Abstract

A sample of 199 persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) were assessed on Big Five personality dimensions using the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO–FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992) at admission to an inpatient medical rehabilitation program. A cluster analysis of the baseline NEO–FFI yielded 3 cluster prototypes that resemble resilient, undercontrolled, and overcontrolled prototypes identified in many previous studies of children and adult community samples. Compared with normative samples, this sample had significantly fewer resilient prototypes and significantly more overcontrolled and undercontrolled prototypes. Undercontrolled individuals were the modal prototype. The resilient and undercontrolled types were better adjusted than the overcontrolled types, showing lower levels of depression at admission and higher acceptance of disability at discharge. The resilient type at admission predicted the most effective reports of social problem-solving abilities at discharge and the overcontrolled type the least. We discuss the implications of these results for assessment and interventions in rehabilitation settings.

There are approximately 253,000 persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) in the United States, with around 11,000 new cases each year. The high social and personal costs of SCI are well documented (National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, 2006). Spinal cord injury can touch almost every area of an individual's life, from work, to relationships, to physical and mental health (Dijkers, 2005). Much research has rightly been devoted to assessing the impact of SCI and to the study of factors that may predict subsequent emotional and physical adjustment. Progress has been made in identifying social (Elliott, Bush, & Chen, 2006; Holicky & Charlifue, 1999), functional disability (Waters, Adkins, Yakura, & Sie, 1998), and coping and problem-solving variables (Chan, Lee, & Lieh-Mak, 2000; Elliott, 1999) that are associated with a variety of adjustment outcomes.

In contrast with the large literature on coping and adjustment in SCI, few studies have examined basic personality processes among persons with SCI. Psychologists have been encouraged to include basic personality instruments in their clinical assessments (Elliott & Umlauf, 1995). There is good reason to heed this advice: An accumulation of research spanning three decades shows that a few basic personality dimensions, such as the Big Five personality factors (John & Srivastava, 1999), can be reliable predictors of functioning in important domains of life such as vocational achievement (Goodstein & Lanyon, 1999), quality of interpersonal relationships (Botwin, Buss, & Shackelford, 1997), psychological adjustment and coping (Elliott, Herrick, MacNair, & Harkins, 1994; McCrae, 1991; McCrae & Costa, 1986), overall happiness and satisfaction with life (Costa & McCrae, 1980; Myers & Diener, 1995), and general physical health and wellness behaviors (Booth-Kewley & Vickers, 1994). These are life domains that have been the focus of much research on physical disability and its consequences, but studies that have included personality assessments remain scarce.

In the literature on personality and SCI, there have been two lines of research. First are studies that have compared persons with SCI to normative control samples or to persons with other disabling conditions. These studies have often addressed the recurring question, “Is there a spinal cord injury personality?” (Trieschmann, 1980). Early anecdotal evidence and research using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Hathaway & McKinley, 1943) depicted persons with SCI (or at least subgroups who were deemed as “at fault” in some sense for their injury) as active, stimulation seeking, impulsive, and aggressive (Bourestom & Howard, 1965; Fordyce, 1964; Kendall, Edinger, & Eberly, 1978; Taylor, 1970). Both MMPI profiles and vocational interest data have indicated that individuals with SCI tend toward active, traditionally masculine roles (Kunce & Worley, 1966; Rohe & Athelstan, 1982). More recent studies using nonpathological personality trait measures have found that persons with spinal cord injury are elevated in extraversion or in traits commonly associated with extraversion such as sensation seeking, risk taking, and high activity levels (Heinrich, 1996; Malec, 1985; Mawson et al., 1996; Rohe & Krause, 1999). Rohe and Krause (1999) also reported that persons with SCI were significantly lower in conscientiousness than normative samples. Both high extraversion and low conscientiousness are consistent with the earlier characterizations of personality among many persons with SCI. The question of whether such distinctive personality features reflect preinjury risk factors or postinjury change remains unanswered (Hollick et al., 2001).

A second line of research has used basic nonpathological personality measures to predict adjustment following SCI. The most consistent predictors of adjustment have been low neuroticism (de Carvalho, Andrade, Tavares, & de Freitas, 1998; Heinrich, 1996; Krause & Rohe, 1998; Nagumo, 2000) and high extraversion (de Carvalho et al., 1998; Krause & Rohe, 1998; Nagumo, 2000). Several individual traits associated with extraversion (e.g., sociability, positive affectivity) and neuroticism (e.g., stress, anxiety, negative affectivity) also predict adjustment to SCI (Krause, 1997; Thompson, Coker, Krause, & Henry, 2003). Although neuroticism is negatively associated with adjustment, persons with SCI as a group do not appear to be elevated on this trait. Conscientiousness has been linked to employment and productivity following SCI (Krause, 1997; Krause & Rohe, 1998) but not to broader social and emotional adjustment.

The research conducted thus far has relied on a dimensional framework for assessing personality traits in SCI. Although there are advantages to dimensional trait assessments, the interpretation of quantitative, multidimensional representations can be daunting in clinical settings. Clinicians often prefer categorical or prototype classifications for clinical decision making (Cantor, Smith, French, & Mezzich, 1980; Millon, 1994; Widiger & Frances, 1994). In studies that have compared the predictive validity of dimensional versus typological classifications of personality, dimensional assessments typically yield significantly better predictions of outcomes (Costa, Herbst, McCrae, Samuels, & Ozer, 2002). Despite this, many practitioners urge that the conceptual economy of prototypes, in which a configuration of many traits is summarized by a single type classification, is sometimes worth the loss of predictive accuracy. Although finding that the dimensional measurement of Big Five traits was a better predictor of psychological functioning than personality clusters based on the Big Five, Costa et al. (2002) nonetheless argued for the possible conceptual and clinical utility of configural summaries of trait dimensions. In the next section, we describe a theoretical model of personality prototypes that might provide a clinically useful perspective on personality assessment with persons who have acquired physical disabilities.

Resilient, Overcontrolled, and Undercontrolled Personality Prototypes

A recent trend in personality research is a focus on categorical personality prototypes that might be assessed using traditional trait measures. Across many studies of adults and children, and utilizing a variety statistical techniques (e.g., Q-factor analyses, cluster analyses) and assessment methods (e.g., self-report and proxy measures), three reliable and theoretically interpretable personality prototypes have been reported (for reviews, see Caspi, 1998; Robins, John, & Caspi, 1998). The three personality prototypes have been described as resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled types. In studies using the Big Five personality factors, resilient individuals are characterized by low neuroticism and above-average scores on all other factors. Undercontrolled individuals are characterized by low conscientiousness (sometimes accompanied by elevated neuroticism and low agreeableness). Overcontrolled individuals are characterized by high neuroticism, low extraversion, and typically average scores on the remaining factors (Asendorpf, Borkenau, Ostentdorf, & van Aken, 2001; Robins, John, Caspi, Moffitt, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1996; Schnabel, Asendorpf, & Ostendorf, 2002).

These prototypes are most often interpreted according to Block and Block's (1980) theory of ego control and ego resiliency, two psychological functions related to the capacity for effective adaptation to change and conflict (Block, 1993). Ego control refers to a person's capacity for inhibition versus expression of emotional and motivational impulses. Ego resiliency refers to the capacity for flexible and appropriate self-regulation in response to uncertainty, change, and environmental demands. Ego resiliency can be understood as the effective regulation of ego control. Without effective ego resiliency, people will be characterized as tending toward either overcontrol or undercontrol. Resilient persons have been found to be relatively well adjusted, whereas undercontrolled persons tend toward a variety of externalizing problems and overcontrolled persons toward internalizing problems (Caspi & Silva, 1995; Robins et al., 1996). Relevant research has demonstrated that other indicators of ego resiliency (e.g., goal stability) can be predictive in theoretically consistent directions of distress and well-being among persons with recent-onset and long-term SCI (Elliott, Uswatte, Lewis, & Palmatier, 2000). The characterization of resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled personality prototypes in terms of adaptation to change and environmental demands could be a useful conceptual framework for psychologists working with persons who have acquired a severely disabling condition.

This Study

To our knowledge, no studies have been conducted to explore whether the Big Five personality factors might yield resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled personality prototypes among persons with severe physical disability. In this study, we examined whether these personality prototypes identified in several published studies of nonclinical samples would be replicated in a sample of individuals with SCIs. We next compared the distribution of personality prototypes obtained in the SCI sample with normative data on prototypes in adult community samples. In a study of the Big Five personality traits among 402 Division I–A college basketball players (McSherry, Davison, Kosoff, O'Connor, & Berry, 2005), a three-cluster solution obtained clear resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled prototypes. However, in comparison with community samples, the basketball players had significantly fewer undercontrolled and more overcontrolled prototypes. McSherry et al. hypothesized that competitive, team-oriented groups might create selection pressures against less conscientious and self-controlled members. The study illustrates the potential informativeness of comparing personality profile distributions across selected populations. Finally, in this study, we compared personality prototypes obtained in the SCI sample on demographic, injury, adjustment, and coping variables.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 199 patients with SCI (67 women, 132 men), with a mean age of 40.5 years (SD = 16.7). These individuals were admitted consecutively for inpatient medical rehabilitation and were referred for psychological assessment as part of their rehabilitation program. Admission to the unit was predicated on the medical stability of the individual, funding resources available to reimburse the facility for providing rehabilitation, and willingness of the individual to be admitted and participate in a rigorous rehabilitation program. Of those referred for assessment, there were 123 Euro-Americans (61.8%), 75 African Americans (37.7%), and 1 Asian American (0.5%) in the sample. The average level of education was 12.1 years (SD = 2.75). Of these individuals, 126 (63.3%) had incomplete lesions to the spinal cord, 67 (33.7%) had complete lesions, and 6 (3%) were unknown. At the time of assessment, the average time since injury was 73 weeks, but the distribution was highly positively skewed, ranging from 1 to 2,600 weeks (i.e., 50 years; SD = 293.5). The median was 4 weeks, and 88.7% of participants were assessed within a year of injury.

The initial psychological assessment at admission included measures of personality (NEO–FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992) and depressive behavior (The Inventory to Diagnose Depression [IDD]; Zimmerman & Coryell, 1987). Prior to leaving the rehabilitation program, patients were administered a discharge psychological evaluation. This evaluation was designed to assess psychological adjustment, career-related concerns and needs, and cognitive-behavioral characteristics at discharge that would be important in recommending and developing outpatient follow-up programs. Time to discharge varied depending on patient progress, discharge plans, and reimbursement, but most patients were discharged within 3 months. The discharge assessment included the Social Problem Solving Inventory–Revised (SPSI–R; D'Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares, 2002) and The Acceptance of Disability Scale (AD; Linkowski, 1971). Due to vagaries and inconsistencies inherent in the procedures for discharge from the medical facility, a subset of participants completed the discharge assessment.

Instruments

NEO–FFI (Costa & McCrae, 1992)

The NEO-FFI is a shortened, 60-item version of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO–PI–R; Costa & McCrae, 1992) for assessing five domains of adult personality: Neuroticism (N), Extraversion (E), Openness to Experience (O), Agreeableness (A), and Conscientiousness (C). The NEO–FFI factors show correlations between .75 (C) and .89 (N) with the fullscale NEO–PI factors. Internal consistency reliabilities for the NEO–FFI have ranged from .68 (A) to .86 (N), and test–retest reliabilities have ranged from .79 (E and O) to .89 (N; Costa & McCrae, 1992). In this study, raw test scores were converted to gender-specific T scores based on the adult norms provided in Costa and McCrae (1992).

IDD (Zimmerman & Coryell, 1987)

The IDD is a 22-item measure of depressive behavior. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (no presence of the symptoms) to 4 (severe symptomatology;Zimmerman, Coryell, Corenthal & Wilson, 1986). The IDD is a sensitive indicator of depression among community-residing adults and persons with a variety of health problems (Frank et al., 1992). Good test–retest reliabilities (.98 over days) and internal consistency coefficients (.92) have been reported. Correlations with other self-report measures of depression have been adequate (ranging from .80 to .87; Zimmerman & Coryell, 1987; Zimmerman, Coryell, Corenthal, et al., 1986; Zimmerman, Coryell, Wilson, & Corenthal, 1986). The IDD has been recommended as a useful measure of depressive symptoms in the rehabilitation setting (Elliott & Umlauf, 1995).

SPSI–R (D'Zurilla et al., 2002)

The SPSI–R is a 52-item self-report inventory for assessing five facets of problem solving. Two scales measure the problem orientation dimensions of D'Zurilla et al.'s (2002) social problem-solving model: positive problem orientation (PPO) and negative problem orientation (NPO). The remaining three scales assess different problem solving styles, including rational problem solving (RPS), the impulsivity/carelessness style (IC), and the avoidance style (AV).

The PPO scale assesses a cognitive set that includes the tendency to view problems in a positive light, to see them as challenges rather than threats, and to be optimistic about one's ability to find and implement solutions. The NPO scale assesses a cognitive-emotional set indicative of pessimism, lack of motivation toward problem solving, and negative moods that hinder effective problem solving. The RPS scale assesses the tendency to systematically employ effective problem-solving techniques by defining problems, generating and evaluating alternatives, and implementing and evaluating outcomes. The IC scale assesses the tendency to solve problems in an impulsive, incomplete, and haphazard manner. The AV scale assesses the tendency to put problems off and wait for problems to solve themselves. In a sample of college students D'Zurilla et al. (2002) found internal consistency (alpha) estimates ranged from .76 (PPO) to .92 (RPS), and 3-week test–retest reliabilities ranged from .72 (PPO) to .88 (NO).

D'Zurilla et al. (2004) suggested that the PPO and RPS scales indicate a constructive problem-solving style, whereas NPO, AS, and ICS indicate a dysfunctional problem-solving style. Both confirmatory and exploratory factor analyses have supported this conceptualization (Elliott, Rivera, Berry, & Oswald, 2006; Johnson, Elliott, Neilands, Morin, & Chesney, 2006). In this study, a principal components analysis with varimax rotation yielded two orthogonal factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The first, accounting for 43.6% of the original variance, had high loadings on AS (.86), NPO (.85), and ICS (.69), which is consistent with a dysfunctional problem-solving dimension. The second factor, accounting for 32.9% of the original variance, had high loadings from PPO (.84) and RPS (.82), which is consistent with a constructive problem-solving dimension. In subsequent data analyses, we used the unit weighted sum of PPO and RPS to assess composite constructive problem-solving style and the sum of NPO, AS, and ICS scales to assess composite dysfunctional problem-solving styles.

AD (Linkowski, 1971)

The AD is a 50-item scale for evaluating an individual's positive adjustment to disability (finding meaning, valuing self-hood, maintaining a positive view of self). Higher scores indicate more positive adjustment. The AD scale has acceptable internal consistency estimates and is a sensitive index of adjustment to a variety of chronic and debilitating conditions (Linkowski, 1986). The AD scale is thought to be one of the better available indicators of positive adjustment among persons with acquired physical disabilities (Elliott, Kurylo, & Rivera, 2002).

Results

Descriptive Data

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the NEO–FFI T scores, the IDD, the AD, and the SPSI–R individual subscales, and the composite Constructive Problem-Solving Scale and Dysfunctional Problem-Solving Scale. Intercorrelations among all scales are also provided. Depression was most strongly associated with N among the concurrently assessed personality variables, and prospectively, it was most associated with a NPO and avoidant style (AS) of problem solving at discharge. Acceptance of disability at discharge was most strongly associated with baseline N scores and with NPO and AS at discharge.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Personality, Adjustment, and Social Problem-Solving Variables.

| Variable | N | E | O | A | C | IDD | AD | PPO | NPO | RPS | IC | AS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEO–FFIa | ||||||||||||

| 1. N | — | −.36*** | −.12 | −.31*** | −.39*** | .42*** | −.51*** | −.31** | .49*** | −.25** | .28** | 39*** |

| 2. E | — | .19** | .21** | .39*** | −.16* | .26** | .33** | −.11 | .36*** | −.06 | −.08 | |

| 3. O | — | .17* | .01 | −.01 | .24* | .16 | −.07 | .29** | −.11 | −.10 | ||

| 4. A | — | .16* | −.18* | .28** | .04 | −.17 | .14 | −.20* | −.18 | |||

| 5. C | — | −.03 | .23* | .41*** | −.26** | .44*** | −.17 | −.26** | ||||

| Adjustment | ||||||||||||

| 6. IDDa | — | −.30** | .06 | .37*** | .03 | .15 | .24* | |||||

| 7. ADb | — | .24* | −.52*** | .22* | −.37*** | −.46*** | ||||||

| SPSIb | ||||||||||||

| 8. PPO | — | −.11 | .61*** | .09 | −.20* | |||||||

| 9. NPO | — | .01 | .52*** | .70*** | ||||||||

| 10. RPS | — | −.10 | −.14 | |||||||||

| 11. IC | — | .44*** | ||||||||||

| 12. AS | — | |||||||||||

| M | 47.8 | 54.2 | 45.3 | 48.4 | 51.5 | 12.4 | 218.6 | 13.1 | 6.9 | 44.5 | 8.5 | 5.6 |

| SD | 10.6 | 11.5 | 9.6 | 11.5 | 9.9 | 9.48 | 45.53 | 3.88 | 7.38 | 14.36 | 7.03 | 5.10 |

Note. N = Neuroticism; E = Extraversion; O = Openness to Experience; A = Agreeableness; C = Conscientiousness; IDD = The Inventory to Diagnose Depression; AD = Acceptance of Disability Scale: SPSI = Social Problem Solving Inventory–Revised; PPO = positive problem orientation; NPO = negative problem orientation; RPS = rational problem solving; IC = impulsivity/carelessness style; AV = avoidance style; NEO–FFI = NEO Five Factor Inventory.

N = 199.

N = 105.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

There were no extreme mean levels on any of the five personality factors, and standard deviations were close to 10 across factors. Based on conventional standards of interpreting T scores as high or low in terms of 5-point deviations from the mean of 50, the SCI sample would not be characterized (as a group) as dramatically different from normative adult samples. The elevated extraversion scores are consistent with previous research, however, and lower openness might reflect the narrow range of masculine interests reported in several studies.

Cluster Analysis of Personality Scales

Derivation of cluster types

In deriving cluster solutions in our sample, we replicated the most widely used strategy followed in previous cluster analyses of the Big Five traits. We first used Ward's hierarchical clustering method for an initial solution followed by iterative k-means clustering with the solution from Ward's method as the initial cluster centers (Asendorpf et al., 2001; Costa et al., 2002; Rammstedt, Riemann, Angleitner, & Borkenau, 2004). Table 2 displays diagnostic statistics from the initial Ward clustering that are useful in determining the number of clusters to retain (only solutions from 10 clusters to 1 cluster are presented). The largest shifts in both the between-cluster sums of squares and in the semipartial R2occur in the transition from the 3-cluster to the 2-cluster solution. Also, the pseudo-F statistic has a local maximum at the 3-cluster solution, and the pseudo-t2 showed the largest increase between the 3-cluster and 2-cluster solutions. Based on these statistics, we accepted a 3-cluster solution as the best initial solution. We used the cluster centers from this 3-cluster solution to implement a nonhierarchical k-means clustering procedure to optimize our final cluster classifications (SPSS Version 9, [SPSS, Inc., Cary, NC]; procedure Quick Cluster, option NOUPDATE). Each case was assigned to a cluster based on Euclidean distances from cluster means. Cohen's kappa between cluster classifications from the Ward solution and the k-means solution was .77.

Table 2. Diagnostic Statistics for Determining the Number of Cluster Solutions to Retain.

| Cluster Number | BSS | SPRSQ | PF | PTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 2.3 | .02 | 32.1 | 14.7 |

| 9 | 2.9 | .03 | 32.8 | 12.9 |

| 8 | 3.6 | .03 | 34.0 | 12.7 |

| 7 | 3.7 | .03 | 35.8 | 14.4 |

| 6 | 3.9 | .03 | 38.1 | 11.7 |

| 5 | 4.2 | .03 | 42.0 | 15.9 |

| 4 | 6.9 | .04 | 47.6 | 16.1 |

| 3 | 7.1 | .07 | 52.9 | 25.6 |

| 2 | 11.8 | .14 | 52.0 | 43.0 |

| 1 | 23.1 | .21 | — | 52.0 |

Note. BSS = between-cluster sums of squares; SPRSQ = semipartial R2; PF = pseudo-F; PTS = pseudo-t2.

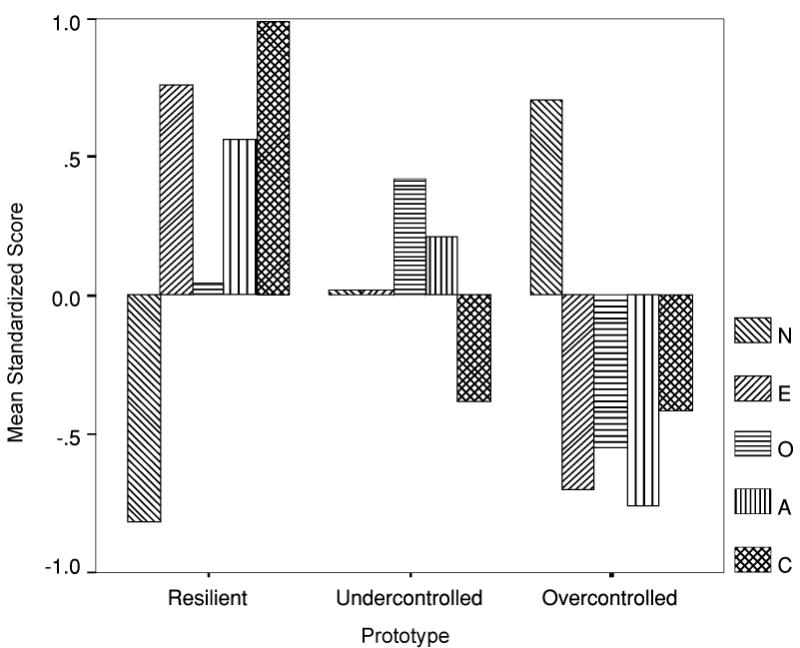

Figure 1 presents the personality prototypes (using z scores for ease of interpretation) of the three groups obtained from the cluster analysis. One group was characterized by low N and higher than average levels on all other Big Five factors. This profile is consistent with the resilient prototype obtained in previous studies. The second group (undercontrolled) was characterized by low C and average or above on the other factors. The third group (overcontrolled) was characterized by high N and low E, as in previous community samples. However, this profile was also characterized by low scores on all other factors including conscientiousness.

FIGURE 1.

Three personality prototypes based on the NEO Five Factory Inventory in the sample of 199 persons with spinal cord injury. Resilient prototype = 28.6% of sample; undercontrolled = 39.2%; overcontrolled = 32.2%. N = Neuroticism; E = Extraversion; O = Openness; A = Agreeableness; C = Conscientiousness.

Profile pattern comparisons across studies

Asendorpf et al. (2001) recommended the use of Cohen's kappa coefficients to compare the similarity of profiles across studies and samples. We compared profile patterns obtained in this SCI sample to profiles reported in two previous studies (both involving cluster analyses of self-report Big Five trait levels in adult samples). One comparison profile was based on within-sample z scores presented by Asendorpf et al. (2001) in which the German NEO–FFI was used in a cluster analysis of 730 adults. The other comparison profile was based on within-sample z scores presented by Schnabel et al. (2002) who used the full NEO–PI–R (German Version) in a cluster analysis of 786 adults. We used the mean within-sample z scores from these studies as initial cluster centers in a k-means cluster analysis of our within-sample z scores. New classifications of our SCI participants were then produced on the basis of Euclidean distances from cluster means. A kappa coefficient was calculated to assess the agreement of classification between this solution and our original solution. The kappa coefficient between our original classifications and those based on data from Asendorpf et al. (2001) was .67. The kappa coefficient between the SCI classifications and those based on data from Schnabel et al. (2002) was .83. Asendorpf et al. (2001) suggested that kappa values of .60 or greater indicate adequate profile agreement.

Based on the cluster analysis classifications, 28.6% of the participants had resilient personality profiles, 39.2% had undercontrolled profiles, and 32.2% had overcontrolled profiles. Across four studies of adults and children, Asendorpf et al. (2001) found the average proportions of each personality profile to be as follows: 49% resilient, 28% undercontrolled, and 23% overcontrolled. A chi-square goodness-of-fit test indicates that the distribution of personality profiles of the SCI sample differed from the distributions found in these samples, χ2(2, N = 199) = 32.9, p < .001, Cohen's w = .45. In the SCI sample, resilient personality types were underrepresented (observed N = 57, expected = 97.5), and both overcontrolled (observed N = 64, expected = 45.8) and undercontrolled (observed N = 78, expected = 55.7) prototypes were overrepresented.

Comparison of Profile Types in the SCI Sample

Demographics and injury variables

There were no significant age or education differences among the prototypes (see Table 3). There were no significant gender differences associated with the prototypes, χ2(2, N = 199) = 2.28, p = .32, ϕ; = .11. Among men, 31.1% were resilient, 35.6% undercontrolled, and 33.3% overcontrolled. Among women, the percentages, respectively, were 23.9%, 46.3%, and 29.9%. There were no significant differences between Euro-American and African American participants in profile type, although the test value approached significance, χ2(2, N = 199) = 5.36, p = .07, ϕ = .16. Among Euro-Americans, 32.5% were resilient, 41.5% undercontrolled, and 26% overcontrolled. Among African Americans, 22.7% were resilient, 36% undercontrolled, and 41.3% overcontrolled.

Table 3. Comparison of Personality Prototypes on Adjustment and Problem-Solving Variables.

| Resilient

|

Undercontrolled

|

Overcontrolled

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | d12 | M | SD | d23 | M | SD | d13 | η2 | F |

| Age | 41.8 | 15.4 | .07 | 40.7 | 17.2 | .10 | 38.9 | 17.3 | .18 | .01 | .45 |

| Years education | 12.4 | 3.31 | .00 | 12.4 | 2.58 | .36 | 11.5 | 2.33 | .32 | .02 | 2.20 |

| Depression | 10.5 | 9.34 | −.01 | 10.6 | 7.56 | −.59 | 16.0 | 10.70 | −.55 | .07 | 7.51** |

| AD | 236.2 | 34.84 | .27 | 227.7 | 26.79 | .78 | 193.1 | 56.41 | .92 | .17 | 10.07*** |

| PPO | 14.4 | 3.70 | .44 | 12.9 | 3.07 | .24 | 12.0 | 4.41 | .59 | .07 | 3.70* |

| NPO | 3.8 | 5.36 | −.68 | 8.4 | 7.88 | −.04 | 8.7 | 7.78 | −.73 | .09 | 5.10** |

| RPS | 49.5 | 14.74 | .24 | 46.2 | 12.52 | .63 | 38.1 | 13.54 | .81 | .12 | 6.65** |

| IC | 6.3 | 4.77 | −.51 | 9.5 | 7.59 | −.02 | 9.6 | 7.98 | −.50 | .05 | 2.51† |

| AS | 4.0 | 3.44 | −.42 | 5.8 | 5.07 | −.20 | 6.9 | 6.10 | −.58 | .06 | 3.10* |

| Constructive PS | 63.9 | 17.6 | .30 | 59.2 | 14.1 | .60 | 50.1 | 16.5 | .81 | .12 | 6.80** |

| Dysfunctional PS | 14.2 | 11.4 | −.64 | 23.6 | 17.2 | −.10 | 25.3 | 17.9 | −.74 | .09 | 5.10** |

Note. Degrees of freedom for age, education, and depression are (2, 193); all others (2, 104); d12 = Cohen's d between the resilient and undercontrolled groups; d23= Cohen's d between the undercontrolled and overcontrolled groups; d13= Cohen's d between the resilient and overcontrolled groups; η2= partial eta squared. AD = Acceptance of Disability Scale; PPO = positive problem orientation; NPO = negative problem orientation; RPS = rational problem solving; IC = impulsivity/carelessness style; AS = avoidant style; PS = problem solving.

Profile differences between participants with complete versus incomplete lesions approached statistical significance, χ2(2, N = 193) = 5.61, p = .06, ϕ = .17. Among those with incomplete lesions, 34.1% were resilient, 38.9% undercontrolled, and 27% overcontrolled. Among those with complete lesions, 20.9% were resilient, 37.3% undercontrolled, and 41.8% overcontrolled.

Adjustment and social problem solving

Table 3 provides descriptive statistics, omnibus significance tests, and effect sizes for the three personality prototype groups on depression, acceptance of disability, and social problem-solving variables. Analyses of variance were used to compare group differences.

In comparing the three personality prototypes on concurrently assessed depression (using Tukey's honestly significant difference for all pairwise comparisons), we found that the overcontrolled group was significantly higher than the resilient group (p < .01) and the undercontrolled group (p < .01); the latter groups did not differ significantly from each other (p = .98). Higher depression in the overcontrolled group is consistent with the description of overcontrolled individuals as prone to internalizing problems. For acceptance of disability at discharge from treatment, the overcontrolled group was significantly lower than both the resilient (p < .01) and undercontrolled groups (p < .01), whereas the latter did not differ significantly from each other (p = .62).

In social problem-solving orientation, being in the resilient group at admission predicted significantly higher PPO at discharge than being in the overcontrolled group (p < .05). PPO scores did not differ between the resilient and undercontrolled groups (p = .25) or the overcontrolled and undercontrolled groups (p = .53). The resilient group was significantly lower in NPO than both the undercontrolled (p < .05) and overcontrolled groups (p < .05); the latter groups did not differ significantly from each other (p = .98).

In specific problem-solving styles, the overcontrolled group was significantly lower in RPS at discharge than both the resilient (p < .01) and undercontrolled groups (p < .05); the latter did not differ significantly from each other (p = .53). The overcontrolled group was significantly lower than the resilient group in AS (p < .05) but did not differ from the undercontrolled group (p = .57). The resilient and undercontrolled groups did not differ significantly from each other (p = .32). There were no significant group differences on the IC subscale.

We also compared the personality profile groups on their overall constructive and dysfunctional problem-solving styles (see Table 3). For constructive problem solving, the overcontrolled group was significantly lower than both the resilient (p < .01) and undercontrolled groups (p < .05), whereas the latter did not differ significantly from each other (p = .44). For dysfunctional problem solving, the resilient group was significantly lower than both the undercontrolled (p < .05) and overcontrolled groups (p < .05), but the latter groups did not differ significantly from each other (p = .90).

Follow-up respondents versus nonrespondents

Because social problem solving and adjustment data were available only for a subset (N = 105) of patients who participated in the discharge assessment, we compared those participants with follow-up data to those without follow-up data on the Big Five traits, demographic, and injury variables. These analyses are presented in Table 4. Although the two groups did not differ significantly in gender and ethnic composition or on the Big Five traits, the patients who did not participate in the follow-up assessment were older, had longer time since injury, had a lower percentage of complete lesions, and had a considerably higher percentage of lesions due to disease processes rather than impact events such as motor vehicle accidents, violence, and other accidents. The patients for whom we obtained follow-up assessments are perhaps more representative of the national SCI population. The mean age of new SCI patients (since 2000) is 38 years, and the most common cause of SCI is motor vehicle accidents (46.9%), followed by falls and violence (National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, 2006). Nonetheless, because the nonresponse data do not appear to be missing at random, we must be cautious in generalizing the results of our personality profile comparisons around social problem solving and acceptance of disability.

Table 4. Comparison of Participants for Whom Follow-Up Data Were Available to Participants For Whom Follow-Up Data Were Not Obtained.

| Follow-Upa |

No Follow-Upb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | t | d |

| N | 47.6 | 11.4 | 47.7 | 9.8 | .06 | −.01 |

| E | 55.1 | 12.4 | 53.4 | 10.3 | −1.07 | .15 |

| O | 45.3 | 9.7 | 45.2 | 9.6 | −.08 | .01 |

| A | 48.6 | 12.1 | 47.8 | 10.9 | −.55 | .07 |

| C | 52.5 | 9.8 | 50.5 | 9.8 | −1.47 | .20 |

| Age | 37.1 | 15.5 | 44.3 | 17.3 | −7.31** | −.44 |

| Years education | 11.9 | 2.5 | 12.3 | 3.0 | −1.02 | −.15 |

| % | % | χ2 | Φ | |||

| Male | 70.5 | 61.7 | 1.71 | −.09 | ||

| White | 62.9 | 62.6 | 1.17 | .08 | ||

| Complete lesion | 43.3 | 24.7 | 7.28** | .19 | ||

| Years since injury > 1 | 5.7 | 20 | 9.16** | .21 | ||

| Cause of lesion | 21.9** | .33 | ||||

| MVA | 41.9 | 25.8 | ||||

| Violence | 13.3 | 9.7 | ||||

| Disease | 16.2 | 43.0 | ||||

| Fall | 15.2 | 12.9 | ||||

| Athletic injury | 9.5 | 2.2 | ||||

| Other | 3.8 | 6.5 | ||||

Note. MVA = motor vehicle accident.

n = 105.

n = 94.

Typological versus dimensional prediction

Although the three-type personality classifications in our data predicted significant variance in adjustment and problem-solving outcomes, we were interested in whether the dimensional assessment of Big Five traits could improve on prediction of these outcomes. For depression, acceptance of disability, and constructive and dysfunctional problem-solving styles, we conducted two-step hierarchical linear regressions predicting each criterion from (a) dummy-coded personality prototypes at Step 1 and (b) all of the dimensional Big Five traits at Step 2. The Step 1 model accounted for a significant proportion of variance in each criterion variable (see the partial eta-squared values in Table 3). At Step 2, the dimensional Big Five variables yielded a significant increase in prediction for all criteria: depression, ΔR2 = .14, p < .01; acceptance of disability, ΔR2 = .22, p < .001; constructive problem solving, ΔR2 = .18, p < .01; and dysfunctional problem solving, ΔR2 = .17, p < .001. These results are similar to findings of other studies comparing the quantitative predictive validity of typological versus dimensional assessments of Big Five variables (Costa et al., 2002).

Discussion

The cluster analysis of personality factors in a sample of individuals with SCI yielded three personality prototypes that can be interpreted as resilient, undercontrolled, and overcontrolled types. One prototype (resilient) was characterized by low N and above-average scores on all other factors. Another prototype (undercontrolled) was characterize by low C and average or slightly elevated scores on all other factors. The third prototype (overcontrolled) was characterized by high N and low E (the defining characteristics of overcontrolled prototypes in previous research) and also by low scores on the other factors. A prototype similar to our third prototype pattern, which had low levels of C and A in addition to the typical overcontrolled N and E pattern, was labeled “Overcontrolled/Non-desirable” by Barbaranelli (2002) who found such a profile in a sample of students and young adults.

Compared to community adult samples, our SCI sample had a significantly lower proportion of resilient prototypes (just under 30% compared with approximately 50% in community samples). Both undercontrolled and overcontrolled types were significantly overrepresented in the SCI sample, but the undercontrolled prototype was the most prevalent (almost 40%). Differences in the distribution of prototypes between our SCI sample and normative samples raises the question of whether such differences reflect postinjury changes in personality or preinjury risk factors for acquiring SCI. Our data provide no means of addressing this question.

Individuals with SCI who had resilient and undercontrolled personality types at admission were similar to each other in levels of adjustment (concurrent depression and subsequent acceptance of disability), both significantly better adjusted than the overcontrolled types. Both the resilient and undercontrolled types utilized more positive, rational problem solving at discharge compared to the overcontrolled group. The resilient group, however, appears better able than both the undercontrolled and overcontrolled groups to avoid negative, avoidant, and impulsive approaches to problem solving.

As in previous studies (Costa et al., 2002), the dimensional measurement of Big Five traits improved the predictive accuracy of outcomes beyond prototype classifications alone, but the persistence of the three-cluster solution across samples is intriguing and potentially of theoretical import. The results of our study support the possible value of the concepts of ego resilience and control in understanding adjustment to SCI, but the results do not imply that the configural scoring of the Big Five traits is the optimal approach to assessing these concepts. There is, in fact, no a priori reason to suppose that a typological rather than dimensional approach to these concepts is optimal.

With Costa et al. (2002), we believe that the configural scoring of the Big Five traits might still prove clinically useful in a variety of specialized contexts. In our estimation, the prototype patterns of personality variables identified in this study provide a convenient summary of trait information for assessing likelihood of adjustment to SCI. Simple correlational analyses suggest that low C scores are associated with less successful adjustment and with ineffective problem solving. However, our prototype comparisons indicate that low C predicts poor adjustment mainly when combined with a more internalizing and disagreeable personality profile. In the absence of these undesirable traits, individuals with low C scores are perhaps still able to utilize positive, hopeful, and rational problem-solving strategies in coping with their disabilities. Among these undercontrolled types, low C might reflect injury-related difficulties with self-regulation or perhaps realistic constraints on ambition.

To a great extent, these results converge with other work that has examined personality disorder characteristics among persons hospitalized with SCI. In one particularly relevant study, Cluster C characteristics—indicative of an anxious, fearful, dependent, and avoidant personality styles—were significantly associated with lower acceptance of disability scores (Temple & Elliott, 2000); Cluster A and B characteristics did not predict adjustment. Additionally, a high frequency of individuals with Cluster B profiles was observed. Despite the fairly high number of persons with acquired SCI who exhibit greater sensation seeking, impulsiveness, and restlessness than observed among other samples, it appears that these characteristics do not uniquely predispose an individual to distress and depression following SCI. In fact, there is evidence that persons who are more willing to be assertive in social situations are more likely to experience less distress and less psychosocial impairment following SCI than those who are not (Elliott et al., 1991). Apparently, individuals who are overcontrolled and prone to rumination, pessimism, avoidance, and internalization are more likely to report depressive symptoms and less likely to find meaning in their circumstances than those who are more active and flexible in their styles.

The results of this study could potentially have implications for targeted interventions in rehabilitation settings. The resilient personality prototypes are the most adjusted and the most effective in coping and problem solving. The overcontrolled/undesirable personalities, in contrast, are in greatest need of intervention. The majority, undercontrolled prototype, however, possibly represents the most cost-effective group for intervention. These individuals possess definite positive problem-solving capacities and better adjustment (in contrast with the more negativistic, pessimistic, and internalizing overcontrolled prototypes), but their low C scores (and somewhat elevated negative problem-solving abilities) suggest that problems with self-regulation might eventually disrupt adherence to self-care programs that could then culminate in preventable secondary complications (e.g., decubitus ulcers). The failure to engage in protective health behavior may be associated with sensation seeking, low C, hostility, and impulsivity (Friedman, Hawley, & Tucker, 1994), and these are characteristics associated with the undercontrolled prototype.

There are several methodological limitations of this study that should be acknowledged. All assessments of personality and adjustment used self-report measures; the inclusion of peer or caregiver assessments, or more objective outcome criteria, would strengthen our confidence in our conclusions. It is also possible that medical indicators and symptom perception could be moderators of our conclusions. We had no such indicators in our study. A final caution is warranted by our finding that participants with follow-up assessments differed from those without follow-up data in age, time since injury, and type of lesion. It is possible that our conclusions regarding subsequent problem solving and acceptance of disability reflect nonresponse bias in our sample. Replication of these results in other SCI samples, with due regard for these limitations, is necessary before we can draw firm conclusions about the utility of prototype assessments for SCI rehabilitation. If the results are replicable, then research on targeted interventions among the different prototypes could prove valuable in helping to improve the lives of persons with SCI.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by funds awarded to T. R. Elliott from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Grant H133B980016A; the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health Grant T32 HD07420; and by Grant No. R49/CE 000191 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–National Center for Injury Prevention and Control to the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Injury Control Research Center. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Contributor Information

Jack W. Berry, UAB Injury Control Research Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham

Timothy R. Elliott, Department of Educational Psychology, Texas A & M University

Patricia Rivera, Birmingham Veterans Administration Medical Center, Birmingham, Alabama.

References

- Asendorpf JB, Borkenau P, Ostendorf F, van Aken MAG. Carving personality at its joints: Confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. European Journal of Personality. 2001;15:169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaranelli C. Evaluating cluster analysis solutions: An application to the Italian NEO Personality Inventory. European Journal of Personality. 2002;16:s43–s55. [Google Scholar]

- Block J. Studying personality the long way. In: Funder DC, Parke RD, Tomlinson-Keasey C, Widaman K, editors. Studying lives through time. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1993. pp. 9–41. [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Block J. The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior. In: Collins WA, editor. Minnesota symposium on child psychology. Vol. 13. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1980. pp. 39–101. [Google Scholar]

- Booth-Kewley S, Vickers RR. Associations between major domains of personality and health behavior. Journal of Personality. 1994;62:281–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botwin MD, Buss DM, Shackelford TK. Personality and mate preferences: Five factors in mate selection and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality. 1997;65:107–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourestom N, Howard M. Personality characteristics of three disability groups. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1965;46:626–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor N, Smith EE, French R, Mezzich J. Psychiatric diagnosis as prototype categorization. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1980;89:181–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.89.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A. Personality development across the life-course. In: Damon W, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 311–388. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Silva PA. Temperamental qualities at age three predict personality traits in yound adulthood: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Child Development. 1995;66:486–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RCK, Lee PWH, Lieh-Mak F. The pattern of coping in persons with spinal cord injuries. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2000;22:501–507. doi: 10.1080/096382800413998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P, Herbst JH, McCrae RR, Samuels J, Ozer DJ. The replicability and utility of three personality types. European Journal of Personality. 2002;16:S73–S87. [Google Scholar]

- Costa P, McCrae R. Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:668–678. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.38.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO–PI–R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO–FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho SA, Andrade MJ, Tavares MA, de Freitas JL. Spinal cord injury and psychological response. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1998;20:353–359. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)00047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkers MPJM. Quality of life of individuals with spinal cord injury: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and research findings. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2005;42:87–110. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2004.08.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, Maydeu-Olivares A. Social Problem-Solving Inventory–Revised (SPSI–R): Technical manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-health Systems, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- D'Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, Maydeu-Olivares A. Social problem solving: Theory and assessment. In: Chang E, D'Zurilla TJ, Sanna LJ, editors. Social problem solving: Theory, research, and training. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T. Social problem solving abilities and adjustment to recent-onset physical disability. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1999;44:315–352. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Bush B, Chen Y. Social problem solving abilities predict pressure sore occurrence in the first three years of spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2006;51:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Herrick S, MacNair R, Harkins S. Personality correlates of self-appraised problem-solving ability: Problem orientation and trait affectivity. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1994;63:489–505. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Herrick S, Patti A, Witty T, Godshall F, Spruell M. Assertiveness, social support, and psychological adjustment of persons with spinal cord injury. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1991;29:485–493. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(91)90133-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Kurylo M, Rivera P. Positive growth following an acquired physical disability. In: Snyder CR, Lopez S, editors. Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 687–699. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott TR, Rivera P, Berry J, Oswald K. Characteristic of family caregivers at-risk for depression; Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the Rehabilitation Psychology, Division 22, of the American Psychological Association; Reno, NV. 2006. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Umlauf R. Measurement of personality and psychopathology in acquired disability. In: Cushman L, Scherer M, editors. Psychological assessment in medical rehabilitation settings. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. pp. 325–358. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Uswatte G, Lewis L, Palmatier A. Goal instability and adjustment to physical disability. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2000;47:251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Fordyce WE. Personality characteristics in men with spinal cord injury as related to manner of onset of disability. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1964;45:321–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank RG, Chaney JM, Clay DL, Shutty MS, Beck NC, Kay DR, et al. Dysphoria: A major symptom factor in persons with disability or chronic illness. Psychiatry Research. 1992;43:231–241. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS, Hawley PH, Tucker JS. Personality, health, and longevity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1994;3:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Goodstein LD, Lanyon RI. Applications of personality assessment to the workplace: A review. Journal of Business and Psychology. 1999;13:291–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich RK. Dissertation Abstracts International. 12B. Vol. 56. 1996. Personality characteristics and vocational outcomes of men with spinal cord injuries (Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan, 1995) p. 7075. [Google Scholar]

- Holicky R, Charlifue S. Ageing with spinal cord injury: The impact of spousal support. Disability & Rehabilitation. 1999;21:250–257. doi: 10.1080/096382899297675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollick C, Radnitz CL, Silverman J, Tirch D, Birstein S, Bauman W. Does spinal cord injury affect personality? A study of monozygotic twins. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2001;46:58–67. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivistava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Elliott TR, Neilands TB, Morin SF, Chesney MA. A social problem-solving model of adherence to HIV medications. Health Psychology. 2006;25:355–363. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall P, Edinger J, Eberly C. Taylor's MMPI correction factor for spinal cord injury: Empirical endorsement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:370–371. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause JS. Personality and traumatic spinal cord injury: Relationship to participation in productive activities. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling. 1997;40:202–214. [Google Scholar]

- Krause JS, Rohe D. Personality and life adjustment after spinal cord injury: An exploratory study. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1998;43:118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kunce J, Worley B. Interest patterns, accidents, and disability. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1966;22:105–107. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(196601)22:1<105::aid-jclp2270220130>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkowski DC. A scale to measure acceptance of disability. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 1971;14:236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Linkowski DC. The Acceptance of Disability scale. Washington, DC: George Washington University; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Malec J. Personality factors associated with severe traumatic disability. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1985;30:165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Mawson AR, Biundo J, Clemmer D, Jacobs K, Ktasanes V, Rice J. Sensation-seeking, criminality, and spinal cord injury: A case-control study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1996;144:463–472. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR. The five factor model and its assessment in clinical settings. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1991;57:399–414. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5703_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa P. Personality, coping, and coping effectiveness in an adult sample. Journal of Personality. 1986;54:385–405. [Google Scholar]

- McSherry N, Davison K, Kosoff A, O'Connor LE, Berry JW. Distribution of basketball player's personality types: Bias against undercontrolled individuals. Paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Psychological Society; Los Angeles, CA. 2005. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Millon T. Personality disorders: Conceptual distinctions and classification issues. In: Costa P, Widiger T, editors. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 1994. pp. 279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Myers DG, Diener E. Who is happy? Psychological Science. 1995;6:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nagumo N. Relationships between low-grade chronic depression, pain, and personality traits among community-dwelling persons with traumatic spinal cord injury. Japanese Journal of Psychology. 2000;71:205–210. doi: 10.4992/jjpsy.71.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal cord injury: Facts and figures at a glance. 2006 Retrieved October 15, 2006, from http://www.spinalcord.uab.edu.

- Rammstedt B, Riemann R, Angleitner A, Borkenau P. Resilients, overcontrollers, and undercontrollers: The replicability of the three personality prototypes across informants. European Journal of Personality. 2004;18:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, John OP, Caspi A. The typological approach for studying personality. In: Cairns RB, Bergman LR, Kagan J, editors. Methods and models for studying the individual. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 135–160. [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, John OP, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled boys: Three replicable personality types. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:157–171. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohe DE, Athelstan GT. Vocational interests of persons with spinal cord injury. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1982;29:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Rohe DE, Krause JS. The five-factor model of personality: Findings in males with spinal cord injury. Assessment. 1999;6:203–213. doi: 10.1177/107319119900600301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel K, Asendorpf JB, Ostendorf F. Replicable types and subtypes of personality: German NEO–PI–R versus NEO–FFI. European Journal of Personality. 2002;16:s7–s24. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. Moderator-variable effect on personality test item endorsements of physically disabled patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1970;35:183–188. doi: 10.1037/h0030127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple R, Elliott T. Personality disorder characteristics and adjustment following spinal cord injury. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. 2000;6(1):54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson N, Coker JL, Krause JS, Henry E. Purpose in life as a mediator of adjustment after spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2003;48:100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Trieschmann R. Spinal cord injuries: Psychological, social and vocational adjustment. New York: Pergamon; 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters RL, Adkins R, Yakura J, Sie I. Donald Munroe lecture: Functional and neurologic recovery following acute spinal cord injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 1998;21:195–199. doi: 10.1080/10790268.1998.11719526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Frances AJ. Toward a dimensional model of the personality disorders. In: Costa PT, Widiger TA, editors. Personality disorders and the Five–Factor model of personality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1994. pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Coryell W. The Inventory to diagnose depression (IDD): A self-report scale to diagnose major depressive disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:55–59. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Coryell W, Corenthal C, Wilson S. A self-report scale to diagnose major depressive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:1076–1081. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800110062008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Coryell W, Wilson S, Corenthal C. Evaluation of symptoms of major depressive disorder: Self-report vs. clinicians ratings. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1986;174:150–153. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]