Abstract

Recent advances in genetics and technology have led to breakthroughs in understanding the genes that predispose individuals to autoimmune diseases. A common haplotype of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT4) gene has been shown to be associated with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and primary Sjögren’s syndrome. STAT4 is a transcription factor that transduces interleukin-12, interleukin-23, and type I interferon cytokine signals in T cells and monocytes, leading to T-helper type 1 and T-helper type 17 differentiation, monocyte activation, and production of interferon-γ. Although the evidence for this association is very strong and well replicated, the exact mechanism by which polymorphisms in this gene lead to disease remains unknown. In concert with the identification of other disease-associated loci, elucidating how the variant form of STAT4 modulates immune function should lead to an improved understanding of the pathophysiology of autoimmunity.

Introduction

Although a genetic contribution has long been recognized as a risk factor for the development of autoimmune disease, until the past 5 years, no common genetic factor other than HLA had been reproducibly identified. However, using a variety of new technologies, geneticists are now beginning to unravel some of the elusive pathogenic mechanisms underlying the body’s inability to distinguish self from nonself. As one might expect, disparate diseases with differing clinical outcomes have shown unique genetic risk factors; however, the identification in 2004 of a coding variant in the tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22 as a risk factor for type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Graves’ disease, and myasthenia gravis gave credence to the concept that common genetic risk factors may convey risk to multiple autoimmune diseases and thus shed light on common pathways that underlie these diseases. A newly identified risk factor, a variant haplotype of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT4), has now been associated with RA, SLE, and primary Sjögren’s syndrome. This is an exciting addition to autoimmunity genetics and provides further insight into the pathophysiology underlying these immune regulation disorders.

Advances in the Genetics of Rheumatoid Arthritis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Given the increased familial incidence of RA and SLE and increased disease susceptibility demonstrated in twin studies, RA and SLE both clearly have a genetic component. The relative risk to a sibling for developing disease compared with the general population has been estimated to be between 5 and 10 in seropositive RA and between 20 and 30 in SLE [1]. In the 1980s, the HLA region was shown to be a significant risk factor for the development of both diseases, and one particular combination of HLA DR-β alleles, the shared epitope, was shown to be a particularly strong risk factor for RA [2]. After the discovery of HLA associations, a long period of genetic investigation during the 1990s and early 2000s yielded evidence of additional genetic regions involved in autoimmunity but, with few exceptions, no definitive identification of specific risk genes. Much of this work involved linkage analysis in multiplex families in which particular chromosomal regions were suggested as carrying susceptibility genes but with only modest statistical evidence and quite imprecise information about these genes’ likely location [3,4]. In 2004, with the increasing use of case-control single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) association studies, the PTPN22 R620W polymorphism was unambiguously identified as a risk factor in type 1 diabetes [5] and RA [6]. This association subsequently has been extended to other autoimmune disorders, such as SLE, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Graves’ disease, and myasthenia gravis [7,8]. Whereas the PTPN22 variant showed very strong association with autoimmunity in white populations, it was not polymorphic and therefore not associated with disease in Asian populations. Thus, PTPN22 is the most compelling genetic association that illustrates that common genes underlie diverse forms of autoimmune diseases and that considerable genetic heterogeneity may exist among different racial groups in terms of susceptibility loci.

A major recent addition to the genetic armamentarium has been the development of whole-genome association studies. In this approach, hundreds of thousands of SNP association tests can be performed simultaneously using high-density SNP arrays. This technology has enabled the identification of novel loci that would have been unlikely to be selected as high-priority candidate genes for analysis. In RA, this method has been used to identify the TRAF1/C5 locus [9] and a region at 6q23 near TNFAIP3 [10,11]. In SLE, whole-genome association studies have identified the BLK/C8orf13, PXK, KIAA1542, BANK1, and ITGAM loci [12••,13•,14]. Whole-genome association scans in celiac disease [15] and type 1 diabetes [16] have identified a locus near IL2 and IL21 that has, as a candidate gene, been replicated in RA and may represent another general autoimmunity locus [17]. Thus, we are in the early stages of a new age of genetic discovery in which many new susceptibility loci for autoimmunity are rapidly emerging.

Identification of STAT4 as a risk factor for multiple systemic autoimmune diseases

The identification of STAT4 as a genetic risk factor for RA and SLE emerged from a combination of analytic approaches in which targeted association studies were informed by linkage data. In the case of RA, linkage analysis conducted with a dense panel of SNP markers led to evidence of linkage on chromosome 2q [18]. This large region contained 13 potentially interesting genes, including CTLA4, CD28, CASP8, CASP10, STAT1, and STAT4. Remmers et al. [19••] identified SNPs in these candidate genes and tested them for association in an RA case-control series. A strong signal was discovered in the STAT4 gene at an intronic SNP, rs7574865, which was also in linkage disequilibrium with SNPs in STAT1. Fine mapping was performed over the STAT4/STAT1 region in an independent set of cases and controls and revealed multiple SNPs in the large third intron of STAT4 to be significantly associated with RA. The association was confirmed in an independent North American case-control series. A Swedish cohort was also genotyped for rs7574865 and showed evidence for association. A meta-analysis of the RA case-control series revealed a P value for association of 4.64 × 10−8 with an odds ratio of 1.27 [19••] for having the risk allele in chromosomes of cases versus those of controls (Table 1). A very large, recent British study showed a similar effect for this SNP, with a P value for association of 1.9 × 10−5 and an odds ratio of 1.15 in two case-control collections comprised of 6400 cases and 6422 controls (Table 1) [20•].

Table 1.

Association studies of STAT4 with autoimmune diseases. Allele frequencies and association statistics are given for the disease-associated SNP rs7574865

| Minor allele frequency | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Disease | Ethnicity | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

| Remmers et al. | RA | Caucasian | 3149 | 3516 | 26% | 22% | 4.6*10−8 | 1.27 (1.16–1.37) |

| Barton et al. | RA | Caucasian | 6400 | 6422 | 30% | 26% | 1.9 *10−5 | 1.15 (1.08–1.22) |

| Palomino-Morales et al. | RA | S American | 274 | 421 | 39% | 32% | 0.008 | 1.36 (1.08–1.71) |

| Lee et al. | RA | Asian | 1123 | 1008 | 39% | 33% | 0.0004 | 1.33 (1.10–1.60) |

| Hom et al. | SLE | Caucasian | 1311 | 1783 | 31% | 23% | 9.9*10–14 | 1.51(1.31–1.74) |

| Remmers et al. | SLE | Caucasian | 1039 | 1248 | 31% | 22% | 1.9*10−9 | 1.55 (1.34–1.79) |

| Harley et al. | SLE | Caucasian | 720 | 2337 | 32% | 23% | 2.8*10−9 | 1.50(1.24–1.82) |

| Palomino-Morales et al. | SLE | S American | 144 | 421 | 43% | 32% | 0.0005 | 1.62 (1.22–2.16) |

| Korman et al. | Sjogren’s | Caucasian | 120 | 1143 | 30% | 22% | 0.01 | 1.46(1.09–1.97) |

The 1039 SLE cases reported in Remmers et al. are a subset of the 1380 cases reported in Hom et al.

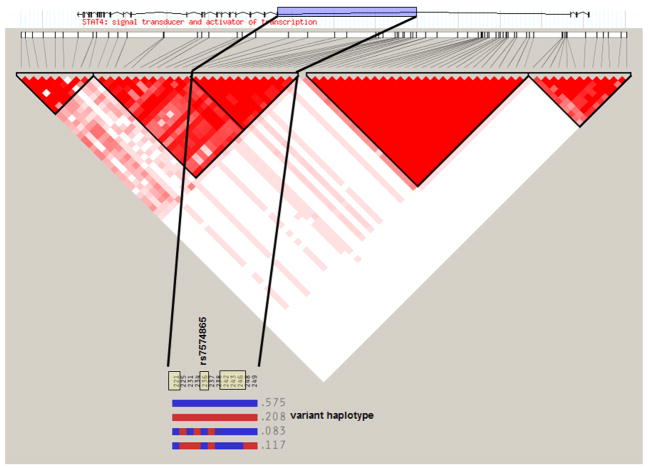

Although rs7574865 in the third intron of STAT4 is the most strongly disease-associated SNP (no other STAT4 SNP independently contributed to disease), it is in strong linkage disequilibrium with at least five other SNPs within that intron, all of which exhibit statistically indistinguishable association with disease. This set of SNPs is inherited together as a haplotype (Fig. 1), and the disease-associated SNPs on this haplotype do not exist on any other STAT4 haplotypes. Therefore, the presence of at least one and possibly all of the SNPs on this haplotype could account for the increased disease risk. Although the disease-associated haplotype is relatively common—with roughly 20% of control chromosomes carrying it—it is not enough to cause disease by itself.

Figure 1.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype map of STAT4 gene. This diagram shows the LD structure (D′) across the 150-kb STAT4 region with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), with greater than 20% minor allele frequency shown in chromosomal order on the x axis and with increasing intensity of fill indicating higher levels of LD between pairs of SNPs (white: D′ = 0; darkest: D′ = 1). The region of the third intron in which disease-associated SNPs are located is highlighted on the gene exon-intron map at the top of the figure. The inset haplotype map shows blocks of SNPs inherited together in an extended STAT4 LD block, with dark shading representing the common and light shading the variant form of each SNP. The frequency of each haplotype in the HapMap CEPH-Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe (CEU) samples is shown. Disease-associated SNPs, including rs7574865, are marked at the top of the haplotype inset and can be found in the variant form only on the second haplotype.

Anti–cyclic-citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies have gained wide use as a more sensitive autoantibody marker for RA than rheumatoid factor. The major genetic risk alleles, including the HLA shared epitope, PTPN22, and the 6q23 locus near TNFAIP3, all have shown significant association with RA marked by these autoantibodies. The TRAF1/C5 association was also found to be stronger in anti-CCP+ RA compared with anti-CCP- RA [21]. An intriguing phenomenon also has been described whereby an additive effect for CCP+ RA is conferred by the presence of the shared epitope, PTPN22, and an environmental risk factor, cigarette smoking [22]. Unlike these other RA genetic risk factors, STAT4 is associated with anti-CCP+ and anti-CCP- disease [19••]; the odds ratio for developing disease is similar in CCP+ and CCP-RA.

Unlike PTPN22, the STAT4 gene has been identified as a risk factor for RA in whites and Asians. A large case-control study of Korean RA showed that despite the risk allele for STAT4 being more common in Asians than in whites (Table 1), there was still an increased susceptibility in those individuals carrying the risk allele that conferred roughly the same odds ratio [23]. Like Asians, South Americans have a higher STAT4 allele frequency, and a recent study showed RA susceptibility in a Colombian population (Table 1) [24].

Because microsatellite linkage scans in SLE had also identified the 2q region [25] and suspicion that these diseases may share more risk alleles in addition to PTPN22, the STAT1/STAT4 region associated with RA was assayed in three SLE case-control series [19••]. The association not only replicated in multiple SLE collections but was shown to be more robust in SLE, with a P value for association of 1.87 × 10−9 and an odds ratio of 1.55 (Table 1). A whole-genome association study that used largely the same SLE cases (but added 341 additional cases and 2092 additional controls) confirmed this finding [13•]. A second large whole-genome association scan with multiple entirely independent sets of cases found a nearly identical association between STAT4 and SLE, with a P value for association of 2.8 × 10−9 and an odds ratio of 1.5 [12••]. Although smaller, a Colombian study has also demonstrated a statistically significant SLE association (Table 1) [24].

The most strongly associated STAT4 SNP recently has been shown to be associated with more severe disease characteristics among SLE patients. Specifically, the disease-associated STAT4 SNP, rs7574865, and the variant STAT4 haplotype on which it is found were shown to be very strongly associated with SLE characterized by poor prognostic subphenotypes, including severe nephritis, double-stranded DNA autoantibodies, and age at diagnosis less than 30 years [26].

Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disease characterized by salivary and lacrimal gland failure. It shares many clinical characteristics with RA and SLE, and a class of patients has an overlap of these conditions termed secondary Sjögren’s syndrome. In a recent study, primary Sjögren’s syndrome was also shown to be associated with the variant haplotype of STAT4 tagged by rs7574865 [27]. Although there have been three reports of association between SNPs in STAT4 and asthma in Chinese and Korean populations [28–30], these studies have found modest effects, and none has evaluated the RA-, SLE-, and Sjögren’s syndrome–associated SNPs located in the gene’s third intron. Further investigation is necessary to determine whether the common susceptibility allele identified in three rheumatologic autoimmune diseases will extend to asthma.

STAT4: An important regulator of adaptive immunity

STAT4 is a member of the STAT family of molecules, which localize to the cytoplasm, can be phosphorylated by membrane-bound receptors, dimerize, and translocate to the nucleus, where they differentially regulate gene expression [31]. Whereas some STATs are relatively ubiquitous in their expression, STAT4 seems to be restricted to testis, lymphoid, and myeloid tissue. Most of the immune system studies involving STAT4 have focused on T cells, in which STAT4 has been shown to be induced by interleukin-12, interleukin-23, and type 1 interferons, leading to the production of interferon- and interleukin-17. As such, STAT4 is seen as an important player in directing helper T cells toward the proinflammatory T-helper type 1 and T-helper type 17 lineages [32].

Transgenic STAT4 knockout mice have been created and are viable [33]. They have impaired T-helper type 1 differentiation, interferon-γ production, and cell-mediated immunity and as a result are very susceptible to infections, including intracellular parasites and mycobacteria [32]. These knockout mice have more severe nephritis and worse mortality in the lupus-like New Zealand mixed 2328 and 2410 murine models [34,35] but have less severe disease in proteoglycan-induced arthritis [36] and less airway inflammation in murine models of asthma [37]. Reports with collagen-induced arthritis have been mixed based on the mouse’s genetic background [38,39]. Antisense oligonucleotides directed at STAT4 can ameliorate collagen-induced arthritis in mice [38,40,41].

Mechanisms by which genetic variation in STAT4 may contribute to predisposition to autoimmunity

The genetic associations with STAT4 involve SNP variants located within the gene’s third intron. Preliminary data do not suggest that these changes have an influence on the level of gene expression. There are at least three described alternatively spliced forms of STAT4; however, little work has been done to characterize their expression or activity, and none of the known disease-associated SNPs would be predicted to influence their production. Nevertheless, neither expression nor splice variation of STAT4 has been studied exhaustively in the context of this newly defined STAT4 risk haplotype. Thus, variants located in the large STAT4 intron could influence the gene’s transcription rate by disrupting a transcription factor binding site or a binding site for modified histone proteins. It is also quite possible that there are more disease-associated SNPs in the variant haplotype, potentially even SNPs outside the third intron of STAT4, that have yet to be identified and that may have functional consequences. The only way to identify such a novel SNP is via complete resequencing of the disease-associated STAT4 region.

Although a variant haplotype of STAT4 and possibly multiple polymorphisms found within it are important in predisposing toward RA and SLE, the part of the immune system in which the dysfunction actually occurs is not yet evident. STAT4 is expressed in B and T lymphocytes, natural killer cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells [42,43]. Although T cells and CD4+ T cells in particular seem to be the most likely culprits by the role of STAT4 in promoting these cells to differentiate into inflammatory subsets, variant STAT4 in other cell subsets may also contribute to disease progression by increasing inflammatory cytokines, preventing apoptosis, presenting autoantigens, or producing autoantibodies.

STAT4 is now a member of the growing list of genes with relatively common polymorphisms that have been implicated in predisposition to autoimmune disease and one of the few implicated as a “general autoimmune disease susceptibility” locus. That nearly all of the genes strongly implicated in multiple autoimmune diseases play important roles in immunity is exciting and has led many to believe that there are common pathways that these diseases share.Identifying these loci may prove to be informative in predicting who will develop disease or particular manifestations; however, even if this is not possible due to the complexities of genetic diversity and environmental risk factors, identifying these molecules and pathways informs our knowledge of the pathophysiology of these diseases and provides a place from which to develop novel therapeutic agents.

Conclusions

Recent advances in genetics and technology have enabled the identification of many new susceptibility loci in complex diseases, including RA and SLE. The identification of an association of STAT4 polymorphisms with both of these diseases has identified this vital transcription factor as a potential general autoimmunity gene. Although the association is robust, it has been replicated numerous times in different populations, and the STAT4 molecule seems to be a great candidate for promotion of autoimmunity, we do not yet know how intronic SNPs in STAT4 cause immune dysregulation and autoimmunity. Future studies will need to examine the different possible mechanisms by which the variant haplotype contributes to disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NO1-AR-2-2263 and RO1 AR44422 awards to PKG and by the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. BDK was supported by the NIH Clinical Research Program, a public private partnership between the Foundation for the NIH and Pfizer, Inc.

Contributor Information

Benjamin D. Korman, National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and NIH Clinical Research Training Program, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 9 Memorial Dr., NIH Bldg 9, Room 1W108, Bethesda, MD 20892, Phone: (301) 496-3373, Fax: (301) 480-2490, kormanb@mail.nih.gov.

Daniel L. Kastner, Daniel L. Kastner, National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, 10 Center Dr., NIH Bldg 10, Room 6N204, Bethesda, MD 20892, Phone: (301) 496-8364, Fax: (301) 402-0012, kastnerd@mail.nih.gov.

Peter K. Gregersen, Peter K. Gregersen, The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, 350 Community Dr., Rm 217, Manhasset, NY 11030, Phone: (516) 562-1134, Fax: (516) 562-1153, peterg@NSHS.edu.

Elaine F. Remmers, National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, 9 Memorial Dr., NIH Bldg 9, Room 1W108, Bethesda, MD 20892, Phone: (301) 496-3373, Fax: (301) 480-2490 remmerse@mail.nih.gov.

References

• Of importance.

•• Of major importance.

- 1.Vyse TJ, Todd JA. Genetic analysis of autoimmune disease. Cell. 1996;85(3):311–318. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goronzy J, Weyand CM, Fathman CG. Shared T cell recognition sites on human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen class II molecules of patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1986;77(3):1042–1049. doi: 10.1172/JCI112358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harley JB, Kelly JA, Kaufman KM. Unraveling the genetics of systemic lupus erythematosus. Springer seminars in immunopathology. 2006;28(2):119–130. doi: 10.1007/s00281-006-0040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jawaheer D, Seldin MF, Amos CI, Chen WV, Shigeta R, Monteiro J, Kern M, Criswell LA, Albani S, Nelson JL, et al. A genomewide screen in multiplex rheumatoid arthritis families suggests genetic overlap with other autoimmune diseases. American journal of human genetics. 2001;68(4):927–936. doi: 10.1086/319518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bottini N, Musumeci L, Alonso A, Rahmouni S, Nika K, Rostamkhani M, MacMurray J, Meloni GF, Lucarelli P, Pellecchia M, et al. A functional variant of lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase is associated with type I diabetes. Nature genetics. 2004;36(4):337–338. doi: 10.1038/ng1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begovich AB, Carlton VE, Honigberg LA, Schrodi SJ, Chokkalingam AP, Alexander HC, Ardlie KG, Huang Q, Smith AM, Spoerke JM, et al. A missense single-nucleotide polymorphism in a gene encoding a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. American journal of human genetics. 2004;75(2):330–337. doi: 10.1086/422827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vang T, Miletic AV, Bottini N, Mustelin T. Protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22 in human autoimmunity. Autoimmunity. 2007;40(6):453–461. doi: 10.1080/08916930701464897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyogoku C, Langefeld CD, Ortmann WA, Lee A, Selby S, Carlton VE, Chang M, Ramos P, Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, et al. Genetic association of the R620W polymorphism of protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22 with human SLE. American journal of human genetics. 2004;75(3):504–507. doi: 10.1086/423790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plenge RM, Seielstad M, Padyukov L, Lee AT, Remmers EF, Ding B, Liew A, Khalili H, Chandrasekaran A, Davies LR, et al. TRAF1-C5 as a risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis--a genomewide study. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357(12):1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plenge RM, Cotsapas C, Davies L, Price AL, de Bakker PI, Maller J, Pe’er I, Burtt NP, Blumenstiel B, DeFelice M, et al. Two independent alleles at 6q23 associated with risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature genetics. 2007;39(12):1477–1482. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomson W, Barton A, Ke X, Eyre S, Hinks A, Bowes J, Donn R, Symmons D, Hider S, Bruce IN, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis association at 6q23. Nature genetics. 2007;39(12):1431–1433. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12••.Harley JB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, Jacob CO, Kimberly RP, Moser KL, Tsao BP, Vyse TJ, Langefeld CD. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nature genetics. 2008;40(2):204–210. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. This study reports a whole genome association study followed by multiple replications in SLE. In addition to novel susceptibility loci ITGAM, KIAA1542, and PXK, the study convincingly replicated STAT4 association with SLE in an independent set of cases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13•.Hom G, Graham RR, Modrek B, Taylor KE, Ortmann W, Garnier S, Lee AT, Chung SA, Ferreira RC, Pant PV, et al. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358(9):900–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. This whole genome association study in SLE confirmed a STAT4 association and also identified the ITGAM and C8Orf113-BLK loci after correction for population stratification. The individuals included in this case-control collection include those used to identify the SLE STAT4 signal reported in reference 19 as well as additional independent samples. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozyrev SV, Abelson AK, Wojcik J, Zaghlool A, Linga Reddy MV, Sanchez E, Gunnarsson I, Svenungsson E, Sturfelt G, Jonsen A, et al. Functional variants in the B-cell gene BANK1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature genetics. 2008;40(2):211–216. doi: 10.1038/ng.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Heel DA, Franke L, Hunt KA, Gwilliam R, Zhernakova A, Inouye M, Wapenaar MC, Barnardo MC, Bethel G, Holmes GK, et al. A genome-wide association study for celiac disease identifies risk variants in the region harboring IL2 and IL21. Nature genetics. 2007;39(7):827–829. doi: 10.1038/ng2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447(7145):661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhernakova A, Alizadeh BZ, Bevova M, van Leeuwen MA, Coenen MJ, Franke B, Franke L, Posthumus MD, van Heel DA, van der Steege G, et al. Novel association in chromosome 4q27 region with rheumatoid arthritis and confirmation of type 1 diabetes point to a general risk locus for autoimmune diseases. American journal of human genetics. 2007;81(6):1284–1288. doi: 10.1086/522037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amos CI, Chen WV, Lee A, Li W, Kern M, Lundsten R, Batliwalla F, Wener M, Remmers E, Kastner DA, et al. High-density SNP analysis of 642 Caucasian families with rheumatoid arthritis identifies two new linkage regions on 11p12 and 2q33. Genes and immunity. 2006;7(4):277–286. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19••.Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, Graham RR, Hom G, Behrens TW, de Bakker PI, Le JM, Lee HS, Batliwalla F, et al. STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357(10):977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073003. This was the first study to identify the association of STAT4 variants with both RA and SLE. The study used evidence from a genetic linkage peak on chromosome 2q to do an association study with candidate genes in that region and the STAT1/STAT4 region was identified. Fine mapping revealed that a STAT4 SNP, rs7574865, and a common haplotype were strongly disease-associated. Because a chromosome 2q linkage peak was also present in SLE, the analysis was extended to SLE case control collections and rs7574865 was shown to be SLE-associated as well. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20•.Barton A, Thomson W, Ke X, Eyre S, Hinks A, Bowes J, Gibbons L, Plant D, Wilson AG, Marinou I, et al. Re-evaluation of putative rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility genes in the post-genome wide association study era and hypothesis of a key pathway underlying susceptibility. Hum Mol Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn128. This large replication study tested the STAT4 and TRAF1/C5 associations in RA in a very large British case-control collection. While the odds ratio for STAT4 was somewhat more modest, the evidence for association was very significant. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurreeman FA, Padyukov L, Marques RB, Schrodi SJ, Seddighzadeh M, Stoeken-Rijsbergen G, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Allaart CF, Verduyn W, Houwing-Duistermaat J, et al. A candidate gene approach identifies the TRAF1/C5 region as a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS medicine. 2007;4(9):e278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kallberg H, Padyukov L, Plenge RM, Ronnelid J, Gregersen PK, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Toes RE, Huizinga TW, Klareskog L, Alfredsson L. Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions involving HLA-DRB1, PTPN22, and smoking in two subsets of rheumatoid arthritis. American journal of human genetics. 2007;80(5):867–875. doi: 10.1086/516736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HS, Remmers EF, Le JM, Kastner DL, Bae SC, Gregersen PK. Association of STAT4 with Rheumatoid Arthritis in the Korean population. Mol Med. 2007 doi: 10.2119/2007-00072.Lee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palomino-Morales RJ, Rojas-Villarraga A, Gonzalez CI, Ramirez G, Anaya JM, Martin J. STAT4 but not TRAF1/C5 variants influence the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus in Colombians. Genes and immunity. 2008 doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantor RM, Yuan J, Napier S, Kono N, Grossman JM, Hahn BH, Tsao BP. Systemic lupus erythematosus genome scan: support for linkage at 1q23, 2q33, 16q12–13, and 17q21–23 and novel evidence at 3p24, 10q23–24, 13q32, and 18q22–23. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2004;50(10):3203–3210. doi: 10.1002/art.20511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor KE, Remmers E, Lee A, Ortmann W, Plenge RM, Tian C, Chung SAJN, Hom G, Kao AH, et al. Specificity of the STAT4 Genetic Association with Severe Disease Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. PLoS Genetics. 2008 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000084. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korman BD, Alba MI, Le JM, Alevizos I, Smith JA, Nikolov NP, Kastner DL, Remmers EF, Illei GG. Variant form of STAT4 is associated with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Genes and immunity. 2008 doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Wu B, Xiong H, Zhu C, Zhang L. Polymorphisms of STAT-6, STAT-4 and IFN-gamma genes and the risk of asthma in Chinese population. Respiratory medicine. 2007;101(9):1977–1981. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pykalainen M, Kinos R, Valkonen S, Rydman P, Kilpelainen M, Laitinen LA, Karjalainen J, Nieminen M, Hurme M, Kere J, et al. Association analysis of common variants of STAT6, GATA3, and STAT4 to asthma and high serum IgE phenotypes. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2005;115(1):80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park BL, Cheong HS, Kim LH, Choi YH, Namgoong S, Park HS, Hong SJ, Choi BW, Lee JH, Park CS, et al. Association analysis of signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT4) polymorphisms with asthma. Journal of human genetics. 2005;50(3):133–138. doi: 10.1007/s10038-005-0232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horvath CM. STAT proteins and transcriptional responses to extracellular signals. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2000;25(10):496–502. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watford WT, Hissong BD, Bream JH, Kanno Y, Muul L, O’Shea JJ. Signaling by IL-12 and IL-23 and the immunoregulatory roles of STAT4. Immunological reviews. 2004;202:139–156. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grusby MJ. Stat4- and Stat6-deficient mice as models for manipulating T helper cell responses. Biochemical Society transactions. 1997;25(2):359–360. doi: 10.1042/bst0250359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacob CO, Zang S, Li L, Ciobanu V, Quismorio F, Mizutani A, Satoh M, Koss M. Pivotal role of Stat4 and Stat6 in the pathogenesis of the lupus-like disease in the New Zealand mixed 2328 mice. J Immunol. 2003;171(3):1564–1571. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh RR, Saxena V, Zang S, Li L, Finkelman FD, Witte DP, Jacob CO. Differential contribution of IL-4 and STAT6 vs STAT4 to the development of lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 2003;170(9):4818–4825. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finnegan A, Grusby MJ, Kaplan CD, O’Neill SK, Eibel H, Koreny T, Czipri M, Mikecz K, Zhang J. IL-4 and IL-12 regulate proteoglycan-induced arthritis through Stat-dependent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2002;169(6):3345–3352. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Behera AK, Kumar M, Lockey RF, Mohapatra SS. Adenovirus-mediated interferon gamma gene therapy for allergic asthma: involvement of interleukin 12 and STAT4 signaling. Human gene therapy. 2002;13(14):1697–1709. doi: 10.1089/104303402760293547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hildner KM, Schirmacher P, Atreya I, Dittmayer M, Bartsch B, Galle PR, Wirtz S, Neurath MF. Targeting of the transcription factor STAT4 by antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides suppresses collagen-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2007;178(6):3427–3436. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nandakumar KS, Holmdahl R. Arthritis induced with cartilage-specific antibodiesis IL-4-dependent. European journal of immunology. 2006;36(6):1608–1618. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klinman DM, Gursel I, Klaschik S, Dong L, Currie D, Shirota H. Therapeutic potential of oligonucleotides expressing immunosuppressive TTAGGG motifs. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2005;1058:87–95. doi: 10.1196/annals.1359.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shirota H, Gursel M, Klinman DM. Suppressive oligodeoxynucleotides inhibit Th1 differentiation by blocking IFN-gamma- and IL-12-mediated signaling. J Immunol. 2004;173(8):5002–5007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thierfelder WE, van Deursen JM, Yamamoto K, Tripp RA, Sarawar SR, Carson RT, Sangster MY, Vignali DA, Doherty PC, Grosveld GC, et al. Requirement for Stat4 in interleukin-12-mediated responses of natural killer and T cells. Nature. 1996;382(6587):171–174. doi: 10.1038/382171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fukao T, Frucht DM, Yap G, Gadina M, O’Shea JJ, Koyasu S. Inducible expression of Stat4 in dendritic cells and macrophages and its critical role in innate and adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. 2001;166(7):4446–4455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]