Summary

Conjugal DNA transfer in Mycobacterium smegmatis occurs by a mechanism distinct from plasmid-mediated DNA transfer. Previously, we had shown that the secretory apparatus, ESX-1, negatively regulated DNA transfer from the donor strain; ESX-1 donor mutants are hyper-conjugative. Here, we describe a genome-wide transposon mutagenesis screen to isolate recipient mutants. Surprisingly, we find that a majority of insertions map within the esx-1 locus, which encodes the secretory apparatus. Thus, in contrast to its role in donor function, ESX-1 is essential for recipient function; recipient ESX-1 mutants are hypo-conjugative. In addition to esx-1 genes, our screen identifies novel non-esx-1 loci in the M. smegmatis genome that are required for both DNA transfer and ESX-1 activity. DNA transfer therefore provides a simple molecular genetic assay to characterize ESX-1, which, in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is necessary for full virulence. These findings reinforce the functional intertwining of DNA transfer and ESX-1 secretion, first described in the M. smegmatis donor. Moreover, our observation that ESX-1 has such diametrically opposed effects on transfer in the donor and recipient, forces us to consider how proteins secreted by the ESX-1 apparatus can function so as to modulate two seemingly disparate processes, M. smegmatis DNA transfer and M. tuberculosis virulence.

Keywords: Secretion, Conjugal DNA transfer, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, ESX-1 secretory apparatus

Introduction

The esx-1 locus is a highly conserved locus found throughout the Mycobacteria (Gey Van Pittius et al., 2001; Pallen, 2002), and has been the subject of intense research because of its association with virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (reviewed in (Abdallah et al., 2007; DiGiuseppe Champion and Cox, 2007). Comparative analyses between the vaccine strain Mycobacterium bovis BCG and its parent, virulent M. bovis identified a 9.5 kb deletion (previously called region of difference 1, or RD1; (Behr et al., 1999; Mahairas et al., 1996) within the esx-1 locus as the primary attenuating mutation of BCG. Deletion of the equivalent regions in M. tuberculosis and in M. bovis also resulted in their attenuation and confirmed the importance of esx-1 in virulence (Hsu et al., 2003; Lewis et al., 2003; Stanley et al., 2003). Genetic, bioinformatic, and immunological evidence has since shown that esx-1 encodes a secretory apparatus, ESX-1, responsible for the secretion of at least two esx-1 encoded proteins, EsxA and EsxB (formerly Esat-6 and Cfp-10 respectively), which form a heterodimer EsxAB (Gey Van Pittius et al., 2001; Guinn et al., 2004; Hsu et al., 2003; Pallen, 2002; Pym et al., 2002; Renshaw et al., 2002; Stanley et al., 2003). The discovery of a specialized secretory apparatus explained why EsxA and EsxB are found in culture filtrates, despite their lacking classical secretion signal sequences (Sorensen et al., 1995). Mutations in most esx-1-associated genes prevent secretion (Fig. 1; and reviewed in Abdallah et al., 2007; Brodin et al., 2004; DiGiuseppe Champion and Cox, 2007; Gey Van Pittius et al., 2001).

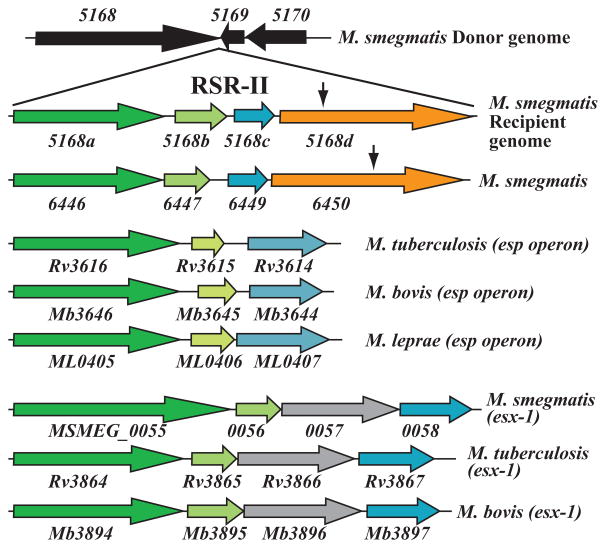

Fig. 1.

A genetic map comparing the esx-1 loci of M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis. The two maps are aligned, with colour-coding used to indicate homologous gene pairs in the two species. The M. tuberculosis esp operon is shown above the M. tuberculosis esx-1 locus, and is aligned with gene homologues found in the first segment of esx-1. The map of the M. smegmatis recipient esx-1 locus is based on the donor DNA sequence (TIGR), but it is modified based on our sequencing analyses. Note that donor genes Msmeg_0072-0075 are deleted. The 3′-end of the M. smegmatis locus is predicted to encode additional genes (Msmeg_0077-0080) that are not present in M. tuberculosis; these genes are related to M. smegmatis genes Msmeg_0055-0058 as indicated by their colours. Above the M. smegmatis map, the +/- symbols indicate the sites of transfer-defective insertions. A ‘+’ indicates that the insertion disrupts EsxB secretion and, therefore, the gene is required for both transfer and ESX-1 activities. A ‘-’ indicates the insertion has no effect on EsxB secretion, but does disrupt DNA transfer.

The ESX-1 apparatus is composed of a core of proteins that are mainly encoded from the 5′-half of the esx-1 locus; in M. tuberculosis they include genes Rv3868-3877, and in M.smegmatis genes Msmeg_0059-0068. The requirement for each of the other genes within this 20-gene locus has yet to be determined experimentally. The Rv3877 protein is predicted to fold with membrane-spanning domains and is therefore hypothesized to form the pore. Two genes (Rv3870 and Rv3871) are predicted to encode ATPases that are thought to deliver EsxAB to Rv3877. Protein-protein interaction studies indicate that Rv3870 and 3871 interact (Converse and Cox, 2005; Teutschbein et al., 2007). In addition, Rv3871 is known to interact with the C-terminal tail of EsxB; accordingly, Rv3871 likely recognizes the EsxAB heterodimer and delivers it to the pore for secretion (Champion et al., 2006).

More recent work has demonstrated that the ESX-1 apparatus, in addition to EsxA and EsxB, secretes other proteins. Studies in M. marinum have established that a third esx-1-encoded protein, Mh3881 (equivalent to the M. tuberculosis Rv3881 protein, Fig. 1) is secreted. Because Mh3881/Rv3881 secretion is dependent on the M. tuberculosis Rv3879 protein, but not Rv3866 and Rv3867, it's secretion is likely mediated by a novel set of esx-1 encoded proteins (McLaughlin et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2007). A second M. tuberculosis locus, esp, distinct from esx-1 is essential for EsxAB secretion (Fortune et al., 2005; MacGurn et al., 2005). The first gene of this operon Rv3616 (espA) encodes a protein that lacks a signal sequence, and is also secreted. Most significantly, EspA secretion is dependent on the co-secretion of EsxAB, and vice-versa (Fortune et al., 2005). The interdependence of EspA and EsxAB secretion led to the proposal that these three proteins form a complex, which is secreted by the ESX-1 apparatus, although direct evidence to support this interaction has not been described. The esp operon encodes paralogues of three of the first four genes of the esx-1 operon (Fig. 1), suggesting that esp arose by gene duplication and has evolved so as to facilitate ESX-1 mediated secretion. The absence of esp from the non-pathogenic species, M. smegmatis and Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis has led to the suggestion that esp is a virulence-specific locus (MacGurn et al., 2005).

Analysis of esx-1 mutants has revealed that ESX-1 activity is associated with multiple phenotypes, including growth in macrophages, host-cell lysis and spread of mycobacteria to macrophages, and cytosolic entry and replication, but the mechanism of secretion and substrates exported by ESX-1 are still not defined (Abdallah et al., 2007; Brodin et al., 2004; DiGiuseppe Champion and Cox, 2007). Moreover, any model that is proposed must be able to explain the functional conservation of ESX-1 in both pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria (as will be described below).

Previously, we described a novel DNA transfer process in M. smegmatis, a process most closely resembling conjugation. DNA transfer is DNAse resistant; genetic exchange is unidirectional; there are distinct donor and recipient strains; extensive regions of the chromosome are transferred; and recombinants are only detected after prolonged co-incubation of donor and recipient cells on solid medium (Parsons et al., 1998). However, there are clear genetic and mechanistic differences from the prototypical transfer systems encoded by bacterial plasmids (Wang and Derbyshire, 2004). We have shown that the M. smegmatis donor chromosome contains multiple cis-acting sites from which transfer can be initiated. This contrasts with the single cis-acting site, oriT, from which plasmid transfer is initiated (Wang et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2005). Analysis of chromosomal DNA of mycobacterial transconjugants shows that they can acquire different segments of the donor chromosome (i.e., non-contiguous segments of DNA can be transferred), and transconjugants can be readily converted to donors following chromosomal transfer, unlike Hfr transfer in E. coli.

The unique nature of the mycobacterial transfer process, and the potential applications to the study of pathogenic Mycobacteria, especially M. tuberculosis has encouraged us to investigate the mechanism of transfer and determine its prevalence among the pathogenic mycobacterial species. Previously, a transposon mutagenesis approach was utilized to isolate insertion mutants affecting transfer from the donor (Flint et al., 2004). Remarkably, that study identified the large secretory apparatus, ESX-1, as a regulator of DNA transfer: insertions mapped to the 30 kb esx-1 locus of M. smegmatis and resulted in a hyper-conjugative phenotype. Transfer from esx-1 mutants was increased between 20- and 7,000-fold (Flint et al., 2004), indicating that esx-1 negatively regulates DNA transfer. Moreover, by complementing the M. smegmatis esx-1 mutants with the esx-1 region of M. tuberculosis we demonstrated that this locus is both genetically and functionally conserved.

Based on the above results, we proposed that proteins secreted by ESX-1 inhibited DNA transfer. Consequently, insertions that disrupted the locus will not secrete inhibitors and result in elevated levels of DNA transfer (Flint et al., 2004). Transfer inhibition could have occurred either via the formation of a physical barrier preventing cell-cell contact and DNA transfer, or via the secreted proteins mediating donor-recipient communication and inhibiting transfer until appropriate conditions were satisfied - a form of quorum sensing.

The donor and recipient strains are independent isolates of M. smegmatis with distinct colony morphologies (Mizuguchi et al., 1976). The genetic basis for donor and recipient ability is unknown and, therefore, we have completed a transposon mutagenesis screen of the recipient strain. The results indicate that ESX-1 has a central role in conjugation. Many of the transfer-defective mutations map to genes either within, or associated with, the recipient esx-1 locus. This underscores the functional connection between DNA transfer and ESX-1 activity, and importantly serves to identify the first “essential” phenotype for ESX-1. The requirement for ESX-1 activity in the recipient, contrasts with the regulatory role that ESX-1 plays in the donor, and forces us to re-assess the roles of ESX-1 and to provide a new model for how ESX-1 modulates M. smegmatis DNA transfer.

Results

Mutations in the esx-1 region of the recipient disrupt DNA transfer

A screen of a transposon insertion library of M. smegmatis MKD8 recipients was carried out to identify genes that have roles in conjugation. Following a screen of 5,286 insertions, 49 transfer-defective mutants were isolated. The precise site of each insertion was determined by DNA sequence analysis (see Exptl. Proced.), and the results are summarized in Table 1. Among the 49 mutants, 31 were found to reduce the conjugation frequency >1000-fold compared with the wild-type, as measured in a quantitative mating assay.

Table 1.

Summary of recipient-defective mutants.

| M. smegmatis genomic location | M. smegmatis gene (Msmeg_) | Previous gene number | Fold-decrease in conjugation frequency | Gene function | Location of insertion | EsxAB secretion detected6? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| esx-1 proximal | _0044 | 0044 | 166 | Hypothetical (Hyp). (61,470 - 63,548) | 62,194 | N |

| esx-1 proximal | _0044 | 0044 | >100 | Hyp. (61,470 - 63,548) | 62,602 | N |

| esx-1 proximal | _0044 | 0044 | 743 | Hyp. (61,470 - 63,548) | 62602 | N |

| esx-1 proximal | _0045 | 0045 | 33 | Hyp. (63,545 - 66,013) | 63,573 | Reduced |

| esx-1 proximal | _0045 | 0045 | 186 | Hyp. (63,545 - 66,013) | 63,756 | Reduced |

| esx-1 | _0056 | 0056 | >1000 | Hyp. (76,213 - 76,530) | 76,528 | N |

| esx-1 | _0057 | 0056 | >1000 | Conserved Hypothetical (Cons. Hyp.) (76,535 - 77,383) | 77,102 | N |

| esx-1 | _0059 | 0058 | >1000 | Putative (put.) ATPase, AAA family (77,918 - 79,642) | 79,040 | N |

| esx-1 | _0059 | 0058 | >1000 | put. ATPase, AAA family (77,918 - 79,642) | 78,333 | N |

| esx-1 | _0060 | 0059 | >1000 | Cons. Hyp. (79,650 -81,089) | 80,880 | N |

| esx-1 | _0060 | 0059 | >21,800 | Cons. Hyp. (79,650 -81,089) | 80,880 | ND |

| esx-1 | _00622 | 0061 | 711 | FtsK/SpoIIIE family subfamily (83,318 - 85,099) | 83,690 | N |

| esx-1 | _0062 | 0061 | >1000 | FtsK/SpoIIIE family subfamily (83,318 - 85,099) | 84,408 | N |

| esx-1 | _0062 | 0061 | 71 | FtsK/SpoIIIE family subfamily (83,318 - 85,099) | 85,097 | Y3 |

| esx-1 | _0063 | 0062 | >40,000 | PE family protein (85,248 - 85,541) | 85,503 | N |

| RSR-I/esx-1 | _0070R4 | 00702 | >1000 | RSR-I homologue of 0070 (1131 bp) | 680 / 1131 | Y |

| RSR-I/ esx-1 | _0071R4 | 00692 | >1000 | RSR-I homologue of 0071 (2226 bp) | 443 / 2266 | Y |

| RSR-I/esx-1 | _0071R4 | 00692 | 1352 | RSR-I homologue of 0071 (2226 bp) | 655 / 2226 | Y |

| RSR-I/esx-1 | _0071R4 | 00692 | 7930 | RSR-I homologue of 0071 (2226 bp) | 1299 /2226 | Y |

| RSR-I/esx-1 | _0071R4 | 00692 | 505 | RSR-I homologue of 0071 (2226 bp) | 1672 / 2226 | Y |

| RSR-I/esx-1 | _0071R4 | 00692 | >1000 | RSR-I homologue of 0071 (2226 bp) | 1672 / 2226 | Y |

| esx-1 | _00762 | 00742 | >1000 | Antigen MTB48 (99,798 - 101,360) | 101, 280 | Y |

| esx-1 | _00762 | 00742 | >1000 | Antigen MTB48 (99,798 - 101,360) | 101,282 | Y |

| esx-1 | _0083 | 0081 | >40,000 | membrane-anchored mycosin mycpl (107,334 - 105,985) | 106,666 | N |

| _02542 | _02452 | >1000 | Cons. Hyp. (286,183 - 287,649) | 286,207 | Y | |

| _1686 | 1682 | >1000 | NLP/P60-family secreted protein (1,780,178 - 1,779,111) | 1,779,403 | Y | |

| 1954-1959 | _1955 | 1959 | >1000 | Cons. Hyp. (2,034,406 - 2,033,567) | 2,033,786 | Y |

| 1954-1959 | _1959 | 1961 | 160 | Put. Membrane protein (2,037,115 - 2,040,126) | 2,037,514 | Y |

| 1954-1959 | _1959 | 1961 | >1000 | Put. Membrane protein (2,037,115 - 2,040,126) | 2,038,704 | Y |

| 2404 | _2404 | 2402 | >1000 | Extracellular deoxyribonuclease (2,486,903 - 2,487,607) | 2,486,964 | Y |

| 2404 | _2404 | 2402 | 7040 | Extracellular deoxyribonuclease (2,486,903 - 2,487,607) | 2,486,964 | Y |

| _2518 | 2521 | ND | Peptidase M23B (2,604,666 - 2,604,148) | 2,604,471 | Y | |

| _3078 | 3087 | 292 | Excinuclease ABC, C subunit (uvrC) (3,150,228 - 3,152,348) | 3,150,474 | Y | |

| _3654 | 3660 | >1000 | ATPase SecA2 (3,719,510 - 3,717,156) | 3,718,964 | Y | |

| _3751 | 3758 | 50 | hemolysin A (toxin prodxn and res'tance); (3,817,587 - 3,816,778) | 3,817,482 | Y | |

| paf operon | _3888 | 3891 | 402 | Cons. Hyp. (3,961,469 - 3,690,513) | 3,960,649 | Y7 |

| paf operon | _3888 | 3891 | >1000 | Cons. Hyp. (3,961,469 - 3,690,513) | 3,960,711 | Y7 |

| paf operon | _3889 | 3893 | 3511 | Cons. Hyp. (3,962,462 - 3,961,466) | 3,962,399 | ND |

| paf operon | _3889 | 3893 | ND | Cons. Hyp. (3,962,462 - 3,961,466) | 3,962,399 | Y |

| paf operon | _3889 | 3893 | >1000 | Cons. Hyp. (3,962,462 - 3,961,466) | 3,961,932 | Y7 |

| _5447 | 5427 | 150 | Dolichyl-phosphate-mannose-protein mannosyltransferase (5,531,610 - 5,533,160) | 5,532,876 | N | |

| _6136 | 6099 | 6 | Membrane Protein, TerC family (6,199,776- 6,198,808) | 6,199,768 | Y | |

| tad locus | _6169 | 6131 | >1000 | tadA, Type II/IV Secretion System Prot. (6,239,853 - 6,238,696) | 6,239,203 | Y |

| _61891 | 61481 | 5 | Transcriptional Regulator, Crp/Fnr fam. (6,256,824 - 6,257,498) | 6,256,806 | Y | |

| _6329 | 6290 | 27 | Cons. Hyp. (6,396,618 - 6,396,103) | 6,396,260 | Y | |

| RSR-II paralogue | _64502 | 6412 | >1000 | Hyp. (6,512,987 - 6,514,384) | 6,513,915 | Y |

| _6925 | 6881 | 40960 | Cons. Hyp. (6,966,936 - 6,966,439) | 6,966,725 | Y | |

| _6940 | 6895 | >1000 | Methyltransferase GidB (6,983,428 - 6,982,721) | 6,983,349 | Y | |

| RSR-II5 | 5168d | ORF4 | 5771 | Hyp. (1443 bp) | 625 / 1443 | Y |

Abbreviations; Hyp, Hypothetical; Cons.Hyp., conserved hypothetical; Put., putative

insertion upstream of gene.

not perfect alignment with donor sequence.

insertion in stop codon, thus gene is not disrupted.

R indicates that the gene is recipient-specific and differs significantly from the donor homologue.

RSR-II is a four gene (5168a-d) insertion between donor genes 5168 and 5169

N, indicates EsxB not detected; Y, yes secreted; ND, not done.

EsxAB were secreted, but levels of the cytoplasmic protein GroEL were high in the culture filtrate indicating significant cell leakage caused by paf mutants (Fig S1).

Nineteen of the 49 mutations mapped to the esx-1 region of M. smegmatis in ten different esx-1 genes (Fig. 1, Table 1, and below). This was an unexpected finding as ESX-1 donor mutants are hyper-conjugative (Flint et al., 2004). Thus, the ESX-1 secretion system performs two distinct roles in DNA transfer: in the donor ESX-1 suppresses conjugation, while in the recipient it is essential for conjugation. This is the first “essential process” observed for ESX-1, and the fact that ESX-1 has functions in both donor and recipient provides further insight into its role in both DNA transfer and TB virulence (see discussion). Although many of the recipient insertions mapped to genes already known to play regulatory roles in the donor, three of the insertions identified new genes associated with conjugation (Msmeg_0056, 0057, and 0083). Of these three genes, two had been previously defined as being part of the esx-1 locus, based on secretion studies in M. marinum and M. smegmatis (Converse and Cox, 2005; Gao et al., 2004). A transfer-defective insertion was mapped in Msmeg_0056, which is the first mutation mapped to this gene and thus extends the 5′-end of the esx-1 locus needed for DNA transfer.

Insertions in genes upstream of the esx-1 region result in decreases in transfer frequency

Five insertions located approximately 7.4kb upstream of esx-1 were identified as down-mutants in the recipient screen (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). Three of these insertions were independently isolated in the hypothetical gene Msmeg_0044 (all three decreased transfer >100-fold), and two insertions were isolated in Msmeg_0045 (33-fold and 186-fold decreases). These two genes together with Msmeg_0046 form a three-gene operon. The genes have no predicted function, and no homologues in mycobacteria (Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Clustered insertions identify loci required for DNA transfer. Genes with defined function are named and shaded in light grey, while genes that have a putative function or that are classified as hypothetical orfs are shaded in dark grey.

A. Multiple insertions (indicated by vertical arrows) mapped in Msmeg_0044-0045 disrupted both DNA transfer and EsxB secretion. These two genes are part of a three-gene operon found upstream of the esx-1 locus. The esx-1 locus begins at Msmeg_0055 (in charcoal).

B. Three transfer-defective insertions map to two operons transcribed from overlapping promoter regions. One insertion was mapped in Msmeg_1955 (conserved hypothetical) and two insertions were located in Msmeg_1959 (encoding a putative membrane protein). Msmeg_1954 encodes a putative ABC1 transporter, ATP-binding protein. Msmeg_1958 encodes a PDZ domain family protein.

C. Insertions in Msmeg_3888 and 3889 disrupt recipient function. These two genes are both predicted to encode DNA binding proteins.

To examine whether the 0044-0045 gene-products are also required for transfer from the donor, each recipient mutation was transduced into the donor strain mc2155. Each mutant donor derivative was transfer-proficient, establishing that these genes are only essential for recipient activity (data not shown). Furthermore, in preliminary quantitative matings, we found that transfer from these donor derivatives occurs at wild-type levels, rather than at the elevated levels observed for esx-1 donor mutants; thus, the function of 0044 and 0045 in DNA transfer appears to be recipient-specific (E. DeConno and KMD, unpub data).

Multiple insertions within a region define three additional recipient loci required for DNA transfer

Of the 24 insertions found outside of the esx-1 locus, 10 mapped to three regions that contain multiple insertions within an operon, suggesting that these operons define transfer-associated loci (Table 1, Fig. 2).

One region is defined by three independent insertions found within 4 kb of each other (Msmeg_1954-1959; Fig. 2B). One insertion mutation was located in Msmeg_1955 (encoding a conserved hypothetical protein), and two insertions were located in Msmeg_1959 (encoding a putative membrane protein). These two genes are in two operons transcribed in opposite orientations, but from a common intergenic region of 108bp that presumably contains divergent promoters. Msmeg_1955 is the second gene in a three-gene operon, along with a downstream gene (Msmeg_1954) encoding a putative ABC1 transporter, ATP-binding protein and an upstream conserved hypothetical gene (Msmeg_1957). Msmeg_1959 is the second gene in a two-gene operon. The upstream gene, Msmeg_1958, encodes a protein containing a PDZ-domain known to facilitate protein-protein interactions (Fanning and Anderson, 1999). These two operons are conserved, and have the same syntenic organization in other mycobacteria (Table S1).

Two independent insertions mapped to the same site within the conserved gene, Msmeg_2404, which encodes a putative extracellular deoxyribonuclease. This is the last gene in a three-gene operon, encoding a putative dihydroxyacetone kinase protein (Msmeg_2402) and an ATP-dependent DNA helicase, recG (Msmeg_2403) (Tables 1 and S1). These insertions are the only mutations found in the screen that are clearly associated with DNA metabolism, although it is known that RecA and other recombination functions are required for successful transfer (Wang et al., 2003).

Five insertions mapped to the paf operon (for proteosome accessory factor): two in a predicted transcription regulator, Msmeg_3888, and three in a gene encoding a putative repressor protein, Msmeg_3889 (Table 1 and Fig. 2C). These genes are the second and third genes of a seven-gene operon that includes a putative proteasome gene (pafA, Msmeg_3890), twin argentine-targeting translocase (TAT) genes, tatA (Msmeg_3887) and tatC (Msmeg_3886), a putative DEAD/DEAH box helicase gene (Msmeg_3885), and a conserved hypothetical gene (Msmeg_3884). This operon is conserved in M. tuberculosis, in which the first three genes form an operon called paf (Darwin et al., 2003; Table S1). M. tuberculosis pafA is a putative component of the proteosome, as mutations of pafA conferred sensitivity to reactive nitrogen intermediates (Darwin et al., 2003). The precise roles of the two downstream genes, pafB and pafC (homologues of Msmeg_3888 and 3889, respectively), in M. tuberculosis are unclear, given that pafB and pafC mutants do not affect degradation of known proteosome substrates (Festa et al., 2007). The PafB and PafC proteins interact, which is consistent with our observation that conjugation-deficient insertions were mapped to both genes, and that both are predicted to be DNA-binding proteins: each protein is predicted to encode an N-terminal DNA-binding motif with structural similarities to BirA (Weaver et al., 2001).

To address whether Msmeg_3888/9 are required in the donor and the recipient, a deletion of each gene was created in mc2155 (the donor strain) by allele exchange. Transfer from this mutant derivative was unaffected (data not shown), establishing that genes 3888 and 3889 encode recipient-specific functions. The same deletion in the recipient abolished transfer, establishing that transfer requires the 3888/3889 gene products, and not proteins encoded from the genes downstream.

An insertion in the tadA locus of M. smegmatis disrupts transfer

An insertion in Msmeg_6169 abolished recipient function. Bioinformatic studies indicate that 6169 encodes a homologue of the TadA protein, a membrane-associated ATPase involved in macromolecular transport. tadA is part of a larger conserved locus, tad, which was originally identified in Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans as a locus necessary for biofilm formation and tight adherence (tad; Kachlany et al., 2000). The locus encodes components of a subtype type II secretion pathway and is present in many bacterial genomes (Kachlany et al., 2001; Planet et al., 2003; Tomich et al., 2007). Most notably for this work, TadA is a homologue of VirB11, an essential component of plasmid-mediated conjugation (Cascales and Christie, 2003; Yeo and Waksman, 2004).

Given the potential roles of TadA in other bacterial species, we addressed whether TadA was required in the donor strain for transfer. A precise deletion of tadA was created by recombineering, and this mutant strain assayed for DNA transfer. The tadA deletion caused a hyper-conjugative phenotype, with transfer frequencies elevated 50-fold compared with the wild-type donor and, thus, rules out a role in DNA export, as envisioned for VirB11. However, the influence of tadA on DNA transfer is remarkably similar to that of ESX-1; donor mutants are hyperconjugative, but recipient mutants are defective in DNA transfer.

Sequences unique to the M. smegmatis recipient are necessary for recipient function and provide another link to ESX-1

The DNA sequences surrounding four insertion mutations do not align to the known donor M. smegmatis sequence from TIGR and, thus, represent recipient-specific DNA regions (RSRs). A combination of PCR and analysis of DNA sequence surrounding three of the insertion mutations showed that the insertions mapped within the same recipient-specific region, which we termed RSR-I (Fig. 3). The fourth insertion was in a second region (RSR-II; Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

A recipient-specific region is located within esx-1 and encodes genes required for DNA transfer, but not for EsxB secretion. The esx-1 loci from donor and recipient are aligned to highlight the significant differences between them. Note that not only are genes Msmeg_0072-0075 deleted in the recipient, but genes Msmeg_0069R-0071R are only weakly related to their donor homologues. This heterogeneity ends within 0071R; over the last 812 bp of the gene, 0071R has 88% nucleotide identity with the donor copy. The junction between esx-1 and the 5′ end of RSR-I has not yet been mapped. Current sequencing information indicates that two insertion sequences (indicated by yellow boxes) flank 0069R (Coros et al., 2008).

Fig. 4.

Recipient-specific locus II and a second operon, Msmeg_6446-6450, encode homologues of genes found in the esp locus of M. tuberculosis. RSR-II is inserted between genes Msmeg_5168 and 5169, with respect to the mc2155 donor genome sequence. An insertion (vertical arrow) in Msmeg_5168d abolishes DNA transfer. 5168d is significantly similar to Msmeg_6450 (36% aa identity, 53% aa similarity; Table 3); 6450 is also required for DNA transfer (vertical arrow indicates the site of transposon insertion). Importantly, 5168a-d and 6446-6450 form two syntenous operons that are similar to the M. tuberculosis esp operon (middle panel) and the first segment of the highly conserved esx-1 operon (bottom three alignments).

RSR-I encodes genes related to esx-1 genes Msmeg_0069-0071

The RSR-I region, in which three independent insertion mutations were identified, spans at least 4.7 kb (Fig. 3). The 5′ end of RSR-I is defined by two insertion sequences, an IS6110 element and an IS3-like element. The multiple copies of the IS3 element throughout the recipient chromosome have prevented us from chromosome walking through this region to find the 5′-junction with donor sequences. The presence of an IS6110 element is particularly striking because IS6110 elements were thought to be unique to the M. tuberculosis complex (MTBC). The implication is that the RSR-I sequence originated from a member of the MTBC, and was acquired by M. smegmatis in a horizontal transfer event (Coros et al., 2008).

The 3′-end of RSR-I is in Msmeg_0071, within esx-1. Sequence and BLASTP analyses of RSR-I identified three putative genes, which share homology with other mycobacterial genes, including some within esx-1 (Table 2). These three open reading frames (orfs) encode proteins with weak homologies to Msmeg_0069, 0070 and 0071 (Fig. 3). The homologies, together with the conservation of the gene order, suggested that RSR-I is actually part of the 3′-half of esx-1, despite the lack of extensive nucleotide homology. PCR primers were designed to amplify segments of DNA that would span the junction between RSR-I and known segments of the recipient esx-1 locus. The PCR analyses, combined with DNA sequencing, confirmed that the 3′-end of RSR-I is in Msmeg_0071. Downstream of gene 0071R (R for recipient), we also determined that the four donor genes encoding IS transposases (Msmeg_0072-0074) and Msmeg_0075 are absent from the recipient; instead, 0071R is followed immediately by Msmeg_0076 (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

RSR-I gene homologues. For each homologue, the gene function, aa length, % aa Identity, and % conserved aa substitutions are indicated.

| Gene

(length) |

RSR-I gene homologues | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M. smegmatis (Msmeg) donor strain | M. tuberculosis | M. bovis | |

|

_0069R

(190 aa) |

_5988 (Hyp, 267 aa; 35% ID 50% Pos.);

_0069 (233 aa; 31% ID, 39% Pos.); _5101 (Hyp. 276 aa; 30% ID, 41% Pos.); |

||

|

_0070R

(377 aa) |

_2820 (Hyp., 389 aa; 47% ID, 60% Pos.);

_4599 (Hyp., 316 aa; 37% ID, 54% Pos.); _0070 (Hyp., 111 aa; 33% ID, 52% Pos.); |

||

|

_0071R

(742 aa) |

_0071 (Cons. Hyp., 738 aa; N-term 22%

ID, 35% Pos.; C-term 85% ID, 89% Pos.); _0805 (Cons. Hyp., 496 aa; N-term 31% ID 49% Pos.; C-term 50% ID, 60% Pos.); _0075 (Cons. Hyp., 118 aa; 73% ID, 79% Pos.); _5989 (Hyp., 368 aa; N-term 36% ID, 56% Pos.) |

Rv3879c (Hyp., 729 aa; N-term 21% ID,

33% Pos.; C-term 46% ID, 58% Pos.) |

3909c (Hyp., 744 aa; N-term 23%

ID, 38% Pos.; C-term 46% ID, 58% Pos.); |

There is considerable heterogeneity between 0069R-0071R and the donor genes 0069-0071; such heterogeneity is unusual, we generally observe >99% nucleotide identity between the donor and recipient DNA sequences. The heterogeneity ends within 0071R, for which the 5′-end differs significantly from the donor copy (20% identity over the first 472 aa), while the 3′-end of gene 0071R is almost identical to the donor copy (92% aa identity, across the C-terminal 266aa). Three insertions were originally mapped within RSR-I, one within 0070R and two within the 5′-end of 0071R (Table 1). A further three insertions were mapped to the 3′-end of 0071R that has greater (but not perfect) sequence homology with the donor copy, which allowed a more straightforward gene assignment.

RSR-II is a genetic island encoding homologues of genes in the M. tuberculosis esp operon

Chromosome walking established that RSR-II is an insertion of 4.428 kb between donor genes Msmeg_5168 and Msmeg_5169 in the recipient (Fig. 4). The region contains four putative genes (Msmeg_5168a-d). The insertion mutation that led to the discovery of RSR-II was found in 5168d. Notably, 5168d is homologous to Msmeg_6450 in which a recipient-defective insertion was also mapped (Table 1). Thus, despite their similarity, the 5168d and 6450 gene-products perform non-overlapping roles in DNA transfer. Moreover, sequence analysis of the 3 genes upstream of Msmeg_6450 reveals that those genes also form a locus syntenous with RSR-II (Fig. 4, Table 3).

Table 3.

RSR-II gene homologues in mycobacteria. Each homologue is listed in bold with putative gene function; length in amino acids (aa); % aa identity; % conservative aa substitutions.

| Gene

(length) |

Gene homologues for each mycobacterial species | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. smegmatis Donor | M. tuberculosis | M. bovis | M. leprae | |

| _5168a (354 aa) | _6446 (Hyp. 353 aa; 32% ID, 45% Pos.); _0055 (Hyp. 525 aa; 26% ID, 38% Pos.); _5710 (Hyp. 174 aa; 24% ID, 40% Pos.); _0723 (Cons. Hyp. 180 aa; 24% ID, 39% Pos.); | Rv3616c (Hyp. 392 aa; N-term 100 aa are 27% ID, 44% Pos.); Rv3864 (Hyp. 402 aa; N-term 100 aa are 22% ID, 42% Pos.) | Mb3646c (Cons. Hyp. 392 aa; N-term 100 aa is 27% ID, 44% Pos.); Mb3894 (Cons. Hyp. 418 aa; N-term 100 aa are 22% ID, 42% Pos.) | ML0405 (Cons. Hyp. 394 aa; N-term 100 aa is 27% ID, 42% Pos.) |

| _5168b (119 aa) | _6447 (Hyp. 107 aa; 42% ID, 57% Pos.); _0056 (Hyp. 105 aa; 35% ID, 56% Pos.); _0077 (Hyp. 105 aa; 35% ID, 51% Pos.); _0728 (Hyp. 108 aa; 30% ID, 51% Pos.) | Rv3615c (Hyp. 103 aa; 26% ID, 40% Pos.); Rv3865 (Hyp. 103 aa; 26% ID, 37% Pos.) | Mb3645c (Cons. Hyp. 103 aa; 26% ID, 40% Pos.); Mb3895 (Cons. Hyp. 103 aa; 26% ID 37% Pos.) | ML0406 (Cons. Hyp. 106 aa; 26% ID, 43% Pos.) |

| _5168c (97 aa) | _6449 (Cons. Hyp. 106 aa; 49% ID, 68% Pos.); _0058 (Cons. Hyp. 175 aa; 35% ID, 53% Pos.); _0080 (Cons. Hyp. 188 aa; 33% ID, 59% Pos.); _5709 (Cons. Hyp. 177 aa; 30% ID, 41% Pos.); _0722 (Cons. Hyp. 167 aa; 26% ID, 48% Pos.) | Rv3614c (Hyp. 184 aa; 35% ID, 50% Pos.); Rv3867 (Hyp. 183 aa; 31% ID, 47% Pos.) | Mb3644c (Cons. Hyp. 184 aa; 35% ID, 50% Pos.); Mb3897 (Cons. Hyp. 183 aa; 31% ID, 47% Pos.) | ML0407 (Cons. Hyp. 216 aa; 33% ID, 54% Pos.) |

| _5168d (481 aa) | _6450 (Hyp. 420 aa; 36% ID, 53% Pos.); _5503 (Hyp. 471 aa; 37% ID, 50% Pos.) | |||

5168a-c and 6446, 6447, 6449 show significant homologies with the esp genes of M. tuberculosis (Rv3616-3614; Fig. 4). The esp operon encodes proteins required for secretion of EsxAB by the ESX-1 secretion apparatus (Fortune et al., 2005; MacGurn et al., 2005). EspA (Rv3616) is also secreted, in a process dependent on the co-secretion of EsxAB (Fortune et al., 2005). It had been suggested that esp encodes pathogen-specific proteins, since the operon is not present in the M. smegmatis donor strain, mc2155; our discovery of an operon, encoding esp homologues, in the M. smegmatis recipient indicates that the absence of esp in the donor is simply strain variation. The similarity of the gene products encoded from the two M. smegmatis operons with those proteins encoded from the M. tuberculosis esp operon, suggests that the M. smegmatis proteins will also interact with the ESX-1 apparatus. Moreover, these results underscore the intertwining of the ESX-1 and DNA transfer processes. Our bioinformatic analyses have identified paralogues of these esp recipient genes elsewhere in the M. smegmatis genome, most notably at the 5′-end of of esx-1 (Msmeg_0055, 0056, 0058; Fig. 4). The sequence similarity of esp-encoded genes to genes at the 5′-end of esx-1 (Fig. 1) had been noted for M. tuberculosis, M. bovis and M. marinum (Abdallah et al., 2007; Fortune et al., 2005; MacGurn and Cox, 2007).

ESX-1 activity of recipient mutants

The ESX-1 apparatus is required for secretion of EsxA and EsxB in M. tuberculosis, M. marinum and M. smegmatis. However, for M. smegmatis this requirement has only been examined in the donor strain, mc2155 (Converse and Cox, 2005). To establish whether this requirement holds for the recipient strain, we performed Western analyses on the culture filtrates of wild-type and mutant-recipient derivatives. Antibodies raised against a protein fusion of the M. smegmatis EsxA and EsxB proteins (BC & KMD in prep.) were used to monitor their secretion. As expected, the wild-type donor and recipient strains both secrete EsxA and EsxB (Fig. 5). However, we have focused on EsxB secretion as the antibodies recognize EsxB far more efficiently, providing a higher degree of confidence in the limits of EsxB detection. Secretion occurs under conditions in which little cell lysis is observed; antibodies directed against the cytoplasmic protein, GroEL, detected only minor amounts of GroEL in the culture filtrate compared with the cytoplasmic fractions (Fig. S1). Consistent with previous observations in mc2155 (Converse and Cox, 2005), we find that an insertion in the recipient homologues of Msmeg_0057, 0060, 0062 and 0083 prevents EsxB secretion, indicating these proteins play a similar role in the recipient (Fig. 5, and summarized in Fig. 1). For each of the mutants, EsxB was detected in the whole cell extract, indicating that the lack of secretion was not due to a lack of protein expression. We also observed, for the first time, in M. smegmatis that disruption of Msmeg_0056, 0059 or 0063 interfered with EsxB secretion. This requirement is in keeping with other studies on homologues of 0059 and 0063 in M. marinum and M. tuberculosis (Rv3868 and Rv3872 respectively). A requirement in ESX-1 secretion for Msmeg_0056 or its homologue (Rv3865), has not been described previously.

Fig. 5.

A majority of transfer-defective insertions map to the esx-1 locus and disrupt ESX-1 activity.

A. A map of the M. smegmatis chromosome showing sites of transfer-defective insertions; charcoal circles indicate insertions that disrupt EsxAB secretion; open circles exhibit wild-type EsxAB secretion.

B. Representative Western analyses showing the genetic requirements for ESX-1 activity, as monitored by EsxB secretion. Top panel: A majority of insertions in esx-1 disrupt secretion into the culture supernatant (e.g. those insertions in Msmeg_0059, 0062), as compared to the wild-type control (MKD8). However, insertions in Msmeg_0071 and 0076 result in wild-type levels of EsxB secretion but are defective in recipient function. In addition, insertions in Msmeg_0044, 0045 and 5447, which are not esx-1 genes, disrupt secretion, indicating that genes other than those associated with esx-1 mediate ESX-1 activity. Lower panel; The presence of EsxB in total cell lysates indicates that EsxB is stably expressed in the mutants and that its absence from the culture filtrate is due to disruption of ESX-1 activity.

Not all genes within the esx-1 locus are required for EsxAB secretion

Insertions within 0070R, 0071R and 0076R present an unusual case, as the mutations reside within esx-1 and specifically inhibit DNA transfer and not EsxB secretion (Fig. 5, Table 1). Wild-type EsxB secretion was also observed with mutants of the donor homologues, Msmeg_0071 and 0076 (data not shown). Thus, EsxB secretion is necessary but not sufficient for DNA transfer functions in both the donor and recipient. The effect of the mutations and the conservation of 0070R, 0071R and 0076R within the esx-1 operon suggests they contribute to ESX-1 activity by an alternate mechanism. The respective homologues of MSMEG0071 and 0076 in M. marinum and M. tuberculosis are Rv3879 and Rv3881. Recent studies showed that Rv3881 is secreted, and that this secretion requires protein-protein interactions with Rv3879. The dependence of Rv3881 secretion on Rv3879 led to the proposal that there are at least two independent secretory pathways using the core ESX-1 machinery (EsxAB/Rv3871 and Rv3879/3881; (McLaughlin et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2007). Thus, by analogy, 0071 and 0076 could mediate a second secretion pathway, which is also necessary for DNA transfer.

Identification of non-esx-1 genes required for EsxAB secretion

As part of the Western analysis, we determined the EsxB secretion profile for non-esx-1, recipient-defective mutants (Fig. 5A). Not surprisingly, the majority of the insertion mutants secreted EsxB at levels similar to the wild-type control (data not shown). However, we found three non-esx-1 genes that were required for EsxB secretion. Five insertions mapped to Msmeg_0044 and 0045, which form part of a three-gene operon 7 kb upstream of esx-1 (Fig. 2A). Notably EsxB secretion from 0044 mutants was abolished, and secretion from a 0045 mutant was attenuated. A transfer-defective insertion in Msmeg_5447 also disrupted secretion. 5447 encodes a mannosyl transferase (PMT-1) with 12-membrane-spanning domains; this protein is conserved in M. tuberculosis (Rv1002; (VanderVen et al., 2005). Secreted proteins are known targets of PMT-1, including the secreted immunogenic protein MPT32. Although we have no evidence that ESX-1 proteins are glycosylated, only EsxA and EsxB have been investigated thus far for this post-translational modification (Dobos et al., 1996; Sorensen et al., 1995). The 5447 mutant protein may interfere with secretion indirectly by altering membrane integrity, but an intriguing possibility is that the enzyme directly affects secretion by modifying either membrane components of the ESX-1 apparatus or proteins secreted by the apparatus. The observation that mutations in both 0044 and 5447 disrupt both DNA transfer and ESX-1 translocation confirms the functional intertwining of the two processes, and is further underscored by our isolation of multiple insertions in the 0044 and 0045 genes.

Discussion

DNA transfer provides a unique perspective on ESX-1

The results presented in this paper underscore the functional relationship between the process of DNA transfer and the process of ESX-1 mediated secretion in M. smegmatis. Many (38%) of the transfer-defective insertions mapped to the esx-1 locus; thus, recipient function is the first example of an “essential” role for ESX-1 secretion. This absolute requirement for a functional ESX-1 apparatus contrasts with the “attenuated” virulence phenotype for ESX-1 mutants of M. tuberculosis. Consequently, DNA transfer has great potential as a genetic screen through which ESX-1 mutants can be identified, especially as the assay is quantifiable, and is carried out under BSLII conditions with the genetically amenable M. smegmatis. This genetic potential is validated by the identification of transfer-defective insertions that map outside the esx-1 locus, yet still influence ESX-1 secretion. Eight insertions identified genes that are either paralogues of esp genes, or are essential for EsxB secretion but had not been previously linked to ESX-1 activity. These genes would not have been identified based on their predicted functions, nor would they have been identified based on similarities of their encoded proteins with other esx-1-encoded proteins: M. smegmatis proteins 0044 and 0045 have no homologues within the Mycobacteria, and the two operons similar to esp (Msmeg_6446-6449 and RSR-II) express proteins with only weak similarities to each individual Esp protein. In addition, RSR-I and RSR-II are unique to the recipient, and so would not have been identified from the sequence of the donor genome. The current data are based on the analysis of 49 transfer-defective mutants from a screen of only 5,286 insertions, which makes it unlikely that our screen is saturated and suggests that additional transfer and ESX-1 genes await identification.

A second secretory apparatus, Tad, has similar effects on DNA transfer compared to ESX-1

Analysis of the genes surrounding Msmeg_6169(tadA) indicates that they form an operon (Msmeg_6171-6165) syntenous with tad loci, present in other bacteria and M. tuberculosis and M. bovis (Table S1; P. Planet, pers. comm). The Tad polypeptides are hypothesized to form a secretory apparatus in the membrane, of which a major structural component is the Flp pilus encoded by the flp gene product (Tomich et al., 2007). Note that flp is different from the proposed pilus-like protein (Rv3312) encoded by M. tuberculosis, which is absent from M. smegmatis (Alteri et al., 2007). Disruption of tadA had opposing affects on transfer in the donor and recipient, as observed with esx-1 mutants. The hyper-conjugative phenotype of tadAΔ donors makes a possible role of Flp pili in maintaining cell-cell contact unlikely. However, the fact that Tad is hypothesized to form a secretory apparatus, although its substrates have not been identified, suggests that, like ESX-1, it is the Tad-secreted proteins that are modulating DNA transfer. The tadA mutant had no affect on EsxB secretion, and so it would seem most likely that Tad secretes a different set of proteins, which, together with those secreted by ESX-1, provide essential recipient functions. Identifying the proteins secreted by Tad and determining their functional interactions with ESX-1 substrates will be key to determining their influence on transfer. Moreover, if ESX-1 and Tad secretion have common targets it would seem likely that, as for ESX-1, Tad will play a role in virulence of M. tuberculosis.

Conservation of core esx-1 gene function

The esx-1 genes identified in this work both confirm and extend the work of others studying ESX-1 secretion in M. smegmatis, M. tuberculosis and M. marinum. Such corroborative data were not unexpected, given the high conservation, among species, of the core genes, and their organization (Fig. 1). However, subtle discrepancies exist between the different studies on the effect of mutations in genes at the 5′-end of the locus. For example, we show that an insertion in either Msmeg_0056 or 0057 disrupts both DNA transfer and EsxB secretion. Similar defects in secretion were observed in M. marinum and M. smegmatis (Gao et al., 2003; Converse and Cox, 2005;), with disruptions of the 0057 homologue (Rv3866), but not in M. tuberculosis (Brodin et al., 2006; Converse and Cox, 2005; Gao et al., 2003). A requirement for Msmeg_0056 has not been previously described, although 0056 is related to the esp homologue Rv3615, and to the recipient paralogues that we describe here in M. smegmatis, 5168b and 6447 (Table 3, Fig. 4).

The 3′ half of esx-1 differs between donor and recipient, and also between species

The 3′ half of the esx-1 locus from Msmeg_0069 to 0083 is considerably less well conserved, in both gene order and content, between M. smegmatis and its relatives (M. tuberculosis genes Rv3878-Rv3883; Fig. 1). This heterogeneity could be an indicator of genes encoding species-specific functions. The differences not only include the presence of additional genes (Msmeg_0077 to 0080), but also rearrangement of conserved genes. Msmeg_0071 and 0076 have each been inverted with respect to the locus, but independently of one another. Several of the additional genes are paralogues of other esx-1 genes (e.g., Msmeg_0080 shows homology with Msmeg_0058, Rv3614 and Rv3867, Fig. 1, Table 3), suggesting that a series of independent duplication events in M. smegmatis resulted in the acquisition of additional gene copies, which have subsequently evolved to perform non-overlapping functions necessary for ESX-1 activity.

The region spanning Msmeg_0069-76 also differs considerably between donor and recipient strains. The differences include the loss of three IS elements (Msmeg_0072-0074) and Msmeg_0075 (which is a duplication of the 3′ end of 0071), such that 0071R and 0076R are immediately adjacent to one another in the recipient genome (Fig. 3). It is possible that this deletion was generated by homologous recombination between pre-existing copies of Msmeg_0071 and 0075. The 3′ end of RSR-I contains three genes with only weak similarities to the donor genes Msmeg_0069, 0070 and the 5′-half of 0071. Given that six insertions mapped within Msmeg_0070-0071 it is likely that the many sequence differences, between the donor and recipient copies of these genes, contribute to the different functions of the ESX-1 apparatus in the donor and the recipient. In support of this hypothesis, linkage experiments had mapped genes required for conversion of recipients to donors, to a locus closely associated with the 3′ end of esx-1 (Wang et al., 2005). The highly conserved core components of the translocation apparatus might allow assembly of the secretion machinery, while the proteins encoded in the 3′ region could modulate the transfer process and determine the secretion profile.

Multiple esp homologues exist in M. smegmatis and are linked to DNA transfer

Thus far, the only non-esx-1 locus described as necessary for ESX-1 activity in M. tuberculosis is the esp locus (Fortune et al., 2005; MacGurn et al., 2005). This locus consists of three genes (espA or Rv3616, Rv3615, and Rv3614), which are required for secretion of the EsxAB heterodimer. Moreover, EspA is secreted by ESX-1, and its secretion and the secretion of EsxAB are interdependent, suggesting the three proteins are secreted as a complex.

We have identified three genes that affect EsxAB secretion (Msmeg_0044, 0045, and 5447). Of particular interest were five insertions that mapped to genes 0044 and 0045, which are the first two genes of a three-gene operon located 7 kb upstream of esx-1 (Fig. 2A). There are no homologues of these three genes found in the M. tuberculosis complex species (Table S1), and the synteny of esx-1 among the mycobacterial species does not extend into this operon. However, the proximity of the Msmeg_0044-0046 operon to the 5′ end of esx-1 (Msmeg_0055) likely reflects a conserved functional linkage between ESX-1 and DNA transfer activities in the recipient.

We found two other loci that we predict will also contribute to ESX-1 activity. In both cases, the operon encodes four genes, and an insertion in the fourth gene disrupts DNA transfer. The two operons are closely related, as indicated by the similarity of their predicted gene products and the order of genes. Moreover, the first three genes of each operon are homologues of those encoded within the esp operon of M. tuberculosis, M. bovis and M. leprae (Fig. 4). One M. smegmatis locus was shown to be unique to the recipient genome (RSR-II), while the second operon (Msmeg_6446-6450) is present in both the donor and recipient (Fig. 4 and Table 3). The identification of at least two esp-like operons in the M. smegmatis recipient sets a precedent for the existence of multiple copies in other mycobacteria encoding the ESX-1 apparatus. We have not yet generated mutations in these esp homologues to determine the role of the two operons in ESX-1 activity. However, the genetic conservation of each operon, combined with their association with a gene required for transfer (5169d and 6450), is highly suggestive that each operon will contribute to ESX-1 activity. As such, we speculate the proteins encoded by the two loci will influence DNA transfer by modifying the ESX-1 secretion profile.

ESX-1, a core machine for multiple secretion pathways

Current hypotheses as to the role of ESX-1 in promoting virulence have focused on defining a role for EsxA and EsxB (Abdallah et al., 2007). For example, a considerable amount of attention has been devoted to the activity of secreted EsxAB, in particular, determining whether EsxA exhibits cytolytic activity in the absence of EsxB in vitro (de Jonge et al., 2007; Hsu et al., 2003). However, the EsxA activity would require its dissociation from EsxB, which seems unlikely given the physical stability of the EsxAB heterodimer (Kd, 1 × 10-8M; Renshaw et al., 2002). Another possibility is that EsxA and EsxB are part of the secretion apparatus and do not directly confer virulence; in this scenario the two proteins are present in culture filtrates simply because they are sloughed off during growth. The demonstration that Rv3881, another esx-1 gene product is secreted and contributes to virulence, has led to the proposal that virulence is mediated by multiple proteins secreted by ESX-1 (McLaughlin et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2007). We believe that our findings are consistent with the latter model; in fact, we extend it by proposing that EsxAB act as a courier to deliver the real effector proteins, which are co-secreted and which specify function.

Our sequence analyses indicate that the donor and recipient copies of esxAB are identical. Therefore, any explanation of the role of ESX-1 must explain how secretion of identical proteins (by donor and recipient cells) causes such diametrically opposed effects on DNA transfer (donor secretion negatively regulates transfer; recipient secretion is essential for transfer). In addition, the extracellular targets of EsxAB in our transfer system are other mycobacterial cells (rather than eukaryotic cells), a fact that makes any cytolytic hypothesis for EsxA function seem unlikely. We propose that the ESX-1 apparatus secretes EsxAB, which acts as a courier delivering different mail packages (proteins) depending on particular environmental stimuli. It would be the proteins delivered by EsxAB that would determine the effective function of the complex, which could vary from regulation of conjugation in M. smegmatis, to facilitating survival of M. tuberculosis in a macrophage and the suppression of host responses. This versatility would provide the bacterium with the tremendous benefit of being able to customize its secretory profile according to a particular environmental or nutritional condition. The mutually dependent secretion of Rv3616 and EsxAB by the ESX-1 apparatus in M. tuberculosis supports this hypothesis. Moreover, our identification of multiple homologues of the esp operon in the recipient M. smegmatis strain is entirely consistent with these proteins serving a similar function in M. smegmatis. It also explains why the ESX-1 apparatus (the mail van) is functionally conserved between pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria, and reconciles the opposing effects of esx-1 mutants in the donor and recipient: the substrates (mail) that are delivered by EsxAB (the mailman) provide the specificity. In the case of DNA transfer, we anticipate that some of the recipient-specific proteins identified in the present work will confer donor/recipient specificity.

Experimental procedures

Transposon mutagenesis of MKD8

A mutant transposon insertion library was made in the Smr M. smegmatis recipient, MKD8 (Parsons et al., 1998), using a temperature-sensitive phage to deliver a mariner transposon encoding kanamycin resistance (KmR) (Bardarov et al., 1997; Sassetti et al., 2001). Individual insertions were mapped as previously described (Flint et al., 2004). Briefly, chromosomal BamHI fragments encoding resistance to KmR were cloned and the site of insertion was determined by DNA sequence analysis using primers annealing to the Kmr gene. Here, the chromosomal locations of the insertions and the gene annotations are based on the April 2007 version of the M. smegmatis chromosomal sequence in The Institute for Genomic Research database (http://cmr.jcvi.org/tigr-scripts/CMR/GenomePage.cgi?database=gms). Note that this is the sequence for the donor strain mc2155; we have therefore made an assumption that the location and integrity of the genes between donor and recipient are conserved.

Microtiter Mating Screen

A screen for MKD8 mutants that are defective in conjugation was carried out as described previously, with minor modifications to the protocol (Flint et al., 2004). Mutant (Smr, Kmr) MKD8 cells were grown in a 96-well microtiter dish for 48 h, followed by the addition of wild-type donor, MKD158 (Hygr). The mating between recipient and donor was carried out for 48 h at 30°C. Transconjugants were selected on trypticase soy agar plates containing hygromycin (Hyg) and streptomycin (Sm) and recipients were selected on Sm plates.

Mating Assay

The effect of insertion mutations on recipient activity was determined using a quantitative mating assay to measure the change in conjugation frequency relative to the frequency for the wild-type recipient (Parsons et al., 1998). Frequencies are the average of at least three crosses performed in parallel with wild-type donor and recipient.

Transduction of insertion mutants

Insertion mutants were transduced from the recipient strain into the donor using the generalized transducing phage Bxz1 (Lee et al., 2004). To attain the high titres necessary for transduction, this phage was propagated on the recipient strain before performing transduction of mutant genes into the donor.

Construction of gene deletions

Precise chromosomal deletions of Msmeg_3888-3889 and Msmeg_6169 were created by recombineering according to the published protocol (van Kessel and Hatfull, 2006). Chromosomal regions flanking the target gene were amplified by PCR and cloned in the appropriate orientation on either side of the Hygr gene in pYUB854 (Bardarov et al., 2002). The resulting allele exchange vector was linearized, and introduced into mc2155 expressing the recombinase genes. Hygr recombinants were analyzed by PCR and DNA sequencing to confirm that a precise deletion had been created.

Sequence analysis of recipient-specific regions (RSRs)

In the screen for recipient mutants, four insertion mutations were identified whose surrounding DNA sequence was not found in the donor genome sequence in the TIGR database. The sequences of these RSRs and the locations of the transposon insertions were determined by several methods, outlined below. Primer sequences for these studies are available on request.

First, the maximum extent of sequence information surrounding the four insertions was obtained by primer walking through each region. This was repeated until the BamHI sites, used for cloning, were detected at either end of the cloned fragment containing the transposon insertion.

For RSR-II, the above method resulted in sequence that aligned to Msmeg_5168 in the donor genome, suggesting that this RSR is either a replacement of adjacent genes, or an insertion, with respect to the donor sequence. PCR was performed on the recipient chromosome using an RSR-specific primer and a primer annealing to the putative adjacent gene Msmeg_5169. A PCR product was detected, and was subsequently sequenced; the sequence confirmed that RSR-II was a precise insertion between the donor genes Msmeg_5168 and 5169. There were also several nucleotide changes within the sequence of Msmeg_5169 in the recipient.

The recipient-specific sequences surrounding two of the identified insertions showed that these insertions are 212 bp apart. This was confirmed by PCR, which showed that the third insertion also mapped to this region, now called RSR-I. PCR was carried out to allow detection of DNA products up to 7 kb in length, using Fail Safe™ DNA polymerase (Epicentre® Biotechnologies), an extension time of 7 minutes, and MKD8 genomic DNA as a template. Primers were designed to read out from the 3′ end of the known RSR-I sequence flanking each insertion and were paired in all combinations to allow detection of all possible PCR products. DNA sequence analysis of PCR products confirmed that the three insertions mapped within RSR-I, which is at least 3 kb.

Further sequence information for RSR-I was obtained by chromosome walking (adapted from Clontech Universal GenomeWalker). Briefly, the chromosome was digested with four restriction enzymes (EcoRV, NaeI, PmlI, and SmaI), followed by ligation to a double-stranded adaptor. Primers designed to anneal to the known RSR-II sequence and to the ligated adaptor were used in a primary PCR reaction in which the ligation products were the templates. This PCR was followed by a second, nested-PCR that used internal primers to ensure product specificity. PCR products from the nested-PCR were gel purified and subjected to DNA sequence analysis. As the sequence was assembled, new genome-specific oligonucleotide primers were used in subsequent walking steps.

RSR-I and RSR-II were translated into open reading frames (orfs) using BCM search launcher (http://searchlauncher.bcm.tmc.edu/seq-util/Options/sixframe.html). Those orfs encoding proteins greater than 55 amino acids long were used in BlastP searches at the TIGR site (http://tigrblast.tigr.org/cmr-blast/) using the Omniome Pep database. The RSR-I and RSR-II DNA sequences have been submitted to GenBank.

Western protocols

To screen for ESX-1 mutants, we tested for the presence of EsxB in culture filtrates and cell pellets collected from recipient-defective strains using standard immunoblotting methods. 40-Fold concentrated supernatants were prepared from the culture filtrates of M. smegmatis strains grown to log phase in 15 ml Sauton's medium using Amicon Ultra Spin Columns (3 Kd, MW cut-off). Cellular lysates were prepared by resuspending pelleted cells in 0.4 ml water and 0.4 ml SDS loading buffer, followed by heating at 95 °C for 10 minutes. Equivalent cell volumes of the resulting culture filtrate and cellular lysate were separated on a 15% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to Amersham HyBond-P PVDF membrane, and probed with rabbit antibodies recognizing an EsxAB protein fusion (BC & KMD, Manuscript in prepn. and Covance, Inc.). Secondary antibody and detection reagents were obtained from Amersham ECL Western Breeze kit (GE Healthcare) and were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Supernatants were further probed with antibodies recognizing GroEL to detect possible contamination with cellular protein.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Todd Gray for advice on chromosome walking; Erica Dirks for help in generating deletions of Msmeg_3888 and Msmeg_3889; Dr. Adri Verschoor and members of the Derbyshire laboratory for comments on this manuscript. The Wadsworth Center Molecular Genetics Core performed DNA sequence analysis. EB was an Emerging Infectious Diseases Fellow funded by the CDC, and administered by the Association of Public Health Laboratories. BC was supported by funding from a NIAID training grant (1T32AI055429), and grants AI070666 and AI042308 to KMD.

References

- Abdallah AM, Gey van Pittius NC, Champion PA, Cox J, Luirink J, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Appelmelk BJ, Bitter W. Type VII secretion--mycobacteria show the way. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:883–891. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alteri CJ, Xicohtencatl-Cortes J, Hess S, Caballero-Olin G, Giron JA, Friedman RL. Mycobacterium tuberculosis produces pili during human infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5145–5150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602304104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardarov S, Kriakov J, Carriere C, Yu S, Vaamonde C, McAdam RA, Bloom BR, Hatfull GF, Jacobs WRJ. Conditionally replicating mycobacteriophages: A system for transposon delivery to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 1997. pp. 10961–10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardarov S, Bardarov S, Jr, Pavelka MS, Jr, Sambandamurthy V, Larsen M, Tufariello J, Chan J, Hatfull G, Jacobs WR., Jr Specialized transduction: an efficient method for generating marked and unmarked targeted gene disruptions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. bovis BCG and M. smegmatis. Microbiology. 2002;148:3007–3017. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr MA, Wilson MA, Gill WP, Salamon H, Schoolnik GK, Rane S, Small PM. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodin P, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P, Cole ST, Brosch R. ESAT-6 proteins: protective antigens and virulence factors? Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodin P, Majlessi L, Marsollier L, de Jonge MI, Bottai D, Demangel C, Hinds J, Neyrolles O, Butcher PD, Leclerc C, Cole ST, Brosch R. Dissection of ESAT-6 system 1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and impact on immunogenicity and virulence. Infect Immun. 2006;74:88–98. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.88-98.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascales E, Christie PJ. The versatile bacterial type IV secretion systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:137–149. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion PA, Stanley SA, Champion MM, Brown EJ, Cox JS. C-terminal signal sequence promotes virulence factor secretion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2006;313:1632–1636. doi: 10.1126/science.1131167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Converse SE, Cox JS. A protein secretion pathway critical for Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence is conserved and functional in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1238–1245. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1238-1245.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coros A, DeConno E, Derbyshire KM. IS6110, a Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex-specific insertion sequence, is also present in the genome of Mycobacterium smegmatis, suggestive of lateral gene transfer among mycobacterial species. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:3408–3410. doi: 10.1128/JB.00009-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin KH, Ehrt S, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Weich N, Nathan CF. The proteasome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for resistance to nitric oxide. Science. 2003;302:1963–1966. doi: 10.1126/science.1091176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge MI, Pehau-Arnaudet G, Fretz MM, Romain F, Bottai D, Brodin P, Honore N, Marchal G, Jiskoot W, England P, Cole ST, Brosch R. ESAT-6 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis dissociates from its putative chaperone CFP-10 under acidic conditions and exhibits membrane-lysing activity. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6028–6034. doi: 10.1128/JB.00469-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiuseppe Champion PA, Cox JS. Protein secretion systems in Mycobacteria. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1376–1384. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobos KM, Khoo KH, Swiderek KM, Brennan PJ, Belisle JT. Definition of the full extent of glycosylation of the 45-kilodalton glycoprotein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2498–2506. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2498-2506.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanning AS, Anderson JM. PDZ domains: fundamental building blocks in the organization of protein complexes at the plasma membrane. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:767–772. doi: 10.1172/JCI6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festa RA, Pearce MJ, Darwin KH. Characterization of the proteasome accessory factor (paf) operon in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:3044–3050. doi: 10.1128/JB.01597-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint JL, Kowalski JC, Karnati PK, Derbyshire KM. The RD1 virulence locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulates DNA transfer in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12598–12603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404892101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune SM, Jaeger A, Sarracino DA, Chase MR, Sassetti CM, Sherman DR, Bloom BR, Rubin EJ. Mutually dependent secretion of proteins required for mycobacterial virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10676–10681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504922102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao LY, Groger R, Cox JS, Beverley SM, Lawson EH, Brown EJ. Transposon mutagenesis of Mycobacterium marinum identifies a locus linking pigmentation and intracellular survival. Infect Immun. 2003;71:922–929. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.922-929.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao LY, Guo S, McLaughlin B, Morisaki H, Engel JN, Brown EJ. A mycobacterial virulence gene cluster extending RD1 is required for cytolysis, bacterial spreading and ESAT-6 secretion. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1677–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gey Van Pittius NC, Gamieldien J, Hide W, Brown GD, Siezen RJ, Beyers AD. The ESAT-6 gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other high G+C Gram-positive bacteria. Genome Biol. 2001;2:1–18. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-10-research0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinn KM, Hickey MJ, Mathur SK, Zakel KL, Grotzke JE, Lewinsohn DM, Smith S, Sherman DR. Individual RD1-region genes are required for export of ESAT-6/CFP-10 and for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:359–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T, Hingley-Wilson SM, Chen B, Chen M, Dai AZ, Morin PM, Marks CB, Padiyar J, Goulding C, Gingery M, Eisenberg D, Russell RG, Derrick SC, Collins FM, Morris SL, King CH, Jacobs WR., Jr The primary mechanism of attenuation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin is a loss of secreted lytic function required for invasion of lung interstitial tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12420–12425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635213100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachlany SC, Planet PJ, Bhattacharjee MK, Kollia E, DeSalle R, Fine DH, Figurski DH. Nonspecific adherence by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans requires genes widespread in bacteria and archaea. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6169–6176. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.6169-6176.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachlany SC, Planet PJ, DeSalle R, Fine DH, Figurski DH. Genes for tight adherence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: from plaque to plague to pond scum. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:429–437. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kriakov J, Vilcheze C, Dai Z, Hatfull GF, Jacobs WR., Jr Bxz1, a new generalized transducing phage for mycobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;241:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis KN, Liao R, Guinn KM, Hickey MJ, Smith S, Behr MA, Sherman DR. Deletion of RD1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis mimics bacille Calmette-Guerin attenuation. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:117–123. doi: 10.1086/345862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGurn JA, Raghavan S, Stanley SA, Cox JS. A non-RD1 gene cluster is required for Snm secretion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:1653–1663. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGurn JA, Cox JS. A genetic screen for Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants defective for phagosome maturation arrest identifies components of the ESX-1 secretion system. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2668–2678. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01872-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahairas GG, Sabo PJ, Hickey MJ, Singh DC, Stover CK. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1274–1282. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1274-1282.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin B, Chon JS, MacGurn JA, Carlsson F, Cheng TL, Cox JS, Brown EJ. A mycobacterium ESX-1-secreted virulence factor with unique requirements for export. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e105. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi Y, Suga K, Tokunaga T. Multiple mating types of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Japanese Journal of Microbiology. 1976;20:435–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1976.tb01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallen MJ. The ESAT-6/WXG100 superfamily -- and a new Gram-positive secretion system? Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:209–212. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons LM, Jankowski CS, Derbyshire KM. Conjugal transfer of chromosomal DNA in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Micro. 1998;28:571–582. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planet PJ, Kachlany SC, Fine DH, DeSalle R, Figurski DH. The Widespread Colonization Island of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Nat Genet. 2003;34:193–198. doi: 10.1038/ng1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pym AS, Brodin P, Brosch R, Huerre M, Cole ST. Loss of RD1 contributed to the attenuation of the live tuberculosis vaccines Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium microti. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:709–717. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw PS, Panagiotidou P, Whelan A, Gordon SV, Hewinson RG, Williamson RA, Carr MD. Conclusive evidence that the major T-cell antigens of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex ESAT-6 and CFP-10 form a tight, 1:1 complex and characterization of the structural properties of ESAT-6, CFP-10, and the ESAT-6*CFP-10 complex. Implications for pathogenesis and virulence. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21598–21603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Comprehensive identification of conditionally essential genes in mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12712–12717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231275498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen AL, Nagai S, Houen G, Andersen P, Andersen AB. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1710-1717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SA, Raghavan S, Hwang WW, Cox JS. Acute infection and macrophage subversion by Mycobacterium tuberculosis require a specialized secretion system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13001–13006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235593100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teutschbein J, Schumann G, Mollmann U, Grabley S, Cole ST, Munder T. A protein linkage map of the ESAT-6 secretion system 1 (ESX-1) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol Res. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomich M, Planet PJ, Figurski DH. The tad locus: postcards from the widespread colonization island. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:363–375. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kessel JC, Hatfull GF. Recombineering in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Methods. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nmeth996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderVen BC, Harder JD, Crick DC, Belisle JT. Export-mediated assembly of mycobacterial glycoproteins parallels eukaryotic pathways. Science. 2005;309:941–943. doi: 10.1126/science.1114347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Parsons LM, Derbyshire KM. Unconventional conjugal DNA transfer in mycobacteria. Nat Genet. 2003;34:80–84. doi: 10.1038/ng1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Derbyshire KM. Plasmid DNA transfer in Mycobacterium smegmatis involves novel DNA rearrangements in the recipient, which can be exploited for molecular genetic studies. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1233–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Karnati PK, Takacs CM, Kowalski JC, Derbyshire KM. Chromosomal DNA transfer in Mycobacterium smegmatis is mechanistically different from classical Hfr chromosomal DNA transfer. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:280–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver LH, Kwon K, Beckett D, Matthews BW. Corepressor-induced organization and assembly of the biotin repressor: A model for allosteric activation of a transcriptional regulator. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences %R; 2001. pp. 6045–6050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Laine O, Masciocchi M, Manoranjan J, Smith J, Du SJ, Edwards N, Zhu X, Fenselau C, Gao LY. A unique Mycobacterium ESX-1 protein co-secretes with CFP-10/ESAT-6 and is necessary for inhibiting phagosome maturation. Molecular Microbiology. 2007;66:787–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo HJ, Waksman G. Unveiling Molecular Scaffolds of the Type IV Secretion System. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:1919–1926. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.1919-1926.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]