Abstract

The Wnt family of secreted glycoproteins has been implicated in many aspects of development, but its contribution to blood cell formation is controversial. We over-expressed Wnt3a, Wnt5a and Dkk1 in stromal cells from osteopetrotic mice and used them in co-culture experiments with highly enriched stem and progenitor cells. The objective was to learn if and how particular stages of B lymphopoiesis are responsive to these Wnt family ligands. We found that canonical Wnt signaling, through Wnt3a, inhibited B and pDC but not cDC development. Wnt5a, which can oppose canonical signaling or act through a different pathway, increased B lymphopoiesis. Responsiveness to both Wnt ligands diminished with time in culture and stage of development. That is, only hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and very primitive progenitors were affected. While Wnt3a promoted retention of HSC markers, cell yields and dye dilution experiments indicated it was not a growth stimulus. Other results suggest that lineage instability results from canonical Wnt signaling. Lymphoid progenitors rapidly down-regulated RAG-1 and some acquired stem cell staining characteristics as well as myeloid and erythroid potential when exposed to Wnt3a producing stromal cells. We conclude that at least two Wnt ligands can differentially regulate early events in B lymphopoiesis, affecting entry and progression in distinct differentiation lineages.

Introduction

More than a decade ago it was shown that Wnt ligands and their frizzled receptors are expressed in hematopoietic tissues, where they appeared to function as growth factors (1,2). Subsequent studies implicated them in many other aspects of blood cell formation, and particularly exciting were reports that they can be exploited to propagate stem cells in culture (3–5). However, many questions remain about the importance of particular ones to immune system development in normal adults.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) are normally very rare and are thought to spend most of their time in a quiescent state while residing in specialized stromal cell containing niches (6). Through mechanisms that are only partially understood, the integrity of stem cells is retained throughout life. That is, they maintain competence to self-renew and to generate progenitors capable of making billions of blood cells each day. Stem cells are heterogeneous, and our study focused on Thy1.1 low, RAG1/GFP negative HSC enriched among the small lineage marker negative, Sca-1 positive, c-Kit high (LSK) fraction of bone marrow. HSC give rise to multipotent progenitors and several types of lineage specified cells. For example, early lymphoid progenitors (ELP) can be identified in RAG1/GFP knock-in reporter mice and represent the most primitive cells with high potency to produce lymphocytes (7,8). ELP retain some potential for generating non-lymphoid cells, but this is reduced still further in the common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) to which they give rise. CLP are enriched in the Lin− RAG-1/GFP+ Sca-1+ c-KitLo pro-lymphocyte (ProL) fraction of bone marrow (7). We have now studied these and other well characterized hematopoietic cells in relation to Wnt signaling.

The 19 Wnt ligands are 350–450 amino acids in length and express conserved cysteines as well as sites for N-glycosylation or palmitoylation (9). These modifications guide the shape and hydrophobicity as well as extracellular stability, distribution and activity of Wnts. Extracellular matrix interactions help to create Wnt activity gradients corresponding to expression levels of Wnt target genes in the responding cells that establish and modulate developmental patterns (10). Wnt signal transduction commences after ligand interaction with membrane-associated Wnt receptors. There are at least 10 seven-pass trans-membrane Frizzled (Fzd) receptors, 2 low-density lipoprotein receptor- related proteins (LRP) and a number of extracellular Wnt-modulating proteins such as Kremen, Dickkopf (Dkk), Wnt-inhibitory factor (WIF), secreted Fzds (SFRP) and Norrin (10–12). Depending on the type of ligand-receptor interaction, the presence of intracellular signaling components and the target cell, three Wnt signaling pathways have been identified. The canonical pathway that has been most studied results in stabilization and nuclear translocation of β-catenin. The Wnt-Fzd-LRP5/6 receptor complex activates intracellular Dishevelled (Dsh) that inhibits a complex of proteins including Axin, glycogen synthase kinase 3-β (GSK3), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and casein kinase (CK). This complex normally binds cytosolic β-catenin and targets it for destruction. Stabilized β-catenin translocates to the nucleus where it interacts with transcription factors such as TCF and LEF. The two non-canonical pathways, Wnt-Ca2+ and Wnt-JNK, do not stabilize β-catenin pools. In these cases, Wnt-Fzd interactions activate membrane associated G protein complexes and Dsh to either increase intracellular Ca2+ levels through inositol-3-phosphate (IP3) or induce the JNK pathway through Rho/Rac GTPases. As a result of those events, non-canonical signals can influence actin-dependent cytoskeletal reorganization (13).

Recombinant Wnt proteins and manipulation of Wnt pathway intermediates have been used to artificially expand HSC or progenitors (1,4,5,14,15). For example, HSC of BCL-2 transgenic mice increased more than 100 fold and retained primitive characteristics when transduced with stable β-catenin (5). Furthermore, HSC were able to reconstitute all hematopoietic cells when exposed to recombinant Wnt3a for extended periods in culture and then transplanted (4). Reciprocally, retrovirally-introduced Axin inhibited HSC expansion in culture. GSK3 specific inhibitors that stabilize cellular β-catenin were also used to conclude that canonical signaling can enhance engraftment and repopulation ability of stem cells (14). The resulting stabilization of β-catenin resulted in cross-talk between Wnt, Sonic Hedgehog and Notch pathways. Other studies suggest Wnt contributes to the earliest hematopoiesis in embryos (16), and Vav-directed deletion of β-catenin compromised stem cell competence in adults (17). In additional studies, primitive properties were retained or re-acquired by hematopoietic cells receiving Wnt signals (4,15,18). Transgenic mice with strong constitutive β-catenin cassettes experienced marrow failure, possibly because stem cell differentiation was inhibited (19,20). Inhibition of human B lymphopoiesis in culture by over-stimulation with Wnt3a might be interpreted the same way (21). In contrast to these findings, adult loss of function experiments have not demonstrated a clear requirement for Wnt signals in maintaining stem cell integrity in normal mice (22–24). As a possible explanation, one report concluded that simultaneous deletion of β- and γ-catenin genes was not sufficient to ablate all Wnt signaling (24).

Most of the studies noted above pertained to the canonical Wnt pathway. B lymphopoiesis was abnormal in mice whose Wnt5a gene was targeted, and Wnt5a appeared to signal via the non-canonical Wnt/Ca++ pathway to suppress cyclin D1 and interfere with pro-B responses to IL-7 (25). Lymphopoietic abnormalities were intrinsic to hematopoietic cells in Wnt5a−/− mice, even though BM stroma of recipient mice expressed this factor. Further, thymocytes, and distal limb buds from Wnt5a−/− mice show increased canonical signaling, suggesting that Wnt5a opposes this pathway in normal situations (26,27). Another recent study concluded that Wnt5a can antagonize Wnt3a responses and maintain stem cells in a quiescent G0 state (28). B cell defects and other abnormalities were reported in Fzd9 deficient mice, but no particular signaling pathway was implicated (29).

A case has also been made for Wnt contributions to T lymphopoiesis (26,30–37). As just one example, over-expression of the Wnt antagonist Dkk1, which prevents ligand-Fzd interaction, blocked T cell formation in fetal thymic organ cultures and blocked development at the double negative-1 (DN1) stage (33).

Thus, it is widely believed that Wnts help to maintain “stemness” of HSC, restricting and perhaps even reversing cellular differentiation while allowing a degree of replication. On the other hand, some Wnts may induce differentiation of B and T lymphoid cells. Given the complexity of Wnt related proteins and signaling pathways, much more information is needed about processes that utilize them. We have now exploited culture models to probe additional aspects of Wnt and focused on discrete early events in B lymphopoiesis. Wnt3a and Wnt5a were selected as prototypical agonists for canonical and non-canonical signaling, respectively. Our experiments suggest that such Wnts can deliver opposing cues to primitive cells, restricting or promoting lineage progression. As with other developmental systems, Wnt can participate in cell fate decisions, a capacity that might be harnessed for regenerative medicine.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All mice were bred and maintained in the OMRF Laboratory Animal Resource Center (LARC). RAG1/GFP reporter knock-in mice have been described before (38,39). Heterozygous F1 RAG1/GFP mice, C57BL6 (B6; CD45.2 alloantigen), B6-Thy1.1 (PL) and B6-BCL-2 mice, were bred and maintained in the LARC. B6-RAG1/GFP mice were crossed with B6-Thy1.1 knock-in mice to produce animals expressing Thy1.1, RAG1/GFP, and the CD45.2 alloantigen (RAG1/PL). Bcl-2 transgenic mice were previously described (40).

Isolation of cell populations

Bone marrows from adult, 3–5 months old, RAG1/PL, C57BL6 or B6-BCL-2 mice were flushed from femurs, tibias and humeri in PBS containing 3% fetal calf serum (FCS). Stem and progenitor cells were isolated as follows, after ACK lysis and treatment with Fc-γ-receptor blocking antibody (2.4G2). These cells were enriched from the BM by incubating with antibodies to lineage markers CD19 (1D3) and CD45R/B220 (RA3/6B2) for B-lineage cells, CD11b/Mac-1 (M1/70) and Gr1 (RB6-8C5) for myeloid lineage cells, Ter119 (Ly-76) for erythroid cells, and CD3 (CD3-ε chain) for T-lineage cells followed by the magnetic separation of the positively stained cells by BioMag goat anti–rat IgG system (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). These partially lineage-depleted cells were then washed and stained with biotin-anti-lineage markers (CD19, CD45R/B220, Mac-1, Gr-1, Ter119, CD3, CD8 (Ly-2), and NK1.1 (NKR-P1B and NKR-P1C), APC -anti-c-Kit (2B8), PE-Cy5-anti-Sca-1 (D7, eBioscience) and PE-Cy7- anti-Thy1.1 (HIS51, eBioscience). The HSC fraction was obtained from Lin− RAG1/GFP− c-KitHi Sca-1+ Thy1.1Low, ELP were sorted as Lin− RAG1/GFP+ c-KitHi Sca-1+ Thy1.1− and ProL were sorted as Lin− RAG1/GFP+ c-KitLow Sca-1+ Thy1.1−. The CMP population was defined as Lin− RAG1/GFP− c-KitHi Sca-1− Thy1.1−. For Pre-pro-B isolation, cells were stained and sorted as biotin-anti-lineage− (Mac-1, Gr-1, Ter119, CD3, CD8, and NK1.1), PE-anti-CD19− and APC-anti- CD45R/B220+. LSK from C57-BL6 or BCL-2 mice were isolated from Lin− c-KitHi Sca-1+ gated population. Biotin conjugated antibodies were then stained with fluorochrome-Streptavidin (Caltag Labs, Burlingame, CA). Unless otherwise mentioned, all antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences. Propidium Iodide (PI) was used in all isolations to stain for dead cells. Cells were sorted on either FACSAria (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) or MoFlo (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) flow cytometers. Post-sort analyses confirmed isolation purities, and typically >93% purity were obtained after double sorting.

Retrovirus production and transduction

Wnt3a, Wnt5a (25) (gift from Dr. S. Jones, Univ. of Massachusetts, USA) or Dkk1 plasmids were individually cloned into the MCS of LZRS-IRES-GFP retroviral vector by restriction digestion and ligation reactions. These inserted and empty (control) vectors (See Figure 2a) were transduced into Plat-E (41) virus packaging cell line (gift from Dr. Mark Coggeshall’s laboratory, OMRF, USA) by FuGENE 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) method, and transduced cells were selected by 1μg/ml Puromycin, 10μg/ml Blasticidin, and by sorting for GFP+ transduced cells. Virus containing supernatants were harvested 20 hrs after changing to fresh media [X-VIVO 15 medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) containing 1% detoxified BSA (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC), 2 mM L-glutamine, 5 X 10−5 M 2-ME, 100 U/ml Penicillin and 100 mg/ml Streptomycin] and used immediately for transduction, or stored at −70°C for later use.

Figure 2.

Wnt family ligands differentially regulate the production of lymphoid-lineage cells. (A) Wnt3a, Wnt5a or Dkk1 were individually inserted into a IRES-GFP vector. Contour plots (B) show development of HSC after 11days of co-culture on the indicated Wnt family protein secreting cell lines. B-lineage cells are gated as CD19+ B220+, pDC (plasmacytoid dendritic cells) are within the CD11c+ CD11b− gate of CD19− B220+cells and cDC (conventional DC) are within the CD11c+ CD11b+ gate of CD19− B220− cells as indicated. (C) Total cell yields per input progenitor were calculated and given as averages with S.E. bars. Shown is one representative experiment of four that produced similar results. Asterisks indicate statistical significance, * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01), *** (p<0.0001).

For transduction of stem cells (isolated from B6 mice), 100,000 sorted LSK (HSC-enriched cells) were deposited into a well of a 48-well dish. Cells were immediately transduced with the virus media in the presence of 20 ng/ml recombinant mouse stem cell factor (SCF), 100 ng/ml Flk2/Flt3 ligand (FL), 20 ng/ml Thrombopoietin (TPO) and 16μg/ml Polybrene (Chemicon, Tennecula, CA) followed by incubation at 37°C for 14–16 hrs. Subsequently, spin transduction was conducted in a centrifuge at 32°C (1500 rpm) for 1.5 hr and cells were additionally incubated at 37°C for 5 hr. Culture medium was then replaced with fresh medium containing virus supernatant, growth factors, polybrene, and re-incubated. A second spin transduction was performed 8 hrs later followed by supplementing with fresh culture medium containing the cytokines defined above. After an additional 20 hrs, GFP+ cells were purified by sorting on MoFlo cell sorter while gating out dead cells. All cytokines were purchased from R&D Systems Inc. (Minneapolis, MN).

For transduction of OP9 stromal cells, Plat-E virus producing cells were grown on OP9 cellular media for 20hrs. Supernatant was then harvested, supplemented with 20μg/ml Polybrene and used to infect OP9 cells. After 18hrs incubation, virus media was changed with fresh, supplemented with Polybrene and re-incubated for additional 18 hrs. Cells were then sorted for GFP+ transduced for 4 generations on MoFlo cell sorter, and stable GFP+ OP9-LZR (empty vector transduced), OP9-W3A (Wnt3a transduced), OP9-W5A (Wnt5a transduced) and OP9-Dkk1 (Dkk1 transduced) cell lines were generated. Transduced stromal cells secreted the expected factor and this was confirmed by western blotting (data not shown). We also determined that the Dkk1 secreted from OP9-Dkk1 was biologically active. That is, it countered the influence of Wnt3a on stromal cell expression of adhesion molecules (manuscript in preparation).

Cell lines, cultures and flow cytometry

To evaluate B and myeloid lineage development, 1000 double sorted stem and lymphoid progenitor cells were seeded, in triplicates, onto a monolayer of OP9-Control/OP9-W3A/OP9-W5A or OP9-Dkk1 in wells of a 24-well plate. This co-culture was maintained in OP9 medium [α-MEM medium (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), 10% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 5 ×10−5 M β-ME, 100 U/ml Penicillin and 100 mg/ml Streptomycin] in the presence of SCF (20 ng/ml), FL (5 ng/ml), and IL-7 (1 ng/ml) for the indicated time. At the end of culture, cells were counted excluding stromal cells and subjected to flow cytometry procedures for identification and analysis. For longer term cultures (21 days), 5,000–10,000 hematopoietic cells were harvested from each co-culture well and seeded on a fresh monolayer of stroma. Fluorescent labeled anti-CD45.2 (clone 104, eBioscience) antibody was used to positively distinguish hematopoietic cells from stromal cells.

For stroma free cultures to evaluate B and myeloid lineage development, 1000 double sorted stem or progenitor cells were seeded into wells of a 96 well dish. Cells were cultured in X-Vivo-15 medium containing 1% detoxified BSA, 20 ng/ml SCF, 100 ng/ml FL, 1 ng/ml IL7, 5 X 10−5 M β-ME, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin, for indicated periods of time.

For the two-step cultures outlined below, stem or progenitor cells were initially co-cultured on appropriate OP9 stroma for the indicated time, isolated by cell sorting and then cultured in the second medium.

To examine myelo-erythroid potential, cells of each sorted fraction were mixed with IMDM-based methylcellulose medium (100 cells/ml) supplemented with 50 ng/ml SCF, 10 ng/ml IL-3, 10 ng/ml IL-6, and 3 U/ml recombinant human erythropoietin (MethoCult GF 3434; StemCell Technologies). After 11 days, colonies were enumerated and classified according to shape and size under an inverted microscope.

For stroma free erythroid cultures, 2000 cells were seeded into wells of a 96 well dish. Cells were cultured in IMDM medium containing 0.5% detoxified BSA, BIT 9500, 20 ng/ml SCF, 50 ng/ml FL, 10 ng/ml IL-3, 50 ng/ml TPO, and 5 U/ml EPO for the indicated time.

In all cases, where flow cytometry was used, PI was used to exclude dead cells. Flow cytometry was performed on a BD FACS LSR-II (BD Biosciences), and data analysis was done with either BD FACSDiva (BD Biosciences) or FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Analysis of gene expression

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was used to assess mRNA expression of early lymphoid genes. mRNAs were isolated from sorted cells using MicroPoly (A) Purist (Ambion, Austin, TX) and converted to cDNA with murine Moloney leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RT-PCR was done in buffer containing 200 μM dATP, dGTP, dTTP, 100 μM dCTP, and 0.5 μCi [α-32P] dCTP. Aliquots were removed at cycle 25, 28, and 31 for β-actin and cycle 32, 35, and 38 for all others to ensure that PCR remained within the exponential range of amplifications. 5 μL aliquots were denatured in a formamide-loading buffer and applied to a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea. Incorporation of [α-32P] dCTP into PCR product bands was quantified by PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Primer sequences and amplification conditions are available from the authors on request.

Real time PCR to assess expression of Wnt family genes on stem and progenitor populations was done using pre-optimized SYBR-Green 96 well plate pathway specific RT2 Profiler™ primer-array (Catalog #APM-043C, Superarray, Frederick, MD). mRNAs were isolated from highly purified stem cells, ELPs, ProLs or CMPs and converted to cDNA, as described above. RT-PCR was done using reagents supplied with the primer-array and as described in the array user manual using ABI PRISM 7500 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A melting curve program was run immediately after the PCR for the entire 96 well plate, and only wells that showed a single peak (indicates specific amplification) following melting were included in analysis. All wells were also visually inspected for signs of evaporation. Data analysis for gene expression was calculated as 2−ΔΔCt (threshold cycles) values with β-actin as endogenous house keeping control. Results from this experiment are available from the authors on request.

Cytoplasm tracer dye (DDAO-SE) labeling

CellTrace Far Red DDAO-SE dye (Catalog #C34553, Invitrogen Life Technologies) was used as a cytoplasm labeling dye to analyze cell divisions by FACS. HSC were incubated with 10μM DDAO-SE (DMSO stock) in PBS (containing 0.1% detoxified BSA) for 10 min at 37°C in a water bath. Stain was then quenched by adding 5 volumes of ice cold culture media to the cells and incubated for 5 min on ice. Cell pellets were washed three times before seeding on appropriate cultures, as indicated. Intensity of the DDAO-SE signal which corresponded to the proliferation status of cultured cells was monitored at the times indicated by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of differences between groups was assessed with Students t-test, performed using GraphPad Prism software (Ver 5.01, GraphPad, San Diego, CA). A result was considered significant if the p-value was <0.05.

Results

Autocrine production of Wnt3a can completely block lympho-hematopoiesis

Over-expression of Wnt related molecules such as β-catenin has been used to probe consequences for hematopoiesis (15,19,20,42). However, there is little information about the potential for stem and progenitor cells to respond to their own regulators as suggested by the findings discussed above. We found no evidence that Wnt3a is constitutively made by stem or progenitor cells (data not shown and see materials and methods), but this molecule is made in bone marrow and has been extensively used to elicit canonical Wnt pathway signals (4,21,43,44). Therefore, we retrovirally introduced a Wnt3a expression cassette to the stem cell enriched LSK fraction of bone marrow before culturing the GFP+ cells under serum-free, stromal cell-free conditions (Figure 1). Flow cytometry analyses were conducted 11 days later, and this revealed dramatic suppression of differentiation as a result of Wnt3a. That is, numbers of total nucleated cells were greatly reduced relative to cells transduced with the control vector, and very few myeloid or lymphoid lineage cells were produced. In fact, the small number of recovered cells lacked CD45R/B220, CD19, CD11c, CD11b or NK1.1 lineage markers. Since stem and progenitors were the only cells present in these defined cultures, we can conclude that strong autocrine Wnt pathway signaling compromises hematopoiesis.

Figure 1.

Autocrine Wnt3a blocks hematopoiesis. Contour plots of flow cytometry results show potentials for (A) lymphopoiesis or (B) myelopoiesis from control (left) or Wnt3a transfected (right) LSK. Each population was held for 11 days in defined, stromal cell- free culture conditions, and (C) total cell yields per input progenitor, averaged with S.E. bars. One representative experiment of three is shown. Asterisks indicate statistical significance, * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01).

Stromal cell presentation of Wnt family molecules suggests that this family has regulatory potential

Matrix binding Wnt ligands normally act at short range, and potential target cells in bone marrow reside within a complex multicellular niche (9,45). Therefore, we stably over-expressed three Wnt family molecules in OP9 stromal cells before using them in co-culture experiments (Figure 2). This stromal cell clone was selected because of its inability to make CSF-1, while Wnt3a, Wnt5a and Dkk1 were used as canonical ligand, non-canonical ligand and antagonist, respectively. Flow cytometry performed after 11 days revealed that the differentiation of highly purified HSC to CD19+ B lineage lymphoid cells was completely blocked by exposure to stromal cell produced Wnt3a. CD45R/B220+ CD19− CD11c+ CD11b− NK1.1− plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) are similar in some ways to B cells, and their formation was also completely inhibited (Figure 2). While percentages of B220− CD19− CD11b+ CD11c+ conventional dendritic cells (cDC) and B220− CD19− CD11b+ CD11c− myeloid cells were not compromised by Wnt3a, their absolute numbers were significantly reduced in parallel with total nucleated cells (Figure 2c). Very similar results were obtained using stem cells from BCL-2 transgenic mice (data not shown). Differentiation patterns were quite different in Wnt5a-producing cultures, where numbers of CD19+ B lineage cells increased five fold. The effect was selective inasmuch as there were no remarkable changes in myeloid or dendritic cells. Control experiments established that DKK1-producing stromal cells were insensitive to canonical Wnt3a signals and could inhibit its effect (see Materials and Methods). Therefore, it was surprising that hematopoiesis was largely unaffected by co-culture on Dkk1 transduced stromal cells (Figure 2). In 4 independent experiments, lymphocyte yields were slightly higher in OP9-Dkk1 cultures than on control stromal cells, but this trend did not reach statistical significance. We conclude that Wnt3a and Wnt5a have opposing influences on B lymphopoiesis.

Wnt signaling preferentially regulates early events, and in opposing ways

We discovered that while B lymphopoiesis was totally blocked in Wnt3a-expressing short-term cultures (Figure 2), this was not the case at longer culture intervals (Figure 3). In fact, the most notable influence of Wnt3a at 21 days was an increase in numbers of CD11b+ myeloid cells. It seemed possible that some lymphoid progenitors escaped an early checkpoint and became progressively less Wnt responsive with differentiation. This was investigated by initiating cultures with stem cells and lymphoid progenitors (Figure 4). All produced at least some B lineage cells within 11 days, and yields were higher, as expected, when cultures were started with pre-pro-B cells. Dramatic results were obtained when the cells were exposed to Wnt3a. That is, pro-lymphocytes and pre-pro-B cells could still generate CD19+ B lineage cells even in the presence of Wnt3a, while lineage progression from earlier stages was totally blocked (Figure 4a and 4b). Many, but not all CD19− pro-lymphocytes acquired CD19 when exposed to Wnt3a producing stromal cells, and lymphocyte yields from CD19− pre-pro-B cells were only slightly affected by Wnt3a. We conclude that only stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors are completely sensitive to canonical Wnt pathway signaling.

Figure 3.

Wnt3a has minimal influence on B lymphopoiesis at long culture intervals. Contour plots (A) show hematopoietic development of HSC after 21 days of co-culture on the indicated Wnt family protein secreting cell lines. (B) Total cellular yields per input progenitor are given as averages with S.E. bars. Shown is one representative experiment of three. Asterisks indicate statistical significance, * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01), *** (p<0.0001).

Figure 4.

Wnt ligands preferentially affect early events. Contour plots (A) show B-lymphoid lineage development after 11 days of co-culture on the indicated Wnt family protein secreting cell line. (B) The same experimental results were calculated and shown as average yields per input progenitor with S.E. bars. Shown is one representative of 4 experiments. N.D. indicates not done. Asterisks indicate statistical significance, * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01), *** (p<0.0001).

While Wnt5a consistently augmented B lymphopoiesis in cultures initiated with HSC and evaluated after 11 days, lymphocyte numbers were equivalent to controls by 21 days (data not shown). Again, we asked if this might be ascribed to differential sensitivity of target cells. Enhanced B lineage lymphocyte differentiation was only seen in short-term cultures of HSC, and there was no noticeable influence on two types of lymphoid progenitors (Figure 4b). These findings indicate that, in this system, the influence of Wnt5a is also confined to the most primitive cells.

Progenitors that are not fully lymphoid committed lose differentiated properties in response to Wnt signaling

Artificial stimulation of the canonical Wnt pathway can restrict differentiation of primitive hematopoietic cells (5,15,20). We wondered if the same might be achieved on exposure to authentic Wnt. Many stem cells retained primitive staining characteristics after two days on Wnt3a producing stromal cells, and acquisition of lineage markers was partially inhibited even at 11 days (Figure 5a and b). Consistent with a previous study involving recombinant Wnt3a protein (4), we found that numbers of transplantable stem cells were retained on OP9-Wnt3a cells (data not shown). We consistently recovered fewer nucleated cells from such cultures, and DDAO-SE dye dilution analyses suggested that stem cell proliferation was inhibited in Wnt3a producing stromal cell co-cultures (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Wnt3a inhibits stem cell differentiation, slows their proliferation in co-cultures. (A) Contour plots show staining for freshly isolated lineage− c-KitHi Sca-1+ stem cells (left), or HSC after 2 days on OP9-Control (center) or after 2 days on OP9-Wnt3a stroma (right). (B) Overlay histogram shows acquisition of mature cell lineage markers by HSC after 11 days co-culture on OP9-Control (black solid line) or OP9-W3A (grey shaded overlay). (C) HSC were stained with the cytoplasmic DDAO-SE dye on day 0 (left panel) and evaluated after 3 days of co-culture on OP9-Control (center panel) or OP9-W3A (right panel). Dye dilution as a result of proliferation is illustrated in these flow cytometry histograms. Shown is one representative of four (A and B) or three experiments (C).

There is also evidence that Wnt signals can destabilize hematopoietic progenitors (18). That is, introduction of constitutively active β-catenin to lymphoid or myeloid progenitors allowed them to each be re-programmed to new fates. To investigate this phenomenon further, stem cells, ELP and pro-lymphocytes were sorted from RAG-1/GFP reporter mice and stimulated for 18 hrs in stromal cell co-cultures before RT-PCR analyses (Figure 6a). While fresh lymphoid progenitors contained RAG-1 transcripts and continued to contain substantial levels after culture on vector control transduced stromal cells, this was extinguished when ELP were placed on Wnt3a producing cells (Figure 6a). The same was true for progenitors representing the pro-lymphocyte stage. Remarkably, mRNAs corresponding to other transcription factors (Ebf, Pax-5 and Aiolos) were not substantially changed at this early time point (data not shown). RAG1/GFP levels normally increase when ELP are cultured, but this response was blocked in Wnt3a co-cultures (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

The canonical Wnt3a ligand extinguishes expression of RAG1 in lymphoid progenitors. (A) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses of RAG1 transcripts were performed on HSC, ELP or ProL. Transcripts represent gene expression of either freshly isolated bone marrow cells (marrow) or cells that were co-cultured overnight on OP9-Control (Control) or on OP9-W3A (W3A) cells. (B) Overlay histograms show RAG1/GFP protein levels of freshly isolated GFP− cells (blue) or ELP (red) compared to ELP that were cultured for two days on OP9-Control (black, solid) or OP9-W3A (grey shaded overlay) stromal cells. Shown is one representative of three experiments.

Progenitors progressively lose non-lymphoid potential as they differentiate towards the B lineage (46). For example, CLP transiently produce small numbers of myeloid cells following transplantation or co-culture while earlier cells can do so even in stromal cell-free progenitor assays (47–49). Numbers of non-lymphoid cells produced from lymphoid progenitors increased on exposure to Wnt3a producing stromal cells. This was recorded by flow cytometry where yields of CD19− B220− CD11c− CD11b+ cells dramatically increased (Figure 7a). This corresponded to small, but consistent increases in numbers of myeloid colony forming cells, and the colonies tended to be larger from progenitors that had been exposed to Wnt3a (Figure 7b and not shown).

Figure 7.

Wnt3a stimulates myeloid differentiation from lymphoid progenitors. (A) Total myeloid (CD19− B220− CD11b+ CD11c−) cell yields/input of HSC, ELP and ProL are shown for 11days of co-culture on OP9-Control or OP9-Wnt3a. (B) Myeloid colony forming efficiencies (CFU) are shown for HSC, ELP or ProL that were either freshly isolated or pre-stimulated on OP9-Control or OP9-Wnt3a for 3days and sorted before re-culture in methyl-cellulose medium. Shown is one representative experiment of three. Asterisks indicate statistical significance, * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01), *** (p<0.0001).

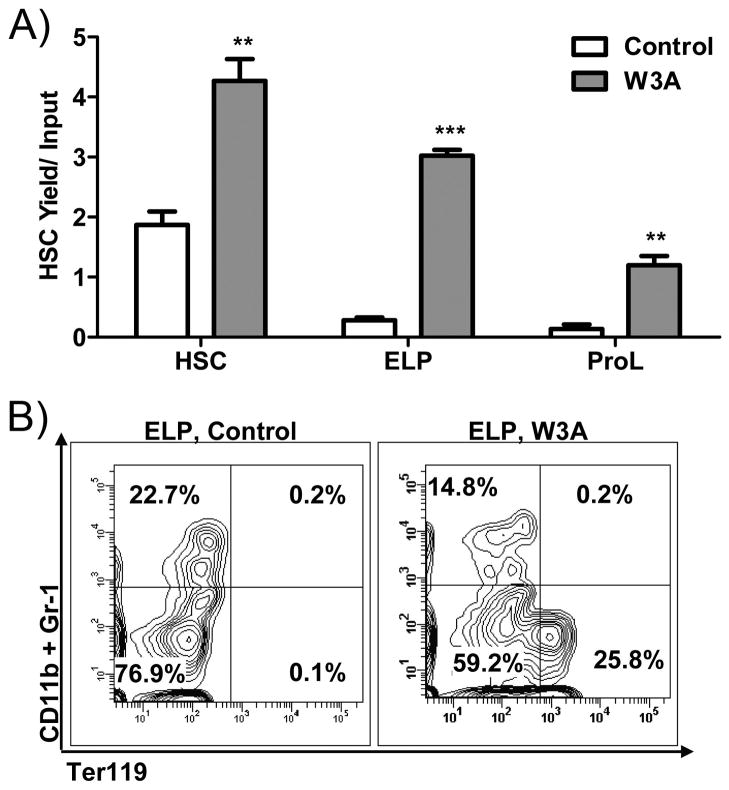

ELP and even some ProL re-acquired the RAG-1/GFP− Lin− Sca-1+ c-KitHi Thy1.1lo staining properties of stem cells (Figure 8a). Even more surprisingly, cells expressing the TER119 erythroid marker emerged when ELP were exposed to Wnt3a producing stromal cells for 3 days and then stimulated with erythropoietic factors (IL-3, TPO, SCF, FL and EPO; Figure 8b).

Figure 8.

Lymphoid committed progenitors acquire alternate lineage fates in response to Wnt3a. (A) HSC, ELP or ProL were placed in 11day co-cultures on OP9-Control or OP9-Wnt3a stromal cells. The recovered cells were then assessed for a stem cell (Lin− c-KitHi Sca-1+ Thy1.1lo) phenotype. Results are shown as total HSC yields/input. (B) ELP were pre-cultured on OP9-Control or OP9-Wnt3a stromal cells for 3days and sorted before re-culture under stromal cell-free erythroid supportive conditions. The contour plots show erythroid (Ter119+ CD11b− Gr-1−) differentiation potential in one representative of three experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance, ** (p<0.01), *** (p<0.0001).

These observations suggest that Wnt3a presented by stromal cells in vitro transiently and partially arrests lymphopoiesis. In contrast to results obtained with recombinant Wnt3a (4), we found that stem cell proliferation was inhibited. Additionally, lymphoid specified progenitors undergo a degree of de-differentiation.

Discussion

These new findings suggest ways that Wnt family proteins might differentially regulate B lymphopoiesis and provide a basis for reconciling previous reports. For example, the timing of ligand exposure and stage of differentiation were found to be important variables. From a large list of potentially important molecules, two ligands were shown to be capable of opposing actions and merit further study in that context. Although Wnt3a caused preservation and even re-acquisition of HSC properties, it did not appear to be a growth factor in short-term cultures.

Hematopoietic cells express a bewildering number of Wnt ligands, receptors, co-receptors, inhibitors and signaling intermediates. The only differentiation related trend in our screen for Wnt family gene expression in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells was a tendency for Fzd receptors to decline (data not shown and see materials and methods). As others have concluded from less comprehensive analyses (21,33,50), hematopoiesis could potentially be regulated by autocrine and paracrine Wnt dependent mechanisms. Wnt3a has been extensively used as a canonical Wnt pathway ligand (4,21,43,44), but it is noteworthy that we could not detect transcripts in highly enriched stem cells. A similar screen of stromal cells indicated that they may also produce and respond to multiple Wnt family molecules (data not shown).

Our gain-of-function experiments began by artificially expressing Wnt3a in hematopoietic cells and then culturing them under defined conditions. The aim was to test the possibility that stem and progenitors can be self-regulated by this mechanism. We recorded almost complete inhibition of myeloid and lymphoid differentiation while the residual cells lacked markers associated with these lineages. These results show that autocrine stimulation is possible and are consistent with many studies where differentiation was blocked by β-catenin (15,19,20). While some level of Wnt signaling might be beneficial to stem cells, it is clear that excessive stimulation would lead to marrow failure.

We then prepared cultures where selected Wnt molecules were produced by OP9 stromal cells that were unable to over-express CSF-1 and cause macrophage overgrowth (44). This system is more likely to reflect physiologic conditions than prior studies with retrovirally introduced or recombinant materials, and there was no concern about Wnt protein degradation. Our unpublished experience suggests Wnt is more effective when presented in this way, and the stromal cells provide differentiation factors needed to support dendritic cell formation. As when the ligand was produced by stem cells, stromal cell Wnt3a completely blocked the generation of B lineage lymphocytes. Consistent with their similarities to B cells (51), plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) also did not emerge. While CD11b+ CD11c− myeloid cells decreased, CD11b+ CD11c+ conventional dendritic cells (cDC) were produced relatively normally. This differential sensitivity is interesting inasmuch as it suggests Wnt can participate in lineage choice decisions. That would be consistent with the ability of Wnt to direct differentiation options in neuronal (52), bone (53) and cardiac tissues (54). Identical results were obtained with marrow from BCL-2 transgenic rather than normal mice. This was done to approximate conditions utilized in another Wnt investigation (4) and suggests Wnt3a does not inhibit by inducing apoptosis.

Numbers of pro-B and pre-B cells were expanded in fetal Wnt5a deficient mice, and it was proposed to function as a B lineage tumor suppressor (25). Therefore, it was surprising that production of B lineage lymphocytes was elevated five fold on Wnt5a-producing stromal cells. This effect was only observed when cultures were initiated with HSC; lymphoid progenitors displayed no sensitivity in our model, and there was no influence of Wnt5a on myeloid or dendritic cells. Consistent with our findings, Wnt5a has been reported to act as a growth factor for primitive hematopoietic cells (1,55) and is even up-regulated in various types of cancers and melanoma. A number of studies suggest Wnt5a utilizes non-canonical and Ca++ signaling pathways (25,56). Furthermore, it can oppose and even reverse canonical Wnt signaling in hematopoietic cells (26–28). Particularly interesting in this regard is the ability of Wnt5a to down-regulate β-catenin and thus inhibit T lymphopoiesis (26). Again, this suggests how Wnt family molecules can function as counter-acting regulators and participate in lineage fate decisions.

Dkk1 associates with LRP5, LRP6 and Kremen co-receptors, effectively acting as an inhibitor of canonical Wnt stimulation (57). There is additional evidence that it can block non-canonical signaling, and Dkk1 may itself function as a ligand (58,59). Although we are certain that Dkk1 made by our transduced OP9 stromal cells was biologically active (see Materials and Methods), there were no statistically significant consequences for lympho-hematopoiesis in co-cultures. We obtained similar results when HSC from fetal liver were cultured on OP9-Dkk1. To the extent that this model reproduces conditions in vivo, the findings do not prove that Wnt is needed for normal, steady state blood cell formation. However, the observations also do not preclude its possible importance during disease circumstances or when there are unusual demands for blood cells.

Results from Wnt studies may be easier to interpret if considered in terms of kinetics and maturation stage. While Wnt3a completely arrested B lymphopoiesis in 11 day cultures, similar populations of lymphocytes were present in Wnt3a and control cultures 10 days later. Moreover, total numbers of lymphocytes were suppressed only by approximately 30% at that time. This result is subject to several possible interpretations. For example, the level of Wnt3a might decay with time or be insufficient to prevent lineage progression. The Wnt3a/GFP expression cassette stably produced GFP over many passages and transduced stromal cells never lost their ability to suppress B lymphopoiesis in fresh cultures. In fact, our experimental design involved harvest and re-plating of hematopoietic cells onto new OP9-Wnt3a cells after the first 11 days. Alternatively, progenitors might become tolerant after repeated exposure to Wnt3a. Insufficient numbers of stem cells would be present after short term culture to directly address this possibility. It also seemed possible that a few escaping progenitors might differentiate, giving rise to cells that are less Wnt3a responsive. This would be consistent with the observation noted above that Fzd receptor levels are lower on progenitors than stem cells. Indeed, we found that progression in the B lymphocyte lineage correlated with decreasing responsiveness to Wnt3a or Wnt5a.

Consistent with this idea, stromal cell derived Wnt3a caused short-term retention of undifferentiated, stem-cell like populations in our cultures. Cells that had multi-lineage potential in transplantation assays were recovered after five days, while no activity was found in vector control transduced OP9 stromal cell co-cultures (data not shown). This is in agreement with reports that recombinant Wnt3a protein allowed propagation of stem cells (4). Furthermore, artificial stimulation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway allowed propagation of multipotential hematopoietic cells for many months (15). However, we believe it is unlikely that Wnt is a hematopoietic growth factor. As discussed above, our cultures were almost entirely composed of lymphocytes at longer intervals, and no attempt was made to investigate stem cell potential. We found no evidence that Wnt3a supports stem cell proliferation, and in fact, there was less than normal expansion in three day cultures. The same tendency was reported in previous studies (21,28,44). Although not cited as an important variable, two previous studies were done with BCL-2 transgenic rather than normal bone marrow (4,5) and used different culture conditions. It remains unclear if and how Wnt signaling can be exploited to expand stem cells therapeutically.

One approach to regenerative medicine involves de-differentiating and re-programming specialized cell types. In that context, it is interesting that expression of stable β-catenin caused lymphoid and myeloid progenitors to become lineage unstable (18). We now show that the same is true in co-cultures with Wnt3a producing stromal cells. That is, RAG-1 producing lymphoid progenitors became RAG-1− within 18 hours under these conditions. It will be important to find rapid changes in transcription factor levels that would account for RAG-1 down-regulation. Common lymphoid progenitors within the pro-lymphocyte fraction of bone marrow have very little myeloid differentiation potential (47–49). Thus, it is significant that increased numbers of myeloid cells were recovered from OP9-Wnt3a stromal cell co-cultures. ELP are much more lymphoid biased than stem cells or multipotent progenitors (46), and their myeloid potential also increased. Normally incapable of clonal proliferation in response to recombinant growth factors, some pro-lymphocytes re-acquired this potential in response to Wnt3a signaling. Two additional findings suggest that Wnt3a can reverse hematopoietic differentiation. Cells with a Lin− Sca-1+ c-KitHi Thy1.1Lo RAG-1− phenotype expanded in OP9-Wnt3a co-cultures. This was true even when cultures were initiated with RAG-1+ pro-lymphocytes sorted to high purity, diminishing the possibility that a primitive subset of cells preferentially expanded. Even more impressive was acquisition of the potential for erythroid lineage differentiation. This is thought to represent the earliest of lineage choice events in stem cell differentiation (60). In contrast to these results with Wnt3a, Wnt5a producing cultures always generated pure lymphocytes (Figure 4 and data not shown).

It remains unclear if Wnt signaling is essential for blood cell formation in normal bone marrow. That issue is difficult in part because what is observed represents the net influence of multiple Wnt pathways. However, our new findings show how members of this complex family have the potential to enhance or repress progression in the B lymphocyte lineage. Moreover, they might someday be exploited to confer primitive properties on differentiated cells.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported in part by grants AI 058162 and AI043544 from the National Institutes of Health as well as private institutional funds.

We acknowledge Dr. Stephen Jones (Univ. Mass. Medical School) for providing the Wnt5a vector and Dr. Irving Weissman (Stanford University) for Bcl-2 transgenic mice.

Reference List

- 1.Austin TW, Solar GP, Ziegler FC, Liem L, Matthews W. A role for the Wnt gene family in hematopoiesis: expansion of multilineage progenitor cells. Blood. 1997;89:3624–3635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Den Berg DJ, Sharma AK, Bruno E, Hoffman R. Role of members of the Wnt gene family in human hematopoiesis. Blood. 1998;92:3189–3202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato N, Meijer L, Skaltsounis L, Greengard P, Brivanlou AH. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat Med. 2004;10:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, Duncan AW, Weissman IL, Reya T, Yates JR, III, Nusse R. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 2003;423:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reya T, Duncan AW, Ailles L, Domen J, Scherer DC, Willert K, Hintz L, Nusse R, Weissman IL. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:409–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams GB, Scadden DT. The hematopoietic stem cell in its place. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:333–337. doi: 10.1038/ni1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Igarashi H, Gregory SC, Yokota T, Sakaguchi N, Kincade PW. Transcription from the RAG1 locus marks the earliest lymphocyte progenitors in bone marrow. Immunity. 2002;17:117–130. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy RR, Kincade PW, Dorshkind K. The protean nature of cells in the B lymphocyte lineage. Immunity. 2007;26:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coudreuse D, Korswagen HC. The making of Wnt: new insights into Wnt maturation, sorting and secretion. Development. 2007;134:3–12. doi: 10.1242/dev.02699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nusse R. 2008 http://www.stanford.edu/~rnusse/wntwindow.html.

- 11.Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staal FJ, Clevers HC. WNT signalling and haematopoiesis: a WNT-WNT situation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:21–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katoh M, Katoh M. WNT signaling pathway and stem cell signaling network. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4042–4045. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trowbridge JJ, Xenocostas A, Moon RT, Bhatia M. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is an in vivo regulator of hematopoietic stem cell repopulation. Nat Med. 2006;12:89–98. doi: 10.1038/nm1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baba Y, Yokota T, Spits H, Garrett KP, Hayashi S, Kincade PW. Constitutively active beta-catenin promotes expansion of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors in culture. J Immunol. 2006;177:2294–2303. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nostro MC, Cheng X, Keller GM, Gadue P. Wnt, Activin, and BMP Signaling Regulate Distinct Stages in the Developmental Pathway from Embryonic Stem Cells to Blood. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao C, Blum J, Chen A, Kwon HY, Jung SH, Cook JM, Lagoo A, Reya T. Loss of beta-catenin impairs the renewal of normal and CML stem cells in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:528–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baba Y, Garrett KP, Kincade PW. Constitutively active beta-catenin confers multilineage differentiation potential on lymphoid and myeloid progenitors. Immunity. 2005;23:599–609. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheller M, Huelsken J, Rosenbauer F, Taketo MM, Birchmeier W, Tenen DG, Leutz A. Hematopoietic stem cell and multilineage defects generated by constitutive beta-catenin activation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1037–1047. doi: 10.1038/ni1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirstetter P, Anderson K, Porse BT, Jacobsen SE, Nerlov C. Activation of the canonical Wnt pathway leads to loss of hematopoietic stem cell repopulation and multilineage differentiation block. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1048–1056. doi: 10.1038/ni1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dosen G, Tenstad E, Nygren MK, Stubberud H, Funderud S, Rian E. Wnt expression and canonical Wnt signaling in human bone marrow B lymphopoiesis. BMC Immunol. 2006;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cobas M, Wilson A, Ernst B, Mancini SJ, Macdonald HR, Kemler R, Radtke F. Beta-catenin is dispensable for hematopoiesis and lymphopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:221–229. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch U, Wilson A, Cobas M, Kemler R, Macdonald HR, Radtke F. Simultaneous loss of beta- and gamma-catenin does not perturb hematopoiesis or lymphopoiesis. Blood. 2008;111:160–164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeannet G, Scheller M, Scarpellino L, Duboux S, Gardiol N, Back J, Kuttler F, Malanchi I, Birchmeier W, Leutz A, Huelsken J, Held W. Long-term, multilineage hematopoiesis occurs in the combined absence of beta-catenin and gamma-catenin. Blood. 2008;111:142–149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang H, Chen Q, Coles AH, Anderson SJ, Pihan G, Bradley A, Gerstein R, Jurecic R, Jones SN. Wnt5a inhibits B cell proliferation and functions as a tumor suppressor in hematopoietic tissue. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:349–360. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang H, Coles AH, Zhu Z, Zayas J, Jurecic R, Kang J, Jones SN. Noncanonical Wnt signaling promotes apoptosis in thymocyte development. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3077–3084. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Topol L, Jiang X, Choi H, Garrett-Beal L, Carolan PJ, Yang Y. Wnt-5a inhibits the canonical Wnt pathway by promoting GSK-3-independent beta-catenin degradation. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:899–908. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nemeth MJ, Topol L, Anderson SM, Yang Y, Bodine DM. Wnt5a inhibits canonical Wnt signaling in hematopoietic stem cells and enhances repopulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15436–15441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ranheim EA, Kwan HC, Reya T, Wang YK, Weissman IL, Francke U. Frizzled 9 knock-out mice have abnormal B-cell development. Blood. 2005;105:2487–2494. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schilham MW, Wilson A, Moerer P, aissa-Trouw BJ, Cumano A, Clevers HC. Critical involvement of Tcf-1 in expansion of thymocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161:3984–3991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulroy T, Xu Y, Sen JM. beta-Catenin expression enhances generation of mature thymocytes. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1485–1494. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staal FJ, Meeldijk J, Moerer P, Jay P, van de Weerdt BC, Vainio S, Nolan GP, Clevers H. Wnt signaling is required for thymocyte development and activates Tcf-1 mediated transcription. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:285–293. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200101)31:1<285::AID-IMMU285>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weerkamp F, Baert MR, Naber BA, Koster EE, de Haas EF, Atkuri KR, van Dongen JJ, Herzenberg LA, Staal FJ. Wnt signaling in the thymus is regulated by differential expression of intracellular signaling molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3322–3326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511299103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mulroy T, McMahon JA, Burakoff SJ, McMahon AP, Sen J. Wnt-1 and Wnt-4 regulate thymic cellularity. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:967–971. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200204)32:4<967::AID-IMMU967>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nusse R. WNT targets. Repression and activation. Trends Genet. 1999;15:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molenaar M, Van de WM, Oosterwegel M, Peterson-Maduro J, Godsave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destree O, Clevers H. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell. 1996;86:391–399. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ioannidis V, Beermann F, Clevers H, Held W. The beta-catenin--TCF-1 pathway ensures CD4(+)CD8(+) thymocyte survival. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:691–697. doi: 10.1038/90623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuwata N, Igarashi H, Ohmura T, Aizawa S, Sakaguchi N. Cutting edge: absence of expression of RAG1 in peritoneal B-1 cells detected by knocking into RAG1 locus with green fluorescent protein gene. J Immunol. 1999;163:6355–6359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Igarashi H, Kuwata N, Kiyota K, Sumita K, Suda T, Ono S, Bauer SR, Sakaguchi N. Localization of recombination activating gene 1/green fluorescent protein (RAG1/GFP) expression in secondary lymphoid organs after immunization with T-dependent antigens in rag1/gfp knockin mice. Blood. 2001;97:2680–2687. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Domen J, I, Weissman L. Hematopoietic stem cells need two signals to prevent apoptosis; BCL-2 can provide one of these, Kitl/c-Kit signaling the other. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1707–1718. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morita S, Kojima T, Kitamura T. Plat-E: an efficient and stable system for transient packaging of retroviruses. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1063–1066. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Staal FJ, Weerkamp F, Baert MR, van den Burg CMNM, van de Haas EF, van Dongen JJ. Wnt target genes identified by DNA microarrays in immature CD34+ thymocytes regulate proliferation and cell adhesion. J Immunol. 2004;172:1099–1108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reya T, O’Riordan M, Okamura R, Devaney E, Willert K, Nusse R, Grosschedl R. Wnt signaling regulates B lymphocyte proliferation through a LEF-1 dependent mechanism. Immunity. 2000;13:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamane T, Kunisada T, Tsukamoto H, Yamazaki H, Niwa H, Takada S, Hayashi SI. Wnt signaling regulates hemopoiesis through stromal cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:765–772. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rattis FM, Voermans C, Reya T. Wnt signaling in the stem cell niche. Curr Opin Hematol. 2004;11:88–94. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000133649.61121.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Welner RS, Pelayo R, Kincade PW. Evolving views on the genealogy of B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:95–106. doi: 10.1038/nri2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaniel C, Bruno L, Melchers F, Rolink AG. Multiple hematopoietic cell lineages develop in vivo from transplanted Pax5-deficient pre-B I-cell clones. Blood. 2002;99:472–478. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rumfelt LL, Zhou Y, Rowley BM, Shinton SA, Hardy RR. Lineage specification and plasticity in. J Exp Med. 2006;203:675–687. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perry SS, Welner RS, Kouro T, Kincade PW, Sun XH. Primitive lymphoid progenitors in bone marrow with T lineage reconstituting potential. J Immunol. 2006;177:2880–2887. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin MA, Bhatia M. Analysis of the human fetal liver hematopoietic microenvironment. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:493–504. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pelayo R, Hirose J, Huang J, Garrett KP, Delogu A, Busslinger M, Kincade PW. Derivation of 2 categories of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in murine bone marrow. Blood. 2005;105:4407–4415. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pozniak CD, Pleasure SJ. A tale of two signals: Wnt and Hedgehog in dentate neurogenesis. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:e5. doi: 10.1126/stke.3192006pe5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glass DA, Bialek P, Ahn JD, Starbuck M, Patel MS, Clevers H, Taketo MM, Long F, McMahon AP, Lang RA, Karsenty G. Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev Cell. 2005;8:751–764. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen ED, Tian Y, Morrisey EE. Wnt signaling: an essential regulator of cardiovascular differentiation, morphogenesis and progenitor self-renewal. Development. 2008;135:789–798. doi: 10.1242/dev.016865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murdoch B, Chadwick K, Martin M, Shojaei F, Shah KV, Gallacher L, Moon RT, Bhatia M. Wnt-5A augments repopulating capacity and primitive hematopoietic development of human blood stem cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3422–3427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0130233100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Semenov MV, Habas R, Macdonald BT, He X. SnapShot: Noncanonical Wnt Signaling Pathways. Cell. 2007;131:1378. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niehrs C. Function and biological roles of the Dickkopf family of Wnt modulators. Oncogene. 2006;25:7469–7481. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pukrop T, Klemm F, Hagemann T, Gradl D, Schulz M, Siemes S, Trumper L, Binder C. Wnt 5a signaling is critical for macrophage-induced invasion of breast cancer cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5454–5459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509703103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee AY, He B, You L, Xu Z, Mazieres J, Reguart N, Mikami I, Batra S, Jablons DM. Dickkopf-1 antagonizes Wnt signaling independent of beta-catenin in human mesothelioma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:1246–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adolfsson J, Mansson R, Buza-Vidas N, Hultquist A, Liuba K, Jensen CT, Bryder D, Yang L, Borge OJ, Thoren LA, Anderson K, Sitnicka E, Sasaki Y, Sigvardsson M, Jacobsen SE. Identification of Flt3+ lympho-myeloid stem cells lacking erythro-megakaryocytic potential a revised road map for adult blood lineage commitment. Cell. 2005;121:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]