Abstract

Theory and research on antigay aggression has identified different motives that facilitate aggression based on sexual orientation. However, the individual and situational determinants of antigay aggression associated with these motivations have yet to be organized within a single theoretical framework. This limits researchers’ ability to organize existing knowledge, link that knowledge with related aggression theory, and guide the application of new findings. To address these limitations, this article argues for the use of an existing conceptual framework to guide thinking and generate new research in this area of study. Contemporary theories of antigay aggression, and empirical support for these theories, are reviewed and interpreted within the unifying framework of the general aggression model [Anderson, C.A. & Bushman, B.J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 27–51.]. It is concluded that this conceptual framework will facilitate investigation of individual and situational risk factors that may contribute to antigay aggression and guide development of individual-level intervention.

Keywords: Antigay aggression, Aggression, Prejudice, Homosexuality (attitudes toward)

1. Introduction

Antigay violence has been a long-standing social problem for many years. Reports in the early 1990’s indicated that over one third of gay men and lesbians were victims of interpersonal violence and up to 94% experienced some type of victimization related to their sexual orientation (Fassinger, 1991; National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 1990). Consistent with these data, a recent national probability sample found that one in five sexual minority adults were victims of a person or property crime due to their sexual orientation, and approximately 50% have been verbally insulted or abused because of their sexual orientation (Herek, in press-a). Social advocacy groups, however, estimate that countless cases of antigay intimidation, verbal harassment, and physical assault occur every day but go unreported (NCAVP, 2005). Moreover, because numerous states do not have data collection statutes for hate crimes based on sexual orientation, it is likely that documented cases of antigay hate crimes underestimate the frequency of these acts. Indeed, the true prevalence of the problem is largely unknown. Hence, the need to elucidate the processes associated with aggression against this population is clearly important.

Over the past 25 years, a great deal of research has been dedicated toward this aim. Numerous scholars have proposed theories of antigay aggression (Ehrlich, 1990; Herek, 1986, 2000; Franklin, 2000; Kimmel, 1997; Kite & Whitley, 1998) that explore mechanisms by which sociocultural and/or individual factors facilitate antigay violence. To elucidate these processes further, Herek (in press-b) defined sexual stigma as “the negative regard, inferior status, and relative powerlessness that society collectively accords to any nonheterosexual behavior, identity, relationship, or community” (pg. 2) and described how sexual stigma is expressed toward sexual minorities. At the societal level, sexual stigma is referred to as heterosexism. This ideology is manifested in various social customs and institutions (e.g., religion, the legal system) and provides “the rationale and operating instructions for that [antigay] antipathy” (Herek, 2004; pg. 15). At the individual level, the internalization of sexual stigma by heterosexuals is referred to as sexual prejudice (Herek, 2004, in press-b; Pharr, 1988; Neisen, 1990). Importantly, within the context of an individual-level interaction, heterosexism sanctions the individual’s expression of sexual stigma (e.g., individual prejudice, aggression) toward sexual minorities. Thus, whereas sexual prejudice may not always be a primary motivation for antigay aggression, “the importance of cultural heterosexism cannot be underestimated” (Herek, 1992; pg. 164).

Sociocultural explanations of antigay violence also emphasize the development of heterosexual masculinity, especially during adolescence. Numerous scholars posit that men are defined, and learn to define themselves, by what they are (e.g., successful, dominant, tough) as well as what they are not (e.g., feminine, homosexual) (e.g., Brannon, 1976; Deaux & Kite, 1987; Herek, 1986; Kimmel, 1997; Kite, 2001; Pleck, 1981). Accordingly, men may be especially motivated to differentiate between the masculine in-group and the feminine out-group by denigrating and attacking gay men (Hamner, 1992). This conceptualization developed from social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), which stipulates that individuals derive self-esteem by denigrating or attacking out-groups. In support of this view, recent data suggest that the assertion of manhood via ritualized violence toward gays is more prevalent among men who reside in geographic areas with more gender equality (Alden & Parker, 2005). Indeed, in areas with more gender equality, the distinction between masculinity and femininity is less salient. This presumably motivates men to seek more extreme ways of defining themselves as “not feminine,” one of which is attacking the feminine out-group (e.g., gay men). Taken as a whole, sociocultural theories posit that heterosexism and masculine socialization processes converge to promote antigay violence. A fundamental strength of these “macro level” theories is their ability to explain the broader societal context in which antigay violence occurs and, in turn, inform social policy aimed at reducing antigay hate crimes.

However, individual attitudes toward gay men and lesbians vary greatly (Herek, 1992). Accordingly, “micro level” theories attempt to make sense of individual variability by explaining the individual and proximal situational factors that facilitate antigay aggression. Of course, individuals will tend to engage in antigay violence only when the psychological functions served by individual determinants are consistent with broader sociocultural factors (Herek, 1992). Nevertheless, theoretical emphasis on individual and immediate situational determinants of antigay aggression is important because it elucidates specific variables that trigger individual antigay attacks. In addition, exploration of these individual motivations provides valuable information that may guide risk assessment and intervention targeted toward the individual. Despite the existence of substantial theory on antigay violence, the bulk of research in this area examines individual motivations (Alden & Parker, 2005). Hence, in accordance with the need to elucidate the processes associated with antigay aggression, the purpose of the present article is to provide a theoretical framework for examining individual and situational factors that facilitate antigay aggression. As such, significant attention to the “macro level” forces, which explain the facilitative social context for antigay violence, is beyond the scope of this article.

Organizing existing “micro level” research on antigay aggression within a heuristic conceptual framework will afford several advantages. First, numerous motivations for antigay aggression have been advanced and each have garnered some empirical support. By organizing these findings within a single conceptual framework, the fundamental principles and processes that underlie antigay aggression may be better understood. Second, an extensive research literature on human aggression exists that can guide our understanding of antigay aggression. While domain-specific theories of aggression are sometimes drawn upon in the antigay violence literature (e.g., Bandura, 1983; Campbell & Gibbs, 1986; Eron, 1987), these two bodies of research are rarely connected in such a way that generates new lines of empirical inquiry. By more effectively linking current knowledge of theoretically based risk factors for antigay aggression to a well-supported conceptual framework for aggressive behavior, new research and theory on antigay aggression may be stimulated and reciprocally inform existing theories on aggressive behavior in general. Third, despite recent advancements in our understanding of antigay aggression, the application of scientific knowledge to reduce antigay aggression has lagged behind. An individual-focused framework for antigay aggression will serve to guide new research aimed at predicting in whom, and under what circumstances, aggression toward sexual minorities is most likely. In turn, these data will aid the development of prevention or treatment interventions aimed at attenuating antigay aggression at the individual level. Indeed, for risk assessment and preventative interventions to make a significant and lasting impact, they must develop from theoretically based research that makes clear predictions regarding the predisposing factors for antigay aggression.

As such, the principal aim of this article is to use an existing theoretical framework for aggressive behavior, the general aggression model (GAM; Anderson & Bushman, 2002), to explain and guide research on antigay aggression. This endeavor will organize existing research on antigay aggression, link those findings to the broader aggression literature, stimulate new lines of research, and guide the application of antigay aggression research to applied settings. This article begins with a review of the GAM and contemporary theories of antigay aggression. Theoretically based risk factors for antigay aggression are then organized within the context of the GAM. The resulting conceptual framework is then discussed in terms of its ability stimulate future research and guide the application new findings.

2. The general aggression model

2.1. Overview

The GAM (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Anderson & Carnagey, 2004) is an integrated model for the motivation and emission of aggressive behavior. Developed over the past decade, this model incorporates the most prominent theories employed to explain aggressive behavior, including cognitive neoassociation theory (Berkowitz, 1990), social learning theory (Bandura, 1983, 2001), script theory (Huesmann, 1986, 1998), social-information processing theory (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Dodge & Crick, 1990), excitation transfer theory (Zillmann, 1983), and social interaction theory (Tedeschi & Felson, 1994). Thus, the GAM represents a parsimonious conceptualization of aggressive behavior that can explain the variety of motives for aggressive behavior (for an extensive review and empirical support, see Anderson & Bushman, 2002).

2.2. Description of the GAM

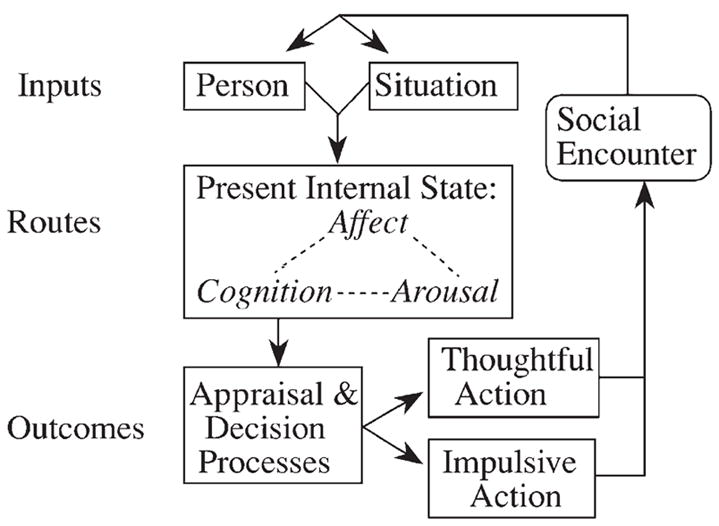

The GAM is composed of input variables, routes, and outcomes (see Fig. 1). At the most fundamental level, the GAM posits that an aggressive response is influenced initially by the interaction of two input variables (i.e., individual differences and situational factors). Depending on the nature of a particular input variable, aggressive behavior may be more (e.g., trait aggressivity, provocation) or less likely (e.g., high empathy, sitting in church). Collectively, these factors increase aggressive behavior through three distinct but interrelated routes (affect, cognition, arousal). Activation of these routes facilitates access to anger-related feelings, aggressive thoughts, and real or perceived physiological arousal, respectively. An associative network purportedly links these three routes, such that initial activation of one pathway (e.g., angry affect) increases the accessibility of other pathways (e.g., hostile cognitions).

Fig. 1.

The general aggression model. Note. From “Human aggression” by C.A. Anderson and B.J. Bushman, 2002, Annual Review of Psychology, 53, p. 34. Copyright 2002 by Annual Reviews. Reprinted with permission.

Upon activation of one or more of these pathways, the individual immediately appraises the situation and other relevant factors prior to emitting a behavioral response. This process, termed immediate appraisal, is automatic and very fast. If time and/or cognitive resources are not available for further processing, immediate appraisal results in an impulsive action that may be aggressive or non-aggressive. If time and cognitive resources are available, the individual evaluates further the results of the primary appraisal, as well as other relevant factors, in a more thoughtful and deliberate manner. This process, termed reappraisal, is conscious, slow, and leads to a thoughtful action that may be aggressive or non-aggressive. The likelihood of an aggressive response is largely dictated by the content of the appraisal as influenced by activation of the various pathways. However, reappraisal also involves consideration of pertinent features of the situation, potential causes for the event, and the meaning of the potential outcomes. Thus, to the extent that reappraisal heightens awareness of provocative cues or positive outcomes of aggression, the likelihood of aggression increases.

Ultimately, these complex appraisal processes dictate an individual’s final choice of action (i.e., the outcome). The subsequent social interaction then influences the input variables in the short-term (e.g., immediate situational factors) and long-term (e.g., reinforcing personality or attitudinal variables associated with conflict resolution). For example, an aggressive response may elicit higher levels of provocation from the target, which in turn will facilitate the emission of additional aggressive responses by the individual. Likewise, an aggressive response may be reinforced by the target “backing down” and, as a result, reinforce the perpetrator’s belief that aggression is an appropriate tactic in some, or all, situations.

3. Contemporary theories of antigay aggression

3.1. Overview

Numerous scholars have attempted to explain the motives that impel a person to harm others based on their sexual orientation. The most prominent theories are reviewed below. At the foundation of most theories in this area is the widely supported assertion that sexual prejudice is a key determinant of antigay aggression. As defined by Herek (2000, p. 19), sexual prejudice is a dispositional characteristic that incorporates “all negative attitudes based on sexual orientation, whether the target is homosexual, bisexual, or heterosexual.” Moreover, Herek (2000) asserts that sexual prejudice is “almost always directed at people who engage in homosexual behavior or label themselves gay, lesbian, or bisexual” (p. 9). Indeed, as reviewed below, extant literature clearly demonstrates a positive relation between sexual prejudice and the perpetration of antigay aggression.

3.2. Enforcement of the male gender role

Herek (1984, 1986, 1988) posits that one function of sexual prejudice is to make clear distinctions between male and female gender roles. In short, sexual prejudice serves a social-expressive function that “defines group boundaries (with gay men on the outside and the self on the inside)” (Herek, 1986; pg. 573). In support of this theory, studies indicate that male sexual prejudice is strongly associated with adherence to traditional gender roles (Ehrlich, 1990; Kilianski, 2003; Parrott, Adams, & Zeichner, 2002; Polimeni, Hardie, & Buzwell, 2000; Sinn, 1997; Whitley, 2001). Thus, the purported function of antigay aggression, which may be viewed as a behavioral expression of sexual prejudice, is also to enforce a rigid gender role dichotomy.

At a more fundamental level, the enforcement of male gender norms affirms the perpetrator’s masculine identity (Franklin, 1998; Hamner, 1992; Kimmel, 1997; Kite & Whitley, 1998). Indeed, pertinent theory posits that masculinity is defined by that which is not feminine (Brannon, 1976; Deaux & Kite, 1987; Herek, 1986; Kimmel, 1997; Kite, 2001; Pleck, 1981). As such, the most critical component in one’s developing masculine identity is arguably “the renunciation of the feminine” (Kimmel, 1997; pg. 22). Inasmuch as male–male intimate or sexual behavior is viewed as an extreme gender role violation, gay men are especially high risk targets for male assailants who seek to affirm their masculine, or antifeminine, identity.

Of course, endorsing traditional beliefs of masculinity and femininity does not directly translate into antigay aggression. Rather, men who frequently question their masculinity or have it questioned by other men are presumably more likely to exaggerate stereotypical masculine behaviors (e.g., aggression toward gay men) in order to maintain gender dichotomy and reaffirm their heterosexual masculinity. This proposed mechanism applies to individually perpetrated antigay assaults, and is especially pertinent to group perpetrated antigay assaults (see below).

3.3. Thrill seeking

According to Franklin (1998, 2000), antigay assailants who are not driven by sexual prejudice are, instead, motivated by social dynamics. This latter group includes perpetrators who are motivated by thrill seeking. Typically, thrill seeking behavior involves a desire to have fun, seek excitement, and experience pleasure from engaging in certain risky activities. However, thrill seeking antigay assailants, who tend to be male or female adolescents, satisfy these desires specifically through aggression toward gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender individuals. They see sexual minorities as “easy targets” for victimization, attack them seemingly out of boredom, minimize the harm they cause, and view their acts as funny or amusing.

It is worth noting that thrill seeking assailants do not target sexual minorities exclusively. Rather, antigay aggression perpetrated by these individuals is part of a general pattern of violence, delinquency, and criminal behavior directed toward other minorities and society in general (Franklin, 2000; Levin & McDevitt, 1993). Franklin (1998, 2002) has argued that a common theme for these perpetrators is their perception of being economically disadvantaged and socially disempowered. From a social identity perspective (Hamner, 1992), individuals lower in the social system may only derive a positive evaluation of their in-group by attacking out-groups held in even lower social regard (e.g., gay men, lesbians). Thus, these real or perceived social class divisions presumably elicit negative sentiment toward sexual minorities, who are perceived to possess undeserved privileges despite their sexual deviancy.

3.4. Defense motivation

Psychoanalytic theory posits that antigay aggression results from the use of reaction formation to cope with one’s unconscious anxiety about being gay and/or experiencing homosexual urges (West, 1977). Data in support of this viewpoint is limited. Most notably, Adams, Wright, and Lohr (1996) assessed sexual arousal patterns in heterosexual men who viewed male–female, female–female, and male–male erotica. Not surprisingly, all participants demonstrated significant sexual arousal to male–female and female–female erotica. However, sexually prejudiced men, but not their non-prejudiced counterparts, demonstrated significant sexual arousal to male–male erotica. This finding provided tentative empirical evidence that a man’s experience of presumably unwanted sexual arousal to other men may motivate sexual prejudice and antigay aggression due to his fear of being gay.

Nevertheless, this narrow etiological view of antigay aggression has been largely dismissed by contemporary research and theory. For example, Herek (1986) posited that antigay aggression serves a broader ego-defensive function that reduces anxiety from psychological conflicts associated with gender and sexuality.1 Broadly defined, this conceptualization of defensive antigay aggression reflects the perpetrator’s “insecurities about personal adequacy and meeting gender-role demands” (pg. 566) rather than his unconscious fear of being gay. Franklin (2000, 2002) distinguished between two types of defensive antigay aggression. Consistent with the work of Herek (1986), the first type, termed psychological defensiveness, stems from internal psychological conflicts. In the second type, antigay aggression protects the assailant from the perceived threat posed by presumably “sexually predatory” sexual minorities. Data support both of these explanations, especially with respect to the link between psychological defensiveness and physical aggression (Franklin, 2000).

3.5. Group dynamics

While antigay aggression may be perpetrated by a lone individual, it is quite common that assaults are committed simultaneously by small groups or by one individual in front of peers (Weissman, 1992). In fact, nearly 30% of all documented victims of antigay attacks reported the involvement of multiple perpetrators (e.g., NCAVP, 2003, 2005). Among a sample of young male college students, however, nearly 75% of individuals who reported aggression toward a gay individual reported doing so while in the context of a group (Franklin, 2000). These data clearly indicate that the group context is especially likely to elicit antigay aggression.

In an analysis of hate crime perpetrators, McDevitt, Levin, and Bennett (2002) noted that “most hate crime offenders are young males for whom respect from their peers is incredibly important” (pg. 313). Franklin (1998) similarly posited that the primary motivation for antigay group assailants is to “prove both toughness and heterosexuality to friends” (pg. 12). This explanation essentially extends the “reaffirmation of masculinity” conceptualization to the group context. Indeed, group perpetrated aggression toward gay men — much like group rape of women — represents an extreme social display of masculinity and public adherence to traditional male gender norms (Franklin, 2004). Though dysfunctional, these exaggerated masculine displays clearly demonstrate one’s own heterosexuality and masculinity to other men. As Franklin (1998) concluded, the group views gay men as “a dramatic prop, a vehicle for a ritualized conquest through which assailants demonstrated their commitment to heterosexual masculinity” (pg. 12–13). As such, the theorized role of peer group dynamics in the perpetration of antigay aggression suggests that the group context, especially the male group context, may serve as a potent situational risk factor for antigay aggression.

4. The GAM as a conceptual framework for antigay aggression

The reviewed literature indicates that antigay aggression is facilitated primarily by gender role enforcement, reaffirmation of masculinity, thrill seeking, defensive functions, and group dynamics. It is worth noting that these theories are not mutually exclusive. For example, one individual may attack a gay man purely “for the fun of it” (i.e., thrill seeking), whereas another individual’s behavior may be motivated by thrill seeking as well as a demonstration of masculinity to his peer group (i.e., group dynamics, reaffirmation of masculinity). This notion of multiple determinants for antigay violence has been echoed by other theorists (Franklin, 1998; Herek, 1992)2. This fact highlights the utility of a parsimonious conceptual framework for aggression toward gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Indeed, by accounting for multiple personological and situational input variables, the GAM provides a heuristic framework that accounts for multiple predictors of and pathways to antigay aggression.

I will now review literature in support of these theories using the GAM as a guiding conceptual framework. First, a selective review of pertinent individual difference and situational factors will be presented to illustrate their independent and joint effects on antigay aggression and affective, cognitive, and physiological routes to aggressive behavior. Second, a general discussion of these findings will be presented to elucidate the role of appraisal processes that ultimately lead to an aggressive response.

4.1. Individual difference risk factors

4.1.1. Gender and age

Survey data indicate that 80% of antigay assailants are male and tend to be in their late teens or early twenties (NCAVP, 2005). Consistent with these data, heterosexual men, relative to heterosexual women, report higher levels of sexual prejudice toward gay men than toward lesbians (Gentry, 1987; Herek, 1988; Kite, 1994; Lim, 2002, Whitley, 1987). Not surprisingly, 60–75% of antigay hate crimes are directed toward gay or transgender men (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2006).

In accordance with the observed gender differences in antigay assailants, it is well-established that men are more directly aggressive than women (Bettencourt & Miller, 1996). However, it is worth noting that aggression may be expressed in a variety of ways (Parrott & Giancola, 2007), and pertinent literature indicates that women tend to express aggression in an indirect, relative to a direct, manner (Richardson & Green, 1999). In fact, some studies suggest that women are actually more likely than men to use indirect aggressive tactics (Bjorkqvist, Osterman, & Kaukianen, 1992). In light of these findings, future research must be sensitive to the various ways that aggression toward sexual minorities may be expressed. By preventing a myopic focus on direct aggression, discovery of the pathways to female-perpetrated antigay aggression will be more likely.

It is worth noting that a hypermasculine gender role may be more predictive of aggression than one’s actual gender (Richardson & Hammock, 2007). Perhaps for this reason, the most prominent theories of antigay aggression are based upon masculine ideology and, as such, only purport to explain male-perpetrated aggression. With these theories as the only framework upon which to guide subsequent empirical inquiry, the majority of research in this area has relied largely upon male samples. As a result, pathways to female-perpetrated antigay aggression have not been investigated. The application of the GAM might address this limitation and stimulate new research and theory on factors that facilitate antigay aggression in women. For example, women’s endorsement of masculine attributes (e.g., tough, strong) may represent an important predictor of female-perpetrated antigay aggression. Overall, the need for research on female antigay perpetrators has been echoed in previous reviews (Kite & Whitley, 2003).

4.1.2. Summary

Consistent with gender differences in non-biased aggression (Bettencourt & Miller, 1996), research shows that young men are the most typical antigay assailants. This finding suggests that age and gender moderate the expression of antigay aggression. Accordingly, most theory and research on antigay aggression involves male perpetrators. Thus, research with female assailants is clearly needed. However, this finding also begs the question of whether older adults continue to engage in antigay aggression, albeit using tactics that are not direct. Indeed, a middle-aged man may not attack a gay man as part of a “street gang,” but he may indirectly harm a gay man by spreading rumors at work. The aggression literature also indicates that women tend to utilize indirect, rather than direct, aggressive tactics. This suggests that many female antigay assailants may go unnoticed because their tactics are circuitous. As such, future studies in this area will benefit from considering the many ways that aggression may be expressed, rather than relying solely on the assessment of direct, physical antigay aggression. Finally, research indicates that gender role adherence is more predictive of antigay aggression than one’s gender. Thus, assessment of women’s adherence to masculine norms is one necessary step to elucidate pathways to female-perpetrated antigay aggression.

4.1.3. Sexual prejudice

Although popular opinion and victim accounts suggest that sexual prejudice causes antigay aggression, only two laboratory-based investigations have examined this link (Bernat, Calhoun, Adams, & Zeichner, 2001; Parrott & Zeichner, 2005). Under the guise of a competitive reaction time task, participants administered various intensities of electric shocks to an opponent who they believed to be a heterosexual or gay male. Immediately prior to this task, all participants viewed depictions of male gender role violations (i.e., male–male erotica). Results indicated that sexually prejudiced men exposed to violations of the traditional male gender role displayed higher levels of aggressive behavior toward the gay, relative to the heterosexual, male opponent. A link between sexual prejudice and antigay aggression was not observed following exposure to male–female erotica (Parrott & Zeichner, 2005). Consistent with these findings, survey-based studies have demonstrated that sexual prejudice is positively associated with self-reported past aggressive behavior toward gay men (Franklin, 2000; Patel, Long, McCammon, & Wuensch, 1995; Roderick, McCammon, Long, & Allred, 1998).

Pertinent research also indicates that sexual prejudice and exposure to male gender role violations interactively activate an affective route to aggression. Several studies have shown that when sexually prejudiced men are exposed to gay men, they report higher levels of anger and anxiety relative to non-sexually prejudiced men (Bernat et al., 2001; Ernulf & Innala, 1987; Parrott & Zeichner, 2005; Parrott, Zeichner, & Hoover, 2006; Van de Ven, Bornholt, & Bailey, 1996). In addition, recent studies using startle eye blink methodology indicate a clear link between sexual prejudice and negative affect (i.e., high startle magnitude) after viewing pictures of nude men or nude gay male couples (Mahaffey, Bryan, & Hutchison, 2005a,b).

Considerably fewer studies have evaluated the effects of sexual prejudice, and its interaction with other individual and situational factors, on cognitive- and arousal-based routes to aggression. Parrott et al. (2006) found that sexually prejudiced men demonstrated biases in anger-related cognitive processing following exposure to male gender role violations. Research also suggests that individuals who endorse high levels of both sexual prejudice and anger proneness are more likely to report hostile attitudes toward a gay victim of a hate crime (Rayburn & Davison, 2002). Unfortunately, no study to date has evaluated the effects of sexual prejudice on real or perceived physiological arousal.

4.1.4. Summary

The literature reviewed in this section indicates that sexual prejudice is a risk factor for antigay aggression. Especially in conjunction with exposure to sexual violations of the male gender role, sexual prejudice facilitates antigay aggression and is associated with two hypothesized routes to aggression. Importantly, recent evidence indicated that anger in response to gay men mediated the relation between sexual prejudice and self-reported past antigay aggression (Parrott & Peterson, in press). These data are consistent with the GAM. In addition, inasmuch as sexual prejudice functions to make clear distinctions between male and female gender roles, these findings are consistent with contemporary theories that highlight gender role enforcement and reaffirmation of masculinity as motivators of antigay aggression.

Nevertheless, more research is clearly needed in this area. First, there is no research that examines the interactive effect of sexual prejudice and other potential risk factors on real or perceived physiological arousal. Second, with only two published studies to support the link between sexual prejudice and hostile cognition (Parrott et al., 2006; Rayburn & Davison, 2002), more research is needed to replicate and extend this line of inquiry. Third, as Herek (2004) notes, “sexual prejudice will not always predict specific [antigay] behaviors” (pg. 19). Rather, other factors are important as well, such as characteristics of the immediate situation and the individual. As such, future research must strive to identify those variables that increase, or decrease, the likelihood that sexual prejudice will lead to antigay aggression. Investigation of the function(s) served by an individual’s prejudice (e.g., social expressive, ego defense) may illuminate pertinent situational triggers. Relatedly, it will likely be important to investigate how the internalization of cultural variables might facilitate sexually prejudiced antigay aggression. For example, there is a “commonly held belief that [sexual prejudice] is more prevalent in the black community than in society at large” (Brandt, 1999; pp. 8–9), and recent data support this view (Lewis, 2003). Thus, African-American men may be especially likely to report high levels of sexual prejudice which, in turn, may facilitate antigay aggression, especially toward African-American gay men.

4.1.5. Traditional gender role beliefs

As previously noted, studies indicate that male sexual prejudice is strongly associated with adherence to traditional male gender roles and hypermasculinity (e.g., Kilianski, 2003; Polimeni et al., 2000). Moreover, Herek (1986, 1988) proposes that antigay aggression stems from the perpetrator’s attempt to affirm his masculinity through the enforcement of these gender norms. As such, it makes intuitive sense that rigid adherence to traditional male gender roles will potentiate antigay aggression.

Despite this clear theoretical connection, very little research has been conducted in this area. Recent studies have linked traditional masculine gender role beliefs to engagement in “antigay behaviors” (Patel et al., 1995; Whitley, 2001). However, “antigay behaviors” included both aggressive acts (e.g., “I have gotten into a physical fight with a gay person because I thought he or she had been making moves on me”) and avoidant acts (e.g., “I have changed seat locations because I suspected the person sitting next to me to be gay”). This lack of specificity obscures the link, if one exists, between traditional beliefs of the male gender role and antigay aggression. This limitation was addressed by recent survey and laboratory-based research. In an anonymous survey of nearly 500 young adults, Franklin (2000) found that a substantial proportion of antigay assailants perceived their actions to be enforcing gender norms. Consistent with this finding, Parrott & Zeichner (in press) conducted a laboratory-based study that examined the effects of extreme masculine gender role beliefs (i.e., hypermasculinity) and exposure to male gender role violations on antigay anger and aggression. Similar to prior research (e.g., Parrott & Zeichner, 2005), male–female and male–male erotica were used to manipulate male participants’ exposure to male gender role violations. Results indicated that among men who viewed male–male erotica, hypermasculinity predicted increases in anger and higher levels of physical aggression toward a gay, relative to a heterosexual, man. In contrast, among men who viewed male–female erotica, hypermasculinity did not predict increases in anger and was not differentially associated aggression toward the heterosexual or gay opponent.

4.1.6. Summary

Pertinent literature suggests that traditional male gender role beliefs represent an individual difference risk factor for antigay aggression. These beliefs are positively associated with anger and aggression toward gay men, especially following exposure to male gender role violations. These findings adhere well to the GAM. Unfortunately, research has not evaluated the effects of male gender role beliefs, or its interaction with other personological or situational variables, on hostile cognition or arousal. In addition, the relation between men and women’s beliefs about the female gender role and aggression toward female sexual minorities has not been investigated. These gaps in the literature appear especially ripe for investigation.

Nevertheless, the reviewed literature is consistent with contemporary theories of antigay aggression (e.g., Herek, 1986; Kite & Whitley, 1998). Specifically, because men who endorse traditional male gender role beliefs also demonstrate extreme adherence to masculine ideology, they are threatened when confronted by violations of the traditional male gender role. Consequently, these men are at increased risk to respond with stereotypical masculine emotions (e.g., anger) and behaviors (e.g., aggression). This expression of aggression purportedly functions to enforce traditional gender norms as well as reaffirm one’s masculine identity.

4.1.7. Masculine gender role stress

The stress associated with gender role identification varies for each sex. For example, research indicates that men who violate traditional masculine gender role norms face greater social condemnation than women who violate traditional female norms (Pleck, 1981). Perhaps due to this fact, O’Neil (1982) posited that, to the extent a heterosexual man fears the appearance of violating these norms (i.e., of appearing “feminine”), he will display exaggerated, and sometimes dysfunctional, characteristics of the male role. Indeed, one unifying theme of male gender role conflict is men’s fear of appearing feminine (David & Brannon, 1976; O’Neil, 1981), especially in the presence of other men (Kimmel, 1997). This theme is supported by recent research (Wilkinson, 2004) and is consistent with both the proposed defensive–expressive and social-expressive functions of antigay aggression (Herek, 1986). Specifically, antigay aggression directly allays one’s fear of being perceived as feminine, gay, or otherwise non-masculine and simultaneously reaffirms masculine identity to oneself and others.

In response to this literature, Eisler and Skidmore (1987) introduced the construct of masculine gender role stress. In contrast to masculinity, which reflects some traits that are socially desirable for most men, masculine gender role stress refers to a man’s “appraisal of specific cognitions, behaviors, or situations as stressful and undesirable” (Eisler, Skidmore, & Ward, 1988; p. 135). Accordingly, men who report high masculine gender role stress display increased anger “when a situation is viewed as requiring ‘unmanly’ or feminine behavior” (pg. 125). In short, these men tend to experience negative emotions (e.g., anger) in situations where they have their masculinity threatened.

Masculine gender role stress appears especially likely to facilitate antigay aggression when an individual is confronted with a situational masculinity threat. Although no study to date has directly evaluated this hypothesis, indirect evidence is found in related literatures. For example, research indicates that men who report high levels of masculine gender role stress are more likely to use aggressive tactics in situations where a female threatens their masculinity (Eisler, Franchina, Moore, Honeycutt, & Rhatigan, 2000; Franchina, Eisler, & Moore, 2001). In addition, masculine gender role stress is positively associated with the activation of routes to aggression. For example, research suggests that men who endorse high levels of masculine gender role stress report higher levels of anger, more negative attributions, and heightened cardiovascular reactivity in response to situational threats of traditional masculinity (Cosenzo, Franchina, Eisler, & Krebs, 2004; Eisler et al., 2000; Franchina et al., 2001; Lash, Eisler, & Schulman, 1990; Moore & Stuart, 2004). Independent of the situation, research has also shown a positive relation between masculine gender role stress and anger (Eisler et al., 1988).

4.1.8. Summary

The literature reviewed in this section clearly identifies masculine gender role stress as a risk factor for aggressive behavior. In accordance with the GAM, masculine gender role stress, particularly in conjunction with situational threats to one’s masculinity (e.g., peer “gay baiting”), is especially likely to activate affective, cognitive, and arousal routes to aggressive behavior. These data are consistent with current theories that emphasize reaffirmation of masculinity and peer dynamics as motives for antigay aggression. Specifically, when men with high levels of gender role stress are in a situation that threatens their masculinity (especially in the presence of other men), they will react with heightened levels of anger, anger-related cognitions, and physiological arousal. According to the GAM, activation of these pathways will significantly increase the likelihood of an aggressive response, particularly toward traditionally ‘non-masculine’ targets (e.g., gay men). Indeed, the targeted expression of stereotypical masculine behavior (i.e., aggression) toward gay men may function to demonstrate masculinity to oneself or others. Research is sorely needed to test these hypotheses.

4.1.9. Right wing authoritarianism

Right wing authoritarianism is a personality trait comprised of three related clusters, including submission to authority figures, acceptance of aggression perceived to be sanctioned by authority figures, and extreme adherence to social conventions (Altemeyer, 1996). From a behavioral standpoint, individuals who are high on this trait tend to be submissive to established authority figures, display aggression when they believe authorities approve such behavior, and engage in activities that uphold traditional social norms. Not surprisingly, over three decades of research indicate that right wing authoritarians are more likely to hold prejudiced attitudes toward out-groups (Altemeyer, 1981, 1986, 1996).

Although Altemeyer (1996) has referred to right wing authoritarians as “equal opportunity bigots” (pp. 26), research indicates that authoritarianism is particularly associated with negative attitudes toward groups (e.g., sexual minorities) condemned by authority figures (e.g., Herek, 1988; Whitley, 1999). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis reported a strong positive correlation between right wing authoritarianism and antigay attitudes (Whitley & Lee, 2000). While a portion of this relation is attributable to gender role ideology, recent data indicate that other factors account for approximately 90% of the variance (Wilkinson, 2004). Wilkinson (2004) explained this finding by concluding that right wing authoritarians may perceive sexual minorities as part of a “hegemonic hierarchy (‘them not us’) that exists without any need for any additional information regarding gender roles or typicality” (pg. 129).

4.1.10. Summary

While a great deal of research has evaluated the link between right wing authoritarianism and sexual prejudice, no studies have examined its effects on antigay aggression or hypothesized routes to aggression. This is an especially fertile area for future investigation that may be guided by the GAM. For example, research indicates that authoritarian aggression is positively associated with traditional beliefs regarding male, but not female, gender roles (Duncan, Peterson, & Winter, 1997). Inasmuch as right wing authoritarians perceive the male gender role to be more rigid than the female gender role (Michaels, 1996), their maintenance of hegemonic boundaries may facilitate more powerful emotional, cognitive, and physiological reactions to male, relative to female, sexual minorities. This hypothesis is also consistent with theories that highlight the enforcement of gender roles as a primary motive for antigay aggression (Franklin, 1998; Kite & Whitley, 1998). Similarly, research is needed to elucidate other situational forces that motivate the right wing authoritarian toward antigay attacks. By definition, authoritarians submit to the will of established authority figures. Given this strong disposition, right wing authoritarians may be more inclined to engage in behaviors sanctioned by their immediate group cohort. Thus, as a situational risk factor, a group context that endorses or engages in an antigay attack may propel the right wing authoritarian toward antigay aggression.

4.2. Situational risk factors

4.2.1. Exposure to gender role violations

Exposure to sexual violations of the male gender role (e.g., gay men kissing) may motivate perpetrators to attack gay men in an effort to enforce these gender norms (Herek, 1986, 1988). Consistent with these data, research clearly indicates that sexually prejudiced men who are exposed to sexual violations of the traditional male gender role experience increases in anger and negative affect (Bernat et al., 2001; Parrott & Zeichner, 2005), display biases in processing of anger-related information (Parrott et al., 2006), and behave more aggressively toward a gay, relative to a heterosexual, man (Bernat et al., 2001; Parrott & Zeichner, 2005). Moreover, traditional male gender role beliefs interact similarly with exposure to male–male gender role violations to facilitate anger and antigay aggression (Parrott & Zeichner, in press). This collective evidence indicates that exposure to male–male gender role violations is an important situational risk factor for antigay aggression.

It is worth noting that, after controlling for personological variables (e.g., sexual prejudice), exposure to extreme male gender role violations (e.g., male–male erotica) is positively associated with self-reported feelings of anger (Parrott & Zeichner, 2005) and physiological measures of negative affect (Mahaffey et al., 2005a). In contrast, research does not support an independent effect on hostile cognition, arousal, or aggression. Indeed, exposure to male gender role violations only activated hostile cognition (Parrott et al., 2006) and aggressive behavior (Parrott & Zeichner, 2005) upon interaction with other variables (e.g., sexual prejudice, hypermasculinity). These findings provide strong evidence for the interaction of situational and individual difference variables in the prediction of antigay aggression.

4.2.2. Summary

In accordance with the GAM, exposure to sexual violations of the male gender role is a situational facilitator of antigay aggression in some men. The reviewed literature is also consistent with theories of antigay aggression that highlight the enforcement of traditional gender roles. Inasmuch as antigay aggression serves a social-expressive function that defines group boundaries (Herek, 1986), exposure to extreme violations of one’s rigid gender role dichotomy is likely to incite anger and facilitate antigay aggression.

A limitation of this research is that existing laboratory findings possess low external validity due to the fact that these studies used male–male erotica as examples of male gender role violations. Realistically, sexually prejudiced men are unlikely to put themselves in situations where they would be exposed to sexually graphic male–male behavior. Thus, several important questions remain unanswered. First, it is unclear whether these findings stem from the essence of male–male sexual behavior or the graphic nature of the stimuli. Future research that employs more accessible depictions of sexual male–male gender role violations (e.g., two men kissing) or interactions between research participants and a self-identified gay confederate is needed to tease apart this confound. Second, the extent to which male gender role violations must possess a sexual component to facilitate sexually prejudiced anger and antigay aggression is not known. Clearly, exposure to graphic depictions of male–male sexual activity is one such situational trigger. However, violations of the traditional male gender role might also include a man doing housework or a man who throws a football in an “effeminate” manner. To answer this question, a series of studies may be envisioned in which participants are randomly assigned to view sexual male–male gender role violations (e.g., male–male intimate relationship behavior or erotica) or a non-sexual male gender role violation (e.g., a man doing housework). Emotional, cognitive, physiological and, ultimately, biased aggressive responses could then be assessed. Indeed, the GAM provides a useful framework from which to guide important new research in this area.

4.2.3. Alcohol and substance intoxication

Anderson and Bushman (2002) contend that alcohol and substance intoxication serve as indirect situational facilitators of aggression, especially among people who possess aggression-related traits and/or are exposed to other aggression-promoting situational cues. This conceptualization is in accordance with other theories of alcohol- and substance-related aggression (e.g., Chermack & Giancola, 1997; Graham, Wells, & West, 1997; Taylor & Chermack, 1993). As such, the effects of individual (e.g., sexual prejudice) and situational (e.g., exposure to male gender role violations) variables that predict antigay aggression should be exacerbated by acute intoxication from alcohol or other substances known to facilitate aggression (e.g., cocaine). Unfortunately, not one study has directly tested this hypothesis. Only one published study has examined the link between alcohol intoxication and the expression of any type of prejudice (Reeves & Nagoshi, 1993), though the inebriate’s expression of aggression was not assessed.

The lack of research in this area is surprising for several reasons. First, in a survey of hate crime perpetrators, 58% reported a history of substance abuse and approximately 33% were intoxicated at the time of the offense (Dunbar, 2003). Second, anecdotal reports gathered from victims indicate that many acts of aggression against gay men are reportedly committed under the influence of alcohol or in/around bars (Human Rights Campaign, 2000). Consistent with these findings, Franklin (2000) found that antigay assailants consumed alcohol more frequently than non-assailants. Finally, like research on alcohol-related aggression, research on prejudice and discriminatory behavior has a long history in the psychological literature. The fact that these two literatures have yet to be meaningfully linked limits theoretical development and prohibits the application of any synergistic scientific advancement.

There is clearly a need for research in this area. In conducting this research, it will be important for researchers to consider pertinent theory, consistent with the GAM, which explains how alcohol and other substances facilitate aggression. Specifically, theorists posit that a key mechanism of alcohol-related aggression is inhibition conflict (Steele & Josephs, 1990), which occurs in situations where simultaneous pressures to engage (i.e., instigatory cues) or not to engage (i.e., inhibitory cues) in aggressive action are present. Steele and colleagues (Steele & Josephs, 1990; Steele & Southwick, 1985) postulate that alcohol intoxication facilitates aggression in these situations by narrowing the inebriate’s attention to these instigatory cues. Recent laboratory evidence supports this view (Giancola & Corman, 2007). This conceptualization may be extended to other substances to the extent that a drug’s intoxicating effects have a narrowing effect on attention.

Accordingly, in the context of their justification–suppression model of prejudice, Crandall and Eshleman (2003) argue that the alcohol intoxication will facilitate the behavioral expression of prejudice, “but only to the extent that those prejudices are suppressed” (p. 425)3. When the simultaneous pressures of instigatory cues (e.g., a situation that fosters the expression of those prejudiced attitudes) and inhibitory cues (e.g., one’s disposition toward suppressing prejudices) are salient, alcohol is most likely to increase prejudicial aggression. Stated differently, to the extent that an individual freely expresses his or her prejudice (i.e., no inhibition conflict), alcohol is not hypothesized to exacerbate behavioral expression of those prejudices.

4.2.4. Summary

The effects of acute alcohol intoxication, as well as intoxication resulting from other substances (e.g., cocaine), on antigay aggression clearly merit investigation. Future research in this area may benefit by considering several theoretically derived lines of inquiry. First, prior theory and research indicate that alcohol intoxication exacerbates the influence of aggression-promoting personality traits on the experience of anger (Eckhardt, 2007; Parrott, Zeichner, & Stephens, 2003), aggressive thoughts (Eckhardt, 2007), and aggressive behavior (e.g., Pernanen, 1991). However, it is not known whether alcohol or other substances exert the same moderating effect on traits (e.g., sexual prejudice, traditional male gender role beliefs) that facilitate antigay aggression. Second, future studies might examine the joint effects of alcohol/substance use and other situational risk factors on antigay aggression as well as negative affect, hostile cognition, and arousal. For example, alcohol may serve to exacerbate pre-existing tendencies to become angry after exposure to male–male gender role violations. Third, pertinent theory (Crandall & Eshleman, 2003; Steele & Josephs, 1990) suggests that alcohol will only facilitate the behavioral expression of prejudice among individuals who attempt to suppress their prejudice. Given the existence of an instrument that assesses individual differences in the suppression of antigay prejudice (Plant & Devine, 1998), this area is also ripe for future research.

These and other lines of research involving alcohol and substance use will inform current theories of antigay aggression. Inasmuch as intoxication unleashes pre-existing behavioral tendencies, research might illuminate further those theories that point to gender role enforcement, reaffirmation of masculinity, defensive functions, and/or thrill seeking as motivations for antigay aggression. Notably, recent data indicate that alcohol facilitates social bonding in small groups (Kirchner, Sayette, Cohn, Moreland, & Levine, 2006). This finding has interesting implications for the influence of group dynamics on antigay aggression. Specifically, to the extent that alcohol-induced social bonding amplifies the influence of group members on one another, peer pressure may be an especially powerful force that motivates individual displays of masculinity among intoxicated individuals (e.g., alcohol-related antigay aggression).

4.3. Appraisal processes

The literature reviewed thus far highlights distal predictors of aggressive behavior. However, the GAM posits that more proximal appraisal processes ultimately determine behavioral outcomes (e.g., aggression). Immediate appraisals involve automatic information processing that lead to impulsive action. Reappaisals involve controlled information processing that lead to thoughtful action. While these processes may be distinguished on a conceptual level, both automatic and controlled information processing likely underlie most aggressive acts (Bushman & Anderson, 2001). Nevertheless, it is useful to illustrate how appraisal processes may differentially influence the likelihood of antigay aggression.

Many acts of antigay aggression clearly stem from reappraisal processes. That is, when deciding between an aggressive or non-aggressive response, perpetrators engage in very deliberate, conscious thought. They consider their beliefs about gender roles, beliefs about their masculine identity, and scripts or schemas that may guide their interactions with gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender individuals. In addition, they likely consider positive outcome expectancies for action. Indeed, there is little doubt that anticipated outcomes from antigay aggression (e.g., restoration of masculinity, acceptance of peer group, getting a “thrill”) are especially important to perpetrators. As Anderson and Bushman (2002) note, reappraisal processes may even increase the level of anger “as the damage to one’s social image becomes more apparent” (pg. 41). For example, as a perpetrator continues to think about his masculinity being threatened, his likelihood of emitting an aggressive response increases. The hypothesized role of reappraisal processes is supported by case reports of antigay aggression. Specifically, antigay assaults typically share the common feature of a perpetrator or perpetrators who consciously planned or deliberated prior to the attack (NCAVP, 2005). These qualitative data suggest that controlled information process underlie many acts of antigay aggression. Unfortunately, no direct test of this hypothesis has been conducted.

According to the GAM, a history of reinforcement for antigay aggression will also increase the likelihood of future aggression toward sexual minorities. Research on the effects of video game violence provides an interesting insight into this hypothesis. Carnagey and Anderson (2005) found that video games which reward aggressive behavior increase hostile thoughts that, in turn, facilitate aggression. As applied to antigay aggression, the reviewed literature suggests that perpetrators’ aggression can be positively reinforced (e.g., reaffirmation of one’s masculinity) or negatively reinforced (e.g., decreases in state gender role stress). To the extent that such reinforcement occurs, antigay cognitions will become chronically accessible and antigay aggression will be more likely. It is worth noting that peer groups are an especially likely source of these types of reinforcement (Franklin, 1998; McDevitt et al., 2002). In the long term, repeated reinforcement for antigay aggression, as well as repeated activation of antigay cognitions, will lead to the development of aggressive scripts and schemas. As part of the reappraisal process, these easily accessible and well-rehearsed knowledge structures will serve to facilitate the expression of antigay aggression. With repeated use, however, these cognitive processes will become automatized. As these knowledge structures are accessed with less effort, they may guide behavior at the level of immediate appraisal.

The implication of this development is significant. Anderson and Carnagey (2004) state that “a person who repeatedly ‘learns’ through experience or through cultural teachings that a particular type of person is a ‘threat’ can automatically perceive almost any action by a member of that group as dangerous” which can “easily lead to a ‘shoot first, ask questions later’ mentality” (pp. 173). As applied to antigay violence, heterosexism and masculine socialization processes systematically “teach” a person that sexual minorities are a threat. Consequently, automatic use of these knowledge structures may contribute to the formation of attitudes (e.g., sexual prejudice, perception of gays as an inferior social group) that also increase one’s likelihood of antigay aggression. It is possible that these perpetrators, who access antigay aggressive scripts with such ease, will be driven to antigay aggression by the slightest situational cue or whim, will engage in these acts with the most recurrence, and will be least responsive to intervention. Collectively, these processes may represent an important intersection between “macro level” and “micro level” determinants of antigay violence.

5. Methodological considerations for future research

Thus far, I have reviewed empirical research on numerous risk factors for antigay aggression and demonstrated how these variables may be adapted into the theoretical framework of the GAM. As a result, numerous theoretical limitations of past research have been identified and suggestions for future research have been advanced. However, examination of this literature also highlights methodological limitations of previous research that merit attention.

It is clear that most research on antigay aggression has relied on self-report measures to assess pertinent individual difference risk factors (e.g., sexual prejudice), mediating variables (e.g., anger), and outcome variables (e.g., retrospective reports of antigay aggression). While this methodological approach has its advantages, self-reports of presumably undesirable behaviors (e.g., aggression) may be limited by response biases. Thus, the use of more objective assessment tools would effectively complement prior research. For example, to the extent that assessment of sexual prejudice may be biased by socially desirable responding, use of implicit measures, such as the implicit association test (Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998), seems warranted. Likewise, more objective assessment of anger, hostile cognition, or arousal may be achieved via facial analysis (Ekman & Friesen, 1975) or electromyography (EMG), psychophysiological measures of arousal (e.g., galvanic skin response), or well-established cognitive tasks (e.g., Stroop task), respectively. Finally, only recently has research in this area employed laboratory methods to assess antigay aggression. While some have criticized the external validity of laboratory aggression paradigms (Tedeschi & Quigley, 1996, 2000), numerous studies have demonstrated their validity (reviewed in Anderson & Bushman, 1997; Berkowitz, 1989; Giancola & Chermack, 1998). Regardless of the perceived artificiality of these tasks, laboratory aggression paradigms effectively evaluate theoretical mechanisms that are believed to operate in more naturalistic aggressive interactions (Anderson & Bushman, 1997).

It is also worth noting that most research on antigay aggression relies on undergraduate samples of young men. Although young men are most often perpetrators of antigay aggression, results from prior research need to be extended to broader adult samples beyond male college students. Specifically, large population-based studies are required to determine whether hypothesized and established effects in the present review apply to adult males in general. If results of these studies are consistent with prior work, then the prevalence of these effects would provide compelling support for their application in developing community interventions to reduce antigay violence in the United States.

6. Implications for prevention and treatment

Conceptualizing antigay aggression through the lens of the GAM will inform applied work to reduce antigay aggression. Unfortunately, a comprehensive discussion of potential applied considerations not only goes beyond the scope of the present article, but also goes beyond existing literature in this area. Indeed, it is not prudent to outline specific recommendations for individual intervention without a substantial research foundation. As such, it is proposed that the next, and most important, step in this area is to provide a framework to guide the basic research that is needed to better understand antigay aggression. After these efforts establish incontrovertible pathways to antigay aggression, researchers in this area will be more effective in developing community and individual prevention and treatment programs.

Nevertheless, some applications merit preliminary consideration. At the input level, it seems reasonable to suggest that reducing individual sexual prejudice would decrease one’s risk of antigay aggression. Certainly, interventions that target heterosexism and masculine socialization processes should have a “trickle down” effect to the individual. However, several strategies that directly target the individual are also possible. First, clinicians can identify how sexual prejudice and antigay aggression reinforce the individual’s behavior (e.g., reaffirmation of masculinity, reducing anxiety). In turn, techniques that reduce these reinforcing effects or allow the individual to obtain that reinforcement in another way might be used (Herek, 1992). For example, interventions could be designed that promote self-esteem in groups at high risk for antigay violence (e.g., adolescent males) (Hamner, 1992). Second, a consistent finding in the antigay aggression literature is that individuals who report low levels of sexual prejudice also report knowing someone who is gay (Herek & Capitanio, 1996). Thus, interventions to reduce sexual prejudice may seek to increase individuals’ positive interactions with or challenge stereotypes of gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender persons. Finally, individuals’ beliefs about themselves (e.g., socially disempowered) or the world (e.g., sexual minorities are a low status social group) may be targeted with schema change techniques (Dobson & Hamilton, 2003).

Interventions that target mediational mechanisms (i.e., anger, cognition, arousal) presumed to facilitate antigay aggression may also be effective. High arousal and dysregulated emotional states characterized by poor anger regulation and high sensation seeking can be improved by utilizing empirically-validated anger management therapies that include relaxation training as well as cognitive and behavioral skill enhancement (Deffenbacher, Dahlen, Lynch, Morris, & Gowensmith, 2000; Deffenbacher, Oetting, & DiGuiseppe, 2002). Furthermore, hostile cognitions can be modified and/or managed with well-established cognitive techniques, including thought stopping, problem-solving skills training, self-reinforcement, and urge control. More broadly, well-established skills taught in cognitive–behavioral therapy may also prove beneficial, such as identifying and challenging irrational thoughts. Such techniques may also effectively modify appraisal and reappraisal processes. Finally, inasmuch as contact with a member of an out-group (e.g., a gay man) elicits anger among heterosexual persons, certain types of intergroup contact might attenuate negative affective reactions and, in turn, reduce the likelihood of antigay aggression. Consistent with this view, research suggests that intergroup contact that includes equal status between the groups, a norm supporting positive relations, and cooperative (relative to competitive) interactions reduces anxiety and increases positive affect in response to out-group members (Dovidio et al., 2004; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2000).

Another avenue worthy of investigation involves the enhancement of self-regulatory strength. Research indicates that interactions with out-groups deplete self-regulatory strength which, in turn, exhausts limited capacity resources needed to regulate behavior (Richeson & Shelton, 2003). Interestingly, research also suggests that self-regulatory exercise can reduce individuals’ susceptibility to self-regulatory depletion and, presumably, to behavioral dysregulation (Gailliot, Plant, Butz, & Baumeister, 2007). Though tentative, these findings have promising implications for the reduction of antigay aggression motivated by sexual prejudice or other dispositional characteristics. Indeed, “self-regulation can be the trump card of personality” (Baumeister, Gailliot, Dewall, & Oaten, 2006; pg. 1796).

7. Summary and conclusions

Over the past 25 years, scholars have advanced numerous explanations for antigay aggression. Recently, empirical data supporting some of these theories has begun to emerge. For example, research clearly shows that young men are the most typical antigay assailants, though there is reason to believe that female-perpetrated antigay aggression may go unnoticed due to their tendency to use circuitous aggressive tactics. Numerous laboratory and survey studies have also demonstrated that sexual prejudice is positively associated with antigay aggression as well as two hypothesized routes (i.e., anger, hostile cognition) to aggression. Similarly, research has linked traditional beliefs about the male gender role to the perpetration of antigay aggression, especially following exposure to violations of the male gender role. Data indicate that masculine gender role stress is an individual difference risk factor for aggressive behavior and may also predict antigay aggression. Pertinent theory suggests that antigay aggression perpetrated by thrill seeking assailants may be perpetuated by sensation seeking tendencies and/or real or perceived social disempowerment. Future research is needed to examine the effects of these variables on antigay, and other bias-motivated, aggression. Right wing authoritarianism is associated with sexual prejudice and, purportedly, with antigay aggression. However, research is also needed to evaluate this proposed link.

Extant literature also points to situational factors that may elicit antigay aggression. Although exposure to sexual violations of the male gender role independently elicits anger in men, this risk factor exerts its most powerful effect on antigay aggression upon interaction with other pertinent individual risk factors (e.g., sexual prejudice). The group context, especially peer pressure within the group, also appears to be an especially powerful facilitator of antigay violence. Finally, research suggests that alcohol and substance use is linked to antigay assaults. Although no studies have explicated this presumed relation, pertinent theories of alcohol- and substance-related aggression and the expression of prejudice exist to guide future research.

By integrating these findings within the framework of the GAM, numerous theoretically derived avenues for future research may be envisioned. For example, studies are needed that examine the interactive effects of identified personological (e.g., sexual prejudice, perceived social disempowerment) and situational (e.g., exposure to violations of the male gender role, peer pressure) variables on hypothesized routes to antigay aggression. Most notably, input variables that elicit real or perceived physiological arousal and hostile cognition require substantial investigation. Inasmuch as researchers seek to evaluate situational effects of gender role violations on antigay aggression, it is necessary for future studies to utilize more socially visible and realistic displays of male–male or female–female interactions. The effects of alcohol, and other aggression-promoting drugs, on antigay aggression have eluded scientific attention to date. Future research is needed to test pertinent theory in this area. These are but a few of the many research questions that are yet unanswered.

In conclusion, the foregoing review has argued that the general aggression model will facilitate investigation of “micro level” individual and situational risk factors that may contribute to antigay aggression. I have outlined important implications of conceptualizing the antigay violence literature in this way. First, as new findings on antigay aggression begin to accumulate, they can be organized and interpreted through the lens of a heuristic theory of aggressive behavior. This will permit integration of a breadth of research on aggressive behavior, inclusive of antigay and other bias-motivated aggression. Second, expanding the theoretical “playing field” will likely stimulate new and exciting research on antigay aggression. As previously noted, the cognitive and physiological reactions of antigay offenders have eluded significant investigation. Indeed, conceptualizing antigay aggression within the heuristic framework of the GAM can stimulate new research in this area. Third, as knowledge regarding pertinent risk factors and pathways to antigay aggression accumulates, the general aggression model will provide a framework to guide the development of individual-level intervention. This endeavor will serve the ultimate goal of aggression research, which is to reduce violence in our society.

Footnotes

The development of this article was supported in part by grant R01-AA-015445 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. I would like to thank John L. Peterson for his helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

In addition to the defensive-expressive function of sexual prejudice, Herek (1986) also proposed a social-expressive function (reviewed above) and a value-expressive function. He posited that sexual prejudice, and antigay aggression, does not serve all three functions for all people. Rather, sexual prejudice may serve a defensive function for one person, while serving a social-expressive function for another.

In Franklin’s (1998) discussion of multiple determinism, she posits that social, cultural, psychological, and situational factors converge to facilitate antigay violence. As discussed previously, a review of “macro level” social or cultural determinants is beyond the scope of this article. As such, only individual psychological and situational factors will be discussed.

Crandall and Eshleman (2003) do not make specific predictions regarding the effects of other drugs on the expression of prejudice. Nonetheless, it is assumed that their hypotheses may be expanded to include other substances that have a narrowing effect on attention.

References

- Adams HE, Wright LW, Lohr BA. Is homophobia associated with homosexual arousal? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:440–445. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alden HL, Parker KF. Gender role ideology, homophobia, and hate crime: Linking attitudes to macro-level anti-gay and lesbian hate crimes. Deviant Behavior. 2005;26:321–343. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer B. Right wing authoritarianism. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer B. Enemies of freedom: Understanding right wing authoritarianism. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer B. The authoritarian specter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. External validity of “trivial” experiments: The case of laboratory aggression. Review of General Psychology. 1997;1:19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:27–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Carnagey NL. Violent evil and the general aggression model. In: Miller AG, editor. The social psychology of good and evil. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 168–192. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Psychological mechanisms of aggression. In: Geen R, Donnerstein E, editors. Aggression: Theoretical and empirical reviews. Theoretical and methodological issues. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Gailliot M, DeWall CN, Oaten M. Self-regulation and personality: How interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1773–1801. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. Laboratory experiments in the study of aggression. In: Archer J, Browne K, editors. Human aggression: Naturalistic approaches. New York, NY: Routledge; 1989. pp. 42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. On the formation and regulation of anger and aggression: A cognitive neoassociationistic analysis. American Psychologist. 1990;45:494–503. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat JA, Calhoun KS, Adams HE, Zeichner A. Homophobia and physical aggression toward homosexual and heterosexual individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:179–187. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt BA, Miller N. Gender differences in aggression as a function of provocation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:422–447. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkqvist K, Osterman K, Kaukiainen A. The development of direct and indirect aggressive strategies in males and females. In: Niemela P, Bjorkqvist K, editors. Of mice and women: Aspects of female aggression. San Diego: Academic Press; 1992. pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt E. Dangerous liaisons: Blacks, gays, and the struggle for equality. New York: New Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brannon R. The male sex role: Our culture’s blueprint for manhood, what it’s done for us lately. In: David D, Brannon R, editors. The forty-nine percent majority: The male sex role. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1976. pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Anderson CA. Is it time to pull the plug on the hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychological Review. 2001;108:273–279. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A, Gibbs JJ, editors. Violent transactions: The limits of personality. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Carnagey NL, Anderson CA. The effects of reward and punishment in violent video games on aggressive affect, cognition, and behavior. Psychological Science. 2005;16:882–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chermack S, Giancola P. The relationship between alcohol and aggression: An integrated biopsychosocial approach. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;6:621–649. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosenzo KA, Franchina JJ, Eisler RM, Krebs D. Effects of masculine gender-relevant task instructions on men’s cardiovascular reactivity and mental arithmetic performance. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2004;5:103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Crandall CS, Eshleman A. A justification–suppression model of the expression and experience of prejudice. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:414–446. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information processing mechanisms in children’s adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- David D, Brannon R. The forty-nine percent majority: The male sex role. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Deaux K, Kite ME. Thinking about gender. In: Hess BB, Ferree MM, editors. Analyzing gender: A handbook of social science research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. pp. 92–117. [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher J, Dahlen E, Lynch R, Morris C, Gowensmith W. An application of Beck’s cognitive therapy to general anger reduction. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:689–697. [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher J, Oetting E, DiGuiseppe R. Principles of empirically supported interventions applied to anger management. Counseling Psychologist. 2002;30:262–280. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson KS, Hamilton KE. Cognitive restructuring: Behavioral tests of negative cognitions. In: O’Donohue W, Fisher JE, Hayes SC, editors. Cognitive behavior therapy: Applying empirically supported techniques in your practice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. pp. 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Crick NR. Social information-processing bases of aggressive behavior in children. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1990;16:8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, Stewart TL, Esses VM, ten Vergert M, Godson G. From intervention to outcome: Processes in the reduction of bias. In: Stephan WG, Vogt WP, editors. Education programs for improving intergroup relations: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Teachers College Press; 2004. pp. 243–265. [Google Scholar]