Abstract

Background

Cutis laxa is an acquired or inherited condition characterized by redundant, pendulous and inelastic skin. Autosomal dominant cutis laxa has been described as a benign disease with minor systemic involvement.

Objective

To report a family with autosomal dominant cutis laxa and a young girl with sporadic cutis laxa, both with variable expression of an aortic aneurysmal phenotype ranging from mild dilatation to severe aneurysm or aortic rupture.

Methods and results

Histological evaluation of aortic aneurysmal specimens indicated classical hallmarks of medial degeneration, paucity of elastic fibres, and an absence of inflammatory or atherosclerotic lesions. Electron microscopy showed extracellular elastin deposits lacking microfibrillar elements. Direct sequencing of genomic amplimers detected defects in exon 30 of the elastin gene in affected individuals, but did not in 121 normal controls. The expression of mutant elastin mRNA forms was demonstrated by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction analysis of cutis laxa fibroblasts. These mRNAs coded for multiple mutant tropoelastins, including C‐terminally truncated and extended forms as well as for molecules lacking the constitutive exon 30.

Conclusions

ELN mutations may cause severe aortic disease in patients with cutis laxa. Thus regular cardiac monitoring is necessary in this disease to avert fatal aortic rupture.

Keywords: aorta, aneurysm, genetics, mutation, splicing

Early clinical examination and review of published cases of cutis laxa led to the conclusion that recessive cutis laxa was associated with high morbidity and mortality from cardiopulmonary causes, including pulmonary emphysema and aortic aneurysms, whereas autosomal dominant cutis laxa was free of grave systemic lesions and was associated with a normal life span.1 Heterozygous mutations in the elastin gene (ELN) have been shown to cause autosomal dominant cutis laxa. The phenotypic spectrum of this condition remains poorly defined as only five patients have been described with detailed clinical information and positive mutational results.2,3,4

We have recently described a family with autosomal dominant cutis laxa caused by an unusual partial tandem duplication in ELN. Associated systemic conditions included inguinal hernias and severe emphysema that led to end stage respiratory failure requiring a lung transplant in one of the affected family members. This showed for the first time that ELN mutations could lead to fatal pulmonary complications.5 In the present study, we report a family with autosomal dominant cutis laxa and a sporadic case of cutis laxa with ELN mutations and variable expression of a thoracic aortic aneurysmal phenotype, ranging from mild dilatation to severe aneurysm requiring aortic root replacement or leading to aortic rupture early in adulthood.

Methods

Human subjects

Blood samples, skin biopsies, and surgically removed tissue specimens were obtained from study participants after informed consent. Normal control tissue samples were provided by the Cooperative Human Tissue Network which is funded by the National Cancer Institute. Other investigators may have received specimens from the same subjects. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Studies (IRB) of the University of Hawaii and of Washington University in St Louis.

Mutational analysis

After isolation of nuclei from whole blood, DNA was purified by proteinase K digestion and phenol extraction.6 Each exon of ELN with flanking intronic sequences was amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as described earlier.7 Amplimers were directly sequenced on both strands using the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). A panel of 121 normal control individuals was genotyped for mutations 2114_2138del and 2159delC using denaturing high performance liquid chromatography (dHPLC; Wave, Transgenomic, Omaha, Nebraska, USA).

Expression studies

For the analysis of allelic expression, 3 μg of total RNA were used to generate first strand cDNA using a Superscript preamplification system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) with oligo‐dT primers. First strand cDNA was amplified using oligonucleotide primers 5′‐AGCCAAAGCTGCTGCCAAAG‐3′ and 5′‐TTCTCTTCCGGCCACAACCT‐3′ complementary to exons 29 and the 3′‐UTR, respectively. The exon 29 primer was radiolabelled using γ‐P[33]‐ATP to generate radioactive reverse transcriptase (RT)‐PCR products, which were separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Products were quantitatively analysed using a Typhoon 9410 phosphorimager (Amersham, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA). To establish the dynamic range of our RT‐PCR assay, we conducted experiments at various cycle numbers. The amplification was found to be exponential up to 35 cycles. Subsequent reactions were conducted at 22–23 cycles to ensure quantitative recovery of RT‐PCR products representing various isoforms. Products that achieved, in at least one sample, more than 1% of the total signal was excised from the gel, re‐amplified, and analysed by direct DNA sequencing to uncover the primary structure of each elastin mRNA isoform.

Results

Clinical description

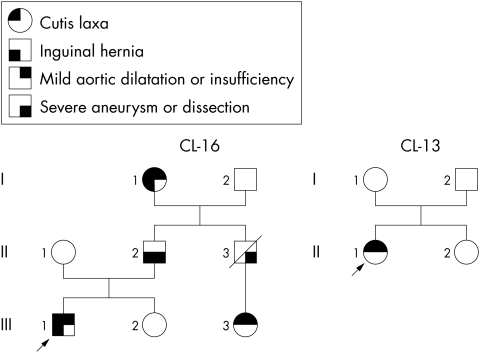

We studied a three generation family of Japanese and German ancestry (CL‐16, fig 1). At the age of 38, II.2 had a large aneurysm of the sinuses of Valsalva and of the ascending aorta,8,9,10 as demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomographic angiography (table 1), which was repaired using an aortic graft and valvoplasty. One year later, he developed aortic insufficiency requiring aortic valve replacement. His skin was of normal texture with barely noticeable skin laxity, which had been reported to be more evident on the lower face and submandibular area during childhood. He had a single palmar crease bilaterally and limited ability to supinate both forearms. II.3 died at age 26 of aortic dissection with no other apparent systemic involvement. He had no apparent skin laxity pictures taken in childhood and during adult life. Both I.1 and III.1 had a mildly dilated aortic root8,9,10 (table 1), mild aortic insufficiency, and obvious cutis laxa, with a velvety texture to the skin by palpation and with redundancy of skin on the face, submandibular area, trunk, and to a milder degree on the extremities. Pulmonary function testing of III.1 at the age of 11 years indicated overall normal function (forced expiratory volume in one second, 96% of predicted) with mildly increased residual volume (152% of predicted). He also had a history of prolonged wound healing. I.1, II.2, and III.1 all had history of inguinal hernias repaired surgically. Patient III.1 was treated with atenolol 50 mg daily to delay progression of aortic dilatation and the development of aneurysm.

Figure 1 The pedigrees of families CL‐16 and CL‐13.

Table 1 Aortic diameters in mutation carriers in CL‐16.

| Ann (mm) | Sinus (mm) | Asc (mm) | Trans (mm) | Desc (mm) | Aortic insuff | Age (years) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III.1 | 26 | 34 | 26 | 11 | 10 | Mild | 8 | 138.5 | 56.7 | |||||||||

| II.2 | *66 to 72 | *52 to 58 | Severe | 39 | 177.8 | 99.9 | ||||||||||||

| I.1 | 23 | 30 | 34 | 26 | 20 | Mild | 71 | 141.5 | 63.5 |

Normal values for aortic sinus measurements should not exceed 32 mm up to 2 m2 body surface area (II. 2) and at 1.6 m2 (III.1 and I.1) the normal range is 22 to 29 mm.8 Supra‐aortic ridge or ascending aorta long axis view echocardiographic measurements should not exceed 25 mm and 28 mm respectively at up to 2 m2.9 * II.2 aortic sinuses measured 66–72 mm on transoesophageal echo and ascending aorta 52–58 mm on computed tomography depending on view. Normal aortic root for age 46 +/− 13 years = 32 +/− 3 mm.10

Ann, aortic annulus; Asc, ascending aorta; Desc, descending aorta; insuff, insufficiency; Trans, transverse aorta.

An unrelated Singaporean girl of Chinese descent with no family history of cutis laxa (CL‐13) was noticed at birth to have marked laxity of the skin. Physical features included loose folds of redundant skin over the face and jowls, trunk, and over the upper and lower limbs. The hair was sparse, and she had tear shaped eyes, with prominent anteverted ears, a long philtrum, and a flattened nasal bridge. At the age of 5 years 9 months an echocardiogram showed significant dilatation of the aortic root at the level of the sinuses of Valsalva8,9,10 with a measured diameter of 2.47 cm (normal <2.2 cm for her body surface area). There was no aortic regurgitation and the ascending aorta was of normal size. She was treated with atenolol 25 mg daily.

Pathology

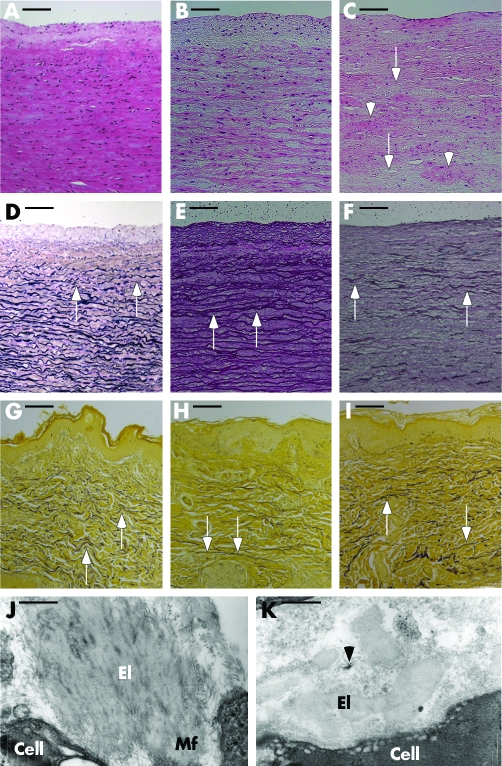

Aneurysmal aortic samples (aAo) obtained from family CL‐16, patient II.2 showed reduced wall thickness (1 to 1.5 mm), approximately 50% of adjacent non‐aneurysmal (nAo) tissue (2.5 to 3 mm). Haematoxylin‐eosin staining of aAo showed focal paucity and clumping of smooth muscle cells (fig 2C) characteristic of medial degeneration,11 and nAo patient samples indicated slightly reduced cellularity (fig 2B) compared with a normal control (fig 2A). Inflammatory infiltrates or atheromatous changes were not apparent in any of these specimens. Elastin staining in normal aorta showed dense, wavy elastic lamellae (fig 2D). In contrast, elastic fibres appeared stretched and fewer in nAo (fig 2E) and were destroyed, leaving only a few scattered fragments in aAo (fig 2F). Hart's staining of skin samples from CL‐13, II.1 (fig 2H) showed thin elastic fibres, whereas staining intensity in CL‐16, III.1 (fig 2I) was comparable to control (fig 2G). In both cutis laxa skin samples the normal waviness of deep elastic fibres was diminished. Electron microscopy in controls showed abundant microfibrillar bed surrounding dermal elastic fibres (fig 2J). In contrast, elastic fibres in the skin of CL‐16, III.1 lacked associated microfibrils (fig 2K).

Figure 2 Aortic and dermal pathology in cutis laxa. Haematoxylin‐eosin staining of a normal control (A, 29 year old white male), non‐aneurysmal (B, nAo) and aneurysmal (C, aAo) segments of the aorta of patient CL‐16, II.2 (38 years). Focal cell paucity (arrows) and cell clumping (arrowheads) is seen in aAo (C). Verhoeff van Giesson elastin stain of sections a from normal control (D, 15 year old African American male) shows dense, wavy elastic lamellae. In nAo , the elastic fibres are irregular and stretched (E, arrows). In aAo only fragments of the lamellae remain (F, arrows). Hart's elastin stains (G, H) of a normal skin section (G, 9 year old male) shows thick, horizontal, undulating elastic fibres in the deep dermis (arrows) and fine, perpendicular fibres in the papillary dermis. In the skin of CL‐13, II.1 (H, 6 year old Asian female) the deep dermal elastic fibres are thin and straight (arrows) whereas in CL‐16, III.1 (I, 12 year old male) the fibres are of normal thickness but lack the normal wavy character (arrows). Electron microscopy of the skin in normal control skin (J) shows abundant microfibrillar component, both at the periphery (Mf) of, and as inclusions in a mature elastic fibre (El). In contrast, elastic fibres (El) in the proband's skin (CL‐16, III.1) are not associated with the appropriate amount and localisation of microfibrils (K). A small bundle of microfibrils is seen disjoined from the elastic fibre (arrowhead). Magnification bars (A)–(I), 100 μm; (J) and (K), 483 nm.

Mutational results

Direct sequence analysis of ELN in CL‐16, III.1 uncovered a 25 bp deletion in exon 30, 2114_2138del. This defect was present in all affected members of the family available for testing, including I.1 and II.2. The mutation was not found in II.1. Direct sequence analysis also uncovered mutation 2159delC, also in exon30 of ELN, in CL‐13, II.1 which was absent in both of her unaffected parents (I.1 and I.2) indicating that 2159delC was a de novo mutation. Screening of 121 normal control individuals was negative for both 2114_2138del and 2159delC.

Expression of mutations 2114_2138del and 2159delC

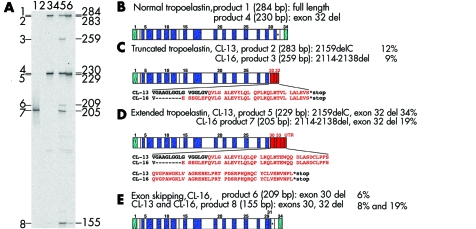

To analyse the effect of mutations 2114_2138del and 2159delC on elastin biosynthesis, we carried out RT‐PCR experiments using total RNA from mutant and normal control fibroblasts (fig 3A). Normal cells expressed two mRNA species as a result of alternative splicing of exon 32 (fig 3B). The same products were also observed in cutis laxa cells corresponding to products of the normal allele in heterozygotes. Cutis laxa cells also expressed multiple mutant mRNA forms that had similar structures in both CL‐13 and CL‐16 (fig 3, C–E). Inclusion of either of the two mutations in the full length mRNA resulted in frame shifts and subsequent and premature termination codons in a sequence encoded by exon 32 (fig 3C). Inclusion of the mutations and the removal of exon 32 by alternative splicing resulted in the same frame shift with a C‐terminally extended open reading frame (fig 3D). Finally, both mutations induced illegitimate skipping of the constitutive exon 30 (fig 3E). The relative proportions of these mutant mRNAs were different between CL‐13 and CL‐16. The C‐terminally extended product was the most abundant in CL‐13 (fig 3D) and exon 30 skipping products were the most abundant in CL‐16 (fig 3E).

Figure 3 Mutant elastin mRNA isoforms in CL‐13 and CL‐16. (A) Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) amplification of RNA samples from normal control and mutant fibroblasts: lane 1, plasmid positive control; lane 2, no template negative control; lane 3, normal control sample; lane 4, no reverse transcription negative control; lane 5, mutant (CL16, II.2) sample; lane 6, mutant (CL13) sample. Positions and sizes of fragments are shown on the right in base pairs. RT‐PCR products with an abundance of >1% of total are numbered on the left. (B) Domain structure of normal tropoelastin. (C) Domain structure of predicted mutant tropoelastins containing a premature termination codon in exon 32 (products 2 and 3). Exons (30–32) encoding a C‐terminal missense peptide as a result of the frame shift introduced by the mutations are shown in red. The sequence of the missense peptide sequence is shown below the diagram for each mutation. (D) Domain structure of predicted mutant tropoelastin with an extended open reading frame. Sequences (exons 30, 31, 33, 34, and 3′‐UTR) encoding a C‐terminal missense peptide as a result of the frame shift introduced by mutations 2159delC (product 5) and 2114_2138del (product 7) are shown in red. (E) Domain structure of predicted mutant tropoelastin isoforms lacking constitutive exon 30 (products 6 and 8). Per cent values indicate the abundance of each isoform relative to total elastin mRNA abundance in the corresponding samples (100%).

Discussion

Our studies show for the first time that ELN mutations associated with cutis laxa may cause aortic lesions ranging from mild dilatation to severe aneurysm and rupture of the aortic root. Variable expression of cutis laxa, hernias, and aortic lesions was observed in a family with autosomal dominant cutis laxa, and mild aortic dilatation was found in a sporadic patient with severe cutis laxa. The aortic pathology associated with this condition is medial degeneration, characterised by dramatic loss of elastic lamellae and smooth muscle cells and a lack of atherosclerotic and inflammatory lesions.11 These findings emphasise the importance of cardiovascular monitoring to prevent fatal rupture of the aortic root in cutis laxa patients.

The aortic lesions documented in this study are highly similar to the aortic disease associated with Marfan syndrome. Both are characterised by (1) variable expression, (2) localisation of the lesions to the aortic root, and (3) the pathology of medial degeneration. Aortic root aneurysms in Marfan syndrome are thought to be caused by the loss or weakening of microfibrils anchoring medial smooth muscle cells to elastic lamellae, leading to phenotypic alteration of smooth muscle cells, destruction of lamellae, and a loss of aortic wall integrity.12 Electron microscopic observation of disrupted microfibril–elastin interactions in our study suggest that aortic lesions in cutis laxa may have a shared pathomechanism with aneurysms in Marfan syndrome in addition to the clinical and pathological similarities demonstrated here.

How can mutations in ELN disrupt microfibril–elastin interactions? Our recent studies demonstrating synthesis and matrix incorporation of mutant tropoelastin in cutis laxa patients have provided an insight into this question.5 Deposition of a mixture of normal and mutant elastin may increase the protease susceptibility of this protein polymer, leading to the destruction of molecules important for microfibril–elastin interaction. Alternatively, mutant elastin may interfere with such interactions in a dominant negative manner. The present study is consistent with the synthesis of an abnormal protein, as mRNA products of the mutant and normal alleles were found in equal abundance. Both mutations reported here result in the synthesis of several stable mutant mRNA species, including isoforms that encode an extended hydrophilic C‐terminal missense peptide sequence, lack constitutive exon 30, or have truncated open reading frames.

Our studies provide evidence for the involvement of ELN mutations in the development of cutis laxa and severe thoracic aortic aneurysms. Dramatic disappearance of elastic fibres in aneurysmal lesions also implicates ELN as a candidate gene for inherited aneurysmal diseases. It remains to be shown whether ELN may be mutated in patients with familial, non‐syndromic thoracic aortic aneurysms or whether ELN may be a susceptibility gene for aneurysmal diseases of complex inheritance. The latter is supported by some genetic mapping and association studies on intracranial aneurysms.13,14

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant HL73703 (ZU) and by core support through NIH grant RR16453 (ZU). We appreciate the cooperation of the patients and family members participating in this study. We thank Dr Kathleen Patterson for the expert pathological evaluation of CL skin samples.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the United States Department of Defense.

Abbreviations

aAo - aneurysmal aortic tissue

CL - cutis laxa

nAo - non‐aneurysmal aortic tissue

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared

References

- 1.Beighton P. The dominant and recessive forms of cutis laxa. J Med Genet 19729216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez‐Revenga L, Iranzo P, Badenas C, Puig S, Carrio A, Mila M. A novel elastin gene mutation resulting in an autosomal dominant form of cutis laxa. Arch Dermatol 20041401135–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tassabehji M, Metcalfe K, Hurst J, Ashcroft G S, Kielty C, Wilmot C, Donnai D, Read A P, Jones C J. An elastin gene mutation producing abnormal tropoelastin and abnormal elastic fibres in a patient with autosomal dominant cutis laxa. Hum Mol Genet 199871021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang M C, He L, Giro M, Yong S L, Tiller G E, Davidson J M. Cutis laxa arising from frameshift mutations in exon 30 of the elastin gene (ELN). J Biol Chem 1999274981–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urban Z, Gao J, Pope F M, Davis E C. Autosomal dominant cutis laxa with severe lung disease: synthesis and matrix deposition of mutant tropoelastin. J Invest Dermatol 20051241193–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrmann B G, Frischauf A M. Isolation of genomic DNA. Methods Enzymol 1987152180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urban Z, Michels V V, Thibodeau S N, Donis‐Keller H, Csiszar K, Boyd C D. Supravalvular aortic stenosis: a splice site mutation within the elastin gene results in reduced expression of two aberrantly spliced transcripts. Hum Genet 1999104135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roman M J, Devereux R B, Kramer‐Fox R, O'Loughlin J. Two‐dimensional echocardiographic aortic root dimensions in normal children and adults. Am J Cardiol 198964507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snider A R, Enderlein M A, Teitel D F, Juster R P. Two‐dimensional echocardiographic determination of aortic and pulmonary artery sizes from infancy to adulthood in normal subjects. Am J Cardiol 198453218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasan R S, Larson M G, Benjamin E J, Levy D. Echocardiographic reference values for aortic root size: the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 19958793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erdheim J. Medionecrosis aortae idiopathica cystica. Virchows Arch Path Anat 1930276187 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunton T E, Biery N J, Myers L, Gayraud B, Ramirez F, Dietz H C. Phenotypic alteration of vascular smooth muscle cells precedes elastolysis in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Circ Res 20018837–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruigrok Y M, Seitz U, Wolterink S, Rinkel G J, Wijmenga C, Urban Z. Association of polymorphisms and haplotypes in the elastin gene in Dutch patients with sporadic aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2004352064–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onda H, Kasuya H, Yoneyama T, Takakura K, Hori T, Takeda J, Nakajima T, Inoue I. Genomewide‐linkage and haplotype‐association studies map intracranial aneurysm to chromosome 7q11. Am J Hum Genet 200169804–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]