Abstract

The SHR3 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes an integral membrane component of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) with four membrane-spanning segments and a hydrophilic, cytoplasmically oriented carboxyl-terminal domain. Mutations in SHR3 specifically impede the transport of all 18 members of the amino acid permease (aap) gene family away from the ER. Shr3p does not itself exit the ER. Aaps fully integrate into the ER membrane and fold properly independently of Shr3p. Shr3p physically associates with the general aap Gap1p but not Sec61p, Gal2p, or Pma1p in a complex that can be purified from N-dodecylmaltoside-solubilized membranes. Pulse–chase experiments indicate that the Shr3p–Gap1p association is transient, a reflection of the exit of Gap1p from the ER. The ER-derived vesicle COPII coatomer components Sec13p, Sec23p, Sec24p, and Sec31p but not Sar1p bind Shr3p via interactions with its carboxyl-terminal domain. The mutant shr3-23p, a nonfunctional membrane-associated protein, is unable to associate with aaps but retains the capacity to bind COPII components. The overexpression of either Shr3p or shr3-23p partially suppresses the temperature-sensitive sec12-1 allele. These results are consistent with a model in which Shr3p acts as a packaging chaperone that initiates ER-derived transport vesicle formation in the proximity of aaps by facilitating the membrane association and assembly of COPII coatomer components.

INTRODUCTION

At an early stage in the secretory pathway, secreted and integral plasma membrane (PM) proteins are transported from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the Golgi apparatus via ER-derived transport vesicles (reviewed by Rothman and Wieland, 1996; Schekman and Orci, 1996; Barlowe, 1998). In vitro studies have shown that a set of cytosolic proteins (Sar1p, Sec23p–Sec24p complex, and Sec13p–Sec31p complex) coordinately function to catalyze the formation of ER transport vesicles (Salama et al., 1993). These components associate with the ER membrane via interactions with ER membrane proteins, e.g., Sec12p and Sec16p (Nakano et al., 1988; d’Enfert et al., 1991; Espenshade et al., 1995; Shaywitz et al., 1997), and oligomerize to form a vesicle coat structure known as COPII (Barlowe et al., 1994). Coat assembly is thought to provide the force required for vesicle formation, and it is the COPII component subunit interactions that determine the geometry and size of COPII-coated vesicles. Proteins destined for transport away from the ER are separated from resident ER proteins concomitantly with the formation of COPII vesicle buds (reviewed by Bednarek et al., 1996). There exists in vitro data suggesting that COPII components are responsible and sufficient for cargo selection (Aridor et al., 1998; Matsuoka et al., 1998a; Springer and Schekman, 1998).

SHR3 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes an integral ER membrane protein of 210 amino acids that is required for functional expression of amino acid permeases (aaps) (Ljungdahl et al., 1992). In cells lacking SHR3, aaps accumulate within the ER membrane and do not reach the PM. Evidence for this is based on 1) amino acid uptake studies, 2) subcellular fractionation and immunolocalization studies, and 3) in vitro packaging studies using yeast membrane preparations and purified COPII components. The secretory block imposed by shr3 mutations is specific for the 18 members of the aap gene family, a group of structurally related polytopic membrane proteins each containing 12 potential membrane spanning domains (André, 1995). The general secretory and vacuolar targeting pathways are unaffected in shr3 null mutant cells (Ljungdahl et al., 1992; Horák and Kotyk, 1993; Kuehn et al., 1996). In vitro studies have demonstrated that Shr3p is required for the packaging of the general aap (Gap1p) and the histidine-specific permease (Hip1p) but is itself not incorporated into COPII-coated transport vesicles (Kuehn et al., 1996). In vitro, Gap1p and Hip1p have been shown to bind to a complex comprising a subset of COPII components in an Shr3p-dependent manner (Kuehn et al., 1998). The specificity of Shr3p for aaps implies that one or more regions of sequence or structural similarity shared by aaps represent a signature domain that is recognized by Shr3p in carrying out its function. This recognition is a prerequisite for the entry of the entire aap gene family of polytopic membrane proteins into ER-derived COPII transport vesicles.

Shr3p may act as a “typical” chaperone specific for aaps, influencing their membrane conformation, posttranslational assembly, or activity. It has been observed that different membrane proteins, translocation substrates, exhibit different requirements for components of the translocation apparatus. The possibility exists that aaps may follow a discrete and presently ill-defined translocation pathway as they insert into the ER membrane and that Shr3p performs a specific function required for the efficient translocation and full integration of aaps into the ER membrane. Gene fusion experiments using the arginine-specific aap (Can1p) established that Sec70p and previously known components Sec61p and the Sec62p–Sec63p complex (which includes Sec71p and Sec72p) are required for proper insertion of Can1p into the ER membrane (Green et al., 1989; Green et al., 1992; Green and Walter, 1992). Despite being present in stoichiometric amounts within the Sec62p–Sec63p complex (Deshaies et al., 1991), Sec62p is not required for the membrane insertion of Can1p fusion constructs (Green et al., 1992). Similarly, the originally isolated sec71 and sec72 mutations affect only the translocation of a subset of proteins into the ER membrane (Green et al., 1992). Despite the lack of sequence homology with known folding proteins, Shr3p may participate in an aap-specific folding reaction that is required for aaps to enter into subsequent stages of the secretory pathway.

Alternatively, Shr3p may function at subsequent stages after aaps have attained their native conformations to facilitate their entry into COPII transport vesicles. There is accumulating evidence that ER sorting determinants exist in yeast (Schimmöller et al., 1995; Belden and Barlowe, 1996; Elrod-Erickson and Kaiser, 1996; Powers and Barlowe, 1998) and in other organisms (Fiedler et al., 1996; Annaert et al., 1997). Yeast cells lacking EMP24 or ERV25 secrete invertase (Suc2p) and glucosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored PM protein (Gas1p) at reduced rates from the ER. The diminished rates of Suc2p and Gas1p secretion in emp24 null mutants are not due to the misfolding or incorrect oligomerization of these proteins. Emp24p and Erv25p are members of a p24 family of proteins (Fiedler et al., 1996) that associate with one another and are packaged into COPII vesicles (Belden and Barlowe, 1996). Although no direct interactions with cargo proteins have been demonstrated, p24 proteins may function to sort and/or concentrate selected proteins for transport, acting as cargo receptors (Schimmöller et al., 1995; Belden and Barlowe, 1996). Integral polytopic membrane proteins may also depend on specific ancillary proteins for entry into ER vesicle bud sites. It has been shown that variations in the assay concentrations of certain COPII components affect the membrane cargo composition of transport vesicles generated in vitro (Campbell and Schekman, 1997). These studies indicate that conditions that block the efficient assembly of COPII coat components primarily reduce the rate of membrane protein cargo packaging without affecting the packaging of soluble cargo.

In this paper we describe experiments that test possible Shr3p functions during the early stages of the secretory pathway. Our findings reveal that Gap1p, an archetypal aap, is translocated into the ER membrane and attains its correct membrane topology in the absence of SHR3. In contrast to mutations that result in Gap1p misfolding, the aaps that accumulate in the ER membrane of shr3 mutants do not activate the ER stress response pathway; thus it is unlikely that Shr3p functions as an aap-specific foldase. Specific genetic interactions suggest that Shr3p facilitates processes leading to COPII coat assembly. Consistent with the genetic data, we have observed that COPII coatomer components Sec13p, Sec23p, Sec24p, and Sec31p but not Sar1p are able to bind Shr3p via interactions requiring the presence of the hydrophilic carboxyl-terminal domain of Shr3p. Shr3p physically associates with Gap1p in a complex that can be purified from N-dodecylmaltoside (DM)-solubilized membrane preparations. Pulse–chase analysis indicates that the Shr3p–Gap1p complex is the result of transient interactions within the ER membrane. On the basis of these results, we propose that Shr3p acts as a packaging chaperone that facilitates the initiation of ER vesicle formation in close proximity to fully integrated and correctly folded aaps.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and Microbiological Techniques

Yeast strains are listed in Table 1, and plasmids used are listed in Table 2. Strains PLY1 and FGY58 were transformed with a linear EcoRI–SalI fragment of DNA containing shr3Δ5::hisG-URA3-neo-hisG from pPL288, two Ura+ transformants were propagated on medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid to attain the unmarked shr3Δ6 deletion resulting in strains FGY145 and FGY60, respectively. Strains FGY58 and FGY60 were transformed with a linear SphI–SalI fragment of DNA containing suc2Δ100::hisG-URA3-neo-hisG from pFG40, Southern analysis was used to confirm correct integration of the suc2Δ100 allele, two Ura+ transformants were propagated on medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid to attain the unmarked suc2Δ101 deletion resulting in strains FGY84 and FGY85.

Table 1.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| PLY1 | MATa ura3-52 his4Δ29 GAL+ | Ljungdahl et al., 1992 |

| FGY145 | MATa ura3-52 his4Δ29 shr3Δ6 GAL+ | This work |

| Isogenic derivatives of AA288 | ||

| AA288 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 lys2Δ201 ade2 | Antebi and Fink, 1992 |

| PLY129 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 lys2Δ201 ade2 gap1Δ∷LEU2 | Ljungdahl et al., 1992 |

| PLY144 | MATa ura3-52 ade2 lys2Δ201 | This work |

| PLY147 | MATα ura3-52 ade2 lys2Δ201 | This work |

| PLY151 | MATa ura3-52 ade2 lys2Δ201 shr3Δ1∷URA3 | This work |

| PLY155 | MATα ura3-52 ade2 lys2Δ201 shr3Δ1∷URA3 | This work |

| FGY58 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 lys2Δ201 ade2 gap1Δ∷LEU2 | This work |

| FGY60 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 lys2Δ201 ade2 gap1Δ∷LEU2 shr3Δ6 | This work |

| FGY84 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 lys2Δ201 ade2 gap1Δ∷LEU2 suc2Δ101 | This work |

| FGY85 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 lys2Δ201 ade2 gap1Δ∷LEU2 shr3Δ6 suc2Δ101 | This work |

| Original sec− mutant strains | ||

| CKY42 | MATa ura3-52 sec12-1 | Kaiser laboratory |

| CKY45 | MATα ura3-52 his4-619 sec13-1 | Kaiser laboratory |

| CKY46 | MATa ura3-52 his4-619 sec13-1 | Kaiser laboratory |

| RSY315 | MATα sec13-4 | Schekman laboratory |

| RSY316 | MATa sec13-4 | Schekman laboratory |

| CKY50 | MATα ura3-52 his4-619 sec16-2 | Kaiser laboratory |

| CKY58 | MATα ura3-52 his4-619 sec18-1 | Kaiser laboratory |

| CKY59 | MATa ura3-52 his4-619 sec18-1 | Kaiser laboratory |

| RSY281 | MATα ura3-52 his4-619 sec23-1 | Schekman laboratory |

| RSY282 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 sec23-1 | Schekman laboratory |

| RSY1004 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 sec31-1 | Schekman laboratory |

| RSY529 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his4 sec62-1 | Schekman laboratory |

| Out-crossed sec− mutant and SEC+ control strains | ||

| MAS35-6A | MATa ura3-52 | This work |

| MAS35-6B | MATa ura3-52 sec13-1 | This work |

| MAS35-9C | MATa ura3-52 shr3Δ1∷URA3 | This work |

| MAS35-3A | MATa ura3-52 shr3Δ1∷URA3 sec13-1 | This work |

| MAS35-10B | MATa ura3-52 shr3Δ1∷URA3 sec13-1 | This work |

| MAS35-14B | MATa ura3-52 shr3Δ1∷URA3 sec13-1 | This work |

| MAS35-19D | MATa ura3-52 sec13-1 | This work |

| MAS35-1C | MATa ura3-52 shr3Δ1∷URA3 | This work |

| MAS203-1B | MATa ura3-52 lys2Δ201 | This work |

| MAS203-1A | MATα ura3-52 lys2Δ201 sec31-1 | This work |

| MAS203-6C | MATa ura3-52 lys2Δ201 shr3Δ1∷URA3 | This work |

| MAS203-12D | MATa ura3-52 lys2Δ201 shr3Δ1∷URA3 sec31-1 | This work |

| MAS203-20C | MATα ura3-52 lys2Δ201 shr3Δ1∷URA3 sec31-1 | This work |

| MAS203-1C | MATα ura3-52 lys2Δ201 ade2 shr3Δ1∷URA3 sec31-1 | This work |

| MAS202-3C | MATα ura3-52 lys2Δ201 sec31-1 | This work |

| MAS203-5B | MATa ura3-52 lys2Δ201 shr3Δ1∷URA3 | This work |

| MAS26-1A | MATa ura3-52 sec12-1 | This work |

| MAS242-7B | MATα ura3-52 sec13-4 | This work |

| MAS296-1A | MATα ura3-52 sec16-2 | This work |

| MAS21-1C | MATα ura3-52 sec18-1 | This work |

| MAS226-3C | MATα ura3-52 sec23-1 | This work |

| MAS297-2B | MATa ura3-52 sec62-1 | This work |

Table 2.

Plasmids

| Plasmids | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pPL247 | 3.5-kb SpeI–SalI fragment containing GAP1 in pRS316 | Ljungdahl et al., 1992 |

| pPL250 | 1.4-kb AccI fragment containing SHR3 in pRS202 | This work |

| pPL257 | GAP1∷FLU1 in pRS316 | Ljungdahl et al., 1992 |

| pPL288 | shr3Δ5∷hisG-URA3-neo-hisG in pBSII KS(+) | Kuehn et al., 1996 |

| pPL202 | 1.4-kb AccI fragment containing SHR3 in pBSII KS(+) | Ljungdahl et al., 1992 |

| pFG6 | 1.8-kb SalI–XmnI fragment containing SUC2 in pBSII KS(+) | This work |

| pFG8 | 1.8-kb SphI–PstI fragment containing SUC2 in pGEM-5Zf(+) | This work |

| pFG10 | 1.8-kb SphI–SalI fragment containing SUC2 in pRS316(ΔXN) | This work |

| pFG11 | pFG10 with NotI restriction site introduced into SUC2 | This work |

| pFG12 | SUC2-HA3 in pRS316(ΔNX) | This work |

| pFG19-pFG25 | 15-bp SphI–XbaI linker insertions in GAP1 in pPL247 | This work |

| pFG32-pFG38 | GAP1-SUC2 fusion constructs in pFG12 | This work |

| pFG40 | 6.4-kb SphI–SalI fragment containing suc2Δ100∷hisG-URA3-neo-hisG in pFG10 | This work |

| pFG80-pFG84 | gap1 mutant alleles with in-frame insertions encoding IEGRIEGR in pPL247 | This work |

| pFG117 | GST-SHR3 in pEGKT | This work |

| pFG118 | GST-CT-shr3(160–210) in pEGKT | This work |

| pFG119 | GST-shr3-23 in pEGKT | This work |

| pFG120 | GST-shr3ΔCT(163–201) in pEGKT | This work |

| pMB42 | 1.4-kb AccI fragment containing shr3-23 in pRS202 | This work |

Temperature-sensitive secretory mutants were kindly provided by R. Schekman (University of California, Berkeley, CA) or C.A. Kaiser (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA) as indicated. Diploid strains, constructed by crossing sec− strains to SEC+ strains PLY144 and PLY147, were sporulated, and tetrad analysis was used to verify that the temperature sensitive phenotypes segregated 2:2. The resulting temperature-sensitive spore-derived sec− strains were examined to determine permissive, semipermissive, and restrictive growth temperatures. If phenotypic variation was observed, additional backcrosses were carried out to eliminate interfering mutations. The desired sec− strains were obtained by either of two approaches. In most cases sec− strains were crossed with shr3Δ1::URA3 strains PLY151 and PLY155 to obtain meiotic segregants with the four possible combinations SHR3 SEC+, SHR3 sec−, shr3Δ1 SEC+, and shr3Δ1 sec−. Alternatively, one chromosomal copy of SHR3 was replaced with URA3 in SEC+/sec− diploid strains by transformation with EcoRI–SalI-digested pPL219 (Ljungdahl et al., 1992). The transformations were carried out using overnight cultures grown at 22°C; the transformation plates were incubated at 20°C. The deletion of SHR3 was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. Tetrad analysis confirmed that URA3 segregated 2:2; each Ura+ spore-derived colony was resistant to 30 mM histidine (Ljungdahl et al., 1992). This latter method was used to obtain the desired combinations of strains with sec13-1, sec16-2, and sec62-1. In all cases, spore-derived colonies with identical, and the least auxotrophic markers, were chosen to obtain as uniform genetic backgrounds as possible.

Standard yeast media were prepared, and yeast genetic manipulations were performed as described in Guthrie and Fink (1991). SGal that we used is a synthetic minimal medium containing 3% galactose as sole carbon source. SUD and SPD, containing urea and proline as sole nitrogen source, respectively, were prepared as described (Ljungdahl et al., 1992). Where required, SPD was supplemented with l-histidine (0.6–30 mM). SPGal is similar to SPD, except that 2% galactose replaces dextrose as the carbon source. The concentration of yeast nitrogen base in SUD, SPD, and SPGal is fourfold higher than the amount used in other standard synthetic media. Wickerham minimal media, with and without added inositol and supplemented to enable the growth of auxotrophic strains, were used to check inositol growth phenotypes (Wickerham, 1946). Yeast transformations were performed as described by Ito et al. (1983) using 50 μg of heat-denatured calf thymus DNA. Transformants were selected on solid SC media lacking appropriate auxotrophic supplements, except when sec13-1 strains were used, in which case transformants were selected on SD media supplemented as required.

Genetic Analysis

Genetic interactions between a shr3 null allele and specific sec− temperature-sensitive mutant alleles were examined as follows. SHR3+ SEC+, SHR3+ sec−, shr3Δ1::URA3 SEC+, and shr3Δ1::URA3 sec− strains were streaked out for single colonies on SD media (supplemented as required) and incubated at 20°C. Single colonies were suspended in liquid SD to an OD600 of 1, and a series of 10-fold dilutions were made in sterile SD. From each dilution 2-μl aliquots were pipetted onto YPAD, SC, SD, (supplemented as required), and SPD (supplemented as required) containing 0, 0.6, 2.0, 10, and 30 mM histidine. The temperature range for each sec− allele was empirically determined. All plates were incubated at selected temperatures representing permissive, semipermissive, and nonpermissive (restrictive) temperatures. Plates were incubated for 9 d, and growth characteristics were followed on plates incubated at each temperature starting from day 2.

Plasmid Constructions

Plasmids were constructed using standard molecular biological procedures. pPL250 was constructed by subcloning the 1.45-kb EcoRI–SalI fragment isolated from pPL210 (Ljungdahl et al., 1992) containing SHR3 into EcoRI–SalI digested pRS202 (Connelly and Hieter, 1996). pRS316 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989) was digested with NotI and XbaI, made blunt by treatment with Klenow fragment and religated to create pRS316ΔNX. GAP1-SUC2 hybrid plasmids (Figure 1) were constructed in three stages. In the first stage an epitope-tagged SUC2 reporter construct was created. pFG6 was constructed by inserting a 1.8-kb SalI–XmnI SUC2 fragment from pSEY304 (Bankaitis et al., 1986) into SalI–EcoRV-digested pBluescript II KS(+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Plasmid pFG6 was restricted with SphI–PstI, and the released 1.8-kb SUC2 fragment was cloned into SphI–PstI-restricted pGEM-5Zf(+) (Promega, Madison, WI) to create plasmid pFG8. Plasmid pFG10 was constructed by inserting the SphI–SalI fragment from pFG8 into SphI–SalI-digested pRS316ΔNX. A 42-nucleotide (nt) synthetic oligomer containing a NotI cleavage site flanked on each side by 17 bases complementary to the SUC2 sequence was annealed to single-stranded pFG10 DNA prepared with helper phage M13K07 (Vieira and Messing, 1987) in the dut− ung− Escherichia coli host RZ1032 (Kunkel et al., 1987). After elongation, ligation, and transformation into a dut+ ung+ host, plasmids were screened for the presence of a NotI restriction site diagnostic for successful mutagenesis. This procedure created plasmid pFG11. A thrice-reiterated epitope from the influenza virus hemagglutinin protein HA1 (HA3; Wilson et al., 1984), contained on a 111-bp NotI fragment encoding 37 amino acids (obtained from M. Tyers, Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), was introduced into the SUC2 sequence to create plasmid pFG12. In this construct the HA3 epitope is placed in-frame following amino acid 487 of mature invertase. In stage 2, SphI–XbaI linkers were inserted into GAP1 by site-directed insertion mutagenesis using single-stranded pPL247 as template DNA. The linker was inserted at seven positions along the GAP1 gene corresponding to sequences encoding the following amino acids: 354, 420, 445, 490, 526, 567, and 601 (plasmids pFG19 through pFG25, respectively). This was accomplished using synthetic oligomers comprising 41–43 nt containing SphI–XbaI cleavage sites flanked by 13–14 nt of complementary GAP1 sequence. In stage 3, plasmids pFG32–pFG38 were constructed by digesting plasmids pFG19-pFG25 with SpeI–SphI, the released GAP1 fragments were ligated into SpeI–SphI-digested pFG12. These GAP1-SUC2 hybrid plasmids encode in-frame fusion proteins, each containing the following junction: Gap1p sequence-CMQAF-T (aa 3 of mature invertase). pFG40 was constructed by inserting a blunt-end 5-kb BglII–BamHI hisG-URA3-neo-hisG cassette isolated from pSE1076 (Allen and Elledge, 1994) into HpaI–XbaI-digested pFG10, made blunt by treatment with Klenow fragment. The mutant alleles of gap1 contained within plasmids pFG80-pFG84 (Figure 2B) were also constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using single-stranded pPL247 as template DNA. These plasmids contain a maximum of eight extra amino acids, which generate the tetrameric repeat IEGRIEGR, inserted into Gap1p following amino acids 119, 159, 171, 411, and 417, respectively. Successful mutagenesis was ascertained by restriction with TaqI.

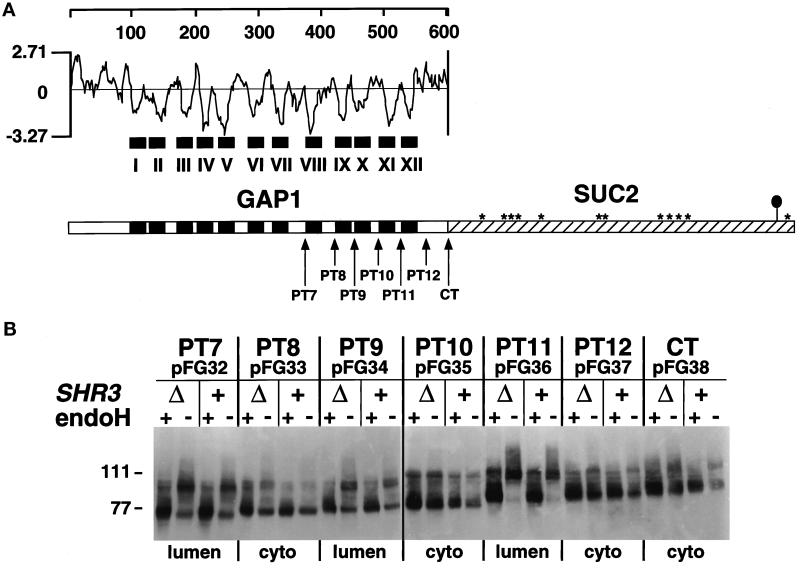

Figure 1.

Membrane topology of Gap1p in SHR3 and shr3Δ6 strains. (A) Hydrophilicity plot of Gap1p calculated according to the method of Kyte and Doolittle (1982) (window size of 11). The black boxes depict the 12 hydrophobic putative membrane-spanning domains (I–XII) present in Gap1p. In the schematic representation of the CT Gap1–Suc2p fusion protein, the white box represents Gap1p, and the hatched box represents the Suc2p reporter construct. Asterisks indicate potential glycosylation sites present within Suc2p. The black oval symbol in the C-terminal portion of Suc2p indicates the location of the HA3 epitope-tag. The arrows depict the locations of the junctions of the six (PT7–PT12) Gap1–Suc2p fusion proteins. (B) GAP1-SUC2 gene fusions (pFG32–pFG38) expressed in FGY84 (SHR3) and FGY85 (shr3Δ6). Transformants were grown in SUD (plus lysine and adenine), and extracts of total cell protein were prepared. Protein preparations were solubilized in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, treated with endoH where indicated, and resolved by SDS-PAGE in 7.5% polyacrylamide gels, immunoblotted, and analyzed as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. The topological orientation of each Suc2p reporter and the positions of the molecular mass markers in kilodaltons are indicated.

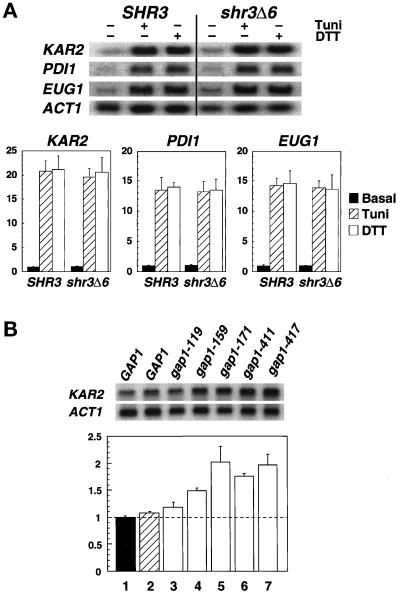

Figure 2.

Transcription levels of ER stress response proteins in SHR3 and shr3Δ6 strains. (A) Total RNA preparations (5 μg) isolated from cultures of FGY58 (SHR3) and FGY60 (shr3Δ6) transformed with pPL257 (GAP1) were separated by gel electrophoresis, transferred to nylon filters, and hybridized with radiolabeled DNA probes specific for KAR2, PDI1, EUG1, and ACT1. Cultures were grown at 30°C for 2.5 h in SUD in the absence or presence of 4 μg/ml tunicamycin (Tuni) or 3 mM DTT. Phosphorimager quantitations from two independent experiments are presented as ratios of basal transcription levels with respect to the SHR3 strain (FGY58) normalized to 1; error bars represent 1 standard deviation. (B) The stress response pathway is induced in strains expressing mutant alleles of gap1. Cultures of strains FGY58 (SHR3) transformed with plasmid pPL257 (GAP1, black bar, lane 1) and FGY60 (shr3Δ6) transformed with plasmids pPL257 (GAP1, hatched bar, lane 2), pFG80 (gap1–119), pFG81 (gap1–159), pFG82 (gap1–171), pFG83 (gap1–411), and pFG84 (gap1–417) (white bars, lanes 3–7, respectively) were grown at 30°C for 4 h in SPD (plus adenine and lysine). RNA was isolated and analyzed using radiolabeled DNA probes specific for KAR2 and ACT1. Phosphorimager quantitations from three independent experiments are presented as ratios of the transcription levels with respect to the SHR3 strain (FGY58, lane 1) normalized to 1; error bars represent 1 standard deviation.

Plasmids enabling the expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins (see Figure 6) were constructed as follows. Plasmids pFG113 and pFG114 were constructed by single-stranded mutagenesis using pPL202 as template; BamHI sites were inserted immediately following the ATG start codon (at nt + 4) and following nt +477 of SHR3, respectively. Plasmid pFG115 was created by introducing a point mutation (C→G) at nucleotide position 56 of SHR3 using single-stranded pFG113 as template; this modification recreates the shr3-23 mutant allele. Nucleotides 489–603 of SHR3 were deleted using single-stranded pFG113 as template resulting in pFG116. The desired BamHI–BamHI fragments from pFG113–116 were inserted into BamHI-cut pEGKT (Mitchell et al., 1993) creating pFG117–120. pMB42 was constructed by inserting the 1.4-kb SalI–NotI fragment of pFG115 into SalI–NotI-digested pRS202.

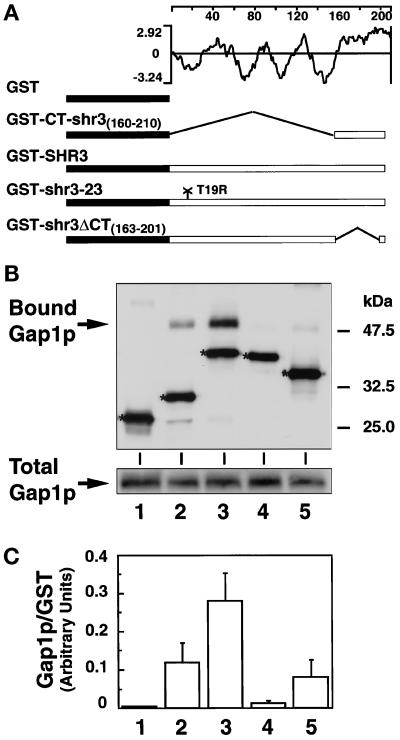

Figure 6.

Shr3p physically associates with Gap1p. (A) Schematic diagram of the pGAL1-promoted GST-containing proteins and hydrophilicity plot of Shr3p calculated according to the method of Kyte and Doolittle (1982) (window size of 11). (B) Immunoblot analysis of Gap1p-associated (Bound Gap1p) with GST fusion proteins expressed in FGY145, GST alone (lane 1), GST-CT-shr3(160–210) (lane 2), GST-SHR3 (lane 3), GST-shr3-23 (lane 4), and GST-shr3ΔCT(163–201) (lane 5). GST fusion proteins were purified by affinity chromatography to glutathione-conjugated Sepharose beads. The beads were washed four times using FGB buffer containing 0.1% DM, and SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added to a total of 20 μl of beads. Proteins were denatured at 37°C for 10 min and resolved by SDS-PAGE in a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Gap1p and GST proteins were visualized using antiserum from rabbits immunized with the amino-terminal portion of Gap1p fused to GST (Springael and André, 1998). Protein bands corresponding to each of the GST constructs are marked with an asterisk. The total amount of Gap1p present in protein extracts before GST protein purification is shown in the lower gel panel; the amount of total protein loaded into each lane corresponds to 1/25 of that incubated with glutathione beads. (C) Quantification of chemiluminescent signals (LAS1000; Fuji) from two independent experiments. Values represent the ratio of the amount of Gap1p copurifying (bound) per unit of GST protein; the error bars indicate 1 standard deviation.

Protein Manipulations

Total yeast protein was obtained by the method of Silve et al. (1991). Samples were heated for 10 min at 37°C, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE using a modified Laemmli (1970) system in which SDS is omitted from the gel and lower electrode buffer. The membrane association of Gap1–Suc2p hybrid proteins was determined essentially as described by Ljungdahl et al. (1992). Immunoblots were incubated for 1–2 h with anti-HA1 mouse monoclonal 12CA5, and ascites fluid was diluted 1:1500. Immunoreactive bands were visualized either by chemiluminescence detection or by autoradiography using 125I-protein A. For quantitation, blots probed with primary mouse antibodies were incubated 1–2 h with affinity-purified rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) diluted 1:500, washed, and then incubated with affinity-purified 125I-protein A (100 μCi/ml; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) diluted 1:2000. The amount of radioactivity was quantitated using a Fujix BAS1500 Bio-Image Analyzer (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan).

The Gap1p membrane topology was analyzed as follows. Plasmids pFG32 through pFG38 were transformed into strains FGY84 (SHR3) and FGY85 (shr3Δ6). Ura+ transformants were selected on SC (minus uracil) agar plates. Overnight cultures grown in liquid SC (minus uracil) were harvested, washed once in water, and resuspended to an OD600 of 0.5 in SUD (plus adenine and lysine). Cells were allowed to grow for 4 h at 30°C to an OD600 of 1.5. Total yeast protein was prepared. Duplicate protein samples (25 μl), derived from an equivalent of OD600 = 0.2 cell suspension, were diluted with an equal volume of 100 mM Na citrate, pH 5.5, and heated for 10 min at 37°C. Endoglycosidase H (endoH, 3 mU; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) was added to half of the samples, and all samples were incubated overnight at 4°C (Orlean et al., 1991). Before SDS-PAGE the samples were heated at 37°C for 10 min.

GST fusion proteins were expressed in strain FGY145 using the following induction scheme. Cell cultures of FGY145 transformed with plasmids pEGKT or pFG117–pFG120 were pregrown in SC (minus uracil) at 30°C overnight to an OD600 of 3. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed once in water, and resuspended at an OD600 of 0.5 in SGal (plus histidine). The cultures were grown overnight (10–12 h) at 30°C until they reached an OD600 of 1.5–2. Galactose-induced cells were harvested, washed once in water, and resuspended at an OD600 of 1 in SPGal (plus histidine), and cells were allowed to grow for an additional 4 h at 30°C. After proline induction, cells were harvested and washed once in FGB buffer (70 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM magnesium acetate, 0.25 M sorbitol, 0.5 mM DTT, and 20 mM HEPES, pH 6.8).

GST fusion proteins were isolated as follows. Cell pellets were resuspended in FGB buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 mM PMSF [Sigma, St. Louis, MO], 10 KIE/ml aprotinin [Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany] and complete protease inhibitor mixture [Boehringer Mannheim]) at an OD600 of 200. Cells were lysed by vigorous vortexing in the presence of glass beads, nine 20-s pulses were used, cell suspensions were incubated on ice for 60 s between pulses. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 4000 × g. An aliquot of 10% DM (Boehringer Mannheim) in FGB buffer was added to the cell extracts to reach a final concentration of 0.8% DM. The extracts were mixed by continuous inversion during a 10-min incubation period at room temperature. The solubilized cell extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant fractions were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham) for 15 min at room temperature. The glutathione-conjugated beads were pelleted by centrifugation for 2 min at 3000 × g and washed four times with either FGB buffer containing 0.1% DM or with low-potassium FGB buffer (15 mM potassium acetate) containing 0.02% DM, as indicated. Twenty microliters of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer were added to 20 μl of glutathione beads. Proteins were denatured either at 37°C for 10 min or 65°C for 5 min as indicated, resolved by SDS-PAGE in 10% polyacrylamide gels, and immunoblotted. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: α-Gal2p, 1:2000; α-Gap1p, 1:20000; α-Pma1p, 1:5000; α-Sar1p, 1:1000; α-Sec13p, 1:1000; α-Sec23p, 1:1000; α-Sec24p, 1:3000;α-Sec31p, 1:3000; and α-Sec61p, 1:5000. Immunoblots were washed, incubated with secondary anti-rabbit immunoglobulin HRP-linked antibody and developed using chemiluminescence detection reagents (ECL-Plus western blotting detection systems; Amersham). Chemiluminescent signals were quantitated using the LAS1000 system (Fuji).

Radiolabeling and Immunoprecipitation

Radiolabeling and immunoprecipitations were conducted essentially as described (Silve et al., 1991; Volland et al., 1994). Cells were grown and incubated at 30°C unless otherwise noted. The expression of GST-Shr3p (pFG117) in strain FGY145 was induced as previously described with the exception that cells were pregrown in minimal sulfate-free SD (plus histidine) media containing ammonium chloride. Galactose- and proline-induced cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in fresh SPGal (plus histidine) media at an OD600 of 3. Cells were incubated for 20 min, and 25 μCi of [35S]methionine/OD600 of cells (Amersham) were added. Cells were labeled for 5 min, and a chase was initiated by the addition of an aliquot of 100× chase solution (25 mM l-methionine and 25 mM l-cysteine). At the indicated times, aliquots of cells were withdrawn and incubated on ice for 5 min in the presence of 10 mM NaN3 and 10 mM KF. The chilled cell suspensions were centrifuged, and the cell pellets were washed once in FGB buffer containing 10 mM NaN3 and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Labeled cells were lysed with glass beads, and DM-solubilized protein preparations were isolated as previously described.

The solubilized protein preparations from each time point were split into two fractions. Fraction A, corresponding to 80% of the total protein preparation, was incubated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads, and GST-Shr3p complexes were purified as described. Proteins bound to glutathione-conjugated beads were dissociated by heating for 10 min at 45°C in 30 μl of 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer (2% SDS, 50 mM Tris-hydrochloride, pH 6.8, 2 mM EDTA, and 10% glycerol) without 2-mercaptoethanol and bromphenol blue. These samples containing GST-Shr3p-associated proteins were diluted with TNET buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) to a final volume of 0.6 ml. Fraction B, the remaining 20% of the total protein preparation, was similarly diluted with TNET buffer to a final volume of 0.6 ml. Anti-Gap1p antibodies were added (final dilution, 1:1800), and samples were incubated at room temperature during continuous mixing by inversion for 30 min. Forty microliters of a 12.5% (vol/vol) suspension of protein A-Sepharose CL-4B beads (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) were added to each sample, and incubations were continued for 1 additional hour. The immunoprecipitates were collected by centrifugation and washed three times with TNET buffer and once with TNET without Triton X-100 (TNE). Precipitated proteins were eluted by incubation for 10 min at 45°C in 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Eluted proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE in a 10% gel. Gels were fixed in glacial acetic acid:methanol:H2O (10:20:70), rinsed briefly in water, and dried. Radiolabeled proteins were detected and quantitated by phosophorimaging (Fujix BAS1500 Bio-Image Analyzer).

Northern Blots

Total RNA was prepared according to the method of Elder et al. (1983). Five micrograms of denatured RNA were separated by agarose electrophoresis using a formaldehyde buffer system essentially as described by Maniatis et al. (1982), and transferred to a GeneScreen Plus membrane (DuPont New England Nuclear, Boston, MA). Blots were prehybridized for 2 h in Church buffer (7% SDS, 1% BSA, 1 mM EDTA, and 250 mM NaPi, pH 7.2) (Church and Gilbert, 1984). Four radiolabeled probes were used; a 1.1-kb KpnI–XbaI KAR2 fragment from pMR109 (Rose et al., 1989), a 1.1-kb HpaI–SalI PDI1 fragment from pCT37 (Tachibana and Stevens, 1992), a 2.8-kb HindIII–SalI EUG1 fragment from pCT20 (Tachibana and Stevens, 1992), and a 1.6-kb BamHI–HindIII ACT1 fragment (Ng and Abelson, 1980). DNA fragments were purified from low-melting-temperature TAE agarose gels and were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) using the random-primed DNA labeling kit (MBI Fermentas, Amherst, NY). Hybridizations were carried out in Church buffer at 55°C overnight. Blots were washed three times for 20 min each with 5× SSC and 0.1% SDS and three times for 20 min each with 1× SSC and 0.1% SDS. The amount of radioactivity was quantitated using a Fujix BAS1500 phosphorimager. After background correction, signal strengths were normalized using the levels of actin mRNA present in RNA preparations.

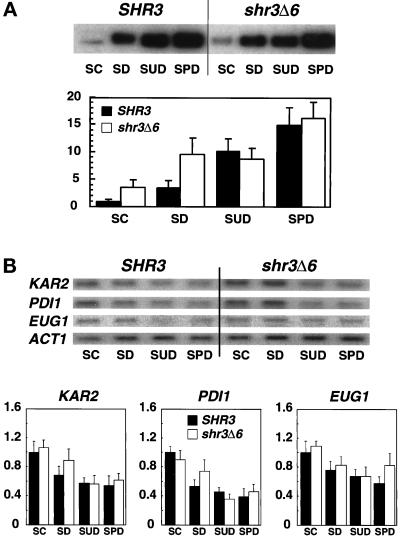

The transcript levels of stress response proteins (Figures 2 and 3) were measured in strains FGY58 (SHR3) and FGY60 (shr3Δ6) transformed with plasmids as indicated. Transformants were grown overnight in liquid SC (minus uracil) to an OD600 of 2, washed once in water, and diluted in desired synthetic media (plus adenine and lysine) to an OD600 of 0.5. The stress response (Figure 2A) was assayed as follows: cells were resuspended in SUD media and allowed to grow for 90 min at 30°C, at which point the culture was split into three tubes, each containing 10 ml. Two of the tubes received an aliquot of either tunicamycin (Sigma) or DTT (Boehringer Mannheim) to a final concentration of 4 μg/ml and 3 mM, respectively. Cells were allowed to grow an additional 2.5 h, harvested (OD600 ∼1.5), and washed once with H2O, and total RNA was isolated. The level of stress induction resulting from the expression of mutant forms of gap1p (Figure 2B) was measured as follows: cells transformed with pPL257 (Gap1p) or plasmids pFG80–pFG84 (mutant forms of gap1p) were diluted in SPD (plus adenine and lysine) to an OD600 of 0.5 and grown at 30°C for 4 h; cells were harvested and washed once with H2O, and total RNA was isolated. The basal levels of stress protein transcription (Figure 3) was determined by isolating total RNA from cells grown at 30°C for 4 h in SC (minus uracil), SD, SUD, and SPD.

Figure 3.

Gap1p and KAR2, PDI1 and EUG1 transcript levels in strains grown on alternative nitrogen sources. Overnight cultures of FGY58 (SHR3) and FGY60 (shr3Δ6) transformed with pPL257 (GAP1-FLU1), pregrown at 30°C under GAP1-repressing conditions in SC (minus uracil), were harvested, washed once with H2O, and used to inoculate SC (minus uracil), SD (plus adenine and lysine), SUD (plus adenine and lysine), and SPD (plus adenine and lysine) media at a starting OD600 of 0.5. The cultures were incubated for 4 h at 30°C, and extracts of total cell protein and RNA were prepared. (A) Proteins from an equivalent of 0.2 OD600 units were analyzed by immunoblotting as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Gap1p expression levels were quantitated by phosphorimaging. Values from two independent experiments have been corrected for background and normalized to the Gap1p expression level in the FGY58 strain grown in SC (minus uracil); error bars indicate 1 standard deviation. (B) Five-microgram RNA aliquots were separated by gel electrophoresis and analyzed by Northern analysis as described in Figure 2. Phosphorimager quantitations from two independent experiments are presented; transcript levels are normalized to the expression found in the SHR3 strain (FGY58) grown in SC (minus uracil), the medium with the highest basal transcription levels; error bars indicate 1 standard deviation.

RESULTS

Gap1p Integrates into the ER Membrane Independently of Shr3p

The Gap1p sequence contains 12 hydrophobic regions that potentially function as membrane-spanning domains (see hydrophilicity plot; Figure 1A). Using single-stranded mutagenesis, seven SphI–XbaI linkers were individually introduced into GAP1 sequences encoding the carboxyl-terminal portions of the permease (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). These linkers enabled the construction of in-frame gene fusions with invertase (SUC2). Gene fusions, often with SUC2, have been used in yeast to study the topology of a variety of ER and PM proteins (Hoffmann, 1987; Green et al., 1989; Senstag et al., 1990; Wilkinson et al., 1996). Suc2p functions as a topological reporter because it does not exhibit a distinct topogenic preference and becomes glycosylated at multiple sites when translocated across the ER membrane. We focused our analysis on the C terminus of Gap1p because it has been shown that the N-terminal transmembrane portions of two polytopic proteins, the human Mdr3p glycoprotein and the yeast Sec61p, require the presence of downstream C-terminal membrane domains to attain their correct membrane orientation (Wilkinson et al., 1996; Zhang, 1996).

The seven Gap1–Suc2p fusion proteins (Figure 1A) contain Suc2p at positions following hydrophobic segments VII–XII (PT7–PT12) and at the extreme C terminus of Gap1p (CT). The fusion junctions were chosen to place Suc2p within hydrophilic regions as far away from the preceding hydrophobic domain as possible. Strains FGY84 (SHR3) and FGY85 (shr3Δ6) were transformed with plasmids pFG32–pFG38. Total cell protein isolated from each of the resulting 14 strains was fractionated by SDS-PAGE before and after treatment with endoH (Figure 1B). The Gap1–Suc2p fusions migrated as bands with the predicted mass, and extracts from these strains contained equivalent amounts of fusion proteins. These results are consistent with our previous findings that equivalent amounts of Gap1p are localized to membranes even in the absence of SHR3 (Ljungdahl et al., 1992). Cell extracts from strains transformed with pFG33 (PT8) and pFG38 (CT) were treated with a variety of reagents to assess the nature of the association between the fusion proteins and membrane fractions. These two Gap1–Suc2p fusion constructs, produced in SHR3 and shr3Δ6 strains, fractionated as integral membrane proteins and were not extracted by either 0.1 M sodium carbonate, pH 11, 1.6 M urea, or 0.6 M NaCl.

Each of the seven Gap1–Suc2p proteins exhibited an identical pattern of endoH sensitivity and migrated the same regardless of the SHR3 genotype of the strain in which it was produced (Figure 1B). The GAP1-SUC2 constructs PT7, PT9, and particularly PT11 produced proteins that were endoH sensitive. PT8, PT10, PT12, and the extreme carboxyl terminal fusion CT remained unglycosylated. The finding that both PT12 and CT-terminal fusion proteins were not glycosylated indicates that the C terminus of Gap1p is oriented in the cytoplasm, and that Gap1p is itself not glycosylated. Differences between the glycosylation state of the constructs expressed in wild-type and shr3 null mutant strains would have provided an indication that Shr3p is required during the translocation of aaps into the ER membrane. Because no differences were observed, our data suggest that Shr3p is not required for the translocation of the membrane spanning domains of Gap1p into the membrane of the ER.

Aaps Fold Correctly Independently of Shr3p Function

If Shr3p is required to enable aaps to fold properly, then the aaps that accumulate in the ER membrane of shr3Δ cells should be incorrectly folded. The presence of misfolded proteins in the ER has been shown to be actively monitored and leads to the induced expression of several stress response proteins. We indirectly monitored the in vivo folding state of aaps in SHR3 and shr3 null mutant cells by analyzing the levels of mRNA transcripts of three stress response proteins KAR2, PDI1 and EUG1. The pattern of expression of these stress response proteins is similar (Cox et al., 1993; Mori et al., 1992, 1993; Tachibana and Stevens, 1992); however, unlike PDI1 and EUG1, KAR2 expression is also induced under conditions that block the translocation of proteins into the ER membrane (Arnold and Wittrup, 1994).

We examined whether the unfolded protein stress response pathway functions normally in shr3 null mutant strains. The expression levels of KAR2, PDI1, and EUG1 were analyzed in wild-type and shr3Δ6 strains grown in SUD in the absence or presence of 4 μg/ml tunicamycin or 3 mM DTT. As shown in Figure 2A, shr3Δ6 cells respond to these stress-inducing agents in an identical manner as do SHR3 cells. We addressed whether the stress response pathway is induced by mutant, presumably misfolded, forms of Gap1p in the ER membrane. Five gap1 mutant alleles (pFG80–84), each encoding full-length gap1p proteins containing twice-repeated tetrameric sequence (IEGRIEGR) within hydrophilic regions, and GAP1 (pPL257) were transformed into strains FGY58 (SHR3) and FGY60 (shr3Δ6). Transformants produced similar amounts of immunologically detectable Gap1p or gap1p protein. The mutant gap1p proteins were inactive because the FGY58 transformants carrying plasmids pFG80–84 were unable to grow on media with citrulline as the sole nitrogen source. The mutant proteins gap1–159p, gap1–171p, and gap1–411p exhibited a tendency to form aggregates that migrated as high molecular weight bands upon SDS-PAGE. Under similar conditions, native Gap1p expressed in either SHR3 or shr3Δ6 cells did not form aggregates. Compared with Gap1p (Figure 2B, lanes 1 and 2), all five mutant gap1p proteins induced the expression of KAR2 (Figure 2B, lanes 3–7). These results indicate that the unfolded protein stress response pathway is responsive to the presence of misfolded gap1p proteins and is not affected by shr3 mutations.

We examined KAR2, PDI1, and EUG1 expression in cells grown on alternative nitrogen sources with various amounts Gap1p (Figure 3). When grown in SC or SD media shr3Δ6 cells have threefold more Gap1p than SHR3 cells (Figure 3A), but shr3Δ6 mutants do not express significantly higher levels of ER unfolded stress response proteins (Figure 3B). Similarly, stress protein expression was not elevated in cells grown on SPD (Figure 3B) when Gap1p and many additional aaps are present in high amounts (Figure 3A). In fact stress protein expression was lower in both SHR3 and shr3Δ6 cells grown in non–ammonia-based media (SUD and SPD) (Figure 3B). Our observation that stress proteins are expressed at similar levels in both SHR3 and shr3Δ6 cells provides evidence that Shr3p function is not primarily associated with the folding of aaps.

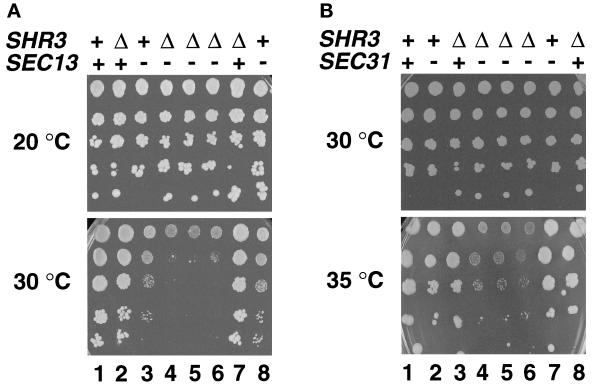

shr3Δ1 Interacts Genetically with sec13-1 and sec31-1

We took advantage of the phenomenon of synthetic genetic interactions to examine SHR3 function. Temperature-sensitive secretory (sec−) mutants known to affect ER to Golgi transport provided the starting point of our investigations. The sec− mutant alleles examined and their wild-type functions are listed in Table 3. We anticipated that potential genetic interactions between shr3Δ1::URA3 and sec− mutants would lead to increased temperature sensitivity and/or altered histidine resistance of shr3Δ1 sec− double mutants compared with SHR3 sec− or shr3Δ1 sec+ single mutant strains. Of the sec− alleles examined, only two gave rise to clear synthetic phenotypes when combined with shr3Δ1 (Table 3). Reduced growth was observed at 30°C when shr3Δ1::URA3 was present in combination with sec13-1 (Figure 4A, dilution series 4–6). Under these conditions the single mutant strains (Figure 4A, dilution series 2, 3, 7, and 8) grew distinctly better. At 20°C all strains exhibited similar growth rates. Interactions were not observed in sec13-4 strains. It is known that sec13-4 is a weak mutant allele that displays very subtle secretory defects (Pryer et al., 1993). Synthetic interactions were also observed between shr3Δ1::URA3 and sec31-1. At 35°C shr3Δ1::URA3 sec31-1 double-mutant strains (Figure 4B, dilution series 4–6) grew extremely poorly in comparison with the single-mutant strains (Figure 4B, dilution series 2, 3, 7, and 8). The synthetic interactions observed between shr3Δ1 and both sec13-1 and sec31-1 were evident on all media examined and were independent of whether ammonia or proline was used as the nitrogen source.

Table 3.

Genetic interactions and effect of multicopy SHR3 and shr3-23

| sec− allele | Wild-type function | Genetic interaction,

Nitrogen source

|

Effect

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonium | Proline | 2 μm SHR3 | 2 μm shr3-23 | ||

| sec62-1 | Protein translocation | − | −/+ | Weak | Weak |

| enhancement | enhancement | ||||

| sec12-1 | ER vesicle formation | − | − | Suppression | Suppression |

| sec13-1 | ER vesicle formation | + | + | Suppression | None |

| sec13-4 | ER vesicle formation | − | − | Suppression | None |

| sec16-2 | ER vesicle formation | − | − | None | None |

| sec23-1 | ER vesicle formation | − | − | None | None |

| sec31-1 | ER vesicle formation | + | + | Suppression | None |

| sec18-1 | ER vesicle fusion | − | − | None | None |

Figure 4.

shr3Δ1 interacts genetically with sec13-1 and sec31-1. (A) Serial dilutions of strains with the indicated SHR3 and SEC13 genotypes were grown on SD (plus uracil) incubated at 20°C for 8 d (permissive temperature, upper panel) and on SC incubated at 30°C for 4 d (semipermissive temperature, lower panel). Dilution series 1–8 correspond to strains MAS35-6A (SHR3 SEC13), MAS35-9C (shr3Δ1 SEC13), MAS35-6B (SHR3 sec13-1), MAS35-3A (shr3Δ1 sec13-1), MAS35-10B (shr3Δ1 sec13-1), MAS35-14B (shr3Δ1 sec13-1), MAS35-1C (shr3Δ1 SEC13), and MAS35-19D (SHR3 sec13-1), respectively. (B) Serial dilutions of strains with the indicated SHR3 and SEC31 genotypes were grown on SPD (plus uracil, adenine, and lysine) incubated at 30°C for 5 d (permissive temperature, upper panel) and on SPD (plus uracil, adenine, and lysine) containing 0.6 mM histidine incubated at 35°C for 5 d (semipermissive temperature, lower panel). Dilution series 1–8 correspond to strains MAS203-1B (SHR3 SEC31), MAS203-1A (SHR3 sec31-1), MAS203-6C (shr3Δ1 SEC31), MAS203-12D (shr3Δ1 sec31-1), MAS203-20C (shr3Δ1 sec31-1), MAS203-1C (shr3Δ1 sec31-1), MAS202-3C (SHR3 sec31-1), and MAS203-5B (shr3Δ1 SEC31), respectively.

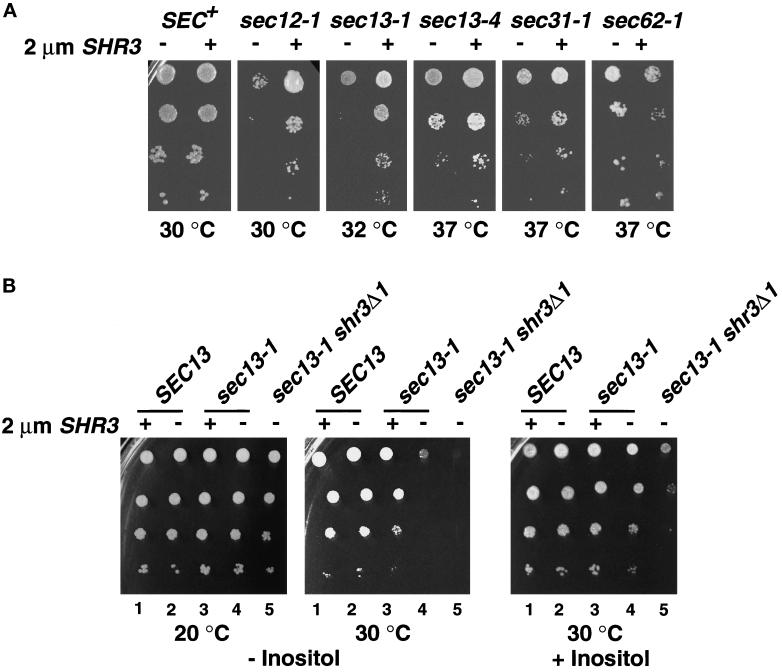

Overexpression of SHR3 Facilitates COPII Vesicle Formation

We sought independent confirmation that Shr3p function is linked to COPII vesicle formation and examined the effects of the overexpression of SHR3 in sec− mutant strains. The panel of sec− mutant strains and our wild-type tester strains PLY144 and PLY147 (Table 3) were transformed with the high-copy 2μ plasmid pRS202 (vector control) and with pPL250 (pRS202 containing SHR3). Ura+ transformants were selected and streaked for single colonies on SD (supplemented as required) plates incubated at 20°C. Cells derived from single colonies were suspended in SD, and dilution series were analyzed on a variety of media and temperatures in a similar manner as the synthetic genetic interaction experiments described in the preceding section. Culture plates were followed for 9 d to ascertain whether the overexpression of SHR3 affected the growth of sec− strains.

The overexpression of SHR3 had no effect on the growth of SEC+ strains but clearly suppressed the temperature-sensitive growth of sec12-1 and sec13-1 mutants, enabling these strains to grow at increased temperatures (Figure 5A). The temperature sensitivity of sec13-4 and sec31-1 strains was also suppressed to a lesser extent (Figure 5A). The overexpression of SHR3 did not affect the growth characteristics of sec16-2, sec23-1, and sec18-1 strains (Table 3). In sec62-1 strains the overexpression of SHR3 appeared to weakly inhibit growth (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Multicopy expression of SHR3 partially suppresses the temperature-sensitive phenotypes of sec12-1, sec13-1, sec13-4, and sec31-1 mutations. (A) Serial dilutions of strains transformed with pRS202 (−) and pPL250 (+) were incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 d and photographed. Strains from left to right are PLY144 (SEC+), MAS26-1A (sec12-1), MAS35-6B (sec13-1), MAS242-7B (sec13-4), MAS203-1A (sec31-1), and MAS297-2B (sec62-1). Strains were grown on SC (minus uracil), with the exception of MAS242-7B (sec13-4), which was grown on SPD medium containing 0.6 mM histidine. (B) Multicopy expression of SHR3 suppresses the inositol requirement of sec13-1 mutations. Serial dilutions of strains transformed with pRS202 (−) and pPL250 (+) were spotted onto media without (left and center panels) and with (right panel) inositol. Culture plates were incubated at the indicated temperature for 3 d and photographed. Dilution series 1 and 2, strain MAS35-6A (SHR3 SEC13); series 3 and 4, strain MAS35-6B (SHR3 sec13-1); series 5, MAS35-3A (shr3Δ1 sec13-1).

We noticed that sec13-1 strains display a temperature-sensitive dependency for exogenous inositol (Figure 5B, compare −Inositol plates incubated at 20 and 30°C, dilution series 4). With respect to SHR3, the inositol-dependent growth characteristics of sec13-1 strains exhibited a clear gene dosage effect. At 30°C sec13-1 shr3Δ1 double mutants are unable to grow on media lacking inositol (Figure 5B, −Inositol, dilution series 5). The presence of a single chromosomal copy of SHR3 enabled poor but noticeable growth of sec13-1 single mutant strains (Figure 5B, −Inositol at 30°C, compare dilution series 4 and 5). The overexpression of SHR3 substantially improved the growth of sec13-1 strains and enabled cells to grow in inositol-free media at rates approaching that of SEC13 wild-type strains (Figure 5B, −Inositol at 30°C, compare dilution series 2–4). The other sec− strains that we examined did not exhibit inositol-dependent growth phenotypes.

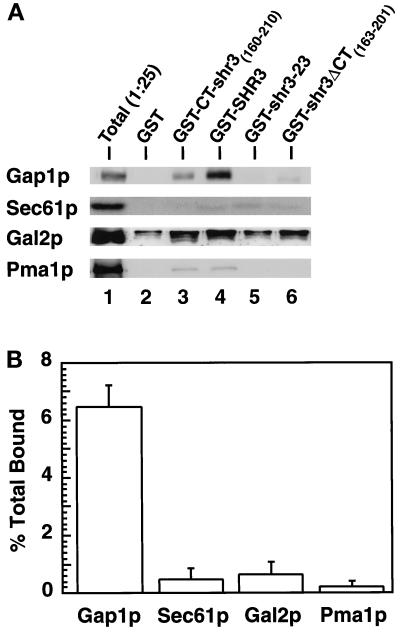

Gap1p Specifically Associates with Shr3p

To directly address the role of Shr3p in the packaging of aaps, we asked whether Gap1p could bind to four different GST-Shr3p fusion proteins. The GST fusion proteins that we examined (see Figure 6A) were full-length Shr3p (GST-SHR3), the hydrophilic carboxyl-terminal 50 amino acids of Shr3p (GST-CT-shr3(160–210)), Shr3p lacking amino acid residues 163–201 (GST-shr3ΔCT(163–201)) (this internal deletion eliminates the majority of the hydrophilic C-terminal domain of Shr3p but maintains the potential ER retention signal at the extreme C terminus), and shr3-23p mutant (GST-shr3-23), a nonfunctional mutant protein in which an arginine residue replaces threonine 19 (T19R) in the first transmembrane segment of Shr3p (Ljungdahl et al., 1992). The full-length GST-SHR3 is functional and complements all shr3 null mutant phenotypes. The internal C-terminal deletion construct, GST-shr3ΔCT(163–201), poorly complements shr3 mutations but only when overexpressed. The remaining two constructs are nonfunctional.

These fusion constructs, along with GST alone, were expressed in strain FGY145. In all instances similar levels of GST-containing proteins were obtained. The GST proteins were purified from DM-solubilized membrane preparations, and Gap1p association was determined by immunoblot analysis (Figure 6B). Whereas no Gap1p was found associated with GST alone (lane 1) or with the mutant GST-shr3-23 (lane 4), significant amounts of Gap1p copurified with GST-CT-shr3 (lane 2), GST-SHR3 (lane 3), and GST-shr3ΔCT (lane 5). These results indicate that the association between Gap1p and Shr3p is partially dependent on the presence of the carboxyl-terminal domain of Shr3p (lane 2). However, the observations that the overexpression of GST-shr3ΔCT construct complements shr3 mutations, and that Gap1p associates with this fusion protein, which lacks the majority of the C-terminal domain, indicate that Gap1p associates with Shr3p via additional interactions with internal regions of Shr3p (lane 5).

To ascertain whether the observed association between Gap1p and Shr3p was dependent on specific interactions, we examined whether other polytopic membrane proteins copurified with the GST constructs. The galactose permease (Gal2p) and the PM ATPase (Pma1p) are similar in size to aaps and contain similar numbers of membrane-spanning domains. These PM proteins are known to exit the ER independently of Shr3p (Ljungdahl et al., 1992). We also examined whether the resident polytopic ER membrane protein Sec61p could associate with the GST constructs. Immunoblots, identical to those in Figure 6B, were probed with rabbit anti-Sec61p, anti-Gal2p, and anti-Pma1p antibodies (Figure 7). The chemiluminescent signals derived from proteins present in the total extract (Figure 7, lane 1) and from proteins copurifying with GST-SHR3 (Figure 7, lane 4) were quantitated, and the percentages of proteins copurifying with GST-SHR3 (% total bound) were calculated (Figure 7B). The results indicate that a significant amount of the total Gap1p (6.5%) was associated with GST-SHR3, whereas only 0.5, 0.7, and 0.2% of the total of Sec61p, Gal2p, and Pma1p, respectively, copurified together with GST-SHR3. These results demonstrate that the copurification of Gap1p with Shr3p occurs through specific interactions.

Figure 7.

Shr3p specifically associates with Gap1p. (A) Immunoblot analysis of Gap1p, Sec61p, Gal2p, and Pma1p associated with purified GST fusion proteins. GST proteins were expressed in FGY145, purified, and analyzed as described in Figure 6. Protein bands corresponding to Sec61p, Gal2p, and Pma1p were visualized using rabbit antiserum as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. For purposes of comparison, the appropriate portion of the Gap1p immunoblot depicted in Figure 6 is included. Lane 1 (Total) contains an aliquot of extract, corresponding to 1/25 of that incubated with glutathione beads, prepared from strain FGY145 expressing the GST-SHR3 construct. (B) The chemiluminescent signals derived from proteins present in the total extract (lane 1) and from proteins copurifying with GST-SHR3 construct (lane 4) were quantitated (LAS1000; Fuji). The percentages of proteins bound to GST-SHR3 were calculated (Gap1p, Sec61p, Gal2p, or Pma1p bound to GST-SHR3 [lane 4]/total Gap1p, Sec61p, Gal2p, or Pma1p present in the extract [lane 1, multiplied by 25 to correct for loading] × 100). Values from two independent experiments are plotted; error bars indicate 1 standard deviation.

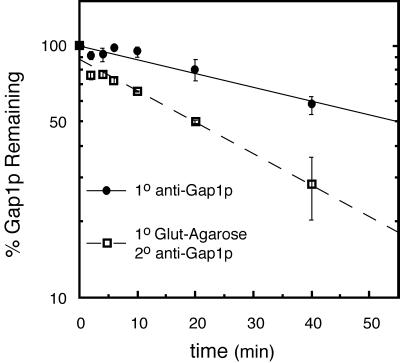

Shr3p–Gap1p Complex Is the Result of Transient Interactions within the ER

To address the nature of the Shr3p–Gap1p interaction, we used a pulse–chase analysis to examine the stability of complex formation (Figure 8). Galactose- and proline-induced cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for 5 min and chased with the addition of excess unlabeled methionine and cysteine. Samples were withdrawn at various times during a 40-min chase period. Cells were lysed, and cellular membranes were solubilized in the presence of 0.8% DM. Solubilized protein preparations from each time point were split into two fractions. In one fraction Gap1p was directly immunoprecipitated using anti-Gap1p antibodies (1o anti-Gap1p). The second fraction was subjected to two rounds of immunoprecipitations. In the first round glutathione-Sepharose beads were used to immunoprecipitate GST-SHR3. These immunoprecipitates were resolubilized, and the amount of Gap1p physically associated with GST-SHR3 was analyzed in a second round of immunoprecipitation (1o Glut-Agarose and 2o anti-Gap1p).

Figure 8.

Shr3p interacts transiently with Gap1p. The expression of GST-SHR3 (pFG117) and Gap1p in strain FGY145 was induced as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Cultures were labeled with [35S]methionine for 5 min and chased by the addition of excess unlabeled methionine and cysteine. Gap1p was immunoprecipitated from labeled extracts using anti-Gap1p antibodies directly (1o anti-Gap1p) or in a second round of immunoprecipitation from resolubilized immunoprecipitates obtained using glutathione-Sepharose beads (1o anti-GST and 2o anti-Gap1p).

Gap1p exhibited a half-life of 55 min (Figure 8, 1o anti-Gap1p), a similar half-life for Gap1p has previously been reported (Roberg et al., 1997). In isogenic strains lacking Shr3p the half-life of Gap1p increases approximately twofold, indicating that the degradation of Gap1p depends on its transport away from the ER. In this and other experiments with longer labeling and chase periods, we found that GST-SHR3 is a stable protein with a half-life of >300 min. The amount of Gap1p interacting with GST-SHR3 was highest at the early time points and decreased during the subsequent chase at a rate significantly faster (t1/2 ∼20 min) than the rate of Gap1p degradation (Figure 8, 1o Glut-Agarose and 2o anti-Gap1p). On the basis of these results we conclude that the Shr3p–Gap1p complex is the result of transient interactions within the ER and reflects the transport of Gap1p from the ER. These experiments also indicate that the observed association (Figure 6) is not due to a postsolubilization artifact.

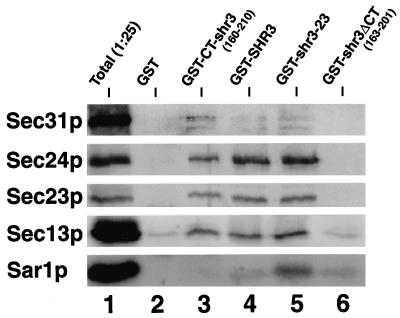

COPII Components Associate with Shr3p

We examined the possibility that COPII components bind to Shr3p or to a complex, minimally containing Shr3p and an aap. Immunoblots, prepared similarly to those in Figure 6, were probed with rabbit anti-Sec31p, -Sec24p, -Sec23p, -Sec13p, and -Sar1p antibodies (Figure 9). The results show that four of the COPII components examined copurify with GST-Shr3p (Figure 9, lane 4). The association is dependent on the presence of Shr3p; no binding was observed to GST alone (Figure 9, lane 2). The copurification of COPII components with Shr3p depends on interactions with the hydrophilic C-terminal domain of Shr3p; similar levels of binding were observed with the GST-CT-shr3(160–210) construct (Figure 9, lane 3). Strikingly, the COPII components copurified equally well, or better, with GST-shr3-23 (Figure 9, lane 4), a nonfunctional mutant version of Shr3p that is unable to associate with Gap1p (Figure 6, lane 4). This latter observation suggests that COPII coatomer components bind directly to Shr3p, and that coatomer binding can occur without the involvement of aaps. Significantly less COPII copurified together with the GST-shr3ΔCT fusion protein (Figure 9, lane 6); however, this construct weakly complements shr3 null mutations when overexpressed; the low levels of COPII binding must suffice to promote the exit of aaps from the ER. Because it is known that the Sec23p–Sec24p and Sec13p–Sec31p subcomplexes are relatively stable (Salama et al., 1993), it is possible that only one of the coatomer components binds to Shr3p and that the other components copurify as a result of coatomer–coatomer interactions. Further experiments are needed to define which coatomer subunit(s) binds Shr3p. Additionally, it should be noted that these experiments do not rule out the possibility that coatomer binding occurs through interactions with other unidentified proteins present in complex with Shr3p.

Figure 9.

COPII coatomer components copurify with GST-SHR3. The indicated GST fusion constructs were expressed in FGY145 and purified as in Figure 6, except that after affinity chromatography the glutathione-conjugated beads were washed four times with low-potassium FGB containing 0.02% DM (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). Proteins were denatured at 65°C for 5 min and resolved by SDS-PAGE in a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Protein bands corresponding to Sec31p, Sec24p, Sec23p, Sec13p, and Sar1p were visualized using rabbit antiserum as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS.

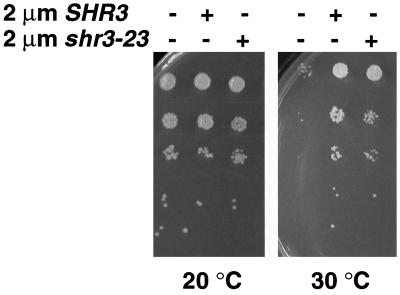

Shr3p Is Capable of Recruiting COPII Components to the ER Membrane

The observations that COPII components bind Shr3p and that multicopy SHR3 partially suppresses temperature-sensitive mutations in several COPII components (Figure 5A) suggested that Shr3p may facilitate ER vesicle formation by recruiting coatomer components to the ER membrane. This possibility was tested by examining the effects of overproducing the mutant shr3-23p (pMB42) in the panel of sec− mutant strains (Table 3). Based on the GST fusion experiments discussed in the preceding section (Figure 9), this nonfunctional mutant protein retains the capacity to bind COPII components.

When present on a multicopy 2μ plasmid, shr3-23 suppresses sec12-1 mutations nearly as well as SHR3 (Figure 10). We did not detect suppression of the other sec− alleles tested (Table 3), nor did high copy expression affect the growth of SEC+ strains. In similar experiments, the induced expression of GST-CT-shr3(160–210), which exhibits almost an identical affinity for coatomer, did not suppress sec12-1. The membrane association of the GST-CT-shr3(160–210) and GST-shr3-23 fusion constructs was determined. GST-CT-shr3(160–210) is primarily a soluble protein, but a fraction associates with membranes, presumably through interactions with aaps (Figure 6). The mutant GST-shr3-23 protein fractionates as an integral membrane protein. Thus the suppression of sec12-1 by multicopy expression of shr3-23 and not GST-CT-shr3 suggests that a membrane anchor is required.

Figure 10.

Multicopy expression of shr3-23 partially suppresses the temperature-sensitive phenotype of sec12-1. Serial dilutions of strain MAS26-1A (sec12-1) transformed with pRS202 (−), pPL250 (SHR3), and pMB42 (shr3-23) were spotted on SC (minus uracil), incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 d, and photographed.

DISCUSSION

Gap1p contains 12 stretches of hydrophobic sequences that are predicted to be membrane-spanning domains. We have determined that the C-terminal six transmembrane domains are integrated into the ER membrane in the absence of Shr3p, indicating that Shr3p does not participate in the cotranslational insertion of aaps into the ER membrane (Figure 1). The fact that the levels of KAR2 are not elevated in shr3Δ6 cells supports this conclusion (Figure 3); it has previously been shown that KAR2 expression is induced under conditions that block the translocation of proteins into the ER membrane (Arnold and Wittrup, 1994). In contrast to mutations that result in Gap1p misfolding, the aaps that accumulate in the ER membrane of shr3 mutants do not activate the ER unfolded protein stress response pathway (Figures 2 and 3) even when the expression of Gap1p and several other aaps is derepressed. It is important to note that our data provide only an indirect measurement of folding and do not rule out subtle local folding defects that do not induce the unfolded stress response pathway. However, these results coupled to our additional findings regarding Shr3p function make it unlikely that Shr3p functions as an aap-specific foldase. Our results regarding the structure of Gap1p strongly suggest that aaps attain their proper membrane topologies and are correctly folded in shr3 null mutant cells; thus these processes are independent of Shr3p function.

shr3Δ1 mutations exhibited genetic interactions with only a specific subset of genes encoding secretory components that function to promote ER vesicle formation (Table 3 and Figure 4). SEC13 and SEC31 encode proteins that are known to physically interact, copurify biochemically (Pryer et al., 1993; Salama et al., 1993, 1997), and constitute components of one of the complexes that assemble to form the COPII coat required for vesicle budding from the ER membrane in yeast (Barlowe et al., 1994). The overexpression of SHR3 partially suppresses sec12-1, sec13-1, and sec31-1 mutations, enabling mutants to grow at increased temperatures (Figure 5A). These results indicate that the presence of Shr3p within the ER membrane stabilizes specific events of the ER vesicle budding process. The suppression data is consistent with the observed synthetic interactions between shr3Δ1 and sec13-1 and sec31-1 (Figure 4).

The multicopy suppression of both sec12-1 (Figure 5A) and the inositol requirement of sec13-1 (Figure 5B) provide significant clues as to the mechanism of Shr3p function and suggest that Shr3p functions by facilitating the association of COPII components with the ER membrane. The partial suppression of sec12-1 by multicopy expression of the nonfunctional mutant shr3-23 allele (Figure 10) strengthens this view. Sec12p is an integral ER membrane protein that promotes the binding of Sar1p to the ER membrane (Nakano et al., 1988; d’Enfert et al., 1991). ER-associated Sar1p enhances the binding of the Sec23p–Sec24p complex to ER membrane, an event that ultimately leads to COPII vesicle formation. Acidic phospholipids (e.g., phosphatidylinositol-4-phos-phate) are required for the binding of COPII components to liposomes made from pure lipids (Matsuoka et al., 1998b).

Consistent with the genetic data, we have found that COPII coatomer components Sec13p, Sec23p, Sec24p, and Sec31p but not Sar1p copurify with Shr3p. Their ability to copurify with Shr3p is dependent on the presence of the hydrophilic carboxyl-terminal domain of Shr3p (Figure 9). Although our experiments do not conclusively address whether COPII components bind directly with Shr3p or through other proteins present in complex with Shr3p, our finding that COPII components copurify equally well with GST-CT-shr3(160–210) and the nonfunctional mutant GST-shr3-23 suggests that the association occurs through direct interactions. Because Gap1p is unable to associate with shr3-23p (Figure 6), the binding of COPII components to shr3-23p indicates that COPII binding appears to be independent of an association with aaps. The observed associations between COPII components and Shr3p must be transient, because Shr3p is itself not packaged into COPII vesicles (Kuehn et al., 1996). Thus the recruitment of COPII cannot be the sole function of Shr3p but must also depend on its ability to interact specifically with aaps (Figures 6 and 7).

Together our genetic and biochemical data suggest a model in which Shr3p functions as a packaging chaperone that initiates vesicle formation in the proximity of aaps. We propose that the combined ability of Shr3p to physically associate with aaps and to recruit COPII components facilitates the formation of a primed transport-competent aap complex. A primed aap complex could provide a nucleation site, or docking site, enabling additional COPII components to localize and assemble to form a vesicle coat. Alternatively, the primed aap complex may diffuse laterally within the ER membrane until it associates with a previously formed Sar1p–Sec16p–Sed4p–Sec23p–Sec24p complex (Espenshade et al., 1995; Gimeno et al., 1995; Bednarek et al., 1996). In either case, once the primed aap complex comes in contact with sufficient COPII components necessary for vesicle formation, Shr3p must dissociate and diffuse away. The proposed scheme would ensure that buds form directly around aaps, thereby guaranteeing their inclusion into transport vesicles.

We believe this model is consistent with previous observations that aaps bind in vitro to a complex containing a subset of COPII components (Sar1p–Sec23p–Sec24p) (Kuehn et al., 1998). The binding of aaps to this complex was shown to be Shr3p dependent; however, Shr3p was itself not detected as a component of this complex. We have found that in comparison with the other COPII components Sar1p binds Shr3p very poorly, if at all (Figure 9). Thus the possibility exists that Sar1p is unable to bind to a primed aap complex in the presence of Shr3p. The dissociation of Shr3p away from the primed aap complex would be a prerequisite for Sar1p binding and the conversion of prebudding complex into a bona fide vesicle bud site. The precise mechanisms governing the dissociation of Shr3p remain to be elucidated.

Why do aaps require a specific packaging chaperone? It is possible that aaps experience physical constraints that restrict their entry into bud sites, and that Shr3p functions to circumvent these constraints. In vitro, both COPI and COPII components promote vesicle formation from highly purified ER membrane preparations, and the resulting vesicles have a diameter (distance between outer membrane leaflets) of 59–65 nm (Barlowe et al., 1994; Bednarek et al., 1995). On the basis of the structures of crystallized polytopic membrane proteins, the aaps are likely to have a molecular diameter between 4 and 8 nm (Henderson et al., 1990; Deisenhofer et al., 1995; Iwata et al., 1995; Tsukihara et al., 1996). Thus, polytopic membrane proteins have the potential to occupy a substantial portion of a bud. As the COPII components assemble and the plane of the membrane distorts and begins to pucker, the movement of polytopic membrane proteins into or out of the emerging bud is likely to become physically constrained. The degree to which movement is restricted should be proportional to the molecular diameter of a protein. The packaging of “large” polytopic membrane proteins, e.g., aaps, is likely to take place at an early stage of vesicle formation before any significant distortion of the planar membrane.

Our postulated role for packaging chaperones enables several predictions to be made. The retention of large resident ER proteins (e.g., Sec61p) within the ER may not require an active mechanism or retention signal. Large resident proteins that lack the ability to interact with a packaging chaperone would be passively retained. Similarly, our findings may provide a framework to explain the difficulties of obtaining functional expression of heterologous membrane proteins. In yeast heterologously expressed polytopic mammalian membrane proteins are often retained in the ER. In several instances it has been shown that these proteins are enzymatically active within the ER and thus correctly folded (e.g., Kasahara and Kasahara, 1996, 1997). Because heterologously expressed proteins lack cognate packaging chaperones, COPII coat assembly cannot initiate in proximity to their location in the membrane, and thus they will be excluded from ER transport vesicles.

Additionally, we expect that other large nonresident ER membrane proteins require the action of packaging chaperones, cognate Shr3p-like proteins, to exit the ER. To test this possibility, we have initiated a genetic approach to identify additional proteins that may function as packaging chaperones and have isolated three SSH (suppressors of shr) genes that when overexpressed bypass the requirement of Shr3p (Melin-Larsson, unpublished results). The SSH suppressors encode novel membrane proteins that presumably reside in the ER, and as is the case with SHR3, the overexpression of these suppressors affects the assembly of COPII components. The further analysis of these bypass suppressors may provide information regarding the mechanisms governing the exit of other families of polytopic membrane proteins away from the ER.

It should be noted that packaging chaperones may recognize structural motifs that form or become available only as proteins obtain their correctly folded conformations; similarly, motifs may consist of sequences present on more than one subunit of multimeric protein complexes. Thus it is possible that packaging chaperones govern the secretion of membrane protein complexes that assemble within the ER membrane. An example of this may be the assembly of the vacuolar H+-ATPase that occurs within the ER (Graham et al., 1998). In such cases packaging chaperones would passively function as components of the ER quality control system. Finally, recent reports indicate that coatomer homologues exist in yeast (Pagano et al., 1999; Roberg et al., 1999) and in mammalian cells (Pagano et al., 1999; Tang et al., 1999). The Sec24p homologue Lst1p is required for the efficient packaging of Pma1p, indicating that coatomer components may exert a direct influence on cargo selection (Roberg et al., 1999). Because we have evidence that accessory packaging chaperones recruit coatomer to the ER membrane, they may participate in cargo selection by recruiting specific combinations of coatomer components.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Schekman and C.A. Kaiser for providing sec− strains and R. Schekman, B. André, A.L. Kruckeberg, C. Slayman, C. Stirling, and A. Nakano for generous gift of antibodies: anti-COPII, Gap1p, Gal2p, Pma1p, Sec61p, and Sar1p, respectively. Additionally we thank A. Byström, S. Emr, M. Rose, and T. Stevens for providing plasmids. We greatly appreciate A. Moliner for technical expertise in obtaining the sec13-1 strains used in these studies and H. Klasson for helpful discussions. P.O.L. additionally acknowledges P. Martinez, C. Oellig, and R.F. Pettersson for fruitful discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research. The cooperative research agreement between Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Stockholm Branch, and Fuji Photo Film (Europe) is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations used:

- aap

amino acid permease

- COPII

coat components of ER-derived vesicles

- DM

N-dodecylmaltoside

- endoH

endoglycosidase H

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- HA

hemagglutinin

- nt

nucleotide

- PM

plasma membrane

REFERENCES

- Allen JB, Elledge SJ. A family of vectors that facilitate transposon and insertional mutagenesis of cloned genes in yeast. Yeast. 1994;10:1267–1272. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André B. An overview of membrane transport proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1995;11:1575–1611. doi: 10.1002/yea.320111605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annaert WG, Becker B, Kistner U, Reth M, Jahn R. Export of cellubrevin from the endoplasmic reticulum is controlled by BAP31. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1397–1410. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.6.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antebi A, Fink GR. The yeast Ca2+-ATPase homologue, PMR1, is required for normal Golgi function and localizes in a novel Golgi-like distribution. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:633–654. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.6.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aridor M, Weissman J, Bannykh S, Nuoffer C, Balch WE. Cargo selection by the COPII budding machinery during export from the ER. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:61–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold CE, Wittrup KD. The stress response to loss of signal recognition particle function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30412–30418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankaitis VA, Johnson LM, Emr SD. Isolation of yeast mutants defective in protein targeting to the vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9075–9079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.9075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe C. COPII and selective export from the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1404:67–76. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlowe C, Orci L, Yeung T, Hosobuchi M, Hamamoto S, Salama N, Rexach MF, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Schekman R. COPII: a membrane coat formed by Sec proteins that drive vesicle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 1994;77:895–907. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek SY, Orci L, Schekman R. Traffic COPs and the formation of vesicle coats. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:468–473. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)84943-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek SY, Ravazzola M, Hosobuchi M, Amherdt M, Perrelet A, Schekman R, Orci L. COPI- and COPII-coated vesicles bud directly from the endoplasmic reticulum in yeast. Cell. 1995;83:1183–1196. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belden WJ, Barlowe C. Erv25p, a component of COPII-coated vesicles, forms a complex with Emp24p that is required for efficient endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26939–26946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JL, Schekman R. Selective packaging of cargo molecules into endoplasmic reticulum-derived COPII vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:837–842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]