Abstract

Objective

This article focuses on design, training, and delivery of MI in a longitudinal randomized controlled trial intended to assess the efficacy of two separate interventions designed to increase colorectal screening when compared to a usual care, control group. One intervention was a single-session, telephone-based motivational interview (MI), created to increase colorectal cancer screening within primary care populations. The other was tailored health counseling. We present the rationale, design, and process discussions of the one-time motivational interview telephone intervention. We discuss in this paper the training and supervision of study interventionists, in order to enhance practice and research knowledge concerned with fidelity issues in motivational interview interventions.

Methods

To improve motivational interview proficiency and effectiveness, we developed a prescribed training program adapting MI to a telephone counseling session.

Results

The four interventionists trained in MI demonstrate some MI proficiency assessed by the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Scale. In the post-intervention interview, 20.5% of the MI participants reported having had a CRC screening test, and another 19.75% (n = 16) had scheduled a screening test. Almost half of the participants (43%) indicated that the phone conversation helped them to overcome the reasons why they had not had a screening test.

Conclusions

Ongoing supervision and training (post MI workshop) are crucial to supporting MI fidelity. The trajectory of learning MI demonstrated by the interventionists is consistent with the eight stages of learning MI. The MI roadmap created for the interventionists has shown to be more of a distraction than a facilitator in the delivery of the telephone intervention. MI can, however, be considered a useful tool for health education and warrants further study.

Practice Implications

MI training should include consistent training and process evaluation. MI can, however, be considered a useful tool for health education and warrants further study. MI can also be adapted to diverse health promotion scenarios.

1. Introduction

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a client-centered, directive method for enhancing motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence [1]. The growing empirical support for the use of MI in clinical settings as a psychotherapeutic treatment for excessive drinking [2-4] has facilitated interest and excitement for exploring the use of MI across a number of health behaviors [5,6], including but not limited to diet and nutrition [7], tobacco use [8], and mammography [9]. This article describes experiences in a single-session, telephone-based MI intervention, created to increase colon cancer screening in a federally funded randomized effectiveness trial within primary care populations. Because so few MI study articles detail the interventions, and because researchers have been called to provide intervention information on specifically “pure” MI studies to better evaluate rigor and internal validity [10], this article focuses on design, training, and delivery of MI in this research. This article also contributes to the growing literature on telephone counseling for disease prevention in diverse health care settings [11].

1.1. Background

There is a dearth of literature concerned with the application of MI for cancer care behaviors. Relevant publications to date come from Taplin’s and colleagues’ use of MI via telephone counseling to promote mammography [9,11]. In that study, a stratified random sample of women aged 50-79 were recruited; 3,743 women were randomly assigned to one of three intervention groups, including a reminder postcard group, a reminder telephone call group, and (n = 590) an MI telephone call addressing barriers to mammography. Women who received reminder calls were more likely to get a mammogram than women who were mailed postcards; the motivational and reminder calls had equivalent effects. Other publications addressing the use of motivational interventions (not necessarily MI) for cancer related behaviors include [12], [13], [14], and [15].

As cited in Burke, Arkowitz, & Dunn [10], six publications depict the use of MI or adaptations of MI (AMI) (for example, Motivational Enhancement Therapy [MET]) and provide support for administering MI via the telephone [9,16-20] Only two of the six articles reported randomized controlled trials [11,18], and only the Ludman et al. project [11](discussed above) specifically used MI as opposed to an AMI.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview of the study

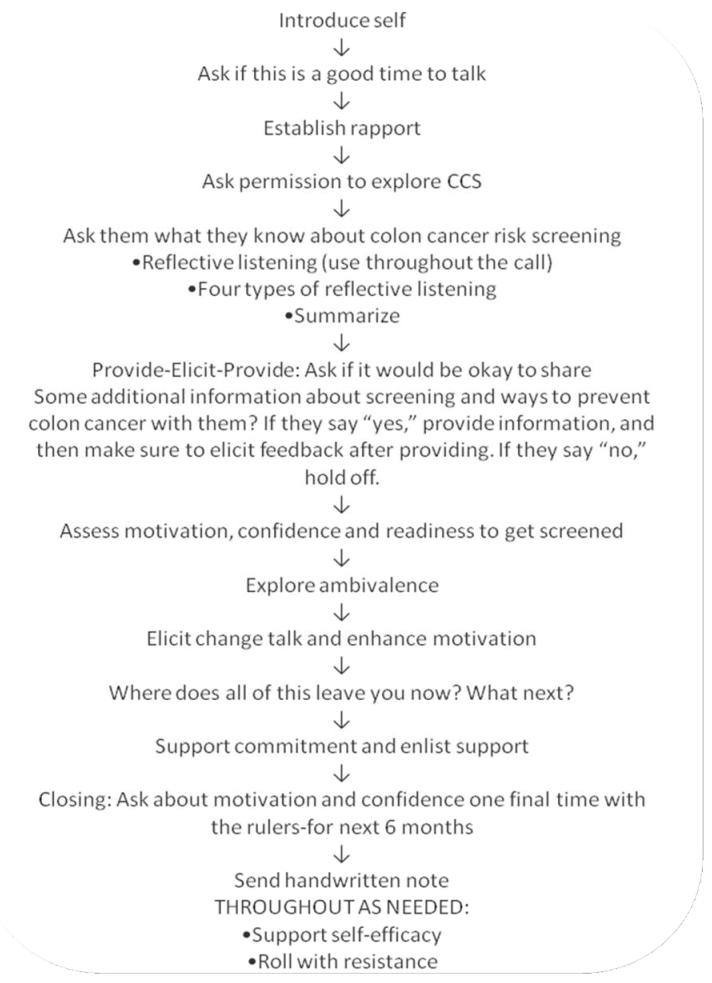

The purpose of the original longitudinal randomized controlled trial, from which this report is drawn, is to assess the efficacy of two separate interventions designed to increase colorectal screening test use when compared to a usual care, control group. Enrolled participants are randomly assigned to one of three study groups: Group 1, usual care control; Group 2, tailored health counseling; and Group 3, motivational interview counseling. This paper focuses on the development of the MI intervention delivered by telephone to one-third of the study sample. Participants are interviewed on beliefs and stages of readiness related to CRC screening three times: at baseline, one month post intervention, and six months post intervention. The two interventions are both phone-based. The tailored health counseling phone counselors rely on a preprinted script that is based on responses to the baseline questionnaire. The MI calls proceed as described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The intervention phone call road map

To date, 524 individuals have been randomized into the study. Of the 178 randomized to the MI group, 132 are veterans, 137 have completed baseline interviews, and 124 have received the MI intervention call. The study sample was recruited from two primary care settings in a large Midwestern metropolis: the Jesse Brown Veteran’s Administration Medical Center and the University of Illinois-Chicago Medical Center. Specifically, participants were recruited from four VA clinics and two UIC clinics. Characteristics of the sample and intervention efficacy will be reported subsequent to study completion.

2.2. Purpose of the intervention phone call

The purpose of the intervention phone call is to utilize MI to support individuals to consider and possibly engage in colon cancer screening (CCS). The main objective is to support study participants to think and talk about their thoughts and feelings concerning CCS. Study interventionists were trained to use MI to help people explore and resolve their ambivalence around CCS, as well as explore and enhance their motivation to get screened.

Given the sensitive issues about CCS (i.e., distaste for handling stool, invasive nature of colonoscopy, dialogue about a potentially terminal illness [cancer], and cross-cultural differences such as gender, age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation and ability), MI use was vital, as it would provide us with tools to sensitively explore and navigate these topics.

2.3. The spirit of the MI call

What is referred to as the MI spirit is the style and essence of the practitioner’s disposition and interaction with the client or patient. Spirit differs from technique; it provides the foundation for the skills and techniques. While skills and techniques can be taught, spirit is more elusive and is believed to come from within the clinician [1].

Miller and Rollnick [1] point to three particular elements of the MI spirit: collaboration, evocation, and autonomy. Collaboration refers to the partnership between the client and practitioner. The practitioner honors the client’s expertise and perspectives. Through collaboration, the practitioner facilitates an atmosphere that is conducive rather than coercive to change. Within our particular intervention, rather than telling study participants that they should get screened for colon cancer (CC), the interventionist works with individuals to understand what they know (or do not know) about CC and CCS. The interventionist also explores how important it is for the participant to get screened, as well as the accompanying reasons. In addition, the MI practitioner strives for evocation of the client’s intrinsic motivations for change by drawing on the client’s own perceptions, goals, and values. MI differs from solution-focused and behavior-change counseling in how the practitioner strategically “uses her or his own responses to elicit and reinforce certain kinds of speech, from the client, while reducing other types of client responses” [21]. Autonomy permeates the MI spirit, as the practitioner validates and supports the client’s right to self-determination and direction. If an individual chooses not to get screened or remains ambivalent about getting screened, the interventionist does not push or coerce the study participant to get screened. Overall, the MI spirit involves an availability and willingness to listen closely enough to glimpse a client’s situation, feelings, and motivations for change.

Unlike confrontational techniques, MI aims to support individuals to generate reasons, plans, and motivations for change. Practitioners should not impose diagnostic labels, engage clients in a punitive or coercive fashion, argue that the client needs to change, or create a change plan for the client. Rather, the MI clinician facilitates a process whereby clients convince themselves to consider and engage in behavior change--in this case, to get screened for CC.

2.4. Development of the MI intervention

In creating the MI intervention phone call, we paid close attention to Emmons and Rollnick’s [5] considerations for adapting MI in new health care settings. These considerations include preserving the core elements of the spirit of MI (collaboration, evocation and autonomy), providing adequate training to interventionists, and including supplemental strategies to the intervention (in this case, a handwritten note was sent to the participant after the completed intervention phone call).

Because MI is an interpersonal style [22] rather than a set of techniques “applied to people” [5], a formulaic approach (often found in manuals) to the intervention phone call was deemed inappropriate. This meant that interventionists needed first to be trained in MI practice before being trained in the intervention’s phone call. Key intervention phone call components and techniques included establishing rapport; asking permission to discuss CC and CCS; eliciting what the participant already knows about CC and CCS; assessing motivation, confidence and readiness to get screened; exploring ambivalence about getting screened; eliciting change talk; rolling with resistance; and (if appropriate) supporting self-efficacy and commitment to get screened.

We were ambivalent about creating a manual or script for the intervention. On one hand, we did not want to be prescriptive about the call; we wanted interventionists to be free to be client-centered, stay authentic, and go where the participant wanted and needed. On the other hand, we felt that it might be helpful and important for interventionists, particularly those new to MI, to have some prompts to support them to call on a range of MI skills and techniques as needed. Consequently, we settled on creating a sample road map that interventionists could choose to use to help them navigate the call (Figure 1).

2.6. Training

Interventionists received 20 hours of initial training over a period of three consecutive days. Four of these hours were specifically dedicated to learning about CC and CCS, this part of the training was conducted by the PI who has expertise in the area. The MI specific training consisted of 16 hours and took place over a period of 2 days. The first day and a half (12 hours) of the MI training consisted of an introductory workshop (see http://motivationalinterview.org/training/expectations.html for details about what to expect from an MI introductory workshop). The remaining four hours was specifically focused on training the interventionists to integrate the MI skills and spirit with the actual intervention call (see sample roadmap, Figure 1). During this time interventionists practiced via role plays with each other and the trainer administering the MI intervention. Interventionists received very specific and personal feedback from the trainer, in addition to mentoring and guidance during this call. Following the 20 hours of initial training, interventionists individually engaged in practice sessions via the telephone with the MI trainer. In addition, interventionists audio-tape recorded all of the pilot intervention calls they made and sent the recordings to the MI trainer who listened to them and consequently provided individualized feedback and supervision via additional phone calls. The MI trainer determined interventionists’ readiness to begin intervention calls once they demonstrated satisfactory skills (subjectively determined by the trainer) associated with reflective listening, exploring ambivalence, eliciting change talk, and rolling with resistance. Not all interventionists were deemed ready at the same time. One interventionist in particular was asked to engage in (approximately 6) additional telephone training sessions with the trainer prior to being ready.

2.7 Building rapport

At the onset of the call, interventionists know the participant’s name, telephone number and that the participant meets the study criteria, including not having been screened for CC according to evidence-based guidelines [23]. The initial component of the intervention entails building rapport with the participant to build a collaborative working alliance.

Establishing rapport over a telephone, rather than face-to-face, can be challenging. Interventionists were trained to use attentive and intuitive listening to the participants’ words, expressions, and tones in order to reach for a connection. Consistent with the MI spirit, interventionists were educated in unconditional acceptance and unconditional positive regard [24] of the participant, to facilitate a type of rapport that will support MI intervention delivery. In the training, interventionists were repeatedly trained to understand that whether the participant decides to get screened for CC was not up to the interventionist.

2.8. Asking for permission and inquiring about what they know

The rationale for asking permission to discuss CC and CCS is to alert the participant to the nature of the call, while engaging her in a respectful and inviting manner to begin to assess and understand her motivation for screening, as well as get a sense of the information (or lack thereof) that she has concerning screening. Asking individuals what they know is more respectful than simply giving them advice and information. This approach also helps build rapport and provides another opportunity to demonstrate empathy.

2.9. Exploring motivation, confidence, and readiness

A participant’s level of motivation, confidence, and readiness to get screened informs what interventionists choose to focus on and reflect for the rest of the phone call, consequently informing which MI skills and techniques are appropriate. For instance, if someone tells the interventionist that he is motivated to get screened but not confident that he can actually do it (maybe he lacks transportation or fears handling the stool samples), the interventionist is more likely to ask evocative questions related to his sense of confidence, rather than explore his motivation to get screened via the decisional balance. On the other hand, if a participant states that he is not motivated to get screened, the interventionist is more likely to spend some time exploring ambivalence and/or rolling with resistance, in addition to eliciting change talk via the following skills [1]: looking forward, looking backwards, querying extremes, exploring goals and values, and using the decisional balance.

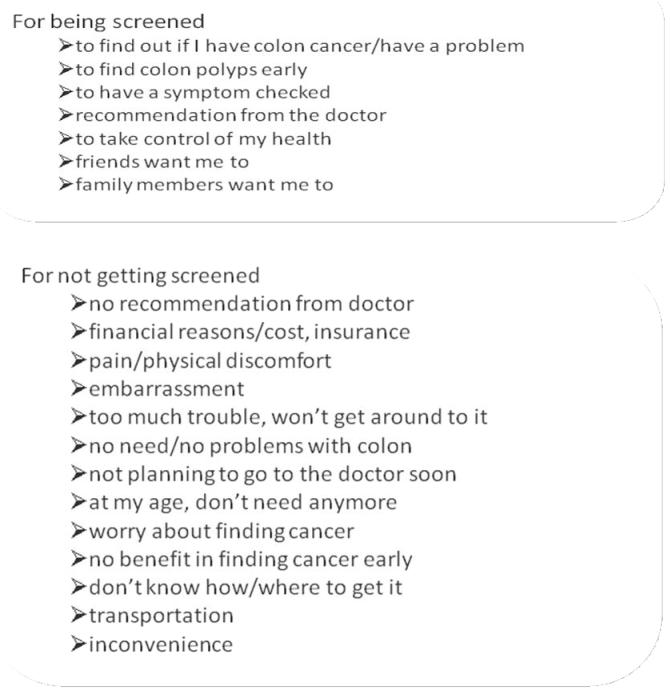

2.10. Exploring ambivalence

Ambivalence within MI is viewed as a normal and expected element of the change process. Ambivalence refers to feeling two (or more) ways about something. Often when people feel ambivalent about a behavior or change, they feel stuck and are consequently not ready to take action. The intention behind exploring ambivalence about getting screened for CC with the study participants is to help them get unstuck by supporting them to look at why they would or would not get screened. Some reasons participants have given us for getting screened or not getting screened are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Some reasons participants have given us regarding screening.

2.11. Eliciting change talk

One basic MI principle is engaging the participant to argue for change (getting screened), as well as to articulate her plans for making the change. Rather than suggest why she should get screened for CC, the interventionist uses other skills, including asking evocative questions, asking for elaboration, utilizing the decisional balance, asking the participant to look ahead, asking the participant to explore the extreme possibilities of getting and not getting screened, and exploring the participant’s goals and values concerning her health, to support her to make those comments and arguments herself. Encouraging change talk [25] and decreasing resistance talk are at the heart of MI work. Signs and language that a participant may use that indicate she may want to get screened are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Signs of readiness to get screened [Adapted from Curry SJ, Ludman EJ, Graham E, Stout J, Grothaus L, Lozano P. (2003). -Adapted from Miller, 1991]

| Decreased resistance. | The participant stops arguing, interrupting, denying, or objecting to getting screened. |

| Decreased questions about the issue. | The participant seems to have enough information about colon cancer screening, and stops asking questions. There is a sense of being finished. |

| Resolve. | The participant appears to have reached a resolution, and may seem more peaceful, relaxed, calm, unburdened, or settled. Sometimes this happens after the client has passed through a period of ambivalence or resistance. |

| Change talk. | The participant engages in DARN-C language (Miller & Rollnick, 2004).

|

| Increased questions about change. | The participant asks what he or she could do about getting screened, what the experience is like, how long it takes, etc. |

| Envisioning. | The participant begins to talk about how life might be after she gets screened, to anticipate receiving news that she has cancer or that she doesn’t have cancer. |

| Experimenting. | The participant may have already talked to his partner about getting screened. Maybe he has already made an appointment and canceled it. |

2.12. Rolling with resistance

Rather than thinking of resistance as a characteristic that resides within an individual, MI asks practitioners to view resistance as something interpersonal. Specifically, resistance within MI is viewed as arising between the counselor and a client. Miller and Rollnick [1] state that “persistent resistance is not a client problem, but a counselor skill issue (p. 99)”. Resistance can signal the interventionist that what he is doing with the participant on the phone is not working. Rather than resist or confront a lack of motivation, confidence, or readiness to get screened for CC, the interventionist is trained to roll with it. Techniques that interventionists draw upon to roll with resistance include three types of reflections (simple, double-sided, and complex), in addition to reframing, emphasizing personal choice, and refocusing (Table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of rolling with resistance skills

| Concept | Conversation | |

|---|---|---|

| Simple reflection-Reflects exactly what is heard. | Client | I don’t want to get screened. |

| Interventionist | You don’t think getting screening for CRC will work for you. | |

| Amplified reflection-Amplifies or heightens the resistance that is heard. | Client | I could not get screened. What if they find something? |

| Interventionist | It sounds like you are very concerned that a screening test might tell you something that you don’t want to hear. | |

| Double-sided reflection-Reflection points out both sides of what the client is saying. | Client | There is no question that my health is important to me. However, nobody in my family has ever had CC, and I take good care of myself. I really don’t think that I’m at risk. |

| Interventionist | So on the one hand, you appear to be saying that you really don’t see any danger that you might be at risk for CC. On the other hand, you seem to be very clear that you value your health. | |

| Shifting focus-Shifts the person’s attention away from what seems to be a stumbling block in the way of progress. | Client | My doctor probably told you to call me. You are probably calling to tell me that there is something I’m not doing right about my health. |

| Interventionist | It sounds like you think my job is to criticize you or tell you what to do. I’m sorry if I’ve given you that impression. I’m calling because I want to hear YOUR thoughts on CC screening. My job is to listen to you and hear your thoughts on why you would or wouldn’t get screened. Would you mind if we talked a bit about CC screening? | |

| Emphasizing personal choice-Stresses that the decision to get screened or not is entirely the participant’s and that nobody can make that choice for them. | Client | I’m pretty fed up with everyone always telling me how I should live my life and what I should do with my body |

| Interventionist | Nobody can force you to get screened. Even if your family or your doctor puts pressure on you to get screened, the decision is still yours. | |

| Reframing-Places a different meaning on what the person says so that the person doesn’t seem so resistant. | Client | My wife has been putting a lot of pressure on me to get screened. She bugs me about it every other day. I know that I probably should, but I’m really concerned that it is going to be uncomfortable and painful. |

| Interventionist | It sounds like you feel that your wife overreacts, but her concern makes some sense to you and you’d consider getting screened if she wasn’t pressuring you so much. What do you think about that? |

2.13. Supporting commitment and enlisting support

For those individuals who are motivated, confident and ready to get screened, it may be useful to explore and support their ideas about and commitments to getting screened. Supporting change talk can happen through the different types of reflective listening and summaries mentioned above. It can also happen by asking participants to discuss and elaborate their ideas and plans for getting screened. For instance, an interventionist might ask, “When were you planning on getting screened?” “What is your plan for getting screened?” “What might get in your way of accomplishing this plan?” “Where does this leave you now?”

Because social supports may facilitate the screening process, interventionists are trained to explore with those who are motivated, confident and ready who or what might support them getting screened. Because support can mean different things to different people, it is important to get a sense from the participants what support looks like for them. “What is one thing that might support you to follow through and get screened?” “Who in your life might be able to drive you, accompany you, talk with you, etc.?”

2.14. Handwritten note

Emmons and Rollnick [5] suggested that offering additional materials and follow-up contact may strengthen briefer MI interventions. We chose to send a handwritten note immediately after the call was terminated. The note intends to summarize and reflect the understanding of the participant’s motivation, confidence, and readiness to get screened. The note should also reflect some of the change talk that was expressed, as well as any action towards getting screened that the participant may have articulated. The note closes with the interventionist expressing confidence in the person’s abilities to make the screening happen. The following is an example of one of the notes.

It was great talking with you today; thank you for your time. I understand that while having a [colonoscopy] is worrisome to you because of potential complications and the preparation involved, you were horrified having witnessed firsthand the terrible consequences of colon cancer with your friend Jane. You’re someone who values your health a great deal, as demonstrated by your commitment to exercise and healthy eating. You mentioned that you were planning to call your doctor’s office to set up an appointment to find out more about the screening procedure. I support you and am confident in your ability to take steps to ensure your good health.

2.15. Training and supervision

Because research suggests that two-day MI workshops are nowhere near sufficient to facilitate MI proficiency among clinician trainees [26], interventionists receive ongoing weekly or bimonthly supervision via teleconference. “Studies including post-workshop training opportunities via coded feedback on sessions and phone consultations with supervisors [32] demonstrate improved therapist MI competence” [26, p. 164 referencing 32].

2.16. Process evaluation

After interventionists were trained in basic MI and the intervention phone call, regular and ongoing supervision was provided via weekly or bimonthly telephone sessions with the MI trainer/co-investigator associated with the study. Interventionists audio recorded 10% of all intervention calls that they conducted. Prior to the supervision calls, interventionists were asked to send the recording to the co-investigator and listen to their recorded call utilizing the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Scale (MITI) 2.0 [27].

The MITI codes both global counseling skills and the interventionist’s behavioral utterances. The MITI was selected for use over the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC) [28] because it is shorter, requires less time, and is less complicated. The MITI utilizes 7-point Likert-type scales for two items (empathy/understanding and spirit of MI), as well as simple tallies of interventionist behaviors, including MI adherent, MI nonadherent, questioning (open and closed), and reflecting (simple and complex). The MITI’s limitations are that it does not assess certain important components of MI, such as eliciting change talk, rolling with resistance, or exploring ambivalence [29]. Since this study was designed, new tools have been created to assess MI fidelity, including the MITI 3.0 (see http://casaa.unm.edu/download/miti3.pdf) and the Motivational Interviewing Supervision and Training Scale (MISTS) [30]. The MISTS was developed to support the training and supervision of clinicians administering interventions with MI at their core, and includes two components: a behavioral count of clinician responses and utterances and a 16-item global rating of the quality and effectiveness of the clinician’s intervention [29].

3. Results

3.1. Client Retention and Attrition

In general, respondents randomized to the MI intervention (n=150) were accepting of the MI calls. Only 11 were dropped after the baseline call, and 26 were dropped or unreachable after the intervention. The MI calls ranged in length from 9-44 minutes, with an average length of 19 min. 43 seconds.

The interventionists who worked in this arm of the study all had advanced graduate degrees from the fields of social work and psychology. Two had masters degrees in social work (and one was currently working on her PhD in public health), and one had a doctoral degree in clinical psychology). One of the interventionists (#2 in Table 3) claimed to have some previous introductory MI training. The MI trainer/supervisor has 15 years of MI practice experience coupled with 8 years of MI training, consultation, and supervision experience. The trainer has been a member of the international Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) since 1999, and has engaged MI practice, research, and teaching in health, mental health, community, and public health arenas.

Table 3.

Summary score thresholds

| Summary Score Thresholds | Interventionist 1 | Interventionist 2 | Interventionist 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st call | Middle call | Last call* | 1st call | Middle call | Last call | 1st call | Middle call | Last call | |

| Global Therapist Ratings Empathy/Understanding |

6 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Global Therapist Ratings Spirit | 6 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Reflections-to-Questions Ratio | 9:12 | 18:12 | 11:7 | 10:9 | 19:9 | 9:14 | 9:6 | 2:2 | 16:12 |

| Percent Open Questions | 91% | 75% | 43% | 77% | 88% | 86% | 50% | 50% | 58% |

| Percent Complex Reflections | 12% | 33% | 1% |

2% 33% |

53% | 33% | 33% | 31% | |

| Percent MI-Adherent | 90% | 100% | 100% |

87% 100% |

100% | 87% | 100% | 100% | |

1st call, middle, and last call refer to the first, midway** and last recorded calls for supervision purposes.

Midway refers to the midway call between their first and last recorded intervention calls.

Interventionist 1 completed 58 intervention calls.

Interventionist 2 completed 35 intervention calls.

Interventionist 3 completed 33 intervention calls.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

With 24 months of experience administering the intervention, we have already taken notice of facilitators, challenges, and issues to consider when administering the intervention. To begin, all three interventionists found the roadmap for the call to be somewhat distracting. Although all three reported using the roadmap and keeping it nearby while they made calls (particularly in the beginning of the study), they all reported in supervision sessions that they feel like the call runs more smoothly and they feel more confident when they do not have the roadmap in sight. Reasons they gave for this consistently point to the challenge that the roadmap seems to present to their sense of fluidity and authenticity with participants. In other words, when they have the roadmap nearby, they reported feeling more anxious, stressed and concerned about the various MI elements.

All interventionists have expressed their appreciation for the ongoing supervision and training that occurs via teleconference. An early review of the MITI coding sheets suggests that interventionists’ skills generally (with the exception of percentage of open questions) increased their MI-adherent behaviors and utterances while simultaneously decreasing their MI-non-adherent behaviors and utterances (Table 3). When compared to recommended proficiency and competency thresholds [29], interventionists demonstrate MI proficiency in all categories (competency in some categories) with the exception of the percentage of complex reflections.

It is worth mentioning that interventionist scores did not always consistently improve from one call to another. Table 3 presents MITI scores for the three interventionists at the time of their first, middle, and last recorded calls. The scores reveal that when comparing first and last recorded calls, all improved in terms of Global Therapist Ratings for Empathy & Understanding, and for Spirit. In addition, all improved their MI Adherence. Two of the three improved in their percentages of open ended questions. One improved her ratio of reflections to questions, and one improved her percentage of complex reflections. When looking at the difference between the first and midway recorded calls, all interventionists maintained or improved scores from the first call associated with Global Therapist Ratings for Empathy & Understanding, and for Spirit. One interventionist decreased her percent of open-ended questions (91%-75%), and another decreased her ratio of reflections to questions (9:6-2:2). Finally, when comparing midway and last recorded calls scores we note that all the interventionists maintained or increased their scores associated with Global Therapist Ratings for Empathy & Understanding, and for Spirit. In addition, all stayed the same or increased their MI Adherence ratings. Two out of the three decreased their ratios of reflections to questions (18:12-11:7, and 19:9-9:14), while one improved (2:2-16:12). Also, two of the three decreased their percentages of open ended questions (75-43% and 88-86%) while one improved (50-58%).

While it is not quite clear how to make sense of the fluctuations between first and midway calls, as well as midway and last calls-particularly around ratios of reflections to questions, percentages of open ended questions, and percentages of complex reflections-what does seem most straightforward is that most of the improvements occurred over time, that is between the first and last recorded calls. Unfortunately, we did not capture enough data around the use of the suggested roadmap (for example, when interventionists stopped relying on it or using it all together) to explore the relationship between the suggested roadmap and changes or fluctuations in scores.

The supervision calls allow for almost immediate clinical feedback and supervision while the intervention calls are still fresh in the interventionist’s experience, allowing for detailed and relevant dialogue about why the interventionist chose the approach, skill, or technique, as well as what worked and did not seem to work with the particular participant. Notably, the foci of the skills and techniques explored in the calls shift over time. The co-investigator has noticed that when supervision calls began, much of the feedback and content of the calls focused on the interventionists’ use (or lack thereof) of the MI opening strategies otherwise known as OARS (open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, summaries) [1]. As time passed and the interventionists became more experienced with the calls, the content and clinical supervision appeared to focus more on exploring ambivalence and eliciting and responding to change talk. This trajectory is noteworthy, given that it follows the eight stages of learning MI that have been noted by Miller and Moyers [31].

4.2. Conclusion

As noted in the introduction of the paper, few MI study articles address the specifics of their actual interventions [10], contributing to a significant gap in our ability to assess and discuss MI fidelity and internal validity within (AMIs and “pure”) MI studies. This paper addresses the gap by providing information on the development and content of a streamlined telephone-based approach to delivering. The specifics we presented in this paper included the rationale for the study design, details of the actual intervention call, and an extended discussion of training and supervision methods, issues, and accompanying preliminary evaluations of intervention fidelity.

4.3 Practice Implications

Overall, we have demonstrated that MI, usually used in in-person settings can be successfully adapted to a telephone-based counseling session. MI can also be developed for diverse health-related scenarios. For example, in this instance we focused on CRC screening test use. MI may be adapted to conduct telephone-based counseling on medication adherence, or self-management of diabetes. As we discovered, the road-map served as a distraction to counselors. Process evaluations are, however, important to the success of the MI counseling. MI can be useful and warrants further study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the motivational interview counselors, Vikki Rompala, Ingrid Ordal and Allison Thompson and thank Kevin Grandfield and Kelly Martin for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. Guilford; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dunn C, DeRoo L, Rivera F. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: A systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96:1725–1742. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Miller WR, Benefield RG, Tonigan JS. Enhancing motivation for change in problem drinking: A controlled comparison of two therapist styles. J Consult Clin Psych. 1993;61:455–461. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Noonan W, Moyers T. Motivational interviewing: A review. J Subst Misuse. 1997;2:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Emmons K, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing in health care settings: Opportunities and limitations. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Strecher V, Wang C, Derry H, Wildenhaus K, Johnson C. Tailored interventions for multiple risk behaviors. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:619–626. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Resnicow K, DiIorio C, Soet J, Borrelli B, Ernst D, Hecht J. Motivational Interviewing in health promotion: It sounds like something is changing. Health Psych. 2002;21:444–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Borrelli B, McQuaid EL, Becker B. Motivating parents of kids with asthma to quit smoking: The PAQA project. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:659–669. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Taplin SH, Barlow WE, Ludman E, MacLehos R, Meyer DM, Seger D, Herta D, Chin C, Curry S. Testing reminder and motivational telephone calls to increase screening mammography: a randomized study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:233–242. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Dunn C. The efficacy of motivational interviewing and its adaptations. In: Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational Interviewing: preparing people for change. Guilford; New York: 2002. pp. 217–250. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ludman EJ, Curry SJ, Meyer D, Taplin SH. Implementation of outreach telephone counseling to promote mammography participation. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26:689–702. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cornuz J, Bize R. Motivating for cancer prevention. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2006;168:7–21. doi: 10.1007/3-540-30758-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McClure JB, Westbrook E, Curry SJ, Wetter DW. Proactive, motivationally enhanced smoking cessation counseling among women with elevated cervical cancer risk. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7(6):881–889. doi: 10.1080/14622200500266080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Park E, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Zorn M, Mertens AC, Gritz E, R., Li FP, Emmons KM. A process evaluation of a telephone-based peer-delivered smoking cessation intervention for adult survivors of childhood cancer: The partnership for health study. Preventive Medicine. 2006;42:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wakefield M, Oliver I, Whitford H, Rosenfeld E. Motivational interviewing as a smoking cessation intervention for patients with cancer: randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res. 2004;53(6):396–405. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200411000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bell KR, Temkin NR, Esselman PC, Doctor JN, Bombardier CH, Fraser RT, Hoffman JM, Powell JM, Dikmen S. The effect of a scheduled telephone intervention on outcome after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(5):851–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Picciano JF, Roffman RA, Kalichman SC, Rutledge SE, Berghuis JP. A telephone based brief intervention using motivational enhancement to facilitate HIV risk reduction among MSM: A pilot study. AIDS Behav. 2001;5:251–262. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rigotti NA, Park ER, Reagan S, Chang Y, Perry K, Loudin B, Quinn V. Efficacy of telephone counseling for pregnant smokers. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:83–92. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000218100.05601.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rutledge SE, Roffman RA, Mahoney C, Picciano JF, Berguis JP, Kalichman SC. Motivational enhancement counseling strategies in delivering a telephone-based brief HIV prevention intervention. Clin Soc Work J. 2001;29:291–306. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Walker DD, Roffman RA, Picciano JF, Stephens RS. The check-up: in-person, computerized, and telephone adaptations of motivational enhancement treatment to elicit voluntary participation by the contemplator. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2007;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rollnick S, Allison J, Ballasiotes S, Barth T, Butler CC, Rose GS, Rosengren DB. Variations on a theme: motivational interviewing and its adaptations. In: Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. Vol. 279. Guilford; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23:325–334. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Winawer SJ. A quarter century of colorectal cancer screening: progress and prospects. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(18 Suppl):6S–12S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rogers CR. The necessary and sufficient conditions for therapeutic personality change. J Consult Psych. 1957;21:95–103. doi: 10.1037/h0045357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Miller WR, Rollnick S. Talking Oneself into Change: Motivational Interviewing, Stages of Change, and Therapeutic Process. J Cogn Psychother. 2004;18:299–308. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Smith LS, Amrhein PC, Brooks AC, Kenneth MC, Levin D, Schreiber EA, Travaglini LA, Nunes EV. Providing live supervision via teleconferencing improves acquisition of motivational interviewing skills after workshop attendance. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:163–168. doi: 10.1080/00952990601091150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR. The motivational interviewing treatment integrity (MITI) code. 2003 Version 2.0. Available: ( http://casaa.unm.edu/download/miti.pdf.) Retrieved September 27, 2004.

- [28].Miller WB. Motivational Interviewing Skills Code (MISC): Coder’s manual. University of New Mexico; 2000. Unpublished manual. Available at: http://www.motivationalinterview.org/ [Google Scholar]

- [29].Madson MB, Campbell TC. Measures of fidelity in motivational enhancement: A systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Madson MB, Campbell TC, Barrett DE, Brondino MJ, Melchert TP. Development of Motivational Interviewing Supervision and Training Scale. Psych Addict Behav. 2005;19:303–310. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Miller WR, Moyers TB. Eight stages in learning motivational interviewing. J Teach Addict. 2007;5:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psych. 2004;72(6):1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]