Abstract

Urinary exosomes are excreted from all nephron segments and are a rich source of kidney injury biomarkers. Because exosomes contain intracellular proteins, we asked if transcription factors (TF) can be measured in urinary exosomes. We collected urine from two acute kidney injury (AKI) models (cisplatin or ischemia/reperfusion) and two podocyte injury models (puromycin-treated rats and podocin/Vpr transgenic mice). Human urine was obtained from patients with AKI, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and matched controls. After isolating urine exosomes by differential centrifugation, activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) and Wilms Tumor 1 (WT-1) were detected by western blot. ATF3 was continuously detected in urine exosomes 2–24 hr after ischemia/reperfusion and in a biphasic pattern after cisplatin. In both models, urinary ATF3 was detected earlier than serum creatinine. Urinary ATF3 was detected in AKI patients but not in normal subjects or patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Urinary WT-1 was detected in animal models before significant glomerular sclerosis. Urinary WT-1 was detected in 9/10 FSGS patients, but not in 8 controls. Transcription factors can be detected in urine exosomes, but not in whole urine. Urinary ATF3 may be a novel renal tubular cell injury biomarker for detecting early AKI, whereas urinary WT-1 may detect early podocyte injury. Urinary exosomal TFs represent a new class of biomarkers for acute and chronic renal diseases and may offer insight into cellular regulatory pathways.

Keywords: exosomes, transcription factor, ATF3, AKI, WT-1, FSGS, CKD

INTRODUCTION

Much effort is being expended in discovering non-invasive biomarkers for acute and chronic kidney injury1, 2 Several promising biomarker candidates are being evaluated for their effectiveness for early detection, disease classification, predicting severity/outcome, and/or predicting response to treatment2–22. Urinary exosomes are a rich source of biomarkers because they are released from every segment of the nephron, including podocytes23. Exosomes are right-side out vesicles that originate from endocytic vesicles that fuse with multivesicular bodies (MVB). Invagination of the MVB membrane can form internal vesicles within the MVB that have a right-side out orientation. When a MVB fuses with the plasma membrane, the internal vesicles enter the extracellular space as exosomes24. Whereas membrane proteins such as transporters and ion channels are expected to be highly enriched in exosomes23, 25, exosomes can also contain cytosolic proteins23, 26. Transcription factors (TF) are found in the cytosol as well as the nucleus, and should theoretically be present in exosomes. However, TFs have not been detected in exosomes using proteomics discovery techniques, perhaps because TFs are usually expressed at such low levels inside of cells.

TFs can be activated by developmental, physiological, pathological and therapeutic stimuli. Because they orchestrate the mobilization of several genes, TFs often play central roles in the initiation and development of many kidney diseases. Therefore, measuring TFs might be more informative than measuring downstream proteins. In microarray experiments mRNA levels of some TFs were markedly induced during the early phase of AKI27–32. TFs also play important roles in the development of glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis33, 34. Changes in mRNA levels do not always correspond to changes in protein levels for a given gene29, 35; therefore, if candidate genes are identified by microarray experiments, the genes are best evaluated at the protein level before entering a biomarker development pipeline1.

TFs are expressed at low levels inside cells, and are difficult to detect outside cells; indeed, transcription factor proteins have not been detected in urine. The purpose of the present study was to determine if TFs can be detected in urine by examining the exosomal fraction and if TFs can serve as novel urinary biomarkers for acute and chronic renal injury. We chose two transcription factors previously identified by microarray studies: ATF3 for AKI29, 31, 36 and WT-1 for FSGS37. We examined temporal expression of ATF3 in ischemia/reperfusion and cisplatin animal models of AKI and a small number of human samples. We evaluated the temporal expression of WT-1, which is often used as a molecular marker for podocytes34, 38, in urinary exosomes from puromycin-induced FSGS in rats and doxycycline-induced collapsing glomerulopathy (CG) in podocin/Vpr transgenic mice, and FSGS patients. This novel discovery strategy of using the unique properties of urinary exosomes to sample the intracellular and/or exported compartment may allow new insights to be gained about cellular regulatory pathways without an invasive renal biopsy.

RESULTS

Temporal urinary excretion of exosomal ATF3 in animal models of AKI

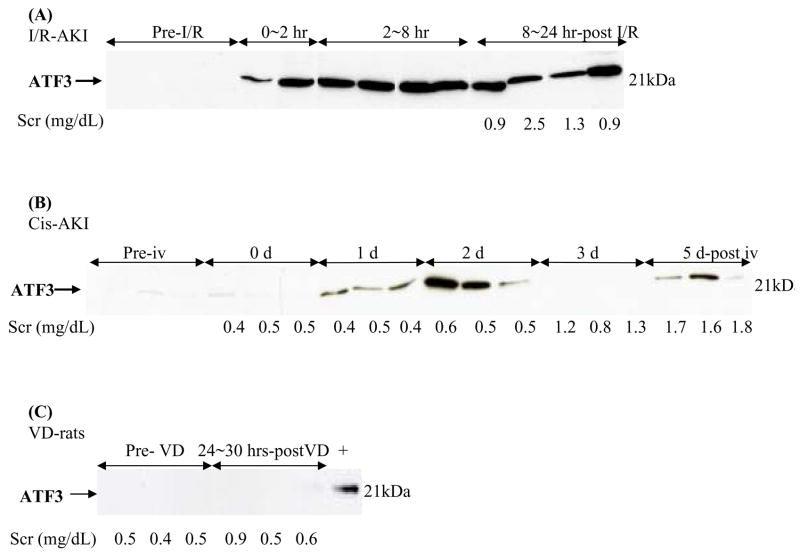

Induction of AKI in cisplatin and I/R models was confirmed by increases in serum creatinine (SCr, Fig. 1) and histological evidence of renal tubule damage (data not shown)14.

Figure 1. Time course of excretion of urinary exosomal ATF3 in ischemic and nephrotoxic AKI rat models.

Urinary exosomal ATF3 from individual rats analyzed by western blotting. (A) I/R-induced AKI rats after 35 mins of bilateral ischemia and reperfusion, (B) Cisplatin-induced AKI rats, (C) volume depleted rats. +, ATF3 positive control.

Urinary exosomal ATF3 increased significantly as early as 0–2 hr after 35 min of ischemia and reperfusion, then remained elevated in the 2–8 hr and the 8–24 hr collection periods (Fig. 1A). Urinary ATF3 also increased 24 hr after cisplatin injection, peaked at day 2 after cisplatin injection, decreased to a very low level at day 3, and reappeared at day 5 (Fig. 1B). Urinary ATF3 was detected 2 days before the SCr increase and tubular damage (Fig. 1B and 2). The biphasic pattern was confirmed in two independent experiments although ATF3 was detected weakly in some animals at day 3 after cisplatin injection (data not shown). In contrast, ATF3 was not detected in urine exosomes from either normal or volume depleted rats (Fig. 1C), or puromycin-treated rats, an animal model of FSGS (data not shown).

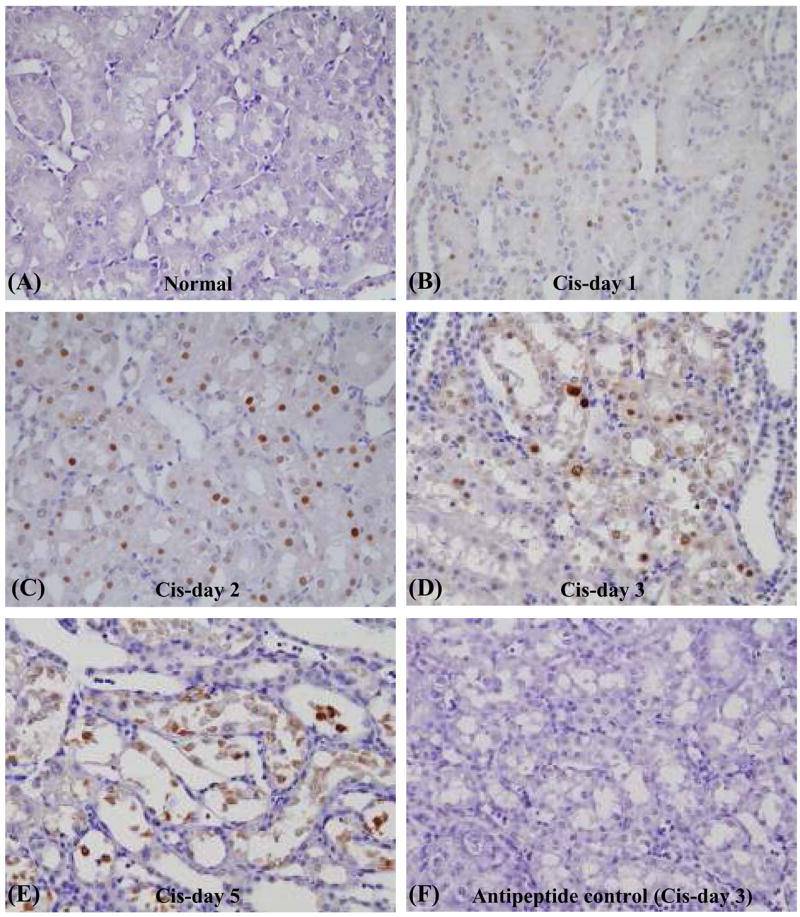

Figure 2. Time course of immunohistochemical staining of ATF3 in rats with cisplatin-induced.

AKI. Immunostaining of renal ATF3 in outer stripe of outer medulla before (A) and at day 1 (B), day 2 (C), day 3 (D), and day 5 (E) after cisplatin injection in rats. Negative control: day 3 after cisplatin (peak of renal ATF3) primary antibody was incubated with the corresponding peptide prior to immunostaining (F).

Renal expression of ATF3 after cisplatin-induced AKI

To determine whether the changes in urinary exosomal ATF3 content reflected histological changes and/or changing content of ATF3 in kidneys, we examined renal ATF3 protein expression by immunohistochemistry. ATF3 was not detected by immunohistochemical examination in normal kidney but was increased in the nuclei of tubule epithelial cells in the outer stripe of the outer medulla (OSOM) from day 1 to day 5 after cisplatin (Fig. 2). ATF3 staining increased significantly in normal appearing proximal tubular cells on day 1 (Fig. 2B) and peaked on day 2 when renal function and histology remained normal (Fig. 2C). On day 3, when tubular injury became evident, ATF3 was still detected in nuclei of cells attached to the tubule basement membrane, but faint staining could be detected in the cytoplasm as well. (Fig. 2D). As cells detached from the basement membrane on day 5 after cisplatin, positive staining was detected in nuclei of detached cells, but there was also staining in cellular debris (Fig. 2E). The primary anti-peptide antibody was incubated with the immunogenic peptide, to confirm the absence of non-specific staining (Fig. 2F). Urinary ATF3 paralleled the initial rise in renal ATF3 expression, but preceded the increase in serum creatinine and histological changes, by two days (Fig. 1 and 2).

Urinary exosomal ATF3 in patients with AKI and CKD

Spot urine samples were collected from two healthy volunteers and four ICU patients with AKI, including urine collections at two different time points during the course of AKI in two patients (Table 1), and four patients with CKD (supplemental table 1). We isolated exosomes from these urine samples and examined the abundance of ATF3 normalized by urine creatinine. Urinary exosomal ATF3 increased in the early phase of AKI based on the time course of serum creatinine in ICU patients (Fig. 3). In one patient, urinary ATF3 was already increased when SCr started to go up and decreased to undetectable level when SCr reached very high values (Fig. 3A middle panel). This is similar to the cisplatin-induced AKI animal (Fig. 1B). In another patient, increased urinary ATF3 returned to the undetectable level during the recovery phase of AKI (Fig. 3 right panel). In contrast, urinary ATF3 was not increased in CKD patients (supplemental figure 1 and table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of ICU patients with AKI

| patients | Age/gender | Primary diagnosis | APACHE II score | AKI | Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) | Blood Urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | Urine output (ml/day) | Furo-Semide (mg) | Blood culture | SIRS | sepsis | WBC | temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 51/M | Pneumonia | 24 | Yes | 3.8 | 68 | 1555 | yes | Positive | yes | yes | 11 | 36.7 |

| A2 | 71/M | Abdominal pain, mesenteric ischemia | 16 | Yes | 2.1 | 73 | 1961 | No | Negative | Yes | Yes | 10.45 | 36.7 |

| A3 | 26/M | Epileptics | |||||||||||

| Time point-1 | 25 | Yes | 2.5 | 20 | 1520 | No | Negative | No | No | 11.66 | 37.3 | ||

| Time point-2 (6 days later) | 25 | Yes | 7.1 | 120 | 1515 | No | Positive | Yes | Yes | 9.7 | 39.4 | ||

| A4 | 73/M | UTI, Hyponephrosis, Urosepsis | 11 | Yes | 3.5 | 110 | 765 | Negative | No | No | 6.72 | 36.7 | |

| Time point-1 | 9 | Recovered | 1.2 | 31 | 3550 | Negative | No | No | 11.16 | 37.8 | |||

| Time point-1 (12 days later) |

Figure 3. Urinary exosomal ATF3 in human subjects.

Comparison of ATF3 in spot urine samples from two healthy volunteers and two AKI patients (left panel); urine samples at two time points (rising and peak SCr) from a third AKI patient (middle panel); and urine samples at two time points (high SCr and during recovery) from a fourth AKI patient (right panel).

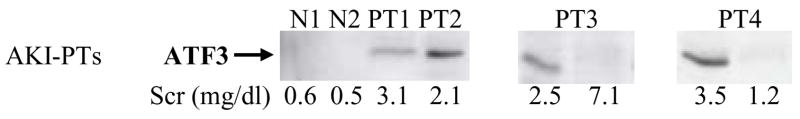

Urinary excretion of exosomal WT-1 in two podocyte injury animal models

We examined the time course of urinary exosomal WT-1 excretion relative to nephrosis, which was established (Table 2) within 14 days in puromycin-treated rats (a FSGS model) and within 28 days in doxycycline-treated podocin/Vpr transgenic mice (a collapsing glomerulopathy model39, 40). Urinary exosomal WT-1 was not detected in either normal rats or non-induced podocin/Vpr transgenic mice (Fig. 4A and 4B). WT-1 started to increase very early (day 1 and day 3) after puromycin injection, before albuminuria was detectable, was significantly increased at 7 days, and remained elevated at 14 days in PAN-treated rats (Fig. 4A). In podocin/Vpr transgenic mice, urinary WT-1 also was detected at 7 days and continued to increase progressively for 28 days of doxycycline administration (Fig. 4B) corresponding to the increasing level of albuminuria (Fig. 4C). Urinary WT-1 was detected earlier than detection of albuminuria in FSGS rats and as early as albuminuria in CG mice; although WT-1 and albumin were detectable at 7 days in these mice, albumin was not statistically significant from control (Fig. 4C).

Table-2.

serologic data of FSGS animal models

| animal models

|

puromycin-treated rats

|

DOX-treated podocin/Vpr transgenic mice

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | pre-iv | 2w-post iv | Untreated | 4w-post DOX |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 4.52 ± 0.09 | 3.05 ± 0.07* | 5.24 ± 0.29 | 3.83 ± 0.23* |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 7.24 ± 0.15 | 5.15 ± 0.18* | 3.56 ± 0.21 | 2.53 ± 0.15* |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 11.3 ± 0.99 | 14.8 ± 0.55 | 15.1 ± 1.23 | 63 ± 1.41* |

| creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.4 ± 0.04 | 0.4 ± 0.05 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.36 ± 0.05* |

p<0.05

Figure 4. Time course of excretion of urinary exosomal WT-1 analyzed by western blotting in animal models of podocyte injury.

(A) FSGS rats: urinary exosomal WT-1 after puromycin aminonucleoside injection to rats. The number under each blot is semi-quantative proteinuria by Chemstrip. Blots are shown from two separate experiments. (B) CG mice: time course of urinary WT-1 in uninephrectomy and doxycyclin-induced CG in podocin/Vpr transgenic mice. (C) Albuminuria measured by albumin ELISA from podocin/Vpr transgenic mice in a parallel experiment. * p < 0.05 by ANOVA

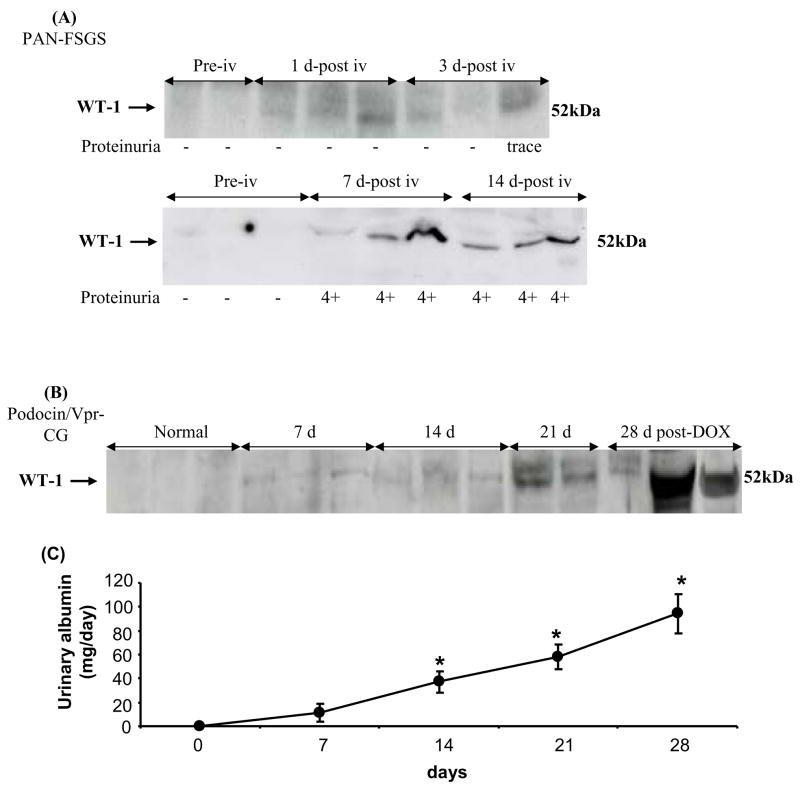

Urinary exosomal WT-1 was detected before histologic abnormalities were observed (Fig. 4 and 5). Normal glomerular morphology (Fig. 5A) was observed in over 75% of the glomeruli at 14 days after PAN. Only 25% of glomeruli showed expansion of mesangial matrix (Fig. 5B, arrow 1) and very few glomeruli had typical sclerosis such as podocytes detached from the glomerular capillary (Fig. 5B, arrow 2) and adhesions between the glomerulus and Bowman’s capsule (Fig. 5B, arrow 3). Histology observed after 14 days of Vpr induction by doxycycline (data not shown) was indistinguishable from the contralateral normal kidney harvested during uninephroctomy (Fig. 5C). In contrast, severe glomerular damage could be detected after 28 days of doxycycline induction. We saw increased mesangial matrix in half of the glomeruli (Fig. 5D, arrow 1), protein casts in cortical tubules (Fig. 5D, #), and glomerular crescents in Bowman’s capsule (Fig. 5D, *).

Figure 5. Histology of the kidney sections stained with periodic acid-Schiff reagent in the cortex in animal models of podocyte injury.

Morphologic changes in glomeruli from rats before (A) and 14 days (B) after PAN injection; from podocin/Vpr transgenic mice before (C) and (D) after uninephrectomy and 28 days doxycycline administration. Expansion of mesangial matrix (arrow 1) was observed in almost half of glomeruli; podocyte detachment (arrow 2) and glomerular capillary adherence to Bowman’s capsule (arrow 3) were observed in very few glomeruli at 14 days in PAN-treated rats (B). Expansion of mesangial matrix (arrow 1), pseudocrescent (*) was observed in a few glomeruli at 28 days in podocin/Vpr transgenic mice (D). Tubular casts are marked with #.

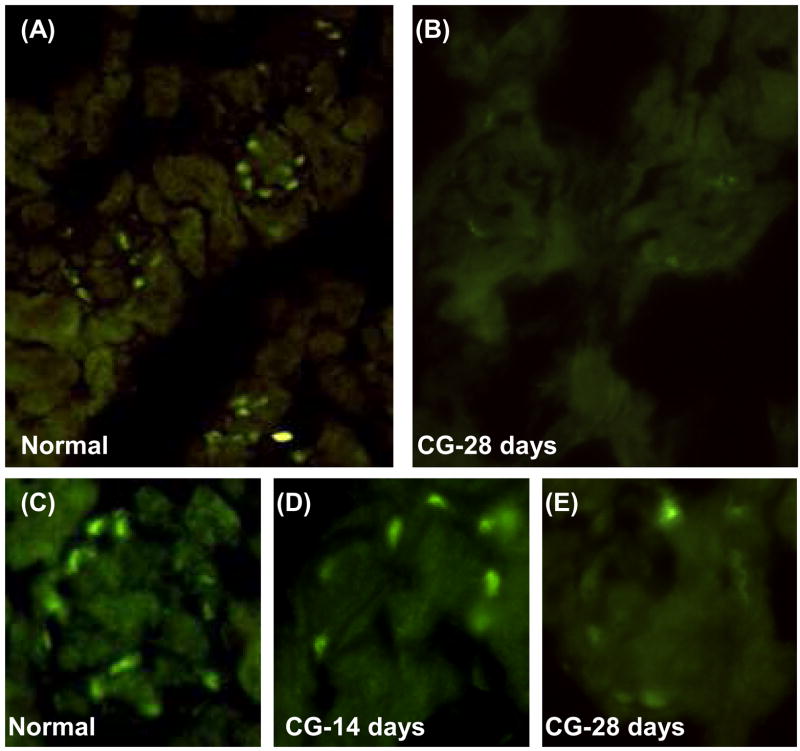

Renal expression of WT-1 in podocin/Vpr mice with collapsing glomerulopathy

We further examined the relationship between the amount of urinary exosomal WT-1 and the staining of WT-1 in frozen sections of mice treated with doxycycline. In untreated control podocin/Vpr transgenic mice WT-1-positive cells were detected in the periphery of glomeruli but not in renal tubular cells (Fig. 6A, C). The number of WT-1-positive cells decreased slightly at 14 days (Fig. 6D) and decreased more prominently at 28 days (Fig. 6B, E) after uninephrectomy and continuous doxycycline administration. Therefore, increases in urinary exosomal WT-1 correspond to decreases in WT-1 staining in glomeruli.

Figure 6. Immunofluorescence staining of WT-1 in kidneys from podocin/Vpr transgenic mice.

WT-1-positive cells were detected on the peripheral layer of glomerular capillaries from normal mice but not in tubular cells (A) and significantly decreased after uninephrectomy and 28 days doxycycline administration (B). Lower panel: typical single glomerulus staining of WT-1 from normal mice (C), 14 days (D), and 28 days of doxycycline in podocin/Vpr transgenic mice (E). Original magnification is 400X for (A) and (B) and 200X for (C)–(E).

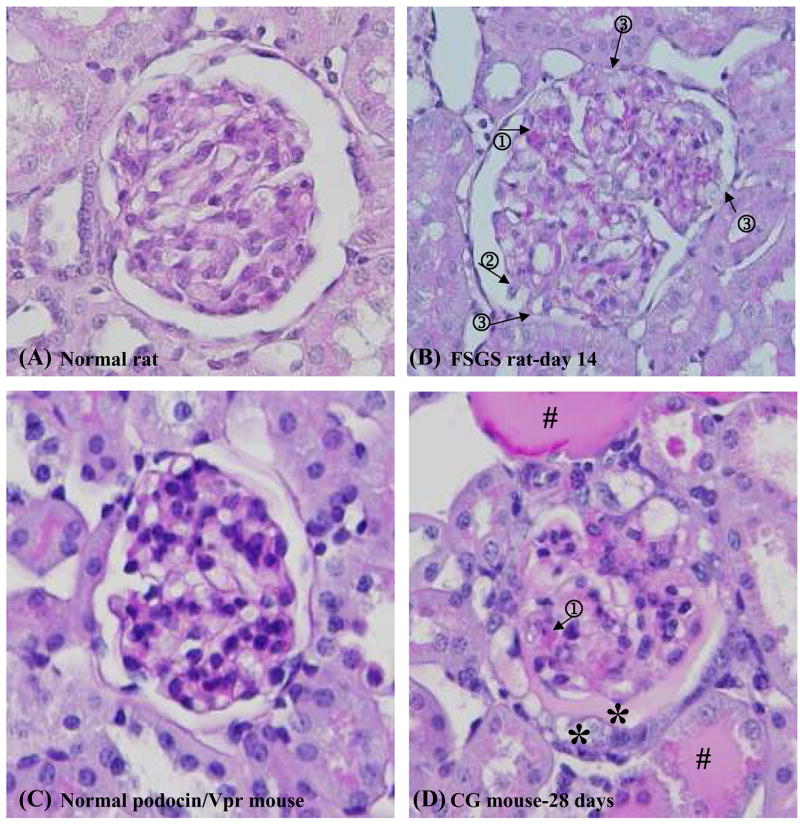

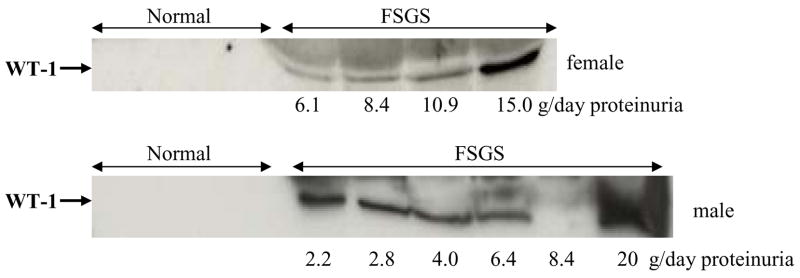

Urinary exosomal WT-1 in FSGS patients

We collected spot urine samples from healthy volunteers and FSGS patients. We analyzed urinary exosomal WT-1 by western blotting after normalization by urine creatinine. Urinary WT-1 was not detected in any healthy volunteers, but was detected in 9 of 10 patients with FSGS (Fig. 7). WT-1 was not detected in AKI patients (data not shown).

Figure 7. Urinary exosomal WT-1 in patients with FSGS.

Comparison of WT-1 in the exosomal fraction from spot urine samples between healthy volunteers and patients with FSGS.

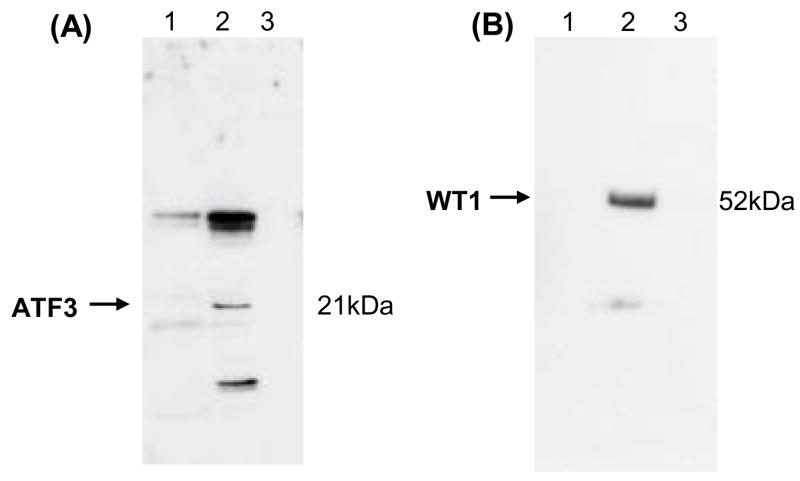

Distribution of ATF3 and WT-1 in different urine fractions

We selected urine samples with high levels of urinary ATF3 and WT-1 from a patient with AKI and a patient with FSGS, respectively, to investigate the distribution of transcription factors in various fractions of human urine. We standardized gel loading by loading the same proportion of the original urine volume for each fraction, except that unprocessed urine was loaded on the gel at a maximum volume of the well. Both urinary ATF3 (21 kDa) and WT-1 (52 kDa) were detected in the urine exosome fraction (200,000 × g pellet) but not in unprocessed urine samples or urine sediments (17,000 × g pellet) (Fig. 8A and B). These studies demonstrate that transcription factors are mostly present in the exosome fraction of human urine.

Figure 8. The distribution of ATF3 and WT-1 in different urine fractions.

Urine samples obtained from one patient with AKI (A) and one patient with FSGS (B). Lane 1: whole urine; lane 2: urine exosome fraction (200,000 × g pellet); lane 3: urinary sediment (17,000 × g pellet).

DISCUSSION

Transcription factors can be activated by physiological, pathological, and therapeutic stimuli and orchestrate key steps in renal development and in the initiation, persistence, and repair of many kidney diseases. TFs are up-regulated very early in response to renal injury and thus could theoretically serve as early detection markers. Studies from the mid 1990’s identified that renal c-myc increased over two fold at 7 days after cisplatin injection in rats, and the renal c-fos and v-jun increased after ischemia and reperfusion27, 28, 41. More recent microarray studies have identified many TFs that are dramatically up-regulated in kidney tissue after exposure to nephrotoxins or ischemia27–29. Several groups have found large increases in mRNA for ATF3, c-fos, c-jun, egr-1, and gdf15; in addition, we found early and large increases in crem, btg2, copeb, and tgif transcription factors. While changes in mRNA do not consistently predict changes in protein levels for many genes35, early response TFs are usually transcriptionally regulated, so that mRNA frequently predicts protein levels, at least acutely. The early response and large magnitude of change after renal injury are good characteristics for an ideal biomarker2. However, TFs are expressed at low levels intracellularly, and hard to detect outside of cells, which are poor characteristics for blood and urinary biomarkers. Since exosomes could contain intracellular proteins sampled during invagination of the MVB at the time of exosome formation, we hypothesized that we could detect TF in exosomes expelled into the urine.

ATF3 is a member of the ATF/CREB family of basic leucine zipper-type transcription factors that is induced by a variety of physiological stimuli and pathological stress signals42. Recent studies suggest that it regulates Toll-like receptor-stimulated inflammatory responses as part of a negative-feedback loop43, and may alter cell fate – with effects on both apoptosis and cell survival –depending on the context44. In present study, we selected ATF3 as a representative TF to investigate in AKI because we recently found that renal ATF3 mRNA increased 14-fold in the early phase (2 hr and 8 hr) of both I/R- and cisplatin- induced AKI by microarray29. More critically, we found that renal ATF3 protein was transiently increased at 8 hr and decreased to an undetectable level 24 hr in I/R AKI rats29; similar to findings reported by Yin et al36. We, and presumably others, did not pursue this otherwise logical hit because we expected that ATF3 could not be detected outside of cells. However, urinary exosomal ATF3 was detected as early as 0–2 hr after ischemia and reperfusion, peaked at 2–8 hrs which is before the maximum severity of renal tubular injury, and was slightly decreased at 24 hrs in AKI rats (Fig 1A). Urinary ATF3 was only detected in the exosomal fraction of urine, and was not detected in unfractionated urine, presumably because of its low concentration.

Urinary exosomal ATF3 paralleled the initial rapid increase in renal ATF3 expression but persisted even in the face of declining tissue levels at the maximum of renal tubular damage. We detected an unexpected biphasic pattern in cisplatin-induced AKI (Fig. 1B): urinary exosomal ATF3 was elevated on day 1, peaked at day 2, decreased to almost undetectable levels at day 3 and then increased again at day 5 (Fig. 1B) when renal tubule damage was the most severe14. In addition, urinary ATF3 was also detected in 4 patients with AKI; it decreased in one patient as the AKI became more severe, and decreased in a second patient during the recovery phase. The discrepancy between urinary exosomal and renal tissue levels seen at 24 hrs after ischemia, and 3 days after cisplatin were unexpected. While we cannot rule out technical artifacts, such as sensitivity of detection or differential release of exosomes during the 17,000 × g centrifugation, a biological explanation is more likely.

Because ATF3 can be an activator of transcription as a heterodimer or a repressor in the homodimeric form42, the function of ATF3 should not be expected to be simple or uniform. The unanticipated biphasic urinary exosomal ATF3 levels after cisplatin might reflect asynchronous waves of injury and/or response to injury. Miyaji et al. demonstrated that p53 peaked rapidly at day 1 after cisplatin injection and returned to almost baseline at day 3, on the other hand, p21 started to increase at day 3 and gradually reached peak levels at day 945. Recently Yoshida et al. showed that ATF3 transfection protects mice against ischemia-reperfusion injury resulting in suppression of p53 and induction of p2146, which is consistent with divergent functions of ATF3. The biphasic ATF3 response may represent separate events in different cell populations, as has been shown for heme oxygenase 1 in nephrotoxic AKI29. As useful as ATF3 may be as an early biomarker, an additional biomarker, in conjunction with ATF3, would be needed to determine the severity of injury, classification of injury type, or the timing of the insult, etc.

TFs are also involved in developmental programming of cells; during injury, cells can revert to a de-differentiated phenotype, and often follow developmental pathways during repair. Podocytes are highly differentiated epithelial cells that contribute to the size- and charge-selective glomerular filtration barrier. WT-1 is a zinc-finger TF that is required for podocyte maturation, but remains highly expressed into adulthood33. Dominant WT-1 mutations in the genes cause Wilms’ tumor and several podocyte diseases, such as Denys-Drash syndrome, Frasier syndrome, and isolated diffuse mesangial sclerosis47. WT-1 is often used as a molecular marker for differentiated podocytes and is downregulated in a variety of glomerular diseases with podocyte injury34, including animal models of FSGS39, 48. Podocytes are injured then lost in many primary and secondary glomerular diseases, including FSGS, membranous nephropathy, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, amyloid nephropathy, and diabetic nephropathy49. Podocyte injury is currently verified by electron microscopic examination of renal biopsies. Non-invasive methods to quantify podocyte damage are emerging, such as detection of podocyturia50, 51, WT-1 mRNA21, and podocyte associated proteins (podocalyxin) in the urinary sediment22. However, urinary podocytes are difficult to quantitate for technical reasons52, and WT-1 mRNA and podocalyxin are too variable to differentiate disease from normal21, 53, 54.

We selected two established podocyte injury models (puromycin-treated rats for FSGS and doxycycline-treated podocin/Vpr mice for collapsing glomerulopathy) to examine WT-1, a transcription factor associated with podocytes. Urinary exosomal WT-1 was detected earlier than proteinuria and much earlier than glomerular histological damage in FSGS animals (Fig. 4 and 5). Urinary exosomal WT-1 was detected in patients with FSGS, but not in age matched controls. As with ATF3, WT-1 was only detected in urinary exosomes, and could not be detected in whole urine. That urinary exosomal WT-1 increased in both models while tissue levels of WT-1 were decreasing either reported previously39, 48, or evaluated by semi-qualitative immunofluorescence (Figure 5), suggests that exosomes are shed from injured podocytes. It is not known if the release (shedding) occurs from the more normal podyctes (higher levels of WT-1), perhaps accounting for the decreased tissue levels, or from already dedifferentiated podocytes attached to the GBM, or if podocytes are shed first, then the exosomes are excreted from shed podocytes. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that urinary exosomal WT-1 may be a useful biomarker to detect podocyte injury.

TFs are involved in many common pathways of kidney diseases. For example, YAP1p, AP-1, and HSF1 are up-regulated in response to oxidative stress; NF-kappaB is a master switch for inflammatory responses; and hypoxia inducible factor (HIF-1 alpha) is a critical mediator of cellular adaptation to hypoxia in acute ischemia kidney injury, renal fibrosis, and renal cancer55. TFs as reporters for the pathophysiological mechanisms of renal disease is an emerging concept. In urine sediments the amount of mRNA for FoxP3, a transcription factor related to the control of immune response, has been reported to predict the outcome of acute graft rejection after kidney transplantation56. Nelson et al. used a transgenic approach that introduced a hypoxia-response element (HRE) targeting HIF-1〈 that produced β-hCG to monitor tumor hypoxia57. Chan et al. found that patients with active lupus nephritis have increased T-bet mRNA and depressed GATA-3 mRNA, the principal transcription factors for differentiation of type-1 and type-2 helper T lymphocytes, in the urine sediments and kidney tissue58; they also found that urinary T-bet mRNA can track the effect of immunosuppressive therapy59. Although these studies measured urinary TF mRNA, they suggest that urinary TFs are very promising for early detection, classification, and monitoring treatment of renal diseases.

We demonstrate here that the unique properties of exosomes make it possible to measure protein levels of transcription factors as a direct indicator of the status of cellular decision making processes. A combination of transcription factors may be needed to maximize their potential as urinary biomarkers. These results are encouraging, but there is much to be developed before exosomal transcription factors can fulfill their potential as biomarkers for clinical use. In addition to carefully designed and adequately powered validation studies, the current methods of ultracentrifugation and western blotting must be streamlined. To simplify the exosome isolation procedure, we demonstrated that a nanomembrane concentrator can be used in place of ultracentrifugation, making urinary exosome analysis feasible in a clinical lab54.

CONCLUSION

We found that the transcription factors ATF3 and WT-1 are concentrated in urinary exosomes to sufficiently high levels to allow measurement of TFs in urinary exosomes, despite an inability to detect TFs in whole urine. Urinary ATF3 might be novel renal tubular cell injury biomarker for detecting AKI; whereas urinary WT-1 might be a useful biomarker to detect podocyte injury in chronic kidney diseases. Both biomarker candidates require further validation in larger sample sets. Thus, transcription factors represent a new class of urinary biomarkers for renal disease that may offer insight into critical cellular regulatory pathways without the need for renal biopsy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and urine collections

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN, USA). All animals had free access to water and standard food and were treated in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for care and use of research animals.

Podocin/rtTA transgenic mice were crossbred with tetO/Vpr transgenic mice to produce podocin/Vpr mice. During administration of doxycycline, mice express Vpr selectively in podocytes and induce glomerular damage similar to human HIV-associated FSGS39.

Urine samples from animals were collected using protease inhibitors in metabolic cages, centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min to remove debris, and stored at −80°C until the isolation of exosome-associated proteins as previously described14, 26

AKI models

Cisplatin-induced AKI (n=28): Rats (250–280 g; 8 weeks of age) were given a single intravenous injection of cisplatin (6 mg/kg body weight) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Blood samples were collected from the tail vein in 8 rats under isoflurane anesthesia before (day 0) and at 1, 2, 3, and 5 days after cisplatin injection. Corresponding 8 hr-urine samples were collected on ice at the same time points from the same rats for the analysis of urinary transcription factors. Kidney tissues were harvested after kidney perfusion of abdominal aorta by pre-cooled 1X PBS from 4 rats at each time point.

Ischemia/reperfusion-induced AKI (n=4): Rats (180–210 g; 7 weeks) were subjected to 35 minutes bilateral ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) as previously described11. Urine samples were collected before (−24 to −16 hr) I/R, and at 0–2 hr, 2–8 hr and 8–24 hr after I/R. The rats were sacrificed at 8 hr or 24 hr after I/R for the collection of blood samples and kidney tissues.

Volume depletion (VD) (n=4): Rats (380–400 g; 14 weeks) were fed a low salt diet (0.03%) (Diet Test Inc. Philadelphia, PA, USA) 18 hr before intraperitoneal injection of furosemide as previously described11. We collected 6 hr-urine samples at −24 to −18 hr before and 24–30 hr after VD. Rats were sacrificed at 33 hr after furosemide injection for blood collection.

Podocyte injury models

PAN-induced FSGS rats (n=4): Rats (290–315 g; 9 weeks) were given an intravenous injection (60 mg/kg) of PAN (Biomol Research Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). 24 hr-urine samples were collected on ice before PAN and at days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 14 after PAN injection for examination of proteinuria and urinary transcription factors. The rats were sacrificed at 14 days after PAN injection for collection of blood samples and kidney tissues.

Combination of uninephrectomy and doxycycline induced CG mice (n=5): Podocin/Vpr mice (25–35g, 12 weeks) were subjected to uninephrectomy 1 week before the administration of doxycycline (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Doxycycline was given in drinking water (2 mg/ml) for 28 days to induce Vpr expression in podocytes39. 24 hr urine samples were collected in metabolic cages before uninephrectomy and days 7, 14, 21, and 28 after beginning doxycycline administration for urinary exosomal WT-1 examination. The mice were sacrificed at day 14 (n=2) and day 28 (n=3) for collection of blood and kidney tissue.

Patients and urine collections

All samples were collected under IRB-approved protocols at the NIH Clinical Center, or George Washington University, and all patients gave informed consent.

AKI patients: we collected spot human urine samples from 8 healthy volunteers and 4 ICU patients with AKI as defined by the Acute Kidney Injury Network 60, 61. In two AKI patients, we collected two urine samples: an early time point and near the peak SCr in one patient, and peak and recovery time points in another AKI patient.

CKD patients: we collected spot urine samples from 10 FSGS patients, 8 age and gender matched healthy controls, and 4 patients with lupus nephritis or diabetic nephropathy.

Protease inhibitors were added into all spot urine samples. Urine samples were subjected to a low spin (1000 × g 10 min) to remove cellular debris and then stored at −80 °C until the isolation of exosome-associated proteins as previously described26. Exosomal protein was normalized with urinary creatinine 14, 26

Examination of blood chemistry and proteinuria

SCr for rats was measured by picric acid-based colorimetric autoanalyzer (Astra 8 autoanalyzer; Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), albumin and total protein were measured by an autoanalyzer (Hitachi 917, Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). SCr for podocin/Vpr mice was measured by HPLC analysis62. The proteinuria in PAN-treated rats was semiquantitatively determined by urine test Chemstrips (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and albuminuria in podocin/Vpr mice was measured by albumin ELISA (Exocell, Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Isolation of urinary exosomes and fractionation of urine

Urine samples were extensively vortexed immediately after thawing. Urinary exosome-associated proteins were isolated by differential centrifugation (17,000 × g for 15 min to remove urinary sediment then 200,000 × g for 1 hr) as described previously14, 23, 26. Exosomes were isolated from timed urine collections (animal studies) or 10–16 ml of spot urine samples (human studies). To determine whether transcription factors could be enriched in urine fractions, urine samples from one AKI patient and one FSGS patient were unfractionated (whole urine) or separated into urine sediment (17,000 × g pellet), and exosome (200,000 × g pellet) fractions.

Western blot analysis of ATF3 and WT-1

Gel loading of urinary exosome-associated proteins was normalized by collection time for animal studies, by urine creatinine for human studies, and with the same proportion of original urine volume for different fractions from the same patient (Fig. 8) as previously described14. Protein samples were separated by 1D SDS/PAGE electrophoresis and then gels were transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% milk (1 hr), membranes were probed overnight at 4 °C with rabbit polyclonal antibody to ATF3 (1: 200) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), or WT-1 (1:200) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Blots were then incubated with peroxidase-conjugated, affinity-purified donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:100,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) for 90 min at room temperature. The antibody-antigen reactions were visualized by using ECL plus western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and BioMax XAR light-sensitive film (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA).

Examination of histology and immunohistochemistry

Under anesthesia half of the left kidney was removed and immediately fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution for paraffin embedding and the other half was embedded in O.C.T. medium (Sakura, Torrance, CA, USA).

The paraffin embedded kidney blocks were cut at 4 μm thickness, deparaffinized, and rehydrated and then stained with periodic acid Schiff (PAS) reagent for histological examination. For immunohistochemistry sections were incubated with 3% H2O2 to consume endogenous peroxidase, pre-incubated with 10% normal donkey serum to block non-specific binding, and incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-ATF3 (1: 100) (Santa Cruz) overnight at 4°C. The slides were followed by incubation with biotin-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 30 min at room temperature, and then reacted with streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase (Dako Corp., Carpinteria, CA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction products were visualized using a DAB kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA).

The frozen kidney tissues from podocin/Vpr transgenic mice were used for immunofluorescent staining of WT-1. Frozen kidneys were sectioned (5 μm) and slides were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes and then permeabilized in 0.3% Triton X100 in PBS for 5 min. Non-specific binding was blocked with using blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). The slides were incubated with anti-WT-1 antibody (Santa Cruz) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with Alexa-488 conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at room temperature for 1 hr. After several washes with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), slides were embedded in mounting reagent (Invitrogen). Images were captured using a fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar GmbH, Germany). The positive staining of ATF3 was inhibited more than 90% by preincubating primary antibody with ATF3 peptide at day 3 after cisplatin injection (ATF3 positive nuclei 2 ± 1 cells vs. 25 ± 5 cells/high power field (n = 3/group).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences between groups were analyzed for statistical significance by t-test or ANOVA. A P-value <0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIH, NIDDK. We thank Bertrand Jaber and Orfeas Liangos for insightful suggestions.

References

- 1.Hewitt SM, Dear J, Star RA. Discovery of protein biomarkers for renal diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1677–1689. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000129114.92265.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou H, Hewitt S, Yuen PS, et al. Acute kidney injury biomarkers-needs, present status, and future promise. NephSAP. 2006;5:63–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mishra J, Dent C, Tarabishi R, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2005;365:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagener G, Jan M, Kim M, et al. Association between increases in urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and acute renal dysfunction after adult cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:485–491. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikh CR, Jani A, Mishra J, et al. Urine NGAL and IL-18 are predictive biomarkers for delayed graft function following kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1639–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mishra J, Ma Q, Kelly C, et al. Kidney NGAL is a novel early marker of acute injury following transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:856–863. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachorzewska-Gajewska H, Malyszko J, Sitniewska E, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) correlations with cystatin C, serum creatinine and eGFR in patients with normal serum creatinine undergoing coronary angiography. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:295–296. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachorzewska-Gajewska H, Malyszko J, Sitniewska E, et al. Neutrophil-gelatinase-associated lipocalin and renal function after percutaneous coronary interventions. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:287–292. doi: 10.1159/000093961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh CR, Abraham E, Ancukiewicz M, et al. Urine IL-18 is an early diagnostic marker for acute kidney injury and predicts mortality in the intensive care unit. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3046–3052. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005030236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parikh CR, Mishra J, Thiessen-Philbrook H, et al. Urinary IL-18 is an early predictive biomarker of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Kidney Int. 2006;70:199–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muramatsu Y, Tsujie M, Kohda Y, et al. Early detection of cysteine rich protein 61 (CYR61, CCN1) in urine following renal ischemic reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1601–1610. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holly MK, Dear JW, Hu X, et al. Biomarker and drug target discovery using proteomics in a new rat model of sepsis-induced acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molls RR, Savransky V, Liu M, et al. Keratinocyte-derived chemokine is an early biomarker of ischemic acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1187–1193. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00342.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou H, Pisitkun T, Aponte A, et al. Exosomal Fetuin-A identified by proteomics: a novel urinary biomarker for detecting acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1847–1857. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen MT, Devarajan P. Biomarkers for the early detection of acute kidney injury. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0470-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rule AD, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, et al. Glomerular filtration rate estimated by cystatin C among different clinical presentations. Kidney Int. 2006;69:399–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White C, Akbari A, Hussain N, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate in kidney transplantation: a comparison between serum creatinine and cystatin C-based methods. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3763–3770. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang HR, Yang SF, Li ML, et al. Relationships between circulating matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 and renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;366:243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soylemezoglu O, Wild G, Dalley AJ, et al. Urinary and serum type III collagen: markers of renal fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:1883–1889. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.9.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szeto CC, Chan RW, Lai KB, et al. Messenger RNA expression of target genes in the urinary sediment of patients with chronic kidney diseases. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:105–113. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubo K, Miyagawa K, Yamamoto R, et al. Detection of WT1 mRNA in urine from patients with kidney diseases. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:824–826. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hara M, Yanagihara T, Kihara I, et al. Apical cell membranes are shed into urine from injured podocytes: a novel phenomenon of podocyte injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:408–416. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pisitkun T, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13368–13373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pisitkun T, Johnstone R, Knepper MA. Discovery of urinary biomarkers. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1760–1771. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R600004-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.du Cheyron D, Daubin C, Poggioli J, et al. Urinary measurement of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) protein as new marker of tubule injury in critically ill patients with ARF. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:497–506. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou H, Yuen PS, Pisitkun T, et al. Collection, storage, preservation, and normalization of human urinary exosomes for biomarker discovery. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1471–1476. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Q, Dunn RT, 2nd, Jayadev S, et al. Assessment of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by microarray technology. Toxicol Sci. 2001;63:196–207. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/63.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padanilam BJ, Hammerman MR. Ischemia-induced receptor for activated C kinase (RACK1) expression in rat kidneys. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F160–166. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.2.F160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuen PS, Jo SK, Holly MK, et al. Ischemic and nephrotoxic acute renal failure are distinguished by their broad transcriptomic responses. Physiol Genomics. 2006;25:375–386. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00223.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devarajan P, Mishra J, Supavekin S, et al. Gene expression in early ischemic renal injury: clues towards pathogenesis, biomarker discovery, and novel therapeutics. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;80:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kieran NE, Doran PP, Connolly SB, et al. Modification of the transcriptomic response to renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by lipoxin analog. Kidney Int. 2003;64:480–492. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Supavekin S, Zhang W, Kucherlapati R, et al. Differential gene expression following early renal ischemia/reperfusion. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1714–1724. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michaud JL, Kennedy CR. The podocyte in health and disease: insights from the mouse. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112:325–335. doi: 10.1042/CS20060143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quaggin SE. Transcriptional regulation of podocyte specification and differentiation. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;57:208–211. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks HL, Ageloff S, Kwon TH, et al. cDNA array identification of genes regulated in rat renal medulla in response to vasopressin infusion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F218–228. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00054.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yin T, Sandhu G, Wolfgang CD, et al. Tissue-specific pattern of stress kinase activation in ischemic/reperfused heart and kidney. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19943–19950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwab K, Witte DP, Aronow BJ, et al. Microarray analysis of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Nephrol. 2004;24:438–447. doi: 10.1159/000080188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chugh SS. Transcriptional regulation of podocyte disease. Transl Res. 2007;149:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hiramatsu N, Hiromura K, Shigehara T, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade inhibits the development and progression of HIV-associated nephropathy in a mouse model. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:515–527. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barisoni L, Schnaper HW, Kopp JB. A proposed taxonomy for the podocytopathies: a reassessment of the primary nephrotic diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:529–542. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04121206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida T, Kurella M, Beato F, et al. Monitoring changes in gene expression in renal ischemia-reperfusion in the rat. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1646–1654. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hai T, Wolfgang CD, Marsee DK, et al. ATF3 and stress responses. Gene Expr. 1999;7:321–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilchrist M, Thorsson V, Li B, et al. Systems biology approaches identify ATF3 as a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature. 2006;441:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature04768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guerra S, Lopez-Fernandez LA, Garcia MA, et al. Human gene profiling in response to the active protein kinase, interferon-induced serine/threonine protein kinase (PKR), in infected cells. Involvement of the transcription factor ATF-3 IN PKR-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18734–18745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyaji T, Kato A, Yasuda H, et al. Role of the increase in p21 in cisplatin-induced acute renal failure in rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:900–908. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V125900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshida T, Sugiura H, Mitobe M, et al. ATF3 protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:217–224. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005111155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niaudet P, Gubler MC. WT1 and glomerular diseases. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:1653–1660. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clement LC, Liu G, Perez-Torres I, et al. Early changes in gene expression that influence the course of primary glomerular disease. Kidney Int. 2007;72:337–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shankland SJ. The podocyte’s response to injury: role in proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2131–2147. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vogelmann SU, Nelson WJ, Myers BD, et al. Urinary excretion of viable podocytes in health and renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F40–48. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00404.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu D, Petermann A, Kunter U, et al. Urinary podocyte loss is a more specific marker of ongoing glomerular damage than proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1733–1741. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005020159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petermann A, Floege J. Podocyte damage resulting in podocyturia: a potential diagnostic marker to assess glomerular disease activity. Nephron Clin Pract. 2007;106:c61–66. doi: 10.1159/000101799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kanno K, Kawachi H, Uchida Y, et al. Urinary sediment podocalyxin in children with glomerular diseases. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;95:c91–99. doi: 10.1159/000074322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheruvanky A, Zhou H, Pisitkun T, et al. Rapid isolation of urinary exosomal biomarkers using a nanomembrane ultrafiltration concentrator. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1657–1661. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00434.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haase VH. The VHL/HIF oxygen-sensing pathway and its relevance to kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1302–1307. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muthukumar T, Dadhania D, Ding R, et al. Messenger RNA for FOXP3 in the urine of renal-allograft recipients. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2342–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nelson DW, Cao H, Zhu Y, et al. A noninvasive approach for assessing tumor hypoxia in xenografts: developing a urinary marker for hypoxia. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6151–6158. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan RW, Lai FM, Li EK, et al. Imbalance of Th1/Th2 transcription factors in patients with lupus nephritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:951–957. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan RW, Lai FM, Li EK, et al. The effect of immunosuppressive therapy on the messenger RNA expression of target genes in the urinary sediment of patients with active lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1534–1540. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Molitoris BA, Levin A, Warnock DG, et al. Improving outcomes of acute kidney injury: report of an initiative. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2007;3:439–442. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yuen PS, Dunn SR, Miyaji T, et al. A simplified method for HPLC determination of creatinine in mouse serum. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F1116–1119. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00366.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.