Abstract

Papillomavirus E2 proteins are critical regulatory proteins that function in replication, genome segregation, and viral transcription, including control of expression of the viral oncogenes, E6 and E7. Sumoylation is a post-translational modification that has been shown to target and modulate the function of many transcription factors, and we now demonstrate that E2 proteins are sumoylated. Both bovine and human papillomavirus E2 proteins bind to the SUMO conjugation enzyme, Ubc9, and using in vitro and E. coli sumoylation systems, these E2 proteins were readily modified by SUMO proteins. In vivo experiments further confirmed that E2 can be sumoylated by SUMO1, SUMO2, or SUMO3. Mapping studies identified lysine 292 as the principal residue for covalent conjugation of SUMO to HPV16 E2, and a lysine 292 to arginine mutant showed defects for both transcriptional activation and repression. The expression levels, intracellular localization, and the DNA-binding activity of HPV16 E2 were unchanged by this K292R mutation, suggesting that the transcriptional defect reflects a functional contribution by sumoylation at this residue. This study provides evidence that sumoylation has a role in the regulation of papillomavirus E2, and identifies a new mechanism for the modulation of E2 function at the post-translational level.

Keywords: Sumoylation, transcription, keratinocytes

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infects both genital and cutaneous epithelium, and high risk HPV is the causative agent in cervical cancer. The E2 early protein is a key regulatory protein that functions in viral replication (Chiang et al., 1992; Demeret et al., 1995; Stubenrauch, Colbert, and Laimins, 1998), genome segregation (McPhillips et al., 2006; You et al., 2004), and transcriptional control (Demeret et al., 1997; Kovelman et al., 1996). E2 binds to multiple sites in the upstream regulatory region (URR) and regulates early promoter expression in both a positive (low E2 concentration) and negative (high E2 concentration) fashion (Demeret et al., 1997). E2 also interacts with several cellular factors such as Sp1 (Steger, Schnabel, and Schmidt, 2002), YY1 (Lee, Broker, and Chow, 1998), C/EBP (Hadaschik et al., 2003), and Brd4 (Baxter et al., 2005; You et al., 2004), and these interactions further contribute to viral and cellular transcriptional activity.

The life cycle of HPVs is closely linked to the epithelial differentiation scheme of the infected host keratinocyte (Longworth and Laimins, 2004), and BPV1 E2 was found to accumulate and be more stabilized in the stratum spinosum (Penrose and McBride, 2000). Such differentiation-dependent changes in E2 levels likely provide some control of E2 transcriptional activity during the virus life cycle. Alternatively, the activity of many transcription factors is regulated by post-translational modifications, but this type of control has not been examined thoroughly for E2 proteins. A recent study showed that overall sumoylation was upregulated during keratinocyte differentiation (Deyrieux et al., 2007), suggesting that this modification might be globally coordinating transcription and could also be relevant to E2 activity.

Sumoylation is a post-translational modification, prevalent among transcription factors, where the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) is attached to the substrate proteins in a reversible manner (Matunis, Coutavas, and Blobel, 1996). There are three principle SUMO proteins: SUMO1, SUMO2, and SUMO3. SUMO 2 and 3 are 98% identical and form a distinct group from SUMO1 with whom they share only ~ 50% identity. The process and enzymes involved in sumoylation are functionally similar to those enzymes catalyzing the attachment of ubiquitin to its substrates (Hay, 2005). Sumoylation occurs in multiple steps with SUMO first attached to the heterodimeric activating enzyme, SAE1/SAE2, in an ATP-dependent fashion. Next, the activated SUMO is covalently transferred to Ubc9, the SUMO-specific conjugating enzyme (Desterro et al., 1999). The final transfer of SUMO from Ubc9 to the substrate can occur directly, but is enhanced by SUMO ligases such as the PIAS family proteins (Schmidt and Muller, 2003). Addition of SUMO occurs exclusively at lysine residues, most commonly in the acceptor motif ψKx(E/D) where ψ is a large hydrophobic amino acid, K is the target lysine, x is any amino acid, and the fourth position (E/D) is either glutamic or aspartic acid. SUMO attached to the substrate lysine can be specifically cleaved by SUMO proteases (SENPs), making this a dynamic process of modification/demodification (Mukhopadhyay and Dasso, 2007). Modification by SUMO is believed to play a role in various cellular processes, including protein-protein interaction, subcellular localization, and transcriptional regulation (Dohmen, 2004). Sumoylation most commonly represses transcriptional activity, but examples of transcriptional activation have also been reported (Goodson et al., 2001; Hong et al., 2001; Rodriguez et al., 1999; Wei, Scholer, and Atchison, 2007).

Several transcriptional regulatory early proteins of other DNA virus families, such as Rta of Epstein-Barr virus and K-bZIP of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, have been shown to be sumoylated, and the transcriptional activities of these proteins are modulated by SUMO modification (Chang et al., 2004; Izumiya et al., 2005). Inspection of E2 protein sequences revealed potential sumoylation sites implying that this modification may be similarly important for E2 transcriptional activity. In the present study, we demonstrate binding between Ubc9 and various papillomavirus E2 proteins in vitro, sumoylation of both BPV1 E2 and HPV18 E2 in vitro and in E. coli, and in vivo sumoylation of HPV16 E2 at lysine 292. Mutation of lysine 292 to arginine eliminated sumoylation, indicating that this amino acid was the major sumoylation target site. Furthermore, the transcriptional activity of the 16E2 lysine 292 to arginine mutant was reduced compared to the wild-type HPV16 E2 on both an E2-activated and an E2-repressed promoter. However, the mutant E2 protein was expressed at similar levels as wild-type E2, and neither the DNA binding activity nor the subcellular localization of E2 was affected by this mutation, suggesting that the transcriptional defect was related to the absence of sumoylation.

Results

BPV1 and HPV E2 proteins interact with Ubc9 in vitro

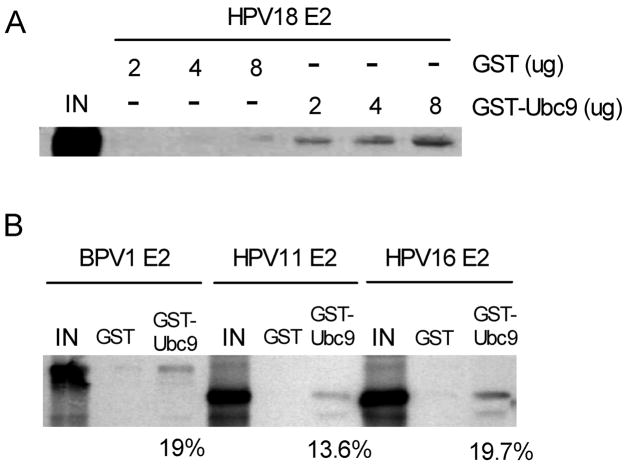

Examination of sequences from several common high-risk and low-risk HPV E2 proteins revealed that all had high probability sumoylation sites, though no single predicted sumoylation site was well conserved between the high-risk and low-risk sequences (Table 1). Nonetheless, the high-risk E2 types all had 2–3 good potential sumoylation sites, as did BPV1 E2 (not shown), so we focused on the E2 proteins from HPV16, HPV18, and BPV1 for these studies. Typically, sumoylated proteins bind directly to the SUMO-specific conjugating enzyme, so GST pull-down assays were performed with a bacterially expressed GST-Ubc9 fusion protein and 35S-labeled full-length E2 proteins (Fig. 1). An equal amount of 35S-labeled protein was incubated with GST alone or GST-Ubc9 fusion protein bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads. After washing, the 35S-labeled protein bound to the beads was extracted and analyzed by autoradiography. HPV18 E2 associated with GST-Ubc9 in a dose-dependent manner, but did not interact with GST alone (Fig. 1A). In addition, BPV1 E2, HPV11 E2, and HPV16 E2 were efficiently pulled-down only by GST-Ubc9 (Fig. 1B). Between 13 and 19% of the input E2 was retained on the beads, indicating an effective E2-Ubc9 interaction and consistent with the various E2 proteins being potential targets for sumoylation.

TABLE 1.

Prediction and conserve of sumoylation residues in papillomavirus E2

| Residue | Sumo Probability | |

|---|---|---|

| BPV1 | K111 | 0.68 |

| HPV6 | K111/K112 | 0.31 |

| HPV11 | K111/K112 | 0.31 |

| HPV16 | K111/K112 | 0.31 |

| HPV18 | K115 | 0.68 |

| HPV31 | K111/K112 | 0.31 |

| BPV1 (Didn’t Get Alignment) | K322 | 0.73 |

| HPV6 | K298 | 0.56 |

| HPV11 | K297 | 0.56 |

| HPV16 | K299 | - |

| HPV18 | K300 | - |

| HPV31 | K306 | - |

| HPV16 | K292 | 0.91 |

| HPV18 | K293 | 0.91 |

| HPV31 | K299 | 0.91 |

| HPV6 | K351 | 0.82 |

| HPV11 | K350 | 0.82 |

| HPV16 | K351 | 0.82 |

| HPV18 | A at this position | - |

| HPV31 | K358 | 0.82 |

Figure 1.

Binding of BPV1 and HPV E2 proteins to Ubc9 in vitro. (A) Radiolabeled HPV18 E2 proteins were incubated with 2 to 8 μg of GST or GST-Ubc9 proteins bound to glutathione-Sepharose as indicated. Eluted material was analyzed on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (10%), and the bound proteins were visualized by autoradiography. (B) Radiolabeled BPV1 E2, HPV11 E2, or HPV16 E2 proteins were incubated with 8 μg of GST or GST-Ubc9 proteins bound to glutathione-Sepharose. Eluted material was analyzed as in (A). The percentage of input protein bound is indicated below the respective lanes.

E2 proteins are sumoylated in vitro and in E. coli

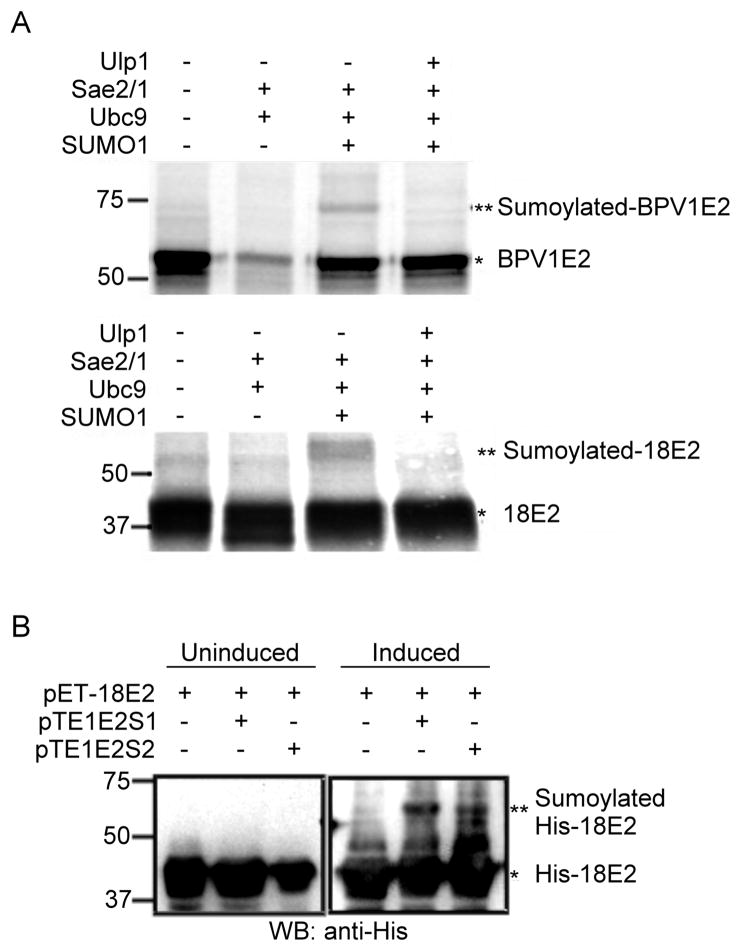

To determine if E2 proteins can serve as a substrate for SUMO modification by Ubc9, an in vitro sumoylation system was applied to BPV1 and HPV18 E2. The E2 proteins were produced by in vitro translation in the presence of [35S]methionine, and then each was used as a substrate in the presence or absence of the purified sumoylation components. After incubation, the E2 proteins were analyzed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and a higher MW form of E2 was observed for both samples when incubated with the complete sumoylation components (Fig. 2A). The new E2 species had a MW increase of ~15 kDa, which is consistent with the addition of a single SUMO moiety. Furthermore, the higher MW forms of both the BPV1 and 18E2 proteins were eliminated by treatment with the yeast protease SUMO protease, Ulp1, which specifically cleaves SUMO but not ubiquitin from proteins (Li and Hochstrasser, 1999). Taken together, these results show that E2 proteins are substrates for in vitro SUMO conjugation.

Figure 2.

In vitro sumoylation of BPV1 and HPV18 E2. (A) In vitro translated and 35S-labeled BPV1 E2 or HPV18 E2 proteins were incubated in the presence of the various combinations of purified sumoylation system proteins as indicated above each lane. For lanes 1 to 3 in both the upper and lower panels, the mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 90 min. For lane 4 in both panels, the mixtures were first incubated at 30°C for 60 min without Ulp1. After the 60 min sumoylation reaction, 1 μg of Ulp1 was added and the reactions were incubated at 30°C for another 30 min. Final reactions were electrophoresed on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (10%) and labeled E2 proteins were visualized by autoradiography. Note that for BPV E2 the addition of SAE1/2 and Ubc9 without SUMO consistently caused a loss of full-length E2 protein. The mechanism for this loss has not been investigated. (B) His-tagged 18E2 encoded by pET-18E2 was introduced into the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain, the pTE1E2S1-BL21(DE3) strain, or the pTE1E2S2-BL21(DE3) strain to form stable transformants. Cultures of each transformant were spilt in half, and one half was adjusted to a final concentration of 0.5 mM of IPTG (Induced) and the other was left untreated (Uninduced). Both the induced and uninduced cultures were further incubated at 23°C for 8 h. After collection of cells, these samples were analyzed by Western blot with anti-His antibodies. For both panels (A) and (B), the single asterisk (*) indicates the unmodified form of either BPV1 E2 or HPV18 E2, and the double asterisk (**) indicates the sumoylated form.

As an alternative to in vitro sumoylation, we also tested HPV18E2 in an E. coli modification/expression system that produces SUMO-conjugated proteins (Uchimura, Nakao, and Saitoh, 2004). A His-tagged HPV18 E2 construct was co-expressed with the pTE1E2S1 or pTE2E2S2 plasmids in E. coli. The pTE1E2S1/S2 plasmids contain a linear fusion of genes for Aos1 and Uba2 (the SUMO activating enzyme subunits), Ubc9, and SUMO1 or SUMO2 linked to an IPTG-inducible T7 promoter (Uchimura et al., 2004). The cultured bacterial lysates expressing 18E2 and/or the SUMO conjugation system were harvested, and the total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-His antibody. Without IPTG induction, only HPV 18E2 was observed in the total cell lysates (Fig. 2B, left panel). However, eight hours after IPTG induction, shifted bands, around ~15 kDa larger than the 42 kDa 18E2 band, were observed in the lysates that contained either pTE1E2S1 or pTE1E2S2, but not in the lysates extracted from cells containing only 18E2 (Fig. 2B, right panel). In addition, cells co-expressing BPV1 E2 and pTE1E2S1or S2 also showed sumoylation of BPV1 E2 in E. coli (data not shown). These results in E. coli are consistent with the in vitro data and indicate that both BPV1 E2 and HPV18 E2 are effective substrates for either SUMO1 or SUMO2.

E2 is modified by SUMO1, SUMO2 and SUMO3 in vivo

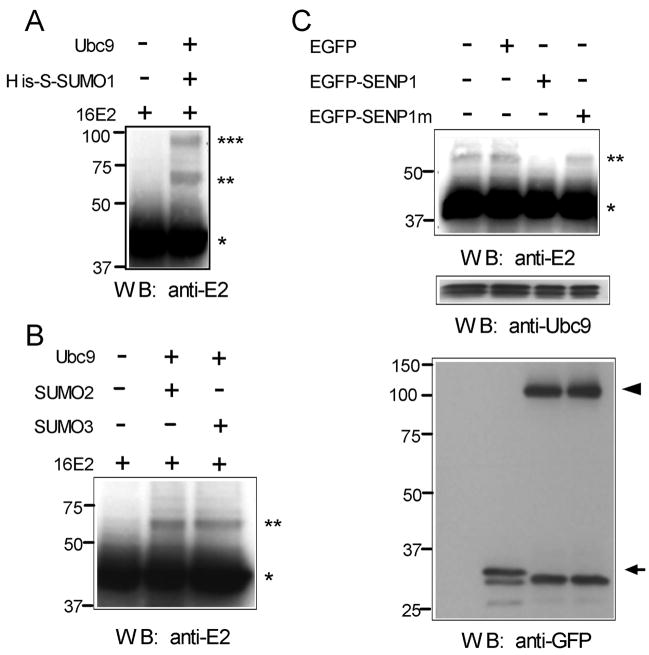

To determine if E2 is also modified by SUMO in vivo, HeLa cells were co-transfected with vectors expressing HPV16 E2, Ubc9, and either SUMO1, 2, or 3. Because HPV E2 proteins are unstable with short half-lives, the calpain protease inhibitor, ALLN, was used to stabilize 16E2 (Penrose and McBride, 2000). Forty-eight hrs after transfection, the transfected cells were directly lysed in SDS-sample buffer to inactivate endogenous SUMO proteases, and the lysates were analyzed by western blotting with anti-16E2 antibody. As shown in Fig. 3A, two new bands were seen above the primary E2 band (~42 kDa) in the presence of the His-S-SUMO1 plasmid. The band with the estimated MW of 64 kDa likely corresponds to 16E2 with a single addition of His-S-SUMO1, while the upper band with the estimated MW of 86 kDa is likely 16E2 carrying two His-S-SUMO1 proteins. This 86 kDa species could be HPV16 E2 sumoylated at 2 different lysines, but we think this possibility is unlikely based on the mutational analysis below (Fig. 4). Alternatively, it is known that the S-tag itself contains a strong potential sumoylation site (Chung et al., 2004) which could result in His-S-SUMO1-E2 being subsequently sumoylated again on the S portion. With either SUMO2 or 3, a single novel band was visible above the primary E2 band (Fig. 3B), and its apparent MW (~60 kDa) was again consistent with monosumoylation of E2. In addition, to further confirm these novel E2 species were SUMO-modified HPV16 E2, a SUMO protease, SENP1, was co-expressed in HeLa cells together with HPV16 E2, Ubc9, and SUMO3. The wild-type SENP1 effectively reduced the amount of the 60 kDa band (Fig. 3C, upper panel) while neither EGFP nor a catalytically inactive SENP1 mutant (SENP1C599A) affected this species (Fig. 3C, upper panel). We conclude from these data that HPV16 E2 is primarily monosumoylated in vivo and can be modified by either SUMO1, 2, or 3.

Figure 3.

Sumoylation of HPV16 E2 by SUMO1, 2, and 3 in vivo. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with either 3 μg of pWEB-16E2 alone or with a combination of 1.5 μg of pcDNA5/FRT/TO/His-S-SUMO1, 1.5 μg of pcDNA5/FRT/TO/HA-Ubc9, and 3 μg of pWEB-16E2. Transfected cells were harvested, extracted, and analyzed by Western blotting as described in Material and Methods. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with either 3 μg of pWEB-16E2 alone or with a combination of 1.5 μg of pcDNA3.1/HA-SUMO2 or SUMO3, 1.5 μg of pcDNA5/FRT/TO/HA-Ubc9, and 3 μg of pWEB-16E2. For both (A) and (B), the parental pcDNA5/FRT/TO vector was used to maintain a constant total DNA amount for all of the samples. Transfected cells were analyzed as in part (A). (C) HeLa cells were transfected with a combination of 3 μg of pWEB-16E2, 1 μg of pcDNA3.1/HA-SUMO3, and 1 μg of pcDNA5/FRT/TO/HA-Ubc9. In each lane, HeLa cells were also transfected with an additional 1 μg of either pcDNA (lane 1), pEGFP, pEGFP-SENP1, or pEGFP-SENP1m (C599A) as indicated. For (A), (B), and (C), cells were treated with ALLN one day post-transfection. Another day after ALLN treatment, total cell lysates were electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and the gels were Western blotted with the antibodies as indicated. The single asterisk (*) indicates the unmodified form of HPV16 E2, the double asterisk (**) indicates the monosumoylated form of HPV16 E2, and the triple asterisk (***) indicates di-sumoylated HPV16 E2. In the lower panel of part (C), EFGP-SENP1 and EFGP-SENP1m are indicated by the arrowhead, and EGFP is indicated by the arrow.

Figure 4.

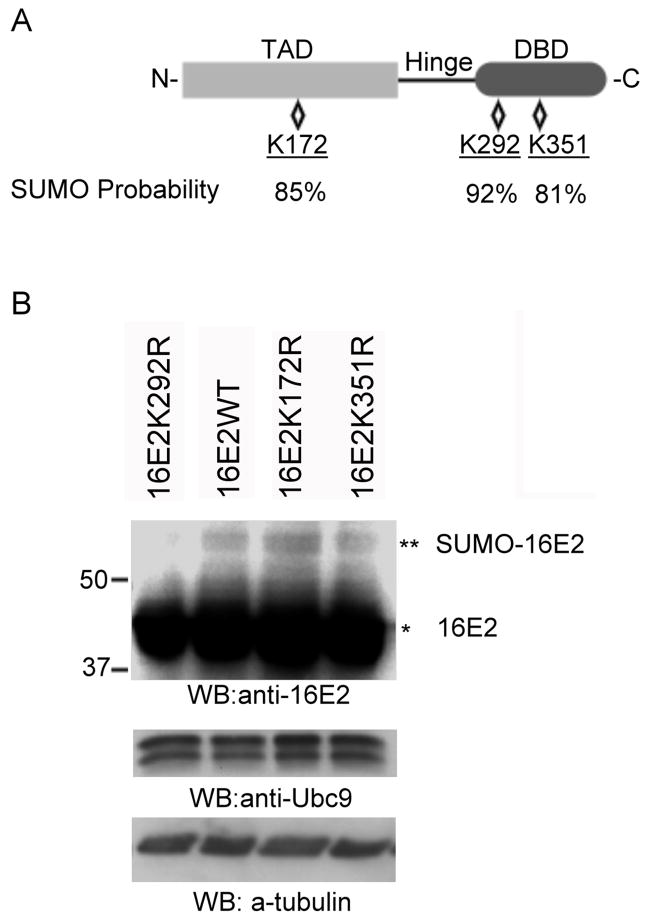

Mapping of the sumoylation site in HPV16 E2. (A) Structure and predicted sumoylation sites in HPV16 E2. The relative locations of the N-terminal transactivation domain (TAD), the hinge region, and the C-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD) are as shown. There are three lysine residues predicted to have a high probability for sumoylation with the probability of the sumoylation indicated below each residue. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with a combination of 1.5 μg of pcDNA3.1/HA-SUMO3 and 1.5 μg of pcDNA5/FRT/TO/HA-Ubc9 together with 3 μg of pWEB-16E2 wildtype (16E2WT, left panel), pWEB-16E2K292R (16E2K292R, left panel), pWEB-16E2K172R (16E2K172R, left panel), pWEB-16E2K351R (16E2K35 1R, left panel), or pWEB-16E2K292RK172R (16E2K292RK172R, right panel). Cells were processed as in Figure 3 and were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-16E2, anti-Ubc9 antibodies, or anti-tubulin (loading control) as indicated. Ubc9 served as the control for comparing transfection and expression efficiency. The single asterisk (*) indicates the unmodified form of either HPV16 E2, and the double asterisk (**) indicates the sumoylated form.

Mapping the E2 sumoylation sites

The studies above indicated that HPV16 E2 was sumoylated at a single predominant site. To identify the amino acid residue of E2 that is modified by SUMO, we generated site-directed mutants of E2 with lysine to arginine substitutions at key residues based on the predicted sumoylation sites in E2 (defined with the SUMOplotTM program, Abgent). HPV16 E2 has three residues with more than 80% probability to be sumoylated: K172, K292, and K351 (Fig. 4A and Table 1). K172 is located in the transactivation domain (TAD) of E2, and K292 and K351 map to the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of E2. To test the ability of these mutant E2 proteins to be sumoylated, HeLa cells were transfected with each of these mutants together with SUMO3 and Ubc9. Under these conditions, all of the mutants were expressed at levels comparable to the wild-type E2 (Fig. 4B, upper panel), but only the K292R mutant of 16E2 lost the ability to be sumoylated while the K172R and K351R mutants did not. Furthermore, of these 3 potential sites, only the K292 position is absolutely conserved as a high probability sumoylation site in all twelve high-risk HPV E2 protein sequences examined (not shown). In contrast, predicted sumoylation sites at K172 or K351 are present in only 7 of 12 and 10 of 12 high-risk E2 proteins, respectively. Based on these results, we believe that K292 is the primary sumoylation target for 16E2, and that it is likely that all the high-risk E2 proteins could be sumoylated at the comparable position.

Transcriptional activity of 16E2 was adversely affected by mutation of the sumoylation site lysine residue

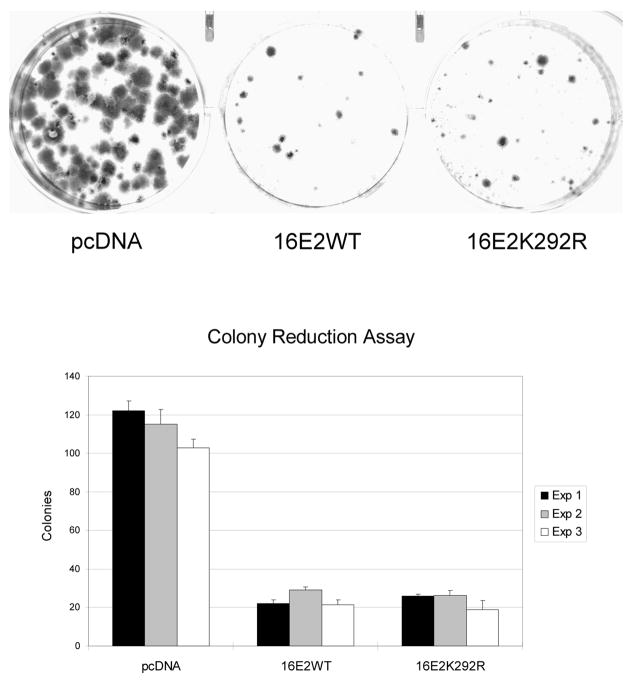

Sumoylation has been described as an important regulator of the transcriptional activity for numerous cellular and viral transcription factors. Typically, transcription factor mutants lacking the sumoylation site show altered transcriptional activity compared to their wild-type counterpart. It is well documented that introducing E2 into HeLa cells causes cellular growth inhibition and reduced colony formation due to E2-dependent transcriptional repression of the HPV18 P105 promoter, which regulates E6 and E7 expression levels (Dowhanick, McBride, and Howley, 1995; Francis, Schmid, and Howley, 2000; Hwang et al., 1993; Thierry and Yaniv, 1987). Consequently, to investigate the effect of sumoylation on E2 transcriptional repression activity, we compared the wildtype E2 protein with the sumoylation-defective K292R mutant E2 protein in the HeLa colony formation assay. In this assay, both 16E2WT and 16E2K292R markedly inhibited colony formation to an identical level (Fig. 5). Furthermore, compared to the large and numerous neomycin-resistant colonies formed in the absence 16E2, wild-type and the K292R mutant 16E2 not only reduced the number of colonies formed, but also decreased the size of these colonies. Thus, 16E2K292R could not be distinguished from wild-type E2 in this long-term assay.

Figure 5.

HeLa cell colony reduction assay. For this assay, 6 × 105 HeLa cells were transfected with 0.5 g of neomycin resistant plasmid (pcDNA3.1) together with 3 μg of plasmids expressing pcDNA5, 16E2WT, or 16E2K292R. Cells were split 1:3 and grown under G418 selection for 3 weeks. After fixing and staining the cells, the number of colonies was counted and averaged from the three plates for each sample. The upper panel shows one representative plate from one of the three independent experiments. The graph in lower panel shows the average number of colonies from all three experiments.

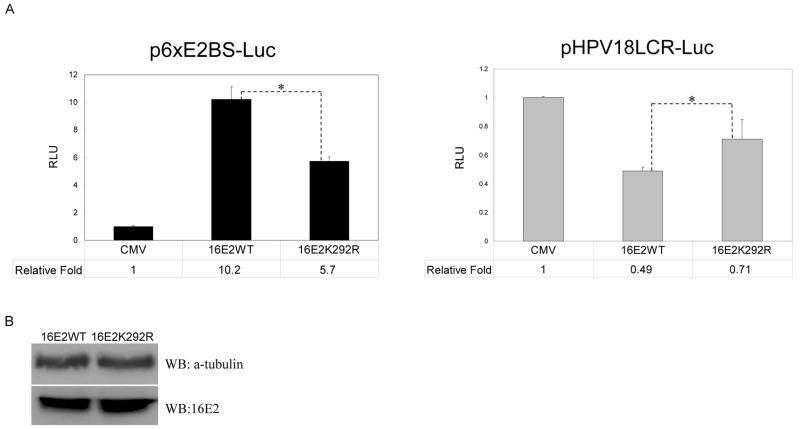

As an alternative to the HeLa assay, the activities of 16E2WT and 16E2K292R were compared in short-term transient reporter assays. To investigate the contribution of sumoylation to E2 transactivation activity, we examined the activity of wild-type and K292R HPV16 E2 in C33A cells using an E2-activated reporter vector (p6xE2BS-Luc) with 6 E2 binding sites. The ability of 16E2WT to transactivate this 6xE2BS-Luc reporter vector was 10.2-fold over basal level, but the transactivational ability of 16E2K292R was reduced to only 5.7-fold over basal level (Fig. 6A, left panel). This 44% reduction in activity for the E2K292R mutant was statistically significant. For the effect of sumoylation on the transcriptional repression ability of E2, we also tested the response of both 16E2WT and 16E2K292R in C33A cells using pHPV18LCR-Luc, an HPV18P105 promoter-driven luciferase plasmid (Schweiger et al., 2007). 16E2WT reduced activity of the p105 promoter by 50%, while 16E2K292R reduced this activity only by 30% (Fig. 6A, right panel), which was again statistically significant. Western blot analysis (Fig. 6B) demonstrated that the level of 16E2K292R was equal to that of 16E2WT under these conditions, indicating that the reduced transcriptional activity of 16E2K292R on both promoters was not due to differences in protein expression.

Figure 6.

The sumoylation defective mutant of HPV16 E2 shows reduced transcriptional activity. (A) Left panel, C33A cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of p6xE2BS-Luc and 0.3 μg of pSV-β-Gal together with 0.55 μg of either 16E2WT, 16E2K292R, or empty parental vector (CMV). pcDNA was used to adjust the total DNA to 2.4 μg. Right panel, C33A cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of HPV18LCR-Luc and 0.1 μg of pSV-β-Gal together with 5 μg of either 16E2WT, 16E2K292R, or empty parental vector (CMV). Luciferase and β-gal assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods, and the data represent the average number from three independent experiments. The difference in transcriptional activity (*) was significant with a p-value < 0.005. (B) Expression of 16E2WT or 16E2K292R in the extracts from part (A) was detected by Western blotting with an anti-16E2 antibody.

The K292R mutation does not affect E2 DNA binding or localization

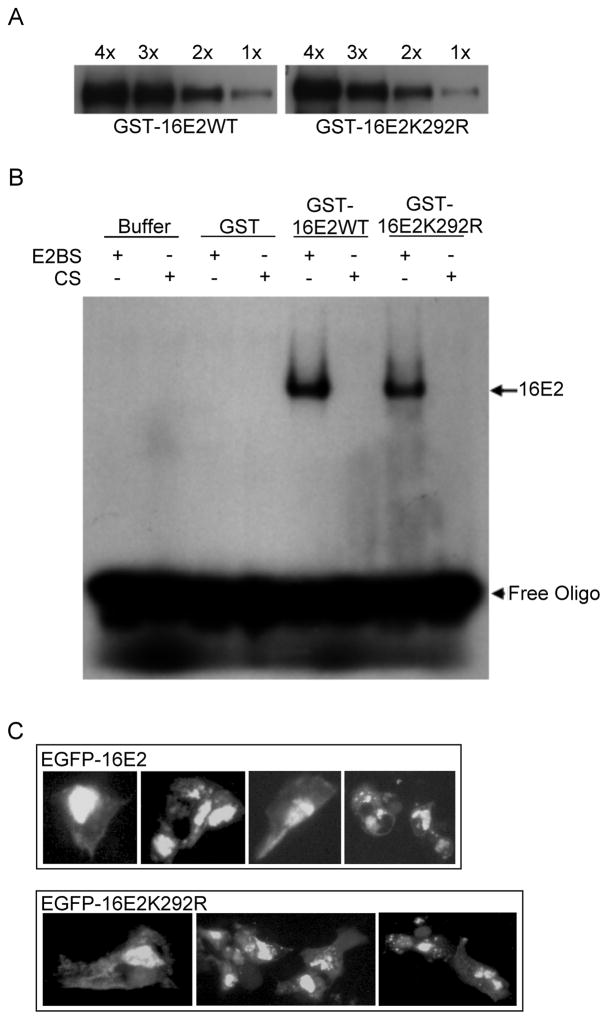

Due to the location of K292 in the DBD of HPV16 E2, it was possible that the K292R mutation affected DNA binding by the mutant protein, and that a defect in this function accounted for the reduced transcriptional activity. Based on the three-dimensional structure of 16E2, K292 is directly involved neither in DNA contact nor in dimerization (Hegde and Androphy, 1998), but mutation of this residue still might have subtle effects on structure that resulted in reduced DNA interaction capacity. To confirm that the K292R mutation did not impede the binding of 16E2 to the E2-specific sequence (E2BS), we performed an EMSA using GST, GST-16E2WT, and GST-16E2K292R. The amount of purified GST-16E2WT and GST-16E2K292R used in EMSA was first measured by Western blot of serially diluted samples (Fig. 7A), and then 1x of both purified E2 proteins was used to carry out the gel mobility shift assay (Fig. 7B). When adjusted for protein levels, 16E2WT and 16E2K292R possessed equal ability to bind to the E2BS oligo, and no E2 binding was detected for the control oligo. The absence of retarded bands with the GST sample indicated that the binding with GST-E2 was due to the 16E2 proteins and not the GST moiety. Further titration over a range of E2 concentrations showed no significant difference between wild type and mutant E2 protein (not shown). From these results we conclude that the K292R mutation is unlikely to negatively affect the dimerization or the DNA binding ability of 16E2. Whether or not sumoylation of E2 alters its DNA binding properties has not yet been determined.

Figure 7.

DNA-binding ability and intracellular localization of HPV16 E2. (A) The amount of purified GST-16E2WT (left panel) and GST-16E2K292R (right panel) used in the EMSA was quantitated by Western blot of serially diluted E2 samples. (B) The electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Briefly, 50 ng of each protein (GST, GST016E2WT, and GST16E2K292R) was assayed with 5 fmol of either the 32P-labeled E2 binding site oligonucleotide (E2BS) or a 32P-labeled control oligonucleotide (CS) lacking an E2BS. The Buffer lanes had no protein added. The free oligonucleotides are indicated with the arrowhead and the 16E2-bound DNA is indicated with the arrow. (C) Fluorescent images showing the localization of wildtype (an upper panel) and K292R mutant (a lower panel) EGFP-16E2 proteins in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with either EGFP-16E2WT or EGFP-16E2K292R, and the E2 proteins were visualized by fluorescent microscopy at 48 h post-transfection.

Sumoylation is also known to affect cellular localization of target proteins (Wilson and Rangasamy, 2001), and lysine 292 is just upstream of the nuclear localization sequence of HPV16 E2 (Klucevsek et al., 2007). Hence, it was important to determine if the subcellular localization of 16E2 was influenced by the K292R mutation which could result in differences in transcriptional activities. We performed fluorescent microscopy of both 16E2WT and 16E2K292R in HeLa cells (Fig. 7C). The pattern of the EGFP-16E2WT (Fig. 7C, upper panel) mirrored that of the lysine 292 to arginine mutant (Fig. 7C, lower panel). Both WT and K292R mutant E2 proteins were predominantly nuclear and partly cytoplasmic, and there was no apparent difference in the distribution of these two types of 16E2 protein. Thus, since mutation of the sumoylation target site does not influence the subcellular localization of HPV16 E2, it appears that sumoylation is not required for nuclear entry of E2. Furthermore, since the K292R mutation does not appear to influence the DNA binding activity or subcellular localization of 16E2, the most likely explanation for the reduced transcriptional activity of the K292R mutant is that sumoylation has a modest regulatory role in E2 transcriptional activity.

Discussion

The life cycle of papillomaviruses is closely linked to the differentiation process of epithelial keratinocytes (Longworth and Laimins, 2004). One of the critical early viral proteins is the multifunctional E2 protein which acts as a replication initiation factor (Demeret et al., 1995; Ferguson and Botchan, 1996; Sakai et al., 1996), has a genome segregation function (Bastien and McBride, 2000; Voitenleitner and Botchan, 2002; You et al., 2004), and is a transcriptional regulatory protein (Hirochika et al., 1988; Phelps and Howley, 1987; Spalholz, Yang, and Howley, 1985; Stenlund and Botchan, 1990; Tan et al., 1994). Recently we showed that sumoylation, a post-translational modification that often regulates cellular transcription factor activity (Verger, Perdomo, and Crossley, 2003), was upregulated during keratinocyte differentiation (Deyrieux et al., 2007). This observation raised the possibility that E2 proteins might also be regulated by sumoylation during keratinocyte differentiation. Using an in vitro GST pull-down assay, we confirmed that Ubc9, the SUMO conjugating enzyme, specifically interacts with BPV1 and HPV E2 proteins. We further demonstrated that E2 proteins not only bind to Ubc9, but are also substrates for sumoylation in vitro and in vivo. The sumoylation of E2 appears to be through an authentic isopeptide linkage as the SUMO moiety could be removed by the SUMO-specific proteases, Ulp1 (in vitro) or SENP1 (in vivo). Sumoylation of 16E2 was observed in vivo with SUMO1, SUMO2, or SUMO3, with no apparent difference in efficiency under these over-expression conditions. The precise differences between SUMO1 and the SUMO2/3 family in regulating the functions of target proteins are unknown, however, some cellular proteins are preferentially sumoylated with SUMO1 versus SUMO2/3 while others appear to be modifiable by either SUMO family (Rosas-Acosta et al., 2005). In keratinocytes we observed that it is primarily expression of the SUMO2/3 family that increases during keratinocyte differentiation (Deyrieux et al., 2007), suggesting that SUMO2/3 modification of E2 proteins may actually be the biological event.

One of the technical challenges for sumoylation studies is the typically low level of a sumoylated protein compared to its unmodified form. For most known sumoylated proteins, sumoylation can be detected in vivo only after over-expression of SUMO or of SUMO plus Ubc9, and this was true for E2 as well, as no sumoylated forms were detected in the absence of over expression of the sumoylation components. In addition, we found that adequate detection of the sumoylated E2 species required treatment of the cells with a proteasome inhibitor. It is well established that E2 proteins have short half-lives, and for BPV1 E2 the PEST sequence targets it for proteasomal degradation (Penrose and McBride, 2000). Likewise, HPV18 E2 has been shown to undergo proteasomal degradation (Bellanger et al., 2001), and this is likely a general feature of E2 proteins. Several proteasome inhibitors have been shown to stabilize E2 proteins (Bellanger et al., 2001; Penrose and McBride, 2000), and we found that ALLN treatment dramatically increased the level of E2 protein after transient transfection (not shown). Only when the E2 levels were enhanced with ALLN was there sufficient signal for detecting the sumoylated form of E2. This requirement for both exogenous expression of the sumoylation components and stabilization of E2 with a proteasomal inhibitor probably accounts for the failure of sumoylated E2 to be observed previously. While these conditions may seem extreme and could raise doubts about the biological significance of E2 sumoylation, these conditions are not in fact significantly different from those used in many sumoylation studies. Furthermore, while many sumoylated cellular transcription factors have only a small fraction of their total protein in the sumoylated form, even under over-expression conditions, mutation of sumoylation sites usually demonstrates a measurable effect on function. Similarly, mutation of the SUMO addition site in 16E2 resulted in a significant decrease in transcriptional activity on two types of promoters (Fig. 6 and discussed further below), supporting the likelihood of endogenous and functional sumoylation at this site.

Our mutational analysis of HPV 16 E2 identified lysine 292 in HPV16 E2 as the predominant site of sumoylation. The two other highly predicted sumoylation sites in 16E2, lysines 172 and 351, were tested, and neither of them appeared to be a target for sumoylation. However, we are unable to exclude the possibility of minor modification by SUMO at these two lysines or other sites on E2 which might be below detectable limits by western blot and yet could have functional consequences. It should be noted, however, that a lysine within a potential sumoylation motif is conserved in the position homologous to HPV 16E2 residue 292 in all high-risk E2 proteins, while there is not complete conservation of the predicted sumoylation sites at residues 172 and 351 (not shown). The complete conservation of the 292 sumoylation site suggests that sumoylation at lysine 292 may be a critical regulatory modification for all E2 proteins in this group. In contrast, the low-risk HPV E2 proteins also have predicted sumoylation sites, though not always at the lysine 292 equivalent. Thus, sumoylation of K292 may play a unique role in regulation of high risk E2 functions.

Sumoylation is well known to modulate the activity of numerous transcription factors, so its effects on E2 transactivation were investigated. We found that the K292R mutant, which was not sumoylated, had reduced transactivation activity compared to wild-type 16E2. Since this mutant was not deficient in expression, specific DNA binding, or in subcellular localization, we conclude that the reduced transcriptional activity of 16E2 K292R is most likely caused by its inability to be sumoylated; these results indicate that the transactivation activity of E2 is enhanced by sumoylation. While sumoylation has commonly been shown to reduce transactivational activity (Gill, 2005), there are several well-characterized examples of enhanced transcriptional activity by sumoylation, including Oct4 (Wei, Scholer, and Atchison, 2007), HSF1 (Hong et al., 2001), and HSF2 (Goodson et al., 2001), though the mechanism of activation remains undefined. The transactivational activity of E2 proteins has been shown to be mediated by the cellular Brd4 protein (Ilves et al., 2006; McPhillips et al., 2006; Schweiger et al., 2007; Schweiger, You, and Howley, 2006; Senechal et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2006). Blocking the binding of E2 to Brd4 or knockdown of Brd4 expression by hairpin RNA, both inhibit E2-dependent transcriptional activation. Interestingly, Brd4 displays multiple predicted sites for sumoylation as well as potential SUMO binding motifs (data not shown), raising the possibility that sumoylation of E2 could enhance recruitment of Brd4 which would promote increased transcriptional activity of E2. This potential effect through Brd4 as a mean by which sumoylation stimulates the transcriptional activation of E2 proteins will be investigated.

In addition to its transactivation activity, HPV E2 proteins act as transcriptional repressors of the early promoter and thereby down-regulate E6/E7 expression (Bernard et al., 1989; Steger and Corbach, 1997; Thierry and Yaniv, 1987). Our studies indicated that the K292R mutant showed reduced repressive activity in a transient reporter assay compared to wild-type E2 (Fig 6A, right panel). While a similar defect could not be demonstrated in the HeLa cell colony formation assay, this could be due to the integrated state of the HPV18 LCR in these cells compared to the episomal state of the LCR in the transient reporter assay. Alternatively, the long-term colony assay may simply be too insensitive to discriminate between relatively small differences in E2 activity.

Two mechanisms have been proposed to explain SUMO-dependent repression, sequestration of sumoylated transcription factors into repressive nuclear subdomains (Ross et al., 2002) and recruitment of co-repressors (Girdwood et al., 2003; Yang and Sharrocks, 2004). We did not observe any gross changes in subcellular localization between the wild-type 16E2 and the K292R mutant form that could not be sumoylated, but more detailed studies will be required to assess possible subtle effects of sumoylation on E2 localization within the nucleus. Effects of sumoylation on E2 interactions with other factors have not yet been investigated, but seem likely. E2 has numerous interaction partners, including a variety of transcription factors which can be classified as basal/remodeling factors or specific transactivators. TFIIB (Benson, Lawande, and Howley, 1997; Rank and Lambert, 1995; Yao, Breiding, and Androphy, 1998), TBP (Ham, Steger, and Yaniv, 1994; Steger et al., 1995), AMF-1 (Breiding et al., 1997; Peng et al., 2000), p/CAF (Lee et al., 2002), and p300/CBP (Lee et al., 2000; Muller, Ritzkowsky, and Steger, 2002) are all basal/remodeling factors with known E2-association. It will be important to determine whether the sumoylation of E2 protein impacts recruitment or binding to these factors, resulting in functional changes in chromatin structure and/or transcription. Additionally, E2 also binds to specific transactivators, such as CEF (Lewis et al., 1999), C/EBP (Hadaschik et al., 2003), Sp1 (Li et al., 1991; Tan, Gloss, and Bernard, 1992), and YY1 (Lee, Broker, and Chow, 1998) which are all involved in regulating either viral or cellular gene expression. Whether or not the sumoylation of E2 influences these interactions and transcription from specific promoters is also unknown.

Lastly, tight regulation of E2 function during keratinocyte differentiation is likely essential for normal progression through the viral life cycle. As mentioned above, differentiation-dependent increases in SUMO2/3 expression and in overall sumoylation have been observed in monolayer keratinocyte culture (Deyrieux et al., 2007), and such changes could increase the ratio of sumoylated to unsumoylated E2 and modulate E2 transcriptional activity. Thorough understanding of the contribution of sumoylation to regulation of E2 transcriptional activity should provide new insight into viral reproduction, papillomavirus pathogenesis, and the host-viral interplay. In addition, the discovery of sumoylated E2 offers a potential new target for development of antiviral agents as prevention of sumoylation might disrupt the viral vegetative cycle.

Material and methods

Plasmids

Plasmids utilized in this study were generously provided by the following: pET-18E2, Dr. F. Thierry; pSG5/HA-11E2 and pSG5/HA-16E2, Dr. S.M. Huang; pTE1E2S1 and pTE1E2S2, Dr. H. Saitoh; pWEB-16E2 and pGEX-16E2, Dr. K. Gaston; p6xE2BS-Luc, Dr. F. Stubenrauch; pHPV18LCR-Luc, Dr. P. Howley; pEGFP-SENP1WT and pEGFP-SENP1C599A, Dr. T. Nishida; pcDNA3.1/HA-SUMO2, pcDNA3.1/HA-SUMO3, and the GST-SAE1/SAE2 expression plasmid, Dr. Ronald T. Hay. The pRSET-BPV1 E2 plasmid (Leng, Ludes-Meyers, and Wilson, 1997), the pRSET-SUMO1 plasmid (Rosas-Acosta et al., 2005), and the pcDNA5/FRT/TO/His-S-SUMO1 and pcDNA5/FRT/TO/HA-Ubc9 plasmids (Rosas-Acosta et al., 2005) have all been described previously.

Mutagenesis

All mutants were all constructed with the QuickChange polymerase chain reaction-based mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The pEGFP-16E2K292R, pGEX-16E2K292R, and pWEB-16E2K292R mutants were developed using the primers set: 5′-C T A C A C C C A T A G T A C A T T T A C G A G G T G A T G C T A A T A C - 3 ′/5′-GTATTAGCATCACCTCGTAAATGTACTATGGGTGTAG-3′. The pWEB-16E2K172R and pWEB-16E2K351R mutants were constructed using the primers 5′-GGAATACGAACATATTTTGTGCAGTTTCGAGATGATGCAG-3′/5′-CTGCATCATCTCGAAACTGCACAAAATATGTTCGTATTCC-3′ and 5′-GGCAACGTGACCAATTTTTGTCTCAAGTTCGCATACCAAAAAC-3′/5′-GTTTTTGGTATGCGAACTTGAGACAAAAATTGGTACCGTTGCC-3′, respectively. The underlined sequences indicate the mutant codon. All the mutants were confirmed by sequencing.

GST fusion protein expression

GST and GST-Ubc9 were expressed using the pGEX-5X-1-based expression plasmids as previously described (Rangasamy and Wilson, 2000). GST or GST-Ubc9 were transformed into the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain while GST-16E2 and GST-16E2K292R were transformed into Rosetta2 strain. Twelve ml of overnight cultures were inoculated into 500 ml of 2XYT broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin and incubated at 37°C until reaching an OD600 = 0.6 to 0.8, followed by induction at 28°C for 4 h with a final concentration of 0.5 mM isopropylthiogalactoside (IPTG). After collection, the cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.3, 5 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 15 mg lysozyme). The lysate was kept on ice for 30 min followed by sonication four times for 10 sec at 36 watts. Triton X-100 was then added to the lysates to a final concentration of 1%, and the lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min. Then, the supernatant was incubated with 600 l of glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) at 4°C for 2 h. The glutathione-Sepharose beads were washed four times with phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.3. Purified proteins were eluted with elution buffer (20 mM L-reduced glutathione [Sigma], 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 120 mM NaCl). The proteins were then supplemented with glycerol to a final concentration of 10% and stored at −70°C. The quantification of proteins was performed using the Bradford assay.

In vitro Ubc9 binding assay

The BPV1 E2, HPV11 E2, HPV16 E2, and HPV18 E2 proteins were expressed from the pRSET-BPV1E2, pSG5/HA-11E2, pSG5/HA-16E2, and pET-18E2 plasmids, respectively, using the T7-coupled rabbit reticulocyte lysate system in the presence of [35S] methionine according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). For the GST pull-down assay, 2 to 8 μg of GST alone or GST-Ubc9 fusion proteins were pre-incubated with 26.7 μl of glutathione-Sepharose beads with agitation for 1 h at room temperature in 0.5 ml of binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Tween 20, 0.5% bovine serum albumin). Three μl of 35S-labeled protein were then added to the beads, and incubation was continued for another 2 h. The beads were washed twice with binding buffer and another three times with wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Tween 20) supplemented with 200 mM NaCl, 300 mM NaCl, and 150 mM NaCl, respectively. Labeled protein bound on the beads was recovered by heating at 95°C in 6 μl of SDS-sample buffer (150 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 12% SDS, 30% glycerol) and was analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Radiolabeled bands were visualized by autoradiography, and the results were quantitated by densitometry

In vitro sumoylation assay

All sumoylation components were expressed and purified as described previously (Rosas-Acosta et al., 2005). Briefly, SAE2 and SAE1 were co-expressed and co-purified by using thrombin digestion to release the bound enzyme from glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads; Ubc9 was similarly purified using elution by Factor Xa digestion. His-SUMO1 was purified through Ni2+-NTA-Agarose resin (QIAGEN). In vitro sumoylation assays were carried out by incubating the substrate proteins (2 μl of 35S-labeled in vitro translated E2 proteins), with or without 1.5 μg of SAE2/SAE1, 0.5 μg of Ubc9, and 4 μg of SUMO1. All the reactions were performed for 90 min at 30°C in a final buffer volume of 25 μl containing 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP, and 0.5 mM DTT. Nine μl of SDS-sample buffer were added to each sample to stop the reaction, and then the samples were incubated at 95°C for 7 min. These samples were analyzed on an SDS-PAGE gel, and processed as described for the in vitro binding experiments.

Escherichia coli SUMO modification/expression system

pTE1E2S1 or pTE1E2S2 were introduced into the BL21(DE3) strain, and single colonies of each were used to generate the pTE1E2S1 or pTE1S2 competent cells. The pET-18E2 or pRSET-BPV1E2 plasmids, which encode the substrate proteins, were then transformed into these pTE1E2S1/S2 competent cells by heat shock. A single colony was selected and transferred to 12 ml of Luria Bertani (LB) media containing 50 μg/ml of chloramphenicol and 100 μg/ml of ampicillin. Bacterial cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking until reaching an OD600 = 1.0, and then IPTG was added to the culture to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. After incubation for 8 h at 23°C, 1 ml of the bacterial culture was collected by centrifugation and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of TE (10mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1mM EDTA, pH 8.0) buffer. The resuspended cells were lysed by addition of 100 μl of SDS-sample buffer. After passage through a 26-gauge syringe, the samples were denatured at 95°C for 7 min. Twenty l of each sample were analyzed by Western blotting.

Cell culture, transfection, and luciferase assay

HeLa cells were maintained and grown in Dulbecco MEM (DMEM) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 44 mM of sodium bicarbonate. C33A cells were maintained and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 17.9 mM of sodium bicarbonate. Both cell lines were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. For HeLa cell transfections, 6 × 105 cells were plated in 6-well plates the day before transfection. The transfections were performed using a total of 6 μg of DNA and 6 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the supplier’s recommendations. Two days after transfection, the HeLa cells were collected by addition of 500 μl of boiling SDS-sample buffer. These samples were passed through a 26-gauge syringe and denatured at 95°C for 7 min. Then, 30 μl of each sample were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis. For the Luciferase assay, 1.2 × 106 C33A cells were plated in 12-well plates the day before transfection. The p6xE2BS-Luc or pHPV18LCR-Luc plasmids were co-transfected with the pSV-β-Galactosidase control vector (Promega) and the E2 plasmids (wildtype or K292R mutant) using Lipofectamine 2000. C33A cells were collected two days after transfection using 200 μl of Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega), and the Luciferase assay was performed using the Luciferase Assay System according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). The β-galactosidase assay was performed with ONPG as the substrate and was read at OD420. Luciferase activity was measured as luminescence using a Tecan Infinite M200 plate reader, and the luciferase values were normalized using the β-galactosidase activity. The transcriptional activities of the wildtype and mutant E2 proteins were compared using the Student’s t test.

Western blot

Western blotting was performed according to standard procedures using the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-His (1:10000, Santa Cruz), mouse anti-HPV16 E2 (1:1000, Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-Ubc9 serum [1:1000, (Deyrieux et al., 2007)], and mouse anti-GFP (1:5000, Santa Cruz). Briefly, the protein samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and were then transferred to Millipore 0.45 μm Immobilon-P membranes. After transfer, the membrane was blocked in TTBS (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.05% Tween 20) with 5% non-fat milk for 30 min. The membrane was then incubated with the indicated primary antibodies and the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz). The membranes were treated with the Western Lightning Chemiluminescence reagent (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences) or Immobilon Western reagent (Millipore) and exposed to X-ray film.

Electromobility shift assays (EMSAs)

Gel shift assays were performed as described previously (Gonzalez et al., 2000). Briefly, 2 to 5 fmol of radiolabelled oligonucleotide and 20 ng pUC18 DNA were incubated with 50 ng of purified GST, GST-16E2, or GST-16E2K292R in 10 μl of EMSA reaction buffer (20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 5 mM DTT, 0.07% BSA). Oligonucleotides E2BSU (5 ′-C G G T A C G G G A A C C G C A C C C G G T A C - 3 ′) a n d E 2 B S L (5′-CGGTACGTACCGGGTGCGGTTCCC-3′) were annealed to form a double-stranded DNA containing a consensus papillomavirus E2 binding site. Oligonucleotides CU (5 ′-C G G T A C G G G A C T G C C C G C G A A C A C - 3 ′) a n d C L (5′-CGGGACGTGTTCGCGGGCAGTCCC-3′) were annealed to form a control. Doable stranded DNA with a similar GC content, but without an E2 binding sites. Both annealed oligonucleotides were radiolabeled as previously described (Gonzalez et al., 2000). Purified GST-E2 protein samples were incubated with the radiolabeled oligonucleotides for 30 min at 25°C and were then electrophoresed on 8% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in 0.5x Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer (pH 7.5). Protein quantification was carried out using densitometry after Western blotting of serially diluted samples.

Fluorescence microscopy

HeLa cells were cultured in 6-well plates with 6 × 105 cell per well. Six g of EGFP-16E2WT or EGFP-16E2K292R DNA were used to transfect the HeLa cells using Lipofectamine 2000. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were washed with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. After mounting the cells with toluene, cells were visualized by fluorescent microscopy using an Olympus LX70 microscope, and the images were captured digitally using a Qcolor3 camera (Olympus).

Colony reduction assay

HeLa cells were cultured in 6-well plates with 6 ×105 cell per well. The cells were co-transfected with a neomycin plasmid together with either pcDNA5, pWEB-16E2WT, or pWEB-16E2K292R. At 24 h after transfection, cells were split and cultured in triplicate and were maintained for 3 weeks in growth medium supplemented with G418 (900 μg/ml). At 3 weeks, the cultures were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with methanol, and stained with methylene blue. The total number of neomycin-resistant colonies was counted and averaged.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. German Rosas-Acosta for kind assistance with the in vitro sumoylation reaction and for supplying purified Ulp1. This work was supported by grant CA89298 from the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bastien N, McBride AA. Interaction of the papillomavirus E2 protein with mitotic chromosomes. Virology. 2000;270(1):124–134. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter MK, McPhillips MG, Ozato K, McBride AA. The mitotic chromosome binding activity of the papillomavirus E2 protein correlates with interaction with the cellular chromosomal protein, Brd4. J Virol. 2005;79(8):4806–4818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4806-4818.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellanger S, Demeret C, Goyat S, Thierry F. Stability of the human papillomavirus type 18 E2 protein is regulated by a proteasome degradation pathway through its amino-terminal transactivation domain. J Virol. 2001;75(16):7244–7251. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7244-7251.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson JD, Lawande R, Howley PM. Conserved Interaction of the Papillomavirus E2 Transcriptional Activator Proteins with Human and Yeast TFIIB Proteins. J Virol. 1997;71(10):8041–8047. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.8041-8047.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard BA, Bailly C, Lenoir MC, Darmon M, Thierry F, Yaniv M. The human papillomavirus type 18 (HPV18) E2 gene product is a repressor of the HPV18 regulatory region in human keratinocytes. J Virol. 1989;63:4317–4324. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4317-4324.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding DE, Sverdrup F, Grossel MJ, Moscufo N, Boonchai W, Androphy EJ. Functional interaction of a novel cellular protein with the papillomavirus e2 transactivation domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(12):7208–7219. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LK, Lee YH, Cheng TS, Hong YR, Lu PJ, Wang JJ, Wang WH, Kuo CW, Li SSL, Liu ST. Post-translational modification of Rta of Epstein-Barr virus by SUMO-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(37):38803–38812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang CM, Dong G, Broker TR, Chow LT. Control of human papillomavirus type 11 origin of replication by the E2 family of transcription regulatory proteins. J Virol. 1992;66(9):5224–5231. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5224-5231.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung TL, Hsiao HH, Yeh YY, Shia HL, Chen YL, Liang PH, Wang AHJ, Khoo KH, Li SSL. In vitro modification of human centromere protein CENP-C fragments by small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protein Definitive identification of the modification sites by tandem mass spectrometry analysis of the isopeptides. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(38):39653–39662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeret C, Desaintes C, Yaniv M, Thierry F. Different mechanisms contribute to the E2-mediated transcriptional repression of human papillomavirus type 18 viral oncogenes. J Viro. 1997;71(12):9343–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9343-9349.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeret C, Lemoal M, Yaniv M, Thierry F. Control of HPV 18 DNA replication by cellular and viral transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(23):4777–4784. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.23.4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desterro JMP, Rodriguez MS, Kemp GD, Hay RT. Identification of the enzyme required for activation of the small ubiquitin-like protein SUMO-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(15):10618–10624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyrieux AF, Rosas-Acosta G, Ozbun MA, Wilson VG. Sumoylation dynamics during keratinocyte differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 1):125–36. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen RJ. SUMO protein modification. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695(1–3):113–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowhanick JJ, McBride AA, Howley PM. Suppression of cellular proliferation by the papillomavirus E2 protein. J Virol. 1995;69(12):7791–7799. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7791-7799.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson MK, Botchan MR. Genetic analysis of the activation domain of bovine papillomavirus protein E2 - its role in transcription and replication. J Virol. 1996;70(7):4193–4199. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4193-4199.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DA, Schmid SI, Howley PM. Repression of the integrated papillomavirus E6/E7 promoter is required for growth suppression of cervical cancer cells. J Virol. 2000;74(6):2679–2686. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2679-2686.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill G. Something about SUMO inhibits transcription. Curr Opin Genet Develop. 2005;15(5):536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdwood D, Bumpass D, Vaughan OA, Thain A, Anderson LA, Snowden AW, Garcia-Wilson E, Perkins ND, Hay RT. p300 transcriptional repression is mediated by SUMO modification. Mol Cell. 2003;11(4):1043–1054. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Bazaldua-Hernandez C, West M, Woytek K, Wilson VG. Identification of a short, hydrophilic amino acid sequence critical for origin recognition by the bovine papillomavirus E1 protein. J Virol. 2000;74:245–253. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.245-253.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson ML, Hong Y, Rogers R, Matunis MJ, Park-Sarge OK, Sarge KD. SUMO-1 modification regulates the DNA binding activity of heat shock transcription factor 2, a promyelocytic leukemia nuclear body associated transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(21):18513–18518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadaschik D, Hinterkeuser K, Oldak M, Pfister HJ, Smola-Hess S. The papillomavirus E2 protein binds to and synergizes with C/EBP factors involved in keratinocyte differentiation. J Virol. 2003;77(9):5253–5265. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5253-5265.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham J, Steger G, Yaniv M. Cooperativity in vivo between the E2 transactivator and the TATA box binding protein depends on core promoter structure. EMBO J. 1994;13(1):147–157. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay RT. SUMO: A history of modification. Mol Cell. 2005;18(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde RS, Androphy EJ. Crystal structure of the E2 DNA-binding domain from human papillomavirus type 16: Implications for its DNA binding-site selection mechanism. J Mol Biol. 1998;284(5):1479–1489. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika H, Hirochika R, Broker TR, Chow LT. Functional mapping of the human papillomavirus type 11 transcriptional enhancer and its interaction with the trans-acting E2 proteins. Genes Dev. 1988;2(1):54–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong YL, Rogers R, Matunis MJ, Mayhew CN, Goodson M, Park-Sarge OK, Sarge KD. Regulation of heat shock transcription factor 1 by stress-induced SUMO-1 modification. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(43):40263–40267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang ES, Riese DJ, Settleman J, Nilson LA, Honig J, Flynn S, DiMaio D. Inhibition of cervical carcinoma cell line proliferation by the introduction of a bovine papillomavirus regulatory gene. J Virol. 1993;67(7):3720–3729. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3720-3729.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilves I, Maemets K, Silla T, Janikson K, Ustav M. Brd4 is involved in multiple processes of the bovine papillomavirus type 1 life cycle. J Virol. 2006;80(7):3660–3665. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3660-3665.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumiya Y, Ellison TJ, Yeh ETH, Jung JU, Luciw PA, Kung HJ. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K-bZIP represses gene transcription via SUMO modification. J Virol. 2005;79(15):9912–9925. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9912-9925.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klucevsek K, Wertz M, Lucchi J, Leszczynski A, Moroianu J. Characterization of the nuclear localization signal of high risk HPV16 E2 protein. Virology. 2007;360(1):191–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovelman R, Bilter GK, Glezer E, Tsou AY, Barbosa MS. Enhanced transcriptional activation by E2 proteins from the oncogenic human papillomaviruses. J Virol. 1996;70(11):7549–7560. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7549-7560.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Hwang SG, Kim J, Choe J. Functional interaction between p/CAF and human papillomavirus E2 protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(8):6483–6489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Lee B, Kim J, Kim DW, Choe J. cAMP response element-binding protein-binding protein binds to human papillomavirus E2 protein and activates E2-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(10):7045–7051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KY, Broker TR, Chow LT. Transcription Factor YY1 Represses Cell-free Replication from Human Papillomavirus Origins. J Virol. 1998;72(6):4911–4917. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4911-4917.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng X, Ludes-Meyers JH, Wilson VG. Isolation of an amino-terminal region of bovine papillomavirus type 1 E1 protein that retains origin binding and E2 interaction capacity. J Virol. 1997;71(1):848–852. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.848-852.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis H, Webster K, Sanchez-Perez AM, Gaston K. Cellular transcription factors regulate human papillomavirus type 16 gene expression by binding to a subset of the DNA sequences recognized by the viral E2 protein. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Part 8):2087–2096. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-8-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Knight JD, Jackson SP, Tjian R, Botchan MR. Direct interaction between Sp1 and the BPV enhancer E2 protein mediates synergistic activation of transcription. Cell. 1991;65(3):493–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90467-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SJ, Hochstrasser M. A new protease required for cell-cycle progression in yeast. Nature. 1999;398(6724):246–251. doi: 10.1038/18457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longworth MS, Laimins LA. Pathogenesis of human papillomaviruses in differentiating epithelia. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68(2):362–373. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.362-372.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matunis MJ, Coutavas E, Blobel G. A novel ubiquitin-like modification modulates the partitioning of the Ran-GTPase-activating protein RanGAP1 between the cytosol and the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 1996;135(6):1457–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhillips MG, Oliveira JG, Spindler JE, Mitra R, McBride AA. Brd4 is required for E2-mediated transcriptional activation but not genome partitioning of all papillomaviruses. J Virol. 2006;80(19):9530–9543. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01105-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Dasso M. Modification in reverse: the SUMO proteases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32(6):286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A, Ritzkowsky A, Steger G. Cooperative activation of human papillomavirus type 8 gene expression by the E2 protein and the cellular coactivator p300. J Virol. 2002;76(21):11042–11053. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.11042-11053.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YC, Breiding DE, Sverdrup F, Richard J, Androphy EJ. AMF-1/Gps2 binds p300 and enhances its interaction with papillomavirus E2 proteins. J Virol. 2000;74(13):5872–5879. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.5872-5879.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrose KJ, McBride AA. Proteasome-mediated degradation of the papillomavirus E2-TA protein is regulated by phosphorylation and can modulate viral genome copy number. J Virol. 2000;74(13):6031–6038. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6031-6038.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps WC, Howley PM. Transcriptional trans-activation by the human papillomavirus type 16 E2 gene product. J Virol. 1987;61(5):1630–1638. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1630-1638.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangasamy D, Wilson VG. Bovine papillomavirus E1 protein is sumoylated by the host cell Ubc9 protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(39):30487–30495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank NM, Lambert PF. Bovine papillomavirus type 1 E2 transcriptional regulators directly bind two cellular transcription factors, TFIID and TFIIB. J Virol. 1995;69(10):6323–6334. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6323-6334.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MS, Desterro JMP, Lain S, Midgley CA, Lane DP, Hay RT. SUMO-1 modification activates the transcriptional response of p53. EMBO J. 1999;18:6455–6461. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Acosta G, Langereis MA, Deyrieux A, Wilson VG. Proteins of the PIAS family enhance the sumoylation of the papillomavirus E1 protein. Virology. 2005;331(1):190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Acosta G, Russell WK, Deyrieux A, Russell DH, Wilson VG. A universal strategy for proteomics studies of SUMO and other ubiquitin-like modifiers. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4(1):56–72. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400149-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Best JL, Zon LI, Gill G. SUMO-1 modification represses Sp3 transcriptional activation and modulates its subnuclear localization. Mol Cell. 2002;10(4):831–842. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00682-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H, Yasugi T, Benson JD, Dowhanick JJ, Howley PM. Targeted mutagenesis of the human papillomavirus type 16 E2 transactivation domain reveals separable transcriptional activation and DNA replication functions. J Virol. 1996;70:1602–1611. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1602-1611.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D, Muller S. PIAS/SUMO: new partners in transcriptional regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60(12):2561–2574. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger MR, Ottinger M, You J, Howley PM. Brd4-independent transcriptional repression function of the papillomavirus E2 proteins. J Virol. 2007;81(18):9612–22. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00447-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger MR, You JX, Howley PM. Bromodomain protein 4 mediates the papillomavirus E2 transcriptional activation function. J Virol. 2006;80(9):4276–4285. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4276-4285.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senechal H, Poirier GG, Coulombe B, Laimins LA, Archambault J. Amino acid substitutions that specifically impair the transcriptional activity of papillomavirus E2 affect binding to the long isoform of Brd4. Virology. 2007;358(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalholz BA, Yang YC, Howley PM. Transactivation of a bovine papilloma virus transcriptional regulatory element by the E2 gene product. Cell. 1985;42(1):183–191. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger G, Corbach S. Dose-dependent regulation of the early promoter of human papillomavirus type 18 by the viral E2 protein. J Virol. 1997;71(1):50–58. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.50-58.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger G, Ham J, Lefebvre O, Yaniv M. The bovine papillomavirus 1 E2 protein contains two activation domains: One that interacts with TBP and another that functions after TBP binding. EMBO J. 1995;14(2):329–340. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger G, Schnabel C, Schmidt HM. The hinge region of the human papillomavirus type 8 E2 protein activates the human p21(WAF1/CIP1) promoter via interaction with Sp1. J Gen Virol. 2002;83(Part 3):503–510. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenlund A, Botchan MR. The E2 trans-activator can act as a repressor by interfering with a cellular transcription factor. Genes Dev. 1990;4(3):476. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubenrauch F, Colbert AME, Laimins LA. Transactivation by the E2 Protein of Oncogenic Human Papillomavirus Type 31 Is Not Essential for Early and Late Viral Functions. J Virol. 1998;72(10):8115–8123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8115-8123.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SH, Gloss B, Bernard HU. During negative regulation of the human papillomavirus-16 E6 promoter, the viral E2 protein can displace Sp1 from a proximal promoter element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20(2):251–256. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SH, Leong LEC, Walker PA, Bernard HU. The human papillomavirus type 16 E2 transcription factor binds with low cooperativity to two flanking sites and represses the E6 promoter through displacement of Sp1 and TFIID. J Virol. 1994;68(10):6411–6420. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6411-6420.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierry F, Yaniv M. The BPV1-E2 trans-acting protein can be either an activator or a repressor of the HPV18 regulatory region. EMBO J. 1987;6(11):3391–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchimura Y, Nakamura M, Sugasawa K, Nakao M, Saitoh H. Overproduction of eukaryotic SUMO-1- and SUMO-2-conjugated proteins in Escherichia coli. Analytical Biochem. 2004;331(1):204–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchimura Y, Nakao M, Saitoh H. Generation of SUMO-1 modified proteins in E-coli: towards understanding the biochemistry/structural biology of the SUMO-1 pathway. FEBS Lett. 2004;564(1–2):85–90. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verger A, Perdomo J, Crossley M. Modification with SUMO - A role in transcriptional regulation. EMBO Rep. 2003;4(2):137–142. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voitenleitner C, Botchan M. E1 protein of bovine papillomavirus type 1 interferes with E2 protein-mediated tethering of the viral DNA to mitotic chromosomes. J Virol. 2002;76(7):3440–3451. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3440-3451.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F, Scholer HR, Atchison ML. Sumoylation of Oct4 enhances its stability, DNA binding, and transactivation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(29):21551–21560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson VG, Rangasamy D. Intracellular targeting of proteins by sumoylation. Exp Cell Res. 2001;271(1):57–65. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, Lee AY, Hou SY, Kemper JK, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Chiang CM. Brd4 links chromatin targeting to HPV transcriptional silencing. Genes Dev. 2006;20(17):2383–2396. doi: 10.1101/gad.1448206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SH, Sharrocks AD. SUMO promotes HDAC-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol Cell. 2004;13(4):611–617. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JM, Breiding DE, Androphy EJ. Functional interaction of the bovine papillomavirus E2 transactivation domain with TFIIB. J Virol. 1998;72:1013–1019. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1013-1019.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J, Croyle JL, Nishimura A, Ozato K, Howley PM. Interaction of the bovine papillomavirus E2 protein with Brd4 tethers the viral DNA to host mitotic chromosomes. Cell. 2004;117(3):349–360. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]