Abstract

This study sought to identify how urban gay communities are undergoing structural change, reasons for that change, and implications for HIV prevention planning. Key informants (N=29) at the AIDS Impact Conference from 17 cities in 14 countries completed surveys and participated in a facilitated structured dialog about how gay communities are changing. In all cities, the virtual gay community was identified as now larger than the offline physical community. Most cities identified that while the gay population in their cities appeared stable or growing, the gay community appeared in decline. Measures included greater integration of heterosexuals into historically gay-identified neighborhoods and movement of gay persons into suburbs, decreased number of gay bars and clubs, less attendance at gay events, less volunteerism in gay or AIDS organizations and overall identification and visibility as a gay community. Participants attributed structural change to multiple factors including gay neighborhood gentrification, achievement of civil rights, less discrimination, a vibrant virtual community and changes in drug use. Consistent with social assimilation, across cities, gay infrastructure, visibility and community identification appears to be decreasing. HIV prevention planning, interventions, treatment services, and policies need to be re-conceptualized for MSM in post-gay communities. Four recommendations for future HIV prevention and research are detailed.

Keywords: Structural Interventions, Gay Community Change, HIV Risk, Resurgent HIV Epidemic, Unsafe Sex

Since the mid 1990s, many cities in North America, Europe, Australia and elsewhere have reported disturbing increases in sexual risk behaviors, sexually transmissible infections, and in some cities HIV, among men who have sex with men (MSM) (UNAIDS, 2006). Analyzing why an HIV/STI resurgent epidemic is occurring among MSM, internationally, is among the greatest challenges facing HIV-prevention research (CDC, 2001a,b; Gross, 2003). Intra-individual level factors such as safer sex fatigue (Morin et al., 2003) and complacency (Valdiserri, 2004) have been identified; while meta-analyses have examined the likely impact of Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy (HAART) (Crepaz et al., 2004) and the Internet (Liau et al., 2006) on risk behavior. While such approaches provide detailed examination of individual factors, we were unable to find any studies examining how organizational, institutional, community and societal level factors may be changing the gay community, and thus influencing MSM’s risk.

Structural research is defined as studies of variables beyond an individual’s control which nevertheless influence their behavior (Sumartojo, 2000). These factors can include (but are not limited to) the physical, social, cultural, economic, legal, and political dimensions of an environment, which in turn facilitate or impede HIV transmission (Sumartojo et al., 2000). Despite their potential for lowering HIV prevalence rates and identifying new approaches to long-term HIV prevention (Blankenship et al., 2000), few studies have examined the impact of structural factors on HIV prevention targeting MSM. Those which have appear restricted to environmental studies of sexual risk behavior by MSM in bathhouses and sex clubs (Bayer, 1989; De Wit et al., 1997; Morris and Dean, 1994; Wohlfeiler, 2000; Woods and Binson, 2003). In addition, a study by our team evaluating HIV prevention for MSM in thirteen rural states of the U.S. found gay community-level factors predicted success in HIV prevention on 6 of 9 measures (Rosser and Horvath, 2007). However, this study focused on HIV prevention in rural states, and we could find no equivalent study evaluating HIV prevention for MSM in urban areas.

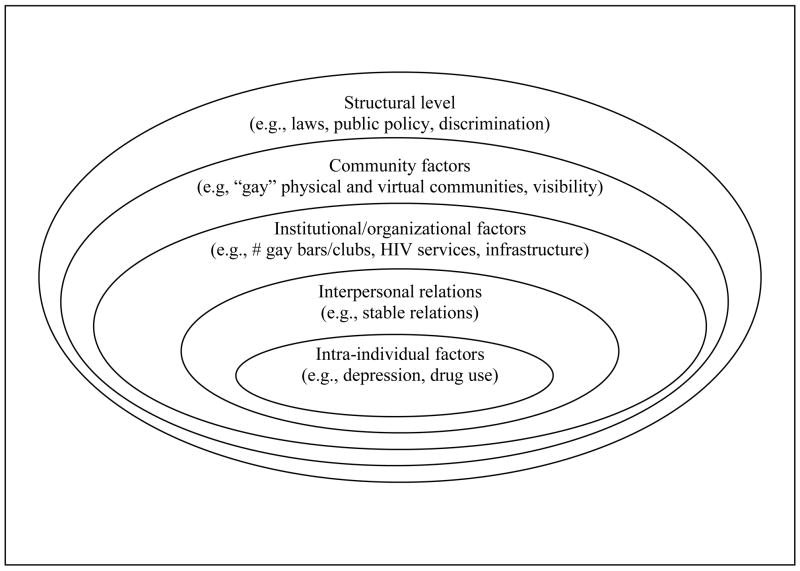

In conceptualizing this study, we applied the ecological model of health behavior (McLeroy et al., 1988) to HIV risk among MSM (see Figure 1). At the intra-individual level -- the level most easily and frequently studied -- in addition to safer sex fatigue and complacency, HIV status, alcohol and drug use, intentions to use condoms, commitment to safer sex, sexual history, mental health and internalized homonegativity have all been shown to influence risk (see Ross et al., 2004; Rosser et al., 2007). Interpersonal factors known to influence HIV risk include whether sex occurs in a long-term or casual relationship, HIV status disclosures, demographic differences between partners (e.g., economic, race), and domestic violence (see Hayes et al., 1997; Relf et al., 2004). Organizational level factors include not only availability of HIV-specific prevention and treatment services, but also number of gay venues and social groups, and virtual communities (e.g., gay sex sites) which modify risk behavior (Rosser and Horvath, 2007). At the community level, we hypothesize that dimensions of urban gay communities which may influence risk include physical concentration (e.g., density of gay neighborhoods), psychological affiliation (collective identification as a community), and social cohesiveness. At the broadest societal level, human rights and laws, societal discrimination, war, politics and economic climate, have all been identified as influencing the spread of HIV/STIs in various populations, and similarly likely influence the spread of HIV/STI among MSM; although studies at this level are rare.

Figure 1.

The ecological model of health behavior adapted for HIV prevention targeting gay men.

The broad objective of this study was to conduct a formative or exploratory examination of gay community change. Specifically, we sought to bring together key informants from many cities (a) to identify common changes in gay communities across cities; (b) to discuss factors influencing the change; and (c) to predict the likely impact on future HIV prevention and services for MSM.

Methods

Participants

HIV prevention experts, researchers, professionals and gay community leaders who attended the 8th AIDS Impact Conference in Marseille, France during July 2007 were invited to participate in a pre-conference workshop entitled, “Are Gay Communities Dying or Just in Transition?” Each participant was asked to identify one city in which he or she lived in (or had the greatest familiarity with), and for which they believed they could serve as a key informant. In total, 29 persons reported observations from the cities of Paris and Nantes (France), Copenhagen (Denmark), Malmö (Sweden), London (England), Amsterdam (the Netherlands), Tallin (Estonia), Warsaw (Poland), Prague (Czech Republic), Sophia (Bulgaria), Johannesburg (South Africa), Auckland (New Zealand), Sydney (Australia), New York, Miami and Minneapolis-St. Paul (United States) and Toronto (Canada).

Measures

To help participants think about change at the macro level, all participants completed a 15-item pen-and-paper survey about their gay community prior to the dialog. In the structured dialog, the first question asked whether participants considered their community to be undergoing major change, while a follow-up prompt asked them to identify the nature of the change. Next, changes specific to gay bars, drinking environments, and physical spaces were assessed. Legal changes were investigated by asking participants the impact of civil unions and/or gay marriage had on their gay communities and how it might change HIV-risk. Participants were also asked to identify other “hot” legal issues in their local gay communities. A series of questions assessed the positive and negative impact of Internet use including how big the online gay community is in comparison to the offline gay community. And finally, a question encouraged discussion on what factors were underlying these changes.

Procedures

A modified focus group format was used to solicit participants’ impressions. First, ground rules for the structured discussion were reviewed; namely, that participation was voluntary, and responses would be categorized by city but would otherwise be anonymous. Qualitative observations were audio taped during a facilitated structured dialog employing open-ended questions. Given the nature of the study, our Institutional Review Board deemed it exempt from review.

Results

Overall gay community

Participants from all cities, except London and New York, identified their gay communities as undergoing similar structural decline, although the reasons offered for this varied. “There’s less gay visibility, friendships, and increased isolation, less parties and more party by Internet” (Miami). “I see a dividing of the community around Pride; some people celebrate it and some won’t have anything to do with it” (Copenhagen). “There is a difference in South Africa between the rich gay community, which is becoming Internet-based and away from public participation, and the poor gay community which is becoming marginalized” (Johannesburg). “There is less solidarity among gay people; gay people seem less and less social” (Prague). “More people are online doing their own thing” (Sydney). New York and London, the largest two cities and the two exceptions, described their inner city gay communities as thriving.

Size of Gay Communities

Participants in all cities, except possible Copenhagen, described the size of the gay population as stable or increasing. In particular, participants from the former Communist Bloc in Eastern Europe described their gay communities as increasing in size, visibility and activism. “Warsaw is the place where gay people come because we have [got] more gay bars and places where people can meet. Small town and small village people come to Warsaw” (Warsaw).

Gay neighborhoods

In most cities, gay neighborhoods were described as disappearing, with gay men assimilating into suburban life. “Gay men are driven from traditional gay neighborhoods because of high real estate prices” (Auckland). “There are greater numbers of the straight community moving into gay neighborhoods; it’s become acceptable” (Toronto).

Gay bars and clubs

In almost all cities, the number and popularity of gay bars and clubs appears to be declining. “Bars have closed in the last 5–8 years and they have not been replaced. There are now maybe only two dance clubs, where 5–10 years ago they might have been 5–6” (Toronto). “We have decreased from 10 to 8 bars [but] more Internet use” (Copenhagen). “We now have only 1 bar remaining” (Auckland).

The bar population was also described as changing. “The bars were totally gay, [but] now they’re mixed” (Miami and five other cities). “The guys in the bars are getting older” (Amsterdam and five other cities). “If gay men like to go to dance parties, often they go to straight dance parties” (Auckland). The club scene has also become more subdued in these cities. “Before there could be parties every night. Now it’s only on the weekend. I regularly travel to many European cities and the medium cities are the same all over” (Copenhagen). Changes in drug use were cited as impacting bars. “The drugs part of the bar scene has changed. Doing drugs at home is a lot safer in people’s minds, so house parties, hotel parties, parties where they aren’t doormen and there isn’t security, is another reason for the bar scene to have fallen off” (Nantes). “Crystal meth is huge but the men buy a single bottle of water to last all night. So the bars are forced to increase a cover charge which means only to more affluent attend.” (New York). Exceptions to the decline in bars include inner-city London where the bar scene was described as vibrant, and cities in the former Eastern Bloc where gay bars were described as still emerging.

The Non-Bar scene

With the exception of the former Eastern Bloc cities, all participants reported marked decrease in political or religious organizations, decreased political involvement/interest, an increased commercialization of the gay community and more gay work organizations. “Organizations around political issues have disappeared. Gay Pride has changed. We’re seeing a huge increase in corporate sponsors like everybody’s in there; they want a piece of it. More corporate and less social activist groups” (Miami). “The trade unions … have really become part of the Pride in a way that they didn’t use to be. It’s a way of supporting the members and fighting discrimination” (London). “Mardi Gras is big business and increasingly mixed heterosexual and gay; [there is] increased drug use but decreased [sexual] decadence.” (Sydney). “On gay radio stations, there used to be community-based information or debate. Now it’s almost all music” (London).

Virtual Gay Community

Participants from all cities estimated their online (virtual) gay communities as larger than their offline (physical) communities. Identified impacts of the virtual community included businesses and bars closing down because of decreased patronage as well as decreased visibility of gay people on the streets. Participants from the Eastern Bloc noted it feels safer to talk on the Internet. Some integration between the online and offline environments was also noted. “In London, the largest cruising [Internet] site just opened up an enormous bar in the middle of town with a computer so you can cruise their site while you’re out drinking.” (London). “Bathhouses now have Internet hook-ups” (Copenhagen and six other cities).

Legal Rights

In cities where civil unions had been recognized for some years, same sex marriage was now a key issue. Observations of the impact of civil unions included the following: “Gays are joining into relationships at younger ages and settling down much sooner in a domestic way, like buying a house, moving out of the downtown village into suburbs” (Copenhagen). “[The young people aren’t coming into the visible community]…so there is a big difference here between the younger and the older men” (Toronto).

In the Eastern Bloc, legal rights were a major issue. “In Poland, we have a big discussion of homophobia so it’s changing. Gay men go into the street and fight for this human right” (Warsaw). “In the Czech Republic, the gay community is more visible than it used to be under Communism.” By contrast, participants in more gay established cities reported decline in gay activism or interest in rights (Johannesburg, Auckland). “We have won our legal battles. Our focus in the UK is to help Eastern Europe with their fights for equality” (London). “In Canada, we have rights so we’re not fighting” (Toronto).

Participants raised other legal issues. “We have a national discussion on discrimination related to controlling diversity. It’s more about race, ethnicity and religion, and the non-matching opinions about sexuality between different cultural heritages” (Amsterdam). Criminalization of HIV-infection was an issue in several city informants brought to the discussion (Amsterdam, Paris, London, Copenhagen). In Copenhagen, participants reported active gay promotion (greater gay friendly policies and increased visibility), in preparation for the 2009 Gay Games. Laws prohibiting gays teaching in schools, and discussion of homosexuality in school curricula appeared active only in Poland (Warsaw). While many informants reported equal treatment under their own country’s laws regarding gay adoption, they also reported movements to fight discriminatory laws in countries of the adoptees (Amsterdam, Malmö).

Changes in HIV prevention

Participants described a decline and change in HIV prevention services targeting gay men. “For 3 years, the focus of HIV prevention in South Africa has not been on gay people. So gay men aren’t getting messages about risk. There’s a lot of unsafe sex” (Johannesburg). “The prevalence is going up but the number of communications from the [AIDS] association has gone down.” “HIV prevention for gay men used to be very peer-based, partly because all the activity was based around the gay community. Now it’s moved towards posters and online resources.” “Outreach is now online, mainly outreach workers in chat rooms trying to engage men in conversation” (London, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Auckland, Malmö, Toronto, Prague, Miami, Minneapolis, New York). “There are also quite a few websites and the emergence of using MySpace and online gay sites for interventions” (London). “We started with peer education online; the second intervention was messages on web pages and sites; the third were references to prevention sites themselves. In the latest interventions we encourage people to take some free-form questions about HIV” (Auckland). “We take people on a virtual gay cruise where you are visiting a boat, have a purser and several guys to have sex with” (Amsterdam).

Impact of gay community change on HIV risk

The changes in the gay community were noted as increasing safer sex decision complexity and HIV risk, while decreasing effective prevention. “The young people are searching for a steady partner; the notion of a committed couple is playing into their decisions” (Paris). “Negotiated safety is strong” (Sydney). “It’s harder to communicate to the community because it is more fragmented so you cannot appear to the gay people as one” (Copenhagen). “There seems to be an increase in sex parties where you don’t practice safe sex” (Toronto and seven cities). There’s a greater division between those who bug the safer sex message, who are self-selecting into one group; and those into bare-backing who divide into another group. Different networks; both are having big parties” (Paris).

Future directions

Societal oppression, lack of rights and the HIV epidemic were noted as powerful reason why gay men came together as a community. With societal acceptance, equal rights and effective HIV treatments, participants questioned whether a gay community would exist, or exist as strongly, in the future. “In Demark, you see some mainstreaming. We talk about the gay community as dying, but I think people still need it” (Copenhagen). “The gay community may disappear” (Amsterdam). “With this whole idea of gay being just one aspect of people, the young people are going to mixed clubs; I don’t see them developing around a gay community” (Miami). “There’s been a drop in energy devoted to any kind of social movement” (Toronto). “In France, there is more commercial focus on the body which has taken the place of other social movements and friendship” (Paris). Paradoxically, conservative opposition may hold some gay communities together. “We’re seeing an emerging backlash against liberalism more broadly, and certainly within the U.K., the conclave of the Bishops of Scotland and England have recently decided that any politician who supports abortion will be excommunicated” (London).

Discussion

The broad objective of this study was formative and exploratory using expert informant structured discussions as a method to identify community level change. Such an approach has at least three limitations. First, while similar observations by key informants in several cities may addresses reliability, the comments are only as valid as each participant’s familiarity with her/his community. Second, this sample represents a self-selected subgroup of attendees at an International conference. Third, a focus group methodology may be vulnerable to “group think” biases, where some participants may not feel comfortable expressing views different from those expressed previously. With these limitations in mind, there are several key conclusions that can be drawn from the results.

First, key informants in all but the largest cities described their gay communities as undergoing significant structural decline. In this “post-gay community” era, large numbers of gay-individuals, gay-couples and gay-families appear well-integrated into mainstream society; use virtual means to meet their same-sex social, sexual, and educational needs; but identify and function more as a sexual minority than as a physical “community.”

The key question is whether such change is temporary, cyclical or permanent. If temporary or cyclical, the results are consistent with community-recovery post-disasters where, at least for a time, large numbers of people seek physical, psychological or social distance from the disaster. Bearing in mind that this community has “fought” HIV for 25 years, that in the U.S. cities, for example, 20–25% of gay men have died from AIDS, and 8–50% of the community are living with HIV (depending on the sub-group studied), such a response is consistent with post-trauma response. If so, the “gay community” may appear to fall apart or “die”, but should regroup given sufficient time. If permanent, the broad nature of these changes on multiple dimensions is consistent with theories of social assimilation (Alba and Nee, 1997).

Second, discrimination in law and society against gay men in most western cities appears to have significantly reduced to a point where there may be less need to organize and identify as a community. At least in the United States, if assimilation occurs, it appears to take 1–2 generations for immigrant communities to be considered equal citizens by their fellow Americans (Weaver, 2006). If June 1969 is considered the birth date of the modern gay movement, then the gay community appears to be following assimilation timelines experienced by other communities.

Third, the changes at the community or cultural level have important implications for HIV prevention. With key informants reporting a collapse in HIV prevention for MSM across most cities, researchers should not assume HIV prevention is available to those most at risk. As segments of the gay community diverge or assimilate, a single set of HIV prevention recommendations for all MSM that differ from those in the general population may be outdated and even counterproductive. For example, recommendations to use a condom every time, or to test for HIV annually, appear medically questionable or irrelevant for men in seroconcordant, monogamous relationships. If younger gay men are searching for a life partner, their sex and safer sex decision-making may be more similar to their heterosexual peers, than MSM’s decision making in casual liaisons; and hence blanket recommendations may not generalize. Key informants noted striking differences between younger and older gay cohorts; future HIV prevention interventions for younger gay men may need to be modeled on current experiences of psychosexual development that may differ from earlier models. As the gay community disperses, HIV prevention and health services based in gay neighborhoods are likely to become increasingly inconvenient and less utilized.

Fourth, policy makers face a tough decision if they are to address the resurgent HIV/STI epidemics among MSM, effectively. Should there be a single, distinct, set of recommendations for MSM, or does policy on HIV prevention for MSM need re-conceptualization? Successful key ingredients in early gay HIV prevention efforts appear to have included a clear single safe sex message, community-led promotion and activism, community-appropriate interventions, and a strong sense of solidarity against a single, deadly disease. HIV prevention for MSM in the post-gay community era may need to emphasize different strategies for different subpopulations, rely less on community-based interventions, and recruit differently. The effectiveness of community-based prevention and treatment interventions will likely decline.

The most immediate challenge is how to build a strong, vibrant, supportive, virtual gay community. This may alleviate some fracturing along different lines identified in several cities. The digital divide needs to be addressed. Internet-based interventions have already been implemented in most cities; the effectiveness of these warrant evaluation. To promote HIV testing in MSM, new strategies should be considered such as over-the-counter testing supplemented by web-based support services.

Finally, several directions for future research are identified. If a comprehensive understanding of the resurgent epidemic is to be achieved, it is clear that more research is needed particularly focused on extra-individual factors and macro-level change. Since two of the most enduring gay institutions, at least over the last 200 years, have been gay bars and sex venues (Duberman, 1986; Karlen, 1971), the change in bars may be the most significant environmental feature community change to monitor. As the application of the ecological model to HIV risk hopefully makes clear, any single or few factor explanations for the resurgent HIV epidemic among gay men are likely to be overly simplistic, and unlikely to result in effective recommendations. Rather, a multi-factorial and multi-layered approach to studying this challenge is needed for effective HIV prevention in the post-gay community era to be identified.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the key informants, many of them senior colleagues and long-standing HIV prevention specialists, for their valuable contributions. This study was undertaken as part of formative research on the “Structural Interventions to Lower Alcohol-related STI/HIV,” grant number R01AA01627001, funded by the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

References

- Alba R, Nee V. Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration. International Migration Review. 1997;31(4):826–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer R. Private Acts, Social Consequences: AIDS and the Politics of Public Health. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship KM, Bray SJ, Merson MH. Structural interventions in public health. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl 1):S11–S21. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castells M. The City and the Grassroots: A Cross-Cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Taking action to combat increases in STDs and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. Alert from Ronald O Valdiserri, MD, MPH, Deputy Director. National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2001a. Apr 30, [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No Turning Back. CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: A meta-analytic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:224–236. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit JBF, De Vroome EM, Sanfort T, Van Griensven GJ. Homosexual encounters in different venues. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1997;8:130–134. doi: 10.1258/0956462971919552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duberman MB. About Time: Exploring the Gay Past. New York, NY: Seahorse Pubs; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gross M. The second wave will drown us. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(6):872–881. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RB, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Unprotected sex and HIV risk taking among young gay men within boyfriend relationships. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1997;9(4):314–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlen A. Sexuality and homosexuality: A New View. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Liau A, Millett G, Marks G. Meta-analystic examination of online sex-seeking and sexual risk among men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33:576–584. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204710.35332.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bobeau D, Stckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin SF, Vernon K, Harcourt J, et al. Why HIV infections have increased among men who have sex with men and what to do about it: Findings from California focus groups. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7:353–362. doi: 10.1023/b:aibe.0000004727.23306.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Dean L. Effect of sexual behavior change on long-term human immunodeficiency virus prevalence among homosexual men. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1994;140:217–232. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RG, Easton D, Klein CH. Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: a review of international research. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl 1):S22–S32. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relf MV, Huang B, Campbell J, Catania J. Gay identity, interpersonal violence, and HIV risk behaviors: an empirical test of theoretical relationships among a probability-based sample of urban men who have sex with men. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2004;15(2):14–26. doi: 10.1177/1055329003261965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M, Rosser BRS, Bauer G, Bockting W, Robinson B, Rugg D, Coleman E. Drug Use, Unsafe Sexual Behavior, and Internalized Homonegativity in Men Who Have Sex With Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;(5):97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS, Horvath KJ. Predictors of success in HIV prevention in rural America: A state level structural factor analysis of HIV prevention targeting Men who have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9230-y. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS, Ross MW, Bockting WO. The relationship between homosexuality, internalized homonegativity and mental health in Men who have Sex with Men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2007 doi: 10.1080/00918360802129394. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumartojo E, Doll L, Holtgrave D, Gayle H, Merson M. Enriching the mix: incorporating structural factors into HIV prevention. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumartojo E. Structural factors in HIV prevention: concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl 1):S3–S10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS Policy Brief: HIV and Sex Between Men. 2006 Retrieved at: http://data.unaids.org/pub/BriefingNote/2006/20060801_Policy_Brief_MSM_en.pdf.

- Valdiserri RO. Mapping the roots of HIV/AIDS complacency: implications for program and policy development. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;26:426–439. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.5.426.48738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver G. USINFO webchat transcript. Elements of American identity. 2006 http://usinfo.state.gov/usinfo/Archive/2006/Jul/26-923232.html.

- Wohlfeiler D. Structural and environmental HIV prevention for gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl 1):S52–S57. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods W, Binson D, editors. Gay Bathhouses and Public Health Policy. Binghamton: Harrington Park Press; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]