Abstract

The one-electron oxidations of a series of diiron(I) dithiolato carbonyls were examined to evaluate the factors that affect the oxidation state assignments, structures, and reactivity of these low-molecular weight models for the Hox state of the [FeFe]-hydrogenases. The propanedithiolates Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(L)(dppv) (L = CO, PMe3, Pi-Pr3) oxidize at potentials ~180 mV milder than the related ethanedithiolates (Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 6152). The steric clash between the central methylene of the propanedithiolate and the phosphine favors the rotated structure, which forms upon oxidation. EPR spectra for the mixed-valence cations indicate that the unpaired electron is localized on the Fe(CO)(dppv) center in both [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)4(dppv)]BF4 and [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]BF4, as seen previously for the ethanedithiolate [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]BF4. For [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]BF4, however, the spin is localized on the Fe(CO)2(Pi-Pr3) center, although the Fe(CO)(dppv) site is rotated in the crystalline state. IR and EPR spectra, as well as redox potentials and DFT-calculations, suggest, however, that the Fe(CO)2(Pi-Pr3) site is rotated in solution, driven by steric factors. Analysis of the DFT-computed partial atomic charges for the mixed-valence species shows that the Fe atom featuring a vacant apical coordination position is an electrophilic Fe(I) center. One-electron oxidation of [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)(CO)3(dppv)]− resulted in 2e oxidation of 0.5 equiv to give the μ-cyano derivative [FeI2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)](μ-CN)[FeII2(S2C2H4)(μ-CO)(CO)2(CN)(dppv)], which was characterized spectroscopically.

Introduction

Modeling of the diiron active site of the [FeFe]-hydrogenases has provided a rich and tractable set of challenges to organometallic chemistry.1 Motivated by discoveries in biophysical chemistry,2,3 the chemistry of the Fe2(SR)2(CO)6−xLx system, previously well examined, has been rejuvenated. Ongoing work in this and other laboratories has shown that these complexes are versatile with respect to redox, substitution, and functionalizability in ways that are pertinent to the enzyme’s active site. A significant breakthrough in the modeling efforts entailed the preparation of the mixed-valence derivatives of the formula the [FeIFeII(SR)2(CO)4−x(PMe3)Lx]+ (L = carbene or diphosphine).4,5 These species exhibit the “rotated” stereochemistry for one of the two Fe centers (Scheme 1). This stereochemistry exposes a vacant coordination site on one Fe center, as had been anticipated by numerous biophysical studies.2 This geometry was rare in the otherwise extensive chemistry of diiron dithiolato carbonyls.6 Now that the rotated geometry has been demonstrated to exist in the absence of the protein, efforts can be expected to focus on the factors that govern this geometry and its reactivity.7,8 In this work, we probe the effects of both the dithiolate and especially the terminal ligands on the electronic and molecular structure of the mixed valence state.

Scheme 1.

Structure of the diiron active site of the Hox state of the [FeFe]-hydrogenases (X is CH2, NH, or O).

Modeling of the [FeFe]-hydrogenases started with the preparation of [Fe2(SR)2(CN)2(CO)4]2−,9 this anion being notable because it featured five of six known ligands in the active site. The redox and protonation of this dicyanide has been developed only to a limited extent.10 Such studies are complicated by the reactivity inherent in the cyanide ligand, which is known to bridge to other metals and to protonate readily.11 The modeling efforts have advanced significantly by using tertiary phosphine ligands in the place of the cyanides. In this paper, we return briefly to the redox chemistry of the diiron centers supported by a cyanide ligand.

Results

[Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)4(dppv)]+

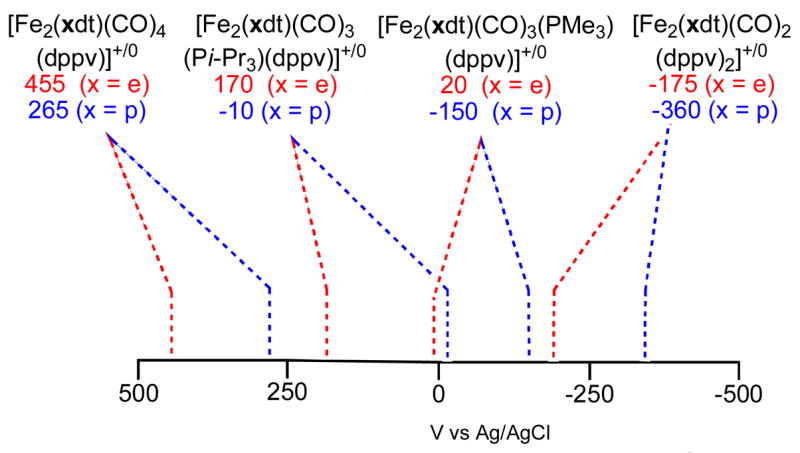

The cyclic voltammetry of the recently reported complexes12 Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)4(dppv) established that the propanedithiolate (2pdt) undergoes oxidation at ca. 190 mV more cathodic than the ethanedithiolato analogue (2edt) (Figure 1). The redox potentials for these couples were unchanged when the oxidations were conducted under argon, dihydrogen, and dinitrogen; traces of water also had no effect.

Figure 1.

Redox properties of diiron(I) dithiolates (CH2Cl2 soln).a

aUnless indicated otherwise, couples are reversible as judged from the finding that ipc/ipa ~1.

From the CV results, the complex Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)4(dppv), 2pdt, was shown to undergo a one-electron oxidation at a potential less than the Fc0/+ couple (0.5 V in CH2Cl2 vs Ag/AgCl).13 This conversion was confirmed on a preparative scale by treating a CH2Cl2 solution of 2pdt with FcBF4 at −45 °C. The IR spectrum of the product (νCO = 2076, 2019, 1943 cm−1) proved to be similar to that for the recently reported5 [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]BF4 but shifted to higher energy by ~50 cm−1, reflecting the effect of replacing PMe3 by CO (Figure 2). Solutions of [2pdt]+ were found to react with NO to yield [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(dppv)(NO)]+, with the NO bound on the Fe(dppv) side of the molecule, consistent with an open coordination site residing on the Fe(dppv) (eq 1).14

Figure 2.

IR spectra (CH2Cl2 solns) of [Fe2(S2C3H4)(CO)4(dppv)]BF4 ([2pdt]BF4, A) and [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]BF4 ([3pdt]BF4, B).

Oxidation of Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)

In a preliminary report, we had described the one-electron oxidation of the ethanedithiolate Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv) (3edt).5 Oxidation of the related propanedithiolate (3pdt) using FcBF4 yielded the corresponding derivative [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]BF4 ([3pdt]BF4) but at a potential that is milder by ~180 mV. We verified the electrochemical results with a preparative scale reaction. When a 1:1 mixture of 3pdt and 3edt was treated with one equiv of FcBF4 (0.5 equiv per diiron), we observed complete consumption of 3pdt as indicated by the loss of the high energy νCO band, uniquely assigned to the S2C3H6 derivative. Only upon the addition of a second equiv of FcBF4 did 3edt undergo oxidation. The structure of [3pdt]BF4 was confirmed crystallographically (see below). The IR spectrum (Figure 2) of [3pdt]BF4 salt was very similar to that for [2edt]BF4, the greatest difference being for the νμ-CO band which occurred at 7 cm−1 higher energy for the S2C3H6 derivative.

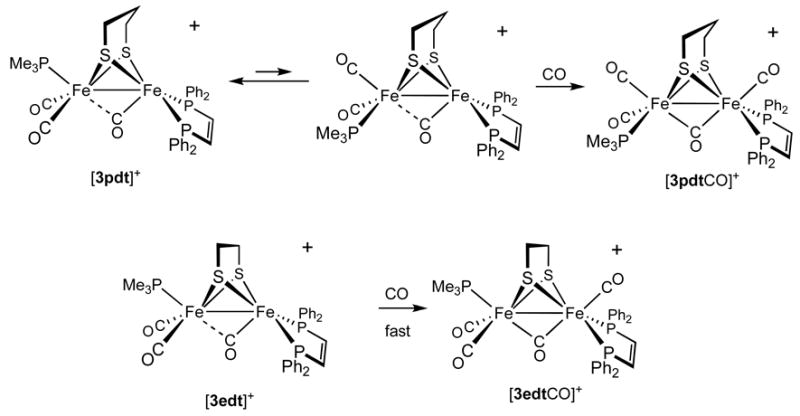

A solution of [3pdt]+ was found to react with CO to yield the adduct [3pdtCO]BF4. Intermediates were not observed. The rate of carbonylation was slower (t1/2 ~ 600 s at 1 atm., −45 °C) than the carbonylation of [2edt]+ (t1/2 ~ 30 s at 1 atm., −45 °C). The slowness of the carbonylation is attributed to the required, sluggish relocation of the PMe3 ligand to a basal position, apparently driven by avoidance of a steric clash with the propanedithiolate strap. For diiron dithiolates bearing seven terminal ligands, it is known that the propanedithiolates (vs ethanedithiolate) tend to be less stable, which is attributable to steric congestion.8,15 In contrast, mixed-valence complexes with a propanedithiolate are more stable than the ethanedithiolate analogues.

The stereochemistry of [3pdtCO]BF4 can be assigned on the basis of its solution EPR spectrum, wherein we observed 1:4:4:1 quartet resulting from three smaller 31P hyperfine couplings associated with three basal phosphine ligands. This pattern is consistent with the previously published analysis of HoxCO models (see below).8 In addition to its slow formation, [3pdtCO]+ differs from [3edtCO]+ with respect to νμ̃CO, which is 1791 cm−1 in the propanedithiolate and 1783 cm−1 in the ethanedithiolate. The terminal νCO bands are also shifted for [3pdtCO]+ but in the opposite fashion, reflecting a compensating relationship between νμ̃CO and ν□-CO. The binding of CO is a reversible process: an N2 purge slowly regenerated [3pdt]+. The EPR spectrum for [3edtCO]+ (see below) differed from that for [3pdtCO]+, being consistent with apical PMe3 and dibasal dppv (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Pathways for the carbonylations of [3edt]+ and [3pdt]+.

[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(PCy3)(dppv)]0/+

Unlike the analogous PMe3 derivative, the tricyclohexylphosphine complex Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(PCy3)(dppv) (4edt) could not be prepared by thermally induced substitution of 2edt. Photochemical substitution proved efficient however. The spectroscopy for 4edt was unremarkable, and the position of the νCO bands (νCO(avg) ~ 1927 cm−1) indicated that the complex resembles 3edt. Unexpectedly, the CV data (+140 mV vs Ag/AgCl) showed that 4edt was more difficult to oxidize than the analogous PMe3 derivative, which provided the first clue that the bulk of the trialkylphosphine ligands might strongly affect the electronic structure of these diiron compounds.

Oxidation of 4edt was effected in the usual way using FcBF4 at −45 °C in CH2Cl2. IR measurements showed that the oxidation shifts νCO by an average of ~50 cm−1, as seen for the corresponding oxidations of 2pdt, 3edt, and 3pdt. The average of the terminal νCO bands was, however, lower than that observed for [3edt]+, and the pattern was distinctly different, indicating that the structures of [3edt]+ and [4edt]+ differ. These cations also differ in terms of their stabilities: solutions of [3edt]+ are stable for a few seconds at room temperature, whereas the decomposition of [4edt]+ is already apparent near −20 °C. For reasons of preparative convenience, further studies on bulky phosphines were conducted with Pi-Pr3 instead of PCy3 (next section).

[Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]0/+

Using to the methods to obtain [4edt]+, the complexes Fe2(xdt)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv) were prepared for both xdt = edt and pdt. The IR spectra for the trisubstituted diiron(I) complexes (4edt, 3pdt, 5edt, and 5pdt) were very similar. The 31P DNMR properties for this series differed, however. The DNMR properties of 3edt and 3pdt have been previously discussed.12 At 20 °C, the 31P NMR spectrum of 5edt featured both a broad and a sharp singlet, assigned respectively to the dppv ligand and Pi-Pr3. At −40 °C, the dppv signal decoalesced into a pair of doublets, whereas the singlet assigned to Pi-Pr3 remained sharp. The low barrier for dynamics at the Fe(CO)(dppv) site is consistent, indirectly, with the location of the Pi-Pr3 in a basal site, which would destabilize the apical-basal spanning dppv due to a steric interaction across the two basal sites. For 5pdt, the 20 °C 31P NMR spectrum consisted of two singlets in a 2:1 ratio, again assigned to the dppv and Pi-Pr3 ligands, respectively. The structures of 5edt and 5pdt, which wasverified crystallographically, see Supporting Information) are as follows:

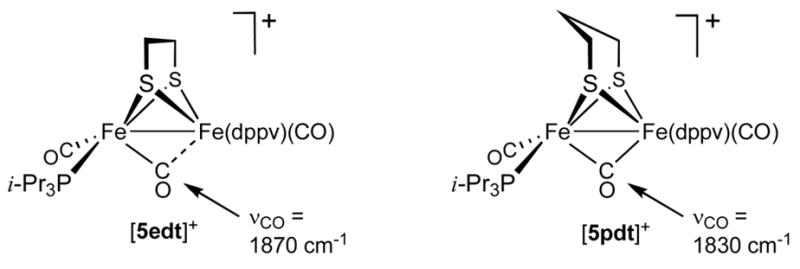

The cyclic voltammetry of CH2Cl2 solutions of 5edt and 5pdt showed that both undergo one-electron oxidations. The separation, Δ;Epdt−Eedt (160 mV), is comparable to the difference observed for 3edt vs 3pdt, but the absolute values of the redox couples are strikingly different. Complex 5edt was found to oxidize at +170 mV and 5pdt at +10 mV (vs Ag/AgCl). These potentials are ca. 150 mV more anodic than seen for related 3edt and 3pdt (Figure 1). One-electron oxidation of 5edt with FcBF4 gave the mixed-valence salt [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]BF4, [5edt]BF4. IR spectra in the νCO region are virtually identical for [5edt]+ and the PCy3-containing cation [4edt]+. One-electron oxidation of 5pdt at −45 °C using FcBF4 afforded [5pdt]BF4. Values for νt-CO for [5pdt]+ and [5edt]+ match closely (Figure 3). A significant difference is, however, observed for νμ–CO, which is 1830 cm−1 for [5pdt]+ vs 1870 cm−1 for [5edt]+, consistent with a steric interaction between the propanedithiolate and the bulky Pi-Pr3 ligand, which displaces the bridging CO toward a more symmetrically bridging position, as anticipated by the DFT calculations (see below, Scheme 3, see below for explanation).

Figure 3.

IR spectra (absorbance mode, CH2Cl2 at −45 °C) showing the effects of edt vs pdt for the oxidation of complexes containing bulky phosphine ligands: [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]BF4 ([5edt]BF4, top) and [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]BF4 ([5pdt]BF4, bottom).

Scheme 3.

Proposed solution structures of [5edt]+ and [5pdt]+.

Complex [5edt]+ was found to form an adduct with CO, but the carbonylation (~30 min at −45 °C) is significantly slower than for [3edt]+ (~30 s at −45 °C). The IR and EPR spectra of [3edtCO]+ and [5edtCO]+ are very similar, indicating similar structures, despite structural differences of the precursors. The average of the two νtCO bands is 20 cm−1 lower for [5edt]+ vs [3edt]+. This difference is consistent with the presence of a FeII(CO)2(PMe3) vs a FeI(CO)2(Pi-Pr3) site, i.e., the larger phosphine redirects the site of oxidation. A similar pattern applies also to the [3pdt]+/[5pdt]+ pair. Solutions of [5pdt]+ were found to be stable at 0 °C for several minutes, whereas [5edt]+ was found to rapidly decompose above −20 °C. Solid [5pdt]BF4 was rapidly precipitated by transferring a CH2Cl2 solution at −45 °C into a large excess of hexane cooled to −78 °C. Although we were unable to isolate an analytically pure sample, the IR spectrum of finely powdered [5pdt]BF4 (KBr pellet) matched the solution data (Δ;νμ–CO ~3 cm−1).

Solution EPR Studies of Mixed-Valence Models

The X-band EPR spectra of frozen solutions were similar, showing axial patterns with well defined hyperfine coupling to phosphorus (Table 1). Thus, a frozen solution of [2pdt]BF4 showed a triplets with A(31P) ~ 75 MHz, Figure 5. For the mononuclear Fe(I) complex trans-[Fe(CO)3(PPh3)2]+, the hyperfine values are ca. 55 MHz.16 The magnitude and multiplicity of the hyperfine couplings indicate that the spin resides on the Fe(CO)(dppv) center wherein the two phosphine sites are equivalent. The EPR spectrum of the analogous salt [3edt]BF4 also showed triplets with comparable g-values and hyperfine constants (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Selected EPR Parameters for [Fe2(S2CXH2x)(CO)2L(dppv)]BF4 (Spectra Recorded at 110 K (−163 °C), in 1:1 CH2Cl2:toluene).

| Complex (donor ligands) | gz | Azz | gy | Ayy | gx | Axx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [2pdt]+ (dppv) | 2.1490 | 78, 78 | 2.0199 | 71, 71 | 2.0086 | 72, 72 |

| [3edt]+ (dppv, PMe3) | 2.1384 | 80, 80 | 2.0280 | 74, 74 | 2.0102 | 72, 72 |

| [3pdt]+a (dppv, PMe3) | 2.1310

2.1410 |

82, 82

81, 81 |

2.0223

2.0268 |

76, 76

73, 73 |

2.0085

2.0064 |

74, 74

75, 75 |

| [4edt]+ (dppv, PCy3) | 2.0958 | 69 | 2.0423 | 67 | 2.0098 | 73 |

| [5edt]+ (dppv, Pi-Pr3) | 2.0968 | 70 | 2.0437 | 71 | 2.0105 | 75 |

| [5pdt]+ (dppv, Pi-Pr3) | 2.1046 | 80 | 2.0268 | 73 | 2.0149 | 80 |

For [3pdt]+ the two species are present in at 2:1 ratio.

Figure 5.

X-Band EPR spectra (110K, 1:1 CH2Cl2:toluene frozen solution): [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)4(dppv)]+ ([2pdt]+, a), [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]+ ([3pdt]+, b), [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]+ ([5pdt]+, c).

Figure 4.

X-Band EPR spectra (110K, 1:1 CH2Cl2: toluene frozen solution) of [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]BF4 ([3edt]BF4). Top is the simulation and bottom is experimental data.

An interesting feature of the EPR spectrum of [3pdt]+ is the presence of pairs of separate features in a ~2:1 ratio, especially discernable in the lower field signal. Each set of axial signals has a pattern (both g and A values) similar to that for [3edt]+. The two isomers are proposed to differ with respect to the fold of the propanedithiolate. The sensitivity of the EPR spectrum to the orientation of the dithiolate backbone shows that the SOMO of [3pdt]+ is affected by the central atom of the dithiolate (eq 2). Upon warming the solution to −50 °C, only a single isotropic triplet signal is observed.

A similar equilibrium was not observed for other propanedithiolate derivatives, which we attribute to either (i) greater “steric asymmetry,” which favors the tilting of the central methylene toward the open site on the rotated iron center ([5pdt]+) or (ii) insensitivity of the SOMO to the asymmetry due to the presence of CO ligands in both apical positions ([3pdtCO]+, see below).

The stereochemistry of the CO adduct, [3pdtCO]BF4 was indicated by EPR spectroscopy. For such HoxCO models, we recently showed that phosphine ligands in the apical positions give rise to large A-values (>200 MHz), whereas A-values are much smaller (<50 MHz) for phosphine ligands attached to the basal sites.8 For example, the EPR spectrum of [3edtCO]+ is characterized by one large A-value (>250 MHz) and two smaller ones (42, 28 MHz). A very different spectrum was obtained for [3pdtCO]+: the three A(31P) values were quite small (27, 39, 28, MHz; see Table 3), indicative that all three phosphine ligands occupy basal positions. Upon binding of CO, the PMe3 undergoes a change in geometry, from apical in [3pdt]+ to basal in [3pdtCO]+ (Scheme 2). In general, reflecting steric crowding, the CO adducts of ethanedithiolate derivatives are significantly more stable than the propanedithiolate analogues.

Table 3.

Selected Structural Parameters for [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3L(dppv)]BF4 (L = PMe3, Pi-Pr3).

| Distances (Å) | L = Pi-Pr3 | L = PMe3 | Angles (deg.) | L = Pi-Pr3 | L = PMe3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe(1)–Fe(2) | 2.5824 (10) | 2.5768 (8) | Fe(1)–S(1)–Fe(2) | 69.53 (3) | 69.53(3) |

| Fe(1)–S(1) | 2.2745 (10) | 2.2730 (8) | Fe(1)–Fe(2)–S(1) | 55.60 (3) | 55.73 (2) |

| Fe(2)–S(1) | 2.2544 (11) | 2.2460 (8) | Fe(2)–Fe(1)–S(1) | 54.87 (3) | 54.74 (2) |

| Fe(1)–C(1) | 1.785 (5) | 1.786 (4) | Fe(2)–Fe(1)–C(1) | 78.55 (16) | 73.20 (13) |

| Fe(2)–C(1) | 2.833 | 2.678 | Fe(2)–Fe(1)–P(1) | 136.39 (3) | 135.44 (2) |

| Fe(1)–P(1) | 2.2387 (11) | 2.2369 (8) | P(1)–Fe(1)–C(1) | 92.15 (12) | 93.86 (10) |

| Fe(2)–C(2) | 1.774 (4) | 1.787 (3) | Fe(1)–Fe(2)–C(2) | 103.25 (13) | 108.92 (10) |

| Fe(2)–P(2) | 2.2830 (15) | 2.2273 (15) | Fe(1)–Fe(2)–P(2) | 154.09 (5) | 147.79 (5) |

| C(1)–O(1) | 1.147 (6) | 1.148 (5) | P(2)–Fe(2)–C(2) | 94.63 (13) | 94.37 (18) |

| C(2)–O(2) | 1.139 (5) | 1.142(4) | C(2) –Fe(2)–C(2A) | 91.9 (3) | 93.0 (2) |

| Fe(1)–C(1)–O(1) | 173.0 (5) | 171.2 (4) | |||

| Fe(2) –C(2)–O(2) | 175.8 (4) | 177.8 (3) |

Frozen solution EPR spectra of the mixed-valence Pi-Pr3 and PCy3 complexes exhibit patterns with doublet features indicating that the SOMO is localized on the Fe(CO)2(PR3) center, in contrast to the behavior of the PMe3 complexes (Figure 5). The EPR data for [4edt]+, [5edt]+, and [5pdt]+ are very similar with respect to g and A values (Table 1). The A(31P) values for these doublets are similar to the previously observed A values for the triplets seen for [3edt]+ and [3pdt]+. Upon warming a sample of [5pdt]+ to −40 °C, whereupon the solvent is melts, the signal merges to give an isotropic doublet, consistent with the SOMO being localized on the Fe(CO)2(Pi-Pr3) center.

The carbonylation of [5edt]+ (1 atm, −45 °C) proceeded more slowly (~30 min) than for [3edt]+, which implicates a geometric rearrangement of the phosphine ligands. The EPR spectrum of the adduct [5edtCO]+ matched that observed for [3edtCO]+, i.e., one large and two smaller A(31P) values (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected EPR Parameters for [Fe2(S2CxH2x)(μ-CO)(CO)3L(dppv)]BF4 (Spectra Recorded at 110K (−163 °C), in 1:1 CH2Cl2:toluene)

| Complex | gz | Azz | gy | Ayy | gx | Axx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3edtCO]+ | 1.9943 | 323, 39, 42 | 1.9740 | 263, 28, 30 | 2.0073 | 258, 30, 33 |

| [3pdtCO]+ | 1.9976 | 30, 40, 36 | 1.9814 | 24, 30, 26 | 2.0131 | 24, 31, 26 |

| [5edtCO]+ | 1.9939 | 313, 36, 33 | 1.9750 | 254, 30, 28 | 2.0075 | 255, 27, 27 |

Crystallographic Characterization of [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PR3)(dppv)]BF4 (R = Me, i-Pr)

Crystals of these salts were grown at low temperatures. The [3pdt]+ salt is unsolvated while [5pdt]+ crystallized with a CH2Cl2 in the lattice; for both complexes the BF4− is well separated from the cationic diiron centers (Figure 6, Table 3). The cations adopt the expected structure wherein the terminal ligands on the quasi-octahedral Fe centers are staggered but that the Fe(CO)(dppv) adopts the “rotated” geometry. The CH---Fe(1) distance is 2.49 Å in [3pdt]BF4, respectively beyond the limit recognized for an agostic interaction.17 The greater steric bulk of the S2C3H6 vs S2C2H4 is manifested in the rotation of the pair of phenyl groups that surround the vacant coordination site. That angle increases as follows: 4° ([3edt]BF4), 14° ([3pdt]BF4), and 33° ([5pdt]BF4), reflecting a slightly increased tilting of the dithiolate toward the rotated Fe (the angle of the axial R3P-Fe-S, [3pdt]+ = 105.11 (15)° and [5pdt]+ = 107.93°), although the CH---Fe(1) distance does not contract further.

Figure 6.

Structure of the cations in [3pdt]BF4 and [5pdt]BF4with thermal ellipsoids set at 35% level. Phenyl ellipsoids, hydrogen atoms, and the BF4− were omitted for clarity.

Small but significant differences are observed between the Fe-P distances for [3pdt]BF4 and [5pdt]BF4. Specifically, the Fe-Pi-Pr3 distance is 2.2830(15) Å, which is 0.06 Å longer than the Fe-PMe3 distance in [3pdt]BF4. The Fe-P(dppv) distances are the same in both [3pdt]BF4 and [5pdt]BF4. This elongated Fe-P distance is consistent with steric conjestion at this site.

Since the EPR and the crystallographic data for [5pdt]BF4 do not agree, we considered the possibility that the solution structure differs from that observed in the single crystals. Indeed, an IR spectrum of a solid sample (KBr) prepared from single crystals differ distinctly from spectra for [5pdt]+, both as a solution and as a rapidly precipitated solid (Figure 7). Significantly, the IR band at 1958 cm−1 for the rapidly precipitated solid is absent in the spectrum of the crystals. Furthermore, the νμ-CO band at 1825 cm−1 in the rapidly precipitated material is not present in the crystalline material. When the single crystals were redissolved in CH2Cl2 (−45 °C), the solution IR spectrum matched that for a solution of [5pdt]+. As a control, we demonstrated that the similarity of the IR spectra for solid (KBr) and solutions of [3pdt]BF4, νΔ-CO = −3 cm−1 (see Supporting Information). It was not practical to compare the spectra of solution vs solid [5edt]BF4, which is far less stable than [5pdt]BF4.

Figure 7.

IR spectra (KBr) of [5pdt]BF4 that was rapidly precipitated (top) and single crystals grown at −20 °C (bottom).

DFT Calculations

Structures, relative stabilities, and electronic properties of different mixed valence models were studied by BP86/TZVP DFT calculations. Three families of model complexes, differing in the size of phosphine ligands, have been analyzed: [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PH3)3]+, [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]+(corresponding to [3xdt]+) and [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]+ (corresponding to [5xdt]+). In each family, both edt and pdt complexes have been considered. Hereafter, the Fe atoms coordinated by one and two phosphorus ligands will be referred to as Fecc and Fec, respectively.

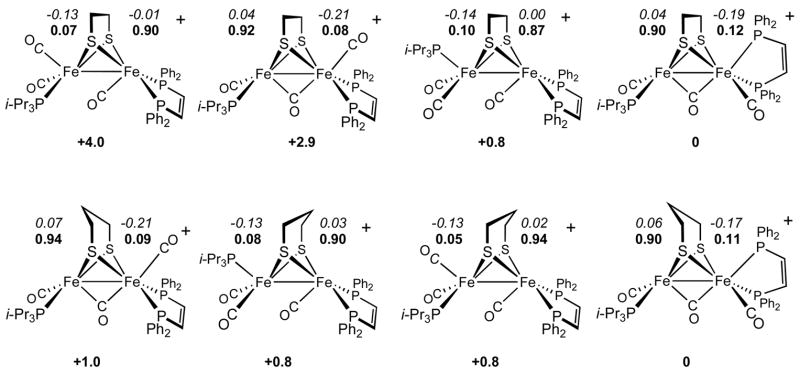

For [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PH3)3]+, the lowest energy isomer (see Supporting Information) is characterized by PH3 ligands in basal sites, and the Fecc(unrotated)-μ-C(O) distance (2.438 Å) is long. Analogous results are obtained for the [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]+ family (see Supporting Information), indicating that the replacement of PH3 ligands with dppv and PMe3 does not strongly affect the properties of the binuclear cluster. In both families ((PH3)3 and dppv-PMe3), the energy difference between the most stable isomer and the other isomeric forms is greater for pdt than edt, due to increased steric clashing between apical P ligands and pdt. This situation is reversed when PMe3 is replaced by Pi-Pr3, where the calculations suggest that rotation of Fecc and Fec are nearly isoenergetic (Δ;E = 0.8 kcal/mol, Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Computed relative stabilities (kcal/mol), spin densities, and NBO partial atomic charges (italics) for relevant isomers of [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]+.

In the lowest-energy [5xdt]+ isomer, the apical vacant coordination site is located on Fecc. Moreover, relative to the corresponding (PH3)3 and (PMe3)(dppv) cases, the μ-CO group is more symmetrically bridging. This finding is consistent with our IR data that show that νμ-CO is 1830 cm−1 for [5pdt]+ vs 1889 cm−1 for [3pdt]+. The relative stability of the isomers is strongly influenced by the bulkiness of the monophosphine ligand. Steric clashing is minimized when Pi-Pr3 occupies a basal position trans from the basal end of the dppv chelate ring (Scheme 4, Figure 8).

Figure 8.

DFT structure of the lowest energy isomer of [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]+ ([5pdt]+). Atoms are color coded as follows: carbon, green; oxygen, red; sulfur, yellow; phosphorus, purple; iron, cyan.

Our analysis of the electronic properties of [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PH3)3]+, [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]+, and [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]+ reveals that the unpaired electron is always localized on the iron atom featuring a vacant apical coordination position, i.e., Fecc in [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PH3)3]+ and [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]+, and Fecc in [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]+. This picture is consistent with previous DFT studies carried out on models,7 as well as on the H-cluster.18,19 Recent pulsed EPR analysis of the the Hox state of the enzyme indicates that the unpaired electron is more localized on the non-rotated (proximal) iron.20 This apparent discrepancy between theoretical/model and biophysical data may reflect subtle effects due to the H-cluster environment.18 Our oxidation state assignments agree with earlier calculations by Brunold on the entire 6Fe H-cluster19 as well as the results from Hall et al. on a related model containing carbene ligand on the rotated iron site.7

Notably, the analysis of computed partial atomic charges for [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PH3)3]+, [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]+, and [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]+ shows that the more electrophilic metal center always corresponds to the Fe atom featuring a vacant apical coordination position (Scheme 4). Therefore, in this class of compounds, the assignment of the Fe(I) oxidation state to the iron center carrying the unpaired electron should be taken as purely formal.

Oxidation of [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)(CO)3(dppv)]−

We examined the oxidation of the cyanide complex Bu4N[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)(CO)3(dppv)], Bu4N[6edt].12 This anionic complex was expected to be more easily oxidized than the related PMe3 derivative 3edt and thus a potential precursor to a mixed-valence cyanide. Cyclic voltammetry indicated that this species oxidizes at −130 mV, 150 mV more cathodic than [3edt]0/+ couple. Unlike the voltammogram for the PMe3 derivative, however, the oxidation of the cyanide was electrochemically irreversible, it re-reduces at −600 mV (ΔEp ~ 500 mV). The i-V response is reminiscent of an EC process, whereby oxidation induces an irreversible chemical reaction. The CV remained unchanged even at scan rates up to 500 mV/s.

In a preparative-scale oxidation, treatment of a CH2Cl2 solution of Bu4N[6edt] with one equiv of FcBF4 afforded a thermally stable, toluene-soluble complex that proved to be diamagnetic. This species is assigned as a four-iron compound [6edt]2. Unlike the behavior of related phosphine complexes discussed above and elsewhere,5,8 this oxidation was unaffected by the presence of CO, indicating the absence of long-lived unsaturated species. The corresponding two-electron oxidation of Bu4N[6edt] in MeCN solution gives Cs-symmetric [Fe2(S2C2H4)(μ-CO)(CO)2(CN)(NCMe)(dppv)]+.12

The 31P NMR spectrum of [6edt]2 consisted of a broad singlet at δ 95 and a sharp singlet at δ 74.5. The low field signal is characteristic of dppv dynamically spanning apical and basal sites on diiron(I) species. A similar structure is assumed for Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv), which exhibits a single 31P NMR resonance at δ 94.7.12 The sharp higher field signal is consistent with dppv on dibasal sites on diiron(II) derivatives, e.g. [Fe2(S2C2H4)(μ-CO)(CO)2(PMe3)(NCMe)(dppv)](BF4)2 (δ 74.6).12 Upon cooling the solution, each of these two signals split. The lower field signal split more, consistent with the presence of both apical and basal phosphine ligands on a diiron(I) center, whereas the splitting of the higher field signal is small (2 ppm) because the electronic asymmetry is modest, consistent with this dppv being dibasal. The IR spectrum of this charge-neutral complex resembles the sum of the spectra of [Fe2(S2C2H4)(μ-CO)(CO)2(PMe3)(MeCN)(dppv)]2+ (2058 and 2016 cm−1) and the starting complex (1952 and 1901 cm−1). The 1952 and 1901 cm−1 bands assigned to the Fe(I)-Fe(I) center occur at ~10 cm−1 higher energy than in Bu4N[6edt], consistent with the attachment of an electrophile to the FeCN. These data are consistent with the formulation [FeI2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(dppv)](μ-CN)[FeII2(S2C2H4)(μ-CO)(CN)(CO)2(dppv)] (Scheme 5). Further characterization of the charge-neutral product via mass spectroscopy was unsuccessful.

Scheme 5.

Redox reactivity proposed for [Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)(CO)3(dppv)]−.

Discussion

Oxidation of diiron dithiolato carbonyls produces highly unsymmetrical derivatives featuring a single “rotated” iron center and a semi-bridging CO ligand. Relief of steric strain influences the regiochemistry of the oxidation, i.e., the bulkier Fe center undergoes rotation. The rotation desymmetrizes the diiron center, localizing the mixed valency as indicated by EPR spectra. Addition of CO to the mixed valence species re-symmetrizes the diiron center, leading to a more delocalized mixed-valence system.8 The central feature of these models is that the iron center that undergoes the redox-induced rearrangement remains in the Fe(I) oxidation state, whereas the iron center that undergoes oxidation remains in the same geometry and becomes coordinatively saturated. The square pyramidal iron(I) center is unsaturated and electrophilic.

Effects of Coligands on Mixed-Valency

The EPR spectra of [2pdt]+, [3edt]+, and [3pdt]+ are very similar as are the crystal structures for the latter two. The rotated nature of the Fe(CO)(dppv) center was crystallographically verified for both [3pdt]+ and [3edt]+, and we assume that a similar structure applies to the corresponding tetracarbonyl [2pdt]+. In face of this pattern, the EPR results are strikingly different when PMe3 is replaced by Pi-Pr3 and PCy3. Specifically, the EPR results indicate that the spin is located on the Fe(CO)2PR3 center in these bulkier complexes. The crystallography shows, however, that the Fe(CO)(dppv) remains rotated in [5pdt]BF4, but we suggest that the FeI(CO)2(Pi-Pr3) site is rotated in solution. DFT calculations indicate that the bulkier phosphine slightly favors rotation at the monophosphine site. Pi-Pr3 and PMe3 have comparable pKa‘s of ~9.7 (for PCy3, which we assume is similar to Pi-Pr3) and 8.65 (PMe3, compare 2.73 for PPh3).20 Pi-Pr3 is, however, much larger than PMe3 with a cone angle of 160º (vs 118º).21 The influence of PMe3 vs Pi-Pr3 on the regiochemistry of the oxidation is also supported by the IR data as well as the electrochemical results. Compound [5pdt]+ resembles the active site to the extent that it features two donor ligands and one CO on the “proximal” Fe center and one donor ligand and two CO’s on the “distal” (rotated) Fe center (eq 3).

For the sake of completeness, we note that the EPR results qualitatively support two distinct descriptions, L3FeII(SR)2FeIL3, which we favor,5,7,22 and L3FeIII(SR)2Fe0L3, which has not been discussed. The 0,III description would be consistent with oxidation occurring at the more electron-rich iron center, and implies that oxidation and rotation induce a redox change at both iron centers, i.e., L3FeI(SR)2FeIL3 → L3Fe0(SR)2FeIIIL3. “Dative metal-metal bonds” have been invoked to describe compounds with such disparate oxidation states.23 Precedents for ferric carbonyls include [Cp2Fe2(SMe)2(CO)2]2+ (νCO ~ 2060 cm−1)24 and the dithiocarbamate [(C5Me5)Fe(S2CNEt2)(CO)]+.25 The oxidation state assignments will be further probed through studies on the Mössbauer spectra of these compounds.

Site Isolation

For low molecular weight models, a recurring question concerns the extent to which the synthetic ligands can or need to emulate the steric shielding provided by the protein. The issue is pertinent since the H-cluster is deeply imbedded in both of the structurally characterized proteins.26 The present results highlight continuing problems that hamper the preparation of unsaturated models featuring cyanide ligands. Specifically, we showed that oxidation of a diiron cyanide leads to aggregation via formation of a μ-CN bridge. This conversion, a disproportionation, is explicable in terms of an inner sphere mechanism facilitated by the ambidentate nature of cyanide. For the present generation of models, however, tertiary phosphine ligands serve as useful surrogates for cyanide, with the advantages that their electronic and steric properties can be manipulated as we showed in this paper.

Outlook

The chemistry of mixed-valence models for the diiron active site of the [FeFe]-hydrogenases has evolved such that many details can be evaluated. For example, the nature of the dithiolate as well as the basicity and size of the coligands significantly influence the mixed valency and affect the reactivity of these species toward CO. These results will guide further efforts to understand of how substituents affect the interaction of diiron dithiolato centers toward small molecules, including H2.

Experimental Section

Materials and methods (EPR and IR spectroscopy, and cyclic voltammetry) have recently been described.8 [CpFe(C5H4Ac)]BF4 was prepared by literature methods.13 The diiron complexes Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv), Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)4(dppv), Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv), Et4N[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)(CO)3(dppv)] have been previously described.12 NMR spectra were recorded at room temperature on a Varian Mercury 500 MHz spectrometer (202 MHz for 31P).

X-ray Crystallography

Crystals were mounted to a thin glass fiber using Paratone-N oil (Exxon). Data, collected at 198 K on a Siemens CCD diffractometer, were filtered to remove statistical outliers. The integration software (SAINT) was used to test for crystal decay as a bi-linear function of X-ray exposure time and sin(Θ). The data were solved using SHELXTL by Direct Methods (Table 4); atomic positions were deduced from an E map or by an unweighted difference Fourier synthesis. H atom U’s were assigned as 1.2Ueq for adjacent C atoms. Non-H atoms were refined anisotropically. Successful convergence of the full-matrix least-squares refinement of F2 was indicated by the maximum shift/error for the final cycle.

Table 4.

Details of Data Collection and Structure Refinement for Crystallography.

| Complex | [3pdt]BF4 | [5pdt]BF4 |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical formula | C35H37BF4Fe2O3P3S2 | C41H49BF4Fe2O3P3S2 |

| Temperature (K) | 193 (2) | 193 (2) |

| Crystal size (mm3) | 0.28 × 0.12 × 0.06 | 0.31 × 0.08 × 0.08 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | Pnma | P21/m |

| a (Å) | 23.5362 (7) | 9.2644 (7) |

| b (Å) | 18.3985 (5) | 16.1182 (12) |

| c (Å) | 8.5950 (2) | 16.1141 (12) |

| α(°) | 90 | 90 |

| β(°) | 90 | 105.462 (2) |

| γ(°) | 90 | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 3721.90 (17) | 2319.2 (3) |

| Z | 4 | 2 |

| Density calcd (Mg m−3) | 1.537 | 1.475 |

| μ(Mo Kα, mm−1) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| max./min. trans’n | 0.9422/0.8116 | 0.9323/0.7729 |

| reflections meas’d/Indep. | 47014/3695 | 27790/4544 |

| data/restraints/parameters | 3695/261/339 | 4544/503/471 |

| GOF on F2 | 1.083 | 1.069 |

| Rint | 0.0623 | 0.0431 |

| R1 [I > 2σ] (all data)a | 0.0380 (0.0552) | 0.0505 (0.0642) |

| wR2 [I > 2σ] (all data)b | 0.0904 (0.1003) | 0.1328 (0.1414) |

| max. peak/hole (e−/Å3) | 0.715/−0.322 | 1.036/−0.548 |

R1 = Σ|Fo|−|Fc|/Σ|Fo|

wR2 = {[w(|Fo|−|Fc|)2]/Σ[wFo2]}1/2, where w = 1/σ2 (Fo)

EPR Spectroscopy

The following procedure is illustrative: a solution of 0.010 g (0.0116 mmol) of Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv) in 6 mL of CH2Cl2 (−45 °C) was treated with a solution of 0.003 g (0.0112 mmol) of FcBF4 in 6 mL of CH2Cl2. The resulting solution (1 mM) was transferred via cannula to a chilled (−78 °C) EPR tube that had been purged with N2. The EPR tube was cooled with liquid nitrogen and flame-sealed under vacuum.

Spin concentrations were determined by double integrating baseline corrected spectra. For calibration, a sample containing 1 mM CuSO4 in a 20% glycerol solution was recorded at the same power, modulation amplitude, and temperature as that used for the diiron samples. In this way, the spin concentration of three samples, nominally 1mM, of [3pdt]BF4 were found to be 0.60, 0.60, and 0.70 mM.

DFT Calculations

DFT calculations were carried out using the BP86 functional27 and a valence triple-ζ basis set with polarization on all atoms (TZVP).28

[Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)4(dppv)]BF4 ([2pdt]BF4)

A solution of 0.250 g (0.344 mmol) of Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)4(dppv) in 15 mL of CH2Cl2 at −45 °C was treated with a solution of 0.094 g (0.344 mmol) of FcBF4 in 10 mL of CH2Cl2. The purple solution was rapidly transferred into 400 mL of hexane cooled to −78 °C. The supernatant solvent was siphoned away from the finely divided solid. Yield: 0.152 g (54%). IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2076, 2020, 1943 cm−1. IR (solid KBr): νCO = 2075, 2012, 1934, 1906 (sh) cm−1.

[Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]BF4 ([3pdt]BF4)

A solution of 0.200 g (0.258 mmol) of Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv) in 10 mL of CH2Cl2 at −45 °C was treated with a solution of 0.070 g (0.258 mmol) of FcBF4 in 10 mL of CH2Cl2. The purple solution was transferred into 400 mL of hexane at −78 °C. The supernatant was removed by cannula. Crystals were grown from the liquid diffusion of hexane into a CH2Cl2 solution at −20 °C. Yield: 0.171 g (70%). IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2015, 1962, 1889 cm−1. IR (solid KBr): νCO = 2007, 1950, 1886 cm−1.

When CH2Cl2 solutions of [3pdt]BF4 were exposed to CO (1 atm at −45 °C). The in-situ IR spectrum showed the disappearance of [3pdt]BF4 and the growth of new peaks, attributed to [Fe2(S2C3H6)(μ-CO)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]BF4, [3pdtCO]BF4. Due to the instability of [3pdtCO]BF4 all data were collected in-situ. IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2018, 1984, 1791 cm−1. Conversion of [3pdt]+ to [3pdtCO]+ using ~1 atm CO required ~10 min.

Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(PCy3)(dppv) (4edt)

A solution of 0.300 g (0.421 mmol) of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv) in 40 mL of toluene was treated with 0.130 g (0.421 mmol) of PCy3 in 10 mL of toluene. The reaction mixture was photolyzed with a 100 W UV immersion lamp, λmax = 356 nm (Spectroline), until the conversion was complete (~36 h) as indicated by IR spectroscopy. The solvent was removed in vacuum, and the product extracted into 20 mL of CH2Cl2. The solution was concentrated to ~5 mL, and the red-brown product precipitated upon addition of 40 mL of hexanes. Yield: 0.352 g (86 %). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 7.98 – 7.29 (m, 20H, C6H5), 2.01 – 0.89 (m, 70H, P(C6H22)3, SCH2CH2S). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 93.96 (bs), 62.53 (s) at 20 °C. IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 1953, 1901 cm−1. FD-MS: m/z 964.4 ([Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(PCy3)(dppv)]+). Anal. Calcd for C49H59Fe2O3P3S2 (Found): C, 61.00 (61.38); H, 6.16 (6.50).

[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(PCy3)(dppv)]BF4 ([4pdt]BF4)

A solution of 0.050 g (0.052 mmol) of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(PCy3)(dppv) in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 at −45 °C was treated with 14 mg (0.052 mmol) of FcBF4 in 3 mL of CH2Cl2. IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 1987 (m), 1961 (s), 1870 (br) cm−1.

Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv) (5edt)

A solution of 0.300 g (0.421 mmol) of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)4(dppv) in 40 mL of toluene was treated with 0.27 mL (2.105 mmol) of Pi-Pr3. The reaction mixture was photolyzed with a 100 W UV immersion lamp, λmax = 356 nm (Spectroline) until the conversion was complete (~24 h) as indicated by IR spectra. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the product was extracted into ~20 mL of CH2Cl2. The solution was concentrated to ~5 mL, and the red-brown product was precipitated upon addition of 40 mL of hexanes to this solution. Yield: 0.268 g (75%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 7.98 – 7.27 (m, 20H, C6H5), 2.00 (m, 3H, P(CH)Me2), 1.56 (m, 2H, SCH2), 1.26 (m, 18H, PCH(CH3)2), 1.18 (s, 2H, SCH2). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 92.96 (bs), 71.74 (s) at 20 °C. 95.9 (d, JP-P = 25 Hz), 91.6 (d, JP-P = 25 Hz), 71.1 (s) at −60 °C. IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 1954, 1903 cm−1. FD-MS: m/z 844.4 ([Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]+). Anal Calcd for C40H47Fe2O3P3S2 (Found): C, 56.89 (56.97); H, 5.61 (5.45).

Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv) (5pdt)

See preceding preparation. Yield: 71%. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 8.00 – 7.30 (m, 20H, C6H5), 2.38 (m, 3H, PCHMe2), 1.67 (s, 2H, SCH2), 1.55 (s, 2H, SCH2CH2CH2S), 1.37 (m, 18H, PCH(CH3)2), 1.25 (s, 2H, SCH2). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 90.69 (s), 72.94 (s). At −80 °C, the δ 90.69 signal is broad. IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 1954, 1901 cm−1. FD-MS: m/z 858.3 ([Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]+). Anal Calcd for C41H49Fe2O3P3S2 (Found): C, 57.36 (57.01); H, 5.75 (5.69).

[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]BF4 ([5edt]BF4)

A solution of 0.050 g (0.052 mmol) of Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv) in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 at −45 °C was treated with 14 mg (0.052 mmol) of FcBF4 in 3 mL of CH2Cl2. Due to the instability of [5edt]BF4, all data were collected in-situ. IR (CH2Cl2): 3CO = 1987 (m), 1968 (s), 1870 (br) cm−1.

When CH2Cl2 solutions of [5edt]BF4 were exposed to CO (1 atm at −45 °C). The in-situ IR spectrum showed the disappearance of [5edt]BF4 and the growth of new peaks, attributed to [Fe2(S2C3H6)(μ-CO)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]BF4, [5edtCO]BF4. Due to the instability of [5edtCO]BF4, all data were collected in-situ. IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2022, 1987, 1968, 1787 cm−1. The reaction of CO with [5edt]+ to form [5edtCO]+ required ~30 min.

[Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]BF4 ([5pdt]BF4)

A solution of 0.150 g (0.175 mmol) of Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv) in 20 mL of CH2Cl2 at −45 °C was treated with 0.047 mg (0.175 mmol) of FcBF4 in 10 mL of CH2Cl2. The solution was transferred via cannula to 400 mL of hexane cooled to −78 °C to precipitate the red-brown solid. Single crystals were grown by diffusion of a layer of hexane into a CH2Cl2 solution at −20 °C. IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2011 (sm), 1988 (m), 1968 (s), 1830 (br) cm−1. IR of rapidly precipitated solid (KBr): νCO = 1998 (m), 1958 (s), 1904 (sm), 1824 (br) cm−1. IR of pulverized single crystals (KBr): νCO = 1990 (s), 1931 (s), 1903 (m) cm−1.

[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)(CO)3(dppv)]2 ([6edt]2)

A solution of 0.050 g (0.0525 mmol) of Bu4N[Fe2(S2C2H4)(CN)(CO)3(dppv)] in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 was treated with 0.014 g (0.0525 mmol) of FcBF4 in 5.0 mL of CH2Cl2. Solvent was removed in vacuo, and the product was extracted into 20 mL of toluene. The orange solution was concentrated to 5 mL, and the product precipitated upon addition of 30 mL of hexanes. 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 92.96 (bs), 71.74 (s). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, −60 °C): 99.1 (d, JP-P = 21 Hz), 92.7 (d, JP-P = 21 Hz), 75.9 (s), 74.0 (s). IR (CH2Cl2): νCN = 2136, 2116 cm−1. IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2074 (sh), 2058 (s), 2016 (m), 1975 (m), 1952 (s), 1901 (s) cm−1.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Crystallographic data for [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]BF4 and [Fe2(S2C3H6)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]BF4, voltammograms, as well as IR, EPR, and NMR spectra. For DFT calculations: atomic coordinates, energy values, spin populations and partial atomic charges for the DFT models [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PH3)3]+, [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PMe3)(dppv)]+, and [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(Pi-Pr3)(dppv)]+. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at …

References

- 1.Liu X, Ibrahim SK, Tard C, Pickett CJ. Coord Chem Rev. 2005;249:1641–1652. [Google Scholar]; Tard C, Liu X, Ibrahim SK, Bruschi M, De Gioia L, Davies SC, Yang X, Wang LS, Sawers G, Pickett CJ. Nature. 2005;433:610–4. doi: 10.1038/nature03298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Lacey AL, Fernández VM, Rousset M, Cammack R. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4304–4330. doi: 10.1021/cr0501947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fontecilla-Camps JC, Volbeda A, Cavazza C, Nicolet Y. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4273–4303. doi: 10.1021/cr050195z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lubitz W, Reijerse E, van Gastel M. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4331–4365. doi: 10.1021/cr050186q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Vignais PM, Billoud B. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4206–4272. doi: 10.1021/cr050196r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu T, Darensbourg MY. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7008–9. doi: 10.1021/ja071851a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Justice AK, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:6152–6154. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Justice AK, Zampella G, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB. Chem Commun. 2007:2019–21. doi: 10.1039/b700754j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas CM, Darensbourg MY, Hall MB. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101:1752–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Justice AK, Nilges M, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR, Zampella G. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5293–5301. doi: 10.1021/ja7113008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt M, Contakes SM, Rauchfuss TB. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9736–7. [Google Scholar]; Lyon EJ, Georgakaki IP, Reibenspies JH, Darensbourg MY. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1999;38:3178–3180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Le Cloirec A, Davies SC, Evans DJ, Hughes DL, Pickett CJ, Best SP, Borg S. Chem Commun. 1999:2285–2286. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao X, Georgakaki IP, Miller ML, Yarbrough JC, Darensbourg MY. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9710–9711. doi: 10.1021/ja0167046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Razavet M, Borg SJ, George SJ, Best SP, Fairhurst SA, Pickett CJ. Chem Commun. 2002:700–701. doi: 10.1039/b111613b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyke CA, van der Vlugt JI, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR, Zampella G, De Gioia L. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11010–11018. doi: 10.1021/ja051584d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Justice AK, Zampella G, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB, van der Vlugt JI, Wilson SR. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:1655–1664. doi: 10.1021/ic0618706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connelly NG, Geiger WE. Chem Rev. 1996;96:877–922. doi: 10.1021/cr940053x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen MT, Justice AK, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR. in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyke CA, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR, Rohmer MM, Bénard M. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15151–15160. doi: 10.1021/ja049050k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacNeil JH, Chiverton AC, Fortier S, Baird MC, Hynes RC, Williams AJ, Preston KF, Ziegler T. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:9834–9842. [Google Scholar]; Baker PK, Connelly NG, Jones BMR, Maher JP, Somers KR. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1980:579–585. And references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brookhart M, Green MLH, Parkin G. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:6908–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.To probe the possibility that the spin could reside on the non-rotated site, we have carried out time-dependent DFT calculations on [Fe2(S2CnH2n)(CO)3(PH3)3]+, evaluating the possible presence of low-lying excited states in which the unpaired electron is not localized on the Fe atom featuring vacant apical coordination site. We found that the lowest-energy excited state is about 23 kcal/mol higher in energy than the ground state. More importantly, in the excited state the spin density distribution was largely unaffected.

- 19.Fiedler AT, Brunold TC. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:9322–9334. doi: 10.1021/ic050946f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bush RC, Angelici RJ. Inorg Chem. 1988;27:681–686. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolman CA. Chem Rev. 1977;77:313–48. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silakov A, Reijerse EJ, Albracht SPJ, Hatchikian EC, Lubitz W. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11447–11458. doi: 10.1021/ja072592s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang F, Jenkins HA, Biradha K, Davis HB, Pomeroy RK, Zaworotko MJ. Organometallics. 2000;19:5049–5062. [Google Scholar]; Jiang F, Biradha K, Leong WK, Pomeroy RK, Zaworotko MJ. Can J Chem. 1999;77:1327–1335. [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Beer JA, Haines RJ, Greatrex R, van Wyk JA. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1973:2341. [Google Scholar]; Vergamini PJ, Kubas GJ. Prog Inorg Chem. 1976;21:261–82. [Google Scholar]; Madec P, Muir KW, Pétillon FY, Rumin R, Scaon Y, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1999:2371–2384. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delville-Desbois MH, Mross S, Astruc D, Linares J, Varret F, Rabaâ H, Le Beuze A, Saillard JY, Culp RD, Atwood DA, Cowley AH. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:4133–47. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandey AS, Harris TV, Giles LJ, Peters JW, Szilagyi RK. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4533–4540. doi: 10.1021/ja711187e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nicolet Y, Lemon BJ, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Peters JW. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:138–143. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01536-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becke AD. J Chem Phys. 1986;84:4524–4529. [Google Scholar]; Perdew JP. Phys Rev. 1986;B33:8882. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaefer A, Huber C, Ahlrichs R. J Chem Phys. 1994;100:5829–35. [Google Scholar]