Abstract

Telomerase is responsible for replication of the ends of linear chromosomes in most eukaryotes. Its intrinsic RNA subunit provides the template for synthesis of telomeric DNA by the reverse-transcriptase (TERT) subunit and tethers other proteins into the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. We report that a phylogenetically conserved triple helix within a pseudoknot structure of this RNA contributes to telomerase activity but not by binding the TERT protein. Instead, 2′-OH groups protruding from the triple helix participate in both yeast and human telomerase catalysis; they may orient the primer-template relative to the active site in a manner analogous to group I ribozymes. The role of RNA in telomerase catalysis may have been acquired relatively recently or, alternatively, telomerase may be a molecular fossil representing an evolutionary link between RNA enzymes and RNP enzymes.

The ends of eukaryotic linear chromosomes are capped by specialized DNA–protein complexes called telomeres. Telomeres confer protection from degradation and chromosome fusion and provide a means for complete replication of chromosomes by telomerase1–3. Telomerase contains an RNA subunit, TER (called Tlc1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae4), a catalytic reverse transcriptase, TERT (called Est2 in S. cerevisiae5), and additional accessory protein factors. Different from other reverse transcriptases, telomerase is specialized in repetitively copying a short sequence within its RNA subunit to add DNA telomeric repeats to the end of the chromosome6.

The size and sequence of telomerase RNAs vary dramatically among ciliates (~160 nucleotides (nt)), vertebrates (~500 nt) and yeast (~930–1600 nt). This divergence in RNA size and sequence makes it challenging to identify common structural motifs for telomerase RNAs. Through phylogenetic comparative analysis, the secondary-structure models of both ciliate and vertebrate telomerase RNAs have been well established7,8. These models have led to experiments providing mechanistic insight into telomerase action. In contrast, there is still divergence in proposed structural models of the telomerase RNA of S. cerevisiae, a particularly valuable model organism for studying telomerase function in vivo.

In addition to providing an internal template, other identified functions of telomerase RNAs include providing the template boundary for reverse transcription, contributing to repeat addition processivity and providing a scaffold for accessory protein subunits9–15. It has been shown that Tetrahymena TERT can copy a separate template RNA strand, but only if the other portion of the RNA is still provided in trans, one explanation for this being that the nontemplate portion of the RNA might contribute directly to catalysis16.

Here we show that the core region of the S. cerevisiae Tlc1 RNA contains a conserved triple-helix structure. Disruption of this triple helix causes decreased telomerase activity in vitro and telomere shortening in vivo, with no change in the binding affinity of the protein subunit, TERT. Furthermore, we find that the triple-helix structure is in close proximity to the 3′ end of a telomeric primer bound to the template, which must lie in the active site of telomerase. Through functional group substitution analysis, we demonstrate that one or more 2′-OH groups in the triple-helix regions of both yeast and human telomerase RNAs are important for catalysis. We propose that these 2′-OH groups orient the primer-template helix relative to the active site, a mechanism commonly used in ribozymes17,18.

RESULTS

Yeast telomerase RNA core structure

Models recently proposed by four groups differ in the fold of the core region of the telomerase RNA, a region that contains the template and binds to the reverse-transcriptase subunit15,19–21 (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). To decipher the correct secondary structure of the core region, we used the recently developed in vitro yeast telomerase activity assay to test a series of 12 scanning mutants covering the whole 96-nt core region in the context of a truncated but active version of Tlc1 called Mini-T (500)10. In each of these mutants, designated 1–12, eight consecutive nucleotides were mutated to their Watson-Crick complementary bases (Fig. 1a). The reconstituted telomerase activities of mutants 1, 9 and 10 were approximately 100% of the wild-type activity, indicating that the mutated nucleotide sequences are functionally dispensable, and therefore these nucleotides might lie in less-structured loop regions in the telomerase RNA (Fig. 1b). Notably, the rest of the 12 mutants retained only 2–12% of the wild-type telomerase activity, suggesting that the mutated nucleotides in these mutants might participate in a structure. After superimposing the mutational analysis results on the four proposed models of the core region, we found that the activity data best fit the model of Lin et al.19—an RNA pseudoknot structure that resembles those in ciliate and vertebrate telomerase RNA core regions.

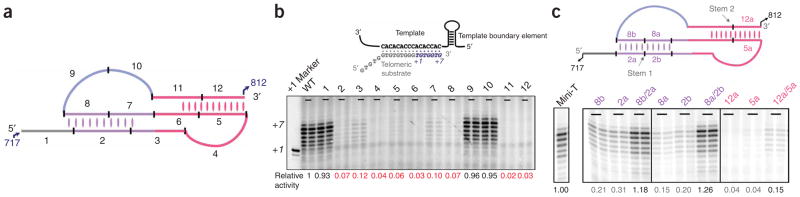

Figure 1.

The core region of the S. cerevisiae telomerase RNA has a conserved pseudoknot RNA structure. (a) One of the four secondary-structure models (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for all four models) of the S. cerevisiae telomerase RNA core region. Numbers 1 to 12 refer to twelve scanning mutants made to test the four models. In each of these mutants, eight consecutive nucleotides were mutated to their Watson-Crick complementary bases. The 5′ and 3′ end nucleotides are labeled according to the numbering system in ref. 19. (b) In vitro telomerase activities of the 12 scanning mutants. A schematic illustration of the alignment of telomeric DNA substrate with the template region of the telomerase RNA is shown above. Numbers at the bottom of the gel denote the relative activity of each mutant calculated based on the two independent reactions shown. The +1 marker was the 15-nt single-stranded telomeric primer extended by 1 nt with the addition of [33P]ddTTP and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase. WT, wild type. (c) Compensatory mutational analysis confirms Stem 1 and Stem 2 formation in the pseudoknot region of the S. cerevisiae telomerase RNA. In vitro telomerase activities of the Stem 1–disrupting mutants 2a (723GGUUU728→CCAAA), 2b (729AUUCU733→UAAGA), 8a (771AGAAU775→UCUUA), 8b (776AAAUCC781→UUUAGG) and the Stem 1–restoring mutants 8b/2a (combination of mutants 8b and 2a) and 8a/2b (combine mutants 8a and 2b). In vitro telomerase activities of the Stem 2–disrupting mutants 5a (751AGUAGA756→UCAUCU) and 12a (807UCUAUU812→AGAUGA) and the Stem 2–restoring mutant 12a/5a (combination of mutants 12a and 5a). The activities of individual mutants were normalized to the wild-type activity. Nucleotides are labeled according to the numbering system in ref. 19.

To further test the proposed stems in the pseudoknot structure, we asked whether compensatory mutations, designed to restore the proposed base-paired elements with altered sequences, could rescue the decreased telomerase activities caused by helix-disrupting mutants. The helix-restoring double mutant 12a/5a produced higher activity than either single mutant 5a or 12a, consistent with the previously reported in vivo functional analysis19,21 (Fig. 1c). The lower activity of the double mutant 12a/5a compared to the wild-type enzyme might be explained by Stem 2 being involved in sequence-specific binding of Est2. At the other end of the pseudoknot, double mutant 8a/2b had much higher telomerase activity than either of the single mutants that disrupt the proposed base pairing, as did double mutant 8b/2a. These results confirm the existence of Stem 1, which was not experimentally confirmed in the previous studies19 owing to the weak effect of deleting Stem 1 on telomere length in vivo; of the four structure models (Supplementary Fig. 1), only the pseudoknot structure19 contains Stem 1 and is consistent with the lack of phenotype we observe for mutant 1.

Although the rescue of telomerase activity with compensatory mutations convincingly supported the formation of the pseudoknot structure, that model provided no explanation for mutant 4, which is mutated in a loop region but nevertheless has low activity (25-fold decrease). NMR spectroscopy studies on the human telomerase RNA pseudoknot22 and computational modeling combined with in vivo functional analysis on the Kluyveromyces lactis telomerase RNA pseudoknot23 both revealed a triple-helix structure formed by Hoogsteen hydrogen-bonding of the uridine-rich loop (the loop of Stem 1) to the major groove of the nearby U-A Watson-Crick base-paired Stem 2. Although such a triple helix had not been demonstrated in S. cerevisiae, the uridine-rich sequences mutated in mutant 4 are 100% conserved across all related Saccharomyces species15,20,21, suggesting possible structure conservation.

The predicted U-A•U base triples were tested by mutating them to C-G•C, which is the best structural mimic of U-A•U; protonation of the Hoogsteen-paired cytosine would provide an additional hydrogen bond (Fig. 2a,b). None of the mutants with mutations in one of the three individual strands (AAA mutated to GGG, and UUU mutated to CCC) had more than 10% of the wild-type telomerase activity (Fig. 2c). Previous efforts to restore the Stem 2 Watson-Crick base pairs by swapping the sequences of the two strands failed to rescue telomere shortening19, indicating that duplex formation is not sufficient for telomerase activity. Notably, when we combined all three sets of mutations, telomerase activity was rescued to the wild-type level (Fig. 2c, right). This result strongly indicates the existence of a triple helix in the S. cerevisiae telomerase RNA core region. As two of the three block mutants (3GCC-1 and 3GCC-2) showed recovery of activity, there seems to be some flexibility in which portion of the third strand forms the Hoogsteen base pairs. Furthermore, a mutant with C-G•U substituting for U-A•U, in which only one Hoogsteen hydrogen bond could be formed (Fig. 2b), also provided more than 60% of the wild-type telomerase activity (data not shown); thus, protonation of N3 of cytosine may be optional in the case of these C-G•C triples, because the entropic cost of forming the triple helix is ameliorated by the existence of the adjacent pseudoknot.

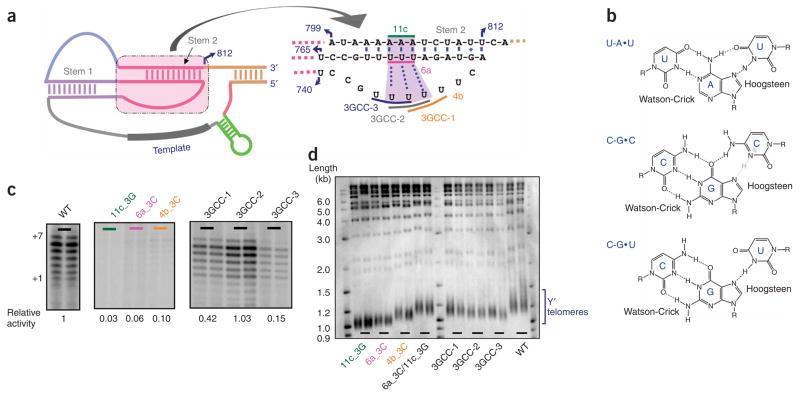

Figure 2.

The pseudoknot region of the S. cerevisiae telomerase RNA contains a triple-helix structure. (a) The sequences and the secondary structures of the triple-helix and adjacent regions in the context of the Micro-T 170 telomerase RNA (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for detail). The three dotted lines indicate the base triples best supported by this work; an additional flanking U-A•U triple may also form but was not tested here. (b) Base triples formed by U-A•U, C-G•C and C-G•U, respectively. All involve formation of Hoogsteen base pairs in the major groove of the Watson-Crick duplex. In the case of the C-G•C triple, protonation of N3 of cytosine at pH below its pKa (free nucleotide has pKa ~4.2) could provide an additional hydrogen bond (gray). (c) In vitro telomerase activities of the telomerase RNA triple helix–disrupting mutants 11c_3G (A804–A806→GGG), 6a_3C (U757–A759→CCC), 4b_3C (U746–U748→CCC) and the triple helix–restoring mutants 3GCC-1 (A804–A806→GGG/U757–A759→CCC/U746–U748→CCC), 3GCC-2 (A804–A806→GGG/U757–A759→CCC/U745–U747→CCC) and 3GCC-3 (A804–A806→GGG/U757–A759→CCC/U744–U746→CCC). The activities of individual mutants were normalized to the wild-type (WT) activity. (d) Telomere-length analysis of the telomerase RNA triple helix–disrupting mutants and triple helix–restoring mutants compared with the wild-type TLC1. Southern blot shows lengths of telomeric XhoI restriction fragments from cells harboring different TLC1 constructs and grown for 125 generations. Duplicate lanes represent two independent clones for each mutant. A probe that hybridizes to both strands of telomeric DNA was used. The markers shown were radiolabeled with 2-Log DNA Ladder (NEB). Y′ telomeres are preceded by a repeated DNA sequence that contains an XhoI restriction site.

Importance of the triple-helix RNA structure in vivo

To assess the functional importance of the identified triple-helix RNA structure in vivo, we introduced the above-mentioned triple-helix disruption mutants and helix-restoration mutants into the full-length S. cerevisiae telomerase RNA gene (TLC1) in yeast. After ~125 generations of growth, the telomeres of the triple-helix disruption mutants were substantially shortened (Fig. 2d), whereas the triple-helix restoration mutants had telomeres close to the wild-type length. None of the TLC1 mutations caused a senescence phenotype. Northern analysis indicated that the wild-type and mutant TLC1 strains had comparable TLC1 RNA levels (Supplementary Fig. 2 online). These results further support the model of the triple-helix structure in the core region of S. cerevisiae telomerase RNA and suggest that this structure is important for telomere maintenance in vivo, as found in the case of K. lactis23.

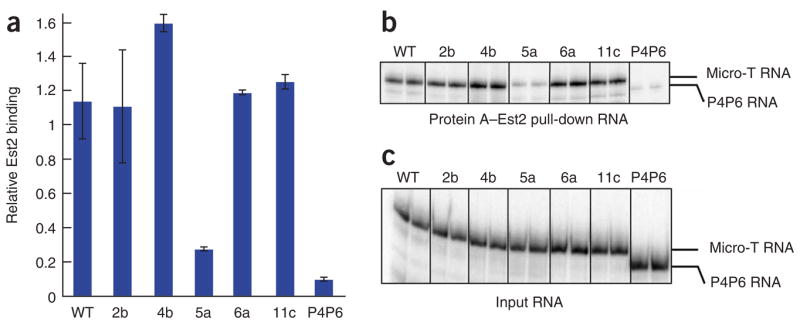

Triple-helix RNA structure is not required for Est2 binding

We next asked how the triple-helix structure contributes to telomerase action. Previous studies have suggested that the pseudoknot region of the telomerase RNA provides part of the binding region for Est2, the protein subunit of the telomerase core enzyme19,21. As the triple-helix is part of the pseudoknot region, we tested whether mutations in the triple helix affect Est2 binding. N-terminally Protein A–tagged Est2 protein was translated in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRL) and assembled with an approximately 10-fold molar excess of a new, 170-nt version of yeast telomerase RNA called Micro-T. We found that Micro-T is as active as the 500-nt Mini-T in the in vitro telomerase assay, and its smaller size makes it more suitable for biochemical characterization (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). Mutation 5a, which disrupted the end of Stem 2, largely decreased the association of telomerase RNA with Est2 protein (Fig. 3), in agreement with a previous report19,21. In contrast, all three mutations in the triple-helix region (4b, 6a and 11c, as defined in Fig. 2a) had no impact on RNP assembly. Furthermore, detailed measurements of the equilibrium dissociation constant of the purified Est2 RNA binding domain and various RNA mutants showed no destabilization of binding upon disruption of the triple helix (F.Q. and T.R.C., unpublished data) We conclude that the triple-helix structure in the yeast telomerase RNA is not responsible for the binding affinity of the reverse-transcriptase subunit.

Figure 3.

The triple-helix structure in TLC1 is not responsible for the binding affinity of the reverse-transcriptase subunit, Est2. ProA-Est2 translated in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) was assembled with wild-type (WT) Micro-T 170 telomerase RNA and various mutants shown in Figs. 1c and 2a. The assembled telomerase RNP was immunoprecipitated, and the associated telomerase RNA was separated by denaturing PAGE. The amounts of the Est2-bound RNA (b) and the input RNA (c) were quantified from the band intensity using a PhosphorImager and ImageQuant TL. The relative efficiency of Est2 binding is calculated from the ratio of the bound RNA to the input RNA compared to WT. P4P6 RNA (158 nt), an autonomously folded domain of group I intron ribozyme, was used as a negative control for Est2 binding. Error bars, s.d.

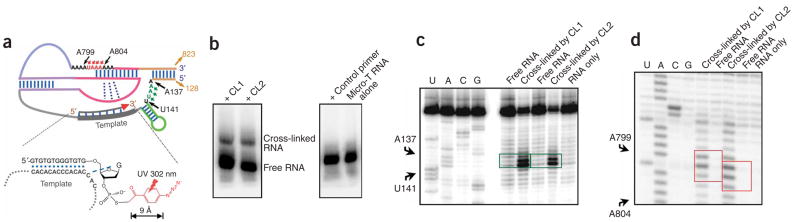

Triple-helix structure is close to the DNA substrate 3′ end

We therefore proposed that the triple-helix structure is involved in some step of the catalytic cycle, such as primer binding, primer orientation, product release or even active-site chemistry. For any of these to be possible, the triple-helix region would have to be in close proximity to the 3′ end of the DNA primer, where phosphodiester formation is catalyzed. We used a photoaffinity cross-linking method24 to search for regions of the RNA in the vicinity of the 3′ end of a template-bound DNA primer. Irradiation of Micro-T telomerase RNA prebound to a 3′-azidophenacyl DNA primer, which forms base pairs with the template region of Micro-T (Fig. 4a), gave cross-linked species, whereas the same experiment using a primer without the azidophenacyl label gave no cross-link (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4 online). Primer extension by reverse transcription identified three nucleotides in a loop at the 5′ end of the template boundary region as cross-linked sites (Fig. 4c) and, more notably, two to three adenines in the A-strand of the triple-helix were also found to be cross-linked to the 3′-azidophenacyl–labeled DNA primer (Fig. 4d). This result demonstrates that, even in the folded RNA in the absence of TERT, the triple-helix structure is in close proximity to the 3′ end of the primer substrate where nucleotide addition takes place. Proximity of the triple helix to the site of reaction is consistent with its possible involvement in catalysis. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) studies of human telomerase RNA suggest that its template region is also adjacent to the triple-helix region in the tertiary structure25.

Figure 4.

The triple-helix region is in close proximity to the 3′ end of the DNA substrate. (a) The secondary-structure model of the telomerase RNA Micro-T is shown with an annealed DNA primer—the substrate for telomerase—coupled through a thiophosphate to a photoactivatable cross-linking azidophenacyl group. Upon irradiation at 302 nm, the azido group is converted to a nitrene, which reacts to form a covalent bond between the DNA primer and nearby regions of the RNA. (b) Cross-linked and free Micro-T RNAs separated by denaturing PAGE. A primer without the azidophenacyl label gave no cross-link after UV irradiation, nor did Micro-T alone. (c,d) Primer extension analyses of DNA–Micro-T RNA conjugates with a 5′–32P-labeled oligonucleotide complementary to the 3′-terminal sequences of the Micro-T RNA. Lanes U, A, C and G correspond to sequencing reactions with non–cross-linked RNA template. The other lanes show primer extension reactions using various cross-linked or irradiated but non–cross-linked RNA species, as indicated. The major termination sites of primer extension, at which reverse transcriptase pauses or terminates because of the cross-linked nucleotides, are boxed in green in c and red in d, and the corresponding positions on the secondary-structure model are indicated by green or red arrowheads in a. Nucleotides are labeled according to the numbering system in ref. 19.

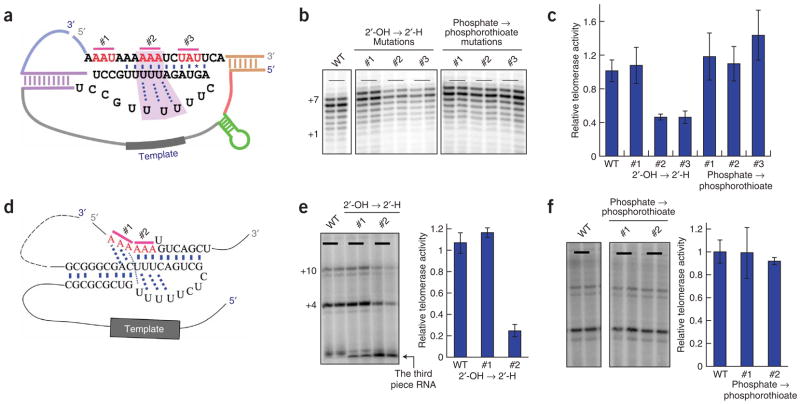

Role of 2′-OHs of the triple helix in catalysis

What chemical functional groups could a triple-helix provide to contribute to catalysis? Most chemical groups on the bases of the U-A•U base triple form hydrogen bonds with each other (Fig. 2b) and are therefore unlikely to have additional interactions to facilitate catalysis. Furthermore, C-G•C can replace U-A•U without a noticeable change of telomerase activity (Fig. 2c), and these two base triples have different chemical groups on their bases. This fact also suggests that chemical groups on the bases may not be involved in catalysis. We therefore proposed that either 2′-OHs or phosphates of the triple-helix structure could have the effect on telomerase catalysis.

To test this hypothesis, we made both 2′-OH to 2′-H and phosphate to phosphorothioate substitutions at several positions (Fig. 5a) in the pseudoknot region of a new two-piece version of the yeast telomerase RNA (Methods). After assembly with the RRL-translated Est2, the telomerase RNA containing each substitution was used in the activity assay. None of the phosphorothioate substitutions affected reconstituted telomerase activity (Fig. 5b,c). In contrast, the 2′-H substitutions in the triple-helix region (Fig. 5, #2) decreased the telomerase activity about two-fold, whereas substitutions in the loop region (Fig. 5, #1) upstream of the triple helix showed wild-type activity. Notably, a 2′-OH to 2′-H substitution (Fig. 5, #3) in the stem adjacent to the triple helix also reduced telomerase activity about two-fold (Fig. 5b,c).

Figure 5.

The 2′-OH groups in the triple-helix regions of both yeast and human telomerase RNAs are important for catalysis. (a–c) Both 2′-OH to 2′-H and phosphate to phosphorothioate substitutions were made at three different sets of three nucleotides (#1, #2 and #3 in a) of the pseudoknot region in the yeast telomerase RNA. After assembly with the RRL-translated Est2, the telomerase RNA containing each substitution was used in the direct telomerase activity assay in b. Relative activity of each mutant was calculated based on two independent reactions with the wild-type (WT) activity set as 1; the results are shown in c. (d) The human three-piece telomerase RNA system26, with all the substitutions being made on the third chemically synthesized piece of RNA, was used to test the importance of 2′-OH groups and phosphates in the triple-helix region of the human telomerase RNA. The positions of substitutions introduced in the triple-helix region are indicated as #1 and #2. (e,f) After assembly with the RRL-translated human TERT, the telomerase RNA containing each substitution (2′-OH to 2′-H in e and phosphate to phosphorothioate in f) was used in the direct telomerase activity assay. Relative activity of each mutant was calculated based on two independent reactions with the wild-type activity set as 1; results are shown in the bar graphs (right). In e, radiolabeling of the third piece of RNA allowed activity to be normalized to the amount of telomerase RNA present in each reaction. Error bars, s.d.

Because human telomerase RNA contains a homologous triple-helix structure as revealed by NMR studies22, we suspected that the function of the 2′-OH groups might be conserved in the human triple helix. To test this, we introduced either 2′-OH to 2′-H or phosphate to phosphorothioate substitutions in two regions of the human telomerase RNA, one in the triple-helix structure and the other in the loop region near the triple-helix structure. We used a three-piece telomerase RNA system26, with all the substitutions being made on the third chemically synthesized piece of RNA. Consistent with our results from the yeast system, we observed wild-type in vitro activity of telomerase RNA with phosphorothioate substitutions (Fig. 5d–f). For the mutants with 2′-H substitutions, telomerase activity was reduced by approximately five-fold for the substitution in the triple-helix structure, whereas a substitution in the nearby loop region gave wild-type telomerase activity (Fig. 5e).

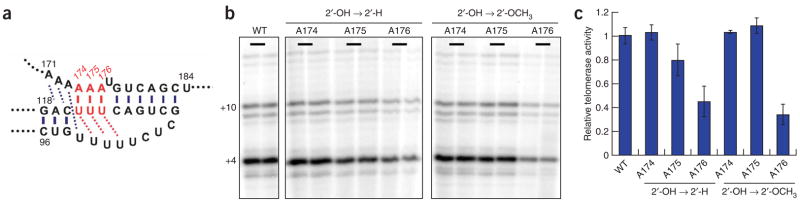

Because the 2′-H substitutions in the human telomerase RNA triple-helix region had a more appreciable effect on activity than those in the yeast system, we further explored the contribution of individual 2′-OH groups in the human system. Positions A174, A175 and A176 were substituted with 2′-H and with 2′-OCH3, both of which should prevent hydrogen bond donation. Because 2′-OCH3 ribose has the same sugar pucker as ribose, a 2′-OH to 2′-OCH3 substitution should have no conformational effect on the triple-helix RNA structure, as might perhaps occur with a 2′-H substitution. Whereas either 2′-H or 2′-OCH3 substitution at positions A174 and A175 had little effect on the telomerase activity, 2′-H substitution at A176 decreased the telomerase activity approximately two-fold, and 2′-OCH3 substitution at A176 decreased the telomerase activity approximately three-fold (Fig. 6). These data strongly suggest that the 2′-OH of A176 in the human telomerase RNA triple-helix contributes to telomerase catalysis.

Figure 6.

The 2′-OH group of A176 in the triple-helix structure of human telomerase RNA is important for catalysis. (a) Both 2′-OH to 2′-H and 2′-OH to 2′-OCH3 substitutions were made at three different positions (A174, A175 and A176) in the triple-helix region of the human telomerase RNA. (b) After assembly with the RRL-translated TERT, the telomerase RNA containing each substitution was used in the direct telomerase activity assay. (c) Relative activity of each mutant was calculated based on two independent reactions with the wild-type (WT) activity set as 1. Error bars, s.d.

DISCUSSION

Telomerase is often called a ‘specialized reverse transcriptase’, signifying a protein enzyme that binds and repetitively copies its own RNA template. Here we describe an RNA triple helix within the pseudoknot structure of the yeast and human telomerases that contributes additional catalytic efficiency beyond that provided by the TERT protein alone. Quantitatively, the protein active site still contributes the vast majority of the catalysis5, with the RNA triple helix adding the final approximately 25-fold. Some of the RNA’s contribution is due to a specific 2′-OH group or groups that are in proximity to the catalytic active site and provide two-fold to five-fold of the 25-fold total increase in catalytic efficiency. The remainder of the triple helix’s contribution, which cannot be ascribed to 2′-OH groups, may simply be the triple helix constraining the RNA structure in a way that brings the template-primer pair into proximity to the reverse transcriptase active site of TERT. Such increases in ‘effective concentration’ of reactants are fundamental to enzyme catalysis27.

In a general sense, the active site of telomerase may then bear some similarity to the active site of group I intron ribozymes. For a group I ribozyme to efficiently cleave a substrate RNA, the substrate needs, first, to base pair with a complementary internal guide sequence (IGS) to form a helix, called P1; second, this P1 helix is oriented relative to the ribozyme active site through a 2′-OH–mediated hydrogen-bonding network17,28. In the case of telomerase, the DNA primer first base-pairs with the alignment region of the RNA template. Here we present evidence that this short primer-template helix is then oriented relative to the active site in TERT through 2′-OH–mediated interactions. One potential advantage of such backbone interactions is that they could be sequence nonspecific, so they could be reformed at new positions along the primer-template helix as it moved through the active site.

In the case of the Tetrahymena group I intron ribozyme, individual 2′-H substitutions on the IGS at nucleotides 22 and 25, which make tertiary interactions with the ribozyme core, reduced the reaction rate by ten-fold or less than two-fold (33%), respectively17. These effects are quantitatively of the same order of magnitude as the two-fold to three-fold effects reported here for 2′-H or 2′-OCH3 substitution at A176 in human telomerase. In the case of the ribozyme, these same 2′-H substitutions led to infidelity of cleavage by promoting alternative binding registers of the RNA-IGS helix29. The RNA-IGS helix may be considered to be analogous to the telomeric DNA primer-RNA template helix in telomerase. However, in a telomerase polymerization reaction, unlike a cleavage reaction, alternative binding registers of the primer-template helix would not give rise to any altered reaction product that would allow them to be easily observed.

In conclusion, we have described the unexpected finding that a nontemplate part of the telomerase RNA works together with the protein reverse-transcriptase motifs to facilitate catalysis, using a mechanism resembling that of pure RNA enzymes. Therefore, telomerase has acquired properties of both protein and RNA-based enzymes. This might have occurred by one of two alternative pathways. In the ‘RNA first’ model, an ancient ribozyme later acquired a reverse-transcriptase subunit; the triple helix would then be a molecular fossil. According to this model, telomerase is a missing link in evolution from RNA enzymes to protein enzymes. The alternative is the ‘protein first’ model, in which an ancient reverse transcriptase acquired an intrinsic RNA template. Later, mutations in the RNA led to the formation of the triple helix, which, because it enhanced catalysis, provided a selective advantage. It will be interesting to see whether other RNPzymes, such as the small nucleolar RNPs (snoRNPs), which catalyze site-specific modification of ribosomal RNA, have also evolved such an intimate collaboration between a protein enzyme and its RNA partner.

METHODS

In vitro telomerase activity assays

For reconstitution of yeast telomerase activity from Mini-T RNA10 and Est2 protein, we introduced linearized plasmid T7–Mini-T (500) or Mini-T mutant together with plasmid T7-ProA-Est2 into an RRL transcription and translation system (TNT Quick Coupled, Promega), and the reaction was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions for linearized DNA. ProA-Est2–Mini-T complex was then immunopurified from the RRL using IgG–Sephadex 6 beads (Amersham) overnight at 4 °C. Beads were then washed four times with 1 ml of TMG buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mM MgCl2, 5% (v/v) glycerol). Yeast and human direct telomerase activity assays were carried out as described in ref. 10 and ref. 26, respectively. Radiolabeled +1 marker of the DNA primer generated using terminal transferase (NEB) and [33P]ddTTP.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain and telomere-length analysis

A haploid S. cerevisiae strain, YVL1009 (MATα tlc1-Δ::LEU2 rad52-Δ::LYS ura3-52 lys2-801 ade2-101 trp1-Δ1 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ/pSD120), provided by V. Lundblad (The Salk Institute for Biological Studies), was used for the telomere-length analysis. Briefly, strain YVL1009 was transformed with pRS424-TLC1 (ref. 30) or Tlc1 variants with mutations introduced into the telomerase RNA triple-helix region. After growth on selective media, single colonies were picked and transferred to medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) to shuffle out the complementing pSD120. Single colonies were then restreaked onto medium lacking tryptophan (−TRP medium) for further analysis. Single colonies from the fifth restreak on −TRP medium after growth on 5-FOA were picked into 20 ml of selective liquid culture. Saturated cultures were harvested, and genomic DNA was prepared using the DNA-Pure Yeast Genomic Kit (CPG Inc.). Half of the isolated DNA was digested with XhoI, resolved on a 1.1% agarose gel and then transferred to Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia) by osmoblotting. DNA was visualized with randomly primed radiolabeled probes to telomeric repeat sequences.

Immunopurification of telomerase TERT–RNA complex

ProA-Est2 was first expressed in RRL at 30 °C for 60 min. We then mixed 25 μl of the RRL with 0.15 pmol pre-refolded Micro-T (170) RNA and incubated the mixture at 30 °C for a further 30 min. Unlabeled wild-type Micro-T and its mutants were spiked with less than 1% of 32P-labeled corresponding RNA. Samples were incubated with 10 μl IgG–Sephadex 6 beads in 500 μl final volume of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.10 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mg ml−1 BSA and 0.5 mg ml−1 yeast tRNA for 4 h at 4 °C. The assembled bound telomerase RNP complexes were washed three times with TMG buffer; the associated telomerase RNA was then eluted from the beads by urea denaturing buffer and separated in a 7% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The amount of Est2 protein-bound RNA was quantified from the band intensity by ImageQuant TL ( GE Healthcare).

Photo–cross-linking analysis

Gel-purified 3′ thiophosphorylated primers CL1 (GTGTGTGGGTGTGG) and CL2 (GTGTGTGGGTGTGGTG) were provided by TriLink BioTechnologies. Primers were resuspended in 40% (v/v) methanol, 33 mM sodium bicarbonate (pH 9.0), 0.1% (w/v) SDS and 5 mM azidophenacyl bromide (Sigma) and incubated at 25 °C in the dark for 1 h. The reaction mixture was extracted with two volumes of phenol-chloroform to remove excess azidophenacyl bromide, and the 3′-azido CL1 and CL2 primers were recovered by ethanol precipitation. The photoagent-containing primer was incubated with an equal amount of Micro-T (170) RNA in 50 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2 at 42 °C for 2 min, then placed on ice for 20 min. Half of the assembled 3′-azido primer–Micro-T RNA complex was exposed to UV light as described previously24; the other half was kept without any UV irradiation as a control. Primer–Micro-T RNA conjugates were resolved by 6% denaturing PAGE, and the free RNA and the primer-conjugated RNA were water-eluted separately from the gel. We subsequently carried out primer extension by reverse transcription using an end-labeled primer complementary to the 3′-end sequence of the Micro-T RNA to identify cross-linked nucleotides.

Synthesis of telomerase RNAs with phosphate or ribose modifications

Human telomerase complexes with phosphate or ribose modifications in the telomerase RNA were reconstituted in vitro by using the three-piece telomerase RNA system described previously26. Modifications were incorporated into the third-piece RNA (hTR 171–184) chemically synthesized by Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). For yeast telomerase complexes with phosphate or ribose modifications in the telomerase RNA, Micro-T 170 RNA was divided into two pieces of 137 nt and 33 nt, respectively. Modifications were incorporated into the 33-nt RNA synthesized by Dharmacon. In both human and yeast systems, the telomerase RNA pieces were mixed and refolded before being assembled with TERT or Est2.

Supplementary Material

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology website.

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Lundblad (The Salk Institute for Biological Studies) for providing yeast strains, D. Zappulla for help with yeast telomerase assays and in vivo analysis, A. Zaug and A. Mozdy (University of Colorado, Boulder) for plasmids, Y. Tzfati for sharing results before publication and A. Berman for helpful comments on the manuscript. F.Q. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation. This work was supported in part by the US National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM28039.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F.Q. and T.R.C. conceived and designed the study; F.Q. performed the experiments; and F.Q. and T.R.C. analyzed the results and wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Collins K. The biogenesis and regulation of telomerase holoenzymes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:484–494. doi: 10.1038/nrm1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Autexier C, Lue NF. The structure and function of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:493–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cech TR. Beginning to understand the end of the chromosome. Cell. 2004;116:273–279. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singer MS, Gottschling DE. TLC1: template RNA component of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase. Science. 1994;266:404–409. doi: 10.1126/science.7545955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lingner J, et al. Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science. 1997;276:561–567. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greider CW, Blackburn EH. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature. 1989;337:331–337. doi: 10.1038/337331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen JL, Blasco MA, Greider CW. Secondary structure of vertebrate telomerase RNA. Cell. 2000;100:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80687-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lingner J, Hendrick LL, Cech TR. Telomerase RNAs of different ciliates have a common secondary structure and a permuted template. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1984–1998. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theimer CA, Feigon J. Structure and function of telomerase RNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:307–318. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zappulla DC, Goodrich K, Cech TR. A miniature yeast telomerase RNA functions in vivo and reconstitutes activity in vitro. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:1072–1077. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai CK, Miller MC, Collins K. Roles for RNA in telomerase nucleotide and repeat addition processivity. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1673–1683. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00232-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JL, Greider CW. Determinants in mammalian telomerase RNA that mediate enzyme processivity and cross-species incompatibility. EMBO J. 2003;22:304–314. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzfati Y, Fulton TB, Roy J, Blackburn EH. Template boundary in a yeast telomerase specified by RNA structure. Science. 2000;288:863–867. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mason DX, Goneska E, Greider CW. Stem-loop IV of Tetrahymena telomerase RNA stimulates processivity in trans. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5606–5613. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5606-5613.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zappulla DC, Cech TR. Yeast telomerase RNA: a flexible scaffold for protein subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10024–10029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403641101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller MC, Collins K. Telomerase recognizes its template by using an adjacent RNA motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6585–6590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102024699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strobel SA, Cech TR. Tertiary interactions with the internal guide sequence mediate docking of the P1 helix into the catalytic core of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13593–13604. doi: 10.1021/bi00212a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pyle AM, Murphy FL, Cech TR. RNA substrate binding site in the catalytic core of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Nature. 1992;358:123–128. doi: 10.1038/358123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin J, et al. A universal telomerase RNA core structure includes structured motifs required for binding the telomerase reverse transcriptase protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14713–14718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405879101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dandjinou AT, et al. A phylogenetically based secondary structure for the yeast telomerase RNA. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1148–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chappell AS, Lundblad V. Structural elements required for association of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase RNA with the Est2 reverse transcriptase. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7720–7736. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7720-7736.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theimer CA, Blois CA, Feigon J. Structure of the human telomerase RNA pseudoknot reveals conserved tertiary interactions essential for function. Mol Cell. 2005;17:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shefer K, et al. A triple helix within a pseudoknot is a conserved and essential element of telomerase RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2130–2143. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01826-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgin AB, Pace NR. Mapping the active site of ribonuclease P RNA using a substrate containing a photoaffinity agent. EMBO J. 1990;9:4111–4118. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gavory G, Symmons MF, Krishnan Ghosh Y, Klenerman D, Balasubramanian S. Structural analysis of the catalytic core of human telomerase RNA by FRET and molecular modeling. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13304–13311. doi: 10.1021/bi061150a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JL, Greider CW. Functional analysis of the pseudoknot structure in human telomerase RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8080–8085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502259102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jencks WP. Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stahley MR, Strobel SA. Structural evidence for a two-metal-ion mechanism of group I intron splicing. Science. 2005;309:1587–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.1114994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strobel SA, Cech TR. Translocation of an RNA duplex on a ribozyme. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1:13–17. doi: 10.1038/nsb0194-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mozdy AD, Cech TR. Low abundance of telomerase in yeast: implications for telomerase haploinsufficiency. RNA. 2006;12:1721–1737. doi: 10.1261/rna.134706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology website.