Abstract

“Oxidized” amides, as represented by acyl aminals and acyl hemiaminals, are integral subunits of several natural products that exhibit useful biological activity. In this manuscript a multicomponent approach to these groups from acylimine intermediates is demonstrated. The acylimines are accessed through a sequence of nitrile hydrozirconation and acylation, making this highly versatile amide synthesis useful for a range of range of applications in target- and diversity-oriented synthesis.

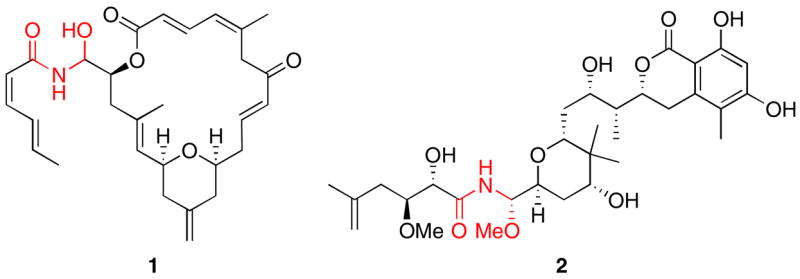

Natural products that contain “oxidized” amides, in which the carbon bonded to the nitrogen atom has an oxidation state that is higher than the usual (+1) level, effect an impressive range of biological responses. These compounds are represented acyl hemiaminals such as the cytotoxins zampanolide1 (1) and tallysomycin,2 and acyl aminals such as the protein synthesis inhibitors psymberin (2)3 and pederin.4 These compounds have evoked substantial synthetic efforts, and several approaches to the synthesis of the oxidized amide groups5 and natural product total syntheses6 have been disclosed. SAR studies have demonstrated that oxidized amides are important for the biological activities of these natural products.7 While these groups have been proposed to serve as latent acyliminium ions8 only one report9 has appeared in the literature that compellingly establishes protein alkylation through Schiff base formation from an enamide, another important class of oxidized amide. In addition to their roles in conferring biological activity, acyl aminals have been used as latent electrophiles in stereoselective carbon–carbon bond forming reactions.10

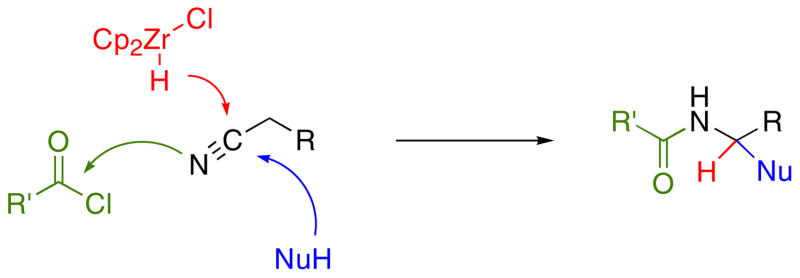

In principle oxidized amide groups can be prepared from acylimine intermediates (Scheme 1), with acyl aminals being accessed through alcohol addition11 and acyl hemiaminals being accessed through water addition. Additionally, enamides could be accessed through tautomerization. This strategy is limited, however, by the dearth of methods for preparing acylimines. Condensation reactions between aldehydes and amides are ineffective when the aldehyde is enolizable. While this problem can be addressed by adding sulfonates to form α-sulfonyl amides,12 regenerating and isolating the acylimine is difficult (though not impossible)13 because of the sensitivity of the intermediates.

Scheme 1.

Oxidized amides from acylimines.

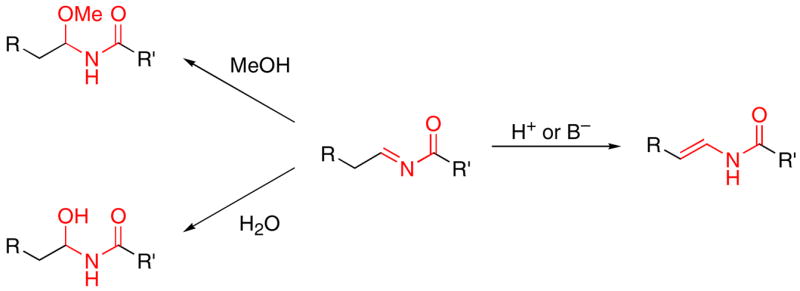

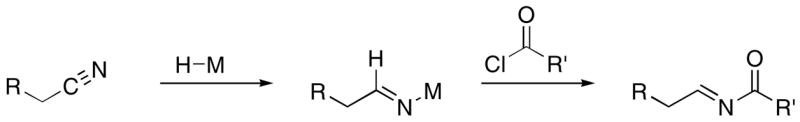

In consideration of our interests in the synthesis of 1, 2, and related structures14 we sought to develop a universal approach to acylimine construction from easily handled precursors and to establish conditions for the preparation of each class of oxidized amide. Acylating metalloimines15 is an attractive approach to acylimine formation (Scheme 2). This route can be executed by preparing metalloimines from selective nitrile hydrometallation followed by acid chloride addition. Given the abundant reactions that have been developed for nitrile synthesis and the relatively inert nature of nitriles (compared to other electrophilic groups) to most reaction conditions, this strategy should be useful in the synthesis of complex natural products. Majoral and coworkers have reported16 that treating sterically hindered nitriles with Schwartz’ reagent (Cp2Zr(H)Cl)17 followed by adding sterically hindered acid chlorides yields isolable acylimines.18 In this manuscript we demonstrate that the sequence of nitrile hydrozirconation, acylation, and nucleophile addition results in a versatile multicomponent approach to oxidized amides.

Scheme 2.

Acylimine formation through nitrile hydrometallation and acylation.

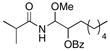

In our initial foray into this method (Scheme 3), we exposed cyanohydrin ether 3, prepared through a BiBr3-mediated addition of TMSCN to the corresponding dimethyl acetal,19 to hydrozirconation, acylation with PhOC(O)Cl, and MeOH addition. Diastereomers 4 and 5 were isolated from the reaction in a 55% combined isolated yield and with a diastereomeric ratio of 2.4:1. This reaction is consistent with the formation of linear18a metalloimine 6, which can undergo acylation to provide an acylimine intermediate. Nucleophilic addition of MeOH can proceed through intermediate 7, in which chelation is enforced through hydrogen bonding with MeOH to form major product 4 or through Felkin-type intermediate 8 to form minor product 5. The stereochemical assignments for 4 and 5 were established through subjecting 9, prepared as a single stereoisomer, to a Curtius rearrangement20 and observing the formation of 5 as the sole product.

Scheme 3.

Acyl aminal formation through nitrile hydrozirconation, and stereochemical assignment through chemical correlation.

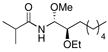

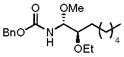

With the initial reactivity patterns established, we turned our attention to studying the scope of the process (Table 1). Ethoxy nitrile 10 served as the substrate for the initial phases of this study. When isobutyroyl chloride is used for the acylation reaction, both CH2Cl2 (entry 1) and THF (entry 2) can be employed as reaction solvents. Interestingly, a modest change in stereoselectivity occurs when the solvent is changed from CH2Cl2 to THF whereby the major product in CH2Cl2 results from chelation control and the major product in THF results from Felkin-type addition.21 The capacity of THF to form hydrogen bonds with MeOH is likely the souce of diminished chelation control. For reactions that are conducted in CH2Cl2, the entire process can be executed in approximately 30 min since the hydrozirconation and acylation steps proceed to completion within a few minutes and the MeOH addition is instantaneous. Chelation control can be improved (dr = 5.7:1) without sacrificing yield by adding a stoichiometric amount of Mg(ClO4)2 following the acylation step and conducting the MeOH addition at −78 °C (entry 3). Notably, the MeOH addition reaction is still instantaneous at −78 °C. Metalloimine acylation with α-methoxy acetyl chloride provides an acyl aminal (entry 4) that is electronically similar to the acyl aminal in psymberin. A readily cleaved carbamate can be accessed through acylation with CbzCl (entry 5). Unfortunately sulfonyl aminals could not be prepared in high yields, as shown in entry 6, with substantial amounts of the aldehyde that results from direct nitrile reduction and hydration being isolated.

Table 1.

Nucleophile and electrophile scope in acyl aminal synthesis.a

| entry | substrate | solvent | electrophile | nucleophile | major product | yield (dr)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

10 |

CH2Cl2 | iPrC(O)Cl | MeOH |

11 |

75% (2:3:1) |

| 2 |

10 |

THF | iPrC(O)Cl | MeOH |

12 |

64% (1:4:1) |

| 3c |

10 |

CH2Cl2Mg(ClO4)2 | iPrC(O)Cl | MeOH |

11 |

71% (5:7:1) |

| 4 |

10 |

CH2Cl2 | MeOCH2C(O)Cl | MeOH |

13 |

69% (1:7:1) |

| 5 |

10 |

CH2Cl2 | CbzCl | MeOH |

14 |

64% (1:5:1) |

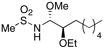

| 6 |

10 |

CH2Cl2 | Ms2O | MeOH |

15 |

24% (2:4:1) |

| 7 |

10 |

CH2Cl2 | iPrC(O)Cl | tBuOH |

16 |

71% (2:0:1) |

| 8 |

10 |

CH2Cl2 | iPrC(O)Cl | PhOH |

17 |

69% (5:6:1) |

| 9 |

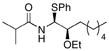

10 |

CH2Cl2 | iPrC(O)Cl | PhSH |

18 |

72% (7:0:1) |

Representative procedure: Cp2Zr(H)Cl (1.2 equiv) was added to a solution of the substrate in the solvent (0.1 M). The mixture stirred for 10 min at rt, then was cooled to 0 °C. The electrophile (1.2–1.5 equiv) was added and stirred for 10 min. The nucleophile (20 equiv) was added and the reaction was stirred for a few additional minutes.

Yields refer to the sum of the yields of the diastereomers.

Nucleophilic addition was conducted at −78 °C.

Nucleophiles other than MeOH also proved to be suitable for the reaction. Steric hindrance does not suppress nucleophilic addition, as demonstrated by the reaction with tBuOH (entry 7), though the major product results from the Felkin-type pathway. Phenol (entry 8) and thiophenol (entry 9) are also suitable nucleophiles, with phenol reacting through the chelation pathway and thiophenol reacting through the Felkin-type pathway, consistent with their relative abilities to engage in hydrogen bonding. In addition to the capacity to reverse the stereochemical outcome of the addition reaction, entry 9 represents an excellent method to prepare latent acyliminium ions that can be revealed through oxidation.22

Structural variations in the nitrile component are also tolerated (Table 2). Benzoylated cyanohydrin 19 can be converted to acyl aminal 20 in 64% yield (entry 1), demonstrating that hydrozirconation can be selective for nitriles in the presence of ester groups.23 In consideration of the acyl hemiaminal in zampanolide, we simply subjected the acylimine from the hydrozirconation of 19 to a direct aqueous work-up and isolated acyl hemiaminal 21 in 54% yield (entry 2). The stereochemical outcomes of the products from 19 were not determined. Nitriles that are not branched at the α-position can serve as substrates for the sequence, though THF is a superior solvent for inhibiting acylimine tautomerization and subsequent oligomerization. Octyl cyanide can be converted to acyl aminal 23 and acyl hemiaminal 24 in yields that are only modestly lower than those that are observed for branched substrates (entries 3 and 4). Aromatic nitriles, while undergoing hydrozirconation substantially more slowly than aliphatic nitriles, are excellent substrates, with acyl aminal 26 being formed in 73% yield.

Table 2.

Nucleophile and electrophile scope in acyl aminal synthesis.a

| entry | substrate | solvent | electrophile | nucleophile | major product | yield (dr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b |

19 |

CH2Cl2 | iPrC(O)Cl | MeOH |

20 |

64% (1.4:1) |

| 2b |

19 |

CH2Cl2 | iPrC(O)Cl | H2O |

21 |

52% (3.0:1) |

| 3 |

22 |

THF | iPrC(O)Cl | MeOH |

23 |

62% |

| 4 |

22 |

CH2Cl2Et3N | iPrC(O)Cl | H2O |

24 |

54% |

| 5 |

25 |

THF | iPrC(O)Cl | MeOH |

26 |

73% |

See Table 1 for representative procedures.

Stereochemical relationships for the major and minor product diastereomers were not determined.

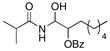

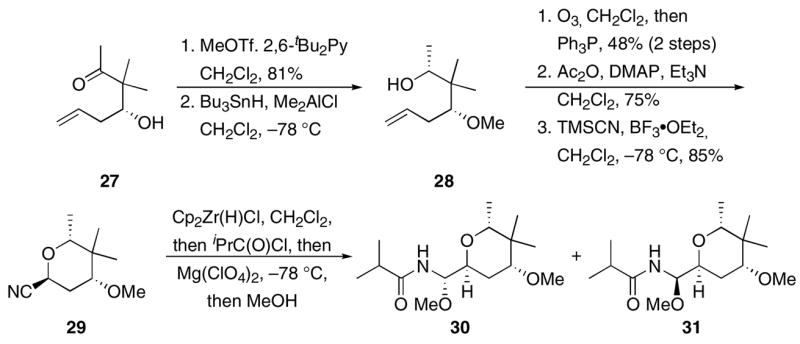

To apply this process in a more complex setting that is relevant to the synthesis of psymberin, pederin, and analogs, we prepared (Scheme 4) nitrile 29 from the known14b ketone 27 through a sequence that employs a Lewis acid-promoted reduction with Bu3SnH24 to establish relative stereocontrol to provide 28. Interestingly, the stereochemical outcome of this reaction does not follow from the chelation-control that is generally observed24 in this procedure. Tetrahydropyran formation through a sequence of ozonolytic alkene cleavage, acylation, and cyanide introduction yielded 29. Hydrozirconation, acylation with isobutyroyl chloride, and MeOH addition in the presence of Mg(ClO4)2 provided acyl aminal 30 in 54% yield, diastereomer 31 in 23% yield, and a small amount (~10%) of the amide that arises from reduction of the intermediate acylimine with the slight excess of Schwartz’ reagent that is used in these reactions. Stereochemical assignments were based on 1H NMR splitting pattern and chemical shift analogies to known compounds25 in the pederin/psymberin family. While chelation controlled addition could not be promoted to the same extent as was observed for 10, the high overall chemical yield and reasonable stereocontrol provide the desired acyl aminal with the desired stereochemical orientation efficiently and with the potential for extensive structural variation. Also notable in this transformation was the absence of epimerization at the carbon that bears the cyano group, indicating that these conditions do not erode the stereochemical purity of cyanohydrin ethers.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of a tetrahydropyranyl acyl aminal.

We have described a one pot multicomponent approach to the synthesis of oxidized amides from nitriles. In consideration of the numerous methods that are available for nitrile preparation, the capacity for variation of the nucleophile, electrophile, and nitrile components, the inherent utility of the products as subunits of numerous biologically active compounds, and the ability to employ the products as starting materials in stereoselective transformations, this process is well-suited for applications in target- and diversity oriented26 synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures for all reactions and characterization data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Figure 1.

Natural products that contain oxidized amides.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM-62924 and P50-GM067082) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-0139851) for generous financial support of this work. M. E. G. was supported through a Novartis Graduate Fellowship. We thank Ms. Sarah Russick and Ms. Liz Dotzel (University of Pittsburgh) for assisance with the early stages of this project.

References

- 1.Tanaka J, Higa T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:5535. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konishi M, Saito K, Numata K, Tsuno T, Asama K, Tsukiura H, Naito T, Kawaguchi H. J Antibiot. 1977;30:789. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.30.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Pettit GR, Xu J, Chapuis J, Pettit RK, Tackett LP, Doubek DL, Hooper JNA, Schmidt JM. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1149. doi: 10.1021/jm030207d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cichewicz RH, Valeriote FA, Crews P. Org Lett. 2004;6:1951. doi: 10.1021/ol049503q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Cardani C, Ghiringhelli D, Mondelli R, Quilico A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1965:2537. [Google Scholar]; (b) Matsumoto T, Yanagiya M, Maeno S, Yasuda S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968:6297. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)98905-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Representative examples: Bayer A, Maier ME. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:6665.Hoye TR, Hu M. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9576. doi: 10.1021/ja035579q.Troast DM, Porco JA., Jr Org Lett. 2002;4:991. doi: 10.1021/ol025558l.Rech JC, Floreancig PE. Org Lett. 2003;5:1495. doi: 10.1021/ol034273l.Sznaidman ML, Hecht SM. Org Lett. 2001;3:2811. doi: 10.1021/ol0101178.Matsuda F, Tomiyoshi N, Yanagiya M, Matsumoto T. Tetrahedron. 1988;44:7063.Hoffmann RW, Schlapbach A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:7903.Kocienski P, Jarowicki K, Marczak S. Synthesis. 1991:1191.

- 6.Representative examples: Smith AB, III, Safonov IG, Corbett RM. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11102. doi: 10.1021/ja020635t.Jiang X, Garcia-Fortanet J, De Brabander JK. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11254. doi: 10.1021/ja0537068.Shangguan N, Kiren S, Williams LJ. Org Lett. 2007;9:1093. doi: 10.1021/ol063143k.Jewett JC, Rawal VH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:6502. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701677.

- 7.(a) Thompson AM, Blunt JW, Munro MHG, Clark BM. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans I. 1994:1025. [Google Scholar]; (b) Petri AF, Sasse F, Maier ME. Eur J Org Chem. 2005:1865. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Hong CY, Kishi Y. J Org Chem. 1990;55:4242. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gentle CA, Bugg TDH. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1999:1279. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie XS, Pardon D, Liao XB, Wang J, Roth MG, De Brabander JK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugiura M, Hagio H, Hirabayashi R, Kobayashi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12510. doi: 10.1021/ja0170448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Rowland GB, Zhang H, Rowland EB, Chennamadhavuni S, Wang Y, Antilla JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15696. doi: 10.1021/ja0533085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang X, Shao N, Palani A, Aslanian R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:1967. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanazawa AM, Denis JN, Greene AE. J Org Chem. 1994;59:1238. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song J, Wang Y, Deng L. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6048. doi: 10.1021/ja060716f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Aubele DL, Wan S, Floreancig PE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:3485. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rech JC, Floreancig PE. Org Lett. 2005;7:4117. doi: 10.1021/ol051396s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Savarin CG, Boice GN, Murry JA, Corley E, DiMichele L, Hughes D. Org Lett. 2006;8:3903. doi: 10.1021/ol061318k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fleming FF, Wei G, Zhang Z, Steward OW. Org Lett. 2006;8:4903. doi: 10.1021/ol0619765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maraval A, Igau A, Donnadieu B, Majoral JP. Eur J Org Chem. 2003:385. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Hart DW, Schwartz J. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:8115. [Google Scholar]; (b) Buchwald SL, LaMaire SJ, Nielsen RB, Watson BT, King SM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:3895. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hunag Z, Negishi E-i. Org Lett. 2006;8:3675. doi: 10.1021/ol061202o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.For other examples of nitrile hydrozirconation, see: Erker G, Frömberg W, Atwood JL, Hunter WE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1984;23:68.Frömberg W, Erker G. J Organomet Chem. 1985;280:343.Anbhaikar NB, Herold M, Liotta DC. Heterocycles. 2004;62:217.

- 19.Komatsu N, Uda M, Suzuki H, Takahashi T, Domae T, Wada M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:7215. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ninomiya K, Shioiri T, Yamada S. Tetrahedron. 1974;30:2151. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stereochemical assignments were based on analogy to 5 and 6 through the remarkably consistent coupling constant patterns in 1H NMR.

- 22.Sugawara M, Mori K, Yoshida J-i. Electrochim Acta. 1997;42:1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.For an overview of the chemoselectivity patterns of Schwartz’ reagent, see: Wipf P, Jahn H. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:12853.

- 24.Evans DA, Allison BD, Yang MG, Masse CE. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10840. doi: 10.1021/ja011337j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang X, Williams N, De Brabander JK. Org Lett. 2007;9:227. doi: 10.1021/ol062656o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schreiber SL. Science. 2000;287:1964. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures for all reactions and characterization data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.