Abstract

Hypercalcemia associated with malignancy has been attributed to osteolytic processes secondary to bony metastases and to humoral factors causing increased bone resorption and decreased renal excretion of calcium. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTH-rP) is a humoral factor that has been associated with hypercalcemia in renal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and bladder carcinoma. Hypercalcemia does occur in patients with melanoma; however, few studies have reported on hypercalcemia in these patients, and even fewer have described a direct connection to PTH-rP. We here report a patient with stage IV malignant melanoma presenting with severe hypercalcemia associated with elevated PTH-rP levels. Immunohistochemistry showed strong expression of PTH-rP in biopsy of the patient's subcutaneous masses. In addition, we found a 4.9% incidence of hypercalcemia in 1,146 consecutive patients treated for metastatic melanoma at the Surgery Branch of the National Cancer Institute between January 1, 1988 and March 31, 2000. Thus, PTH-rP may play a significant role in severe hypercalcemia in patients with metastatic melanoma. The discovery of PTH-rP and relevant literature will also be reviewed.

Keywords: Metastatic melanoma, Hypercalcemia, Parathyroid hormone-related protein, PTH-rP

Hypercalcemia is a rare, but potentially life-threatening consequence of metastatic melanoma. The incidence of hypercalcemia in patients with metastatic melanoma varies depending on the series. Burt and Brennan1 reported a 1.1% incidence in 560 patients with melanoma treated at the National Institutes of Health between 1970 and 1977. Levy and Feun2 found a similar 2.1% incidence in their series of 143 patients. In a recent article by Kageshita and colleagues,3 11.9% (7 of 59) of patients with metastatic melanoma were found to have hypercalcemia, suggesting that hypercalcemia may be more common than previously thought in patients with metastatic melanoma.

As early as 1941, Fuller Albright proposed a humoral form of hypercalcemia and commented on the possible role of tumor cells secreting parathyroid hormone (PTH) or a PTH-like peptide.4 Twenty-five years later, Berson and Yalow5 used radioimmunoassays for PTH and found significant elevations in what appeared to be PTH in unselected cancers. However, the levels did not seem high enough to cause the corresponding degree of hypercalcemia as seen in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism.

In 1971, Riggs and colleagues compared hypercalcemia in patients with either nonparathyroid carcinoma or primary hyperparathyroidism and found the degree of hypercalcemia greater in the cancer group than the primary hyperparathyroidism group.6 However, the hyperparathyroid group had lower concentrations of an apparently different compound with radioimmunologic properties that were different from, but similar to, those of PTH. Two years later, Powell and colleagues7 evaluated hypercalcemia in patients with malignancy, and using multiple radioimmunoassays to detect PTH, pro-PTH, and PTH fragments, they were unable to detect any evidence of such peptides, despite the presence of PTH-like activity. From this they concluded that a humoral substance other than PTH was responsible for the hypercalcemia in these patients. In 1983, Rodan and coworkers observed that a peptide analog of PTH blocked the biologic activity of the yet-to-be-elucidated PTH-related protein (PTH-rP).8 However, pretreatment with PTH antisera did not block its activity. This led to the conclusion that whatever was causing the elevation in calcium acted at the PTH receptor, but was immunologically distinct from PTH.

In the years after this, others were unable to detect mRNA for PTH in tumors associated with humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy.9 With the establishment of a cell line derived from a human squamous cell carcinoma, purification of the active factor was reported, and in 1987, PTH-rP was eventually purified, sequenced, and the gene encoding it was cloned.10

The gene for this peptide is a complex transcriptional unit that, when spliced accordingly, gives rise to three distinct but related PTH-rPs.11 Each of these is identical through the first 139 residues and bears 60% homology to PTH between residues 1 and 13.12

CASE REPORT

A 30-year-old woman with history of a primary back cutaneous melanoma presented with metastases to the liver and multiple subcutaneous masses. She was initially diagnosed 5 years earlier during pregnancy after presenting with changes in an abnormal mole. Wide-local excision showed a 1.4-mm-depth melanoma. Three years after the initial diagnosis, a right axillary mass developed and she underwent right axillary node dissection, with 1 of 15 lymph nodes showing metastatic melanoma. Four months after starting adjuvant α-interferon, she developed another right axillary mass. She was then treated with biochemotherapy (α-interferon, subcutaneous low-dose interleukin-2, cisplatin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) and remained stable for 3 months. The right axillary mass was subsequently resected, followed by external beam radiation to the surgical bed.

Two weeks before referral to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), multiple subcutaneous metastases from 0.5 cm to 3.0 cm in diameter developed throughout her scalp, upper extremities, breasts, and trunk. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed new liver metastases; magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and bone scan showed no other disease sites. She signed informed consent and was enrolled in a protocol (approved by NCI Institutional Review Board) using high-dose intravenous interleukin-2 and immunization against the tyrosinase:206–214 peptide.

Routine pretherapy laboratory evaluation showed significant hypercalcemia (Table 1) with ionized calcium nearly two times normal. Interestingly, calcium levels drawn by her referring oncologist 4 weeks earlier (before the newly documented metastases) were normal. The patient was mildly symptomatic and reported some fatigue, anorexia, and constipation during the prior several weeks. She was treated with intravenous hydration, diuresis, and pamidronate, and therapy with vaccine and intravenous interleukin-2 continued as planned. Her calcium levels were followed serially and became normal by the fifth day after pamidronate therapy.

TABLE 1.

Patient's laboratory values

| Test | Result | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium | ||

| Total | 4.06 mmol/L | 2.05–2.50 mmol/L |

| Ionized | 2.23 mmol/L | 1.17–1.31 mmol/L |

| Phosphorus | 3.0 mg/dl | 2.3–4.3 mg/dl |

| Vitamin D | ||

| 25-OH Total |

29 ng/ml | 8–38 ng/ml (winter) |

| 25-OH D2 | <1 ng/ml | |

| 25-OH D3 | 29 ng/ml | |

| (1,25)-(OH)2 | 17 pg/ml | 15–60 pg/ml |

| TSH | 0.83 μIU/ml | 0.43–4.60 μIU/ml |

| Free T4 | 1.3 ng/dl | 0.9–1.6 ng/dl |

| PTH, intact | 8.4 pg/ml | 10–65 pg/ml |

| PTH-rP | 3.4 pmol/l | <1.3 pmol/l |

PTH, parathyroid hormone; rP, related protein; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone

Because the patient did not have evidence of bone metastases at that time, a workup for other possible causes of hypercalcemia was done (Table 1). Serum phosphorus, vitamin D, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and free T4 levels were normal. Intact PTH level was decreased. In addition, PTH-rP was tested and found to be elevated at 3.4 pmol/l (Quest/Nichols Institute, San Capistrano, CA, U.S.A.).

The patient was seen in clinic 3 weeks after starting vaccine/interleukin-2 therapy and was found to have progressive disease in her subcutaneous sites. Because of the onset of new back pain, magnetic resonance imaging of the spine was obtained and showed diffuse metastases in the thoracic and lumbar vertebral bodies. Her calcium level was slightly elevated at 2.69 mmol/l (normal 2.05–2.50 mmol/l), and she was treated again with intravenous hydration and pamidronate. She was then taken off protocol and referred for radiation to the spine for control of back pain. During the subsequent several weeks, she continued to have progressive disease and developed confusion, worsening hypercalcemia up to 5.12 mmol/l, as well as new brain and skull metastases, and she soon died.

PATHOLOGY AND RESULTS

To correlate the production of the elevated PTH-rP in serum to the production of PTH-rP by the melanoma metastases, immunohistochemistry was performed on excisional biopsies of the patient's subcutaneous metastases. The antibody used was rabbit antihuman PTH-rP residues 1 to 34 (Bachem/Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA, U.S.A.). Multiple determinations on separate days were performed on an automated Ventana Immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tuscon, AZ, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Both microwaving in citrate buffer antigen retrieval and non-antigen retrieval determinations were run in parallel, with antigen-retrieval yielding superior staining.

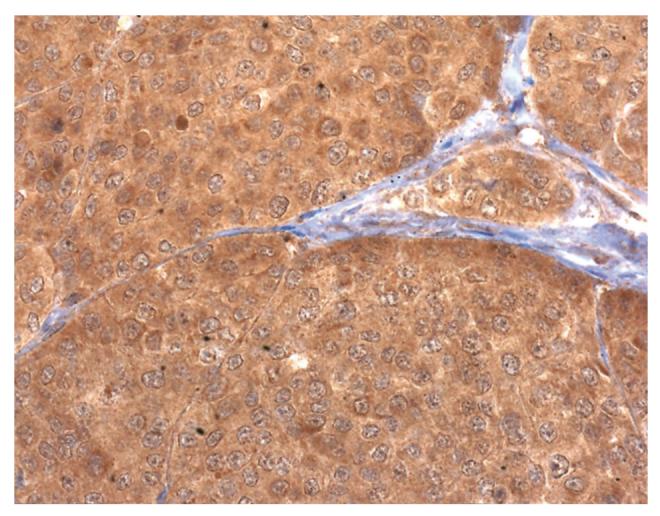

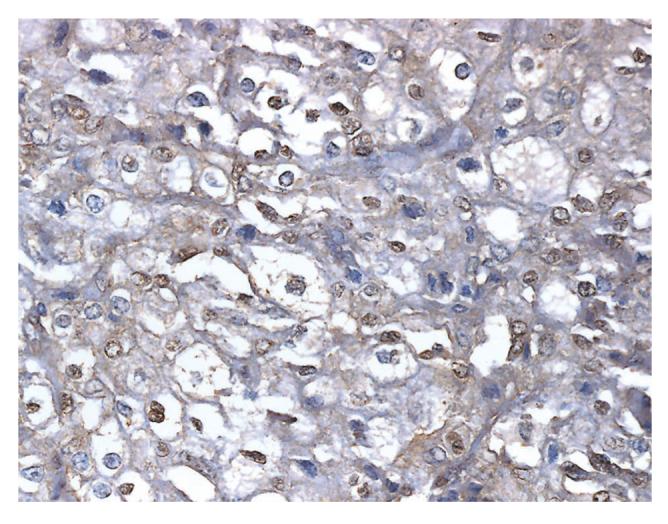

The patient's subcutaneous metastases were found to strongly express PTH-rP (Fig. 1). To compare the PTH-rP expression in patients with melanoma without hypercalcemia, immunohistochemistry was also performed on metastatic melanoma biopsies from three patients. PTH-rP was found not to be expressed in these control patients (Fig. 2). Thus, the PTH-rP in our patient seemed to have originated directly from her melanoma metastases, with consequent severe hypercalcemia.

FIG. 1.

Photomicrograph showing immunohistochemistry against parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTH-rP) was strongly reactive in the case patient's subcutaneous metastases, using diaminobenzidine as the chromogen. Tumor cells show homogenous immunostaining, suggesting that PTH-rP secretion was non–cell-cycle dependent.

FIG. 2.

Photomicrograph showing immunohistochemistry against PTH-rP was nonreactive in a metastatic melanoma biopsy from a normocalcemic patient.

To determine the incidence of patients with metastatic melanoma with hypercalcemia, we retrospectively evaluated serum calcium levels of 1,146 consecutive patients with metastatic melanoma treated in the Surgery Branch of the National Cancer Institute between January 1, 1988 and March 31, 2000. We found that 56 patients (4.9%) had hypercalcemia (Table 2); the patient discussed herein had the most severe hypercalcemia documented in the series.

TABLE 2.

Frequency of hypercalcemia in 1,146 patients with metastatic melanoma

| Percent of upper limit of normal | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| >150 | 1/1,146 (0.09%) |

| 105–150 | 14/1,146 (1.2%) |

| 100–105 | 41/1,146 (3.6%) |

DISCUSSION

Hypercalcemia is a well-known and documented complication of malignancy. It has typically been attributed to one of two mechanisms: local osteolytic hypercalcemia, associated with metastases to bone; and humoral hypercalcemia, associated with increased bone resorption and decreased renal clearing of calcium, mediated by circulating or humoral factors.13

After the elucidation of PTH-rP in the 1980s, its role has typically been seen in connection with renal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and bladder carcinoma.13 However, few articles have reported on hypercalcemia in melanoma, and even fewer have reported a direct link to PTH-rP in these patients. In the series of 560 patients evaluated by Burt and Brennan,1 5 of the 6 patients with hypercalcemia had metastases to bone, whereas the sixth patient had primary hyperparathyroidism with no evidence of bony disease. The Levy and Feun series2 of 143 patients with metastatic melanoma reported three patients with hypercalcemia. Two of these three patients had significant bony metastases, whereas the third patient showed only minimal bone involvement. In their discussion they comment on “other possible mechanisms such as ectopic hyperparathyroidism” to explain the calcium status of this patient.

After the elucidation of PTH-rP, Yeung and colleagues14 reported a 46-year-old woman with metastatic melanoma and hypercalcemia with increased serum PTH-rP, and no evidence of bony disease. Pleuracentesis of her malignant effusion showed a value of PTH-rP 10 times that of her serum value. Although this was the fourth reported case of PTH-rP in a patient with melanoma, it was the first to provide a convincing link between the peptide and the clinical manifestation of hypercalcemia. More recently, Kageshita et al.3 analyzed serum levels of calcium and PTH-rP in 59 patients with advanced melanoma. Two of the seven patients with hypercalcemia had elevated levels of serum PTH-rP.

This current review is the largest series to date reporting on the incidence of hypercalcemia in patients with melanoma. The production of PTH-rP by this patient's melanoma metastases was demonstrated by immunohistochemistry. Although hypercalcemia is not considered a common complication in patients with advanced melanoma, it did occur in 4.9% of our patients; PTH-rP, even in the absence of bony metastases, may play a significant role in life-threatening hypercalcemia.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burt ME, Brennan MF. Hypercalcemia and malignant melanoma. Case reports. Am J Surg. 1977;137:790–794. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(79)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy I, Feun L. Hypercalcemia and malignant melanoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13:524–526. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199012000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kageshita T, Matsui T, Hirai S, et al. Hypercalcemia in melanoma patients associated with increased levels of parathyroid hormone-related protein. Melanoma Res. 1999;9:69–73. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199902000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mallory TB. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital (case 27461) N Engl J Med. 1941;225:789–791. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berson SA, Yalow RS. Parathyroid hormone in plasma in adenomatous hyperparathyroidism, uremia, and bronchogenic carcinoma. Science. 1966;154:907–909. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3751.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riggs BL, Arnaud CD, Reynolds JC, et al. Immunologic differentiation of primary hyperparathyroidism from hyperparathyroidism due to nonparathyroid cancer. J Clin Invest. 1971;50:2079–2083. doi: 10.1172/JCI106701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell D, Singer FR, Murray TM, et al. Non-parathyroid humoral hypercalcemia in patients with neoplastic diseases. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:176–181. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197307262890403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodan SB, Insogna KL, Vignery AM-C, et al. Factors associated with humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy stimulate adenylate cyclase in osteoblastic cells. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1511–1515. doi: 10.1172/JCI111108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson EL, Munday GR, D'Souza SM, et al. Absence of parathyroid messenger RNA in nonparathyroid tumors associated with hypercalcemia. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:325–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198308113090601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosely JM, Kubota M, Kiefenbach-Jagger H, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein purified from a human lung cancer cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:5048–5052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.5048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burtis WJ, Brady TG, Orloff JJ, et al. Immunological characteristics of circulating parathyroid hormone-related protein in patients with humoral hypercalcemia of cancer. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1106–1112. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004193221603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grill V, Rankin W, Martin TJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein and hypercalcemia. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:222–229. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broadus AE, Mangin M, Ideda K, et al. Humoral hypercalcemia of cancer. Identification of a novel parathyroid hormone-like peptide. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:566–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeung SCJ, Eton O, Burton DW, et al. Hypercalcemia due to parathyroid hormone-related protein secretion by melanoma. Case report. Horm Res. 1988;49:288–291. doi: 10.1159/000023188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]