Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of a computer-based version of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for substance dependence.

Methods

This was a randomized clinical trial in which 77 individuals seeking treatment for substance dependence at an outpatient community setting were randomized to standard treatment or standard treatment with biweekly access to computer-based training in CBT (CBT4CBT).

Results

Treatment retention and data availability were comparable across the treatment conditions. Participants assigned to the CBT4CBT condition submitted significantly more urine specimens that were negative for any type of drugs and tended to have longer continuous periods of abstinence during treatment. The CBT4CBT program was positively evaluated by participants. In the CBT4CBT condition, outcome was more strongly associated with treatment engagement than in TAU; further, completion of homework assignments in CBT4CBT was significantly correlated with outcome and a significant predictor of treatment involvement.

Conclusions

These data suggest that CBT4CBT is an effective adjunct to standard outpatient treatment for substance dependence and may provide an important means of making CBT, an empirically validated treatment, more broadly available.

Keywords: Behavior Therapy, Cognitive Therapy, Psychoactive Substance Use Disorder, Computers

Introduction

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has a comparatively strong level of empirical support across a range of psychiatric disorders (1-3), including substance use disorders (1, 4, 5). Despite evidence of positive and durable outcome (6, 7), CBT remains rarely implemented in the range of settings where individuals with substance use disorders are treated (8). There are a number of obstacles to delivering CBT and other empirically validated therapies in clinical practice, including the limited availability of professional and specialty training programs that provide high quality training, supervision and certification in CBT (9), high rates of clinician turnover and lack of a CBT-trained workforce in many treatment settings (10-12), the relative complexity and cost of training clinicians in CBT (13, 14), as well as high case loads and limited resources. Available evidence suggests that while many clinicians report using CBT they tend to overestimate their use of this and other empirically supported therapies (15).

Hence, computer-assisted delivery of CBT, if demonstrated to be feasible and effective, could play an important role in broadening its availability and improving the quality of addiction treatment. Computer-assisted therapy could provide a comparatively low-cost means of teaching CBT skills to more substance users and allow clinicians to focus on acute concerns and problems of the individuals with whom they work. Moreover, by standardizing treatment delivery, computer-assisted training could also provide more consistent, and perhaps more effective, teaching and demonstration of CBT than is available in some settings, through its capacity to convey information via a range of media (text, video, audio instruction, interactive exercises). The ability to select or tailor content to address the needs of particular individuals allows for choice of different topics, control over the speed of presentation of information, and repetition of modules when necessary. These flexible parameters may especially important for substance abusers, many of whom experience significant cognitive impairment, including memory and concentration problems, particularly in the early stages of treatment (16, 17).

In the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders, computer-assisted delivery of CBT has been demonstrated in randomized trials to be both effective (18-25) and cost effective (26). However, there have been few evaluations of computer-assisted treatment, of any type, for the addictions. Much of this work has been done in the area of smoking, where several randomized trials of predominantly cognitive-behavioral interventions or self-help guidelines delivered via computers/internet have indicated positive effects on quit rates or attempts (27-29). Computer-assisted brief motivational approaches and self-control training programs have shown promise in randomized controlled trials with problem drinkers (30, 31) and college students (32). A computer-based HIV/AIDS education program was more effective than counselor-provided education in helping injection drug users learn and retain information about HIV, although both approaches were comparable in reducing HIV risk behaviors (33).

In this report, we describe main outcome findings from a randomized clinical trial of a six-module computer-based training for cognitive behavioral therapy (‘CBT4CBT’), wherein individuals entering a community-based clinic were randomized to standard treatment (treatment as usual, TAU) or TAU plus CBT4CBT over a period of 8 weeks. Given the established efficacy of CBT across a range of addictions and the unavailability of empirically validated therapies in many community based settings, CBT4CBT was evaluated in terms of one model of how it might be used in clinical practice, that is, as a stand-alone addition to regular clinical practice and delivered to a heterogeneous group of individuals seeking treatment for addiction. The primary hypothesis was that individuals assigned to CBT4CBT would reduce their frequency of substance use and submit fewer positive urine toxicology screens than those randomized to TAU. Given data from previous CBT trials linking compliance, homework completion and outcome (34-36), a secondary hypothesis was that treatment engagement, including homework completion, in the CBT4CBT program would be more strongly linked to positive substance use outcomes than in TAU.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from individuals seeking treatment at Liberation Program's Mill Hill clinic, a community based outpatient substance abuse treatment provider in Bridgeport, CT. Participants were English-speaking adults who met DSM-IV criteria for any current substance dependence disorder, including alcohol, cocaine, opioids, or marijuana. Exclusion criteria were minimal to facilitate recruitment of a clinically representative group of individuals seeking treatment in a community setting. Thus, individuals were excluded only if (1) they had not used alcohol or illegal drugs within the past 28 days or failed to meet DSM-IV criteria for a current substance dependence disorder, (2) had an untreated psychotic disorder which precluded outpatient treatment, or (3) were unlikely to be able to complete 8 weeks of outpatient treatment due to a planned move or pending court case from which incarceration was likely to be imminent.

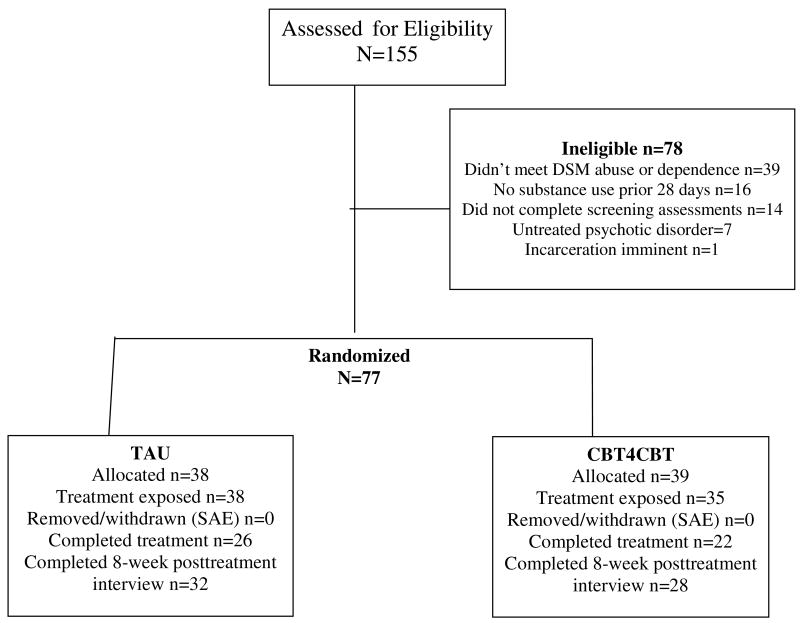

As shown in the participant flow diagram (Figure 1), 77 of the 155 individuals screened were determined to be eligible for the study, provided written informed consent and were randomized. Following a complete description of the study and provision of written informed consent approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigations Committee, participants were randomized to either TAU or CBT4CBT, using a computerized urn randomization program (37) to balance treatment groups with respect to primary substance used, gender and ethnicity.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram: Flow of participants through the protocol

Treatments

All participants were offered standard treatment at the clinic, which consisted of weekly individual and group sessions of general drug counseling. All participants also met twice weekly with an independent clinical evaluator who collected urine and breath specimens, assessed recent substance use and monitored other clinical symptoms. Those randomized to the CBT4CBT condition were provided access to the computer program in a small private room within the clinic. A research associate guided participants through their initial use of the CBT4CBT program and was available to answer questions and assist participants each time they used the program. Participants accessed the program through an ID/password system to protect confidentiality.

The CBT4CBT program was intended to be user-friendly, requiring no previous experience with computers and minimal use of text-based material. The multimedia style of the program was based on elementary-level computer learning games, and presentation of material was done in a range of formats including graphic illustrations, videotaped examples, verbal instructions and audio voice-overs, interactive assessments and practice exercises.

The program consisted of six lessons, or modules, the content of which was based closely on a NIDA-published CBT manual (38) used in several previous randomized controlled trials in a range of substance-using populations (6, 39, 40). The modules covered the following core concepts: (1) understanding and changing patterns of substance use, (2) coping with craving, (3) refusing offers of drugs and alcohol, (4) problem-solving skills, (5) identifying and changing thoughts about drugs and alcohol, and (6) improving decision-making skills. The first module provided a brief explanation of how to use and navigate the program; following completion of the first module, participants could choose to access the modules in any order they preferred and repeat any section or module as many times as they wished.

Each module in the CBT4CBT program was structured as follows: First, the key concept for each module was introduced through a brief ‘movie’ using actors and realistic settings depicting situations in which an individual was offered drugs or had to cope with a challenging situation in which substance use was likely. Next, after the narrator explained the key skill covered in that module with graphics and voice-overs, the ‘movie’ was repeated, this time with a different ending as the same characters applied the skills to change the outcome of the situation so as to avoid substance use (e.g. emphasis was on how individuals could use the CBT skills to ‘change their story’). Additional videotaped vignettes were used to reinforce the skills taught (e.g., in the ‘refusal skills’ module, the user could click buttons to see additional examples of the characters demonstrating assertive versus aggressive versus passive responding). Next, each module include an interactive assessment followed by a short vignette with an actor explaining how use of each skill had helped him/her avoid substance use and how each CBT principle could be applied to other problems; the intention of this section was to address common areas of resistance in CBT (“Why should I do homework?”) and to emphasize how CBT skills could be generalized beyond substance use issues. Finally, each module concluded with the narrator providing a review of the key points covered, followed by the characters demonstrating how they would complete the ‘homework’ or practice assignment for that module based on the situation depicted in the movie. Participants were then given an identical practice assignment and reminder sheet to take with them.

This general sequence of activities was intended to be similar to the CBT manual's (38) therapist guidelines for structuring sessions (introduction of the skill topic, didactic instruction, practice via modeling and role-plays, assessment of the patient's understanding of the material, and assignment of homework). However, this sequence also capitalized on the unique advantages of multimedia computer-assisted instruction, including presentation of information in a range of media formats. Each module was intended to require about 45 minutes to complete, depending on the speed with which the user navigated the program and the amount of material he or she selected to access or repeat.

Assessments

Participants were assessed before treatment, twice weekly during treatment, and at the 8-week treatment termination point by an independent clinical evaluator. Participants were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)(41) prior to randomization to establish substance use and psychiatric diagnoses. The Substance Abuse Calendar, similar to the Timeline Follow Back (42, 43), was administered weekly during treatment to collect detailed day-by-day self-reports of drug and alcohol use throughout the 56-day treatment period as well as for the 28-day period prior to randomization.

Participant self-reports of illegal drug use were verified through urine toxicology screens that were obtained at every assessment visit. Of 578 urine specimens collected during the treatment phase of the study (between days 4 and 56), the majority were consistent with participant self report in that only 58 (10%) were positive for drugs in cases where the participant had denied recent use during the period the drug's metabolites are typically detectable in urine (3 days for cocaine and opioids, 7 for marijuana). Using these cutoffs, 23 urines were submitted that were positive for cocaine when the participant had denied cocaine use in the past 3 days, 31 were positive for marijuana when the participant had denied marijuana use in the past 7 days, and 9 were positive for opioids when the participant had denied opioid use in the past 3 days. This rate is consistent with previous studies of substance-dependent samples (43-45). Breathalyzer samples were also collected at each assessment visit; none indicated recent alcohol use.

Data analyses

The a priori primary outcome measures were results of urine toxicology screens (operationalized as the number of drug-positive urine samples collected during treatment) and frequency of substance use (operationalized as the percentage of days in the 56-day treatment period the participant reported using alcohol or any illegal drug). Secondary outcomes included the longest period of abstinence attained during treatment as well as retention in treatment. The principal data analytic strategy was analysis of variance for the two primary outcome variables for the 77 participants who were randomized to treatment (intention to treat) and the 73 participants who initiated treatment (treatment-exposed). Four participants who were randomized but did not initiate treatment had been assigned to CBT4CBT; of these, 3 were arrested after randomization but prior to the onset of treatment Results were highly consistent across analysis samples and therefore results from the treatment-exposed sample are presented below (the four individuals who dropped out immediately after randomization were not exposed to any protocol treatment, could not be located for any further assessments, and therefore contributed minimally to the dataset as no urine or self-report data were available).

Results

Sample description

Table 1 presents baseline demographic characteristics and substance use and psychiatric diagnoses of the 73 participants who initiated treatment. Of these, 43% were female, 46% identified themselves as African American, 34% as European-American, 12% as Hispanic, and 6% as Native American. Most were single or divorced, 77% were unemployed, and 75% had completed high school. Over one third (37%) of the sample reported they were on probation or parole, and 27% indicated their application for treatment had been prompted by the criminal justice system.

Table 1. Baseline demographic variables and substance use by treatment condition.

| CBT4CBT n=35

|

TAU n=38

|

Total n=73

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % | X2 | df | p |

| Number (%) female | 15 | 42.9 | 16 | 42.1 | 31 | 42.5 | 0.00 | 1 | .95 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| African American | 18 | 46.2 | 17 | 44.7 | 35 | 45.5 | 1.02 | 3 | .80 |

| European American | 10 | 28.6 | 15 | 39.5 | 25 | 34.2 | |||

| Latin American | 5 | 14.3 | 4 | 10.5 | 9 | 12.3 | |||

| Native American | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 5.3 | 4 | 5.5 | |||

| Married or in stable relationship | 9 | 25.7 | 7 | 18.4 | 16 | 21.9 | 0.57 | 1 | .45 |

| Employed, full or part time | 7 | 20.0 | 10 | 26.3 | 17 | 23.3 | 0.41 | 1 | .52 |

| Completed high school education | 25 | 71.4 | 30 | 78.9 | 55 | 75.4 | 0.55 | 1 | .46 |

| Primary substance use problem | |||||||||

| Cocaine | 20 | 57.1 | 23 | 60.5 | 43 | 58.9 | 2.32 | 3 | .51 |

| Alcohol | 8 | 22.9 | 5 | 13.2 | 13 | 17.8 | |||

| Marijuana | 3 | 8.6 | 2 | 5.3 | 5 | 6.8 | |||

| Opioids | 4 | 11.4 | 8 | 21.1 | 12 | 16.4 | |||

| On probation or parole | 11 | 31.4 | 16 | 42.1 | 27 | 37.0 | 0.89 | 1 | .35 |

| Referred through criminal just. system | 9 | 25.7 | 11 | 28.9 | 20 | 27.4 | 0.10 | 1 | .76 |

| DSM IV diagnoses, from SCID interviews | |||||||||

| Lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence | 30 | 85.7 | 28 | 73.7 | 58 | 79.4 | 1.62 | 1 | .20 |

| Current alcohol dependence | 15 | 42.9 | 14 | 36.8 | 29 | 39.7 | 0.28 | 1 | .60 |

| Lifetime cocaine abuse or dependence | 28 | 80.0 | 35 | 92.1 | 63 | 86.3 | 2.26 | 1 | .13 |

| Current cocaine dependence | 19 | 54.3 | 26 | 68.4 | 45 | 61.6 | 1.54 | 1 | .22 |

| Lifetime marijuana abuse or dependence | 29 | 82.8 | 30 | 78.9 | 59 | 80.8 | 0.18 | 1 | .67 |

| Current marijuana dependence | 4 | 11.4 | 4 | 10.5 | 8 | 11.0 | 0.02 | 1 | .90 |

| Lifetime opioid abuse or dependence | 13 | 37.2 | 21 | 55.3 | 34 | 46.6 | 2.40 | 1 | .12 |

| Current opioid dependence | 7 | 20.0 | 8 | 21.1 | 15 | 20.5 | 0.01 | 1 | .91 |

| Any lifetime depressive disorder | 17 | 48.6 | 13 | 34.2 | 30 | 41.1 | 1.55 | 1 | .21 |

| Any llfetime anxiety disorder | 9 | 25.7 | 10 | 26.3 | 19 | 26.0 | 0.00 | 1 | .99 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 9 | 25.7 | 6 | 15.8 | 15 | 20.5 | 1.10 | 1 | .29 |

| Continuous variables, mean and sd | F | df | p | ||||||

| Age | 40.6 | 12.0 | 42.5 | 8.4 | 41.6 | 10.2 | 0.68 | 1, 71 | .41 |

| Years primary substance used | 16.2 | 11.3 | 17.1 | 10.8 | 16.7 | 11.0 | 0.12 | 1,71 | .73 |

| Days any substance use/past 28 | 9.6 | 7.8 | 9.9 | 8.4 | 9.7 | 8.1 | 0.03 | 1,71 | .86 |

| Days of alcohol use-past 28 days | 4.8 | 7.2 | 5.5 | 7.7 | 5.2 | 7.5 | 0.14 | 1,71 | .71 |

| Days of cocaine use-past 28 days | 3.8 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 1.90 | 1,71 | .17 |

| Days of marijuana use-past 28 days | 2.7 | 6.6 | 2.4 | 6.1 | 2.5 | 6.3 | 0.05 | 1,71 | .83 |

| Days of opioid use-past 28 days | 1.3 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 4.6 | 1.3 | 4.2 | 0.01 | 1,71 | .94 |

| Mean Shipley | 87.6 | 14.0 | 87.2 | 14.1 | 87.4 | 14.0 | 0.01 | 1,71 | .91 |

Note. CBT4CBT=computer-assisted CBT, TAU=treatment as usual. For substance use variables, participants designated a primary substance (drugs or alcohol) of abuse, but multiple concurrent substance use was common.

Most participants (59%) reported cocaine use as their primary substance use problem, followed by alcohol (18%), opioids (16%) and marijuana (7%), with multiple types of concurrent substance use common (79.5% were users of more than one type of drug or users of both alcohol and drugs). The participants reported they had been using their primary substance for a mean of 17 years, and reported using their primary substance for an average of 10 of the past 28 days. ANOVA and chi-square analyses indicated no significant differences by treatment condition on any of the variables presented in Table 1.

Treatment implementation, retention and data availability by condition

Of the 73 individuals who initiated treatment, 48 (66%) completed the study (22 in CBT4CBT, 26 in TAU, NS). As shown in Table 2, levels of exposure to the standard counseling services offered in the program was also comparable in both groups, with those assigned to CBT4CBT completing a mean of 39 days and those assigned to TAU completing 41 days of the 56 day protocol. Hence, analyses of the primary substance use outcomes were not constrained by differential rates of attrition nor data availability.

Table 2. Retention and primary substance use outcomes by treatment condition.

| CBT4CBT

|

TAU

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | ddf | p | effect size |

|

|

||||||||

| Retention and data availability | ||||||||

| Mean days retained in treatment protocol | 39.4 | 19.1 | 41.4 | 14.8 | 0.04 | 71 | .61 | |

| Individual sessions completed (TAU) | 4.0 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 3.1 | .74 | 69 | .39 | |

| Group sessions completed (TAU) | 7.0 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 2.5 | 0.03 | 69 | .86 | |

| Number of urine specimens submitted | 8.4 | 5.0 | 8.9 | 4.0 | 0.19 | 71 | .66 | |

| Primary outcome indicators | ||||||||

| Number positive urine specimens submitted | 2.2 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 6.18 | 71 | .02 | .59 |

| Percent urine specimens submitted positive | 34.0 | 40.9 | 53.0 | 41.0 | 3.91 | 71 | .05 | .46 |

| Self report: Longest continuous abstinence from all drugs/alcohol | 22.1 | 17.2 | 14.3 | 13.1 | 3.50 | 67 | .07 | .45 |

| Self report: Percent days abstinent from all drugs/alcohol | 80.4 | 25.3 | 75.9 | 22.8 | 0.60 | 69 | .44 | 0.19 |

Note. CBT4CBT n=35, TAU n=38. Days in treatment, range is 1 to 56. For self-reported outcomes, n's do not total 73 because of missing data for some variables.

Of those who initiated the CBT4CBT program, the mean number of computer sessions completed was 4.3 (SD=2.4) of the 6 modules offered. Participants spent an average of 38.3 (SD= 8.2) minutes per session working with each module and tended to complete the modules in the order presented (e.g., 34/35 participants completed Module 1 (patterns of use and functional analysis), 25 completed Module 2 (coping with craving), 20 completed Module 3 (refusing offers), 19 completed Module 4 (problem solving), 18 completed Module 5 (addressing cognitions), and 15 completed Module 6 (decision making). As noted earlier, homework was assigned at the end of each module; participants completed an average of 2.9 homework assignments (SD=2.0). Twenty-six participants completed evaluation of the program where they were asked to rate their level of agreement with a range of statements about the CBT4CBT program using a Likert-type scale with ratings of 1 indicating low satisfaction and 5 indicating high satisfaction. For the 17 items evaluating various aspects of the program (e.g., “The directions were easy to understand”; “The program helped me think about my problems in a new way”), the mean satisfaction rating was 4.3 (SD=0.6).

Effects of treatment on primary substance use outcomes

Participants assigned to CBT4CBT submitted significantly fewer urine specimens that were positive for any type of drug use (2.2 versus 4.3, F=6.18, p=.02), with a moderate effect size (d=.59) and a lower proportion of urines that were positive for any drug (34 versus 53%, F=3.9, p=.05, d=.46). This was most marked for cocaine (28% versus 44% positive specimens). Duration of longest continuous (urine confirmed) period of abstinence during treatment was longer for those assigned to CBT4CBT than TAU (22 versus 17 days). Although this fell just short of statistical significance, the effect size was moderate (d=.45). The difference between groups for self-reported percent days of abstinence for all illicit drugs and alcohol was not statistically significant.

CBT4CBT program utilization and outcome

Consistent with previous support for links between pretreatment substance use severity (46), treatment retention (47), and outcome, we expected strong relationships between these variables and outcome among in this sample, but with treatment involvement more closely tied to outcome in the CBT4CBT condition than in TAU. Table 3 presents simple correlations of the relationships between baseline severity of substance use (frequency of substance use at baseline, years of substance use), treatment involvement (indicated by number of days retained in the treatment program, number of individual and group sessions attended, and homework completion), and treatment outcome (percent of drug-negative urine specimens, self-reported days abstinent, and duration of longest consecutive period of abstinence during treatment. In TAU, the indicators of baseline substance use severity tended to have higher correlations with outcome than the treatment retention indicators, while the reverse held for the CBT4CBT condition, where treatment involvement and completion of homework assignments had higher correlations. Results of structural equation modeling (48) were consistent with this interpretation, with a good fitting model indicating that treatment involvement (r= .77, CR=3.5, p<.001) and completion of homework (r=.85, CR=4.2, p<.001) were strongly related to outcome in CBT4CBT.

Table 3. Simple correlations of indicators of pretreatment substance use severity, treatment involvement and substance use outcome by treatment condition.

| CBT (n=34) | r

|

||||||

| Baseline Drug Use Severity Scores | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 Years primary substance used | - | ||||||

| 2 % day abstinent, 28 days prior to screening | .15 | - | |||||

| Treatment Outcome Indicators | |||||||

| 3 Longest consecutive days of abstinence | .20 | .08 | - | ||||

| 4 Percent days abstinent during treatment | -.01 | .22 | .66** | - | |||

| 5 % urine specimens negative for all drugs | .34* | .10 | .53** | .50** | - | ||

| Treatment Engagement Scores | |||||||

| 6 # of homework assignments completed | .09 | -.03 | .55** | .31 | .43** | - | |

| 7 Total number of sessions attended | .04 | .15 | .67** | .41* | .31 | .74** | - |

| 8 Number of days retained in treatment program | .10 | -.14 | .49** | .26 | .27 | .63** | .54** |

| TAU (n=38) | r

|

||||||

| Baseline Drug Use Severity Scores | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 Years primary substance used | - | ||||||

| 2 % days abstinent, 28 days prior to screening | .23 | - | |||||

| Treatment Outcome Indicators | |||||||

| 3 Longest consecutive days of abstinence | .00 | .27 | - | ||||

| 4 Percent days abstinent during treatment | .20 | .53** | .67** | - | |||

| 5 % urine specimens negative for all drugs | .21 | .43** | .66** | .65** | - | ||

| Treatment Engagement Scores | |||||||

| 6 N/A | |||||||

| 7 Total number of sessions attended | .16 | .03 | .43** | .29 | .21 | - | |

| 8 Number of days retained in treatment program | .09 | -.05 | .34* | .09 | .11 | .44** | |

p<.05.

p<.01

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of a computer-assisted CBT program for reducing drug use, participants using the CBT4CBT program submitted significantly fewer drug-positive urines specimens and tended to have longer periods of abstinence during treatment compared with standard TAU at a community based clinic. This is to our knowledge the first randomized clinical trial evaluating computer-assisted treatment for substance use disorders that reports on biologically-verified drug use outcomes. Thus, the study both adds to the existing positive literature on computer-assisted delivery of CBT for depression and anxiety disorders by extending it to a new and highly challenging population, but also provides strong evidence for the efficacy of computer-assisted training via use of data from urine toxicology screens, rather than self- or therapist report, both of which may be subject to bias. The CBT4CBT program was viewed by participants as highly engaging, was associated with promising outcomes, and potentially addresses a critical issue related to the availability of CBT in clinical practice.

Similarly, this trial is consistent with multiple trials suggesting practice of CBT skills outside of sessions via completion of homework assignments may be an important active ingredient of outcome CBT (34, 36) in that there was a significant positive relationship between number of CBT4CBT homework assignments completed and substance use outcomes. That is, indicators of treatment involvement was strongly related to outcome in the CBT4CBT condition, while in the TAU condition outcome was more strongly related to baseline severity of substance use than level of treatment engagement. Given the link between use of the program and outcome, more frequent access to and use of the CBT4CBT program (e.g., via the internet), should be evaluated as a strategy to enhance the potential benefits of this approach.

Strengths of this trial included randomization of a comparatively large and diverse group of participants in a community clinic, comparable levels of retention and data availability in both conditions, and reliance on independent, biological indicators of outcome. While not addressed in this study, the high level of control over the delivery of specific modules or treatment components (such as homework) in computer-assisted training may permit more refined study of the specific mediators of CBT via future clinical trials where these elements are systematically manipulated with greater precision than is typically possible in clinician-delivered therapies.

This study had several limitations as well. First, it should be noted that the study did not address whether computer assisted delivery of training was comparable or superior to clinician-delivered CBT, nor did it control for the additional time the participants spent working with the computer program in addition to the TAU received. Moreover, use of a TAU comparison condition which was not constrained or controlled had the typical disadvantages of this type of comparison (49), including variability in content and duration. On the other hand, it did constitute an active treatment comparison (50, 51) and therefore provided a rigorous control for evaluating any added benefit conferred by CBT4CBT. Second, in common with most trials involving substance users, attrition was an issue, as approximately 65% of those who initiated their protocol treatment completed it. On the other hand, data availability was comparable for both conditions and the retention rates are comparatively high given the unselected nature of the study population. Moreover, our extensive efforts to reach and collect data from those who dropped out of treatment (52) provided complete data for over 80% of the treatment exposed sample for the full 56 day study period. Third, it should be noted that the analyses evaluating the relationships between baseline substance use severity, treatment involvement, and outcome; are correlational and causality cannot be inferred.

Finally, because CBT has been demonstrated to be effective across several substance use disorders we decided to evaluate CBT4CBT with a heterogeneous sample of outpatients who used multiple substances concurrently. While this provided stronger evidence for the generalizability of the CBT4CBT program, it produced insufficient sample sizes for analyzing different subgroups of patients. In this regard, it should also be noted that our significant urine outcomes are complicated by the fact that some substances are detectable in urine for longer periods (marijuana) than others (cocaine). On the other hand, detecting a significant difference under these circumstances and in a heterogeneous community-based sample provided comparatively strong support for this promising new model. These results should be replicated before CBT4CBT is advocated for broader use in the substance abuse treatment system, and we are currently conducting a larger trial with a more homogeneous cocaine-dependent methadone-maintained sample.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by NIDA grants R37-DA 015969 (KMC), K05-DA00457 (KMC), K05-DA00089 (BJR), and P50-DA09241. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the staff and leadership of Liberation Programs, Inc.

References

- 1.DeRubeis RJ, Crits-Christoph P. Empirically supported individual and group psychological treatments for adult mental disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:37–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth A, Fonagy P. What Works for Whom? A Critical Review of the Psychotherapy Literature. Second. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watkins E, Williams R. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy. 1998;8:165–187. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, Wong MC. Efficacy of relapse prevention: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:563–570. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll KM, Onken LS. Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1452–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, Gordon LT, Wirtz PW, Gawin FH. One year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence: Delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:989–997. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950120061010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift RM, Weiss RD, Williams LD, Zweben A COMBINE Study Research Group. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: The COMBINE Study. JAMA. 2006;2006:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine. Bridging the Gap Between Practice and Research: Forging Partnerships with Community-Based Drug and Alcohol Treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissman MM, Verdeli H, Gameroff MJ, Bledsoe SE, Betts K, Mufson L, Fitterling H, Wickramaratne P. National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:925–934. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLellan AT, Carise D, Kleber HD. Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public's demand for quality care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLellan AT, Meyers K. Contemporary addiction treatment: a review of systems problems for adults and adolescents. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(10):764–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sholomskas D, Syracuse G, Ball SA, Nuro KF, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. We don't train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies for training clinicians in cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):106–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, McCrady BS, Keller DS, Carroll KM. Manual-guided cognitive behavioral therapy training: A promising method for disseminating empirically supported substance abuse treatments to the practice community. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll KM. Internal validity of MET and MI when delivered by community therapists in multisite effectiveness studies. 2007. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aharonovich E, Hasin DS, Brooks AC, Liu X, Bisaga A, Nunes EV. Cognitive deficits predict low treatment retention in cocaine dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81(3):313–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fals-Stewart W, Bates ME. The neuropsychological test performance of drug-abusing patients: An examination of latent cognitive abilities and risk factors. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11:34–45. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklicek I, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop V. Internet-based cognitive-behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:319–328. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenardy JA, Dow MGT, Johnston DW, Newman MG, Thomson A, Taylor CB. A comparison of delivery methods of cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic-disorder: An international multicenter trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(6):1068–1075. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman MG, Kenardy J, Herman S, Taylor CB. Comparison of palmtop-computer assisted brief cognitive-behavioral treatment to cognitive-behavioral treatment for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:178–183. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proudfoot J, Goldberg D, Mann A, Everitt B, Marks I, Gray JA. Computerized, interactive, multimedia cognitive-behavioral program for anxiety and depression in general practice. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:217–227. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702007225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selmi PM, Klein MH, Greist JH, Sorrell SP, Erdman HP. Computer-administered CBT for depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:51–56. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein B, Richards JC, Austin DW. Efficacy of internet therapy for panic disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2006;37:213–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tumur I, Kaltenthaler E, Ferriter M, Beverley C, Parry G. Computerized cognitive behaviour thearpy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2007;76:196–202. doi: 10.1159/000101497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright JH, Wright AS, Albano AM, Basco MR, Goldsmith LJ, Raffield T, Otto MW. Computer-assisted cognitive therapy for depression: maintaining efficacy while reducing therapist time. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1158–64. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCrone P, Knapp M, Proudfoot J, Ryden C, Cavanagh K, Shapiro DA, Ilson S, Gray JA, Goldberg D, Mann A, Marks I, Everitt B, Tylee A. Cost-effectiveness of computerized cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care: Randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;185:55–62. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strecher VJ, Shiffman S, West R. Randomized controlled trial of a Web-based computer-tailored smoking cessation program as a supplement to nicotine patch therapy. Addiction. 2005;100:682–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Japuntich SJ, Zehner ME, Smith SS, Jorenby DE, Valdez JA, Fiore MC, Baker TB, Gustafson DH. Smoking cessation via the internet: A randomized clinical trial of an internet intervention as adjuvant treatment in a smoking cessation intervention. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2006;8(S1):S59–S67. doi: 10.1080/14622200601047900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glenn IM, Dallery J. Effects of internet-based voucher reinforcement and a transdermal nicotine patch on cigarette smoking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:1–13. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hester RK, Squires DD, Delaney HD. The Drinker's Check-up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a stand-alone software program for problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hester RK, Delaney HD. Behavioral self-control program for windows: Results of a controlled clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:686–693. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saitz R, Palfai TP, Freedner N, Winter MR, MacDonald A, Lu J, Ozonoff A, Rosenbloom DL, DeJong W. Screening and brief intervention online for college students: The iHealth study. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2007;42:28–36. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marsch LA, Bickel WK. Efficacy of computer-based HIV/AIDS education for injection drug users. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28:316–327. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA. Practice makes progress: Homework assignments and outcome in the treatment of cocaine dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:749–755. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzalez VM, Schmitz JM, DeLaume KA. The role of homework in cognitive behavioral therapy for cocaine dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:633–637. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazantzis N, Deane FP, Ronan KR. Homework assignments in cognitive and behavioral therapy: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7:189–202. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, DelBoca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994 12:70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carroll KM. A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach: Treating Cocaine Addiction. Rockville, Maryland: NIDA; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carroll KM, Easton CJ, Nich C, Hunkele KA, Neavins TM, Sinha R, Ford HL, Vitolo SA, Doebrick CA, Rounsaville BJ. The use of contingency management and motivational/skills-building therapy to treat young adults with marijuana dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):955–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Shi J, Rounsaville BJ. Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive-behavioral therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients: A randomized placebo controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;64:264–272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Patient. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hersh D, Mulgrew CL, Van Kirk J, Kranzler HR. The validity of self-reported cocaine use in two groups of cocaine abusers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:37–42. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zanis DA, McLellan AT, Randall M. Can you trust patient self-reports of drug use during treatment? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;35:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ. Reliability and validity of 6-month timeline reports of cocaine and heroin use in a methadone population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:843–850. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Metzger DS, Grissom GR, Woody GE, Luborsky L, O'Brien CP. Similarity of outcome predictors across opiate, cocaine, and alcohol treatments: Role of treatment services. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:1141–1158. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simpson DD, Joe GW, Broome KM. A national 5-year follow-up of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:538–544. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bentler PM, Stein JA. Structural equation models in medical research. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1992;1(2):159–181. doi: 10.1177/096228029200100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bickman L. The death of treatment as usual: An excellent first step on a long road. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:195–199. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kazdin AE. Comparative outcome studies of psychotherapy: Methodological issues and strategies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:95–105. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. Bridging the gap between research and practice in substance abuse treatment: A hybrid model linking efficacy and effectiveness research. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:333–339. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nich C, Carroll KM. Intention to treat meets missing data: Implications of alternate strategies for analyzing clinical trials data. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:121–130. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00111-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]