Abstract

Objectives

To collect information on the involvement, legal understanding and ethical views of preregistration house officers (PRHO) regarding end‐of‐life decision making in clinical practice.

Design

Structured telephone interviews.

Participants

104 PRHO who responded.

Main outcome measures

Information on the frequency and quality of involvement of PRHO in end‐of‐life decision making, their legal understanding and ethical views on do‐not‐resuscitate (DNR) order and withdrawal of treatment.

Results

Most PRHO participated in team discussions on the withdrawal of treatment (n = 95, 91.3%) or a DNR order (n = 99, 95.2%). Of them, 46 (44.2%) participants had themselves discussed the DNR order with patients. In all, it was agreed by 84 (80.8%) respondents that it would be unethical to make a DNR order on any patient who is competent without consulting her or him. With one exception, it was indicated by the participants that patients who are competent may refuse tube feeding (n = 103, 99.0%) and 101 (97.1%) participants thought that patients may refuse intravenous nutrition. The withdrawal of artificial ventilation in incompetent patients with serious and permanent brain damage was considered to be morally appropriate by 95 (91.3%) and 97 (93.3%) thought so about the withdrawal of antibiotics. The withdrawal of intravenous hydration was considered by 67 (64.4%) to be morally appropriate in this case.

Conclusions

PRHO are often involved with end‐of‐life decision making. The results on ethical and legal understanding about the limitations of treatment may be interpreted as a positive outcome of the extensive undergraduate teaching on this subject. Future empirical studies, by a qualitative method, may provide valuable information about the arguments underlying the ethical views of doctors on the limitations of different types of medical treatment.

The ethical aspects of decisions taken at the end of life are frequently discussed in public and academic debates. Empirical evidence shows that doctors are confronted with end of life decisions at an early stage of their professional career.1,2,3 After the recommendation of the General Medical Council on undergraduate medical education,4 medical schools in Britain have implemented teaching sessions on ethical, legal and communication aspects related to end‐of‐life decisions in medicine.5 Little systematic research exists, however, about the involvement of junior doctors in end‐of‐life decision making, and their legal understanding and ethical views on this issue.

Research in this subject is warranted for several reasons. Firstly, data about the involvement of junior doctors in end‐of‐life decision making provide insight into current clinical practice and thereby inform the debate on ethical standards. Secondly, findings on the legal understanding and ethical views of junior doctors on end‐of‐life decisions may serve as an indicator for the outcome of undergraduate teaching.

This study presents the data from interviews with preregistration house officers (PRHO) about practical, legal and ethical aspects of end‐of‐life decision making. All the PRHO had graduated from one London medical school and received a substantial amount of training on end‐of‐life decisions, including communication skills, and ethics and law applied to medicine. This included interactive lectures, experiential learning using training videos, role plays, simulated patients and small group discussions. The aims of the study were to

elicit the extent of PRHO involvement in the process of end‐of‐life decision making;

identify their legal understanding about end‐of‐life decision making; and

identify their views on ethical aspects of end‐of‐life decision making.

The findings are discussed in the light of the existing standards of good medical practice and the current guidance on undergraduate and postgraduate medical education.

Methods

Two research assistants (SW and AH) contacted, via telephone, all 139 former students who had graduated from one London medical school during the final 2 months of their time as PRHO in one of the hospitals affiliated to the university. The research assistants were not associated with any of the teaching activities for the students. In accordance with the requirement of the local research ethics committee, the interviewers first explained the purpose of the survey. Confidentiality was assured. PRHO willing to participate in the study were asked to give oral informed consent. Data were collected on questionnaires without recording any identifiable information. The questions were formulated by two of the authors (JS, AC), and were based on a review of literature published on empirical studies about doctors' knowledge and views on legal and ethical aspects of end‐of‐life decision making. The questionnaire contained 41 items, which were formulated either as closed‐ended multiple choice questions or as statements. In the statements, respondents could indicate their agreement or disagreement on a 5‐point Likert Scale with “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree” as the two extremes of the scale. A first version of the questionnaire was used in a pilot study on PRHO who had graduated from other medical schools. Minor changes in wording and layout of the instrument were made as a result of this test.

Results

Of the 139 PRHO, six who appeared on the list, as trainees in one of the affiliated hospitals were not in post. In all, 104 (78%) PRHO agreed to participate in the study. Of them, 43.3% were men and 46.2% women. In 11 cases, the sex of the PRHO was not recorded. The average age was 25.6 years (minimum, 23 years and maximum, 33 years).

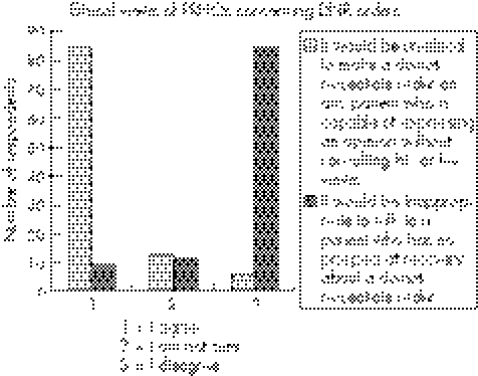

A total of 87 (83.7%) PRHO had observed situations in which other doctors had discussed aspects of withdrawal of treatment with their patients and 97 (93.3%) had observed discussions between doctors and relatives about the ending of treatment. Most respondents had been part of team discussions about the withdrawal of treatment (n = 95, 91.3%) or a do‐not‐resuscitate (DNR) order (n = 99, 95.2%). In all 46 (44.2%) participants had themselves discussed the DNR order with patients and 71 (68.3%) had discussed this issue with relatives; 4 (3.8%) PRHO indicated that they had made a decision about a DNR order without consulting a senior doctor. Figure 1 summarises the views of the PRHO about good clinical practice on DNR orders. A total of 84 (80.8%) respondents agreed that it would be unethical to make a DNR order on any patient who is competent without consulting her or him, whereas 84 (80.8%) respondents disagreed with the statement that it would be inappropriate to talk to a patient who has no prospect of recovery about a DNR order.

Figure 1 Ethical views of preregistration house officers (PRHO) on the involvement of patients in decisions on do‐not‐resuscitate (DNR) orders.

Most (n = 99, 95.2%) respondents were aware of the rights of patients who are competent to refuse artificial ventilation; 4.8% denied that patients might refuse such treatment. With one exception, the participants indicated that patients who are competent (n = 103, 99%) might refuse tube feeding; 101 (97.1%) PRHO thought that patients who are competent may refuse intravenous nutrition and 100 (96.2%) stated that such patients might refuse intravenous hydration.

Table 1 summarises the results with respect to the understanding of the PRHO' of the current legal situation about withdrawal of treatment in the case of an incompetent patients with serious and permanent brain damage with no capacity for self‐directed activity. Whereas 98 (94.2%) respondents thought that artificial ventilation might be legally withdrawn in this situation, only 68 junior doctors (65.4%) thought so with respect to intravenous hydration.

Table 1 The statements of preregistration house officers on the legality of withdrawal of treatment in a seriously and permanently brain‐damaged patient with no capacity for self‐directed activity.

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| From what you know, which of the following treatments may be legally withdrawn in a patient with serious and permanent brain damage (eg, with no capacity for self‐directed activity)? | ||

| Artificial ventilation | 98 (94.2%) | 4 (3.8%) |

| Antibiotics | 96 (92.3%) | 6 (5.8%) |

| Tube feeding | 91 (87.5%) | 11 (10.6%) |

| Nutrition (intravenous) | 91 (87.5%) | 11 (10.6%) |

| Hydration (intravenous) | 68 (65.4%) | 34 (32.7%) |

PRHO were also asked about their ethical views on the withdrawal of treatment in the case of an incompetent patient with serious and permanent brain damage with no capacity for self‐directed activity. Most considered withdrawal of artificial ventilation (n = 95, 91.3%) or antibiotics (n = 97, 93.3%) to be morally appropriate in this situation. A smaller proportion of the participants (n = 67, 64.4%) considered the withdrawal of intravenous hydration to be morally appropriate (table 2).

Table 2 Ethical views of preregistration house officers on withdrawal of treatment in a patient with serious and permanent brain damage with no capacity for self‐directed activity.

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| In your opinion is it morally appropriate to withdraw the following treatment in a patient with serious and permanent brain damage (eg, with no capacity for self‐directed activity)? | ||

| Artificial ventilation | 95 (91.3%) | 9 (8.7%) |

| Antibiotics | 97 (93.3%) | 7 (6.7%) |

| Tube feeding | 91 (87.5%) | 13 (12.5%) |

| Nutrition (intravenous) | 87 (83.7%) | 17 (16.3%) |

| Hydration (intravenous) | 67 (64.4%) | 37 (35.6%) |

Discussion

The study provides detailed information about the involvement, legal understanding and moral views on end‐of‐life decisions of 104 graduates from one London medical school who had worked for almost 1 year as PRHO. Given the good response rate, the results can be interpreted as representative of the experiences and views of the PRHO who graduated from this medical school, having had core training on communication skills, and ethical and legal aspects of end‐of‐life decision‐making. Our findings cannot necessarily be extrapolated to the experiences and views of PRHO who graduated from other medical schools in the UK or in other countries.

The data provide information about current clinical practice with respect to the involvement of PRHO in the process of end‐of‐life decision‐making. Most PRHO (83.7%) had observed discussions between patients and doctors on aspects of withdrawal of treatment and 91.3% participated in team discussions on this issue. The participation of young doctors in the process of end‐of‐life decisions may serve organisational and educational purposes. As with the process of informed consent for medical procedures, we would argue that junior doctors should participate in discussions on end‐of‐life decision making at an early stage of their career to develop competency in handling this difficult aspect of clinical practice in a professional manner.7 However, PRHOs should not obtain consent on their own. Equally to comply with the current standards for good clinical practice, however, junior doctors need supervision and institutions need to make sure that a clinically experienced consultant or general practitioner has the final responsibility for any decision about the end of life.8 The results do not indicate whether PRHO participating in end‐of‐life decisions and the discussions about the issue with patients and relatives have been supervised by senior colleagues. As with the involvement of PRHO in any other medical procedure, those responsible for postgraduate training on the wards must ensure by means of supervision and further teaching that junior doctors participating in discussions on end‐of‐life decisions are competent to do so. The PRHO taking part in this study were formally taught guidance on good clinical practice and trust policy during their undergraduate course. Given the explicit teaching they have had, it is worrying that a small minority said that they had made a DNR decision without consulting a senior doctor. It must be clear to junior doctors and those responsible for continuing medical education on the wards that such behaviour is far from being legal and ethically acceptable practice.

This study could not provide information about the competencies of PRHO on discussions on end‐of‐life decisions with patients and relatives. Data from previous published studies indicated that junior doctors perceive themselves to be competent to discuss difficult issues such as DNR orders or bad news with their patients.3,6 The participants may have overestimated their competence, however, and therefore it will be necessary to undertake observational studies to assess this.2

Most respondents support the participation of patients in the decision‐making process on DNR orders. This view corresponds with the guidance of the British Medical Association on decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Patients who are competent should be included in these decisions “because patients' own views about the level of burden or risk they consider acceptable carry considerable weight in deciding whether treatment is given … ”.8

Controversial views exist among medical practitioners on whether patients should be included in decisions on DNR codes. The increasing wish of patients to be included in medical decisions, and discrepancies between quality‐of‐life judgements made by patients and third parties are arguments that are brought forward by the proponents of the patients' right to make these decisions.9 Opponents argue that these discussions may destroy hope, which patients need to maintain at the end of their lives.10

Most PRHO knew that patients who were competent may refuse even life‐saving procedures and that treatment may be limited lawfully in the case of patients who are seriously and permanently brain damaged and unable to engage in self‐directed activity with no prospects of recovery. Like the other results this may be interpreted as a positive outcome of the extensive undergraduate teaching on this subject. One limitation of the study is the lack of baseline data before the introduction of the ethics and law curriculum. Hence, our results do not show whether the courses had any demonstrable effect on improving the knowledge of the PRHO on the rights of patients to refuse life‐sustaining treatment, although the experience of the lecturer teaching them suggests that this is so.

Even though the former students had been taught that there are circumstances in which nutrition and hydration may be legally withdrawn like other medical treatment—for example, in the case of a permanent vegetative state with court approval and possibly in some cases of other extremely serious and permanent neurological injury without such approval—a third of the respondents still believed that the withdrawal of intravenous hydration was generally illegal.11 One explanation for the result may be the confusion generated by the wording of the question, which unfortunately did not explicitly differentiate between patients in a permanent vegetative state—which in light of the undergraduate teaching the PRHOs should have had in mind—and other forms of extreme and permanent neurological damage where they had been taught that the stituation was legally ambiguous. For this reason the meaning of the results in table 1 concerning the legality of withdrawal of hydration and nutrition is unclear and should be discounted. Equally in table 2, 64.4% of the respondents considered the withdrawal of intravenous hydration to be morally inappropriate, even presumably for permanent vegetative state.

The similarity between this result and the corresponding figure in table 1 (65.4%) concerning the legality of withdrawal of hydration is striking. This suggests that a significant proportion of respondents believe that there is a fundamental moral difference between the withdrawal of hydration and the withdrawal of other forms of lifesaving treatment and that this belief may have influenced their legal understanding of withdrawal hydration.12 It must be admitted that without further information, it is impossible to know how to interpret this apparent anomalous result in the responses of the PRHO'. This further reinforces the importance of future empirical studies, which may provide valuable information about the rationale and individual motives underlying the ethical views of doctors with respect to the non‐provision and withdrawal of life‐sustaining treatment. For example, we certainly need to know more about disagreements about the legality and morality of withdrawing hydration in relation to other forms of life‐sustaining treatment.

Acknowledgements

Jan Schildmann's post was supported by the Johannes and Frieda Marohn Stiftung of the Friedrich‐Alexander‐University Erlangen‐Nuremberg (Germany). The authors would like to thank Ms Stefanie Wand (SW) and Ms Alex Higgins (AH) for conducting the telephone interviews with the Pre Registration House Officers.

Abbreviations

DNR - do not resuscitate

PRHO - preregistration house officers

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Fallowfield L. An unmerciful end. Decisions not to resuscitate must not be left to junior doctors. BMJ 20013231131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tulsky J A, Chesney M A, Lo B. How do medical residents discuss resuscitation with patients? J Gen Intern Med 199510436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tulsky J A, Chesney M A, Lo B. See one, do one, teach one? House staff experience discussing do‐not‐resuscitate orders. Arch Intern Med 19961561285–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.General Medical Council Tomorrow's doctors. Recommendations on undergraduate medical education. London: GMC, 1993

- 5.Field D, Wee B. Preparation for palliative care: teaching about death, dying and bereavement in UK medical schools 2000–1. Med Educ 200236561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schildmann J, Cushing A, Doyal L.et al Breaking bad news: experiences, views and difficulties of pre‐registration house officers. Palliat Med 20051993–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paice E, Aitken M, Moss F. Informed consent and the preregistration house officer. Hosp Med62699–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.British Medical Association Decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation. A joint statement from the British Medical Association, the Resuscitation Council (UK) and the Royal College of Nursing. http://www.bma.org.uk/ap.nsf/Content/cardioresus (accessed 20 November 2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Higginson I J. Doctors should not discuss resuscitation with terminally ill patients: AGAINST. BMJ 2003327615–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manisty C, Waxman J. Doctors should not discuss resuscitation with terminally ill patients: FOR. BMJ 2003327614–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.British Medical Association Medical ethics today. 2nd edn. London: BMJ Books, 2001358–360.

- 12.Keown J. Restoring moral and intellectual shape to the law after Bland. Law Q Rev 1997113481–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]