Abstract

Purpose:

For decades, researchers have proclaimed the positive psychosocial benefits of participation in physical activity. However, recent meta-analyses of the literature have found infrequent and inconclusive empirical support for the link between physical activity and psychosocial well-being. In this study, we use data from a longitudinal study to explore the links between participation in physical activity and global self-esteem among girls from childhood into early adolescence and the direction of this relationship.

Methods:

Participants included 197 non-Hispanic white girls. Girls' participation in physical activity and their global self-esteem were assessed when they were 9, 11, and 13 years old. Panel regression was used to assess the lagged effect of physical activity on self-esteem and the lagged effect of self-esteem on physical activity, controlling for family socioeconomic status (SES) and girls' body mass index (BMI).

Results:

A significant lagged effect of physical activity on self-esteem was identified. Specifically, higher physical activity at ages 9 and 11 years predicted higher self-esteem at ages 11 and 13 years respectively, controlling for covariates. Positive effects of physical activity on self-esteem were most apparent at age 11 and for girls with higher BMI. No support was gained for the lagged effect of self-esteem on physical activity.

Conclusions:

Results suggest that participating in physical activity can lead to positive self-esteem among adolescent girls, particularly for younger girls and those at greatest risk of overweight. These findings highlight the necessity of promoting physical activity among adolescent girls as a method of fostering positive self-worth.

Keywords: Exercise, Children, Girls, Adjustment, Mental health, Psychosocial well-being

The positive effect of physical activity on mental health is a long-held and widely accepted belief among scholars and practitioners alike. Mental health benefits of physical activity may result from increases in social support and a sense of mastery as well as changes in noradrenaline and neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin [1]. Recent reviews of the literature, however, indicate that empirical support for the link between participation in physical activity and psychosocial well-being is infrequent and inconclusive [2-5]. With this in mind, this study assesses the longitudinal association between physical activity and global self-esteem in a sample of adolescent girls, a population at risk for depression and low self-esteem [6-8].

Self-esteem is the focus of this study because it has been identified as a predictor of many other constructs that constitute psychosocial well-being. Higher levels of self-esteem are associated with increased self-efficacy, body image, and leadership, and reduced levels of depression and anxiety [5,9]. As outlined in recent reviews [2,5,10], few studies have examined the link between physical activity and self-esteem among adolescent girls, and no studies have tested the direction of this association. Given the low rates of physical activity participation in this population [11], these are important questions to address. The lack of detailed information on the relationship between physical activity and psychosocial well-being impedes the development of effective intervention programs. More specifically, it is not clear whether increasing self-esteem may lead to higher physical activity among girls or whether increasing physical activity may lead to higher self-esteem. Both are worthy efforts to pursue, but conclusive evidence of an association between physical activity and self-esteem and the direction of this effect will ensure more effective use of limited intervention resources.

Although research on the association between physical activity and self-esteem with adolescent samples is limited, a small number of longitudinal studies assessing the effects of physical activity on self-esteem have been conducted with older adult populations [12]. Based on data from adults aged 60 years and older, McAuley et al [12] contended that there is a direct link between participation in physical activity and increased self-esteem over time. Specifically, McAuley et al found that physical activity had a positive effect on physical self-worth and global self-esteem over a 4-year period. These data provide further justification for assessing longitudinal associations between physical activity and self-esteem in other age groups such as adolescent girls.

This study examines the temporal ordering of the association between physical activity and global self-esteem using a longitudinal sample of girls assessed at ages 9, 11, and 13 years. Specifically, using an individual growth model, the lagged effect of physical activity on self-esteem and the lagged effect of self-esteem on physical activity are examined while taking factors such as parents' socioeconomic status (SES) and girls' age and body mass index (BMI) into consideration. Using this technique, we were able to assess the direction of the relationship between physical activity and self-esteem and whether effects were modified by girls' age, BMI, or pubertal status.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 197 non-Hispanic white girls who were part of a 10-year longitudinal study examining girls' nutrition, dieting, physical activity, and health. Girls were assessed at ages 9, 11, and 13 years. A convenience sampling method was used. Participants were recruited for the longitudinal study using flyers and newspaper advertisements. In addition, families with age-eligible female children within a five-county radius received mailings and follow-up phone calls. Girls were not recruited based on pre-existing physical activity behaviors or self-esteem. The Institutional Review Board of the associated university approved all study procedures. Written consent from parents (for their daughters) and written assent from girls were obtained before girls' completion of the study protocol.

Participating girls visited an on-campus laboratory at ages 9, 11, and 13 for data collection. Trained interviewers collected data on girls' participation in physical activity, self-esteem, BMI, pubertal status, and SES at each age using the measures described below. Sample attrition and item missingness was minimal, resulting in a study sample of 166 respondents with full information at age 11 and 161 at age 13 years. We use listwise deletion in response to missing data because Allison [13] has demonstrated the superior inferential properties of this approach to missingness relative to common imputation alternatives.

Measures

Physical activity

Three measures of girls' physical activity were obtained including general inclination toward activity, participation in organized sports, and physical fitness. The Children's Physical Activity (CPA) scale was used to assess girls' general tendency or inclination toward activity [14]. The CPA contains 15 items and uses a four-point response scale ranging from 1 (“completely true”) to 4 (“completely false”). The CPA addresses physical activity preferences with items such as “I would rather watch TV or play in the house than play outside.” Research supports that validity of this scale: Scores on the CPA were found to be significantly related to 1-mile run/walk time (r = −.43, p < .0001), body fat percentage (r = −.41, p < .0001), and BMI (r = −.32, p < .0001) [14]. The internal consistency coefficient of the CPA in this study was α = .67 at age 9, α = .73 at age 11, and α = .77 at age 13 years.

Participation in team sports and organized activities was assessed using the activity checklist. Participants were presented with a list of 24 activities (e.g., rollerblading, soccer, cheerleading) and asked to indicate whether they participated in each activity at an organized level (i.e., participated on a team or took lessons). The total number of activities selected was summed to reflect the total number of sports and organized activities in which girls participated. Although there are no validity data available for the activity checklist, activities included on the checklist are consistent with preferred activities as reported by youth living in rural areas. Youth in rural areas have different interests and opportunities than youth living in urban or metropolitan areas. It was therefore important that the measure appropriately reflect the needs and interest of this group. The most preferred activities among rural youth, as identified by Savage and Scott [15] include tennis, volleyball, swimming, softball, bicycling, football, ice skating, backpacking and hiking, and weightlifting. All of these activities were included on the activity checklist.

Girls' physical fitness, an indirect measure of physical activity, was measured using the Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run (PACER) [16,17]. This is a progressive test providing an index of aerobic fitness that is suitable for children of all ages. Children run back and forth between markers spaced 20 meters apart at a specified pace that progressively increases. Greater numbers of “laps” completed and the ability to maintain the specified pace indicate a higher level of aerobic capacity and in turn a higher level of fitness. Previous research illustrates the test–retest reliability of the PACER, and has shown that the number of laps completed is significantly and positively correlated with measured VO2Max (r = .69 boys and r = .51 for girls) [18].

Physical activity is a multidimensional construct [19]. Consequently, a summary physical activity score based on multiple measures of physical activity is more representative of general activity patterns than are individual measures [20]. A summary physical activity score was created using the three measures of physical activity at each age. Specifically, principal component analysis was used to combine scores on each measure to form a single score using weights (or factor loadings) reflecting the intercorrelations between the measures. The resulting summary score (a z-score with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1) was correlated with each individual measure of physical activity at each age with correlations ranging between r = .57 and r = .79, p < .0001. In addition to being a more reliable and valid measure of general levels of physical activity, the use of a summary physical activity score substantially reduced the number of analyses performed and simplified the presentation and discussion of results.

Global self-esteem

Global self-esteem was measured using the Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPP) [21]. Girls responded to six-items (e.g., “I like the kind of person I am”) using a four-point response scale ranging from 1 (“really disagree”) to 4 (“really agree”). Scores were averaged to create a total self-esteem score ranging from low (1) to high (4) self-esteem. Previous research supports the reliability and validity of the SP [22]. In the current study, the internal consistency coefficient for global self-esteem was α = .78 at age 9 and α = .82 at ages 11 and 13 years.

Demographic covariates

Pubertal development, BMI, and SES were examined as potential covariates. Breast development was used as a marker for pubertal development. Girls' breast development was assessed at each age using Tanner's criteria for pubertal breast stage [23]. Stages range from 1 (no development) to 5 (mature development). Visual inspection of each breast was made unobtrusively by a trained nurse and a nurse's assistant while using a stethoscope to check heart rate. In addition, research assistants recorded girls' height and weight three times. The average of the three measurements were used to calculate BMI (weight [kg]/height —2). Scores were converted to age and sex-specific BMI z-scores [24]. Finally, parents provided information on family income and their years of education as part of a standard demographic questionnaire used for the larger longitudinal study. These data (family income, mother's education, father's education) were combined using principal component analysis to provide a single measure of SES.

Statistical analyses

We used an individual growth model [25-28] to examine (a) the lagged effect of physical activity on self-esteem and (b) the lagged effect of self-esteem on physical activity. We chose this analytical method because it makes full use of the data from all three time points, it models the within person correlation across time, and it assesses the two lagged activity effects (9–11 and 11–13) simultaneously, thereby decreasing the likelihood of a type I error, increasing the number of data points from 166 (when modeling self-esteem at age 11) or 161 (when modeling self-esteem at age 13) to 327, and increasing the statistical power. In each model, the outcome variable at ages 11 and 13 years was regressed onto activity at ages 9 and 11. Covariates including age, BMI z-score (as a time varying covariate), pubertal status, and SES, measured at ages 11 and 13 years, and first-order interactions among the covariates, were added to each model. No significant effects were found for pubertal status or for interactions between age, BMI, and SES, and these terms did not improve model fit. As a result, these variables were excluded from the final analyses.

Using the lagged effect of physical activity on self-esteem as an example, the final model was specified as follows: Yij, the self-esteem score for the jth respondent at time i, was regressed onto (a) respondent's age at time i (Aij), (b) lagged activity (ACTi-1,j), so that the activity component score of the jth respondent at age 9 affects Yj at age 11 and the activity score at age 11 affects self-esteem at age 13, (c) SES at age 9 (SESj), and (d) BMI (BMIij), and (e) interaction terms between age and lagged activity, and BMI and lagged activity.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Girls were generally from middle- to upper-income, well-educated families. The median family income when girls were 11 years old was between $51,000 and $75,000. Mothers and fathers reported an average of 14.8 (SD = 2.3) and 14.9 (SD = 2.6) years of education respectively. At age 9 years, 31% of girls had a BMI greater than or equal to the 85th percentile. This figure was 29% at age 11 and 26% at age 13 years.

As shown in Table 1, participants generally reported relatively high levels of self-esteem. The mean self-esteem score was approximately 3.5 at each age on a scale of 1 (low self-esteem) to 4 (high self-esteem). The scale range, however, indicates that some girls reported scores as low as 1.5. Although there was some evidence of self-esteem scores varying for girls who were overweight (BMI percentile ≥85) versus nonoverweight (BMI percentile <85), the lowest mean score was 3.26, indicating the absence of a floor effect of self-esteem for high BMI girls (data not shown). Girls reported moderate levels of physical activity on the CPA with mean scores ranging between 2.79 and 2.95 on a four-point scale. In addition, girls on average reported participating in two organized activities at each age with a range of 0–11 activities. Finally, girls' fitness scores increased across ages 9–13 years.

Table 1.

Mean (and SD) self-esteem, physical activity, and body mass index (BMI) z-score at ages 9, 11, and 13 years

| Measure | Min–Max | Age |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 11 | 13 | ||

| Self-esteem | 1.5–4 | 3.43 (.52) | 3.51 (.47) | 3.53 (.48) |

| Physical activity | ||||

| CPA scale score | 1.42–3.93 | 2.85 (.38) | 2.95 (.35) | 2.79 (.40) |

| Sport participation | 0–11 | 2.33 (1.31) | 2.47 (1.53) | 2.73 (1.97) |

| Fitness (no. of shuttle run laps) | 3–54 | 16.13 (6.48) | 18.02 (8.08) | 22.87 (10.73) |

| BMI z-score | −.2.05–2.82 | .52 (.95) | .49 (.96) | .45 (.92) |

CPA = Children's Physical Activity.

Testing the direction of the association between physical activity and self-esteem

Results from the individual growth model predicting physical activity provided no support for a lagged effect of self-esteem on physical activity. That is, higher self-esteem at ages 9 and 11 years was not associated with higher physical activity at ages 11 and 13 respectively (data not shown). In contrast, there was evidence for a lagged effect of physical activity on self-esteem (Table 2). The model explained approximately 13% of the variation in the linear trajectory of self-esteem. There was also consistent evidence of within-person residual autocorrelation between the two panels (ages 11 and 13), which was corrected for. The average within-person residual correlation (ρ) for self-esteem was approximately r = .2 (p < .014). Although the lagged effect of physical activity is statistically significant in Table 2, this effect is not directly interpretable because it is only in reference to 11-year-old girls with a mean BMI, and the lagged effect of activity was conditional on age and BMI, as shown by the significant interactions.

Table 2.

Results from the panel regression model predicting the lagged effect of physical activity on girls' self-esteem, controlling for covariates

| Covariates | Nonstandardized regression coefficient (SE) |

|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.53 (.04)* |

| Age | .01 (.02) |

| Activity (lagged) | .06 (.04)* |

| SES at age 9 years | .04 (.03) |

| BMI | −.09 (.03)* |

| Age * Activity (lagged) | −.05 (.02)* |

| BMI * Activity (lagged) | .07 (.03)* |

SES = principal component of family income and parent education.

t-Ratio significant at p < .05 (two-tailed test).

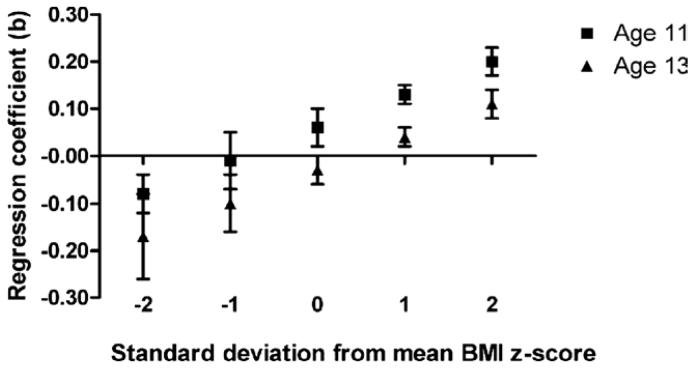

To interpret the lagged effect of physical activity on self-esteem, results need to be assessed at varying ages and BMI z-scores as shown in Table 3. Table 3 reveals two patterns. First, the effect of physical activity on self-esteem is stronger at age 11 years than at age 13. That is, the effect of physical activity age at 9 on self-esteem at age 11 is stronger than the effect of physical activity at age 11 on self-esteem at age 13. Second, the positive effect of physical activity on self-esteem increases as BMI increases. This effect is illustrated more clearly in Figure 1. More specifically, at one standard deviation above the mean BMI z-score, a one-unit increase in activity at age 9 increases self-esteem at age 11 by .13 point, whereas a one-unit increase in activity at age 11 exerts about one-third that magnitude (.04) on self-esteem at age 13 years. At two standard deviations above the mean BMI, a one-unit increase in activity at age 9 increases self-esteem at age 11 by .20 point; whereas a one-unit increase in activity at age 11 years yields a .11-point increase in self-esteem at age 13. The reverse pattern is noted for girls with a BMI z- score below the mean. This effect, however, was only noted at age 13. For these girls, a one standard deviation increase in physical activity at age 11 is associated with a .10–.17-unit decrease in self-esteem at age 13 years.

Table 3.

Effect of (lagged) physical activity on self-esteem conditional on age and body mass index (BMI) z-score

| Unstandardized regression coefficient (SE) | |

|---|---|

| Age 11 years | |

| BMI score | |

| Mean − 2 SD | −.08 (.09) |

| Mean −1 SD | −.01 (.06) |

| Mean | .06 (.04)* |

| Mean + 1 SD | .13 (.02)** |

| Mean + 2 SD | .20 (.03)** |

| Age 13 years | |

| BMI score | |

| Mean − 2 SD | −.17 (.09)* |

| Mean − 1 SD | −.10 (.06)* |

| Mean | −.03 (.03) |

| Mean + 1 SD | .04 (.02)** |

| Mean + 2 SD | .11 (.03)** |

t-Test significant at p < .10 (two-tailed test).

t-Test significant at p < .05 (two-tailed test).

Figure 1.

Regression coefficients for the lagged effect of physical activity on self-esteem conditional on age and BMI z-score (−2 to 2 standard deviations from the mean).

Discussion

For decades, physical activity has been purported to have positive effects on psychosocial well-being. Such benefits may be particularly important for girls during their adolescent years, as they are susceptible to low self-esteem and have high physical activity attrition rates [6-8,11]. Yet few longitudinal studies have assessed the association or the directionality of the relationship between physical activity and psychosocial well-being, particularly self-esteem, in an adolescent population. Using individual growth models, we investigated the lagged effect of physical activity on self-esteem and the lagged effect of self-esteem on physical activity among girls aged 9–13 years. No support was found for the lagged effect of self-esteem on physical activity. In contrast, higher participation in physical activity at ages 9 and 11 years predicted higher self-esteem at ages 11 and 13 years, respectively, illustrating a lagged effect of physical activity on self-esteem. These effects, however, differed by age and BMI, suggesting stronger effects at younger ages for girls who were more overweight. Results from this longitudinal study provide more definitive evidence than previous cross-sectional research of the psychosocial benefits of physical activity [12,29,30] and concur with findings based on older populations [12].

The lagged effect of physical activity on girls' self-esteem was modified by age. The effect of physical activity at age 9 on self-esteem at age 11 years was stronger than the effect of physical activity at age 11 on self-esteem at age 13. It is possible that this result is caused by social expectations of gender behavior, developmental differences in adherence to these expectations among youth, and the confusing messages that girls receive regarding the role of women in society. Previous research has suggested that, as children, boys and girls are afforded latitude to pursue activities and behaviors regardless of social expectations of gender, without risk of stigma [30]. As a result, younger girls may readily experience the positive psychosocial effects of participation in physical activity. However, as children approach adolescence, they become more rigid in their perceptions of gender and latitudes of behavior [30]. For adolescent girls, this means a decrease in traditionally masculine activities, such as participation in physical activity. According to social ideals of gender, participation in physical activity is contrary to what adolescent girls may perceive they should do as they develop into young women (i.e., the notion that participation in physical activity un-feminine) [31-33]. In this social context, adolescent girls who are physically active are operating in opposition to what is expected of them, thereby decreasing the likelihood that they will experience the psychosocial benefits of physical activity. These suggestions are purely speculative, however, and warrant further investigation.

BMI also modified the effect of physical activity on self-esteem. At ages 11 and 13, the positive effect of physical activity on self-esteem was more apparent for girls with above-average BMI than for girls with average BMI. It is interesting to consider the potential reasons why the positive effects of physical activity on self-esteem are disproportionately experienced by girls with a higher than average BMI. Given that all girls reported relatively high self-esteem in this sample regardless of weight status, effects of physical activity on self-esteem for girls with high BMI cannot be explained by particularly low levels of self-esteem in this group. It is possible that girls with above-average BMI scores may garner the benefits of participation in physical activity more tangibly in that they are apt to lose weight, whether intended or not, as a result of being active than their average and below-average BMI colleagues. It is also possible that participation in physical activity is linked with greater increases in self-efficacy and perceived competence, and in turn self-esteem, among girls with a high BMI in comparison to girls with a lower BMI. Similarly, girls with high BMI may experience a greater increase in peer connectedness than their leaner colleagues as a result of being physically active. As with possible explanations for the moderating effect of age, these suggestions were not examined in the current study and are possible questions for future research.

In contrast to effects noted for girls with above-average BMI, physical activity was associated with lower self-esteem among girls with below-average BMI. This effect was noted at age 13 years only. Of note in this instance, however, are the large standard deviations around values for low BMI as shown in Figure 1. This result is counterintuitive but may reflect concerns regarding physical appearance and weight that are common among girls as they enter puberty [34]. Previous researchers have contended that there is a negative relationship between participation in physical activity and psychosocial well-being if participation is sought for weight loss or body image purposes [35,36]. In this sample of white middle-class girls, it is possible that girls with below-average BMI were physically active for extrinsically motivated reasons such as body image or weight loss. However, this suggestion is speculative and was not tested in the current study.

The key strengths of this study include the use of a longitudinal design and the public health implications of the findings. With three points of measurement, we were able to examine the direction of the association between physical activity and self-esteem among adolescent girls. To our knowledge, this is the first study to clarify the directionality of these effects in a population that is at risk for low self-esteem and low physical activity. Findings from this study provide further justification for promoting physical activity among adolescent girls. In addition to the well-documented physical health benefits of an active lifestyle, this study suggests that higher physical activity among adolescent girls of white ethnicity promotes positive self-esteem.

There are also a number of limitations of this study. First, findings are only applicable to white girls from middle- to upper-income families. Given racial and ethnic differences in self-esteem and body image [37-39], as well as pressure from family and friends to lose weight or participate in physical activity [40], it is likely that the mental health benefits of physical activity differ across races and ethnicities. Second, we did not have access to an objective (and direct) measure of physical activity, such as accelerometers, at all times of assessment. As a result, physical activity was assessed using a combination of self-report measures, with limited reliability and validity, and physical fitness, an indirect measure of physical activity. We used an aggregate score of physical activity based on all measures of physical activity as a means of reducing concerns in this regard. Finally, girls in general reported high levels of self-esteem. A ceiling effect of self-esteem would decrease the ability to identify a positive association between physical activity and self-esteem. As a result, findings from this study may underestimate the benefits of physical activity on self-esteem in the general population of adolescent girls.

In conclusion, this study was designed to clarify the directionality of the relationship between physical activity and self-esteem in a sample of adolescent girls. Findings suggest that physical activity promotes positive self-esteem among girls, particularly among pre-adolescent girls (i.e., at age 11 years) and girls with higher BMI. Future research can build on results from this study by assessing similar associations in a more diverse sample of adolescents and with other measures of mental health and by using objective and direct measures of physical activity. Additional research could also expand on this study by assessing psychosocial (e.g., activity motivation, body esteem, social norms, self-efficacy, weight loss) and physiologic (e.g., noradrenaline, serotonin) pathways linking physical activity and self-esteem among adolescent girls.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants HD 46567 (to K.K.D.) and HD 32973 (to L.L.B).

References

- 1.Paluska SA, Schwenk TL. Physical activity and mental health: Current concepts. Sports Med. 2000;29:167–80. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200029030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biddle SJH, Whitehead SH, O'Donovan TM, Nevill ME. Correlates of participation in physical activity for adolescent girls: A systematic review of recent literature. J Phys Act Health. 2005;2:423–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin RD. Association between physical activity and mental disorders among adults in the United States. Prev Med. 2003;36:698–703. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sallis J, Prochaska J, Taylor W. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:963–975. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strong WB, Malina RM, Bumkie CJR, et al. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. J Pediatr. 2005;146:732–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kling KC, Hyde JS, Showers CJ, et al. Gender differences in self-esteem: A meta analysis. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:470–500. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knox M, Funk J, Elliott R, Bush EG. Adolescents' possible selves and their relationship to global self-esteem. Sex Roles. 1998;39:61–80. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strauss RS, Rodzilsky D, Burack G, et al. Psychosocial correlates of physical activity in healthy children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:897–902. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.8.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Robins RW. Stability of self-esteem across the life span. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:205–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkcaldy BD, Shepard RJ, Siefen RG. The relationship between physical activity and self-image and problem behaviour among adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:544–50. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunbaum J, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States 2003. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;53:1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAuley E, Elavsky S, Motl RW, et al. Physical activity, self-efficacy, and self-esteem: Longitudinal relationships in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:268–75. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.5.p268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allison PD. Multiple imputation for missing data: A cautionary tale. Sociol Meth Res. 2000;28:301–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tucker LA, Seljaas GT, Hager RL. Body fat percentage of children varies according to their diet composition. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97:981–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00237-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savage M, Scott L. Physical activity and rural middle school adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 1998;27:245–53. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leger LA, Lambert J. A multistage 20-m shuttle run test to predict VO2max. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1982;49:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00428958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leger LA, Mercier D, Gadoury C, et al. The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J Sports Sci. 1988;6:93–101. doi: 10.1080/02640418808729800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu N, Plowman S, Looney M. The reliability and validity of the 20-meter shuttle test in American students 12–15 years old. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1992;63:360–5. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1992.10608757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood T. Issues and future directions in assessing physical activity: An introduction to the conference proceedings. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71:757–65. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2000.11082779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kishton J, Widaman K. Unidemensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: an empirical example. Educ Psychol Meas. 1994;54:757–65. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harter S. Manual for the Self Perception Profile for Children: Revision of the Perceived Self Competence Scale for Children. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schumann B, Striegel-Moore R, McMahon R, et al. Psychometric properties of the Self-Perception Profile for Children in a biracial cohort of adolescent girls: The NHLBI Growth and Health Study. J Pers Assess. 1999;73:260–75. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7302_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuczmarski R, Ogden C, Grummer-Strawn L, et al. CDC Growth charts: United States. Advance data from vital and health statistics. Vol. 28. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2000. publication 314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryk AS, Stephen WR. Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psychol Bull. 1987;101:147–58. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Assessing longitudinal change in marriage: An introduction to the analysis of growth curves. J Marriage Fam. 1995;57:1091–1108. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willett JB, Singer JD, Martin NC. The design and analysis of longitudinal studies of development and psychopathology in context: Statistical models and methodological recommendations. Dev Psychopathol. 1998;10:395–426. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larson RW. Toward a psychology of positive youth development. Am Psychol. 2000;55:170–83. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liben LS, Bigler RS. The Developmental Course of Gender Differentiation. Blackwell Publishing; Boston, MA: 2002. (Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, No. 67). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vilhjalmsson R, Kristjansdottir G. Gender differences in physical activity in older children and adolescents: The central role of organized sport. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:363–74. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett AE, White HR. Trajectories of gender role orientation in adolescence and early adulthood: A prospective study of the mental health effects of masculinity and femininity. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:451–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heywood L, Dworkin SL. Built to Win: The Female Athlete as Cultural Icon. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis, MN: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davison KK, Werder JL, Trost SG, et al. Why are early maturing girls less active? Links between pubertal development, psychosocial well-being and physical activity among girls at ages 11 and 13. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:2391–2404. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galambos NL, Leadbeater BJ, Barker ET. Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. Int J Beh Dev. 2004;28:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA, Banfield S. Body image, strategies to change muscles and weight, and puberty: Do they impact on positive and negative affect among adolescent boys and girls? Eat Behav. 2001;2:129–49. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(01)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Story M, French SA, Resnick MD, et al. Ethnic/racial and socioeconomic differences in dieting behaviors and body image perceptions in adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;18:173–9. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199509)18:2<173::aid-eat2260180210>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paxton RJ, Valois RF, Drane JW. Correlates of body mass index, weight goals, and weight-management practices among adolescents. J Sch Health. 2004;74:136–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biro FM, Streigel-Moore RH, Franko DL, et al. Self-esteem in adolescent females. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:501–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams K, Sargent RG, Thompson SH, et al. A study of body weight concerns and weight control practices of 4th and 7th grade adolescents. Ethn Health. 2000;5:79–94. doi: 10.1080/13557850050007374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]