Abstract

Most 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS) patients have middle and outer ear anomalies, whereas some have inner ear malformations. Tbx1, a gene hemizygously deleted in 22q11DS patients and required for ear development, is expressed in multiple tissues during embryogenesis. To determine the role of Tbx1 in the first pharyngeal pouch (PPI) in forming outer and middle ears, we tissue-specifically inactivated the gene using Foxg1-Cre. In the conditional mutants, PPI failed to outgrow, preventing the middle ear bone condensations from forming. Tbx1 was also inactivated in the otic vesicle (OV), resulting in the failure of inner ear sensory organ formation, and in duplication of the cochleovestibular ganglion (CVG). Consistent with the anatomical defects, the sensory genes, Otx1 and Bmp4 were downregulated, whereas the CVG genes, Fgf3 and NeuroD, were upregulated. To delineate Tbx1 cell-autonomous roles, a more selective ablation, exclusively in the OV, was performed using Pax2-Cre. In contrast to the Foxg1-Cre mutants, Pax2-Cre conditional mutant mice survived to adulthood and had normal outer and middle ears but had the same inner ear defects as the Tbx1 null mice, with the same gene expression changes. These results demonstrate that Tbx1 has non-cell autonomous roles in PPI in the formation of outer and middle ears and cell-autonomous roles in the OV. Periotic mesenchymal markers, Prx2 and Brn4 were normal in both conditional mutants, whereas they were diminished in Tbx1−/− embryos. Thus, Tbx1 in the surrounding mesenchyme in both sets of conditional mutants cannot suppress the defects in the OV that occur in the null mutants.

INTRODUCTION

DiGeorge/Velo-cardio-facial/22q11 deletion syndrome (22q11DS) is one of the most common microdeletion disorders, characterized by severe malformations in the derivatives of the pharyngeal apparatus (1). The clinical phenotype includes ear defects, craniofacial abnormalities, thymus and parathyroid gland hypoplasia and outflow tract heart malformations (2,3). Most patients have external ear defects, chronic otitis media and hearing impairment (3-5). The hearing loss is primarily conductive and correlates well with the presence of chronic otitis media, which is found in the majority of patients. However, 10% of the cases of hearing loss is of the sensorineural type, indicating that at least some patients have inner ear defects (6).

The vertebrate ear develops as a result of complex tissue interactions during embryogenesis (7). The outer (pinna) and middle ear develop as a result of interactions between cells in pharyngeal arches I (PA I) and II (PA II) and the migrating neural crest cells (NCCs) (7). The pinna forms as a result of fusion of PA I and II. The middle ear, consisting of the external auditory meatus and tubotympanic recess, and the middle ear ossicles (malleus, incus, stapes) derives from the first pharyngeal pouch (PPI) endoderm and NCC mesenchyme, respectively (8-11).

The inner ear, encompassing the sensory organs, including the cochlea and the vestibular system as well as the cochleovestibular ganglion (CVG), is derived from the otic vesicle (OV), which arises from the surface ectoderm (7). The inner ear sensory organs thus share a common embryonic origin with the primary sensory neurons that innervate the hair cells.

Despite the requirement for precise genetic control throughout ear development, mutations in only a handful of genes result in complete aplasia of inner, middle and outer ear structures (8,9). Tbx1, a member of the T-box gene family of transcription factors, is one of the few known essential genes (10,11). Mutations in T-box genes result in variety of human congenital malformations; TBX1 haploinsufficiency has been implicated in the etiology of 22q11DS (12-15). As aforementioned, most 22q11DS patients have ear disorders including chronic otitis media with associated conductive hearing loss, while inner ear and cranial ganglion dysplasias have also been described in patients with this syndrome (6,8,9).

In mice, Tbx1 homozygous mutations result in failure of middle and outer ear development and in early gestational arrest of OV morphogenesis, leading to hypoplasia of inner ear sensory organs (10,11). Tbx1−/− embryos lack the cochlea and the vestibular system, as the inner ear never develops past a rudimentary cystic structure. In contrast, the CVG primordium is expanded in Tbx1−/− mice, suggesting that Tbx1 is required for sensory organ development and for suppression of neural cell fate determination in the OV (10). These studies propose that Tbx1 acts to promote sensory organ fates through regulation of Bmp4 and Otx1 (10). In contrast, Tbx1 negatively regulates Ngn1 and NeuroD, two genes that specify neural fates, as well as Fgf3 and Lunatic fringe (Lfng), markers of presumptive anterior otocyst neural competence (10).

During early ear development, Tbx1 is expressed in the posterior half of the OV (10,11,16), in a complementary manner to the region from which neural precursors delaminate (10). Tbx1 is also expressed in the periotic mesenchyme (PM) surrounding the OV, the pharyngeal pouch endoderm, pharyngeal arch mesenchyme, as well as additional sites of epithelial–mesenchymal interactions (17). However, it remains unclear whether the otic epithelial domain of Tbx1 expression is sufficient to induce ear morphogenesis and whether the PM cells expressing Tbx1 play a role in sensory organ formation and in suppression of neural cell fates.

In order to determine the precise role of Tbx1 in middle ear and OV morphogenesis, we used the Cre/loxP strategy to conditionally inactivate the gene in the pharyngeal endoderm and OV, while leaving the mesenchymal domains of expression intact. Our results show that complete ablation of Tbx1 in the OV and in the pharyngeal pouch endoderm causes an ear phenotype identical to that of Tbx1 homozygous null mutants. This includes absence of outer and middle ears because of failed expansion of the PPI. It also includes failure to form inner ear sensory organs, coupled with an expansion of the CVG rudiment. Furthermore, OV-specific ablation of Tbx1 with Pax2-Cre results in a similar inner ear phenotype, whereas outer and middle ear formation remains unaffected. Thus, our experiments show that Tbx1 in the OV has cell-autonomous roles in patterning the inner ear. Moreover, this study shows that Tbx1 in the PM is not sufficient to suppress inner ear defects in the mutant embryos, suggesting that the gene has a distinct role in each tissue. Finally, these results suggest that TBX1 may contribute to the etiology of middle and inner ear malformations observed in 22q11DS patients.

RESULTS

Conditional mutagenesis of Tbx1

Tbx1 is expressed in the OV and the PM, as well as in the pharyngeal pouch endoderm and the core mesoderm of the pharyngeal arches (10,11,14,17). It is also expressed transiently at E9.0 in the ectoderm of the distal pharyngeal apparatus (16,18). To determine the tissue-specific roles of Tbx1 in ear development, we have used mice containing the previously described Tbx1 conditional allele (Tbx1 flox) (19). When crossed to a tissue-specific Cre recombinase mouse strain, the floxed allele in Tbx1 flox/flox mice recombines to produce a Tbx1 null allele (Fig. 1A) (19). To assess the role of Tbx1 in the epithelial tissues involved in ear development, we used two distinct Cre recombinase strains, Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre (Fig. 1B) (20,21). In order to confirm the recombination pattern induced by the two Cre strains, we crossed Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre mice with the ROSA26 reporter strain (22) and compared findings with endogenous Tbx1 expression (Fig. 2A and B). As previously described (21), by E9.5 Foxg1-Cre-induced recombination is evident in the telencephalon, the otic and optic vesicles and in the pharyngeal pouch endoderm (Fig. 2C). The first pouch endoderm (PPI) forms the auditory tube and contributes, via tissue interactions, to the formation of the middle and outer ear. Stage-matched Pax2-Cre embryos show Cre expression in the OV (Fig. 2C). In contrast to the Foxg1-Cre mice (Fig. 2C), Cre is not expressed in PPI in Pax2-Cre mice (Fig. 2E and H).

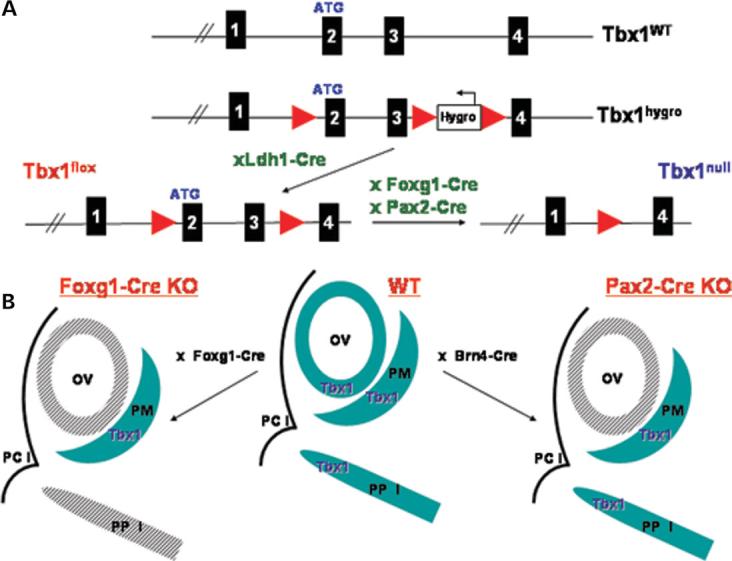

Figure 1.

(A) Generation of the Tbx1 conditional mutant mice. Genomic structure of the Tbx1 WT locus from exon 1 to 4 is shown on top. Standard gene targeting techniques were used to generate the Tbx1 hygro allele by inserting a single loxP site between exons 1 and 2 and a Hygromycin resistance cassette between exons 3 and 4. The Tbx1hygro/ + mice were mated with Ldh1-Cre mice to delete the Hygromycin resistance cassette and generate the Tbx1 flox/+ mice. Tbx1 floxed mice were crossed to Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre mice to produce the Tbx1 conditional mutant mice, containing the Tbx1 null allele shown on the right. (B) Strategy to generate tissue-specific Tbx1 mutants. In WT embryos Tbx1 is expressed in both the OV and the surrounding PM, as well as in the PPI. Tbx1 expression is shown in blue. The Foxg1-Cre (left) and Pax2-Cre (right) strains mediate Tbx1 inactivation in the OV (shaded grey) while the PM expression domain remains intact. The Foxg1-Cre strain also mediates inactivation of Tbx1 in the PPI (shown in shaded grey). PCI, first pharyngeal cleft; Foxg1-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox;Foxg1-Cre/+, Pax2-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Pax2-Cre tg.

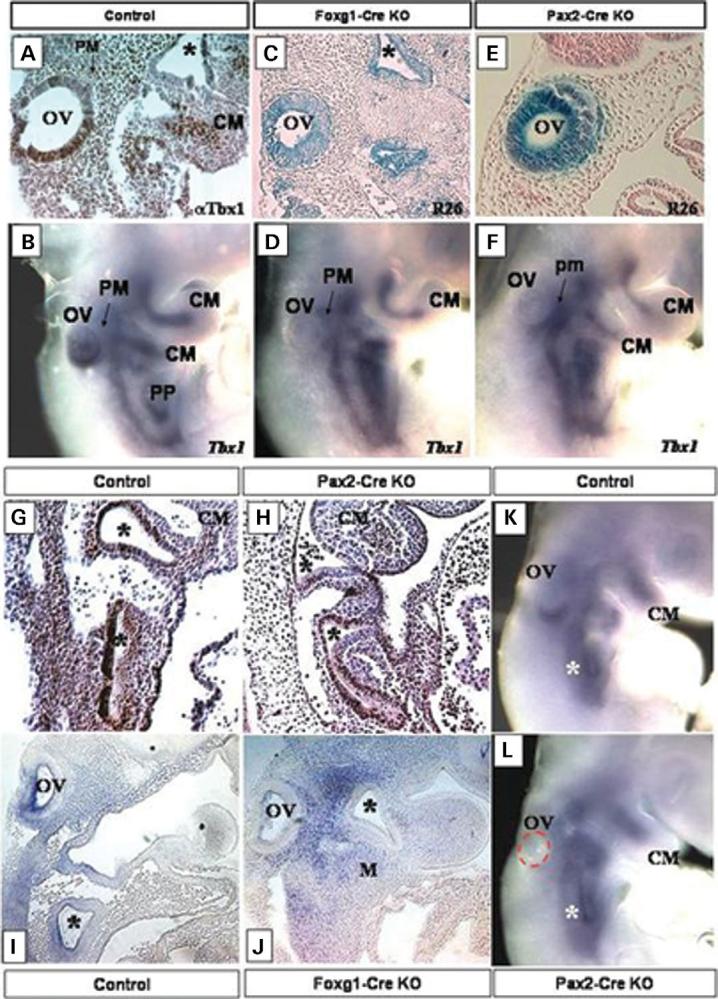

Figure 2.

Tbx1 expression in E9.5 control embryos shown by IHC on sagittal sections with a Tbx1 polyclonal antibody (A) and by whole mount ISH with Tbx1 (B). Note Tbx1 expression in the OV, the pharyngeal pouches (PP, asterisks) and in the periotic mesenchyme (PM) and the core mesoderm of the pharyngeal arches (CM) in (A and B). Foxg1-Cre (C) and Pax2-Cre (E) activity shown by x-gal staining (lacZ) on E9.5 sagittal sections of Foxg1-Cre/ROSA26 (R26) and Pax2-Cre/ROSA26 (R26) progeny. Both Cre strains are active in the OV, while the Foxg1-Cre strain is also active in the pharyngeal pouches (stars in C). (D and F) Tbx1 expression by ISH in E9.5 Tbx1 conditional null mutant embryos, generated with the Foxg1-Cre strain (Foxg1-Cre KO) (D) and with the Pax2-Cre strain (Pax2-Cre KO) (F). Tbx1 is inactivated in the OV of both sets of mutants (OV in D and F), while the core mesoderm (CM) expression domain is still present. Tbx1 expression by IHC with a polyclonal Tbx1 antibody on E9.5 control (G) and Pax2-Cre KO (H). Note Tbx1 expression in the pharyngeal pouches (asterisks), and in the core mesoderm (CM). G and H are sagittal sections. ISH with Tbx1 on E9.5 sagittal sections of control (I) and Foxg1-Cre KO embryos (J). Note that Tbx1 expression is gone from the OV, and pharyngeal pouches (asterisks) of the Foxg1-Cre KO embryo (J). ISH with Tbx1 on E9.0 control (K) and Pax2-Cre KO mutant (L). Tbx1 expression is evident in the ventral OV in the control (K), but is absent in the Pax2-Cre KO mutant (L). The OV in the Pax2-Cre KO mutant (L) has been outlined with a red dashed line. Tbx1 is still present in the pharyngeal pouches (asterisks) of the mutant (L). Foxg1-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Foxg1-Cre/+, Pax2-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Pax2-Cre tg.

Generation of the Tbx1 conditional null mutant mice (Tbx1nul/floxl;Foxg1-Cre/+ referred to as Foxg1-Cre KO) using the Foxg1-Cre strain has been previously described (Fig. 1) (19). To produce Pax2-Cre-driven conditional null mutants, termed Pax2-Cre KO, we crossed the Tbx1 flox/flox mice to mice heterozygous for Tbx1 but also carrying the Pax2-Cre transgene (Tbx1null/flox;Pax2-Cre tg). The resulting conditional null offspring, generated using either Cre strain, are heterozygous for the Tbx1 null allele in all tissues but homozygous for the null allele in tissues expressing Cre recombinase (Fig. 1). Tbx1 heterozygosity is associated with chronic otitis media but not morphological defects, and does not interfere with the formation of the outer, middle and inner ear structures (23).

To verify that Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre strains ablated Tbx1 in the correct spatial and temporal manner, we analyzed Tbx1 expression in control and conditional mutant embryos by in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC; Fig. 2). By E9.5, Tbx1 expression in the OV is lost in the Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre KO embryos, whereas the PM expression domain remains intact (Fig. 2D, F, H, J). In addition, in the Foxg1-Cre KO embryos, Tbx1 is inactivated in PPI (19) (Fig. 2J). Control embryos of the same stage (Tbx1 null/+; Cre) show the previously described normal pattern of Tbx1 expression (Fig. 2A, B, I). To further verify that the Pax2-Cre strain did not inactivate Tbx1 in PPI, we performed IHC with a Tbx1 polyclonal antibody (Fig. 2G and H). By E9.5, Tbx1 expression is evident in the core mesoderm and in PPI of both control (Fig. 2G and I) and Pax2-Cre KO embryos (Fig. 2H). Furthermore, to ensure that the Pax2-Cre strain inactivated Tbx1 in the OV prior to its onset of expression, we performed ISH on E9.0 control and Pax2-Cre embryos (Fig. 2K and L). By this stage, Tbx1 is already expressed in the ventral part of the developing OV (Fig. 2K); however, Pax2-Cre KO mutants of the same stage show no Tbx1 expression in the OV (Fig. 2L). Importantly, the pharyngeal pouch Tbx1 expression is already evident in the same embryo (Fig. 2L), demonstrating that although both the Pax2-Cre and Foxg1-Cre strains inactivate Tbx1 in the OV, only Foxg1-Cre mediates Tbx1 ablation in the pharyngeal endoderm.

As previously reported, Tbx1 conditional null embryos generated with the Foxg1-Cre strain do not survive embryogenesis and die in the perinatal period (E18.5–E20.5) with multiple malformations of the pharyngeal apparatus (19). To assess viability of the Pax2-Cre KO mice, we performed Mendelian ratio analysis of P10 progeny from Tbx1 flox/flox and Tbx1 null/+; Pax2-Cre tg crosses. Our results show that Pax2-Cre KO embryos survive in normal Mendelian ratios through adulthood (n > 100). Histological analysis of tissue sections revealed no anatomical defects besides the inner ear (data not shown; E17.5; n = 8).

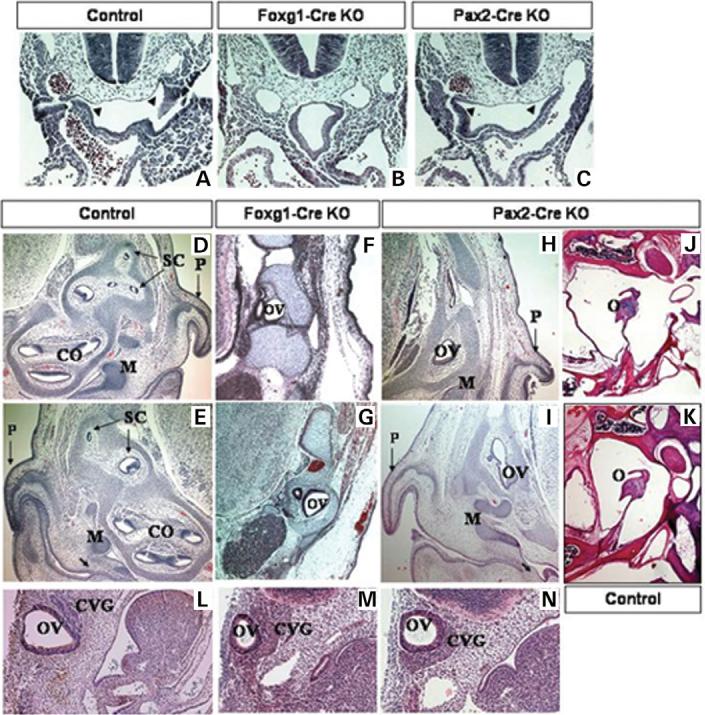

Tbx1 in the pharyngeal endoderm is required to form the auditory tube, middle and outer ear

The Foxg1-Cre strain, congenic in the Swiss-Webster (SW) genetic background, inactivates Tbx1 exclusively in PP endoderm, but not in the mesodermal tissues (Fig. 2C and D). We analyzed the morphogenesis of the outer and middle ear in Foxg1-Cre KO mutants. Foxg1-Cre KO mutants first show defects in middle ear formation at E10.5. At this stage, the pharyngeal endoderm of control embryos (Tbx1 null/+; Cre) starts to invaginate toward the surface endoderm to form the tubotympanic recess (Fig. 3A). However, the endodermal cells of the Foxg1-KO embryos fail to invaginate, resulting in a disruption of middle ear development (Fig. 3B). To assess later ear development, we analyzed E15.5–E17.5 mutant embryos. Neither the pinna nor the middle ear ossicles start the condensation process and thus fail to develop in Foxg1-Cre KOs or Tbx1−/− embryos, demonstrating that Tbx1 in PPI is required for morphogenesis of the middle and outer ear structures (Fig. 3F and G).

Figure 3.

E10.5 transverse histological sections of control (A), Foxg1-KO (B) and Pax2-Cre KO (C) embryos. The invaginating pharyngeal endoderm in control (A) and Pax2-Cre KO (C) embryos is denoted with arrowheads. E17.5 transverse histological sections of control (D and E), Foxg1-Cre KO conditional mutants (F and G) and Pax2-Cre KO (H and I) embryos. Note the presence of the nascent tympanum in controls (E) and Pax2-Cre KOs (I), denoted by an arrow, and the middle ear bones (M), as opposed to Foxg1-Cre KOs (F,G). Horizontal histological sections of adult conditional mutant Pax2-Cre KO (J) and control (K) mice show the presence of normal middle ear structures in mutants (J). Sagittal histological sections of E10.5 control (L), Foxg1-Cre (M) and Pax2-Cre (N) mutant embryos. Early OV development is normal in both sets of mutant embryos, but the structure is slightly hypoplastic by E10.5 (M and N). The CVG is also enlarged in both Foxg1-Cre (M) and Pax2-Cre (N) mutants, when compared with a control embryo (L). CO, cochlea, SC, semicircular canals, P, pinna, O, ossicles (middle ear), Control, Tbx1+/−, Foxg1-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Foxg1-Cre/+, Pax2-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Pax2-Cre tg.

In addition to the outer and middle ear defects, E17.5 Foxg1-KO embryos have a hypoplastic ear capsule, as well as severe malformations of craniofacial bone structures (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1C and D). As Tbx1 is not expressed in NCCs, which give rise to craniofacial bones, these defects arise non-cell-autonomously as a consequence of Tbx1 inactivation in the pharyngeal pouches.

In contrast to the Foxg1-Cre promoter, Pax2 does not drive Cre expression in PPI and E10.5 Pax2-Cre KO embryos show normal development of the future tubotympanic recess (Fig. 3C). As Tbx1 expression is normal in this tissue in Pax2-Cre KO mutants (Fig. 2L), normal middle and outer ear structures proceed to form in E17.5 Pax2-Cre KO embryos (Fig. 3H and I) and adult mice (Fig. 3J). The middle ear ossicles and pinnae are clearly evident in E17.5 Pax2-Cre KO (Fig. 3H and I), as compared with the Foxg1-Cre KO mice (Fig. 3F and G). Adult Pax2-Cre KO mice (Fig. 3J) also show normal development of the middle ear structures. Furthermore, formation of the ear capsule and the craniofacial bones is normal in E17.5 Pax2-Cre KO embryos, because of the presence of Tbx1 expression in PPI (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1 E and F).

As compared with the Foxg1-Cre KOs, Pax2-Cre KO mice survive normally through adulthood (n > 100). To assess adult Pax2-Cre KO mutants for hearing defects, we performed auditory brainstem response (ABR) testing. As predicted, based on the loss of sensory structures, 3/5 mutants analyzed (n = 5) have no hearing on either the left or right side as compared with control littermates (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). Normal hearing in two Pax2-Cre KO mutants is consistent with the incomplete penetrance of the inner ear phenotype observed at E17.5. We found that 12/16 ears show complete failure of inner ear development, whereas the rest appear completely normal. The sensorineural hearing loss in 10–15% of 22q11DS patients (6,19), may result from abnormal TBX1 expression in the OV, as well.

Tbx1 expression in the OV is required for sensory organ formation

To assess embryonic development of the inner ear in Foxg1-Cre KO embryos, we analyzed E17.5 histological sections of mutant and control (Tbx1 null/+; Cre) embryos. By this stage, the control embryos have clear precursors of all major structures (Fig. 3D and E). The cochlea, the utricle, saccule and the semicircular canals are all clearly evident (Fig. 3D and E). In contrast, the Foxg1-Cre KO embryos show severe hypoplasia of the inner ear, developing only a cystic OV and endolymphatic duct, with complete aplasia of the sensory organs (Fig. 3F and G, data not shown). The defects in the conditional mutants are identical to those in the Tbx1−/− embryos. However, it remains unclear whether inactivation of Tbx1 in PPI plays a significant role in disrupting inner ear development.

To further determine the precise role of Tbx1 solely in the OV, we used the Pax2-Cre strain to inactivate the gene in this tissue. In order to assess embryonic development of the ear, we examined Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre KO embryos as well as controls (Tbx1+/−; Cre) at E10.5–E17.5. The OV was present in both sets of mutant embryos, however, in both, it is smaller and surrounded by an expanded CVG, similar to the phenotype of Tbx1−/− embryos (Fig. 3L-N and Fig. 4). A total of 6/8 Pax2-Cre mutant embryos analyzed had a severely hypoplastic inner ear, identical to the Foxg1-Cre KOs (Fig. 3H and I). The severe hypoplasia was bilateral and present in 12/16 ears. In these mutants, the cochlea and the vestibular system never develop and the inner ear persists in a rudimentary OV stage. These results demonstrate that inner ear sensory organ formation requires Tbx1 expression within cells of the OV and that inner ear dysplasia is independent of Tbx1 activity in PPI.

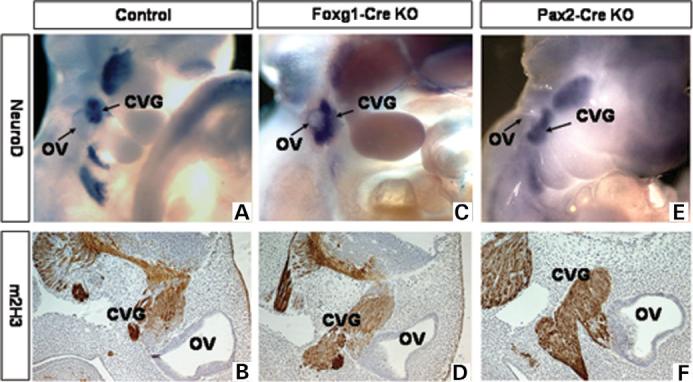

Figure 4.

Development of the CVG in E10.5–E11.5 control (A and B), Foxg1-Cre KO (C and D) and Pax2-Cre KO (E and F) embryos. Whole-mount ISH with a NeuroD probe on E10.5 embryos (A, C and E). IHC with a monoclonal m2H3 anti-neurofilament antibody on E11.5 sagittal sections (B, D and F). Control, Tbx1+/−, Foxg1-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Foxg1-Cre, Pax2-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Pax2-Cre tg.

Reciprocal functions of Tbx1 in the OV

In addition to hypoplasia of the inner ear sensory structures, homozygous null Tbx1 mutants (Tbx1−/−) have an expanded CVG rudiment (10). To determine if inactivation of Tbx1 exclusively in the OV is sufficient to reproduce CVG defects, we examined the expression pattern of NeuroD, a marker of committed neural precursors, and found that it was expanded in both the Foxg1-Cre (Fig. 4C) and Pax2-Cre (Fig. 4E) KO mutant embryos at E10.5. To assess later stages of CVG development, we used the anti-neurofilament monoclonal 2H3 antibody (m2H3) (Fig. 4B, D, F). As in the Tbx1−/− mutants, the CVG at E11.5 is duplicated around the OV anterior–posterior midline in both Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre conditional mutants (Fig. 4E and F). These results suggest that Tbx1 expressed by cells of the OV represses neurogenesis either locally through cell–cell interactions or cell-autonomously, and that this activity is separable from Tbx1's role in middle and outer ear morphogenesis. These findings are also consistent with the role of Tbx1 in the etiology of 22q11DS, as VIIIth cranial ganglion dysplasia has been inferred in human patients with the syndrome on the basis of hearing loss (24-26).

Tbx1 has been implicated as the determinant of anterior–posterior patterning in the OV (10). In that study, Tbx1 loss of function mutation was shown to cause anterior (neurogenic) transformation of posterior OV regions that normally contributes to sensory organ development. In Tbx1−/− embryos Fgf3, which normally co-localizes with neural bHLH gene expression in the anterior OV (Fig. 5A), is ectopically expressed in the posterior OV. In contrast, expression of Otx1, a gene essential for sensory organ development and expressed in the posterior OV (Fig. 5D) is absent in Tbx1−/− embryos (10). However, it remains unclear if the PM domain of expression of Tbx1 plays a role in establishing the anterior–posterior boundary in the OV.

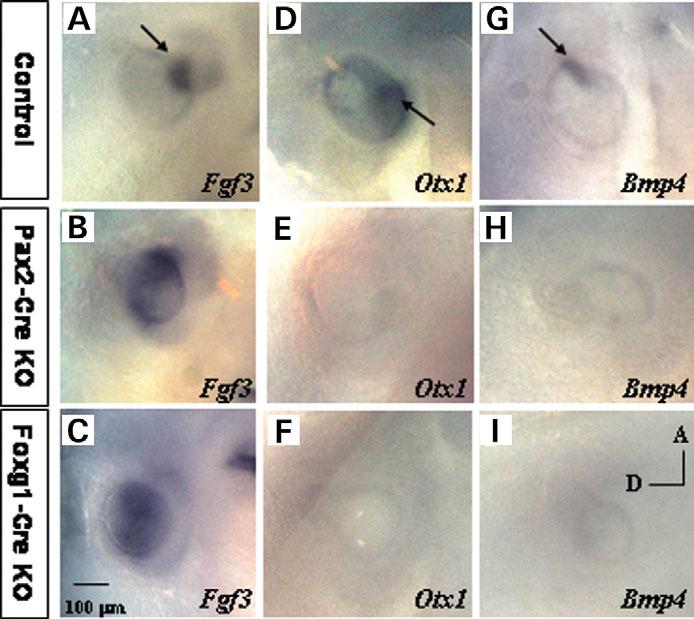

Figure 5.

Molecular marker analysis by ISH. Fgf3 expression in control (A), Foxg1-Cre (B) and Pax2-Cre (C) mutant embryos at E10.5. Expression of Otx1 in E10.5 control (D), Foxg1-Cre (E) and Pax2-Cre (F) mutant embryos. Bmp4 expression in control (G), Foxg1-Cre (H) and Pax2-Cre mutant embryos (I). Control, Tbx1+/−, Foxg1-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Foxg1-Cre/+, Pax2-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Pax2-Cre tg.

To determine if the PM plays a role in anterior–posterior patterning of the OV, we examined expression of several molecular markers in Foxg1-Cre or Pax2-Cre KO embryos (Fig. 5). As in the Tbx1−/− embryos, at E10.5 Fgf3 is expressed ectopically in the posterior OV in both mutants (Fig. 5B and C), as compared with controls (Fig. 5A, Tbx1 null/+ Cre). Conversely, expression of posterior OV marker Otx1 is lost in E10.5 mutant embryos (Fig. 5E and F). These results suggest that Tbx1 in the OV regulates sensory organ formation by the activation of posterior OV genes and by suppression of anterior, neurogenic gene expression. Moreover, our results suggest that Tbx1 in the PM is not sufficient to compensate for the loss of the gene in the OV, suggesting that it plays a permissive rather than an inductive role in early patterning of the OV.

To further analyze the role of OV-specific Tbx1 activity on sensory organ patterning, we analyzed Bmp4 expression in both Foxg1-Cre KO and Pax2-Cre KO embryos. Bmp4 has been localized to a site of juxtaposition of Tbx1 and neural bHLH (Ngn1/NeuroD) gene expression. Furthermore, the precise pattern of Bmp4 expression was lost in OVs of Tbx1−/− embryos (10). As expected, in control embryos (Tbx1 null/+ Cre), Bmp4 is present in an anterior stripe (E10.5), marking the presumptive anterior and lateral cristae (Fig. 5G) (10). However, in Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre KO embryos, the Bmp4 signal is downregulated, indicating that OV-specific Tbx1 activity is responsible for regulating Bmp4 patterning.

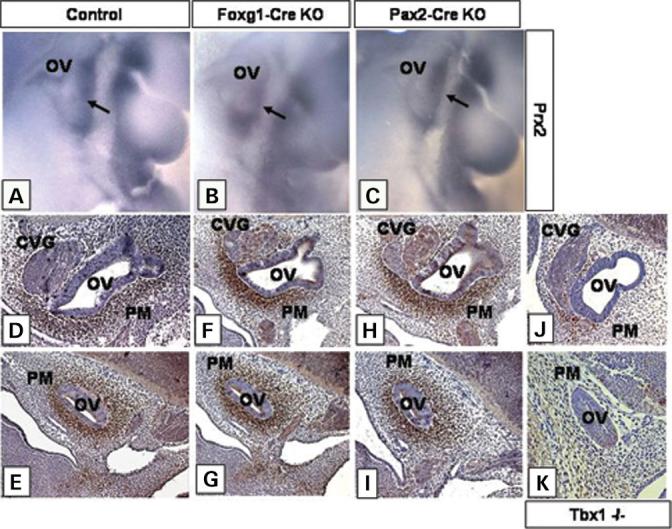

Tbx1 has independent functions in the PM

Inactivation of Tbx1 in the OV leads to severe malformations of sensory organs derived from the OV. However, Tbx1 mutation in the OV could also disrupt essential epithelial–mesenchymal interactions, interrupting cross-talk with the PM. Throughout mid-gestation (E10.5–E12.5), Tbx1 continues to be expressed in the PM, surrounding the OV. Tbx1−/− embryos have defects in the otic capsule, directly derived from these cells. Early indication of developmental defects in the PM of the Tbx1−/− mutants has been detected by the disappearance of Prx2 expression, an early homeodomain containing gene required for the condensation of mesenchyme to form cartilage (11,27). The loss of Prx2 expression has been hypothesized to be due to the reduction in the number of cells in the lateral PM (11). To determine if the loss of Tbx1 in the OV affects the expression of PM specification, we assessed expression of Prx2 in Foxg1-Cre KO and Pax2-Cre KO mutant embryos (Fig. 6A-C). In contrast to the reported loss of Prx2 expression in the Tbx1 null mutants (Tbx1−/−), when compared with controls (Fig. 6A, Tbx1 null /+ Cre), expression of the gene was intact in both Foxg1-Cre KO (Fig. 6B) and Pax2-Cre KO (Fig. 6C) embryos at E10.5.

Figure 6.

PM specification shown by expression of marker genes. Prx2 expression is shown by ISH on E10.5 control (A), Foxg1-Cre KO (B) and Pax2-Cre KO (C) embryos. The arrow points to the PM expression domain. Brn4 expression by IHC with a polyclonal Brn4 antibody on control (D and E), Tbx1 null/flox; Foxg1-Cre/+ (F and G), Tbx1 null/flox; Pax2-Cre tg (H and I) and Tbx1−/− (J and K) sagittal sections of E11.5 embryos. Control, Tbx1+/−, Foxg1-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Foxg1-Cre/+, Pax2-Cre KO, Tbx1 null/flox; Pax2-Cre tg.

These findings suggested that PM development was unaffected in Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre KO mutants. To further confirm normal specification of mesenchymal cells surrounding the OV, we assessed expression of marker genes in both Foxg1-Cre KO and Pax2-Cre KO mutants. Brn4 expression is normally restricted to the condensing mesenchyme surrounding the ear capsule and mutations in the gene lead to mesenchymal defects in auditory bones (10,28). In addition, Brn4 homozygous null mutant mice have defects in OV-derived structures, including a reduction in the number of cochlear turns, suggesting that Brn4 plays a role in epithelial–mesenchymal interactions necessary for inner ear development (28,29).

By E11.5, Brn4 is strongly expressed in the mesenchymal tissue surrounding the OV of control embryos (Fig. 6D and E, Tbx1 null/+ Cre). As expected, Brn4 expression is severely downregulated in the PM of Tbx1−/− embryos, indicating mesenchymal specification defects or loss of cells (Fig. 6J and K). Consistent with the Prx2 findings, expression of Brn4 was not downregulated in the PM of either Foxg1-Cre KO (Fig. 6F and G) or Pax2-Cre KO embryos (Fig. 6H and I) at E11.5. These results suggest that Brn4 expression is not regulated by signaling from the OV and may be induced cell autonomously by Tbx1 in the PM. Furthermore, the data suggests that PM specification is uninterrupted in both Foxg1-Cre KO and Pax2-Cre KO mutant embryos.

DISCUSSION

The majority of 22q11DS patients have ear disorders consisting of outer ear anomalies and chronic otitis media with associated conductive hearing loss, whereas 10% have sensor-ineural hearing loss (6). In addition, several reports have described patients with balance problems, although it is not known whether these are due to vestibular defects or to hypotonia (6). The transcription factor, TBX1 is hemizygously deleted in 22q11DS patients and mutated in a subset of patients without the deletion, implicating the gene in the etiology of the disorder (15,30). Furthermore, its pattern of expression during embryogenesis is consistent with the defects in the 22q11DS patients and in Tbx1 null (Tbx1−/−) mutant embryos (11,13,14,17,31). Tbx1 is expressed in multiple tissues forming the outer, middle and inner ear. The molecular pathogenesis of Tbx1 in the ear has now been delineated by tissue-specific inactivation using Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre. Analysis with molecular markers makes it possible to form a model of Tbx1 function in ear development.

Genetic pathway of Tbx1 in ear development

We showed that ablation of Tbx1 in the foregut endoderm disrupts the formation of the PPI (double-sided arrow; Fig. 7). When the endodermal pouch does not extend towards the overlying ectoderm, the cleft and pouch cannot become juxtaposed. This juxtaposition is necessary for the morphogenesis of the outer ear and for neural crest-derived mesenchymal condensations forming the middle ear ossicles (9). Epithelial–mesenchymal interactions between the mesenchyme of the arches and the epithelia of the endodermal pouches and ectodermal clefts are essential for formation of the outer and middle ear structures (7,32). Our data are consistent with non-cell autonomous roles of Tbx1 in mediating epithelial–mesenchymal interactions.

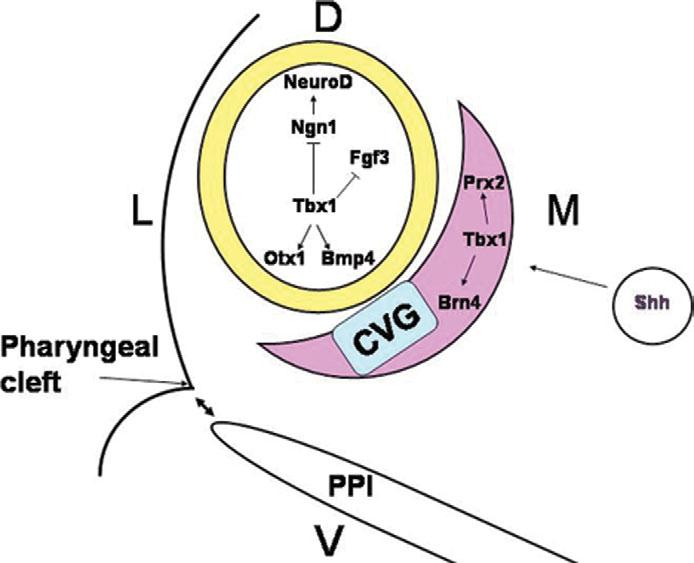

Figure 7.

Model of Tbx1 function in ear development. The inner ear develops from the ectodermally derived OV, shown in yellow. Adjacent to the OV is the PM (pink). Tbx1 in the OV plays a dual role in inner ear development by inducing sensory organ formation in the posterior OV through induction of Otx1 and Bmp4 and by suppressing neurogenesis in the anterior OV through negative regulation of Ngn1 and NeuroD. The suppression of neurogenesis leads to the presence of an expanded CVG rudiment, shown in blue. In parallel, Tbx1 in the PM plays a role in mesenchymal tissue specification through induction of Brn4 and Prx2. This process might be mediated by Shh signaling from the notochord (circle) and the floor plate. Tbx1 in the PPI mediates tissue interactions between the endoderm of the pouches and the ectoderm of the first pharyngeal cleft to promote middle and outer ear development (double-headed arrows).

Inactivation of Tbx1 in the OV leads to severe hypoplasia of the sensory organs and expanded neurogenesis, similar to the Tbx1−/− phenotype (10). Tbx1 may act cell-autonomously to induce Otx1 and Bmp4, required to form sensory organs, and to suppress Ngn1 and NeuroD, required to form the ganglion, in the same cells (Fig. 7). In parallel, Tbx1 may serve important but distinct cell-autonomous functions in the PM via positive regulation of genes such as Prx2 and Brn4 or via mesenchymal cell proliferation. Overall, the data presented in this study defines distinct, tissue-specific roles of Tbx1 in the endoderm, PM and the OV, leading to a better understanding of the gene's function in ear development.

Tbx1 in the OV is required for sensory organ formation

The mechanism behind the failure in sensory organ development in Tbx1 mutants remains elusive. A previous study addressed this question using chimeric embryos to analyze developmental potential of Tbx1−/− cells (11). The analysis showed that homozygous Tbx1 mutant cells rapidly disappear from the OV in chimeras, suggesting that they have a proliferation/survival disadvantage that prevents them from populating the OV. Together with the inner ear defects observed in Tbx1−/− embryos, these experiments suggested that Tbx1 is required for an expansion/differentiation of a subpopulation of cells necessary for cochlear and vestibular development in the OV. Alternatively, or in addition, it was proposed that patterning defect in Tbx1−/− embryos might occur as a result of interrupted signaling from the abnormal PM, because of the inactivation of Tbx1 in this tissue, as suggested by down-regulation of a transcription factor, Prx2 in Tbx1−/− PM (11). Our results show that OV-specific inactivation of Tbx1 phenocopies inner ear defects of the null mutant (Tbx1−/− ), suggesting that Tbx1 in the PM does not have a major role in OV patterning. Instead, the results of this study further argue for a cell-autonomous role of Tbx1 in the OV. This does not rule out the possibility that Tbx1 in the mesenchyme may be required for later aspects of cochlea and vestibular system morphogenesis.

Severe inner ear phenotypes, involving developmental arrest of both the OV and the CVG, were also found in mice mutant for Eya1 or Six1, two genetically linked genes that lie upstream of Tbx1 (8,9,33,34). In contrast to the Tbx1 mutants, increased apoptosis and abnormal cell proliferation are responsible for the OV-derived defects in Eya1−/− and Six1−/− mice (8,9,33,35). Furthermore, the ear defects in these mutants correlate with the expression domains of the genes, whereas global inner ear sensory malformations in Tbx1 mutants are not directly obvious from the Tbx1 expression pattern (10,11). Although expression of Tbx1 in the OV correlates with the prospective vestibular area, it is transcribed only in a small area overlapping with the Pax2 marked prospective cochlear domain (10,11,36). Tbx1 inactivation, either globally, or tissue specifically in the OV results in failure of cochlear development, suggesting that Tbx1 in the ventral OV plays a role in inductive cellular signaling events with the cells of the dorsal OV and that these events are required for morphogenesis of the cochlea.

One possible explanation for this discrepancy comes from observations of altered spatial expressions of several marker genes (10,36). In Tbx1−/− and in conditional mutant embryos, NeuroD and Lfng expression domains, which specify neurogenic cell fates, are extended posteriorly into the region that normally contributes to sensory organ development (10,36). Furthermore, other cochlear markers, such as Bmp4 and Otx1, normally found in the posterior OV are downregulated in Tbx1−/− and conditional null embryos (Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre KO) (10). It has therefore been suggested that Tbx1 specifies a midline boundary between the anterior (neurogenic and sensory) and posterior (sensory) regions of the OV (10). In addition, other reports have suggested that Tbx1 in the OV might be required to specify global gene expression patterns, required for formation of the cochlea and the vestibular system (36).

Role of Tbx1 in the PM

Tbx1 is also expressed in the PM surrounding the OV; the role of the gene in this tissue remains unknown (11). Previous studies have shown that Tbx1 loss of function leads to PM defects, as demonstrated by downregulation of several markers, including Prx2 (11). It has therefore been suggested that abnormal cochlear marker specification and the ensuing defects observed in Tbx1−/− embryos arise in a non-cell-autonomous manner, as a result of Tbx1 absence in the PM. Alternatively, it is possible that inactivation of Tbx1 in the OV disrupts tissue interactions between the OV and the PM, leading to abnormal development of the inner ear. Thus it was proposed that Tbx1 in the mesenchyme plays an inductive role in patterning the OV (11).

Our study instead argues that epithelial Tbx1 activity is required for OV patterning, which is disrupted when Tbx1 is inactivated. First, Tbx1 expressing cells in the PM are present in Foxg1-Cre KO and Pax2-Cre KO mutants. Second, although Brn4, a marker of these cells, is downregulated in Tbx1−/− embryos, its expression domain is unaltered in the PM of the conditional null mutants. This suggests that PM development in the conditional mutants is normal; the presence of Tbx1 in this tissue cannot rescue the defects caused by inactivation in the OV, suggesting that the gene plays a non-inductive role in the mesenchyme.

Brn4 and Prx2 are robustly expressed at E10.5 in the condensing mesenchyme surrounding the ear in wild-type (WT) embryos (28,37). Normal Brn4 and Prx2 expression in conditional mutant embryos also diminishes the possibility that Tbx1 in the OV mediates signaling events necessary for proper specification of the PM. Instead, the results of this study suggest a distinct local role for Tbx1 in the PM. It is possible that Tbx1 in the PM, although not required for early OV patterning, may be required for later development of the sensory organs or otic capsule. Conditional ablation in this tissue will be required to address the later developmental roles of Tbx1 in the PM. It has been shown that Sonic hedgehog (Shh) acts upstream of Tbx1 in the mesenchyme surrounding the OV (38). This process is independent from OV signaling pathways and may be regulated via Shh signaling from the notochord and the floor plate (Fig. 7).

Summary

Conditional inactivation of Tbx1 in the OV points to an essential and cell-autonomous role for the gene in this tissue. Ablation of Tbx1 in the OV using both the Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre strains leads to severe disruption in inner ear development. In addition to the OV-specific requirement of Tbx1 for inner ear morphogenesis, tissue-specific ablation of the gene in the OV and in the pharyngeal endoderm demonstrates the non-cell-autonomous role for endodermal Tbx1 in outer and middle ear development. Analysis of Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre conditional mutants thus provides crucial evidence for tissue-specific roles of Tbx1 in the formation of outer, middle and inner ear structures. Finally, this study contributes to the general understanding of embryonic and molecular processing governing the development of the auditory and vestibular systems, disrupted in 22q11DS and possibly in other human congenital malformation disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

The generation and maintenance of the Tbx1 null/ + and Tbx1 flox/flox mice has been previously described (19). The Foxg1-Cre strain was maintained in the congenic SW background. This strain mediates inactivation of the floxed allele in the OV and in the pharyngeal endoderm but not in the PM (19). The Pax2-Cre strain, which induces recombination in the OV, was maintained in the mixed N1 C57B/6 background (20). Foxg1-Cre/ + and Pax2-Cre tg mice were crossed to Tbx1 null/ + mice kept in the N5 SW and N4 C57Bl/6 backgrounds, respectively. To generate conditional null embryos, Tbx1 null/+; Foxg1-Cre/+ and Tbx1 null/+ ; Pax2-Cre tg mice were subsequently crossed with the Tbx1 flox/flox mice. The flox/flox mice were kept in the N2 C57Bl/6 background to minimize ectopic recombination. Both the Foxg1-Cre and Pax2-Cre strains were genotyped as previously described (20,21). WT morphology and marker expression was analyzed in both SW and C57Bl/6 background. All animals were held on a 24-h dark/light cycle; the day of the plug was recorded as E0.5. Embryos were staged according to the number of somites (39).

Histology

Mouse embryos were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution (Sigma) overnight. Following fixation, the embryos were dehydrated through graded ethanol, embedded in paraffin and sectioned (5–7 μM). All sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Skeletal staining of E17.5 embryos was performed using Alcian blue and Alizarin red as previously described (12). For histopathological analysis of adult mice, animals were sacrificed and their ears perfused with 10% formalin and 1% acetic acid, decalcified, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

ABR testing

Hearing status of adult mice 2–3 months of age was assessed by obtaining ABR thresholds. ABR signals were recorded from needle electrodes inserted through the skin (vertex to ipsilateral tragus). Computer-assisted evoked potential systems were used to obtain responses to tone pips at 5, 8, 11, 16, 22, 32 and 45 kHz (tone pip duration 5 ms; repetition rate 30/s) and averaged responses to 512 pips of alternating polarity.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes for Tbx1 (40), Fgf3 (cloned PCR fragment), NeuroD, Bmp4 and Otx1 were prepared by standard methods (10). Whole-mount and section ISH were performed as previously described (10,41). Some Tbx1-hybridized embryos were embedded in paraffin and microtome-sectioned at a thickness of 10–12 μM after the reporter reaction.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue was prepared by 10% formaldehyde fixation of whole embryos, which were paraffin wax embedded and sectioned at a thickness of 10 μM. Affinity-purified rabbit anti-Tbx1 (Zymed) was diluted 1:100 in TBS/0.1% Triton X-100/5% goat serum/2%BSA, incubated for 1 h at room temperature and detected with a biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG conjugate (1:200; Vectalab), avidin–biotin complex formation (Vectalab) and DAB reaction (Research Genetics). Monoclonal 2H3 antibody was used as previously described (10). The polyclonal anti-Brn4 antibody was generously provided by Dr E. Bryan Crenshaw and used in a 1:400 dilution as described earlier (10).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Steven Raft, Dr Jean Hebert and Dr Todd Evans for critically reading the manuscript and intellectual advice. We also thank Dr E. Bryan Crenshaw for generously providing the Brn4 antibody. This work is supported by the American Heart Association, March of Dimes (1-FY02-193, 1-FY2005-443) and the National Institutes of Health (DC05186-03) to B.E.M., (DC04876) to A.G., (DC003929) to J.C.A. and (DC01089) to M.C.B. J.S.A. is supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (DC006977-02).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Supplementary Material is available at HMG Online.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.DiGeorge A. A new concept of the cellular basis of immunity. J. Pediatr. 1965;67:907. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emanuel BS, McDonald-McGinn D, Saitta SC, Zackai EH. The 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Adv. Pediatr. 2001;48:39–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonald-McGinn DM, Kirschner R, Goldmuntz E, Sullivan K, Eicher P, Gerdes M, Moss E, Solot C, Wang P, Jacobs I, et al. The Philadelphia story: the 22q11.2 deletion: report on 250 patients. Genet. Couns. 1999;10:11–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg F. What defines DiGeorge anomaly? J. Pediatr. 1989;115:412–413. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80841-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuknecht HF. Mondini dysplasia: a clinical and pathological study. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. Suppl. 1980;89:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Digilio MC, Pacifico C, Tieri L, Marino B, Giannotti A, Dallapiccola B. Audiological findings in patients with microdeletion 22q11 (di George/velocardiofacial syndrome) Br. J. Audiol. 1999;33:329–333. doi: 10.3109/03005369909090116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fekete DM, Wu DK. Revisiting cell fate specification in the inner ear. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2002;12:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman RA, Makmura L, Biesiada E, Wang X, Keithley EM. Eya1 acts upstream of Tbx1, Neurogenin 1, NeuroD and the neurotrophins BDNF and NT-3 during inner ear development. Mech. Dev. 2005;122:625–634. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu PX, Zheng W, Huang L, Maire P, Laclef C, Silvius D. Six1 is required for the early organogenesis of mammalian kidney. Development. 2003;130:3085–3094. doi: 10.1242/dev.00536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raft S, Nowotschin S, Liao J, Morrow BE. Suppression of neural fate and control of inner ear morphogenesis by Tbx1. Development. 2004;131:1801–1812. doi: 10.1242/dev.01067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitelli F, Viola A, Morishima M, Pramparo T, Baldini A, Lindsay E. Tbx1 is required for inner ear morphogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:2041–2048. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jerome LA, Papaioannou VE. DiGeorge syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for the T-box gene, Tbx1. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:286–291. doi: 10.1038/85845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindsay EA, Vitelli F, Su H, Morishima M, Huynh T, Pramparo T, Jurecic V, Ogunrinu G, Sutherland HF, Scambler PJ, et al. Tbx1 haploinsufficieny in the DiGeorge syndrome region causes aortic arch defects in mice. Nature. 2001;410:97–101. doi: 10.1038/35065105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merscher S, Funke B, Epstein JA, Heyer J, Puech A, Lu MM, Xavier RJ, Demay MB, Russell RG, Factor S, et al. Tbx1 is responsible for cardiovascular defects in velo-cardio-facial/DiGeorge syndrome. Cell. 2001;104:619–629. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yagi H, Furutani Y, Hamada H, Sasaki T, Asakawa S, Minoshima S, Ichida F, Joo K, Kimura M, Imamura S, et al. Role of Tbx1 in human del22q11.2 syndrome. Lancet. 2003;362:1366–1373. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14632-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitelli F, Morishima M, Taddei I, Lindsay EA, Baldini A. Tbx1 mutation causes multiple cardiovascular defects and disrupts neural crest and cranial nerve migratory pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:915–922. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.8.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman DL, Garvey N, Hancock S, Alexiou M, Agulnik SI, Gibson-Brown JJ, Cebra-Thomas J, Bollag RJ, Silver LM, Papaioannou VE. Expression of the T-box family genes, Tbx1–Tbx5, during early mouse development. Dev. Dyn. 1996;206:379–390. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199608)206:4<379::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Z, Cerrato F, Xu H, Vitelli F, Morishima M, Vincentz J, Furuta Y, Ma L, Martin JF, Baldini A, et al. Tbx1 expression in pharyngeal epithelia is necessary for pharyngeal arch artery development. Development. 2005;132:5307–5315. doi: 10.1242/dev.02086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold JS, Werling U, Braunstein EM, Liao J, Nowotschin S, Edelmann W, Hebert JM, Morrow BE. Inactivation of Tbx1 in the pharyngeal endoderm results in 22q11DS malformations. Development. 2006;133:977–987. doi: 10.1242/dev.02264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohyama T, Groves AK. Generation of Pax2-Cre mice by modification of a Pax2 bacterial artificial chromosome. Genesis. 2004;38:195–199. doi: 10.1002/gene.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hebert JM, McConnell SK. Targeting of cre to the Foxg1 (BF-1) locus mediates loxP recombination in the telencephalon and other developing head structures. Dev. Biol. 2000;222:296–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao J, Kochilas L, Nowotschin S, Arnold JS, Aggarwal VS, Epstein JA, Brown MC, Adams J, Morrow BE. Full spectrum of malformations in velo-cardio-facial syndrome/DiGeorge syndrome mouse models by altering Tbx1 dosage. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:1577–1585. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohtani I, Schuknecht HF. Temporal bone pathology in DiGeorge's syndrome. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1984;93:220–224. doi: 10.1177/000348948409300306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black FO, Spanier SS, Kohut RI. Aural abnormalities in partial DiGeorge syndrome. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1975;101:129–134. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1975.00780310051014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adkins WY, Jr, Gussen R. Temporal bone findings in the third and fourth pharyngeal pouch (DiGeorge) syndrome. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1974;100:206–208. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1974.00780040214012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ten Berge D, Brouwer A, Korving J, Martin JF, Meijlink F. Prx1 and Prx2 in skeletogenesis: roles in the craniofacial region, inner ear and limbs. Development. 1998;125:3831–3842. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.19.3831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phippard D, Lu L, Lee D, Saunders JC, Crenshaw EB., III Targeted mutagenesis of the POU-domain gene Brn4/Pou3f4 causes developmental defects in the inner ear. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:5980–5989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05980.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samadi DS, Saunders JC, Crenshaw EB., III Mutation of the POU-domain gene Brn4/Pou3f4 affects middle-ear sound conduction in the mouse. Hear. Res. 2005;199:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoller JZ, Epstein JA. Identification of a novel nuclear localization signal in Tbx1 that is deleted in DiGeorge syndrome patients harboring the 1223delC mutation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:885–892. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerome LA, Papaioannou VE. DiGeorge syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for the T-box gene, Tbx1. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:286–291. doi: 10.1038/85845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Couly G, Creuzet S, Bennaceur S, Vincent C, Le Douarin NM. Interactions between Hox-negative cephalic neural crest cells and the foregut endoderm in patterning the facial skeleton in the vertebrate head. Development. 2002;129:1061–1073. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.4.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruf RG, Xu PX, Silvius D, Otto EA, Beekmann F, Muerb UT, Kumar S, Neuhaus TJ, Kemper MJ, Raymond RM, Jr., et al. SIX1 mutations cause branchio-oto-renal syndrome by disruption of EYA1-SIX1-DNA complexes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8090–8095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308475101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng W, Huang L, Wei ZB, Silvius D, Tang B, Xu PX. The role of Six1 in mammalian auditory system development. Development. 2003;130:3989–4000. doi: 10.1242/dev.00628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou D, Silvius D, Fritzsch B, Xu PX. Eya1 and Six1 are essential for early steps of sensory neurogenesis in mammalian cranial placodes. Development. 2004;131:5561–5572. doi: 10.1242/dev.01437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moraes F, Novoa A, Jerome-Majewska LA, Papaioannou VE, Mallo M. Tbx1 is required for proper neural crest migration and to stabilize spatial patterns during middle and inner ear development. Mech. Dev. 2005;122:199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heydemann A, Nguyen LC, Crenshaw EB., 3rd Regulatory regions from the Brn4 promoter direct LACZ expression to the developing forebrain and neural tube. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2001;128:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riccomagno MM, Martinu L, Mulheisen M, Wu DK, Epstein DJ. Specification of the mammalian cochlea is dependent on Sonic hedgehog. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2365–2378. doi: 10.1101/gad.1013302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theiler K. The House Mouse: Atlas of Embryonic Development. Springer; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Funke B, Epstein JA, Kochilas LK, Lu MM, Pandita RK, Liao J, Bauerndistel R, Schuler T, Schorle H, Brown MC, et al. Mice overexpressing genes from the 22q11 region deleted in velo-cardio-facial syndrome/DiGeorge syndrome have middle and inner ear defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2549–2556. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.22.2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epstein JA. Pax3 and vertebrate development. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2000;137:459–470. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-066-7:459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]