Abstract

Cadmium is a worldwide environmental toxicant responsible for a range of human diseases including cancer. Cellular injury from cadmium is minimized by stress-responsive detoxification mechanisms. We explored the genetic requirements for cadmium tolerance by individually screening mutants from the fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) haploid deletion collection for inhibited growth on agar growth media containing cadmium. Cadmium-sensitive mutants were further tested for sensitivity to oxidative stress (hydrogen peroxide) and osmotic stress (potassium chloride). Of 2649 mutants screened, 237 were sensitive to cadmium, of which 168 were cadmium specific. Most were previously unknown to be involved in cadmium tolerance. The 237 genes represent a number of pathways including sulfate assimilation, phytochelatin synthesis and transport, ubiquinone (Coenzyme Q10) biosynthesis, stress signaling, cell wall biosynthesis and cell morphology, gene expression and chromatin remodeling, vacuole function, and intracellular transport of macromolecules. The ubiquinone biosynthesis mutants are acutely sensitive to cadmium but only mildly sensitive to hydrogen peroxide, indicating that Coenzyme Q10 plays a larger role in cadmium tolerance than just as an antioxidant. These and several other mutants turn yellow when exposed to cadmium, suggesting cadmium sulfide accumulation. This phenotype can potentially be used as a biomarker for cadmium. There is remarkably little overlap with a comparable screen of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae haploid deletion collection, indicating that the two distantly related yeasts utilize significantly different strategies for coping with cadmium stress. These strategies and their relation to cadmium detoxification in humans are discussed.

Keywords: cadmium, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, gene deletion, sulfur, stress, ubiquinone

Cadmium is one of the world's most serious environmental pollutants. Although naturally present in the environment, high concentrations found near industrial and toxic waste sites pose serious health risks, and exposure can lead to a variety of diseases. The major routes of human intoxication are from cigarettes, contaminated water and food, and occupational exposure. Chronic exposure to this long-lived (half-life of 15-20 years in humans) transition metal causes immune system deficiencies and injuries of the kidneys, lungs, and skeleton (reviewed in Järup, 2003). A classic example of cadmium toxicity is Itai-Itai disease, characterized by severe pain, proteinuria, bone fractures, and osteomalacia. Cadmium is listed as a class I human carcinogen by the IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) and has been associated with cancers of the lungs, prostate, pancreas, and kidneys (IARC, 1993).

Cadmium affects cellular processes such as cell-cycle progression, proliferation, differentiation, DNA replication and repair, and apoptosis (reviewed in Bertin and Averbeck, 2006). Cadmium also disrupts homeostasis of the chemically similar, yet biologically essential, metals calcium, zinc, and iron (reviewed in Martelli et al., 2006). Although cadmium is not a redox-active metal and cannot directly bind to DNA, it does indirectly induce oxidative stress thus compromising genome integrity (Waalkes and Poirier, 1984). Antioxidants bind to cadmium and this depletion leads to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), a normal byproduct of aerobic respiration (Waisberg et al., 2003). Not only does cadmium cause DNA damage, it also inhibits systems necessary to repair that damage (reviewed in Giaginis et al., 2006). This DNA repair inhibition makes cadmium a co-mutagen by acting synergistically with other genotoxic agents. Zinc protects or reverses the DNA repair inhibition induced by cadmium, possibly from competition between the two metals in zinc-finger repair proteins (Hartwig et al., 2002).

Eukaryotes have evolved multiple defense mechanisms to minimize cellular injuries resulting from cadmium insult. Cadmium is sequestered into vacuoles through binding to cysteine-rich peptides glutathione (GSH), phytochelatins (PCs), and/or metallothioneins depending on the organism. Additionally, Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells exposed to cadmium substantially reprogram their transcriptome and proteome to initiate a “sulfur-sparing” response (Fauchon et al., 2002). This reprogramming redirects sulfur to GSH production by reducing expression of sulfur-rich proteins and replacing them with isotypes consisting of fewer cysteine and methionine residues.

The advent of S. cerevisiae haploid deletion libraries has presented the unprecedented opportunity to carry out genome-wide screens for mutants defective in various biological processes. Recently, this approach was employed to identify 73 genes whose inactivation confers sensitivity to cadmium in bakers yeast (Serero et al., 2008). Prominent among the classes of genes identified in this screen are those involved in cellular transport, stress responses and transcriptional control. The value of data from these experimental approaches is likely to increase further when they can be compared between species. S. cerevisiae has a very distant evolutionary relationship to the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and in some biologically important processes (e.g. cell-cycle control, centromere structure, heterochromatin establishment) fission yeast is more closely related to typical metazoan organisms (Grewal and Jia, 2007; Wood et al., 2002). Here we report one of the first screens carried out with the S. pombe haploid deletion collection, which consists of 2649 mutants of nonessential genes. This screen has identified 237 mutants that are sensitive to cadmium, the majority of which were unknown or only suspected to be required for cadmium tolerance. Remarkably, few orthologs of these genes were identified in the comparable screen of S. cerevisiae, suggesting that the two organisms tolerate cadmium stress by substantially different mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and deletion library construction.

Standard procedures and media for S. pombe were used as previously described (Moreno et al., 1991). Heterozygous diploid deletion strains were constructed by BiONEER (Korea) using the Bähler et al. (1998) method of PCR-based targeted gene deletion using the KanMX4 cassette. From these strains viable haploid deletion strains used in this screen were generated with a genetic background of h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 or M216. There are 4967 open reading frames in fission yeast of which ∼3000 are estimated to be not essential for viability in the haploid state. The haploid deletion library used in this study consists of 2649 mutants representing ∼88% of the nonessential genes. A list of strains is available from the authors upon request.

Deletion library screens for cadmium sensitivity.

The deletion library was provided on agar plates and stamped in a 96-well format. Deletion mutants were inoculated from the plates using a sterilized 96-pin replicator in YES agar (0.5% yeast extract, 3% glucose, 2% agar) with supplements (225 mg/l adenine-HCl, 225 mg/l L-histidine, 225 mg/l L-leucine, 225 mg/l uracil, 225 mg/l L-lysine-HCl) and grown at 30°C to saturation density. Using the replicator, cells were spotted onto YES agar with or without 100μM cadmium sulfate hydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and incubated at 30°C for 4 days. The sensitivity of every mutant that displayed inhibited growth on cadmium plates compared with untreated plates was further explored using a more precise, dilution-series survival assay. Mid-log phase cultures were resuspended to identical optical densities (U-2000, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and serially diluted fivefold. Dilutions were spotted onto YES agar plates or YES agar containing 100μM cadmium, 1mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), or 0.6M potassium chloride (KCl) and incubated at 30°C for 3-5 days. The growth inhibition of each mutant was scored as severe (+++), moderate (++), or mild (+).

Microculture growth assay.

The following protocol was modified from Toussaint and Conconi (2006). Briefly, selected mutants and their corresponding wild-type were diluted to ∼0.1 OD600 nm (U-2000, Hitachi) from single colony inoculations and incubated at 30°C. Mid-log phase cultures were then diluted to 0.2 OD600 nm and treated with 100μM cadmium. One-hundred microliters of treated and untreated cultures was aliquoted in triplicate to a flat bottom 96-well plate. A microplate reader (VERSAmax, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) monitored growth at 30°C by measuring OD600 nm every 30 min for 48 h. Growth curves were plotted with Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA) from the raw OD600 nm data, and resultant curves are the average of the triplicates.

Gene ontology analysis of cadmium-sensitive mutants.

Biological interpretation of the cadmium-sensitive mutants was assessed using GOTermFinder (http://go.princeton.edu/cgi-bin/GOTermFinder) (Boyle et al., 2004). The mutant library gene list was used as the background distribution, and the S. pombe GeneDB was used as the gene association file. All evidence codes were searched, and the p value cutoff was 0.05.

RESULTS

Identification of Genes Required for Growth upon Cadmium Exposure

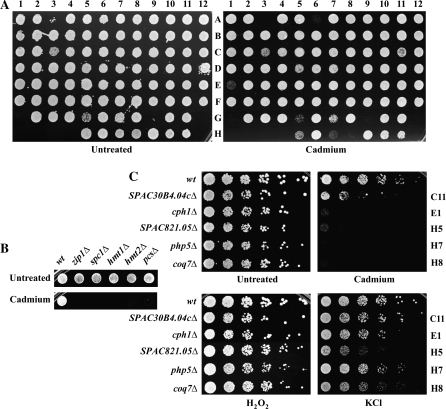

To evaluate cellular responses to cadmium in fission yeast, we exhaustively screened 2649 single gene deletion mutants for inhibited growth in the presence of cadmium. Stationary phase cells were replica plated in 96-well format onto YES (essentially glucose and yeast extract, see Materials and Methods) plates with or without 100μM cadmium sulfate. This concentration of cadmium was used because it severely impaired the growth of the well-characterized zip1Δ and spc1Δ cadmium-sensitive mutants but was well tolerated by wild-type (Supplementary Fig. 1). For comparison the Food and Drug Administration permissible level of cadmium in water is 20μM (0.005 mg/l) and the recent screen of the S. cerevisiae deletion library used 100 μM cadmium chloride (Serero et al., 2008). We liberally selected mutants with growth inhibition (see Fig. 1A for a representative plate); however, mutants with slow growth on untreated rich media (∼2%; data not shown) were excluded. The efficacy of the large-scale screen was validated by the positive growth inhibition of known cadmium-sensitive mutants: zip1Δ (internal control not in library), spc1Δ, hmt1Δ, hmt2Δ, and pcs1Δ (Fig. 1B) (Ha et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 2005; Perego et al., 1997; Toone et al., 1998; Vande Weghe and Ow, 1999; respectively).

FIG. 1.

Representative examples of the S. pombe deletion mutants screened for inhibited growth in the presence of 100μM cadmium sulfate. (A) Representative spot assays from the initial large-scale screen. Saturated cultures were replica plated onto rich media (YES) with or without 100μM cadmium sulfate and incubated at 30°C for 3 days (note: mutants A3 and G5 were not selected due to their slow growth on untreated plates). (B) Efficacy of large-scale screen. Known cadmium hypersensitive mutants (zip1Δ, spc1Δ, hmt1Δ, hmt2Δ, and pcsΔ) displayed inhibited growth in the presence of cadmium.(C) Representative dilution-series spot assays from selected mutants from representative large-scale screen plates (note: image of A6 [kin1Δ] dilution series not available). Log-phase wild-type and select mutants were serially diluted 1:5 and replica plated onto rich media alone or supplemented with 100μM cadmium sulfate, 1mM H2O2, or 0.6mM KCl.

All initially sensitive mutants were retested by spotting 5-fold serial dilutions of log-phase cultures onto plates with or without 100μM cadmium sulfate. To evaluate whether the observed mutant sensitivity was specific to cadmium or to stress in general, we additionally checked for growth inhibition on plates containing 1mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and 0.6M potassium chloride (KCl) (see Fig. 1C for representative plates). The relative survival of each mutant compared with that of the wild-type strain, normalized to the growth rate of untreated mutant cells, was estimated. Ultimately, 237 mutants (8.9% of the library and 4.9% of the genome) displayed varying levels of sensitivity to cadmium. Twenty-three mutants were strongly (+++) sensitive to cadmium, 90 were moderately (++) sensitive, and 124 were mildly (+) sensitive. Table 1 lists the mutants that were strongly or moderately sensitive to cadmium. For each sensitive mutant the table also lists the common gene name (if applicable), systematic name, S. cerevisiae ortholog (obtained from the yeast orthologous groups list), along with a brief description of each gene product. In many cases the gene description is based partly or largely on the S. cerevisiae ortholog. The genes are listed in the following categories: sulfate assimilation, PC synthesis and transport; ubiquinone biosynthesis; stress signaling; cell wall biosynthesis and cell morphology; gene expression and chromatin remodeling; vacuole function; and intracellular transport of macromolecules; other functions; and unknown functions. Supplementary Table S1 lists the genes whose deletion resulted in mildly reduced cellular growth on cadmium-treated plates compared with untreated plates. Both tables also list sensitivity to oxidative or osmotic stress. The majority of the mutants were only sensitive to cadmium and not to the other stresses (Table 2). The shared sensitivity of some mutants to cadmium and H2O2 or KCl shows that the products of these genes are general stress-related proteins and there is some overlap in the toxic effects of these stresses.

TABLE 1.

List of Mutants Severely or Moderately Sensitive to Cadmium

| Cd | H2O2 | KCl | Common name | Systematic name | S. cerevisiae ortholog | S. pombe gene description |

| Sulfate assimilation, synthesis, and transport of PC | ||||||

| +++ | + | + | sir1 | SPCC584.01c | MET10/YFR030W | Sulfite reductase involved in sulfur assimilation |

| +++ | + | SPAC4D7.06c | MET8/YBR213W | Siroheme synthase; sulfate assimilation | ||

| +++ | met16 | SPAC13G7.06 | MET16/YPR167C | 3′-phosphoadenylylsulfate reductase (PAPS) reductase; sulfate assimilation | ||

| +++ | SPAC1071.02 | MET18/YIL128W | Involved in transcription activation, NER, and sulfate assimilation. | |||

| +++ | SPBC12C2.03c | MET10/YFR030W | Contains an oxidoreductase FAD or NAD-binding domain; sulfate assimilation | |||

| +++ | + | hmt2 | SPBC2G5.06c | None | Sulfide-quinone oxidoreductase, sulfide metabolism | |

| +++ | + | gcs1 | SPAC22F3.10c | GCS1/YJL101C | Glutamate-cysteine ligase, required for GSH synthesis | |

| +++ | pcs1 | SPAC3H1.10 | None | PC synthetase | ||

| +++ | hmt1 | SPCC737.09c | None | Vacuolar ABC transporter involved in heavy metal tolerance, mediates ATP-dependent transport of PCs into the vacuole | ||

| ++ | + | + | SPCC1739.06c | MET1/YKR069W | Siroheme synthase; sulfate assimilation | |

| ++ | + | met14 | SPAC1782.11 | MET14/YKL001C | adenylylsulfate kinase; sulfate assimilation | |

| ++ | + | sua1 | SPBC27.08c | MET3/YJR010W | ATP sulfurylase; sulfate assimilation | |

| ++ | SPBC1198.08 | YFR044C | Zinc metalloprotease; GSH metabolism, required to use Cys-Gly and Glu-Cys-Gly as the sole source of sulfur | |||

| ++ | + | cys11 | SPBC36.04 | CYS12/YGR012W | Cysteine synthase | |

| Ubiquinone biosynthesis | ||||||

| +++ | + | ++ | coq7 | SPBC337.15c | COQ7/YOR125C | Ubiquinone biosynthesis |

| +++ | + | + | coq4 | SPAC1687.12c | COQ4/YDR204W | Ubiquinone biosynthesis |

| +++ | + | + | coq2 | SPAC56F8.04c | COQ2/YNR041C | Ubiquinone biosynthesis |

| ++ | coq5 | SPCC4G3.04c | COQ5/YML110C | Ubiquinone biosynthesis | ||

| ++ | coq3 | SPCC162.05 | COQ3/YOL096C | Ubiquinone biosynthesis | ||

| Stress signaling | ||||||

| +++ | ++ | ++ | spc1 | SPAC24B11.06c | HOG1/YLR113W | Stress-signaling MAP kinase |

| ++ | wis4 | SPAC9G1.02 | SSK22/YCR073C | Stress-signaling MAPKKK for Spc1 cascade | ||

| ++ | mcs4 | SPBC887.10 | SSK1/YLR006C | Stress-signaling response regulator for Spc1 SAPK cascade | ||

| ++ | SPBC713.05 | None | WD repeat protein; possibly involved in MAPK homolog signal transduction | |||

| Cell wall biosynthesis and cell morphology | ||||||

| +++ | ++ | +++ | pal1 | SPCP1E11.04c | YDR348C | Membrane-associated protein that localizes to sites of cell growth, required for cell wall integrity and cylindrical cell morphology |

| ++ | ++ | kin1 | SPBC4F6.06 | KIN1/YDR122W | Protein kinase regulating cell morphology and polarity | |

| ++ | + | + | SPCC63.02c | YJL216C | Alpha-amylase, GPI anchored protein | |

| ++ | SPBC342.03 | GAS2/YLR343W | glucanosyltransferase, GPI anchored protein likely involved in cell wall biosynthesis | |||

| ++ | gls2 | SPAC1002.03c | ROT2/YBR229C | Alpha glucosidase, cell wall biosynthesis | ||

| ++ | ++ | SPAC19G12.08 | SCS7/YMR272C | Fatty acid hydroxylase | ||

| Gene expression and chromatin remodeling | ||||||

| +++ | + | + | php5 | SPBC3B8.02 | HAP5/YOR358W | CCAAT-binding transcription factor; required for growth on nonfermentable carbon sources |

| +++ | + | SPCC126.04c | SGF73/YGL066W | Possible SAGA complex component, positive regulation of transcription | ||

| +++ | ++ | SPAC821.05 | None | Possible translation initiation factor; Mov34/MPN/PAD-1 domain | ||

| +++ | + | myo1 | SPBC146.13c | MYO5/YMR109W | Myosin (type I), actin cortical patch component | |

| +++ | + | cph1 | SPAC16C9.05 | YMR075W | PHD finger protein; component of Clr6p-HDAC complex II required for histone H3 K9 deacetylation and transcriptional repression | |

| +++ | SPAC664.02c | ARP8/YOR141C | Actin-like protein, component of INO80 chromatin remodeling complex | |||

| +++ | sin3 | SPAC29A4.20 | ELP3/YPL086C | HAT, RNA polymerase II elongator holoenzyme subunit | ||

| ++ | ++ | SPBC1921.07c | SGF29/YCL010C | Possible component of SAGA complex | ||

| ++ | kap1 | SPBC28F2.10c | NGG1/YDR176W | Possible component of SAGA complex | ||

| ++ | gcn5 | SPAC1952.05 | GCN5/YGR252W | Chromatin remodeling; component of SAGA complex | ||

| ++ | SPAC6B12.05c | IES2/YNL215W | PAPA-1-like region; subunit of INO80 complex involved in chromatin remodeling | |||

| ++ | + | + | SPCC18.06c | POP2/YNR052C | CCR4-NOT cofactor involved in transcription and mRNA deadenylation | |

| ++ | + | pap1 | SPAC1783.07c | YAP1/YML007W | AP-1-like transcription factor involved in oxidative stress response | |

| ++ | + | mcs1 | SPAC22F3.09c | MBP1/YDL056W | DSC1/MBF transcription factor complex | |

| ++ | + | SPAC17G8.07 | YAF9/YNL107W | Component of NuA4 HAT and Swr1p-containing (SWR-C) chromatin remodeling complexes | ||

| ++ | cuf1 | SPAC31A2.11c | CUP2/YGL166W | Transcription factor involved in responses to copper and iron | ||

| ++ | rdr1 | SPAC6F12.09 | None | RNA-directed RNA polymerase, regulates H3K9 methylation | ||

| ++ | pob3 | SPBC609.05 | YML069W | FACT complex component; involved in centromeric-heterochromatin integrity and chromosome segregation | ||

| ++ | SPBC21B10.13c | None | Transcriptional regulator with homeobox domain | |||

| ++ | clr3 | SPBC800.03 | HAD1/YNL021W | Histone deacetylase involved in chromatin silencing and chromosome segregation | ||

| ++ | ash2 | SPBC13G1.08c | BRE2/YLR015W | Zinc-finger protein, involved in chromatin silencing with Set1C complex | ||

| ++ | SPCC1494.10 | FLO8/YER109C | Transcriptional regulator | |||

| ++ | SPBC30B4.04c | YPL016W | Transcriptional regulator with ARID/BRIGHT DNA binding domain | |||

| Vacuole function | ||||||

| +++ | + | + | rav1 | SPBC1105.10 | RAV1/YJR033C | Regulates (H+)-ATPase of vacuolar membranes |

| ++ | ++ | vps17 | SPAPJ696.01c | VPS17/YOR132W | Vacuolar protein sorting | |

| ++ | + | SPBC14F5.13c | PHO8/YDR481C | Vacuolar alkaline phosphatase | ||

| ++ | + | sst2 | SPAC19B12.10 | None | Possibly involved in vacuolar protein sorting; Mov34/MPN/PAD-1 domain | |

| ++ | + | gyp1 | SPBC530.01 | GYP1/YOR070C | GTPase activating protein; protein targeting to vacuole | |

| ++ | + | vps66 | SPAC1783.02c | VPS66/YPR139C | Vacuolar protein sorting | |

| ++ | vps29 | SPAC15E1.06 | VPS29/YHR012W | Vacuolar protein sorting | ||

| ++ | plc1 | SPAC22F8.11 | PLC1/YPL268W | Phospholipase C, vacuole fusion | ||

| ++ | mak10 | SPBC1861.03 | YEL053C | Possibly involved in vacuole protein sorting | ||

| ++ | zhf1 | SPAC23C11.14 | ZRC1/YMR243C | Cation diffusion facilitator (CDF) metal cation transporter; possibly involved in cadmium transport to the vacuole | ||

| Intracellular protein transport | ||||||

| ++ | SPCC794.11c | ENT3/YJR125C | Vesicle targeting | |||

| ++ | SPCC1827.03c | PCS60/YBR222C | Peroxisomal AMP-binding protein, fatty acid transporter | |||

| ++ | SPAC24B11.12c | DNF2/YDR093W | P-type ATPase, aminophospholipid transporter | |||

| ++ | SPAC4G9.14 | YLR251W | Member of Mpv17 and PMP22 family of peroxisomal proteins | |||

| ++ | SPBC119.12 | YOR216C | Intracellular protein transport and golgi organization | |||

| ++ | + | SPAC17H9.08 | LEU5/YHR002W | Mitochondrial coenzyme A transporter | ||

| ++ | SPAC4G9.20c | YMC2/YBR104W | Mitochondrial carrier protein membrane transporter | |||

| ++ | + | SPAC823.10c | YDL119C | Predicted mitochondrial membrane transporter | ||

| Other functions | ||||||

| ++ | + | + | pmr1 | SPBC31E1.02c | PMR1/YGL167C | Golgi Ca2+/Mn2+ ATPase |

| ++ | + | ++ | SPAC1782.05 | RRD2/YPL152W | Protein phosphatase 2A activator; possibly involved in cell-cycle progression and microtubule dynamics | |

| ++ | + | SPCC16C4.10 | SOL1/YNR034W | Involved in tRNA export from the nucleus | ||

| ++ | +++ | hos2 | SPAC1805.07c | None | High osmolarity sensitive, subunit of DASH complex involved kinetochore function | |

| ++ | ++ | ask1 | SPBC27.02c | ASK1/YKL052C | DASH complex | |

| ++ | + | sum2 | SPBC800.09 | SCD6/YPR129W | Possibly involved in G2/M phase control | |

| ++ | + | SPAC13C5.04 | YLR126C | Glutamine amidotransferase domain, possibly involved in metal homeostasis | ||

| ++ | + | SPCC550.03c | SKI2/YLR398C | DEAD/DEAH box helicase; may function in translational regulation and ribosome biogenesis | ||

| ++ | cut8 | SPAC17C9.13c | STS1/YIR011C | Sister chromatid separation; possibly involved in proteosome function | ||

| ++ | pub1 | SPAC11G7.02 | RPS5/YER125W | E3 ubiquitin ligase | ||

| ++ | SPBC3H7.09 | YLR246W | Zinc-finger protein, involved in palmitoylation of Ras2 | |||

| ++ | alp14 | SPCC895.07 | STU2/YLR045C | Kinetochore-associated, required for the spindle checkpoint; cell morphology | ||

| ++ | mph1 | SPBC106.01 | MPS1/YDL028C | Protein kinase involved in the spindle checkpoint pathway | ||

| ++ | ade2 | SPAC144.03 | ADE12/YNL220W | Purine synthesis, cadmium tolerance | ||

| ++ | tsc1 | SPAC22F3.13 | None | Amino acid import | ||

| ++ | SPAC9.02c | YDR071C | N-acetyltransferase, GNAT family | |||

| ++ | bag102 | SPBC530.03c | SNL1/YIL016W | BAG domain protein family, possible chaperone regulator activity | ||

| ++ | SPAC20H4.09 | None | DEAD/DEAH box helicase | |||

| ++ | ubp14 | SPBC6B1.06c | UBP14/YBR058C | Zinc-finger protein involved in protein deubiquitination | ||

| Unknown functions | ||||||

| +++ | SPBC30B4.03c | YDL233W | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPAC12B10.03 | None | Unknown function, WD repeat protein, | |||

| ++ | SPCC162.02c | None | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPBC21D10.07 | YKL137W | Unknown function; has a coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix (CHCH) domain. | |||

| ++ | SPAC977.14c | None | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPAC14C4.06c | Unknown function, zinc-finger protein | ||||

| ++ | + | sif3 | SPAC12G12.15 | RMD8/YFR048W | Unknown function, Sad1-interacting factor 3 | |

| ++ | + | SPAC17A5.16 | SPAP27G11.12 | Unknown function | ||

| ++ | + | pic1 | SPBC336.15 | None | Unknown function | |

| ++ | + | SPAC1071.11 | None | Unknown function | ||

| ++ | + | ++ | SPBC3H7.12 | None | Unknown function | |

| ++ | SPCC553.01c | YGR042W | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPBC19G7.18c | None | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPBC20F10.05 | None | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPBPB2B2.19c | None | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPCC16C4.04 | None | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPBC2G5.03 | NCS6/YGL211W | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPCC1020.11c | YLL014W | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPBC2G2.14 | None | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPBC337.03 | RTT103/YDR289C | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPAC30.02c | KTI12/YKL110C | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | SPBC1A4.04 | None | Unknown function | |||

| ++ | + | SPBC83.18c | YNL152W | Unknown function; contains C2 domain | ||

| ++ | SPAC17A2.02c | YJR116W | Unknown function | |||

TABLE 2.

Summary of the Number of Cadmium-Sensitive Mutants and their Sensitivity to 1mM H2O2 and/or 0.6M KCl

| Stress(es) | Number of mutants |

| Cd only | 168 |

| Cd and H2O2 | 11 |

| Cd and KCl | 41 |

| Cd, H2O2, and KCl | 17 |

| Total | 237 |

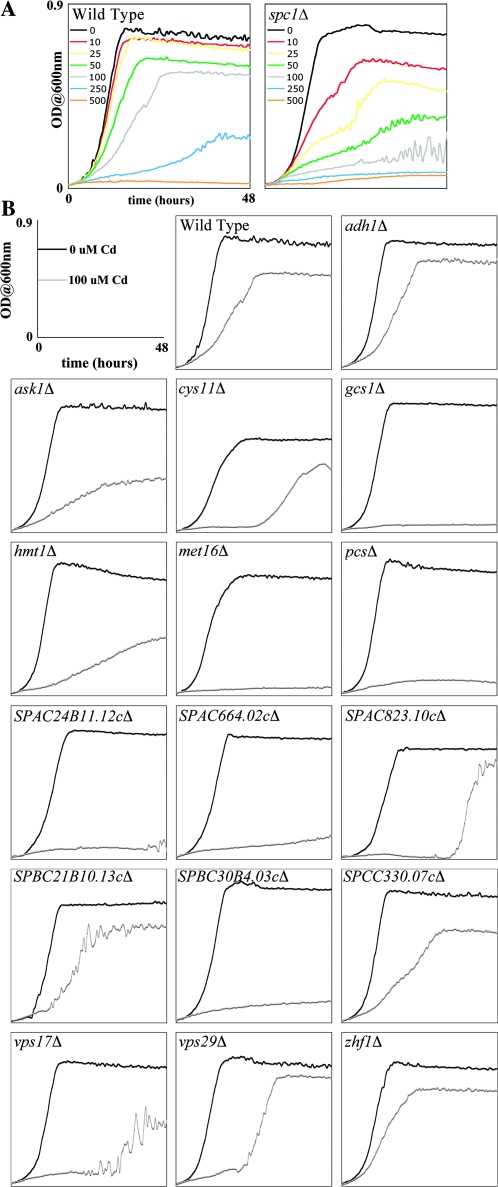

Microculture Growth Assays of Select Cadmium-Sensitive Mutants

We performed microculture growth assays on select mutants to evaluate the type of response to cadmium. Log-phase wild-type and select cadmium-sensitive mutants were treated with or without 100μM cadmium, and growth was monitored continuously for 2 days (Fig. 2). Initially, we tested different concentrations of cadmium on wild-type and spc1Δ to determine which would be suitable for this assay (Fig. 2A). The observed phenotypes of these two strains in liquid and spot assays were similar at 100μM cadmium; therefore, the subsequent growth assays were performed at that concentration. In general, the sensitivity of each mutant to cadmium observed on plates corresponded to that in liquid microcultures; however, there were a few that showed more sensitivity on plates than in liquid (Fig. 2B). This difference could be attributable to nutrient limitation or air exposure. Cells grown in the small volume (100 μl) of media in microculture experiments might exhaust the nutrients. Alternatively, cells grown in liquid are well aerated from frequent shaking, whereas colonies on plates contain heterogeneous microenvironments where cells on the outside are exposed to air but the inner cells may not be (Draculic et al., 2000). In this context, it is conceivable that the (lack of) nutrient and oxygen availability will affect general metabolism leading to the observed phenotypic differences.

FIG. 2.

Growth curves of select cadmium-sensitive mutants. Untreated and treated log-phase cells at equal densities were seeded into microculture wells, and growth was monitored by measuring OD600 nm every 30 min at 30°C for 48 h. (A) Wild-type and spc1Δ cells were subjected to varying concentrations of cadmium ranging from 0 to 500μM. (B) Select cadmium-sensitive mutants from the screen were subjected to 100μM cadmium, and growth was monitored.

Because growth in liquid cultures is monitored continuously, it is possible to observe the type of response each mutant has to cadmium (Fig. 2B). No growth, as seen in gcs1Δ, or a lowered plateau phase, as seen in SPBC27.02cΔ, can be interpreted that the missing gene is essential in the toxic response and that no other mechanisms can compensate for its loss leading to premature death. Conversely, an increased lag phase, as seen in SPAC823.10cΔ, and a decreased growth rate, as seen in hmt1Δ, suggests that the deleted gene leads to cadmium sensitivity but its loss can be compensated by other mechanisms (Jo et al., 2008).

GO Analysis of Cadmium-Sensitive Mutants

We performed a GO analysis (p value < 0.05) of all 237 cadmium-sensitive genes to identify which biological process categories were enriched (Table 3). GO enrichment provided an unbiased method of categorizing the genes, and allowed for multiple annotations within genes to be identified when present. Several annotated terms/categories were enriched, and many of them were subsets of the others. The three main enriched terms were: the inorganic stress response, sulfur metabolism, and the mitotic cell cycle (Table 3). Within the inorganic stress response category, response to metals and cadmium were enriched as expected. Subcategories of sulfur metabolism included sulfate assimilation, and biosynthesis of the sulfur-containing amino acids. The last enriched category includes genes involved in the mitotic cell cycle and more specifically genes whose products function in the spindle assembly during mitotic chromosome reorganization. The specific genes annotated to these terms and the nonenriched genes will be discussed in more detail.

TABLE 3.

GO Analysis of Cadmium-Sensitive Mutants

| (A) GO (biological process category) | Cluster freq. (out of 237) | Genome freq. (out of 2649) | p value |

| Response to inorganic substance | 3.8% (9) | 0.6% (15) | 0.0005 |

| Sulfur metabolic process | 5.1% (12) | 1.2% (33) | 0.0062 |

| Mitotic cell cycle | 8.9% (21) | 3.5% (94) | 0.0239 |

| (B) GO biological process (subcategory legend) | Genes in category | Enriched subcategory | Description |

| Response to inorganic substance | |||

| SPAC22F3.10c/gcs1 | RM/RC | Glutamate-cysteine ligase (GSH biosynthesis) | |

| SPCC737.09c/hmt1 | RM/RC | LMW PC-Cd transporter | |

| SPAC144.03/ade2 | RM/RC | Adenylosuccinate synthetase | |

| RM-response to metal | SPAC3H1.10/pcs | RM/RC | PC synthetase |

| RC-response to cadmium | SPBC2G5.06c/hmt2 | RM/RC | Sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase |

| SPAC17A2.14 | RM | Metal ion transporter | |

| SPAC24B11.06c/spc1 | SAPK | ||

| SPBC887.10/mcs4 | Response regulator, Spc1 SAPK cascade | ||

| SPAC1783.07c/pap1 | AP-1-like transcription factor | ||

| Sulfur metabolic process | |||

| SPBC27.08c/sua1 | SA/CB/SB/MB | ATP sulfurylase | |

| SPAC1782.11/met14 | SA/CB/SB/MB | APS kinase | |

| SA-sulfate assimilation | SPAC13G7.06/met16 | SA/CB/SB/MB | PAPS reductase |

| CB-cysteine biosyn. | SPCC584.01c/sir1 | SA/CB/SB/MB | Sulfite reductase |

| SB-serine biosyn. | SPAC4D7.06c | SA | Siroheme synthase (siroheme) |

| MB-methionine biosyn. | SPCC1739.06c | MB | Uroporphyrin methyltransferase (siroheme) |

| SPBC1711.04 | MB | Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase | |

| SPBC36.04/cys11 | CB/SB | Cysteine synthase | |

| SPAC1039.08/ | CB/SB | Serine acetyltransferase | |

| SPBC8D2.18c/pi047 | Adenosylhomocysteinase (Met metabolism) | ||

| SPAC22F3.10c/gcs1 | Glutamate-cysteine ligase (GSH biosynthesis) | ||

| SPBC2G5.06c/hmt2 | Sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase | ||

| Mitotic cell cycle | |||

| SPBC27.02c/ask1 | SO/CS | DASH complex | |

| SPAC1805.07c/hos2 | SO/CS | DASH complex | |

| SO-spindle organization and biogenesis | SPAC589.08c/dam1 | SO/CS | DASH complex |

| SPCC417.02/hos3 | SO/CS | DASH complex | |

| CS-sister chromatid segregation | SPAC16A10.05c/dad1 | SO/CS | DASH complex |

| SPCC895.07/alp14 | SO | Spindle checkpoint component | |

| SPAC17C9.13c/cut8 | SO | Anaphase and 26S proteasome localization | |

| SPAC4F10.04 | SO | Protein phosphatase type 2A | |

| SPBC336.15/pic1 | CS | Inner centromere protein | |

| SPBC1703.14c/top1 | CS | DNA topoisomerase | |

| SPBC1685.15c/klp6 | CS | Kinesin-like protein | |

| SPAC24B11.06c/spc1 | SAPK | ||

| SPAC9G1.02/wis4 | MAPKKK, Spc1 SAPK cascade | ||

| SPBC887.10/mcs4 | Response regulator, Spc1 SAPK cascade | ||

| SPAC22F3.09c/mcs1 | DSC1/MBF transcription factor complex | ||

| SPBC800.09/sum2 | Involved G2/M phase checkpoint control | ||

| SPCC16C4.11/pgl | Involved in pentose-phosphate shunt | ||

| SPBC106.01/mph1 | Serine/threonine protein kinase | ||

| SPAC2F3.15/lsk1 | Serine/threonine protein kinase | ||

| SPCC188.02/par1 | Protein phosphatase PP2A | ||

| SPBC336.03/efc25 | Exchange factor Cdc25p-like | ||

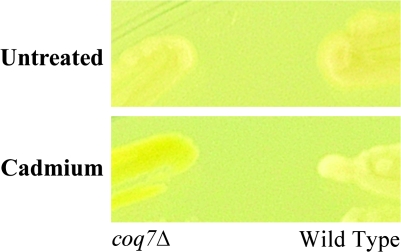

Yellow Mutants upon Cadmium Exposure

Interestingly, several mutants exposed to 100μM cadmium sulfate accumulated yellow pigment(Fig. 3 and Table 4). The strongest color was visible in the cys11 mutant. All of the ubiquinone biosynthesis (coq2, coq3, coq4, coq5, and coq7) mutants and the sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase (hmt2) mutant turned yellow. Ubiquinone biosynthesis mutants and hmt2 mutants also accumulate higher levels of hydrogen sulfide under normal conditions (Saiki et al., 2003). Indeed, all the yellow mutants grown in rich media also accumulated hydrogen sulfide as detected by a “rotten egg” smell.

FIG. 3.

Representative yellow mutant. Wild-type and coq7Δ cells were streaked onto rich media (YES) plates with or without 100μM cadmium sulfate and incubated at 30°C for 5 days.

TABLE 4.

List of Mutants that Accumulate Yellow Pigment when Exposed to 100μM Cadmium Sulfate for 5 Days

| Systematic name | Common name | Gene description |

| SPAC56F8.04c | coq2 | Ubiquionone biosynthesis |

| SPCC162.05 | coq3 | Ubiquionone biosynthesis |

| SPAC1687.12c | coq4 | Ubiquionone biosynthesis |

| SPCC4G3.04c | coq5 | Ubiquionone biosynthesis |

| SPBC337.15c | coq7 | Ubiquionone biosynthesis |

| SPBC36.04 | cys11 | Cysteine synthase |

| SPBC2G5.06c | hmt2 | Sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase |

| SPAC4A8.03c | ptc4 | Vacuolar phosphatase |

| SPAC6B12.12 | tom70 | Mitochondrial TOM complex component |

| SPAC1783.02c | vps66 | Vacuolar protein sorting |

| SPAC4G9.20c | Mitochondrial carrier protein membrane transporter | |

| SPAC823.10c | Mitochondrial carrier family of membrane transporters | |

| SPAC17H9.08 | Mitochondrial coenzyme A transporter | |

| SPBC14F5.13c | Alkaline phosphatase localized to vacuolar membrane |

DISCUSSION

In this study we sought to develop a more global picture of the mechanisms used to detoxify cadmium, an important environmental pollutant. This was accomplished by carrying out a genome-wide hunt for fission yeast mutants that display inhibited growth in the presence of 100μM cadmium sulfate. By using a concentration of cadmium that is well tolerated for many generations by wild-type strains, our intention was to identify genes that are needed for coping with chronic exposure to cadmium. Of course, many of these genes are likely to also be important for survival of acute exposure to higher levels of cadmium.

The screen rediscovered a number of mutants whose cadmium sensitivity was well known from previous studies, including spc1Δ, gcs1Δ, hmt1Δ, hmt2Δ, and pcs1Δ (Table 1) (Ha et al., 1999; Mutoh et al., 1995; Perego et al., 1997; Toone et al., 1998; Vande Weghe and Ow, 1999, respectively). As an example, Spc1, a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) homologous to human p38, regulates the global transcriptional response and controls the cell cycle upon environmental stimuli (Degols et al., 1996; Shiozaki and Russell, 1995). Indeed, the moderate to severe sensitivity of the spc1Δ mutant to all stresses was expected and served as an ideal general stress positive control (Tables 1 and 3). Isolation of spc1Δ and other known cadmium-sensitive-mutants serves as a validation of the screen. In total, 237 genes were identified in this screen, representing ∼8% of the genes analyzed in the screen. The large majority of these genes were not previously known to be involved in cadmium resistance, thus the generation of this list is a significant milestone in developing an understanding of cadmium detoxification mechanisms at the genome-wide level. In hindsight, a substantial fraction of these genes could have been suspected beforehand or at least rationalized in retrospect based on their known properties in fission yeast or other organisms, particularly S. cerevisiae. Yet the orthologs of the large fraction of these genes were not identified in a recent comparable screen of a S. cerevisiae haploid deletion library (Serero et al., 2008). As discussed in more detail below, the conclusion derived from this observation must be that the two organisms rely on substantially different strategies for detoxifying cadmium. These differences provide further evidence of the need for carrying out comparative studies with evolutionary divergent species.

The cadmium-sensitive mutants were categorized for their degree of sensitivity by dilution-series spot assays (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). We additionally examined whether they were sensitive to oxidative and/or osmotic stress. It was surprising that more cadmium-sensitive mutants shared sensitivity to potassium chloride than to hydrogen peroxide (Table 2), because the oxidative stress role of cadmium has been well characterized but the osmotic role has not. These results suggest that either cadmium can indirectly lead to osmotic stress, or some genes required for survival of osmotic stress may also have roles in tolerance of cadmium stress. More importantly, most of the mutants were only sensitive to cadmium, thus identifying specific genes required for tolerance to cadmium, or metals in general (Table 2).

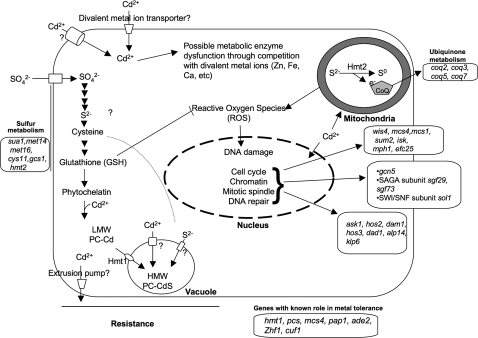

Gene Ontology analysis was performed on the 237 cadmium-sensitive mutants. The main significantly enriched (p value < 0.05) biological process categories included the inorganic stress response, sulfur metabolism, and the mitotic cell cycle. These and their related subcategories are discussed further and placed in context in the model shown in Figure 4.

FIG. 4.

Proposed model of the cellular targets and detoxification mechanisms of cadmium in fission yeast. Cd is transported inside the cell by divalent metal ion transporters and possibly other transporters. Cd interferes with cellular activities by competing with other divalent metal ions required in various metabolic enzymes. Once Cd gets into the cell, the first response will be detoxification. One of the detoxification mechanisms is extrusion of Cd outside the cell by membrane transporters (not known). In a second detoxification mechanism, cadmium binds to thiol-rich peptides such as GSH and PCs. LMW PC-Cd complexes are transported into vacuoles where they form HMW complexes with Cd and free sulfide. Depletion of GSH leads to increased ROS. Increased ROS leads to increased oxidative damage to DNA. Cd is also known to inhibit MMR. Cd also appears to interfere with mitotic spindle assembly and may affect cell-cycle progression, for example by activating Spc1 MAPK. One or more of these effects may explain the carcinogenic potential of cadmium. Representative mutant genes that are sensitive to Cd are shown along with cellular pathways.

The Inorganic Stress Response and the Spc1 Stress Kinase Pathway

Cells experience a variety of stressors; however, they must distinguish between the different stresses to mount the appropriate response. Therefore, the enrichment of genes involved in the response to inorganic stimuli, and more specifically to metals and cadmium, was expected (Table 3). Stress signaling through the evolutionarily conserved stress-activated MAPK (SAPK) pathway is essential for proper transcriptional reprogramming (reviewed in Gacto et al., 2003). In S. pombe, the MAPK Spc1/Sty1 is the central component of the SAPK pathway. Spc1 is activated by the upstream MAPK kinase Wis1, which is itself activated by the upstream MAPK kinase kinases (MAPKKKs) Wis4 and/or Win1. S. pombe has distinct signaling pathways in response to arsenite and ROS suggesting that the major mode of cellular toxicity of arsenite is not due to its oxidative stress induction (Rodríguez-Gabriel and Russell, 2005). Cells deleted for wis4 were not sensitive to arsenite or hydrogen peroxide; however they were moderately sensitive to cadmium. This suggests that there is an additional pathway in S. pombe in response to cadmium, and not a general metal response pathway. Mcs4 is a response regulator that acts upstream of Wis4 and is required for full resistance to arsenite (Buck et al., 2001; Rodríguez-Gabriel and Russell, 2005); thus its role in cadmium survival could have suspected. However, the data shown here may the first to demonstrate a clear role for a response regulator protein in coping with cadmium.

Spc1 activates Pap1, an oxidative stress-responsive transcription factor, and deletion of pap1 resulted in cadmium sensitivity most likely due to the oxidative stress influence (Toone et al., 1998). Pcr1, a subunit of the Atf1/Pcr1 heterodimeric transcription factor that is regulated by Spc1 (Shiozaki and Russell, 1996), was also identified in the screen (Supplementary Table S1).

In respect to the identification of multiple known components of the Spc1 stress-signaling pathway, it is interesting that the screen also uncovered the uncharacterized gene SPBC713.05. The protein product of this gene has striking similarity (∼42% identity) to human MORG1 (MAPK organizer 1), a member of the WD-40 protein family that was isolated as a binding partner of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway scaffold protein MP1 (Vomastek et al., 2004). MORG1 specifically associates with several components of the ERK pathway and stabilizes their assembly into an oligomeric complex. It is conceivable that SPBC713.05 has an analogous role in the Spc1 pathway of fission yeast. Orthologs of SPBC714.05 or MORG1 are absent from the S. cerevisiae genome.

Glutathione and Phytochelatins

GSH and PCs are instrumental in heavy metal detoxification in most organisms (reviewed in Clemens and Simm, 2003; Mendoza-Cózatl et al., 2005). These sulfur-rich peptides chelate metals in the cytosol (Mutoh and Hayashi, 1988), and it is thought that Hmt1 actively transports the resulting complexes into the vacuole for sequestration (Ortiz et al., 1992, 1995). The GSH biosynthetic pathway requires two ATP-dependent enzymes, Gcs1 and Gsh2 (Meister, 1995; Mutoh et al., 1995), and PCs are synthesized from GSH by phytochelatin synthase (Clemens et al., 1999; Ha et al., 1999). Indeed, the gcs1Δ and pcs1Δ mutants were hypersensitive to cadmium as expected (Tables 1 and 3); however, the sensitivity of gsh2Δ is unknown because it was not present in the library. The mild sensitivity of gcs1Δ to osmotic stress has been previously reported (Chaudhuri et al., 1997). However, the lack of sensitivity of gcs1Δ to hydrogen peroxide was unexpected (Tables 1 and 3) because S. cerevisiae cells deficient in GSH are hypersensitive to hydrogen peroxide (Izawa et al., 1995). This suggests that S. pombe utilizes different molecules as the major scavengers of ROS. Moreover, the hmt1Δ mutant, encoding the proposed low molecular weight (LMW) PC-cadmium transporter, was severely sensitive to cadmium as previously shown (Ortiz et al., 1992) (Tables 1 and 3).

Sulfur Assimilation

The sulfur assimilation and cysteine biosynthetic pathways are required for GSH and PC synthesis (reviewed in Mendoza-Cózatl et al., 2005), and most enzymes associated with these pathways were sensitive to cadmium when deleted (Tables 1 and 3 and Supplementary Table S1). Briefly, extracellular sulfate is converted to sulfide by a series of uptake, activation, and reduction steps. Sulfide is then condensed with O-acetylserine to form cysteine. Although highly upregulated upon cadmium exposure (Chen et al., 2003), deletion of either sulfate transporter, SPAC869.05c and SPBC3H7.02, resulted in no cadmium sensitivity, probably because the activity of one compensated for the loss of the other. Deletion of the sulfate activators, Sua1 and Met14, and the sulfate reducers, Met16 and Sir1, resulted in moderate or severe sensitivity to cadmium. The activity of Sir1 requires a prosthetic siroheme group (reviewed in Nakayama et al., 2000), and the siroheme synthesis mutants, SPAC4D7.06cΔ and SPCC1739.06cΔ, were severely and moderately sensitive to cadmium, respectively (Tables 1 and 3). Lastly, the cys11Δ and SPAC1039.08Δ mutants, encoding the final two genes in cysteine biosynthesis, were moderately and mildly sensitive to cadmium, respectively (Tables 1 and 3 and Supplementary Table S1). Our results highlight the functional importance of sulfur assimilation and cysteine biosynthesis in the cellular survival of cadmium, most likely due to their role in GSH and PC production, and possibly in sulfide production (explained below).

Sulfide Oxidation

Under normal conditions, most, but not all, sulfide is incorporated into cysteine in S. pombe; however, upon heavy metal exposure, free sulfide levels increase to aid in cell survival (Perego et al., 1997). Hmt2, a mitochondrial sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase, found in humans and fission yeast but not in budding yeast, is essential in cadmium tolerance, and hmt2Δ cells are hypersensitive to cadmium, as seen in this and previous studies (Vande Weghe and Ow, 1999). Hmt2 transfers electrons from sulfide (S2−) to ubiquinone (Coenzyme Q10, or CoQ10); thus, establishing a link between sulfide metabolism and CoQ10. CoQ10 is an essential component of the electron transport chain, and its antioxidant properties are well characterized (reviewed in Kawamukai, 2002; Bentinger et al., 2007). Indeed, all mutants from the library lacking a gene involved in CoQ10 biosynthesis (coq2, coq3, coq4, coq5, and coq7) were moderately or severely sensitive to cadmium, but only mildly sensitive to hydrogen peroxide indicating that CoQ10 plays a larger role in cadmium tolerance than just as an antioxidant. The cadmium sensitivity and yellow phenotype of coq mutants is reminiscent of the hmt2Δ phenotype (Table 1). Additionally, both CoQ10- and Hmt2-deficient mutants accumulate high levels of hydrogen sulfide under normal conditions (Uchida et al., 2000; Vande Weghe and Ow, 1999). Although increased free sulfide levels aid in tolerance to cadmium, the sensitivity of coq and hmt2 mutants to cadmium suggests that sulfide must be oxidized for cellular survival of cadmium. However, Vande Weghe and Ow (2001) proposed that precipitation of free cadmium as cadmium sulfide (CdS) blocks PC synthesis caused by inhibited GSH production.

Mitosis, the Spindle Assembly, and the Cytoskeleton Components

In human cells, cadmium elicits mitotic arrest (Chao and Yang, 2001) and acts as a cytoskeletal poison by depolymerizing microtubules and actins (Li et al., 1993; Wang and Templeton, 1996). Several mutants involved in the mitotic cell cycle and specifically in spindle organization and chromatid segregation were mildly to moderately sensitive to cadmium (Tables 1 and 3 and Supplementary Table S1). Notably, genes from the DASH complex, ask1, hos2, hos3, dam1, and dad1, were enriched (Table 3). Kinetochores assemble on the centromere and link the chromosome to the microtubules from the mitotic spindle. In S. pombe, the DASH complex localizes to kinetochores only during mitosis (Liu et al., 2005a). Kinetochore attachment is enhanced by Klp6 and Alp14 (Garcia et al., 2002), and proper chromosome segregation requires factors such as Cut8 and Efc25 (Papadaki et al., 2002; Tatebe and Yanagida, 2000). Mutants deleted for these genes were equally sensitive to KCl and cadmium, suggesting that cations in general target the spindle assembly. Proteins associated with the actin cortical patch, Myo1, SPAC664.02c, and SPCC794.11c, are involved in cadmium tolerance (Table 1); however, these genes are not sensitive to KCl. These results show that cadmium targets the cytoskeleton, and the mutant growth inhibition is likely due in some part to the mitotic checkpoint activated by Spc1 upon actin cytoskeletal damage (Gachet et al., 2001). These individual components were previously unknown to be important for survival in the presence of high levels of cadmium. The effect of cadmium on progression through cell cycle, spindle organization and cytoskeleton components potentially explain its carcinogenic potential.

Other Cellular Processes

Only 38 of the 237 sensitive genes were enriched (p value < 0.05) by GO analysis (Table 3). Here, we highlight the important biological processes from the moderately and severely sensitive genes not enriched by GO analysis and their roles in cadmium tolerance (Table 1). The vacuole is essential in sequestering the cadmium complexes. Mutants deficient in vacuolar protein sorting, vps17Δ, vps29Δ, and vps66Δ, and other vacuolar membrane proteins, rav1Δ and SPBC14F5.13cΔ, were sensitive to cadmium. The severely sensitive rav1 mutant is especially interesting. In S. cerevisiae, RAV1 is a regulator the (H+)-ATPase of vacuolar and endosomal membranes (RAVE) (Seol et al., 2001). It is thought that free cadmium enters the vacuole by a H+ antiporter; thus, loss of Rav1 could lead to impaired high molecular weight (HMW) PC-Cd-S formation through cadmium transport misregulation.

Cadmium inhibits DNA repair mechanisms (reviewed in Bertin and Averbeck, 2006). Although cadmium affects mismatch repair (MMR) in S. cerevisiae (Jin et al., 2003), it inhibits the ATPase and not the repair activity of the repair enzymes, and this inhibition is prevented by addition of cysteine and histidine (Banerjee and Flores-Rozas, 2005). No MMR mutants were sensitive to cadmium; however, SPAC1071.02, related to S. cerevisiae MET18 that was implicated as an accessory factor for nucleotide excision repair protein (NER), was severely cadmium sensitive (Lauder et al., 1996). Other cadmium-sensitive mutants identified in the screen that are involved in DNA repair or genome maintenance are nse5Δ and top1Δ. Nse5 is a non-structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) component of the Smc5-Smc6 involved in DNA repair and stability at stalled replication forks (Pebernard et al., 2006). Top1 is topoisomerase I, which is required for maintenance of chromatin organization (Uemura and Yanagida, 1984). By causing DNA damage or by interfering with DNA replication or DNA repair, cadmium stress may create situations in which the Smc5-Smc6 complex is required for replication fork stabilization or Top1 is required for maintenance of chromatin organization. In all cases the underlying source of DNA damage could arise from displacement of zinc by cadmium in the DNA binding domain of zinc-finger proteins (Asmuss et al., 2000), and this repair inhibition could be the carcinogenic action of cadmium (Dally and Hartwig, 1997).

Cells exposed to cadmium drastically reprogram their transcriptome (Chen et al., 2003). Several of the cadmium-sensitive genes encoded for transcription factors/regulators and chromatin remodelers (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). DNA methylation is increased in human cells exposed to long-term, low doses of cadmium (Jiang et al., 2008); however, arsenite exposure leads to DNA hypomethylation (Zhao et al., 1997). Regardless of DNA methylation status, another possible carcinogenic action of cadmium, and metals in general, is through epigenetic modifications. Indeed, the histone acetyltransferases (HATs) sin3 and gcn5, and other chromatin remodelers SPAC17G8.07 and ash2 were moderately or severely sensitive to cadmium. Although Cuf1 and Cuf2, copper-sensing transcription factors that regulate iron transport (Labbé et al., 1999), were only moderately and mildly cadmium sensitive, it would be interesting to see if these two genes have overlapping or redundant roles by examining a double mutant.

Comparison to a Genome-Wide Screen of S. cerevisiae Mutants that are Sensitive to Cadmium

Recently a S. cerevisiae deletion collection was screened for sensitivity to cadmium chloride (Serero et al., 2008). Among 4866 open reading frames tested, 73 were found to be important for cadmium survival. Remarkably, only three of these genes (GCN5, NGG1, and YAP1) have orthologs in the list of mutants that were either strongly or moderately sensitive to cadmium in fission yeast. This absence of large overlap suggests that the two distantly related yeasts utilize different strategies for survival in the presence of potentially toxic levels of cadmium. Indeed, it is well known that fission yeast possesses cadmium detoxification mechanisms that are absent in budding yeast, perhaps the best known being the ability to synthesize PCs. However, the majority of genes identified in our screen have orthologs in budding yeast (Table 1). For example, the ubiquinone biosynthesis pathway is clearly conserved in the two yeasts. Essentially, all of the genes encoding components of this pathway were uncovered in the fission yeast screen, whereas none of the corresponding genes were found in the screen of budding yeast mutants that are sensitive to cadmium (Serero et al., 2008). The budding yeast mutants defective in ubiquinone biosynthesis are viable and therefore should have been discovered in the cadmium screen if the gene products were required for survival in the presence of cadmium. The need for ubiquinone biosynthesis for cadmium tolerance in fission yeast likely arises from its connection to Hmt2, the sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase that is absent from the budding yeast genome.

Of the three genes that are shared in the cadmium-sensitive screens of fission yeast and budding yeast, two (GCN5 and NGG1) encode components of the SAGA HAT complex that is a coactivator for transcription, whereas the third (YAP1) is transcription factor involved in the oxidative stress response. These similarities underscore the importance of mounting appropriate transcriptional responses to cadmium stress that has been conserved between the two yeasts and probably other organisms as well.

When comparing the larger number of cadmium-sensitive mutants found in the fission yeast screen as compared with budding yeast, one factor to consider is that the fission yeast screen was carried out in an ade6-M210/M216 background. This background may have been advantageous. The ade6+ gene product and other purine biosynthetic enzymes participate in the conversion of the PC-cadmium complex to the PC-cadmium-sulfide complex, which is essential for metal tolerance (Juang et al., 1993; Speiser et al., 1992). Therefore, the ade6-M210/216 allele potentially caused a synergistic effect with the additional gene deletion. As an example, Speiser et al. (1992) showed that either ade6- or ade2-disrupted mutants behaved like wild-type in the presence of cadmium, but the double mutant had inhibited growth. This effect was confirmed in our screen by the moderate sensitivity of ade2Δ, harboring the ade6-M216 allele (Table 1).

Yellow Mutants and Cadmium Detection

This study identified several mutants that turned yellow when exposed to cadmium sulfate (Fig. 3 and Table 4). The yellow color is caused by the precipitation of CdS produced within the cell. The formation of CdS is independent of the cadmium compound tested, because hmt2Δ cells turned yellow upon exposure to cadmium chloride (Vande Weghe and Ow, 1999). Indeed, all the yellow mutants precipitate CdS and produce excess hydrogen sulfide; thus identifying other proteins involved in sulfide oxidation. These include the vacuolar phosphatase Ptc4, the Vps66 protein required for vacuolar protein sorting, and the proteins required for CoQ10 biosynthesis.

The identification of toxic sites contaminated with metals is globally important for human and environmental health, but detection of these metals can be costly and/or time consuming. As mentioned previously, cells deficient in Hmt2 turn yellow upon cadmium exposure, but they also turn brown and gray in the presence of copper and lead/bismuth, respectively (Vande Weghe and Ow, 2001). Therefore, it will be interesting to see if all the yellow mutants behave in a similar way to these other metals. Biomarkers for cadmium-contaminated soil have been identified in barley and rice seedlings using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) assays (Liu et al., 2005b, 2007), and Caulobacter crescentus has been engineered as whole-cell uranium biosensors (Hillson et al., 2007). However, they require the use of special equipment; whereas cadmium detection with these yeast mutants requires little effort, time, and money.

Perspective on Cadmium Toxicity in Humans

Although the genes uncovered in this study likely represent many of the most important biological processes for coping with cadmium toxicity in all organisms, it is important to consider how closely the experimental design mimics the most common forms of human exposure. Except in unusual situations of occupational accidents, most human exposure is chronic and progressive. In contrast, the experimental protocol used in this study is acute in that it uses a fixed concentration of cadmium over the period of a few days, which for fission yeast is many generations. Nevertheless, there is likely to be a large overlap in the cellular pathways used to tolerate both chronic and acute exposure to cadmium.

Our studies highlight some biological pathways that should be considered when evaluating the human health consequences of cadmium. One is the mechanism for synthesis of CoQ10. In humans, CoQ10 contributes to the production of high-energy phosphates required for muscle contraction and other cellular functions, but it also has a critical role as a free radical scavenger. In this latter capacity CoQ10 is thought to have vitally important roles in protection from neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's disease, in prevention of diabetes, and in cardiovascular health (Pepe et al., 2007). The perceived health benefits of CoQ10 have led to its widespread use as a dietary supplement, although much uncertainty remains about its actual utility. Given its extensive availability and the empirical evidence for its safety, CoQ10 should perhaps be considered as an agent for treatment of cadmium poisoning.

Our studies also may provide some new clues about the connection between cadmium and cancer. Thus far studies in this area have focused on the potential of cadmium to cause DNA damage and to inhibit DNA repair enzymes. Our data provide some support for these hypotheses and hint at potential targets such as pathways impacted by Smc5-Smc6 complex and topoisomerase I. Interestingly our screen did not detect any connections to MMR, NER, and base excision repair, all of which are thought to have significant roles in repair of cadmium-induced DNA damage (Bertin and Averbeck, 2006). Nor did it reveal a connection to Okazaki fragment processing unlike the comparable study of the budding yeast haploid deletion set (Serero et al., 2008). However, given that we now have a better understanding of the pathways that are critical for cadmium detoxification, it should be interesting in future studies to explore possibilities for synergistic relationships between mutants in these pathways and mutants defective in different mechanisms of DNA repair. Furthermore, the detection of multiple genes involved in assembly and function of the mitotic spindle suggests an alternative mechanism by which cadmium might cause genome instability and cancer.

SUPPLEMETARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

FUNDING

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (grant number ES010337).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of Russell laboratory and cell-cycle group of The Scripps Research Institute for support and encouragement. Thanks to Drs Takashi Toda for the zip1Δ strain, Anastasia Kralli for the use of the microplate reader, Valerie Wood for advice concerning the GO analysis, and Paul Nurse for his role in stimulating efforts that led to creation of the S. pombe gene deletion library. The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Asmuss M, Mullenders LH, Hartwig A. Interference by toxic metal compounds with isolated zinc finger DNA repair proteins. Toxicol. Lett. 2000;112–113:227–231. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bähler J, Wu JQ, Longtine MS, Shah NG, McKenzie A, 3rd, Steever AB, Wach A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;10:943–951. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Flores-Rozas H. Cadmium inhibits mismatch repair by blocking the ATPase activity of the MSH2-MSH6 complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1410–1419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentinger M, Brismar K, Dallner G. The antioxidant role of coenzyme Q. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(Suppl.):S41–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin G, Averbeck D. Cadmium: cellular effects, modifications of biomolecules, modulation of DNA repair and genotoxic consequences (a review) Biochimie. 2006;88:1549–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle EI, Weng S, Gollub J, Jin H, Botstein D, Cherry JM, Sherlock G. GO::TermFinder—Open source software for accessing gene ontology information and finding significantly enriched gene ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3710–3715. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck V, Quinn J, Soto Pino T, Martin H, Saldanha J, Makino K, Morgan BA, Millar JB. Peroxide sensors for the fission yeast stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:407–419. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao JI, Yang JL. Opposite roles of ERK and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases in cadmium-induced genotoxicity and mitotic arrest. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:1193–1202. doi: 10.1021/tx010041o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri B, Ingavale S, Bachhawat AK. apd1+, a gene required for red pigment formation in ade6 mutants of Schizosaccharomyces pombe, encodes an enzyme required for glutathione biosynthesis: A role for glutathione and a glutathione-conjugate pump. Genetics. 1997;145:75–83. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Toone WM, Mata J, Lyne R, Burns G, Kivinen K, Brazma A, Jones N, Bähler J. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:214–229. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S, Kim EJ, Neumann D, Schroeder JI. Tolerance to toxic metals by a gene family of phytochelatin synthases from plants and yeast. EMBO J. 1999;18:3325–3333. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S, Simm C. Schizosaccharomyces pombe as a model for metal homeostasis in plant cells: The phytochelatin-dependent pathway is the main cadmium detoxification mechanism. New Phytol. 2003;159:323–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dally H, Hartwig A. Induction and repair inhibition of oxidative DNA damage by nickel(II) and cadmium(II) in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1021–1026. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.5.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degols G, Shiozaki K, Russell P. Activation and regulation of the Spc1 stress-activated protein kinase in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:2870–2877. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draculic T, Dawes IW, Grant CM. A single glutaredoxin or thioredoxin gene is essential for viability in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;36:1167–1174. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauchon M, Lagniel G, Aude JC, Lombardia L, Soularue P, Petat C, Marguerie G, Sentenac A, Werner M, Labarre J. Sulfur sparing in the yeast proteome in response to sulfur demand. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:713–723. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gacto M, Soto T, Vicente-Soler J, Villa TG, Cansado J. Learning from yeasts: Intracellular sensing of stress conditions. Int. Microbiol. 2003;6:211–219. doi: 10.1007/s10123-003-0136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaginis C, Gatzidou E, Theocharis S. DNA repair systems as targets of cadmium toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006;213:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha SB, Smith AP, Howden R, Dietrich WM, Bugg S, O'Connell MJ, Goldsbrough PB, Cobbett CS. Phytochelatin synthase genes from Arabidopsis and the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1153–1164. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.6.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachet Y, Tournier S, Millar JB, Hyams JS. A MAP kinase-dependent actin checkpoint ensures proper spindle orientation in fission yeast. Nature. 2001;412:352–355. doi: 10.1038/35085604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MA, Koonrugsa N, Toda T. Spindle-kinetochore attachment requires the combined action of Kin I-like Klp5/6 and Alp14/Dis1-MAPs in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2002;21:6015–6024. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal SI, Jia S. Heterochromatin revisited. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:35–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison C, Katayama S, Dhut S, Chen D, Jones N, Bähler J, Toda T. SCF(Pof1)-ubiquitin and its target Zip1 transcription factor mediate cadmium response in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2005;24:599–610. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig A, Asmuss M, Ehleben I, Herzer U, Kostelac D, Pelzer A, Schwerdtle T, Bürkle A. Interference by toxic metal ions with DNA repair processes and cell cycle control: Molecular mechanisms. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl. 5):797–799. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillson NJ, Hu P, Andersen GL, Shapiro L. Caulobacter crescentus as a whole-cell uranium biosensor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:7615–7621. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01566-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC. Berrylium, cadmium, mercury and exposures in the glass manufacturing industry. International Agency for Research on Cancer Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC. 1993;58:119–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa S, Inoue Y, Kimura A. Oxidative stress response in yeast: effect of glutathione on adaptation to hydrogen peroxide stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:73–76. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järup L. Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br. Med. Bull. 2003;68:167–182. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G, Xu L, Song S, Zhu C, Wu Q, Zhang L, Wu L. Effects of long-term low-dose cadmium exposure on genomic DNA methylation in human embryo lung fibroblast cells. Toxicology. 2008;244:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin YH, Clark AB, Slebos RJ, Al-Refai H, Taylor JA, Kunkel TA, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA. Cadmium is a mutagen that acts by inhibiting mismatch repair. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:326–329. doi: 10.1038/ng1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo WJ, Loguinov A, Chang M, Wintz H, Nislow C, Arkin AP, Giaever G, Vulpe CD. Identification of genes involved in the toxic response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae against iron and copper overload by parallel analysis of deletion mutants. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;101:140–151. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang RH, McCue KF, Ow DW. Two purine biosynthetic enzymes that are required for cadmium tolerance in Schizosaccharomyces pombe utilize cysteine sulfinate in vitro. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993;304:392–401. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamukai M. Biosynthesis, bioproduction and novel roles of ubiquinone. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2002;94:511–517. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(02)80188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbé S, Peña MM, Fernandes AR, Thiele DJ. A copper-sensing transcription factor regulates iron uptake genes in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:36252–36260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder S, Bankmann M, Guzder SN, Sung P, Prakash L, Prakash S. Dual requirement for the yeast MMS19 gene in DNA repair and RNA polymerase II transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6783–6793. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Zhao Y, Chou IN. Alterations in cytoskeletal protein sulfhydryls and cellular glutathione in cultured cells exposed to cadmium and nickel ions. Toxicology. 1993;77:65–79. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(93)90138-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, McLeod I, Anderson S, Yates JR, 3rd, He X. Molecular analysis of kinetochore architecture in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2005a;24:2919–2930. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Li PJ, Qi XM, Zhou QX, Zheng L, Sun TH, Yang YS. DNA changes in barley (Hordeum vulgare) seedlings induced by cadmium pollution using RAPD analysis. Chemosphere. 2005b;61:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Yang YS, Zhou Q, Xie L, Li P, Sun T. Impact assessment of cadmium contamination on rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings at molecular and population levels using multiple biomarkers. Chemosphere. 2007;67:1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli A, Rousselet E, Dycke C, Bouron A, Moulis JM. Cadmium toxicity in animal cells by interference with essential metals. Biochimie. 2006;88:1807–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister A. Glutathione metabolism. Methods Enzymol. 1995;251:3–7. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)51106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Cózatl D, Loza-Tavera H, Hernández-Navarro A, Moreno-Sánchez R. Sulfur assimilation and glutathione metabolism under cadmium stress in yeast, protists and plants. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005;29:653–671. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutoh N, Hayashi Y. Isolation of mutants of Schizosaccharomyces pombe unable to synthesize cadystin, small cadmium-binding peptides. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988;151:32–39. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90555-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutoh N, Nakagawa CW, Hayashi Y. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequencing of the gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase gene of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Biochem. 1995;117:283–288. doi: 10.1093/jb/117.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama M, Akashi T, Hase T. Plant sulfite reductase: molecular structure, catalytic function and interaction with ferredoxin. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2000;82:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz DF, Kreppel L, Speiser DM, Scheel G, McDonald G, Ow DW. Heavy metal tolerance in the fission yeast requires an ATP-binding cassette-type vacuolar membrane transporter. EMBO J. 1992;11:3491–3499. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz DF, Ruscitti T, McCue KF, Ow DW. Transport of metal-binding peptides by HMT1, a fission yeast ABC-type vacuolar membrane protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4721–4728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadaki P, Pizon V, Onken B, Chang EC. Two ras pathways in fission yeast are differentially regulated by two ras Guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:4598–4606. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4598-4606.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebernard S, Wohlschlegel J, McDonald WH, Yates JR, 3rd, Boddy MN. The Nse5-Nse6 dimer mediates DNA repair roles of the Smc5-Smc6 complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:1617–1630. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.5.1617-1630.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe S, Marasco SF, Haas SJ, Sheeran FL, Krum H, Rosenfeldt FL. Coenzyme Q10 in cardiovascular disease. Mitochondrion. 2007;7:S154–S167. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego P, Vande Weghe J, Ow DW, Howell SB. Role of determinants of cadmium sensitivity in the tolerance of Schizosaccharomyces pombe to cisplatin. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;51:12–18. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Gabriel MA, Russell P. Distinct signaling pathways respond to arsenite and reactive oxygen species in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:1396–1402. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.8.1396-1402.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiki R, Ogiyama Y, Kainou T, Nishi T, Matsuda H, Kawamukai M. Pleiotropic phenotypes of fission yeast defective in ubiquinone-10 production. A study from the abc1Sp (coq8Sp) mutant. Biofactors. 2003;18:229–235. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520180225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol JH, Shevchenko A, Shevchenko A, Deshaies RJ. Skp1 forms multiple protein complexes, including RAVE, a regulator of V-ATPase assembly. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2001;3:384–391. doi: 10.1038/35070067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serero A, Lopes J, Nicolas A, Boiteux S. Yeast genes involved in cadmium tolerance: Identification of DNA replication as a target of cadmium toxicity. DNA Repair. 2008;7:1262–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki K, Russell P. Cell-cycle control linked to extracellular environment by MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. Nature. 1995;378:739–743. doi: 10.1038/378739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki K, Russell P. Conjugation, meiosis, and the osmotic stress response are regulated by Spc1 kinase through Atf1 transcription factor in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2276–2288. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speiser DM, Ortiz DF, Kreppel L, Scheel G, McDonald G, Ow DW. Purine biosynthetic genes are required for cadmium tolerance in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:5301–5310. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebe H, Yanagida M. Cut8, essential for anaphase, controls localization of 26S proteasome, facilitating destruction of cyclin and Cut2. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00773-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toone WM, Kuge S, Samuels M, Morgan BA, Toda T, Jones N. Regulation of the fission yeast transcription factor Pap1 by oxidative stress: Requirement for the nuclear export factor Crm1 (Exportin) and the stress-activated MAP kinase Sty1/Spc1. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1453–1463. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint M, Conconi A. High-throughput and sensitive assay to measure yeast cell growth: A bench protocol for testing genotoxic agents. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1922–1928. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N, Suzuki K, Saiki R, Kainou T, Tanaka K, Matsuda H, Kawamukai M. Phenotypes of fission yeast defective in ubiquinone production due to disruption of the gene for p-hydroxybenzoate polyprenyl diphosphate transferase. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6933–6939. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.24.6933-6939.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura T, Yanagida M. Isolation of type I and II DNA topoisomerase mutants from fission yeast: Single and double mutants show different phenotypes in cell growth and chromatin organization. EMBO J. 1984;3:1737–1744. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Weghe JG, Ow DW. A fission yeast gene for mitochondrial sulfide oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13250–13257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Weghe JG, Ow DW. Accumulation of metal-binding peptides in fission yeast requires hmt2+ Mol. Microbiol. 2001;42:29–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vomastek T, Schaeffer HJ, Tarcsafalvi A, Smolkin ME, Bissonette EA, Weber MJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:6981–6986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305894101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waalkes MP, Poirier LA. In vitro cadmium-DNA interactions: Cooperativity of cadmium binding and competitive antagonism by calcium, magnesium, and zinc. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1984;75:539–546. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(84)90190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waisberg M, Joseph P, Hale B, Beyersmann D. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cadmium carcinogenesis. Toxicology. 2003;192:95–117. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Templeton DM. Cellular factors mediate cadmium-dependent actin depolymerization. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1996;139:115–121. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood V, Gwilliam R, Rajandream MA, Lyne M, Lyne R, Stewart A, Sgouros J, Peat N, Hayles J, Baker S. The genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature. 2002;415:871–880. doi: 10.1038/nature724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao CQ, Young MR, Diwan BA, Coogan TP, Waalkes MP. Association of arsenic-induced malignant transformation with DNA hypomethylation and aberrant gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:10907–10912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.