Abstract

The motion of a rigid sphere in a viscoelastic medium in response to an acoustic radiation force of short duration was investigated. Theoretical and numerical studies were carried out first. To verify the developed model, experiments were performed using rigid spheres of various diameters and densities embedded into tissue-like, gel-based phantoms of varying mechanical properties. A 1.5 MHz, single-element, focused transducer was used to apply the desired radiation force. Another single-element, focused transducer operating at 25 MHz was used to track the displacements of the sphere. The results of this study demonstrate good agreement between theoretical predictions and experimental measurements. The developed theoretical model accurately describes the displacement of the solid spheres in a viscoelastic medium in response to the acoustic radiation force.

I. INTRODUCTION

The mechanical properties and physiological state of biological tissues are often linked; as a result, pathological changes in tissues are usually related to changes in their biomechanical parameters.1–4 Further, a noninvasive assessment of the mechanical properties of tissue is often needed in surgical and therapeutic practices. Recent studies have shown that an acoustical radiation force can be used in many biomedical applications including ophthalmology,5–7 detecting and characterizing lesions,8 the imaging of arteries with calcification,9 monitoring thermal lesions during high-intensity focus ultrasonic treatment,10 screening muscle condition,11 the detecting foreign objects in the body,12 etc.

An acoustic radiation force arising from absorption of an ultrasound wave can be used in remote palpation to either directly assess local mechanical properties of tissue,13–18 or to produce excitation19–22 in shear wave elasticity imaging. If an acoustic inhomogeneity is present inside the tissue, the radiation force can be generated through reflection of the ultrasound wave. For example, a harmonic, low-frequency radiation force was applied to solid spheres of various sizes.23 The spheres were embedded in tissue-like phantoms to estimate the resonance frequencies of spheres and their dependence on the viscoelastic properties of the media. A laser vibrometer was used to measure the vibration speed of the sphere. It was demonstrated that the method can be used to determine the local material properties of the medium surrounding the sphere. Also, the acoustic radiation force was applied to a gas bubble produced by a femtosecond laser in tissue-like phantoms.6,7 It was shown that the displacement of the bubble is affected by the elastic modulus of the surrounding gel.

In our previous studies we developed a general approach to estimate the displacement of rounded objects (specifically, gas bubbles and solid spheres) in a viscoelastic medium in response to applied acoustic radiation force.24 The developed model could potentially help assess mechanical properties of tissues using microbubbles as acoustic targets. The first step of the validation process, and the goal of the current study, is to theoretically and experimentally investigate the dynamic behavior of a rigid sphere in a viscoelastic medium under a radiation force of short duration (less than 10 ms). A model to describe the motion of a solid sphere was derived and solved both analytically and numerically. Further, experimental studies using tissue-like gelatin-based phantoms with embedded solid spheres were conducted to verify the developed model. The experiments were performed with spheres of different sizes and densities. The motion of the sphere was induced by acoustic pulses of different durations. The elastic properties of the phantoms were varied. In all cases, there was a good agreement between theoretical predictions and experimental measurements. The results of our study strongly suggest that the developed theoretical model predicts the dynamic behavior of a solid sphere in a viscoelastic medium. Consequently, this theoretical model can be used to assess the mechanical properties of the medium surrounding the sphere.

II. THEORY

In our previous studies we considered the displacements of a solid sphere and a gas bubble in a linear viscoelastic medium, under an external, time-dependent, acoustic radiation force.24 Theoretical results were obtained for compressible and incompressible media. However, as most soft tissues are nearly incompressible,25 we consider an incompressible medium only. The equation of motion for an incompressible medium is

| (1) |

where U is a displacement vector, μ and η are shear elastic and viscous coefficients, P is internal pressure, ρ is medium density, and t is time.

We assume that the sphere is placed in an axisymmetric field of the radiation force. The polar axis of the spherical system of coordinates is along the force vector (i.e., an angle θ is between a radius vector and displacement), U =(Ur, Uθ, 0) and the boundary conditions at the surface of the rigid solid sphere of radius R are

| (2) |

where U is the displacement of the sphere. The external force applied to the displaced spherical object is26

| (3) |

where σrr and σrθ are stress tensor components at the surface of the object:

| (4) |

Because the radial component of the strain vanishes (∂Ur/∂r=0) on the surface of the sphere (r=R), Eq. (3) can be rewritten using only the shear component of stress tensor and the internal pressure:

| (5) |

As shown previously,24 the displacement of the sphere U0 in a static case is

| (6) |

where F(ext) is an external force applied on the surface of a rigid sphere (e.g., acoustic radiation force). This equation also describes the displacement of the sphere in a viscoelastic medium if constant external force is applied over a long period of time. Clearly, the sphere displaced by U0 is in equilibrium position when external force is compensated for by the elastic forces from the medium.

The equation for the sphere motion (1) in the frequency domain is given by

| (7) |

where p and u are the Fourier transforms of P and U, ω is an angular frequency, and force dependence on time is assumed to be proportional to e−iωt. Taking into account the inertial forces, the equation that couples a spectral component of solid sphere displacement uω and the Fourier transform of external force is obtained:24

| (8) |

where M is a mass of solid sphere and k is a complex wave number k2=ρω2/(μ−iωη).

For an infinitely light sphere, where M=0, Eq. (8) becomes a well-known solution for the impedance of the sphere.27 After applying inverse Fourier transform we obtain the sphere displacement U in time domain:

| (9) |

In the elastic case, where η=0, Eq. (8) for solid sphere motion can be written in time domain:24

| (10) |

where is the shear wave speed and parameter β = ρs/ρ is the solid sphere density ρs normalized by medium density ρ. Initial conditions for the differential equation (10) are zero.

Here, we consider that acoustic radiation force applied to a solid sphere is impulsive, i.e.,

| (11) |

where t0 is the duration of the acoustic radiation force pulse and F0 is amplitude of the force. The Fourier transform of this function is

| (12) |

In the elastic case, after substituting Eq. (11) into Eq. (10), an analytical solution of Eq. (10) can be obtained:

| (13) |

where

are the roots of an algebraic equation: (1+2β)λ2+9λ+9=0.

Solution (13) is a sum of two time-dependent, exponential functions where the real parts of the exponents are always negative. If normalized density β is smaller than 5/8, the exponents are real and, therefore, the sphere first displaces from, and then returns to, the origin exponentially. However, if the sphere is sufficiently dense (β>5/8), the exponents are complex and the sphere starts to oscillate with a linear frequency

defined by the imaginary part of the exponent (Fig. 1).

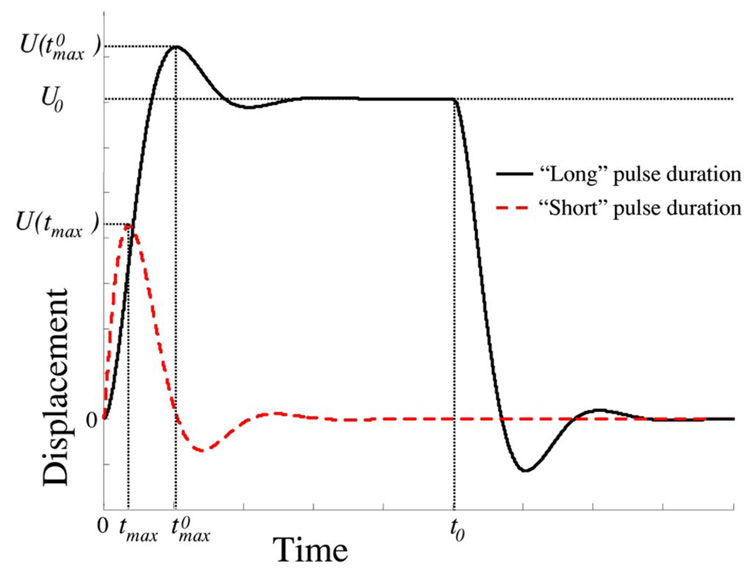

FIG. 1.

(Color online) Schematic representation of the displacements of a dense sphere (β>5/8) embedded in a purely elastic medium in response to “long” and “short” pulse durations (not to scale). If the duration of the acoustic radiation force pulse t0 is sufficiently long, the displacement reaches its maximum value and then the sphere oscillates around its equilibrium position U0 until the pulse is ended and the sphere returns and oscillates around the original position.

Initially, once the acoustic force is applied, the sphere will be gradually displaced from the origin (Fig. 1). If the duration of the acoustic radiation force pulse t0 is sufficiently long, the displacement of the dense sphere (β>5/8) reaches its maximum value where

| (14) |

and

| (15) |

Once the sphere reaches the maximum of the displacement and while the acoustic radiation force is still acting on the sphere, i.e., during (Fig. 1), the dense sphere will oscillate around its equilibrium position U0 defined by Eq. (6). For a light sphere (β<5/8), no oscillations will be present. For infinitely long duration t0 of the acoustic radiation force, as expected, Eq. (13) converges to Eq. (6) regardless of the normalized density of the sphere. Here the acoustic force is compensated for by the elastic response of the medium, and the displaced sphere is stationary as long as the external force is applied on the sphere.

To better understand the relationship between the displacement of the sphere and the properties of the sphere and the surrounding medium, consider a limiting case when the duration of the acoustic pulse t0 is infinitely short. Using the Taylor expansion of the time-dependent exponential functions around zero, the solution of Eq. (13) for impulsive excitation can be obtained:

| (16) |

The displacement reaches its peak at the time tmax

| (17) |

and the maximum displacement U(tmax) is

| (18) |

Note that U(t) and tmax are real even if λ1 and λ2 are complex.

The previous analysis demonstrates a difference in maximum displacement between short and long durations of acoustic radiation force pulse. For example, Eq. (18) shows that for short impulses the maximum displacement is inversely proportional to the square root of shear elasticity and the square of the sphere radius. However, for long pulses, the displacement is inversely proportional to both shear elasticity and the radius, as is evident from Eq. (15). When the excitation time t0 cannot be considered infinitely short, but both the maximum of the displacement U(tmax) and the time to reach the maximum of the displacement tmax are functions of t0. Generally, therefore, the relationship between the spatiotemporal behavior of the sphere and the properties of the sphere and the surrounding medium is more complex as described by Eq. (13). Equation (13)–Equation (18) are useful in the quantitative analysis of the motion of the sphere in the elastic medium. However, in the experimental verification of the developed theoretical model, the viscosity should be taken into account.

In case of the viscoelastic medium, the displacement of the sphere can be written in an integral form by combining Eq. (8), Eq. (9), and Eq. (12):

| (19) |

Viscosity reduces both the oscillations in sphere displacement and the displacement maximum. Integral (19) can be evaluated numerically. In fact, this equation was used to obtain all theoretical estimations presented in this article.

III. EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

To verify our theoretical model, the experiments were performed using rigid spheres of various diameters and densities embedded into gel-based phantoms of varying mechanical properties. The parameters of the seven spheres used in our study are listed in Table I. Three spheres (A, B, and C) had the same density but different diameters. The other four spheres (D, E, F, and G) had the same diameter but different densities.

TABLE I.

Parameters of the solid spheres used in the radiation force experiments.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Sapphire | Sapphire | Sapphire | Glass | Glass | Plastic | Metal |

| BK7 | LaSFN9 | ||||||

| Density (kg/m3) | 3980 | 3980 | 3980 | 2510 | 4440 | 700 | 9060 |

| Diameter (mm) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

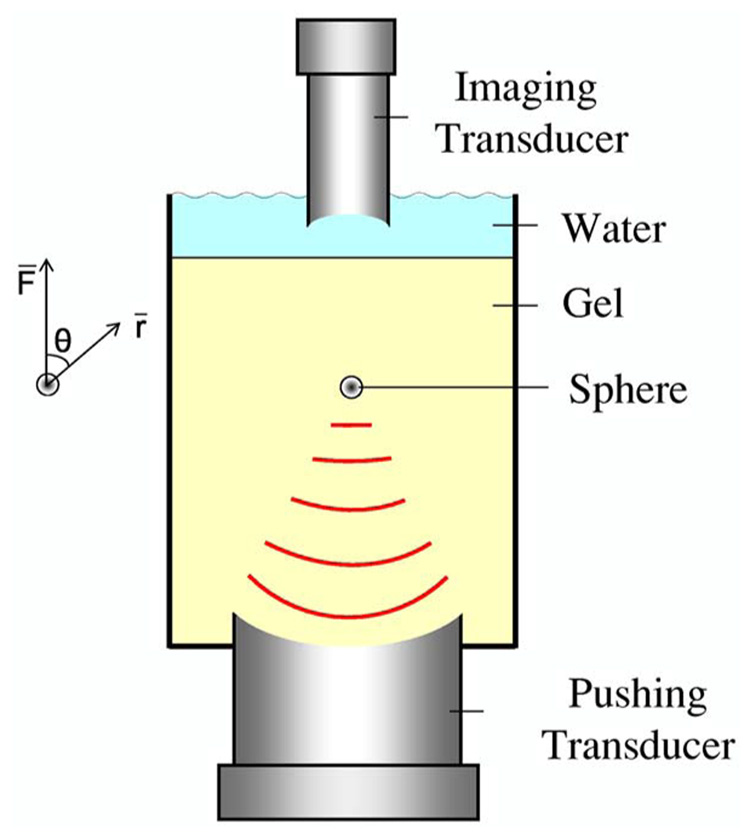

An experimental setup is schematically shown in Fig. 2. A plastic tank with a pushing (1.5 MHz) transducer attached at the bottom was filled with 3% by weight gelatin (300 Bloom, type-A, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO) to insure good contact between the phantom surface and the transducer. The resulting cubic phantoms with embedded rigid spheres were about 55 mm in linear size. The remaining portion of the tank was filled with water to provide contact between the imaging (25 MHz) transducer placed on the top of the tank and the phantom.

FIG. 2.

(Color online) A schematic view of an experimental setup. A tank was filled with 3% by weight gelatin. A rigid sphere was embedded in the gel at the focal zone of a 1.5 MHz, single-element focused transducer attached to the bottom of the tank. To generate acoustic radiation force, short pulses were used. To monitor sphere position, a 25 MHz single-element transducer was placed at the top of the tank.

During phantom preparation, the same gelatin solution was used to prepare a cylindrical test sample of 35 mm diameter by 17 mm height. This sample was used to independently measure elastic properties of the phantom material. Both phantom and sample were constructed at the same time and underwent the same procedures (storage, experimental protocol, etc.) to minimize any possible differences in elastic properties. To estimate the shear elastic modulus of the samples, the uniaxial load–displacement measurements were performed using an In-Spec 2200 portable system (Instron, Inc., Norwood, MA). The control samples placed in a water tank were deformed axially up to 10% strain with 0.2 mm/s deformation rate. For each given temperature, the experiments were repeated at least five times to evaluate the accuracy of the measurements. In all measurements, the standard deviation did not exceed 15%.

Once a sphere was embedded into a phantom, the experiments were performed at the temperatures ranging from 4 to 22 °C. For gelatin, these temperature changes resulted in change of shear elasticity from 4 to 0.5 kPa (i.e., temperature and shear elasticity of gelatin are inversely proportional). Therefore, by varying the temperature, it was possible to change the elasticity of the surrounding material without changing the position of the sphere relative to the pushing transducer or the imaging transducer. The temperature of the phantom was controlled by a digital thermometer with a sensor embedded into the phantom about 10 mm away from the sphere.

A 1.5 MHz single-element focused transducer (Valpey Fisher Corp., Hopkinton, MA) was attached to the bottom of the tank to generate acoustic radiation force. The transducer has a diameter of 38 mm and a focal length of 44 mm. The function generator (Agilent 33250A, Agilent Technologies, Inc, Santa Clara, CA) was used to generate the sinusoidal signal applied through a radio frequency (rf) power amplifier (ENI model 240L, ENI, Rochester, NY) to the pushing transducer.

The position of the sphere was monitored using a 25 MHz, 6.35 mm diameter, single-element transducer with a focal length of 13 mm. The transducer was connected to a pulser/receiver operating at a 20 kHz pulse repetition rate (Panametrics 5910PR, Panametrics, Waltham, MA). The pulse-echo signal was captured using an 8 bit, 500 MHz A/D data acquisition card (CompuScope 8500, GaGe Inc., Montreal, Canada).

Prior to the experiment, the foci of both the pushing and the imaging transducers were aligned at the location of the embedded sphere. The position of the sphere was tracked every 50 µs for up to 20 ms. The duration of acoustic radiation force pulse was varied from 0.33 to 10 ms. The displacement of the sphere was measured using a phase-sensitive, cross-correlation motion tracking algorithm.28 The pushing pulse was applied 0.5 ms after the imaging sequence, consisting of repetitive pulse-echo firing, was initiated. The initial pulse-echo record captured prior to the radiation force pulse was used as a reference point for the cross-correlation procedure.

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To verify the developed model describing the motion of a solid sphere in response to applied radiation force, a set of experiments was performed using spheres of different sizes and densities, various durations of acoustic radiation force pulses, and elastic properties of the surrounding material. In the theoretical analysis, Eq. (19) was used to compare the experimental and theoretical results. The amplitude of radiation force F0 was obtained by fitting the theoretical predictions to experimental data. It was assumed that the shear viscosity of gelatin is 0.1 Pa s and does not depend on the temperature. This value provided the best agreement with experimental data and is consistent with literature data.19,21

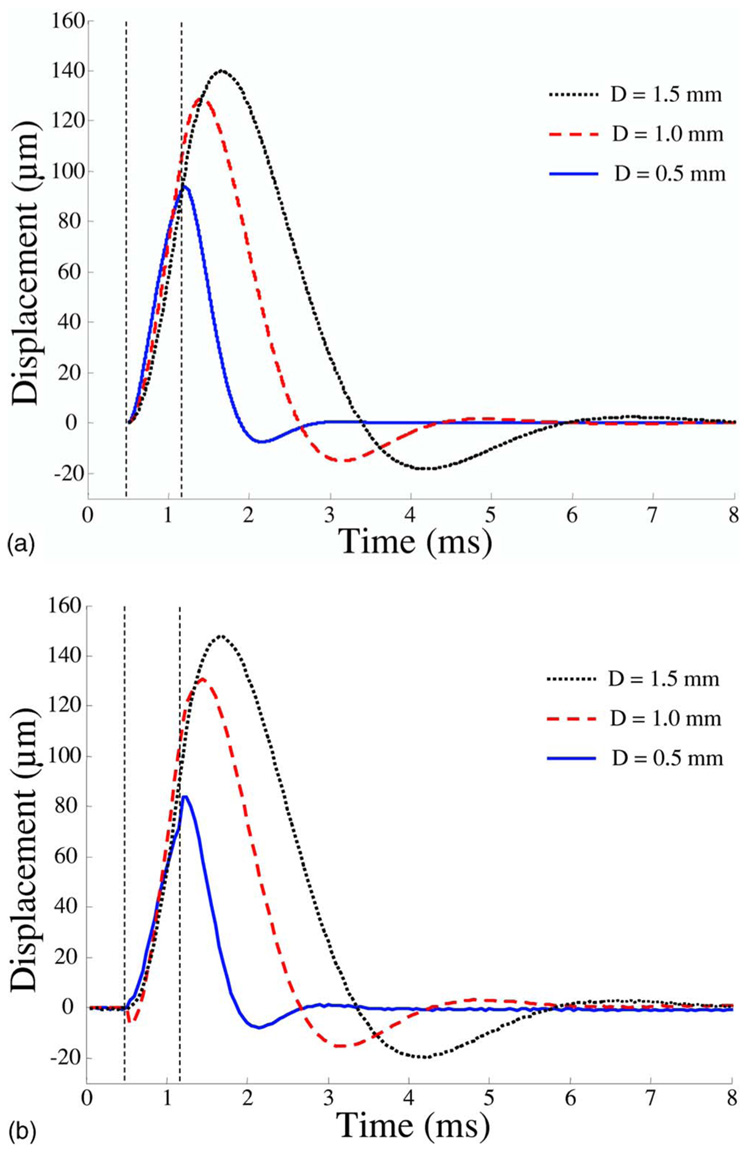

The motion of the 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 mm diameter spheres (spheres A, B, and C, correspondingly) in response to acoustic radiation force is presented in Fig. 3. The dotted vertical lines in Fig. 3 mark the beginning (t=0.5 ms) and the end of the 0.67 ms pushing pulse. The theoretical results in Fig. 3(a) were obtained assuming that radiation pressure in the focal zone of the excitation transducer is constant and equals approximately 732 Pa. This assumption is reasonable as the size of the sphere is smaller than or comparable to the 1.2 mm wide ultrasound beam in the focal zone of the 1.5 MHz transducer. As the radiation pressure is defined as the force divided by the surface area of the sphere, the pressure of 732 Pa corresponds to 0.57, 2.3, and 5.2 mN forces for the spheres A, B, and C, respectively.

FIG. 3.

(Color online) Displacements of 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 mm diameter spheres (spheres A, B, and C in Table I) embedded in a viscoelastic medium. Acoustic radiation force excitation time was 0.67 ms, shear elasticity of media was measured and assumed to be 1300 Pa. (a) Theory: shear viscosity of media was 0.1 Pa s and the pressure on sphere surface was 732 Pa corresponding to 0.57, 2.3, and 5.2 mN forces acting on the spheres A, B, and C, correspondingly. (b) Experiment: note excellent agreement with theoretical model.

Although the radiation force increases with the radius of the sphere, the elastic response of the material increases as well. The displacement of the sphere is larger for the larger sizes of the sphere. However, because in this experiment the duration of the acoustic pulse t0 was not very short and the relationship between displacement and the radius of the sphere is not defined by either Eq. (15) or Eq. (18) describing impulsive or long acoustic pulses, correspondingly. At the end of the pushing pulse the sphere continues to move until it reaches a maximum of the displacement. The independently measured shear elasticity of gelatin for all three phantoms was about 1300 Pa. This value was used in numerical analysis presented in Fig. 3(a). Figure 3(b) shows the results of the experimental studies for spheres embedded in three different phantoms with approximately the same acoustical and mechanical properties. As expected, the displacements are larger for larger spheres. Clearly, the agreement between experimental results and theoretical predictions is excellent.

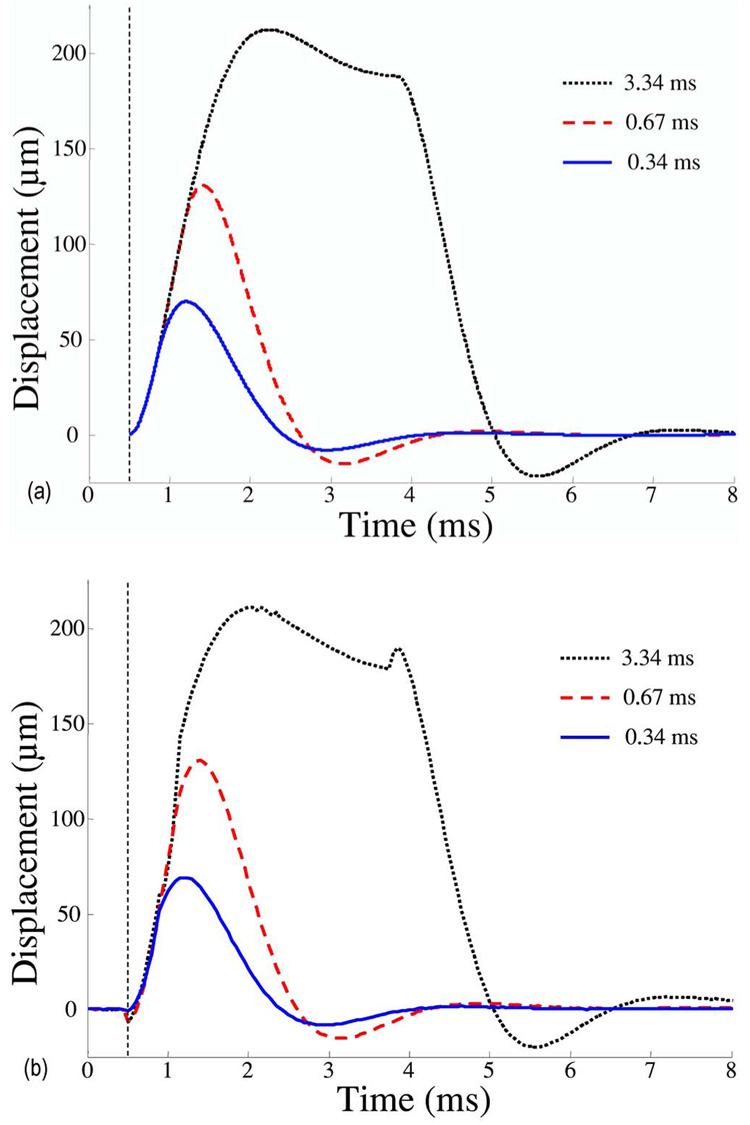

The motion of the sphere in response to radiation force pulses of different durations is presented in Fig. 4. The vertical dotted line in Fig. 4 indicates the beginning of the pulsed radiation force. In the experiments, a 1 mm diameter sphere (sphere B in Table I) was used. As the duration of the acoustic radiation force pulse increases, the displacement of the sphere initially increases and then it reaches the point of equilibrium where acoustic force is compensated for by the elastic response of the medium At the end of the acoustic pulse, this dense sphere (β=3.98> 5/8) oscillates around the point of equilibrium. Similar oscillatory motion is present when the pushing pulse has ended and the sphere is returning to the original position. In addition, the time needed to reach the maximum of the displacement increases with the pulse duration. Again, the agreement between theory and experiment is nearly perfect although experimental estimates have a finite signal-to-noise ratio. The measurements are sometimes prone to signal processing artifacts due to electromagnetic interference noise introduced by the rf amplifier at the beginning and at the end of the pushing pulses, which results in signal decorrelation, as is evident in the inaccurate estimate at the end of the 3.34 ms long pushing pulse [Fig. 4(b).]

FIG. 4.

(Color online) Displacements of the 1 mm diameter sphere (sphere B in Table I) in response to excitation pulses of different (0.34, 0.67, and 3.34 ms) durations. Shear elasticity of media was 1300 Pa. (a) Theory and (b) experiment.

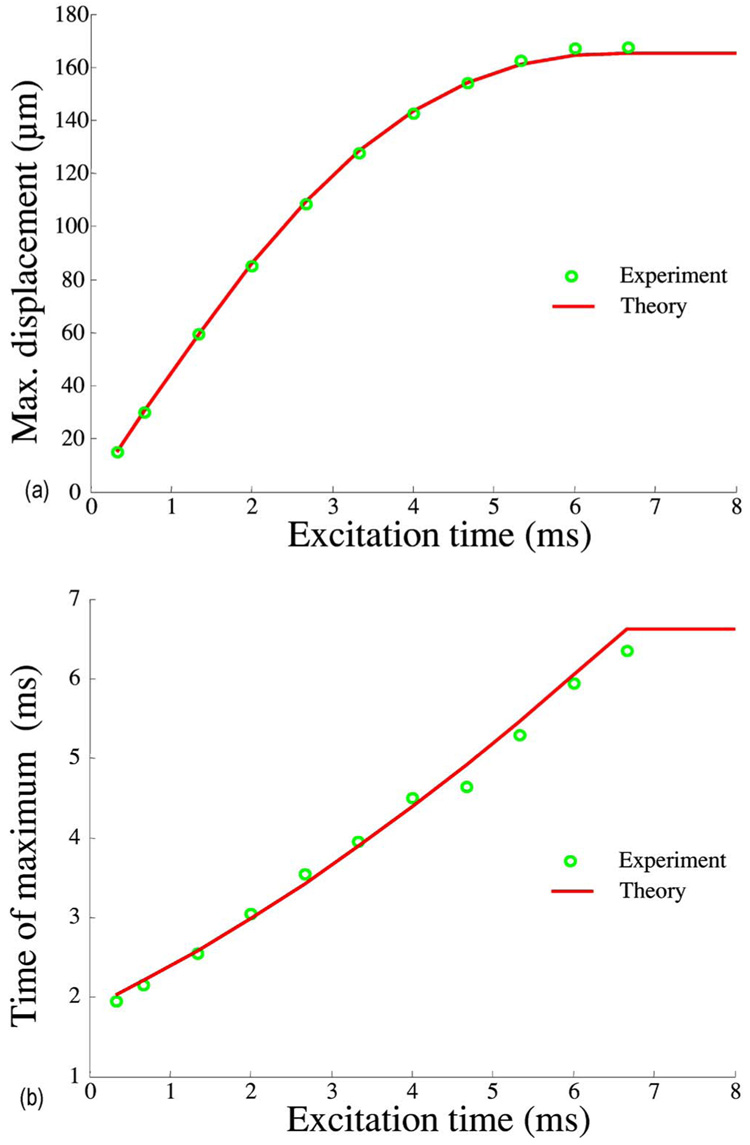

The maximum displacement U(tmax) and the time needed to reach maximum displacement tmax were analyzed. The dependences of these quantities on the duration t0 of the excitation pulse are presented in Figs. 5(a) and 5(b) for theoretical and experimental data, respectively. The experiments were performed using a 3 mm glass sphere (sphere D in Table I). The time when the displacement reaches the saturation point is about 7 ms, and for the time of maximum displacement is constant:

FIG. 5.

(Color online) Comparison of theoretically predicted and experimentally measured behavior of sphere D (see Table I) embedded into gelatin with 600 Pa shear modulus. In the theoretical model, the applied force was 2.6 mN. (a) Maximum displacement of the sphere vs excitation time. (b) Time needed to reach maximum displacement vs excitation time.

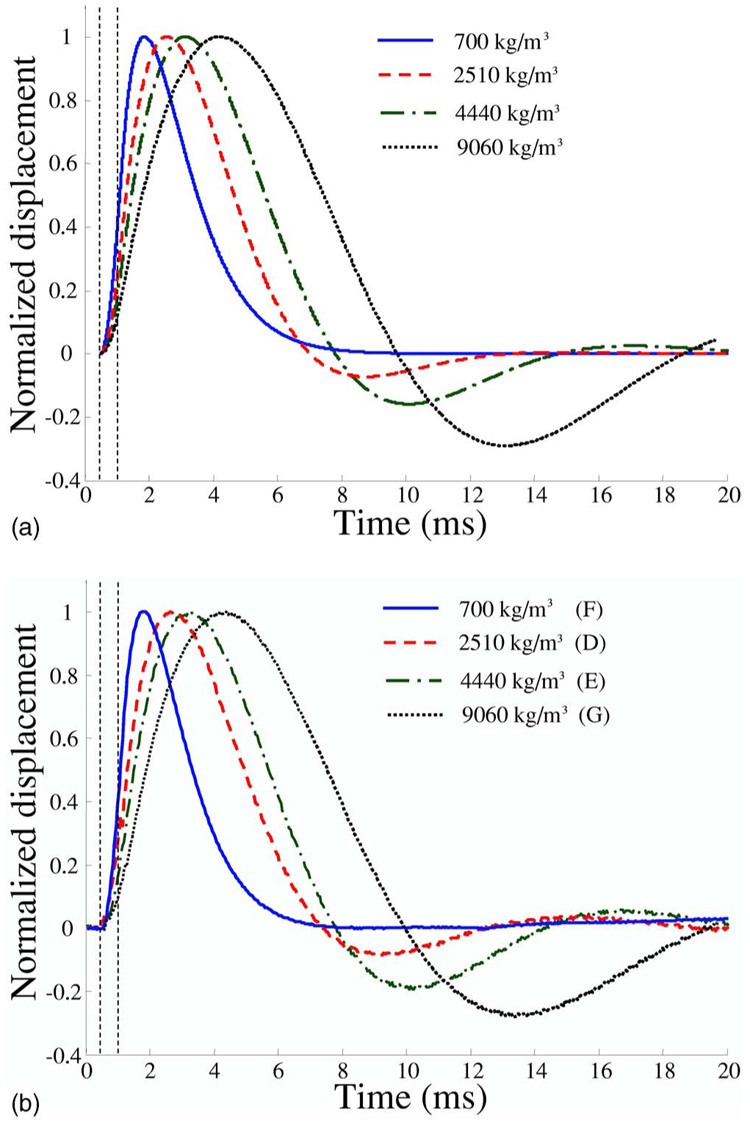

Theoretical and experimental results for spheres with various densities (spheres D, E, F, and G in Table I) are presented in Figs. 6(a) and Fig. 6(b). Because material properties of the spheres are different, the radiation force applied to spheres cannot be considered the same even though the spheres have the same size.29 However, the magnitude of the radiation force is only a scalar factor and, in linear approximation, it does not influence temporal behavior of the sphere motion.

FIG. 6.

(Color online) Normalized displacements of 3 mm diameter spheres (spheres D, E, F, and G) with different densities. Excitation time was 0.67 ms and shear elasticity of media was 600 Pa. (a) Theory and (b) experiment.

Therefore, normalized displacements were used to compare experimental measurements and numerical estimations. All other parameters except density were the same. The time of maximum displacement increases with increased density of the sphere. In addition, the oscillations are more pronounced for denser spheres. Displacement of the lighter plastic sphere (sphere F in Table I) exhibits oscillations in neither the theoretical model nor in the experiment although the normalized density for this sphere is slightly more than 5/8. This is explained by a non-zero shear viscosity (0.1 Pa s) of the medium. Again, there is good agreement between experimental and theoretical data.

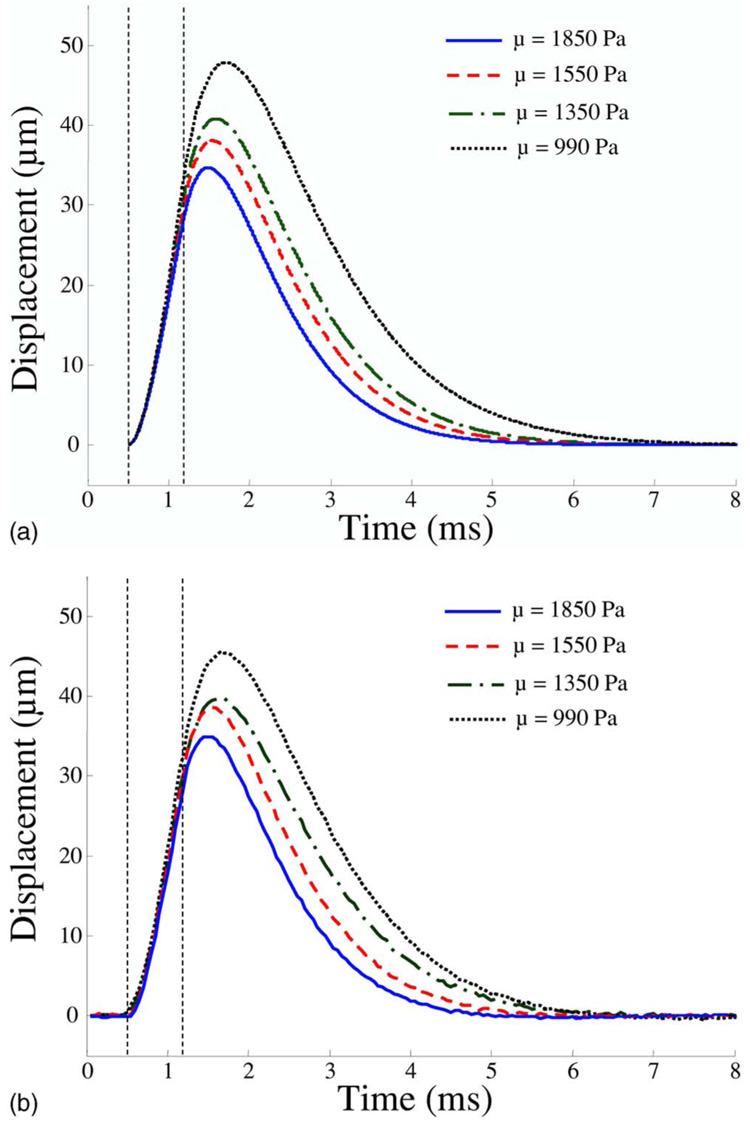

Figures 7(a) and 7(b) compare theoretical and experimental results obtained for a 3 mm light sphere (sphere F in Table I) embedded in a medium with changing elastic properties. Shear moduli were measured 990, 1350, 1550, and 1850 Pa at 20, 18, 14, and 10 °C temperatures of the phantom, correspondingly. Increase in elasticity of the surrounding material lead to decrease of both displacement magnitude and time needed for the displacement to reach the maximum. This is clearly demonstrated from theoretical data in Fig. 7(a). These results are in agreement with theoretical and experimental results obtained by other groups,8,17,18,20 where the response to acoustical radiation force was investigated for a medium with different elasticity.

FIG. 7.

(Color online) Displacements of the 3 mm diameter light sphere (sphere F) in a medium with different shear modulus. Shear moduli was measured 990, 1350, 1550, and 1850 Pa at 20, 18, 14, and 10 °C temperatures of the phantom, correspondingly. Excitation time was 0.67 ms. (a) Theory, applied force was 4.6 mN and (b) experiment.

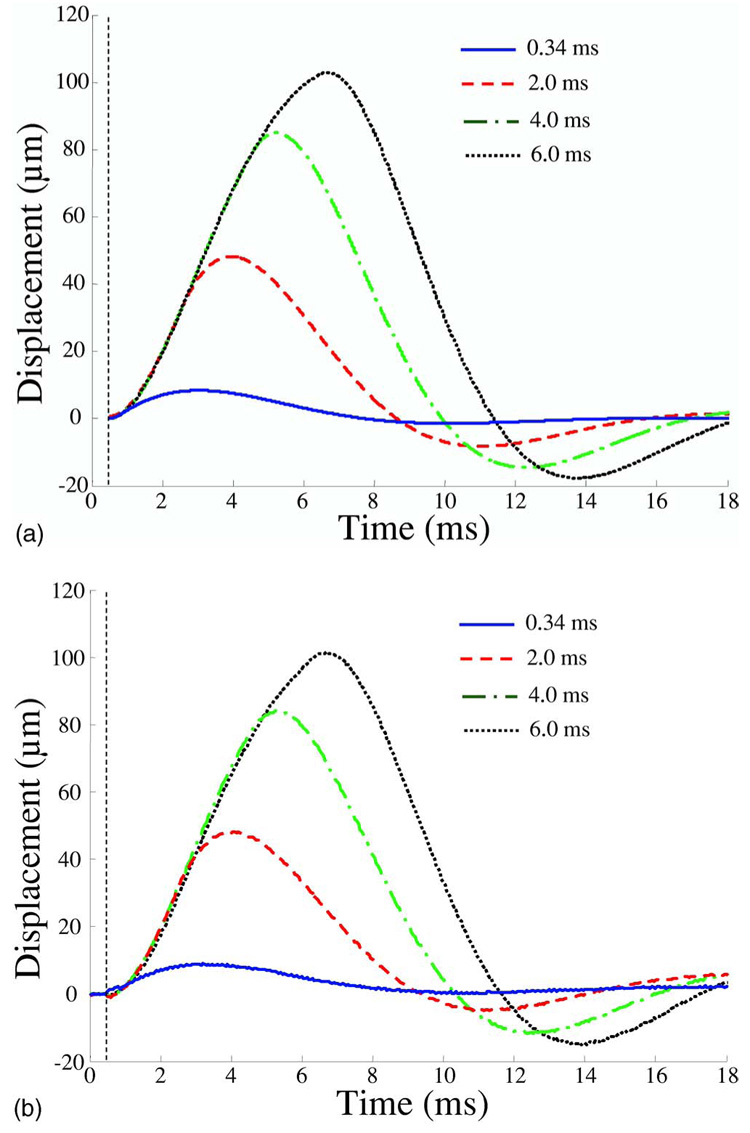

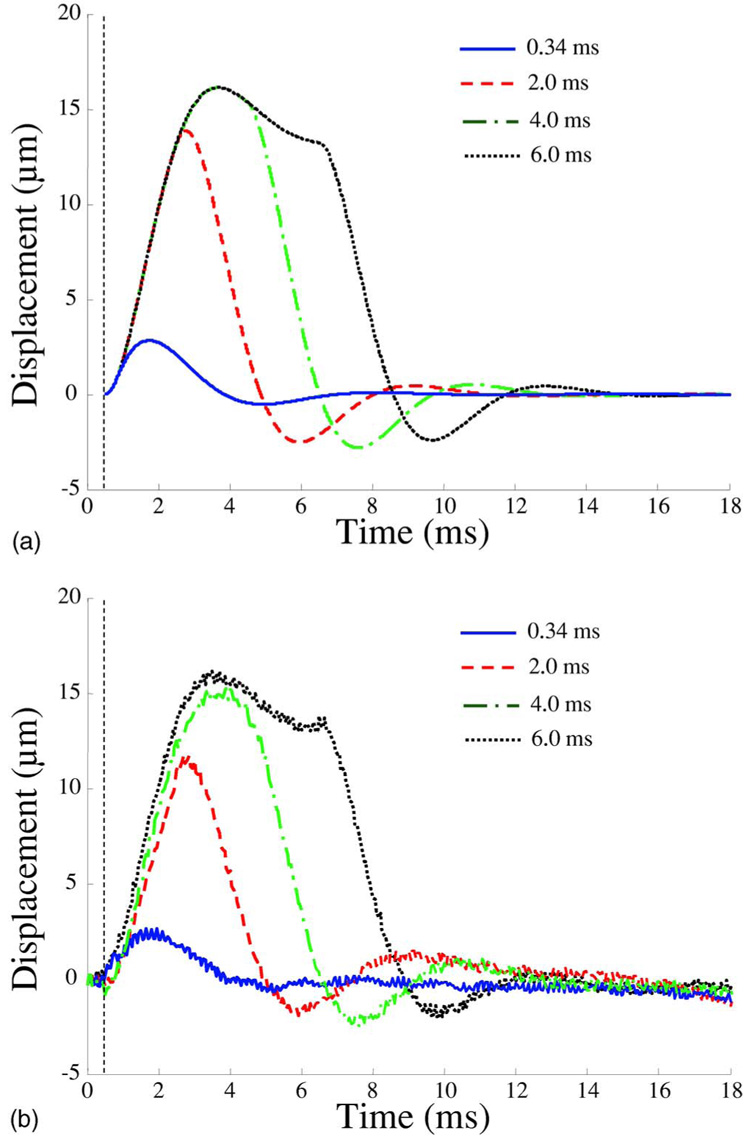

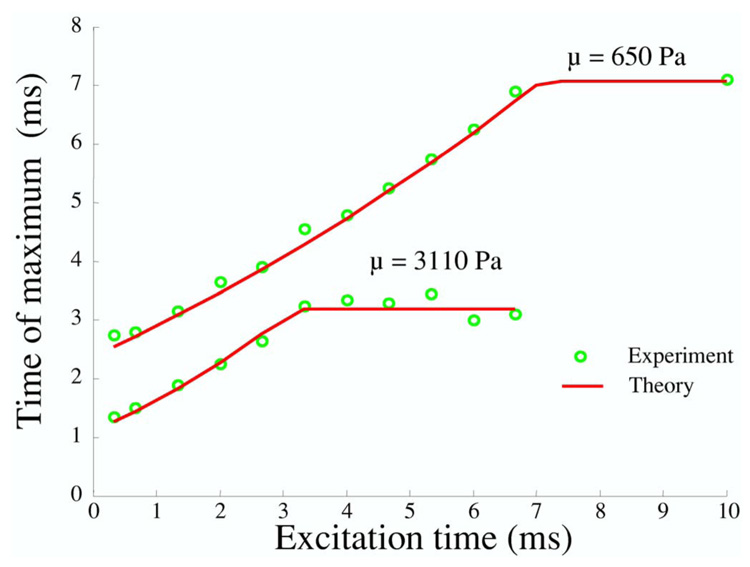

To investigate the influence of media elasticity on sphere behavior under various durations of radiation force, the theoretical and experimental studies were performed for two different temperatures (20 and 6 °C). The 3 mm diameter glass sphere (sphere E in Table I) was embedded in the phantom. The shear elastic moduli of the phantom for 20 and 6 °C were estimated as 650 and 3110 Pa, respectively. The theoretical and experimental results for 650 Pa shear elasticity are presented in Figs. 8(a) and 8(b), where the time dependences for different time of excitation are shown. Figures 9(a) and 9(b) present the same results for a sphere in the medium with 3110 Pa shear elasticity. These results show that the displacements are higher for soft material and the saturation of displacement starts earlier for harder material. For a medium with 650 Pa shear elasticity, the maximum displacement continues to increase even for the excitation time of 6 ms. For a medium with 3110 Pa shear elasticity, however, the saturation point is already reached for acoustic radiation force pulses shorter than 4 ms. It should also be noted that even though the same phantom was used for both sets of the experiments, the estimated radiation forces were different: 1.65 mN for 650 Pa and 1.2 mN for 3110 Pa. This can be attributed to temperature-dependent acoustic properties of gelatin.30 However, theoretical and experimental temporal characteristics of sphere motion are in good agreement and our results generally agree with results of Erpelding et al.7 where the decrease of the maximum time for hard material was measured using a gas bubble as a target for acoustical radiation force. Figure 10 outlines the relationship between the time needed to reach the maximum displacement and the excitation time. Again, the two values of elasticity were considered.

FIG. 8.

(Color online) Displacements of the 3 mm diameter sphere (sphere E) embedded in the medium with shear elasticity 650 Pa (temperature 20 °C) in response to excitation pulses of different durations. (a) Theory, applied force was 1.65 mN and (b) experiment.

FIG. 9.

(Color online) Displacements of the 3 mm diameter sphere (sphere E) embedded in the medium with shear elasticity 3110 Pa (temperature 6 °C) in response to excitation pulses of different durations. (a) Theory, applied force was 1.2 mN and (b) experiment.

FIG. 10.

(Color online) Comparison of theoretically predicted and experimentally measured dependences of time of maximum displacement on excitation time for the 3 mm sphere (sphere E) and for two different shear elasticity coefficients: μ=650 Pa (temperature 20 °C) and μ=3110 Pa (temperature 6 °C).

Results shown in Fig. 7 – Fig. 9 demonstrate that the displacement of the sphere decreases when the elasticity of the medium increases. However, it is difficult to rely on the displacement amplitude alone to estimate the elasticity of the medium. In addition to shear elastic modulus, the displacement amplitude also depends on the magnitude of the radiation force applied to the sphere. However, the energy delivered to the tissue located in the focal spot of the pushing beam is unknown given the differences in attenuation of various tissues and the evaluation of radiation force magnitude presents a challenge.

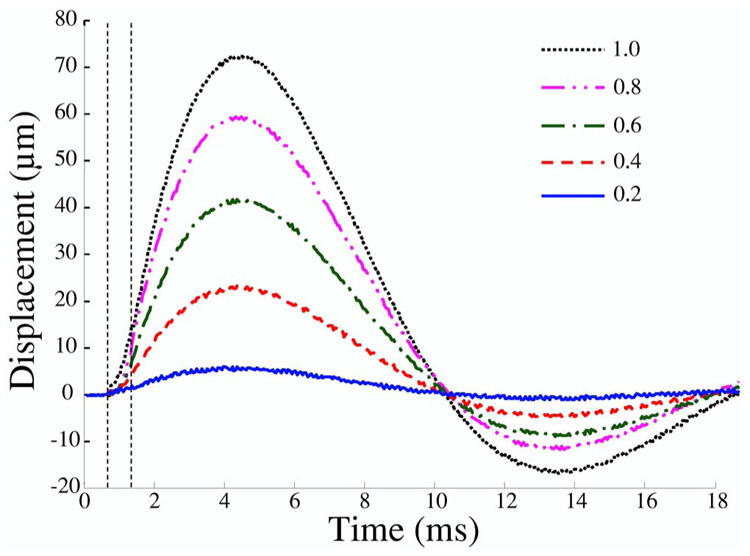

On the contrary, the time characteristics of the sphere motion are independent of the radiation force amplitude because the force is only a scaling factor in the model describing the displacement of the sphere. Figure 11 illustrates this point: the displacements of a 3 mm diameter metal sphere (sphere G) are contrasted for radiation force pulses of different magnitude (the pre-amplified voltage applied to the pushing transducer is normalized to the maximum value). The duration of the pulses was set to 0.67 ms in all experiments. As is evident from Fig. 11, the amplitude of the displacement is proportional to the amplitude of radiation force, but temporal characteristics of the displacement (e.g., time needed to reach the maximum of the displacement or time needed for the sphere to come back to the point of the origin) remain the same. These results suggest that elastic properties of the tissue can be estimated from temporal rather than spatial characteristics of the sphere motion.

FIG. 11.

(Color online) Displacements of the 3 mm diameter metal sphere (sphere G) in response to 0.67 ms long pulses of various amplitudes (normalized to a maximum value). Shear elasticity of media was 600 Pa. Note temporal similarity of motion.

In general, the motion of the sphere in tissue is related to both elasticity and viscosity of the medium. The theoretical analysis and numerical studies for solid sphere and gas bubble dynamics in a viscoelastic medium are presented elsewhere.24 The displacement of a solid sphere or gas bubble in the medium with no viscosity has an oscillatory character while viscosity eliminates oscillations in the displacements and reduces the maximum value of the displacement amplitude. The formalism developed here suggests that both shear elasticity and shear viscosity may be evaluated from the response of the sphere to the radiation force excitation. In this work, however, influence of shear viscosity on sphere behavior is not considered for two reasons. First, there is not a standard method to measure independently the shear viscosity of tissues and tissue-like materials. Gold standard methods exist only for liquids, but these methods cannot be directly used for solids. Hence, we cannot reliably verify our estimation of shear viscosity modulus. Second, our model-based estimation of the shear viscosity for gel phantoms used in the acoustical radiation force experiments resulted in 0.1 Pa s. As the elastic modulus was modified by changing the temperature of the phantom, the viscosity was also expected to change. However, the slight variations of the shear viscosity because of temperature variations did not significantly affect the results. In accordance with our theoretical analysis, the influence of shear viscosity in this range is negligible and elasticity of the medium largely defines the behavior of the sphere. Nevertheless, our shear viscosity estimation is in agreement with the results obtained by several research groups.19,21 For example, the shear viscosity estimation based on the measurement of shear wave amplitude attenuation gave a value of 0.1 Pa s for a 4% gelatin phantom.21 Others estimated the shear viscosity of gelatin phantoms using two independent methods: measuring shear wave speed dispersion and measuring resonance frequencies of an embedded solid sphere.19 The shear viscosity for 12% gelatin phantoms was found in the range of 0.2–0.4 Pa s. Taking into account that we used a 3% by weight concentration of gelatin, the viscosity estimation in 0.1 Pa s appears to be reasonable. However, additional studies are needed to fully investigate the influence of shear viscosity on oscillatory and translational motion of the sphere in a viscoelastic medium.

The results of our study can be applied in many biomedical and clinical fields. For example, the model developed here could possibly assist laser-based diagnosis and microsurgery in ophthalmology. The microbubbles created during laser-tissue interaction in the cornea, lens and vitreous humor, are used as part of surgery procedures.31,32 In each case, using acoustic radiation force applied to laser induced microbubbles, the mechanical properties of the eye components could be estimated to improve diagnosis or therapeutic strategy. There are no fundamental differences between solutions describing dynamic behavior of a solid sphere and an air bubble in a viscoelastic medium. The difference is only in the boundary conditions on the surface of the spherical object.24 Therefore, air bubbles can be used as targets for the acoustical radiation force measurements6,7 thus allowing remote estimation of tissue elasticity of the cornea, lens and vitreous humor. However, further experiments are needed to validate the theory of gas microbubbles behavior in viscoelastic tissue.

V. CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study demonstrate that the theoretical model predicts the motion of the solid spheres in viscoelastic medium in response to the acoustic radiation force. Our investigation of the sphere response to the acoustic radiation force for various sphere sizes and densities in media with different elastic properties shows that there is a good agreement between theoretical predictions and experimental measurements.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health under Grant Nos. CA112784 and EY018081.

Footnotes

PACS number(s): 43.25.Qp, 43.35.Mr, 43.80.Qf [MFH]

Contributor Information

Salavat R. Aglyamov, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712-0238 and The Institute of Mathematical Problems of Biology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Pushchino, Moscow Region, Russia 142290

Andrei B. Karpiouk, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712-0238

Yurii A. Ilinskii, Applied Research Laboratories, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78713-8029

Evgenia A. Zabolotskaya, Applied Research Laboratories, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78713-8029

Stanislav Y. Emelianov, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712-0238

References

- 1.Fung YC. Biomechanics. Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ophir J, Alam SK, Garra B, Kallel F, Konofagou E, Krouskop T, Varghese T. Elastography: Ultrasonic estimation and imaging of the elastic properties of tissues. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng., Part H: J. Eng. Med. 1999;213:203–233. doi: 10.1243/0954411991534933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aglyamov SR, Skovoroda AR. Mechanical properties of soft biological tissues. Biophycics. 2000;45:1103–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarvazyan AP. Elastic properties of soft tissues. In: Levy M, Bass H, Stern R, editors. Handbook of Elastic Properties of Solids, Liquids and Gases. Vol. 3. New York: Academic; 2001. pp. 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Negron LA, Viola F, Black EP, Toth CA, Walker WF. Development and characterization of a vitreous mimicking material for radiation force imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2002;49:1543–1551. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2002.1049736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erpelding TN, Booi RC, Hollman KW, O’Donnell M. Measuring tissue elastic properties using acoustic radiation force on laser-generated bubbles. Proc.-IEEE Ultrason. Symp. 2003;1:554–557. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erpelding TN, Hollman KW, O’Donnell M. Bubble-based acoustic radiation force elasticity imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2005;52:971–979. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1504019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nightingale K, Soo MS, Nightingale R, Trahey G. Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging: In vivo demonstration of clinical feasibility. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2002;28:227–235. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fatemi M, Greenleaf JF. Ultrasound-stimulated vibro-acoustic spectrography. Science. 1998;280:82–85. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lizzi FL, Muratore R, Deng CX, Ketterling JA, Alam SK, Mikaelian S, Kalisz A. Radiation-force technique to monitor lesions during ultrasonic therapy. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2003;29:1593–1605. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(03)01052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nightingale KR, Nightingale RW, Stutz DL, Trahey GE. Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging of in vivo vastus medialis muscle under varying isometric load. Ultrason. Imaging. 2002;24:100–108. doi: 10.1177/016173460202400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitri FG, Trompette P, Chapelon JY. Improving the use of vibro-acoustography for brachytherapy metal seed imaging: A feasibility study. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2004;23:1–6. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.819934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugimoto T, Ueha S, Itoh K. Tissue hardness measurement using the radiation force of focused ultrasound. Proc.-IEEE Ultrason. Symp. 1990;3:1377–1380. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fatemi M, Greenleaf JF. Application of radiation force in noncontact measurement of the elastic parameters. Ultrason. Imaging. 1999;21:147–154. doi: 10.1177/016173469902100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker WF. Internal deformation of a uniform elastic solid by acoustic radiation force. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1999;105:2508–2518. doi: 10.1121/1.426854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nightingale KR, Palmeri ML, Nightingale RW, Trahey GE. On the feasibility of remote palpation using acoustic radiation force. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2001;110:625–634. doi: 10.1121/1.1378344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skovoroda AR, Sarvazyan AP. Determination of viscoelastic shear characteristics of a medium from its response to focused ultrasonic loading. Biophycics. 1999;44:325–329. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calle S, Remenieras JP, Matar OB, Hachemi ME, Patat F. Temporal analysis of tissue displacement induced by a transient ultrasound radiation force. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005;118:2829–2840. doi: 10.1121/1.2062527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, Fatemi M, Greenleaf JF. Quantifying elasticity and viscosity from measurement of shear wave speed dispersion. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004;115:2781–2785. doi: 10.1121/1.1739480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarvazyan AP, Rudenko OV, Swanson SD, Fowlkes JB, Emelianov SY. Shear wave elasticity imaging: A new ultrasonic technology of medical diagnostics. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1998;24:1419–1435. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(98)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bercoff J, Tanter M, Muller M, Fink M. The role of viscosity in the impulse diffraction field of elastic waves induced by the acoustic radiation force. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2004;51:1523–1536. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2004.1367494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nightingale KR, Zhai L, Dahl JJ, Frinkley KD, Palmeri ML. Shear wave velocity estimation using acoustic radiation force impulsive excitation in liver in vivo. Proc.-IEEE Ultrason. Symp. 2006:1156–1160. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen S, Fatemi M, Greenleaf JF. Remote measurement of material properties from radiation force induced vibration of an embedded sphere. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2002;112:884–889. doi: 10.1121/1.1501276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilinskii YA, Meegan GD, Zabolotskaya EA, Emelianov SY. Gas bubble and solid sphere motion in elastic media in response to acoustic radiation force. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005;117:2338–2346. doi: 10.1121/1.1863672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarvazyan AP. Low frequency acoustic characteristics of biological tissues. Mech. Polymers. 1975;4:691–695. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landau LD, Lifshitz EM. Fluid Mechanics. 2nd ed. New York: Pergamon; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oestreicher HL. Field and impedance of an oscillating sphere in a viscoelastic medium with an application to biophysics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1951;23:707–714. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lubinski MA, Emelianov SY, O’Donnell M. Cross-correlation speckle tracking techniques for ultrasound elasticity imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1999;46:82–96. doi: 10.1109/58.741427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasegawa T, Yosioka K. Acoustic-radiation force on a solid elastic sphere. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1969;46:1139–1143. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madsen EL, Zagzebski JA, Banjavie RA, Jutila RE. Tissue mimicking materials for ultrasound phantoms. Med. Phys. 1978;5:391–394. doi: 10.1118/1.594483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogel A, Capon MRC, Asiyo-Vogel MN, Birngruber R. Intraocular photodisruption with picosecond and nanosecond laser pulses: Tissue effects in cornea, lens, and retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 1994;35:3032–3044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lubatschowski H, Maatz G, Heisterkamp A, Hetzel U, Drommer W, Welling H, Ertmer W. Application of ultrashort laser pulses for intrastromal refractive surgery. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2000;238:33–39. doi: 10.1007/s004170050006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]