Intercellular adhesion plays a central role in normal metazoan development and homeostasis (1, 2). Cadherin–catenin-mediated adhesion structures are composed of multiple core proteins that may have not only common but also distinct functions. In this issue of PNAS, two studies from the Fuchs laboratory (3, 4) provide interesting novel insights into differential roles of cadherin–catenin proteins in balancing the structural integrity and physiological homeostasis of mammalian epidermis. Tinkle et al. (4) used novel transgenic shRNA strategy to address the functional significance of the two most prominent epidermal cadherins (E- and P-cadherins). This study provided a first look at epidermis lacking classical cadherins and uncovered a critical role of these proteins in the maintenance of epithelial integrity and cell survival. The study by Perez-Moreno et al. (3) revealed interesting connections between p120–catenin and regulation of cytokinesis and skin cancer. Together with previously published data, these new findings enable a direct comparison of various loss-of-function phenotypes to discern the common and unique, adhesion-dependent and adhesion-independent, roles of cadherin and catenin proteins in normal epithelial tissue homeostasis and cancer.

The cadherin–catenin complexes, constituting the main building block of the adherens junctions (AJs), have long been known to play a pivotal role in balancing barrier and tissue renewal functions of all epithelial tissues. AJs are assembled by direct binding between extracellular domains of cadherins (5). The cytoplasmic domain of cadherins interacts with p120 and β-catenins. Whereas p120-catenin plays an important role in the delivery and retention of cadherins at the AJs, β-catenin provides a connection to α-catenin, which is required for the actin-dependent clustering of cadherin–catenin complexes to form the AJs. In the past decade, the in vivo roles of AJ molecules, E-cadherin, P-cadherin, and α- β-, and p120-catenins, were explored by using conditional gene knockout strategies (1). These studies demonstrated that cadherin–catenin complexes are not only the structural elements stabilizing adhesive contacts but also important signaling centers that may function as biosensors of the external cellular microenvironment (1). β-Catenin, for example, apart from being a crucial component of the AJs, is also a key element of the Wnt signaling pathway, which plays a pivotal role in the control of normal development and cancer (6). Deletion of β-catenin in skin epidermis results in the failure of hair follicle stem cell differentiation (7), whereas overexpression of stabilized β-catenin causes de novo hair follicle morphogenesis and hair follicle tumors (8). Similarly, epidermis-specific ablation of other catenins affects several key signal transduction pathways. Deletion of α- and p120-catenins leads to hyperactivation of MAPK and NFκB signaling and hyperplasia (9–11). Moreover, when α-catenin−/− keratinocytes are grafted on the skins of nude mice, these cells form invasive tissue replete with inflammation that resembles squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (9). Because catenins are required for the formation of the AJs, the remarkable phenotypes in catenin mutant tissues raise an important question: are these phenotypes due to the defects in AJs, or they are AJs independent? One way to address this question is to analyze the significance of cadherins, which should be necessary for the formation of the AJs. However, deletion of E-cadherin in skin epidermis did not result in significant impairment of AJs, potentially due to compensation by P-cadherin (12–14). It remained unknown whether E- and P-cadherins play a redundant role in skin epidermis. Do cadherins and catenins function in parallel with each other to suppress proliferative and inflammatory responses? How relevant is the AJ-mediated adhesion system to tumor suppressor mechanisms and how these mechanisms cross-talk with the epidermal microenvironment? Some of these important questions have now been addressed by two novel studies from the Fuchs' laboratory (3, 4). These new data provide evidence that even though cadherin–catenin complexes function coordinately to maintain keratinocytes adhesion; they do differ in their ability to influence inflammatory and proliferative responses (Fig. 1).

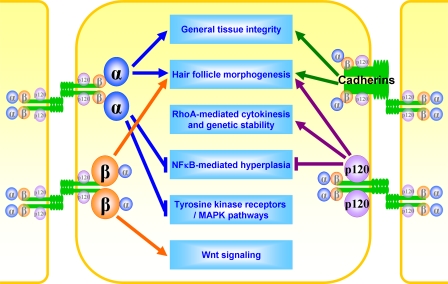

Fig. 1.

Similar and distinct functions of cadherin–catenin proteins in skin epidermis. The schematic diagram shows connections between cadherin–catenin proteins and cellular phenotypes revealed by loss-of-function experiments. While cadherins appear to be primarily responsible for mechanical tissue integrity, catenins also are involved in regulation of multiple signal transduction pathways.

The report by Tinkle et al. in this issue of PNAS (4) combines the conditional knockout approach with a novel transgenic shRNA technology to ablate E-cadherin and knockdown P-cadherin in the epidermal compartment (E-cad−/−/P-cadKD mice). Because of a tight chromosomal linkage of the two genes, a mutual role of both proteins in skin biology would have been otherwise difficult to assess. The authors found that loss of both cadherins resulted in prominent AJ defects (4). These data revealed an additive role for E- and P-cadherins in epithelial homeostasis and suggested that, in epidermis, the quantity was more important than the quality, as the overall classical cadherin expression levels rather than a particular subtype was critical for the maintenance of epidermal integrity. The most exciting finding of this study was a complete absence of changes in MAPK and NFκB activities and the lack of inflammation and hyperplasia in E-cad−/−/P-cadKD skins. Because these phenotypes were prominently featured in both αE-catenin−/− and p120-catenin−/− epidermises (9–11), absence of these changes in E-cad−/−/P-cadKD keratinocytes strongly indicates that α- and p120-catenins influence cell signaling and proliferation independently from cadherin-mediated adhesion. In contrast, both E-cad−/−/P-cadKD and αE-catenin−/− epidermises displayed increased numbers of apoptotic cells. Thus, AJ-mediated suppression of apoptosis in skin epidermis appears to rely on cadherin-mediated adhesion, and this is similar to the previously discovered role of VE-cadherin in endothelial cells (15). An important question that remains unanswered is whether loss of both cadherins affects the β-catenin–Wnt signaling pathway. Many earlier experiments with cells in culture indicated that cadherins are potent negative regulators of the β-catenin–Wnt signaling pathway (16, 17). E-cad−/−/P-cadKD animals now open a possibility to address this question in vivo. Overall, the analyses of E-cad−/−/P-cadKD epidermis described by Tinkle et al. (4) indicate that cadherins are more important for physical cell anchoring via AJs, which is crucial for maintaining tissue integrity, whereas p120 and α-catenins seem to play a dual role not only as cadherin stabilizers but also as regulators of cellular signaling. It is tempting to speculate that these two functions of p120- and α-catenins are in fact connected and they can link cadherin-mediated adhesion structures with signaling pathways. While such connection has been postulated as a central part of a “cadherins as biosensors” hypothesis (1), it has not been extensively analyzed, and this area is likely to be a fertile ground for future discoveries.

A second paper published in this issue of PNAS (3) extends prior analysis of p120-catenin−/− epidermis and reports the exciting discovery of a causal connection between depletion of p120-catenin and abnormal mitotic cell divisions. In a previously published paper from the same laboratory, the authors discovered an important connection between p120-catenin and the RhoA–NFκB signaling pathway, which plays a causal role in p120-catenin-mediated skin hyperplasia (11). Perez-Moreno et al. (3) continued the analyses of p120-catenin−/− keratinocytes and made interesting parallels between p120-catenin−/− skin grafts and human SCC. Not only did the p120-cateinin−/− grafts phenotypically resemble human SCCs, but many human SCCs displayed loss of p120-catenin and concomitant activation of the NFκB signaling pathway. The most surprising discovery came from the studies on cultured p120-catenin−/− keratinocytes. Despite the fact that these keratinocytes displayed hyperproliferation when grafted onto nude mice, in culture they grew significantly slower than wild-type cells. The authors traced these in vitro proliferation defects to an abnormally long M-phase, which often resulted in cleavage furrow regression and formation of binucleated cells. It has been demonstrated that inactivation of RhoA and activation of Rac1 are critical signaling functions of p120-catenin (18). This signaling function was also critical for p120-catenin-mediated regulation of mitosis, because hyperactivation of RhoA was not only necessary but also sufficient for the mitotic phenotypes (3). Because inhibition of NFκB signaling was able to rescue hyperplasia in grafted p120-catenin−/− skins without apparent impact on cell proliferation in vitro, the role of p120-catenin in attenuation of cell proliferation in vivo is likely to be indirect and rooted in the impact of hyperactive NFκB on skin microenvironment. The nature of this impact is presently unknown, and the role of epithelial–stromal interaction in stimulation of proliferation of p120-catenin−/− cells will be an exciting area of future research. Because chronic inflammatory responses in epidermis are not sufficient for cancer promotion, but rather result in psoriases and eczema-like phenotypes, the authors propose that both activation of NFκB and mitotic defects are responsible for hyperplasia in p120-catenin−/− epidermis. Indeed, because genetic instability is one of the well established causes of neoplastic transformation and cancer (19), linkage between p120-catenin deficiency and mitotic abnormalities represents a significant step forward in understanding the role of p120-catenin in cancer.

The Tinkle et al. (4) and Perez-Moreno et al. (3) articles provide significant new insights into epidermal biology and show that the roles of cadherins and catenins in maintaining epidermal integrity and homeostasis may differ quite dramatically. Dissecting cadherin–catenin interactions, as well as assessing their physiological relevance in balancing adhesion and proliferation, will not only yield important insights into the mechanisms of normal tissue homeostasis but also help us to understand the molecular events responsible for epithelial cancer.

Acknowledgments.

Work on cell–cell adhesion in our laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA098161-06.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Lien WH, Klezovitch O, Vasioukhin V. Cadherin-catenin proteins in vertebrate development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halbleib JM, Nelson WJ. Cadherins in development: Cell adhesion, sorting, and tissue morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3199–3214. doi: 10.1101/gad.1486806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Moreno M, Song W, Pasolli HA, Williams SE, Fuchs E. Loss of p120 catenin and links to mitotic alterations, inflammation, and skin cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15399–15404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807301105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tinkle CL, Pasolli HA, Stokes N, Fuchs E. New insights into cadherin function in epidermal sheet formation and maintenance of tissue integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15405–15410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807374105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. Adherens and tight junctions: Structure, function and connections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huelsken J, Vogel R, Erdmann B, Cotsarelis G, Birchmeier W. beta-Catenin controls hair follicle mor-phogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell. 2001;105:533–545. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gat U, DasGupta R, Degenstein L, Fuchs E. De Novo hair follicle morphogenesis and hair tumors in mice expressing a truncated beta-catenin in skin. Cell. 1998;95:605–614. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobielak A, Fuchs E. Links between α-catenin, NF-κB, and squamous cell carcinoma in skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2322–2327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510422103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasioukhin V, Bauer C, Degenstein L, Wise B, Fuchs E. Hyperproliferation and defects in epithelial polarity upon conditional ablation of alpha-catenin in skin. Cell. 2001;104:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez-Moreno M, et al. p120-catenin mediates inflammatory responses in the skin. Cell. 2006;124:631–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tunggal JA, et al. E-cadherin is essential for in vivo epidermal barrier function by regulating tight junctions. EMBO J. 2005;24:1146–1156. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tinkle CL, Lechler T, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Conditional targeting of E-cadherin in skin: Insights into hyperproliferative and degenerative responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:552–557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307437100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young P, et al. E-cadherin controls adherens junctions in the epidermis and the renewal of hair follicles. EMBO J. 2003;22:5723–5733. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmeliet P, et al. Targeted deficiency or cytosolic truncation of the VE-cadherin gene in mice impairs VEGF-mediated endothelial survival and angiogenesis. Cell. 1999;98:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orsulic S, Huber O, Aberle H, Arnold S, Kemler R. E-cadherin binding prevents beta-catenin nuclear localization and beta-catenin/LEF-1-mediated transactivation. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1237–1245. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.8.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottardi CJ, Wong E, Gumbiner BM. E-cadherin suppresses cellular transformation by inhibiting beta-catenin signaling in an adhesion-independent manner. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1049–1060. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anastasiadis PZ, Reynolds AB. Regulation of Rho GTPases by p120-catenin. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:604–610. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganem NJ, Storchova Z, Pellman D. Tetraploidy, aneuploidy and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]