the synaptic presence of Arc after CR extinction. (A) Demonstration of the isolation of the PSD fraction. Immunoblotting for PSD-95 from homogenates (H), synaptosomal (S), and PSD fractions shows enhanced levels of crude postsynaptic membranes with minimal contamination from the presynaptic membrane as indicated by synaptophysin (Syn). (B) Immunoblotting of PSD fractions (n = 3/group) for Arc from preparations that underwent pseudoconditioning (Pseudo) or extinction (Extinction) for six sessions shows high levels of Arc in the PSD fraction after extinction.

4. Discussion

The primary findings of this study are that the synaptic localization of GluR4-containing AMPARs parallels the expression of CRs during acquisition, extinction, and reacquisition of conditioning consistent with the view that GluR4 subunits support the expression of abducens CRs. Moreover, Arc colocalizes with GluR4 subunits during these phases of conditioning, and once induced, remains present in synapses during these conditioning procedures. These data are consistent with the interpretation that GluR4 subunits are trafficked into and out of synapses during conditioning and may involve the IEG-inducible protein Arc.

4.1 Synaptic incorporation of GluR4-containing AMPARs during in vitro classical conditioning

Taken together, our evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that the synaptic incorporation of GluR4-containing AMPARs supports the acquisition and expression of in vitro CRs recorded from abducens motor neurons. Previous studies have demonstrated enhanced synthesis of GluR4 protein and increased localization of GluR4 subunits at synaptic sites corresponding with acquisition and expression of abducens CRs, but not with pseudoconditioning or treatment with the NMDAR antagonist AP-5 which blocks CRs (Keifer, 2001; Keifer & Clark, 2003; Mokin & Keifer, 2004; Mokin et al., 2006). In the present study, we have extended these findings to show that the synaptic localization of GluR4-containing AMPARs parallels the expression of abducens CRs during extinction and reacquisition of conditioning. That is, synaptically localized GluR4 subunits decline substantially during extinction when CRs are low and are reestablished during CR reacquisition. Our findings that GluR4 puncta decline after extinction (Fig. 2) while GluR4 protein remains high (Fig. 4) appears to be inconsistent. However, this result is explained by a subcellular shift of GluR4 subunits away from synaptic sites where synaptophysin puncta are best visualized (that is, one or two microns, or optical planes, lower than the focal plane for synaptophysin). Therefore, the decline in synaptic GluR4 during extinction does not appear to be from a reduction in protein synthesis but by movement of puncta away from the PSD. These data provide compelling evidence that the synaptic incorporation of GluR4-containing AMPARs supports CR expression during classical conditioning in this in vitro preparation. However, more direct evidence, such as from gene knockdown experiments, will be required to establish this conclusion. Similar to our results, a recent study of fear conditioning found that extinction was associated with reduced surface expression of GluR1 AMPAR subunits (Mao et al., 2006). Together, these findings indicate that the process of extinction is related to withdrawal of synaptically localized AMPARs.

Recent studies have begun to illuminate the signal transduction pathways that result in synaptic insertion of GluR4-containing AMPARs during in vitro conditioning. Pharmacological blockade of the MAPKs significantly attenuated both the acquisition and expression of abducens CRs (Keifer et al., 2007). Bath application of selective inhibitors of either the p38 or ERK MAPKs prior to conditioning blocked CR acquisition, whereas compounds applied after CRs had been obtained suppressed CR expression. Phosphorylation site-specific antibodies showed that ERK was activated during the early stage of conditioning during CR acquisition and declined while p38 was activated in the late stage of conditioning during CR expression. The attenuation of CRs by MAPK blockade was associated with a significant reduction in the synaptic localization of GluR4 subunits. These data suggest that the MAPK signaling pathways regulate postsynaptic trafficking of GluR4-containing AMPARs during in vitro conditioning. The synaptic insertion of GluR1 subunits was found to precede GluR4 early in conditioning (after pairing session 1) in order to activate silent synapses (Mokin, Zheng, & Keifer, 2007). These GluR1 subunits do not undergo protein synthesis and originate from an existing pool, possibly from extrasynaptic sources. The early delivery of GluR1 likely initiates signal transduction mechanisms involving NMDAR activation that allows for the synthesis and synaptic incorporation of GluR4 subunits that replace GluR1 leading to the acquisition of CRs. More recent studies indicate that the synaptic delivery of GluR4 subunits is mediated by the coordinated activity of both PKC and MEK-ERK MAPK signaling pathways (Zheng and Keifer, 2007). Consistent with these results, characterization of GluR4 subunits has revealed phosphorylation sites within the C-terminal domain of Ser 842 by CaMKII, PKA and PKC, Thr 830 by PKC in vitro, as well as phosphorylation in transfected cells of Ser 842 by PKA (Carvalho, Kameyama, & Huganir, 1999). Phosphorylation actively recruits the surface expression of GluR4-containing AMPARs in cell cultures (Gomes, Correia, Esteban, Duarte, & Carvalho, 2007; Gomes, Cunha, Nuriya, Faro, Huganir, Pires, Carvalho, & Duarte, 2004; Esteban, Shi, Wilson, Nuyriya, Huganir, & Malinow, 2003), possibly through interactions with the 4.1 family of proteins (Coleman, Mottershead, Haapalahti, & Keinanen, 2003), Arc (Mokin et al., 2006; see below), and the actin cytoskeleton.

4.2 Association of Arc with synaptic GluR4 AMPAR subunits during conditioning

Previously (Mokin et al., 2006), we showed that increased levels of the IEG-encoded protein Arc are expressed during CR acquisition. Protein localization and coimmunoprecipitation evidence showed that Arc is associated with GluR4 subunits during CR acquisition when AMPARs are delivered to synaptic sites. This process also involved interaction of Arc with the actin cytoskeleton. The present immunocytochemical findings confirm Arc colocalization with GluR4 subunits during CR acquisition and further show that Arc is colocalized with GluR4 during the early extinction and reacquisition phases of conditioning, all time periods when GluR4 trafficking is high. Similarly, coimmunoprecipitation data suggest that Arc interacts with GluR4 subunits during these phases of the conditioning protocol but not after CRs are fully extinguished. Therefore, Arc may be involved in the modulation of synaptic strength during these different training paradigms. Direct manipulation of Arc in this system will be required to fully establish its function in conditioning. In cultured neurons, expression of Arc appears to mediate the endocytosis of AMPARs (Rial Verde et al., 2006; Shepherd et al., 2006). Decreased activity-dependent AMPAR endocytosis in Arc knockout mice was interpreted to result in both enhanced early LTP and reduced LTD observed in hippocampal slices (Plath, Ohana, Dammermann, Errington, Schmitz, Gross, Mao, Engelsberg, Mahlke, Welzl et al., 2006). It is unclear whether regulation of endocytosis of AMPARs alone underlies acquisition and extinction during classical conditioning or whether acquisition and reacquisition involves active receptor insertion mechanisms. Evidence suggests that Arc does not bind to AMPARs directly (Chowdhury et al., 2006). Therefore, the function of Arc in synaptic modification may be determined predominantly by its binding partners within the PSD during specific plasticity states. Numerous proteins regulate the endocytosis and exocytosis of AMPARs including PICK1 and GRIP. However, the direct protein interactions of Arc are currently poorly characterized. Surprisingly, a recent study indicates that regulation of BDNF-induced Arc transcription depends on activity levels of AMPARs or NMDARs themselves (Rao, Pintchovshi, Chin, Peebles, Mitra, & Finkbeiner, 2006). In that study, AMPAR inhibitors resulted in increased Arc expression while NMDAR inhibitors decreased Arc expression, indicating a potential feedback pathway between synaptic levels of glutamate receptors and gene expression.

Interestingly, neither LTP nor LTD generated in Arc knockout mice is maintained, and late stages of spatial learning are impaired (Plath et al., 2006; see also Guzowski, Lyford, Stevenson, Houston, McGaugh, Worley, & Barnes, 2000). Moreover, sustained Arc synthesis may be required for maintanence of BDNF-induced LTP (Messaoudi, Kanhema, Soule, Tiron, Dagyte, de Silva, & Bramham, 2007). From such data, Arc has been interpreted to have a functional role in memory consolidation. We observed that Arc remains localized to synaptic sites throughout the conditioning procedures, including extinction. The immunocytochemical findings showed synaptic localization of Arc, but not GluR4 subunits, in cases that had undergone complete CR extinction. Protein synthesis for Arc also remained elevated. Significantly, and consistent with these observations, examination of the PSD fraction demonstrated a high concentration of Arc after extinction. Therefore, Arc may serve as a long-lasting synaptic tag for conditioning. A key issue in the learning literature is whether processes that underlie extinction are a reversal of mechanisms that generate acquisition or are a separate type of inhibitory learning (Mauk & Ohyama, 2004). A favored view in the field is that extinction is an inhibitory process that overlaps and suppresses the learned response because of the common observation of “savings”, in which relearning is faster than the original learning. The sustained presence of Arc protein at synaptic sites after extinction suggests that synapses do not return to their naïve state once the initial learning has taken place. The enduring synaptic localization of Arc and its trafficking function may facilitate relearning of responses once they have been established.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Frances Day for assistance with the confocal microscopy. Supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant NS051187 and National Institute of Research Resources grant P20 RR015567 which is designated as a Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) to J.K.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson CW, Keifer J. The cerebellum and red nucleus are not required for in vitro classical conditioning of the turtle abducens nerve response. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:9736–9745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09736.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CW, Keifer J. Properties of conditioned abducens nerve responses in a highly reduced in vitro brain stem preparation from the turtle. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;81:1242–1250. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.3.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AL, Kameyama K, Huganir RL. Characterization of phosphorylation sites on the glutamate receptor 4 subunit of the AMPA receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:4748–4754. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04748.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Shepherd JD, Okuno H, Lyford G, Petralia RS, Plath N, Kuhl D, Huganir RL, Worley PF. Arc/Arg3.1 interacts with the endocytic machinery to regulate AMPA receptor trafficking. Neuron. 2006;52:445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman SK, Cai C, Mottershead DG, Haapalahti J-P, Keinanen K. Surface expression of GluR-D AMPA receptor is dependent on an interaction between its C-terminal domain and a 4.1 protein. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:798–806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00798.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley PR, Heath JW, Harrison SM, Jarvie PE, Glenfield PJ, Rostas JA. A rapid Percoll gradient procedure for isolation of synaptosomes directly from an S1 fraction: homogeneity and morphology of subcellular fractions. Brain Research. 1988;441:59–71. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban JA, Shi S-H, Wilson C, Nuriya M, Huganir RL, Malinow R. PKA phosphorylation of AMPA receptor subunits controls synaptic trafficking underlying plasticity. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6:136–143. doi: 10.1038/nn997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes AR, Correia SS, Esteban JA, Duarte CB, Carvalho AL. PKC anchoring to GluR4 AMPA receptor subunit modulates PKC-driven receptor phosphorylation and surface expression. Traffic. 2007;8:259–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes AR, Cunha P, Nuriya M, Faro CJ, Huganir RL, Pires EV, Carvalho AL, Duarte CB. Metabotropic glutamate and dopamine receptors co-regulate AMPA receptor activity through PKA in cultured chick retinal neurones: effect on GluR4 phosphorylation and surface expression. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;90:673–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF. Insights into immediate-early gene function in hippocampal memory consolidation using antisense oligonucleotide and fluorescent imaging approaches. Hippocampus. 2002;12:86–104. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, Lyford GL, Stevenson GD, Houston FP, McGaugh JL, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Inhibition of activity-dependent Arc protein expression in the rat hippocampus impairs the maintenance of long-term potentiation and the consolidation of long-term memory. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:3993–4001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-03993.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keifer J. In vitro eye-blink reflex model: role of excitatory amino acids and labeling of network activity with sulforhodamine. Experimental Brain Research. 1993;97:239–253. doi: 10.1007/BF00228693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keifer J. In vitro eye-blink classical conditioning is NMDA receptor-dependent and involves redistribution of AMPA receptor subunit GluR4. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:2434–2441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02434.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keifer J. In vitro classical conditioning of the turtle eyeblink reflex: approaching cellular mechanisms of acquisition. Cerebellum. 2003;2:55–61. doi: 10.1080/14734220310015610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keifer J, Armstrong KE, Houk JC. In vitro classical conditioning of abducens nerve discharge in turtles. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:5036–5048. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05036.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keifer J, Clark TG. Abducens conditioning in in vitro turtle brain stem without cerebellum requires NMDA receptors and involves upregulation of GluR4-containing AMPA receptors. Experimental Brain Research. 2003;151:405–410. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1494-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keifer J, Zheng Z-Q, Zhu D. MAPK signaling pathways mediate AMPA receptor trafficking in an in vitro model of classical conditioning. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2007;97:2067–2074. doi: 10.1152/jn.01154.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Yeh SH, Lu HY, Gean PW. The similarities and diversities of signal pathways leading to consolidation of conditioning and consolidation of extinction of fear memory. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:8310–8317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-23-08310.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyford GL, Yamagata K, Kaufmann WE, Barnes CA, Sanders LK, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Lanahan AA, Worley PF. Arc, a growth factor and activity-regulated gene, encodes a novel cytoskeleton-associated protein that is enriched in neuronal dendrites. Neuron. 1995;14:433–445. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao SC, Hsiao YH, Gean PW. Extinction training in conjunction with a partial agonist of the glycine site on the NMDA receptor erases memory trace. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:8892–8899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0365-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, Chang C-H. Recent fear is resistant to extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 2006;103:18020–18025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608398103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauk MD, Ohyama T. Extinction as new learning versus unlearning: considerations from a computer simulation of the cerebellum. Learning and Memory. 2004;11:566–571. doi: 10.1101/lm.83504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaoudi E, Kanhema T, Soule J, Tiron A, Dagyte G, da Silva B, Bramham CR. Sustained Arc/Arg3.1 synthesis controls long-term potentiation consolidation through regulation of local actin polymerization in the dentate gyrus in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:10445–10455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2883-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokin M, Keifer J. Targeting of GluR4-containing AMPA receptors to synaptic sites during in vitro classical conditioning. Neuroscience. 2004;128:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokin M, Keifer J. Quantitative analysis of immunofluorescent punctate staining of synaptically localized proteins using confocal microscopy and stereology. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2006;157:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokin M, Lindahl JS, Keifer J. Immediate-early gene-encoded protein Arc is associated with synaptic delivery of GluR4-containing AMPA receptors during in vitro classical conditioning. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2006;95:215–224. doi: 10.1152/jn.00737.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokin M, Zheng Z, Keifer J. Conversion of silent synapses into the active pool by selective GluR1-3 and GluR4 AMPAR trafficking during in vitro classical conditioning. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2007;98:1278–1286. doi: 10.1152/jn.00212.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Davis M. Mechanisms of fear extinction. Molecular Psychiatry. 2007;12:120–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien R, Xu D, Mi R, Tang X, Hopf C, Worley P. Synaptically targeted Narp plays and essential role in the aggregation of AMPA receptors at excitatory synapses in cultured spinal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:4487–4498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04487.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plath N, Ohana O, Dammermann B, Errington ML, Schmitz D, Gross C, Mao X, Engelsberg A, Mahlke C, Welzl H. Arc/Arg3.1 is essential for the consolidation of synaptic plasticity and memories. Neuron. 2006;52:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.024. etc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VR, Pintchovshi SA, Chin J, Peebles CL, Mitra S, Finkbeiner S. AMPA receptors regulate transcription of the plasticity-related immediate-early gene Arc. Nature Neuroscience. 2006;9:887–895. doi: 10.1038/nn1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rial Verde EM, Lee-Osbourne J, Worley PF, Malinow R, Cline HT. Increased expression of the immediate-early gene Arc/Arg3.1 reduces AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission. Neuron. 2006;52:461–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpel S, LeDoux J, Zador A, Malinow R. Postsynaptic receptor trafficking underlying a form of associative learning. Science. 2005;308:83–88. doi: 10.1126/science.1103944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JD, Rumbaugh G, Wu J, Chowdhury S, Plath N, Kuhl D, Huganir RL, Worley PF. Arc/Arg3.1 mediates homeostatic synaptic scaling of AMPA receptors. Neuron. 2006;52:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Wallace CS, Lyford GL, Worley PF. Synaptic activation causes the mRNA for the IEG Arc to localize selectively near activated postsynaptic sites on dendrites. Neuron. 1998;21:741–751. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Worley PF. Selective targeting of newly synthesized Arc mRNA to active synapses requires NMDA receptor activation. Neuron. 2001;30:227–240. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW, Masushige S, Silva AJ, Kida S. Memory reconsolidation and extinction have distinct temporal and biochemical signatures. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:4787–4795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5491-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Keifer J. 2007 Abstract Viewer/Itenerary Planner. Society for Neuroscience; Washington, DC: PKC signaling pathways mediate AMPA receptor trafficking in an in vitro model of classical conditioning. (Prgrm No. 935.12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]