Abstract

Introduction

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare disease classically transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait and characterised by recurrent airway infections due to abnormal ciliary structure and function. To date, only two autosomal genes, DNAI1 and DNAH5 encoding axonemal dynein chains, have been shown to cause PCD with defective outer dynein arms. Here, we investigated one non‐consanguineous family in which a woman with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) gave birth to two boys with a complex phenotype combining PCD, discovered in early childhood and characterised by partial dynein arm defects, and RP that occurred secondarily. The family history prompted us to search for an X linked gene that could account for both conditions.

Results

We found perfect segregation of the disease phenotype with RP3 associated markers (Xp21.1). Analysis of the retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator gene (RPGR) located at this locus revealed a mutation (631_IVS6+9del) in the two boys and their mother. As shown by study of RPGR transcripts expressed in nasal epithelial cells, this intragenic deletion, which leads to activation of a cryptic donor splice site, predicts a severely truncated protein.

Conclusion

These data provide the first clear demonstration of X linked transmission of PCD. This unusual mode of inheritance of PCD in patients with particular phenotypic features (that is, partial dynein arm defects and association with RP), which should modify the current management of families affected by PCD or RP, unveils the importance of RPGR in the proper development of both respiratory ciliary structures and connecting cilia of photoreceptors.

Keywords: cilia, retinitis pigmentosa, RPGR, X linked primary ciliary dyskinesia

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD; MIM 242650) is a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders affecting 1 in 16 000 individuals, and usually transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait, although apparent X linked inheritance has been occasionally reported.1,2 PCD results from a functional and structural defect of cilia,3,4 leading to impaired mucociliary clearance responsible for recurrent respiratory infections, mainly bronchiectasis and chronic sinusitis with nasal polyposis and serous otitis. Approximately 50% of patients with PCD display situs inversus, thereby exhibiting Kartagener syndrome (MIM 244400). Most male patients are infertile, due to immotile spermatozoa together with functional and ultrastructural abnormalities of sperm flagella.5

Cilia and flagella share a common complex structure, with the axoneme composed of nine peripheral microtubule doublets arranged around a central pair of microtubules. Outer and inner dynein arms are attached to the peripheral doublets. By means of ATP dependent reactions, the dynein arms enable adjacent peripheral doublets to slide towards each other, which gives rise to ciliary and flagellar beating.6,7,8

The most common ultrastructural defect identified in patients with PCD is an absence of dynein arms affecting all cilia.5 To date, in spite of intense research efforts by numerous groups including ours, gene mutations have been identified only in patients displaying one particular ultrastructural defect: defective outer dynein arms (ODA). Only two autosomal genes so far have been clearly implicated in this condition: DNAI1 (9p21–p13)9 and DNAH5 (5p15.2)10 which encode two structural components of the ODA, an intermediate and a heavy axonemal dynein chains, respectively. No mutation has yet been reported in patients with other ultrastructural abnormalities.

In some cases, PCD has been shown to be associated with rare and unusual disorders such as polycystic kidney,11 hydrocephalus,12 or polysplenia and extrahepatic biliary atresia.13 Such associations could be explained either by the presence of motile cilia in extra‐respiratory tissues, or by the existence of axonemal components that are common to motile cilia and to primary and sensory cilia. Various respiratory symptoms sometimes related to abnormal cilia have also been reported in some patients with retinitis pigmentosa (RP)14,15,16,17 or with Usher syndrome characterised by the association of RP with sensorineural deafness.18 Recently, apparently X linked inheritance of coexisting PCD and RP was reported in one Caucasian family of Polish origin.19,20

We describe here a non‐consanguineous family in which a woman with RP gave birth to two boys presenting a complex phenotype associating PCD with RP. A diagnosis of PCD was established in early childhood on the basis of recurrent upper and lower airway infections related to functional and structural abnormalities of respiratory cilia. The presence of RP was secondarily detected in both children when they got older. Given the fact that photoreceptor and respiratory cilia share common structures21 and as the segregation pattern of RP within this family was compatible with an X linked mode of inheritance, we postulated that genes responsible for X linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP) could also be involved in PCD. As RP3 (Xp21.1), within which lies the retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator gene (RPGR), is a locus involved in most XLRP,22,23,24,25,26 we analysed the segregation of RP3 specific polymorphic markers within our family. The results obtained prompted us to screen the RPGR gene for mutations in this family as well as in other families with individuals displaying similar abnormalities.

Methods

Patients

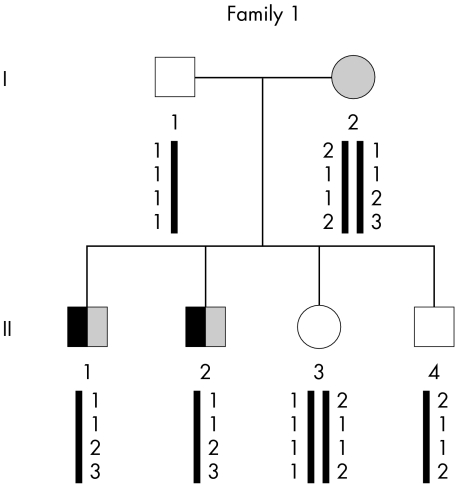

The two siblings, a 15 year old boy (patient II‐1) and a 13 year old boy (patient II‐2), who were born to unrelated parents (family 1, fig 1), presented in early childhood with respiratory symptoms characterised by chronic sinusitis, serous otitis, and recurrent episodes of bronchitis associated with severe atelectasis that led to partial lobectomy in both children when they were 14 years old (table 1). Neither subject had neonatal respiratory distress. Chest x ray and CT scan data, pulmonary function tests, and respiratory microbiological findings were typical for PCD,5 since diffuse bronchiectasis, distal obstruction without hypoxaemia, and the presence of haemophilius influenza were documented in the two affected boys. Pure tone audiometry (PTA) was performed in both children and their mother.

Figure 1 Genealogical tree of family 1 and segregation analysis of microsatellites spanning the RP3 locus (from top to bottom: DXS8090, DXS1069, DXS8025, and DXS8018). Subjects with PCD are indicated by a black symbol and those with RP by a shaded symbol. Clear symbols denote unaffected individuals.

Table 1 Clinical features of members of family 1.

| Individual | Sex | Age (years) | SI | Bronchiectasis | Sinusitis | Otitis | Lobectomy (lobe) | RP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I‐1 | M | 36 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| I‐2 | F | 36 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| II‐1 | M | 15 | − | + | + | + | + (left inferior, middle) | + |

| II‐2 | M | 13 | − | + | + | + | + (middle) | + |

| II‐3 | F | 11 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| II‐4 | M | 5 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

None of the individuals has situs inversus. Only patients II‐1 and II‐2, in whom the diagnosis of PCD was established after ciliary studies, display typical features of PCD, such as bronchiectases during childhood and chronic rhinosinusitis. Both had RP. RP, retinitis pigmentosa; SI, situs inversus.

Predominantly high frequency hearing impairment was recorded for patient II‐1, showing a mild and stable hearing loss between 4000 and 8000 Hz (−20 and −50 dB, respectively). PTA data were normal for patients I‐2 and II‐2.

Chest radiography showed cardiac and visceral normal situs solitus. Diagnoses of cystic fibrosis and immunodeficiency were excluded in both children. At different times during the course of their disease, samples of nasal and bronchial mucosa were obtained and processed for ciliary studies, as described previously.27

For each individual, genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples using the Nucleon BACC2 kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Similar studies were performed in 13 additional PCD families (families 2–14) that, to various degrees, displayed a close phenotype. The PCD genetic study was approved by the local ethics committee (CCPPRB Henri‐Mondor, Créteil, France) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their parents.

Genotyping analysis

In order to determine the RP3 associated haplotypes in the four multiplex families (families 1, 2, 3, and 4), we analysed the genotypes of microsatellite markers located in the vicinity of this locus: DXS1069, DXS8018, DXS8025, and DXS8090. Amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 30 s at 72°C, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 15 min. Products were analysed after purification on a 3100 ABI sequencer using Genescan software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Sequencing of RPGR genomic DNA and cDNA

In families 1 and 5–14, the 19 RPGR coding exons and their flanking intronic sequences were first amplified by PCR and the corresponding products then sequenced. In family 1, ORF15 was also analysed. Amplification and sequencing of exons 1–19 and ORF15 were performed as described.28

To determine the functional consequences of the identified mutation on the processing of RPGR transcripts, total RNA obtained from patient II‐1 (family 1) was prepared from nasal brushing, according to standard procedures.27 This RNA sample was reverse transcribed using oligodT and then amplified by PCR using two sets of primers: P3 5′‐TGA AAA AGT GAA ATT AGC TGC‐3′ and P4 5′‐GCT GAT TGG GAA GAC CTA ACT‐3′, and P5 5′‐GGA AAT AAT GAA GGA CAG TTG GG‐3′ and P6 5′‐TAT TCT CAA TGA CTT TGG GTT CTG‐3′.

Results

Axonemal abnormalities of patients from family 1

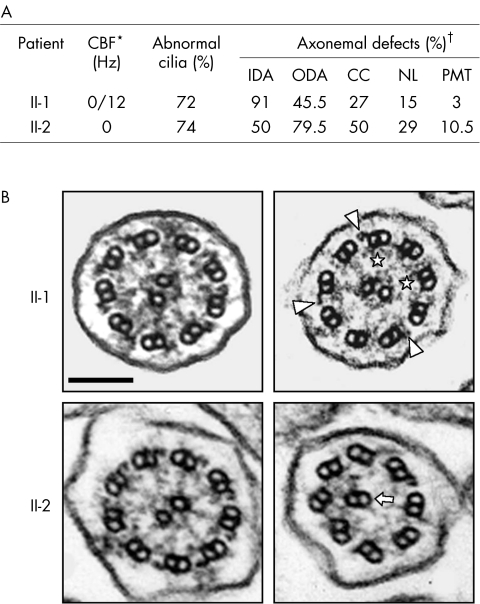

Both motile and immotile cilia were detected in different samples from patient II‐1 while no ciliary beating was observed in patient II‐2 (fig 2A). In both patients, transmission electron microscopy analyses showed numerous abnormal cilia in which different axonemal structures were missing, that is, outer and/or inner dynein arms, the central pair, and/or nexin links (fig 2B). The association of typical clinical features with abnormal ciliary structure and function led to the diagnosis of PCD in both patients. Neither their parents nor their other relatives had a history of respiratory disease. However, as their mother (I‐2) had RP, patients II‐1 and II‐2 underwent ophthalmological investigations that confirmed the diagnosis of RP in these two siblings.

Figure 2 Ultrastructural phenotype of respiratory cilia from patients II‐1 and II‐2 (family 1). (A) Summary of identified abnormalities involving various axonemal structures, as revealed by transmission electron microscopy. *The ciliary beat frequency (CBF) of patient II‐1 was measured twice; both motile and immotile cilia were detected in different samples from patient II‐1 while no ciliary beating was observed in patient II‐2 (normal beating value >10 Hz). The CBF of the mother (I‐2) was found to be normal. †Results of ciliary defects are given as the percentage of abnormal cilia for each missing axonemal structure (control subjects exhibit less than 10% abnormal cilia27). Each ultrastructural defect was found to be either isolated or associated with another ultrastructural defect within the same cilia. CC, central complex; IDA, inner dynein arm; NL, nexin links; ODA, outer dynein arm; PMT, peripheral microtubules. (B) Transverse sections of respiratory cilia from patients II‐1 (top) and II‐2 (bottom). As shown in the left panels, both display some normal cilia; the right panels show the main ultrastructural defect for each patient: absence of both dynein arms in patient II‐1 (remaining ODA and IDA are indicated by arrowheads and asterisks, respectively), and absence of both dynein arms and abnormal central complex in patient II‐2 (the arrow indicates an outer doublet of microtubules replacing the missing central complex). Bar: 100 nm.

Microsatellite genotyping

The segregation of four RP3 associated polymorphic markers (DXS1069, DXS8018, DXS8025, and DXS8090) was first studied within family 1. As shown in fig 1, haplotype analysis supported involvement of the RP3 locus in this family, a result that prompted us to screen for mutations the RPGR gene located at the RP3 locus.

RPGR mutation analysis

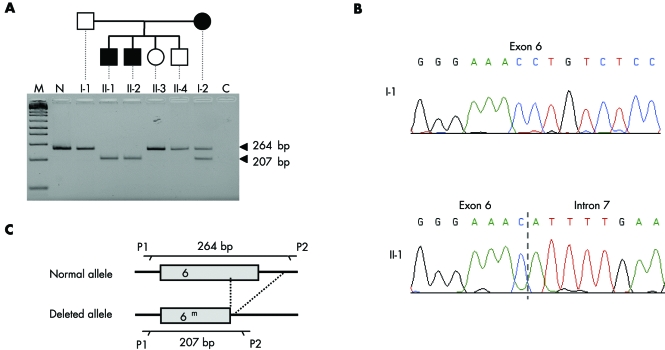

DNA samples from all members of family 1 were screened for mutations in the RPGR gene. The 19 RPGR coding exons and their flanking intronic sequences were amplified, and the resulting PCR products were first analysed by electrophoresis. The 264 bp amplicon corresponding to exon 6 was generated in healthy individuals (that is, I‐1, II‐3, and II‐4) but not in the two affected boys (that is, II‐1 and II‐2) in whom a smaller PCR product was obtained; individual I‐2 displayed a heterozygous pattern (fig 3A). Sequence analysis of the smaller product revealed a deletion of 57 bp (nucleotides 631–678 according to Meindl29) involving the first 9 bp of the adjacent donor splice site (fig 3B,C). The same deletion (631_IVS6+9del) was present in the heterozygous state in patient I‐2 (data not shown). No other mutation was found in the 18 remaining exons and in ORF15.

Figure 3 The 57 bp intragenic deletion identified on the maternal RPGR allele of patients II‐1 and II‐2 from family 1. (A) Exon 6 amplified products generated from a control subject (N) and the six members of the family. Lane C corresponds to a negative control (PCR without genomic DNA). The size marker (m) is a 1 kb+ ladder from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). (B) Nucleotide sequences of RPGR exon 6 in the study family. Patient II‐1 (as well as patient II‐2, data not shown) carries a deletion of the last 48 bp of exon 6 plus the following 9 bp of the adjacent intron (631_IVS6+9del). Individual I‐1 (as well as individuals II‐3 and II‐4, data not shown) displays a normal sequence. (C) Schematic representation of the deletion identified in this family and location of the primers used for the PCR.

Functional consequences of the RPGR 631_IVS6+9del mutation

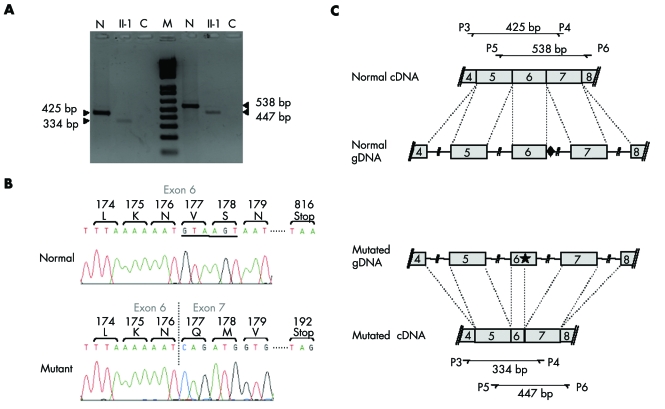

To determine the consequences that this intragenic deletion has on the processing of RPGR transcripts, total RNA obtained from nasal epithelial cells of patient II‐1 was reverse transcribed. The resulting products were used as templates in PCR amplifications performed with two different primer sets bracketing exon 6 (primers P3 and P4 located in exons 4 and 7, respectively; and primers P5 and P6, located in exons 5 and 8, respectively) (fig 4). RT‐PCR amplification of RPGR transcripts isolated from control cells yielded a 425 bp (primers P3–P4) or a 538 bp (primers P5–P6) amplicon consistent with the normal splicing of primary RPGR transcripts. In contrast, a similar experiment performed with the RNA sample from patient II‐1 generated a smaller product (334 and 447 bp with primers P3–P4 and P5–P6, respectively) (fig 4A).

Figure 4 Functional consequences of the identified deletion on RPGR RNA splicing. (A) RT‐PCR products generated from total RNA obtained from nasal cells from a control subject (lanes N) and from patient II‐1 (lanes II‐1). Both samples were amplified with primer sets P3–P4 (left half of the gel) and P5–P6 (right half of the gel). Lanes C correspond to negative controls (PCR without RNA sample). The size marker (M) is a 1 kb+ ladder from Invitrogen. (B) Nucleotide sequence of the RT‐PCR products generated with primers P5 and P6. In the presence of the 631_IVS6+9del mutation, a cryptic donor splice site located upstream in exon 6 (position 588 according to Meindl29) is used. Underlined sequence: splice site sequence used when the deletion occurred. (C) Schematic representation of the splicing events leading to normal (top) and abnormal (bottom) RPGR transcripts. The diamond indicates the natural splice site and the star indicates the cryptic splice site used in the presence of the 631_IVS6+9del mutation.

Sequencing of the latter products revealed that they resulted from the use of a cryptic donor splice site (5′‐GTAAGT‐3′) located within exon 6 at position 588 according to Meindl29 (fig 4B,C). This splicing defect would result in a frameshift that introduces 15 novel amino acids before a premature termination codon, thereby leading to a severely truncated protein.

RPGR analyses in our PCD population

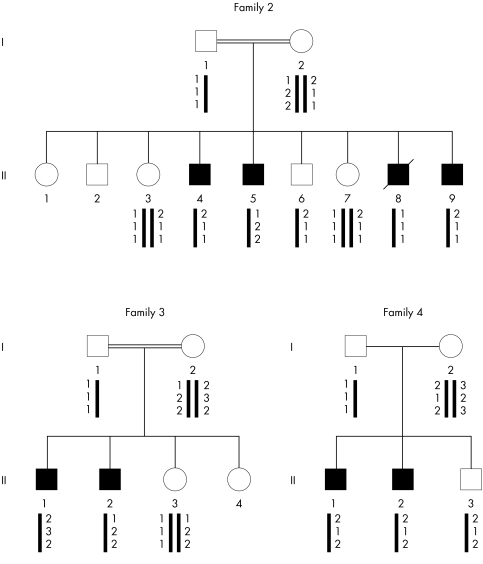

Molecular studies were also performed in 13 other unrelated families with a diagnosis of PCD. Three multiplex families were included because the transmission of the PCD phenotype was compatible with an X linked trait (families 2–4), even though two of them (families 2 and 3) were consanguineous. The two affected brothers of family 4 were also diagnosed as having Usher syndrome. Five patients of the remaining families with PCD had situs inversus and were, therefore, considered to have Kartagener syndrome (families 5–9).

The ciliary beat frequency measured in patients from families 2–14 was zero. The ultrastructural abnormalities concerned either the ODA (families 2–4) or both dynein arms (families 5–14), and were expressed in all examined cilia.

The segregation of RP3 associated polymorphic markers within families 2–4 allowed us to decide that this locus was not implicated in PCD disease (fig 5). Sequencing of all RPGR exons and flanking intronic sequences in families 5–14 did not reveal any mutation.

Figure 5 Segregation analysis of RP3 associated microsatellite markers within families 2–4 (from top to bottom: DX58090, DX51069, DX58025) . A maternal recombination between markers DX58090 and DX51069 is documented in patient II‐8 from family 2.

Discussion

To date, only two autosomal genes (DNAI19 and DNAH510) have been implicated in PCD, the very few identified patients all displaying the same ciliary defect characterised by an absence of ODA. The current study identifies the X linked RPGR gene as a new gene involved in PCD, a condition whose diagnosis was confirmed by the presence of axonemal abnormalities that are both complex and unusual. The course of the disease in the two affected boys is also unusual, since RP occurred secondarily. These data, which provide the first clear demonstration of X linked transmission of PCD, further support the debated view that the RPGR protein plays important roles in both retinal and pulmonary function. As detailed below, these findings have major clinical implications for the management of families affected by PCD or RP.

Mutations in RPGR have been reported in patients with XLRP. RP is a group of diseases characterised by retinal degeneration, with progressive night blindness, loss of peripheral vision, and eventual loss of central vision. Fundus abnormalities include the typical intraretinal bone spicule pigmentation due to accumulation of pigments by apoptosis of the photoreceptors from the retinal pigment epithelium. All modes of inheritance of RP have been described, with XLRP accounting for 10–20% of genetically identifiable cases.30 Two major loci have been identified in XLRP: RP2 (Xp11.23) and RP3 (Xp21.1), accounting for 10–20%23,31,32,33 and 70–75%22,23,24,25,26 of XLRP patients, respectively. The corresponding disease genes are now known, namely RP231 and RPGR.29,34

Numerous RPGR molecular defects have been reported among patients with RP. These mutations are not clustered in a particular region but are spread over the entire gene. The 631_IVS6+9del intragenic deletion identified in this study is new; it involves the last 48 bp of exon 6 and the adjacent donor splice site. As shown by the study of RPGR transcripts expressed in the nasal epithelial cells of patient II‐1 from family 1, this defect leads to the activation of a cryptic donor splice site located within exon 6; indeed, the RPGR gene contains the sequence 5′‐GTAAGT‐3′ in exon 6, which matches the consensus sequence (5′‐GT(A/G)AGT‐3′) of a donor splice site.35 Such abnormal splicing would result in a frameshift introducing a premature stop codon located 14 amino acids downstream, giving rise to a severely truncated RPGR protein (192 amino acids instead of the 815 residues normally present).

Our observation is reminiscent of the association of XLRP with recurrent respiratory infections reported in three families with different mutations in the RPGR gene.14,15,16,17 Respiratory symptoms occurred in male patients and consisted mainly of recurrent upper airway infections (that is, otitis and sinusitis), sometimes associated with episodes of bronchitis. It is noteworthy that bronchiectasis, which is classically found in adults with PCD, was not reported in any of these patients. Three different RPGR mutations were identified in these unrelated families. The first mutation (IVS5+1G>T),15 which was found in a family first reported by Van Dorp et al,14 was shown to induce abnormal splicing of RPGR transcripts, leading to a frameshift that predicted a severely truncated protein consisting of the first 124 amino acids, followed by a novel sequence of 17 residues; in this family, seven out of the 10 male patients with RP displayed recurrent respiratory infections and, in two of them, the existence of ciliary abnormalities was mentioned. The second family carried a 2 bp deletion (845_846delTG) in exon 8 that leads to a frameshift introducing a premature stop codon resulting in a truncated protein consisting of 280 residues; this deletion was reported in a family in which several members had XLRP associated with sinusitis, chronic chest infection, and hearing loss.16 Although in our study the hearing loss documented in patient II‐1 is much less severe, it is noteworthy that, in both cases, the defect is of sensorineural origin. In the third family, the patients presented with XLRP, recurrent otitis media, recurrent upper respiratory tract infections, and hearing loss. A G‐to‐C nucleotide substitution was identified in exon 6 (576G>C) resulting in the G173R missense mutation; this latter mutation involves an invariant amino acid within the RCC1 homology domain of the RPGR protein, thereby suggesting a deleterious effect on protein function.36

Most importantly, although these molecular defects have been found in patients with a complex phenotype combining RP and respiratory symptoms, a number of other mutations affecting the same exons and with similar severe consequences at the protein level have been identified in patients with XLRP and in whom no respiratory symptoms were reported.28 In one particular study, the absence of respiratory symptoms was even clearly mentioned; this concerned two large families with several patients with XLRP and who were shown to carry the IVS2‐1G>A and the 1244_1245delGA mutations in exon 10, expected to result in truncated proteins.37 Taken together, these observations, therefore, support the absence of a relationship between the location of the mutation and the association of RP with respiratory symptoms. However, the possibility cannot be excluded that this relationship indeed exists but is not easily recognised because of mild expression of the respiratory symptoms.

Two ultrastructural studies performed in patients with Usher syndrome type 2, a form of autosomal recessive RP with congenital sensorineural hearing impairment, have suggested that abnormalities in photoreceptor axonemes could contribute to the pathogenesis of RP38,39; an increased number of microtubules belonging to the centre and/or the periphery of the axoneme has indeed been reported in those studies. In addition, in a few patients with RP, the axonemal ultrastructure has been studied on motile cilia40,41 or sperm flagella;42 those patients seem to have an increased incidence of ciliary abnormalities involving airway cells compared to controls. These abnormalities consist mainly of departures from the classic 9+2 arrangement of axonemal microtubules (that is, increased or decreased number of microtubules belonging to the outer doublets or the central complex), and a higher incidence of compound cilia.40,41 However, no respiratory symptoms were reported in those patients. In the present study, the ciliary phenotype of the two siblings in whom we identified an RPGR mutation is unusual: most cilia were found to be immotile and carried complex ultrastructural defects, involving both dynein arms and including abnormal microtubule organisation.

In our family with an RPGR mutation, it is notable that the two boys have both RP and PCD, whereas their mother, who carries the same defect in the heterozygous state, displays an RP phenotype with no respiratory symptoms. In this regard, although the ciliary motility of nasal ciliated cells was found to be normal in the mother, it would be of particular interest to analyse the structure of these axonemes by transmission electron microscopy, a study that could not be performed because of the small amount of available ciliated cells. One should also keep in mind that in heterozygotes for X linked genes, the ratio of cells carrying the transcriptionally active normal or mutated copy of a disease gene is near 50:50, but departure from this ratio, known as skewing of X chromosome inactivation, may also arise.43 Such a phenomenon may explain the existence of symptomatic RP in the heterozygous mother, an observation in keeping with previous reports of female patients with XLRP.44,45 In the present study, the absence of respiratory symptoms in the mother may result from the fact that the PCD phenotype is transmitted as a recessive trait, with the hypothesis that a small amount of normal RPGR protein is sufficient for normal ciliary function in respiratory cells. An alternative hypothesis is based on a possible skewing of X chromosome inactivation in airway cells: as these cells are known to increase their renewal in response to environmental aggression, which is not the case for photoreceptors, selection of airway cells with an active normal gene might be favoured in female carriers.

At first glance, the association of respiratory and visual symptoms is not surprising, since both the respiratory and photoreceptor cilia contain axonemal structures. However, the identification of an RPGR mutation in patients with PCD and RP now raises the question of the specific role of the RPGR protein in the pathogenesis of this complex phenotype. In this regard, although the overall architecture of axonemes has been highly conserved throughout evolution, from protozoa to mammals, some structural diversity has been recognised, especially in vertebrates, depending on the tissue analysed. Axonemal structures are indeed found in various sites, including the airways and the reproductive tract, where axonemes are composed of nine outer doublet microtubules surrounding a central pair of singlet microtubules (9+2 arrangement) and retina (photoreceptor connecting cilia) or embryonic cochlea (hair cells), in which axonemes are devoid of the central pair of microtubules (9+0 arrangement). Although expression of RPGR, as assessed by northern blot, was detectable in all tissues tested,29 it is noteworthy that the RPGR protein was shown to be localised in the cilia connecting the outer segment to the inner segment of murine photoreceptors, as well as in the mouse trachea46 and, in humans, in the photoreceptor outer segment of the retina and in the epithelial lining of bronchi and sinuses.36 Although the function of RPGR in the retina remains incompletely understood, it has been suggested that RPGR could be an intraflagellar transport (IFT) protein involved in the trafficking of rhodopsin and/or other phototransduction proteins.36 As IFT is required for the assembly and maintenance of cilia and photoreceptor connecting cilium,21 it has been suggested that defects in this process may underlie human diseases that, like RP, are associated with progressive blindness.47,48 Similarly, given both the complex phenotype of the patients with an RPGR mutation and the expression pattern of the RPGR protein, it is tempting to speculate that abnormal IFT may alter the construction and/or maintenance of respiratory cilia as well, and in turn lead to an overall disorganisation of the ciliary structure; the ciliary phenotype documented in the patients (that is, heterogeneity of the defects and existence of partial defects) further supports this hypothesis.

In conclusion, these data provide the first clear demonstration of X linked transmission of PCD. This unusual mode of inheritance of PCD is described in patients with particular features (that is, partial dynein arm defects and association with RP), pointing out the importance of RPGR in the proper development of both respiratory ciliary structures and connecting cilia of photoreceptors. This observation has several major clinical implications: patients with PCD should have a careful ophthalmological examination for signs suggestive of RP. Ophthalmological examination should also be proposed to the mothers of young male patients with PCD; indeed, one should keep in mind that, in our family, the first diagnosis was of PCD, before the identification of a complex phenotype with the secondary occurrence of RP. Such an ophthalmological examination would help to identify female carriers in whom the XLRP phenotype may be particularly mild.45 The other consequence is the accurate recognition of an X linked mode of inheritance of the PCD phenotype, information of prime importance for genetic counselling. Conversely, it now seems important to look for sino‐respiratory symptoms in families with RP, especially when X linked transmission is documented, and even to study ciliary structure and function in those patients. Management of PCD, which already involves paediatricians, pneumologists, otolaryngologists, reproduction biologists, and geneticists, should now concern ophthalmologists as well.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the families for agreeing to participate in this study.

Abbreviations

IFT - intraflagellar transport

ODA - outer dynein arms

PCD - primary ciliary dyskinesia

PTA - pure tone audiometry

RP - retinitis pigmentosa

XLRP - X linked retinitis pigmentosa

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the GIS Maladies Rares (A03091), the Assistance Publique‐Hôpitaux de Paris (CRC 96125), and the Legs Poix from the Chancellerie des Universités. A Moore is the recipient of a fellowship from the Ministère de l'éducation nationale, de l'enseignement supérieur et de la recherche.

Competing interests: none declared

Consent was received for the publication of these patient details

References

- 1.Narayan D, Krishnan S N, Upender M, Ravikumar T S, Mahoney M J, Dolan T F, Jr, Teebi A S, Haddad G G. Unusual inheritance of primary ciliary dyskinesia (Kartagener's syndrome). J Med Genet 199431(6)493–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krawczynski M R, Dmenska H, Witt M. Apparent X‐linked primary ciliary dyskinesia associated with retinitis pigmentosa and a hearing loss. J Appl Genet 200445(1)107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afzelius B A. A human syndrome caused by immotile cilia. Science 1976193(4250)317–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossman C M, Forrest J B, Lee R M, Newhouse M T. The dyskinetic cilia syndrome. Ciliary motility in immotile cilia syndrome. Chest 198078(4)580–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afzelius B A. The immotile‐cilia syndrome: a microtubule‐associated defect. CRC Crit Rev Biochem 198519(1)63–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witman G B. Axonemal dyneins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19924(1)74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter M E. Axonemal dyneins: assembly, organization, and regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19968(1)10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shingyoji C, Higuchi H, Yoshimura M, Katayama E, Yanagida T. Dynein arms are oscillating force generators. Nature 1998393(6686)711–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pennarun G, Escudier E, Chapelin C, Bridoux A M, Cacheux V, Roger G, Clement A, Goossens M, Amselem S, Duriez B. Loss‐of‐function mutations in a human gene related to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii dynein IC78 result in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am J Hum Genet 199965(6)1508–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olbrich H, Haffner K, Kispert A, Volkel A, Volz A, Sasmaz G, Reinhardt R, Hennig S, Lehrach H, Konietzko N, Zariwala M, Noone P G, Knowles M, Mitchison H M, Meeks M, Chung E M, Hildebrandt F, Sudbrak R, Omran H. Mutations in DNAH5 cause primary ciliary dyskinesia and randomization of left‐right asymmetry. Nat Genet 200230(2)143–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saeki H, Kondo S, Morita T, Sasagawa I, Ishizuka G, Koizumi Y. Immotile cilia syndrome associated with polycystic kidney. J Urol 1984132(6)1165–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenstone M A, Jones R W, Dewar A, Neville B G, Cole P J. Hydrocephalus and primary ciliary dyskinesia. Arch Dis Child 198459(5)481–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gershoni‐Baruch R, Gottfried E, Pery M, Sahin A, Etzioni A. Immotile cilia syndrome including polysplenia, situs inversus, and extrahepatic biliary atresia. Am J Med Genet 198933(3)390–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Dorp D B, Wright A F, Carothers A D, Bleeker‐Wagemakers E M. A family with RP3 type of X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa: an association with ciliary abnormalities. Hum Genet 199288(3)331–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dry K L, Manson F D, Lennon A, Bergen A A, Van Dorp D B, Wright A F. Identification of a 5′ splice site mutation in the RPGR gene in a family with X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP3). Hum Mutat 199913(2)141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zito I, Downes S M, Patel R J, Cheetham M E, Ebenezer N D, Jenkins S A, Bhattacharya S S, Webster A R, Holder G E, Bird A C, Bamiou D E, Hardcastle A J. RPGR mutation associated with retinitis pigmentosa, impaired hearing, and sinorespiratory infections. J Med Genet 200340(8)609–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iannaccone A, Wang X, Jablonski M M, Kuo S F, Baldi A, Cosgrove D, Morton C C, Swaroop A. Increasing evidence for syndromic phenotypes associated with RPGR mutations. Am J Ophthalmol 2004137(4)785–6 author reply 7864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonneau D, Raymond F, Kremer C, Klossek J M, Kaplan J, Patte F. Usher syndrome type I associated with bronchiectasis and immotile nasal cilia in two brothers. J Med Genet 199330(3)253–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krawczynski M R, Witt M. PCD and RP: X‐linked inheritance of both disorders? Pediatr Pulmonol 200438(1)88–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geremek M, Witt M. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: genes, candidate genes and chromosomal regions. J Appl Genet 200445(3)347–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pazour G J, Baker S A, Deane J A, Cole D G, Dickert B L, Rosenbaum J L, Witman G B, Besharse J C. The intraflagellar transport protein, IFT88, is essential for vertebrate photoreceptor assembly and maintenance. J Cell Biol 2002157(1)103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ott J, Bhattacharya S, Chen J D, Denton M J, Donald J, Dubay C, Farrar G J, Fishman G A, Frey D, Gal A.et al Localizing multiple X chromosome‐linked retinitis pigmentosa loci using multilocus homogeneity tests. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 199087(2)701–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teague P W, Aldred M A, Jay M, Dempster M, Harrison C, Carothers A D, Hardwick L J, Evans H J, Strain L, Brock D J.et al Heterogeneity analysis in 40 X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa families. Am J Hum Genet 199455(1)105–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buraczynska M, Wu W, Fujita R, Buraczynska K, Phelps E, Andreasson S, Bennett J, Birch D G, Fishman G A, Hoffman D R, Inana G, Jacobson S G, Musarella M A, Sieving P A, Swaroop A. Spectrum of mutations in the RPGR gene that are identified in 20% of families with X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet 199761(6)1287–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miano M G, Testa F, Strazzullo M, Trujillo M, De Bernardo C, Grammatico B, Simonelli F, Mangino M, Torrente I, Ruberto G, Beneyto M, Antinolo G, Rinaldi E, Danesino C, Ventruto V, D'Urso M, Ayuso C, Baiget M, Ciccodicola A. Mutation analysis of the RPGR gene reveals novel mutations in south European patients with X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa. Eur J Hum Genet 19997(6)687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vervoort R, Lennon A, Bird A C, Tulloch B, Axton R, Miano M G, Meindl A, Meitinger T, Ciccodicola A, Wright A F. Mutational hot spot within a new RPGR exon in X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet 200025(4)462–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Escudier E, Escalier D, Pinchon M C, Boucherat M, Bernaudin J F, Fleury‐Feith J. Dissimilar expression of axonemal anomalies in respiratory cilia and sperm flagella in infertile men. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990142(3)674–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breuer D K, Yashar B M, Filippova E, Hiriyanna S, Lyons R H, Mears A J, Asaye B, Acar C, Vervoort R, Wright A F, Musarella M A, Wheeler P, MacDonald I, Iannaccone A, Birch D, Hoffman D R, Fishman G A, Heckenlively J R, Jacobson S G, Sieving P A, Swaroop A. A comprehensive mutation analysis of RP2 and RPGR in a North American cohort of families with X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet 200270(6)1545–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meindl A, Dry K, Herrmann K, Manson F, Ciccodicola A, Edgar A, Carvalho M R, Achatz H, Hellebrand H, Lennon A, Migliaccio C, Porter K, Zrenner E, Bird A, Jay M, Lorenz B, Wittwer B, D'Urso M, Meitinger T, Wright A. A gene (RPGR) with homology to the RCC1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor is mutated in X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP3). Nat Genet 199613(1)35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bird A C. X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa. Br J Ophthalmol 197559(4)177–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwahn U, Lenzner S, Dong J, Feil S, Hinzmann B, van Duijnhoven G, Kirschner R, Hemberger M, Bergen A A, Rosenberg T, Pinckers A J, Fundele R, Rosenthal A, Cremers F P, Ropers H H, Berger W. Positional cloning of the gene for X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa 2. Nat Genet 199819(4)327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardcastle A J, Thiselton D L, Van Maldergem L, Saha B K, Jay M, Plant C, Taylor R, Bird A C, Bhattacharya S. Mutations in the RP2 gene cause disease in 10% of families with familial X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa assessed in this study. Am J Hum Genet 199964(4)1210–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mears A J, Gieser L, Yan D, Chen C, Fahrner S, Hiriyanna S, Fujita R, Jacobson S G, Sieving P A, Swaroop A. Protein‐truncation mutations in the RP2 gene in a North American cohort of families with X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet 199964(3)897–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roepman R, van Duijnhoven G, Rosenberg T, Pinckers A J, Bleeker‐Wagemakers L M, Bergen A A, Post J, Beck A, Reinhardt R, Ropers H H, Cremers F P, Berger W. Positional cloning of the gene for X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa 3: homology with the guanine‐nucleotide‐exchange factor RCC1. Hum Mol Genet 19965(7)1035–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohshima Y, Gotoh Y. Signals for the selection of a splice site in pre‐mRNA. Computer analysis of splice junction sequences and like sequences. J Mol Biol 1987195(2)247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iannaccone A, Breuer D K, Wang X F, Kuo S F, Normando E M, Filippova E, Baldi A, Hiriyanna S, MacDonald C B, Baldi F, Cosgrove D, Morton C C, Swaroop A, Jablonski M M. Clinical and immunohistochemical evidence for an X linked retinitis pigmentosa syndrome with recurrent infections and hearing loss in association with an RPGR mutation. J Med Genet 200340(11)e118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koenekoop R K, Loyer M, Hand C K, Al Mahdi H, Dembinska O, Beneish R, Racine J, Rouleau G A. Novel RPGR mutations with distinct retinitis pigmentosa phenotypes in French‐Canadian families. Am J Ophthalmol 2003136(4)678–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunter D G, Fishman G A, Mehta R S, Kretzer F L. Abnormal sperm and photoreceptor axonemes in Usher's syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 1986104(3)385–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrong S D, Chaitin M H, Fliesler S J, Possin D E, Jacobson S G, Milam A H. Ultrastructure of connecting cilia in different forms of retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol 1992110(5)706–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arden G B, Fox B. Increased incidence of abnormal nasal cilia in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Nature 1979279(5713)534–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fox B, Bull T B, Arden G B. Variations in the ultrastructure of human nasal cilia including abnormalities found in retinitis pigmentosa. J Clin Pathol 198033(4)327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunter D G, Fishman G A, Kretzer F L. Abnormal axonemes in X‐linked retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol 1988106(3)362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyon M F. X chromosome inactivation: no longer ‘all‐or‐none'. Eur J Hum Genet 200513(7)796–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bird A C. Clinical investigation of retinitis pigmentosa. Prog Clin Biol Res 19872473–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grover S, Fishman G A, Anderson R J, Lindeman M. A longitudinal study of visual function in carriers of X‐linked recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology 2000107(2)386–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hong D H, Pawlyk B, Sokolov M, Strissel K J, Yang J, Tulloch B, Wright A F, Arshavsky V Y, Li T. RPGR isoforms in photoreceptor connecting cilia and the transitional zone of motile cilia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200344(6)2413–2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marszalek J R, Liu X, Roberts E A, Chui D, Marth J D, Williams D S, Goldstein L S. Genetic evidence for selective transport of opsin and arrestin by kinesin‐II in mammalian photoreceptors. Cell 2000102(2)175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenbaum J L, Witman G B. Intraflagellar transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20023(11)813–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]