Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The objective of the study was to assess the incidence of and risk factors for pelvic floor repair (PFR) procedures after hysterectomy.

STUDY DESIGN

Using the Rochester Epidemiology Project database, we tracked the incidence of PFRs through June 2006 among 8220 Olmsted County, MN, women who had a hysterectomy for benign indications between 1965 and 2002.

RESULTS

The cumulative incidence of PFR after hysterectomy was 5.1% by 30 years. This risk was not influenced by age at hysterectomy or calendar period. Future PFR was more frequently required in women who had prolapse, whether they underwent a hysterectomy alone (eg, vaginal [hazard ratio (HR) 4.3; 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.5 to 7.3], abdominal [HR 3.9; 95% CI 1.9 to 8.0]) or a hysterectomy and PFR (ie, vaginal [HR 1.9; 95% CI 1.3 to 2.7] or abdominal [HR 2.9; 95% CI 1.5 to 5.5]).

CONCLUSION

Compared with women without prolapse, women who had a hysterectomy for prolapse were at increased risk for subsequent PFR.

Keywords: epidemiology, posthysterectomy, prolapse, risk factors

Pelvic organ prolapse is common and a major indication for gynecologic surgery in the United States. It is estimated that United States women have an 11% lifetime risk of surgery for prolapse or incontinence.1 Indeed, approximately 200,000 operations for prolapse are performed annually in this country, with a cost exceeding $1 billion.2,3 Consequently, it is important to identify the factors that contribute to this problem to improve on both its prevention and treatment. Several risk factors have been proposed to initiate, aggravate, or contribute to decompensation in pelvic organ prolapse.4 These include increasing age, higher gravidity and parity, obesity, conditions associated with increased intraabdominal pressure (eg, constipation), and prior hysterectomy.1,5,6 The latter is particularly important because hysterectomy is second only to cesarean section as the most frequently performed major operation among women in this country7 and because it has been estimated that up to one-third of operations for pelvic organ prolapse are repeat procedures.1

The extent to which hysterectomy is a risk factor for pelvic organ prolapse is unclear, however. Although a case-control study suggested that hysterectomy was a risk factor for severe pelvic organ prolapse,8 the overall incidence of severe pelvic organ prolapse following hysterectomy (ie, 2 to 3.6 per 1000 woman-years)5 is similar to the rates of surgically corrected pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence in the general population (ie, 2.04 to 2.63 per 1000 women-years).1,5 Nonetheless, the indication and route of hysterectomy may influence the subsequent risk of pelvic organ prolapse. Thus, the risk of prolapse following a hysterectomy was 5.5 times higher5 in women whose initial hysterectomy was for genital prolapse, compared with other indications. Because a vaginal hysterectomy is preferred for women with prolapse, it has been suggested that recurrent prolapse is more common after vaginal than after abdominal hysterectomy.9 However, this concept is disputed by a case series, which observed a similar rate of posthysterectomy prolapse and enterocoele after vaginal and abdominal hysterectomy.10

These figures have incompletely characterized the incidence of pelvic floor repair (PFR) after hysterectomy as well as the risk factors for these procedures following hysterectomy, particularly the interactions between surgical indications and route of surgery. An accurate appraisal of the current utilization of PFR after a hysterectomy is particularly important to plan future health care needs in our aging population. Indeed, it has been estimated that in the United States, the demand for health care services related to pelvic floor disorders will increase at twice the rate of growth of the population itself.11 To explore these issues in greater detail, we examined the utilization rate for PFR procedures in a large cohort of community women from Olmsted County, MN, who had a hysterectomy between 1965 and 2002, including women who underwent concomitant PFR at the time of hysterectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Medical care in Olmsted County, located in the southeastern part of Minnesota, is virtually self-contained within the community, thus allowing population-based epidemiologic research into the incidence and determinants of diverse diseases and therapeutic interventions.12 This retrospective population-based cohort study utilized the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), which indexes and links the medical records of the medical providers who serve Olmsted County, Mayo Medical Center (ie, Mayo Clinic and its affiliated hospitals [Rochester Methodist and St Marys]), and Olmsted Medical Center (ie, Olmsted Medical Group and its affiliated Olmsted Community Hospital). Because these institutions provide nearly all of the primary, secondary, and tertiary care for this population, the result is a unique resource for population-based epidemio-logic research.12 The REP database, which contains both inpatient and out-patient data, is easily retrieved because the diagnoses and surgical procedures entered into these records are indexed.

Case identification

Following approval by the Institutional Review Boards of both Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center, we used the REP database to identify all Olmsted County residents who underwent hysterectomy, either as a single procedure or along with PFR procedures, between January 1, 1965, and December 31, 2002.13 Nonresidents who underwent hysterectomy at the institutions mentioned in earlier text were not included. Of the 9893 hysterectomies in this original cohort, 615 patients (6%) who did not authorize use of their medical records for research 14 were excluded. We also excluded 899 patients who had hysterectomy for malignant disease, 50 women who had laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy,13 and 109 women who had PFR prior to hysterectomy.

The remaining 8220 women who had a hysterectomy for benign indications were included for further analysis. These women were followed forward in time for the occurrence of any PFR or until death or the date of last clinical contact through June 2006. The procedure type and indications were identified electronically using the Berkson coding system from Jan. 1, 1965, to Dec. 31, 1987, and the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) procedural codes from Jan. 1, 1988, to Dec. 31, 2002, as described in earlier text13 and delineated in Table 1. Consistent with previous reports, we did not include procedures for stress urinary incontinence (eg, sling operations or injection of implant into urethra and/or bladder neck, etc) as PFR procedures.3,15 However, prior to 1988, a single code from the Berkson system did not distinguish vaginal PFR procedures from retropubic operations for stress urinary incontinence; consequently, some retropubic operations for stress urinary incontinence may have been categorized as PFR procedures prior to 1988.

TABLE 1.

Procedure codes for hysterectomy and pelvic floor repair, ICD-9-CM, and Berkson codes

| Procedure | ICD —9-CM codes (1988-2002) |

Berkson codes (1965-1987) |

|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy | ||

| Subtotal hysterectomy | 68.3 | 4694, 4695 |

| Total abdominal hysterectomy | 68.4 | 4680, 4690 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 68.5,68.59 | 4700 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy with repair of multiple pelvic relaxation conditions | NA | 4710 |

| Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy | 68.51 | NA |

| Radical abdominal hysterectomy | 68.6, 68.7 | 4720 |

| Other and unspecified hysterectomy | 68.9 | |

| Uterine suspensions | 69.21, .22, .23, .29 | 4670 |

| Pelvic floor repair | ||

| Repair of cystocele, urethrocele | 70.51 | 4990a |

| Repair of cystocele and rectocele | 70.50 | 4994 |

| Repair of rectocele | 70.52 | 4980 |

| Vaginal construction and reconstruction | 70.6, 70.61, 70.62 | 4994 |

| Vaginal suspension and fixation/other operations cul-de-sac | 70.77, 70.92 | 4994 |

| Obliteration of the vaginal vault (LeFort operation) | 70.8 | 4994 |

| Colpoperineoplasty | 70.79 | 4980 |

NA, not applicable.

Code 4990 refers to “plastic vaginal operation,” which includes Fenton’s, Kennedy, Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz, enterocele repair, cystocele repair, and vaginal septum division.

In 172 randomly women randomly selected from throughout the whole study period, the procedure type in the electronic record system was manually compared with the procedure type listed in the surgical note; these 2 sources agreed in 95% of cases. Consistent with the focus of this study, the indication for hysterectomy was categorized into 2 groups (ie, with or without prolapse) based on the final postoperative findings. The diagnoses included in the prolapse category are provided in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Berkson, HICDA, and ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes for pelvic organ prolapse

| Diagnoses | Berkson | HICDAa | ICD-9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uterine prolapse | 014652, 014641 | 623.4 | 618.1, 618.2, 618.3, 618.4 |

| Vaginal prolapse | 014653 | 623.9 | 618.0 |

| Cystocele | 014684 | 623.0 | 618.01, 618.02 |

| Rectocele | 014691 | 623.1 | 618.04 |

| Urethrocele | 146914 | 623.2 | 618.03 |

| Enterocele | 014844 | 623.3 | 618.6 |

| Pelvic floor relaxation | 07859120 07859122 |

NA | 618.89 |

| Prolapse of vaginal vault after hysterectomy |

NA | 623.1210b 623.0610b |

618.5 |

NA, not applicable.

From 1975 to 1993, diagnosis coding was based on the Hospital Adaptation of the International Classification of Diseases, Second Edition (HICDA); not used for surgical index purposes.

Mayo Clinic—modified code.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was carried out using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). The cumulative incidence of PFR after hysterectomy (1 minus the probability of survival free of PFR) for specific subgroups was estimated for up to 30 years following the index date (date of hysterectomy) using product-limit methods.16 The relative risks (hazard ratios [HRs]) of a subsequent PFR after hysterectomy were estimated for age, indication for hysterectomy (ie, prolapse vs no prolapse), type of hysterectomy (ie, abdominal or vaginal, with or without concomitant PFR), and calendar period, using univariate and multiple variable Cox proportional hazards models.17

For the univariate models, the HRs (and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) were estimated relative to the reference group for that category (eg, age 35 years old or younger). In the multiple variable model, the risk for a subsequent PFR was expressed relative to the risk for women who had an abdominal hysterectomy alone for nonprolapse indications adjusted for age and calendar period (as continuous covariates). Although this analysis considered all events over the entire period of follow-up, point estimates of cumulative incidence were tabulated at 20 years after hysterectomy to provide robust estimates based on sufficient numbers of subjects still at risk.

RESULTS

During the 38-year study period, 5336 hysterectomies (65%) were performed as a single procedure, whereas 2884 hysterectomies (35%) were combined with a PFR. The cumulative incidence of PFR after hysterectomy was 3.3% (95% CI 2.8 to 5.9) at 20 years and 5.1% (95% CI, 4.3 to 5.9) by 30 years. The estimated cumulative incidence of a subsequent PFR procedure was higher (ie, 6.7%) among women who had a combined procedure (ie, hysterectomy plus PFR) than among women who had a hysterectomy alone (ie, 3.9%) at the initial operation (P = .007, log rank test).

Approximately 2000 hysterectomies were performed among Olmsted County women in each calendar period (Table 3). The proportion of women who had prolapse indications was greatest in the 1965-1974 and 1975-1984 calendar periods. Thereafter, age distributions and indications for hysterectomy were comparable across time. The proportion of women who had a concurrent PFR procedure declined from 47% in 1965-1974 to 27% in 1995-2002.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of age, indications, and procedure type among 8220 women undergoing hysterectomy in Olmsted County, MN, 1965-2002a

| Calendar period |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | 1965-1974 | 1975-1984 | 1985-1994 | 1995-2002 |

| nb | 2016 | 2037 | 2204 | 1963 |

| Age, y (median, range) | 42 (14, 91) | 42 (12, 93) | 43 (12, 90) | 45 (11, 92) |

| Indications | ||||

| No prolapse | 1010 (50.1) | 1264 (62.1) | 1439 (65.3) | 1296 (66.0) |

| Prolapse | 1006 (49.9) | 773 (38.0) | 765 (34.7) | 667 (34.0) |

| Procedure type | ||||

| Vaginal hysterectomy alone | 267 (13.2) | 487 (23.9) | 720 (32.7) | 695 (35.4) |

| Abdominal hysterectomy alone | 793 (39.3) | 793 (38.9) | 843 (38.3) | 738 (37.6) |

| Vaginal hysterectomy plus PFR | 904 (44.8) | 654 (32.1) | 578 (26.2) | 510 (26.0) |

| Abdominal hysterectomy plus PFR | 52 (2.6) | 103 (5.1) | 63 (2.9) | 20 (1.0) |

Except for age, all figures are n (percent) for calendar period (percentage per category per column).

n = number of subjects per calendar period.

Table 4 provides univariate risk factors for a PFR procedure after a hysterectomy. The HRs were calculated over the entire study period. However, because follow-up began in 1965, the cumulative incidence and 95% CI for each risk factor can be calculated more precisely at 20 rather than 30 years after hysterectomy. The univariate HRs are expressed relative to the appropriate reference group in that category. Univariate analysis suggested that age and the calendar period of hysterectomy were not significantly associated with the risk for a subsequent PFR procedure. However, women who had prolapse at the initial operation were more likely (HR 2.5; 95% CI 1.8 to 3.3) to undergo a PFR procedure in future.

TABLE 4.

Risk factor distribution and corresponding univariate HRs for subsequent pelvic floor repair procedures among Olmsted County, MN, women undergoing hysterectomy (hys) with or without PFR, 1965-2002

| Risk factora | Categories | nb | Number at risk at 20 years |

Cumulative incidence % (95% CI) of PFR at 20 years |

Univariate HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 35 or younger | 1570 | 562 | 3.1 (2.0, 4.2) | 1.0 (ref) |

| 36-45 | 3424 | 1238 | 3.5 (2.7, 4.3) | 1.11 (0.76, 1.62) | |

| 46-60 | 2381 | 821 | 2.9 (2.0, 3.9) | 1.00 (0.66, 1.51) | |

| 60 or older | 845 | 148 | 3.6 (1.8, 5.5) | 1.27 (0.73, 2.22) | |

| Indication | No prolapse | 5009 | 1522 | 1.9 (1.4, 2.5) | 1.0 (ref) |

| Prolapse | 3211 | 1247 | 5.1 (4.1, 6.0) | 2.47 (1.85, 3.29) | |

| Procedure | Vaginal hys only | 2169 | 572 | 2.9 (1.9, 3.0) | 1.14 (0.76, 1.71) |

| Abdominal hys only | 3167 | 1004 | 2.3 (1.6, 3.1) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Vaginal hys with PFR | 2646 | 1081 | 4.3 (3.3, 5.2) | 1.64 (1.19, 2.28) | |

| Abdominal hys with PFR | 238 | 112 | 5.7 (2.2, 9.2) | 2.11 (1.11, 4.03) | |

| Time period | 1965-1974 | 2016 | 1322 | 4.0 (3.0, 4.9) | 1.0 (ref) |

| 1975-1984 | 2037 | 1315 | 3.0 (2.1, 3.8) | 0.79 (0.56, 1.10) | |

| 1985-1994 | 2204 | 132 | 2.4 (1.6, 4.1) | 0.74 (0.50, 1.09) | |

| 1995-2002 | 1963 | 133 | 1.3 (0.6, 3.0)c | 1.23 (0.66, 2.29) |

All risk factors determined at hysterectomy.

n = number of subjects in category.

10 year estimate.

The risk for a subsequent PFR procedure was also influenced by the type of initial operation. Thus, compared with the reference group (ie, women who had an abdominal hysterectomy only), women who had a combined procedure, either vaginal (HR 1.6; 95% CI 1.2 to 2.3) or abdominal (HR 2.1; 95% CI 1.1 to 4.0), had an increased risk for a subsequent PFR procedure.

Multiple variable proportional hazards regression models explored the interactions among risk factors (ie, type of procedure and indication) for a subsequent PFR (Table 5). The final model included age and calendar period. However, interactions between age or calendar period and other factors (ie, type of procedure and indication) were not significant and therefore not included in the final model. This model used women who had no prolapse and an abdominal hysterectomy only as a reference group. Extending the univariate analysis, this model demonstrates that the risks for a second PFR were higher in women who had a combined procedure for prolapse, either vaginal (HR 1.9; 95% CI, 1.3 to 2.7) or abdominal (HR 2.9; 95% CI, 1.5 to 5.5), for pro-lapse. The risks of a PFR in the future were even higher in women who had a vaginal (HR 4.3; 95% CI, 2.5 to 7.3) or abdominal (HR 3.9; 95% CI, 1.9 to 8.0) hysterectomy alone for prolapse. Among women who had a combined procedure but no prolapse at the initial operation, none required a PFR procedure subsequently.

TABLE 5.

Multiple variable analysis of risk factors for subsequent pelvic floor repair among Olmsted County women undergoing hysterectomy, 1965-2002

| Risk factor (n) | Number at risk at 20 ya |

Cumulative incidence at 20 y, % (95% CI) |

HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 1 y) (n = 8220) | NA | NA | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | .84 |

| Years since procedure (year 1965 = 0) (n = 8220) | NA | NA | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | .30 |

| Procedure type/indication | ||||

| Hys only/abdominal/no prolapse (n = 2942) | 990 | 2.1 (1.3, 2.8) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Hys only/vaginal/no prolapse (n = 1905) | 486 | 1.9 (1.0, 2.8) | 0.81 (0.48, 1.35) | .41 |

| Hys plus PFR/abdominal/no prolapse (n = 43)b | 17 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Hys plus PFR/vaginal/no prolapse (n = 119)b | 29 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Hys only/abdominal/prolapse (n = 225) | 14 | 5.2 (1.7, 13.6) | 3.88 (1.87, 8.04) | .0003 |

| Hys only/vaginal/prolapse (n = 264) | 86 | 9.5 (5.1, 14.6) | 4.30 (2.53, 7.31) | < .0001 |

| Hys plus PFR/abdominal/prolapse (n = 195) | 95 | 6.7 (2.5, 10.8) | 2.87 (1.49, 5.52) | .002 |

| Hys plus PFR/vaginal/prolapse (n = 2527) | 1052 | 4.4 (3.4, 5.4) | 1.87 (1.3, 2.66) | .0005 |

Hys, hysterectomy; NA, not applicable.

n, number of women with the risk factor.

No events occurred in these groups.

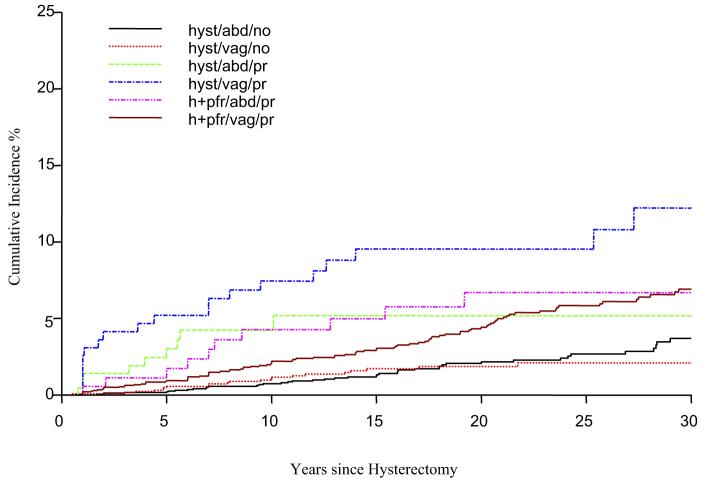

The Figure illustrates that among women who had a vaginal hysterectomy alone for prolapse, the cumulative incidence of recurrent prolapse, as evidenced by the need for a PFR, was 7.4% (95% CI, 3.6 to 11.2) at 10 years and increased thereafter to 9.5% (95% CI, 5.1 to 14.6) at 20 years and 12.2% at 30 years (95% CI, 6.4 to 18.3) after hysterectomy. For women who originally had a combined vaginal hysterectomy and PFR for prolapse, the cumulative incidence of a second PFR was lower but also increased between 10 and 30 years after hysterectomy (ie, 2.0 (95% CI 1.4 to 2.6) at 10 years, 4.4 (95% CI 3.4 to 5.4) at 20 years, and 6.9 (95% CI 5.4 to 8.4) at 30 years. For the remaining combinations, the risks plateaued by 20 years after hysterectomy.

FIGURE. Cumulative incidence (percent) of any pelvic floor repair among 8220 Olmsted County, MN, women following a hysterectomy.

Cumulative incidence (percent) of any pelvic floor repair among 8220 Olmsted County, MN, women following a hysterectomy, 1965-2002. abd, abdominal; hyst or h, hysterectomy; no, no prolapse; pfr, pelvic floor repair; pr, prolapse; vag, vaginal.

COMMENT

More than 200,000 operations for pelvic organ prolapse are performed annually in the United States.2,3 In 1 series, 60% of patients undergoing surgery for prolapse previously had a pelvic operation, either a previous PFR with or without hysterectomy (29%), a hysterectomy not for prolapse (24%), or a hysterectomy for an unknown indication (7%).1 These data suggest that hysterectomy may be a risk factor for pelvic organ prolapse. Indeed, a population-based study observed that the cumulative risk of surgically treated prolapse after hysterectomy increased linearly over time to 5% at 15 years.5 In that study, the incidence of a repair procedure after hysterectomy was on average 5.5-fold higher for women who had a hysterectomy for prolapse. However, the study was conducted in women who were selected from family practice clinics in the United Kingdom; the average follow-up was only 7.9 years after hysterectomy, and the oldest subject at follow-up was 65 years.

In the United States, temporal trends in PFR procedures but not the relationship to antecedent hysterectomy have been characterized from the National Hospital Discharge Survey database.3 Systematic searches of Medline (1966-2006) and PubMed databases using the key words “hysterectomy” in combination with “prolapse surgery” or “pelvic floor repair” and “population” and “United States” suggest that this is the first population-based study in the United States to evaluate the incidence and risk factors for PFR procedures after a hysterectomy.

Our data demonstrate that the proportion of women who had a PFR procedure after a hysterectomy increased over time and was 3.3% at 20 years and 5.1% at 30 years after the operation. The cumulative incidence of a subsequent PFR procedure was influenced by the indication for the initial hysterectomy and by the type of procedure. Similar to the Oxford Family Planning Association Study cohort,5 women who had prolapse at the time of hysterectomy were more likely than women who did not have pro-lapse to require a PFR in the future. Indeed, among women who did not have prolapse at hysterectomy, the cumulative probability of requiring a PFR procedure 20 years after hysterectomy alone and a combined procedure was 2% and 0%, respectively.

The extremely low incidence of PFR procedures among women who did not have prolapse during the initial hysterectomy argues against the concept that a hysterectomy per se may predispose to pelvic organ prolapse by disrupting uterine ligamentous supports.18,19 Moreover, prolapse can occur even when the uterine ligaments are spared (ie, supracervical hysterectomy).20 Rather, our data suggest that the indication for hysterectomy (ie, pelvic organ prolapse) is a more important risk factor for a subsequent PFR. Indeed, the risk of subsequent PFR was at least 2-fold higher if the hysterectomy was indicated for prolapse. In addition, among women who had prolapse, the incidence of a subsequent PFR was lower after vaginal hysterectomy and PFR, compared with vaginal hysterectomy alone, suggesting that concurrent PFR may protect against recurrent prolapse in patients with prolapse undergoing vaginal hysterectomy.

The decline in the incidence of concomitant procedures may be related to the fall in the proportion of women in whom a hysterectomy was indicated for uterine/vaginal prolapse (ie, from 50% between 1965 and 1974 to 34% between 1985 and 2002). The apparent inconsistency between the indication (ie, no pro-lapse) and procedure (ie, hysterectomy and PFR) in some instances is probably because gynecological surgeons at the Mayo Clinic often performed a prophylactic culdoplasty, which was coded as a PFR procedure during vaginal hysterectomy.10,21

There are several potential caveats to our observations. It is unclear whether these findings, which were derived from a predominantly white population in Olmsted County, can be generalized to other races. Moreover, approximately 60% of the hysterectomies in Olmsted County were performed by the vaginal route,13 which is similar to the reported rate of 40-50% in France and Australia22,23 but higher than the 25% rate reported elsewhere in this country.24

Perhaps because it is more challenging to restore fascial and ligamentous integrity during vaginal than abdominal procedures,25 enterocele formation and posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse are more common after vaginal than abdominal hysterectomy.9 Therefore, the higher utilization of vaginal hysterectomy may be anticipated to predispose to a higher incidence of organ prolapse after hysterectomy and subsequent PFR in Olmsted County.

Because we included all patients with any prolapse in 1 category, it is not clear whether the risk of subsequent PFR was influenced by the stage of prolapse. Moreover, because patients with less severe prolapse may not seek surgical treatment, the PFR utilization rate does not correspond to the incidence of pelvic organ prolapse; although it is conceivable that patients who had a hysterectomy in Olmsted County subsequently had pelvic floor repair procedures done at another medical facility. Indeed, the Women’s Health Initiative study observed that 63% of older women with a uterus had stage II prolapse.26 Further studies are necessary to assess how other risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse not assessed in this study (eg, gravidity, parity, obesity, and increased intraabdominal pressure) influence the risk for PFR after hysterectomy.

Despite these limitations, our data are useful for predicting future trends in PFR procedures. In the National Hospital Discharge Summary Database, the age-adjusted utilization of PFR procedures was stable between 1979 and 1997.3 Fewer procedures were performed in younger women, whereas more procedures were performed in older women. It has been suggested that the number of PFR procedures will increase as the baby boomer generation ages.27 Our data suggest that women may have a PFR for up to 30 years after a hysterectomy. Because the proportion of hysterectomies for prolapse declined between 1965 and 1974 and 1975 and 1984 and have remained stable thereafter, we anticipate that the need for PFR procedures after hysterectomy will perhaps remain stable or decline and is unlikely to increase substantially in the near future.

Footnotes

Presented at the 33rd Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, Orlando, FL, April 12-14, 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501–6. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subak LL, Waetjen LE, van den Eeden S, Thom DH, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS. Cost of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:646–51. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States, 1979-1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:108–15. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bump RC, Norton PA. Epidemiology and natural history of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1998;25:723–46. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mant J, Painter R, Vessey M. Epidemiology of genital prolapse: observations from the Oxford Family Planning Association Study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:579–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1160–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall MJ, Owings MF. 2000 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Advance Data. 2002:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swift SE, Pound T, Dias JK. Case-control study of etiologic factors in the development of severe pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12:187–92. doi: 10.1007/s001920170062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swift SE. The distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjects seen for routine gynecologic health care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:277–85. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Symmonds RE, Williams TJ, Lee RA, Webb MJ. Posthysterectomy enterocele and vaginal vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140:852–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luber KM, Boero S, Choe JY. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: current observations and future projections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1496–501. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.114868.; discussion 1501-3.

- 12.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babalola EO, Bharucha AE, Schleck CD, Gebhart JB, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Decreasing utilization of hysterectomy: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1965-2002. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(214):e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.10.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melton LJ., 3rd The threat to medical records research. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1466–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JS, Waetjen LE, Subak LL, Thom DH, Van den Eeden S, Vittinghoff E. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States, 1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:712–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan EL, Meir P. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox D. Regression models and life-tables. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waters EG. Vaginal prolapse; technic for correction and prevention at hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1956;8:432–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter K. Massive eversion of the vagina: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy of the “true” prolapse of the vaginal stump. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1982;25:897–912. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198212000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phaneuf LE. Inversion of the vagina and prolapse of the cervix following supracervical hysterectomy and inversion of the vagina following total hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1952;64:739–45. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)38793-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCall ML. Posterior culdoplasty; surgical correction of enterocele during vaginal hysterectomy; a preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol. 1957;10:595–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yusuf F, Siedlecky S. Hysterectomy and endometrial ablation in New South Wales, 1981 to 1994-1995. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;37:210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1997.tb02256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapron C, Laforest L, Ansquer Y, et al. Hysterectomy techniques used for benign pathologies: results of a French multicentre study. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2464–70. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.10.2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lepine LA, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, et al. Hysterectomy surveillance—United States, 1980-1993. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1997;46:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill EJ, Hurt WG. Pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1998;25:757–69. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nygaard I, Bradley C, Brandt D. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: prevalence and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:489–97. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000136100.10818.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber AM, Richter HE. Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:615–34. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000175832.13266.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]