Abstract

Motivation: The computational identification of transcription factor binding sites is a major challenge in bioinformatics and an important complement to experimental approaches.

Results: We describe a novel, exact discriminative seeding DNA motif discovery algorithm designed for fast and reliable prediction of cis-regulatory elements in eukaryotic promoters. The algorithm is tested on biological benchmark data and shown to perform equally or better than other motif discovery tools. The algorithm is applied to the analysis of plant tissue-specific promoter sequences and successfully identifies key regulatory elements.

Availability: The Seeder Perl distribution includes four modules. It is available for download on the Comprehensive Perl Archive Network (CPAN) at http://www.cpan.org.

Contact: martina.stromvik@mcgill.ca

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

The binding of transcription factors to relatively short and variably degenerate regulatory DNA sequences (cis-regulatory elements) is central to the regulation of gene expression (Orphanides and Reinberg, 2002). While several sequenced genomes are nearly deciphered in terms of the protein-coding gene repertoire, the inventory and comprehensive characterization of cis-regulatory elements remains elusive.

Motif discovery has motivated the development of numerous tools and algorithms, and the use of various motif models and statistical approaches (Guha Thakurta, 2006). Motif discovery can be broadly divided into ‘sequence-driven’ and ‘pattern-driven’ methods. The former methods typically involve building a position-weight matrix (PWM) from sequence data, and local search techniques such as expectation–maximization or Gibbs sampling are used to optimize the log likelihood ratio until convergence or a maximum number of iterations is reached. Though routinely fast, those methods are not guaranteed to yield the best solution, or global optimum (Stormo, 2000). Enumerative methods, on the other hand, are guaranteed to find a global optimum but have the drawback of being computationally expensive and limited to short motifs.

Searching a set of sequences for patterns that are overrepresented relative to a given background model may converge towards motifs that are prevalent in the genome thus not likely to represent regulatory elements. Sinha (2003) introduced the notion of ‘discriminative’ motif discovery in which a motif is treated as a feature that leads to good classification between positive sequences deemed to contain common cis-regulatory elements and a set of background sequences.

In this work, we present the Seeder algorithm—a novel, exact discriminative seeding DNA motif discovery algorithm inspired by Keich and Pevzner, 2002; Pizzi et al., 2005. The major benefits of the Seeder algorithm are (i) the use of intuitive and reliable statistics for the choice of motif seeds and (ii) a data structure that significantly accelerate the computation of motifs and background models. The algorithm is benchmarked against popular motif finding tools and demonstrates greater performance. The algorithm is applied to the analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana seed-specific (the plant structure seed, not to be confused with motif seed) promoters and identifies motifs with high similarity to seed-specific cis-regulatory elements experimentally characterized in Brassica napus, a closely related species.

2 METHODS

2.1 The Seeder algorithm

Our algorithm starts by enumerating all nucleotide combinations (words) of a given length, usually six. For each word, it calculates the Hamming distance (HD) between the word and its best matching subsequence (we call this distance the substring minimal distance—SMD) in each sequence of a background set. This data is used to produce a word-specific background probability distribution for the SMD. For each word, it then calculates the sum of SMDs to sequences in a positive set. The P-value for this sum is calculated using the word-specific background probability distribution. The word for which the P-value is minimal is retained, and a seed PWM is built from the closest matches to this word found in every positive sequence. The seed PWM is extended to full motif width and sites maximizing the score to the extended PWM are selected, one in each positive sequence. A new PWM is built from those sites and the process is iterated until convergence, or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

2.1.1 Input data and parameters

Our algorithm takes as input a set B={B1, …, Bm} of m background sequences of length L, a set P={P1, …, Pn} of n positive sequences of length L, the length k of the motif seed and the length l of the full motif to discover.

2.1.2 Substring minimal distance

The HD between two strings of equal lengths is the number of positions at which symbols differ (Hamming, 1950). We define the SMD d(w,w′) between a short nucleotide sequence w and a longer sequence w′ as the minimal HD between w and a |w|-length substring of w′.

2.1.3 Background model

A discrete random variable Y(w) is associated with each word w of seed length k, corresponding to the SMD between w and a randomly selected background sequence from B. This w-specific distribution function is obtained empirically from B; for each word w, we set gw(y)=Pr[Y(w)=y]=|{Bi: d(w,Bi)=y}|/m, for y=0, …, k.

2.1.4 Seed position weigth matrix

For each word w, the sum of SMDs to the positive sequences S(w)=∑jd(w,Pj) is computed. Under the background model, the distribution function of this sum of n independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables is  , the n-fold self-convolution of gw(y) (Grinstead and Snell, 1997). The P-value (p) for word w with sum S(w), which is the probability of obtaining a sum lower or equal to S(w) under the assumption that Pj's are random in respect to w, is

, the n-fold self-convolution of gw(y) (Grinstead and Snell, 1997). The P-value (p) for word w with sum S(w), which is the probability of obtaining a sum lower or equal to S(w) under the assumption that Pj's are random in respect to w, is

| (1) |

The word w* for which the P-value p (S(w)) is minimal is retained. For each positive sequence in P, the set of one or more subsequences of length k having the SMD to w* are retained. A PWM P0 is built from this set of selected subsequences using standard procedures and pseudocounts proportional to  (Wasserman and Sandelin, 2004), with the modification that when a sequence contains more than one match, each match (subsequence) weight is reduced proportionally. The subsequence associated with the highest score to P0 is retained in each sequence, and the seed PWM Ps is built from this optimal set of n subsequences, as described above.

(Wasserman and Sandelin, 2004), with the modification that when a sequence contains more than one match, each match (subsequence) weight is reduced proportionally. The subsequence associated with the highest score to P0 is retained in each sequence, and the seed PWM Ps is built from this optimal set of n subsequences, as described above.

2.1.5 Full length motifs

The seed PWM Ps is of width k, smaller than the full motif width. It is extended to full motif width l by adding null weights at (l−k)/2 positions upstream and downstream. The full length PWM is then refined by iterating the following process. (i) Sites (one per sequence in P) maximizing the score to the extended weight matrix are selected and (ii) a revised full length PWM is built from those sites. This process is repeated until convergence (i.e. the sites maximizing the PWM score are fixed in all sequences) or for at most a default number of 10 iterations, which we observed to often be sufficient for the convergence of significant seeded motifs.

2.1.6 N-fold self-convolution

Our implementation of the n-fold self-convolution uses the binary expansion of n (Sundt and Dickson, 2000), and is an adaptation of the ‘square and multiply’ algorithm (Gordon, 1998) while convolutions per se are computed using the ‘input side algorithm’ (Smith, 1997).

2.1.7 Multiple hypothesis testing correction

For each motif predicted, a list of 4k P-values is generated thus prompting for a multiple testing correction. This is carried out by generating a list of q-values from the list of P-values associated with words of seed length k, using the general algorithm for estimating q-values described in (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003). The statistical significance of a motif is evaluated with the q-value of the sum S(w*), which is the expected proportion of false positives incurred when calling the sum significant (i.e. not likely to have occurred if the positive sequences were randomly selected).

2.1.8 Searching both strands

Because transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) can be located either on the forward or the reverse strand, motifs are typically searched for on both strands. This is easily achieved with Seeder: one simply redefines the SMD so as to consider matches one both strands (for both the background and positive sequences) and perform PWM matching similarly.

2.1.9 Multiple motifs

When the user asks to retrieve more than one motif, the sites identified in the preceding run(s) are masked and the motif-finding process is repeated. The positions of the sites are obtained by scanning each sequence (plus strand first) until the highest scoring subsequence is found.

2.2 Data structures

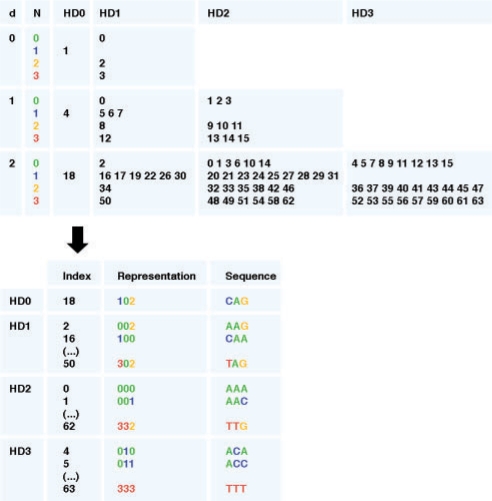

The calculation of SMDs using direct string comparison approaches requires a considerable amount of operations and this probably explains in part why this quantity has not been more often exploited for DNA motif discovery. We have designed a data structure based on the organization of the matrix of HDs between words of length 6 (see Fig. 4, supplied as supporting information). This structure, called the SMD index (Fig. 1), allows very efficient lookup, in a given sequence, for a subsequence minimally distant to a given word, hence improving the efficiency of the SMD computation.

Fig. 1.

SMD index generation. The SMD index generation is illustrated for the word ‘CAG’. N, top-level tree node nucleotide numerical value; d, level.

2.2.1 SMD index generation

Each nucleotide is mapped to a numerical value (A,C,G,T→0,1,2,3). For a given word w=w1, w2, …,wk of length k, a list of indices is generated equivalent to a tree structure with levels d=0, …, k−1. At each new level of the tree, each node is expanded into four nodes, one for each possible nucleotide N∈{0,1,2,3} at that position. An index id=N+(4 × id−1) is assigned to each new node, where id−1 is the index of the parent node. At the final level, the tree has nodes and indices corresponding to all possible nucleotide sequences of length k. For a given node at a given level d, the HD is one more than that of the parent, except for the node corresponding to nucleotide wd+1, where the HD is unchanged (Fig. 1). The SMD index is precomputed for every word w of seed length k and HDs between 0 and 3, which requires a marginal amount of memory and appreciably accelerates the process.

2.2.2 SMD calculation

The number of occurrences of every word of length k in each sequence in P is stored using base 4 indexing (word count array). The SMD between w and sequence Pj is obtained by looking up elements in word count array of Pj, in order of increasing HD to w, until a nonzero count is found.

2.3 Benchmarking of motif discovery tools

The performance of the Seeder algorithm was compared with that of popular motif discovery tools using benchmarks designed for robust assessment of motif discovery algorithms (Sandve et al., 2007). In the benchmark suites, binding site sequences from the Transfac® database (Wingender et al., 1996) are represented either in their original genomic context sequences (‘Model Real’—MR, ‘Algorithm Real’—AR) or in sequences generated with a third-order Markov model (MM) (‘Algorithm Markov’—AM). The reverse complement of sequences is used in cases where the original binding site appears on the negative strand, so all sites within the benchmark suites appear in the forward sequence. The MR suite contains motifs that, according to Sandve et al. (2007), are harder to distinguish from the local background using common motif models (consensus, PWM and mismatch). The AM and AR suites each contain 50 datasets and a total of 810 sequences of mean length ∼1300 nucleotides, and the MR suite contains 25 datasets and a total of 410 sequences of mean length ∼1250 nucleotides.

2.3.1 Parameter settings

In order to be representative of common usage where parameter adjustment is nominal while providing homogeneous instructions to different software, sequences were scanned in the forward orientation, searching for one motif of width 12 with one occurrence (site) per sequence. Other parameters were left to default values. We ran Seeder v. 0.01 (this article), Weeder v. 1.3.1 (Pavesi et al., 2004), BioProspector v. 1 (Liu et al., 2001), MEME v. 3.5.4 (Bailey and Elkan, 1994), the Gibbs Motif Sampler v. 3.03.003 (Lawrence et al., 1993) and Motif Sampler v. 3.2 (Thijs et al., 2001) on each dataset. The DIPS algorithm (Sinha, 2006) was not included in the benchmark study because it was associated with prohibitive runtime requirements under our computational conditions. Background models were generated separately for each suite using all sequences within the suite. Background distributions for words of length 6 were generated using the Seeder::Background module. Frequency files (expected values for 6-mers and 8-mers) used by Weeder were generated using a custom Perl script. A sixth-order MM was generated for MEME using a custom Perl script, and for Motif Sampler using the INCLUSive CreateBackgroundModel program (Thijs et al., 2002). The default (third-order) MM was generated for BioProspector using the genomebg program provided with the software.

2.3.2 Evaluation of motifs versus known binding sites

The predictions were evaluated using the suite of tools described in (Sandve et al., 2007) (http://tare.medisin.ntnu.no). The predictions were scored using the nucleotide-level Pearsons correlation coefficient (nCC) (Tompa et al., 2005). Differences between scores were assessed using paired t-tests (α=0.05).

2.4 Motif discovery in the promoters of Arabidopsis seed-specific genes

A background set of 22 032 nuclear protein-coding gene promoters (500 bp upstream of the transcription start site) was generated using the TAIR (release 7) ‘loci upstream sequences’ dataset (sequences preceding the 5′ end of each transcription unit) and the ‘protein-coding with transcript support’ listing (loci with supporting cDNA or ESTs deposited in Genbank), downloaded from the TAIR ftp server (ftp://ftp.arabidopsis.org). Tissue-specific promoter sequence sets were assembled according to marker gene data from Schmid et al. (2005). The Seeder algorithm was used to perform motif prediction in seed-specific promoters using a seed length of six and a motif length of 12, and the ‘protein-coding with transcript support’ gene promoters as a background.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Performance of motif discovery tools

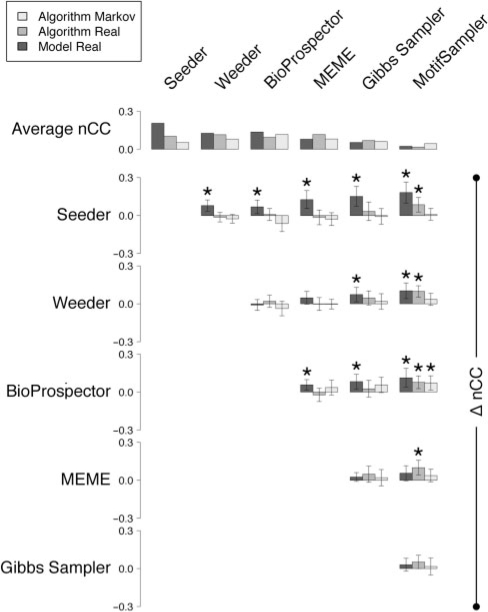

Figure 2 shows the differences between scores of different motif discovery tools on the benchmark suites of Sandve et al. (2007). On the AM suite, the performance of each tool was statistically equivalent. Interestingly, the tool that performed the best (though by a nonsignificant margin), BioProspector, models background sequences using a third-order MM, the same type as that used by Sandve et al. (2007) to generate the AM background sequences. Seeder, BioProspector, Weeder, MEME and the Gibbs Sampler scored equally on the AR suite, which contains binding sites in their original sequence. The MR suite also contains binding sites in their original sequence, but in this case the binding sites have a composition that is more similar to that of the surrounding background sequence. This suite was assembled for the purpose of testing novel motif models (Sandve et al., 2007). Seeder scored significantly higher on the MR suite than any other algorithm tested.

Fig. 2.

Average benchmarking scores and pairwise differences between motif discovery tools. Average nucleotide-level Pearson correlation coefficient (nCC) and pairwise differences (Δ nCC) for six motif discovery tools tested on three benchmark suites. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals. Stars indicate significant differences (α=0.05) between scores.

At first glance, it may seem surprising that the performance of some tools is actually higher on the MR suite than on AR suite. However, although the similarity of motifs to their local background does complicate the task of motif-finding approaches using local background models, this does not overly affect those based on global background models. It nonetheless appears that our discriminative approach to seed selection yields a nonnegligible advantage to Seeder. Having said that, it should be noted that for a number of individual datasets the scores obtained by other tools are higher than that of Seeder, which highlights the complementary of these programs.

3.2 Arabidopsis seed-specific motifs

The Seeder algorithm was used to discover motifs (on both strands) in a set of 57 promoter sequences of A. thaliana seed-specific marker genes identified by expression data analysis (Schmid et al., 2005). The computation of the background distributions (motif seed length of 6) took 35 min using a single Intel® ×86 processor, and motif computation took ∼3.5 min per motif reported. This example shows that most of the computing time is used to compute the background model, particularly when using genome-scale background datasets. The Seeder::Background module was therefore designed to precompute background models which can be reused for any number of motif finding operations.

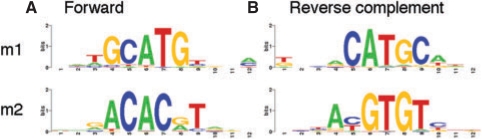

The top two predictions (q-value <0.01) were compared to known plant motifs in the PLACE database (Higo et al., 1998) using the STAMP web server (Mahony and Benos, 2007). The first motif (Fig. 3, m1) (q-value=4.4 × 10−9, information content=7.4) and the second motif (Fig. 3, m2) (q-value=1.1 × 10−3, information content=7.6) are similar to two experimentally characterized cis-regulatory elements found in the napA promoter in B. napus, the RY repeat (CATGCA) (E=6.32 × 10−8) and the G-box (CACGTG) (E=2.92 × 10−5) (Ezcurra et al., 1999). The function of these regulatory elements was shown by substitution mutation analysis using promoter–reporter gene fusions, leading to a strong reduction of the napA promoter activity in seeds (Ezcurra et al., 1999). The second motif is also highly similar to a sequence (ACGTGTC) (E=4.70 × 10−11) overrepresented in the promoters of A. thaliana genes downregulated during seed germination (Ogawa et al., 2003).

Fig. 3.

Arabidopsis seed-specific motifs. Sequence logos of motifs overrepresented in the promoters of A. thaliana seed-specific marker genes. (A) Full-length forward motifs. (B) Reverse complement of motifs.

4 CONCLUSION

We have described a novel algorithm for DNA motif discovery and demonstrated its capacity to discover motifs in real biological datasets. Advantages of the algorithm over other approaches include (i) the enumerative-guaranteed optimality of seed selection; (ii) a background model based on empirical distribution of SMDs; and (iii) efficient data structures that make background and motif computations relatively fast at moderate seed lengths.

We have benchmarked the algorithm against popular motif finding tools and demonstrated its performance to be equal or better than that of other tools on biological datasets. We note however that, although the Sandve et al. (2007) benchmarks proved extremely useful for our performance analysis, it would be ideal to have suites designed specifically for discriminative motif-finding algorithms.

Tompa et al. (2005) recommend biologists to use a few complementary tools, and to consider the top few predicted motifs of each tool. Based on the benchmarks results presented in this study, we recommend the inclusion of Seeder in the biologist's DNA motif discovery toolbox.

The present implementation of Seeder allows for motif searches in the mode ‘one occurrence per sequence’ (oops). This assumption is deeply engrained in the algorithm and statistics for the selection of the motif seed and the construction of the seed PWM. Of course, once a good seed PWM has been selected, other search modes [e.g. ‘zero-or-one occurrence per sequence’ (zoops) or ‘any-number of repetitions’ (anr)] could be implemented using the type of frameworks previously implemented in tools like MEME or BioProspector.

We have applied the algorithm to the analysis of A. thaliana seed-specific promoters and found that the top two motifs were similar to experimentally characterized cis-regulatory elements found in the promoters of B. napus seed-storage protein genes. This was unanticipated, considering the array of gene families and functions found in the seed-specific gene set from (Schmid et al., 2005).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank G.K. Sandve (Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway) for helpful comments, and the Perl Monks (http://perlmonks.org) for support in the development of the Perl modules. We also thank the reviewers for their constructive comments. We also acknowledge support from Fonds québécois de recherche sur la nature et les technologies (FQRNT) and Centre SÈVE.

Funding: Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant No. 283303 (to M.V.S.); NSERC Postgraduate Scholarship (PGS D) (to F.F.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezcurra I, et al. Interaction between composite elements in the napA promoter: both the B-box ABA-responsive complex and the RY/G complex are necessary for seed-specific expression. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999;40:699–709. doi: 10.1023/a:1006206124512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DM. A survey of fast exponentiation methods. J. Algorithms. 1998;27:129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Grinstead CM, Snell JL. Introduction to Probability. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society; 1997. Sums of random variables; pp. 285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Guha Thakurta D. Computational identification of transcriptional regulatory elements in DNA sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3585–3598. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamming RW. Error detecting and error correcting codes. BLTJ. 1950;29:147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Higo K, et al. PLACE: a database of plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:358–359. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keich U, Pevzner PA. Finding motifs in the twilight zone. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1374–1381. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.10.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CE, et al. Detecting subtle sequence signals: a Gibbs sampling strategy for multiple alignment. Science. 1993;262:208–214. doi: 10.1126/science.8211139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, et al. BioProspector: discovering conserved DNA motifs in upstream regulatory regions of co-expressed genes. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2001;6:127–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony S, Benos PV. STAMP: a web tool for exploring DNA-binding motif similarities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W253–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, et al. Gibberellin biosynthesis and response during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1591–1604. doi: 10.1105/tpc.011650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orphanides G, Reinberg D. A unified theory of gene expression. Cell. 2002;108:439–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavesi G, et al. Weeder web: discovery of transcription factor binding sites in a set of sequences from co-regulated genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W199–W203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi C, et al. Detecting seeded motifs in DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e135. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandve GK, et al. Improved benchmarks for computational motif discovery. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:193. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, et al. A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:501–506. doi: 10.1038/ng1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S. Discriminative motifs. J. Comput. Biol. 2003;10:599–615. doi: 10.1089/10665270360688219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S. On counting position weight matrix matches in a sequence, with application to discriminative motif finding. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:e454–e463. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SW. The Scientist and Engineer's Guide to Digital Signal Processing. San Diego, CA: California Technical Publishing; 1997. Convolution; pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormo GD. DNA binding sites: representation and discovery. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:16–23. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundt B, Dickson D.CM. Comparison of methods for evaluation of the n-fold convolution of an arithmetic distribution. Bull. Assoc. Swiss Actuaries. 2000:129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Thijs G, et al. A higher-order background model improves the detection of promoter regulatory elements by Gibbs sampling. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1113–1122. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thijs G, et al. INCLUSive: integrated clustering, upstream sequence retrieval and motif sampling. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:331–332. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa M, et al. Assessing computational tools for the discovery of transcription factor binding sites. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:137–144. doi: 10.1038/nbt1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman WW, Sandelin A. Applied bioinformatics for the identification of regulatory elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:276–287. doi: 10.1038/nrg1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingender E, et al. TRANSFAC: a database on transcription factors and their DNA binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:238–241. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.