Abstract

Background

Celloidin and paraffin are the two common embedding mediums used for histopathologic study of the human temporal bone by light microscopy. Although celloidin embedding permits excellent morphologic assessment, celloidin is difficult to remove, and there are significant restrictions on success with immunostaining. Embedding in paraffin allows immunostaining to be performed, but preservation of cellular detail within the membranous labyrinth is relatively poor.

Objectives/Hypothesis

Polyester wax is an embedding medium that has a low melting point (37°C), is soluble in most organic solvents, is water tolerant, and sections easily. We hypothesized that embedding in polyester wax would permit good preservation of the morphology of the membranous labyrinth and, at the same time, allow the study of proteins by immunostaining.

Methods

Nine temporal bones from individuals aged 1 to 94 years removed 2 to 31 hours postmortem, from subjects who had no history of otologic disease, were used. The bones were fixed using 10% formalin, decal-cified using EDTA, embedded in polyester wax, and serially sectioned at a thickness of 8 to 12 μm on a rotary microtome. The block and knife were cooled with frozen CO2 (dry ice) held in a funnel above the block. Sections were placed on glass slides coated with a solution of 1% fish gelatin and 1% bovine albumin, followed by staining of selected sections with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Immunostaining was also performed on selected sections using antibodies to 200 kD neurofilament and Na-K-ATPase.

Results

Polyester wax–embedded sections demonstrated good preservation of cellular detail of the organ of Corti and other structures of the membranous labyrinth, as well as the surrounding otic capsule. The protocol described in this paper was reliable and consistently yielded sections of good quality. Immuno-staining was successful with both antibodies.

Conclusion

The use of polyester wax as an embedding medium for human temporal bones offers the advantage of good preservation of morphology and ease of immunostaining. We anticipate that in the future, polyester wax embedding will also permit other molecular biologic assays on temporal bone sections such as the retrieval of nucleic acids and the study of proteins using mass spectrometry–based proteomic analysis.

INTRODUCTION

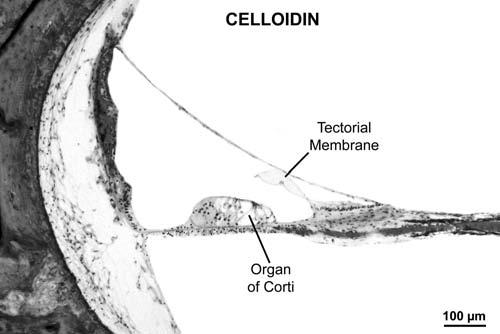

A knowledge of the pathologic basis of the disease is central to the study of medicine, including disorders affecting the auditory and vestibular systems. At the present time, the most commonly used method of preparing the human temporal bone for light microscopy consists of a series of steps that include fixation using formalin, decalcification using ethylenediaminetetracetate (EDTA), embedding using celloidin (purified pyroxylin) followed by serial sectioning and staining of selected sections with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).1 Celloidin has traditionally been the preferred embedding medium because it permits excellent preservation of morphology of the delicate membranous labyrinth (Fig. 1) as well as the surrounding otic capsule and other structures of the human temporal bone.

Fig. 1.

Photomicrograph of lower middle turn of cochlea embedded in celloidin. Note excellent preservation of morphology. Female aged 63 years, postmortem time 8 hours.

The study of proteins at a cellular level by immunostaining and other techniques has the potential to deepen our understanding of the pathophysiology of otologic disorders by providing information that is not available using standard H&E staining. However, the use of fixatives and embedding media, which is necessary for adequate preservation of anatomical structures, can obscure antigens and make it difficult to perform immunostaining and other molecular assays on such sections. Although the standard celloidin technique permits superb preservation for morphologic assessment, it has limitations with respect to immunostaining. It is difficult to remove celloidin completely from tissue sections, and reliable, consistent results have been obtained with only a few antibodies such as Na-K-ATPase.2,3 Other potential disadvantages of the use of celloidin include the length of time needed for embedment (typically 12 weeks for a human specimen) and its relatively high cost (approximately $200 per temporal bone specimen).

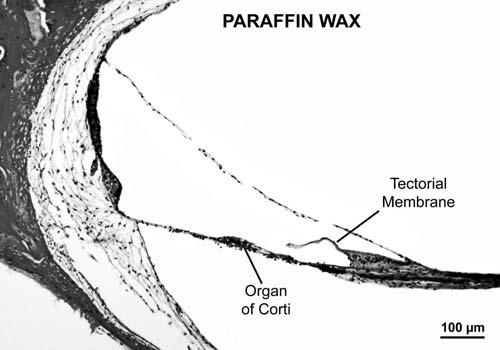

The majority of protocols of immunostaining employed in general pathology make use of frozen tissue or tissue embedded in paraffin wax. A frozen temporal bone has to be either sectioned or decalcified for access to be gained to the membranous labyrinth, which is encased inside the dense, hard petrous bone. There is no practical way of accomplishing sectioning or decalcification while keeping the bone frozen and preserving the morphologic structure of the delicate membranous labyrinth and the surrounding otic capsule. Thus, from a practical point of view, a temporal bone must be fixed, decalcified, embedded and then sectioned as the source of tissue for immunostaining. Temporal bones embedded in paraffin wax exhibit suboptimal morphologic preservation of the delicate membranous labyrinth (Fig. 2). Degradation of tissue morphology is particularly evident within the organ of Corti in paraffin-embedded human specimens, in which severe cell shrinkage makes it difficult to differentiate hair cells from supporting cells. The relatively high melting point of 55°C for paraffin and consequent heat trauma to tissues is believed to be an important factor contributing to poor morphologic preservation.4,5 It is also often necessary to use xylene to clear paraffin during tissue processing for immunostaining. Xylene extracts fats, and the loss of structural lipids may also add to degradation of cell morphology in paraffin embedded tissue. Another frequent problem encountered in the human temporal bone with paraffin embedding is the propensity for artifactual disruptions of the membranous labyrinth such as Reissner membrane and basilar membrane, as the paraffin wax lacks the strength and flexibility to permit proper sectioning of these delicate membranes, which are suspended in fluid-filled spaces.

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph showing lower middle turn of cochlea embedded in paraffin wax. Note suboptimal preservation of cellular detail. There is severe shrinkage of cells of the organ of Corti. There are also artifactual tears of the Reissner membrane and disruptions of some of the fibrocytes within the spiral ligament. Male infant aged 6 months, postmortem time 2 hours.

We recently began to investigate the use of polyester wax as an embedding medium for the histopathologic study of human temporal bones. The various polyester waxes are fatty acid esters of polyethylene glycol.5 Polyethylene glycol 400 distearate was introduced as a new embedding medium for histology by Steedman in 1957.4 The main advantage of polyester wax compared with paraffin wax is its low melting point of 37°C, which avoids heat-induced shrinkage of tissues. Another advantage is that polyester wax is soluble in most organic solvents, including alcohols, ethers, esters, ketones, and other hydrocarbons, and so it is not necessary to use xylene during tissue processing. The wax is water tolerant, is almost opaque, and sections easily at 2 μm to more than 30 μm.5 Polyester wax has been used by several investigators for a variety of studies over the years, including histologic examination of soft tissue,4,5 serial sectioning of specimens containing bone and soft tissue,6 immunohistochemistry and immunostaining,7-10 and in situ hybridization.11 Our colleague, M. Charles Liberman, has successfully used polyester wax embedding for mouse cochleae for light microscopy and for immunostaining using a variety of antibodies (Liberman, personal communication). In his experience, every antibody that has worked in paraffin-embedded tissue or in whole mounts has also worked well, if not better, with polyester wax. We demonstrate in this study that polyester wax permits good preservation of the morphologic structure of the human membranous labyrinth and, at the same time, allows the use of antibodies for immunostaining.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nine sets of temporal bones from individuals aged 1 to 94 years were removed 2 to 31 hours postmortem (mean, 13 h). These individuals had no history of otologic disease on review of their medical charts. The temporal bones were fixed using a mixture of 10% neutral buffered formalin and 1% acetic acid for 2 weeks. Soft tissue and muscle attached to the inferior and anterior aspects of the temporal bones were removed by sharp dissection. The bones were decalcified using 0.27 mol/L EDTA until radiographs showed an absence of calcium (approximately 9 mo). The bones were then trimmed with a razor blade to remove the external auditory canal and most of the mastoid, followed by washing in distilled water and dehydration in graded levels of ethyl alcohol (EtOH), up to 100% EtOH. This was followed by infiltration of each specimen in polyester wax (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA) at 40°C in an infiltration oven. The polyester wax solution was changed every 2 hours for three changes, and the specimen was left overnight in the wax at 40°C. The specimen was then embedded at room temperature the next day and the block was stored in a refrigerator at 4°C. We found that polyester wax has a tendency to stick to metal. Therefore, we used plastic ice cube trays to embed the bones, rather than embedding molds made of metal. For the same reason, we adhered the block to a metal disc to secure it into the microtome, instead of the usual plastic embedding cassette.

The polyester wax-embedded temporal bone was mounted on a rotary microtome with a metal chuck. Solid CO2 (dry ice) was held in a funnel about 6 inches above the block so as to chill the block and knife during sectioning. Serial sections were cut at a thickness of 8 to 12 μm each. The cut sections were separated using smooth, Teflon-coated forceps and Teflon-coated razor blades. Glass slides were coated with a solution of 1% fish gelatin10 and 1% bovine albumin to adhere the sections to the slides. A drop of ice-cold distilled water was placed on each slide. Each section was placed onto the drop of water and allowed to stretch out onto the slide for 15 to 60 seconds. Each slide was then turned vertically to drain the water. Each slide was then placed flat and allowed to dry on a warming plate at 30°C over night. The sections were then stored in boxes at room temperature.

Selected sections were stained as follows. The sections were dewaxed using 100% EtOH for 10 minutes followed by air drying for 15 minutes. The 100% EtOH and air drying cycle was repeated. This was followed by hydration of the sections in decreasing strengths of EtOH using 90% EtOH for 2 minutes (for two cycles) followed by 70% EtOH for two minutes (for two cycles) and then distilled water for 2 minutes. Staining was then performed with H&E.

Immunostaining was also performed using antibodies to 200 kD neurofilament (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) and Na-K-ATPase (J. Siegel). These particular antibodies were selected to test the feasibility of immunostaining on polyester wax sections, since we knew from past experience that both antibodies worked reasonably well in paraffin-embedded human and animal cochleae. All steps were performed at room temperature. Selected slides were dewaxed using 100% EtOH as described above, rehydrated in decreasing strengths of EtOH, followed by distilled water, and rinsed in a 0.01 mol/L phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.3). The next step was incubation in 1% normal horse serum for 60 minutes to block nonspecific immunoglobulin binding. The horse serum was drained; no rinsing was done. The primary antibodies were then added to the sections (dilution of 1:1000 for Na-K-ATPase and 1:2000 for neurofilament) and left overnight in an incubation chamber. The primary antibodies were then drained and the slides rinsed three times in PBS, followed by addition of a biotinylated secondary antibody and incubation for 1 hour. After three washes in PBS (5 min each), avidin-biotinhorseradish peroxidase (Standard ABC Kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.) was applied for 1 hour, followed by three additional washes in PBS for 5 minutes each. The slides were colorized using 0.01% diaminobenzidine and 0.01% H2O2 for approximately 5 to 10 minutes under microscopic control, washed in PBS and water, and dehydrated, and cover slips were applied.

RESULTS

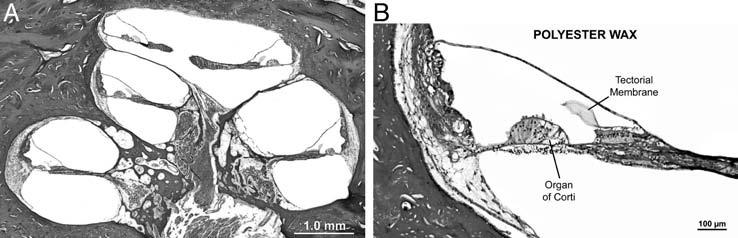

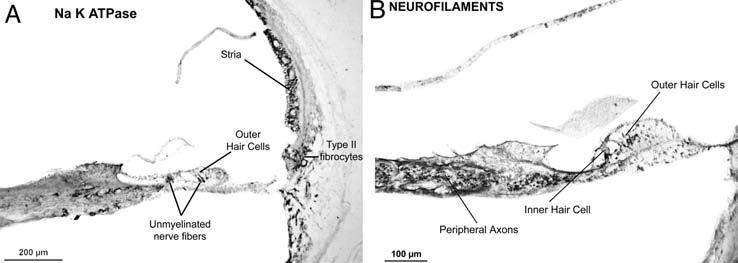

The protocol described above was reliable and consistently yielded sections embedded in polyester wax that were of good quality. Figure 3 shows a typical midmodiolar section at low and high power. As is evident, there was good preservation of cellular detail, including the ability to differentiate hair cells, supporting cells, pillar cells, and so on within the organ of Corti. Similarly, the protocol used for immunostaining yielded positive staining in the expected locations, based on past experience, as shown in Figure 4.

Fig. 3.

(A) Low-power photomicrograph of mid-modiolar section of cochlea that was embedded in polyester wax. Female aged 71 years, postmortem time 14 hours. (B) Photomicrograph of lower middle turn of cochlea embedded in polyester wax, same case as shown in part A. Note that the preservation of cellular detail of various structures of the organ of Corti and scala media is quite good.

Fig. 4.

(A) Immunostaining of cochlea embedded in polyester wax using antibody against Na-K-ATPase. Positive staining is seen within the stria vascularis, type II fibrocytes of the spiral ligament, and unmyelinated nerve endings under outer and inner ear hair cells of organ of Corti. Newborn male, postmortem time 2 hours. (B) Immunostaining of cochlea embedded in polyester wax using antibody to 200 kD neurofilament protein. Positive staining is seen for peripheral axons within the osseous spiral lamina and the nerve terminals under the outer and inner hair cells. Female aged 76 years, postmortem time 7 hours.

We found it necessary to occasionally re-embed the tissue when sectioning was not proceeding smoothly, for example, when there were air bubbles trapped within the inner ear. Re-embedding was done overnight using fresh polyester wax. We found that re-embedding usually corrected the problem, with minimal damage to the membranous labyrinth. This is unlike the case with both celloidin and paraffin, in which re-embedding typically results in significant artifacts, including disruption of membranes and other structures within the inner ear.

We encountered some difficulty in getting the polyester wax sections to adhere to slides. The best results were obtained by coating glass slides with 1% fish gelatin and 1% bovine albumin, as described above. A number of other techniques were tried but were unsuitable, including the use of “plus” slides, double-subbed slides (gelatin and chromium alum), biobond, poly-l-lysine, various concentrations of pig gelatin, a solution of glycerine and albumin, tissue tack adhesive, and a solution of fish gelatin and bovine gelatin.

We were able to successfully cut sections from a block that contained the cochlea, the vestibular sense organs, and the surrounding otic capsule. It was difficult to obtain sections from larger blocks that included the external auditory canal, middle ear, and mastoid (in addition to the inner ear). Attempts to section such large blocks resulted in excessive cutting artifact due to tears and distortions of the bony and membranous tissues. This limit on the size of the tissue block is probably due to constraints imposed by the combination of a rotary microtome, a thin, disposable razor blade, and the nature of the embedding medium. A similar constraint on size of the block exists with paraffin embedding of human temporal bones.

DISCUSSION

The two commonly used embedding media for processing human temporal bones are celloidin and paraffin. Embedding in celloidin permits excellent morphologic preservation of the membranous and bony labyrinth, but celloidin is difficult to remove, and this adds to restrictions on success with immunostaining. Celloidin is also relatively expensive and requires an extended period of time for embedment to occur. Embedment in paraffin wax permits immunostaining with many antibodies, but preservation of cellular detail within the inner ear is suboptimal.

We have found that the use of polyester wax as an embedding medium offers the advantage of good preservation of morphologic structure and ease of immunostaining. These advantages stem from its low melting point of 37°C, which obviates heat-induced tissue artifacts, and from the fact that polyester wax is easily extracted since it is miscible with most organic solvents. Polyester wax is also less expensive than celloidin (approximately $25 per temporal bone) and embedment of a temporal bone can occur within 2 to 3 days. Another significant advantage of polyester wax (compared to both celloidin and paraffin) is the ease of re-embedding the specimen with minimal trauma to the tissue. One limitation with polyester wax is the relatively small size of the block, such that we have not yet been successful in sectioning the entire temporal bone with the contained, external, middle, and inner ears and the mastoid. It may be possible to overcome the size limitation with the use of different microtomes and cutting blades.

We are increasingly using polyester wax as an embedding medium for processing newly acquired temporal bones in our laboratory. When we acquire a pair of temporal bones that are predicted to have identical pathologic conditions (based on the clinical history and test data) such as genetic deafness, ototoxicity, presbycusis, or acoustic trauma, we prepare one ear for standard light microscopy in celloidin and the opposite ear is processed in polyester wax. We are also employing polyester wax embedding for temporal bones predicted to have unilateral or dissimilar pathologies, when there is an important research question that can be answered by immunostaining and sufficient numbers of specimens have been processed by the standard celloidin technique so as to have a good idea of the light microscopic pathologic finding (e.g., otitis media, otosclerosis).

We believe that embedding temporal bones in polyester wax will also be of value in applying other molecular biologic assays to temporal bone research in the future. One example is the retrieval of nucleic acids such as DNA, which has been accomplished in the past from celloidin-embedded material with varying degrees of success.12-17 Another potential application is the study of proteins at a cellular and molecular level by the application of mass-spectrometric techniques. We have recently shown the ability to successfully perform proteomic analysis using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry on human temporal bones that were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin.18 The preservation of good morphology of various structures of the labyrinth in polyester wax sections means that one can target specific regions of interest such as the hair cells or supporting cells and microdissect these small areas by laser capture techniques and subject them to proteomic analysis. The study of proteins in individual cells or groups of cells in this manner has the potential to transform our understanding of the pathophysiology of many otologic disorders.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The two commonly used embedding media for processing human temporal bones, celloidin and paraffin, have certain limitations. Although celloidin permits excellent morphologic preservation of tissues, it is difficult to remove and poses significant problems when attempts are made to immunostain such sections. Embedment in paraffin wax allows immunostaining, but the preservation of cellular detail within the membranous labyrinth is suboptimal. In this study, we describe the use of a new embedding medium, polyester wax, for the histopathologic study of human temporal bones. Polyester wax has a low melting point of 37°C, thus allowing infiltration and embedding without heat-induced artifacts, resulting in good preservation of inner ear morphology. Polyester wax is miscible with most organic solvents and is readily extracted and, thus, immunostaining can be performed with ease. It is also possible to re-embed bones with polyester wax without incurring significant artifacts. We conclude that the use of polyester wax as an embedding medium for human temporal bones has the potential to permit good preservation of morphology and the ability to study proteins at a cellular and molecular level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Connie Miller and M. Charles Liberman, PhD, for their assistance in developing the technique using polyester wax for embedding human temporal bones. We are also grateful to Mr. Axel Eliasen for his generous support.

References

- 1.Schuknecht HF. Pathology of the Ear. 2nd edition Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keithley EM, Horowitz S, Ruckenstein MJ. Na,K-ATP-ase in the cochlear lateral wall of human temporal bones with endolymphatic hydrops. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104:858–863. doi: 10.1177/000348949510401106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian Q, Linthicum FH, Jr., Keithley EM. Application of labeling techniques to archival temporal bone sections. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:47–53. doi: 10.1177/000348949910800107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steedman HF. Polyester wax: a new ribboning embedding medium for histology. Nature. 1957;4574:1345. doi: 10.1038/1791345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sidman RL, Mottla PA, Feder N. Improved polyester wax embedding for histology. Stain Technology. 1961;36:279–284. doi: 10.3109/10520296109113291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baird IL. Polyester wax as an embedding medium for serial sectioning of decalcified specimens. Am J Medical Technology. 1967;33:394–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alho AM, Underhill CB. The kyaluronate receptor is preferentially expressed on proliferating epithelial cells. J Cell Biology. 1989;108:1557–1565. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.4.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusakabe M, Sakakura T, Nishizuka Y. Polyester wax embedding and sectioning technique for immunohistochemistry. Stain Technology. 1984;59:127–132. doi: 10.3109/10520298409113845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oke BO, Suarez-Quian CA. Localization of secretory, membrane-associated and cytoskeletal proteins in rat testis using an improved immunocytochemical protocol that employs polyester wax. Biology Reproduction. 1993;48:621–631. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.3.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitha S, Baluška F, Jasik J, et al. Steedman's wax for F-actin visualization. In: Staiger CJ, Baluska F, Volkmann D, Barlow PW, editors. Actin: A Dynamic Framework for Multiple Plant Cell Functions. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2000. pp. 557–572. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shutlesworth GA, Mills N. Section adherence to glass slides from polyester wax-embedded tissue for in situ hybridization. Biotechniques. 1995;18:948–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wackym PA, Simpson TA, Gantz BJ, Smith RJH. Polymerase chain reaction amplification of DNA from archival celloidin-embedded human temporal bone sections. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:583–588. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199306000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKenna MJ, Kristiansen A, Haines J. Isolation and identification of nucleic acid sequences from celloidin and paraffin embedded human temporal bone sections. In: Mogi G, Veldman JE, Kawauchi H, editors. Proceedings of the 4th International Academic Conference; Oita, Japan. Apr 4-7; New York: Kugler; 1994. pp. 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenna MJ, Kristiansen AG, Tropitzsch A, et al. Deoxyribonucleic acid contamination in archival human temporal bones: a potentially significant problem. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:789–792. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200209000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson TA, Smith RJG. Amplification of mitochondrial DNA from archival temporal bone specimens. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:28–34. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidman MD, Bai U, Khan MJ, et al. Association of mitochondrial DNA deletions and cochlear pathology: a molecular biologic tool. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:777–783. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199606000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischel-Ghodsian N, Bykhovskaya Y, Taylor K, et al. Temporal bone analysis of patients with presbycusis reveals high frequency of mitochondrial mutations. Hear Res. 1997;110:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer-Toy DE, Krastins B, Sarracino D, et al. An efficient method for the proteomic analysis of fixed and embedded tissues. J Proteome Research. 2005 doi: 10.1021/pr050208p. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]