Abstract

Increased  and NO

production is a key mechanism of mitochondrial dysfunction in myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury. A crucial segment of the mitochondrial electron

transport chain is succinate ubiquinone reductase (SQR or Complex II). In SQR,

oxidative impairment and deglutathionylation of the 70-kDa flavin protein

occurs in the post-ischemic heart (Chen, Y. R., Chen, C. L.,

Pfeiffer, D. R., and Zweier, J. L. (2007) J. Biol.

Chem.

282,32640

-32654). To gain insights into

the oxidative modification of the 70-kDa protein in the post-ischemic

myocardium, we used the identified S-glutathionylated peptide

(77AAFGLSEAGFNTACVTK93) of the 70-kDa protein

as a chimeric epitope incorporating a “promiscuous” T cell epitope

to generate a high titer polyclonal antibody, AbGSC90. Purified AbGSC90 showed

a high binding affinity to isolated SQR. Antibodies of AbGSC90 moderately

inhibited the electron transfer and superoxide generation activities of SQR.

To test for protein nitration, rats were subjected to 30 min of coronary

ligation followed by 24 h of reperfusion. Tissue homogenates were

immunoprecipitated with AbGSC90 and probed with antibodies against

3-nitrotyrosine. Enhancement of protein tyrosine nitration was detected in the

post-ischemic myocardium. Isolated SQR was subjected to in vitro

protein nitration with peroxynitrite, leading to site-specific nitration at

the 70-kDa polypeptide and impairment of SQR electron transfer activity.

Protein nitration of SQR further impaired its protein-protein interaction with

Complex III. Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry analysis indicated

that Tyr-56 and Tyr-142 were involved in protein tyrosine nitration. When the

isolated SQR was subjected to in vitro S-glutathionylation, oxidative

modification and impairment mediated by peroxynitrite were significantly

decreased, thus confirming the protective effect of

S-glutathionylation from the oxidative damage of nitration.

and NO

production is a key mechanism of mitochondrial dysfunction in myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury. A crucial segment of the mitochondrial electron

transport chain is succinate ubiquinone reductase (SQR or Complex II). In SQR,

oxidative impairment and deglutathionylation of the 70-kDa flavin protein

occurs in the post-ischemic heart (Chen, Y. R., Chen, C. L.,

Pfeiffer, D. R., and Zweier, J. L. (2007) J. Biol.

Chem.

282,32640

-32654). To gain insights into

the oxidative modification of the 70-kDa protein in the post-ischemic

myocardium, we used the identified S-glutathionylated peptide

(77AAFGLSEAGFNTACVTK93) of the 70-kDa protein

as a chimeric epitope incorporating a “promiscuous” T cell epitope

to generate a high titer polyclonal antibody, AbGSC90. Purified AbGSC90 showed

a high binding affinity to isolated SQR. Antibodies of AbGSC90 moderately

inhibited the electron transfer and superoxide generation activities of SQR.

To test for protein nitration, rats were subjected to 30 min of coronary

ligation followed by 24 h of reperfusion. Tissue homogenates were

immunoprecipitated with AbGSC90 and probed with antibodies against

3-nitrotyrosine. Enhancement of protein tyrosine nitration was detected in the

post-ischemic myocardium. Isolated SQR was subjected to in vitro

protein nitration with peroxynitrite, leading to site-specific nitration at

the 70-kDa polypeptide and impairment of SQR electron transfer activity.

Protein nitration of SQR further impaired its protein-protein interaction with

Complex III. Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry analysis indicated

that Tyr-56 and Tyr-142 were involved in protein tyrosine nitration. When the

isolated SQR was subjected to in vitro S-glutathionylation, oxidative

modification and impairment mediated by peroxynitrite were significantly

decreased, thus confirming the protective effect of

S-glutathionylation from the oxidative damage of nitration.

Mitochondrial dysfunction in ischemia-reperfusion injury is caused by

oxidative stress

(1-7).

In the ischemic myocardium oxygen delivery to the myocyte is not sufficient to

meet the need for mitochondrial oxidation during the physiological conditions

of hypoxia, leaving the mitochondrial electron transport chain in a highly

reductive state. This results in increased electron leakage from the electron

transport chain that in turn reacts with residual molecular oxygen to give

superoxide ( )

(8,

9). Because of the lack of ADP,

re-introduction of oxygen with reperfusion will greatly increase electron

leakage along with a decrease in scavenging capacity, leading to

)

(8,

9). Because of the lack of ADP,

re-introduction of oxygen with reperfusion will greatly increase electron

leakage along with a decrease in scavenging capacity, leading to

and

and

-derived oxidants being

overproduced in mitochondria. Specifically, an increased hyperoxygenation

induced by reperfusion in the post-ischemic heart has been detected by in

vivo EPR oximetry

(10-12).

The overproduction of reactive oxygen species

(ROS)2 also initiates

oxidative impairment of Complex II (or succinate-ubiquinone reductase (SQR))

as reported previously (7).

-derived oxidants being

overproduced in mitochondria. Specifically, an increased hyperoxygenation

induced by reperfusion in the post-ischemic heart has been detected by in

vivo EPR oximetry

(10-12).

The overproduction of reactive oxygen species

(ROS)2 also initiates

oxidative impairment of Complex II (or succinate-ubiquinone reductase (SQR))

as reported previously (7).

Myocardial ischemia provides a stimulus to alter NO metabolism

(13-17).

Increased NO production and subsequent peroxynitrite (OONO-)

formation have been detected in the postischemic heart

(10,

11,

14,

15). Alterations in the

generation of NO occurring in hearts subjected to ischemia/reperfusion have

been linked to NO synthase (NOS)-dependent

(10,

11,

14,

15) and NOS-independent

(18,

19) pathways, including

involvement of endothelial NOS (eNOS), increased nitrite disproportionation,

and increased expression of inducible NO synthase (iNOS) in chronic

reperfusion injury (11).

Therefore, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion indirectly changes the balance

between NO and ROS (especially

) in mitochondria. It has

been documented that OONO--mediated nitration of mitochondrial

proteins can be detected in the endothelial cells after ischemia/reperfusion

under flowing conditions

(20).

) in mitochondria. It has

been documented that OONO--mediated nitration of mitochondrial

proteins can be detected in the endothelial cells after ischemia/reperfusion

under flowing conditions

(20).

Mitochondrial Complex II (EC 1.3.5.1. succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) is a key membrane complex in the tricarboxylic acid cycle that catalyzes the oxidation of succinate to fumarate in the mitochondrial matrix (21). Succinate oxidation is coupled to reduction of ubiquinone at the mitochondrial inner membrane as one part of the respiratory electron transport chain. SQR mediates electron transfer from succinate to ubiquinone through the prosthetic groups of flavin adenine nucleotide (FAD), [2Fe-2S] (S1), [4Fe-4S] (S2), and [3Fe-4S] (S3) and heme b. The enzyme is composed of two parts, a soluble succinate dehydrogenase and a membrane-anchoring protein fraction. Succinate dehydrogenase contains two protein subunits, a 70-kDa protein with a covalently bound FAD, and a 27-kDa iron-sulfur protein hosting S1, S2, and S3 iron-sulfur clusters (21). The membrane-anchoring protein fraction contains cytochrome b hosting two hydrophobic polypeptides (CybL/14 kDa and CybS/9 kDa) with heme b binding (22).

In previous studies we have demonstrated that oxidative impairment

(∼42% reduction of thenoyltrifluoroacetone-sensitive electron transfer

activity) of mitochondrial Complex II was detected in the post-ischemic heart

from in vivo regional ischemia-reperfusion models

(7). A decrease in the redox

modification of protein S-glutathionylation was marked at the 70-Da

FAD binding subunit. In vitro studies indicated that removal of

S-glutathionylated (GS) binding from the specific cysteine residue(s)

of Complex II moderately increased enzyme-mediated

production and decreased

electron transfer efficiency. Therefore, oxidative post-translational

modification of the SQR 70-kDa subunit is logically hypothesized to follow

deglutathionylation of the SQR 70-kDa subunit. The molecular events regarding

oxidative post-translational modification of the flavin protein in Complex II

after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion are not clear and remain to be defined.

Furthermore, in vitro studies have also identified a tryptic peptide,

AAFGLSEAGFNTACVTK (aa 77-93), which is involved in

S-glutathionylation (or GS binding)

(7). Whether the identified GS

binding domain is essential for the enzymatic function of SQR remains to be

determined.

production and decreased

electron transfer efficiency. Therefore, oxidative post-translational

modification of the SQR 70-kDa subunit is logically hypothesized to follow

deglutathionylation of the SQR 70-kDa subunit. The molecular events regarding

oxidative post-translational modification of the flavin protein in Complex II

after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion are not clear and remain to be defined.

Furthermore, in vitro studies have also identified a tryptic peptide,

AAFGLSEAGFNTACVTK (aa 77-93), which is involved in

S-glutathionylation (or GS binding)

(7). Whether the identified GS

binding domain is essential for the enzymatic function of SQR remains to be

determined.

This study was undertaken to address the fundamental questions regarding the redox biochemistry of Complex II and its molecular mechanism of oxidative post-translational modification implicated in the post-ischemic myocardium. We have employed immunochemistry to define the functional role of the GS binding domain in SQR. Furthermore, we detected an increase in protein tyrosine nitration associated with the FAD binding subunit of Complex II in the post-ischemic heart in vivo. In in vitro studies using isolated SQR from the myocardial tissue, we have characterized the specific tyrosyl residues involved in detected protein nitration mediated by OONO- in the 70-kDa subunit in nitrated SQR.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Ammonium acetate, ammonium sulfate, diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid, ubiquinone-2 (Q2), sodium cholate, deoxycholic acid, sodium dithionite, Triton X-100, 2,6-dichloroindophenol (sodium hydrate salt), acetylated cytochrome c (horse heart), Zn/Cu superoxide dismutase (SOD), and sodium succinate were purchased from Sigma. OONO- was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). The 5-diethoxylphosphoryl-5-methyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DEPMPO) spin trap was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA).

Peptide Synthesis and Purification

Peptide synthesis was performed on a Milligen/Biosearch 9600 solid-phase peptide synthesizer (Bedford, MA) using Fmoc/t-butyl chemistry. Preloaded Fmoc-amino acids on CLEAR ACID resin (0.36 meq/g) (Peptides International, Louisville, KY) were used for the peptide synthesis with the PyBop/HoBt coupling method. The B-cell epitope was assembled by choosing regioselective side chain protection on Cys residues as Cys (Trt) or cys (Acm) essentially as described by Kaumaya et al. (23, 24). The B-cell epitope was synthesized co-linearly with a promiscuous T-helper epitope (MVF) derived from the measles virus fusion protein (amino acids 288-305). Also, an MVF T-helper epitope with a four-residue linker (GPSL) was incorporated for independent folding and was assembled on the B-cell epitope. All peptides were cleaved from the resin using global deprotection reagent B (trifluoroacetic acid:phenol: water:triisopropylsilane, 90:4:4:2). The protecting group from Cys (Trt) comes off in the global cleavage reaction. Crude peptides were purified on preparative reverse phase HPLC using a C-4 Vydac column in a water (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid), acetonitrile (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) gradient system. Pure fractions were analyzed using analytical HPLC, pooled together, and lyophilized in a 10% acetic acid solution. The purified peptide was hydrolyzed dry and kept at -20 °C to prevent oxidation of free sulfhydryl groups of Cys residues.

Peptide Immunization and Antibody Purification

Two New Zealand White rabbits (6-8 weeks old, female outbreed) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and immunized with an MVFGSC90 chimeric peptide (1 mg) dissolved in H2O (500 μl) with 100 mg of a muramyl dipeptide adjuvant, nor-MDP (N-acetylglucosamine-3-yl-acetyl-l-alanyl-d-isoglutamine). Peptides were emulsified (50:50) in a Montanide ISA 720 vehicle (Seppic). Two ml of blood were drawn for pre-immunization sera. All rabbits were immunized subcutaneously at four spots on the back. After the first immunization the same dose was administered three more times as booster injections 3, 6, and 9 weeks later. Sera were collected by bleeding from the ear of the rabbit after each immunization for determination of antibody titers. Antibody titers were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

High titer sera were purified on a protein A/G-agarose column (Pierce). Eluted antibodies were concentrated and exchanged in phosphate-buffered saline using 100-kDa cut-off centrifuge filter units (Millipore, Bedford, MA).

In Vivo Myocardial Regional Ischemia-Reperfusion Model

The procedure for the in vivo ischemia-reperfusion rat model was performed by the technique reported in the literature (10, 25). Sprague-Dawley rats (∼300-350 g) were anesthetized with Nembutal administered intraperitoneally (80-100 mg/kg). After the rats were fully anesthetized, they were intubated and then ventilated with room air (1.0 ml, rate of 100 breaths/min) using a mechanical ventilator Model 683 (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). The rats then underwent a left lateral thoracotomy, the pericardium was opened, and a pericardial cradle formed to allow adequate exposure of the heart surface. The left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was then occluded by placing a suture (6.0 nylon) around the origin of the LAD.

After 30 min of ischemia, the suture around the coronary artery was untied, allowing reperfusion to occur. Following the reperfusion, all wounds were closed and infiltrated with 0.5% xylocaine (<0.3 ml). The muscular layers and skin incisions were closed with 4.0 nylon sutures. A chest tube (2.5 cm PE 50 tubing) was inserted at the wound site and maintained in position, whereas the animal was taken off respiratory support.

Upon spontaneous breathing, the chest tube was removed, and a surgical clip was applied over the withdrawal site. The animal was allowed to recover, and a physiological assessment was performed. During the recovery period the animals received supportive post-operative care as needed. Body temperature was maintained at 37 °C by a thermal heating pad. By 6 h post-operation the animals had recovered sufficiently to eat and drink independently.

At 24 h post-infarction the rats were placed under deep anesthesia with Nembutal (200 mg/ml). The left anterior descending coronary artery was reoccluded, and Evans blue (4%) was injected from the inferior vena cava to delineate the non-ischemic myocardial tissue. Rats were then sacrificed, and the hearts were excised and placed in phosphate-buffered saline buffer. The infarct area was identified by 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining. The risk region of myocardial tissue without 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining was excised and subjected to biochemical analysis.

Cell Culture and Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy

Rat cardiac myoblasts (H9c2 cell line from ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic in 35-mm polystyrene tissue culture dishes at 37 °C in the presence of 4.5% CO2. Confluent cells with >90% viability were used to conduct immunoblotting.

Cardiac myoblasts were placed on sterile coverslips (Harvard Apparatus, 22 mm2) in 35-mm sterile dishes at a density of 104 cells/dish and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2, 95% air mix before hypoxia/reoxygenation treatment. Cells were plated in a Modular Incubator Chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, Inc., Del Mar, CA). Hypoxic treatment was accomplished by flushing nitrogen gas on the surface of the glucose-free medium and incubating for 1 h, after which reoxygenation was carried out by incubating in medium with glucose for 1 h. At the end of the experiment, cells attached to coverslips were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 containing 0.01% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline (TTBS) for 5 min, then blocked for 30 min with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 0.01% TTBS and incubated with AbGCS90 (1:2000) for visualization of the SQR 70-kDa subunit and the anti-3-nitrotyrosine monoclonal antibody (1:1000, Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Lake Placid, NY) in 0.01% TTBS containing 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. After treatment of cells with the chosen primary antibodies, they were incubated with secondary anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 488-conjugated and secondary anti-mouse AlexaFluor 568-conjugated antibodies (1:1000) for 1 h at room temperature. The coverslips with cells were then mounted on a glass slide with the antifade mounting medium, Fluoromount-G, viewed with confocal fluorescence microscopy (LSM 510; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a 60× objective, and overlaid with LSM Image Brower software, generating a merged image for each co-stained specimen.

Preparations of Mitochondrial Succinate-Cytochrome c Reductase (SCR) and SQR

Bovine heart mitochondrial SCR was prepared and assayed according to the published method developed by Yu and Yu (26). The purified SCR contained ∼4-4.2 nmol of heme b per mg of protein and exhibited an activity of ∼8.5 μmol of cytochrome c reduced/min/mg of protein. Purified SCR was stored in 50 mm sodium/potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.25 m sucrose and 1 mm EDTA.

SQR and QCR were isolated from SCR by calcium phosphate-cellulose chromatography under non-reducing conditions according to the published method developed by Yu et al. (26, 27). SQR-containing fractions obtained from the second calcium phosphate-cellulose column were concentrated by 43% ammonium sulfate saturation and centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 20 min (27). The precipitate obtained was dissolved in 50 mm sodium/potassium phosphate, pH 7.8, containing 0.2% sodium cholate and 10% glycerol. The specific activity of the purified SQR was ∼15.2 μmol of succinate oxidized (or dichlorophenol indophenol (DCPIP) reduced/min/mg of protein).

Analytical Methods

Optical spectra were measured on a Shimadzu 2401 UV-visible recording spectrophotometer. The protein concentration of rat heart tissue homogenates was determined by the Lowry method using bovine serum albumin as a standard. The heme b concentration of SQR was calculated from the differential spectrum between dithionite reduction and ferricyanide oxidation using an extinction coefficient of 28.5 mm-1cm-1 for the absorbance difference of A560 nm-A576 nm. The concentration of Q2 was determined by absorbance spectra from NaBH4 reduction using a millimolar extinction coefficient ε(275 nm—290 nm) of 12.25 mm-1cm-1 (28). The enzyme activity of SQR was assayed by measuring Q2-stimulated DCPIP reduction by succinate as described in the literature (27).

To measure the electron transfer activity of SQR, an appropriate amount of

SQR was added to an assay mixture (1 ml) containing 50 mm phosphate

buffer, pH 7.4, 0.1 mm EDTA, 75 μm DCPIP, 50

μm Q2, and 20 mm succinate as developed by

Hatefi (29). The SQR activity

was determined by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 600 nm. The specific

activity of SQR (nmol of DCPIP reduced (or succinate oxidized)/min/mg of SQR)

was calculated using a molar extinction coefficient ε600 nm of

21 mm-1 cm-1. SQR-mediated

generation was assayed by

an acetylated cytochrome c reduction. The reaction mixture contained

acetylated cytochrome c (50 μm), succinate (2

mm), and diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (1 mm) in 50

mm sodium/potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The kinetics of

acetylated cytochrome c reduction was initiated by SQR (5 pmol, based

on heme b), and the absorption increase at 550 nm was monitored at

room temperature.

generation was assayed by

an acetylated cytochrome c reduction. The reaction mixture contained

acetylated cytochrome c (50 μm), succinate (2

mm), and diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (1 mm) in 50

mm sodium/potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The kinetics of

acetylated cytochrome c reduction was initiated by SQR (5 pmol, based

on heme b), and the absorption increase at 550 nm was monitored at

room temperature.

-mediated acetylated

cytochrome c reduction was measured by pre-addition of Cu,Zn-SOD

(0.67 unit/μl) in the same assay mixture.

-mediated acetylated

cytochrome c reduction was measured by pre-addition of Cu,Zn-SOD

(0.67 unit/μl) in the same assay mixture.

Immunoblotting Analysis

The reaction mixture was mixed with the Laemmli sample buffer at a ratio of 4:1 (v/v), incubated at 70 °C for 10 min, and then immediately loaded onto a 4-20% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gradient gel. Samples were run at room temperature for 2 h at 100 V. Protein bands were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes in 25 mm Tris, 192 mm glycine, and 10% methanol. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TTBS) and 5% dry milk (Bio-Rad). The blots were then incubated overnight with anti-3-nitrotyrosine polyclonal antibody (1:2000, Upstate) or AbGSC90 (1:50,000, 0.22 μg/ml) at 4 °C. Blots were then washed 3 times in TTBS and incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG in TTBS at room temperature The blots were again washed twice in TTBS and twice in TBS and then visualized using ECL Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences).

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Measurements

EPR measurements were performed on a Bruker EMX spectrometer operating at 9.86 GHz with 100 kHz modulation frequency at room temperature. The reaction mixture was transferred to a 50-μl capillary, which was then positioned in the HS cavity (Bruker Instrument, Billerica, MA). The sample was scanned using the following parameters: center field, 3510 G; sweep width, 140 G; power, 20 milliwatts; receiver gain, 2 × 105; modulation amplitude, 1 G; time of conversion, 163.84 ms; time constant, 163.84 ms. The spectral simulations were performed using the WinSim program developed at NIEHS by Duling (30). The hyperfine coupling constants used to simulate the spin adduct of DEPMPO/.OOH were isomer 1: aN = 13.14 G, aHβ = 11.04 gauss, aHγ = 0.96 G, ap = 49.96 G; isomer 2: aN = 13.18 G, aHβ = 12.59 gauss, aHγ = 3.46 G, ap = 48.2 G; DEPMPO/.OH, aN = 14.03 gauss, aHβ = 13.34 G, ap = 47.19 G (28, 31).

Mass Spectrometry

The sample of nitrated SQR was prepared by incubating isolated SQR (1 μm based on heme b) with OONO- (100 μm) at room temperature for 1 h. The obtained nitrated SQR (50 pmol) was subjected to SDS-PAGE in the presence of β-mercaptoethanol using 4-12% gradient Bis-tris polyacrylamide gel. Protein bands on the gel were stained with Coomassie Blue for 1 h, and the staining background was rapidly removed by methanol/acetic acid/water (40:10:50). The gel was then equilibrated with distilled water at 4 °C overnight before in-gel digestion and MS measurement.

In-gel Digestion—Gels were digested with sequencing grade trypsin (Promega, Madison WI) and chymotrypsin (Roche Diagnostics) using the Montage In-Gel Digestion kit from Millipore following the manufacturer's recommended protocols with minor changes for optimization of peptide extraction. Briefly, the bands of interest were trimmed as closely as possible to minimize background polyacrylamide material. After being washed twice in 50% methanol, 5% acetic acid for several hours, the gel bands were dehydrated with acetonitrile and washed again with cycles of acetonitrile and 100 mm ammonium bicarbonate buffer. The gels were then dried using a speed vacuum. A 50-μl aliquot of trypsin (20 ng/μl) or chymotrypsin (25 ng/μl) in 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate buffer was added to the dehydrated gel. The gel was set on ice for 10 min for rehydration before the addition of another 20 μl of 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate buffer. The mixture was then incubated at room temperature overnight. The peptides were extracted from the gel using 50% acetonitrile with 5% formic acid several times and pooled together. The extracted pools were concentrated in a speed vacuum to ∼25 μl.

Nano-LC MS/MS (LC/MS/MS)—Capillary-liquid chromatography-nanospray tandem mass spectrometry (nano-LC/MS/MS) was performed on a Thermo Finnigan LTQ mass spectrometer equipped with a nanospray source operated in positive ion mode. The LC system was an UltiMate™ Plus system from LC-Packings (Sunnyvale, CA) with a Famos autosampler and Switchos column switcher. Five microliters of each sample were first injected into the trapping column (LC-Packings) and washed with 50 mm acetic acid. The injector port was switched to inject, and the peptides were eluted off the trap onto a 5-cm, 75-μm (inner diameter) ProteoPep II C18 reversephase column (New Objective, Inc., Woburn, MA) packed directly in the nanospray tip. Solvent A was 50 mm acetic acid in water, and solvent B was acetonitrile. Peptides were eluted directly off the column into the LTQ system with a gradient of 2-80% solvent B at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The total run time was 65 min. The scan sequence of the mass spectrometer was programmed for MS/MS scans of the 10 most abundant peaks in the spectrum. Dynamic exclusion was used to exclude multiple MS/MS of the same peptide after detecting it three times. Sequence information from the MS/MS data were processed using the Mascot 2.0 active Perl script with standard data processing parameters. Data base searching was performed against the NCBInr data base using MASCOT 2.0 (Matrix Science, Boston, MA). The mass accuracy of the precursor ions was set to 1.5 Da to accommodate accidental selection of the 13C ion, and the fragment mass accuracy was set to 0.5 Da. The number of missed cleavages permitted in the search was 2 for both tryptic and chymotryptic digestions. The considered modifications (variable) were cysteine oxidation and nitration on tyrosine and tryptophan.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Generation of Antibody against the Epitope of Glutathione Binding Domain of the SQR—In the previous study we identified a specific tryptic peptide, 77AAFGLSEAGFNTACVTK93, that is involved in the GS binding domain of the flavoprotein of SQR (7). To gain insight into the functional role of the identified GS binding domain, we generated a polyclonal antibody against this domain.

Based on the published three-dimensional structure of SQR (32), a 17-residue peptide sequence (aa 77-93) exhibited an α-helix-β-turn-sheet conformation (aa 72-93) as indicated in supplemental Fig. 1. To stabilize the α-helical conformation, the peptide p-GSC90 sequence 72GAGLRAAFGLSEAGFNTACVTK93 was designed with additional residues at the N terminus. This B cell epitope 22-residue sequence contains an α-helix-β-turn-sheet structure as indicated in supplemental Fig. 1. We have previously demonstrated that the design, synthesis, and immunological and structural characterization of such motifs can be achieved successfully (33). The peptide of p-MVFGSC90 was synthesized as chimeric constructs incorporating an 18-residue promiscuous T-helper measles virus (MVF sequence, 288KLLSLIKGVIVHRLEGVE305) T cell epitope linked via a 4-residue linker (GPSL) and p-GSC90 B cell epitope on a Milligen/Biosearch 9600 solid-phase peptide synthesizer as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The crude peptide was purified to homogeneity by reverse phase HPLC and fully characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectroscopy, which gave the exact mass unit ((M+H)+ 4478.96] as calculated [(M+H)+ 4478.48).

Two New Zealand White rabbits (6-8 weeks old) were immunized with the immunogen p-MVFGSC90. Sera were collected, and antibodies were purified as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The generated antibody is termed AbGSC90.

Immunological Specificity of Antibodies—The immunological cross-reactivity of purified antibodies was analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (supplemental Fig. 2) using mitochondrial electron transfer complex including SQR (complex II), SCR (supercomplex containing SQR and QCR), NADH-ubiquinone reductase (or complex I), and ubiquinolcytochrome c reductase (QCR or complex III) as antigens. When each antigen, at a fixed protein concentration (see supplemental Fig. 2), was titrated with various amounts of antibody preparation, the AbGSC90 antibodies reacted at a high titer, with antigens containing a 70-kDa FAD binding subunit in the form of SQR or SCR. There was a very low binding detected between AbGSC90 and NADH-ubiquinone reductase or QCR. The protein concentrations of SCR used for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay were 3 times higher than those of SQR because the amount of SQR present in SCR is about 33%.

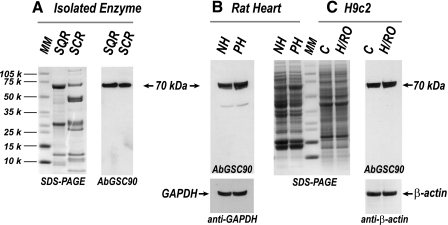

When the immunological specificity of AbGSC90 was characterized by a Western blot (Fig. 1), they were seen to bind specifically to the 70-kDa subunit of SQR and SCR (Fig. 1A). As expected, no binding was observed with NADH-ubiquinone reductase and QCR (data not shown). Antibodies were further used to test the myocardial tissue homogenates obtained from normal and post-ischemic hearts with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as individual protein loading controls. As indicated in Fig. 1B, they bind specifically to the 70-kDa subunit of SQR in the myocardial tissue homogenates. This result also illustrates that there was no significant change in the level of protein expression of the 70-kDa subunit during ischemia/reperfusion injury (7).

FIGURE 1.

Western blot analysis of antibody AbGSC90. SDS-PAGE was carried out according to the procedure described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, SDS-PAGE (left panel) and immunoblotting with AbGSC90 (right panel), SQR (10 μg) and SCR(10 μg). MM denotes molecular weight marker standard. B, tissue homogenate (100 μg) from rat heart. Immunoblotting with AbGSC90 (left panel) and SDS-PAGE (right panel). NH denotes normal myocardium, and PH denotes post-ischemic myocardium. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. C, cell lysate (100 μg) from H9c2 under the conditions of normoxia (C) and H/RO. SDS-PAGE (left panel) and immunoblotting with AbGSC90 (right panel).

The antibodies were further used to probe the 70-kDa subunit of SQR using the rat cardiac myoblast cell line H9c2. Cells were subjected to hypoxia (1 h)/reoxygenation (1 h) and then lysed by sonication. Cell lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE and then probed with AbGSC90. β-Actin was used as an individual protein loading control. As shown in Fig. 1C, antibodies bind specifically to the SQR 70-kDa polypeptide in the cell lysate of H9c2 cells. There is no significant change in the protein expression of the 70-kDa subunit during hypoxia/reoxygenation. These results together demonstrate that the rationale-based designed antibodies against B cell epitope, p-GSC90, are highly specific with high sensitivity and are, thus, suitable for in vivo or in vitro studies.

Immunoinhibition of Succinate-ubiquinone Reductase by

AbGSC90—The effect of AbGSC90 binding on the electron transfer and

generation activities of

SQR was measured (supplemental Fig. 3). When the isolated SQR was incubated

with various amounts of antibodies, the electron transfer activity (ETA) of

SQR decreased as the amount of antibodies increased. A maximum inhibition of

25% was observed with 400 μg of antibody per nmol (based on heme

b) of SQR, indicating that the binding of AbGSC90 with the epitope

that is involved in GS binding (aa 77-93) moderately decreased the electron

transfer efficiency catalyzed by SQR.

generation activities of

SQR was measured (supplemental Fig. 3). When the isolated SQR was incubated

with various amounts of antibodies, the electron transfer activity (ETA) of

SQR decreased as the amount of antibodies increased. A maximum inhibition of

25% was observed with 400 μg of antibody per nmol (based on heme

b) of SQR, indicating that the binding of AbGSC90 with the epitope

that is involved in GS binding (aa 77-93) moderately decreased the electron

transfer efficiency catalyzed by SQR.

In the previous studies (7) a modest increase of ETA resulted from in vitro S-glutathionylation of SQR. However, the binding of antibodies against p-GSC90 led to a moderate reduction of ETA in the SQR. These results support that the peptide of the GS binding domain may play a regulatory role in the redox function of SQR. This result also indicates that the peptide of the GS binding domain is surface-exposed, which is confirmed by the x-ray structure of mammalian SQR (32). The property of surface exposure renders it accessible to AbGSC90.

The binding of antibodies also moderately decreased the

generation mediated by

SQR by 26% as measured by the acetylated cytochrome c reduction assay

(supplemental Fig. 3A) or EPR spin trapping with DEPMPO (supplemental

Fig. 3B). The decreased

generation mediated by

SQR by 26% as measured by the acetylated cytochrome c reduction assay

(supplemental Fig. 3A) or EPR spin trapping with DEPMPO (supplemental

Fig. 3B). The decreased

generation can be

explained by the ETA decrease resulting from antibody binding since the

electron transfer activity of SQR is required for the electron leakage for

generation can be

explained by the ETA decrease resulting from antibody binding since the

electron transfer activity of SQR is required for the electron leakage for

production

(34).

production

(34).

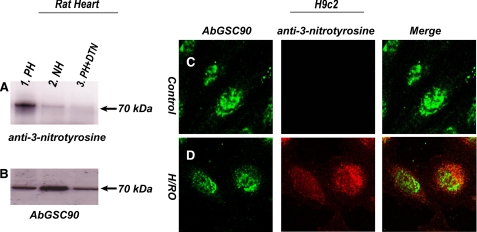

Protein Tyrosine Nitration of SQR 70-kDa FAD Binding Subunit in the Post-ischemic Myocardium—A previous study established that deglutathionylation of the SQR 70-kDa flavin protein is an early event during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (7). Protein tyrosine nitration in mitochondria has been detected using the myocyte model subjected to hypoxia/reoxygenation. In a separate study Han et al. (20) reported a similar observation in the mitochondria of endothelial cells under the conditions of ischemia/reperfusion. Therefore, oxidative modification with protein nitration at the SQR 70-kDa subunit is expected to follow after the highly reductive conditions of myocardial ischemia. To test this hypothesis, the AbGSC90 was immobilized onto the commonly used Affi-Gel 10 (Bio-Rad) on the basis of the protein's isoelectric point as outlined in the product literature (bulletin no. 1085). The immobilized AbGSC90 was subsequently used to immunoprecipitate the 70-kDa FAD binding subunit from the tissue homogenates of post-ischemic myocardium followed by immunoblotting with a polyclonal antibody against 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT, Upstate). As indicated in Fig. 2, we have detected a very weak signal of nitrotyrosine on the 70-kDa subunit of SQR from tissue homogenates of the normal heart (panel A, lane 2). The signal intensity of protein nitration on the 70-kDa subunit of SQR was greatly enhanced in tissue homogenates of the post-ischemic myocardium (panel A, lane 1). The detected Western blot signal was abolished by pretreatment of sample with dithionite due to reduction of 3-nitrotyrosine to 3-aminotyrosine (panel A, lane 3). The tissue homogenates were further immunoblotted with AbGSC90 to measure the protein loading of SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2, panel B) and confirm the protein nitration occurring at the 70-kDa. The ratio of signal intensity obtained from anti-3-nitrotyrosine antibody that of AbGSC90 is ∼6 for the post-ischemic myocardium and ∼2 for normal myocardium.

FIGURE 2.

A and B, protein tyrosine nitration of the 70-kDa subunit of SQR in tissue homogenates from the post-ischemic myocardium. C and D, H/RO increases 3-nitrotyrosine staining in the SQR 70-kDa subunit of cardiac myoblasts. Myocardial tissue homogenates (300 μg) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with AbGSC90 and subsequently subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-3-nitrotyrosine antibody (A, upper panel) and AbGSC90 (B, lower panel). A, lane 1, protein from post-ischemic myocardium (PH). Lane 2, protein from normal myocardium (NH). Lane 3, protein from post-ischemic myocardium was treated with 20 mm sodium dithionite (PH + DTN). Membrane was probed with anti-3-nitrotyrosine antibody. B, same as A except that membrane was probed with AbGSC90. C, H9c2 cardiac myoblasts were fixed and stained for 3-nitrotyrosine and the SQR 70-kDa subunit. Fluorescence images were acquired with confocal microscopy and merged to determine whether the increase in 3-nitrotyrosine signal was located in the SQR 70-kDa subunit. D, same as C except that cells were subjected to hypoxia (1 h) and reoxygenation (1 h).

To confirm that deglutathionylation of 70-kDa subunit occurred during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion, the same sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE under the non-reducing conditions and immunoblotted with anti-GSH monoclonal antibody (Viro-Gen, Watertown, MA). As indicated by Western blots (supplemental Fig. 4A), the intrinsic protein S-glutathionylation on the 70-kDa subunit of SQR of non-ischemic tissue was subsequently decreased (by 57.8 ± 11.9%) in the post-ischemic myocardium. This result was consistent with the previous observation (7).

To further demonstrate that protein tyrosine nitration at the 70-kDa subunit was enhanced under the physiological conditions of hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/RO), rat cardiac myoblasts (H9c2) were subjected to the conditions of control or H/RO at 37 °C before immunofluorescence staining using AbGSC90. Similar fluorescence intensities of AbGSC90 staining were detected by confocal microscopy under the control and H/RO conditions (Figs. 2, C and D, left pictures). To determine the effects of H/RO-mediated protein tyrosine nitration, 3-NT in myoblasts was probed with monoclonal antibody against 3-NT and then examined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. A very low level of 3-NT staining was observed in myoblasts under the control conditions (Fig. 2C, middle). Exposing myoblasts to hypoxia (1 h) followed by reoxygeneration (1 h) resulted in substantially more intense 3-NT staining that showed modest but significant localization of 3-NT in the 70-kDa subunit of SQR (Fig. 2D, middle and right), further demonstrating that reactive nitrogen species-mediated protein nitrotyrosine formation enhanced in the SQR 70-kDa subunit under the physiological conditions of ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Enhancement of protein tyrosine nitration in mitochondrial protein (the SQR 70-kDa subunit in this study) during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion is likely OONO--mediated and caused by the alternations of NO metabolism. Production of excess NO is likely mediated by eNOS and NOS-independent nitrite disproportionation (reduction of nitrite to NO) in the early phases of reperfusion after ischemia. This mechanism has been demonstrated in the mouse model of eNOS-/-, in which immunostaining of 3-NT is significantly decreased in the post-ischemic myocardium of eNOS-/- (10, 11, 14). Furthermore, post-ischemic myocardial oxygen consumption mediated by eNOS-derived NO has been linked to oxidative inactivation of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (10).

NO generated from a NOS-independent pathway has been reported in the ischemic heart by direct reduction of nitrite to NO (18, 19). Specifically, mitochondria have been suggested to be major players in catalyzing nitrite disproportionation in heart tissue (19, 35). Presumably, this pathway mediated by the mitochondria of ischemic tissue can be greatly facilitated under highly acidic and reductive conditions.

Stimulation of iNOS up-regulation has been marked in the post-ischemic

myocardium (11). NO generated

by iNOS overexpression has been suggested to be the major pathway during

chronic reperfusion after ischemia

(11). We have analyzed the

mRNA and protein expression of iNOS from the post-ischemic myocardium by

real-time quantitative PCR and immunoblotting with anti-iNOS polyclonal

antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories) in this study. Our real-time

quantitative PCR analysis indicated that the mRNA expression of iNOS was

increased 3.0-3.7-fold in the 24-h postischemic rat myocardium compared with

that of the non-ischemic rat myocardium (supplemental Fig. 4B).

Significant enhancement of iNOS expression was also detected in the

post-ischemic myocardium (supplemental Fig. 4B). Because this result

was consistent with previous reports using the mouse model

(10,

11,

14), we suggest that

OONO- formation is indeed because of overproduction of NO and

in the post-ischemic

myocardium.

in the post-ischemic

myocardium.

The rate constant for NO trapping of

is higher than that for

mitochondrial Mn-SOD-catalyzed

is higher than that for

mitochondrial Mn-SOD-catalyzed

dismutation

(109-1010

m-1s-1

(36) versus

108-109

m-1s-1

(34)). Therefore,

overproduction of NO would be expected to block mitochondrial respiration,

increase electron leakage, and subsequently stimulate OONO-

formation in the post-ischemic myocardium. Presumably, hypoxia-induced

deglutathionylation of SQR increases the electron leakage for

dismutation

(109-1010

m-1s-1

(36) versus

108-109

m-1s-1

(34)). Therefore,

overproduction of NO would be expected to block mitochondrial respiration,

increase electron leakage, and subsequently stimulate OONO-

formation in the post-ischemic myocardium. Presumably, hypoxia-induced

deglutathionylation of SQR increases the electron leakage for

generation from the FAD

binding subunit (7), thus

facilitating local OONO- formation and subsequently enhancing

protein tyrosine nitration at the SQR 70-kDa subunit.

generation from the FAD

binding subunit (7), thus

facilitating local OONO- formation and subsequently enhancing

protein tyrosine nitration at the SQR 70-kDa subunit.

Furthermore, our recent research progress of in vitro EPR studies

shows that excess NO stimulates SOD-dependent oxygen-free radical generation

through the formation of a dinitroso-iron intermediate at the S1 center

(2Fe-2S) of SQR.3

Therefore, it is likely that binding of NO to the S1 center blocks electron

flow and stimulates  production on the flavin protein subunit, consequently leading to nitration of

the 70-kDa-derived subunit protein tyrosine.

production on the flavin protein subunit, consequently leading to nitration of

the 70-kDa-derived subunit protein tyrosine.

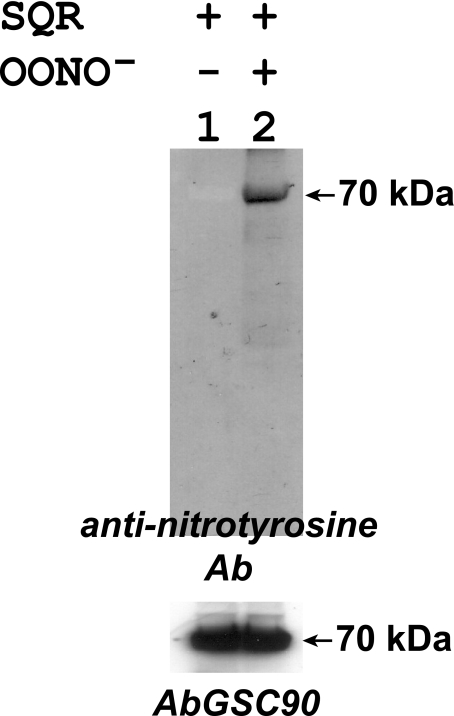

In Vitro Protein Tyrosine Nitration of SQR—To gain a deeper insight into the molecular mechanism of SQR-derived tyrosine nitration, the isolated SQR was reduced with dithiothreitol (1 mm) and then passed through a Sephadex G-25 column. SQR (1 μm) was subjected to in vitro protein nitration with OONO- (100 μm) treatment. The resulting OONO--treated SQR was subjected to SDS-PAGE in the presence of β-mercaptoethanol followed by immunoblotting with anti-3-nitrotyrosine antibody. It was observed that the 70-kDa subunit of SQR was involved in site-specific protein nitration as indicated in Fig. 3. The Western blot signal increased in proportion to the dosage of OONO- used (data not shown). Both native and nitrated SQRs were further blotted with AbGSC90. There was no significant difference (less than 5%) observed in the Western signal of 70-kDa, indicating that protein nitration of 70-kDa did not affect AbGSC90 binding at a significant level (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

In vitro protein tyrosine nitration of the 70-kDa subunit of isolated SQR by peroxynitrite. SQR was isolated from the bovine heart according to the published procedure (26, 27). Protein (1 μm, based on heme b) was incubated with peroxynitrite (100 μm) at room temperature for 1 h. Excess peroxynitrite was removed by passing through a Sephadex G-25 column. The protein was then subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-3-nitrotyrosine polyclonal antibody (Ab).

The protein band of the 70-kDa subunit of OONO--treated SQR (lane 2 in Fig. 3) was subjected to in-gel digestion with trypsin/chymotrypsin and analyzed by LC/MS/MS. With this technique, 93.4% of the amino acid sequence of the 70-kDa subunit was identified (supplemental Fig. 5). All 21 tyrosine residues were identified by LC/MS/MS under reducing conditions in the presence of β-ME (supplemental Fig. 5).

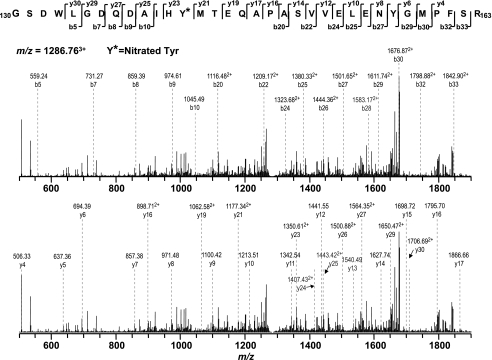

Single nitration of native protein will increase the molecular weight by 45 Da. Therefore, the mass spectra from the proteolytic digest of nitrated SQR 70-kDa polypeptides were examined for the addition of 45 × n Da (n is the number of tyrosine residues in the peptide). In the tryptic digest MS/MS results, a mass difference of 45 Da was observed in two peptide fragments, 130-163 (130GSDWLGDQDAIHYMTEQAPASVVELENYGMPFSR163, NOY142) and 48-76 (48VSDAISAQYPVVDHEFDAVVVGAGGAGLR76, NOY56), indicating that these two peptides were nitrated. Further analysis suggested that nitration occurred on the specific tyrosine residues, Tyr-142 and Tyr-56. As shown in Fig. 4 and Table 1, in the MS/MS spectrum of (NOY142)3+ at m/z 1282.763+, some of the structurally informative fragment ions including y23-y27, y29-y30, b20, b22, b24-b30, and b32-b33 were observed with a mass shift of 45 Da compared with native fragment ions, thus allowing unequivocal assignment of the nitrated adduct to the tyrosine-142 residue of the tryptic peptide 130GSDWLGDQDAIHYMTEQAPASVVELENYGMPFSR163. Other sequence informative ions, y4-y17, y19, y21, b5, and b7-b10, provided the evidence to ensure that the sequence of (NOY142)3+ was matched to the sequence of aa residues 130-163 of the 70-kDa subunit of the SQR. These data allow unequivocal assignment of tyrosine-142 as the site of nitration.

FIGURE 4.

MS/MS of triply protonated molecular ion of the nitrated peptide (130GSDWLGDQDAIHYMTEQAPASVVELENYGMPFSR163) (where the underline indicates Tyr-142) of the 70-kDa subunit from peroxynitrite-treated SQR. The sequence-specific ions are labeled as y and b ions on the spectrum. The amino acid residues involved in nitration are identified by asterisks.

TABLE 1.

Analysis and identification of the molecular ions from the MS/MS spectrum (Fig. 4) obtained from the triply protonated ion (NOY142)3+, m/z = 1286.763+

| Δm between yn and yn-1 | Fragment ion | Measured m/z | Sequence | Measured m/z | Fragment Ion | Δm between bn and bn-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gly | ||||||

| Ser | ||||||

| Asp | ||||||

| Trp | ||||||

| 112.44 | y30 | 1706.69+2 | Leu | 559.24 | b5 | |

| 172.24 (115 + 57) | y29 | 1650.47+2 | Gly | |||

| Asp | 731.27 | b7 | 172.03 (57 + 115) | |||

| 126.94 | y27 | 1564.35+2 | Gln | 859.39 | b8 | 128.12 |

| 114.92 | y26 | 1500.88+2 | Asp | 974.61 | b9 | 115.22 |

| 71.98 | y25 | 1443.42+2 | Ala | 1045.49 | b10 | 70.88 |

| 113.64 | y24 | 1407.43+2 | Ile | |||

| 344.54 (163 + 45 + 137) | y23 | 1350.61+2 | His | |||

| Tyr(NO2) | ||||||

| 231.52 (101 + 131) | y21 | 1177.34+2 | Met | |||

| Thr | ||||||

| 257.50 (128 + 129) | y19 | 1062.58+2 | Glu | |||

| Gln | ||||||

| 70.96 | y17 | 1866.66 | Ala | |||

| 96.98 | y16 | 1795.70 | Pro | |||

| 70.98 | y15 | 1698.72 | Ala | 1116.48+2 | b20 | |

| 87.25 | y14 | 1627.74 | Ser | |||

| 98.94 | y13 | 1540.49 | Val | 1209.17+2 | b22 | 185.38 (87 + 99) |

| 99.01 | y12 | 1441.55 | Val | |||

| 129.03 | y11 | 1342.54 | Glu | 1323.68+2 | b24 | 229.02 (99 + 129) |

| 113.09 | y10 | 1213.51 | Leu | 1380.33+2 | b25 | 113.3 |

| 128.94 | y9 | 1100.42 | Glu | 1444.36+2 | b26 | 128.06 |

| 114.10 | y8 | 971.48 | Asn | 1501.65+2 | b27 | 114.58 |

| 162.99 | y7 | 857.38 | Tyr | 1583.17+2 | b28 | 163.04 |

| 57.03 | y6 | 694.39 | Gly | 1611.74+2 | b29 | 57.14 |

| 131.03 | y5 | 637.36 | Met | 1676.87+2 | b30 | 130.26 |

| y4 | 506.33 | Pro | ||||

| Phe | 1798.88+2 | b32 | 244.02 (97 + 147) | |||

| Ser | 1842.90+2 | b33 | 88.04 | |||

| Arg |

Likewise, in the MS/MS spectrum of (NOY56)3+ at m/z 982.903+ (supplemental Fig. 6), some of the structurally informative ions including y21, y24, b23-b24, and b27-b28 were detected with a mass shift of 45 Da. Another series of detected sequence informative ions, y3 and y5-y17, match the sequence of aa residues 48-76. Together these data show that tyrosine-56 is involved in the nitrated adduct of the tryptic peptide NOY56.

Substantial evidence from our previous investigation using mouse/rat models strongly support that increasing protein nitration marked in the post-ischemic myocardium is caused by OONO- formation in vivo (10, 11, 14, 15). Therefore, in vitro OONO--mediated protein tyrosine nitration provided an appropriate way to enrich protein 3-NT in the SQR 70-kDa, thus facilitating the detection of MS/MS. The value of in vitro results should be recognized as a model since this system yielded a protein tyrosine nitration in a highly site-specific manner and resulted in impairing enzymatic function, which meets the criteria of in vivo situation and supports OONO- to be the source of nitrating agent in vivo.

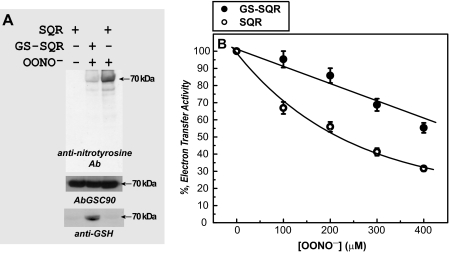

S-Glutathionylation of SQR 70-kDa Subunit Preserves Enzyme Inactivation

by Peroxynitrite in Vitro—In a previous study we demonstrated that

S-glutathionylation of SQR diminishes the SQR-derived protein radical

formation induced by oxygen free radical(s), which supports the protective

role of protein S-glutathionylation

(7). To learn whether protein

S-glutathionylation exerts a similar protective effect on SQR

function related to OONO--mediated injury, we

S-glutathionylated isolated SQR in vitro with GSSG according

to a published procedure (7).

The resulting GS-SQR was incubated with OONO- (100

μm) for 1 h at room temperature. Excess degraded product

was removed by passing through a

Sephadex G-25 column. The sample was subjected to probing with a monoclonal

antibody against 3-NT. As indicated in Fig.

5A, the Western signal of SQR-derived protein nitration

was significantly diminished (by 77.2%, n = 3) in the

S-glutathionylated SQR, thus supporting the protective role of

S-glutathionylation. In the control experiment, the same membrane was

probed with AbGSC90. As indicated in the

Fig. 5A (lower

panels), the signal intensity obtained was slightly decreased by 13% of

control (n = 3) for the GS-SQR, confirming roughly equal amounts of

protein loading. Furthermore, the signal intensity probed with anti-GSH

monoclonal antibody was shown to be significantly higher for GS-SQR

(Fig. 5A), indicating

satisfactory efficiency of protein S-glutathionylation induced by

GSSG.

was removed by passing through a

Sephadex G-25 column. The sample was subjected to probing with a monoclonal

antibody against 3-NT. As indicated in Fig.

5A, the Western signal of SQR-derived protein nitration

was significantly diminished (by 77.2%, n = 3) in the

S-glutathionylated SQR, thus supporting the protective role of

S-glutathionylation. In the control experiment, the same membrane was

probed with AbGSC90. As indicated in the

Fig. 5A (lower

panels), the signal intensity obtained was slightly decreased by 13% of

control (n = 3) for the GS-SQR, confirming roughly equal amounts of

protein loading. Furthermore, the signal intensity probed with anti-GSH

monoclonal antibody was shown to be significantly higher for GS-SQR

(Fig. 5A), indicating

satisfactory efficiency of protein S-glutathionylation induced by

GSSG.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of peroxynitrite on SQR and GS-SQR. Isolated SQR was pretreated with dithiothreitol (DTT, 1 mm) and then passed through Sephadex G-25 column to remove excess DTT. Dithiothreitol-treated SQR was subjected to in vitro S-glutathionylation, yielding GS-SQR. A, the protein of SQR or GS-SQR (1 μm of heme b) in phosphate-buffered saline was incubated with peroxynitrite (100 μm) at room temperature for 1 h. Thirty-five pmol of peroxynitrite-treated SQR and GS-SQR were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-3-nitrotyrosine polyclonal antibody (Ab). B, same as A, except that SQR and GS-SQR were reacted with various amounts of peroxynitrite (0-400 μm). The electron transfer activities of SQR and GS-SQR were then assayed by Q2-stimulated DCPIP reduction.

OONO--treated SQR and GS-SQR were further subjected to analysis of electron transfer activity of Q2-mediated DCPIP reduction. Both SQR and GS-SQR were incubated with different concentrations of OONO- (from 0-400 μm) at room temperature for 20 min before the activity assay. As indicated in Fig. 5B, significant protection of the electron transfer activity from OONO- inactivation was observed in GS-SQR. Specifically, we have observed that the protective effect of S-glutathionylation is observed at a lower concentration of OONO- (e.g. 96 versus 67% ETA remaining at 100 μm OONO- in Fig. 5B).

The identified nitrated peptide (130GSDWLGDQDAIHYMTEQAPASVVELENYGMPFSR163) containing Tyr-142 (Tyr-99 in the mature protein) of bovine SQR is highly conserved in proteins from humans (129GSDWLGDQDAIHYMTEQAPAAVVEENYGMPFSR162), mice, rats, yeast (120GSDWLGDQDSIHYMTREAPKSIIELEHYGVPFSR153), and Escherichia coli (75GSDYIGDQDAIEYMCKTGPEAILELEHMGLPFSR108). From this information together with the results of the current in vitro study, we suggest that the Tyr-142 of the flavoprotein subunit of SQR is the critical tyrosine susceptible to oxidative damage induced by OONO-, and S-glutathionylation of Cys-90 should play a role in antioxidant defense to combat oxidative attack from OONO-.

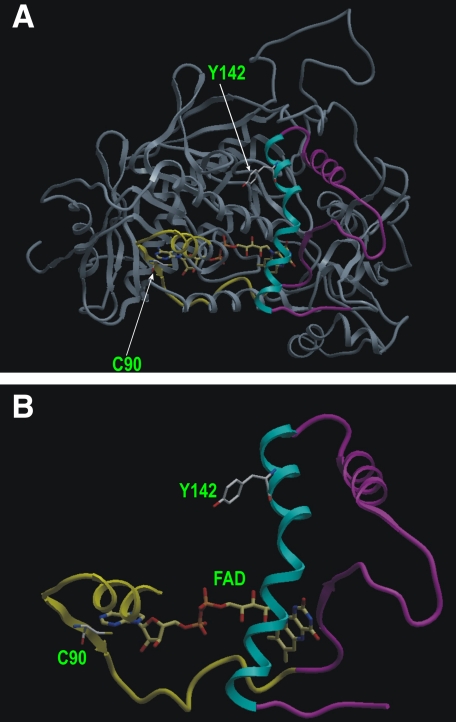

Based on the x-ray crystal structure of mammalian SQR (PDB ID 1ZOY), the

flavin subunit has a Rossman-type fold with four major domains

(32)

(Fig. 6A). Tyr-142 is

located in the major helix (residues 136-158 in the precursor; see the

cyan helix in Figs. 6, A

and B) of a floating subdomain (residues 105-196 in the

precursor) which is a part of the large FAD binding domain (residues 53-316

and residues 404-488 in the precursor). Specifically, Tyr-142 is highly

surface-exposed (Fig.

6A) and situated in the hydrophilic environment,

suggesting that this specific tyrosine is susceptible to nitration by

OONO-. The x-ray structure reveals that Tyr-142 is ∼20 Å

away from the isoalloxazine ring of FAD. Cys-90 (Cys-47 in the mature protein)

is located within the part of the N-terminal β barrel subdomain (residues

53-104 in the precursor, yellow ribbon of

Figs. 6, A and

B) of the large FAD-binding domain. Cys-90 is near the

AMP moiety of FAD (∼7.7 Å), where the major catalysis of electron

transfer and  production

occurs. Therefore, S-glutathionylation of Cys-90 seems likely to

induce a conformational change near the floating subdomain (residues 105-196,

magenta-cyan ribbon of Figs. 6,

A and B), which might increase the shielding

effect on Tyr-142, rendering Tyr-142 less accessible to OONO-

oxidation.

production

occurs. Therefore, S-glutathionylation of Cys-90 seems likely to

induce a conformational change near the floating subdomain (residues 105-196,

magenta-cyan ribbon of Figs. 6,

A and B), which might increase the shielding

effect on Tyr-142, rendering Tyr-142 less accessible to OONO-

oxidation.

FIGURE 6.

Location of S-glutathionylated cysteine residue Cys-90 and nitrated tyrosine residue Tyr-142 in the FAD binding domain of mammalian SQR. A, Rossmann-type fold of Fp subunit in the three-dimensional structure (PDB ID 1ZOY) of SQR. Arrows indicate the positions of Cys-90 (Cys-47 of mature protein) and Tyr-142 (Tyr-99 of mature protein), which is situated in a part (residues 77-163, shown with yellow-magenta-cyan ribbon) of the FAD binding domain (residues 53-316). B, ribbon representation of residues 77-163. The yellow-magenta-cyan ribbon (aa 77-163) in A is dragged out. Tyr-142, Cys-90, and FAD are shown in a ball-and-stick atomic model. Yellow ribbon, N-terminal β barrel subdomain (residues 77-104) hosting Cys-90. Magenta-cyan ribbon, floating subdomain (residues 105-163) hosting Tyr-142.

Tyr-56 (Tyr-13 in the mature protein) is the other tyrosine involved in OONO--mediated nitration as revealed by LC/MS/MS. Tyr-56 is near the N terminus of the 70-kDa subunit and is conserved in enzymes from bovine, porcine, human, mouse, and yeast SQR. However, Tyr-56 is not conserved in the bacterial SQR. It is likely that Tyr-56 is a secondary target for excess OONO-.

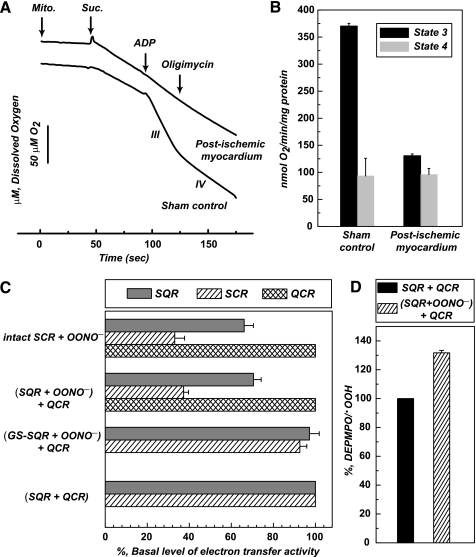

Mitochondrial Functions in the Post-ischemic Myocardium—To verify the effect of protein nitration occurring in the postischemic myocardium on the mitochondrial function, mitochondria were isolated from the tissue of risk region and subjected to measurement of respiratory control ratio by the polarographic method using an oxygen electrode. As indicated in Figs. 7, A and B, ADP-stimulated respiration (state 3) was decreased from 370 ± 5.1 (Sham control) to 130.6 ± 3.4 nmol of O2/min/mg of protein after myocardial infarction. The respiratory control ratio was decreased from 3.3 ± 0.1 (sham control) to 1.3 ± 0.1, suggesting protein tyrosine nitration caused by ischemia/reperfusion injury may contribute to defects in the mitochondrial integrity due to marked reduction of ADP-stimulated respiration.

FIGURE 7.

A and B, State 3 and state 4 respiratory rates of

mitochondrial (Mito.) preparations from the risk region of

post-ischemic myocardium. Post-ischemic myocardium was obtained as described

under “Experimental Procedures.” The tissue of risk region was

excised and subjected to mitochondrial preparations according to published

method (48). The oxygen

consumption by mitochondria (0.5 mg/ml) was induced by succinate

(Suc., 5 mm) and measured by oxygen polarographic method

at 30 °C. State 3 oxygen consumption was stimulated by the addition of ADP

(200 μm), and state 4 oxygen consumption was determined after

addition of oligomycin (2 μm) followed by ADP addition.

C, effect of OONO--mediated protein nitration on the ETA

of intact SCR and reconstituted SCR. Intact SCR (3 μm, based on

heme b) and SQR (1 μm) were incubated with

OONO- (100 μm) at room temperature for 30 min.

Nitrated SQR was then reconstituted with the native QCR (2 μm)

at 0 °C for 1 h. Reconstituted SCR and intact SCR were subjected to ETA

measurement. SCR and QCR activities were assayed as reported previously

(7). D, effect of

OONO--mediated protein nitration of SQR on the

generation catalyzed by

reconstituted SCR. An aliquot of enzyme solution (1 μm of heme

b) was withdrawn and added to a mixture containing succinate (180

μm), DEPMPO (20 mm), and

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (1 mm) before EPR measurement.

The DEPMPO/.OOH in each spectrum was quantitated by double

integration of simulated spectrum (supplemental Fig. 8).

generation catalyzed by

reconstituted SCR. An aliquot of enzyme solution (1 μm of heme

b) was withdrawn and added to a mixture containing succinate (180

μm), DEPMPO (20 mm), and

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (1 mm) before EPR measurement.

The DEPMPO/.OOH in each spectrum was quantitated by double

integration of simulated spectrum (supplemental Fig. 8).

Impairment of Protein-Protein Interaction between Complex II and Complex III by Protein Nitration of SQR—Direct exposure of intact mitochondria (0.5 mg/ml) to OONO- (100 μm) impaired ADP-stimulated respiration by 45% and decreased respiratory control ratio by 42%. However, the treatment failed to induce protein nitration of SQR as OONO- is nearly membrane-impermeable. To better define the role of SQR-derived tyrosine nitration in the impairment of electron transport chain, the systems of SCR and reconstituted SCR were employed. SCR is the supercomplex hosting SQR and QCR (or complex III). The enzymatic activity of SCR in catalyzing electron transfer from succinate to cytochrome c is derived from protein-protein interaction between SQR and QCR (26, 37). Pretreatment of intact SCR (3 μm, based on heme b) with OONO- (100 μm) resulted in the protein tyrosine nitration at the multiple polypeptides including the 70-kDa subunit of SQR. As indicated in Fig. 7C, the ETA of SQR in the SCR was decreased by 34%, and the ETA of SCR was decreased by 67%. However, the ETA of QCR did not suffer significant loss by OONO-, indicating the impairment of protein-protein interaction between SQR and QCR. It should be noted that similar inhibitory profile was also observed when intact SCR was pretreated with a different dosage of OONO- (supplemental Fig. 7).

To further demonstrate the ability of SQR-derived tyrosine nitration to impair protein-protein interaction, isolated SQR was subjected to in vitro protein nitration with OONO- (Fig. 3). Nitrated SQR was reconstituted with native QCR in vitro before measuring the ETA of SCR. The reconstituted SCR suffered a dramatic loss of ETA by 63% compared with that of the control (in vitro reconstitution of native SQR and native QCR) as indicated in Fig. 7C. Replacement of nitrated SQR with GS-SQR pretreated with OONO- in the system restored the reconstituted SCR activity (Fig. 7C), thus further supporting the protective role of S-glutathionylation. It is worth noting that the ETA of native QCR was not significantly affected by OONO- treatment.

generation by

reconstituted SCR was induced by succinate and measured with EPR spin-trapping

with DEPMPO. As shown in Fig.

7D (EPR spectra provided in supplemental Fig. 8),

generation by

reconstituted SCR was induced by succinate and measured with EPR spin-trapping

with DEPMPO. As shown in Fig.

7D (EPR spectra provided in supplemental Fig. 8),

production (based on spin

quantitation of DEPMPO/.OOH) by the SCR reconstituted from nitrated

SQR with QCR was enhanced by 33% compared with that of control, presumably due

to the impairment of protein-protein interaction by protein nitration of

SQR.

production (based on spin

quantitation of DEPMPO/.OOH) by the SCR reconstituted from nitrated

SQR with QCR was enhanced by 33% compared with that of control, presumably due

to the impairment of protein-protein interaction by protein nitration of

SQR.

The evidence of protein-protein interaction between SQR and QCR has been demonstrated with EPR spin labeling and differential scanning calorimetry (37). It is likely that SQR impairment detected in the post-ischemic myocardium can decrease its interaction with QCR and subsequently diminish the electron transfer activity from succinate to cytochrome c in vivo, leading to weakening mitochondrial function.

It is known succinate-induced

generation by SCR is

mainly controlled by QCR and operated through Q-cycle mechanism. Impairment of

protein-protein interaction between SQR and QCR presumably increased unstable

semiquinone radical formation and subsequently enhanced

generation by SCR is

mainly controlled by QCR and operated through Q-cycle mechanism. Impairment of

protein-protein interaction between SQR and QCR presumably increased unstable

semiquinone radical formation and subsequently enhanced

production. Therefore,

results of current studies implicate that protein nitration of SQR plays a

significant role in triggering mitochondrial dysfunction during myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion, perhaps through diminishing protein-protein interaction

and augmenting oxidative stress.

production. Therefore,

results of current studies implicate that protein nitration of SQR plays a

significant role in triggering mitochondrial dysfunction during myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion, perhaps through diminishing protein-protein interaction

and augmenting oxidative stress.

Peroxynitrite-mediated Cysteine S-Sulfonation of SQR 70-kDa Subunit—The MS/MS spectra obtained from nitrated SQR were further examined for cysteine oxidation involved in S-sulfonation (conversion of -SH to -SO3H), identified by the addition of 48 Da. It was observed that Cys-267, Cys-476, and Cys-537 were S-sulfonated. In the MS/MS spectrum of doubly protonated ion (m/z 813.352+ and supplemental Fig. 9) of the tryptic peptide hosting Cys-476, a mass shift of 48 Da was observed in the fragment ions of y6, y8-y11, and b11-b14. The fragment ions of y4-y5, b3-b6, and b9 provided additional evidence of sequence information matched to amino acid residues 461-481. Likewise, a mass shift of 48 Da was detected in the MS/MS spectra of doubly protonated ions of tryptic peptides containing Cys-267 (aa residues 263-283 m/z 1121.562+) and Cys-537 (aa residues 529-548 m/z 1101.672+), (data not shown).

Cys-267, Cys-476, and Cys-537 are involved in OONO--mediated S-sulfonation. Cys-267 (Cys-224 in the mature protein) is located in the hydrophilic pocket of the β-barrel subdomain of the large FAD binding domain. Cys-476 (Cys-433 in the mature protein) is situated at the terminus of an α-helix in the FAD binding domain. Cys-537 (Cys-494 in the mature protein) is located on the surface of a three-helix bundle from the helical domain. All of the cysteines are surface-exposed, thus logically susceptible to OONO--mediated oxidation in vitro.

S-Sulfonation of Cys-537 was verified in this study. Cys-537 has been reported to be a secondary site (Cys-90 is the primary site) involved in S-glutathionylation induced by GSSG in vitro (7), implicating the possibility of S-sulfonation after deglutathionylation at the same cysteine residue of Cys-537 in the SQR 70-kDa subunit.

The milieu of the mitochondrial matrix is almost anoxic in the presence of the GSH/GSSG pool under normal physiological conditions (38). Analysis of redox compartmentation indicates that the relative redox states from most reductive to most oxidative are as follows: mitochondria > nuclei > endoplasmic reticulum > extracellular space (38). Thus, it is expected that very low oxygen tension in the mitochondrial environment of ischemic tissue should facilitate the free thiol state for most cysteines and that mitochondrial thiols are the targets of oxidants such as OONO-. They are vulnerable to oxidation such as S-sulfonation. Presumably, cysteine S-sulfonation is a mechanism of oxidative modification by mitochondrial proteins in response to oxidative stress.

We have attempted to map the specific sites of protein

sulfonation/nitration by immunoprecipitating the 70-kDa polypeptide from

tissue homogenates of the infarct area using AbGSC90. However, MS/MS analysis

of tryptic peptides revealed ambiguous results with low sequence coverage, and

we were not able to identify 3-NT/cysteine sulfonic acid peptides. Several

possible reasons may contribute to our failure in obtaining satisfactory MS/MS

data for 3-NT/cysteine sulfonic acid-containing peptides from tissue. They are

as follows. (i) Low abundance of 3-NT in 70-kDa was caused by generally low

levels of protein nitration in vivo. Specifically, accumulation of

3-NT in protein may undergo dynamic progress involved in protein tyrosine

denitration

(39-41)

or increased turnover of nitrated proteins

(42) in which even we have

employed the pathological tissue. (ii) Other factors are low expression of SQR

in tissue, poor recovery of 3-NT/cysteine sulfonic acid-containing peptide

from gel, and insufficient amounts of sample for MS/MS sequencing. These

limitations may be overcome by a more direct approach, but it is not likely to

isolate large amounts of the target protein from very limited amounts of

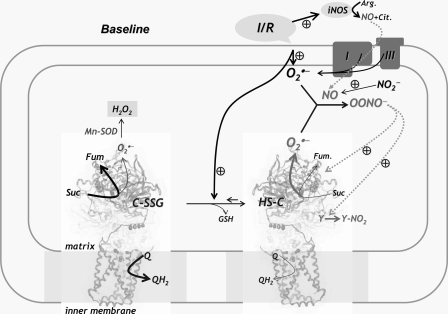

infarct tissue. Conclusion—The diagram of

Fig. 8 illustrates the

relationship between deglutathionylation, overproduction of ROS and NO, and

protein tyrosine nitration of SQR in mitochondria during myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion. Physiological conditions of hypoxia and reoxygenation

during ischemia and reperfusion trigger overproduction of NO through

up-regulation of three major pathways, including eNOS, iNOS, and nitrite

reduction (10,

11,

18,

19). These conditions also

stimulate  generation from

the mitochondrial electron transport chain, including Complex I and Complex

III (8,

34,

43-47).

Based on the results of in vitro studies, deglutathionylation of SQR

increases SQR-mediated

generation from

the mitochondrial electron transport chain, including Complex I and Complex

III (8,

34,

43-47).

Based on the results of in vitro studies, deglutathionylation of SQR

increases SQR-mediated  production (7). The enhanced

ability of SQR to produce

production (7). The enhanced

ability of SQR to produce  should augment the overall magnitude of OONO- formation and

consequent protein nitration in the post-ischemic heart. Specifically, we have

detected the enhancement of SQR-derived protein tyrosine nitration in the

post-ischemic myocardium. It is important to recognize the physiological

significance of this study was to elucidate the redox pathway in which protein

nitration occurs after deglutathiolation of SQR in the post-ischemic

myocardium. This redox pathway contributes to marked mitochondrial dysfunction

and offers a marker of oxidative stress in mitochondria during

ischemia/reperfusion. Although the detected redox modifications seem to have

modest effects on the electron transfer activity of SQR, the impact on

protein-protein interaction and the consequent mitochondrial respiration is

significant. Defining this molecular mechanism is important for understanding

how oxidants modulate post-ischemic injury caused by mitochondrial

dysfunction.

should augment the overall magnitude of OONO- formation and

consequent protein nitration in the post-ischemic heart. Specifically, we have

detected the enhancement of SQR-derived protein tyrosine nitration in the

post-ischemic myocardium. It is important to recognize the physiological

significance of this study was to elucidate the redox pathway in which protein

nitration occurs after deglutathiolation of SQR in the post-ischemic

myocardium. This redox pathway contributes to marked mitochondrial dysfunction

and offers a marker of oxidative stress in mitochondria during

ischemia/reperfusion. Although the detected redox modifications seem to have

modest effects on the electron transfer activity of SQR, the impact on

protein-protein interaction and the consequent mitochondrial respiration is

significant. Defining this molecular mechanism is important for understanding

how oxidants modulate post-ischemic injury caused by mitochondrial

dysfunction.

FIGURE 8.

Diagram showing the relationship between overproduction of ROS, NO, and oxidative modifications of SQR in mitochondria during ischemia and reperfusion injury. The physiological conditions of hypoxia and reoxygenation during ischemia and reperfusion trigger overproduction of ROS from the mitochondrial electron transport chain, including complex I and complex III. Oxidative stress induces alterations in the redox state including deglutathionylation of SQR, which moderately increases SQR-derived superoxide generation activity (7). Up-regulation of the iNOS expression and nitrite disproportionation during ischemia/reperfusion trigger NO overproduction (10, 11, 18, 19), which reacts with superoxide produced by the electron transport chain to form peroxynitrite. Peroxynitrite causes oxidative modifications of the SQR 70-kDa subunit with protein tyrosine nitration (Y-NO2). Fum, fumarate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Liwen Zhang and Kari B. Green-Church (Campus Chemical Instrument Center, Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility, The Ohio State University) for analysis in mass spectrometry.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL83237 (to Y.-R. C.) and HL63744 and HL38324 (to J. L. Z.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1-9.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ROS, reactive oxygen species; SQR, succinate

ubiquinone reductase or mitochondrial Complex II; SCR, succinate cytochrome

c reductase or supercomplex containing Complex II and Complex III;

QCR, ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase or Complex III; GS,

S-glutathionylated;

, superoxide anion; NOS,

NO synthase; eNOS, endothelial NOS; iNOS, inducible NOS; OONO-,

peroxynitrite; 3-NT, 3-nitrotyrosine; ETA, electron transport activity;

DEPMPO, 5-diethoxylphosphoryl-5-methyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide; SOD,

superoxide dismutase; MS, mass spectrometry; MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry;

LC, liquid chromatography; Q2, ubiquinone-2; Fmoc,

N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl; DCPIP, dichlorophenol indophenol;

H/RO, hypoxia/reoxygenation; aa, amino acids; MVF, measles virus fusion.

, superoxide anion; NOS,

NO synthase; eNOS, endothelial NOS; iNOS, inducible NOS; OONO-,

peroxynitrite; 3-NT, 3-nitrotyrosine; ETA, electron transport activity;

DEPMPO, 5-diethoxylphosphoryl-5-methyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide; SOD,

superoxide dismutase; MS, mass spectrometry; MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry;

LC, liquid chromatography; Q2, ubiquinone-2; Fmoc,

N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl; DCPIP, dichlorophenol indophenol;

H/RO, hypoxia/reoxygenation; aa, amino acids; MVF, measles virus fusion.

C.-L. Chen and Y.-R. Chen, unpublished observation.

References

- 1.Becker, L. B. (2004) Cardiovasc. Res. 61461 -470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari, R., Ceconi, C., Curello, S., Cargnoni, A., Pasini, E., DeGiuli, F., and Albertini, A. (1991) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 53215S -222S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari, R. (1994) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 36699 -111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrari, R. (1995) Am. J. Cardiol. 7617 -24 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrari, R., Pepi, P., Ferrari, F., Nesta, F., Benigno, M., and Visioli, O. (1998) Am. J. Cardiol. 82 2-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts, J. A., and Kline, J. A. (2003) Acad. Emerg. Med. 10985 -997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, Y. R., Chen, C. L., Pfeiffer, D. R., and Zweier, J. L. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 28232640 -32654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambrosio, G., Zweier, J. L., Duilio, C., Kuppusamy, P., Santoro, G., Elia, P. P., Tritto, I., Cirillo, P., Condorelli, M., and Chiariello, M. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 26818532 -18541 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zweier, J. L., Kuppusamy, P., Williams, R., Rayburn, B. K., Smith, D., Weisfeldt, M. L., and Flaherty, J. T. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 26418890 -18895 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao, X., He, G., Chen, Y. R., Pandian, R. P., Kuppusamy, P., and Zweier, J. L. (2005) Circulation 1112966 -2972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao, X., Chen, Y. R., He, G., Zhang, A., Druhan, L. J., Strauch, A. R., and Zweier, J. L. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2921541 -1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu, X., Liu, B., Zhou, S., Chen, Y. R., Deng, Y., Zweier, J. L., and He, G. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2931442 -1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu, P., Hock, C. E., Nagele, R., and Wong, P. Y. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 272H2327 -H2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, P., and Zweier, J. L. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 27129223 -29230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zweier, J. L., Wang, P., and Kuppusamy, P. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270304 -307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lefer, A. M., Tsao, P. S., Lefer, D. J., and Ma, X. L. (1991) FASEB J. 52029 -2034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsao, P. S., and Lefer, A. M. (1990) Am. J. Physiol. 259H1660 -H1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zweier, J. L., Samouilov, A., and Kuppusamy, P. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1411250 -262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zweier, J. L., Wang, P., Samouilov, A., and Kuppusamy, P. (1995) Nat. Med. 1 804-809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han, Z., Chen, Y. R., Jones, C. I., III, Meenakshisundaram, G., Zweier, J. L., and Alevriadou, B. R. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2921103 -1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagerhall, C. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1320107 -141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]