Abstract

Two experiments investigated list-method directed forgetting with older and younger adults. Using standard directed forgetting instructions, significant forgetting was obtained with younger but not older adults. However, in Experiment 1 older adults showed forgetting with an experimenter-provided strategy that induced a mental context change -- specifically, engaging in diversionary thought. Experiment 2 showed that age related differences in directed forgetting occurred because older adults were less likely than younger adults to initiate a strategy to attempt to forget. When the instructions were revised to downplay their concerns about memory, older adults engaged in effective forgetting strategies and showed significant directed forgetting comparable in magnitude to younger adults. The results highlight the importance of strategic processes in directed forgetting.

Keywords: Directed forgetting, strategy use, context change, executive control

This paper is about age-related differences in intentional forgetting of unwanted information. Imagine receiving medication and reading the directions on how to take it. Afterwards, the doctor tells you to take a different dosage at a different time from that printed on the label. Updating the directions may necessitate intentional forgetting of the earlier-learned information. The current paper took one approach to examining this issue by examining age differences in the effectiveness of intentional forgetting using the popular list-method directed forgetting procedure invented by Bjork, LaBerge, and LeGrand (1968).

In directed forgetting, participants study some information for a later memory test and are subsequently instructed to forget certain portions of it (for reviews, see Bjork, Bjork, & Anderson, 1998; Johnson, 1994; MacLeod, 1998). In the list method, the instruction occurs after an entire block of items has been presented. There is also an item method of directed forgetting that delivers forget instructions on an item-by-item basis, and there is broad agreement that the item method reflects differential encoding of to-be-remembered (TBR) and to-be-forgotten (TBF) items (e.g., Basden, Basden, & Gargano, 1993). In contrast, list method directed forgetting somehow reduces access to TBF items at test (Bjork, 1989; Bjork & Bjork, 1996; 2003; but see Benjamin, 2006; Sheard & MacLeod, 2005), and several retrieval-based mechanisms have been proposed. For example, we argued that list-method directed forgetting arises from the mismatch of study and test contexts (e.g., Sahakyan & Kelley, 2002); others argued for an inhibitory explanation (e.g., Bjork, 1989). Given that older adults’ memory deficits have been attributed in part to impaired inhibitory abilities (e.g., Hasher & Zacks, 1988) or to associative memory deficits, including difficulties in binding events to their context (e.g., Chalfonte & Johnson, 1996; Johnson, 1997; Naveh-Benjamin, 2000), the current studies set out to investigate older and younger adults’ memory using list-method directed forgetting.

A typical list-method directed forgetting design involves studying two lists of items for a later memory test. After List 1, they are interrupted and told to forget that list (“because it was only for practice”) or to keep remembering it (“that was only the first half of the items”). Next, List 2 is studied, followed by a memory test for both lists. The most robust outcome is impaired recall of List 1 in the forget group compared to the remember group – known as the costs of directed forgetting. The recall impairment in the forget group is sometimes accompanied by enhanced recall of List 2 -- known as the benefits of directed forgetting. However, directed forgetting benefits are less reliable and robust than the costs (e.g., MacLeod, 1988), and they are not always observed together. Absence of the benefits has previously been linked to semantic relationships between lists (e.g., Sahakyan & Goodmon, 2007) and to encoding strategies (e.g., Sahakyan & Delaney, 2003, 2005).

The costs of directed forgetting have attracted greater interest and attention than the benefits, presumably because of the possible link to suppression phenomena. Because directed forgetting costs are obtained in incidental learning (e.g., Geiselman, Bjork, & Fishman, 1983; Sahakyan & Delaney, 2005; Sahakyan, Delaney, & Waldum, in press), some researchers propose that directed forgetting is due to inhibition at the time of retrieval (e.g., Bjork, 1989; Bjork & Bjork, 1996; 2003; Geiselman et al., 1983). For example, Bjork (1989) argued that instructions to forget initiate a process that at the time of retrieval blocks or inhibits access to List 1 items, producing directed forgetting costs. As List 1 items become inhibited, they reduce proactive interference on List 2 items, producing the benefits of directed forgetting. Retrieval inhibition is a single-process account because it explains both costs and benefits via a single underlying process, and therefore assumes that both outcomes should be observed together -- especially when there is room to escape from proactive interference (that is, proactive interference should be significant in the remember group so that the forget group can escape it).

Alternatively, my colleagues and I have proposed a two-factor account suggesting that directed forgetting arises from a combination of factors including (a) changes in mental context and (b) encoding strategy changes (Sahakyan & Delaney, 2005). We argued that in response to the directed forgetting instruction, participants adopt a forgetting strategy – such as engaging in a diversionary thought – that changes the mental context in which List 2 is encoded (Sahakyan & Kelley, 2002; Sahakyan, 2004). Because memory is tested after List 2, the test context matches the List 2 context better than it matches the List 1 context, leading to forgetting of List 1 items. Thus, the costs of directed forgetting arise from impaired access to List 1 items owing to a change of mental context. The second factor explains the benefits of directed forgetting and proposes that the directed forgetting instruction interrupts ongoing processing and enables people to reflect on their memory performance so far, triggering a change to better encoding strategies on subsequent lists (Sahakyan, Delaney & Kelley, 2004; Sahakyan & Delaney, 2003, 2005). The benefits emerge because the remember instruction is less likely than the forget instruction to induce strategy changes. In support of the strategy change account of the benefits, preventing strategy change or mandating a single strategy on both lists eliminated the benefits of directed forgetting (despite significant build-up of proactive interference), but left the costs intact (Sahakyan & Delaney, 2003). Furthermore, whereas the costs are obtained in incidental learning, the benefits are not, presumably because incidental learning instructions are less likely to prompt evaluation and change of study strategy (Sahakyan & Delaney, 2007, Sahakyan et al., in press). To summarize, the two-factor account was proposed because the costs and the benefits of directed forgetting were not always observed together and were dissociated by experimental manipulations (see also Sahakyan & Goodmon, 2007).

To date, three studies have examined older adults’ ability to perform the list-method directed forgetting task. Using the traditional design, both Zellner and Bäuml (2006) and Sego, Golding, and Gottlob (2006) obtained significant directed forgetting with older adults, whereas Zacks, Radvansky and Hasher (1996) reported non-significant directed forgetting using a partial design (only the forget group) and some variations on the usual procedure. Although Zacks et al. (1996) interpreted their non-significant directed forgetting findings to be consistent with the impaired inhibitory view of aging, later studies obtained significant directed forgetting, implying that either retrieval inhibition is spared in older adults (see also Aslan, Bäuml, & Pastötter, 2007), or that directed forgetting does not rely exclusively on inhibition.

If directed forgetting impairment arises as a result of changes in mental context, then according to the context hypothesis, older adults should show forgetting following a disruption of mental context as found with younger adults. Prior research from our lab demonstrated that when younger participants engage in a diversionary thought pre-specified by the experimenter between the two lists (further termed the context-change condition), they demonstrate directed forgetting-like results (Sahakyan & Kelley, 2002). Furthermore, when at the time of test participants mentally reinstate the initial study context, both the directed forgetting costs and the forgetting due to disruption of mental context are significantly reduced. In studies with younger adults, the results in the context-change condition have resembled the results in the directed forgetting condition across variations in the encoding strategy (Sahakyan & Delaney, 2003) and working memory capacity (Delaney & Sahakyan, 2007). Recently, Pastötter and Bäuml (2007) demonstrated one more parallel between these conditions by showing that a boundary condition for directed forgetting -- the need for the second list learning -- also serves as a boundary condition for the context-change condition. Thus, based on previous research, we predicted impaired recall in older adults following a change in their mental context. Failure to obtain such results would be inconsistent with the context account of directed forgetting.

However, there were reasons to suspect that older adults may be less sensitive to changes of context than younger adults, and may not show impaired recall in the context-change condition despite showing significant directed forgetting. Some researchers argued that older adults have difficulty binding different components of information into a coherent, distinctive unit, leading to more impoverished and fragmented episodic representations (e.g., Chalfonte & Johnson, 1996; Naveh-Benjamin, 2000). The different attributes of information that are encoded as part of an episode include semantic meaning of an item, its relationship to other items, information about the temporal-spatial-mental context – that is, the time/place of an event, as well as the internal cognitive state of the participant (e.g., Anderson & Bower, 1973; Gillund & Shiffrin, 1984; Humphreys, 1976; Johnson & Chalfonte, 1994; Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993; Schacter, Norman, & Koustaal, 1998). Research documents significant age-related declines in the ability to recall contextual information, such as the speaker, the location, or the timing of the information (for a meta-analysis, see Spencer & Raz, 1995). If older adults poorly integrate list items with their contextual attributes, then the contextual cues might become less efficient cues at retrieval. This means that when memory is tested in a context that is different from the encoding context, older adults ironically might be more resilient to changes of context and their recall might not show the impairment characteristically observed with younger adults.

In this paper, we tested older and younger adults using both the standard directed forgetting instruction and the manipulation intended to change mental context by engaging participants in a diversionary thought between the two study lists. To preview, the results revealed surprising dissociations between these conditions; inducing a change in mental context led to significant forgetting in both younger and older participants, whereas directed forgetting instructions produced significant forgetting only in younger adults. In other words, we obtained forgetting by altering older adults’ mental context, but failed to replicate the findings of intact directed forgetting in this age group reported by Zellner and Bäuml (2006) and Sego et al. (2006). The findings of Zellner and Bäuml (2006) and Sego et al. (2006) appeared after we completed the first experiment, and the divergence between our results motivated us to further explore the reasons for our non-significant directed forgetting costs with older adults.

Experiment 1

Methods

Participants

The 96 young adult participants (ages 18 to 32) were recruited through the University of Florida and the University of North Carolina-Greensboro undergraduate participant pool and participated for course credit. The 96 older adult participants (ages 65 to 85) were volunteers recruited through assisted living facilities in the Tampa region as well as community-dwelling volunteers obtained via newspaper ads and mailing lists of the city of Sun City Center, which is a retirement city in Florida. Participants filled out a demographic/health questionnaire reporting their age, education level, overall health (on a scale from 1 to 7, with higher numbers indicating better health), and whether or not they had experienced stroke, dementia, head injury, depression, took psychotropic medication, or had other medical concerns that might affect their memory. None of the participants in the final sample of 96 participants for both age groups had experienced medical conditions or were taking medications that could affect their memory abilities. The younger participants’ mean age was 20.0 (SD = 3.1), whereas the older participants’ mean age was 76.9 (SD = 4.5). Approximately 66% of the younger participants and 70% of the older participants were women.

Older adults had more years of education (M = 15.3, SD = 2.7) than the younger adults (M = 14.0, SD = 1.1), t(190) = 4.52, p < .001. Their Shipley vocabulary score was significantly higher (M = 35.8, SD = 2.9) than that of younger adults (M = 30.2, SD = 4.0), t(169) = 10.31, p < .001. However, no significant differences were found in the total number of correctly generated words on the verbal fluency task between older adults (M = 52.2, SD = 14.5) and younger adults (M = 50.8, SD = 12.7), t <1. The latter was determined following the standard practice of calculating the sum of all produced words, excluding errors and repetitions.

Materials

Two lists of 12 action phrases were created that described health-relevant actions such as take an aspirin and donate blood. Action phrases were chosen because they typically result in higher recall rates both for older and younger adults compared to isolated words (Earles, 1996). The complete list of action phrases is available in Appendix A. Each list served equally often as List 1 and List 2.

Procedure and Design

Participants first filled out the demographic/health questionnaire. Then they completed the FAS task, which is a test of verbal fluency (e.g., Borkowski, Benton, & Spreen, 1967). Specifically, participants were given the letters F, A, and S, and asked to generate as many words as possible in 60 s that began with each letter, excluding proper names and repetitions of the same word with different endings. Upon completion, participants proceeded to the list-method directed forgetting task. They were told that they would be presented some action phrases on the computer screen, and that they should read them aloud and attempt to remember as many as possible for a later test. Twelve action phrases were then presented one at a time on the computer screen, at a rate of six seconds per phrase. Following the first list, one third of the participants in each age group were told to forget that list (further termed the forget condition). Specifically, they were told:

The list of phrases you just saw was for practice, to familiarize you with the task and make you comfortable with the length of the list and the amount of time you have to study each phrase. There is no need to remember these items; just try to forget them. …Now I am about to show you the real study list. Please read each phrase out loud and try to remember as many as you can.

The remaining participants were told to remember that list because “it was only the first half of the study items”. However, before proceeding to study the second list, half of the participants receiving remember instruction were instructed to visualize their childhood home and describe it to the experimenter for 60 s (following Sahakyan & Kelley, 2002). This task was intended to change participants’ mental context and is further termed the context-change condition. Specifically, participants were told:

The list of phrases you just saw was only the first half of the study items. You need to remember them for a later test. Before I show you the second half of the list, I need you to do another task for me. Please close your eyes for a second and try to picture your childhood home. If you see it clearly you may open your eyes. Now describe to me your childhood home from the moment you enter through the front door. Tell me what you would see if you walked through every room, including the details about the furniture and their location. Mentally walk through the house and describe everything you see in it. Meanwhile, I will try to use your description and draw the layout on paper.

To prevent rehearsal, all remaining participants receiving remember instruction as well as the forget group participants were preoccupied with a counting task for the same interval that involved counting forward by two’s from a pre-specified two-digit number. Following the second list, all participants engaged in a distracter task for 60 s that involved more counting forward by two’s from a different pre-specified number. All counting tasks were performed aloud so that the experimenter could monitor compliance with instructions. Finally, participants were asked to recall List 1, followed by List 2 on separate sheets of paper, with 90 s allotted for recall of each list. Afterwards, they completed the Shipley vocabulary test (Zachary, 1991). Thus, the design of the study was a 2 (Age Group: young vs. old) by 3 (Cue: forget, remember, or context-change) between-subjects factorial.

Results

Directed Forgetting Costs

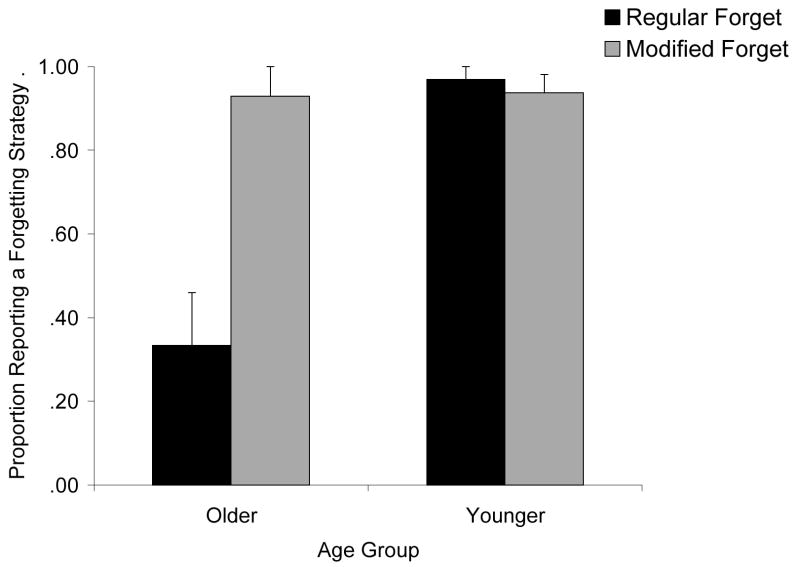

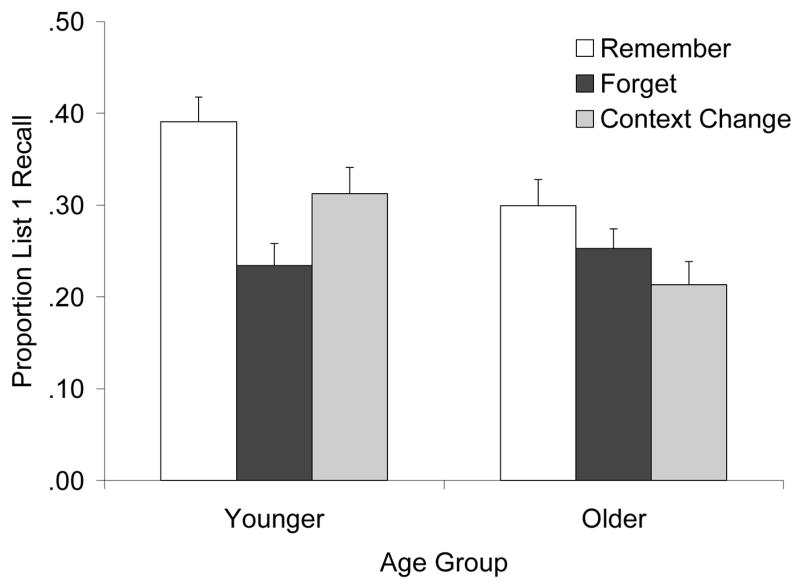

To analyze the costs of directed forgetting, an Age Group (older vs. younger) × Cue (forget, remember, or context-change) between-subjects ANOVA was conducted on proportion List 1 recall. The results are shown in Figure 1. There was a main effect of age group, F(1, 186) = 7.40, MSE = .021, p < .01, η2 = .038, indicating better List 1 memory in younger participants (.31) than older (.26). There was also a main effect of cue, F(2, 186) = 8.73, MSE = .021, p < .001, η2 =.086, which was moderated by a significant Cue × Age Group interaction, F(2, 186) = 3.23, MSE = .021, p < .05, η2 =.034, indicating that the effects of the cue depended on the age of the participant.

Figure 1.

Proportion of List 1 phrases recalled by age group and cue, Experiment 1. Error bars represent SE.

To follow up the interaction, we analyzed the effects of the cue separately for older and younger participants. For younger participants, the effect of cue was significant, F(2, 93) = 8.73, MSE = .022, p < .001, η2 =.158. Follow-up analyses revealed that the remember group recalled a larger proportion of List 1 items than either the forget group, t(62) = 4.36, p < .01, or the context-change group, t(62) = 2.00, p = .05. In sum, both the context-change manipulation and the forget instruction resulted in lower List 1 recall than the remember instruction for young participants, replicating earlier results1 (Sahakyan & Kelley, 2002; Sahakyan & Delaney, 2003).

For older participants, the effect of the cue only approached significance, F(2, 93) = 2.93, MSE = .020, p = .06, η2 =.059. Follow-up tests showed that the remember group recalled a larger proportion of List 1 items than the context-change group, t(62) = 2.27, p < .05. However, there was no reliable difference between the remember group and the forget group, t(62) = 1.32, p = .19. Thus, older adults showed reliable forgetting following a context-change manipulation, but not after a directed forgetting instruction. There was also no significant difference between the context-change group and the forget group, t(62) = 1.19, p = .24. However, more careful inspection of the data revealed that in the entire sample of older adults, there was one extreme outlier, who scored over 3.2 standard deviations above the mean. When this data point was excluded from the analyses, the difference between the context-change group and the forget group approached significance, t(61) = 1.82, p = .072. The context-change group recalled fewer items from List 1 (.19) than the forget group (.25) or the remember group (.30).

Directed Forgetting Benefits

To analyze the benefits of directed forgetting, we conducted an Age Group (older vs. younger) by Cue (forget, remember, or context-change) factorial ANOVA on proportion List 2 recall. Table 1 summarizes the results. There was a main effect of age group, F(1, 186) = 17.59, MSE = .019, p < .001, η2 = .086, indicating better List 2 memory in younger adults (.36) than older adults (.28). There was neither a significant main effect of cue, F < 1, η2 =.007, nor an interaction, F(2, 186) = 1.53, MSE = .019, η2 =.016. In other words, there were no directed forgetting benefits in either age group3.

Table 1.

List 2 recall by age group, condition, and experiment. Values in brackets represent standard deviations

| Younger | Older | |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | ||

| Remember | .37 (.17) | .24 (.13) |

| Forget | .38 (.14) | .29 (.12) |

| Context-Change | .33 (.13) | .30 (.13) |

| Experiment 2 | ||

| Remember | .45 (.16) | .33 (.16) |

| Regular Forget | .45 (.17) | .35 (.17) |

| Modified Forget | .37 (.14) | .31 (.16) |

Intrusion Errors

To ensure that different rates of intrusion errors across cue conditions were not responsible for any of our results, the number of intrusion errors on each list was analyzed using an Age Group × Cue ANOVA (for means, see Table 2). For List 2 intrusions onto List 1, the main effect of age group approached significance, F(1, 186) = 3.23, MSE = 1.38, p = .07, η2 = .018, reflecting more intrusions for older adults (1.14) than younger adults (.82). There were no other significant effects, all Fs < 1. For List 1 intrusions onto List 2, there were no significant effects, although the main effect of age group was in the direction of more errors for older adults than younger.

Table 2.

Intrusion Errors as a Function of List, Age and Cue

| Younger | Older | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On List 1 | On List 2 | On List 1 | On List 2 | |

| Experiment 1 | ||||

| Remember | 0.72 (.99) | 0.78 (.94) | 0.97 (1.05) | 0.69 (0.89) |

| Forget | 0.81 (.97) | 0.38 (.66) | 1.44 (1.45) | 0.85 (.99) |

| Context-Change | 0.94 (1.13) | 0.59 (.76) | 1.00 (1.41) | 0.77 (.90) |

| Experiment 2 | ||||

| Remember | 0.97 (1.20) | 1.00 (.98) | 1.28 (1.80) | 0.84 (1.11) |

| Regular Forget | 0.69 (1.09) | 0.72 (.68) | 1.44 (1.80) | 1.06 (1.16) |

| Modified Forget | 0.75 (1.11) | 0.69 (.82) | 0.73 (1.08) | 0.83 (1.05) |

Discussion

For younger adults, we replicated the List 1 results of earlier studies (Sahakyan & Delaney, 2003; Sahakyan & Kelley, 2002), with the remember group recalling more items than the forget group or the context-change group (see also Delaney & Sahakyan, 2007). However, although older adults showed reliable forgetting following a context change manipulation, they did not exhibit forgetting following a directed forgetting manipulation. The lack of directed forgetting with older adults is surprising because previous studies have reported reliable costs with similar samples (Sego, et al., 2006; Zellner & Bäuml, 2006).

Although older adults did not show significant directed forgetting, they did show forgetting following the context change manipulation, which appears to be inconsistent with the context hypothesis of directed forgetting. If context change underlies directed forgetting, one would expect to find similar patterns of forgetting following both the context change manipulation and a directed forgetting instruction. However, this reasoning neglects a critical component of the context-change hypothesis: initiating a mental context change in the forget group requires a self-initiated strategy. In the context change group, a strategy is already provided by the experimenter (i.e., engaging in diversionary thought), whereas in the directed forgetting group it needs to be self-initiated. Prior research shows that although older adults are capable of using effective memorization strategies, they do not spontaneously generate them as often as do younger adults (Kausler, 1994; West, 1995). Analogously, in the current experiments older adults were capable of using effective forgetting strategies (i.e., engaging in diversionary thought), but they might have been less likely to spontaneously do so on their own. An unprompted comment by one of our older participants provided a clue as to why our older adults might not be showing directed forgetting (and also with a title for the paper): in response to the forget instruction she said, “Oh, honey, I already forgot that.” Her comment led us to consider whether many older adults might believe that they did not have to do anything in order to forget, and therefore did not employ any strategy to change context in the forget group. In other words, we suspected that older adults were insensitive to the forget instruction because they saw no reason to try to forget. However, when provided with a strategy (e.g., being asked to imagine their childhood home), they showed significant forgetting.

Experiment 2

Because some of our older adults in Experiment 1 volunteered that they hadn’t done anything to forget because they were convinced of their own poor memory, we designed Experiment 2 with two purposes in mind. First, we wanted to prompt older adults to give verbal reports about their forgetting strategies to see if their lack of forgetting was linked to the absence of a forgetting strategy. Second, we wanted to develop a manipulation that would undermine their reason for not attempting to forget –namely, their belief that they would forget automatically because their memories were poor.

We therefore modified the directed forgetting instruction in an attempt to reduce older participants’ concerns about their own memory ability. It is known that older adults have negative stereotypes about the effects of aging on memory (Camp & Pignatiello, 1988; Hertzog & Hultsch, 2000; Hummert, 1990; Kite & Johnson, 1988; Lineweaver & Hertzog, 1998; Ryan, 1992), and believe that they will perform more poorly on memory tests compared to younger adults (Berry & West, 1993; Cavanaugh, 1996; Cavanaugh & Green, 1990; West & Berry, 1994). Negative beliefs about memory ability sometimes preclude older adults from engaging in effective strategies. Prior research demonstrates that when the task is framed in a way that reduces the salience of memory, age-related differences are significantly reduced or even eliminated (e.g., Kausler, 1991; Mitchell & Perlmutter, 1986; Perlmutter & Mitchell, 1982; Rahhal, Hasher, & Colombe, 2001).

For example, Rahhal et al. (2001) presented younger and older adults with trivia statements followed by immediate feedback regarding whether they were true or false. Afterwards, participants engaged in a yes/no recognition test accompanied by a source judgment for statements identified as old (i.e., indicating whether they were true or false statements). Although all participants were expecting an upcoming test, half received instructions emphasizing the memory nature of the task, whereas the remaining half received instructions emphasizing the knowledge acquisition aspect of the task. Age-related differences were present with the memory instruction, but were absent with the knowledge instructions.

These findings indicate that concerns about memory ability could influence older adults’ memory performance. Because negative stereotypes may have predisposed many older adults to think that they already forgot List 1 items, we created a modified version of the directed forgetting instructions to emphasize the need to attempt forgetting regardless of whether participants felt that they had already forgot.

Method

Participants

Another sample of 96 young adults and 96 older adults were selected from the University of North Carolina–Greensboro undergraduate participant pool and from community volunteers recruited in Sun City Center, Florida, respectively. None of the participants had previously participated in a directed forgetting study. The mean age was 19.1 (SD = 1.3) for the younger participants and 74.7 (SD = 5.0) for the older participants. The older adults had more years of education (M = 14.94, SD = 1.28) than the younger adults (M = 13.50, SD = 1.00), t(189) = 4.15, p < .01, and they also scored higher on the vocabulary test (M = 35.13, SD = 3.04) compared to younger adults (M = 28.95, SD = 4.40), t(189) = 11.28, p < .01. However, there was no significant difference in the total number of generated words on the FAS task between older adults (M = 48.5, SD = 14.1) and younger adults (M = 47.3, SD = 12.7), t < 1.

Materials

Two new lists of 12 action phrases were created. All phrases were related to camping trips and are listed in Appendix B. We switched from health actions to camping phrases because the former might have been too self-relevant for older adults, and therefore harder to forget. Each list served equally often as List 1 and List 2.

Procedure

As in Experiment 1, participants first filled out the demographic/health questionnaire, and completed the FAS task. They then studied the lists of phrases following the procedure of Experiment 1. The remember and standard forget groups were the same as in Experiment 1, with an exception that they did not engage in a counting task between the two lists because there was no context-change condition in this study (hence, no need to equate the time interval between the lists). Instead, we included a new group that received instructions emphasizing the need to try to forget even if the participants thought they had already forgotten – the modified forget group. Specifically, they were told:

The list of phrases you just saw was for practice, to familiarize you with the task and make you comfortable with the length of the list and the amount of time you have to study each phrase. There is no need to remember these items; just try to forget them. We have found that getting practice with the format and types of items is helpful, although sometimes people mistakenly recall phrases from the practice list, so you should make an attempt to forget the practice items. Do whatever you would normally do to forget something you do not want to remember, even if you think you have already forgotten…. Now I am about to show you is the real study list. Please read each phrase out loud and try to remember as many as you can. In all other respects, the procedures were identical to Experiment 1. Following the memory test, participants provided retrospective verbal reports regarding how they complied with the forgetting instructions, and what types of strategies they engaged in (if at all) in order to forget. Finally, they completed the Shipley vocabulary test.

Results

Directed Forgetting Costs

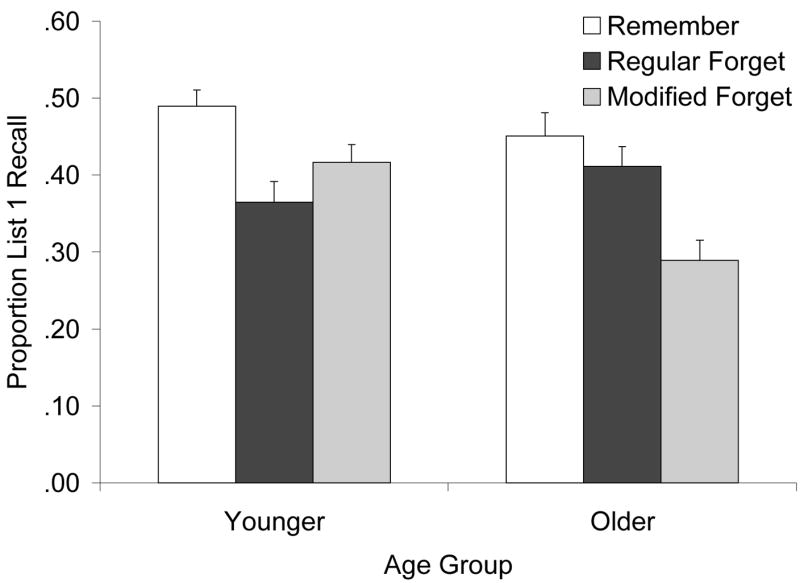

An Age Group (older vs. younger) × Cue (remember, standard forget, or modified forget) between-subjects ANOVA was conducted on proportion List 1 recall. The results are shown in Figure 2. The main effect of age group approached significance, F(1, 186) = 3.64, MSE = .021, p = .06, η2 = .019, in the direction of better List 1 memory for younger participants (.42) than older (.38). There was a significant main effect of cue, F(2, 186) = 11.02, MSE = .021, p < .001, η2 = .106, but it was moderated by a significant Cue × Age Group interaction, F(2, 186) = 5.80, MSE = .021, p < .005, η2 =.059, indicating that the effects of the cue depended on the age of the participant.

Figure 2.

Proportion of List 1 phrases recalled by age group and cue, Experiment 2. Error bars represent SE.

To follow up the interaction, we separately examined the impact of the cue on List 1 recall for each age group. For younger participants, there was a significant main effect of cue, F(2, 93) = 6.95, MSE = .018, p < .005, η2 = .130. Follow-up tests showed that the remember group recalled more than the standard forget group, t(62) = 3.63, p < .005, and the modified forget group, t(62) = 2.35, p < .05. However, the latter two groups did not differ, t(62) = 1.47, p = .15.

For older participants, there was also a significant main effect of cue, F(2, 93) = 9.52, MSE = .024, p < .001, η2 = .170. However, unlike for younger participants, there was no significant difference between the remember group and the standard forget group, t < 1, replicating the lack of costs reported in Experiment 1. Compared to the remember group, the modified forget group produced significant directed forgetting costs, t(62) = 4.06, p < .01, and also significantly greater forgetting than the standard forget group, t(62) = 3.36, p < .001. Thus, we obtained significant directed forgetting with the older adults, but only using modified instructions to forget. Furthermore, the modified forget instruction created greater amount of forgetting than the standard forget instruction, but this was observed only with older adults.

Use of Any Forgetting Strategy and Directed Forgetting Costs

Why did older adults show forgetting only in the modified forget condition? We coded the retrospective strategy reports of participants indicating what strategy they were using to try to forget, grouping them into either “doing nothing” or as “attempting some kind of strategic forgetting”. Figure 3 shows the proportion of people who reported any sort of strategic forgetting as a function of age group and cue; the remaining participants reported doing “nothing” to forget. Using between-subjects ANOVA, we analyzed whether the probability of selecting a deliberate forgetting strategy varied as a function of Cue (standard forget vs. modified forget) and Age Group (older vs. younger). A significant main effect of cue indicated that the standard forget group employed deliberate forgetting strategies less often (65% of the time) than the modified forget group (93% of the time), F(1, 89) = 19.86, MSE = .080, p < .001, η2 = .182. Older participants also employed deliberate forgetting strategies less often (63% of the time) than younger participants (95% of the time), F(1, 89) = 25.92, MSE = .080, p < .001, η2 = .226. However, these effects were moderated by a significant two-way interaction, F(1, 89) = 24.51, MSE = .080, p < .001, η2 = .216, indicating that younger adults were equally likely to employ forgetting strategies with the standard forget cue and the modified forget cue, t < 1, whereas older adults employed forgetting strategies less often with the standard forget cue than with the modified forget cue, t(27) = 4.03, p < .01. In sum, for young participants, virtually everyone tried to do something to forget, but for older participants, apparently more prompting was needed in order to engage them in deliberate forgetting strategies.

Figure 3.

Proportion of participants by age group and cue who reported using a strategy to try to forget, Experiment 2. Error bars represent SE.

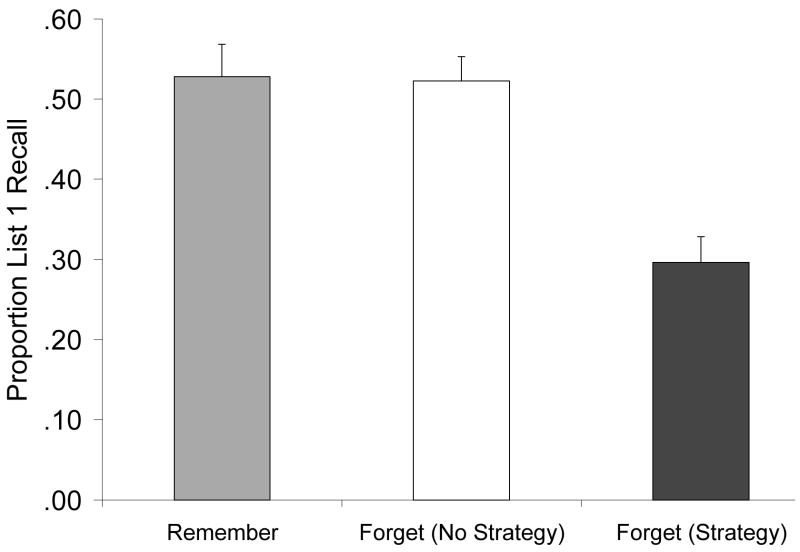

The next question was whether the differences in older adults’ usage of forgetting strategy between the regular forget cue and the modified forget cue could explain the recall differences between the two groups. We therefore first regressed out the impact of strategy usage on older adults’ proportion List 1 recall. After doing so, there was no longer any significant effect of the cue, F(2, 41) = 1.59, MSE = .017, p = .22, η2 = .072. Thus, once the differences in recall due to strategy were removed, there was no longer any reliable effect of the cue, indicating that the effects of the different strategy choices could explain the group differences4. Figure 4 illustrates the impact of forgetting strategies on older adults’ List 1 recall by showing the mean recall rates for those reporting no forgetting strategy and those reporting a forgetting strategy, regardless of whether they were in the modified forget or standard forget condition.

Figure 4.

Proportion of List 1 recall for older participants as a function of their forgetting strategy, Experiment 2. Error bars represent SE.

Directed Forgetting Benefits

An Age Group × Cue ANOVA was conducted on the proportion of List 2 phrases recall. The results are summarized in Table 1. A significant main effect of age group emerged, F(1, 186) = 16.27, MSE = .025, p < .001, η2 = .080, with older participants recalling a smaller proportion of List 2 phrases (.33) than younger participants (.42). The main effect of cue was not significant, F(2, 186) = 2.31, MSE = .025, p = .10, η2 = .024, and neither was the Age Group × Cue interaction, F < 1. In other words, no directed forgetting benefits were found in either age group.

Intrusion Errors

As in Experiment 1, an Age Group × Cue ANOVA was conducted on the number of intrusion errors (see Table 2). For intrusions onto List 1, only the main effect of age group approached significance, F(1, 186) = 3.00, MSE = 1.92, p = .09, η2 = .016. It was in the direction of more errors for older adults (1.15) than younger adults (0.80). No effects approached significance for intrusions onto List 2.

Discussion

As in Experiment 1, we obtained significant directed forgetting costs among the younger participants. However, older participants as a group did not show directed forgetting costs with the standard directed forgetting instruction. Based on their strategy reports, the majority of older adults did not deploy any strategy in order to forget.

When we created a new instruction that emphasized the need to forget, older adults began to use forgetting strategies and then showed the typical directed forgetting costs. The new instruction had no impact on younger adults, who were already using forgetting strategies.

A further analysis comparing the standard and modified forget instructions suggested that the differences could be attributed to the proportion of people that engaged in a deliberate forgetting strategy. Many older adults attempted a forgetting strategy following the modified instructions than following the standard instructions. However, even in the modified forget condition some older participants did not employ any forgetting strategy, and they also failed to show directed forgetting costs. In contrast, older participants who engaged in deliberate strategies to accomplish forgetting showed significant directed forgetting comparable to those demonstrated by younger adults.

The results suggest that older adults are capable of intentionally forgetting things, as found by earlier researchers. However, they may need to receive instructions that clearly suggest the importance of trying to forget, irrespective of their perception about their own memory at that moment. Finally, we did not obtain the benefits of directed forgetting for either age group.

General Discussion

In two experiments, we obtained neither the costs nor the benefits of directed forgetting with older adults. These null effects were observed with both health-relevant action phrases (Experiment 1) and camping-related phrases (Experiment 2). Meanwhile, younger adults showed significant directed forgetting costs but no benefits in either experiment.

In Experiment 1, older adults showed forgetting when provided with a strategy that leads to forgetting (i.e., thinking of something else between the lists). Unlike younger adults, older adults were less likely to spontaneously initiate such strategies. Experiment 2 obtained directed forgetting costs with older adults when the instructions to forget were modified to emphasize the need to forget even if they felt they had already forgotten. Thus, although the standard instructions produced non-significant results with older adults, both modified instructions and the experimenter-provided strategy yielded significant forgetting of List 1 items comparable in magnitude to younger adults’ forgetting. These results suggest that the ability to forget unwanted information is preserved in aging, but that older adults may sometimes require instructions that emphasize the need to forget.

Our studies demonstrated that directed forgetting does not occur automatically; rather, it is consciously-directed and strategic. Directed forgetting required attempting deliberate forgetting through strategies such as focusing on other things or self-distraction with different thoughts. Older adults in our studies were less likely to engage in behavior that would lead to forgetting of unwanted information – unlike younger adults, who almost always reported a strategy for forgetting. Many older adults spontaneously explained that there was no need to attempt to forget the first list, because they thought they had already forgotten it. Some typical comments that older adults volunteered when we asked them about their strategy for forgetting included: “I didn’t attempt to forget anything because I wouldn’t remember much anyway, I have a bad memory,” “forgetting wasn’t worth the effort, I already forgot,” and “when you age, forgetting doesn’t require effort; it happens all the time.”

Although the modified forgetting instructions in Experiment 2 did not provide incentive to forget and instead downplayed older adults’ concerns about their own memory ability, research from other domains suggests that older adults are quite capable of controlling their memory performance when instructions provide incentives against recalling certain types of items (e.g., Castel, Farb, & Craik, 2007). For example, in one of their experiments Castel et al. (2007) had participants study a list of items that were associated with positive or negative point values. Participants had to score a high point total by recalling words associated with high values and avoiding negative value words. Older adults were as good as younger adults at avoiding recalling items worth negative points. Conceptually, Castel et al.’s (2007) selective remembering paradigm shares similarities with directed forgetting task, in which to-be-forgotten (TBF) items can be thought of as having negative value points. However, in directed forgetting tasks, there is typically no disincentive for mistakenly recalling TBF items and therefore older participants might not perceive the need to forget those items -- especially if they feel they will not remember them later anyway. Thus, the lack of directed forgetting among older adults may be linked to the lack of incentives to forget rather than older adults’ core competencies.

Mechanisms Mediating Decisions to Engage in Forgetting Strategies

Whereas older adults often expressed to us that they feel they already forgot (in response to forget instruction), younger adults in contrast used to say, “How am I going to forget these words once they are in my head?” These comments suggest that people’s decisions to use deliberate forgetting strategies likely involve metacognitive processes. Participants might rely on mnemonic cues derived from online processing of List 1 items to predict how much they will remember on the test (e.g., Koriat, 1997), and use those predictions to decide whether or not to employ forgetting strategies. For example, the ease with which items are retrieved during learning affects the experience of knowing and serves as a basis for recall prediction (Benjamin & Bjork, 1996). Older adults may have underestimated how many List 1 items they remembered because they typically have ineffective retrieval. They either make only a cursory attempt to retrieve (e.g., Jacoby, Shimizu, Velanova, & Rhodes, 2005) or avoid retrieval-based strategies altogether (e.g., Touron & Hertzog, 2004). If their memory monitoring yielded pessimistic predictions of future recall, they would be less likely to initiate strategic behaviors to comply with forgetting instructions. Negative stereotypes might also interfere with monitoring by preoccupying older adults with concerns and worries about their memory, diminishing resources devoted to monitoring. Activating negative stereotypes impairs performance on other cognitive tasks (e.g., Steele & Aronson, 1995; Rahhal et al. 2001).

Recall predictions can also be based on inferences from beliefs or theories about one’s competence (Kelley & Jacoby, 1996; Koriat, 1997). Koriat, Bjork, Sheffer and Bar (2004) showed that younger adults are oblivious to the effects of forgetting and do not spontaneously consider the notion of forgetting when making recall predictions. However, this may be different for older adults given that the notion of memory decline with age is more salient for them. Upon receiving the forget instruction, older adults could have activated the notion of forgetting and relied on pre-existing beliefs about their memory ability, rather than engaging in more effortful process of memory monitoring. More research is needed to examine how metacognitive predictions of recall relate to memory performance in tasks that emphasize forgetting as opposed to remembering.

Our participants were slightly older than Sego et al.’s participants and Zellner and Bäuml’s participants. Therefore, one might suspect that only old-old participants were insensitive to directed forgetting, whereas young-old participants showed significant directed forgetting. A median split analyses on age showed that the young-old participants recalled the same amount in the remember condition (.37) as in the forget (.36). For the old-old participants, there was a numerical trend towards directed forgetting (.36 vs. .30), but it was not significant, t(63) = 1.44, p = .17. Thus, it is unlikely that the difference in findings was driven by the slightly older sample in the current studies. If anything, the reverse was true in our study.

Finally, older adults’ insensitivity to directed forgetting could be potentially related to their diminished working memory capacity (e.g., Hale, Myerson, Emery, Lawrence, DuFault, 2007). Prior research showed that people with low working memory capacity are less likely to show directed forgetting costs and context-change costs than people with high working memory capacity (Delaney & Sahakyan, 2007; Soriano & Bajo, 2007). However, the presence of costs in older adults in earlier studies and also using our modified forgetting instructions underscores the dissimilarity between older adults and low-span younger adults (see Sego et al, 2006; Zellner and Bäuml, 2006). Low-span younger adults likely show deficits in intentional forgetting for different reasons than the strategy-based effects observed here, because unlike older adults, low-span younger adults show little forgetting even when a strategy of engaging in diversionary thought is provided to them.

What accounts for the absence of directed forgetting benefits?

In our studies, we initially observed non-significant directed forgetting with older adults, but with additional prompting and emphasizing the need to forget, older adults showed significant directed forgetting that was comparable in magnitude to that of younger adults. We suspect that participants in the Zellner and Bäuml (2006) and Sego et al. (2006) studies might have been more likely to spontaneously engage in effective forgetting strategies than our participants. Our older adults have been inadvertently primed with stereotypes about memory and aging because the recruitment procedures and the consent forms specified that we were interested in examining memory changes across lifespan.

Neither of our experiments obtained directed forgetting benefits in younger or older adults. Reports of failures to detect the benefits of forgetting (despite obtaining significant costs) are growing in the literature, and our understanding of the mechanisms that produce the benefits is incomplete. To date, the two main accounts of the directed forgetting benefits are the interference reduction account and the strategy change account.

The interference reduction account attributes the benefits to reduced proactive interference on List 2 in the forget group that occurs either from inhibition of List 1 items (e.g., Bjork & Bjork, 1996), or from contextual differentiation between the lists (Sahakyan & Kelley, 2002). The strategy change account attributes enhanced List 2 recall in the forget group to the choice of better encoding strategies (Sahakyan & Delaney, 2003; 2005). In the current studies, either account can potentially explain the absence of benefits in either age group.

We suspect that the choice of related materials partly accounts for our failure to detect the benefits. In one of their studies, Zellner and Bäuml (2006) also reported non-significant benefits in either age group with semantically related lists. Findings from cued recall (e.g., using A–B, A–B′ paradigm; for reviews, see Anderson & Neely, 1996) and free recall studies (Sahakyan & Goodmon, 2007) indicate that semantic relationships between lists drastically reduce interference compared to unrelated lists. Because our stimuli included short lists of related actions, they might have accumulated little interference in the remember group, leaving insufficient room to detect the directed forgetting benefits. Interestingly, although older adults are more vulnerable to interference than younger adults (for reviews, see Lustig & Hasher, 2006; Kane & Hasher, 1995), they also showed no benefits in the modified forget condition despite showing the costs. These findings provide another demonstration that the costs and the benefits of directed forgetting are not always observed together.

The strategy-change account provides a different interpretation for the benefits. When study lists include unrelated items, forget participants often report switching to encoding strategies that interrelate list items (e.g., Sahakyan & Delaney, 2003). Our semantically related phrases may have made it difficult to discover a better encoding strategy in the forget group. Alternatively, participants may not perceive a need to change their study strategy because related items seem easier to learn than unrelated items (which could also explain the absence of the benefits).

Effectiveness of the context-change instruction

In prior published studies, we reported similar amounts of forgetting following context-change and directed forgetting instructions. To create mental context change, we often instruct participants to think about their childhood home and describe it aloud. Recent research shows that this instruction is more effective the further back in time participants mentally travel – specifically, imagining one’s childhood home impairs memory more than imagining one’s current home (Kelley, Zimmerman, Delaney & Sahakyan, 2007). Because context naturally drifts with the passage of time, thinking about more temporally distant events should produce larger context changes than recent events.

In Experiment 1, younger adults showed less forgetting following a context-change instruction than a forget instruction. Our young participants were drawn from two different universities – the University of Florida and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. The latter is a commuter campus, where many students attend school while living at their parents’ home. Thus, instructions to imagine their childhood home may have been less effective for them as a context change task as it was their current house. Including university as a factor in List 1 analyses produced a significant interaction with cue, F(2, 90) = 4.68, p < .05. The UNCG participants showed no context-change effect, but were identical to the UF participants in the forget and remember groups. Excluding the UNCG participants eliminated the differences between the context-change and forget groups for young participants (p = .23).

The hypothesis that mentally traveling into a distant past produces more forgetting gained some support also in older adults. In the context-change group, a significant negative correlation was found between the chronological age (ranging from 65 to 85 years old) and List 1 recall , r = −.38, p < .05. In other words, the older participants were, the more mentally traveling back in time hurt their recall. Either mentally traveling into a distant past produced a larger change of context for them, or alternatively, old-old participants may be less likely to spontaneously reinstate List 1 context during the test, which could also enhance the magnitude of forgetting.

Conclusions

Our studies showed that forgetting strategies play an important role in directed forgetting. Other populations also show reduced directed forgetting, such as frontal lobe patients (e.g., Conway & Fthenaki, 2003), adults with AD/HD (e.g., White & Marks, 2004), and children (e.g., Harnishfeger & Pope, 1996). Reduced directed forgetting among these populations is often attributed to underdeveloped or impaired inhibitory abilities (but cf. Delaney & Sahakyan [2007] for a competing view suggesting impaired contextual binding or shifting). However, if formulating a conscious strategy is central to intentional forgetting, then perhaps these populations have difficulty formulating or initiating a forgetting strategy. A context-change manipulation (which provides a forgetting strategy) or a modified forget instruction (which circumvents the choice to attempt forgetting or not) might lead to successful directed forgetting in other populations.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant RO3 AG23823-01 to Lili Sahakyan and Peter F. Delaney.

Appendix A. Action Phrases Used in Experiment 1

| List A | List B |

|---|---|

| Swallow an aspirin | Apply the eye drops |

| Rub ointment | Adjust the hearing aid |

| Change the bandage | Push the wheelchair |

| Draw a bath | Take your temperature |

| Donate blood | Measure your cholesterol |

| Get a chest x-ray | Buy vitamins |

| Call an ambulance | Weigh yourself |

| Brush the teeth | Sniff nasal spray |

| Check your pulse | Massage the shoulders |

| Show insurance card | Get an eye exam |

| Drink orange juice | Get a flu shot |

| Heat the electric blanket | Read the medical report |

Appendix B. Action Phrases Used in Experiment 2

| List A | List B |

|---|---|

| Throw the frisbee | Extinguish the campfire |

| Climb a mountain | Tie a rope |

| Ride your bike | Strike a match |

| Wear sunglasses | Check the compass |

| Fly a kite | Zip the sleeping bag |

| Paddle the canoe | Put on your backpack |

| Eat a granola bar | Chop firewood |

| Fold the map | Boil some water |

| Catch fish | Pitch the tent |

| Apply mosquito repellant | Roast the marshmallows |

| Gaze at the stars | Have a picnic |

| Pick some berries | Tell ghost stories |

Footnotes

Lili Sahakyan, Peter F. Delaney, and Leilani B. Goodmon, University of North Carolina – Greensboro. Leilani B. Goodmon is now at St. Leo University.

There was also a significant difference between the forget and the context-change groups, t(62) = 2.10, p <.05 – a point we discuss further in the general discussion.

The only finding that affected by the exclusion of the outlier was that the main effect of Cue in older adults’ List 1 recall became significant (as opposed to approaching significance as reported earlier), F(2, 92) = 4.40, MSE = .018, p < .05.

The pattern of results was unaffected by the exclusion of the outlier in the analyses.

The reverse analysis – regressing out the effects of the cue and then examining if additional variance can be captured by the strategy usage – showed that strategy accounted for additional variance above and beyond the cue alone. The analysis involved first performing a one-way ANOVA on the proportion of List 1 recall in older adults (with cue – standard versus modified forget – as the independent variable). Then the unstandardized residuals from the ANOVA were subjected to an independent samples t-test that compared participants who reported not engaging in any forgetting strategy to participants who reported using deliberate forgetting strategies. The mean for participants using a forgetting strategy was .033 lower than the group mean, while the mean for participants who reported using no forgetting strategy was .054 higher than the group mean, for a total difference of .087, t(27) = 1.99, p = .06. Thus, even once the effects of the cue were statistically controlled, participants’ strategy choices affected their List 1 recall.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/pag/.

References

- Anderson JR, Bower GH. Human associative memory. Washington, DC: Winston; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MC, Neely JH. Interference and inhibition in memory retrieval. In: Bjork EL, Bjork RA, editors. Memory: Handbook of perception and cognition. New York: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 237–313. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan A, Bäuml KH, Pastötter B. No inhibitory deficit in older adults’ episodic memory. Psychological Science. 2007;18:72–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basden BH, Basden DR, Gargano GJ. Directed forgetting in implicit and explicit memory tests: A comparison of methods. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1993;19:603–616. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin AS. The effects of list-method directed forgetting on recognition memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2006;13:831–836. doi: 10.3758/bf03194005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin AS, Bjork RA. Retrieval fluency as a metacognitive index. In: Reder LM, editor. Implicit memory and metacognition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 309–338. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JM, West RL. Cognitive self-efficacy in relation to personal mastery and goal setting across the life span. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1993;16:351–379. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork RA. Retrieval inhibition as an adaptive mechanism in human memory. In: Roediger HL III, Craik FIM, editors. Varieties of Memory and Consciousness: Essays in Honour of Endel Tulving. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1989. pp. 309–330. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork EL, Bjork RA. Continuing influences of to-be-forgotten information. Consciousness & Cognition. 1996;5:176–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork EL, Bjork RA. Intentional forgetting can increase, not decrease, residual influences of to-be-forgotten information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2003;29:524–531. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.29.4.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BjorkELBjork RA, Anderson MA. Varieties of goal-directed forgetting. In: Golding JM, MacLeod CM, editors. Intentional Forgetting: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 103–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork RA, LaBerge D, LeGrand R. The modification of short-term memory through instructions to forget. Psychonomic Science. 1968;10:55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski JG, Benton AL, Spreen O. Word fluency and brain damage. Neuropsychologia. 1967;5:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Camp CJ, Pignatiello MF. Beliefs about fact retrieval and interential reasoning across the adult lifespan. Experimental Aging Research. 1988;14:89–97. doi: 10.1080/03610738808259729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel AD, Farb N, Craik FIM. Memory for general and specific value information in younger and older adults: Measuring the limits of strategic control. Memory & Cognition. 2007;35:689–700. doi: 10.3758/bf03193307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh JC. Memory self-efficacy as a moderator of memory change. In: Blanchard-Fields F, Hess TM, editors. Perspectives on cognitive change in adulthood and aging. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996. pp. 488–507. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh JC, Green EE. I believe, therefore I can: Personal beliefs and memory aging. In: Lovelace EA, editor. Aging and cognition: Mental processes, self-awareness, and interventions. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1990. pp. 189–230. [Google Scholar]

- Chalfonte BL, Johnson MK. Feature memory and binding in young and older adults. Memory & Cognition. 1996;24:403–416. doi: 10.3758/bf03200930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway MA, Fthenaki A. Disruption of inhibitory control of memory following lesions to the frontal and temporal lobes. Cortex. 2003;39:667–686. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70859-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney PF, Sahakyan L. Unexpected costs of high working memory capacity following directed forgetting and context change manipulations. Memory & Cognition. 2007;35:1074–1082. doi: 10.3758/bf03193479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earles JL. Adult age differences in recall of performed and non-performed items. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:638–648. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.4.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiselman RE, Bjork RA, Fishman DL. Disrupted retrieval in directed forgetting: A link with posthypnotic amnesia. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1983;112:58–72. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.112.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillund G, Shiffrin RM. A retrieval model for both recognition and recall. Psychological Review. 1984;91:1–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale S, Myerson J, Emery LJ, Lawrence BM, DuFault C. Variation in working memory across the life span. In: Conway AR, Jarrold C, Kane MJ, Miyake A, Towse JN, editors. Variation in working memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 194–224. [Google Scholar]

- Harnishfeger KK, Pope RS. Intending to forget: The development of cognitive inhibition in directed forgetting. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1996;62:292–315. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1996.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L, Zacks RT. Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In: Bower GH, editor. The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Hultsch DF. Metacognition in adulthood and old age. In: Craig FIM, Salthouse TA, editors. Handbook of aging and cognition 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hummert ML. Multiple stereotypes of elderly and young adults: A comparison of structure and evaluations. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:182–193. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys MS. Relational information and the context effect in recognition memory. Memory & Cognition. 1976;4:221–232. doi: 10.3758/BF03213167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs B, Prentice-Dunn S, Rogers RW. Understanding persistence: An interface of control theory and self-efficacy theory. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1984;5:333–347. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby LL, Shimizu Y, Velanova K, Rhodes MG. Age differences in depth of retrieval: Memory for foils. Journal of Memory and Language. 2005;52:493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson H. Processes of successful intentional forgetting. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:274–292. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK. Identifying the origin of mental experience. In: Myslobodsky MS, editor. The mythomanias: The nature of deception and self-deception. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1997. pp. 133–180. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Chalfonte BL. Binding complex memories: The role of reactivation and the hippocampus. In: Schacter DL, Tulving E, editors. Memory systems 1994. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1994. pp. 311–350. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Hashtroudi S, Lindsay DS. Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:3–28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, Hasher L. Interference. In: Maddox G, editor. Encyclopedia of aging. 2. New York: Springer Publishing; 1995. pp. 514–516. [Google Scholar]

- Kausler DH. Experimental psychology, cognition and human aging. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kausler DH. Learning and memory in normal aging. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley CM, Jacoby LL. Adult egocentrism: Subjective experience versus analytic bases for judgment. Journal of Memory and Language. 1996;35:157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley CM, Zimmerman C, Delaney PF, Sahakyan L. Does traveling backward in time induce forgetting of the present?; Poster presented at the 48th Annual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society; Long Beach, CA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME, Johnson BT. Attitudes toward older and younger adults: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 1988;3:233–244. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.3.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koriat A. Monitoring one’s own knowledge during study: A cue-utilization approach to judgments of learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1997;126:349–370. [Google Scholar]

- Koriat A, Bjork RA, Sheffer L, Bar SK. Predicting one’s own forgetting: The role of experience-based and theory-based processes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2004;122:643–656. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.133.4.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lineweaver TT, Hertzog C. Adults’ efficacy and control beliefs regarding memory and aging: Separating general from personal beliefs. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 1998;5:264–296. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig C, Hasher L. Interference. In: Maddox G, editor. Encyclopedia of Aging. 4. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2006. pp. 553–555. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod CM. Directed forgetting. In: Golding JM, MacLeod CM, editors. Intentional Forgetting: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DB, Perlmutter M. Semantic activation and episodic memory: Age similarities and differences. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh-Benjamin M. Adult age differences in memory performance: Tests of an associative deficit hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2000;26:1170–1187. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.26.5.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastötter B, Bäuml KH. The crucial role of post-cue encoding in directed forgetting and context-dependent forgetting. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2007;33:977–982. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter M, Mitchell DB. The appearance and disappearance of age differences in adult memory. In: Craik FIM, Trehub SE, editors. Aging and cognitive processes. New York: Plenum; 1982. pp. 127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rahhal TA, Hasher L, Colombe SJ. Instructional Manipulations and Age Differences in Memory: Now You See Them, Now You Don’t. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2001;16:697–706. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.4.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan EB. Beliefs about memory changes across the adult life span. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1992;47:41–46. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.1.p41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakyan L. The destructive effects of the “forget” instructions. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2004;11:555–559. doi: 10.3758/bf03196610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakyan L, Delaney PF. Can encoding differences explain the benefits of directed forgetting in the list-method paradigm? Journal of Memory and Language. 2003;48:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Sahakyan L, Delaney PF. Directed forgetting in incidental learning and recognition testing: Support for a two-factor account. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2005;31:789–801. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.31.4.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakyan L, Delaney PF, Kelley CM. Self-evaluation as a moderating factor in strategy change in directed forgetting benefits. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2004;11:131–134. doi: 10.3758/bf03206472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakyan L, Delaney PF, Waldum ER. Forgetting is easier after two “shots” than after one. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.34.2.408. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakyan L, Goodmon LB. The influence of directional associations on directed forgetting and interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2007;33:1035–1049. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.6.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakyan L, Kelley CM. A contextual change account of the directed forgetting effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2002;28:1064–1072. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.28.6.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Norman KA, Koustaal W. The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:289–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sego SA, Golding JM, Gottlob LR. Directed forgetting in older adults using the item and list methods. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2006;13:95–114. doi: 10.1080/138255890968682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard ED, MacLeod CM. List method directed forgetting: Return of the selective rehearsal account. In: Ohta N, MacLeod CM, Uttl B, editors. Dynamic cognitive processes. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 2005. pp. 219–248. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano MF, Bajo MT. Working memory resources and interference in directed forgetting. Psicologia. 2007;28:63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer WD, Raz N. Differential effects of aging on memory for content and context: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:527–539. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:797–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touron DR, Hertzog C. Distinguishing age differences in knowledge, strategy use, and confidence during strategic skill acquisition. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:452–466. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RL. Compensatory strategies for age-associated memory impairment. In: Baddeley AD, Wilson BA, Watts FN, Craik, Salthouse TA, editors. The handbook of aging and cognition Handbook of memory disorders. New York: Wiley; 1995. pp. 481–500. [Google Scholar]

- West RL, Berry JM. Age declines in memory self-efficacy: General or limited to particular tasks and measures? In: Sinnott JD, editor. Handbook of adult lifespan learning. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 1994. pp. 426–445. [Google Scholar]

- White HA, Marks W. Updating memory in list-method directed forgetting: Individual differences related to Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:1453–1462. [Google Scholar]

- Zachary RA. The manual of the Shipley Institute of Living Scale. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zacks RT, Radvansky G, Hasher L. Studies of directed forgetting in older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1996;22:143–156. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.22.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zellner M, Bäuml KH. Inhibitory deficits in older adults: List-method directed forgetting revisited. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2006;32:290–300. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.32.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]