Abstract

Background

Providing breast cancer patients with needed information and support is an essential component of quality care. This study investigated racial/ethnic variation in information received and in availability of peer support.

Methods

1766 women diagnosed with non-metastatic breast cancer and reported to the Los Angeles County, SEER registry from June 2005–May 2006 were mailed a survey after initial treatment. Among accrued cases, 96.2% met eligibility criteria (n=1698), and 72.0% completed the survey. Race/ethnicity categories were white, African American, and Latinas (two categories indicating low or high acculturation, determined by the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics). Outcomes included receipt and need for treatment- and survivorship-related information, difficulty understanding information, and support from women with breast cancer.

Results

More women reported receiving treatment-related than survivorship-related information. After adjusting for sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment factors, a higher percentage of low acculturated Latina women desired more information on treatment-related and survivorship-related issues (p<.001). Significantly more Latina low acculturated women than white women reported difficulty understanding written materials, with 74.5% requiring help from others. A higher percentage of all minority groups compared to whites, reported no contact with other women with breast cancer (p< 0.05) and, reported less contact through family/friends (p< 0.05). Women rated the benefit of talking to other women high, particularly with emotional issues.

Conclusions

Continued efforts to provide culturally appropriate information and support needs to women with breast cancer are necessary to achieve quality care. Latinas with low acculturation reported more unmet information and care support needs than other racial/ethnic groups.

Introduction

Informing patients with cancer about treatment and survivorship issues is a key component of quality of care. The relationship between satisfaction with information received and quality of life outcomes in breast cancer has been documented in previous research.1–4 Difficulty in accessing needed information can have a negative impact on emotional, functional, and social well-being,1 vitality,2 and coping with the diagnosis.5 In addition, patients who are satisfied with the information they receive are more likely to comply with medical recommendations and treatments1,6 and have better communication with family members.7 While the mechanisms by which information impacts health outcomes after breast cancer requires further study, some suggest that information may enhance a woman's perception of competence in dealing with her illness.1

A growing body of literature has described the information and support needs for women following a breast cancer diagnosis.2,8,9 Most studies have focused on information needs during the diagnosis and treatment phase9 with less emphasis on information needs during survivorship.2,10 A number of studies have concluded that breast cancer patients are often dissatisfied with the extent to which their information needs are addressed, both in terms of the content and source of delivery.1,8,10,11 There is some evidence that physicians provide less informational support to minority women with breast cancer.12,13 For the most part, however, the current literature is limited by a paucity of studies with adequate minority representation.1,2,9

While most women prefer to receive their cancer-related information from health care providers,12,14 other interpersonal sources, such as professionally-led or peer-led support groups and one-on-one contact with other women who have had breast cancer, can augment what information provided by health professionals.9 Although some studies have found less access to, and use of, support groups among racial/ethnic minority survivors than Whites,15–17 patients’ wishes for more peer support opportunities have not been adequately investigated in most studies.

To address gaps in the literature concerning racial/ethnic differences in information and support needs of women with breast cancer, we used a large diverse population-based sample of women with breast cancer to answer three questions: (1) Do treatment and survivorship information needs differ by race/ethnicity, (2) Are there racial/ethnic differences in perceived difficulty understanding information, and (3) Does support received from other women with breast cancer differ by race/ethnicity?

Research Methods

Study Population

Los Angeles County resident women aged 20–79 years diagnosed with primary ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) or invasive breast cancer (Stage I–III) from June 2005 through May 2006 were eligible for sample selection for the study. Women were excluded if they could not complete a questionnaire in English or Spanish. Latina and African-American patients were over-sampled.

Sampling and Data Collection

Patients were selected shortly after diagnosis as they were reported to the Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program (LA-CSP) - the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Cancer Registry for Los Angeles County. This method of selection can yield a sample representative of the County population. We selected all African American women based on demographic information from the treating hospitals. Because Latina status is not accurately collected by the treating hospital at the time of diagnosis we used an alternative sampling strategy to increase the representation of Latina women in the study. We selected all women who were designated as Hispanic by the hospital as well as all women whose surname indicated a high probability of being Latina based on a list generated from the 1980 U.S. Census.18 We then selected an approximately 11% random sample of the remaining white (non-Spanish surnamed) patients. Asian women were excluded because these women were already being enrolled in other studies.

Physicians were notified of our intent to contact patients followed by a mailing of an introductory letter, survey materials, and $10 cash gift to subjects. The patient survey was translated into Spanish using a standard approach.19 All patients who were likely to be Latina based on hospital or surname-based census information were sent bilingual materials. The Dillman survey method was employed to encourage response.20 The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Michigan and the University of Southern California. The research followed established protocols of the SEER registries in Los Angeles for population-based research.

Over the study period, 1766 eligible patients were accrued including 796 Latinas (based on the registry’s Hispanic variable), 459 African-Americans, 478 whites, and 33 patients with other racial categories. The accrued sample included approximately two thirds of the Latina and African-American patients and 14% of non-Latina white patients diagnosed with breast cancer in Los Angeles County during the study period. After initial patient contact, another 68 patients were excluded because 1) a physician refused permission to contact (7); 2) the patient did not speak English or Spanish (8), 3) the patient was too ill to participate (30), and 4) the patient denied having cancer (23). Of the 1,698 patients included in the final accrued sample 179 (10.5%) could not be located or contacted and 296 (17.5%) patients located and contacted did not participate in the survey. Thus, a final sample of 1224 (72.0%) completed the survey (97.8% of whom completed a written survey and 2.2% completed a complete telephone survey).

Information from the survey was merged to SEER data for all patients in the final sample. An analysis of non-respondents vs. respondents showed that there were no significant differences by age at diagnosis, race, or Hispanic ethnicity. However, compared to respondents, non-respondents were less likely to have ever married (18.9% vs. 25.2 %, p=.005); were more likely to live in lower SES census tracts (48.6% vs. 40.2%, p=.030); were more likely to have Stage II or III disease (45.7% vs. 40.3% p<.001), and were less likely to have received breast conserving surgery (56.0% vs. 64.4%, p<.001).

Measures

Information needs

To determine the information needs of women with breast cancer, study participants completed a series of questions addressing receipt of and desire for more information on treatment and survivorship-related issues. The survey included three treatment-related items (managing recovery after surgery, side effects of radiation, and side effects of chemotherapy) and four survivorship-related issues items (effects of breast cancer/treatment on nutrition and/or diet, sexual function, relationships with spouse/partner, and feelings of anxiety/depression). For each item, respondents indicated if they had received the information and if they would have liked more information from doctors or their staff. The items relating to radiation and chemotherapy were restricted to those women who received the treatment of question. Additional items assessed if women had difficulty understanding information (yes/no), needed someone else to help read written materials (yes/no), and knew who to ask questions of regarding the material (yes/no).

Peer support opportunities

Respondents were asked to indicate whether or not they talked with other women with breast cancer and if so; if a doctor or staff member made the arrangements, if they joined a support group, or if they talked with a family member or friend with breast cancer. Additionally, women who reported that they talked with other breast cancer peers were asked to endorse various positive and/or negative consequences of the exchange including whether talking: (a) helped make treatment decisions, (b) helped emotionally, (c) made them doubt their treatment decisions, (d) helped them to know what to expect, (e) made them scared or anxious about treatment, (f) helped them cope with the challenges and side effects of treatment, or (g) wonder why they did not get the same treatment.

Sociodemographic characteristics

We created a variable combining survey information on race, ethnicity, and language. Women were first asked to indicate their race (White, black/African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, or some other race), and if they were Hispanic/Latina (yes/no). Women were additionally asked if they spoke Spanish. To determine the language preference we used the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH Manual), which has been shown to be an efficient, reliable, and valid measure to identify Latinas with low or higher acculturation.19 The four items indicate the preference for English or Spanish in different contexts (usually read/speak, think, use at home, use with friends) on a five point scale (from “English only” to “Spanish only”). We aggregated across the five items to calculate a mean preference score. Fifty five percent of the Latina patients (n=332) scored 4 or more on the five-point scale (strongly preferring Spanish across contexts). Race/ethnicity was thus divided into four categories (White, African American, Latina-English Preference (Latina-EP), and Latina-Spanish Preference (Latina-SP). Compared to Latinas who scored lower (n=271), Latinas-SP (less acculturated) were much more likely to be foreign born (99.4% vs. 35.2%). Because there were few African American and white women who spoke Spanish, we included language preference as subcategories only for Latina women.

Additional factors included in analyses were age at the time of breast cancer diagnosis, level of education (< H.S, H.S diploma, > H.S diploma), marital status (currently married/domestic partner, divorced/widowed/separated, never married), number of co-morbidities (0,1, 2 or more), surgical procedure (lumpectomy or mastectomy), radiation therapy (yes/no), and chemotherapy (yes/no). Information on breast cancer stage was obtained via SEER data using criteria set forth by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (0, I, II, III). All women with Stage IV cancer were deleted from this analysis.

Analysis Plan

All analyses were conducted using SAS V. 9.1.3 Programming language. Descriptive statistics were used to generate sample characteristics overall and by race/ethnicity. Bivariate associations between race/ethnicity and all sociodemographic, treatment, survivorship and support-related factors were tested using Wald’s Chi-square test for association. Logistic regression models were used to determine adjusted associations between race/ethnicity and treatment and survivorship-related factors. Because all hypotheses were determined a priori, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons. However, a p-value of <0.001 can be considered statistically significant by the most conservative methods of controlling for multiple comparisons. Point estimates were adjusted for design effects by using a sample population weight that accounted for differential selection by race, ethnicity, and nonresponse.

Results

The final analytic sample included 1137 women for which there was complete information on all covariates of interest. Table 1 displays the sample characteristics overall and by race/ethnicity. The mean age was 56.9 years, and the racial/ethnic distribution was as follows: white (27.7%), African American 25.7%), Latina-EP (21.4%), and Latina-SP (25.2%). There were significant differences by race/ethnicity across all demographic characteristics, number of co-morbidities, and treatment course variables as presented in the Table (all p values < 0.05; except breast cancer stage, p=0.186 and receipt of radiation, p=0.177). African American and Latina women were more likely to be less than 50 years at diagnosis. Latina-SP women were far more likely to have less than a high school education, and African American women were less likely to be married. Latinas were more likely to receive mastectomy than other race/ethnic groups. All minority groups were more likely to receive chemotherapy than whites.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics Overall and by Race/Ethnicity/Language (N=1137)

| Total (N=1137) | White (N=345) | African American (N=308) | Latina –English Preferred | Latina -Spanish Preferred | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Factors | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) |

| Age | |||||

| < 50 years | 29 | 21 | 29 | 35 | 32 |

| 50–70 years | 54 | 60 | 53 | 47 | 55 |

| > 70 years | 17 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 13 |

| Education | |||||

| < H.S diploma | 26 | 4 | 9 | 22 | 72 |

| H.S diploma | 18 | 18 | 16 | 20 | 19 |

| >H.S | 55 | 78 | 75 | 58 | 9 |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Currently married/partner | 56 | 62 | 38 | 60 | 63 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 33 | 29 | 47 | 28 | 29 |

| Never married | 11 | 9 | 15 | 12 | 9 |

| Clinical Factors | |||||

| # of Comorbidities | |||||

| 0 | 42 | 44 | 34 | 48 | 44 |

| 1 | 29 | 33 | 29 | 26 | 28 |

| ≥2 | 29 | 23 | 38 | 27 | 28 |

| Breast Cancer Stage | |||||

| 0 | 20 | 20 | 17 | 19 | 22 |

| I | 38 | 44 | 38 | 35 | 32 |

| II | 30 | 26 | 31 | 32 | 33 |

| III | 12 | 10 | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| Treatment Factors | |||||

| Surgery | |||||

| Lumpectomy | 71 | 76 | 75 | 65 | 66 |

| Mastectomy | 29 | 24 | 25 | 35 | 34 |

| Radiation therapy | |||||

| Yes | 67 | 68 | 72 | 67 | 63 |

| No | 33 | 32 | 28 | 33 | 37 |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| Yes | 50 | 40 | 51 | 55 | 57 |

| No | 50 | 60 | 49 | 45 | 43 |

Chi-square test for association; age (p=0.003), number of co-morbidities 0.001, breast cancer stage p=0.186, surgery (p=0.007), radiation (p=0.177), all else <0.001

percents in the table are unweighted

Table 2 shows the percentage of women who reported receiving information and wanting more information across treatment-related and survivorship-related concerns. Overall, a higher percentage of women reported receiving information on treatment-related than survivorship-related issues. At least 80% of women endorsed receipt of information across treatment-related content areas and generally there were no differences by race/ethnicity. There were, however, greater differences in reported receipt of information about survivorship issues, with a higher percentage of African Americans reporting receipt of information in most content areas compared to other ethnic/racial subgroups. With regard to wanting more information, significant race/ethnic differences (all p values < 0.001) were apparent across all treatment and survivorship-related concerns, with a higher percentage of Latina-SP desiring more information on all issues. Finally, in a sensitivity analysis comparing our results to those women who were still receiving radiation and/or chemotherapy, the observed pattern of racial/ethnic differences remains the same (e.g., a higher percentage of Latina-SP women desired more information on treatment-related issues).

Table 2.

Percent of Women Who Received Treatment and Survivorship-Related Information, and Wanting More Information by Race/Ethnicity

| % who received information | % who wanted more information | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | White | African American | Latina – English Preferred | Latina – Spanish Preferred | Overall | White | African American | Latina – English Preferred | Latina – Spanish Preferred | |

| Treatment related issues | ||||||||||

| Surgical recovery | 87 | 89 | 87 | 86 | 81 | 35 | 28 | 41 | 39 | 65 |

| Radiation* | 86 | 86 | 82 | 91 | 85 | 35 | 29 | 43 | 36 | 64 |

| Chemotherapy† | 97 | 98 | 95 | 95 | 94 | 44 | 36 | 43 | 49 | 70 |

| Survivorship related issues | ||||||||||

| Anxiety/depression | 61 | 59 | 68 | 58 | 63 | 44 | 37 | 47 | 50 | 68 |

| Relationships‡ | 39 | 34 | 59 | 51 | 44 | 41 | 35 | 48 | 45 | 65 |

| Sexual function | 32 | 28 | 41 | 43 | 37 | 33 | 29 | 34 | 39 | 50 |

| Nutrition | 52 | 49 | 63 | 57 | 54 | 53 | 49 | 53 | 59 | 70 |

Restricted to those who received radiation therapy

Restricted to those who received chemotherapy

Restricted to those who are married or living with someone

significant p-values: received information: recovery (p=0.047), nutrition (p=0.004), relationship (p<0.001), sexual function (p=0.002) wanted more information: all p’s <0.001

percents are weighted to account for differential selection by race, ethnicity, and nonresponse.

Table 3 shows adjusted odds ratios for desire for more treatment and survivorship information by sociodemographic factors, controlling for clinical and treatment-related factors. Race/ethnicity remained significant across all treatment and survivorship content areas, with Latina-SP women consistently wanting more information across all areas independent of other factors. For example, Latina women with low acculturation were much more likely to desire more information about relationships than their white counterparts (OR 4.84, 95% CI 2.31–10.12). In addition to racial differences, older women (50–70; and >70 yrs) were less likely to want more information on sexual function than those < 50 years old (OR for 50–70 yrs 0.53, 95% CI 0.38–0.75; OR for >70 yrs 0.10, 95% CI. 0.05–0.20). Older women also were less likely to want more information about nutrition, relationships, and anxiety and depression. The impact of level of education was mixed. Those with a high school diploma but no college compared to those without a high school diploma were less likely to want additional information in three of the content areas (i.e., surgical recovery, radiation side effects and nutrition). However, those with at least some college were more likely to want additional information on nutrition and sexual function than those with less than a high school education. Married women and those who were previously married were more likely to desire additional information on sexual function than women who were never married; however, they were less likely to want more information on nutrition.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds of Wanting More Information by Sociodemographic Characteristics, Controlling for Clinical, and Treatment Related Factors*

| Surgical Recovery | Radiation† | Chemotherapy‡ | Nutrition | Sexual function | Relationships | Depression /anxiety | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| <50 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 50–70 | 0.8[0.57,1.13] | 1.08[0.70,1.66] | 0.93[0.60,1.43] | 0.74[0.53,1.03] | 0.53[0.38,0.75] | 0.60[0.39,0.93] | 0.70[0.50,0.97] |

| >70 | 1.1[0.69,1.76] | 1.09[0.61,1.95] | 1.33[0.62,2.86] | 0.44[0.28,0.69] | 0.10[0.05,0.20] | 0.11[0.05,0.25] | 0.42[0.27,0.67] |

| X2 | 0.131 | 0.942 | 0.572 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| African American | 1.67[1.13,2.47] | 1.65[1.02,2.65] | 1.31[0.78,2.20] | 1.18[0.80,1.74] | 1.42[0.92,2.18] | 1.41[0.73,2.69] | 1.35[0.92,1.97] |

| Latina- English Preferred | 1.53[0.99,2.35] | 1.20[0.69,2.09] | 1.52[0.88,2.63] | 1.54[1.00,2.38] | 1.52[0.95,2.44] | 1.36[0.74,2.47] | 1.65[1.08,2.52] |

| Latina- Spanish Preferred | 4.54[2.71,7.58] | 3.07[1.62,5.83] | 2.83[1.41,5.71] | 3.02[1.79,5.07] | 3.76[2.1,6.76] | 4.84[2.31,10.12] | 4.07[2.42,6.84] |

| X2 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.028 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Education | |||||||

| < H.S | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| H.S diploma | 0.61[0.36,1.00] | 0.31[0.16,0.59] | 0.52[0.26,1.05] | 0.63[0.38,1.04] | 1.13[0.61,2.06] | 1.11[0.52,2.34] | 0.85[0.51,1.41] |

| Some college/Technical | 0.94[0.59,1.51] | 0.6[0.34,1.07] | 0.57[0.29,1.11] | 1.34[0.84,2.13] | 2.02[1.14,3.57] | 1.95[0.96,3.98] | 1.27[0.79,2.03] |

| X2 | 0.044 | <0.001 | 0.158 | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.038 | 0.075 |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Never married | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | N/A | 1.0 |

| Currently married | 0.84[0.55,1.28] | 1.06[0.59,1.88] | 0.83[0.49,1.40] | 0.61[0.39,0.95] | 2.05[1.28,3.26] | 0.91[0.60,1.40] | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 0.73[0.46,1.15] | 1.23[0.67,2.27] | 0.85[0.47,1.53] | 0.53[0.33,0.84] | 1.02[0.61,1.70] | 0.87[0.55,1.37] | |

| X2 | 0.369 | 0.673 | 0.778 | 0.026 | <0.001 | 0.823 |

Adjusted for age, race, education, marital status, # of comorbidities, breast cancer stage and treatment;

Restricted to women who received radiation therapy;

Restricted to women who received chemotherapy percents are weighted to account for differential selection by race, ethnicity, and nonresponse.

N/A re: desire for more information on “relationships,” was restricted to those who were married or with a partner

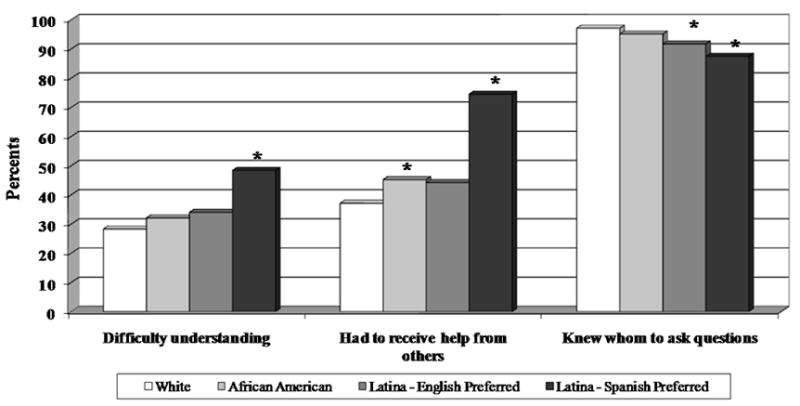

Figure 1 shows the proportion of patients who reported challenges to understanding care and support information. About 48% of Latina-SP women reported some difficulty understanding the information presented, and 75% received help from others. While overall 90% of women reported knowing whom to ask regarding questions, Latina women as a whole were significantly less likely to know than whites.

Figure 1.

Understanding information on breast cancer treatment and receiving help from others, by race/ethnicity

Note: Chi-Square test for overall significance p<0.001for all variables

* indicates statistically significant differences as compared to White women

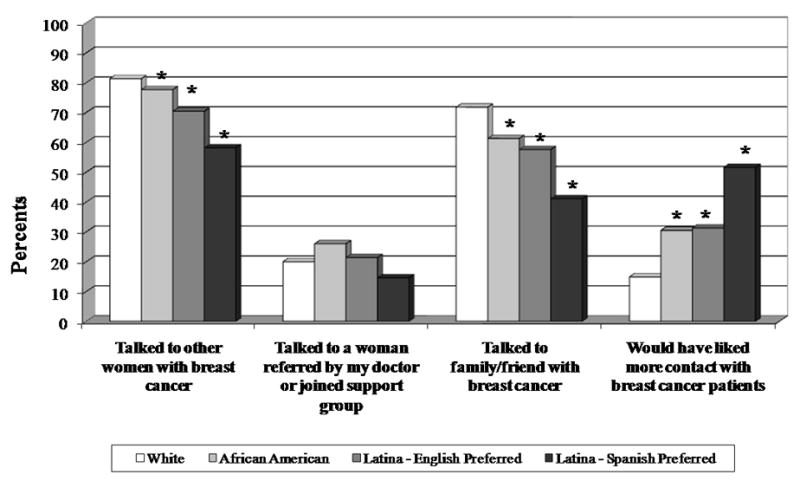

Figure 2 shows the proportion of study participants who talked with other women, and whether that happened via the medical care system or within their own social network. Latina-SP women (58.2%) were much less likely to talk with other women with breast cancer than white women (81.3%) (p < 0.001). Latina-EP and African American women were also less likely than whites to talk with other women with breast cancer. Overall 20% of women were referred by their medical care system to a support group and/or to an individual with breast cancer; and there was no significant variation by race/ethnicity. A much higher percentage of women reported talking to a family member or friend with breast cancer. African American and Latinas were, however, significantly less likely to report such an exchange compared to white women; Latina-SP were the least likely among the racial/ethnic groups. Finally, minority women were more likely than white women to desire more contact with breast cancer patients, particularly Latina-SP women (51.6% vs. 14.9%, p<.001).

Figure 2.

Opportunity to talk to other women with breast cancer, by race/ethnicity

Note: Chi-Square test for overall significance p<0.001 for all variables; except “Talked to a woman referred by my doctor or joined support group” p<0.128

* indicates statistically significant differences as compared to White women

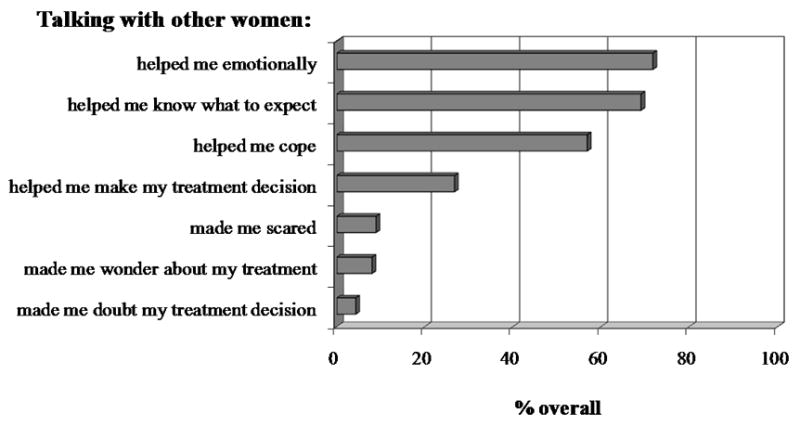

Figure 3 shows women’s perceptions of the potential positive and negative consequences of talking with other women with breast cancer (among those who had any contact). Three benefits of talking with other women were endorsed by over 50% of the sample: “helped me emotionally,” “helped me know what to expect,” and “helped me cope”. Each of the potential negative consequences was endorsed by fewer than 10% of the women, that is: “made me scared,” “made me wonder about my treatment,” and “made me doubt my treatment decision.”

Figure 3.

Experiences talking with other women with breast cancer

Discussion

The results of this population-based study provide further insight into the information and support needs of women with breast cancer, and the extent to which they differ across racial/ethnic subgroups. Overall most women with breast cancer, regardless of race/ethnicity, reported receiving substantial information on how to manage the side effects of treatment. As in other studies, substantially fewer women reported receiving information on common concerns related to survivorship.2,10 A considerable proportion of women wanted additional information on both treatment-related and survivorship-related information. The type of information desired varied by patient subgroup in logical ways. For example, younger women desired more information on sexual functioning and relationships. These findings are consistent with other studies that report women with breast cancer desiring more information in many content areas9 and report less exposure to survivorship-related than treatment-related concerns.2,10,21

Particularly striking in our study are the racial/ethnic differences in perceptions of unmet need for information and peer support. Latinas with low acculturation appear to have the greatest unmet need for information support after controlling for other clinical and sociodemographic factors, including level of education, and the greatest unmet need for contact with other women with breast cancer.

There are a number of explanations for the higher unmet need for information among Latinas with low acculturation. The first is that Latinas with low acculturation may not have access to information, particularly information about relationships, sexual health, and nutrition, or may not be aware that such information is available. Medical practices caring for Latinas with low acculturation may not have trained staff available, including social workers and dieticians, whose role it is to help provide information on relationships and nutrition. Additionally, if the information was only available in English, it may have presented a barrier to Latinas with low acculturation. We found Latina-SP women reported needing the most help with understanding information related to their breast cancer. This finding is likely related to the fact that only about half of Latina-SP women reported that their physician and/or someone at the medical clinic spoke Spanish. Previous studies have found that patients whose main spoken language is not English have more difficulty communicating with their physicians,22 including Latina breast cancer survivors.23 Therefore, even if information had been provided, there may have been problems understanding or processing the information among Latina-SP women that led them to report desiring more information (or perhaps more well communicated information).

Another possible explanation for our findings on unmet information needs is that the information that was provided may not have been sensitive to cultural issues important to less acculturated Latinas. Others have shown that there is a need to provide culturally appropriate information related to health issues1,15,24,25 and failure to account for culture and linguistic issues can result in less satisfaction with information provided. In ongoing work by our research team, we have found that less acculturated Latinas report significantly higher levels of decision dissatisfaction and regret related to their treatment decision making than other groups, suggesting that the desire for more information found in this study may be associated with decision outcomes.

Finally, Latinas with low acculturation may have greater need for information on particular topics than other women. That is, even when given adequate amounts of high quality information, a greater level of need could lead to higher levels of unmet need. It is possible that concerns about recurrence, for example, are greater among Latinas and that more information about managing such concerns within the family might therefore be helpful. Ongoing research addressing concerns about recurrence among women of different racial and ethnic groups may help to clarify the relationships between concerns about recurrence and the need for informational and peer support.26

Some studies have suggested that ethnic minorities prefer to receive information through interpersonal contact rather than printed information.12 Given the constraints on time in the physician office, another avenue for women to gain information is to talk with other women with breast cancer. This study provided further evidence that most women who had an opportunity to talk with peers found it helpful and very few found it counter-productive. Patient peer-support was particularly helpful in the area of emotional well-being and coping. These results are consistent with those of Ashing-Giwa et al., 23 who found that while Latina survivors received most of their support from family and friends, talking with other women with breast cancer provided a unique level of emotional support not available from other sources. Despite the benefits of peer support, relatively few women reported that their health care provider arranged for such a contact. For example, only about 18% of Latina women talked to other women with breast cancer referred by their doctor and/or joined a support group.

Limitations

Study findings are limited by study design that did not allow us to examine information needs over time. Since these were incident cases surveyed at the time of diagnosis and initial therapy (mean time from diagnosis to survey completion of 9.2 months), longer term needs were not able to be assessed. The results are also limited by the number of treatment and survivorship concerns assessed. There is a need to conduct multi-ethnic longitudinal evaluations of information and support needs of women following breast cancer as well as assess the impact of changing information needs on health outcomes. A better understanding of the longitudinal information needs will help in the design of more effective interventions. In addition, the generalizability of our findings regarding racial/ethnic differences is limited to those groups included in the sample (e.g., we were unable to include Asian Americans). Recall may have biased results. Women who were experiencing worse outcomes may recall not receiving sufficient amounts of information or wanting more information compared to their healthier counterparts. Finally, the origin of the Latina population in Los Angeles County is predominantly from Mexico and Central America. The U.S. Hispanic population is a diverse population, and it may not be appropriate to generalize our findings to Latinas from other cultural backgrounds.

Implications

Our findings suggest that providing treatment and survivorship support for patients with breast cancer is challenging. Having written materials available in appropriate languages is one way to help address some of the challenge by providing information that can be taken home and reviewed in a more relaxed environment. Overcoming disparities in informational support will also require providing materials in a culturally relevant and sensitive manner.27 When possible using professional interpreters, new interpreter technologies, or integrating community workers into practices could also be beneficial.28,29

More challenging to clinicians and their staff is to provide continuity in support beyond the immediate treatment period and into survivorship. Cancer survivorship support cannot be viewed in isolation from care and support needs for other health conditions. Cancer survivors need both continuity of care and integrated approaches to managing their cancer concerns along with other medical problems. The wide variation in follow-up of patients with cancer in the community underscores the need to design and evaluate collaborative care models between specialists and primary care.

A third strategy is to build more patient peer-support opportunities. This may be a missed clinical opportunity especially for ethnic minority patients who appear to be particularly prone to unmet need in this area. More structured support-group referral programs could be integrated into provider offices and/or incorporated into the initial surgical consultation. For Latinas with low acculturation, ensuring these referrals are to Spanish-speaking groups would be important. A variety of directions are possible, from patient support groups to trained patient support volunteers to facilitating more informal arrangements. Indeed, some patients in our study reported that “clinic friends” were an important source of information and support during treatment. More research will be required to evaluate interventions based on these strategies to address information and care support needs of patients with cancer into the survivorship period.

In conclusion, the findings from this population-based study have implications for clinical practice and future research. One of the strengths of this study was the use of a large population-based sample of breast cancer survivors with adequate representation of Latina (both low and high acculturated) and African American survivors. Latina breast cancer patients, specifically those with low acculturation, reported more unmet information and care support needs than other racial/ethnic groups. Continued efforts to provide desired and culturally and linguistically appropriate information and support needs to women with breast cancer are necessary to achieve quality care.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA109696) to the University of Michigan. Dr. Katz was supported by an Established Investigator Award in Cancer Prevention, Control, Behavioral and Population Sciences from the National Cancer Institute (K05 CA111340). The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, contract N01-PC-54404 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement 1U58DP00807-01 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

References

- 1.Arora N, Johnson P, Gustafson D, McTavish F, Hawkins RP, Pingree S. Barriers to information access, perceived health competence, and psychosocial health outcomes: test of a mediation model in a breast cancer sample. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griggs JJ, Sorbero MES, Mallinger JB, et al. Vitality, mental health, and satisfaction with information after breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesters I, van den Borne B, DeBoer M, Pruyn J. Measuring information needs among cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;43:255–264. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora N, Finney Rutten LJ, Gustafson DH, Moser R, Hawkins RP. Perceived helpfulness and impact of social support provided by family, friends and health care providers to women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:474–486. doi: 10.1002/pon.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Der Molen B. Relating information needs to the cancer experience: 1. Information as a key coping strategy. Eur J Cancer Care. 1999;8:238–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.1999.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derdiarian A. Information needs of recently diagnosed cancer patients: a theoretical framework. Cancer Nurs. 1987;10:107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds PM, Samson-fisher RW, Poole AD, Harker J, Byrne MJ. Cancer and communication: information-giving in an oncology clinic. Br Med J Clin Res Ed. 1998;282:1449–1451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6274.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raupach JCA, Hiller JE. Information and support for women following the primary treatment of breast cancer. Health Expect. 2002;5:289–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2002.00191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutten LJF, Arora NK, Bakos AD, et al. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980–2003) Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:250–261. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray RE, Fitch M, Greenberg M, Hampson A, Doherty M, Labrecque M. The information needs of well, longer-term survivors of breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33:245–255. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salminen E, Vire J, Poussa T, Knifsund S. Unmet needs in information flow between breast cancer patients, their spouses, and physicians. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:663–668. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maly RC, Leake B, Silliman RA. Health care disparities in older patients with breast carcinoma: Informational support from Physicians. Cancer. 2003;97:1517–1527. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siminoff LA, Graham GC, Gordon NH. Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics: Disparities in information-giving and affective behaviors. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray RE, Goel V, Fitch MI, Franssen E, Labrecque M. Supportive care provided by physicians and nurses to women with breast cancer: Results from a population-based survey. Support Cancer Care. 2002;10:647–652. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aziz NM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivorship research among ethnic minority and medically underserved groups. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:789–801. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.789-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Napoles-Springer A, Ortiz C, O’Brien H, Diaz-Mendez M, Perez-Stable EJ. Use of cancer support groups among Latina breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen JE, Goldstein MS, Lee JH, Breen N, Rowland JH. Use of health related and cancer-specific support groups among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2007;109:2580–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Word D, Perkins JR. Building a Spanish surname list for the 1990’s – a nefw approach to an old problem. US Census Bureau, Technical Working Paper No. 13; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marin G, Sabogal F, Vanoos Marin B, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9:183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anema MG, Brown BE. Increasing survey responses using the total design method. J Contin Educ Nurs. 1995;26:109–114. doi: 10.3928/0022-0124-19950501-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallinger JB, Griggs JJ, Shields CG. Patient-centered care and breast cancer survivors' satisfaction with information. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Katz SJ, et al. Is language a barrier to the use of preventative services? J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:472–477. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla GV, Bohórquez DE. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Latina women. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;24:19–52. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore RJ, Burtow P. Culture and Oncology: Impact of Context Effects. New York, NY: Kluwer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fatone AM, Moadel AB, Foley FW, et al. Urban voices: the quality-of-life experience among women of color with breast cancer. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2007;5:115–125. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507070186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, Hamilton A, Katz SJ. Racial/ethnic differences in quality of life and fear of recurrence after diagnosis of breast cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008 June; [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watts T, Merrell J, Murphy F, et al. Breast health information needs of women from minority ethnic groups. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47:526–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corkery E, Palmer C, Foley ME, Schechter C, Frisher L, Roman SH. Effect of a bicultural community health worker on completion of diabetes education in a Hispanic population. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:254–257. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palos G. Cultural Heritage: cancer screening and early detection. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1994 May;10:104–13. doi: 10.1016/s0749-2081(05)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]